Published online Dec 19, 2025. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v15.i12.111320

Revised: September 11, 2025

Accepted: October 9, 2025

Published online: December 19, 2025

Processing time: 113 Days and 1.5 Hours

Breast cancer is one of the most common cancers among women worldwide, often leading to significant emotional and psychological stress. This stress is com

To evaluate the effects of MBCT on parenting anxiety, negative emotions, quality of life (QoL), and self-efficacy in patients with breast cancer.

This retrospective study involved 249 patients with breast cancer admitted between January 2024 and December 2024. Participants were divided into two groups: The conventional treatment group (n = 123) and the MBCT group (n = 126), based on chosen treatment methods. Interventions lasted 8 weeks, with one session per week. Outcomes were measured using standardized questionnaires, including parenting anxiety [parenting concerns questionnaire (PCQ)], parenting sense of competence [parenting sense of competence scale (PSOCS)], negative emotions (self-rating anxiety scale and self-rating depression scale), hospital anxiety and depression [hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS)], trauma-related distress [impact of event scale-revised (IES-R)], mindfulness (five-facet mindfulness questionnaire), QoL [functional assessment of cancer therapy-breast (FACT-B)], symptom severity (numeric rating scales), and self-efficacy [general self-efficacy scale (GSES)].

Post-treatment, the MBCT group showed a marked reduction in parenting anxiety scores (PCQ: MBCT 50.54 ± 4.65 vs conventional 52.12 ± 5.53, P = 0.016) and notable improvement in parenting competence (PSOCS total: MBCT 61.56 ± 4.65 vs conventional 59.75 ± 4.96, P = 0.003). The MBCT group also exhibited significant reductions in anxiety (HADS anxiety: MBCT 6.78 ± 1.65 vs conventional 7.31 ± 2.08, P = 0.027) and trauma-related distress (IES-R intrusion: P = 0.030; avoidance: P = 0.004; hyperarousal: P = 0.035). QoL scores significantly improved in the MBCT group in terms of physiological condition (FACT-B: MBCT 13.85 ± 3.93 vs conventional 12.55 ± 2.75, P = 0.003) and functional status (P = 0.010). Enhanced self-efficacy was observed in strategic effectiveness (GSES: MBCT 9.87 ± 0.75 vs conventional 9.72 ± 0.13, P = 0.029).

MBCT significantly reduces parenting anxiety and enhances self-efficacy, QoL, and emotional regulation in patients with breast cancer.

Core Tip: This study demonstrates that mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) significantly reduces parenting anxiety and improves emotional regulation, self-efficacy, and quality of life in breast cancer patients. Unlike conventional care, MBCT specifically targets parenting-related distress and enhances mindfulness skills, offering a holistic approach to psychological support during cancer treatment.

- Citation: Wang WN, Wu DN, Xie YL, Wang JX, Fan XY, Li SY. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy reduces parenting anxiety and enhances quality of life in patients with breast cancer. World J Psychiatry 2025; 15(12): 111320

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v15/i12/111320.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v15.i12.111320

Breast cancer is a highly prevalent malignancy among women globally, posing a significant public health challenge. Its diagnosis and treatment involve life-altering events that frequently cause considerable emotional and psychological distress[1-3]. Patients are confronted with the physical demands of treatment and significant psychological sequelae, including heightened anxiety, depression, and fear of cancer recurrence[4,5]. This psychological burden is frequently exacerbated by specific concerns related to their parenting roles, particularly anxieties about the potential effects of their illness and treatment on their children's well-being; this aspect is termed "parenting anxiety"[6,7]. Parenting anxiety includes concerns about the actual consequences on the child (e.g., disruptions in care and routines) and the emotional repercussions for the child (e.g., distress and fear), contributing substantially to overall distress and potentially di

Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) has emerged as a promising psychosocial intervention. Originally developed to prevent relapse in recurrent depression, MBCT integrates principles of cognitive behavioral therapy with mindfulness meditation practices. Its core principles involve fostering non-judgmental awareness of current experiences (thoughts, emotions, and physical sensations) and developing skills to detach from habitual, often negative, cognitive patterns. By fostering acceptance and altering the relationship to distressing thoughts and feelings, MBCT aims to enhance emotional regulation and reduce vulnerability to anxiety and depressive symptoms. Preliminary evidence supports its efficacy in reducing distress, anxiety, and depression in various populations, including individuals with cancer[10-12].

Although MBCT's benefits for general anxiety and depression in patients with breast cancer are widely recognized, its specific effects on parenting anxiety and perceived self-efficacy remain underexplored. These domains are crucial because they encompass emotional well-being and the patients' perception of their ability to effectively manage their role as parents amid ongoing treatment for cancer. Self-efficacy, or the belief in one's capacity to conduct actions necessary to achieve specific outcomes, is an important psychological asset that can enhance emotional resilience and encourage proactive involvement in life's challenges[13,14]. Enhancing self-efficacy among patients with breast cancer may facilitate improved coping strategies, thereby reducing the psychological burden associated with their illness and its perceived effects on their children.

Furthermore, the QoL in patients with breast cancer is a pressing concern, influencing treatment outcomes and overall patient satisfaction. QoL includes various characteristics, including physical health, psychological state, level of inde

This study aimed to evaluate the effect of MBCT on parenting anxiety, negative emotions, QoL, and self-efficacy in patients with breast cancer. By addressing these complex dimensions through MBCT, this study contributes to the expanding body of evidence supporting psychosocial interventions in cancer care. It hypothesizes that MBCT leads to significant improvements in reducing parenting anxiety and negative emotions while enhancing self-efficacy and QoL compared with conventional treatments. The findings from this investigation may guide comprehensive therapeutic strategies that address the physical, psychological, and social needs of patients with breast cancer, thereby promoting holistic and patient-centered care.

This research represents a critical step toward understanding and addressing the complex needs of patients with breast cancer, providing evidence-based insights into innovative interventions that support mental and physical health outcomes.

The study samples were chosen from a cohort of 249 patients with breast cancer admitted to the Fourth Hospital of Hebei Medical University between January 2024 and December 2024. These patients displayed varying levels of concerns related to parenting. Demographic data were collected from the hospital's case system. Patients were categorized into two groups based on their selected treatment options: The conventional treatment group (n = 123) and the MBCT group (n = 126).

This retrospective study utilized de-identified patient data, which did not affect the medical care of patients; thus, informed consent was not required. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Fourth Hospital of Hebei Medical University and adhered to the guidelines outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Inclusion criteria: (1) Participants eligible for this study were those who had been diagnosed with breast cancer by a physician[16]; (2) In stage I or II of the disease; (3) Possessed adequate cognitive and language abilities to comprehend the intervention content and complete the study questionnaires; (4) No history of drug or alcohol abuse; and (5) No previous psychotherapy.

Exclusion criteria: (1) Impaired consciousness; (2) Pre-existing mental disorders; (3) Other severe illnesses; (4) Failure to complete more than one session; (5) Experienced irritation or deterioration during the study; and (6) Recent traumatic or distressing events within the past 6 months (e.g., loss of a close person, non-cancer diagnosis, divorce, or chronic illness other than cancer).

Patients were assigned to either a conventional treatment group or an MBCT group, depending on their chosen treatment method. The total duration was 8 weeks, with sessions once a week. Specific treatment approaches were as follows:

Conventional treatment group: This group received routine nursing care, which included standard health education regarding breast cancer, treatment side effects, and self-management; daily care support, including hygiene and comfort measures; dietary guidance tailored to nutritional needs during cancer treatment; and medication management, including adherence counseling and side effect monitoring. Each session lasted 2-2.5 hours and was conducted once per week for 8 weeks.

MBCT group: In addition to conventional treatments, this group received MBCT, which was delivered over eight weekly sessions. The intervention was facilitated by a multidisciplinary team led by a research leader and included psychologists with over 2 years of clinical experience as mentors, along with experienced nurses. The MBCT program's psychological care process was conducted over eight weekly sessions, each lasting 2-2.5 hours. The content was structured to pro

Foundation and present-moment awareness (weeks 1 and 2): Week 1: Recognizing habitual patterns (e.g., through blind food observation using non-visual senses). Week 2: Cultivating present-moment focus through core practices: Sitting meditation (focusing on breath/body sensations), walking meditation (mindful awareness of movement/environment), and mindful listening (attending to sounds and internal states).

Deepening attention and working with thoughts/emotions (weeks 3 and 4): Week 3: Developing concentration and body awareness through observation meditation (observing breath) and body scan exercises (systematically scanning bodily sensations). Week 4: Recognizing and allowing emotional experiences without judgment (emotion perception exercise) and observing the flow of thoughts without attachment (mindfulness exercise).

Integration and application (weeks 5-8): Week 5: Practicing acceptance ("allowing") using integrated practices like mindful eating, body scan, and listening. Week 6: Understanding the nature of thoughts (distinguishing thoughts from reality), including a dedicated "mindfulness day". Week 7: Cultivating self-compassion and self-care through sitting, walking, and general mindfulness meditation. Week 8: Consolidating learning and integrating mindfulness practices into daily life, encouraging ongoing practice.

Before and after treatment, relevant questionnaire surveys were administered to participants in the conventional treat

Parenting concerns questionnaire: This tool assessed parenting concerns across three dimensions: Actual impact on children, emotional impact on children, and concerns from the parents. It included 15 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale, where "not worried" was assigned a score of 1 and "extremely worried" was assigned a score of 5. The score for each dimension was calculated as an average, with elevated values indicating increased parental anxiety among patients with cancer. The Cronbach's alpha coefficient in this study was 0.94[17].

Parenting sense of competence scale: This scale measured parents' perceptions of their competence in the parenting role. It consisted of 17 items rated on a 6-point Likert scale, with higher scores indicating greater parenting self-efficacy. The scale included two subscales: Satisfaction (9 items) and efficacy (8 items). The Cronbach’s alpha of this scale was 0.872[18].

Self-rating anxiety scale: This scale evaluated the subjective anxiety level of patients through 20 items rated on a 4-point Likert scale. The total gross score was multiplied by 1.25 to obtain a standard score. Scores of 50 and above indicated anxiety, with categories of mild (50-59), moderate (60-69), and severe anxiety (≥ 70). Elevated scores reflected increased severity of anxiety levels. The Cronbach's alpha for self-rating anxiety scale (SAS) was 0.911[19].

Self-rating depression scale: This scale assessed subjective depression over 20 items, each rated on a 4-point Likert scale. The standard score was calculated by multiplying the total gross score by 1.25, with a cutoff of 53. Scores of 53 or above indicated depression, categorized as mild (53-62), moderate (63-72), and severe (≥ 73). Higher scores signified greater severity of depression. The Cronbach's alpha for the self-rating depression scale (SDS) was 0.74[20].

Hospital anxiety and depression scale: This 14-item scale assessed symptoms of anxiety (7 items) and depression (7 items) in non-psychiatric hospital settings. Each item was scored from 0 to 3, with subscale scores ranging from 0 to 21. Elevated scores indicated increased symptom severity. The Cronbach’s alpha for the anxiety and depression subscales were 0.80 and 0.76, respectively[21].

Impact of event scale-revised: This 22-item self-report measure evaluated subjective distress in response to traumatic events. It included three subscales: Intrusion (8 items), avoidance (8 items), and hyperarousal (6 items). Items were rated on a 5-point scale from 0 (“not at all”) to 4 (“extremely”). Total scores ranged from 0 to 88, with elevated scores indicating increased distress. The Cronbach's alpha of each subscale was 0.88-0.94[22].

Five-facet mindfulness questionnaire: The five-facet mindfulness questionnaire (FFMQ) is a 39-item self-report instrument designed to assess five distinct dimensions of mindfulness: Observing, describing, acting with awareness, non-judging of inner experience, and non-reactivity to inner experience. Each item was rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“never or very rarely true”) to 5 (“very often or always true”). Subscale scores were calculated by summing the items within each facet, with high scores indicating enhanced mindfulness abilities. The FFMQ has demon

Functional assessment of cancer therapy-breast: This scale included a general component and a breast cancer-specific subscale, spanning five dimensions and 36 items: Physical status, social and family status, emotional status, functional status, and additional concerns. Responses ranged from 0 to 4, with reverse-scored items. The total score ranged from 1 to 144, with higher scores indicating better QoL. The total functional assessment of cancer therapy-breast (FACT-B) had a Cronbach's alpha of 0.87[24].

Numeric rating scales: The numeric rating scales (NRSs) were used to subjectively assess the intensity of various symptoms, such as pain, fatigue, or distress, on an 11-point scale from 0 to 10, where 0 represents “no symptom” and 10 represents “the worst imaginable symptom”. Participants were asked to circle the number that best corresponds to their current experience. The NRSs are widely used in clinical settings due to their simplicity, ease of administration, and strong correlation with comprehensive measures of symptom burden[25].

General self-efficacy scale: This scale measured self-efficacy across 10 items using a 4-point scoring method, yielding total scores ranging from 10 to 40. Higher scores indicated greater self-efficacy. The Cronbach's alpha for general self-efficacy scale (GSES) was 0.89[26].

Data were collected at three stages: Pre-treatment, post-treatment, and follow-up, from the conventional treatment group and the MBCT group. The completed questionnaires were scored and analyzed using SPSS software version 20 (Released 2011. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 20.0, Armonk, NY, United States: IBM Corp). Statistical measures including mean, standard deviation, frequency, and percentage were employed to describe the data. A χ2 test was used to compare the demographic characteristics of the groups. To evaluate differences between groups across the different time points (pre-treatment, post-treatment, and follow-up), we conducted repeated measures ANOVA. Tukey’s test was applied to assess differences between the groups before and after treatment. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Sociodemographic characteristics were comparable between the MBCT and conventional treatment groups (Table 1). No significant differences were observed in age, religious affiliation, education level, employment status, number of underage children, age of the youngest child, or average monthly income (all P > 0.05), indicating that the groups were well-matched at baseline.

| Indicator | Conventional treatment group (n = 123) | MBCT group (n = 126) | t/χ2 | P value |

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 56.70 ± 8.10 | 56.80 ± 9.99 | 0.083 | 0.934 |

| Religion | 0.494 | 0.482 | ||

| No | 101 (82.11) | 99 (78.57) | ||

| Yes | 22 (17.89) | 27 (21.43) | ||

| Education level | 0.215 | 0.643 | ||

| Less than high school | 69 (56.10) | 67 (53.17) | ||

| Some college or higher education | 54 (43.90) | 59 (46.83) | ||

| Employment status | 1.681 | 0.641 | ||

| Full- or part-time used | 47 (38.21) | 53 (42.06) | ||

| Unemployed or on sickness -benefit | 16 (13.01) | 21 (16.67) | ||

| Retired | 51 (41.46) | 43 (34.13) | ||

| Missing | 9 (7.32) | 9 (7.14) | ||

| Number of underage children | 4.31 | 0.116 | ||

| 1 | 89 (72.36) | 79 (62.70) | ||

| 2 | 23 (18.70) | 25 (19.84) | ||

| ≥ 3 | 11 (8.94) | 22 (17.46) | ||

| The age of the youngest minor child (year) | 4.549 | 0.103 | ||

| < 6 | 21 (17.07) | 33 (26.19) | ||

| 6-12 | 32 (26.02) | 37 (29.37) | ||

| 12-18 | 70 (56.91) | 56 (44.44) | ||

| Average monthly income in RMB | 0.976 | 0.614 | ||

| ≥ 5000 | 33 (26.83) | 29 (23.02) | ||

| 3000-4999 | 61 (49.59) | 61 (48.41) | ||

| ≤ 3000 | 29 (23.58) | 36 (29.57) |

In this study, clinical characteristics of patients in the MBCT group and the conventional treatment group were compared (Table 2). Breast cancer stage distribution was similar, with stage I encompassing 15.45% in the conventional group and 16.67% in the MBCT group, and stage II comprising 84.55% and 83.33%, respectively, showing no significant difference (χ² = 0.069, P = 0.793). The duration of disease and body mass index (BMI) were comparable across groups (disease duration: χ² = 0.406, P = 0.816; BMI: = 1.369, P = 0.172). Relapse rates were low and similar (conventional: 1.63%, MBCT: 2.38%; χ² = 0.000, P = 1.000). Tumor size did not differ significantly between groups, but a tendency toward significance was observed (χ² = 5.319, P = 0.070). The TNM classification also showed no significant difference (χ² = 0.549, P = 0.76). However, significant differences were observed in the type of surgery, with a higher rate of lumpectomy in the MBCT group (57.94%) than in the conventional group (52.72%) and a diminished rate of mastectomy (MBCT: 42.06%, conventional: 55.28%; χ² = 4.355, P = 0.037). Chemotherapy regimens, rates of breast reconstruction, and axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) were similar between the groups, with no statistically significant differences observed (chemotherapy scheme: χ² = 2.553, P = 0.279; breast reconstruction: χ² = 3.089, P = 0.079; ALND: χ² = 0.096, P = 0.953). These findings indicated the two groups were largely comparable in terms of their clinical profiles, except for the difference in surgical approaches.

| Indicator | Conventional treatment group (n = 123) | MBCT group (n = 126) | t/χ2 | P value |

| Breast cancer stage | 0.069 | 0.793 | ||

| I | 19 (15.45) | 21 (16.67) | ||

| II | 104 (84.55) | 105 (83.33) | ||

| Disease duration (year) | 0.406 | 0.816 | ||

| 1-5 | 35 (28.46) | 40 (31.75) | ||

| 5-10 | 40 (32.52) | 41 (32.54) | ||

| 10-15 | 48 (39.02) | 45 (35.71) | ||

| BMI, mean ± SD | 22.90 ± 3.60 | 22.30 ± 3.30 | 1.369 | 0.172 |

| Relapse | 0.000 | 1.000 | ||

| Yes | 2 (1.63) | 3 (2.38) | ||

| No | 121 (98.37) | 123 (97.62) | ||

| Tumor size (mm) | 5.319 | 0.07 | ||

| ≤ 20 | 51 (41.46) | 59 (46.83) | ||

| 20-50 | 57 (46.34) | 42 (33.33) | ||

| > 50 | 15 (12.20) | 25 (19.84) | ||

| TNM | 0.549 | 0.76 | ||

| T1N1M0 | 13 (10.57) | 17 (13.49) | ||

| T2N1M0 | 64 (52.03) | 65 (51.59) | ||

| T2N0M0 | 46 (37.46) | 44 (34.92) | ||

| Type of surgery | 4.355 | 0.037 | ||

| Mastectomy | 68 (55.28) | 53 (42.06) | ||

| Lumpectomy | 65 (52.72) | 73 (57.94) | ||

| Chemotherapy scheme | 2.553 | 0.279 | ||

| AC-T | 86 (69.92) | 83 (65.87) | ||

| TAC | 9 (7.32) | 17 (13.49) | ||

| TC | 28 (22.76) | 26 (20.63) | ||

| Breast reconstruction | 3.089 | 0.079 | ||

| Yes | 16 (13.01) | 27 (21.43) | ||

| No | 107 (86.99) | 99 (78.57) | ||

| ALND | 0.096 | 0.953 | ||

| Yes | 58 (47.15) | 57 (45.24) | ||

| No | 63 (51.22) | 67 (53.17) | ||

| Not reported | 2 (1.63) | 2 (1.59) |

Prior to treatment, total scores for the parenting concerns questionnaire (PCQ) were 58.35 ± 10.54 for the conventional group and 59.65 ± 9.52 for the MBCT group (t = 1.025, P = 0.306; Table 3). In terms of specific concerns, scores for actual impact on children were 22.76 ± 4.65 in the conventional group compared with 23.32 ± 3.65 in the MBCT group (t = 1.050, P = 0.295), whereas concerns about the emotional impact on children were 25.76 ± 4.75 in the conventional group and 25.52 ± 4.36 in the MBCT group (t = 0.413, P = 0.680). Although we noted a trend toward significance in concerns regarding the parental role, with scores of 14.65 ± 3.65 in the conventional group and 13.75 ± 3.65 in the MBCT group (t = 1.948, P = 0.053), the difference did not reach statistical significance. Additionally, the parenting sense of competence scale (PSOCS) total scores showed no significant difference, with scores of 53.67 ± 3.28 for the conventional group and 52.76 ± 4.54 for the MBCT group (t = 1.814, P = 0.071). Sub-scores for parenting effectiveness and satisfaction were similarly non-significant across groups. Thus, these results suggested baseline equivalence in parenting anxiety and perceived compe

| Item | Time | Conventional treatment group (n = 123) | MBCT group (n = 126) | t value | P value |

| PCQ (score) | |||||

| Total | Before | 58.35 ± 10.54 | 59.65 ± 9.52 | 1.025 | 0.306 |

| After | 52.12 ± 5.53 | 50.54 ± 4.65 | 2.431 | 0.016 | |

| Concerns about the actual impact on children | Before | 22.76 ± 4.65 | 23.32 ± 3.65 | 1.050 | 0.295 |

| After | 20.85 ± 0.69 | 19.65 ± 7.96 | 1.679 | 0.096 | |

| Concerns about the emotional impact on children | Before | 25.76 ± 4.75 | 25.52 ± 4.36 | 0.413 | 0.680 |

| After | 23.91 ± 4.79 | 22.56 ± 4.56 | 2.269 | 0.024 | |

| Concerns about the father/mother of the child | Before | 14.65 ± 3.65 | 13.75 ± 3.65 | 1.948 | 0.053 |

| After | 11.36 ± 3.60 | 10.64 ± 3.34 | 1.626 | 0.105 | |

| PSOCS (score) | |||||

| Total | Before | 53.67 ± 3.28 | 52.76 ± 4.54 | 1.814 | 0.071 |

| After | 59.75 ± 4.96 | 61.56 ± 4.65 | 2.969 | 0.003 | |

| Parenting effectiveness | Before | 24.78 ± 2.86 | 24.78 ± 3.65 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| After | 29.24 ± 1.22 | 30.76 ± 9.28 | 1.824 | 0.07 | |

| Parenting satisfaction | Before | 30.15 ± 0.46 | 29.57 ± 8.52 | 0.753 | 0.453 |

| After | 34.51 ± 3.00 | 34.67 ± 2.83 | 0.446 | 0.656 |

After treatment, total scores on the PCQ showed a significantly greater reduction in the MBCT group (50.54 ± 4.65) than in the conventional treatment group (52.12 ± 5.53; t = 2.431, P = 0.016). Specifically, concerns about the emotional impact on children significantly decreased in the MBCT group (22.56 ± 4.56) vs the conventional group (23.91 ± 4.79; t = 2.269, P = 0.024). However, concerns regarding the actual impact on children and the parental role were not statistically different between the groups. On the PSOCS, the MBCT group reported significantly higher total scores (61.56 ± 4.65) than the conventional group (59.75 ± 4.96; t = 2.969, P = 0.003), indicating enhanced overall parenting competence post-treatment. We found a trend toward improved parenting effectiveness in the MBCT group, but the difference did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.07). Parenting satisfaction remained similar between the groups. These results suggested that MBCT was effective in reducing certain aspects of parenting anxiety and enhancing perceived parenting competence among patients with breast cancer.

Prior to treatment, the SAS total scores were comparable between the conventional treatment group (66.83 ± 3.25) and the MBCT group (67.56 ± 8.45; t = 0.898, P = 0.371; Table 4). Similarly, total scores for the SDS and the hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS) showed no significant differences between the groups (SDS total: t = 0.887, P = 0.376; HADS total: t = 0.713, P = 0.477). Specific subscales for HADS, including anxiety and depression scores, were similar across groups (HADS anxiety: t = 0.517, P = 0.606; HADS depression: t = 0.675, P = 0.500). The impact of event scale-revised (IES-R) scores, including subdivisions for intrusion, avoidance, and hyperarousal, did not vary significantly between the groups (IES-R total: t = 0.620, P = 0.536; intrusion: t = 0.665, P = 0.507; avoidance: t = 0.999, P = 0.319; hyperarousal: t = 1.345, P = 0.180). Total scores on the FFMQ also showed no significant differences (t = 0.397, P = 0.692). These results indicated that participants in both groups were similar in terms of their baseline psychological states, facilitating the evaluation of treatment effects without bias from initial disparities.

| Item | Time | Conventional treatment group (n = 123) | MBCT group (n = 126) | t value | P value |

| SAS (score) | Before | 66.83 ± 3.25 | 67.56 ± 8.45 | 0.898 | 0.371 |

| After | 59.74 ± 10.41 | 57.28 ± 9.74 | 1.924 | 0.055 | |

| SDS (score) | Before | 72.95 ± 2.83 | 73.56 ± 7.12 | 0.887 | 0.376 |

| After | 65.86 ± 5.41 | 64.84 ± 5.87 | 1.425 | 0.155 | |

| HADS (score) | |||||

| Total | Before | 17.32 ± 3.45 | 17.62 ± 3.17 | 0.713 | 0.477 |

| After | 15.63 ± 3.65 | 14.71 ± 3.89 | 1.930 | 0.055 | |

| Anxiety | Before | 8.95 ± 4.16 | 9.22 ± 3.96 | 0.517 | 0.606 |

| After | 7.31 ± 2.08 | 6.78 ± 1.65 | 2.226 | 0.027 | |

| Depression | Before | 8.14 ± 3.22 | 7.89 ± 2.53 | 0.675 | 0.500 |

| After | 6.42 ± 2.34 | 5.89 ± 2.12 | 1.882 | 0.061 | |

| IES-R (score) | |||||

| Total | Before | 36.84 ± 7.54 | 37.54 ± 10.16 | 0.620 | 0.536 |

| After | 29.35 ± 6.64 | 27.65 ± 7.14 | 1.945 | 0.053 | |

| Intrusion | Before | 14.86 ± 3.56 | 14.56 ± 3.64 | 0.665 | 0.507 |

| After | 14.86 ± 5.46 | 13.56 ± 3.64 | 2.191 | 0.030 | |

| Avoidance | Before | 11.84 ± 2.54 | 12.17 ± 2.75 | 0.999 | 0.319 |

| After | 11.35 ± 1.38 | 10.84 ± 1.35 | 2.906 | 0.004 | |

| Hyperarousal | Before | 10.35 ± 4.64 | 11.04 ± 3.38 | 1.345 | 0.180 |

| After | 7.53 ± 2.97 | 6.86 ± 1.84 | 2.123 | 0.035 | |

| FFMQ (score) | Before | 111.64 ± 18.76 | 112.56 ± 17.58 | 0.397 | 0.692 |

| After | 125.68 ± 23.79 | 133.57 ± 19.63 | 2.853 | 0.005 |

Following treatment, although total scores on the SAS, SDS, HADS, and IES-R did not show statistically significant differences (SAS total: t = 1.924, P = 0.055; SDS total: t = 1.425, P = 0.155; HADS total: t = 1930, P = 0.055; IES-R total: t = 1.945, P = 0.053), the HADS anxiety subscale demonstrated a significant reduction in the MBCT group (6.78 ± 1.65) compared with the conventional group (7.31 ± 2.08; t = 2.226, P = 0.027). Additionally, within the IES-R, substantial improvements were noted for the MBCT group, with low scores in the intrusion and avoidance subscales (intrusion: t = 2.191, P = 0.030; avoidance: t = 2.906, P = 0.004) and a significant reduction in hyperarousal (t = 2.123, P = 0.035), indicating decreased psychological distress. The total scores for FFMQ showed significant improvements in the MBCT group compared with the conventional group (P = 0.005).

Prior to treatment, the FACT-B scale revealed no significant difference in physiological condition (t = 1.038, P = 0.300), social family well-being (t = 1.402, P = 0.162), emotional well-being (t = 0.392, P = 0.695), breast symptoms (t = 1.151, P = 0.251), or total score of QoL (t = 0.328, P = 0.743) between the MBCT group and the conventional treatment group. Functional status scores were also not significantly different (t = 1.962, P = 0.051; Table 5). The NRS total score indicated no significant difference in discomfort levels (t = 1.755, P = 0.081) between the two groups. Grip strength showed no significant difference (t = 0.440, P = 0.660). Shoulder flexion and shoulder abduction did not show significant differences (P > 0.05) between the two groups.

| Item | Time | Conventional treatment group (n = 123) | MBCT group (n = 126) | t value | P value |

| FACT-B (score) | |||||

| Physiological Condition | Before | 12.58 ± 4.08 | 13.13 ± 4.22 | 1.038 | 0.300 |

| After | 12.55 ± 2.75 | 13.85 ± 3.93 | 3.012 | 0.003 | |

| Social family | Before | 20.13 ± 5.77 | 19.25 ± 3.87 | 1.402 | 0.162 |

| After | 18.18 ± 4.13 | 18.55 ± 1.26 | 0.955 | 0.341 | |

| Emotional well-being | Before | 10.85 ± 2.45 | 11 ± 3.51 | 0.392 | 0.695 |

| After | 11.95 ± 0.32 | 12.25 ± 2.51 | 1.325 | 0.188 | |

| Functional Status | Before | 11.33 ± 4.05 | 12.28 ± 3.57 | 1.962 | 0.051 |

| After | 16.98 ± 0.31 | 17.74 ± 3.22 | 2.620 | 0.010 | |

| Breast symptoms | Before | 18.00 ± 3.90 | 18.60 ± 4.29 | 1.151 | 0.251 |

| After | 19.52 ± 1.56 | 20.13 ± 1.58 | 3.045 | 0.003 | |

| Total score of quality of life | Before | 75.30 ± 14.70 | 74.78 ± 9.65 | 0.328 | 0.743 |

| After | 80.85 ± 14.22 | 82.46 ± 12.51 | 0.948 | 0.344 | |

| NRSs (score) | |||||

| Total | Before | 5.23 ± 1.85 | 4.81 ± 1.94 | 1.755 | 0.081 |

| After | 3.24 ± 1.48 | 2.82 ± 0.52 | 2.962 | 0.004 | |

| Grip strength difference (kg) | Before | 6.10 ± 1.70 | 6.21 ± 2.18 | 0.440 | 0.660 |

| After | 5.80 ± 0.57 | 5.56 ± 0.67 | 3.140 | 0.002 | |

| Shoulder flexion difference (°) | Before | 54.24 ± 5.19 | 53.68 ± 7.96 | 0.664 | 0.507 |

| After | 41.67 ± 7.35 | 39.50 ± 5.34 | 2.662 | 0.008 | |

| Shoulder abduction difference (°) | Before | 71 .00 ± 4.50 | 70.50 ± 4.34 | 0.888 | 0.376 |

| After | 56.67 ± 13.56 | 55.50 ± 6.24 | 0.871 | 0.385 |

After treatment, on the FACT-B scale, the MBCT group demonstrated markedly better physiological condition scores (13.85 ± 3.93) than the conventional group (12.55 ± 2.75), with a significant difference (t = 3.012, P = 0.003). Functional status also improved significantly in the MBCT group (17.74 ± 3.22) than in the conventional group (16.98 ± 0.31; t = 2.620, P = 0.010). Breast symptoms showed a notable improvement in the MBCT group (20.13 ± 1.58) vs the conventional group (19.52 ± 1.56; t = 3.045, P = 0.003). However, total scores for QoL and social family well-being did not differ significantly between groups. The NRSs indicated lower levels of discomfort in the MBCT group (2.82 ± 0.52) than in the conventional group (3.24 ± 1.48), with a significant difference (t = 2.962, P = 0.004). Regarding physical function, the MBCT group had a slight reduction in grip strength (5.56 ± 0.67 kg) than the conventional group (5.80 ± 0.57 kg; t = 3.140, P = 0.002), but shoulder flexion showed a significant improvement in the MBCT group (39.50° ± 5.34°) than in the conventional group (41.67° ± 7.35°, t = 2.662, P = 0.008). Shoulder abduction differences were not statistically significant. These results underscore the beneficial effects of MBCT in enhancing specific aspects of QoL and reducing physical discomfort in patients with breast cancer.

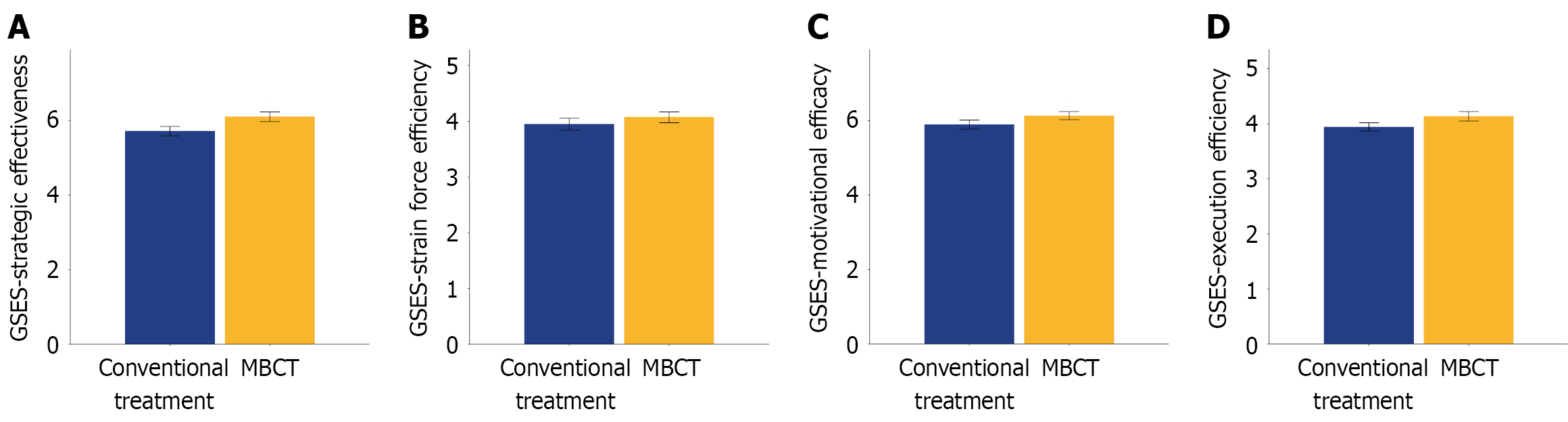

Prior to treatment, the GSES revealed that patients in the MBCT group showed no statistically significant difference in strategic effectiveness (5.99 ± 1.48) compared with those in the conventional group (5.92 ± 1.39, t = 0.396, P = 0.692; Figure 1). The differences in scores for strain force efficiency (MBCT: 4.07 ± 1.11, conventional: 3.95 ± 1.18), motivational efficacy (MBCT: 6.13 ± 1.22, conventional: 5.89 ± 1.37), and execution efficiency (MBCT: 4.13 ± 0.97, conventional: 3.94 ± 0.85) were not statistically significant.

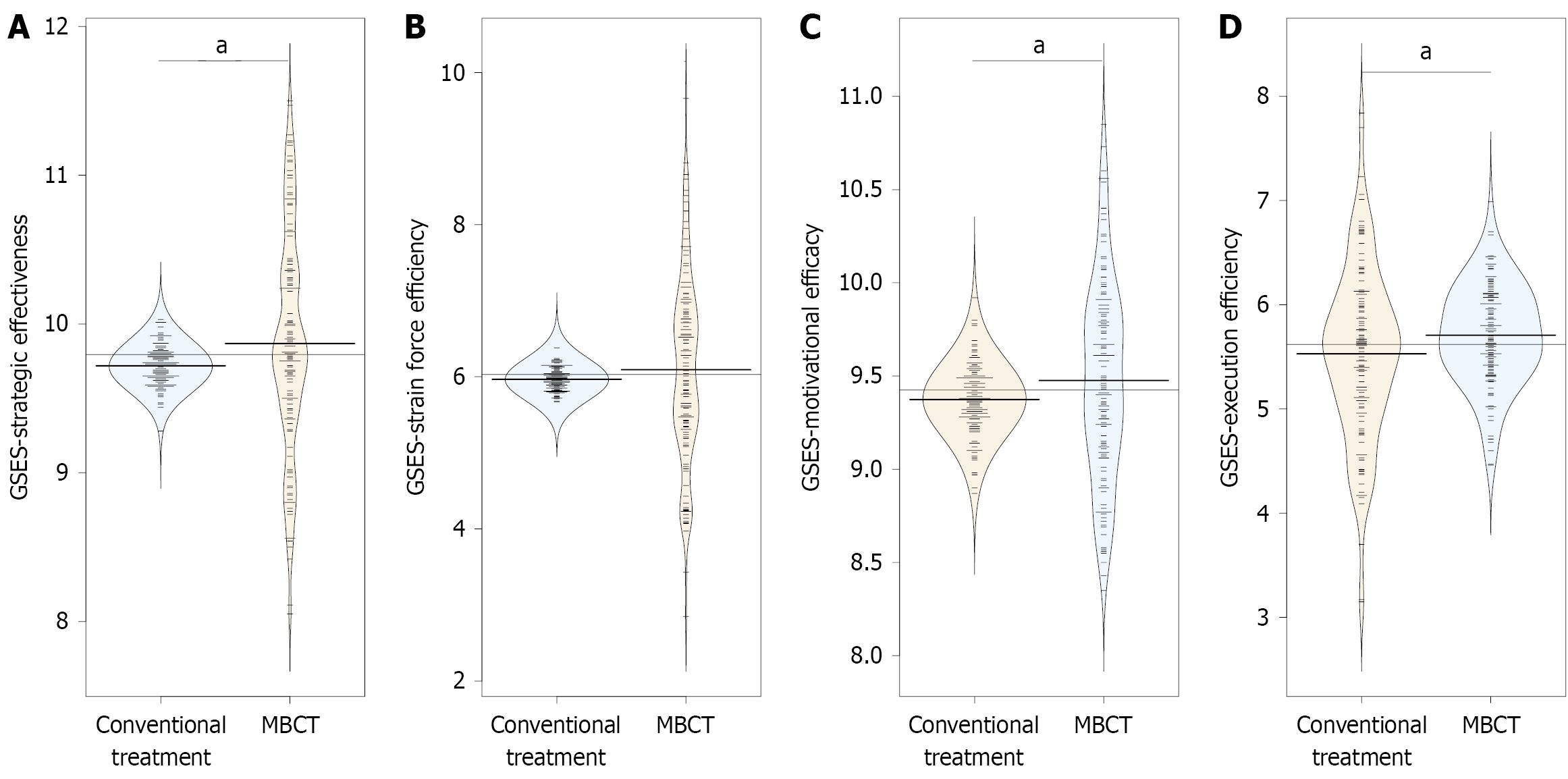

After treatment, on the GSES, the MBCT group scored significantly higher in strategic effectiveness (9.87 ± 0.75) than the conventional group (9.72 ± 0.13), with a statistically significant difference (t = 2.205, P = 0.029; Figure 2). Similarly, motivational efficacy was significantly higher in the MBCT group (9.48 ± 0.54) than in the conventional group (9.37 ± 0.18), with notable statistical significance (t = 2.002, P = 0.047). Additionally, execution efficiency was higher in the MBCT group (5.71 ± 0.48) than in the conventional group (5.53 ± 0.83; t = 2.064, P = 0.040). Conversely, scores for strain force efficiency did not show a statistically significant difference between the groups (t = 1.130, P = 0.260). These results indicated that MBCT effectively enhanced specific aspects of self-efficacy among patients with breast cancer, particularly in strategic effectiveness, motivational efficacy, and execution efficiency.

Breast cancer, a highly prevalent malignancy among women worldwide, imposes significant physical burdens and psychological distress, particularly among patients who are mothers. These individuals often deal with parenting-related anxieties, concerns regarding the effects of their illness and treatment on their children’s well-being, and general emotional disturbances such as anxiety and depression[4,5]. The present study explored the effects of MBCT compared with those of conventional treatments in managing parenting anxiety, alleviating negative emotional states, improving QoL, and enhancing self-efficacy among patients with breast cancer.

One of the most notable outcomes of this study was the reduction in parenting anxiety observed in the MBCT group (PCQ total: MBCT 50.54 ± 4.65 vs conventional 52.12 ± 5.53, P = 0.016). Patients with breast cancer often experience heightened anxiety related to their parenting roles due to concerns about their children's emotional and practical well-being. Our results suggested that MBCT, by fostering non-judgmental present-moment awareness, may help mitigate these specific anxieties; this result was consistent with prior studies showing that mindfulness-based approaches improve emotional regulation in cancer populations[27,28].

Moreover, MBCT demonstrated considerable effectiveness in reducing anxiety levels and stress-related responses such as intrusion, avoidance, and hyperarousal. The therapeutic mechanisms of MBCT involve the cultivation of a present-focused mindset, which allows patients to recognize and interrupt habitual patterns of negative thinking that often exacerbate anxiety and depressive symptoms. The reduction in anxiety symptoms may be primarily attributed to the program’s emphasis on mindfulness and its ability to restructure cognitive processes via enhanced attention control and emotional regulation. Training patients to focus on the “here and now” enables them to disengage from distressing anticipatory and ruminative thoughts, which are common among individuals coping with cancer[29,30].

The observed improvements in depressive symptoms and general psychological distress offer further evidence sup

In terms of QoL improvements, the MBCT group showed significant enhancements in several domains, including physiological condition, breast symptoms, and functional status. The holistic approach of MBCT, which integrates physical, cognitive, and emotional well-being, likely contributes to these improvements. For example, mindfulness activities, such as mindful walking and body scanning, integrate gentle physical engagement with cognitive exercises that promote a positive physiological feedback cycle, potentially reducing somatic symptom severity[34,35].

The role of mindfulness in improving perceived functional status and physiology among patients with cancer must not be neglected. Regular practice may have contributed to this outcome by decreasing physiological stress responses, alleviating the physical symptoms associated with breast cancer and its treatment. Encouraging physical awareness and acceptance may reduce symptom-related distress by shifting the individuals’ focus from pain and discomfort to func

The significant enhancement in self-efficacy observed post-MBCT, particularly in strategic effectiveness (GSES: MBCT 9.87 ± 0.75 vs conventional 9.72 ± 0.13, P = 0.029), suggests that mindfulness training may strengthen patients’ belief in their ability to manage cancer-related challenges. This is critical for patients with breast cancer, who often struggle with perceived loss of control over their health and family roles. By promoting self-regulation and cognitive flexibility, MBCT may empower patients to adopt proactive coping strategies[39,40].

Interestingly, MBCT led to statistically significant improvements in the measured outcomes, but total scores of QoL and some emotional well-being metrics did not show drastic changes. These outcomes might reflect the complex nature of QoL indices in breast cancer survivors, which include diverse aspects that may be differentially affected by cognitive-behavioral interventions. The holistic nature of MBCT suggests it may require additional time or supplementary interventions to show substantial changes across all areas of life.

Our study clarifies the underlying mechanisms that contribute to the observed benefits of MBCT and highlights potential areas for improvement. The intricate structure of MBCT enables it to effectively target specific life domains; yet, the implementation in clinical practice could benefit from individualized adjustments to further maximize its effects on overall QoL. Further investigations should explore the long-term effects of such interventions, focusing on the durability of outcomes in chronic disease management strategies.

This study offers valuable insights into the benefits of MBCT for patients with breast cancer, but several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the sample size was relatively small, potentially limiting the generalizability of the findings to a broad population of patients with breast cancer. Second, the study relied on self-reported measures, which may introduce bias or inaccuracies due to subjective interpretations and recall issues. Third, the follow-up period was limited, restricting the ability to assess the long-term sustainability of the intervention's effects. Future studies should consider employing large, diverse cohorts and extended follow-up durations to corroborate and expand upon these findings. Lastly, the absence of a control group receiving an alternative psychological intervention leaves room for further comparison and deep insights into the unique contributions of MBCT compared with other therapeutic options.

This study contributes to the existing literature on psychosocial interventions in cancer care, offering valuable insights into MBCT as a multifaceted approach for managing complex psychological and quality-of-life challenges in patients with breast cancer. The integration of MBCT alongside traditional therapeutic practices represents a promising pathway toward comprehensive and personalized patient care, addressing not the physical symptoms and intricate psychological challenges faced by patients as they navigate illness, treatment, and familial roles. Future research endeavors should assess long-term sustainability, aiming to understand how continued mindfulness practice induces lasting change while refining these interventions to improve accessibility and adherence.

| 1. | Valente S, Roesch E. Breast cancer survivorship. J Surg Oncol. 2024;130:8-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Xiong X, Zheng LW, Ding Y, Chen YF, Cai YW, Wang LP, Huang L, Liu CC, Shao ZM, Yu KD. Breast cancer: pathogenesis and treatments. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2025;10:49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 309] [Article Influence: 309.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Qi YJ, Su GH, You C, Zhang X, Xiao Y, Jiang YZ, Shao ZM. Radiomics in breast cancer: Current advances and future directions. Cell Rep Med. 2024;5:101719. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ren Y, Maselko J, Tan X, Olshan AF, Stover AM, Bennett AV, Reeder-Hayes KE, Edwards JK, Reeve BB, Troester MA, Emerson MA. Emotional and functional well-being in long-term breast cancer survivorship. Cancer Causes Control. 2024;35:1191-1200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ruiz-González P, Guil R. Experiencing anxiety in breast cancer survival: Does perceived emotional intelligence matter? Psychooncology. 2023;32:972-979. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Xu Z, Liu C, Fan W, Li S, Li Y. Effect of music therapy on anxiety and depression in breast cancer patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2024;14:16532. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Sun M, Liu C, Lu Y, Zhu F, Li H, Lu Q. Effects of Physical Activity on Quality of Life, Anxiety and Depression in Breast Cancer Survivors: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Asian Nurs Res (Korean Soc Nurs Sci). 2023;17:276-285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Antoni MH, Moreno PI, Penedo FJ. Stress Management Interventions to Facilitate Psychological and Physiological Adaptation and Optimal Health Outcomes in Cancer Patients and Survivors. Annu Rev Psychol. 2023;74:423-455. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 22.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Elkefi S, Trapani D, Ryan S. The role of digital health in supporting cancer patients' mental health and psychological well-being for a better quality of life: A systematic literature review. Int J Med Inform. 2023;176:105065. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Zeng Q, Li C, Yu T, Zhang H. Comparative Effects of Exercise Interventions and Mindfulness-Based Interventions for Cognitive Impairment and Quality of Life in Breast Cancer Survivors During or After Cancer Treatment: A Systematic Review and Bayesian Network Meta-analysis. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2024;103:777-788. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Oner Cengiz H, Bayir B, Sayar S, Demirtas M. Effect of mindfulness-based therapy on spiritual well-being in breast cancer patients: a randomized controlled study. Support Care Cancer. 2023;31:438. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Chang YC, Tseng TA, Lin GM, Hu WY, Wang CK, Chang YM. Immediate impact of Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT) among women with breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Womens Health. 2023;23:331. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kuswanto CN, Stafford L, Schofield P, Sharp J. Self-compassion and parenting efficacy among mothers who are breast cancer survivors: Implications for psychological distress. J Health Psychol. 2024;29:425-437. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Fisher HM, Stalls J, Winger JG, Miller SN, Plumb Vilardaga JC, Majestic C, Kelleher SA, Somers TJ. Role of self-efficacy for pain management and pain catastrophizing in the relationship between pain severity and depressive symptoms in women with breast cancer and pain. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2023;41:87-103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Abdo J, Ortman H, Rodriguez N, Tillman R, Riordan EO, Seydel A. Quality of Life Issues Following Breast Cancer Treatment. Surg Clin North Am. 2023;103:155-167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Cardoso F, Kyriakides S, Ohno S, Penault-Llorca F, Poortmans P, Rubio IT, Zackrisson S, Senkus E; ESMO Guidelines Committee. Electronic address: clinicalguidelines@esmo.org. Early breast cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up†. Ann Oncol. 2019;30:1194-1220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 635] [Cited by in RCA: 1462] [Article Influence: 243.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Park EM, Wang M, Bowers SM, Muriel AC, Rauch PK, Edwards T, Yi SM, Daniel B, Hanson LC, Song MK. Adaptation and Psychometric Evaluation of the Parenting Concerns Questionnaire-Advanced Disease. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2022;39:918-925. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Li XY, Mao KN, Mi XY, Gao LL, Yang X, Tao HF, Zhang YW, Chen J, Wang X, Shen LJ, Yuan JL, Miao M, Zhou H. [Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of parenting sense of competence scale in mothers of preschool children]. Beijing Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2021;53:479-484. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Kwon M, Kim DJ, Cho H, Yang S. The smartphone addiction scale: development and validation of a short version for adolescents. PLoS One. 2013;8:e83558. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 602] [Cited by in RCA: 843] [Article Influence: 64.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Bastiani L, Siciliano V, Curzio O, Luppi C, Gori M, Grassi M, Molinaro S. Optimal scaling of the CAST and of SDS Scale in a national sample of adolescents. Addict Behav. 2013;38:2060-2067. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Mykletun A, Stordal E, Dahl AA. Hospital Anxiety and Depression (HAD) scale: factor structure, item analyses and internal consistency in a large population. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;179:540-544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 583] [Cited by in RCA: 644] [Article Influence: 25.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Park YS, Park KH, Lee J. Validation of the Korean Version of Impact of Event Scale-Revised (IES-R) in Korean Nurses during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:11311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Jensen CG, Krogh SC, Westphael G, Hjordt LV. Mindfulness is positively related to socioeconomic job status and income and independently predicts mental distress in a long-term perspective: Danish validation studies of the Five-Factor Mindfulness Questionnaire. Psychol Assess. 2019;31:e1-e20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Pandey M, Thomas BC, Ramdas K, Eremenco S, Nair MK. Quality of life in breast cancer patients: validation of a FACT-B Malayalam version. Qual Life Res. 2002;11:87-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Luo Q, Liu C, Zhou Y, Zou X, Song L, Wang Z, Feng X, Tan W, Chen J, Smith GD, Chiesi F. Chinese cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the Well-being Numerical Rating Scales. Front Psychiatry. 2023;14:1208001. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Malinakova K, Furstova J, Kalman M, Trnka R. A Psychometric Evaluation of the Guilt and Shame Experience Scale (GSES) on a Representative Adolescent Sample: A Low Differentiation between Guilt and Shame. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:8901. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Reangsing C, Punsuwun S, Keller K. Effects of Mindfulness-Based Interventions on Depression in Patients With Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Integr Cancer Ther. 2023;22:15347354231220617. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Børøsund E, Meland A, Eriksen HR, Rygg CM, Ursin G, Solberg Nes L. Digital Cognitive Behavioral- and Mindfulness-Based Stress-Management Interventions for Survivors of Breast Cancer: Development Study. JMIR Form Res. 2023;7:e48719. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Park JY, Lengacher CA, Rodriguez CS, Meng H, Kip KE, Morgan S, Joshi A, Hueluer G, Wang JR, Tinsley S, Cox C, Kiluk J, Donovan KA, Moscoso M, Bornstein E, Lucas JM, Fonseca T, Krothapalli M, Padgett LS, Nidamanur S, Hornback E, Patel D, Chamkeri R, Reich RR. The Moderating Role of Genetics on the Effectiveness of the Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction for Breast Cancer (MBSR(BC)) Program on Cognitive Impairment. Biol Res Nurs. 2025;27:216-228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Dong X, Liu Y, Fang K, Xue Z, Hao X, Wang Z. The use of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) for breast cancer patients-meta-analysis. BMC Psychol. 2024;12:619. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Xu F, Zhang J, Xie S, Li Q. Effects of Mindfulness-Based Cancer Recovery training on anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and cancer-related fatigue in breast neoplasm patients undergoing chemotherapy. Medicine (Baltimore). 2024;103:e38460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Wang H, Yang Y, Zhang X, Shu Z, Tong F, Zhang Q, Yi J. Research on Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction in Breast Cancer Patients Undergoing Chemotherapy: An Observational Pilot Study. Altern Ther Health Med. 2023;29:228-232. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Melati KBDS, Bellynda M, Yarso KY, Kusuma W, Sudiyanto A. The Effectiveness of Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy to Improve Anxiety Symptoms and Quality of Life in Breast Cancer Patients. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2024;25:3081-3086. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Zhu P, Liu X, Shang X, Chen Y, Chen C, Wu Q. Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction for Quality of Life, Psychological Distress, and Cognitive Emotion Regulation Strategies in Patients With Breast Cancer Under Early Chemotherapy-a Randomized Controlled Trial. Holist Nurs Pract. 2023;37:131-142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Wang X, Dai Z, Zhu X, Li Y, Ma L, Cui X, Zhan T. Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on quality of life of breast cancer patient: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2024;19:e0306643. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Yu J, Han M, Miao F, Hua D. Using mindfulness-based stress reduction to relieve loneliness, anxiety, and depression in cancer patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2023;102:e34917. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Lengacher CA, Hueluer G, Wang JR, Reich RR, Meng H, Park JY, Kip KE, Morgan S, Joshi A, Tinsley S, Krothapalli M, Nidamanur S, Cox C, Kiluk J, Lucas JM, Fonseca T, Moscoso MS, Bornstein E, Donovan KA, Padgett LS, Chamkeri R, Patel D, Hornback E, Rodríguez CCS. A Randomized Clinical Trial of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction Program Among Breast Cancer Survivors Post-Treatment: Evaluating Mediators of Cognitive Improvement. J Integr Complement Med. 2025;31:367-377. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Ahmed Abd-El Naby Abd Allah R, Mohammed Mourad G, Osman Abd El-Fatah W. Effectiveness of Mindfulness-Based Interventions for Reducing Anxiety Among Women With Breast Cancer. Plast Aesthet Nurs (Phila). 2025;45:49-60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Pehlivan M, Eyi S. The Impact of Mindfulness-Based Meditation and Yoga on Stress, Body Image, Self-esteem, and Sexual Adjustment in Breast Cancer Patients Undergoing Modified Radical Mastectomy: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Cancer Nurs. 2025;48:190-199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Bahcivan O, Gutierrez-Maldonado J, Estapé T. A single-session Mindfulness-Based Swinging Technique vs. cognitive disputation intervention among women with breast cancer: A pilot randomised controlled study examining the efficacy at 8-week follow-up. Front Psychol. 2022;13:1007065. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/