Published online Dec 19, 2025. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v15.i12.109546

Revised: August 18, 2025

Accepted: September 22, 2025

Published online: December 19, 2025

Processing time: 139 Days and 1.3 Hours

Pelvic organ prolapse (POP) can lead to urinary incontinence, fecal incontinence, and other symptoms, affecting the quality of life, which results in anxiety and depression and other negative emotions in many patients. Trans-vaginal sacro

To explore the effect of VSSLS in the treatment of POP and its influence on anxiety and depression among patients.

Sixty patients with moderate to severe POP who underwent surgical treatment between January 2023 and June 2024 in Suzhou Ninth Hospital Affiliated to Soo

No significant differences in baseline data, preoperative POP Quantification mea

VSSLS demonstrated a significant effect on the treatment of moderate and severe POP, as it can reduce the prolapse distance and PFDI-20 and PFIQ-7 scores and improve anxiety and depression among patients.

Core Tip: Pelvic organ prolapse can cause lower back pain, sexual dysfunction, urinary incontinence, etc., resulting in anxiety and depression among patients. This study presents the vaginal sacrospinous ligament suspension technique, which secures the prolapsed vaginal apex to the sacrospinous ligament. This technique is advantageous for repairing pelvic floor defects, shortening prolapse distance, improving both sexual and pelvic function, and consequently alleviating anxiety and depression among patients.

- Citation: Zhang RR, Zhao RH, Zhang L, Ma RY, Chen MZ. Transvaginal sacrospinous ligament fixation: Efficacy in treating pelvic prolapse and influence on patients’ anxiety and depression. World J Psychiatry 2025; 15(12): 109546

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v15/i12/109546.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v15.i12.109546

Pelvic organ prolapse (POP) is mainly caused by the weakness or damage to supporting structures, such as pelvic fascia, ligaments, muscles, and soft tissue attachments, which can lead to abdominal sagging, back pain, sexual dysfunction, frequent urination, urine leakage, and defecation problems. It adversely affects patients’ quality of life and work, leading to negative emotions such as anxiety and depression[1,2]. Nevertheless, many clinicians pay more attention to the therapeutic effect and less attention to the changes in patients’ psychological status when treating moderate to severe POP. Surgery is the main approach to the treatment of moderate to severe POP[3]. Surgical treatments of POP have varied effects. Total vaginal hysterectomy (TVH) is a common procedure for female patients with POP without fertility needs[4]. TVH involves initially removing the prolapsed pelvic organs to fundamentally treat the prolapse and relieve abdominal bulge, lumbosacral pain, and other symptoms[5]. TVH is becoming increasingly popular among patients and doctors; however, after a simple TVH, the vaginal stump will sag over time, increasing pelvic dysfunction and leading to anxiety and depression in patients after surgery. Therefore, other interventions need to be sought in TVH to augment the therapeutic effect.

From the anatomical perspective, the sacrospinous ligament is composed of dense connective tissue, which is distributed in the first transverse process of the tail and the lateral edge of the fourth sacral foramen to the sciatic spine[6]. It aligns with the direction of the coccygeal muscle, creating the coccygeal muscle-sacral spine ligament complex. Its fixed position and robustness make it suitable for anchoring and suspension in pelvic floor reconstruction surgery[7]. A study showed that vaginal sacrospinous ligament suspension (VSSLS) is crucial in the repair of the prolapsed pelvic floor[8]. It separates the pararectal space to the sacrospinous ligament through the posterior vaginal wall incision and then secures the prolapsed vaginal apex on the sacrospinous ligament to fully maintain the physiological axis of the vagina, which is suitable in repairing pelvic floor defects and maintaining normal pelvic floor function. However, whether adding VSSLS in TVH can augment the efficacy of POP treatment and reduce anxiety and depression in patients is unclear. In this study, patients with moderate and severe POP treated only with TVH were enrolled as the control group, and the effect of adding VSSLS after TVH in the treatment of these patients was analyzed to provide a reference for the clinical treatment of this condition.

This retrospective study enrolled 60 patients with moderate to severe POP who underwent surgical treatment at Suzhou Ninth Affiliated Hospital of Soochow University between January 2023 and June 2024. According to different treatment methods, they were divided into a control group and an observation group, with 30 patients in each group. The control group underwent TVH alone, whereas the observation group was treated with both VSSLS and TVH.

Inclusion criteria: (1) Fulfillment of the diagnostic criteria for POP as outlined in the “Chinese Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pelvic Organ Prolapse (2020 edition)”[9]; (2) Meeting the surgical indications; (3) Grade III-IV POP based on the POP Quantification (POP-Q) system[10]; (4) Absence of hypertension, diabetes, and other chronic diseases; (5) Absence of previous mental disorders; (6) No desire for fertility; and (7) Participation in follow-up and having complete follow-up records.

Exclusion criteria: (1) Diagnosis of cervical cancer, ovarian cancer, endometrial cancer, and other gynecological malignancies; (2) Acute infections of the genital tract such as vaginitis and vaginal mucosal ulcer before surgery; (3) Abnormal anatomy of pelvic floor structures such as vaginal stenosis, vaginal shortening, pelvic deformity, and hip prosthesis; (4) A history of pelvic surgery or lumbosacral and spinal trauma; and (5) Severe speech communication disorder or deafness.

The control group underwent TVH. The patient was assisted into the bladder lithotomy position and underwent general anesthesia with tracheal intubation. Sterile towels were used for disinfection to ensure that the surgical area was sterile, and a single-use J-type sterile retractor was used to open the vagina. A transverse incision was made approximately 5 cm below the cervical groove of the patient’s bladder. The anterior vaginal wall was incised, the bladder and rectal cervical spaces were separated layer by layer, and the retroflex peritoneum was opened. The bilateral sacral ligaments, uterine ligaments, uterosacral ligaments, and uterine arteries and veins were excised using an electrocoagulation knife, followed by the removal of the uterus. For patients with anterior vaginal wall bulging, the anterior vaginal wall was repaired by excising the excess vaginal wall, and the remaining vaginal wall was continuously sutured with absorbable sutures starting from the urethral orifice. In patients with posterior vaginal wall bulging, the posterior vaginal wall was repaired by making a transverse incision of approximately 5 cm on the posterior vaginal wall along the posterior fornix. The vaginal rectal space was separated, and the excess vaginal wall was excised. A U-shaped continuous suture using absorbable sutures was made to reapproximate the vaginal rectal fascia and the posterior vaginal wall mucosa. Once the suturing was completed, compression hemostasis was performed.

The observation group underwent VSSLS and TVH. Briefly, after transvaginal hysterectomy, the stump of the vaginal mucosa was lifted using forceps. The right vaginal wall and the pararectal space were manually dissected, the bladder was pushed upward and outward, the loose connective tissue between the rectum and the cervix was separated, and the rectum was pushed to the opposite side to expose the paracervical tissues. Then, the loose parauterine tissues on the right side toward the right ischial tuberosity were carefully dissected, and the sacrospinous ligament beside the right ischial spine was exposed and palpated. The ligament was further located by gently pressing with the index finger of the left hand, aiming to reach the posterior one-third of the sacrospinous ligament as much as possible while using the index finger of the left hand as a guide. Then, the sacrospinous ligament puncture device was utilized to suture the middle section of the sacrospinous ligament with No. 7 Ethibond non-absorbable suture, leaving it in place. After the repair of the anterior and posterior walls of the vagina, the anterior thread-retaining needle was used to suture the submucosal fascia tissue for fixation (with full-thickness penetration), ensuring that the top non-absorbable suture was fully embedded to prevent exposure. After knotting, the tip of the vagina (or the cervix) was secured on the surface of the sacrospinous ligament, and the anterior and posterior vaginal walls were repaired. Following thorough observation, if no active bleeding was noted, a sterile iodophor gauze was plugged into the vagina to control bleeding. The gauze was taken out 24-36 hours after the surgery.

Postoperatively, the vital signs of the two groups were closely monitored, antibiotics were given for prophylaxis, and appropriate fluid supplementation was provided. In general, the catheter was removed on postoperative day 1, depending on the patient’s recovery and ability to get out of bed. Patients were encouraged to get out of bed early, engage in bladder function exercises, eat a balanced diet with fresh fruits and vegetables, ensure adequate rest, avoid pelvic baths and sexual intercourse for 3 months, clean the vulva daily to keep it clean and dry and prevent infection, and present for regular follow-up.

Baseline data: Age, body mass index, previous pregnancy and parity, prolapse duration, prolapse severity, and previous history of abdominal surgery were compared between the two groups.

Perioperative indicators: The perioperative observation indicators of the two groups were compared, including operation time, intraoperative blood loss, postoperative exhaust time, hospitalization time, postoperative complications during hospitalization (such as infection, urinary retention, and bleeding), and postoperative pain intensity. Postoperative pain intensity was evaluated using the Visual Analog Scale (VAS)[11]. A score of 0 indicated absence of pain; 1-3, mild pain; 4-6, moderate pain; and 7-10, severe pain.

Prolapse distance: The POP-Q was used to measure the prolapse distance before and 3 months after surgery. Specifically, after urinating, the patient assumed a bladder lithotomy position, and the Valsalva maneuver was performed. Using the hymen as a reference, the prolapse distance was measured in the anterior wall, posterior wall, and apex of the vagina, with the inner side of the hymen as a negative number and the outer side as a positive number.

Sexual function: Before and 6 months after surgery, the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) was used to evaluate the sexual function of the patients[12]. This scale consists of six dimensions: Low sexual desire, vaginal dryness disorder, sexual arousal disorder, orgasm disorder, sexual intercourse pain, and sexual life satisfaction. Each dimension is scored 1-6, with the highest score of 36: The higher the score, the better the sexual function.

Pelvic function: Pelvic function was evaluated using the Pelvic Floor Dysfunction Inventory 20 (PFDI-20) and Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire 7 (PFIQ-7) before and 6 months after surgery[13]. PFDI-20 scale includes POP and anorectal and urogenital disorders, with a total of 3 dimensions and 20 items. The total score is 100, and the higher the score, the more serious the pelvic dysfunction and the worse the quality of life[14]. The PFIQ-7 scale includes urination distress, colorectal and anal distress, or some discomfort of the vagina, which affects their daily living activities, interpersonal relationships, and emotions. The total score is 21 points, and the higher the score, the greater the effect, and the worse the quality of life of patients[15].

Anxiety and depression: The Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) and Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS) were used to evaluate the anxiety and depression symptoms before and 6 months after surgery[16,17]. Both scales consist of 20 items, each with a maximum score of 100, and the higher the score, the more severe the symptoms of anxiety and depression.

IBM SPSS Statistics version 27.0 was used for data analysis. Measurement data were analyzed to confirm that they conform to the normal distribution by the Shapiro-Wilk test method, expressed as mean ± SD, and the two groups were compared by the independent sample t-test. The count data adoption rate and composition ratio [n (%)] were compared using the χ2 test. The correlation was analyzed using Pearson’s correlation method. Assuming a test level of α = 0.05, P < 0.05 indicates a significant level.

No significant differences were found among age, body mass index, parity, delivery time, degree of prolapse, and previous abdominal surgery history between the two groups (P > 0.05; Table 1).

| Baseline data | Control group (n = 30) | Observer group (n = 30) | t/χ2 value | P value |

| Age (years) | 59.23 ± 4.87 | 58.57 ± 4.16 | 0.564 | 0.575 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 24.58 ± 2.93 | 24.39 ± 2.85 | 0.255 | 0.799 |

| Previous pregnancy (times) | 3.11 ± 0.75 | 3.07 ± 0.71 | 0.212 | 0.832 |

| Parity (times) | 2.14 ± 0.43 | 2.18 ± 0.46 | 0.348 | 0.729 |

| Prolapse time (year) | 3.28 ± 0.87 | 3.39 ± 0.92 | 0.476 | 0.636 |

| Prolapse degree | 0.601 | 0.438 | ||

| Degree 3 | 17 (56.67) | 14 (46.67) | ||

| Degree 4 | 13 (43.33) | 16 (53.33) | ||

| Previous abdominal surgery | 0.341 | 0.559 | ||

| Have | 7 (39.02) | 9 (39.02) | ||

| Not have | 23 (39.02) | 21 (39.02) |

The observation group had longer surgery time and greater intraoperative blood loss than the control group (P < 0.05). Regarding postoperative pain intensity, the VAS score was slightly higher in the observation group than in the control group on postoperative day 1 (6.21 ± 1.23 vs 5.60 ± 1.05, P = 0.043); however, the scores of both groups were comparable on postoperative day 7 (2.26 ± 0.37 vs 2.18 ± 0.47, P = 0.467). This indicates that the pain caused by adding VSSLS to TVH for the treatment of POP is temporary. The comparison of the exhaust time, hospitalization time, and complications during postoperative hospitalization between the two groups (P > 0.05; Table 2).

| Perioperative indicators | Control group (n = 30) | Observer group (n = 30) | t/χ2 value | P value |

| Surgical duration (minutes) | 97.18 ± 19.45 | 114.43 ± 22.32 | 3.191 | 0.002 |

| Intraoperative blood loss (mL) | 89.54 ± 16.56 | 102.65 ± 17.84 | 2.950 | 0.004 |

| Postoperative exhaust time (hours) | 18.87 ± 1.29 | 19.18 ± 1.36 | 0.906 | 0.369 |

| Postoperative pain intensity | ||||

| VAS score on the 1st day after operation (points) | 5.60 ± 1.05 | 6.21 ± 1.23 | 2.066 | 0.043 |

| VAS score on the 7th day after operation (points) | 2.18 ± 0.47 | 2.26 ± 0.37 | 0.733 | 0.467 |

| Hospitalization time (days) | 9.68 ± 1.23 | 9.59 ± 1.18 | 0.289 | 0.773 |

| Postoperative complications | ||||

| Vaginal Infection | 1 (3.33) | 2 (6.67) | 0.351 | 0.554 |

| Retention of urine | 2 (6.67) | 0 (0.00) | 2.069 | 0.150 |

| Bleeding | 1 (3.33) | 3 (10.00) | 1.071 | 0.301 |

Before the surgery, the POP-Q measurements of the anterior wall, posterior wall, and apex of the vagina were not significantly different between the two groups (P > 0.05). However, the follow-up examination 3 months after the surgery revealed that the POP-Q measurements of the anterior and posterior walls and the apex of the vagina in both groups were lower than those before the surgery, particularly in the observation group compared with that in the control group (P < 0.05; Table 3).

| Group | n | Anterior vaginal | Posterior vaginal | Top of vagina | |||

| Preoperative | 3 months after surgery | Preoperative | 3 months after surgery | Preoperative | 3 months after surgery | ||

| Control group | 30 | 1.53 ± 0.36 | -1.86 ± 0.43a | -1.28 ± 0.78 | -2.17 ± 0.38a | 1.52 ± 0.38 | -2.94 ± 0.26a |

| Observer group | 30 | 1.60 ± 0.38 | -2.23 ± 0.37a | -1.33 ± 0.72 | -2.46 ± 0.49a | 1.63 ± 0.32 | -3.11 ± 0.17a |

| t value | 0.733 | 3.572 | 0.258 | 2.562 | 1.213 | 2.997 | |

| P value | 0.467 | 0.001 | 0.797 | 0.013 | 0.230 | 0.004 | |

Before the surgery, no significant differences in the FSFI scores were noted between the two groups (P > 0.05). Six months after the surgery, the FSFI score of the observation group was significantly higher than that of the control group (26.21 ± 4.92 vs 22.54 ± 4.65 points, P < 0.001; Table 4).

Before the surgery, no significant difference in PFDI-20 and PFIQ-7 scores was found between the two groups (P > 0.05). The reexamination 6 months after the surgery operation showed that the PFDI-20 (47.76 ± 3.89 vs 51.87 ± 4.61, P < 0.001) and PFIQ-7 (10.46 ± 1.79 vs 12.78 ± 1.84, P < 0.001) scores were lower in the observation group than in the control group (Table 5).

Before the surgery, no significant difference in SAS and SDS scores was found between the two groups (P > 0.05). In the re-examination 6 months after the surgery, the SAS (47.21 ± 4.37 vs 54.98 ± 6.59, P < 0.001) and SDS (42.87 ± 4.86 vs 51.25 ± 5.43, P < 0.001) scores were lower in the observation group than in the control group (Table 6).

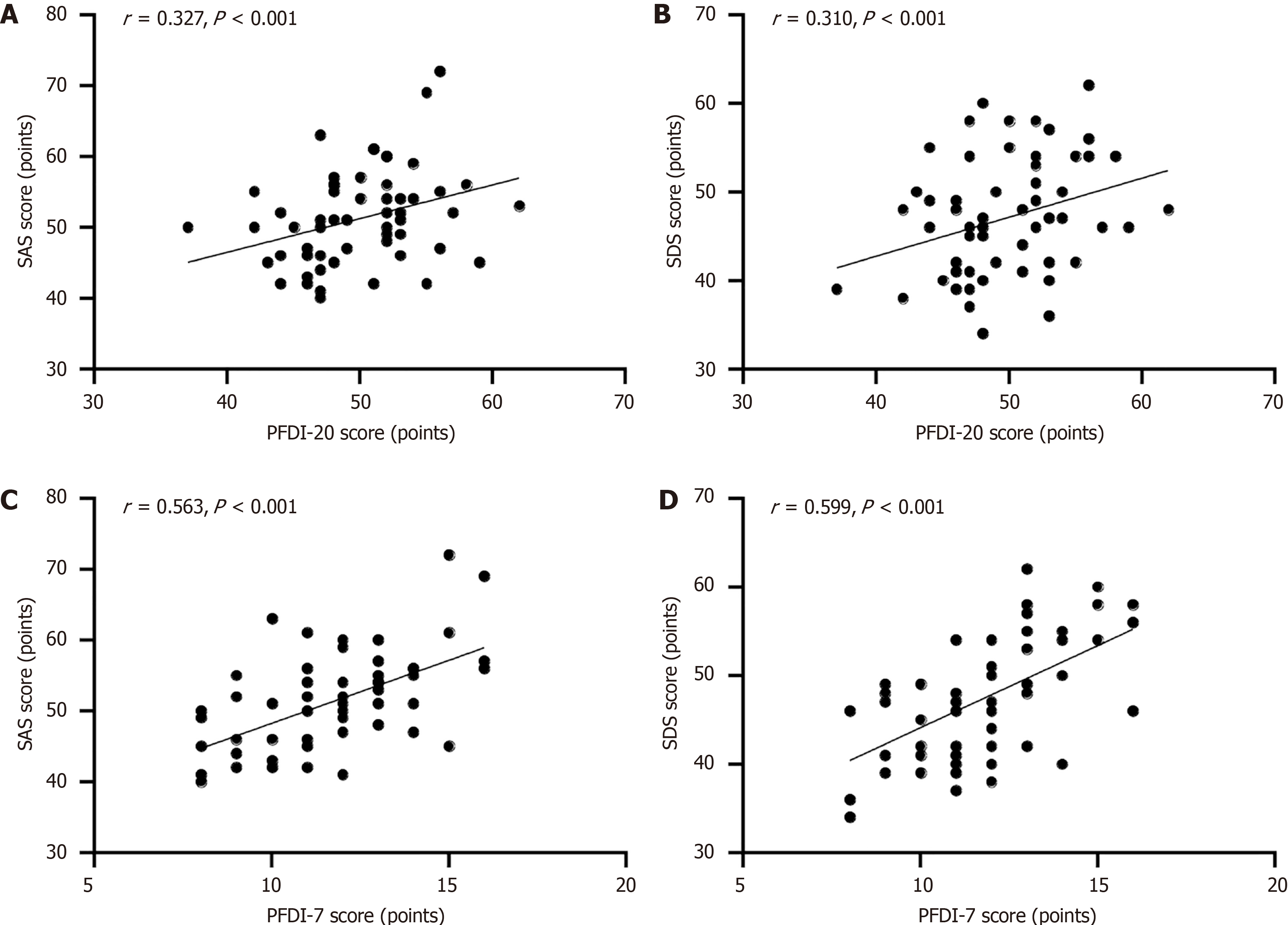

The Pearson correlation analysis showed that the postoperative PFDI-20 (r = 0.327, 0.310; P < 0.001) and PFIQ-7 (r = 0.563, 0.599; P < 0.001) scores showed positive correlation with the SAS and SDS scores (Figure 1). This finding indicates that as the pelvic function improves after POP surgery, the patients’ anxiety and depression symptoms are also significantly alleviated.

POP is characterized by urinary incontinence, fecal incontinence, sexual dysfunction, and chronic pelvic pain, and as the disease progresses, patients experience pelvic inflammatory disease, adnexitis, and other complications, adversely affecting their physical and mental health[18]. Therefore, effective POP treatment is important to improve its symptoms and improve the physical and mental health of patients.

TVH, a common procedure for the treatment of POP, can alter the anatomical structure of the pelvic floor. However, it only involves removing the uterosacral cardinal ligament. Although it fundamentally addresses the prolapse, it also greatly disrupts the anatomical integrity of the vagina[19]. In addition, after total hysterectomy, the vaginal apex loses ligament support, leading to a decline in pelvic floor muscle strength. Daily standing, abdominal pressure, and other factors may increase patients’ susceptibility to recurrent vaginal apex prolapse. Moreover, TVH is associated with varying degrees of vaginal stump changes, resulting in an empty pelvic floor, and the vagina becomes shorter. In addition, a simple continuous suture of the vaginal stump, suture exposure, and stump eversion can easily trigger an inflammatory reaction or inflammatory polyp formation in the stump, leading to pelvic dysfunction. Kalata et al[20] indicated that pelvic dysfunction will directly affect the quality of life and generate negative emotions, such as anxiety and depression, among patients.

VSSLS secures the cervix or the apex of the vagina to the sacrospinous ligament on the anterior side of the sacrum through a vaginal incision, which can restore the normal support angle, ensure stable attachment of the vaginal stump, and strengthen the pelvic floor structure[21]. As VSSLS is crucial in correcting apical prolapse, it can greatly compensate for the shortcomings of TVH[22]. In this study, VSSLS was combined with TVH (observation group) to treat moderate to severe POP, and its effectiveness was compared with that of TVH alone (control group). The results revealed longer operation time and greater intraoperative blood loss in the observation group than in the control group. This was possibly due to the addition of VSSLS after TVH, which extended the surgical time and increased intraoperative blood loss. As regards postoperative pain intensity, the VAS scores of the observation group were slightly higher than that of the control group on postoperative day 1; however, both groups had basically the same scores on postoperative day 7. This finding indicates that the pain relief caused by adding VSSLS to TVH for POP is temporary. No significant dif

Patients with POP are at risk of recurrent POP, anorectal disorder, and genitourinary disorder after surgery and experience some discomfort, such as urinary, colorectal, and anal distress, which affects their daily living activities, interpersonal relationships, and emotions[27]. In this study, the PFDI-20 and PFIQ-7 scores of the observation group 6 months after surgery were lower than those of the control group. The likely reason was that the observation group underwent VSSLS to reconstruct the pelvic floor structures, resulting in a more rigid anatomical structure that helps maintain the physiological axis of the vagina, avoids displacement, preserves vaginal function, and significantly improves the prolapse condition. Consequently, pelvic floor dysfunction symptoms are fewer after surgery.

Discomfort symptoms, such as urination and defecation distress, resulting from pelvic dysfunction will affect daily living activities and quality of life of the patients, resulting in anxiety, depression, and other negative emotions. A study revealed that the relief of lower urinary tract symptoms, prolapse, and colorectal-anal symptoms after POP surgery improves depression and anxiety in patients[28]. In the present study, the SAS and SDS scores of the observation group were significantly lower than those of the control group 6 months after the surgery. Furthermore, a Pearson correlation analysis showed that in patients with POP, the postoperative PFDI-20 and PFIQ-7 scores were positively correlated with both the SAS and SDS scores. This finding indicates that as the pelvic function improves after POP surgery, the patients’ anxiety and depression symptoms are significantly alleviated. The likely reason is that the short-term effect of TVH is significant. If the apex of the vagina is not anchored to a ligament, the vaginal stump will gradually descend over time, leading to abdominal sagging, and symptoms of pelvic dysfunction such as abnormal urination and defecation. These urination and defecation problems may expose patients to embarrassing situations, increasing their psychological burden[29], thereby increasing anxiety, depression, and other negative emotions. Conversely, in the observation group that underwent both VSSLS and TVH, the sacral and round ligaments were anchored and suspended on the vaginal apex, providing enhanced support. Consequently, POP symptoms are significantly alleviated, and the duration of treatment effect is sustained. This approach helps in reducing negative emotions associated with recurrent POP symptoms, encouraging patients to confront their condition positively, enhancing their self-confidence in recovery, and enabling them to approach daily life and work with an optimistic attitude, ultimately promoting patients’ mental health and maintaining positive emotions.

This study demonstrated that VSSLS is significantly effective in treating POP and positively affects patients’ anxiety and depression; however, it has many limitations. First, this is a single-center retrospective cohort study with a small sample size and a short follow-up period, which limited its representativeness. Therefore, future prospective multicenter studies with a larger sample and extended follow-up observation time are warranted to further verify the benefits of VSSLS in the treatment of POP. Second, VSSLS requires the gynecologist team to have a high degree of familiarity with the anatomical structure. Differences in experience among gynecologist teams from different units may lead to different results. Therefore, multicenter collaborative studies are needed for further verification. Third, after VSSLS for POP, potential uncontrollable confounders may influence the postoperative psychological state of patients, such as family emergencies, which must be controlled as much as possible.

The addition of VSSLS in TVH in the treatment of moderate and severe POP extends the surgical time and intraoperative blood loss but does not increase the postoperative exhaust time, hospitalization time, and postoperative complications. Nevertheless, it can reduce the prolapse distance. It improves pelvic function and alleviates patients’ anxiety and dep

| 1. | Kalata U, Pomian A, Jarkiewicz M, Kondratskyi V, Lippki K, Barcz E. Influence of Stress Urinary Incontinence and Pelvic Organ Prolapse on Depression, Anxiety, and Insomnia-A Comparative Observational Study. J Clin Med. 2023;13:185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ghetti C, Skoczylas LC, Oliphant SS, Nikolajski C, Lowder JL. The Emotional Burden of Pelvic Organ Prolapse in Women Seeking Treatment: A Qualitative Study. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2015;21:332-338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Vigna A, Barba M, Frigerio M. Long-Term Outcomes (10 Years) of Sacrospinous Ligament Fixation for Pelvic Organ Prolapse Repair. Healthcare (Basel). 2024;12:1611. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Stark M, Malvasi A, Mynbaev O, Tinelli A. The Renaissance of the Vaginal Hysterectomy-A Due Act. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:11381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Meriwether KV, Antosh DD, Olivera CK, Kim-Fine S, Balk EM, Murphy M, Grimes CL, Sleemi A, Singh R, Dieter AA, Crisp CC, Rahn DD. Uterine preservation vs hysterectomy in pelvic organ prolapse surgery: a systematic review with meta-analysis and clinical practice guidelines. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;219:129-146.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 165] [Article Influence: 20.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Goh JTW, Ganyaglo GYK. Sacrospinous fixation: Review of relevant anatomy and surgical technique. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2023;162:842-846. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Giraudet G, Ruffolo AF, Lallemant M, Cosson M. The anatomy of the sacrospinous ligament: how to avoid complications related to the sacrospinous fixation procedure for treatment of pelvic organ prolapse. Int Urogynecol J. 2023;34:2329-2332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Morgan DM, Larson K. Uterosacral and sacrospinous ligament suspension for restoration of apical vaginal support. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2010;53:72-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Urogynecology Subgroup; Chinese Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology; Chinese Medical Association. [Chinese guideline for the diagnosis and management of pelvic orang prolapse (2020 version)]. Zhonghua Fu Chan Ke Za Zhi. 2020;55:300-306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Zhang H, Zhu L, Xu T, Lang JH. [Utilize the simplified POP-Q system in the clinical practice of staging for pelvic organ prolapse: comparative analysis with standard POP-Q system]. Zhonghua Fu Chan Ke Za Zhi. 2016;51:510-514. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Shalabna E, Cohen N, Assaf W, Zilberlicht A, Abramov Y. Frailty and pelvic organ prolapse: Colpocleisis with or without hysterectomy as a treatment modality in elderly patients. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2025;306:2-5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | ter Kuile MM, Brauer M, Laan E. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) and the Female Sexual Distress Scale (FSDS): psychometric properties within a Dutch population. J Sex Marital Ther. 2006;32:289-304. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 221] [Cited by in RCA: 239] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Barber MD, Walters MD, Bump RC. Short forms of two condition-specific quality-of-life questionnaires for women with pelvic floor disorders (PFDI-20 and PFIQ-7). Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:103-113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 826] [Cited by in RCA: 1043] [Article Influence: 49.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | de Arruda GT, de Andrade DF, Virtuoso JF. Internal structure and classification of pelvic floor dysfunction distress by PFDI-20 total score. J Patient Rep Outcomes. 2022;6:51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Volontè S, Zurlo A, Cola A, Barba M, Frigerio M. Italian validation of the pelvic floor Impact questionnaire - 7 (PFIQ-7). Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2025;305:1-4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Zung WW. A rating instrument for anxiety disorders. Psychosomatics. 1971;12:371-379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2251] [Cited by in RCA: 2943] [Article Influence: 53.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 17. | Zung WW. A self-rating depression scale. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1965;12:63-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5900] [Cited by in RCA: 6288] [Article Influence: 209.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Vermeulen CKM, Schuurman B, Coolen AWM, Meijs-Hermanns PR, van Leijsen SAL, Veen J, Bongers MY. The effectiveness and safety of laparoscopic uterosacral ligament suspension: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BJOG. 2023;130:1568-1578. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Shah NM, Berger AA, Zhuang Z, Tan-Kim J, Menefee SA. Long-term reoperation risk after apical prolapse repair in female pelvic reconstructive surgery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022;227:306.e1-306.e16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kalata U, Jarkiewicz MM, Barcz EM. Depression and anxiety in patients with pelvic floor disorders. Ginekol Pol. 2023;94:748-751. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Rostaminia G, Abramowitch S, Chang C, Goldberg RP. Transvaginal sacrospinous ligament suture rectopexy for obstructed defecation symptoms: 1-year outcomes. Int Urogynecol J. 2021;32:3045-3052. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Coolen AWM, van IJsselmuiden MN, van Oudheusden AMJ, Veen J, van Eijndhoven HWF, Mol BWJ, Roovers JP, Bongers MY. Laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy versus vaginal sacrospinous fixation for vaginal vault prolapse, a randomized controlled trial: SALTO-2 trial, study protocol. BMC Womens Health. 2017;17:52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Stairs J, Jain M, Chen I, Clancy A. Complications After Uterosacral Ligament Suspension Versus Sacrospinous Ligament Fixation at Vaginal Hysterectomy: A Retrospective Cohort Study of the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program Database. Urogynecology (Phila). 2022;28:834-841. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Chapman GC, Slopnick EA, Roberts K, Sheyn D, Wherley S, Mahajan ST, Pollard RR. National Analysis of Perioperative Morbidity of Vaginal Versus Laparoscopic Hysterectomy at the Time of Uterosacral Ligament Suspension. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2021;28:275-281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Bradley MS, Bickhaus JA, Amundsen CL, Newcomb LK, Truong T, Weidner AC, Siddiqui NY. Vaginal Uterosacral Ligament Suspension: A Retrospective Cohort of Absorbable and Permanent Suture Groups. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2018;24:207-212. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Peng L, Liu YH, He SX, Di XP, Shen H, Luo DY. Is absorbable suture superior to permanent suture for uterosacral ligament suspension? Neurourol Urodyn. 2020;39:1958-1965. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Vrijens D, Berghmans B, Nieman F, van Os J, van Koeveringe G, Leue C. Prevalence of anxiety and depressive symptoms and their association with pelvic floor dysfunctions-A cross sectional cohort study at a Pelvic Care Centre. Neurourol Urodyn. 2017;36:1816-1823. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Kalata U, Jarkiewicz M, Pomian A, Zwierzchowska AJ, Horosz E, Majkusiak W, Rutkowska B, Barcz EM. The Influence of Successful Treatment of Stress Urinary Incontinence and Pelvic Organ Prolapse on Depression, Anxiety, and Insomnia-A Prospective Intervention Impact Assessment Study. J Clin Med. 2024;13:1528. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Brand AM, Rosas S, Waterink W, Stoyanov S, van Lankveld JJDM. Conceptualization and Inventory of the Sexual and Psychological Burden of Women With Pelvic Floor Complaints; A Mixed-Method Study. Sex Med. 2022;10:100504. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/