Published online Dec 9, 2025. doi: 10.5492/wjccm.v14.i4.111260

Revised: July 23, 2025

Accepted: October 17, 2025

Published online: December 9, 2025

Processing time: 155 Days and 15.8 Hours

Analgesia and sedation are commonly prescribed therapies within the intensive care unit (ICU) for patients receiving mechanical ventilation. Current guidelines recommend utilizing an analgesia-first approach to initially reach appropriate pain control, while potentially achieving sedation goals concurrently. Our system employs a guideline-based ICU sedation order-set that features an electronic medical record (EMR) integrated ICU checklist that combines analgesia and sedation.

To identify systems-based factors that are associated with the use of continuous midazolam infusion administration in mechanically ventilated patients.

We extracted EMR data from patients who received mechanical ventilation between January 1, 2021, and December 31, 2023. Subjects included were 18 years or older who received mechanical ventilation. “R” version 4.3.2 was used for data processing and statistical analysis. We performed a multivariable regression analysis to predict the administration of a continuous midazolam infusion with modified Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score, Charlson comorbidity index, and critical care medicine (CCM) primary service.

Of 3805 patients that underwent mechanical ventilation, 62% were male, with a mean age of 66.9 years. 3429 patients were treated by a provider team with a CCM attending, and 376 patients were managed by a non-CCM primary team with CCM consultative services. A midazolam infusion was used in 187 of 3429 (5%) patients with CCM as primary and in 166 of 376 (56%) patients with non-CCM primary (χ2 598.23, P < 0.001). Of the patients who received continuous midazolam, 117 (21%) died vs 236 (7%) survived hospitalization. Continuous midazolam was associated with more days with coma and more days with delirium (P < 0.0001).

Continuous midazolam infusion was more likely in patients admitted to the ICU under an open unit with a non-CCM physician with an intensivist consult available, despite guided order-sets and checklists integrated into the EMR.

Core Tip: Advancements have been made to improve outcomes among critically ill patients admitted to the intensive care units. Our study outlines the importance of adhering to guideline-based therapy when it comes to sedation, which is more commonly done in an intensivist staffing model. The choice of sedation has a strong impact on the overall care of the patient during their intensive care unit stay as well as the recovery period after they are discharged from the hospital.

- Citation: Nestoiter KG, Feick K, Looney K, Zaccheo M, Wert Y, Franz C. Critical care primary services are associated with reduced midazolam use in the intensive care unit. World J Crit Care Med 2025; 14(4): 111260

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3141/full/v14/i4/111260.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5492/wjccm.v14.i4.111260

Analgesia and sedation are two core components within the intensive care unit (ICU) that significantly impact patient outcomes. Patients often require analgesia and sedation in the ICU for treatment of pain, assistance in mechanical ventilation, and management of agitation. The choice of medications and target sedation level can affect how long patients remain on mechanical ventilation and their stay in the hospital. Recent guidelines have recommended using opioid based analgesia, both non-pharmacologic and pharmacologic options, to treat patients’ pain in the ICU[1]. Additionally, intravenous opioids are recommended as the preferred agents for analgesia in mechanically ventilated patients with adjunctive agents such as acetaminophen or neuropathic agents, depending on the patient scenario[1]. As for sedation, propofol and dexmedetomidine are preferred over benzodiazepines to target a light level of sedation[1]. Recognizing that pain can go untreated, which can lead to agitation or delirium, the guidelines recommend a standard practice of analgesia first, then sedation, coined “analgosedation”[1].

Delirium is an independent predictor of morbidity and mortality in the ICU, and for each additional day a patient in the ICU spends in delirium, there is a 10% increased risk of death[2]. Delirium that persists for 2 or more days increases absolute mortality[3]. In addition to delirium being detrimental to patient outcomes, it carries a high-cost burden on the United States health system. Benzodiazepines are a known risk factor for ICU delirium[4]. Benzodiazepines provide deeper levels of sedation while increasing mechanical ventilation days, hospital, and ICU length of stay, and delirium in the landmark trials for ICU patients[5-7]. When comparing benzodiazepines to other sedatives, the MENDS trial indicated that dexmedetomidine had statistically significantly more days alive without delirium or coma when compared to lorazepam[6]. In that trial, providers were more successful in achieving their goal of sedation level with dex

The ICU triad of delirium, pain, and agitation increases the morbidity of patients in the ICU[9]. Physicians should strive to address all three in a coordinated effort to achieve better outcomes and to minimize delirium[9]. Since benzo

We performed a retrospective observational study aimed to identify risk factors for guideline-inconsistent continuous sedation in patients admitted to our hospital system’s ICUs between January 1, 2021 and December 31, 2023. Our institution comprises seven hospitals, eight ICUs, five of which are teaching institutions. We queried the patients who were admitted to any of the seven hospitals in our Central Pennsylvania hospital system that underwent mechanical ventilation. We assessed receipt of the following continuous infusions during the ICU admission: Fentanyl, propofol, midazolam, dexmedetomidine, ketamine, and hydromorphone.

We obtained order details, including the date and time of the initial order and the ordering provider’s specialty. Data was extracted from order history, flowsheets, vital signs, demographics, and laboratory results. Sedative infusion administration was compared against the current 2018 Society for Critical Care Medicine practice guidelines[1] and our institution’s ICU sedation protocol. We classified patients as having received either guideline-consistent or inconsistent sedation according to the 2018 Society for Critical Care Medicine guidelines and the order of sedative infusion initiation. We identified patient factors [e.g., age, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score, admission diagnosis] and system factors (e.g., teaching vs non-teaching, critical care vs non-critical care ordering provider) that are associated with guideline-inconsistent sedative use.

Inclusion criteria: Subjects 18 years old or older who were admitted to the ICU between January 1, 2021 and December 31, 2023, and who were administered any of the following continuous sedatives during mechanical ventilation (fentanyl, propofol, midazolam, dexmedetomidine, ketamine, and hydromorphone). We included patients who were documented in a comatose state using the Riker Sedation-Agitation Scale (RSAS), with a score of 1 or 2. The RSAS score was obtained from the nursing flowsheets, and we used the first score after sedation was started.

We excluded patients who were younger than 18 years old, patients who were placed on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, and patients who were not receiving mechanical ventilation.

Primary outcome: Our primary outcome was the percentage of ICU patients who received continuous midazolam infusion between critical care and non-critical care providers, and between teaching and non-teaching ICU settings. We hypothesized that patients under the care of an intensivist were less likely to receive midazolam infusion.

Secondary outcome: Our secondary outcome was to compare predetermined baseline characteristics and to identify systems-based factors that are associated with guideline-inconsistent ICU sedation practices between our ICUs, defined as the use of continuous midazolam infusion without a trial of analgesia in mechanically ventilated patients.

Normality tests of continuous variables were performed with the Shapiro-Wilk test. Variables with normal distribution were reported as mean, standard deviation, and range. Variables with non-normal distribution were presented as median (interquartile range). The student’s t-test or two-sample Wilcoxon test was used to analyze group differences for the continuous variables. Categorical variables, expressed as numbers and percentages, were compared using the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test. A multiple logistic regression model was developed to identify significant factors associated with the use of continuous midazolam infusion. Odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals were reported for each independent variable. A P-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Missing data was imputed with multiple imputations of chained equations. All the analyses were done by R (version 4.3.2) and SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, United States).

This study is at risk for selection bias and other confounding variables, given the retrospective nature of the study.

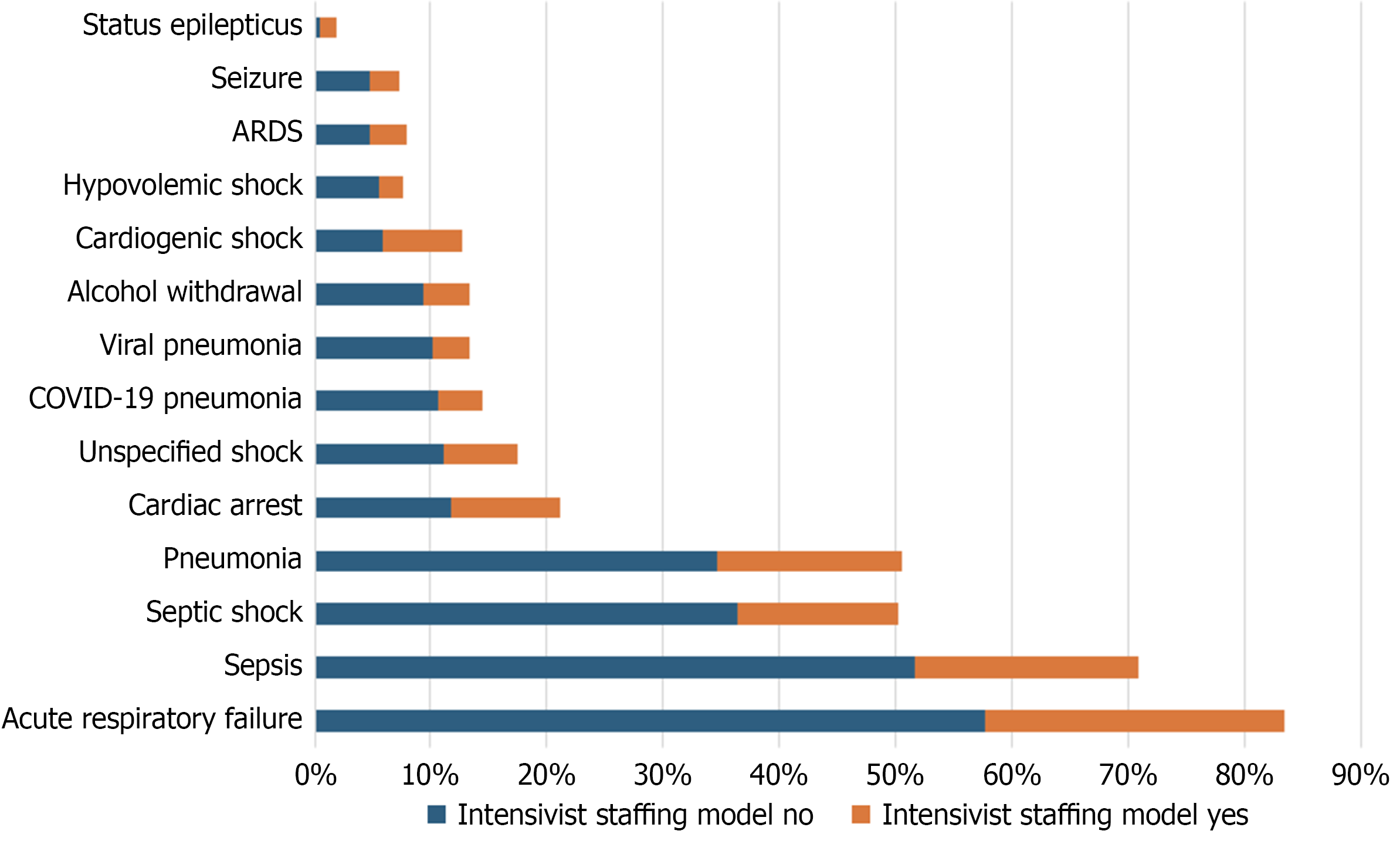

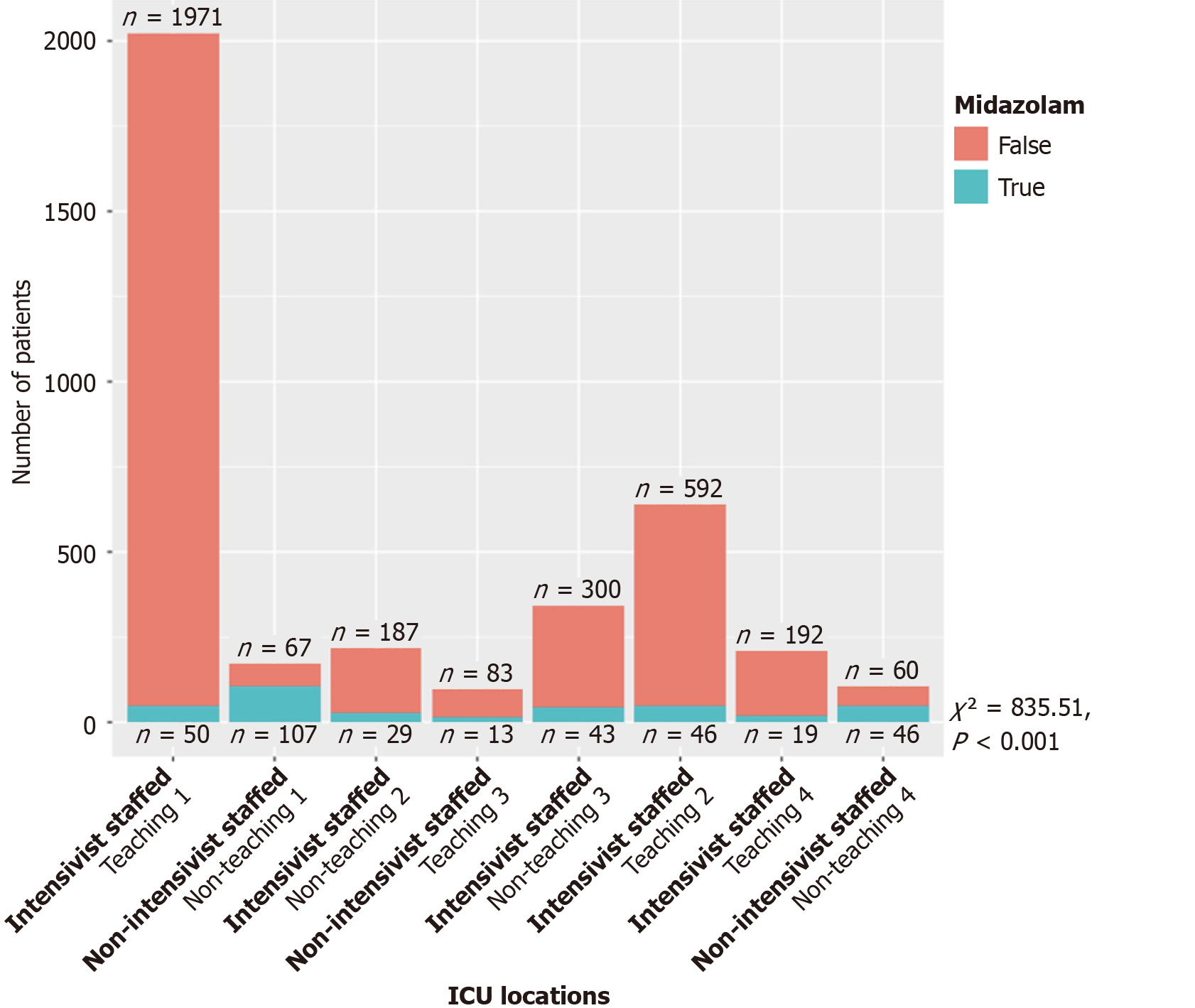

We identified 3805 patients during the treatment period, with 3429 patients (90%) treated under a critical care attending physician (intensivist staffing model or CCM), and 376 patients (10%) were treated under a non-critical care attending physician with the availability of consultation from an intensivist. Of the patient sample, 62.9% were male gender in the intensivist staffing model, with a mean age of 65.8 years (Standard deviation 12.9); the non-intensivist staffing model had 55.6% male patients with a mean age of 68.1 years (Standard deviation 13.9) (Table 1). There was a difference in the Charlson Comorbidity index between the two groups, with the Charlson Comorbidity Index being slightly higher in the non-intensivist staffing group (t-test = 4.03, P < 0.001). Likewise, the SOFA score was marginally higher in the non-intensivist staffing group (t-test = 3.85, P < 0.001). The absolute mortality was higher in the non-intensivist staffing model. Table 1 also demonstrates the list of common diagnoses admitted to the ICU in our cohort. This data is also demonstrated graphically in Figure 1.

| Intensivist staffing model | ||

| No | Yes | |

| Number patients | 376.0 | 3429.0 |

| Number of males | 209.0 | 2156.0 |

| Percent males | 55.6 | 62.9 |

| Mean age (years) | 68.1 | 65.8 |

| Age (SD, deviation) | 13.9 | 12.9 |

| Mean weight (kg) | 90.5 | 88.8 |

| Weight (SD, deviation) | 27.3 | 24.1 |

| Charlson comorbidity index (mean ± SD) | 6.0 | 5.6 |

| Charlson comorbidity index (SD, deviation) | 2.8 | 2.8 |

| Sofa score (mean ± SD) | 7.9 | 6.8 |

| Sofa score (SD, deviation) | 2.5 | 2.6 |

| Hospital mortality | 26.1 | 13.2 |

| Hospital diagnoses | ||

| Acute respiratory failure | 217 (58) | 883 (26) |

| Sepsis | 194 (52) | 660 (19) |

| Septic shock | 137 (36) | 471 (14) |

| Pneumonia | 130 (35) | 549 (16) |

| Cardiac arrest | 44 (12) | 322 (9) |

| Unspecified shock | 42 (11) | 214 (6) |

| COVID-19 pneumonia | 40 (11) | 130 (4) |

| Viral pneumonia | 38 (10) | 109 (3) |

| Alcohol withdrawal | 35 (9) | 136 (4) |

| Cardiogenic shock | 22 (6) | 233 (7) |

| Hypovolemic shock | 21 (6) | 70 (2) |

| ARDS | 18 (5) | 110 (3) |

| Seizure | 18 (5) | 88 (3) |

| Status epilepticus | 2 (1) | 47 (1) |

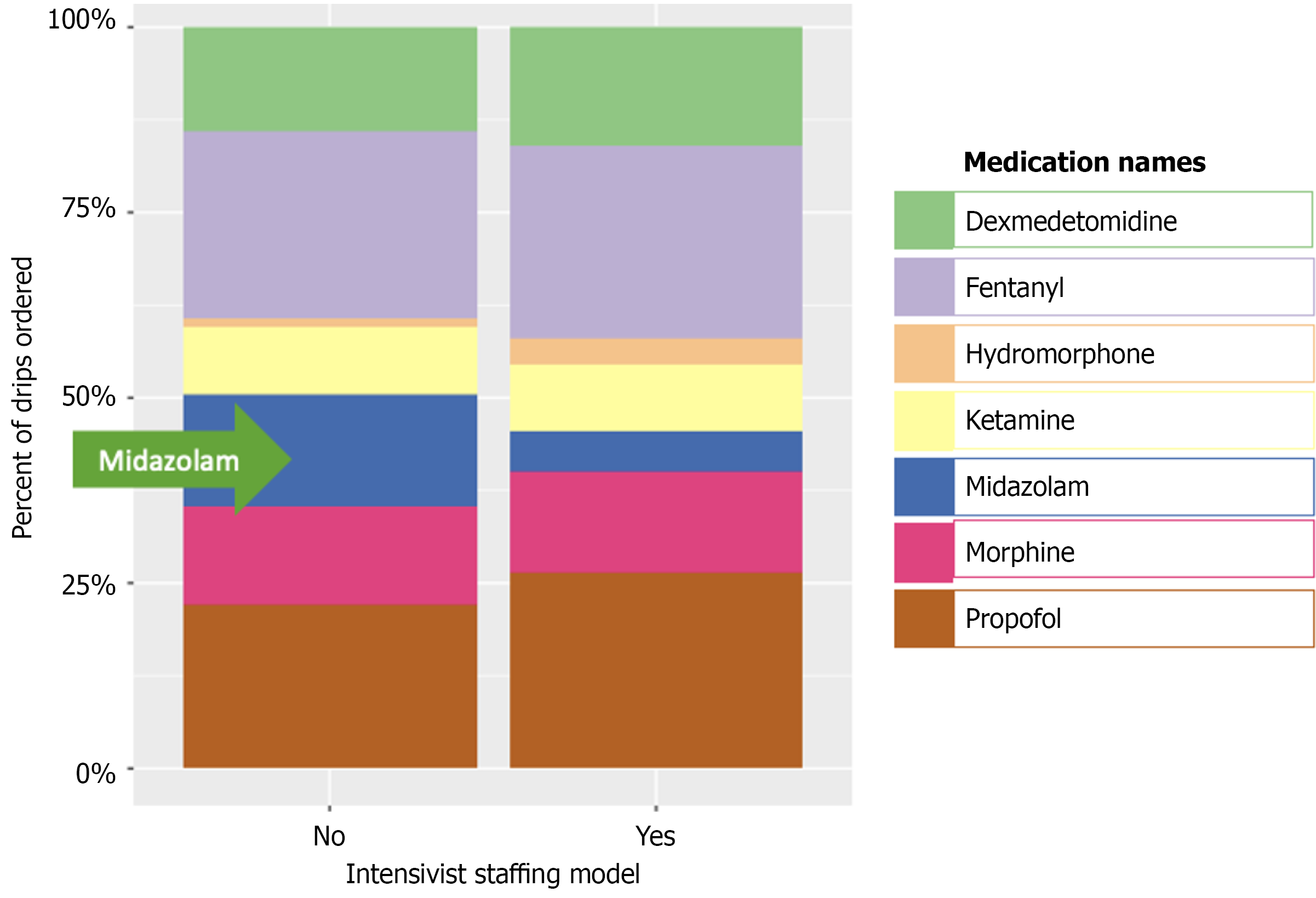

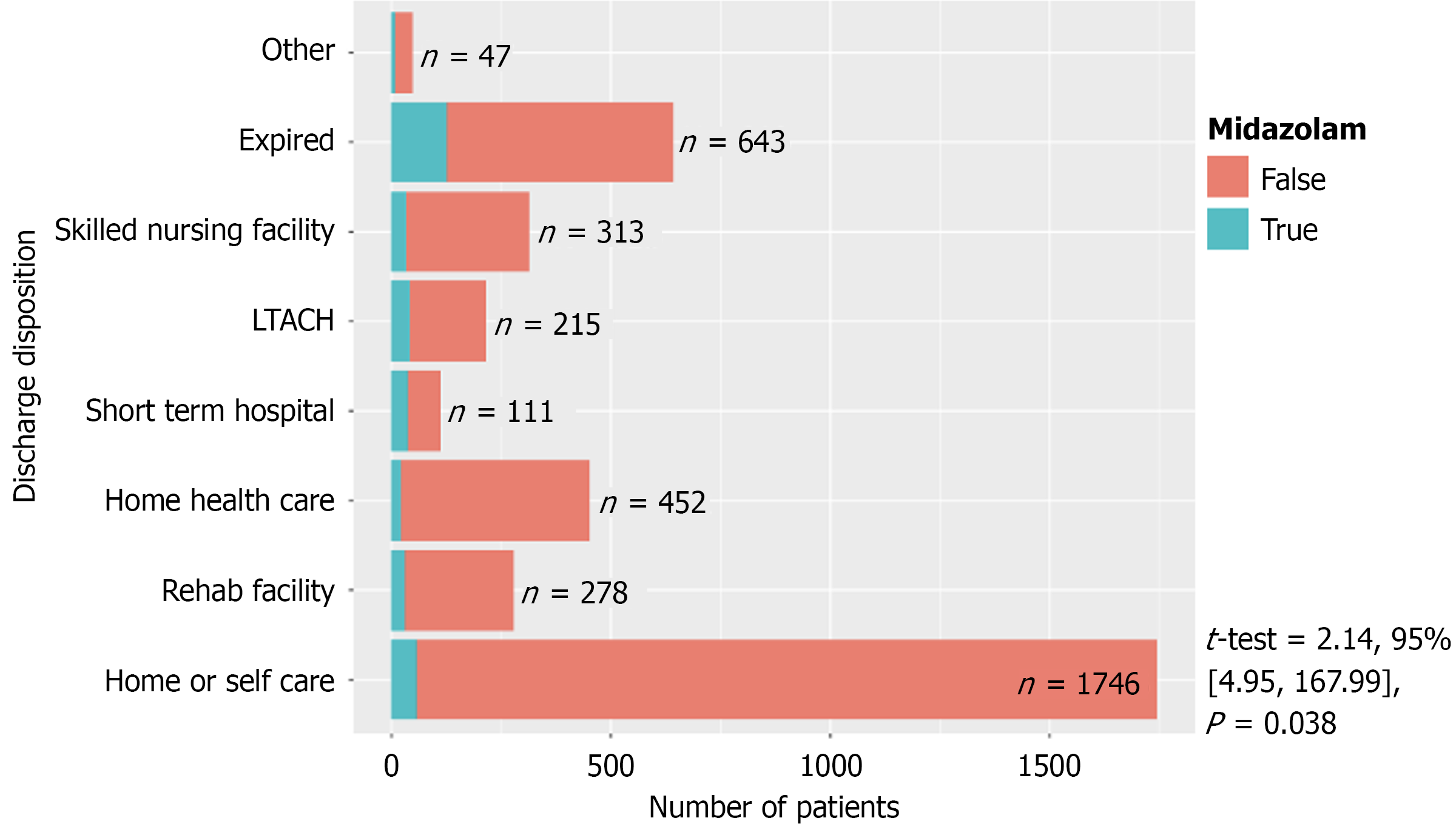

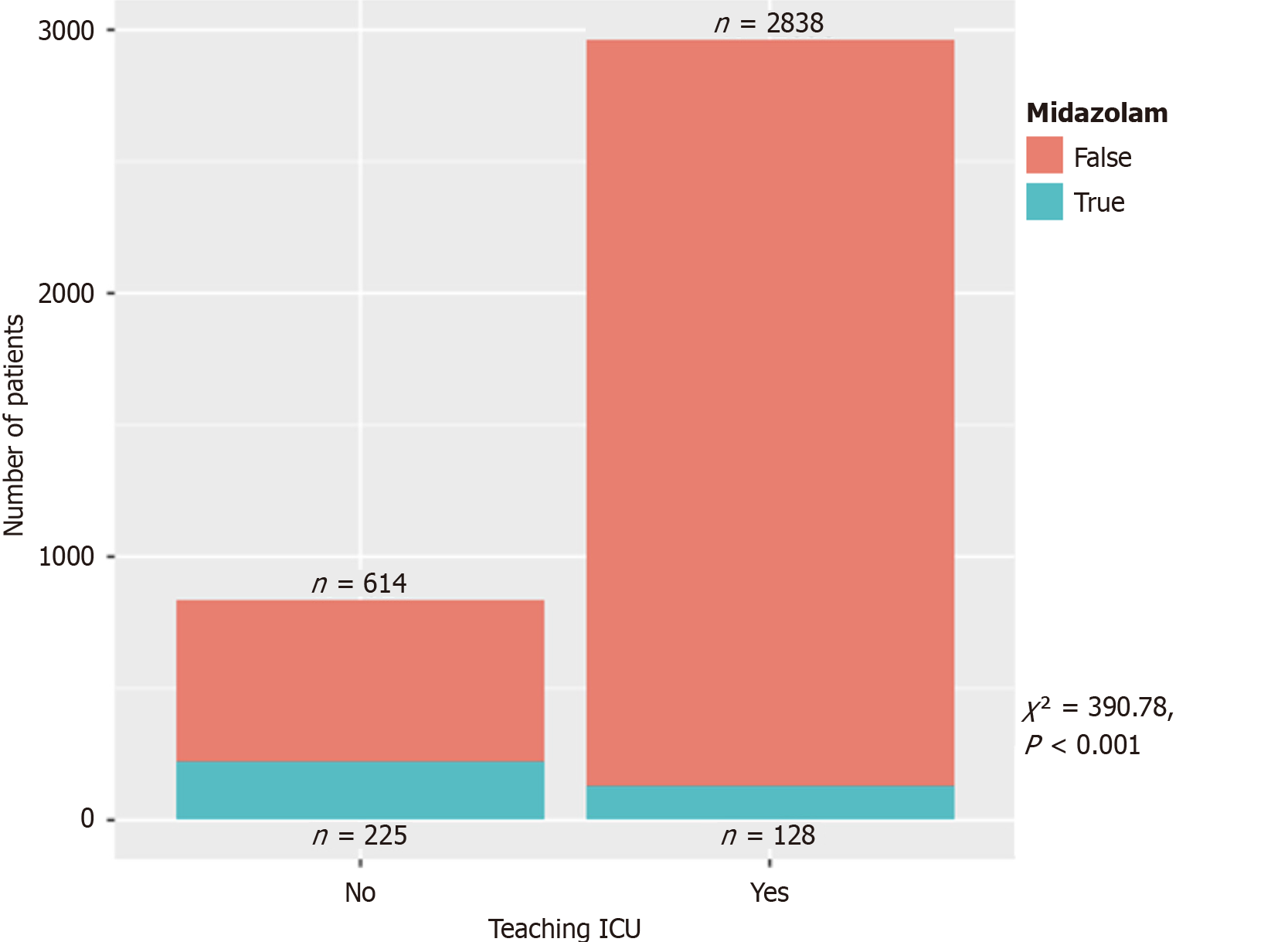

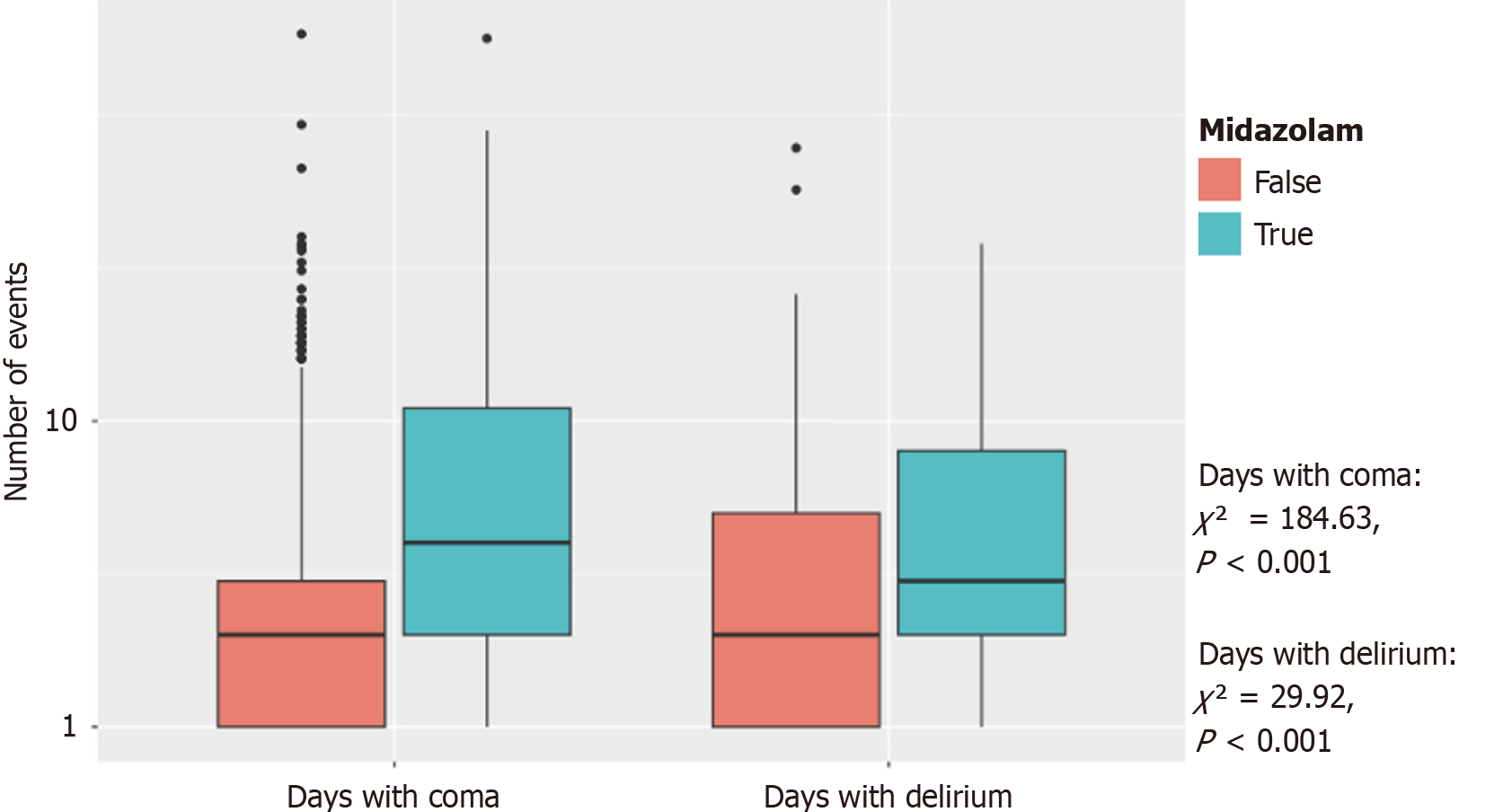

Figure 2 demonstrates the distribution of continuous infusions between critical care primary services and non-critical care primary services. Figure 3 demonstrated the final disposition of patients who received midazolam infusion (t-test = 2.14, 95% confidence intervals: 4.95-167.99, P = 0.038). Table 2 showed 117 (21%) patients discharged as deceased who received midazolam infusion (χ2 = 108.73, P < 0.001). Amongst the providers who ordered midazolam infusion, CCM ordered the infusion on 187 (5%) patients when compared to 166 (44%) patients amongst the non-CCM providers (χ2 = 598.23, P < 0.001) (Table 3). Amongst the teaching ICUs, teaching institutions ordered midazolam infusion on 128 (4%) patients vs 225 (27%) patients in non-teaching institutions (χ2 = 390.78, P < 0.001) (Table 4), which is also demonstrated in Figure 4. Figure 5 showed the distribution of patients who received midazolam infusion across our ICU locations (χ2 = 835.51, P < 0.001). 271 (77.87%) patients were identified to be in a comatose state (RSAS score ≤ 2) vs 1340 (38.76%) patients who received continuous midazolam infusion and who did not, respectively (P < 0.001). The median number of days with coma was 4 vs 2, respectively (P < 0.001). The 104 (29.89%) patients were identified to have delirium (confusion assessment method-ICU positive) vs 586 (16.95%) patients who received continuous midazolam infusion and who did not, respectively (P < 0.001). The median number of days with delirium was 3 vs 2, respectively (P = 0.0006). This is represented in Figure 6 on a logarithmic scale.

We performed a multiple logistic regression, shown in Table 5, which showed that older adults (age > 65), teaching ICU, and intensivist staffing modeled ICUs are less likely to order continuous midazolam infusions [odds ratios (OR) = 0.43, OR = 0.31, OR = 0.11, respectively, P < 0.001]. There was no difference in patients who received continuous midazolam infusion with a Charlson comorbidity index of more than 5 (OR = 0.94, P = 0.72). Patients who had a greater illness severity, indicated by SOFA score more than 7, were more likely to receive continuous midazolam infusion (OR = 1.74, P = 0.0002). Table 5 also shows that among the diagnoses that are admitted to the ICU, the ones that are more commonly associated with continuous midazolam infusion are: Acute respiratory failure, acute respiratory distress syndrome, cardiogenic shock, pneumonia (bacterial and viral) (P < 0.0001).

| Predictors | OR | 95%CI (lower limit, upper limit) | P value |

| Age > 65 years | 0.43 | 0.31, 0.59 | < 0.0001 |

| Teaching ICU | 0.31 | 0.23, 0.42 | < 0.0001 |

| CCM primary | 0.11 | 0.08, 0.16 | < 0.0001 |

| Charlson score > 5 | 0.94 | 0.69, 1.29 | 0.7151 |

| SOFA score > 7 | 1.74 | 1.30, 2.33 | 0.0002 |

| Acute respiratory failure | 2.11 | 1.51, 2.94 | < 0.0001 |

| ARDS | 6.95 | 3.82, 12.64 | < 0.0001 |

| Cardiogenic shock | 3.01 | 1.95, 4.64 | < 0.0001 |

| Septic shock | 0.80 | 0.51, 1.25 | 0.3324 |

| Sepsis | 1.22 | 0.79, 1.88 | 0.3714 |

| Hypovolemic shock | 1.05 | 0.52, 2.12 | 0.8912 |

| Unspecified shock | 1.51 | 1.00, 2.28 | 0.0504 |

| Cardiac arrest | 1.38 | 0.94, 2.02 | 0.1034 |

| Pneumonia (bacterial) | 1.56 | 1.14, 2.14 | 0.005 |

| Viral pneumonia | 7.80 | 2.11, 28.80 | 0.0021 |

| COVID PNA | 0.41 | 0.11, 1.49 | 0.1742 |

| Seizure | 1.77 | 0.92, 3.42 | 0.0895 |

| Status epilepticus | 13.17 | 6.56, 26.45 | < 0.0001 |

| Alcohol withdrawal | 2.30 | 1.41, 3.74 | 0.0008 |

Analgosedation means the use of analgesia first, in the form of an opioid, before the addition of a sedative to achieve a sedation goal[1]. Our retrospective observational study has shown that continuous midazolam infusions were more likely to be administered in open, non-intensivist staffed units. We also identified that older adults, teaching ICU, and closed ICU were consistent with less midazolam use, whereas there was no difference between the Charlson comorbidity index. Patients who had a greater illness severity (SOFA score > 7) were more likely to receive continuous midazolam infusion. We observed that mortality was higher among patients who received continuous midazolam infusion compared to those who did not (21% vs 7%) (Table 2). This finding is consistent with the literature regarding benzodiazepines. Additionally, it is known that benzodiazepines are an independent risk factor for delirium. Our study showed that there were longer coma days and delirium days in patients who received continuous midazolam infusion. Patients who were admitted with acute respiratory failure, acute respiratory distress syndrome, cardiogenic shock, and pneumonia (bacterial and viral) were more likely to receive continuous midazolam. Given the findings of our study, we can postulate that there is the possibility of a lack of familiarity with the 2018 and 2025 Society of Critical Care Medicine guidelines, along with unfamiliarity with available EMR tools in our ICUs that do not have an intensivist staffing model. Our findings highlight the importance of ongoing education and, in addition to institutional quality improvement initiatives, delivering the best possible care to mechanically ventilated patients.

The guidelines recommend targeting a lighter sedation goal by using either propofol or dexmedetomidine instead of benzodiazepines[1], and more recently, they have updated their guidelines, and a conditional recommendation was made to use dexmedetomidine over propofol for light sedation[2]. Deep sedation has been associated with decreased in-hospital and two-year survival[10]. In addition, deep sedation goals have been found to be associated with delirium, increased duration on mechanical ventilation, and longer ICU length of stay[11]. Our study was limited by the retro

Surviving an ICU stay does not equate to full recovery. A growing body of evidence has drawn attention to Post-Intensive Care Syndrome (PICS), which affects up to 80% of ICU survivors[12]. PICS encompasses a range of long-term physical, cognitive, and psychological impairments, including depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, memory loss, and deficits in executive function[12]. These complications can persist well after discharge, significantly diminishing quality of life. The burden of PICS extends beyond the patient. Families often face emotional strain, financial hardship from medical debt and lost income, and increased caregiver responsibilities. The ripple effects of an ICU admission can be profound and enduring[12].

Given the serious implications of PICS, ICU providers must proactively address modifiable risk factors[12]. Evidence-based strategies - such as minimizing sedation, promoting early mobility, and actively managing delirium - are essential. Among these, the choice of sedative is particularly impactful. Benzodiazepines, especially when used continuously, have been strongly associated with worse cognitive and psychological outcomes. By reducing their use and following current sedation guidelines, we can take meaningful steps toward reducing the incidence and severity of PICS.

Continuous midazolam infusion was more likely in patients admitted to the ICU under an open unit with a non-CCM physician with an intensivist consult available, despite guided order-sets and checklists integrated into the electronic medical record.

| 1. | Devlin JW, Skrobik Y, Gélinas C, Needham DM, Slooter AJC, Pandharipande PP, Watson PL, Weinhouse GL, Nunnally ME, Rochwerg B, Balas MC, van den Boogaard M, Bosma KJ, Brummel NE, Chanques G, Denehy L, Drouot X, Fraser GL, Harris JE, Joffe AM, Kho ME, Kress JP, Lanphere JA, McKinley S, Neufeld KJ, Pisani MA, Payen JF, Pun BT, Puntillo KA, Riker RR, Robinson BRH, Shehabi Y, Szumita PM, Winkelman C, Centofanti JE, Price C, Nikayin S, Misak CJ, Flood PD, Kiedrowski K, Alhazzani W. Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Prevention and Management of Pain, Agitation/Sedation, Delirium, Immobility, and Sleep Disruption in Adult Patients in the ICU. Crit Care Med. 2018;46:e825-e873. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1292] [Cited by in RCA: 2452] [Article Influence: 350.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lewis K, Balas MC, Stollings JL, McNett M, Girard TD, Chanques G, Kho ME, Pandharipande PP, Weinhouse GL, Brummel NE, Chlan LL, Cordoza M, Duby JJ, Gélinas C, Hall-Melnychuk EL, Krupp A, Louzon PR, Tate JA, Young B, Jennings R, Hines A, Ross C, Carayannopoulos KL, Aldrich JM. A Focused Update to the Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Prevention and Management of Pain, Anxiety, Agitation/Sedation, Delirium, Immobility, and Sleep Disruption in Adult Patients in the ICU. Crit Care Med. 2025;53:e711-e727. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 79.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 3. | Ely EW, Shintani A, Truman B, Speroff T, Gordon SM, Harrell FE Jr, Inouye SK, Bernard GR, Dittus RS. Delirium as a predictor of mortality in mechanically ventilated patients in the intensive care unit. JAMA. 2004;291:1753-1762. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1996] [Cited by in RCA: 2096] [Article Influence: 95.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Roberts PR, Rob Todd S. Comprehensive Critical Care: Adult. 3rd ed. Society of Critical Care Medicine, 2022: 710. |

| 5. | Pandharipande P, Shintani A, Peterson J, Pun BT, Wilkinson GR, Dittus RS, Bernard GR, Ely EW. Lorazepam is an independent risk factor for transitioning to delirium in intensive care unit patients. Anesthesiology. 2006;104:21-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 798] [Cited by in RCA: 803] [Article Influence: 40.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Jakob SM, Ruokonen E, Grounds RM, Sarapohja T, Garratt C, Pocock SJ, Bratty JR, Takala J; Dexmedetomidine for Long-Term Sedation Investigators. Dexmedetomidine vs midazolam or propofol for sedation during prolonged mechanical ventilation: two randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 2012;307:1151-1160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 598] [Cited by in RCA: 667] [Article Influence: 47.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Pandharipande PP, Pun BT, Herr DL, Maze M, Girard TD, Miller RR, Shintani AK, Thompson JL, Jackson JC, Deppen SA, Stiles RA, Dittus RS, Bernard GR, Ely EW. Effect of sedation with dexmedetomidine vs lorazepam on acute brain dysfunction in mechanically ventilated patients: the MENDS randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2007;298:2644-2653. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1014] [Cited by in RCA: 1004] [Article Influence: 52.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Riker RR, Shehabi Y, Bokesch PM, Ceraso D, Wisemandle W, Koura F, Whitten P, Margolis BD, Byrne DW, Ely EW, Rocha MG; SEDCOM (Safety and Efficacy of Dexmedetomidine Compared With Midazolam) Study Group. Dexmedetomidine vs midazolam for sedation of critically ill patients: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2009;301:489-499. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1139] [Cited by in RCA: 1147] [Article Influence: 67.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Reade MC, Finfer S. Sedation and delirium in the intensive care unit. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:444-454. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 364] [Cited by in RCA: 410] [Article Influence: 34.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Balzer F, Weiß B, Kumpf O, Treskatsch S, Spies C, Wernecke KD, Krannich A, Kastrup M. Early deep sedation is associated with decreased in-hospital and two-year follow-up survival. Crit Care. 2015;19:197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Girard TD, Kress JP, Fuchs BD, Thomason JW, Schweickert WD, Pun BT, Taichman DB, Dunn JG, Pohlman AS, Kinniry PA, Jackson JC, Canonico AE, Light RW, Shintani AK, Thompson JL, Gordon SM, Hall JB, Dittus RS, Bernard GR, Ely EW. Efficacy and safety of a paired sedation and ventilator weaning protocol for mechanically ventilated patients in intensive care (Awakening and Breathing Controlled trial): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;371:126-134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1339] [Cited by in RCA: 1312] [Article Influence: 72.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Schwitzer E, Jensen KS, Brinkman L, Defrancia L, Vanvleet J, Baqi E, Aysola R, Qadir N. Survival ≠ Recovery. CHEST Critical Care. 2023;1:100003. [DOI] [Full Text] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/