Published online Oct 19, 2025. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v15.i10.108989

Revised: July 28, 2025

Accepted: August 18, 2025

Published online: October 19, 2025

Processing time: 91 Days and 0.5 Hours

Acute ischemic stroke (AIS) is a leading global cause of disability and mortality, with post-stroke cognitive impairment (PSCI) affecting 20%-40% of survivors. PSCI ranges from mild cognitive decline to dementia, severely hindering func

To explore the effects of nutritional intervention and social support on the cogni

A retrospective study was conducted. A total of 59 patients with acute cerebral infarction complicated by cognitive dysfunction from January 2023 to December 2023 were selected as the control group. Another 59 patients with the same condition were selected as the research group. The research group received sta

The Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) and Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) scores of the research group were higher than those of the control group, with statistically significant differences (P < 0.05). Pearson correlation analysis showed that increases in serum albumin (Alb), prealbumin (PAB), and hemoglobin (Hb) were all highly and significantly associated with improvements in MMSE and MoCA scores (P < 0.05). The Self-Rating Anxiety Scale and Self-Rating Depression Scale scores of the research group were lower than those of the control group, with statistically significant differences (P < 0.05). The scores of QoL dimensions in the research group were higher than those of the control group, with statistically significant differences (P < 0.05). The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index scores and total score of the research group were lower than those of the control group, with statistically significant differences (P < 0.05). The serum Alb, PAB, and Hb levels in the research group were higher than those of the control group, with statistically significant differences (P < 0.05). The Social Disability Screening Schedule scores of the research group were lower than those of the control group, with statistically significant differences (P < 0.05). The family satisfaction of the research group was significantly higher than that of the control group, with statistically significant differences (P < 0.05).

Nutritional intervention and social support significantly improved the cognitive function, psychological status, and QoL in patients with acute cerebral infarction complicated by cognitive dysfunction. These interventions reduced anxiety and depression symptoms, improved sleep and nutritional status, and enhanced the social adaptability of patients as well as family satisfaction.

Core Tip: This study investigated the effects of nutritional intervention and social support on patients with acute cerebral infarction (ACI) complicated by cognitive dysfunction. The results showed that the research group, receiving standardized nutritional support (e.g., dietary guidance and supplementation) and social support (e.g., psychological counseling and family involvement), demonstrated significant improvements in cognitive function (measured by Mini-Mental State Examination and Montreal Cognitive Assessment), psychological status (reduced Self-Rating Anxiety Scale and Self-Rating Depression Scale scores), sleep quality (Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index), and nutritional markers (albumin, prealbumin, hemoglobin) compared to the control group. These findings highlight the clinical value of integrated interventions for enhancing recovery in ACI patients.

- Citation: Gong J, Zheng J. Nutritional and social support enhance cognitive function in acute cerebral infarction patients. World J Psychiatry 2025; 15(10): 108989

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v15/i10/108989.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v15.i10.108989

Acute ischemic stroke is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, imposing a growing burden on public health systems[1]. Poststroke cognitive impairment (PSCI) affects approximately 20%-40% of survivors in Western cohorts aged ≥ 60 years[2] and up to 32% of Chinese patients aged ≥ 65 years at six months poststroke[3], with manifestations ranging from mild cognitive decline to severe dementia. PSCI not only hinders functional recovery and reduces quality of life (QoL), but also significantly increases healthcare costs through higher rates of stroke recurrence, prolonged hospitalization, and elevated mortality risk[4].

Appropriate nutritional support can supply the macronutrients and micronutrients required for neuronal repair, exert antioxidant and antiinflammatory effects, and mitigate ischemiainduced damage, thereby facilitating cognitive restoration[5,6]. Independently, social support interventions-encompassing structured psychological counseling, family education sessions, and peer engagement-have demonstrated efficacy in alleviating anxiety, depression, and enhancing overall wellbeing[7]. However, extant studies have largely evaluated these modalities in isolation, focusing predominantly on nutritional biomarkers or cognitive test scores, with limited assessment of psychological distress, sleep quality, QoL, or patient satisfaction. Moreover, recent systematic reviews highlight substantial heterogeneity in intervention protocols and a paucity of integrated approaches combining both nutritional and psychosocial elements[8,9].

To address these gaps and advance clinical nursing practice, the present study investigates the combined effects of a standardized enteral nutrition protocol and a structured social support program on cognitive function, mood, sleep quality, nutritional status, healthrelated QoL, and satisfaction among patients with acute cerebral infarction complicated by cognitive dysfunction. By uniting metabolic and psychosocial interventions within a single, rigorously defined framework, this research seeks to establish an innovative, patientcentered rehabilitation model.

This study employed a retrospective analysis method. From January 2023 to December 2023, 59 patients with acute cerebral infarction complicated by cognitive dysfunction were selected as the research group, and another 59 patients with the same condition were selected as the control group. General information for both groups is presented in the Results section. This study was approved by the hospital's medical ethics committee.

Inclusion criteria: (1) Patients with a confirmed diagnosis of cerebral infarction[10]; (2) Age > 60 years; and (3) Mild cognitive impairment, defined as a Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) score of 18-25 or a Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score of 21-26.

Exclusion criteria: (1) Patients with severe heart, liver, or kidney disorders; (2) Patients with a short onset time, currently in the acute phase; (3) Patients who have used antipsychotic drugs within the last week; and (4) Patients participating in other studies or unable to cooperate with this study.

The control group received routine interventions, including patient and family education on acute cerebral infarction and regular telephone followups. The research group received nursing interventions based on nutritional support and social support. Specific measures included the following:

Formation of a team: A fivemember intervention team consisting of one attending physician, one head nurse, one nursing team leader, and two charge nurses.

Scientific nutritional intervention: Nutritional risk was assessed by NRS2002, with enteral nutrition initiated for scores ≥ 3. Within 24-48 hours of onset, 500 mL of nutritional solution was delivered at 30 mL/h, increasing to 70 mL/h; after 48 hours, and the volume was raised to 1000-1500 mL at 70 mL/h. Patients’ oral intake was also monitored and healthy dietary guidance provided.

Structured social support plan: Psychological support was delivered by two nurses trained in mental health care via oneonone counseling sessions twice weekly (30 minutes each) for four weeks, beginning within 48 hours of enrollment; family support comprised weekly, 60minute education meetings for primary caregivers over four weeks-led by the attending physician or head nurse-to cover disease knowledge, emotional coping strategies, and caregiving techniques.

Unified training for team members: All team members completed standardized training on the above protocols before implementation.

WeChat and QQ group engagement: On Day 1, patient and caregiver groups were created, with the intervention team posting short videos and infographics on nutrition, emotional management, and rehabilitation exercises every weekday from 18:00 to 18:30, and responding to questions in real time throughout the fourweek intervention.

Primary observation indicators: (1) Comparison of nutritional status: 3 mL of venous blood was drawn from patients in the early morning in a fasting state. An automatic biochemical analyzer was used to measure serum albumin (Alb), prealbumin (PAB), and hemoglobin (Hb) levels; (2) Comparison of cognitive function: Cognitive function was evaluated using the MMSE and the MoCA, with both scoring a maximum of 30 points. The lower the score, the more severe the cognitive dysfunction[11,12]; (3) Comparison of anxiety status: The Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) was used for evaluation. An SAS score ≥ 50 indicates the presence of anxiety symptoms, with higher scores indicating greater anxiety severity[13]; and (4) Comparison of depression status: The Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS) was used for assessment (mild depression: 53-62 points, moderate depression: 63-72 points, severe depression: > 72 points). Higher scores indicate greater depression severity[14].

Secondary observation indicators: (1) Comparison of sleep quality: The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) was used for evaluation[15]. This scale consists of 19 self-assessed questions and 5 questions evaluated by a sleep partner. Only the 19 self-assessed questions were scored, each rated on a 0-3 scale across seven factors. The cumulative score across all factors provides the total PSQI score, which ranges from 0 to 21. Higher scores indicate poorer sleep quality; (2) Comparison of social function level: The Social Disability Screening Schedule (SDSS) was used for evaluation, which includes 10 items. Higher scores indicate more severe social dysfunction[16]; (3) Comparison of QoL: The Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short Form Health Survey was used to assess patients' QoL. This scale includes five dimensions: Physical function, overall health, social function, emotional role, and mental health. Each dimension has a maximum score of 100[17]; and (4) Comparison of patient satisfaction: Patients completed a satisfaction survey developed by the hospital (content validity of the scale: 0.87, Cronbach's α coefficient: 0.89) to assess nursing satisfaction. Satisfaction was classified as: Satisfied (90-100 points), basically satisfied (60-89 points), or dissatisfied (< 60 points). The satisfaction rate = (satisfied + basically satisfied cases)/total cases × 100%.

Data were analyzed using SPSS 20.0. Categorical data were expressed as [n (%)] and analyzed using the χ² test. For continuous data that followed a normal distribution, results were expressed as mean ± SD. Independent t-tests were used for comparisons between groups, and paired t-tests were used for within-group comparisons. Pearson correlation analysis was performed to assess the relationship between changes in nutritional markers (ΔAlb, ΔPA, ΔHb) and changes in cognitive scores (ΔMMSE, ΔMoCA). A P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

There were no statistically significant differences between the two groups in terms of age, gender, comorbidities, body mass index, and educational level (all P > 0.05). Therefore, the two groups were comparable (Table 1).

| Indicator | Research group (n = 59) | Control group (n = 59) | χ²/t | P value |

| Age (years) | 67.3 ± 4.1 | 68.4 ± 4.2 | 1.440 | 0.153 |

| Gender | 0.034 | 0.852 | ||

| Male | 26 | 25 | ||

| Female | 33 | 34 | ||

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Hypertension | 18 | 21 | 0.344 | 0.557 |

| Coronary heart disease | 19 | 14 | 1.051 | 0.305 |

| Diabetes | 9 | 6 | 0.687 | 0.407 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.31 ± 2.23 | 23.88 ± 2.55 | 1.292 | 0.199 |

| Education level (n) | 1.264 | 0.260 | ||

| Junior high school or below | 32 | 38 | ||

| High school or above | 27 | 21 |

Before the intervention, there were no statistically significant differences between the two groups in terms of serum Alb, serum PAB, and Hb (P > 0.05). After the intervention, the levels of serum Alb, serum PAB, and Hb significantly increased in both groups. The research group had higher serum Alb, serum PAB, and Hb levels compared to the control group (all P < 0.001), as shown in Table 2.

| Nutritional status indicators | Research group (n = 59) | Control group (n = 59) | ||

| Before intervention | After intervention | Before intervention | After intervention | |

| Alb (g/L) | 25.08 ± 6.75 | 34.11 ± 3.89a,b | 24.86 ± 6.73 | 28.76 ± 4.31b |

| PA (mg/L) | 120.54 ± 9.21 | 247.12 ± 16.12a,b | 121.45 ± 9.22 | 185.42 ± 14.15b |

| Hb (g/L) | 71.21 ± 9.13 | 85.33 ± 11.13a,b | 71.25 ± 9.09 | 76.31 ± 12.65b |

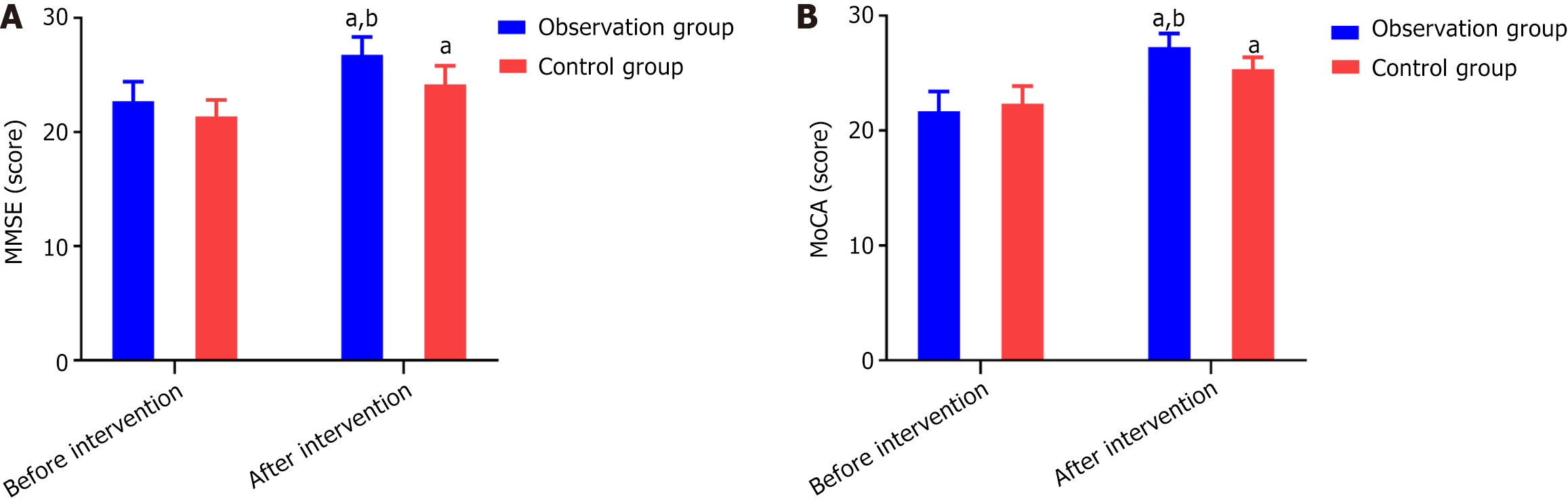

There was no statistically significant difference in the MMSE and MoCA cognitive function scores between the two groups before the intervention (P > 0.05). After the intervention, the scores of the research group were significantly higher than those of the control group (P < 0.05) (Figure 1).

Pearson correlation analysis demonstrated strong, highly significant associations between the magnitude of nutritional improvement and cognitive recovery. Improvements in serum Alb (ΔAlb) correlated strongly with gains in MMSE (r = 0.807, P < 0.001) and MoCA (r = 0.948, P < 0.001). Similarly, increases in PAB (ΔPA) were positively associated with ΔMMSE (r = 0.689, P < 0.001) and ΔMoCA (r = 0.878, P < 0.001). The tightest relationship was observed for Hb (ΔHb), which exhibited near-perfect correlations with both ΔMMSE (r = 0.979, P < 0.001) and ΔMoCA (r = 0.940, P < 0.001), as shown in Table 3.

| Cognitive indicator | Nutritional indicator | r | P value |

| ΔMMSE | ΔAlb | 0.807 | < 0.001 |

| ΔMMSE | ΔPA | 0.689 | < 0.001 |

| ΔMMSE | ΔHb | 0.979 | < 0.001 |

| ΔMoCA | ΔAlb | 0.948 | < 0.001 |

| ΔMoCA | ΔPA | 0.878 | < 0.001 |

| ΔMoCA | ΔHb | 0.940 | < 0.001 |

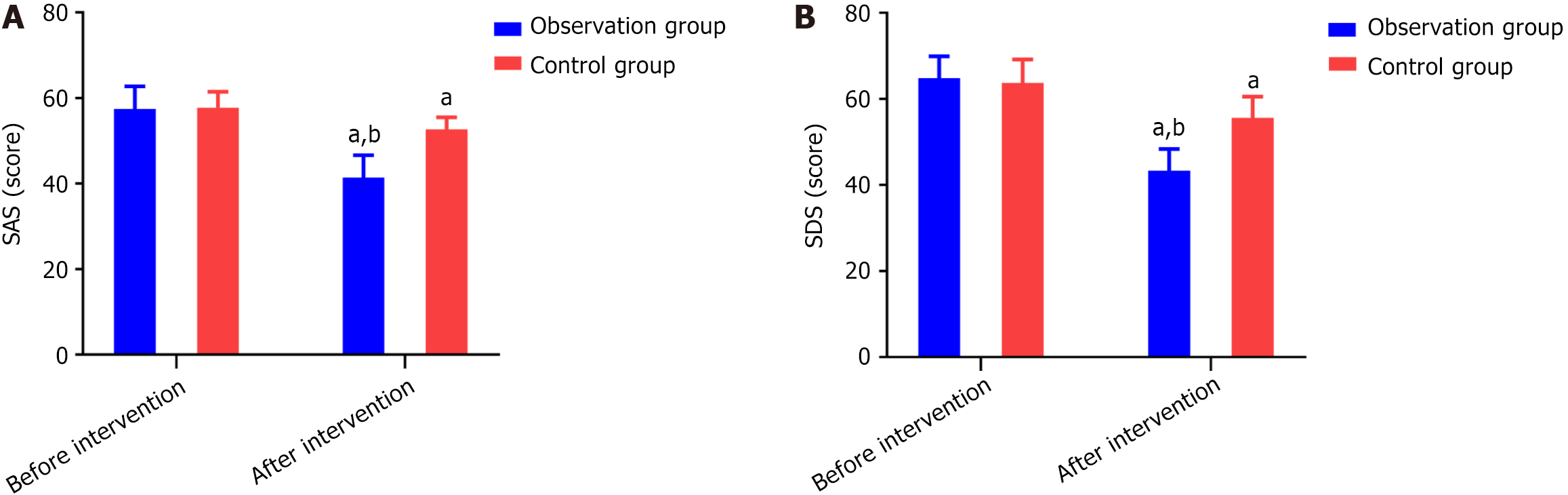

Before the intervention, there was no statistically significant difference in SAS scores and SDS scores between the two groups (P > 0.05). After the intervention, the scores of both groups significantly decreased, and the SAS and SDS scores in the research group were significantly lower than those in the control group (both P < 0.001), as shown in Figure 2.

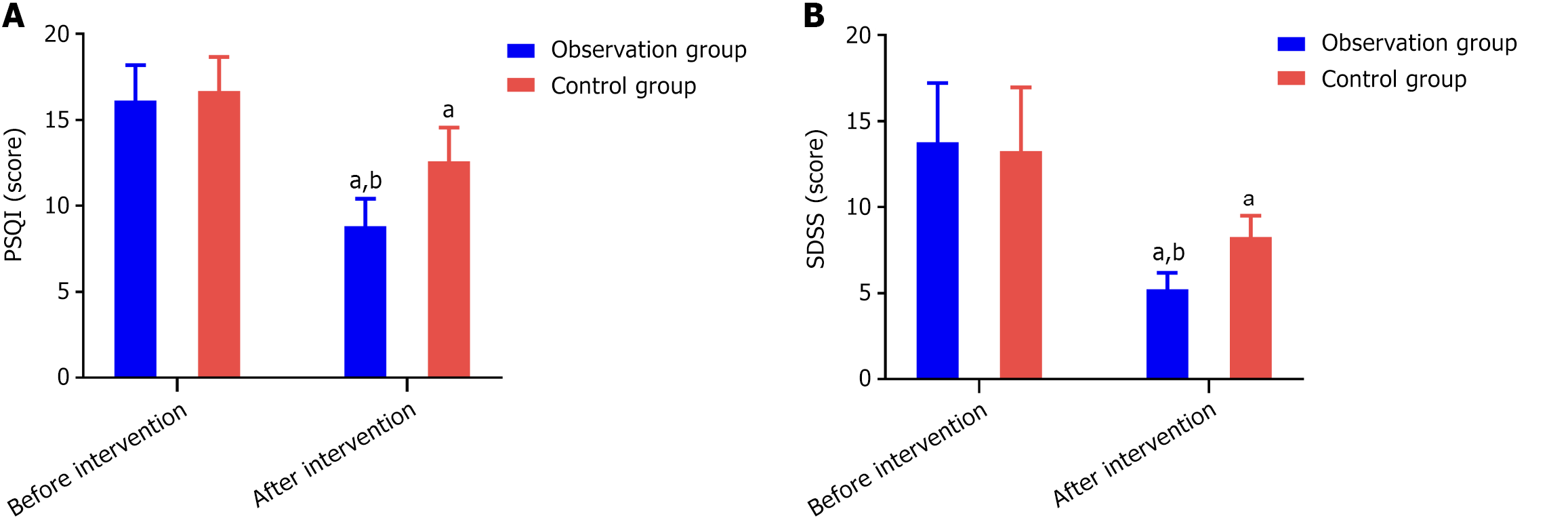

Before the intervention, there was no statistically significant difference in sleep quality scores between the two groups (P > 0.05). After the intervention, the scores of both groups significantly decreased, and the PSQI score of the research group was lower than that of the control group, with a statistically significant difference (P < 0.001) (Figure 3A).

Before the intervention, there were no statistically significant differences in SDSS scores between the two groups (P > 0.05). After the intervention, the scores of both groups significantly decreased, and the SDSS scores of the research group were lower than those of the control group, with the difference being statistically significant (P < 0.001) (Figure 3B).

Before the intervention, there was no statistical difference in the QoL scores between the two groups (P > 0.05). After the intervention, the scores of both groups significantly increased, and the scores in all dimensions (physical functioning, general health, social functioning, emotional role, and mental health) in the research group were higher than those in the control group, with statistically significant differences (all P < 0.01) (Table 4).

| Quality of life scores | Research group (n = 59) | Control group (n = 59) | t | P value | ||

| Before intervention | After intervention | Before intervention | After intervention | |||

| Physical functioning | 62.10 ± 8.55 | 78.22 ± 11.18a | 62.34 ± 8.05 | 66.17 ± 9.34a | 6.359 | < 0.001 |

| General health | 81.22 ± 11.83 | 92.63 ± 7.22a | 81.29 ± 9.23 | 86.64 ± 12.15a | 2.793 | 0.003 |

| Social functioning | 60.22 ± 10.20 | 73.85 ± 11.23a | 60.88 ± 10.23 | 65.54 ± 10.35a | 4.175 | < 0.001 |

| Emotional role | 50.54 ± 8.11 | 64.78 ± 9.67a | 50.58 ± 8.18 | 56.42 ± 7.23a | 5.309 | < 0.001 |

| Mental health | 49.42 ± 7.50 | 69.22 ± 10.89a | 49.41 ± 7.44 | 56.34 ± 7.67a | 7.427 | < 0.001 |

The research group showed significantly higher satisfaction with nutritional intervention and social support compared to the core caregivers (P < 0.05) (Table 5).

| Group | Satisfied | Generally satisfied | Dissatisfied | Satisfaction rate |

| Research group (n = 59) | 28 (47.46) | 26 (44.07) | 5 (8.47) | 54 (91.53) |

| Control group (n = 59) | 21 (35.59) | 23 (38.98) | 15 (25.42) | 44 (74.58) |

| χ² | 6.020 | |||

| P value | 0.014 | |||

Both the MMSE and MoCA assess global cognition but emphasize different domains-MMSE focuses on orientation, immediate recall, language and attention, whereas MoCA extends to executive functions, abstraction, and visuospatial abilities, making it more sensitive to early or subtle deficits[11,12]. In our research group, both MMSE and MoCA scores rose significantly, but the proportional gain in MoCA exceeded that in MMSE, suggesting that combined nutritional and social support may particularly enhance higherorder cognitive processes. Mechanistically, optimized enteral nutrition elevates circulating levels of essential amino acids and fatty acids-substrates for neurotrophic factor and membrane phospholipid synthesis-which support neuronal membrane repair, neurotransmitter production and reduce neuroinflammation, pathways highlighted by Choi et al[18]. Key micronutrients such as B vitamins further mitigate homocysteine toxicity and promote myelination, while antioxidants scavenge reactive oxygen species to limit secondary ischemic damage. At the same time, structured psychological counseling and family engagement provide sustained cognitive stimulation, reduce stressrelated cortisol release-and thus preserve hippocampal neurogenesis-and foster neuroplastic changes within frontalsubcortical circuits by upregulating BDNF and NGF expression. The concurrent improvements in serum Alb, PAB and Hb further indicate enhanced systemic and cerebral perfusion, which is critical for hippocampal function and executive network integrity[19]. In contrast, Li et al’s study[19], while demonstrating similar nutritional gains, lacked a coordinated psychosocial component and recorded smaller cognitive improvements-underscoring that biological restoration alone may be insufficient to maximize recovery in domains requiring motivation, problemsolving and social interaction. Moreover, our Pearson correlation analysis, which revealed strong, highly significant associations between increases in serum Alb, PAB, and Hb and gains in both MMSE and MoCA scores (r = 0.689-0.979, P < 0.001), further confirms that improvements in nutritional status are closely linked to cognitive enhancement in this patient population. Together, these data support a multimodal rehabilitative approach that addresses both the metabolic substrates for neural repair and the psychosocial drivers of neuroplasticity to optimize cognitive recovery after stroke.

Ma et al's research found that social support promotes cognitive function recovery by increasing patients' participation in rehabilitation and enhancing the effectiveness of cognitive training[20]. The social support system provides emotional support and opportunities for social interaction, helping to reduce feelings of loneliness and depressive symptoms, which in turn aids in the improvement of cognitive function. Enhanced social support not only improves patients' treatment compliance and participation but also improves their psychological state, further enhancing the effectiveness of cognitive training. Studies have shown that emotional support, social connections, and psychological care play a crucial role in cognitive recovery, especially for elderly patients, as social support can significantly slow down the process of cognitive decline[21]. Under the multidimensional intervention of nutritional support and social support, patients receive comprehensive care and support during the process of cognitive function recovery, which helps improve cognitive abilities and promote brain function improvement. Additionally, the SDSS scores indicate that social support can improve patients' social participation and psychological adaptation, further enhancing their social functioning.

Anxiety and depression are common complications in patients with acute cerebral infarction, significantly negatively impacting cognitive function and the overall rehabilitation process[22]. Anxiety and depression can exacerbate neurotransmitter imbalances, especially serotonin and dopamine, which play crucial roles in mood regulation and cognitive function. Emotional disorders not only lead to further deterioration of cognitive abilities, such as memory loss and difficulty concentrating, but may also affect the patient's sleep quality, which in turn worsens cognitive impairment, creating a vicious cycle. Additionally, anxiety and depression symptoms can reduce patients' treatment compliance and decrease their participation in rehabilitation and therapy, delaying neurological recovery. Studies have shown[23] that emotional disorders also increase the risk of long-term cognitive decline and memory impairment in stroke patients. In this study, the SAS and SDS scores of the research group were significantly lower than those of the control group, indicating that nutritional intervention and social support can significantly alleviate anxiety and depression symptoms, which is consistent with the findings of Zhao et al[24]. Through psychological support and family involvement, patients can receive emotional care and support, thus alleviating negative emotions and improving their emotional state. Nutritional intervention improves brain metabolism and neurotransmitter levels, providing a physiological basis for psychological recovery, while social support strengthens patients' social connections and family support, creating a favorable emotional recovery environment. Furthermore, PSQI scores also showed that the sleep quality of patients in the research group was significantly improved under the comprehensive intervention, which is consistent with the findings of Niu et al[25], further indicating that alleviating anxiety and depression symptoms can effectively improve patients' sleep quality, providing positive support for their overall rehabilitation.

QoL is an important indicator of stroke patients' rehabilitation and has become a key criterion for evaluating treatment effectiveness[26]. Stroke not only damages the physiological function of patients but can also lead to psychological and social dysfunction, all of which jointly affect the overall QoL. Therefore, improving QoL has become an important goal of clinical intervention. This study shows that nutritional intervention and social support have played a positive role in the multidimensional rehabilitation of stroke patients. Patients in the research group scored significantly higher than those in the control group in areas such as physical function, overall health, social function, emotional role, and mental health, with the differences being statistically significant. The reason for this is that the improvement in QoL is associated with nutritional intervention, which enhances physiological health and cognitive recovery by improving indicators like serum Alb, PAB, and Hb. At the same time, social support alleviated anxiety and depression symptoms through emotional support and social interactions, improving mental health and sleep quality, further promoting cognitive function recovery. Overall, the combined effect of nutritional intervention and social support effectively improved the patients' QoL, which is consistent with existing research, emphasizing the key role of multi-level interventions in stroke rehabilitation.

Finally, this study also assessed the satisfaction of the two groups of patients. The results showed that satisfaction in the research group was significantly higher than that in the control group. This may be due to the comprehensive intervention model, which alleviated the patients' anxiety and depression, improved their QoL, and led to a better subjective experience for the patients.

Despite yielding positive results, this study has several limitations. First, its retrospective design may have introduced selection bias and provides a relatively low level of evidence. Second, the small sample size and singlecenter recruitment may limit the generalizability of our findings. Third, we did not systematically assess the fidelity or standardization of our nutritional and social support protocols, nor did we track patient adherence to each component-factors that could substantially influence the consistency and magnitude of observed effects. Therefore, future research should employ largerscale, multicenter randomized controlled trials with rigorous intervention standardization, fidelity checks, and adherence monitoring. Moreover, subsequent studies should evaluate the impact of these interventions on stroke recurrence rates and longterm survival to fully elucidate their clinical value.

In conclusion, nutritional intervention and social support significantly improved the cognitive function, psychological status, and QoL of patients with acute cerebral infarction and concomitant cognitive dysfunction. These interventions alleviated anxiety and depression symptoms, improved sleep and nutritional status, and enhanced patients' social adaptability and family satisfaction. Therefore, they are worthy of clinical promotion and application.

| 1. | Savaliya R, Chavda VK, Patel B, Brahmbhatt R, Chaurasia B. Acute ischemic stroke: research perspective vs. clinical practice. Neurosurg Rev. 2024;47:612. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Wang X, Chen J, Liu YE, Wu Y. The Effect of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy on Psychological Nursing of Acute Cerebral Infarction with Insomnia, Anxiety, and Depression. Comput Math Methods Med. 2022;2022:8538656. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Xie H, Gao M, Lin Y, Yi Y, Liu Y. An emergency nursing and monitoring procedure on cognitive impairment and neurological function recovery in patients with acute cerebral infarction. NeuroRehabilitation. 2022;51:161-170. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Potter TBH, Tannous J, Vahidy FS. A Contemporary Review of Epidemiology, Risk Factors, Etiology, and Outcomes of Premature Stroke. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2022;24:939-948. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Dang J, Li G, Wu Q, Pian G, Wang Z. Impacts of evidence-based nursing combined with enteral nutrition on nutritional status and quality of life in acute cerebral infarction patients: A randomized controlled trial. Perfusion. 2023;2676591231223910. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Zhang H, Yang J, Xiong Y. Influence of Nutritional Support Program on Gastrointestinal Function, Complication Rate, and Prognosis in Elderly Sufferers with CI. Biomed Res Int. 2022;2022:3198272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Yang F, Zhang P. Prevalence and Predictive factors of Post-Stroke Depression in Patients with Acute Cerebral Infarction. Alpha Psychiatry. 2024;25:592-597. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Shenk MK, Morse A, Mattison SM, Sear R, Alam N, Raqib R, Kumar A, Haque F, Blumenfield T, Shaver J, Sosis R, Wander K. Social support, nutrition and health among women in rural Bangladesh: complex tradeoffs in allocare, kin proximity and support network size. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2021;376:20200027. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Wang Y, Li G, Ding S, Zhang Y, Zhao C, Sun M. Correlation Between Resilience and Social Support in Elderly Ischemic Stroke Patients. World Neurosurg. 2024;184:e518-e523. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Wang HJ, Hsu LF. The role of partial area under the curve and maximum concentrations in assessing the bioequivalence of long-acting injectable formulation of exenatide_A sensitivity analysis. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2024;195:106718. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. "Mini-mental state". A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189-198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56757] [Cited by in RCA: 61872] [Article Influence: 1213.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, Charbonneau S, Whitehead V, Collin I, Cummings JL, Chertkow H. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:695-699. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11622] [Cited by in RCA: 17330] [Article Influence: 825.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Dunstan DA, Scott N, Todd AK. Screening for anxiety and depression: reassessing the utility of the Zung scales. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17:329. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 159] [Cited by in RCA: 313] [Article Influence: 34.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Gaetani L, Salvadori N, Brachelente G, Sperandei S, Di Sabatino E, Fiacca A, Mancini A, Villa A, De Stefano N, Parnetti L, Di Filippo M. Intrathecal B cell activation and memory impairment in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2024;85:105548. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Buysse DJ, Hall ML, Strollo PJ, Kamarck TW, Owens J, Lee L, Reis SE, Matthews KA. Relationships between the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS), and clinical/polysomnographic measures in a community sample. J Clin Sleep Med. 2008;4:563-571. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Zhang D, Wei J, Li X. The mediating effect of social functioning on the relationship between social support and fatigue in middle-aged and young recipients with liver transplant in China. Front Psychol. 2022;13:895259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Vitorino DFDM, Martins FLM, Souza ADC, Galdino D, Prado GFD. Utilização do SF-36 em ensaios clínicos envolvendo pacientes fibromiálgicos. Rev Neurocienc. 2019;12:147-151. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 18. | Choi YR, Kim HS, Yoon SJ, Lee NY, Gupta H, Raja G, Gebru YA, Youn GS, Kim DJ, Ham YL, Suk KT. Nutritional Status and Diet Style Affect Cognitive Function in Alcoholic Liver Disease. Nutrients. 2021;13:185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Li ZN, Zhai YJ. [Advances in nutritional support therapy for stroke prevention and treatment]. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2022;56:146-150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Ma W, Wu B, Gao X, Zhong R. Association between frailty and cognitive function in older Chinese people: A moderated mediation of social relationships and depressive symptoms. J Affect Disord. 2022;316:223-232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Henderson ER, Haberlen SA, Coulter RWS, Weinstein AM, Meanley S, Brennan-Ing M, Mimiaga MJ, Turan JM, Turan B, Teplin LA, Egan JE, Plankey MW, Friedman MR. The role of social support on cognitive function among midlife and older adult MSM. AIDS. 2023;37:803-811. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Roh HW, Cho EJ, Son SJ, Hong CH. The moderating effect of cognitive function on the association between social support and depressive symptoms among community-dwelling older adults: Cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses. J Affect Disord. 2022;318:185-190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Wen A, Fischer ER, Watson D, Yoon KL. Biased cognitive control of emotional information in remitted depression: A meta-analytic review. J Psychopathol Clin Sci. 2023;132:921-936. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Zhao Y, Hu B, Liu Q, Wang Y, Zhao Y, Zhu X. Social support and sleep quality in patients with stroke: The mediating roles of depression and anxiety symptoms. Int J Nurs Pract. 2022;28:e12939. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Niu S, Liu X, Wu Q, Ma J, Wu S, Zeng L, Shi Y. Sleep Quality and Cognitive Function after Stroke: The Mediating Roles of Depression and Anxiety Symptoms. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20:2410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Orman Z, Thrift AG, Olaiya MT, Ung D, Cadilhac DA, Phan T, Nelson MR, Srikanth VK, Vuong J, Bladin CF, Gerraty RP, Fitzgerald SM, Frayne J, Kim J; STANDFIRM (Shared Team Approach between Nurses and Doctors For Improved Risk factor Management) Investigators. Quality of life after stroke: a longitudinal analysis of a cluster randomized trial. Qual Life Res. 2022;31:2445-2455. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/