Published online Dec 19, 2025. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v15.i12.112479

Revised: August 23, 2025

Accepted: October 11, 2025

Published online: December 19, 2025

Processing time: 122 Days and 3.9 Hours

Substantial clinical evidence supports the efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for various diseases, particularly in oncology. However, the true impact of CBT interventions on cancer-related fatigue and mental health in patients with ovarian cancer remains unknown.

To evaluate the effects of CBT on fatigue, anxiety, depression and quality of life in patients with ovarian cancer.

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) on CBT for patients with ovarian cancer were searched in the PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science and Cochrane Library databases. According to the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses statement, we formulated the inclusion and exclusion criteria, stri

Six RCTs with 332 ovarian cancer patients were included. Compared with the control group, cancer fatigue [mean difference (MD) = -0.98, 95% confidence in

CBT effectively improves mental status and cancer-related fatigue in patients with ovarian cancer undergoing chemotherapy. Future research should prioritize adequately powered RCTs with standardized outcome measures and longitudinal designs to establish sustained efficacy.

Core Tip: Despite the role of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) in oncology, its specific impact on debilitating fatigue and mental health in patients with ovarian cancer remains unclear. This meta-analysis revealed that CBT simultaneously alleviates cancer-related fatigue, anxiety, depression, and sleep disturbances, while significantly improving quality of life in chemotherapy-treated patients. Nurse-guided delivery enhances these benefits. These findings suggest that CBT may be an essential non-pharmacological strategy for managing this population’s complex symptom burden.

- Citation: Zhao F, Bo Y, Su XL. Effect of cognitive behavioral therapy on cancer-related fatigue and psychological status in ovarian cancer patients: A meta-analysis. World J Psychiatry 2025; 15(12): 112479

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v15/i12/112479.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v15.i12.112479

Ovarian cancer (OC) is the seventh most prevalent malignancy in women worldwide, accounting for over 324000 annual diagnoses and 200000 deaths worldwide[1]. Epidemiological analyses have revealed a 50-year surge in OC incidence, particularly in developed nations, where it is the fifth leading cause of cancer-related mortality among women[2]. Despite the declining incidence trends observed in certain regions (e.g., United States, 2000-2017), delayed diagnosis persists

Patients with OC frequently experience multidimensional chronic symptoms, including anxiety, depression, sleep disturbances, somatic complaints, and impaired health-related quality of life (QoL). These manifestations not only disrupt daily functioning but may also synergize with psychosocial stressors (e.g., social isolation) to exacerbate tumor pro

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is a psychological treatment method based on the cognitive-behavioral model, with the core assumption that psychological disorders and emotional disturbances are maintained by maladaptive cognitive patterns and avoidance behaviors. It aims to alleviate symptoms by changing cognitive and behavioral patterns. In recent years, CBT has led to the development of new therapies based on traditional cognitive concepts such as accep

This meta-analysis was conducted in accordance with the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses guidelines and recommendations of the Cochrane collaboration[9]. The study was registered in PROSPERO under the registration number of CRD42022327092.

The following databases were searched: PubMed/MEDLINE, EMBASE, Web of Science, and the Cochrane Library. The retrieval time for all databases was from the start of the databases to March 1, 2025, and the search was conducted without language restrictions. The search was conducted for “ovarian cancer”, “cognitive behavioral therapy” (including specific therapies from the third wave), and “randomized clinical trials” as keywords. The specific search strategy is shown in Supplementary Table 1. In addition, the reference track, ClinicalTrials.gov (https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/, accessed March 2025) were used as a supplementary search.

The inclusion and exclusion criteria were pre-specified according to the PICOS principle (population, intervention, comparison, outcomes and study), as shown in Table 1.

| PICOS | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

| Population | Patients diagnosed with ovarian cancer who are undergoing chemotherapy after surgery | Patients with other concomitant diseases |

| Intervention | Using CBT for treatment, but not limited to specific schools of thought within CBT theory, including the third wave, such as ACT, MBCT, DBT, etc. | In addition to CBT, the experimental group also received other treatments |

| Comparison | CBT is not used, but specific treatment methods are not restricted | No controlled study |

| Outcome | Cancer-related fatigue, mental health status (such as anxiety and depression levels), and quality of life of patients; there are no restrictions on the scales used to assess the outcomes | Unreliable or incomplete data |

| Study design | Randomized controls trails | Case report, conference paper, review article and letter; duplicate literature or duplicate studies |

Detailed information of the included studies was collected independently by two authors (Zhao F and Bo Y) and included: (1) Name of the first author and year of publication; (2) Study design; (3) Patient baseline characteristics (age, sample size, tumor stage); (4) Information on treatment/control group, including the specific forms and details of CBT intervention, follow-up time, etc.; (5) Primary outcome indicators (mental health status, such as anxiety, depression; QoL; cancer-related fatigue); and (6) Secondary outcome indicators [quality of sleep (QoS)].

All data are presented as mean ± SD. If multiple groups of data meet the inclusion and exclusion criteria in the same literature, the data from different groups were extracted and marked. Based on internationally recognized criteria for psychological assessment scales (such as validity, reliability, and scope of use), select the set of data that best reflected the results of the analysis. In this meta-analysis, the comparison was the change in the value of the data pre- and post-inter

Change value = post-intervention assessment value-baseline (before intervention) assessment value. If the change value was negative, the estimated value after the intervention was lower than that before the intervention; otherwise, the result was positive, indicating an increase. The formula for calculating the mean of the change value is as follows: The formula for calculating SD value change as follow: (corr = 0.5)[10,11].

It should be noted that higher scores on depression scales indicate a more severe degree of depression, and this also holds true for anxiety scales. For both scales, a greater magnitude of pre- to post-intervention score change (consistent with the direction of either decrease or increase) reflected a more significant improvement in depression or anxiety sym

Two authors (Zhao F and Bo Y) independently assessed the risk of bias of the included studies. Any disagreements during evaluation were resolved by a third author (Su XL). The randomized controlled trials (RCTs) used the revised Cochrane collaboration risk of bias tool (ROB 2.0)[10].

R software (version R x64 4.2.2; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria; https://www.r-project.org/) was used for data analysis; the mean difference (MD) or standardized mean difference (SMD) with a 95% confidence interval (CI) for continuous variables was calculated. Heterogeneity was assessed using I2 and τ2 statistical tests. An I2 > 50% indicated high heterogeneity. A random-effects model was adopted when high heterogeneity was observed. Otherwise, a fixed effects model was used. Moreover, sources of heterogeneity were searched, and subgroup analyses according to detection time points and sensitivity analyses were performed. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

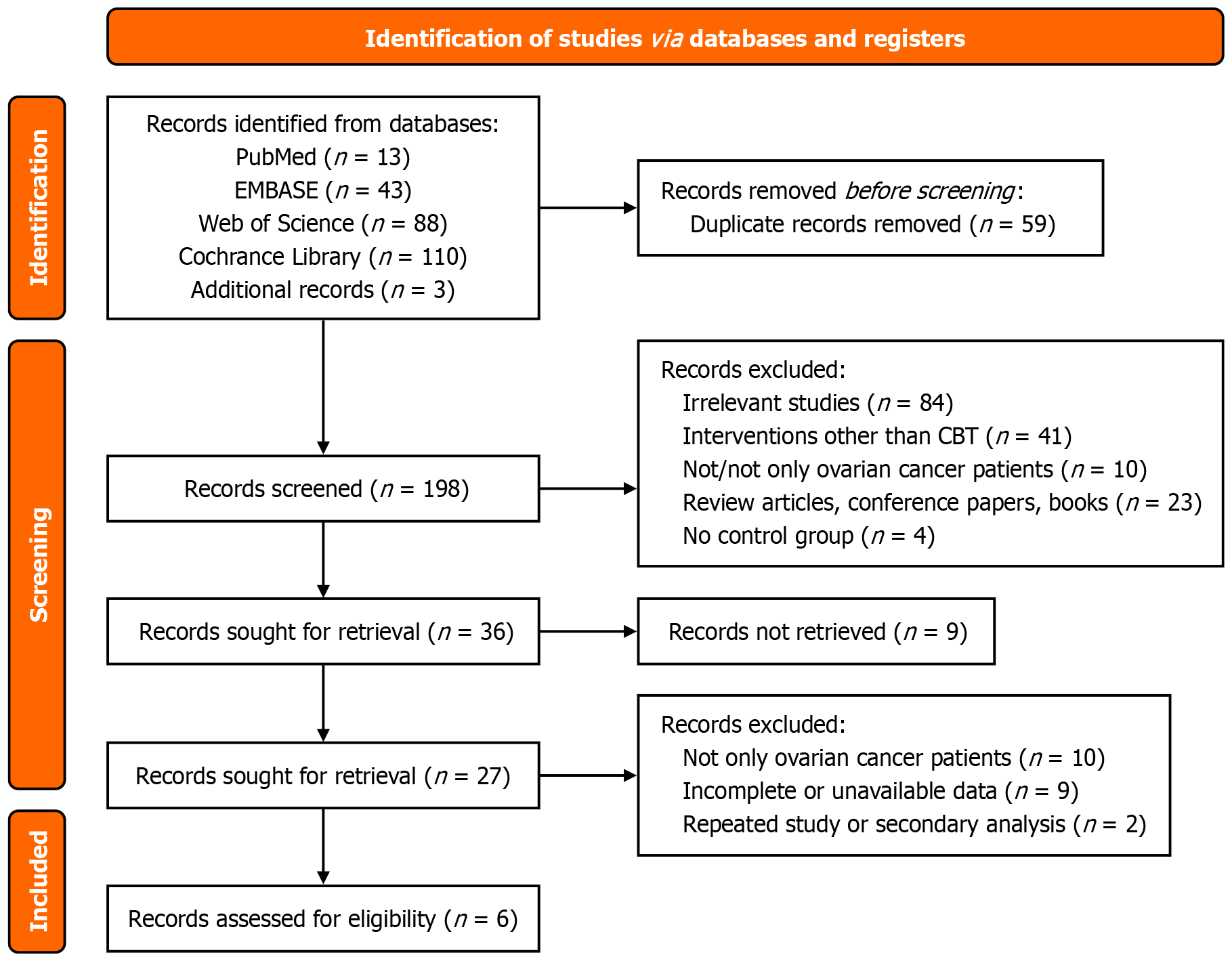

After searching the following databases, we identified a total of 259 potential studies (PubMed, n = 13; EMBASE, n = 43; Web of Science, n = 88; the Cochrane Library, n = 110; supplementary searching, n = 3), of which 59 were duplicate studies (Figure 1). By reviewing titles and abstracts, 253 studies were excluded for failing to meet inclusion criteria or lacking full-text availability. Ultimately, 6 studies involving 332 patients were included (all English literature).

Table 2 shows that among the included studies, 4 studies originated from China and the United States, and the others were from the United Kingdom and Canada[12-17]. Two studies were multicenter, but only 2 studies had been registered. Baseline characteristics were consistent between the experimental and control groups in all studies (e.g., age, sex, and sample size). All studies assessed the mental health status of patients after the intervention, including levels of depression and anxiety; four studies assessed the relief of patients’ cancer fatigue; three studies assessed the improvement in patients’ QoL or QoS. However, the scales used for the assessment were somewhat different.

| Ref. | Country | Study design | Multi-center | Registered | Record patient time | Ovarian cancer patients | Age (T) | Age (C) | Sample size | Intervention (T) | Intervention (C) | Outcome | |

| T | C | ||||||||||||

| Frangou et al[12] | United Kingdom | RCT | Yes | Yes | November 2013 to January 2018 | Primary or relapsed epithelial OC | 58.1 ± 9.46 | 60.9 ± 10.2 | 34 | 33 | CBT | Standard care | Depression, QoL |

| Zhou et al[13] | China | RCT | No | NR | January 2018 to March 2019 | Meets the diagnostic criteria for OC | 58.64 ± 13.82 | 60.23 ± 15.78 | 37 | 36 | CBT + conventional nursing | Conventional nursing | Cancer-related fatigue, depression, anxiety, sleep quality, QoL |

| Zhang et al[14] | China | RCT | No | NR | November 2014 to November 2015 | Ages of 18 and 80 with OC | NR | NR | 33 | 34 | CBT + exercise | Usual care | Cancer-related fatigue, depression, sleep quality |

| Petzel et al[15] | United States | RCT | Yes | Yes | September 2012 to February 2013 | Stage III/IV or recurrent (any stage) epithelial OC | 59.6 ± 10.0 | 55.5 ± 8.4 | 16 | 12 | Website based on CBT | Control website | Distress, depression, anxiety |

| Moonsammy et al[16] | Canada | RCT | No | NR | March 2011 to July 2011 | Newly diagnosed with OC | 52.7 ± 12.1 | 57.8 ± 12.0 | 3 | 5 | CBT | Surveillance | Cancer-related fatigue, depression, anxiety |

| Rost et al[17] | United States | RCT | No | NR | NR | Women with stage III or IV OC | 56 | 56 | 15 | 16 | ACT | Treatment as usual | Distress, depression, anxiety, QoL, acceptance |

Table 3 presents treatment characteristics. The CBT intervention in three studies included exercise, that is, cognitive intervention combined with behavioral intervention. Of the remaining studies, two used conventional CBT and one used CBT-based ACT. Interventions were mostly provided through collaboration between oncology nurses or nurses with experience in cancer care (two studies), clinical psychologists (two studies), and CBT counsellors (two studies). All inter

| Ref. | Intervention (T) specific method | Intervention (C) specific method | CBT implementer | Intervention duration/frequency/total times or time | Intervention time point | Assessment time point | Follow-up time after treatment | Lost to follow-up |

| Frangou et al[12] | CBT (face to face sessions) | Standard care | Doctoral-level clinical/counselling psychologist | 90 minutes/NR/3 months | The 6-12 weeks post-chemotherapy | Baseline/after treatment 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, 18, 24 months | 24 months | 40 (37.4) |

| Zhou et al[13] | At-home CBT + conventional nursing | Conventional nursing | Nurses | Half an hour/3-4 times per week/NR | In the light of chemotherapy | Baseline/after treatment 1, 2, 3 months | 3 months | 0 (0) |

| Zhang et al[14] | Nurse-led home-based exercise + CBT | Nurse-led usual care | CBT-trained nurses | 1 hour/once weekly/12 consecutive weeks | Before the sixth chemotherapy treatment | Baseline/immediately after treatment/3 month | 3 months | 3 (4.3) |

| Petzel et al[15] | Visit website (social cognitive theory + CBT) | Visit website (usual care materials) | Medical and psychological providers | Unlimited time/2-3 times per week/60 days | Post-operative checkup or planned chemotherapy | Baseline/1 month | 1 month | 6 (17.1) |

| Moonsammy et al[16] | CBT (counselling sessions by phone) | Surveillance | CBT-trained nurses | 1 hour/once every two weeks/12 weeks | Before completing two cycles of adjuvant chemotherapy | Baseline/immediately after intervention/3 months | 3 months | 5 (26.3) |

| Rost et al[17] | ACT (face to face meetings) | Treatment as usual | A PhD-level clinical psychologist | 1 hour/4 months/12 occasions | In the chemotherapy treatments | Baseline/at the end of the 4th, 8th, and final (12th) session | End of treatment | 16 (34) |

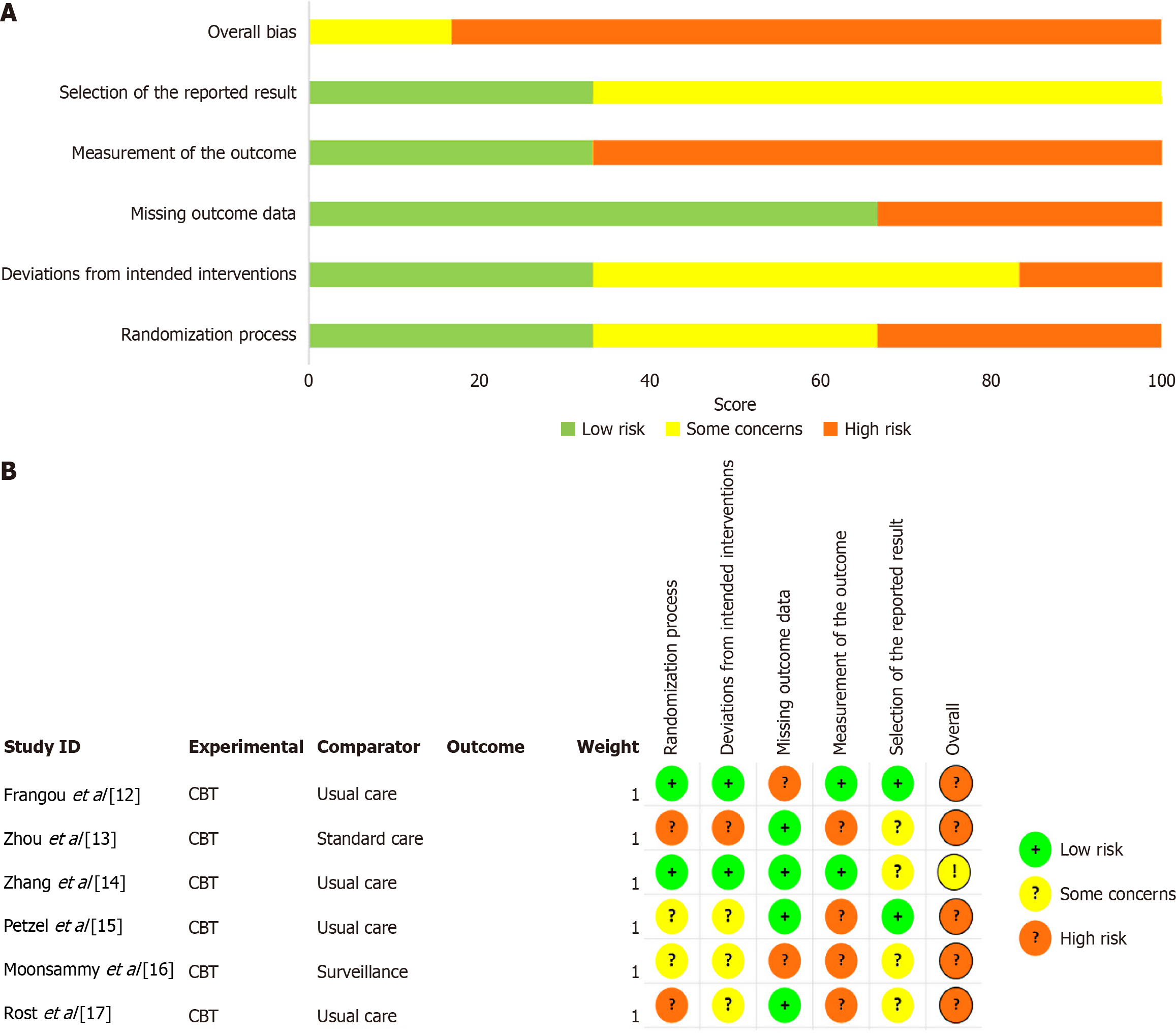

Figure 2 shows the quality assessment of the included studies using the Cochrane RoB 2.0. This tool assesses bias risk from five perspectives: “Randomization process”, “deviations from intended interventions”, “missing outcome data”, “measurement of the outcome” and “selection of the reported result”, with results represented “high risk”, “low risk”, or “some concerns risk/uncertain risk”.

Only 3 (50%) studies in the included RCTs mentioned “random” allocation methods, but no specific methods were detailed. So they were judged as “uncertain risks” in random sequence generation. The other studies were low-risk. Three studies described allocation concealment, three studies reported single-blind trials (blinding of participants, intervention implementers, or measurers), and only one study reported blinding of intervention implementers and outcome measures. The blinding of the other studies was unclear. This may be related to the difficulty of practicing blinding in clinical trials. Five studies reported loss-to-follow-up and incomplete data, ranging from 4.3% to 37.4%, which was related to the poor prognosis of patients with OC. The loss-to-follow-up rate of four studies was more than 15% due to disease progression, patient death, reluctance to continue to receive intervention, etc. Most studies were judged to be at uncertain risk of bias due to uncertainty about whether missing outcome data would have affected the results. Regarding selective reporting bias, only two studies had a low risk of bias, while the risk of bias for the remaining studies was uncertain. However, in terms of overall risk, the majority of studies were assessed as high risk.

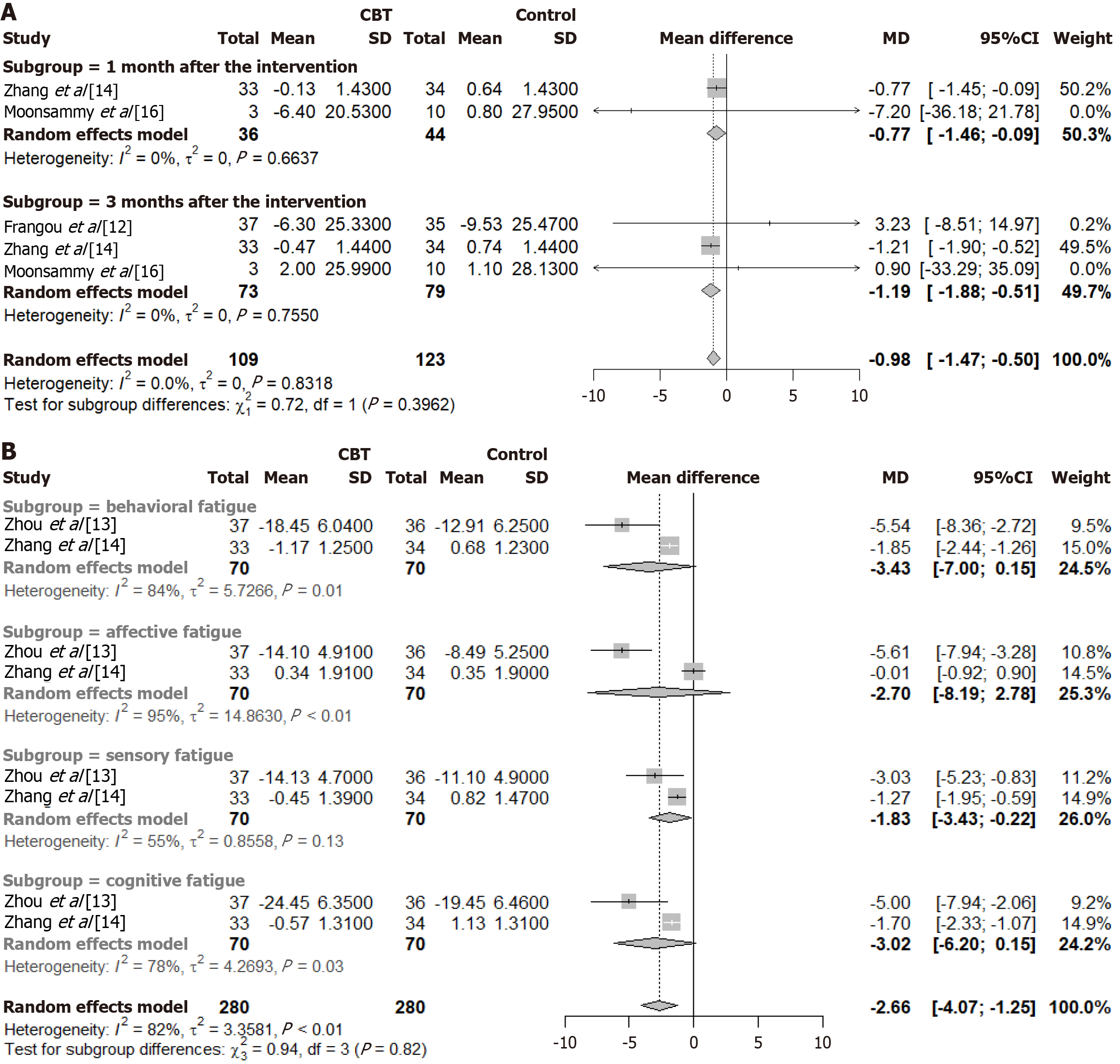

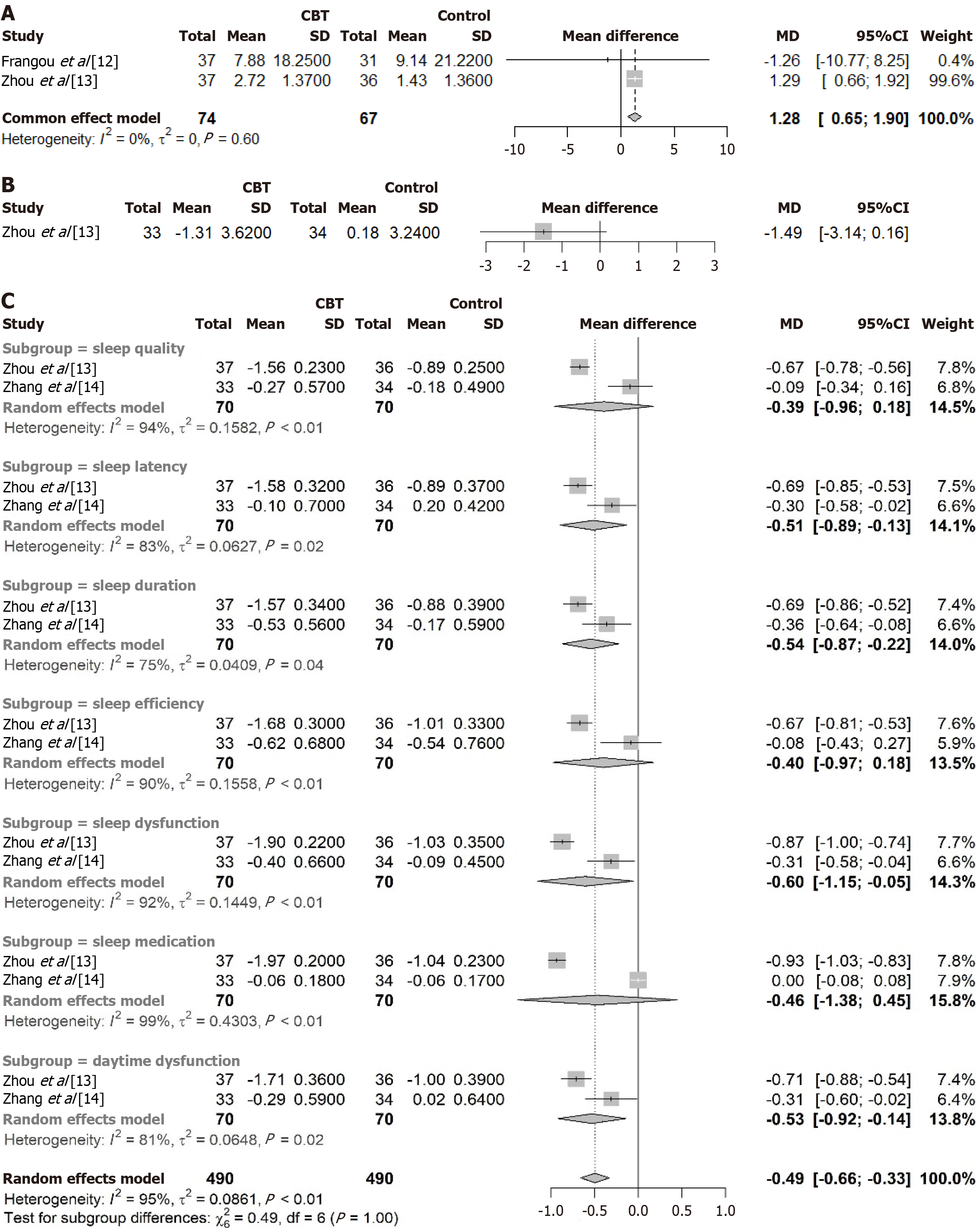

Three of the included studies used the revised piper fatigue scale to assess patient fatigue. Compared to the control group, the cancer-related fatigue degree in the experimental group was reduced after CBT intervention (MD = -0.98, 95%CI: -1.47 to -0.50, P < 0.01; heterogeneity I2 = 0%), and the difference between the two groups was statistically significant. The results of the subgroup analysis showed that the reduction effect was more pronounced at three months after the intervention than at one month after the intervention (Figure 3A). In addition, a subgroup meta-analysis comparing the results of the subscales of cancer fatigue also showed that after three months of treatment, CBT reportedly reduced the fatigue of patients in terms of behavioral, sensory, and cognitive fatigue, and the difference between the groups was statistically significant. Given that heterogeneity was > 50%, a random effects model was used; the MD value was -2.66 and the 95%CI was -4.07 to -1.25, P < 0.01 (Figure 3B). Further results from the Hedges’ g test showed Hedges’ g = -0.286, 95%CI: -0.577 to 0.005, suggesting that the experimental intervention had no significant effect on improving cancer-related fatigue.

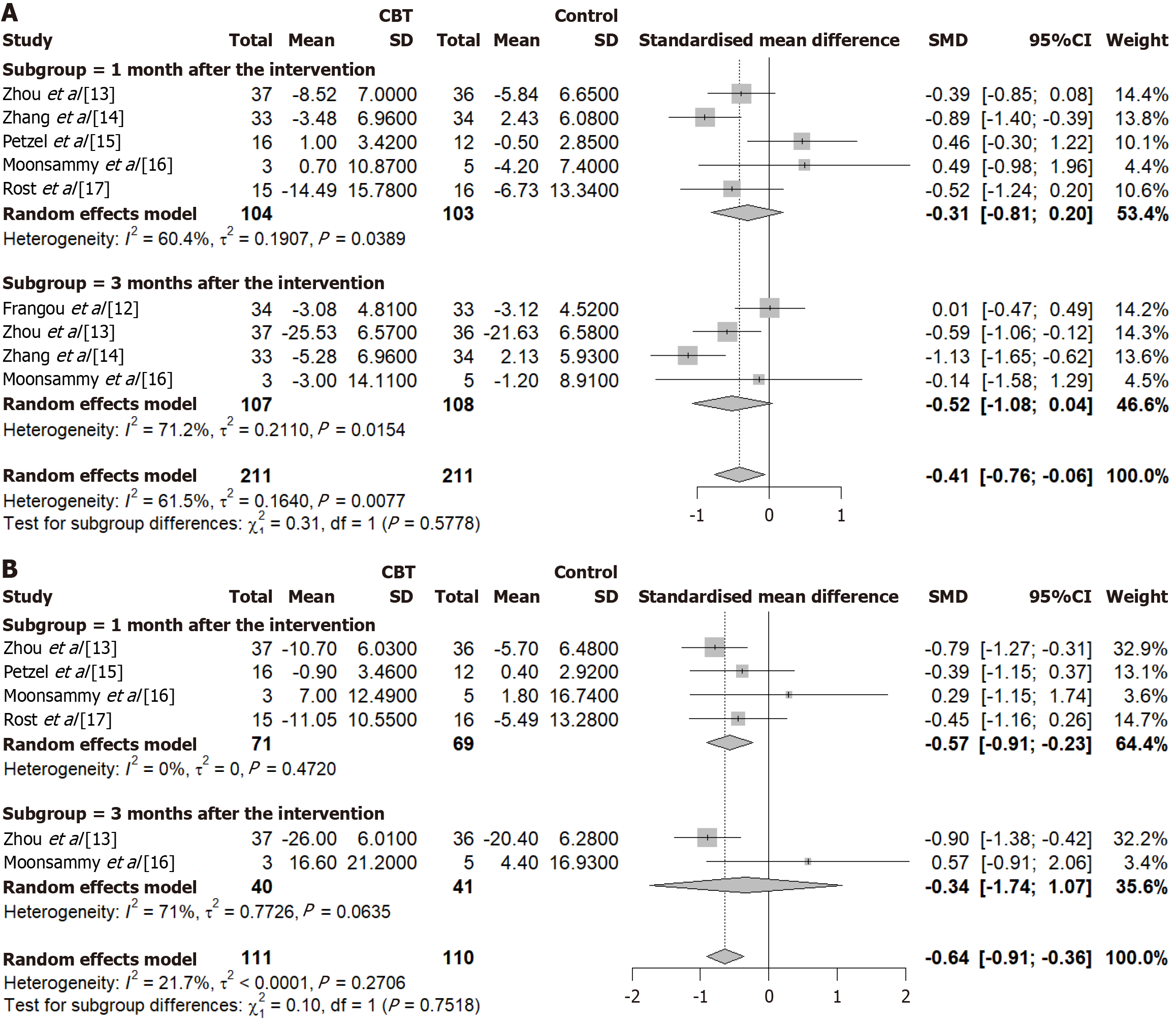

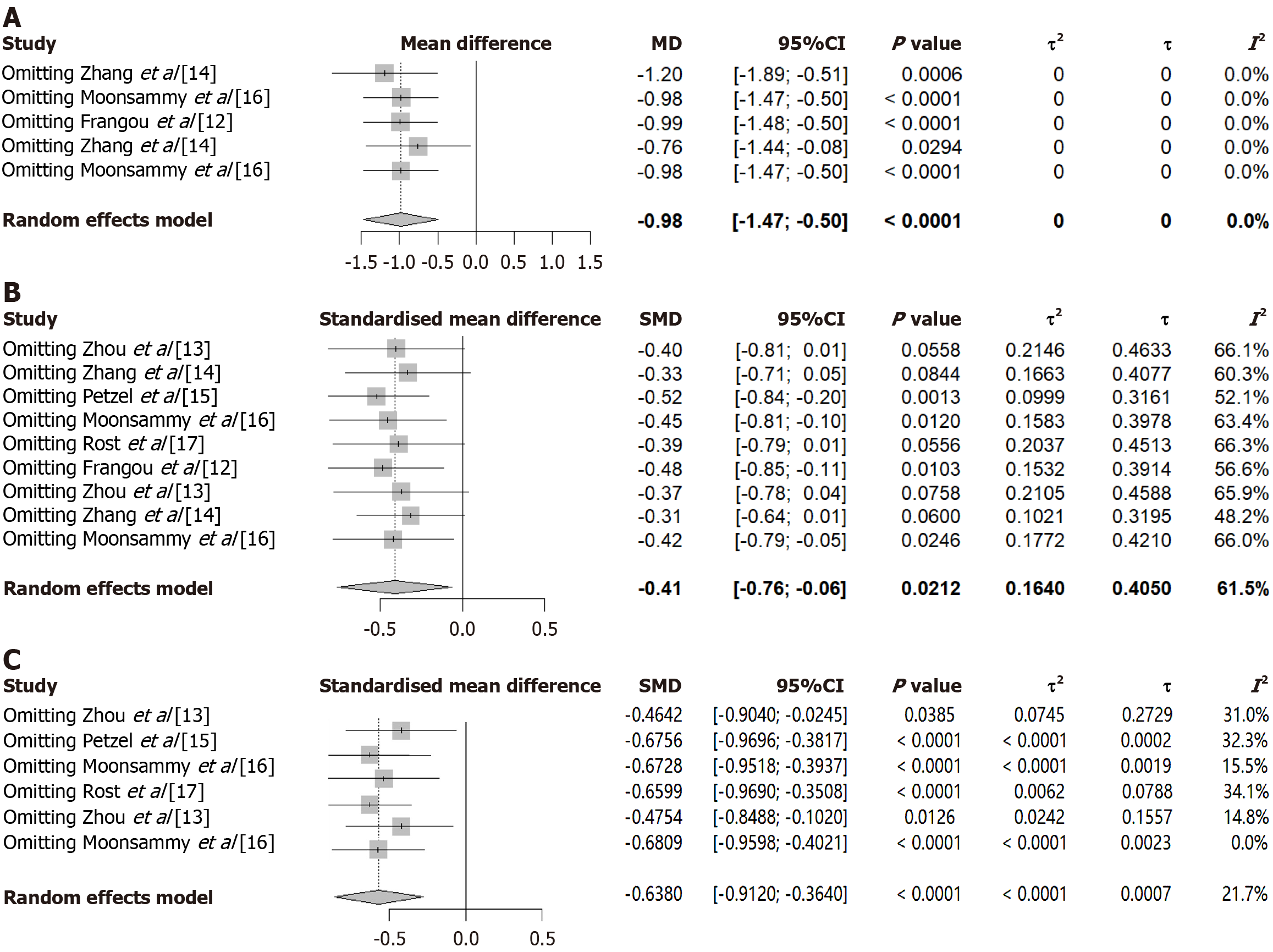

Depression is the most common psychological problem among patients with cancer. Three studies used the Zung self-rating depression scale, one used the patient health questionnaire-9 depression test, one used the center for epidemiologic studies-depression scale, and one used the hospital anxiety and depression scale to assess patients’ depression level; therefore, the pooled effect size was analyzed using SMD. The results of the meta-analysis showed that, compared with the control group, after the CBT intervention, patients’ depression scores were reduced, and the difference between the groups was statistically significant (SMD = -0.41, 95%CI: -0.76 to -0.06, P < 0.01; heterogeneity I2 = 61.5%). The results of the subgroup analysis showed that the depression level of patients in the experimental group was not significantly reduced at one month (SMD = -0.31, 95%CI: -0.81 to 0.20; heterogeneity I2 = 60.4%) or three months (SMD = -0.52, 95%CI:

The meta-analysis of anxiety included eight independent data groups at two time points from four studies. Among the four included studies, one used the self-rating anxiety scale, one used the hospital anxiety depression scale, one used the beck anxiety inventory, and one used the state trait anxiety inventory (STAI-Y) scale to assess anxiety in patients. The pooled effect size was analyzed using SMD. In Moonsammy et al[16], the STAI-Y scale was used to evaluate total and trait anxiety, resulting in two anxiety values; thus, data analysis of the two groups. The meta-analysis results showed that after CBT intervention, the anxiety level of patients in the experimental group was significantly declined (SMD = -0.64, 95%CI: -0.91 to -0.36, P < 0.01; heterogeneity I2 = 21.7%); the difference between the groups was statistically significant. The results of the subgroup analysis showed that the anxiety level of patients in the experimental group was significantly reduced at one month after treatment (SMD = -0.57, 95%CI: -0.91 to -0.23), but there was no statistically significant difference at three months (SMD = -0.34, 95%CI: -1.94 to 1.03) (Figure 4B). Further results from the Hedges’ g test showed Hedges’ g = -0.526, 95%CI: -0.887 to -0.165, indicating that the experimental intervention had a significant moderating effect on anxiety improvement.

Two studies reported the QoS and QoL. The Pittsburgh sleep quality index was used to evaluate the incidence and type of sleep disorders. The QoL questionnaire-core 30 scale, which includes six single items, three cardinal symptom modules, five functional modules, and one general health module, was used to evaluate QoL. As shown in Figure 5, the QoS and QoL of patients in the experimental group improved after the CBT intervention; the difference between the groups was statistically significant (MD = -0.49, 95%CI: -0.66 to -0.33; MD = 1.28, 95%CI: 0.65 to 1.90, P < 0.01).

The impact of each study on the pooled results was assessed by sequentially excluding individual studies (Figure 6). In the meta-analysis of cancer-related fatigue, heterogeneity remained at 0% regardless of which study was removed. However, in the meta-analysis of anxiety, heterogeneity decreased to 0% after excluding a specific study (Moonsammy et al[16]), suggesting that this study may be the primary source of heterogeneity. However, in the meta-analysis of depression, excluding any of the included studies did not significantly alter the heterogeneity of the effect size, which remained high. This suggests that individual studies were not the primary source of heterogeneity, and the stability of the meta-analysis results did not undergo significant changes, thereby validating the rationality and reliability of our analysis.

Univariate meta-regression analyses of the relationships among depression, anxiety, patient characteristics, and specific interventions were performed. As shown in Table 4, there was no correlation between patients’ depression levels and patients’ age, nationality, specific interventions of CBT, or depression assessment scale (all P > 0.05). However, whether the implementation process was nurse-guided had a significant effect on depression (P < 0.05). In contrast, nationality was associated with an improvement in anxiety levels after the intervention. Additionally, whether nurses provided guidance was associated with patients’ anxiety and depression levels post-intervention (P < 0.05), suggesting that nurses’ involvement may influence intervention outcomes. However, it should be noted that nurse involvement may help alleviate patients’ depression (with a negative estimate), but the presence of nurses may increase anxiety levels (with a positive estimate). Other than this, we did not find any evidence that any other moderating factor influenced the strength of the depression-anxiety association.

| Analysis | Depression | Anxiety | |||||

| Estimate (SE) | 95%CI | P value | Estimate (SE) | 95%CI | P value | ||

| Patients characteristics | |||||||

| Age | 0.02 (0.14) | -0.26 to 0.29 | 0.8838 | -0.06 (0.04) | -0.14 to 0.03 | 0.1733 | |

| China | -0.91 (0.59) | -2.06 to 0.24 | 0.1229 | ||||

| United States | -0.22 (0.65) | -1.48 to 1.05 | 0.7388 | -1.28 (0.56) | -2.36 to -0.19 | 0.0217a | |

| United Kingdom | -0.16 (0.67) | -1.46 to 1.15 | 0.8127 | -0.85 (0.59) | -2.01 to 0.31 | 0.1497 | |

| Intervention methods | |||||||

| CBT/exercise | -0.49 (0.43) | -1.33 to 0.34 | 0.2485 | ||||

| I-CBT | 0.98 (0.55) | -0.10 to 2.05 | 0.0767 | 0.06 (0.53) | -0.98 to 1.10 | 0.9092 | |

| Traditional-CBT | 0.23 (0.41) | -0.57 to 1.02 | 0.5727 | -0.27 (0.40) | -1.06 to 0.51 | 0.4966 | |

| Assessment scales | |||||||

| CES-D | 0.68 (0.69) | -0.66 to 2.03 | 0.3179 | STAI-Y | 0.88 (0.64) | -0.37 to 2.14 | 0.1704 |

| HADS | 0.98 (0.61) | -0.21 to 2.16 | 0.1073 | HADS | 0.06 (0.53) | -0.98 to 1.10 | 0.9092 |

| PHQ-9 | 0.53 (0.53) | -0.50 to 1.56 | 0.3157 | SAS | -0.40 (0.40) | -1.19 to 0.40 | 0.3266 |

| SDS | -0.22 (0.45) | -1.10 to 0.66 | 0.6292 | ||||

| Nurse-led | -0.56 (0.28) | -1.12 to -0.00 | 0.0486a | 1.15 (0.55) | 0.08 to 2.22 | 0.0359a | |

Cancer-related fatigue is a persistent subjective feeling of physical, emotional, and/or cognitive tiredness or weakness resulting from cancer treatment; this is a problem faced by many patients with cancer[18,19]. Women with OC have been reported to experience fatigue over time, which has also been reported as a pre-diagnostic symptom. Treatments for cancer-related fatigue include pharmacological treatments, such as psychostimulants[20], and non-pharmacological treatments, including CBT[21] and physical exercise[22]; these have been reported to significantly reduce fatigue in patients. Similar results were observed in the present meta-analysis. Regardless of whether it was one month or three months after CBT intervention, compared with the control group, the cancer fatigue of the patients was reduced, and the intergroup differences were statistically significant (MD = -0.98, 95%CI: -1.47 to -0.50, P < 0.01). In addition, the results of the subgroup meta-analysis suggested that CBT treatment was effective in improving behavioral, sensory, and cognitive fatigue but had no significant effect on affective fatigue.

Psychological problems such as anxiety and depression are more prevalent in patients with OC, especially in newly diagnosed patients. The occurrence of these symptoms was significantly associated with factors such as marital status, presence of pain, and chemotherapy history. Therefore, identifying and managing these psychological problems is important for improving the overall health of patients with OC[23,24]. Depressive symptoms have been reported in more than 50% of patients with OC after the completion of chemotherapy for primary or recurrent disease. Depression is a toxicity caused by chemotherapy itself, a hypothesis supported by in vivo experiments in which mice showed signs of depression after cancer chemotherapy[25]. One study reported that depressive symptoms improved spontaneously within three months in patients receiving chemotherapy and were not affected by CBT-based intervention[12]. However, the results of our meta-analysis suggest that CBT can also improve negative mood in patients with OC (depression: SMD = -0.41, 95%CI: -0.76 to -0.06; anxiety: SMD = -0.57, 95%CI: -0.86 to -0.27, P < 0.01). CBT was more effective in reducing anxiety than depressive symptoms. This may be related to the fact that CBT is a treatment method used to correct cogni

However, given the very small sample size of one included study (Moonsammy et al[16]), which may have an impact on the authenticity of the results, we attempted to exclude this study. After exclusion, depression = -0.42 (-0.79 to -0.05) and anxiety = -0.57 (-0.86 to -0.27) (Figure 6), which was consistent with the results without exclusion. However, this suggests that future large-scale studies are required to validate these results.

These disease states are mutually causal and affect each other. Cancer-related fatigue is more prominent in OC, causing physical and mental distress, and even severe negative emotions such as anxiety and depression[26,27]. At the same time, sleep disturbance is considered to be an important cause of cancer-related fatigue, which in turn affects QoS and forms a vicious circle[28]. Medysky et al[29] found that sleep disturbances are directly proportional to the severity of fatigue in patients. Therefore, for patients with OC, active nursing intervention is needed to reduce cancer-related fatigue, thereby improving emotional function, QoS, and, ultimately, QoL.

A variety of CBT-based techniques were used in the included studies, including traditional CBT and ACT. CBT focuses on identifying and reorganizing the cycles of negative emotions and related behaviors, such as social withdrawal, while ACT therapy has the effect of making people aware of their entanglement with negative emotions while teaching them the skills to participate in and experience meaningful activities. Both can effectively solve psychological problems in patients with cancer[30]. Moreover, the personnel who implement CBT differ. Nevertheless, the results of this study show that regardless of whether CBT-based treatment is nurse-led, online, via psychologists, or home-based, it can improve negative emotions such as anxiety and depression and relieve cancer fatigue. It is worth mentioning that nurses seem to play a larger role in psychological interventions. In the six included studies, nurses participated in four intervention trials, all of which successfully improved patients’ mental status. Studies on high-quality nursing care in the perioperative period showed that nurse-led psychological interventions significantly reduced anxiety, depression, and cancer-related fatigue in patients with OC[31,32]. This may be due to the fact that nurses are closer to patients, easily accessible and providing intervention. Overall, cognitive-behavioral care can help patients with OC regain hope in life.

The quality of the included studies is not high enough. Among the six RCTs, half of the studies did not report the “random sequence generation” and “allocation concealment”, which has the risk of selection bias. Furthermore, the blinding method is not good enough; just one study reported double-blind, and no study reported triple-blinding, which may be related to the difficulty in implementing blinding due to the particularity of clinical trials. Additionally, the loss-to-follow-up rate of 5 studies exceeded 15%, which had the risk of reporting bias.

Also, the sample sizes of the included studies ranged from 8 to 73. The inclusion of small-sample studies may have affected the authenticity of the results. However, owing to the limited number of relevant published studies and the minimal impact on the analysis results after inclusion, these studies were ultimately included. However, if large-sample data becomes available in the future, such small-sample studies may be excluded.

Finally, in the meta-analysis results, heterogeneity for depression and cancer fatigue (subscale) remained relatively high (both > 50%) even after applying random-effects models and subgroup analyses; however, sensitivity analyses indicated no significant change in the stability of the meta-analysis findings. These findings collectively indicate that heterogeneity stems from clinical variability, potentially related to the following factors: (1) Differences in depression assessment scales; (2) Inconsistencies in the specific methods and duration of CBT interventions; and (3) Individual pa

There are limited RCTs on CBT for OC, and the quality of the published studies is generally low. Currently, it is dif

To our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis to evaluate the effectiveness of CBT on mental status and cancer-related fatigue in patients with OC undergoing chemotherapy. The present review suggests that CBT interventions may help relieve cancer-related fatigue, alleviat symptoms of anxiety and depression, and contribut to improvements in QoL and QoS in this patient population. These findings may assist physicians, nurses, and patients in recognizing the potential role of CBT as part of comprehensive cancer care, with a view to potentially enhancing mental, physical, and social health out

| 1. | Mazidimoradi A, Momenimovahed Z, Allahqoli L, Tiznobaik A, Hajinasab N, Salehiniya H, Alkatout I. The global, regional and national epidemiology, incidence, mortality, and burden of ovarian cancer. Health Sci Rep. 2022;5:e936. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ali AT, Al-Ani O, Al-Ani F. Epidemiology and risk factors for ovarian cancer. Prz Menopauzalny. 2023;22:93-104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Khatoon E, Parama D, Kumar A, Alqahtani MS, Abbas M, Girisa S, Sethi G, Kunnumakkara AB. Targeting PD-1/PD-L1 axis as new horizon for ovarian cancer therapy. Life Sci. 2022;306:120827. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ghirardi V, Fagotti A, Ansaloni L, Valle M, Roviello F, Sorrentino L, Accarpio F, Baiocchi G, Piccini L, De Simone M, Coccolini F, Visaloco M, Bacchetti S, Scambia G, Marrelli D. Diagnostic and Therapeutic Pathway of Advanced Ovarian Cancer with Peritoneal Metastases. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15:407. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Pennington KP, Schlumbrecht M, McGregor BA, Goodheart MJ, Heron L, Zimmerman B, Telles R, Zia S, Penedo FJ, Lutgendorf SK. Living Well: Protocol for a web-based program to improve quality of life in rural and urban ovarian cancer survivors. Contemp Clin Trials. 2024;144:107612. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Oswald LB, Eisel SL, Tometich DB, Bryant C, Hoogland AI, Small BJ, Apte SM, Chon HS, Shahzad MM, Gonzalez BD, Jim HSL. Cumulative burden of symptomatology in patients with gynecologic malignancies undergoing chemotherapy. Health Psychol. 2022;41:864-873. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Yuan T, Zhou Y, Wang T, Li Y, Wang Y. Impact research of pain nursing combined with hospice care on quality of life for patients with advanced lung cancer. Medicine (Baltimore). 2024;103:e37687. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Salkovskis PM, Sighvatsson MB, Sigurdsson JF. How effective psychological treatments work: mechanisms of change in cognitive behavioural therapy and beyond. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2023;51:595-615. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11206] [Cited by in RCA: 11315] [Article Influence: 665.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Chandler J, Welch VA, Higgins JP, Thomas J. Updated guidance for trusted systematic reviews: a new edition of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;10:ED000142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1361] [Cited by in RCA: 3417] [Article Influence: 488.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | Cochrane. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. [cited September 29, 2025]. Available from: https://www.cochrane.org/authors/handbooks-and-manuals/handbook#:~:text=The%20Handbook%20includes%20guidance%20on%20the%20standard%20methods,individual%20patient%20data%2C%20prospective%20meta-analysis%2C%20and%20qualitative%20research%29. |

| 12. | Frangou E, Bertelli G, Love S, Mackean MJ, Glasspool RM, Fotopoulou C, Cook A, Nicum S, Lord R, Ferguson M, Roux RL, Martinez M, Butcher C, Hulbert-Williams N, Howells L, Blagden SP. OVPSYCH2: A randomized controlled trial of psychological support versus standard of care following chemotherapy for ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2021;162:431-439. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Zhou L, Tian YL, Yu JY, Chen H, An F. Effect of at-home cognitive behavior therapy combined with nursing on revised piper fatigue scale, pittsburgh sleep quality index, self-rating anxiety scale and self-rating depression scale of ovarian cancer patients after chemotherapy. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2020;13:4227-4234. |

| 14. | Zhang Q, Li F, Zhang H, Yu X, Cong Y. Effects of nurse-led home-based exercise & cognitive behavioral therapy on reducing cancer-related fatigue in patients with ovarian cancer during and after chemotherapy: A randomized controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud. 2018;78:52-60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Petzel SV, Isaksson Vogel R, Cragg J, McClellan M, Chan D, Jacko JA, Sainfort F, Geller MA. Effects of web-based instruction and patient preferences on patient-reported outcomes and learning for women with advanced ovarian cancer: A randomized controlled trial. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2018;36:503-519. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Moonsammy SH, Guglietti CL, Santa Mina D, Ferguson S, Kuk JL, Urowitz S, Wiljer D, Ritvo P. A pilot study of an exercise & cognitive behavioral therapy intervention for epithelial ovarian cancer patients. J Ovarian Res. 2013;6:21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Rost AD, Wilson K, Buchanan E, Hildebrandt MJ, Mutch D. Improving Psychological Adjustment Among Late-Stage Ovarian Cancer Patients: Examining the Role of Avoidance in Treatment. Cogn Behav Pract. 2012;19:508-517. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Bohsas H, Alibrahim H, Swed S, A El-Sakka A, Alyosef M, Haitham Sarraj H, Sawaf B, Baraa Habib M, Fathey S, Rashid G, Thabet Daraghmi A, Thabet Daraghmi A, Hafez W. Knowledge toward ovarian cancer symptoms among women in Syria: Cross-sectional study. Heliyon. 2023;9:e19076. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Hammer MJ, Cooper BA, Chen LM, Wright AA, Pozzar R, Blank SV, Cohen B, Dunn L, Paul S, Conley YP, Levine JD, Miaskowski C. Identification of distinct symptom profiles in patients with gynecologic cancers using a pre-specified symptom cluster. Support Care Cancer. 2023;31:485. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Qu D, Zhang Z, Yu X, Zhao J, Qiu F, Huang J. Psychotropic drugs for the management of cancer-related fatigue: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2016;25:970-979. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Yennurajalingam S, Konopleva M, Carmack CL, Dinardo CD, Gaffney M, Michener HK, Lu Z, Stanton P, Ning J, Qiao W, Bruera E. Treatment of Cancer-related-Fatigue in Acute Hematological Malignancies: Results of a Feasibility Study of using Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2023;65:e189-e197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Tian L, Lu HJ, Lin L, Hu Y. Effects of aerobic exercise on cancer-related fatigue: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24:969-983. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Johnston EA, Veenhuizen SGA, Ibiebele TI, Webb PM, van der Pols JC; OPAL Study Group. Mental health and diet quality after primary treatment for ovarian cancer. Nutr Diet. 2024;81:215-227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Pegreffi F, Di Fiore R, Suleiman S, Veronese N, Fiorenza G, Pecorino B, Scollo P, Calleja-Agius J. Exploring the impact of exercise on women with ovarian cancer: A call for more methodologically standardized RCTs to enable a realistic systematic review. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2025;51:109556. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Egeland M, Guinaudie C, Du Preez A, Musaelyan K, Zunszain PA, Fernandes C, Pariante CM, Thuret S. Depletion of adult neurogenesis using the chemotherapy drug temozolomide in mice induces behavioural and biological changes relevant to depression. Transl Psychiatry. 2017;7:e1101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Lin T, Ping Y, Jing CM, Xu ZX, Ping Z. The efficacy of internet-based cognitive behavior therapy for psychological health and quality of life among breast cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychol. 2024;15:1488586. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Hagan TL, Arida JA, Hughes SH, Donovan HS. Creating Individualized Symptom Management Goals and Strategies for Cancer-Related Fatigue for Patients With Recurrent Ovarian Cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2017;40:305-313. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Ebede CC, Jang Y, Escalante CP. Cancer-Related Fatigue in Cancer Survivorship. Med Clin North Am. 2017;101:1085-1097. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Medysky ME, Temesi J, Culos-Reed SN, Millet GY. Exercise, sleep and cancer-related fatigue: Are they related? Neurophysiol Clin. 2017;47:111-122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Davis CH, Twohig MP, Levin ME. Choosing ACT or CBT: A preliminary test of incorporating client preferences for depression treatment with college students. J Affect Disord. 2023;325:413-420. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Jin P, Sun LL, Li BX, Li M, Tian W. High-quality nursing care on psychological disorder in ovarian cancer during perioperative period: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2022;101:e29849. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Mao W, Chen W, Wang Y. Effect of virtual reality-based mindfulness training model on anxiety, depression, and cancer-related fatigue in ovarian cancer patients during chemotherapy. Technol Health Care. 2024;32:1135-1148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/