Published online Oct 19, 2025. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v15.i10.106904

Revised: June 18, 2025

Accepted: August 4, 2025

Published online: October 19, 2025

Processing time: 128 Days and 23.4 Hours

Cox health behavior interventions combined with psychological care have the potential to improve recovery outcomes and psychological well-being in patients with hypertensive cerebral hemorrhage accompanied by mental disorders.

To explore the impact of combining the Cox Health Behavior Interaction Model with multifaceted psychological nursing in patients with hypertensive intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) complicated by mental disorders and to provide a reference for the nursing intervention in patients with hypertensive ICH.

Overall, 128 patients with hypertensive ICH complicated by mental disorders who were admitted to the Affiliated Hospital of Nantong University between January 2022 and December 2024 were divided into groups using a random number table. The control group (n = 64) received multifaceted psychological nursing, and the observation group (n = 64) received the Cox Health Behavior Interaction Model intervention based on multifaceted psychological nursing. The mental state, psychological resilience, self-efficacy, and quality of life of the two groups were compared.

Post-intervention, the mental states of anxiety and depression in the observation group (38.82 ± 3.67 points and 35.14 ± 2.75 points, respectively) were lower than those in the control group (46.96 ± 5.12 points and 41.36 ± 3.71 points, res

Combining the Cox Health Behavior Interaction Model with multifaceted psychological nursing for patients with hypertensive ICH and mental disorders relieves anxiety and depression and improves resilience, self-efficacy, and quality of life.

Core Tip: Reasonable and timely intervention is crucial for patients suffering from hypertensive intracerebral hemorrhage, as it can significantly improve prognosis and reduce the risk of complications. This is especially important for individuals who also suffer from coexisting mental disorders, as their condition may complicate clinical management, delay recovery, and impact treatment adherence. A comprehensive, multidisciplinary approach is therefore essential to address both neurological and psychiatric aspects effectively.

- Citation: Lu ND, Zhou JJ, Huang F. Cox health behavior intervention combined with psychological care for patients with hypertensive cerebral hemorrhage and mental disorders. World J Psychiatry 2025; 15(10): 106904

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v15/i10/106904.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v15.i10.106904

Hypertensive intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) is a common, critical, and severe condition in neurosurgery. It typically presents with acute onset and rapid progression. Immediate surgical treatment after admission can improve patient prognosis and increase the survival rate. However, despite successful surgeries, most patients experience varying degrees of limb dysfunction. Rehabilitation is often slow and prolonged, significantly compromising the quality of life. Consequently, many patients develop mental disorders such as anxiety, depression, or post-stroke emotional disturbances, which further hinder recovery and lower treatment compliance[1].

Survivors of ICH frequently experience psychological distress, including a sense of shame, social withdrawal, and poor mental well-being[2]. Specifically, anxiety has been identified as a key mediating factor linking disease perception and emotional shame to a reduced quality of life. This mediating effect of anxiety accounts for approximately 55.6% of the total effect[2], highlighting the urgent need for targeted psychological support in this patient population.

Therefore, addressing not only the physical rehabilitation of these patients but also their psychological state during recovery is of great clinical significance. Multifaceted psychological care offers comprehensive and individualized mental health support for patients. This form of intervention can reduce the psychological burden and enhance self-efficacy by building emotional trust and motivating patients to engage in rehabilitation[3]. However, patients’ limited understanding of their disease and low awareness of personal health responsibility are often barriers to psychological recovery and behavioral change.

To overcome these challenges, the integration of structured health education with psychological care is becoming increasingly important. This encourages patients to develop healthier behavioral patterns and regain their mental resilience. The Cox Health Behavior Interaction Model, proposed in 1982 provides a theoretical framework for such interventions. This model involves an interactive feedback cycle encompassing three dimensions: Patient characteristics, nurse-patient (or doctor-patient) interactions, and health outcomes. It emphasizes personalized health behavioral interventions to mobilize patients’ initiatives, improve their health conditions, and promote long-term behavioral changes[4].

However, research on the application of the Cox Health Behavior Interaction Model in patients with hypertensive ICH remains limited, especially in those with mental disorders. Therefore, this study applied the Cox model combined with multifaceted psychological nursing to such patients and explored the effects on the patient recovery and psychological status.

A total of 128 patients with hypertensive ICH complicated by mental disorders who were admitted to the Affiliated Hospital of Nantong University between January 2022 and December 2024 were selected and divided into groups using the random number table method. The control group comprised 64 patients, including 34 males and 30 females, who were aged 35-72 years (average: 52.18 ± 4.63 years) and had a history of hypertension of 3-16 years (8.72 ± 2.04 years). The bleeding sites of the control group were the basal ganglia (n = 38), thalamus (n = 18), and cerebral lobe (n = 8), and the amount of bleeding was 10-30 mL (18.97 ± 2.15 mL). The educational attainment of the control group was primary and junior high school (n = 30), senior high school (n = 28), and junior college and above (n = 6). The observation group comprised 64 patients, including 31 males and 33 females, who were aged 32-70 years (average: 53.06 ± 4.84 years) and had a history of hypertension of 3-18 years (9.04 ± 2.12 years). The bleeding sites of the observation group were the basal ganglia (n = 35), thalamus (n = 22), and cerebral lobe (n = 9), and the amount of bleeding was 10-30 mL (19.01 ± 2.38 mL). The educational attainment of the observation group was primary and junior high school (n = 33), senior high school (n = 26), and junior college and above (n = 5). The basic information was not significantly different between the two groups (P > 0.05), indicating that they were comparable.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Patients who met the diagnostic criteria for hypertensive ICH[5] based on comprehensive examinations such as clinical manifestations, cranial computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging; (2) Patients with clear surgical indications and who successfully completed the surgical treatment; (3) Patients with clear consciousness after surgery and normal communication abilities; (4) Those who completed the questionnaires independently; and (5) Patients who were aware of the specific study details and provided written informed consent.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Mental diseases, such as schizophrenia, anxiety disorder, or a history of depression, before the onset of ICH; (2) Visual or auditory impairments; (3) ICH caused by other factors, such as tumors or trauma; (4) Disorders of other organs, such as the heart, liver, or kidneys; (5) Physical function disorders before onset that required assistance from others; and (6) Malignant tumors.

Both groups received routine nursing care, including hemostasis and anti-infection measures, after admission. All surgeries were performed by the same group of surgeons. The postoperative changes in vital signs were monitored closely, and routine nursing interventions such as diet, medication, and limb function rehabilitation were performed. The control group received multifaceted psychological nursing.

Emotional support: The nursing staff observed changes in the patients’ psychological state, assessed their inner thoughts and psychological state, and protected their privacy. They guided patients to understand the disease correctly. They increased the confidence of patients in rehabilitation by sharing successful rehabilitation cases and their own rehabilitation experiences and encouraged communication among patients.

Family interventions: The nursing staff actively communicated with the patients’ families and explained the causes of the disease, postoperative rehabilitation measures, and their possible effects. They provided psychological counseling to the patients’ families, encouraged the families to accompany the patients and participate in the disease rehabilitation nursing, provided sufficient encouragement and support to the patients, and reduced their psychological burden.

Individualized nursing: For patients with severe adverse emotions, mindfulness music and positive psychological suggestions were used to reduce their psychological burden. Health education was used to increase the understanding of patients with insufficient knowledge of the disease. Patients’ mental status was monitored, and methods such as meditation training, relaxation exercises, and music therapy were used to divert their attention and reduce their psychological burden.

The observation group received an intervention of the Cox Health Behavior Interaction Model based on the control group.

Assessment: The nursing staff conducted face-to-face interviews with patients and investigated their psychological and cognitive conditions using motivational interviews. During the interview, the patients’ tone of voice and expressions were monitored. The interview included the following questions: What was your experience with the disease? Do you know of any ways to relieve the disease? Do you think maintaining a good psychological state is important? What do you know about anxiety and depression? How has your mental state changed since you became ill? The interview results and patients’ characteristics, understanding of the disease, family and social support, and economic situation were used to explore problems in the patients’ disease rehabilitation and self-management and to mobilize the patients’ internal motivation for rehabilitation.

Nurse-patient communication: Patients’ understanding of hypertension and ICH were investigated using face-to-face communications. The disease was explained to the patients vocally and using pictures and short videos, and the rehabilitation manual “Key Points of Rehabilitation Knowledge for Hypertensive ICH”, which included the pathogenesis, risk factors, causes of mental disorders, and possible hazards, was provided to patients. The patients’ mastery of knowledge of the disease was evaluated, and their questions were answered immediately using lectures. The patients were guided to master methods such as mindfulness-based stress reduction, breathing relaxation training, whole-body muscle relaxation, and imagination therapy, and they were guided to perform psychological self-relaxation methods.

Emotional support: Communications with the patients and their families were monitored; the staff patiently listened to the patients’ self-expressed thoughts and emotions and provided emotional support, including communications among patients, sharing the experiences of successful rehabilitation cases, family companionship, and encouragement. Professional psychological counseling was provided, to increase patients’ confidence in rehabilitation. Simultaneously, patients’ inner concerns, such as worrying about physical disabilities and the inability to care for themselves, were monitored. Rehabilitation video exercises and power point were used to explain that rehabilitation training can improve physical function and gradually restore activities of daily living. Patients who maintained a good mood, actively participated in rehabilitation training and treatment, and maintained healthy habits were encouraged and rewarded. Patients were encouraged to share their rehabilitation experiences with each other, supervise each other, and play a supervisory role in the family, to support patient cooperation with rehabilitation training and treatment.

Decision-making control: The patients and their families jointly formulated a rehabilitation plan, including limb rehabilitation training and changes in the diet structure, bad behaviors (e.g., smoking and drinking), and psychological state. Rehabilitation goals were set, and patients who completed their goals were encouraged, affirmed, and praised. The reasons why patients had not achieved their goals were analyzed, solutions were proposed, and their problems and bad behaviors were examined, to improve their self-decision-making ability.

Professional skill guidance: Rehabilitation physicians guided the patients’ limb training movements during hospitalization and at home and instructed the families to supervise their daily life training. Telephone and WeChat follow-ups provided patients with dietary guidance, exercise management, medication guidance, emotional regulation, smoking cessation, alcohol abstinence, and self-monitoring. Patients were requested to send dietary pictures to the WeChat group every week, punch in for limb training in the WeChat group, share their experiences of self-management, and answer questions. Both groups underwent a continuous intervention for 12 weeks.

Mental state: The Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS)[6] and Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS)[7] were used for the evaluation before and after the intervention. The SAS and SDS, both developed by Zung, were used to assess patients’ anxiety and depression over the prior week. Each scale consisted of 20 items scored on a 4-point Likert scale, from 1 (a little of the time) to 4 (most of the time). The total raw score of each scale was multiplied by 1.25 to obtain the standard score, with a range of 25-100. For the SAS, a standard score of < 50 indicated no anxiety, 50-59 indicated mild anxiety, 60-69 represented moderate anxiety, and ≥ 70 suggested severe anxiety. For the SDS, a standard score of < 53 indicated no depression, 53-62 indicated mild depression, 63-72 represented moderate depression, and ≥ 73 suggested severe depression. Higher scores on both scales reflected more severe emotional symptoms.

Psychological resilience: Psychological resilience is an individual’s ability to adapt to stress, adversity, or trauma and recover from negative emotional experiences. In patients with hypertensive ICH, resilience plays a key role in emotional regulation, coping behaviors, and motivation to engage in rehabilitation. Higher resilience levels are associated with a reduced risk of anxiety and depression, better adherence to treatment, and functional recovery. The Psychological Resilience Scale[8] was used for the evaluation before and after the intervention and included three dimensions: Tenacity, self-improvement, and optimism. Each dimension had 13 items, 8 items, and 4 items, respectively, with each item scored from 0 point to 4 points. The total scores were 52, 32, and 16, respectively. The score increased with improvement in psychological resilience.

Self-efficacy: Self-efficacy, a concept introduced by Bandura, refers to an individual’s belief in their capacity to execute the behaviors necessary to produce specific performance outcomes. In patients recovering from ICH, strong self-efficacy is associated with greater engagement in physical rehabilitation, better management of health behaviors, and improved psychological adjustment. Interventions that enhance patient self-efficacy can positively influence both mental and physical health outcomes. The General Self-Efficacy Scale[9] was used for the evaluation. The scale consisted of 10 items, and each item was scored from 1 point to 4 points. The maximum possible score was 40 points. The score increased with improvement in the self-efficacy.

Quality of life: The Stroke-Specific Quality of Life Scale (SS-QOL)[10] is a multidimensional tool that encompasses an individual’s physical health, psychological state, level of independence, social relationships, and interaction with the environment. It serves as a comprehensive indicator of recovery in stroke patients, including those with hypertensive ICH. Postoperative complications, emotional disorders, and impaired daily functioning often lead to significant declines in SS-QOL scores, making it a critical endpoint for evaluating the effectiveness of nursing and behavioral interventions. The Simplified SS-QOL[10] was used for evaluation before and after the intervention and included two dimensions: The physical health-related quality of life and the social and mental health-related quality of life. Each dimension had 6 items, for a total of 12 items, and each item was scored from 0 to 4 points. The total possible score for each dimension was 48 points. The score increased with improvements in the quality of life.

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 26.0. Measurement data conforming to a normal distribution are expressed as (mean ± SD), and the t-test was used. Enumeration data are expressed as a percentage ratio (%), and the χ2 test was used. P values < 0.05 indicated statistical significance.

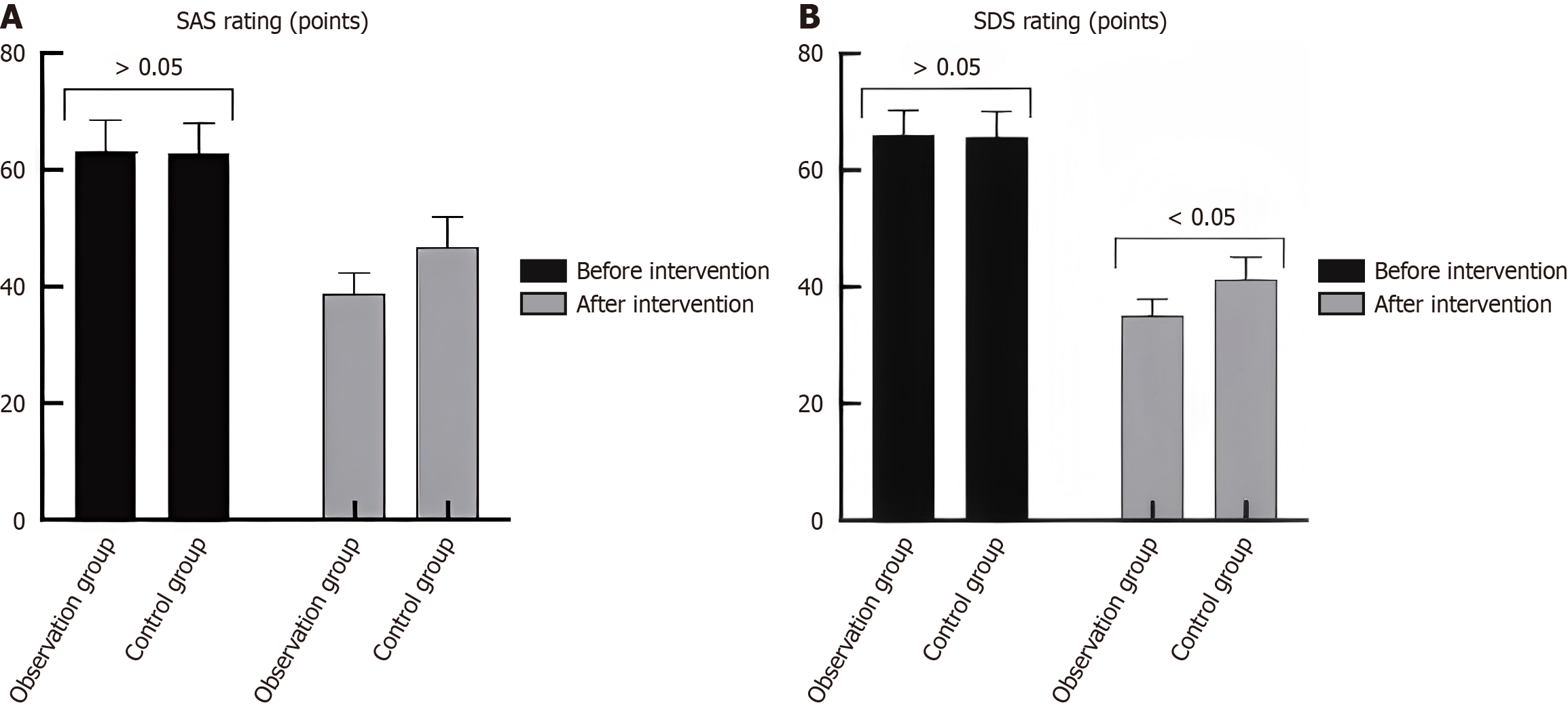

Before the intervention, the anxiety (SAS) and depression (SDS) scores were not significantly different between the groups (P > 0.05). The observation group had an SAS score of 63.50 ± 5.27 and an SDS score of 66.04 ± 4.18, while the control group had an SAS score of 62.87 ± 5.36 and an SDS score of 65.72 ± 4.35. After the 12-week intervention, the SAS and SDS scores decreased significantly in both groups (P < 0.05). The observation group showed a greater improvement, with a post-intervention SAS score of 38.82 ± 3.67 and an SDS score of 35.14 ± 2.75. In contrast, the control group had a post-intervention SAS score of 46.96 ± 5.12 and an SDS score of 41.36 ± 3.71. The between-group differences after the intervention were statistically significant (SAS: t = 10.337, P < 0.001; SDS: t = 10.775, P < 0.001) and indicated a greater reduction in anxiety and depression in the observation group (Table 1, Figure 1).

The resilience was not significantly different between the two groups (P > 0.05). Patients improved after the intervention, with a significant increase in the observation group (P < 0.05) (Table 2).

| Group | Diligence | Self-improvement | Optimism | |||

| Before | After | Before | After | Before | After | |

| Observation group (n = 64) | 22.10 ± 4.26 | 38.96 ± 4.31a | 14.73 ± 2.71 | 24.07 ± 2.91a | 7.92 ± 1.64 | 12.04 ± 1.31a |

| Control group (n = 64) | 21.64 ± 4.38 | 34.07 ± 4.28a | 15.03 ± 2.86 | 19.73 ± 3.05a | 8.08 ± 1.72 | 10.17 ± 1.38a |

| t | 0.602 | 6.440 | 0.609 | 8.236 | 0.539 | 7.862 |

| P value | 0.548 | < 0.001 | 0.544 | < 0.001 | 0.591 | < 0.001 |

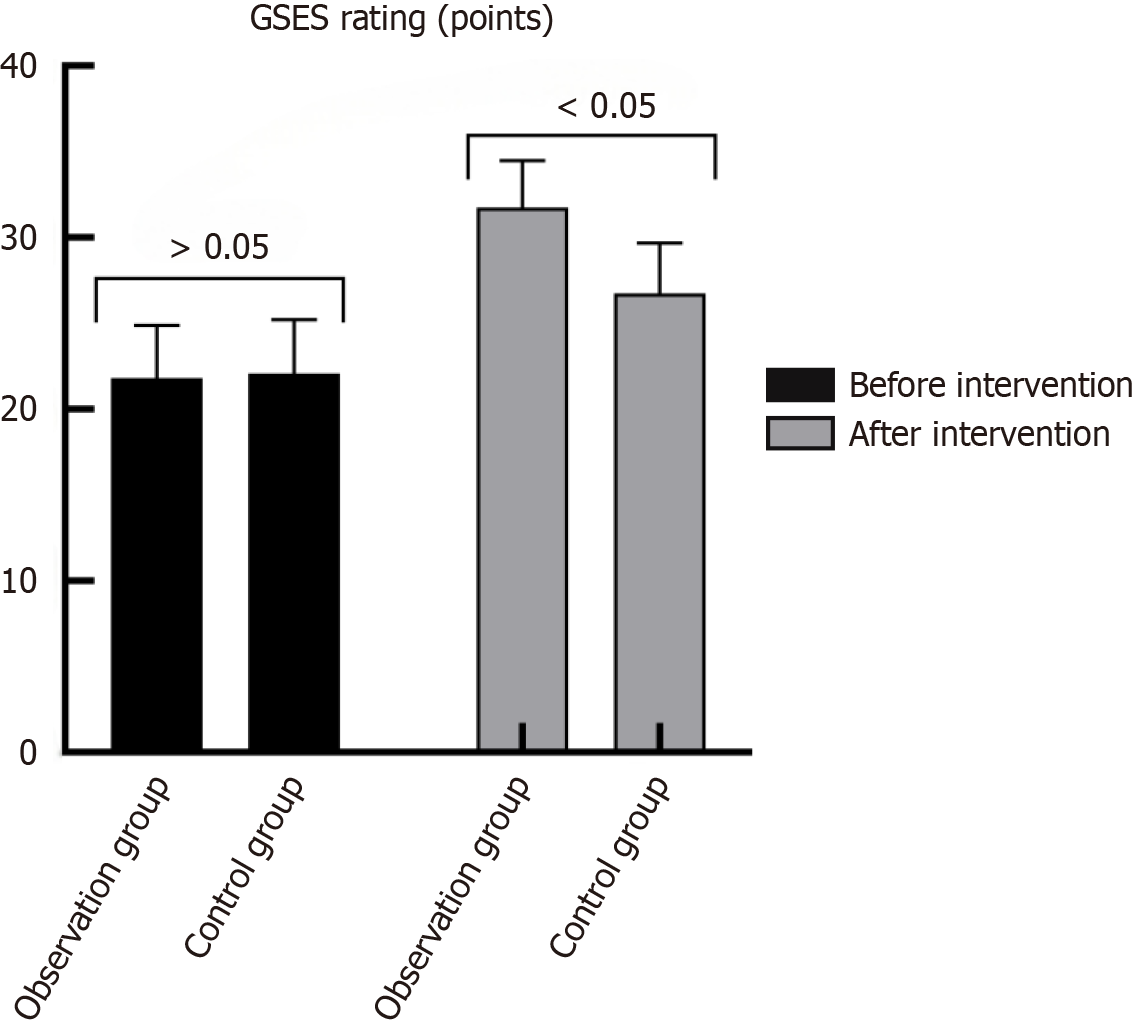

Before the intervention, the General Self-Efficacy Scale scores were similar between the groups (observation: 21.81 ± 3.06, control: 22.07 ± 3.14; P = 0.636). After the intervention, the observation group had a significantly higher score (31.75 ± 2.75) than the control group (26.76 ± 2.93) (t = 9.934, P < 0.001). The increase in the observation group was more pronounced (t = 19.328, P < 0.001), indicating enhanced confidence in coping with the disease and recovery (Table 3, Figure 2).

| Group | Before | After | t | P value |

| Observation group (n = 64) | 21.81 ± 3.06 | 31.75 ± 2.75 | 19.328 | < 0.001 |

| Control group (n = 64) | 22.07 ± 3.14 | 26.76 ± 2.93 | 8.736 | < 0.001 |

| t | 0.474 | 9.934 | - | - |

| P value | 0.636 | < 0.001 | - | - |

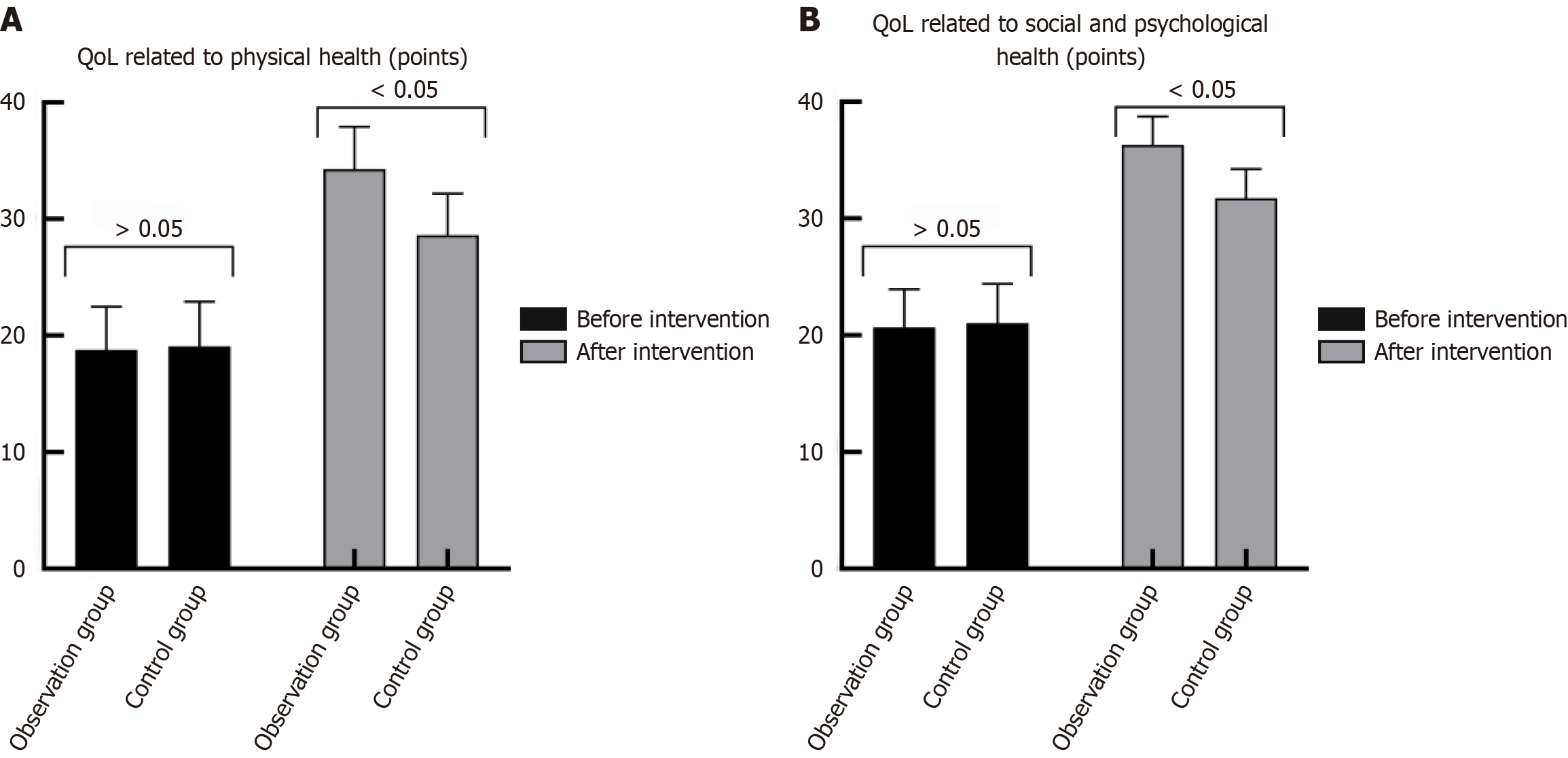

The quality of life was not significantly different before the intervention (P > 0.05). The quality of life improved after the intervention, and the increase in the observation group was significant (P < 0.05) (Table 4, Figure 3).

| Group | Physical health-related quality of life | Psychosocial health-related quality of life | ||

| Before | After | Before | After | |

| Observation group (n = 64) | 18.79 ± 3.71 | 34.28 ± 3.64a | 20.67 ± 3.27 | 36.31 ± 2.43a |

| Control group (n = 64) | 19.10 ± 3.82 | 28.61 ± 3.57a | 21.06 ± 3.35 | 31.74 ± 2.50a |

| t | 0.466 | 8.897 | 0.666 | 10.486 |

| P | 0.642 | < 0.001 | 0.506 | < 0.001 |

Hypertensive ICH is a rapidly progressive disease. Patients experience an increased survival rate after receiving timely and effective treatment during their hospital stay. However, most patients have varying degrees of physical function impairment after surgery, resulting in limited daily living functions and low self-care abilities, which lead to psychological problems. Mental disorders are common among patients with hypertensive ICH. Anxiety and depression can affect patients’ quality of life and hinder their physical and mental development[11]. Therefore, psychological interventions are often used to reduce the psychological burden of such patients. Multifaceted psychological nursing includes aspects such as emotional support and family intervention and adopts individualized and comprehensive psychological nursing according to the different causes of the patients’ abnormal psychology, to relieve the patients’ negative mental state. However, relying solely on psychological nursing makes it difficult to resolve patients’ mental disorders completely. Patients’ insufficient understanding of the disease and lack of healthy behaviors affect their physical and mental health and exacerbate abnormal mental states. Therefore, when implementing psychological nursing for patients, other nursing interventions should be combined to relieve the psychological burdens. The Cox Health Behavior Interaction Model emphasizes patient assessments and nurse-patient communication. Health information, emotional support, decision-making control, and professional skill guidance can tap into patients’ internal potential, enhance their own abilities, improve their understanding of the disease, and relieve their mental disorders.

Patients with hypertensive ICH show varying degrees of psychological and physiological stress responses after the disease onset. Coupled with physical functional impairments, it induces mental disorders. After patients with hypertensive ICH develop mental disorders, they develop obvious anxious and depressive states, strong psychological stress responses, reduced psychological resilience, and bear immense psychological pressures, which affect their health outcomes. Olivera et al[12] showed that 39% of patients with non-traumatic hemorrhagic stroke suffer from anxiety disorders after stroke. Talmasov et al[13] pointed out that 15% of patients lack emotional and behavioral control at 21 months after a hemorrhagic stroke. This study showed that after the intervention, the observation group had less anxiety and depression (38.82 ± 3.67 points and 35.14 ± 2.75 points, respectively) than the control group (46.96 ± 5.12 points and 41.36 ± 3.71 points, respectively) and better psychological resilience (tenacity, self-improvement, and optimism) than the control group (P < 0.05). The results indicate that combining the Cox Health Behavior Interaction Model intervention with multifaceted psychological nursing can relieve patients’ anxiety and depression and improve their psychological resilience. This is because multifaceted psychological nursing emphasizes patients’ emotional support, assesses their psychological state at a specific time point, recognizes their inner thoughts, promotes communication among patients, increases patients’ confidence in treatment, reduces anxiety and depression, and improves their psychological resilience. Simultaneously, it promotes the role of family support, gives patients sufficient encouragement and support, eliminates their sense of loneliness, and relieves their treatment pressure. Based on the different psychological states of patients, individualized nursing interventions are adopted, which can help patients overcome their confidence in defeating the disease, enable them to accurately understand the disease and post-disease disability situation, improve their confidence in rehabilitation, and relieve negative emotions. The Cox Health Behavior Interaction intervention emphasizes patients’ internal motivation and self-responsibility awareness. Activities such as nurse-patient communication and patient-patient exchange meetings can improve the relationships between doctors, nurses, and patients, to establish a relationship of mutual trust and create a good hospital atmosphere, which can help relieve their fear and discomfort during the hospital stay and eliminate their negative emotions. At the same time, emotional support, psychological counseling, and targeted relief for patients can reduce the treatment pain and improve their energy status and psychological resilience. In addition, the support of relatives, friends, and fellow patients and the establishment of a health management plan can stimulate patients’ disease management awareness, increase their confidence in the treatment, and reduce their negative emotions[14]. Wei[15] also confirmed that using the Cox Health Interaction Behavior model can reduce the psychological stress response of patients with limb fractures and relieve their anxiety and depression.

Self-efficacy refers to an individual’s belief that they have sufficient ability and confidence to perform a certain behavior and achieve an expected result. The improvement in patients’ self-efficacy levels can promote patients’ confidence in the treatment and improve their mental state[16]. This study showed that the observation group had better self-efficacy after the intervention than the control group (P < 0.05). This indicates that the intervention of the Cox Health Behavior Interaction Model combined with multifaceted psychological nursing can improve patients’ self-efficacy. Multifaceted psychological nursing can relieve patients’ abnormal mental states and enable them to face the disease with a positive and optimistic outlook. Meanwhile, the Cox Health Behavior Interaction intervention can mobilize patients’ internal motivation and provide patients with an increased capacity for self-decision-making. Health information guidance and treatment feedback can further improve patients’ internal motivation and enhance their sense of self-efficacy.

This study showed that after the intervention, the observation group had a better quality of life related to physical, social, and mental health than the control group (P < 0.05). This indicates that reasonable and effective nursing interventions can improve the quality of life of patients. This is because multifaceted psychological nursing can reduce patients’ anxiety and depression and increase their confidence in disease treatments. Simultaneously, the Cox Health Behavior Interaction intervention corrects patients’ incorrect beliefs through nurse-patient communication and increases patients’ confidence in treatments using emotional support, which is conducive to the improvement of patients’ social and mental health. Furthermore, decision-making control helps establish healthy behaviors, transforms bad behaviors, and improves abnormal mental states, which is conducive to the improvement of patients’ self-decision-making ability. Professional skill guidance for patients enables them to face the disease and future life accurately, thus improving their physical health-related quality of life[17].

The present study had several limitations. First, the 12-week follow-up period may not have been sufficient to capture the long-term effects of the intervention or relapse rates of mental disorders in patients with hypertensive ICH. Prolonged monitoring over 6-12 months may provide more comprehensive insights into the sustained impact of combining the Cox Health Behavior Interaction Model with multifaceted psychological nursing. Second, this study adopted a single-center design with a relatively small sample size of 128 patients, which may have introduced regional or institutional biases and limited the generalizability of the findings. Third, the exclusion of patients with preexisting mental illnesses, such as schizophrenia or major depressive disorder, further restricts the applicability of the results to a broader patient population. Future studies should consider multicenter trials with larger sample sizes to enhance the external validity of these conclusions. Fourth, the study did not include blinding of participants or outcome assessors, which may have introduced bias, especially in the assessment of subjective outcomes, such as self-reported anxiety and depression levels. Finally, although the study measured various outcomes, it did not explore the underlying mechanisms of how the Cox model synergizes with psychological care, such as neurobiological pathways or specific behavioral changes. Further research is required to delve deeper into these aspects and better understand the interactions between the Cox model and psychological interventions.

The application of the Cox Health Behavior Interaction Model combined with multifaceted psychological nursing can relieve anxiety and depression in patients with hypertensive ICH complicated by mental disorders, improve their abnormal mental state, enhance their psychological resilience, increase their self-efficacy, and improve their quality of life, which is worthy of clinical application. However, the sample size was small and all participants were from the same hospital; thus, the restricted region and sample size may have introduced research biases. Subsequent research should expand the sample sources and increase the sample size to provide a reference basis for nursing interventions for patients with hypertensive ICH complicated by mental disorders.

| 1. | Yamada SM, Tomita Y, Iwamoto N, Takeda R, Nakane M, Aso T, Takahashi M. Subcortical hemorrhage caused by cerebral amyloid angiopathy compared with hypertensive hemorrhage. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2024;236:108076. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Tan H. The mediating role of anxiety in feelings of stigma and quality of life of post-epidemic hemiplegic patients with cerebral hemorrhage. J Clin Neurosci. 2023;112:12-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ozkan H, Ambler G, Banerjee G, Browning S, Leff AP, Ward NS, Simister RJ, Werring DJ. Prevalence, patterns, and predictors of patient-reported non-motor outcomes at 30 days after acute stroke: Prospective observational hospital cohort study. Int J Stroke. 2024;19:442-451. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Cross LA. Interaction Model of Client Health Behavior for Informal Caregivers: A Theoretical Analysis. Res Theory Nurs Pract. 2023;RTNP-2023. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Robles LA, Volovici V. Hypertensive primary intraventricular hemorrhage: a systematic review. Neurosurg Rev. 2022;45:2013-2026. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Cheng L, Gao W, Xu Y, Yu Z, Wang W, Zhou J, Zang Y. Anxiety and depression in rheumatoid arthritis patients: prevalence, risk factors and consistency between the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale and Zung's Self-rating Anxiety Scale/Depression Scale. Rheumatol Adv Pract. 2023;7:rkad100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Cao X, Feng M, Ge R, Wen Y, Yang J, Li X. Relationship between self-management of patients with anxiety disorders and their anxiety level and quality of life: A cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2023;18:e0284121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Qing Y, Bakker A, van der Meer CAI, Te Brake H, Olff M. Assessing psychological resilience: translation and validation of the Chinese version of the resilience evaluation scale (RES). Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2022;13:2133358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Hurst C, Rakkapao N, Malacova E, Mongkolsomlit S, Pongsachareonnont P, Rangsin R, Promsiripaiboon Y, Hartel G. Psychometric properties of the general self-efficacy scale among Thais with type 2 diabetes: a multicenter study. PeerJ. 2022;10:e13398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Legris N, Devilliers H, Daumas A, Carnet D, Charpy JP, Bastable P, Giroud M, Béjot Y. French validation of the Stroke Specific Quality of Life Scale (SS-QoL). NeuroRehabilitation. 2018;42:17-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Zhang YZ, Zhang CY, Tian YN, Xiang Y, Wei JH. Cerebral arterial blood flow, attention, and executive and cognitive functions in depressed patients after acute hypertensive cerebral hemorrhage. World J Clin Cases. 2024;12:3815-3823. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Olivera A, Ecker S, Lord A, Gurin L, Ishida K, Melmed K, Torres J, Zhang C, Frontera J, Lewis A. Factors Associated With Anxiety After Hemorrhagic Stroke. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2024;36:36-44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Talmasov D, Kelly S, Ecker S, Olivera A, Lord A, Gurin L, Ishida K, Melmed K, Torres J, Zhang C, Frontera J, Lewis A. Relationship Between Hemorrhage Type and Development of Emotional and Behavioral Dyscontrol After Hemorrhagic Stroke. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2024;36:316-324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Cho SJ, Kim SR, Cho KH, Shin NM, Oh WO. Effect of a Hospital-To-Home Transitional Intervention Based on an Interaction Model of Client Health Behavior for Adult Patients with Stroke. J Community Health Nurs. 2023;40:273-288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Wei G. Impact of the Interaction Model of Client Health Behavior on the Physical and Psychological Health of Patients with Limb Fracture. Iran J Public Health. 2022;51:2060-2068. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Lim WL, Koh YLE, Tan ZE, Tan YQ, Tan NC. Self-Efficacy in Patients With Hypertension and Their Perceived Usage of Patient Portals. J Prim Care Community Health. 2024;15:21501319231224253. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Pan X, Hu W, Wang Z, Fang Q, Xu L, Shen Y. Effect of self-regulating fatigue on health-related quality of life of middle-aged and elderly patients with recurrent stroke: a moderated sequential mediation model. Psychol Health Med. 2024;29:778-790. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |