Published online Dec 19, 2025. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v15.i12.108449

Revised: July 18, 2025

Accepted: October 11, 2025

Published online: December 19, 2025

Processing time: 167 Days and 1.5 Hours

The coexistence of rheumatological and immunological diseases with nephro

To evaluate the effectiveness of motivational psychological nursing in the redu

We conducted a retrospective cohort study involving 206 patients with rheumatological and immunological diseases complicated by nephropathy and who were treated between January 2021 and January 2025. The inclusion criteria were as follows: Aged 18-75 years, met the diagnostic criteria for rheumatological and immunological diseases with a renal biopsy classification above type II, hospitalized in our facility, received consistent basic nursing care, and had complete clinical data available. Participants allotted to the observation group (n = 102) receiving motivational psychological nursing, and those in the control group (n = 104) received standard care. Psychological status was assessed using Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS), Beck Anxiety Inventory, Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale, Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS), Patient Health Questionnaire-9, and other standardized measures. Intervention lasted throughout hospitalization, with follow-up assessments conducted before discharge.

Pre-intervention, anxiety, and depression scores were similar across groups. Postintervention, the observation group showed significant reductions in anxiety (SAS: 44.53 ± 6.72 vs 46.79 ± 6.94; P = 0.018) and depression (SDS: 45.20 ± 5.07 vs 46.97 ± 5.25; P = 0.014) compared with the control group. General self-efficacy (P = 0.044), health-related quality of life (P = 0.044), and World Health Organization Quality of Life (P = 0.040) scores also revealed significant improvement.

Motivational psychological nursing considerably reduces anxiety and depression in patients with rheumatological and immunological diseases complicated by nephropathy, which enhances the overall quality of life.

Core Tip: This study investigates the impact of motivational psychological nursing on anxiety and depression in patients with rheumatological and immunological diseases complicated by nephropathy. By integrating motivational interviewing and cognitive-behavioral therapy, our findings demonstrate significant reductions in anxiety and depression scores, alongside improvements in self-efficacy and quality of life, highlighting a promising therapeutic approach for this complex patient group.

- Citation: Li N, Zhao J, Tang YP, Niu YQ. Motivational psychological nursing reduces anxiety and depression in patients with rheumatic and immunological diseases combined with nephropathy. World J Psychiatry 2025; 15(12): 108449

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v15/i12/108449.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v15.i12.108449

The intersection of rheumatological and immunological diseases with nephropathy represents a challenging and mul

Psychological comorbidities, such as anxiety and depression, are prevalent among this patient population and adversely affect their disease prognosis, adherence to treatment regimens, and their quality of life[5]. Management of these psychological aspects is crucial because mental health directly influences physiological outcomes in chronic disease states[6]. Traditional medical care models often inadequately address these psychological needs, which highlights a gap in comprehensive patient care[6]. Bridging this gap necessitates the exploration of innovative nursing and supportive care interventions aimed at holistic patient management[7].

Motivational psychological nursing emerges as a promising approach within this context. Rooted in principles of motivational interview and cognitive-behavioral therapy, this nursing intervention aims to enhance patients’ intrinsic motivation toward health-promoting behaviors while addressing the emotional and psychological barriers they en

The integration of psychological support within nursing care remarkably reduces symptoms of anxiety and depression in chronic illnesses[11]. However, the specific effect of such interventions on patients suffering from compounded rheumatological and nephrological conditions remains underexplored[12]. Given the intricate interplay between psychological well-being and chronic disease management, the efficacy of motivational psychological nursing interventions must be investigated to reveal valuable insights into the improvement of comprehensive care strategies in this patient population[12]. This study employed a retrospective cohort design and examined the potential of motivational psychological nursing in influencing anxiety and depression levels in patients diagnosed with rheumatological and immunological diseases complicated by nephropathy.

This research utilized a retrospective cohort design to examine 206 patients diagnosed with rheumatological and immunological diseases combined with nephropathy and who received treatment at Shaanxi Provincial People’s Hospital and the Second Hospital of Shanxi Medical University between January 2021 and January 2025. Data on baseline characteristics, disease diagnoses, variations in anxiety and depression scores, and enhancements in the quality of life were collected from an electronic medical record system.

This work received approval from the Institutional Review Board and Ethics Committee of Shaanxi Provincial People’s Hospital. Informed consent was waived by the Committee because the research exclusively involved de-identified patient data, which eliminated potential harm or impact on patient care.

The diagnosis of rheumatological and immunological diseases was determined based on clinical manifestations and auxiliary examinations, in accordance with the diagnostic criteria in Kelley and Firestein's Textbook of Rheumatology[13].

The specific criteria include the following: RA: Characterized by symmetrical swelling and pain in small joints and mor

SLE: Manifested as multisystem involvement with positive antinuclear antibodies (ANA), antidouble-stranded DNA, and anti-Smith antibodies.

SSc: Features include Raynaud’s phenomenon and skin tightening, supported by positive ANA, antitopoisomerase I (anti-Scl-70), and anticentromere antibodies.

Gout: Identified by the detection of acute monoarthritis (e.g., the first metatarsophalangeal joint), elevated serum uric acid levels, and urate crystals in the joint fluid.

Behcet’s disease: Diagnosed through oral ulcers, genital ulcers, uveitis, and a positive pathergy test.

Psoriatic arthritis: Associated with psoriasis, negative RF, and imaging findings revealing bone erosion or new bone formation.

Renal biopsy classification: According to Brenner and Rector’s The Kidney[14], renal biopsy classification for nephro

Types I and II: Denoted by mild pathological changes and negligible clinical symptoms and were therefore excluded from this study.

Type III: Characterized by focal proliferative glomerulonephritis with segmental inflammatory reactions, cellular proliferation, and inflammatory cell infiltration in the glomeruli.

Type IV: Indicated by diffuse proliferative glomerulonephritis, which is characterized by extensive inflammatory damage to the glomeruli, and potentially leads to rapid renal function deterioration.

Type V: Defined by membranous nephropathy with thickening of the glomerular basement membrane, immune complex deposition, and resulting massive proteinuria.

Type III + V: Described by concurrent focal glomerular inflammation and diffuse filtration barrier dysfunction.

Type IV + V: Displayed as the combination of diffuse glomerular inflammatory damage and filtration barrier dysfunction.

The inclusion criteria: Aged 18-75 years; met the diagnostic criteria for rheumatological and immunological diseases[13], with a renal biopsy classification above type II[14], hospitalized in our facility, received consistent basic nursing care, and had complete clinical data available.

The exclusion criteria: Cognitive impairment, severe underlying diseases, organ dysfunction, malignant tumors, alcohol or drug dependence, language barriers, neurodegenerative diseases (such as stroke, multiple sclerosis, and Parkinson’s disease), or diagnosed psychiatric disorders (excluding any degree of mental health conditions).

We enrolled 206 patients in accordance with these criteria. Using electronic medical records, patients were assigned to either the observation (n = 102) or the control group (n = 104) based on the nursing method of treatment they received.

Patient data, including age, gender, occupation, marital status, educational level, medical history, laboratory test results, and details pertaining to rheumatological and immunological symptoms, were collected from an electronic medical record system. These information were obtained from records of the patients’ most recent diagnosis before hospitalization. In addition, patients completed a questionnaire assessing anxiety and depression upon admission, and it was administered again prior to discharge to evaluate alterations in their psychological status.

Prior to or on the day of hospitalization, the patients underwent laboratory tests to assess renal function. Each patient provided approximately 10 mL fresh morning urine for quantitative protein analysis and active urine sediment examination. The procedures were as follows:

Quantitative urine protein analysis: The pyrogallol red molybdate method was employed, and the reagent kit 05486962190 was used (F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd., Switzerland). The analysis was conducted by Hitachi 7180 Clinical Chemistry Analyzer by Hitachi High-Technologies Corporation, Japan.

Active urine sediment examination: Microscopic examination was performed using the fluorescence method with the UF-1000I/UF-1000IR urine sediment staining reagent kit (Sysmex Corporation, Japan).

Moreover, 3 mL fasting venous blood was drawn from each patient using a nonanticoagulant blood collection tube. Blood was allowed to clot for 30 minutes and then centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 minutes to separate the serum. The following serum tests were conducted:

Serum creatinine measurement: The sarcosine oxidase method was used (reagent kit 715062 from Beckman Coulter, United States.), and analysis was performed utilizing an AU5800 Series Clinical Chemistry Analyzer.

C3 and C4 measurement: Immunoturbidimetry was performed to measure the C3 and C4 Levels. The reagent kits for C3 (N0329) and C4 (OS65-21A) were supplied by Siemens Healthineers, Germany and Beckman Coulter Inc., United States., respectively. The PF-350 Specific Protein Analyzer (Dirui Industrial Co., Ltd., China) was used for these measurements.

The control group received standard inpatient care during hospitalization. Nursing staff strictly adhered to medication management procedures, which ensured accurate dosage and timing, and documented any adverse drug reactions. The researchers also developed individualized nutrition and exercise plans for each patient and provided detailed guidance.

The observation group received additional motivational nursing interventions based on the standard protocol:

Psychological intervention: Nursing staff conducted dynamic assessments of patients’ psychological statuses to address their mental and physical conditions. They employed a positive expectation feedback mechanism to improve patients’ emotional states.

Family support: Psychology-trained nurses guided patients’ families to develop and implement family support plans tailored to the patients’ psychological needs, which enhances familial care.

Environmental motivation: A health -education display area on rheumatological and immunological nephropathy was set up in the ward, and a peer support mechanism was established to foster a positive treatment atmosphere.

Role model demonstration: Patients who recovered were invited to share their rehabilitation experiences through videos, face-to-face discussions, and organized experience-sharing sessions to help current patients build confidence in their recovery.

A standardized psychological measurement tools was employed to assess anxiety and depression levels among hospitalized patients.

The specific scales for anxiety assessment: (1) Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) measures subjective anxiety levels using a Likert 4-point scoring system, with standardized scores ranging from 25 to 100. The scale comprises 20 items, with each rated on a scale from 1 (none or little of the time) to 4 (most or all of the time). Clinical grading was as follows: < 50 indicates the normal range; 50-59 suggests mild anxiety; 60-69 reflects moderate anxiety; ≥ 70 signifies severe anxiety. The scale’s reliability, as indicated by Cronbach’s alpha, was 0.820[15]; (2) Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI): Consists of 21 items scored on a 0-3 scale, with the total score ranging from 0 to 63. Each item assesses specific symptoms of anxiety, such as nervousness, dizziness, and fear of losing control. Clinical grading criteria are as follows: 0-7, minimal anxiety; 8-15, mild; 16-25, moderate; 26-63, severe anxiety. BAI had a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.846[16]; and (3) Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAMA): Covers 14 items related to somatic and psychic anxiety symptoms, and it is scored on a 0-4 scale. The total score ranges from 0 to 56, with < 7 being normal, 7-14 indicating mild anxiety, 15-21 representing moderate anxiety, and > 21 signaling severe anxiety. Its Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.756[17].

The scales for depression assessment: (1) Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS) evaluates depressive symptom severity, with a standardized score range of 25 to 100. The clinical grading is as follows: < 53 for the normal range, 53-62 for mild depression, 63-72 for moderate depression, and ≥ 73 for severe depression. SDS had a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.81[18]; (2) Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9): Used to screen and assess depressive symptoms’ severity, with scores ranging from 0 to 27. Clinical grading is as follows: 0-4 for no depression, 5-9 for mild symptoms, 10-14 for moderate symptoms, 15-19 for moderately severe symptoms, and 20-27 for severe symptoms. PHQ-9 had a Cronbach’s alpha equal to 0.81[19]; (3) Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D): Covers depressive mood, positive mood, somatic sy

For the comprehensive evaluation of nursing outcomes, the patients’ self-belief, quality of life, and rheumatological and immunological disease status were assessed using the following scales:

Self-belief assessment: The General Self-Efficacy Scale (GSES) measures an individual’s confidence in managing challenges using a 4-point scoring system. Scores are categorized as follows: < 20, low confidence; 20-30, moderate confidence; > 30 high confidence in handling various situations. The GSES showed a high reliability, with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.91[21].

Quality of life assessment: Health-related quality of life (HRQL) was assessed using the Short-Form 36-item (SF-36) scale, which is scored from 0 to 100 (with 0 being the poorest and 100 being the best result). The widely used SF-36 had a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient ranging from 0.689 to 0.972[22]; World Health Organization Quality of Life (WHOQO)-BREF: This scale evaluates physical and psychological health, social relationships, and environmental factors using a Likert 5-point scale. It is useful for comparative analyses and had a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient ranging from 0.70 to 0.77[23].

Rheumatological and immunological disease assessment scales: Foot Function Scale (FF) assesses foot function, with scores ranging from 0 to 100. The scores are interpreted as follows: 0-20, mild impairment; 21-50, moderate impairment; 51-80, severe impairment; 81-100, extremely severe impairment. This scale exhibited a high reliability, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.94[24]; Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ): This questionnaire evaluates the functional status of patients with rheumatic diseases, with scores ranging from 0 to 3. Interpretation includes 0-1 for good functional status, 1-2 for moderate limitations, and 2-3 for severe limitations. The HAQ exhibited a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.83[25].

Data analysis was conducted using SPSS 29.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States). Categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages [n (%)] and analyzed using χ2 test. The normality of continuous variables was evaluated using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Normally distributed continuous variables were reported as mean ± SD, and group com

Similar mean ages were observed between the observation (52.85 ± 9.75 years) and control groups (53.54 ± 9.33 years), with no statistically significant difference (t = 0.515, P = 0.607) (Table 1). Disease duration also showed no significant difference between the groups, with averages of 10.89 ± 2.27 and 11.26 ± 2.12 years in the observation and control groups (t = 1.230, P = 0.220), respectively. Gender distribution showed comparability, with males constituting 49.02% of the observation group and 44.23% of the control group, and females accounting for 50.98% and 55.77%, respectively (χ2 = 0.475, P = 0.491). Employment status, living arrangements with family, education levels, and marital status were similarly distributed between the groups, with P values of 0.925, 0.972, 0.772, and 0.841, respectively, which indicate no significant differences. The prevalence of hypertension was nearly identical in both groups (50.98% and 50.96% in the observation and control groups, respectively; χ2 = 0.000, P = 0.998), and diabetes incidence did not differ significantly (6.86% vs 10.58%, χ2 = 0.891, P = 0.345). In addition, no significant variations were observed in the systolic and diastolic blood pressure readings or in estimated glomerular filtration rates, with P values of 0.707, 0.374, and 0.986, respectively. These results indicate that the two groups were well-matched across key demographic and clinical variables, which facilitates a reliable assessment of the intervention’s effect.

| Parameters | Observation group (n = 102) | Control group (n = 104) | t/χ2 | P value |

| Age, year | 52.85 ± 9.75 | 53.54 ± 9.33 | 0.515 | 0.607 |

| Disease duration, years | 10.89 ± 2.27 | 11.26 ± 2.12 | 1.230 | 0.220 |

| Gender | 0.475 | 0.491 | ||

| Male | 50 (49.02) | 46 (44.23) | ||

| Female | 52 (50.98) | 58 (55.77) | ||

| Employment | 0.009 | 0.925 | ||

| Yes | 70 (68.63) | 72 (69.23) | ||

| No | 32 (31.37) | 32 (30.77) | ||

| Live with family | 0.001 | 0.972 | ||

| Yes | 96 (94.12) | 98 (94.23) | ||

| No | 6 (5.88) | 6 (5.77) | ||

| Education | 2.529 | 0.772 | ||

| No education | 11 (10.78) | 7 (6.73) | ||

| Primary school | 40 (39.22) | 39 (37.50) | ||

| High school | 17 (16.67) | 16 (15.38) | ||

| Vocational education | 19 (18.63) | 24 (23.08) | ||

| Bachelor | 14 (13.73) | 15 (14.42) | ||

| Master degree | 1 (0.98) | 3 (2.88) | ||

| Marital status | 0.834 | 0.841 | ||

| Single | 2 (1.96) | 2 (1.92) | ||

| Married | 83 (81.37) | 88 (84.62) | ||

| Divorced/separated | 4 (3.92) | 2 (1.92) | ||

| Widowed | 13 (12.75) | 12 (11.54) | ||

| Hypertension | 52 (50.98) | 53 (50.96) | 0.000 | 0.998 |

| Diabetes | 7 (6.86) | 11 (10.58) | 0.891 | 0.345 |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 126.22 ± 8.31 | 125.81 ± 7.51 | 0.377 | 0.707 |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 77.60 ± 7.51 | 76.61 ± 8.42 | 0.892 | 0.374 |

| Estimated GFR, mL/minute/1.73 m2 | 132.61 ± 44.02 | 132.71 ± 38.33 | 0.018 | 0.986 |

RA was the most common condition in both groups (47.06% in the observation group and 47.12% in the control group). SLE was detected in 11.76% of the observation group and 10.58% of the control group (Table 2). The control group displayed a slightly higher presence of SSc (11.54%) than the observation group (9.80%). Gout and Behcet disease were observed in approximately similar proportions in both groups (29.41% vs 28.85% for gout and 0.98% vs 0.96% for Behcet disease, respectively). Cases of psoriatic arthritis were also comparable, with one case each in both groups. The analysis of kidney biopsy class revealed no significant differences, with classes III or III+V observed in 30.39% of the observation group and 26.92% of the control group, and classes IV or IV + V were noted in 61.76% and 57.69%, respectively. The pure V class was more prevalent in the control group (15.38%) than in the observation group (7.84%). χ2 tests for disease type and kidney biopsy class yielded P values of 0.995 and 0.238, respectively, which corroborates the lack of significant difference between the two groups. Overall, this balance in disease characteristics ensures that subsequent analyses can reliably attribute differences in psychological outcomes to the intervention.

| Parameters | Observation group (n = 102) | Control group (n = 104) | t/χ2 | P value |

| Type of disease | None | 0.995 | ||

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 48 (47.06) | 49 (47.12) | ||

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | 12 (11.76) | 11 (10.58) | ||

| Systemic sclerosis | 10 (9.80) | 12 (11.54) | ||

| Gout | 30 (29.41) | 30 (28.85) | ||

| Behcet disease | 1 (0.98) | 1 (0.96) | ||

| Psoriatic arthritis | 1 (0.98) | 1 (0.96) | ||

| Kidney biopsy class | 2.873 | 0.238 | ||

| III or III + V | 31 (30.39) | 28 (26.92) | ||

| IV or IV + V | 63 (61.76) | 60 (57.69) | ||

| Pure V | 8 (7.84) | 16 (15.38) |

Similar 24 hours urinary protein excretions were observed between the groups, with the observation and control groups showing means of 442.98 ± 122.32 and 451.14 ± 126.12 mg, respectively (t = 0.471, P = 0.638) (Table 3). The prevalence of active urine sediment was observed in 6.86% of the observation group and 8.65% of the control group, with no significant difference (χ2 = 0.231, P = 0.631). Serum creatinine levels were closely matched, with 67.21 ± 20.82 and 66.82 ± 19.98 μmol/L determined for the observation and control groups, respectively (t = 0.139, P = 0.889). Regarding immu

| Parameters | Observation group (n = 102) | Control group (n = 104) | t/χ2 | P value |

| Urinary protein, mg/24 hours | 442.98 ± 122.32 | 451.14 ± 126.12 | 0.471 | 0.638 |

| Active urine sediment, n (%) | 7 (6.86) | 9 (8.65) | 0.231 | 0.631 |

| SCr (μmol/L) | 67.21 ± 20.82 | 66.82 ± 19.98 | 0.139 | 0.889 |

| Immunologic factors, mg/dL | ||||

| Serum C3 | 868.14 ± 236.12 | 891.12 ± 203.23 | 0.749 | 0.455 |

| Serum C4 | 180.85 ± 103.01 | 194.11 ± 70.96 | 1.074 | 0.284 |

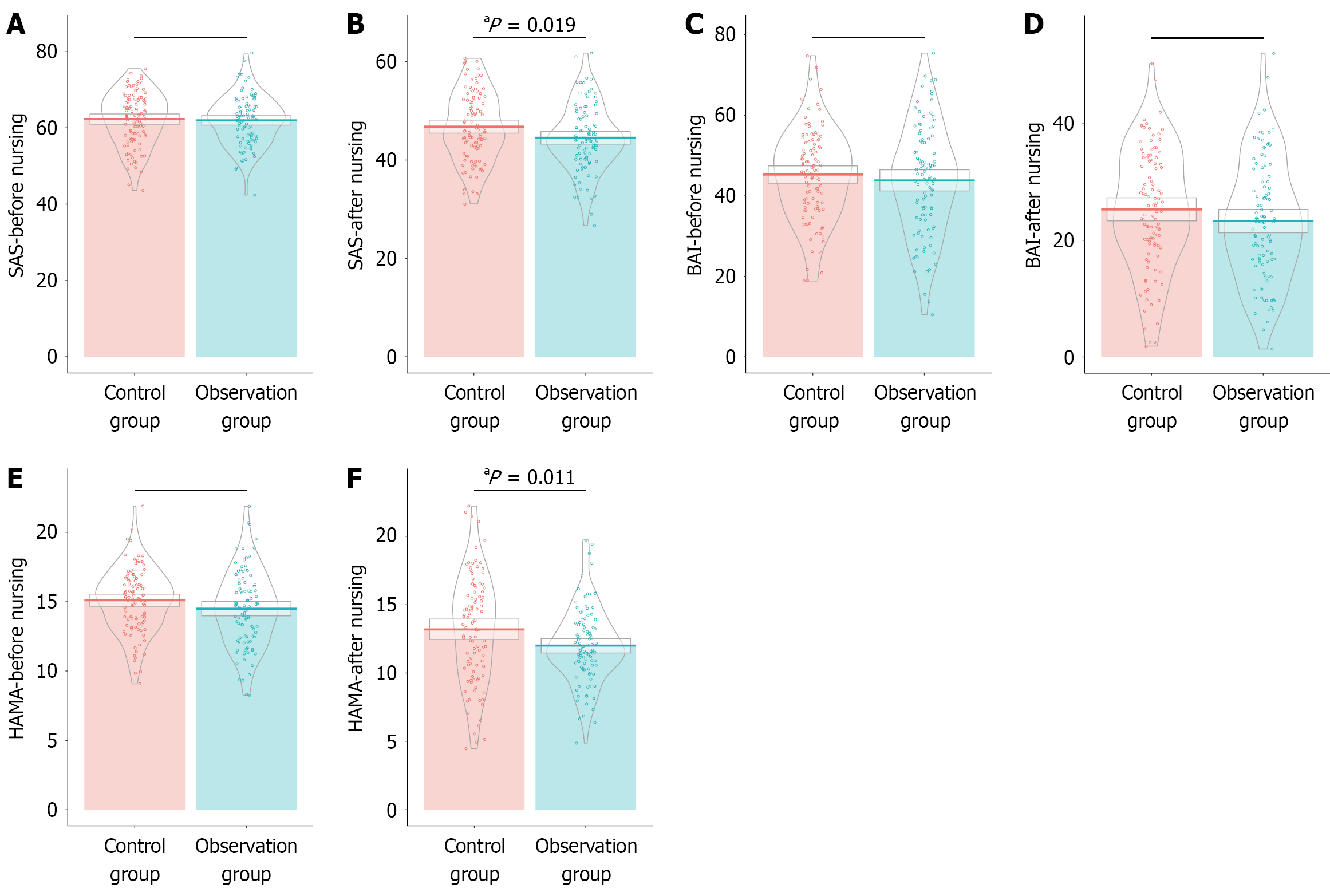

Prior to nursing intervention, SAS scores were comparable between the observation (61.98 ± 6.46) and control groups (62.31 ± 6.98), with no statistically significant difference (t = 0.350, P = 0.727) (Figure 1). However, after nursing inter

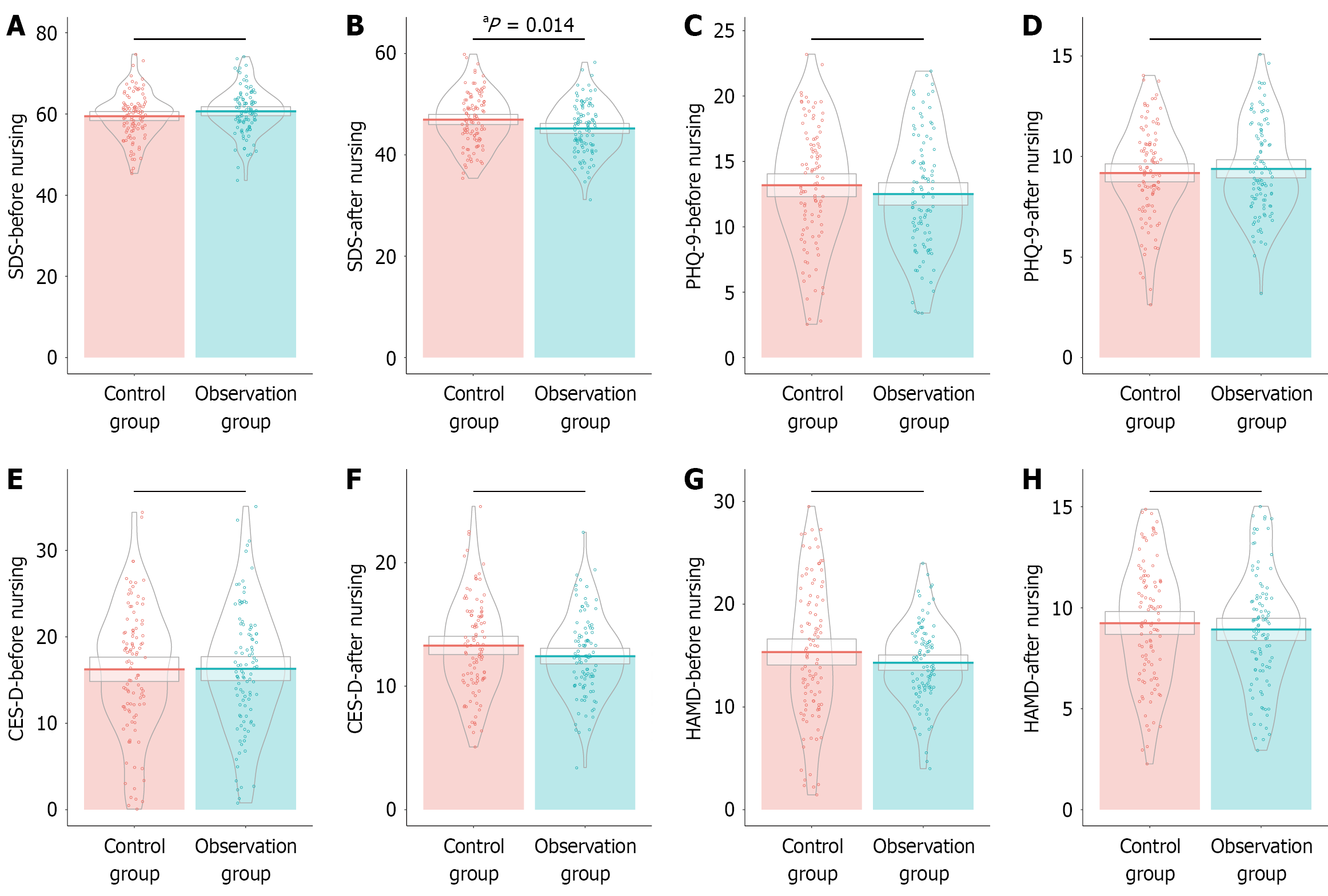

Similar initial SDS scores were observed between the observation (60.67 ± 5.61) and control groups (59.49 ± 5.75), with no significant difference (t = 1.496, P = 0.136) (Figure 2). However, postintervention, the observation group exhibited significantly reduced SDS scores (45.20 ± 5.07) compared with the control group (46.97 ± 5.25), which indicates a meaningful reduction in depression levels (t = 2.470, P = 0.014). On the other hand, PHQ-9 scores demonstrated no significant difference between groups before (12.51 ± 4.42 for the observation group vs 13.18 ± 4.58 for the control group,

Before nursing intervention, similar GSES scores were observed between the observation (22.18 ± 2.52) and control groups (22.56 ± 2.78), with no statistically significant difference (t = 1.022, P = 0.308) (Table 4). However, after the intervention, the observation group showed a significantly higher increase in GSES scores (29.63 ± 2.72) compared with that in the control group (28.87 ± 2.69), which indicates a statistically significant enhancement in self-efficacy (t = 2.036, P = 0.043). This increase implies that the motivational psychological nursing intervention effectively bolstered the patients’ self-belief, which is an important component for the management of chronic conditions and improvement of overall mental well-being of individuals with rheumatism and immunological diseases combined with nephropathy.

| Parameters | Observation group (n = 102) | Control group (n = 104) | t | P value |

| GSES | ||||

| Before nursing | 22.18 ± 2.52 | 22.56 ± 2.78 | 1.022 | 0.308 |

| After nursing | 29.63 ± 2.72 | 28.87 ± 2.69 | 2.036 | 0.043 |

Similar HRQL scores were observed between the observation (75.34 ± 5.93) and control groups (74.55 ± 6.28), with no significant difference (t = 0.920, P = 0.359) (Table 5). Postintervention, the observation group displayed a significant improvement in HRQL scores (76.86 ± 6.24) compared with the control group (75.06 ± 6.59), which indicates an en

| Parameters | Observation group (n = 102) | Control group (n = 104) | t | P value |

| HRQL | ||||

| Before nursing | 75.34 ± 5.93 | 74.55 ± 6.28 | 0.920 | 0.359 |

| After nursing | 76.86 ± 6.24 | 75.06 ± 6.59 | 2.020 | 0.045 |

| WHOQOL | ||||

| Before nursing | 49.13 ± 2.70 | 48.86 ± 2.82 | 0.717 | 0.474 |

| After nursing | 47.78 ± 3.05 | 46.91 ± 3.03 | 2.050 | 0.042 |

Prior to the nursing intervention, the FF scores showed no significant difference between the observation (44.08 ± 12.43) and control groups (44.22 ± 12.3) (t = 0.080, P = 0.937) (Table 6). Following the intervention, both groups experienced improvements in FF scores, with the observation and control group scoring 27.95 ± 9.67 and 30.00 ± 10.21, respectively. However, this difference did not reach statistical significance (t = 1.480, P = 0.140). By contrast, the HAQ scores indicated significant improvements. Before nursing intervention, the HAQ scores between the observation (1.58 ± 0.65) and control groups showed no significant difference (1.67 ± 0.70) (t = 0.946, P = 0.345). Postintervention, the observation group displayed a notable reduction in HAQ scores (0.94 ± 0.25) compared with the control group (1.02 ± 0.30), which exhibited statistical significance (t = 2.040, P = 0.043). These results suggest that although the motivational psychological nursing intervention led to a meaningful improvement in overall physical functioning, as measured by HAQ, the changes observed in FF did not achieve statistical significance, which implies the intervention’s greater effect on general health assessment outcomes.

| Parameters | Observation group (n = 102) | Control group (n = 104) | t | P value |

| FF | ||||

| Before nursing | 44.08 ± 12.43 | 44.22 ± 12.3 | 0.080 | 0.937 |

| After nursing | 27.95 ± 9.67 | 30.00 ± 10.21 | 1.480 | 0.140 |

| HAQ | ||||

| Before nursing | 1.58 ± 0.65 | 1.67 ± 0.70 | 0.946 | 0.345 |

| After nursing | 0.94 ± 0.25 | 1.02 ± 0.30 | 2.040 | 0.043 |

The effect sizes for key parameters and psychological scales were reported to address the concern regarding the clinical significance of the findings (Table 7). Scales, such as HAMA, SDS, WHOQOL, and GSES, showed moderate to large effect sizes, which suggests meaningful improvements in anxiety, depression, the quality of life, and self-efficacy following the intervention, respectively. These effect sizes provide additional insights into the clinical relevance of our intervention beyond statistical significance.

| Parameters | Cohen_d | Parameters | Cohen_d |

| Age, year | 0.072 | PHQ-9-before nursing | 0.148 |

| Disease duration, years | 0.171 | PHQ-9-after nursing | 0.087 |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 0.052 | CES-D-before nursing | 0.011 |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 0.124 | CES-D-after nursing | 0.239 |

| Estimated GFR, mL/minute/1.73 m2 | 0.002 | HAMD-before nursing | 0.191 |

| Urinary protein, mg/24 hours | 0.066 | HAMD-after nursing | 0.109 |

| SCr (μmol/L) | 0.019 | GSES-before nursing | 0.142 |

| Immunologic factors-Serum C3, mg/dL | 0.104 | GSES-after nursing | 0.284 |

| Immunologic factors-Serum C4, mg/dL | 0.150 | HRQL-before nursing | 0.128 |

| SAS-before nursing | 0.049 | HRQL-after nursing | 0.281 |

| SAS-after nursing | 0.331 | WHOQOL-before nursing | 0.100 |

| BAI-before nursing | 0.117 | WHOQOL-after nursing | 0.286 |

| BAI-after nursing | 0.194 | FF-before nursing | 0.011 |

| HAMA-before nursing | 0.242 | FF-after nursing | 0.206 |

| HAMA-after nursing | 0.355 | HAQ-before nursing | 0.132 |

| SDS-before nursing | 0.208 | HAQ-after nursing | 0.284 |

| SDS-after nursing | 0.344 |

In this study, we investigated the influence of motivational psychological nursing on anxiety and depression in patients with rheumatological and immunological diseases combined with nephropathy. The primary clinical outcomes, enhanced anxiety, and depression scores postintervention highlight the potential efficacy of interventions involving motivational psychological nursing. This improvement can be attributed to several underlying mechanisms[26,27]. A key component of this nursing strategy is the focus on psychological interventions that foster a positive feedback loop, which boost patients’ emotional well-being[28]. It leverages principles of cognitive-behavioral therapy, which encourages positive thinking patterns and emotional adjustment[29]. Psychological assessments and dynamic interactions with nursing staff likely create an environment where patients feel supported, which consequently reduces feelings of anxiety and depression[30].

The family support aspect of the intervention crucially contributes to these improvements[31]. By involving family members in the caregiving process, patients gain emotional support and a sense of community[31]. This outcome was consistent with that of existing literature suggesting that social support can buffer the adverse psychological effects of chronic illnesses[32]. Families were engaged through tailored support plans, which might have alleviated the psychological burdens typically borne solely by the patient[33]. This inclusion likely facilitated communication and under

Furthermore, the environmental motivation strategy cannot be underestimated. The creation of a positive ward atmosphere through health education and peer support might have contributed considerably to the observed outcomes[34]. Educational materials not only increase patients’ knowledge about their conditions but also empower them to actively participate in their care[35]. The introduction of recovered patients as role models likely provided hope and tangible evidence of potential recovery, which is crucial in fostering a healing mindset[35]. Such strategies align with the behavior change model, which posits that witnessing tangible examples of successful behavior change can motivate others to follow suit.

The observed enhancements in self-belief, as measured by the GSES, further elucidate the mechanism behind psychological improvements. An increase in self-efficacy suggests that patients feel more capable of managing their illness, which in itself can reduce anxiety and depression[36]. The intervention likely fortified the patients’ perceived control over their health, which is a crucial determinant of psychological well-being. The enhancement of self-efficacy can lead to better health outcomes given that individuals who believe in their ability to influence events that affect their lives engage more in proactive health behaviors and demonstrate an improved psychological adjustment.

Remarkably, the intervention also contributed to the improvement of HRQL and WHOQOL scores, which indicates that the benefits of the program extended beyond psychological improvements to affect overall life satisfaction and functioning. This holistic enhancement possibly resulted from the multifaceted nature of the intervention, which did not just exclusively focus on psychological support but also integrated physical health management through individualized nutrition and exercise plans[37]. Such comprehensive care probably improved the patients’ overall health perceptions not only through the management of the psychological components but also via the improvement of physical health status through better disease management.

Despite significant reductions in anxiety and depression scores, the rheumatological and immunological disease assessment scales, such as the FF and HAQ, respectively, displayed varying degrees of impact. Although the HAQ scores indicated significant improvements postintervention, changes in FF scores failed to reach statistical significance, which suggests a differential effect on physical function domains. This discrepancy may reflect the intervention’s stronger focus on psychological rather than physical rehabilitation efforts[38]. Future iterations of this program may benefit from a stronger emphasis on physical therapy elements to ensure the consistency of improvements across all functional domains.

Notably, this study also highlighted the potential of motivational psychological nursing to improve life quality measures, such as HRQL and WHOQOL. The inverse relationship observed between these variables and anxiety/depression scores underscores the intertwined nature of psychological health and life quality outcomes. Improved quality of life can be a vital determinant in the reduction of psychological distress because patients with high quality of life perceptions are often adequately positioned to engage with and respond positively to psychological interventions.

Our findings suggest that motivational psychological nursing can be effectively integrated into the routine care for patients with rheumatological and immunological diseases complicated by nephropathy. Specifically, structured motivational interviewing sessions and cognitive-behavioral therapy modules can enhance patient outcomes. Regular psychological assessments and the involvement of multidisciplinary teams can further support patients, which potentially leads to improved mental health and quality of life. These protocols provide practical guidance for healthcare providers aiming to improve psychological well-being in this vulnerable population.

Although motivational psychological nursing shows promise in the reduction of anxiety and depression, the present study encountered limitations. The use of retrospective design, despite matching baseline characteristics well, inherently limited causal claims. The lack of control for confounding variables, such as concurrent therapies and socioeconomic factors, might have influenced the results. The psychological measures rely heavily on self-reported scales, which possibly introduced response bias. Moreover, this research was conducted at a single institution, which may not fully represent the broader population. While employing objective measures of psychological and physical health, future research should incorporate longitudinal, randomized controlled trials using randomization and blinding to validate and extend these findings.

This study elucidated the potential of motivational psychological nursing as a viable intervention to alleviate anxiety and depression in patients with complex chronic health conditions, such as rheumatism and immunologic diseases com

| 1. | Ibos KE, Bodnár É, Dinh H, Kis M, Márványkövi F, Kovács ZZA, Siska A, Földesi I, Galla Z, Monostori P, Szatmári I, Simon P, Sárközy M, Csabafi K. Chronic kidney disease may evoke anxiety by altering CRH expression in the amygdala and tryptophan metabolism in rats. Pflugers Arch. 2024;476:179-196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kandemir I, Gudek K, Sahin AY, Aksakal MT, Kucuk E, Yildirim ZNY, Yilmaz A, Nayir A, Bas F. Association of problems, coping styles, and preferred online activity with depression, anxiety, and other psychological disorders in Turkish adolescents diagnosed with chronic kidney disease. Pediatr Nephrol. 2024;39:2779-2788. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Yarlioglu AM, Oguz EG, Gundogmus AG, Atilgan KG, Sahin H, Ayli MD. The relationship between depression, anxiety, quality of life levels, and the chronic kidney disease stage in the autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Int Urol Nephrol. 2023;55:983-992. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Vovlianou S, Koutlas V, Papoulidou F, Tatsis V, Milionis H, Skapinakis P, Dounousi E. Burden, depression and anxiety effects on family caregivers of patients with chronic kidney disease in Greece: a comparative study between dialysis modalities and kidney transplantation. Int Urol Nephrol. 2023;55:1619-1628. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Shi Y, Zhang H, Nie Z, Fu Y. Quality of life, anxiety and depression symptoms in living related kidney donors: a crosssectional study. Int Urol Nephrol. 2023;55:2335-2343. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Courtillié E, Fromage B, Augusto JF, Saulnier P, Subra JF, Bonnaud-Antignac A. Waiting for a kidney transplant, a source of unavoidable but reversible anxiety: a prospective pilot study investigating a psychological intervention. J Nephrol. 2023;36:841-849. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Seman A, Picillo R. Waiting for a kidney transplant: less anxiety, more longing. J Nephrol. 2023;36:935-936. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Chilcot J, Pearce CJ, Hall N, Rehman Z, Norton S, Griffiths S, Hudson JL, Mackintosh L, Busby A, Wellsted D, Jones J, Sharma S, Ormandy P, Palmer N, Schmill P, Da Silva-Gane M, Morgan N, Poulikakos D, Veighey K, Robertson S, Elias R, Farrington K. Depression and anxiety in people with kidney disease: understanding symptom variability, patient experience and preferences for mental health support. J Nephrol. 2025;38:675-686. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Hassan F, Doğan N. Evaluation of body image perception, pain, fatigue and anxiety levels of individuals on hemodialysis and waiting for kidney transplantation and individuals with kidney transplantation. Actas Urol Esp (Engl Ed). 2025;49:501707. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Huang B, Huang Z, Wang H, Zhu G, Liao H, Wang Z, Yang B, Ran J. High urea induces anxiety disorders associated with chronic kidney disease by promoting abnormal proliferation of OPC in amygdala. Eur J Pharmacol. 2023;957:175905. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Gao M, Liu M, Zhang Y, Tang L, Chen H, Zhu Z. The impact of anxiety on the risk of kidney stone disease: Insights into eGFR-mediated effects. J Affect Disord. 2024;364:125-131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Temür BN, Aksoy N. Factors Affecting Anxiety of Kidney Transplant Recipients According to Donor Type: A Descriptive Study. J Perianesth Nurs. 2023;38:118-126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Firestein GS, Budd RC, Gabriel SE, McInnes IB, O'Dell JR. Kelley and Firestein's textbook of rheumatology. Philadelphia, PA, United States: Elsevier, 2016. |

| 14. | Yu AS, Chertow GM, Luyckx V, Marsden PA, Skorecki K, Taal MW. Brenner and Rector's the kidney. Philadelphia, PA, United States: Elsevier, 2020. |

| 15. | Yu Y, Yang JP, Shiu CS, Simoni JM, Xiao S, Chen WT, Rao D, Wang M. Psychometric testing of the Chinese version of the Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey among people living with HIV/AIDS in China. Appl Nurs Res. 2015;28:328-333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Zheng YP, Wei LA, Goa LG, Zhang GC, Wong CG. Applicability of the Chinese Beck Depression Inventory. Compr Psychiatry. 1988;29:484-489. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Ramdan IM. Reliability and Validity Test of the Indonesian Version of the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A) to Measure Work-related Stress in Nursing. J Ners. 2019;14:33. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kaneda Y. Usefulness of the zung self-rating depression scale for schizophrenics. J Med Invest. 1999;46:75-78. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Wang XM, Ma HY, Zhong J, Huang XJ, Yang CJ, Sheng DF, Xu MZ. A Chinese adaptation of six items, self-report Hamilton Depression Scale: Factor structure and psychometric properties. Asian J Psychiatr. 2022;73:103104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Jiang L, Wang Y, Zhang Y, Li R, Wu H, Li C, Wu Y, Tao Q. The Reliability and Validity of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) for Chinese University Students. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:315. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 180] [Article Influence: 25.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Zeng G, Fung S, Li J, Hussain N, Yu P. Evaluating the psychometric properties and factor structure of the general self-efficacy scale in China. Curr Psychol. 2022;41:3970-3980. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Wang R, Wu C, Zhao Y, Yan X, Ma X, Wu M, Liu W, Gu Z, Zhao J, He J. Health related quality of life measured by SF-36: a population-based study in Shanghai, China. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:292. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Berlim MT, Pavanello DP, Caldieraro MA, Fleck MP. Reliability and validity of the WHOQOL BREF in a sample of Brazilian outpatients with major depression. Qual Life Res. 2005;14:561-564. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Wu SH, Liang HW, Hou WH. Reliability and validity of the Taiwan Chinese version of the Foot Function Index. J Formos Med Assoc. 2008;107:111-118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Wolfe F, Michaud K, Pincus T. Development and validation of the health assessment questionnaire II: a revised version of the health assessment questionnaire. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:3296-3305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 196] [Cited by in RCA: 202] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Huang X, Liang J, Zhang J, Fu J, Xie W, Zheng F. Association of cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic health and social connection with the risk of depression and anxiety. Psychol Med. 2024;54:1-9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Han B, Wang L, Zhang Y, Gu L, Yuan W, Cao W. Baseline anxiety disorders are associated with progression of diabetic kidney disease in type 2 diabetes. Ren Fail. 2023;45:2159431. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Song Q, Yuan T, Xu Z, Xu Y, Wu M, Hou J, Fei J, Mei S. Post-traumatic growth, depression and anxiety among hemodialysis patients: a latent profile analysis. Psychol Health Med. 2025;1-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Giordano F, Mitrotti A, Losurdo A, Esposito F, Granata A, Pesino A, Rossini M, Natale P, Dileo V, Fiorentino M, Gesualdo L. Effect of music therapy intervention on anxiety and pain during percutaneous renal biopsy: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Kidney J. 2023;16:2721-2727. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Huang J, Mao Y, Zhao X, Liu Q, Zheng T. Association of anxiety, depression symptoms and sleep quality with chronic kidney disease among older Chinese. Medicine (Baltimore). 2023;102:e35812. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Golenia A, Olejnik P, Żołek N, Wojtaszek E, Małyszko J. Cognitive Impairment and Anxiety Are Prevalent in Kidney Transplant Recipients. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2023;48:587-595. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Jaberi M, Mohammadi TK, Adib M, Maroufizadeh S, Ashrafi S. The Relationship of Death Anxiety With Quality of Life and Social Support in Hemodialysis Patients. Omega (Westport). 2025;90:1894-1908. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Qin C, Wu Y, Zou Y, Zhao Y, Kang D, Liu F. Associations between depressive and anxiety symptoms and incident kidney failure in patients with diabetic nephropathy. BMC Nephrol. 2025;26:54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Soliva MS, Carrascosa López C, Rico Salvador I, Ramón RO, Coca JV, Maset RG, Testal AG. The effectiveness of live music in reducing anxiety and depression among patients undergoing haemodialysis. A randomised controlled pilot study. PLoS One. 2024;19:e0307661. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Warli SM, Alamsyah MT, Nasution AT, Kadar DD, Siregar GP, Prapiska FF. The Assessment of Male Erectile Dysfunction Characteristics in Patients Undergoing Continuous Ambulatory Peritoneal Dialysis and Hemodialysis Using the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF-5) Combined with Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scales. Int J Nephrol Renovasc Dis. 2023;16:155-161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Kose S, Mohamed NA. The Interplay of Anxiety, Depression, Sleep Quality, and Socioeconomic Factors in Somali Hemodialysis Patients. Brain Sci. 2024;14:144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Saguban R, AlAbd AMA, Rondilla E, Buta J, Marzouk SA, Maestrado R, Sankarapandian C, Alkubati SA, Mostoles R Jr, Alshammari SA, Alrashidi MS, Gonzales A, Lagura GA, Gonzales F. Investigating the Interplay Between Sleep, Anxiety, and Depression in Chronic Kidney Disease Patients: Implications for Mental Health. Healthcare (Basel). 2025;13:294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | González-Flores CJ, Garcia-Garcia G, Lerma C, Guzmán-Saldaña RME, Lerma A. Effect of Cognitive Behavioral Intervention Combined with the Resilience Model to Decrease Depression and Anxiety Symptoms and Increase the Quality of Life in ESRD Patients Treated with Hemodialysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20:5981. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/