Published online Sep 19, 2022. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v12.i9.1194

Peer-review started: March 10, 2022

First decision: April 18, 2022

Revised: April 27, 2022

Accepted: August 16, 2022

Article in press: August 16, 2022

Published online: September 19, 2022

Processing time: 193 Days and 23.7 Hours

This study examined the associations between social support and anxiety during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in an Israeli sample.

To examine the associations between social support and anxiety during the COVID-19 in an Israeli sample.

Data for this cross-sectional study were retrieved from an online survey. Linear regression, logistic regression and restricted cubic spline models were conducted to test for associations between social support and anxiety.

A total of 655 individuals took part in the present study. In the univariate linear regression model, there is a negative correlation between the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 score (GAD-7) and the Multidimensional Perceived Social Support Scale (MSPSS) score. For MSPSS score, the multivariable adjusted regression coefficient and 95% confidence interval (CI) of GAD-7 score were -0.779 (-1.063 to -0.496). In the univariate logistic regression model, there was a negative correlation between anxiety (GAD-7 ≥ 9) and MSPSS score, and there was still a negative correlation in multivariate logical regression analysis. The odds ratios and 95%CI were 0.709 (0.563-0.894).

Social support was inversely correlated with anxiety during COVID-19 in an Israeli sample.

Core Tip: Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a worldwide pandemic caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. Due to the massive spread and high infectivity of the virus, most countries have adopted various lockdown measures to control the epidemic. Anxiety disorder is one of the most common mental disorders. To examine the associations between social support and anxiety during the COVID-19 in an Israeli sample. A total of 655 individuals took part in the present study. Our results show that in the Israeli sample social support is negatively correlated with anxiety during COVID-19. This underscores the importance of social support for anxiety prevention during COVID-19 locking.

- Citation: Xi Y, Elkana O, Jiao WE, Li D, Tao ZZ. Associations between social support and anxiety during the COVID-19 lockdown in young and middle-aged Israelis: A cross-sectional study. World J Psychiatry 2022; 12(9): 1194-1203

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v12/i9/1194.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v12.i9.1194

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a worldwide pandemic caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. COVID-19 was first reported in Wuhan, China, causing pneumonia and other respiratory complications. Due to the massive spread and high infectivity of the virus, most countries have adopted various lockdown measures to control the epidemic. Changes in social distance and daily life activities during the blockade can affect personal well-being, mental health, and increase the risk of mental illness[1]. Anxiety disorder is one of the most common mental disorders.

Anxiety disorder is a common mental disorder with a global incidence of 7.3%[2]. Patients with anxiety disorders often feel excessive fear, anxiety or aim to avoid threats in the environment and within themselves, which can lead to disability and places a heavy burden on individuals and society[3]. Adequate social support is always significantly important for an individual’s mental health. There are no significant side effects associated with social support, as compared to typical drug therapy. In addition, social support is one of the social resources to deal with stressful life events[4]. Social support is defined as allowing individuals to take advantage of the positive effects of social interactions to directly protect their mental health and directly resist stressful situations. Social support, as a function of interpersonal emotion regulation, can reduce the risk of mental illness[5]. In a trial of 947 colorectal cancer patients in Spain, patients with more social support were more likely to have better results in anxiety and depression one year after surgery[6]. In patients with multiple sclerosis, higher social support was associated with lower depression and anxiety[7]. In a cross-sectional study of young pregnant women, pregnant adolescents with anxiety disorders were found to have less social support in all areas[8]. Similarly, adolescents’ exposure to negative life events was shown to be associated with social anxiety disorder, whereas changing social support can reduce anxiety symptoms in at-risk adolescents[4]. It is, thus, assumed that this inverse association exsits between the absence of social support and anxiety in different negative events and various populations.

It is not clear whether social support is equally protective of anxiety disorders in the context of the unique features of the first wave of COVID-19 pandemic in Israel in particular during lockdown. This study used data from an interim study on the lockdown enforced during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Israel to clarify the potential associations between social support and anxiety disorders.

The QualtricsXM platform (https://www.qualtrics.com/) digital questionnaire for data collection method was implemented in this study. It included a sociodemographic and personal questionnaire, the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7), the Multidimensional Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) and other measures and was administered using a snowball sampling method to recruit participants across Israel via email and mobile phone applications. All responses were anonymous. The responses to the questionnaire were collected from April 19 to May 2, 2020, when Israel was experiencing the peak of the first wave of the COVID-19 epidemic. During that time, the government imposed three weeks of strict lockdown measures, banning social gatherings. The experimental procedure was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Academic College of Tel-Aviv Yafo, Israel (Approval No. 2020085), and all participants an signed electronic informed consent, allowing access to the full set of questionnaires[9].

A total of 655 participants took part. 200 participants did not complete the questionnaire. Of these, 45% did not complete sociodemographic and personal questionnaire. Of the remaining 55% of participants, only 1.3% completed the GAD-7 questionnaire. Participants who failed to complete all the questionnaires were excluded. The inclusion criteria were over 18 years of age and fluent in Hebrew.

The demographic information included the participants’ age, gender, and socioeconomic status (based on question assessment of educational level, subjective perception of socioeconomic status, and financial resources for the next three months).

The GAD-7 is a self-reported anxiety questionnaire that can measure the anxiety level of the general population with sufficient validity and accuracy[10]. The Hebrew version was used, which contains 7 items, with scores ranging from 0 to 21. These scores represent 0-4 (minimal anxiety), 5-9 (mild anxiety), 10-14 (moderate anxiety), and 15-21 (severe anxiety). In this study, anxiety was defined as an overall score ≥ 9[11]. The internal consistency of the current sample was α = 0.892.

Social support was evaluated on the Hebrew version of the MSPSS, which assesses participants’ subjective feelings about their degree of social support[12]. The scale consists of three sub-scales related to family, friends, and significant others, with a total of 12 items. The higher the participants’ scores, the more social support they felt.

Covariates includes demographic variables (age, gender) and other background factors, including number of children, education, socioeconomic status, occupation, exercise and use of antidepressants.

SPSS 20.0 and R 3.5.1 were used for analysis. Linear regression was performed to analyze the association between social support and anxiety symptoms. Logistic regression was performed to examine the association between social support and anxiety disorders (GAD-7 score ≥ 9). To further investigate the relationship between social support and anxiety, a restricted cubic spline analysis was performed in the fully adjusted model. P values of less than 0.05 (two-tailed) were considered statistically significant.

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the 655 participants in terms of GAD-7 scores. The sample was composed of 246 men and 409 women, with a median age of 30. There were significant differences in age, gender, number of children, education, socioeconomic status, occupation, history of depression, and use of antidepressants between those with and without anxiety disorders (GAD-7 score ≥ 9). Those classified as exhibiting anxiety were younger than those who were classified as not exhibiting anxiety. Anxiety was also more common among women. Of the participants classified as anxious, 80% had no children, 50% had a bachelor’s degree, 41.1% had an average economic status and 54.2% had a full-time or part-time job.

| Variable | Total (n = 655) | GAD-7 score < 9 (n = 585) | GAD-7 score ≥ 9 (n = 70) | P value |

| Age (yr) | 30 (26-47) | 31 (26-49) | 27 (23-33) | < 0.001 |

| Gender | 0.007 | |||

| Male | 246 (37.6%) | 230 (39.3%) | 16 (22.9%) | |

| Female | 409 (62.4%) | 355 (60.7%) | 54 (77.1%) | |

| Number of children | 0.008 | |||

| Zero | 392 (59.8%) | 336 (57.4%) | 56 (80.0%) | |

| One | 37 (5.6%) | 34 (5.8%) | 3 (4.3%) | |

| Two | 95 (14.5%) | 91 (15.6%) | 4 (5.7%) | |

| Three | 100 (15.3%) | 94 (16.1%) | 6 (8.6%) | |

| Four | 31 (4.7%) | 30 (5.1%) | 1 (1.4%) | |

| Education | 0.003 | |||

| Without diploma | 23 (3.5%) | 21 (3.6%) | 2 (2.9%) | |

| 12 years or less | 125 (19.1%) | 102 (17.4%) | 23 (32.9%) | |

| Bachelor | 295 (45.0%) | 260 (44.4%) | 35 (50.0%) | |

| Master (or higher) | 187 (28.5%) | 178 (30.4%) | 9 (12.9%) | |

| Other | 25 (3.8%) | 24 (4.1%) | 1 (1.4%) | |

| Socio-economic status | < 0.001 | |||

| Low | 21 (3.2%) | 16 (2.7%) | 5 (7.1%) | |

| Low-average | 79 (2.1%) | 60 (10.3%) | 19 (27.1%) | |

| Average | 281 (42.9%) | 252 (43.1%) | 29 (41.1%) | |

| Average-high | 224 (34.2%) | 209 (35.7%) | 15 (21.4%) | |

| High | 50 (7.6%) | 48 (8.2%) | 2 (2.9%) | |

| Occupation | 0.029 | |||

| Full-time job | 280 (42.7%) | 261 (44.6%) | 19 (27.1%) | |

| Partially employed | 109 (16.6%) | 90 (15.4%) | 19 (27.1%) | |

| Unpaid vacation | 4 (0.6%) | 4 (0.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Lost job | 33 (5.0%) | 31 (5.3%) | 2 (2.9%) | |

| Unemployed | 55 (8.4%) | 47 (8.0%) | 8 (11.4%) | |

| Retired | 174 (26.6%) | 152 (26.0%) | 22 (31.4%) | |

| Exercise | 0.112 | |||

| Yes | 190 (29.0%) | 164 (28.0%) | 26 (37.1%) | |

| No | 465 (71.0%) | 421 (72.0%) | 44 (62.9%) | |

| History of depression | < 0.001 | |||

| Yes | 538 (82.1%) | 494 (84.4%) | 44 (62.9%) | |

| No | 117 (17.9%) | 91 (15.6%) | 26 (37.1%) | |

| Use of antidepressants | 0.001 | |||

| Yes | 563 (86.0%) | 512 (87.5%) | 51 (72.9%) | |

| No | 92 (14.0%) | 73 (12.5%) | 19 (27.1%) | |

| MSPSS score | 6.08 (5.25-6.67) | 6.08 (5.33-6.75) | 5.75 (4.67-6.50) | 0.009 |

| GAD-7 score | 3 (1-6) | 3 (1-5) | 13 (11-15) | < 0.001 |

Table 2 uses linear regression to analyze the association between social support and anxiety symptoms. In the univariate linear regression model, GAD-7 score was negatively correlated with MSPSS score, and the regression coefficient and 95% confidence interval (CI) were -0.692 (-0.990 to -0.394). Further multivariate linear regression analysis showed that there was still a negative correlation between GAD-7 score and MSPSS score, and the regression coefficient and 95%CI was -0.779 (-1.063 to -0.496). This negative correlation was independent of age, sex, socio-economic status and the use of antidepressants.

| Variable | Univariate linear regression | Multivariate linear regression | ||

| β (95%CI) | P value | β (95%CI) | P value | |

| MSPSS | -0.692 (-0.990, -0.394) | < 0.001 | -0.779 (-1.063, -0.496) | < 0.001 |

| Age | -0.056 (-0.077, -0.035) | < 0.001 | -0.048 (-0.068, -0.028) | < 0.001 |

| Sex | 1.888 (1.246, 2.529) | 0.316 | 1.641 (1.021, 2.261) | < 0.001 |

| Number of children | -0.524 (-0.760, -0.289) | < 0.001 | - | - |

| Education | -0.399 (-0.763, -0.034) | 0.032 | - | - |

| Occupation | 0.142 (-0.006, 0.289) | 0.059 | - | - |

| Socio-economic status | -0.952 (-1.300, -0.603) | < 0.001 | -0.514 (-0.854, -0.174) | 0.003 |

| Exercise | -0.460 (-1.162, 0.241) | 0.198 | - | - |

| Use of antidepressants | 2.589 (1.781, 3.397) | < 0.001 | 2.046 (1.279, 2.813) | < 0.001 |

Table 3 shows the odds ratios (OR) and the 95%CI for social support and anxiety disorders (GAD-7 score ≥ 9). In the univariate logistic regression model, the occurrence of anxiety was negatively correlated with MSPSS score. Multivariate logical regression analysis with backward method showed that the occurrence of anxiety was still negatively correlated with MSPSS score, and the OR and 95%CI were 0.709 (0.563-0.894). This negative correlation is independent of gender, age, education level, socio-economic status and the use of antidepressants.

| Variable | Univariate logistic regression | Multivariate logistic regression | ||

| OR (95%CI) | P value | OR (95%CI) | P value | |

| MSPSS | 0.747 (0.605, 0.921) | 0.006 | 0.709 (0.563, 0.894) | 0.004 |

| Age | 0.965 (0.944, 0.986) | 0.001 | 0.976 (0.953, 0.999) | 0.041 |

| Sex | 2.187 (1.222, 3.913) | 0.008 | 2.151 (1.142, 4.053) | 0.018 |

| Number of children | 0.658 (0.514, 0.842) | 0.001 | - | - |

| Education | 0.617 (0.464, 0.822) | 0.001 | 0.615 (0.445, 0.851) | 0.003 |

| Occupation | 1.096 (0.980, 1.227) | 0.109 | - | - |

| Socio-economic status | 0.539 (0.409, 0.710) | < 0.001 | 0.628 (0.465, 0.849) | 0.003 |

| Exercise | 0.659 (0.393, 1.106) | 0.114 | - | - |

| Use of antidepressants | 2.613 (1.461, 4.672) | 0.001 | 2.588 (1.384, 4.841) | 0.004 |

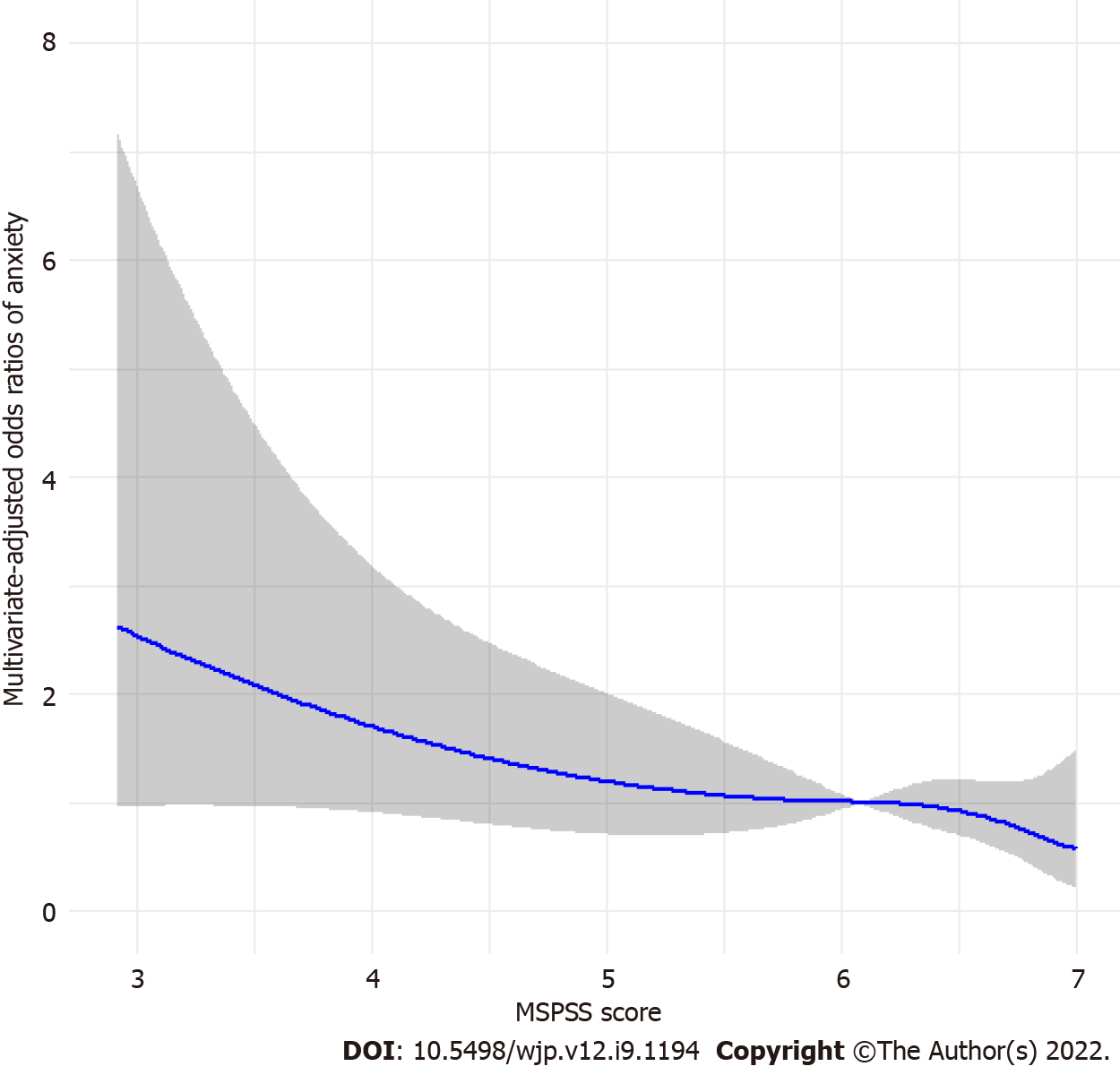

To further clarify the relationship, a restricted cubic spline analysis was used to analyze the association between social support and anxiety (Figure 1). The results showed that social support was inversely correlated with anxiety symptoms (GAD-7 score ≥ 9). Anxiety symptoms decreased with increasing social support scores.

In this study, a cross-sectional analysis was conducted using data from an interim study conducted while Israel was in lockdown during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic to assess the relationship between social support and anxiety symptoms. The data included 655 participants. The results showed that participants’ social support scores were inversely correlated with GAD-7 scores. Social support was inversely associated with anxiety (GAD-7 score ≥ 9) in logistic regression model, and this negative correlation is independent of gender, age, education level, socio-economic status and the use of antidepressants.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, people in most countries were placed under tight lockdown measures due to the dangers of the rapid spread of the disease and the severe shortage of medical resources. In instances of insufficient supply and personnel, medical workers tend to give priority to serious physical diseases and ignore patients’ mental symptoms[13]. At the same time, for quarantined individuals, the panic caused by the COVID-19 outbreak, as well as the economic losses caused by the lockdown, the lack of protective gear and other complications all exacerbated the psychological difficulties. In an epidemiological survey conducted in Hong Kong, 25.4% of the population’s mental health was reported to have deteriorated since the outbreak of COVID-19, and 14% of the population suffers from anxiety[14]. Anxiety is an emotion characterized by physical changes such as tension, anxious thoughts and elevated blood pressure, with a lifetime prevalence rate of more than 20%[15]. When severe acute respiratory syndrome broke out in Hong Kong in 2013, 13% of the population developed anxiety disorders after discharge from hospital[16]. Anxiety disorders often occur at the same time as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Pre-existing anxiety has been proved to be a risk factor for the development of urban population into PTSD[17]. Studies have shown that participants with higher symptoms of depression and anxiety are more likely to develop more severe PTSD symptoms, and higher social support may be associated with lower PTSD[18].

Social support, as a way to foster a sense of belonging and love, is crucial for the mental health of the population. Social support can promote mental health in several ways. First social support can enable people receive more information and care from others. Certain specific groups, such as pregnant and postpartum mothers and parents of young children with special medical needs can obtain social support from social media to relieve negative emotions such as psychological anxiety and glean useful suggestions[19,20]. During the lockdown period, people mainly used social media to get social support from a range of sources to ease anxiety and fight the epidemic collectively. Second, social support can alleviate people’s pain, and can encourage physical activity, including those who are physically limited by pain, and thus have a positive impact on people’s health behaviors[21]. Finally, social support can improve individuals’ physical condition and promote mental health by directly influencing the body’s pathophysiological mechanisms. Studies have found that people with higher social support and integration have lower mortality rates, and a comprehensive meta-analysis has shown that social support is inversely correlated with inflammation levels in vivo[22]. In addition, social support can significantly reduce the cardiovascular response of the population and lower cardiovascular recovery to its pre-stress level[23]. All these studies thus suggest that social support not only provides information and care from the outside world, but also modulates the mental health of the population by reducing physical pain and improving inflammation levels.

In a cross-sectional study of women who had undergone a therapeutic abortion, more than half reported symptoms of anxiety, and social support from these women’s family and friends significantly reduced anxiety levels. Furthermore, social support from partners can also reduce women’s anxiety symptoms[24]. Another longitudinal cohort study of caregivers of patients diagnosed with cancer showed that accurate information and social support from other members of the community, as well as physical activity reduced anxiety in partners in the first months after a cancer diagnosis[25]. These epidemiological studies underscore the positive effects of social support on anxiety disorders. Similarly, during the special period of COVID-19’s outbreak, in a cross-sectional survey of 3500 Spanish adults, it was found that for those without pre-pandemic mental disorders, higher levels of social support decreased the odds of GAD-7[26]. During the COVID-19 pandemic in Turkey, it was also found that anxiety levels decreased significantly when perceived social support increased[4]. This study conducted a survey during Israel’s first blockade in 2020, taking into account the effects of age, sex, number of children, education level, socio-economic status, occupation, exercise and antidepressant use, the results here show that social support is negatively correlated with post-blockade anxiety.

This study makes several contributions beyond its limitations. Using data collected during the first wave of COVID-19 lockdown in Israel, this study reports on relationship between social support and anxiety during COVID-19 lockdown. In addition, we considered the impact of confounding factors such as age, gender, education, socioeconomic status and other potential influences. Note, however, that the cross-sectional design of this study is a major limitation because it is difficult to make causal inferences. Second, the results were adjusted for a variety of major potential confounding factors; however, the existence of unmeasured factors and some unknown factors cannot be ruled out. Third, randomly distributed questionnaires may lead to age selection bias of the study population, which may make the results not generalized. Fourth, this study does not include the limitations on generalization to younger and older ages. Fifth, this study does not include people who have been infected with COVID-19, whether infected with COVID-19 may have an impact on the correlation coefficient between social support and anxiety.

Prolonged home confinement may be the main reason that affects people’s mental health during the blockade of the COVID-19 pandemic, and it is very important to give proper physical and mental care and social support. In addition, the long epidemic period of COVID-19 and the continuous mutation of virus strains undoubtedly bring new challenges to people’s mental health. How to make rational use of multimedia or the internet to improve the psychological state of the population during the COVID-19 blockade is a research direction worthy of attention for future researchers.

Overall our findings suggest that social support was inversely associated with anxiety symptoms during COVID-19 pandemic lockdown. Thus providing social support may reduce the prevalence of anxiety in the population.

Due to the massive spread and high infectivity of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), most countries have adopted various lockdown measures to control the epidemic. Changes in social distance and daily life activities during the blockade can affect personal well-being, mental health, and increase the risk of mental illness. Anxiety disorder is one of the most common mental disorders.

It is not clear whether social support is equally protective of anxiety disorders in the context of the unique features of the first wave of COVID-19 pandemic in Israel in particular during lockdown. This study used data from an interim study on the lockdown enforced during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Israel to clarify the potential associations between social support and anxiety disorders.

The purpose of this study was to study the relationship between social support and anxiety in Israelis during the first COVID-19 epidemic.

Data for this cross-sectional study were retrieved from an online survey. Linear regression, logistic regression and restricted cubic spline models were conducted to test for associations between social support and anxiety.

A total of 655 individuals took part in the present study. In the univariate linear regression model, there is a negative correlation between the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 score (GAD-7) and the Multidimensional Perceived Social Support Scale (MSPSS) score. For MSPSS score, the multivariable adjusted regression coefficient and 95% confidence interval (CI) of GAD-7 score were -0.779 (-1.063 to -0.496). In the univariate logistic regression model, there was a negative correlation between anxiety (GAD-7 ≥ 9) and MSPSS score, and there was still a negative correlation in multivariate logical regression analysis. The odds ratios and 95%CI were 0.709 (0.563-0.894).

Social support was inversely correlated with anxiety during COVID-19 in an Israeli sample.

Our findings suggest that social support was inversely associated with anxiety symptoms during COVID-19 pandemic lockdown. Thus providing social support may reduce the prevalence of anxiety in the population.

We thank all the individuals responsible for the planning and administering of the CLHLS and making the datasets of CLHLS available on their website. We are grateful to the reviewers for their useful comments.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Psychiatry

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Goldstein Ferber S, Israel; Lelisho ME, Ethiopia S-Editor: Wang JJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Wang JJ

| 1. | Ortenburger D, Mosler D, Pavlova I, Wąsik J. Social Support and Dietary Habits as Anxiety Level Predictors of Students during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Baxter AJ, Scott KM, Vos T, Whiteford HA. Global prevalence of anxiety disorders: a systematic review and meta-regression. Psychol Med. 2013;43:897-910. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1082] [Cited by in RCA: 890] [Article Influence: 68.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Baxter AJ, Vos T, Scott KM, Ferrari AJ, Whiteford HA. The global burden of anxiety disorders in 2010. Psychol Med. 2014;44:2363-2374. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 379] [Cited by in RCA: 421] [Article Influence: 35.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Özmete E, Pak M. The Relationship between Anxiety Levels and Perceived Social Support during the Pandemic of COVID-19 in Turkey. Soc Work Public Health. 2020;35:603-616. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Viseu J, Leal R, de Jesus SN, Pinto P, Pechorro P, Greenglass E. Relationship between economic stress factors and stress, anxiety, and depression: Moderating role of social support. Psychiatry Res. 2018;268:102-107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Gonzalez-Saenz de Tejada M, Bilbao A, Baré M, Briones E, Sarasqueta C, Quintana JM, Escobar A; CARESS-CCR Group. Association between social support, functional status, and change in health-related quality of life and changes in anxiety and depression in colorectal cancer patients. Psychooncology. 2017;26:1263-1269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ratajska A, Glanz BI, Chitnis T, Weiner HL, Healy BC. Social support in multiple sclerosis: Associations with quality of life, depression, and anxiety. J Psychosom Res. 2020;138:110252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Peter PJ, de Mola CL, de Matos MB, Coelho FM, Pinheiro KA, da Silva RA, Castelli RD, Pinheiro RT, Quevedo LA. Association between perceived social support and anxiety in pregnant adolescents. Braz J Psychiatry. 2017;39:21-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Oryan Z, Avinir A, Levy S, Kodesh E, Elkana O. Risk and protective factors for psychological distress during COVID-19 in Israel. Curr Psychol. 2021;1-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Löwe B, Decker O, Müller S, Brähler E, Schellberg D, Herzog W, Herzberg PY. Validation and standardization of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener (GAD-7) in the general population. Med Care. 2008;46:266-274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1978] [Cited by in RCA: 3032] [Article Influence: 168.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1092-1097. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11947] [Cited by in RCA: 20556] [Article Influence: 1027.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Johnston L, Steinhaus M, Sass J, Benjarattanaporn P, Sirinirund P, Siraprapasiri T, Gass R. The Associations of Perceived Social Support with Key HIV Risk and Protective Factors Among Young Males Who Have Sex with Males in Bangkok and Chiang Mai, Thailand. AIDS Behav. 2018;22:1899-1907. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Arya A, Buchman S, Gagnon B, Downar J. Pandemic palliative care: beyond ventilators and saving lives. CMAJ. 2020;192:E400-E404. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 19.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Choi EPH, Hui BPH, Wan EYF. Depression and Anxiety in Hong Kong during COVID-19. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 563] [Cited by in RCA: 486] [Article Influence: 81.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Singh R, Singh B, Mahato S, Hambour VK. Social support, emotion regulation and mindfulness: A linkage towards social anxiety among adolescents attending secondary schools in Birgunj, Nepal. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0230991. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Wu KK, Chan SK, Ma TM. Posttraumatic stress after SARS. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:1297-1300. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Hatch R, Young D, Barber V, Griffiths J, Harrison DA, Watkinson P. Anxiety, Depression and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder after critical illness: a UK-wide prospective cohort study. Crit Care. 2018;22:310. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 174] [Cited by in RCA: 327] [Article Influence: 40.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Xi Y, Yu H, Yao Y, Peng K, Wang Y, Chen R. Post-traumatic stress disorder and the role of resilience, social support, anxiety and depression after the Jiuzhaigou earthquake: A structural equation model. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;49:101958. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Baker B, Yang I. Social media as social support in pregnancy and the postpartum. Sex Reprod Healthc. 2018;17:31-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 15.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | DeHoff BA, Staten LK, Rodgers RC, Denne SC. The Role of Online Social Support in Supporting and Educating Parents of Young Children With Special Health Care Needs in the United States: A Scoping Review. J Med Internet Res. 2016;18:e333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Stevens M, Cruwys T, Murray K. Social support facilitates physical activity by reducing pain. Br J Health Psychol. 2020;25:576-595. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Uchino BN, Trettevik R, Kent de Grey RG, Cronan S, Hogan J, Baucom BRW. Social support, social integration, and inflammatory cytokines: A meta-analysis. Health Psychol. 2018;37:462-471. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Christenfeld N, Gerin W. Social support and cardiovascular reactivity. Biomed Pharmacother. 2000;54:251-257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Akdag Topal C, Terzioglu F. Assessment of depression, anxiety, and social support in the context of therapeutic abortion. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2019;55:618-623. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | García-Torres F, Jacek Jabłoński M, Gómez Solís Á, Moriana JA, Jaén-Moreno MJ, Moreno-Díaz MJ, Aranda E. Social support as predictor of anxiety and depression in cancer caregivers six months after cancer diagnosis: A longitudinal study. J Clin Nurs. 2020;29:996-1002. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Monistrol-Mula A, Felez-Nobrega M, Domènech-Abella J, Mortier P, Cristóbal-Narváez P, Vilagut G, Olaya B, Ferrer M, Gabarrell-Pascuet A, Alonso J, Haro JM. The impact of COVID-related perceived stress and social support on generalized anxiety and major depressive disorders: moderating effects of pre-pandemic mental disorders. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2022;21:7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |