Published online Dec 19, 2025. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v15.i12.111334

Revised: July 10, 2025

Accepted: September 19, 2025

Published online: December 19, 2025

Processing time: 153 Days and 1.5 Hours

Economic violence is a type of domestic violence in which an intimate partner attempts to oppress, restrict, or direct a female by exercising control over her fina

To explore the impact of economic abuse on individual work performance and clarify the effective factors on financial exploitation among physicians and nurses.

The study has a cross-sectional design, and 305 married, female physicians and nurses working in a university hospital were included. Data was collected with demographic characteristics forms, “Revised Scale of Economic Abuse” and “Individual Work Performance Questionnaire”. Pearson correlation, comparative analyses, and internal consistency reliability tests were used.

The average age was 39.04 ± 9.41. Among the respondents 69.2% were nurses and 63.9% held a bachelor’s degree. The mean score for the Revised Scale of Economic Abuse was 2.80 ± 4.73 while it was 3.86 ± 0.60 for the Individual Work Perfor

Our study revealed no relationship between economic abuse and individual work performance, confirming that nurses are exposed to more economic abuse and exploitation than physicians and exhibit higher work performance.

Core Tip: Economic abuse is abusive behaviors in the form of controlling access to money, limiting financial independence, or sabotaging employment opportunities. It is a very serious issue because it undermines a female’s autonomy, making it difficult for her to leave abusive relationships or achieve financial independence. Addressing economic abuse is crucial for empowering females and fostering gender equality.

- Citation: Sarac E, Odabas D. Economic abuse as a female battering form: A cross-sectional study among physicians and nurses. World J Psychiatry 2025; 15(12): 111334

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v15/i12/111334.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v15.i12.111334

Financial exploitation is a form of abuse that has serious implications for the victim’s economic independence and quality of life[1]. Economic or financial abuse, in simpler terms, involves controlling a female’s access to money, essential needs, assets, and financial information. This form of abuse can manifest in various ways, often subtly eroding a female’s independence and trapping her in a cycle of dependency[2]. Restricting access to funds also directly limits her ability to make independent choices, impacting everything from daily expenses to long-term security. Denying basic necessities like food or healthcare further compromises her well-being and autonomy[3].

Types of economic abuse against females also include withholding funds, preventing employment or education, stealing or misusing finances, controlling or limiting access to property and assets, forcing debt or economic hardship, and hiding or restricting access to financial information[4]. The aim of these behaviors is to diminish a female’s financial independence and make her reliant on abusers. This type of abuse also seriously undermines the victim’s safety, is often combined with physical or emotional violence, and can have serious consequences[5-7]. Kaittila et al[8] clarified in their study that economic exploitation could be divided into four categories: (1) Economic sabotage; (2) Withholding resources; (3) Financial harassment; and (4) Stealing. Prior studies reported that males did not want females to use or enjoy the items the male had purchased in their house or apartment where they lived together[6,7]. In another paper authors revealed that economic exploitation was statistically significant based on the socioeconomic inequalities such as education, unemployment, and justifying wife beating[9]. The findings of a study that Alsawalqa[10] conducted showed that female economic abuse decreased as their level of education and length of marriage increased. Also, the author found that the husband’s higher level of education would increase the likelihood of economic abuse. Based on these similar findings many studies highlighted that comprehensive strategies involving legal, social, and economic initiatives are essential to prevent and address economic abuse effectively.

Preventing economic abuse against females involves multiple strategies. The most important precaution for every culture is enacting and enforcing laws that safeguard female’s financial rights and criminalize economic abuse[5,11]. Besides creating appropriate law, educating women on managing finances, understanding legal rights, and building economic independence and providing financial counseling, shelter, and support networks for victims to regain control over their finances are the main supports for victimized females[7].

It is clear that for all females who encounter partner abuse, a steady financial outlet is central to living an abuse-free life. In addition to previous studies showing that domestic abuse is associated with financial dependency, there are also findings emphasizing that this abuse affects the work performance of working females[12]. Economic abuse can sig

A study by Adams et al[14] found a strong correlation between economic abuse and symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder, further compounding the challenges faced by victims in the workplace. The hyperarousal and emotional dysregulation associated with post-traumatic stress disorder can significantly impair focus and decision-making abilities, crucial for successful job performance. A study conducted by Wathen et al[15] revealed that females experiencing do

Reduced job satisfaction and motivation are also significant consequences of economic abuse. When a female’s financial independence is curtailed and her career aspirations are undermined, her sense of self-worth and professional identity can suffer[14,15]. Abusers may actively sabotage a female’s employment by preventing her from attending work, creating transportation difficulties, or demanding her presence at home. Even without direct sabotage, the emotional and psychological toll of the abuse can make it difficult for women to maintain a consistent work schedule. The need to attend court appointments, seek medical care, or find safe housing can also contribute to increased absenteeism.

In light of these findings, our study aimed to make a theoretical contribution to the field of economic exploitation of females by exploring the effect of economic abuse on individual work performance and clarifying the effective factors on the financial exploitation among female physicians and nurses.

This cross-sectional study determined the frequency of economic abuse among a group of married female physicians and nurses and its effect on their work performance. Participants were recruited from among 305 married female health professionals (94 physicians and 211 nurses) working at a university hospital in Ankara, the capital city of Türkiye. To recruit as many of the married female physicians and nurses working in the hospital as possible, a convenience sampling method was used. All were invited to participate in the study if: (1) Aged > 18 years; (2) Female; (3) Married; (4) Currently working as a physician or nurse at the university hospital where the study was conducted; and (5) Agreed to participate in the study. Those that agreed to participate provided written informed consent prior to the start of the study.

Data were collected via an online questionnaire after contacting the physicians and nurses working at the hospital. Recognizing the ethical considerations and practical challenges associated with directly contacting healthcare professionals, we utilized a gatekeeper approach, securing contact details through the managers responsible for overseeing the nurses and physicians within their respective healthcare settings. This method ensured adherence to institutional protocols and respected the professional boundaries of the participants.

First, it ensured that participation in the study was presented within the context of their professional responsibilities and with the awareness of their supervisors. Second, it respected the nurses’ and physicians’ time and workload, allowing managers to assess the feasibility of their staff’s involvement without directly burdening the individuals. Finally, this method facilitated a more organized and efficient recruitment process as managers could disseminate information and gauge interest within their teams in a streamlined manner. We believe this process provided a trans

Data were collected using demographic data forms, the Revised Scale of Economic Abuse (SEA2) and the Individual Work Performance Questionnaire (IWPQ). Demographic characteristics included age, profession, level of education, residence, length of marriage, type of marriage, spouse occupation, having children, spouse’s education level, income, decision making process, and household sharing.

SEA2: SEA2 was developed and revised by Adams et al[14] and Adams et al[16]. It is used to measure the frequency of economic abuse one experiences in their relationships[17]. The Turkish version of the scale was reported to be valid and reliable. SEA2 is a 14-item scale with a two-factor structure. Each item is answered using a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (quite often). It includes two subscales: Economic exploitation and economic restriction. Adams et al[16] reported that the Cronbach’s alpha value for the total scale was 0.93 vs 0.91 for the economic exploitation subscale and 0.89 for the economic restriction subscale, and it had a high degree of reliability.

IWPQ: IWPQ was developed by Koopmans et al[18] and retested for cross-cultural validity by Koopmans et al[19]. Kaba and Ozturk[20] reported that the Turkish version of the scale was valid and reliable. The scale measures an individual’s perception of their work performance regardless of occupation. The original scale consists of 18 items across three subscales: Task performance (items 1-5); contextual performance (items 6-13); and counterproductive/inefficient work behavior (items 14-18). Items are answered using the following five-point Likert-type scale: 1: Rarely; 2: Sometimes; 3: Regularly; 4: Often; 5: Constantly. The IWPQ score is calculated by dividing the total scale score by the number of items. Higher scores indicate more positive perceptions of work performance. Items 14-18 (the counterproductive work behavior subscale) are reverse coded. Cronbach’s alpha values and confirmed item-total correlations (r) were determined to be 0.80 and 0.271-0.558, respectively, for the total scale, 0.86 and 0.657-0.753, respectively, for the task performance subscale, 0.78 and 0.426-0.706, respectively, for the contextual performance subscale, and 0.72 and 0.488-0.609, respectively, for counterproductive work behavior subscale. The level of statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows v.27.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States). The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to determine the normality of the distribution of data. In our study the data were normally distributed (P = 0.000). Analyses included the Cronbach’s alpha reliability test, independent t-test, and one-way analysis of variance. Games-Howell post-hoc analysis was also conducted to clarify the differences between effective factors. The total scale scores and subscale scores were calculated. Pearson’s correlation analysis was used to determine the relationship between the scales used in the study.

Among the study participants 69.2% were nurses and 30.8% were physicians with a mean age of 39.04 ± 9.41 years. In total 63.9% of the participants had a bachelor’s degree and 47.9% were married for ≥ 11 years. Most of the participants had a love marriage and jointly made decisions (89.2% and 91.8%, respectively). Additional demographic data are shown in Table 1.

| Category | n | mean ± SD/% |

| Age | 39.04 ± 9.41 | |

| Profession (%) | ||

| Physician | 94 | 30.8 |

| Nurse | 211 | 69.2 |

| Education | ||

| Bachelor’s degree | 195 | 63.9 |

| Postgraduate | 110 | 36.1 |

| Residence | ||

| City center | 282 | 92.5 |

| Small town | 23 | 7.5 |

| Length of marriage | ||

| 0-5 years | 102 | 33.4 |

| 6-10 years | 57 | 18.7 |

| 11 years and above | 146 | 47.9 |

| Type of marriage | ||

| Love | 272 | 89.2 |

| Blind date | 26 | 8.5 |

| Arranged | 7 | 2.3 |

| Spouse occupation | ||

| Healthcare professional | 109 | 35.7 |

| Public employee | 77 | 25.2 |

| Engineer | 58 | 19.0 |

| Security and safety | 25 | 8.2 |

| Private sector | 36 | 11.8 |

| Having children | ||

| Yes | 229 | 75.1 |

| No | 76 | 24.9 |

| Spouse education | ||

| Secondary school | 41 | 13.4 |

| Bachelor’s | 157 | 51.5 |

| Postgraduate | 107 | 35.1 |

| Decision-making process | ||

| The family’s decisions are primarily determined by the elders | 3 | 1.0 |

| My spouse’s decision is decisive | 19 | 6.2 |

| We decide jointly | 280 | 91.8 |

| Other/(I decide) | 3 | 1.0 |

| Household sharing | ||

| Completely belong to female | 17 | 5.6 |

| Majority belong to female | 160 | 52.5 |

| Completely belong to male | 0 | 0 |

| Majority belong to male | 5 | 1.6 |

| Equal | 123 | 40.3 |

| Total | 305 | 100 |

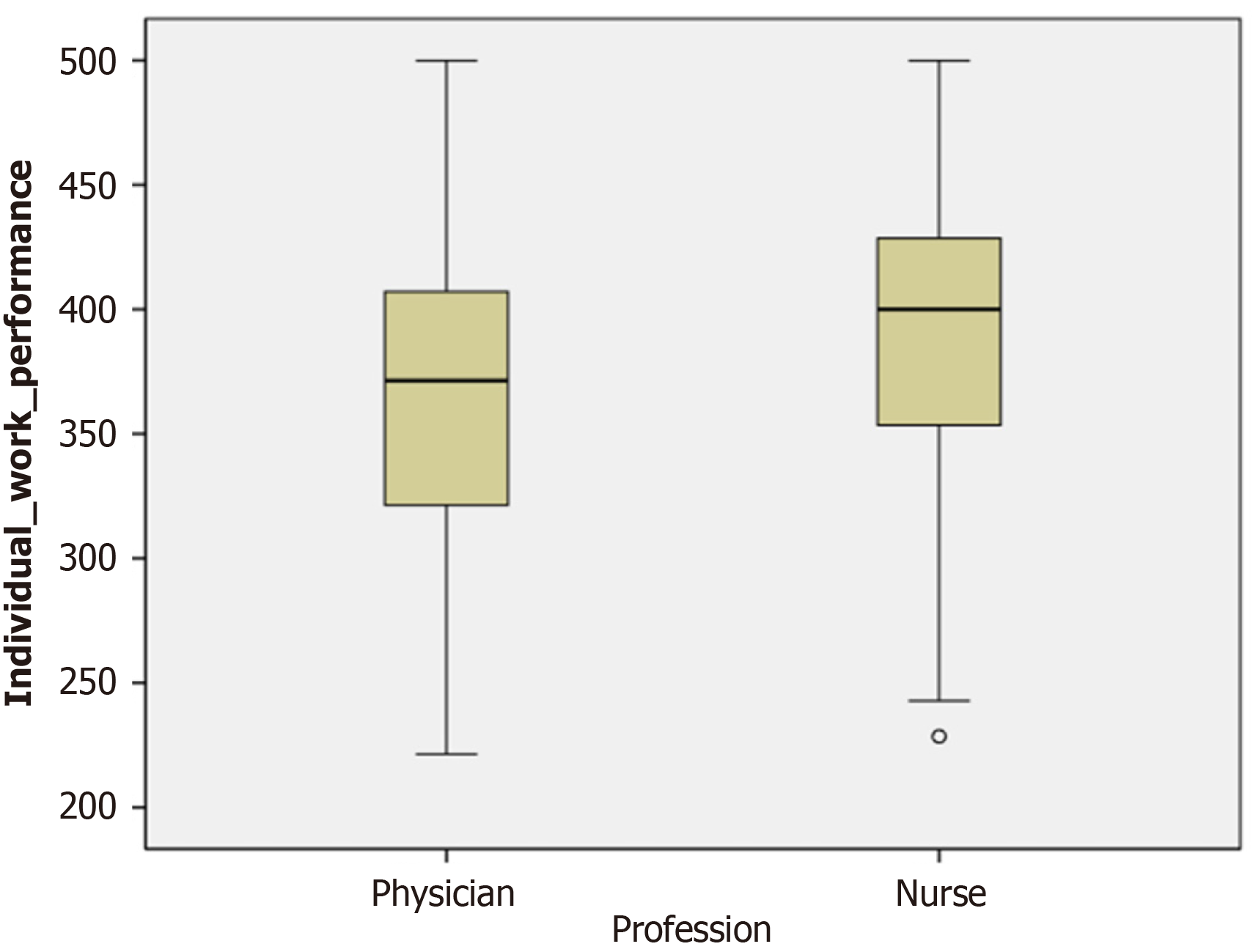

The mean SEA2 score for the physicians was 1.62 ± 3.25 vs 3.32 ± 5.18 for the nurses, indicating that the level of economic abuse among the nurses was higher than that among the physicians. Additionally, the mean IWPQ score for the physicians was 3.67 ± 0.62 vs 3.94 ± 0.57 for the nurses (Figure 1). Among the physicians the mean SEA2 economic exploitation subscale score was 0.43 ± 1.45 and the mean SEA2 economic restriction subscale score was 1.20 ± 2.15 as compared with 1.14 ± 2.61 and 2.20 ± 3.04, respectively, among the nurses. Statistical analysis showed that there was not a correlation between SEA2 and IWPQ scores (r = -0.078 and P = 0.176). Analysis details are shown in Table 2. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for SEA2 was 0.85 vs 0.80 for IWPQ.

There was a positive correlation between age and SEA2 total score (P = 0.043 and r = 0.116), SEA2 economic restriction subscale score (P ≤ 0.001 and r = 0.147), and IWPQ total score (P ≤ 0.001 and r = 0.292). Moreover, SEA2 and work performance scores differed according to profession (P = 0.004). The SEA2 total score differed according to the participants’ level of education and their spouse’s level of education, whereas the IWPQ total score did not (P = 0.465). There was a significant difference in the SEA2 total and all subscales scores according to having or not having children, whereas it had no impact on the IWPQ total score (P = 0.058).

SEA2 total and all subscale scores differed significantly according to the decision-making process at home and the sharing of household chores, but these factors had no effect on the IWPQ total score (P > 0.05). Additionally, the IWPQ total score differed significantly according to the length of marriage (P < 0.001). Comparison analysis showed that residence, spouse’s profession, and type of marriage did not have a significant effect on SEA2 or IWPQ scores (P > 0.05). Detailed findings are presented in Table 3.

| Effective factor | Total SEA2 | Economic exploitation | Economic restriction | IWPQ |

| Age | ||||

| r | 0.116 | 0.315 | 0.147 | 0.292 |

| P value | 0.043a | 0.058 | < 0.001a | < 0.001a |

| Profession | ||||

| Physician | 1.62 ± 3.25 | 0.43 ± 1.45 | 1.19 ± 2.15 | 3.67 ± 0.62 |

| Nurse | 3.32 ± 5.18 | 1.14 ± 2.61 | 2.18 ± 3.04 | 3.94 ± 0.57 |

| t | -2.928 | -3.029 | -3.241 | -3.675 |

| P value | 0.004a | 0.003a | 0.001a | < 0.001a |

| Education | ||||

| Bachelor’s degree | 3.20 ± 5.23 | 1.12 ± 2.66 | 2.07 ± 2.99 | 3.87 ± 0.56 |

| Postgraduate | 2.10 ± 3.61 | 0.58 ± 1.58 | 1.51 ± 2.49 | 3.82 ± 0.66 |

| t | 2.160 | 2.223 | 1.660 | 0.731 |

| P value | 0.032a | 0.027a | 0.098 | 0.465 |

| Length of marriage | ||||

| 0-5 years | 2.37 ± 4.45 | 0.91 ± 2.30 | 1.46 ± 2.60 | 3.68 ± 0.55 |

| 6-10 years | 2.54 ± 3.95 | 0.82 ± 2.22 | 1.71 ± 2.09 | 3.73 ± 0.58 |

| 11 years and above | 3.20 ± 5.18 | 0.97 ± 2.47 | 2.22 ± 2.18 | 4.02 ± 0.60 |

| F | 1.033 | 0.093 | 2.321 | 11.770 |

| P value | 0.357 | 0.912 | 0.100 | < 0.001a |

| Having children | ||||

| Yes | 3.21 ± 5.20 | 1.09 ± 2.59 | 2.12 ± 3.05 | 3.89 ± 0.60 |

| No | 1.56 ± 2.53 | 0.43 ± 1.19 | 1.13 ± 1.82 | 3.74 ± 0.58 |

| t | 3.656 | 2.995 | 3.409 | 1.902 |

| P value | < 0.001a | 0.003a | < 0.001a | 0.058 |

| Spouse education | ||||

| Secondary school graduates | 4.31 ± 6.14 | 1.43 ± 3.51 | 2.87 ± 3.28 | 4.04 ± 0.62 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 2.99 ± 4.94 | 1.11 ± 2.42 | 1.87 ± 2.87 | 3.84 ± 0.55 |

| Postgraduate | 1.94 ± 3.52 | 0.45 ± 1.42 | 1.48 ± 2.49 | 3.81 ± 0.65 |

| F | 4.058 | 3.687 | 3.648 | 2.417 |

| P value | 0.018a | 0.026a | 0.027a | 0.091 |

| Decision-making process at home | ||||

| The family’s decisions are primarily determined by the elders | 3.66 ± 5.50 | 1.33 ± 2.30 | 2.33 ± 3.21 | 4.23 ± 0.48 |

| My spouse’s decision is decisive | 9.21 ± 8.04 | 3.10 ± 4.31 | 6.10 ± 4.21 | 3.85 ± 0.72 |

| We decide jointly | 2.36 ± 4.12 | 0.78 ± 2.09 | 1.57 ± 2.48 | 3.85 ± 0.59 |

| Other/ (I decide) | 2.66 ± 1.52 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 2.66 ± 1.52 | 3.95 ± 0.45 |

| F | 14.024 | 6.308 | 17.844 | 0.419 |

| P value | < 0.001a | < 0.001a | < 0.001a | 0.740 |

| Household sharing at home | ||||

| Completely belong to female | 10.88 ± 8.36 | 4.41 ± 5.48 | 6.47 ± 3.76 | 4.02 ± 0.60 |

| Majority belongs to female | 2.82 ± 4.03 | 0.93 ± 1.90 | 1.88 ± 2.55 | 3.84 ± 0.58 |

| Majority belongs to male | 1.60 ± 2.30 | 1.40 ± 2.19 | 0.20 ± 0.44 | 4.07 ± 0.85 |

| Equal | 1.70 ± 3.87 | 1.01 ± 1.70 | 1.29 ± 2.48 | 3.84 ± 0.61 |

| F | 22.815 | 16.823 | 20.598 | 0.651 |

| P value | < 0.001a | < 0.001a | < 0.001a | 0.583 |

The present findings indicated that in contrast to what is commonly thought there is not a significant relationship between economic abuse and work performance among married female nurses and physicians. Interestingly, the findings also showed that as compared with married female physicians economic abuse by a spouse is more common and work performance is higher among married female nurses, highlighting potential differences in vulnerabilities within different professional groups. In contrast with the present findings, economic abuse typically has a negative effect on work per

Feeling trapped, lonely, and isolated along with financial stress and mounting debt can increase stress, anxiety, and distraction that can negatively affect overall work performance. The emotional and financial strain of economic abuse can decrease an individual’s ability to focus and perform their job effectively, highlighting the importance of addressing economic abuse for optimizing employee well-being and productivity[24]. A prior study supported that victims of economic abuse experienced reduced productivity and increased absenteeism due to the stress and resource deprivation associated with the abuse[25]. The present findings might differ from those of earlier studies due to differences in the participants’ resilience, support systems, or coping mechanisms. Moreover, the prevalence and/or severity of economic abuse in the present study might have been lower, decreasing its observable effects.

The unique characteristics inherent in the medical professions could indeed contribute to this unexpected finding. Nurses and physicians often exhibit a high degree of stress resistance and coping mechanisms developed through rigorous training and demanding work environments[21-23]. This inherent resilience might buffer the negative impacts of economic abuse on their work performance, allowing them to maintain professional standards despite facing financial control or exploitation in their personal lives. The demanding nature of their roles necessitates a focus on patient care, potentially overriding the personal distress caused by economic abuse at least in its manifestation within the workplace.

Moreover, the absence of significant correlation could be attributed to the presence of unmeasured mediating variables. Factors such as social support networks and psychological resilience, which were not directly assessed in our study, may play a crucial role in mitigating the impact of economic abuse on work performance. Strong social support from colleagues, friends, or family could provide emotional and practical assistance, lessening the adverse effects of financial control on an individual’s ability to function effectively at work[22]. Similarly, a high level of psychological resilience may enable individuals to better cope with the stress and emotional burden associated with economic abuse, preventing it from significantly affecting their professional output.

Future research should explore these potential mediating variables to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the relationship between economic abuse and work performance within the medical field. Although the present findings show that there is not a correlation between economic abuse and work performance, further study of this potential correlation could prove to be valuable for understanding how economic abuse affects female’s occupational outcomes and for the design of targeted interventions.

The paradoxical finding of this study that married female nurses more commonly experience economic abuse but also have higher work performance than married female physicians could be explained by several factors. Nurses often demonstrate strong dedication and resilience while performing their work that can help them maintain a high level of work performance despite personal stressors[26]. Nurses through their cultivated skills and accumulated experience often maintain a high level of professional performance despite personal hardships. This resilience can be attributed to the rigorous training they undergo and the stringent professional standards to which they adhere. These factors equip them with the ability to compartmentalize personal difficulties and consistently deliver quality patient care[26].

The medical profession while noble presents a unique set of challenges and stressors that can impact work performance, particularly when dealing with sensitive issues such as economic abuse. Both nurses and physicians experience high levels of stress, long working hours, and emotional demands[26]. However, key differences in their roles, training, and workplace dynamics may contribute to the observed performance disparity. In addition the rigorous training and continuous professional development inherent in nursing cultivates critical thinking and problem-solving skills[26]. These skills are not only applicable to patient care but also translate into an ability to navigate complex personal circumstances, such as recognizing and addressing economic abuse.

The ethical code of conduct that governs nursing practice emphasizes advocacy and patient empowerment. This ingrained sense of responsibility extends beyond the clinical setting, potentially motivating nurses to seek solutions and support systems when facing personal adversity. The collaborative nature of healthcare fosters strong interpersonal relationships and access to peer support[27]. Nurses often work in teams, creating a network of individuals who can provide emotional and practical assistance during difficult times. This pre-existing support system can be crucial in mitigating the impact of economic abuse.

Finally, the exposure to diverse patient populations and challenging medical scenarios equips nurses with a heightened sense of empathy and resilience. Witnessing the struggles of others can strengthen their own coping mechanisms and provide a different perspective on their personal challenges. Additionally, married female physicians may have different stress management strategies than married female nurses, or they may be affected by other personal or professional stressors unrelated to economic abuse to a greater degree than married female nurses.

Research suggests that married female nurses may be more vulnerable to economic abuse from their spouse than married female physicians, primarily due to differences in income, socioeconomic status, and job stability. Nurses often have lower salaries than physicians and may have less financial independence, which can increase vulnerability to financial control and abuse[28,29]. Nonetheless, the probability of experiencing financial control and abuse while present across various demographics is subject to fluctuation contingent upon cultural norms, geographic location, and indi

Additionally, the present findings suggest that age plays a significant role in experiencing economic abuse and restriction and in work performance. This indicates that the degree of vulnerability to economic abuse varies with age and warrants further research on the potential underlying factors such as accumulated assets and financial independence, dependence, social isolation, and workplace dynamics and to develop age-specific support strategies. Tailored programs should consider factors such as diminished earning potential, increased reliance on fixed incomes, potential cognitive decline, and social isolation, which can exacerbate the impact of economic abuse. Developing and implementing such targeted strategies is crucial to effectively protect and empower women across all age demographics, fostering economic security and overall well-being throughout their lives.

Mellar et al[30] observed that females aged 16-29 years had the lowest prevalence of economic abuse. Another study reported that women aged 35-54 years were more likely to have experienced emotional and economic abuse[31]. Moreover, earlier studies suggest that age is positively correlated with work performance as in the present study[32-34]. In contrast some studies show that middle-aged (in the age range of 40 to 60 or 65 years old) and elderly females experience a decrease in work performance[35,36]. These age-related differences might be due to differences in context, cultural factors, measuring methods, and the populations studied.

In the present study age was positively correlated with economic abuse and work performance, possibly indicating that as the participants aged, they were more likely to both experience economic abuse and perform better at work. The positive correlation observed in our study, indicating a potential increase in both economic abuse and work performance with age, warrants further investigation to elucidate the underlying mechanisms and contextual factors driving this association. It is plausible that older individuals, perhaps due to increased financial responsibility or dependency, are both more vulnerable to economic abuse and driven to maintain or improve work performance. In contrast, some researchers, including Thrasher et al[36] suggested that as age increases, economic abuse and work performance decrease, a difference that might be due to a difference in societal norms, support systems, or personal lifestyle and stages of career.

In the present study the level of education was associated with economic abuse as economic abuse was more common among the participants with a bachelor’s degree. Most (63.9%) of the participants in the present study had a bachelor’s degree, whereas the others had a postgraduate degree. Many studies showed that as the level of education increased the risk of experiencing violence, including economic abuse (a form of domestic violence), decreased[37]. In addition education can increase awareness, improve access to resources, and facilitate financial and personal independence, all of which serve as protective factors against economic abuse. A potential explanation for the observed correlation between bachelor’s-level nurses and physicians and a higher likelihood of experiencing economic abuse could also be related to career trajectory and earning potential within these professions. While a bachelor’s degree is often the entry point for these fields, individuals with advanced degrees (e.g., Master’s, Doctorate) may have access to higher-paying positions, specialized roles, or greater autonomy in their practice. This increased financial independence could in turn provide a buffer against economic abuse by reducing reliance on a partner or family member for financial support[37,38]. Fur

The present findings suggest that as the length of marriage increases, the likelihood and/or severity of economic abuse often increases. This might be because long-term marriages can sometimes lead to entrenched patterns of control, financial dependence, or gradual accumulation of economic power by the abuser[38]. Alternatively, economic abuse might become more evident or severe as the marriage progresses, especially if issues like financial control and exploitation are not addressed early[39].

In our study the participants who had children were more likely to experience economic abuse. Earlier studies reported that females with children may be more likely to experience economic abuse because abusers often use financial control as a way to exert power and restrict independence. While economic abuse can affect any female regardless of her parental status, females with children may face an elevated risk due to abusers exploiting the additional financial burdens and dependencies associated with child-rearing. Abusers may strategically manipulate resources, interfering with a female’s ability to provide for her children, thereby increasing her reliance on the abuser and limiting her options for leaving the abusive situation[40]. This form of control not only restricts a female’s independence but also directly impacts the well-being of her children, perpetuating a cycle of disadvantage.

Therefore, while all females are potentially susceptible to economic abuse, the presence of children can be a significant factor in increasing a female’s vulnerability to this insidious form of control. In addition having children increases the level of financial responsibility, making victims of economic abuse potentially more vulnerable to manipulation, coercion, or financial restrictions[40]. Economic abusers might also target resources related to children’s needs like schooling or healthcare to increase their leverage. Additionally, the perceived financial dependence associated with raising children can make it difficult for victims of economic abuse to leave a marriage or seek help.

The present study showed that a spouse’s level of education can significantly affect the abused perceptions of economic abuse. This might be due to the fact that as the level of education increases there is often an increase in awa

Economic abuse was more common among our participants that reported that their spouse controls the decision-making process. This finding was expected because when a spouse’s decisions are reported to be decisive or dominant regarding household choices, it is often indicative of or enables an imbalance of power, which can increase the risk of economic abuse[42]. A controlling partner might restrict access to financial resources, control how money is spent, or limit the victim’s financial independence, creating the context in which economic abuse can flourish.

Among our participants more of those that reported doing the majority of the housework were victims of economic abuse than those that reported otherwise. This finding highlighted a link between traditional gender roles and economic abuse. When females are expected to bear most of the household and domestic responsibilities, it can reinforce economic dependency and vulnerability[43]. Unequal division of housework often limits female’s economic autonomy, makes it harder for them to leave abusive situations, and can increase their exposure to economic abuse. Challenging traditional gender roles and promoting equitable sharing of household chores may help reduce female’s vulnerability to economic abuse[43].

Our findings show that place of residence, spouse’s profession, and type of marriage were not correlated with economic abuse or work performance, which could be explained by several factors. The study population might have been homogenous in terms of socioeconomic status or other variables, limiting variability and the ability to observe differences. In addition cultural norms and societal attitudes toward gender roles and marriage might have neutralized the effect of the spouse’s profession or marriage type on economic abuse and work performance. Such factors as personal resilience, support networks, or institutional policies might have had a stronger effect on economic abuse and work performance, overshadowing the effects of the spouse’s profession or marriage type[40,43].

The present study had several limitations, including the inclusion of participants that all worked at the same university hospital, limiting the generalizability of the findings. The cross-sectional design of the study might limit the conclusions on causality or changes over time. Economic abuse is a sensitive topic; as such, the participants’ questionnaire responses may have been affected by social desirability or fear, leading to underreporting. Moreover, excluding unmarried and divorced women might have led to the inability to observe different experiences or patterns of economic abuse.

In the present study the type of marriage, place of residence, and spouse’s profession were not correlated with economic abuse or work performance, indicating that economic abuse can occur regardless of type of marriage, place of residence, or spouse’s profession. This indicates that economic abuse is widespread and not limited by these factors and that other variables such as power dynamics or personal attitudes might play a larger role.

The present findings showed that there is no relationship between economic abuse and work performance, confirming that more married female nurses are victims of economic abuse and have a higher level of work performance than married female physicians. Age and profession were factors affecting both economic exploitation and individual work performance. Furthermore, level of education, spouse’s level of education, having children, the decision-making process at home, and sharing of household chores all played a role in economic abuse.

A greater effort is needed to better protect females against economic abuse. A better understanding of gender specificity in society is vital for improving the prevention, detection, and response to the economic abuse of females. The inclusion of gender-specific education in public and private schools is essential for providing appropriate services to females who are at risk of economic abuse.

We present our sincere thanks to the participants included in the study. Also, thanks to the authors for their efforts to develop and validate the measurements that we used in our research.

| 1. | Postmus JL, Nikolova K, Lin HF, Johnson L. Women's Economic Abuse Experiences: Results from the UN Multi-Country Study on Men and Violence in Asia and the Pacific. J Interpers Violence. 2022;37:NP13115-NP13142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Adams AE, Beeble ML, Biswas A, Flynn RL, Vollinger L. An Exploratory Study of Financial Health as an Antecedent of Economic Abuse Among Women Seeking Help for Intimate Partner Violence. Violence Against Women. 2024;30:3825-3853. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Boateng JD, Tenkorang EY, Issahaku P. Economic Abuse of Women in Intimate Relationships in Ghana: Consequences and Coping Strategies. Violence Against Women. 2024;30:2032-2052. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Christy K, Welter T, Dundon K, Valandra, Bruce A. Economic Abuse: A Subtle but Common Form of Power and Control. J Interpers Violence. 2022;37:NP473-NP499. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Abusbaitan HA, Eyadat AM, Holt JM, Telfah RK, Zahra TFA, Zahra TFA, Mobarki AA, Mkandawire-Valhmu L, Kako PM, Gondwe KW, Lopez AA. Emotional Abuse Against Women in the Context of Intimate Relationships: A Concept Analysis. Nursing Forum. 2025;2025. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 6. | Bruno L, Strid S, Ekbrand H. Men's Economic Abuse Toward Women in Sweden: Findings From a National Survey. Violence Against Women. 2025;31:2194-2218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Lyons M, Brewer G. Experiences of Intimate Partner Violence during Lockdown and the COVID-19 Pandemic. J Fam Violence. 2022;37:969-977. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 15.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kaittila A, Hakovirta M, Kainulainen H. Types of Economic Abuse in Postseparation Lives of Women Experiencing IPV: A Qualitative Study from Finland. Violence Against Women. 2024;30:426-444. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Adu C, Asare BY, Agyemang-Duah W, Adomako EB, Agyekum AK, Peprah P. Impact of socio-demographic and economic factors on intimate partner violence justification among women in union in Papua New Guinea. Arch Public Health. 2022;80:136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Alsawalqa RO. Economic Abuse of Women in Amman, Jordan: A Quantitative Study. Sage Open. 2020;10. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 11. | Anitha S. Understanding Economic Abuse Through an Intersectional Lens: Financial Abuse, Control, and Exploitation of Women's Productive and Reproductive Labor. Violence Against Women. 2019;25:1854-1877. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lanchimba C, Díaz-Sánchez JP, Velasco F. Exploring factors influencing domestic violence: a comprehensive study on intrafamily dynamics. Front Psychiatry. 2023;14:1243558. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Akram T, Muhammad N, Ramakrishnan S. How does financial inclusion act as a catalyst for reducing financial crime among women? J Financ Crime. 2025;32:279-287. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 14. | Adams AE, Sullivan CM, Bybee D, Greeson MR. Development of the scale of economic abuse. Violence Against Women. 2008;14:563-588. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 197] [Cited by in RCA: 168] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Wathen CN, MacGregor JC, MacQuarrie BJ. The Impact of Domestic Violence in the Workplace: Results From a Pan-Canadian Survey. J Occup Environ Med. 2015;57:e65-e71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Adams AE, Greeson MR, Littwin AK, Javorka M. The Revised Scale of Economic Abuse (SEA2): Development and initial psychometric testing of an updated measure of economic abuse in intimate relationships. Psychol Violence. 2020;10:268-278. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 17. | Salimi H, Hosseinkhani A, Beeble ML, Samavi SA. Examining the Psychometric Properties of the Revised Scale of Economic Abuse among Iranian Women. J Interpers Violence. 2023;38:12067-12088. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Koopmans L, Bernaards C, Hildebrandt V, van Buuren S, van der Beek AJ, de Vet HC. Development of an individual work performance questionnaire. Int J Prod Perf Mgmt. 2012;62:6-28. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Koopmans L, Bernaards CM, Hildebrandt VH, Lerner D, de Vet HCW, van der Beek AJ. Individual Work Performance Questionnaire--American-English Version. APA PsycTests. 2016;. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 20. | Kaba N, Ozturk H. Validity and Reliability of Turkish Version of the Individual Work Performance Questionnaire. J Health Nurs Manage. 2021;8:293-302. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 21. | Chia CS, Wong SSL, Chew KS, Nur Amira Aina binti Zulkarnian. Unlocking the Hidden Side of Economic Abuse in Malaysia. Int J Bus Soc. 2022;23:1908-1920. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 22. | Fotinatos-Ventouratos R, Cooper C. The origin of the economic crisis. Econ Crisis Occup Stress. 2015;. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 23. | Wei X, Wei X, Yu X, Ren F. The Relationship Between Financial Stress and Job Performance in China: The Role of Work Engagement and Emotional Exhaustion. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2024;17:2905-2917. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Attipoe V, Oyeyipo I, Christiana Ayodeji D, Joan Isibor N, Apiyo Mayienga B, Alonge E, Clement Onwuzulike O. Economic Impacts of Employee Well-being Programs: A Review. Int J Adv Multidisciplinary Res Stud. 2025;5:852-860. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 25. | Wessells MG, Kostelny K. The Psychosocial Impacts of Intimate Partner Violence against Women in LMIC Contexts: Toward a Holistic Approach. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:14488. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Henshall C, Davey Z, Jackson D. Nursing resilience interventions-A way forward in challenging healthcare territories. J Clin Nurs. 2020;29:3597-3599. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Osborn M, Ball T, Rajah V. Peer Support Work in the Context of Intimate Partner Violence: A Scoping Review. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2024;25:4261-4276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Abolfotouh MA, Almuneef M. Prevalence, pattern and factors of intimate partner violence against Saudi women. J Public Health (Oxf). 2020;42:e206-e214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Alshammari A, Evans C, Mcgarry J. Nurses' experiences of perceiving violence and abuse of women in Saudi Arabia: A phenomenological study. Int Nurs Rev. 2023;70:501-509. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Mellar BM, Fanslow JL, Gulliver PJ, McIntosh TKD. Economic Abuse by An Intimate Partner and Its Associations with Women's Socioeconomic Status and Mental Health. J Interpers Violence. 2024;39:4415-4437. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Nduka CC, Omuemu V, Adedayo T, Adogu P, Ifeadike C. Prevalence and Correlates of Economic Abuse Among Married Women in a Nigerian Population. J Interpers Violence. 2024;39:811-827. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Kotur BR, Anbazhagan S. Influence of Age and Gender on the Performance. IOSR J Bus Manage. 2014;16:97-103. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 33. | Karanika-Murray M, Van Veldhoven M, Michaelides G, Baguley T, Gkiontsi D, Harrison N. Curvilinear Relationships Between Age and Job Performance and the Role of Job Complexity. Work, Aging Retirement. 2024;10:156-173. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 34. | Antoine L, Deoliveira S, Ahearn S. The Influence of Age and Gender on Work-Life Balance and Job Satisfaction among Department Chairs at Academic Health Centers. Open J Ladership. 2024;13:279-289. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 35. | Ryan L, Gatrell C. How are middle‐ and older‐age women employees perceived and treated at work? A review and analysis. Int J Manage Rev. 2024;26:536-555. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 36. | Thrasher GR, Wynne K, Baltes B, Bramble R. The intersectional effect of age and gender on the work–life balance of managers. J Manage Psychol. 2022;37:683-696. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | D’agostino F, Zacchia G, Corsi M. Risk of Economic Violence: A New Quantification. Int J Financial Stud. 2024;12:82. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 38. | Byrt A, Cook K, Burgin R. Addressing Economic Abuse in Intimate-partner Violence Interventions: A Bacchian Analysis of Responsibility. J Fam Viol. 2025;40:419-433. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 39. | Ranganathan M, Stern E, Knight L, Muvhango L, Molebatsi M, Polzer-Ngwato T, Lees S, Stöckl H. Women's economic status, male authority patterns and intimate partner violence: a qualitative study in rural North West Province, South Africa. Cult Health Sex. 2022;24:717-734. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Stylianou AM. Economic Abuse Experiences and Depressive Symptoms among Victims of Intimate Partner Violence. J Fam Viol. 2018;33:381-392. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 41. | Johnson L, Chen Y, Stylianou A, Arnold A. Examining the impact of economic abuse on survivors of intimate partner violence: a scoping review. BMC Public Health. 2022;22:1014. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Park SY. Judicial Decision-Making in Intimate Partner Violence Cases: A Scoping Review and Critical Analysis. Fam Transit. 2025;66:108-135. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 43. | Naz F, Saqib SE. Gender-based differences in flood vulnerability among men and women in the char farming households of Bangladesh. Nat Hazard. 2021;106:655-677. [DOI] [Full Text] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/