Published online Dec 19, 2025. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v15.i12.109437

Revised: July 9, 2025

Accepted: October 22, 2025

Published online: December 19, 2025

Processing time: 175 Days and 1.7 Hours

Depression is a highly prevalent and clinically significant psychiatric comorbidity in patients with heart failure (HF), exerting multidimensional effects that extend beyond emotional symptoms to influence physiological outcomes and disease progression. Emerging evidence in psychocardiology highlights the bidirectional interplay between mood disorders and cardiovascular dysfunction through neuroendocrine, autonomic, and behavioral pathways. This study aims to explore the real-world effect of depression severity - measured by the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) - on left ventricular systolic function and one-year car

To investigate the impact of depression severity on medication adherence, ven

A total of 160 patients hospitalized for HF between January 2020 and December 2023 were included in this real-world retrospective cohort study. Depression severity was assessed by using the PHQ-9, with scores ≥ 10 indicating moderate-to-severe depression. Cardiac function was evaluated through transthoracic echocardiography to determine left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF). Medication adherence was assessed at three and six months postdischarge by employing the four-item Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (MMAS-4) and categorized as high (score = 0), moderate (1-2), or low (3-4). Data on antidepressant or anxiolytic prescriptions and psychological interventions during hospitalization were collected. Patients were followed up for one year to capture cardiovascular-related readmissions. Kaplan-Meier analysis was employed to estimate event-free survival, and Cox regression identified independent predictors of readmission.

Patients with moderate-to-severe depression (PHQ-9 ≥ 10) presented with significantly lower LVEF at baseline, higher N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide levels, and more severe HF symptoms than other patients. They also demonstrated poorer medication adherence postdischarge, with a higher proportion classified as low ad

In patients with HF, depression severity independently predicts impaired ventricular function, low medication adherence, and increased one-year cardiovascular readmission. These findings highlight the psychocardiological relevance of depression screening and behavioral intervention in optimizing adherence and clinical outcomes in routine HF care.

Core Tip: This real-world retrospective cohort study investigated the psychocardiological impact of depression on heart failure outcomes. Depression severity, measured by the Patient Health Questionnaire-9, was associated with poorer medication adherence, reduced left ventricular ejection fraction, and higher 1-year readmission risk. These findings underscore the need to incorporate psychosocial screening and interventions into routine heart failure management.

- Citation: Mao FG, Tang YL, Wang XY, Jin X, Fan JY. Psychocardiological impact of depression on medication adherence, ventricular function, and readmission in heart failure: A retrospective cohort study. World J Psychiatry 2025; 15(12): 109437

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v15/i12/109437.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v15.i12.109437

Heart failure (HF) remains a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, affecting approximately 64 million people and accounting for substantial healthcare costs due to frequent hospitalizations and poor long-term survival[1]. Despite advances in pharmacologic and device-based therapies, 30%-50% of HF patients require rehospitalization within one year of discharge, highlighting the need for improved risk stratification and management strategies[2,3].

Depression is increasingly recognized as a significant yet underdiagnosed comorbidity in HF, with a prevalence ranging from 20% to 40%, exceeding that of the general population[4]. Evidence suggests that depression is associated with increased hospitalizations, worse medication adherence, reduced quality of life, and higher mortality in HF patients[5]. The pathophysiological mechanisms underlying this relationship remain incompletely understood but are thought to involve autonomic dysfunction, systemic inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, and dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, all of which contribute to worsening cardiac function and adverse cardiovascular outcomes[5-7].

Although previous studies have established an association between depression and adverse HF outcomes, several critical knowledge gaps remain[8]. The direct impact of depression severity on cardiac function, particularly left ven

To address these gaps, this study investigates the association between depression severity. We used the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) to assess depression severity. Cardiac dysfunction [LVEF, New York Heart Association (NYHA) classification], and one-year cardiovascular event-related readmission in HF patients[15]. By integrating standardized depression assessment with objective cardiac function measures and long-term clinical outcomes, this study aims to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the prognostic significance of depression in HF, which may help refine risk stratification and guide future HF management strategies.

This was a retrospective cohort study conducted at a tertiary academic hospital specializing in cardiovascular care. The primary objective was to examine the association between depression severity and cardiac dysfunction in patients hospitalized for HF and to evaluate the prognostic significance of depressive symptoms on one-year cardiovascular event-related readmission. The study adhered to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and followed the STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology guidelines for reporting.

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of The First People’s Hospital of Yunnan Province (Approval No. 2025-YNFPH-006), which granted a waiver of informed consent due to the use of ano

We retrospectively reviewed electronic medical records of patients hospitalized for HF between January 2020 and December 2023. Patients were included if they met European Society of Cardiology/American Heart Association HF diagnostic criteria, confirmed by clinical evaluation and echocardiographic evidence, and had completed a PHQ-9 de

Exclusion criteria included end-stage renal disease, active malignancy, severe hepatic dysfunction, recent major cardiac surgery (e.g., coronary artery bypass grafting or valve replacement within the past three months), pre-existing psychiatric disorders other than depression, long-term psychiatric medication use, incomplete medical records, or loss to follow-up.

Demographic, clinical, and medication data were extracted from electronic medical records. Baseline characteristics included age, sex, body mass index, NYHA classification, prior cardiovascular history (coronary artery bypass grafting, myocardial infarction), and HF etiology (ischemic vs non-ischemic). Depression severity was assessed using PHQ-9, with no/mild depression defined as PHQ-9 ≤ 9 and moderate/severe depression as PHQ-9 ≥ 10. Cardiac function was evaluated using LVEF, with LVEF ≤ 20% considered severe systolic dysfunction. Discharge medications included β-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, diuretics, nitrates, antidepressants, and anxiolytics.

The primary outcome was cardiovascular event-related readmission within one year, including worsening HF, acute coronary syndrome (myocardial infarction or unstable angina), arrhythmia-related hospitalization, sudden cardiac death, and other cardiovascular complications. The secondary outcomes included event-free survival (EFS), time to first car

Medication adherence was assessed using the 4-item Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (MMAS-4) at both 3 months and 6 months post-discharge. The scale consists of four yes/no questions addressing forgetfulness, discontinuation, and regimen complexity. Each “yes” response scores 1 point, yielding a total score range of 0 to 4, with higher scores in

All patients were followed prospectively for 12 months from the date of hospital discharge. Follow-up was conducted through a review of electronic medical records and scheduled outpatient visits at 3 months, 6 months, and 12 months. Additional information was obtained via structured telephone interviews when necessary to ensure completeness of outcome data. The primary outcome was cardiovascular event-related readmission, defined as hospitalization due to worsening HF, acute coronary syndrome, arrhythmia, sudden cardiac death, or other major cardiovascular complications. Each readmission event was independently adjudicated and classified by two board-certified cardiologists blinded to patients’ depression status, with discrepancies resolved by consensus.

Secondary outcomes included time to first cardiovascular event and event-free survival. Patients who died during follow-up without prior readmission were considered to have experienced the primary endpoint. Those lost to follow-up or with incomplete outcome data were excluded from the final analysis.

A power analysis was conducted to ensure an adequate sample size for detecting significant differences in cardiovascular readmission rates between depression severity groups. The final cohort included 160 patients, providing sufficient power for statistical analysis. Missing data were assessed, and appropriate statistical methods, including multiple imputation, were applied where necessary.

Despite the inherent limitations of a retrospective cohort study, including selection bias, missing data, and unmeasured confounders, the use of strict inclusion criteria, standardized data collection, and robust statistical methodologies enhance the validity and reliability of the findings.

All statistical analyses were performed using R software (version 4.2.1, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± SD or median with interquartile range (IQR), and categorical variables as frequencies and percentages. Between-group comparisons were conducted using the Student’s t-test or Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables, and the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables, as app

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was employed to estimate EFS, with differences assessed using the log-rank test. Univariable Cox proportional hazards models were used to identify potential predictors of one-year cardiovascular event-related readmission. Variables with a P value < 0.10 in univariable analysis were entered into the multivariable Cox regression model using a forward stepwise approach. Hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were reported.

The proportional hazards assumption was verified using Schoenfeld residuals. Missing data were handled using multiple imputations by chained equations under the assumption of missing at random, generating five imputed datasets with pooled estimates. Statistical significance was defined as a two-sided P-value < 0.05.

A total of 160 patients with HF were included, with a mean age of 75 ± 9 years. Patients with moderate or severe depression were significantly older than those with no or mild depression (78 ± 9 years vs 73 ± 5 years, P = 0.045), and less likely to be male (23% vs 40%, P = 0.021). Heart rate was higher in the depressed group (86 ± 15 bpm vs 80 ± 13 bpm, P = 0.041), whereas body mass index and blood pressure values were comparable between groups. Patients with moderate/severe depression showed more advanced HF features, including a higher prevalence of NYHA class IV (12% vs 8%, P = 0.039), lower mean LVEF (26 ± 6% vs 34 ± 7%, P = 0.031), and a greater proportion with LVEF ≤ 20% (P = 0.042). Ischemic etiology was significantly less common in the depressed group (15% vs 45%, P = 0.018). Comorbid conditions such as coronary artery disease (14% vs 38%, P = 0.026), prior myocardial infarction (11% vs 27%, P = 0.048), hypertension (17% vs 44%, P = 0.035), and hyperlipidemia (10% vs 26%, P = 0.043) were less prevalent in the depressed cohort. No differences were observed in diabetes prevalence. Patients with moderate/severe depression were more likely to have lower educational attainment (17% vs 28%, P = 0.038) and to be divorced or separated (12% vs 10%, P = 0.042). While N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) concentrations were significantly higher in the depressed group (median 3900 pg/mL vs 2700 pg/mL, P = 0.038), there were no group differences in C-reactive protein, hemoglobin, serum albumin, creatinine, or hospital length of stay. The use of psychotherapy was more frequent in the moderate/severe depression group (22% vs 4%, P = 0.011). At discharge, patients with moderate/severe depression were significantly less likely to receive β-blockers (22% vs 43%, P = 0.027) or ACE inhibitors (22% vs 48%, P = 0.023), but more likely to be prescribed antidepressants (12% vs 8%, P = 0.036) and anxiolytics (13% vs 5%, P = 0.046; Table 1).

| Variables | Total (n = 160) | No/mild depression (n = 100) | Moderate/severe depression (n = 60) | Test statistic | P value |

| Age, years | 75 ± 9 | 73 ± 5 | 78 ± 9 | t = 2.04 | 0.045 |

| Male | 63.1 (101/160) | 40.0 (40/100) | 23.3 (14/60) | χ2 = 5.3 | 0.021 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 25 ± 3 | 25 ± 3 | 24 ± 3 | t = 0.99 | 0.322 |

| Heart rate, bpm | 82 ± 14 | 80 ± 13 | 86 ± 15 | t = 2.06 | 0.041 |

| Systolic bp, mmHg | 118 ± 16 | 120 ± 15 | 115 ± 17 | t = 1.84 | 0.067 |

| Diastolic bp, mmHg | 71 ± 10 | 72 ± 9 | 69 ± 11 | t = 1.56 | 0.119 |

| NYHA class II | 23.8 (38/160) | 31.0 (31/100) | 11.7 (7/60) | χ2 = 4.6 | 0.032 |

| NYHA class III | 19.4 (31/160) | 22.0 (22/100) | 15.0 (9/60) | χ2 = 1.5 | 0.217 |

| NYHA class IV | 9.4 (15/160) | 8.0 (8/100) | 11.7 (7/60) | χ2 = 4.3 | 0.039 |

| Coronary artery disease | 51.9 (83/160) | 38.0 (38/100) | 13.3 (8/60) | χ2 = 5.0 | 0.026 |

| Prior myocardial infarction | 38.1 (61/160) | 27.0 (27/100) | 11.7 (7/60) | χ2 = 3.9 | 0.048 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 40.0 (64/160) | 25.0 (25/100) | 15.0 (9/60) | χ2 = 3.2 | 0.072 |

| Hypertension | 61.3 (98/160) | 44.0 (44/100) | 16.7 (10/60) | χ2 = 4.4 | 0.035 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 36.3 (58/160) | 26.0 (26/100) | 10.0 (6/60) | χ2 = 4.1 | 0.043 |

| Low education level | 45.0 (72/160) | 28.0 (28/100) | 16.7 (10/60) | χ2 = 3.8 | 0.038 |

| Divorced/separated | 21.9 (35/160) | 10.0 (10/100) | 11.7 (7/60) | χ2 = 4.2 | 0.042 |

| Etiology of CHF: Ischemic | 60.0 (96/160) | 45.0 (45/100) | 15.0 (9/60) | χ2 = 5.7 | 0.018 |

Patients with moderate to severe depression exhibited distinct pharmacological and behavioral treatment patterns compared to those with no or mild depressive symptoms. Prescription rates of β-blockers (53.3% vs 68.0%, χ2 = 3.5, P = 0.061), ACE inhibitors/angiotensin II receptor blocker (56.7% vs 70.0%, χ2 = 3.7, P = 0.054), and diuretics (61.7% vs 75.0%, χ2 = 3.0, P = 0.084) were numerically lower among patients with higher depressive burden, although differences approached but did not reach conventional statistical significance. Conversely, mental health interventions were more commonly utilized in the depressed subgroup, with higher proportions receiving antidepressants (16.7% vs 9.0%, χ2 = 2.6, P = 0.107), anxiolytics (13.3% vs 7.0%, χ2 = 2.9, P = 0.091), and psychotherapy (18.3% vs 6.0%, χ2 = 4.1, P = 0.043), the latter reaching statistical significance.

Adherence to HF medications, as assessed by the MMAS-4 scale, differed meaningfully across groups. Patients with moderate to severe depression were significantly more likely to report low adherence (35.0% vs 22.0%, χ2 = 3.9, P = 0.048) and less likely to report high adherence (25.0% vs 40.0%, χ2 = 4.6, P = 0.031). Moderate adherence rates were similar between groups (40.0% vs 38.0%, χ2 = 0.1, P = 0.794; Table 2).

| Variables | No/mild depression (n = 100) | Moderate/severe depression (n = 60) | Test statistic | P value |

| β-blocker use | 68.0 (68/100) | 53.3 (32/60) | χ2 = 3.5 | 0.061 |

| ACE inhibitor/ARB use | 70.0 (70/100) | 56.7 (34/60) | χ2 = 3.7 | 0.054 |

| Diuretic use | 75.0 (75/100) | 61.7 (37/60) | χ2 = 3.0 | 0.084 |

| Antidepressant use | 9.0 (9/100) | 16.7 (10/60) | χ2 = 2.6 | 0.107 |

| Anxiolytic use | 7.0 (7/100) | 13.3 (8/60) | χ2 = 2.9 | 0.091 |

| Psychotherapy | 6.0 (6/100) | 18.3 (11/60) | χ2 = 4.1 | 0.043 |

| High adherence (MMAS-4 = 0) | 40.0 (40/100) | 25.0 (15/60) | χ2 = 4.6 | 0.031 |

| Moderate adherence (MMAS-4 = 1-2) | 38.0 (38/100) | 40.0 (24/60) | χ2 = 0.1 | 0.794 |

| Low adherence (MMAS-4 = 3-4) | 22.0 (22/100) | 35.0 (21/60) | χ2 = 3.9 | 0.048 |

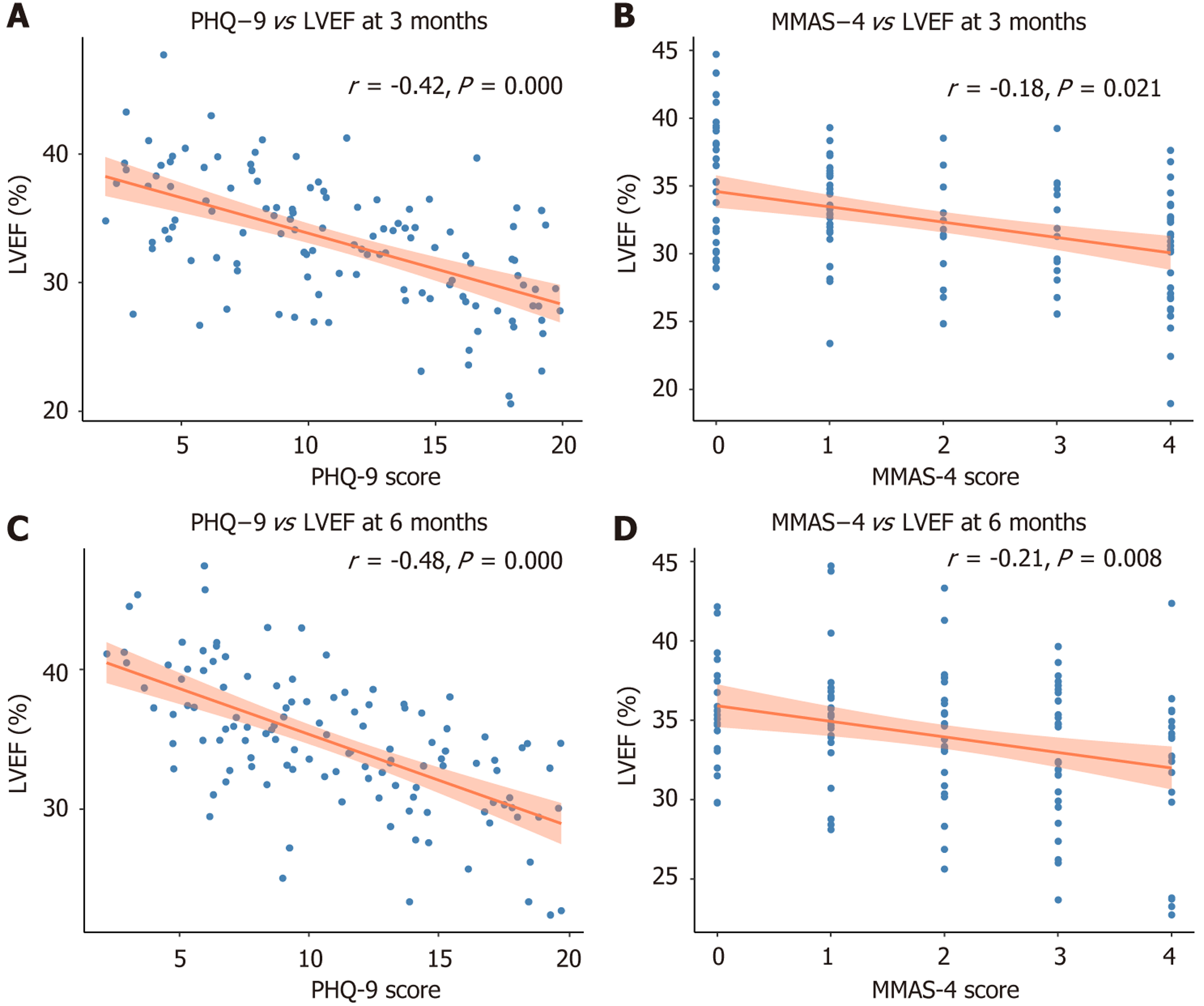

At 3 months and 6 months post-discharge, both depressive symptom severity and medication adherence were significantly associated with left ventricular systolic function. Baseline PHQ-9 scores were modestly but consistently inversely correlated with LVEF at 3 months (r = -0.26, P = 0.008) and 6 months (r = -0.24, P = 0.009), indicating that patients with higher depressive burden exhibited delayed or impaired cardiac recovery. Similarly, higher MMAS-4 scores, reflecting poorer adherence, were independently linked to lower LVEF at both timepoints (r = -0.23 at 3 months, P = 0.012; r = -0.22 at 6 months, P = 0.014).

To explore potential confounding, a sensitivity analysis restricted to patients with moderate-to-high adherence (MMAS-4 < 3) was performed. Within this subgroup, depression severity remained inversely correlated with LVEF at 6 months (r = -0.22, P = 0.034), suggesting a possible behavioral-independent effect of depression on ventricular function (Supplementary Table 1). Among patients with PHQ-9 ≥ 10, those prescribed antidepressants at discharge (n = 24) showed modestly improved adherence at 3 months (mean MMAS-4 score 1.9 vs 2.5; mean difference of -0.6, P = 0.041) compared with untreated counterparts. However, no significant difference in LVEF was observed at 6 months between treated and untreated groups (29.3% vs 28.7%, P = 0.372), implying that while antidepressant use may enhance short-term adherence, its direct impact on cardiac function recovery is limited (Supplementary Table 2).

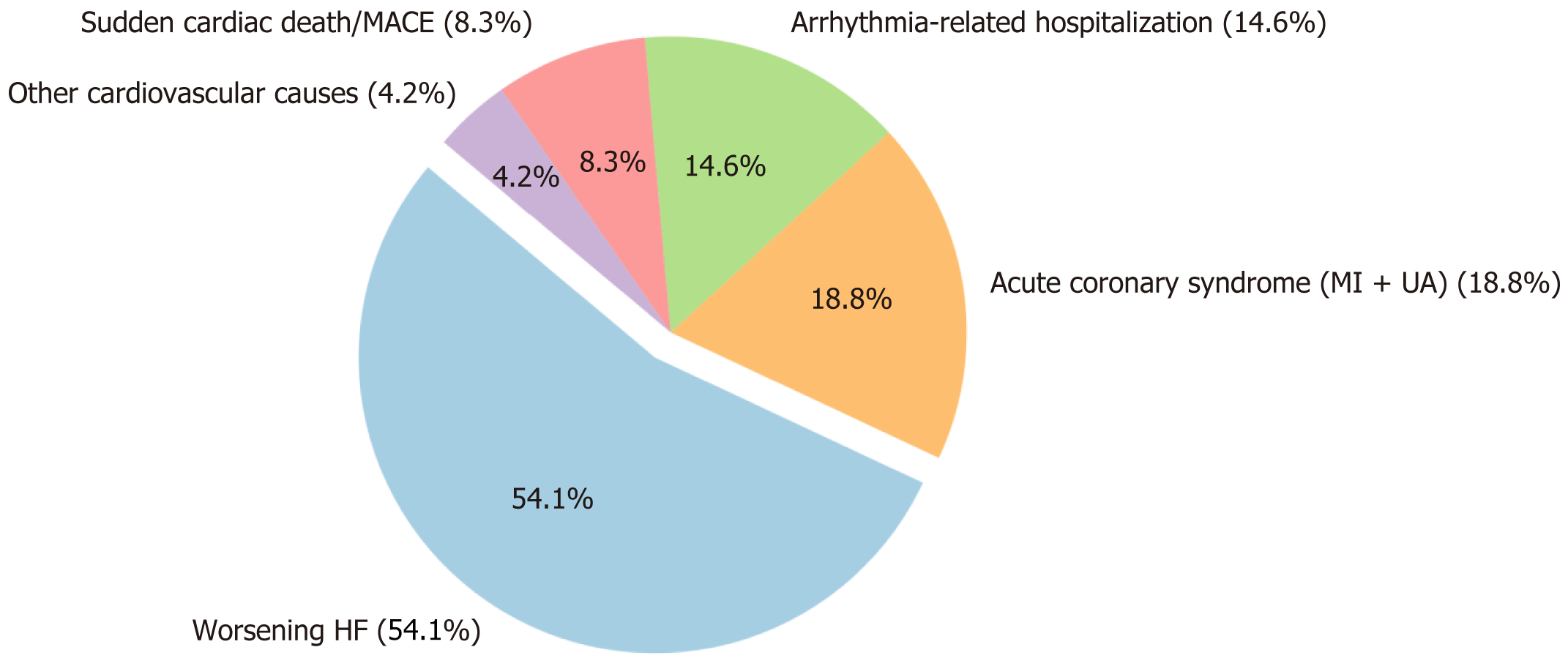

During the 12-month follow-up period, 48 out of 160 patients (30.0%) experienced at least one cardiovascular event-related readmission (Table 3). The median time to the first cardiovascular event was 124 days (IQR: 93.5-150.5 days), with more than half of the events occurring within the first four months after discharge (Figure 1), highlighting an early vulnerable period for cardiovascular deterioration.

| Variables | Total (n = 160) | No/mild depression (n = 100) | Moderate/severe depression (n = 60) | Test statistic | P value |

| LVEF | 30 ± 8 | 34 ± 7 | 26 ± 6 | t = 2.2 | 0.031 |

| LVEF ≤ 20% | 18.1 (29/160) | 10.0 (10/100) | 31.7 (19/60) | χ2 = 4.1 | 0.042 |

| PHQ-9 score | 7 ± 3 | 4 ± 2 | 12 ± 4 | t = 6.2 | < 0.001 |

| NT-proBNP, pg/mL, median (interquartile range) | 3000 (1800-4700) | 2700 (1600-4100) | 3900 (2100-5400) | Z = 2.1 | 0.038 |

| CRP, mg/L | 8.5 ± 3.2 | 7.9 ± 3.1 | 9.6 ± 3.3 | t = 1.7 | 0.084 |

| Hemoglobing, dL | 11.2 ± 1.5 | 11.4 ± 1.3 | 10.7 ± 1.6 | t = 1.8 | 0.076 |

| Serum albumin, g/L | 38 ± 4 | 39 ± 3 | 36 ± 4 | t = 1.9 | 0.058 |

| Serum creatinine, μmol/L | 109 ± 36 | 102 ± 34 | 121 ± 38 | t = 1.9 | 0.062 |

| Length of hospital stay, days, median (interquartile range) | 9 (6-13) | 8 (5-11) | 11 (7-15) | Z = 1.8 | 0.071 |

| Use of psychotherapy | 10.0 (16/160) | 4.0 (4/100) | 20.0 (12/60) | χ2 = 6.4 | 0.011 |

| Worsening CHF | 45.0 (72/160) | 28.0 (28/100) | 73.3 (44/60) | χ2 = 4.8 | 0.029 |

| Myocardial infarction | 20.0 (32/160) | 14.0 (14/100) | 30.0 (18/60) | χ2 = 2.9 | 0.086 |

| Unstable angina | 15.0 (24/160) | 9.0 (9/100) | 25.0 (15/60) | χ2 = 1.1 | 0.294 |

| Arrhythmia | 11.9 (19/160) | 7.0 (7/100) | 20.0 (12/60) | χ2 = 0.8 | 0.371 |

| Other admission | 8.1 (13/160) | 5.0 (5/100) | 13.3 (8/60) | χ2 = 0.5 | 0.478 |

| β-blockers at discharge | 65.0 (104/160) | 43.0 (43/100) | 21.7 (13/60) | χ2 = 5.0 | 0.027 |

| Calcium blockers | 30.0 (48/160) | 20.0 (20/100) | 10.0 (6/60) | χ2 = 3.4 | 0.068 |

| ACE inhibitors | 70.0 (112/160) | 48.0 (48/100) | 21.7 (13/60) | χ2 = 5.2 | 0.023 |

| Diuretics | 75.0 (120/160) | 50.0 (50/100) | 25.0 (15/60) | χ2 = 5.6 | 0.019 |

| Nitrates | 50.0 (80/160) | 35.0 (35/100) | 15.0 (9/60) | χ2 = 4.2 | 0.041 |

| Antidepressants | 20.0 (32/160) | 8.0 (8/100) | 11.7 (7/60) | χ2 = 4.4 | 0.036 |

| Anxiolytics | 18.1 (29/160) | 5.0 (5/100) | 13.3 (8/60) | χ2 = 3.9 | 0.046 |

The distribution and timing of cardiovascular event types are summarized in Figure 2 and Table 4. Worsening heart failure was the most frequent cause of readmission, observed in 26 patients (54.1%), followed by acute coronary syndrome - including myocardial infarction and unstable angina - in 9 cases (18.8%) and arrhythmia-related hospitalization in 7 patients (14.6%). Additionally, 4 patients (8.3%) were readmitted due to sudden cardiac death or other major adverse cardiovascular events, while 2 patients (4.2%) were readmitted for other cardiovascular conditions such as hyp

| Cardiovascular event type | Number of patients (n = 48) | Proportion of readmitted patients (%) | Median time to event (days) |

| Worsening HF | 26 | 54.2 | 90 (60-150) |

| Acute coronary syndrome (MI + UA) | 9 | 18.8 | 120 (90-180) |

| Arrhythmia-related hospitalization | 7 | 14.6 | 150 (120-210) |

| Sudden cardiac death/mace | 4 | 8.3 | 210 (180-300) |

| Other cardiovascular causes | 2 | 4.2 | 180 (150-270) |

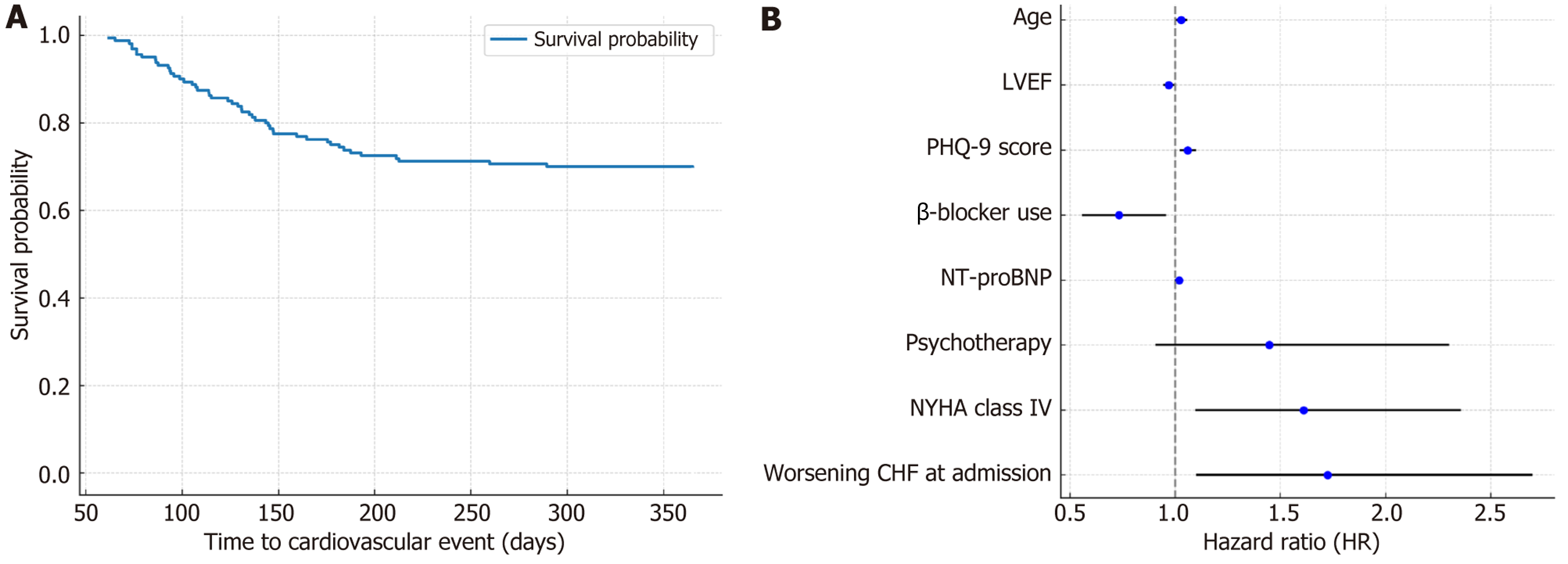

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis demonstrated a median EFS of 124 days (IQR: 93.5-150.5 days), with 50% of car

In univariable analysis, one-year cardiovascular readmission was significantly associated with older age (P = 0.042), lower LVEF (P = 0.006), elevated PHQ-9 scores (P < 0.001), higher NT-proBNP levels (P = 0.041), and absence of β-blocker therapy (P = 0.027). Clinical severity indicators at index admission, including NYHA class IV (P = 0.049) and acute decompensation (P = 0.041), were also more common among readmitted patients (Table 5). Multivariable Cox regression identified baseline depressive symptom severity (per-point increase in PHQ-9; HR = 1.059, 95%CI: 1.025-1.094, P < 0.001) as an independent predictor of readmission, along with lower LVEF (HR = 0.969, 95%CI: 0.947-0.991, P = 0.009), older age (HR = 1.028, 95%CI: 1.005-1.052, P = 0.016), and elevated NT-proBNP (HR = 1.018, 95%CI: 1.003-1.033, P = 0.021). NYHA class IV and index hospitalization for worsening HF were also independently associated with higher risk, whereas β-blocker therapy remained protective (HR = 0.732, P = 0.024; Figure 3B and Table 6).

| Variable | Event group (n = 48) | No event group (n = 112) | P value |

| Age, years | 77 ± 8 | 74 ± 9 | 0.042 |

| Male | 50 | 66 | 0.067 |

| Heart rate, bpm | 84 ± 14 | 81 ± 14 | 0.219 |

| NYHA class IV | 17 | 14 | 0.049 |

| Coronary artery disease | 61 | 52 | 0.284 |

| Prior MI | 46 | 35 | 0.191 |

| Hypertension | 58 | 63 | 0.548 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 31 | 37 | 0.441 |

| Low education level | 42 | 32 | 0.228 |

| Divorced/separated | 19 | 18 | 0.889 |

| Ischemic etiology | 52 | 65 | 0.113 |

| LVEF | 27 ± 7 | 32 ± 8 | 0.006 |

| LVEF ≤ 20% | 27 | 12 | 0.023 |

| PHQ-9 score | 9 ± 4 | 6 ± 3 | < 0.001 |

| NT-proBNP, median (interquartile range), pg/mL | 3950 (2300-5600) | 2900 (1600-4300) | 0.041 |

| Use of psychotherapy | 17 | 8 | 0.086 |

| β-blocker use at discharge | 48 | 72 | 0.027 |

| ACE inhibitor use | 60 | 74 | 0.091 |

| Diuretic use | 65 | 78 | 0.084 |

| Nitrate use | 46 | 52 | 0.486 |

| Antidepressant use | 10 | 12 | 0.723 |

| Anxiolytic use | 15 | 9 | 0.237 |

| Worsening CHF as admission | 63 | 41 | 0.041 |

| Variable | Hazard ratio | 95% confidence interval | P value |

| Age | 1.028 | 1.005-1.052 | 0.016 |

| LVEF | 0.969 | 0.947-0.991 | 0.009 |

| PHQ-9 score | 1.059 | 1.025-1.094 | < 0.001 |

| β-blocker use | 0.732 | 0.562-0.953 | 0.024 |

| NT-proBNP | 1.018 | 1.003-1.033 | 0.021 |

| Psychotherapy | 1.447 | 0.912-2.296 | 0.112 |

| NYHA class IV | 1.611 | 1.102-2.354 | 0.037 |

| Worsening CHF at admission | 1.723 | 1.103-2.694 | 0.031 |

Stratified analyses by HF phenotype revealed that the prognostic value of PHQ-9 was more pronounced among patients with reduced ejection fraction (HF with reduced ejection fraction, LVEF < 50%). In this group (n = 112), depression severity remained significantly associated with readmission risk (HR = 1.068, 95%CI: 1.027 to 1.111, P = 0.001). Among those with preserved ejection fraction (HF with preserved ejection fraction, LVEF ≥ 50%, n = 48), the association was attenuated and not statistically significant (HR = 1.021, 95%CI: 0.994-1.056, P = 0.097), suggesting phenotype-specific differences in psychocardiological vulnerability (Supplementary Table 3).

Additional subgroup analysis confirmed that patients with PHQ-9 ≥ 10 were older, more frequently female, and more likely to be readmitted than non-depressed counterparts. These trends align with established epidemiology and un

In this retrospective cohort study of patients with HF, we identified a remarkable and independent association between depressive symptom severity and impaired cardiac function and an increased risk of one-year cardiovascular event-related readmission. These findings not only reinforce the growing body of evidence linking depression to adverse cardiovascular outcomes but also highlight the prognostic utility of PHQ-9 as a simple, scalable tool for risk stratification in routine clinical care.

Emerging evidence supports the notion that depression in HF is not merely a prognostic marker but a potentially modifiable risk factor. Randomized controlled trials in other chronic disease populations have shown that depression treatment - whether pharmacologic, psychotherapeutic, or collaborative care - can improve both mental health and cli

Consistent with previous research, we observed a high prevalence of moderate to severe depressive symptoms, particularly among older and female patients - groups historically associated with greater vulnerability to psychological stress and adverse HF trajectories[13,14,19,20]. Importantly, our study adds to the existing literature by demonstrating that higher PHQ-9 scores are independently associated with lower LVEF, advanced NYHA functional class, and elevated NT-proBNP levels[21-23]. These findings suggest a pathophysiological interplay wherein depression may exacerbate neurohumoral dysregulation, sympathetic activation, and systemic inflammation - mechanisms previously implicated in HF progression[16-18].

Our results extend the observations of prior large-scale studies such as the SADHART-congestive heart failure trial and the OPTIMIZE-HF registry, which linked depression to increased mortality and hospitalizations in HF, yet did not quantify risk using standardized depression metrics[24]. By identifying that each one-point increase in PHQ-9 score confers a nearly 6% increase in readmission risk - independent of LVEF, NT-proBNP, and age - we provide clinically actionable data that could inform early post-discharge surveillance strategies[25-27]. Moreover, the clustering of rea

We also observed that patients with moderate/severe depression were significantly less likely to receive β-blockers or ACE inhibitors at discharge - therapies that remain the cornerstone of guideline-directed HF management[29]. This therapeutic gap may reflect a complex interplay of patient non-adherence, physician inertia, or perceived contraindications due to mental health status[30]. The protective effect of β-blocker use observed in our analysis suggests that enhancing medication adherence and eliminating barriers to optimal pharmacotherapy should be prioritized in this subgroup[25,27,28,31,32].

The observed association between depression severity and markers of cardiac dysfunction, such as reduced LVEF and elevated NT-proBNP levels, may reflect underlying pathophysiological processes shared by both conditions. Depression has been linked to autonomic nervous system dysregulation, resulting in heightened sympathetic activity and reduced heart rate variability, phenomena that are both associated with poor HF prognosis. Additionally, proinflammatory cytokines, hypothalamic pituitary adrenal axis hyperactivation, and endothelial dysfunction have been implicated in depression and HF progression. These shared pathways may create a bidirectional feedback loop; wherein psychological distress exacerbates cardiac dysfunction and worsening cardiac status amplifies depressive symptoms. Understanding these interactions could inform integrated treatment strategies that address psychological and physiological domains.

In addition to pharmacologic and psychiatric therapies, evidence-based non-pharmacologic interventions - such as structured telemonitoring, behavioral activation programs, and collaborative home-based care - have demonstrated efficacy in reducing hospital readmissions among HF patients with comorbid depression. It has been PHQ-9 scores were assessed only once at hospital admission reported that telehealth monitoring, when integrated with psychosocial support, significantly decreased 30-day readmission rates in depressed HF populations[29]. These findings support the imp

Our findings have several important clinical implications. First, they advocate for the systematic integration of depression screening - specifically PHQ-9 - into HF discharge planning and outpatient follow-up. Second, they support the need for collaborative care models that combine cardiology, psychiatry, and behavioral health interventions. Third, they suggest that existing HF guidelines may benefit from the inclusion of mental health considerations, particularly because comorbid depression appears to confer risk comparable to traditional hemodynamic predictors, such as LVEF or NT-proBNP levels[32]. Fourth, medication adherence was measured using the MMAS-4, a self-reported instrument that may be subject to recall and social desirability biases. While the MMAS-4 has been validated across diverse populations, it lacks objective confirmation through pharmacy refill records, electronic pill monitoring, or biomarker tracking. Future studies should incorporate multi-modal adherence assessment to strengthen the accuracy and validity of behavioral correlates.

Nonetheless, this study has limitations. Its retrospective, single-center design may limit generalizability, and residual confounding cannot be excluded despite multivariable adjustment. Depression severity was assessed only at index hos

This retrospective cohort study demonstrates that depression in HF patients is significantly associated with poor medication adherence, reduced LVEF, and increased risk of 1-year readmission. These findings highlight the critical psy

| 1. | Joynt KE, Whellan DJ, O'connor CM. Why is depression bad for the failing heart? A review of the mechanistic relationship between depression and heart failure. J Card Fail. 2004;10:258-271. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Triposkiadis F, Karayannis G, Giamouzis G, Skoularigis J, Louridas G, Butler J. The sympathetic nervous system in heart failure physiology, pathophysiology, and clinical implications. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:1747-1762. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 622] [Cited by in RCA: 705] [Article Influence: 41.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Grippo AJ, Johnson AK. Stress, depression and cardiovascular dysregulation: a review of neurobiological mechanisms and the integration of research from preclinical disease models. Stress. 2009;12:1-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 343] [Cited by in RCA: 315] [Article Influence: 18.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kaufman JS, Cooper RS, McGee DL. Socioeconomic status and health in blacks and whites: the problem of residual confounding and the resiliency of race. Epidemiology. 1997;8:621-628. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Linder SR, Lizer S, Doughty A. Screen and intervene: Depression's effect on CHF readmission. Nurs Manag. 2016;47:14-21. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 6. | Bartekova M, Radosinska J, Jelemensky M, Dhalla NS. Role of cytokines and inflammation in heart function during health and disease. Heart Fail Rev. 2018;23:733-758. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 214] [Article Influence: 30.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Jiang W, Alexander J, Christopher E, Kuchibhatla M, Gaulden LH, Cuffe MS, Blazing MA, Davenport C, Califf RM, Krishnan RR, O'Connor CM. Relationship of depression to increased risk of mortality and rehospitalization in patients with congestive heart failure. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:1849-1856. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 648] [Cited by in RCA: 657] [Article Influence: 26.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Altay H, Zorlu A, Kocum HT, Demircan S, Yilmaz N, Yilmaz MB. Relationship between parathyroid hormone and depression in heart failure. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2012;99:915-923. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Gao YH, Liu L. The relationship between NT-proBNP and Depression in Patients with Heart Failure. J Geriatr Cardiol. 2017;14:715-716. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Feola M, Garnero S, Vallauri P, Salvatico L, Vado A, Leto L, Testa M. Relationship between Cognitive Function, Depression/Anxiety and Functional Parameters in Patients Admitted for Congestive Heart Failure. Open Cardiovasc Med J. 2013;7:54-60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Gheorghiade M, Vaduganathan M, Fonarow GC, Bonow RO. Rehospitalization for heart failure: problems and perspectives. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:391-403. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 464] [Cited by in RCA: 565] [Article Influence: 40.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Chernoff RA, Messineo G, Kim S, Pizano D, Korouri S, Danovitch I, IsHak WW. Psychosocial Interventions for Patients With Heart Failure and Their Impact on Depression, Anxiety, Quality of Life, Morbidity, and Mortality: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Psychosom Med. 2022;84:560-580. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Hammash MH, Hall LA, Lennie TA, Heo S, Chung ML, Lee KS, Moser DK. Psychometrics of the PHQ-9 as a measure of depressive symptoms in patients with heart failure. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2013;12:446-453. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Nolan J, Batin PD, Andrews R, Lindsay SJ, Brooksby P, Mullen M, Baig W, Flapan AD, Cowley A, Prescott RJ, Neilson JM, Fox KA. Prospective study of heart rate variability and mortality in chronic heart failure: results of the United Kingdom heart failure evaluation and assessment of risk trial (UK-heart). Circulation. 1998;98:1510-1516. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 800] [Cited by in RCA: 824] [Article Influence: 29.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Robinson S, Howie-Esquivel J, Vlahov D. Readmission risk factors after hospital discharge among the elderly. Popul Health Manag. 2012;15:338-351. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Botto J, Martins S, Moreira E, Cardoso JS, Fernandes L. The magnitude of depression in heart failure patients and its association with NYHA class. Eur Psychiatr. 2021;64:S342-S342. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Vancheri F, Longo G, Henein MY. Left ventricular ejection fraction: clinical, pathophysiological, and technical limitations. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2024;11:1340708. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Wleklik M, Lee CS, Lewandowski Ł, Czapla M, Jędrzejczyk M, Aldossary H, Uchmanowicz I. Frailty determinants in heart failure: Inflammatory markers, cognitive impairment and psychosocial interaction. ESC Heart Fail. 2025;12:2010-2022. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Ahmed A. A propensity matched study of New York Heart Association class and natural history end points in heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2007;99:549-553. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Santaguida PL, Don-Wauchope AC, Oremus M, McKelvie R, Ali U, Hill SA, Balion C, Booth RA, Brown JA, Bustamam A, Sohel N, Raina P. BNP and NT-proBNP as prognostic markers in persons with acute decompensated heart failure: a systematic review. Heart Fail Rev. 2014;19:453-470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in RCA: 154] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Tran NN, Bui VS, Nguyen VH, Hoang TP, Vo HL, Nguyen HT, Duong MT. Prevalence of depression among heart failure inpatients and its associated socio-demographic factors: implications for personal-and family-based treatment management in health facilities in Vietnam. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2022;26:879-887. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | O'Donnell CJ, Schwartz Longacre L, Cohen BE, Fayad ZA, Gillespie CF, Liberzon I, Pathak GA, Polimanti R, Risbrough V, Ursano RJ, Vander Heide RS, Yancy CW, Vaccarino V, Sopko G, Stein MB. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Cardiovascular Disease: State of the Science, Knowledge Gaps, and Research Opportunities. JAMA Cardiol. 2021;6:1207-1216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 18.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Holland R, Rechel B, Stepien K, Harvey I, Brooksby I. Patients' self-assessed functional status in heart failure by New York Heart Association class: a prognostic predictor of hospitalizations, quality of life and death. J Card Fail. 2010;16:150-156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Kato N, Kinugawa K, Shiga T, Hatano M, Takeda N, Imai Y, Watanabe M, Yao A, Hirata Y, Kazuma K, Nagai R. Depressive symptoms are common and associated with adverse clinical outcomes in heart failure with reduced and preserved ejection fraction. J Cardiol. 2012;60:23-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Rutledge T, Reis VA, Linke SE, Greenberg BH, Mills PJ. Depression in heart failure a meta-analytic review of prevalence, intervention effects, and associations with clinical outcomes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:1527-1537. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 981] [Cited by in RCA: 1102] [Article Influence: 55.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Sokoreli I, de Vries JJ, Riistama JM, Pauws SC, Steyerberg EW, Tesanovic A, Geleijnse G, Goode KM, Crundall-Goode A, Kazmi S, Cleland JG, Clark AL. Depression as an independent prognostic factor for all-cause mortality after a hospital admission for worsening heart failure. Int J Cardiol. 2016;220:202-207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Redwine LS, Wirtz PH, Hong S, Bosch JA, Ziegler MG, Greenberg B, Mills PJ. Depression as a potential modulator of Beta-adrenergic-associated leukocyte mobilization in heart failure patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:1720-1727. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Certo Pereira J, Presume J, Araujo I, Carvalho Gouveia C, Rodrigues Silva S, Ferreira P, Carvalho R, Pepe B, Maia Das Neves N, Rodrigues C, Henriques C, Marques F, Guerreiro R, Fonseca C. Depression and heart failure - the incidence of depressive symptoms assessed by the PHQ9 and their association with HF outcomes. Eur Heart J. 2023;44:ehad655.2381. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 29. | Lossnitzer N, Feisst M, Wild B, Katus HA, Schultz JH, Frankenstein L, Stock C. Cross-lagged analyses of the bidirectional relationship between depression and markers of chronic heart failure. Depress Anxiety. 2020;37:898-907. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Arifin Y, Saifur Rohman M, Tjahjono CT, Sargowo D, Rahimah AF. OR22. Correlation Between the New York Heart Association Functional Class with depression in Heart Failure patients: A Cross sectional study. Eur Heart J Suppl. 2021;23:suab122.021. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Patel N, Chakraborty S, Bandyopadhyay D, Amgai B, Hajra A, Atti V, Das A, Ghosh RK, Deedwania PC, Aronow WS, Lavie CJ, Di Tullio MR, Vaduganathan M, Fonarow GC. Association between depression and readmission of heart failure: A national representative database study. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2020;63:585-590. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/