Published online Oct 19, 2025. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v15.i10.109466

Revised: July 3, 2025

Accepted: July 30, 2025

Published online: October 19, 2025

Processing time: 113 Days and 0.7 Hours

This minireview focuses on psychological distress and treatment adherence-issues in patients with chronic hepatitis B (CHB). It begins by discussing the epide

Core Tip: Patients with chronic hepatitis B (CHB) often experience psychological distress, including anxiety, depression, and stigma, which significantly impairs their treatment adherence. This minireview synthesizes recent evidence on the epidemiology and psychosocial challenges faced by CHB patients and proposes a comprehensive, biopsychosocial intervention framework. The authors highlight integrated nursing strategies, including cognitive-behavioral therapy, social support systems, digital health tools, and culturally adapted care models, aimed at improving mental health outcomes and long-term adherence among CHB patients. These insights offer clinical guidance for multidisciplinary teams in hepatology and psychiatry.

- Citation: Dong L. Psychological distress and treatment adherence-challenges of patients with chronic hepatitis B: Risk factors and integrated nursing strategies. World J Psychiatry 2025; 15(10): 109466

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v15/i10/109466.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v15.i10.109466

Chronic hepatitis B (CHB) is a global health concern affecting hundreds of millions of people[1]. Worldwide, 257-291 million individuals are infected with CHB virus (hepatitis B virus, HBV), with an annual death toll of 1.1 million due to CHB-related complications[2]. The prevalence of CHB varies significantly across regions. As an example. Greece, a country with a moderate CHB prevalence, has experienced a decline in HBV infection rates over the past decade owing to vaccination and improved socioeconomic conditions. However, large-scale immigration has substantially altered epidemiological profiles. A national multicenter study from to 1997-2006 revealed that immigrants accounted for 18.6% of the total study population, with the highest proportion in Albania (71.0%), and immigrant children accounted for 56.6% of all children studied[3]. In the United States, an estimated 1.59 million people (range 1.25-2.49 million) are chronically infected with HBV. The disease burden remains significant, despite the availability of vaccination, screening, and treatment resources[1]. In Taiwan province of China, the prevalence of CHB increased from 1.13% to 2.43% between 2010-2019, with the highest prevalence in the 55-64 and 45-54 age groups, and a higher rate in males. Moreover, increased disease severity has led to a higher utilization of medical resources, increasing the economic burden[4]. In South Korea, the 7-year prevalence rates of CHB and HBV/hepatitis delta virus coinfection are 0.9% and 0.0024%, respectively, with a higher prevalence in the 45-54 age group and among males. The 5-year cumulative incidence showed a high proportion of complications and substantial medical expenses[5].

CHB not only significantly affects individual health, leading to severe complications such as liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma, but also imposes a heavy economic burden[6]. Studies in Beijing and Guangzhou of China indicated that CHB-related diseases incur high economic costs for patients and their families, with medical expenses increasing as the disease progresses[7]. Research in Japan also showed that the average total medical cost for patients with CHB is high, with management costs for liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma being the highest[8]. These data clearly demonstrate the severe epidemiological status and heavy disease burden of CHB, which require effective interventions.

Psychological distress is closely associated with treatment adherence, a phenomenon observed in various diseases. In patients with tuberculosis, 22% experience severe psychological distress [Kessler 10 Psychological Distress Scale (K-10) score ≥ 30], and psychological distress is significantly associated with nonadherence to treatment. Health literacy levels, psychological-distress scores, and alcohol abuse were independent factors influencing treatment adherence. Among patients with tuberculosis confirmed by bacterial culture, those with a K-10 score ≥ 30 have a higher risk of nonadherence to treatment [odds ratio (OR) = 2.290, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.033-5.126; P = 0.0416][9].

Psychological distress is also significantly associated with blood-pressure control and treatment adherence in patients with hypertension. Studies showed that the psychological distress scores of female patients with uncontrolled hy

In patients with coronary heart disease, depression, anxiety, and perceived stress, or any changes to these conditions, can affect treatment adherence. Baseline depression and its changes over time significantly predict declines in medication adherence and specific treatment adherence (β = 0.15-0.20, P < 0.05)[11]. Psychological distress may affect treatment adherence in patients with CHB. As a chronic disease that requires long-term treatment, it poses a significant psychological burden on patients by increasing psychological distress. This distress can lead to decreased confidence in treatment and self-management ability, thereby affecting treatment adherence. Understanding this relationship is crucial for developing targeted interventions to improve treatment outcomes in patients with CHB.

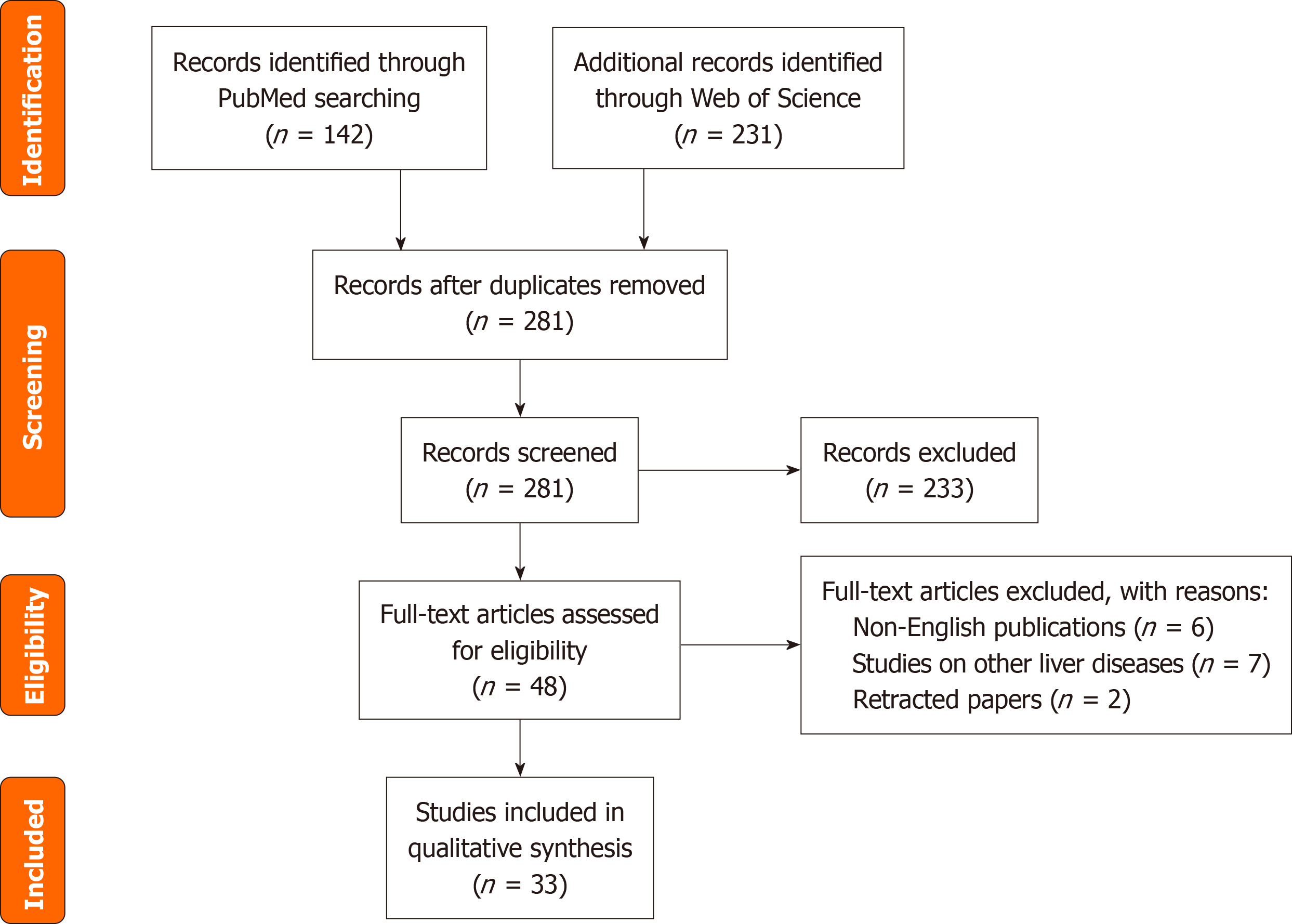

This study adopts a systematic narrative review approach. Literature searches were conducted across PubMed and Web of Science databases from January 2011 to December 2024, using Medical Subject Headings terms: (“chronic hepatitis B” OR “CHB”) AND (“psychological distress” OR “depression” OR “stigma”) AND (“treatment adherence” OR “medication compliance”) AND (“nursing interventions”).

Inclusion criteria: Studies on adult CHB patients (age ≥ 18 years); articles reporting primary data on psychological distress/adherence; and interventions with measurable outcomes (e.g., Hospital Anxiety and Disability Scale scores, adherence rates). Animal studies, editorials, non-English publications, and studies on acute hepatitis or other liver diseases were excluded. The initial searches identified 1372 records. After removing duplicates (n = 316) and screening titles and abstracts (n = 896), 160 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility. In total, 78 studies met the inclusion criteria (Figure 1).

Patients with CHB often experience various psychological distresses, commonly manifesting as anxiety and depression. Studies indicate that psychological distress, including anxiety and depression, is prevalent among patients with chronic diseases and may affect quality of life and treatment outcomes[12]. Psychological distress is associated with cancer-specific mortality in patients with cancer. A study in Sweden involving 4245 patients with cervical cancer found that those with psychological distress exhibited an increased risk of cancer-specific death (hazard ratio = 1.33, 95%CI: 1.14-1.54)[13]. Owing to the chronic nature and infectivity of CHB, patients are prone to anxiety and depression, which negatively affects physical and mental well-being and treatment adherence.

Stigma, loneliness, and uncertainty about the prognosis are also important aspects of psychological distress in patients with CHB. Some feel shame due to the infectious nature of the disease, worry about discrimination, and experience stigma. This stigma may lead patients to conceal their condition or avoid social interactions, thereby exacerbating their loneliness. Furthermore, long treatment duration and uncertain outcomes may lead to prognosis-related concerns. A study conducted in Iran found that social stigmatization not only led to patients experiencing shame and discrimination, but also affected their mental health and social support systems[14]. Patients are often reluctant to disclose their conditions because of the fear of losing family and social support, which further exacerbates their sense of isolation and helplessness[15]. A study on patients with cancer reported that perceptions of disease control and curability were related to depression and anxiety. Those who believed that their disease was severe and difficult to cure were more likely to experience depression (OR = 6.93; P = 0.048)[16]. Similarly, patients with CHB may be psychologically burdened by an unknown prognosis, which in turn affects their mental state and treatment engagement.

Individual factors significantly influenced psychological distress in patients with CHB. Studies indicated that factors such as sex, age, and personality traits were associated with psychological distress. In patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), females and those reporting subjective cognitive difficulties post-infection had higher levels of psychological distress, while a high cognitive reserve served as a protective factor[17]. In the elderly, factors such as female gender, comorbidities, current smoking, insufficient sleep, rental housing, retirement, walking disabilities, and low household expenditures were independently associated with psychological distress, with walking disability showing the strongest association (OR = 2.69, 95%CI: 2.46-2.93)[18]. In patients with CHB, personality and coping styles may also affect the degree of psychological distress, with introverted and negatively-coping patients being at greater risk.

Social factors also play a significant role in psychological distress experienced by patients with CHB. Isolation and deficiencies in social support may also increase psychological distress. For example, social network factors, such as social isolation and social connections can mediate mental health and psychological distress, with social isolation indirectly affecting psychological distress (β = -0.0070, 95%CI: -0.0133 to -0.0023)[19]. Family support and community care within the social-support system can also influence psychological state. Patients lacking social support are more likely to ex

Disease cognition is another critical factor affecting psychological distress in patients with CHB. Patient understanding of CHB, including misconceptions, affects not only quality of life but also psychological state. If patients lack accurate knowledge of disease transmission routes and treatment methods, they may develop excessive fear and anxiety. Cognitive impairment may further intensify patient uncertainty regarding the prognosis, thereby affecting treatment adherence[20]. Studies indicated that psychological distress, including depression and anxiety, was prevalent among patients with CHB who were receiving oral antiviral therapy and negatively affected their self-management behaviors[21]. The social stigma associated with hepatitis B is also considered a significant factor affecting treatment adherence. Previous studies showed that perceived HBV stigma was significantly associated with adherence to antiviral medication. Multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed that the adherence risk of patients in the moderate stigma group (scores 3-5) was 53% lower than that of patients in the low stigma group (scores 0-2) [adjusted OR (aOR) = 0.47, 95%CI: 0.24-0.91, P < 0.05], whereas the adherence risk in the high stigma group (scores ≥ 6) was not significantly different (aOR = 0.73, 95%CI: 0.38-1.39). Additionally, the average total stigma score was 5.38 ± 5.69 (range 0-24), with younger patients reporting higher stigma (r = -0.10, P = 0.058). The study also found that higher knowledge levels (aOR = 2.04, P < 0.05) and having a pharmacy plan (aOR = 1.94, P < 0.05) were protective factors against adherence risk. These results suggest that psychological and social factors (such as stigma) interact with structural factors (such as healthcare access) to influence patient treatment behaviors, highlighting the need for educational interventions and stigma reduction to improve CHB management[22]. Interventions targeting these psychological and social factors may help to enhance treatment adherence and overall health outcomes in patients with CHB.

Many indicators can predict the prognosis of CHB and related diseases such as liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma, including gallbladder thickness. However, patient adherence poses a challenge[23-25]. Nonadherence to antiviral treatment is a widespread issue in patients with CHB. In other disease treatments, such as desmopressin for primary nocturnal enuresis and inhaled corticosteroids/Long-acting β2-agonists for asthma, this has also been verified[26,27]. Nonadherence can lead to suboptimal virological responses and even increase the risk of viral breakthroughs[28]. This can also result in underestimated treatment efficacy, because many patients may interrupt or alter their treatment plans for various reasons during the treatment process[29]. Long-term, or even lifelong medication is required for patients with CHB, which poses a significant challenge to adherence.

Researchers have explored various interventions to improve adherence in patients with CHB. For example, a randomized controlled trial targeting Asian-American patients with CHB demonstrated that a multicomponent, culturally adapted intervention combining virtual patient education, personalized navigation support, and mobile health reminders significantly improved adherence to clinical follow-ups and laboratory monitoring. The study included 358 Chinese and Vietnamese patients, with the intervention group showing significantly higher clinical follow-up (86.2% vs 54.2%) and laboratory monitoring rates (79.0% vs 45.2%) over 12 months than the control group. The aORs for follow-up and monitoring were 7.35 and 6.60, respectively. This intervention, designed with community participation, addressed systemic barriers such as language obstacles, cultural cognition, and healthcare resource access by providing support[30].

Patient-level factors significantly affected treatment adherence in patients with CHB. Patient health beliefs, self-management abilities, and knowledge of medication influenced adherence. For instance, a study on general patients found that factors such as patient attitudes toward drug therapy and lifestyle habits were related to medication adherence. The desire to reduce medication use, irregular medications, and mealtimes reduced adherence[31]. If patients with CHB lacked sufficient awareness of disease severity and needed treatment, they might neglect the importance of timely medication administration. Additionally, differences in self-management abilities may lead to varying adherence levels. Patients with stronger self-management skills are more likely to take medications and attend regular follow-up visits.

Economic factors also influenced treatment adherence in patients with CHB. Treatment costs and financial burden affected patient adherence. For economically disadvantaged patients, long-term treatment expenses may become a heavy burden, preventing them from purchasing medication on time and thus affecting adherence. Research indicates that economic factors are a common cause of non-adherence to chronic disease treatment[32]. In CHB treatment, the costs of antiviral drugs and regular check-ups impose financial pressure. In regions with inadequate health insurance coverage, patients may discontinue treatment due to economic reasons.

Similarly, insufficient medical support may also affect treatment adherence. Communication between doctors and patients, access to medical services, and follow-up management also influence patient adherence. If doctors fail to adequately explain the treatment plans and potential side effects, patients may avoid taking medications because of concerns. A study on community case-management services found that factors such as patient contact time with case managers and the support and advocacy they received affected patient satisfaction and treatment adherence[33]. For CHB treatment, healthcare teams should enhance communication with patients, provide convenient medical services, and establish robust follow-up management strategies to improve patient adherence.

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) plays a significant role in alleviating psychological distress in patients with CHB. Based on the cognitive-behavioral model, CBT can change cognitive and behavioral patterns to relieve anxiety, depression, and other emotional issues. For example, in treating patients with depression, CBT and acceptance and commitment therapy significantly reduced depressive symptoms (d = -1.26 to -1.60) and improved quality of life (d = 0.91 to -1.28), with no significant differences in efficacy between the two therapies. Dysfunctional attitudes and decentering mediated the effects of both therapies on depressive symptoms in both therapies[34]. Applying CBT to patients with CHB may help identify and correct negative cognitions about the disease and change maladaptive behavioral habits, thereby reducing psychological distress and improving treatment adherence.

Tracking nursing models are also effective in providing psychological support for patients with CHB. Through regular follow-ups, healthcare professionals can promptly understand patient psychological states, treatment progress, and any issues that may be encountered while offering targeted psychological support and guidance. For example, combining tracking nursing with CBT in patients may ensure that they continue to apply their learned cognitive and behavioral skills, thereby consolidating treatment outcomes. A randomized controlled trial by Schienle et al[35] in patients with depression showed that a tracking nursing model combining standard CBT with a placebo intervention significantly improved treatment adherence and long-term prognosis. The study included 82 patients with mild-to-moderate depression who were randomly divided into a CBT group (n = 40) and a CBT + placebo group (n = 42). The latter received a placebo (labeled as “golden root oil” to enhance psychological suggestion) daily for 4 weeks of treatment and un

Comprehensive nursing interventions may effectively boost self-efficacy in patients with CHB infection. Based on the Pender’s Health Promotion Model, interventions involving six 60-minute sessions for elderly patients and two additional sessions for their families significantly improved self-efficacy in the elderly. Post-intervention, the self-efficacy scores of the intervention group (68.87 ± 10.27) were significantly higher than those of the control group (54.96 ± 5.67; P < 0.01)[36]. Comprehensive nursing interventions for patients with CHB may include health education, psychological support, and lifestyle guidance to help them understand the disease, master self-care skills, and enhance confidence in disease treatment, thereby improving self-efficacy.

Pong et al[37] explored the application of digital-health technologies to chronic disease management. They pointed out that digital-health tools are used in chronic liver disease management in the following ways. Mobile health provides medication reminders, symptom monitoring, and laboratory result tracking (e.g., liver function and viral load) via smartphone applications, helping patients take antiviral medications regularly. Telehealth supports remote consultations and video follow-ups, reducing the frequency of hospital visits for patients and a similar model can be used for regular follow-ups with liver disease specialists. Wearable devices (wearables) monitor physiological indicators related to liver disease (e.g., jaundice or ascites symptoms) or detect liver function abnormalities through biosensors.

Kazankov et al[38] assessed the application of the digital-health solution CirrhoCare and standard community care in the home management of patients with liver cirrhosis. Data were collected daily using smartwatches, bluetooth blood-pressure monitors, bioimpedance scales, and the CyberLiver Animal Recognition Test cognitive test application. Health status and diet, fluid, and alcohol intake were autonomously reported via this application. All data were encrypted and transmitted to a cloud platform, presented in real time on a clinical doctor dashboard, and triggered alarm thresholds (e.g., systolic blood pressure < 95 mmHg, heart rate > 90 beats/minute, and failed cognitive tests). Doctors provided guidance on medication use and other medical measures via two-way communication (phone or short message service), such as adjusting diuretic/Laxative doses, optimizing fluid intake, or urgent referrals. After 10 weeks of follow-up, results showed that 85% of patients in the intervention group had good adherence (≥ 4 measurements/week), with fewer hospitalizations (8 times vs 13 times), shorter hospital stays (median 5 days vs 7 days), and fewer unplanned paracenteses (1 times vs 6 times) when compared with the control group. In total, 85% of alarm interventions (e.g., dehydration, ascites, and hepatic encephalopathy) effectively prevented disease progression, and patient model for end-stage liver disease with sodium and chronic liver failure-consortium acute decompensation scores improved. These results indicated that integrated real-time physiological monitoring and telehealth management could optimize community care for patients with liver cirrhosis, reduce rehospitalization risks, and improve disease prognosis. Despite the convenience and potential benefits of digital interventions, challenges remain to their widespread adoption. Some patients, particularly those who are older or have lower educational levels, may struggle with digital technology. The personalization and interactivity of digital interventions are often insufficient to meet the diverse needs of patients with CHB. Moreover, the long-term effectiveness and safety of digital interventions require more rigorous evaluation to ensure reliability.

The family-community-hospital linkage model provides comprehensive social support for patients with CHB. Families are the most direct sources of patient support. The care, support, and supervision of family members may help patients adhere to treatments. Family support not only directly affects patient-treatment behaviors but may also enhance adherence by increasing social belongingness[39]. Communities may offer health education and rehabilitation guidance to strengthen patient understanding of disease and enhance self-management abilities. Hospitals provide professional medical services and guidance. For example, the Community Care Connection Project reduced hospitalization, emer

Nurse-led extended care plays a key role in optimizing the social support system for patients with CHB. Nurses may provide personalized nursing services and psychological support through home visits and telephone follow-ups. A study in Australia showed that community-clinic nurses were responsible for assessing, managing, educating, and triaging patients with CHB, and developing care plans for general practitioners following internationally and nationally recognized CHB guidelines. The results demonstrated high patient satisfaction with the clinic and a willingness to participate in future CHB care. These findings indicated that nurse-led community HBV clinics are feasible, acceptable, and safe, with nurses playing a core role in triage, case management, and general-practitioner support. This effectively improved patient access to best-practice care and enhanced disease-management abilities, thereby optimizing the social support system[42].

Personalized medical care and technological innovations have provided new opportunities for the treatment of CHB. Research on gene regulatory mechanisms (e.g., microRNA-124 regulation of aging-related genes) offers new ideas for targeted HBV-infection treatment[43]. The development of precision medicine has enabled CHB treatment to be tailored to the genetic characteristics and disease-progression stages of patients. The study of diagnostic and prognostic markers (e.g., serum markers and genetic polymorphisms) is key for optimizing personalized medical care[44]. For example, advances in gene-editing technologies provided potential solutions for treating CHB-related genetic diseases and it may be possible to cure CHB[45]. Additionally, the analysis of genetic polymorphisms in patients may predict drug responses, help select the most appropriate treatment drugs and dosages, improve treatment efficacy, and reduce adverse drug reactions.

Information technology also plays a significant role in personalized medical care for patients with CHB. Medical information systems can integrate patient clinical and genetic data and provide comprehensive references for doctors to develop personalized treatment plans. For instance, clinical decision support systems can combine genomic knowledge with patient information to offer treatment suggestions at the point of care[46]. Digital platforms allow patients to communicate remotely with doctors to provide timely treatment advice. Doctors can monitor changes in patient conditions in real time and adjust treatment plans accordingly to achieve personalized medical care. Furthermore, big data and artificial intelligence technologies could be used to analyze large amounts of CHB patient data to identify potential treatment targets and patterns, thereby advancing personalized CHB medical care.

Nurse-led interventions, which play a significant role in the care of patients with CHB, have certain limitations. The knowledge and skill levels of nurses may vary, affecting intervention outcomes. Nurses may differ in their understanding of CHB and psychological intervention techniques, leading to an inconsistent quality of nursing services. A heavy workload may prevent nurses from providing sufficient time and attention for in-depth interventions for each patient. A study on nurse-led digital-health interventions found that, while the intervention had some effect on blood-pressure control and self-management in hypertensive patients, limited nursing resources meant that some patients did not receive adequate attention or guidance[47]. In CHB patient care, insufficient nurse staffing may hinder timely patient support and affect the comprehensiveness and continuity of interventions.

The effectiveness of digital interventions in CHB patients requires further improvement. Although digital health tools offer convenient services, some patients, particularly the elderly and those with low educational levels, may have limited acceptance of digital technologies and face operational difficulties that restrict the widespread adoption of digital interventions. Additionally, the content and format of digital interventions may lack personalization and fail to meet the diverse needs of patients. For example, disease-knowledge content in some digital-health applications may be overly technical and difficult for patients to understand, or lack interactive features to promptly address patient questions. The long-term effects and safety of digital interventions require further investigation to ensure their effectiveness and reliability in CHB patient care.

A need for more comparative studies on CHB treatment is evident. This includes studies comparing the effectiveness of CBT with mindfulness-based interventions to determine the most suitable approach for managing psychological distress in patients with CHB. Future research should explore the long-term impact of digital-health interventions and integrate them into clinical practice. The development of culturally-adapted interventions for diverse patient populations is a critical area requiring further investigation.

Development of interdisciplinary collaborative models is a key direction for future CHB research. The treatment and care of patients with CHB involves multiple disciplines, such as medicine, psychology, and sociology. Interdisciplinary collaboration models may integrate the strengths of these fields to provide more comprehensive and personalized services. As an example, medical professionals could offer disease diagnoses and treatment plans, psychologists could conduct assessments and interventions, and sociologists could assist in addressing social support issues. Treatment outcomes and quality of life could be improved by establishing interdisciplinary teams and strengthening communication and collaboration among disciplines. Research indicates that interdisciplinary collaboration offers significant advantages in chronic-disease management and meets patient multifaceted needs[48]. Future efforts should explore suitable interdisciplinary collaboration models for CHB patients, clarify the roles and processes of each discipline, and enhance collaboration efficiency.

Exploring culturally-adapted interventions is crucial for improving treatment outcomes in patients with CHB. Patients from different cultural backgrounds may have different perceptions, attitudes, and coping strategies. Culturally-adapted interventions could tailor the intervention content and methods to patient cultural characteristics, thereby improving acceptance and adherence. For example, in some cultures, patients may prefer traditional medicine as an adjunct to other treatments that may be appropriately incorporated into interventions. A study on mental-health interventions found that culturally-adapted interventions enhanced treatment outcomes in patients from diverse cultural backgrounds, with a positive correlation between cultural adaptation and intervention effectiveness (P = 0.04)[49]. For CHB, it is essential to understand characteristics from different cultural backgrounds and develop culturally-adapted psychological interventions and health-education programs to better meet patient needs and improve treatment outcomes.

Policy-level efforts to promote health-insurance coverage for psychological intervention costs are crucial for improving the mental health of patients with CHB. Patients with CHB often experience psychological distress, and psychological interventions are essential for alleviating this distress and improving treatment adherence. However, limited health-insurance coverage for psychological interventions may prevent some patients from accessing psychological treatment, owing to financial constraints. Policymakers should prioritize the mental health of patients with CHB and reform health-insurance policies to include psychological intervention costs in reimbursements, reduce patient financial burdens, and increase the accessibility of psychological interventions. Additionally, governments should encourage social forces to participate in psychological support services for CHB patients by establishing special funds for related research and service projects, thereby promoting mental health.

Juon et al[22] found that perceived HBV stigma was linked to lower adherence to antiviral medication, whereas older patients, those with a deep knowledge of CHB complications, and those with a pharmacy plan tended to have better adherence. This study underscored the importance of personal (such as knowledge and stigma) and healthcare factors in medication adherence. These results suggest that future studies should focus on educational interventions that target personal factors to boost adherence among Korean-American patients with CHB. The study also showed that a good understanding of CHB is key to ensuring adherence, and that patients with high perceived HBV stigma had significantly lower adherence to antiviral medications. Pharmacy plans are another important factor enhancing patient adherence.

Significant differences in the manifestations of psychological distress were found among patients with CHB in high- and low-incidence areas. In high-incidence areas, patients downplayed the severity of the disease due to its prevalence, but at the same time, they faced greater psychological pressure due to the influence of socioeconomic factors. For example, in Vietnam, a country with a high incidence of hepatitis B infection, older patients, those with lower income levels, and those living with a spouse or partner were more likely to experience depressive symptoms. In addition, physical health problems and lower health-related quality of life were associated with an increased risk of depression[50]. In contrast, in low-incidence areas such as Australia, the psychological distress of patients with CHB was more related to fear of the disease and social stigmatization. Research found that many patients were worried about developing liver cancer and transmitting the virus to others, and some were reluctant to discuss their conditions with others. Patients with lower educational levels were more likely to experience fear and were unwilling to communicate with others, while those with higher English proficiency were more likely to change their lifestyle because of hepatitis B[51]. Therefore, in dif

Psychological distress and treatment adherence are related in patients with CHB. This forms a vicious cycle that affects disease prognosis and quality of life. Psychological distress (e.g., anxiety, depression, stigma, and uncertainty about prognosis) may weaken patient confidence in treatment and self-management abilities, leading to decreased adherence. For example, studies on patients with tuberculosis and hypertension showed that psychological distress not only directly reduced medication adherence (e.g., patients with a K-10 score ≥ 30 had an increased risk of nonadherence by 2.29 times) but also impaired patient healthy decision-making abilities through negative emotions. Nonadherence exacerbated patient concerns about disease progression and further induced or worsened psychological distress. This bidirectional relationship is particularly prominent in patients with CHB, for whom long-term or lifelong treatments are often nece

At a biomedical level, precision medicine and technological innovations in CHB management are warranted. For instance, gene-editing technologies offer potential pathways for curing HBV infection, whereas digital tools (such as medication-reminder apps and remote-monitoring platforms) can track patient adherence in real time and dynamically adjust treatment plans. Psychologically, CBT and acceptance and commitment therapy were effective in alleviating anxiety and depression (effect sizes d = -1.26 to -1.60). Combining these therapies with nurse-led tracking-care models may enhance patient adaptive cognition of the disease. The optimization of social-support systems is critical. The family-community-hospital linkage model enhances patient social belonging and economic assistance (e.g., community-care connection programs may reduce hospitalization rates by 30%), alleviating isolation and treatment pressures. Furthermore, personalized medicine must consider patient cultural backgrounds. For example, designing culturally-adapted interventions for immigrant groups or high-risk populations in specific regions could improve acceptance of health education.

Current research on psychological distress and treatment adherence in CHB patients has many limitations. Most trials are single-center with small sample sizes (n < 200), and there’s a lack of in-depth analysis on high-risk groups like immigrants and the low-income. Follow-up periods are usually short (≤ 6 months), making it hard to assess the long-term effects of interventions and their real impact on long-term liver disease prognosis. Measurement tools are too subjective (e.g., Morisky Medication Adherence Scale-8, Hospital Anxiety and Disability Scale scales), with not enough objective adherence verification like drug-concentration monitoring or electronic pill counts. There’s weak cultural adaptation and technological generalizability. The different psychological intervention needs of patients in high-prevalence areas (where economic stress is the main issue) and low-prevalence areas (where stigma is the main issue) aren’t distinguished. Also, digital health tools (e.g., remote monitoring apps) are hard for the elderly and less educated to use. And short-term validation (e.g., 10 weeks) can’t prove their sustainability.

Future research should focus on integrating technological innovations into humanistic care. At the technological level, the development of intelligent full-process management platforms that integrate electronic health records, artificial intelligence-aided decision-making, and self-reported patient data may enable real-time early warnings and precise interventions for treatment adherence. The construction of interdisciplinary collaborative models is crucial and requires joint efforts from experts in medicine, psychology, sociology, and other fields to develop comprehensive-care plans that cover disease management, psychological support, and social-resource integration. At the policy level, promoting health-insurance coverage for psychological-intervention costs (e.g., including CBT in reimbursements) and establishing special funds to support social-service projects may significantly enhance intervention accessibility. Additionally, long-term research is needed, particularly regarding the sustainability of digital-health tools (e.g., addressing technical-usage barriers in elderly patients) and the universal applicability of culturally-adapted interventions. In summary, CHB mana

| 1. | Lim JK, Nguyen MH, Kim WR, Gish R, Perumalswami P, Jacobson IM. Prevalence of Chronic Hepatitis B Virus Infection in the United States. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115:1429-1438. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 20.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | World Health Organization. Global hepatitis report 2024: action for access in low- and middle-income countries. April 9, 2024. [cited 5 May 2025]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240091672. |

| 3. | Raptopoulou M, Papatheodoridis G, Antoniou A, Ketikoglou J, Tzourmakliotis D, Vasiliadis T, Manolaki N, Nikolopoulou G, Manesis E, Pierroutsakos I. Epidemiology, course and disease burden of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. HEPNET study for chronic hepatitis B: a multicentre Greek study. J Viral Hepat. 2009;16:195-202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Chien HT, Su TH, Huang H, Chiang CL, Lin FJ. Real-world epidemiology, treatment patterns and disease burden of patients diagnosed with chronic hepatitis B in Taiwan. Liver Int. 2023;43:2404-2414. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Cho Y, Park S, Park S, Choi W, Kim B, Han H. Real-World Epidemiology, Treatment Patterns, and Disease Burden of Chronic Hepatitis B and HDV Co-Infection in South Korea. Infect Dis Ther. 2023;12:2387-2403. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | I Rigopoulou E, Bakarozi M, Dimas I, Galanis K, Lygoura V, K Gatselis N, Koulentaki M, N Dalekos G. Total and individual PBC-40 scores are reliable for the assessment of health-related quality of life in Greek patients with primary biliary cholangitis. J Transl Int Med. 2023;11:246-254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Hu M, Chen W. Assessment of total economic burden of chronic hepatitis B (CHB)-related diseases in Beijing and Guangzhou, China. Value Health. 2009;12 Suppl 3:S89-S92. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Umemura T, Wattanakamolkul K, Nakayama Y, Takahashi Y, Sbarigia U, KyungHwa L, Villasis-Keever A, Furegato M, Gautier L, Nowacki G, Azzi J, Wu DB. Real-World Epidemiology, Clinical and Economic Burden of Chronic Hepatitis B in Japan: A Retrospective Study Using JMDC Claims Database. Infect Dis Ther. 2023;12:1337-1349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Theron G, Peter J, Zijenah L, Chanda D, Mangu C, Clowes P, Rachow A, Lesosky M, Hoelscher M, Pym A, Mwaba P, Mason P, Naidoo P, Pooran A, Sohn H, Pai M, Stein DJ, Dheda K. Psychological distress and its relationship with non-adherence to TB treatment: a multicentre study. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15:253. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Eghbali M, Akbari M, Seify K, Fakhrolmobasheri M, Heidarpour M, Roohafza H, Afzali M, Mostafavi-Esfahani FS, Karimian P, Sepehr A, Shafie D, Khosravi A. Evaluation of Psychological Distress, Self-Care, and Medication Adherence in Association with Hypertension Control. Int J Hypertens. 2022;2022:7802792. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Fan Y, Shen BJ, Tay HY. Depression, anxiety, perceived stress, and their changes predicted medical adherence over 9 months among patients with coronary heart disease. Br J Health Psychol. 2021;26:748-766. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kalu K, Shah GH, Ayangunna E, Shah B, Marshall N. The Role of Social Determinants of Health in Self-Reported Psychological Distress among United States Adults Post-COVID-19 Pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2024;21:1219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Lu D, Andrae B, Valdimarsdóttir U, Sundström K, Fall K, Sparén P, Fang F. Psychologic Distress Is Associated with Cancer-Specific Mortality among Patients with Cervical Cancer. Cancer Res. 2019;79:3965-3972. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Valizadeh L, Zamanzadeh V, Bayani M, Zabihi A. The Social Stigma Experience in Patients With Hepatitis B Infection: A Qualitative Study. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2017;40:143-150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | HassanpourDehkordi A, Mohammadi N, NikbakhatNasrabadi A. Hepatitis-related stigma in chronic patients: A qualitative study. Appl Nurs Res. 2016;29:206-210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Mazzotti E, Sebastiani C, Marchetti P. Patient perception of disease control and psychological distress. Cancer Manag Res. 2012;4:335-340. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Devita M, Di Rosa E, Iannizzi P, Bianconi S, Contin SA, Tiriolo S, Ghisi M, Schiavo R, Bernardinello N, Cocconcelli E, Balestro E, Cattelan AM, Leoni D, Volpe B, Mapelli D. Risk and Protective Factors of Psychological Distress in Patients Who Recovered From COVID-19: The Role of Cognitive Reserve. Front Psychol. 2022;13:852218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Matsumura K, Kakiuchi Y, Tabuchi T, Takase T, Ueno M, Maruyama M, Mizutani K, Miyoshi T, Takahashi K, Nakazawa G. Risk factors related to psychological distress among elderly patients with cardiovascular disease. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2023;22:392-399. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Levula A, Harré M, Wilson A. Social network factors as mediators of mental health and psychological distress. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2017;63:235-243. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Khan Z, Saif A, Chaudhry N, Parveen A. Association of impaired cognitive function with balance confidence, static balance, dynamic balance, functional mobility, and risk of falls in older adults with depression. Aging Med (Milton). 2023;6:370-378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Kong LN, Yao Y, Li L, Zhao QH, Wang T, Li YL. Psychological distress and self-management behaviours among patients with chronic hepatitis B receiving oral antiviral therapy. J Adv Nurs. 2021;77:266-274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Juon HS, Yang D, Fang CX, Hann HW, Bae H, Chang M, Klassen AC. Perceived HBV-Related Stigma Is Associated With Lower Antiviral Medication Adherence in Patients With Chronic Hepatitis B. J Viral Hepat. 2025;32:e70010. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Huang DQ, Terrault NA, Tacke F, Gluud LL, Arrese M, Bugianesi E, Loomba R. Global epidemiology of cirrhosis - aetiology, trends and predictions. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;20:388-398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 194] [Cited by in RCA: 499] [Article Influence: 166.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Ding M, Yin Y, Wang X, Zhu M, Xu S, Wang L, Yi F, Abby Philips C, Gomes Romeiro F, Qi X. Associations of gallbladder and gallstone parameters with clinical outcomes in patients with cirrhosis. J Transl Int Med. 2024;12:308-316. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Lima C, Macedo E. Biomarkers in acute kidney injury and cirrhosis. J Transl Crit Care Med. 2024;6:e23-00014. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 26. | Van Herzeele C, Alova I, Evans J, Eggert P, Lottmann H, Nørgaard JP, Vande Walle J. Poor compliance with primary nocturnal enuresis therapy may contribute to insufficient desmopressin response. J Urol. 2009;182:2045-2049. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Darbà J, Ramírez G, Sicras A, García-Bujalance L, Torvinen S, Sánchez-de la Rosa R. Identification of factors involved in medication compliance: incorrect inhaler technique of asthma treatment leads to poor compliance. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2016;10:135-145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Hilleret MN, Larrat S, Stanke-Labesque F, Leroy V. Does adherence to hepatitis B antiviral treatment correlate with virological response and risk of breakthrough? J Hepatol. 2011;55:1468-1469; author reply 1469. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Leuchs AK, Zinserling J, Schlosser-Weber G, Berres M, Neuhäuser M, Benda N. Estimation of the treatment effect in the presence of non-compliance and missing data. Stat Med. 2014;33:193-208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Ma GX, Zhu L, Lu W, Handorf E, Tan Y, Yeh MC, Johnson C, Guerrier G, Nguyen MT. Improving Long-Term Adherence to Monitoring/Treatment in Underserved Asian Americans with Chronic Hepatitis B (CHB) through a Multicomponent Culturally Tailored Intervention: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Healthcare (Basel). 2022;10:1944. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Iino H, Kizaki H, Imai S, Hori S. Identifying the Relative Importance of Factors Influencing Medication Compliance in General Patients Using Regularized Logistic Regression and LightGBM: Web-Based Survey Analysis. JMIR Form Res. 2024;8:e65882. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Chiatti C, Bustacchini S, Furneri G, Mantovani L, Cristiani M, Misuraca C, Lattanzio F. The economic burden of inappropriate drug prescribing, lack of adherence and compliance, adverse drug events in older people: a systematic review. Drug Saf. 2012;35 Suppl 1:73-87. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Park CS, Park E. Factors Influencing Patient-Perceived Satisfaction With Community-Based Case Management Services. West J Nurs Res. 2018;40:1598-1613. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | A-Tjak JGL, Morina N, Topper M, Emmelkamp PMG. One year follow-up and mediation in cognitive behavioral therapy and acceptance and commitment therapy for adult depression. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21:41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Schienle A, Jurinec N. Combined Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy and Placebo Treatment for Patients with Depression: A Follow-Up Assessment. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2021;14:233-238. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Jalali A, Rajati F, Kazeminia M. Empowering the older people on self-care to improve self-efficacy based on Pender's health promotion model: A randomized controlled trial. Geriatr Nurs. 2025;61:574-579. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Pong C, Tseng RMWW, Tham YC, Lum E. Current Implementation of Digital Health in Chronic Disease Management: Scoping Review. J Med Internet Res. 2024;26:e53576. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Kazankov K, Novelli S, Chatterjee DA, Phillips A, Balaji A, Raja M, Foster G, Tripathi D, Boddu R, Kumar R, Jalan R, Mookerjee RP. Evaluation of CirrhoCare® - a digital health solution for home management of individuals with cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2023;78:123-132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Kim J, Lee H. Family support and dementia screening participation among older adults: Evidence from a South Korea fact-finding survey on the status of older adults. Aging Med (Milton). 2024;7:754-760. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Fisher EM, Akiya K, Wells A, Li Y, Peck C, Pagán JA. Aligning social and health care services: The case of Community Care Connections. Prev Med. 2021;143:106350. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Primignani M, Tosetti G, Ierardi AM. Approach to different thrombolysis techniques and timing of thrombolysis in the management of portal vein thrombosis in cirrhotic patients. J Transl Int Med. 2023;11:198-202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Pritchard-Jones J, Stevens C, McCaughan G, Strasser S. Feasibility, acceptability and safety of a nurse led hepatitis B clinic based in the community. Collegian. 2015;22:233-240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Dhar P, Moodithaya S, Patil P, Adithi K. A hypothesis: MiRNA-124 mediated regulation of sirtuin 1 and vitamin D receptor gene expression accelerates aging. Aging Med (Milton). 2024;7:320-327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Hudu SA, Shinkafi SH, Jimoh AO. A critical review of diagnostic and prognostic markers of chronic hepatitis B infection. Med Rev (2021). 2024;4:225-234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Koodamvetty A, Thangavel S. Advancing Precision Medicine: Recent Innovations in Gene Editing Technologies. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2025;12:e2410237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Carney PH. Information technology and precision medicine. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2014;30:124-129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Hwang M, Chang AK. The effect of nurse-led digital health interventions on blood pressure control for people with hypertension: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2023;55:1020-1035. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Fancourt D, Bhui K, Chatterjee H, Crawford P, Crossick G, DeNora T, South J. Social, cultural and community engagement and mental health: cross-disciplinary, co-produced research agenda. BJPsych Open. 2020;7:e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Harper Shehadeh M, Heim E, Chowdhary N, Maercker A, Albanese E. Cultural Adaptation of Minimally Guided Interventions for Common Mental Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JMIR Ment Health. 2016;3:e44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Vu TTM, Le TV, Dang AK, Nguyen LH, Nguyen BC, Tran BX, Latkin CA, Ho CSH, Ho RCM. Socioeconomic Vulnerability to Depressive Symptoms in Patients with Chronic Hepatitis B. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:255. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Hajarizadeh B, Richmond J, Ngo N, Lucke J, Wallace J. Hepatitis B-Related Concerns and Anxieties Among People With Chronic Hepatitis B in Australia. Hepat Mon. 2016;16:e35566. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/