Published online Dec 9, 2025. doi: 10.5492/wjccm.v14.i4.111164

Revised: August 5, 2025

Accepted: August 27, 2025

Published online: December 9, 2025

Processing time: 144 Days and 20.5 Hours

Refractory septic shock is a critical and multifaceted condition that continues to pose significant challenges in critical care.

To systematically review randomized trials on emerging interventions for refractory septic shock, assessing mortality, vasopressor use, intensive care unit (ICU) length of stay, and organ dysfunction.

A systematic search was conducted in PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane CENTRAL Library, and Web of Science for studies published between 2000 and 2024. Inclusion criteria encompassed randomized controlled trials (RCT) evaluating innovative therapies for refractory septic shock. Variables of interest: The primary outcome was all-cause mortality among patients treated with novel interventions. Secondary outcomes included length of stay in the ICU, total hospital length of stay, and use of vasoactive drugs. Methodological rigor was assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool.

From 850 records, 24 RCTs met the inclusion criteria, evaluating therapies such as methylene blue, vasopressin, terlipressin, and combinations of hydrocortisone, vitamin C, and thiamine. Mortality rates ranged from 28.6% to 56.8%. Methylene blue reduced vasopressor dependency in patients requiring high norepinephrine doses by 1.0 vasopressor-free day, and terlipressin improved renal perfusion by 13.1%. Combination therapies enhanced secondary outcomes, including reductions in Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score. However, no single intervention consistently demonstrated significant survival benefits.

Adjunctive therapies for refractory septic shock may improve hemodynamics and organ function, however, they have not been shown to consistently reduce mortality. Larger trials are needed to confirm these findings. Multimodal approaches targeting inflammation are critical.

Core Tip: This systematic review of 24 randomized controlled trials evaluates novel therapies for refractory septic shock, including methylene blue, vasopressin, terlipressin, and hydrocortisone-vitamin C-thiamine combinations. While these interventions improve hemodynamics and organ function, no consistent mortality reduction was observed. Methylene blue reduced vasopressor dependency, and terlipressin enhanced renal perfusion. Larger, standardized trials are needed to validate findings and guide multimodal treatment strategies.

- Citation: Nacul FE, Bezerra MB, Gomes BC, Hohmann FB, Treml RE, Caldonazo T, da Silva AA, Passos RH, de Oliveira NE, Bedretchuk GP, Silva Jr JM. Current and emerging therapeutic options for refractory septic shock: A systematic review. World J Crit Care Med 2025; 14(4): 111164

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3141/full/v14/i4/111164.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5492/wjccm.v14.i4.111164

Refractory septic shock is a critical and multifaceted condition that continues to pose significant challenges in critical care, with mortality rates ranging from 28.6% to 56.8%[1-3], despite advancements in medical understanding and therapeutic strategies. Although definitions vary across studies and expert consensus[4,5], septic shock is broadly characterized by hypotension (systolic blood pressure ≤ 90 mmHg or mean arterial pressure (MAP) ≤ 65 mmHg) and elevated serum lactate levels (> 2 mmol/L) persisting despite adequate fluid resuscitation. Patients often require high doses of vasopressors - such as norepinephrine (NE) at rates exceeding 0.5-1.0 μg/kg/minute, or equivalent agents - to achieve hemodynamic stability[6,7].

The pathophysiology of refractory septic shock is characterized by profound vasomotor dysfunction and vascular hyporesponsiveness to catecholamines, driven by a complex interplay of mechanisms, including excessive inflammatory responses, endothelial dysfunction, activation of coagulation pathways, and dysregulation of vasodilatory mediators[2,8-12]. These interconnected processes result in severe and sustained hypotension, complicating management and rendering standard therapeutic approaches insufficient in many cases[12]. Amid persistent challenges in improving patient outcomes with current protocols, the exploration of novel therapeutic interventions remains critical.

This systematic review aims to synthesize evidence on innovative adjunctive treatments for refractory septic shock, including methylene blue, vasopressin, and combinations of hydrocortisone, vitamin C, and thiamine. By assessing their effects on mortality and secondary outcomes—such as vasopressor dependency, intensive care unit (ICU) length of stay, and organ dysfunction—this review provides a comprehensive evaluation of current data and highlights potential directions for future research.

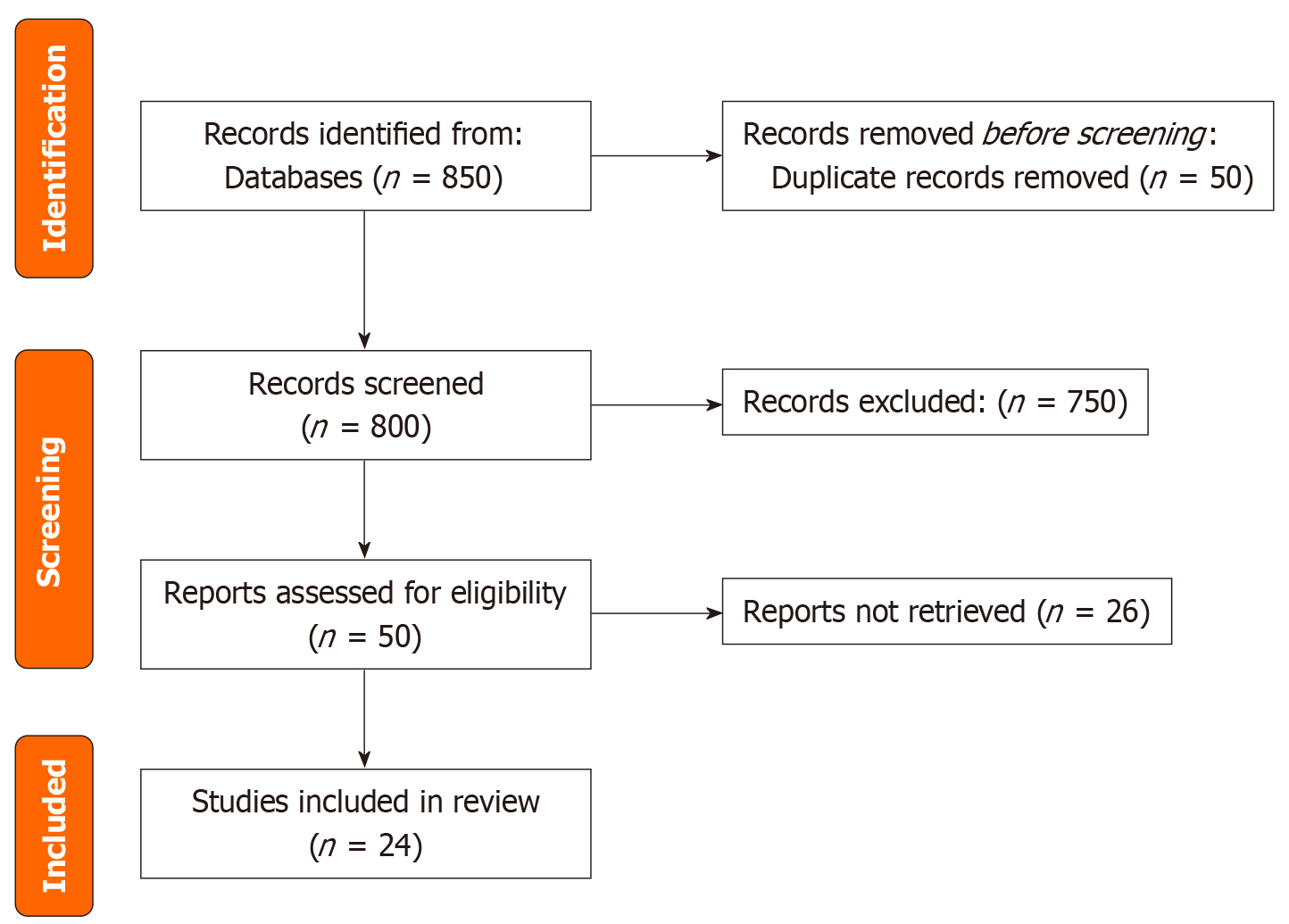

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA 2020 guidelines to ensure rigor, transparency, and reproducibility. Its primary objective was to synthesize the existing literature on the effectiveness of novel therapeutic interventions for refractory septic shock, with a specific focus on their impact on mortality and other critical clinical outcomes. Although the review protocol was not registered, it adhered to predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria to ensure methodological transparency (Figure 1).

A comprehensive search strategy was developed to identify relevant studies. The search terms included: (“septic” OR “sepsis” OR “infection”) AND (“shock” OR “Norepinephrine” OR “high dose” OR “refractory”). The strategy targeted literature published from 2000 onwards to encompass the latest advancements in septic shock management. Searches were conducted across the following databases: PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane CENTRAL Library, and Web of Science.

Each database was searched using tailored queries, and results were compiled and updated through 2024. The search strategy aimed to ensure inclusivity while maintaining a focus on clinically relevant evidence. These databases were selected for their comprehensive coverage of clinical trials, systematic reviews, and high-impact medical literature relevant to critical care and septic shock.

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they were RCTs published in peer-reviewed journals between January 2000 and December 2024, available in English with full-text accessibility. The target population comprised adult patients (≥ 18 years) with septic shock requiring vasopressor support despite adequate fluid resuscitation, defined by MAP ≤ 65 mmHg or systolic blood pressure ≤ 90 mmHg, with evidence of tissue hypoperfusion such as elevated lactate > 2 mmol/L or other markers of organ dysfunction. Eligible interventions included novel or adjunctive therapeutic approaches for refractory septic shock, encompassing methylene blue, vasopressin, terlipressin, corticosteroids, vitamin C, thiamine, or combination therapies administered in addition to standard care consisting of fluid resuscitation, antibiotics, source control, and conventional vasopressors. Studies required appropriate comparator groups receiving placebo, standard care, or alternative active interventions. They must have reported primary outcomes of all-cause mortality at any time point (28-day, 90-day, hospital, or ICU mortality) or secondary outcomes including vasopressor-free days, ICU length of stay, hospital length of stay, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score, shock reversal, or hemodynamic parameters.

Studies were excluded if they employed non-randomized designs such as observational studies, case series, case reports, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, narrative reviews, conference abstracts, editorials, letters to the editor, or lacked appropriate control groups. Population exclusions comprised pediatric patients (< 18 years), cardiogenic, hypovolemic, or obstructive shock without septic component, normotensive patients with sepsis without shock, and animal or in vitro studies. Intervention exclusions included preventive measures administered before sepsis onset, interventions focused solely on infection treatment without hemodynamic support, and studies evaluating only standard care interventions such as conventional antibiotics, fluids, or first-line vasopressors as monotherapy. Studies were also excluded if they failed to report mortality or relevant clinical outcomes, focused exclusively on laboratory parameters without clinical endpoints, had follow-up periods < 24 hours, represented duplicate publications or multiple reports of the same study population, contained insufficient data for extraction despite author contact, were retracted publications, published in languages other than English, constituted gray literature, theses, or unpublished manuscripts, or demonstrated significant methodological flaws that could not be adequately assessed using standard risk of bias tools.

While recognizing the variability in definitions across studies, we included investigations that defined refractory septic shock as persistent hypotension despite adequate fluid resuscitation (typically ≥ 30 mL/kg crystalloids), vasopressor requirements (normally NE ≥ 0.1 μg/kg/minute, though thresholds varied among studies), and ongoing evidence of tissue hypoperfusion. When multiple publications reported on the same patient cohort, we included the publication with the most comprehensive outcome data or the most extended follow-up period. We also extracted supplementary information from related publications as appropriate to ensure thorough data capture without duplication.

Following the database searches, all retrieved articles were imported into the Rayyan© platform (https://www.rayyan.ai), a software designed to facilitate systematic review workflows. Two independent reviewers (JMSJ and FBH) screened titles and abstracts while remaining blinded to each other's decisions. Full texts of potentially eligible studies were subsequently reviewed to determine final inclusion. Discrepancies were resolved through consensus meetings, ensuring that all inclusion and exclusion decisions were jointly validated. After consensus was reached on included studies, a final list of studies was compiled and independently verified for adherence to the inclusion criteria. Duplicate records across databases were identified and removed using the Rayyan© deduplication feature, followed by manual verification.

The methodological quality of included studies was evaluated using the Cochrane Risk of Bias 2 (RoB 2) tool[13-15]. This assessment covered the following domains: Randomization process: Most studies ensured proper randomization and allocation concealment. Deviations from Intended Interventions: Blinding minimized performance bias in many studies, although open-label trials raised some concerns. Missing outcome data: Studies with incomplete outcome data were flagged; however, most demonstrated low attrition bias. Measurement of outcomes: Objective outcomes, such as mortality, were reliably reported, whereas subjective outcomes raised concerns in non-blinded studies. Selection of Reported Results: Pre-registration ensured transparency; however, some studies exhibited selective outcome reporting. Overall, most studies were rated as "low risk" or "some concerns", supporting the robustness of the synthesized evidence (Table 1)[15-29]. The heterogeneity among studies was assessed using qualitative synthesis and, where appropriate, quantitative metrics such as the I2 statistic.

| Ref. | Randomization process | Deviations from intended interventions | Missing outcome data | Measurement of outcomes | Selection of the reported results | Overall risk of bias |

| Lyu et al[15], 2022 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Ibarra-Estrada et al[16], 2023 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Hajjar et al[17], 2019 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Moskowitz et al[18], 2020 | Low risk | Some concerns | Low risk | Low risk | Some concerns | Some concerns |

| Fujii et al[19], 2020 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Some concerns | Some concerns | Some concerns |

| Sevransky et al[20], 2021 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Wang et al[21], 2022 | Some concerns | Some concerns | Some concerns | Some concerns | Some concerns | Some concerns |

| Cherukuri et al[22], 2019 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Douglas et al[23], 2020 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Morelli et al[24], 2008 | Some concerns | Some concerns | Some concerns | Some concerns | Some concerns | Some concerns |

| Albanèse et al[25], 2005 | Low risk | High Risk | Some concerns | High Risk | High Risk | High Risk |

| Hyvernat et al[26], 2016 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Annane et al[27], 2002 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Liu et al[28], 2018 | Some concerns | Low risk | Some concerns | Some concerns | Some concerns | Some concerns |

| Xiao et al[29], 2016 | Some concerns | Some concerns | Some concerns | Some concerns | Some concerns | Some concerns |

Data extraction was performed independently by two reviewers to enhance accuracy and reliability. A third researcher resolved any discrepancies through discussion. Key data extracted included study characteristics (design, population, and interventions) as well as primary and secondary outcomes (mortality, ICU length of stay, total hospital stay, and vasopressor-free-days). All data were recorded using a standardized form containing fields for study details, interventions, outcomes, and risk of bias ratings.

The primary outcome was all-cause mortality among septic shock patients treated with novel therapies. Secondary outcomes included length of stay in the ICU, total hospital stays, and vasoactive drug use.

These outcomes were selected to provide a comprehensive assessment of the clinical efficacy of the interventions and their impact on patient management. For studies with incomplete outcome data, sensitivity analyses were planned to assess the impact of missing data on the overall conclusions.

A comprehensive search across multiple databases initially identified 850 records. After removing 50 duplicates, 750 articles were screened based on titles and abstracts. Of these, 50 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility, with 26 excluded for not meeting the predefined inclusion criteria. Ultimately, 24 studies were included in the final analysis. The study selection process is illustrated in the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1).

The 24 studies included in this meta-analysis comprised a combination of large multicenter RCTs and smaller-scale investigations (Table 2).

| Ref. | Type of study | Type of patients | Primary outcomes | Number of patients | Mean age | Mortality |

| Lyu et al[15], 2022 | RCT, single-center, double-blind | Adult patients with septic shock | Mortality at 90 days | Intervention Group: 213 patients received a combination of hydrocortisone, vitamin C, and thiamine. Control Group: 213 patients received 0.9% saline | 64 | 90-day Mortality: 40.4% in the intervention group vs 39.0% in the placebo group. 28-day Mortality: 37.1% in the intervention group vs 36.2% in the placebo group |

| Ibarra-Estrada et al[16], 2023 | RCT, double-blind | Adults Diagnosed with septic shock due to suspected or confirmed infection, requiring NE to maintain a MAP ≥ 65 mmHg and serum lactate > 2 mmol/L after adequate fluid resuscitation | 28-day mortality | Methylene blue group: 45 patients received methylene blue as an adjunctive therapy. Placebo group: 46 | 46-47 | 28-mortality: MB 33% and P 46% |

| Hajjar et al[17], 2019 | RCT, double-blind | Adults (≥ 18 years) with cancer admitted to the ICU, showing documented or strong clinical suspicion of infection and meeting at least two criteria of the systemic inflammatory response syndrome | 28-day all-cause mortality | Vasopressin group: 125 patients NE group: 125 patients | NR | 28-day mortality: Vasopressin group: 56.8%. NE group: 52.8%. 90-day mortality: Vasopressin group: 72.0%. NE group: 75.2% |

| Moskowitz et al[18], 2020 | RCT, multicenter, double-blind | Adult patients with septic shock with infusion vasopressors | Change in SOFA score | Intervention: 100 patients received a combination of vitamin C, hydrocortisone, and thiamine. Control: 100 patients received a placebo | 68 | 30-day mortality: Intervention group: 34.7%, placebo group: 29.3% |

| Fujii et al[19], 2020 | RCT, multicenter, open label | Adults with documented infection, increase of at least 2 points in the SOFA score. Lactate levels greater than 2 mmol/L. Vasopressor dependency for at least 2 hours prior to enrollment | Time alive and free from vasopressors | Intervention Group: 109 patients received intravenous vitamin C, hydrocortisone, and thiamine. Control group: 107 patients received intravenous hydrocortisone alone | 61.7 | Intervention group: 28.6% mortality. Control group: 24.5% mortality |

| Sevransky et al[20], 2021 | RCT, double-blind, adaptive | Adults with sepsis requiring mechanical ventilation or high-flow oxygen support due to respiratory failure. Continuous vasopressor support to maintain adequate blood pressure | days free of vasopressors and mechanical ventilation in the first 30 days | Treatment group: 1000 patients received combination therapy with vitamin C, thiamine, and corticosteroids. Control group: 1000 patients received matching placebos for each active agent | 65 | Interrupted before ending |

| Wang et al[21], 2022 | Pilot RCT | Adults (≥ 18 years) with septic shock. NE dose ≥ 15 µg/minute | Renal perfusion: Assessed through changes in urine output and renal function parameters | 22 patients: TP group: 10 patients. Usual care group: 12 patients | 62.5 | 27.3% for the TP group and 41.7% for the usual care group |

| Cherukuri et al[22], 2019 | RCT, double-blind | Adult patients with sepsis or septic shock | Length of ICU stay: Days on ventilator: Days on intravenous blood pressure support: 28-day mortality rate | Intervention: 32 patients received 100000 IU of vitamin A intramuscularly daily for 7 days. Control: 32 patients received a blinded placebo | 51 | 28-Day Mortality Rates. Vitamin A group: 34%. Placebo group: 28% |

| Douglas et al[23], 2020 | RCT, multicenter | Adults who presented with signs of sepsis and hypotension (MAP ≤ 65 mmHg) after receiving between 1 L and 3 L of fluids | Positive fluid balance at 72 hours or at ICU discharge, whichever occurred first | 83 patients in the intervention group and 41 patients in the usual care group | 62 | Intervention group: 20.5%. Control group: 24.4% |

| Morelli et al[24], 2008 | RCT | Adult patients with septic shock | The mortality rate is 28 days after treatment initiation. The outcome aimed to assess the effectiveness of combined dobutamine and TP treatment in improving survival rates in patients with septic shock | 60 | 65 | TG (dobutamine and TP): What is the primary and secondary outcome. 40% mortality. CG (standard treatment): 60% mortality |

| Albanèse et al[25], 2005 | RCT, open-label study | Diagnosed with hyperdynamic septic shock after fluid resuscitation-Exhibited hemodynamic instability (MAP ≤ 60 mmHg). Had two or more organ dysfunctions | MAP achieved in patients with hyperdynamic septic shock after treatment with either NE or TP | 20 patients, NE group: 10 patients, TP group: 10 patients | 65 | 30% among the patients with hyperdynamic septic shock |

| Hyvernat et al[26], 2016 | RCT, double-blind study | Persistent hypoperfusion despite adequate fluid resuscitation and NE administration. Defined as severe sepsis with arterial hypotension (SBP < 90 mmHg or MAP < 70 mmHg) despite adequate fluid resuscitation | Mortality in 28-day | 59 in the 200 mg group and 63 in the 300 mg group | 64.8 | 200 mg group: 52.5%. 300 mg group: 44.4% |

| Annane et al[27], 2002 | RCT double-blind, parallel group | Adults (> 18 years). Required NE to maintain MAP. Urinary output less than 0.5 mL/kg/hour for at least 1 hour. Arterial lactate levels higher than 2 mmol/L | 28-day survival | Corticosteroid group: Number of Patients: 151. Treatment: Received hydrocortisone (50 mg IV every 6 hours) and fludrocortisone (50 µg orally once daily) for 7 days. Placebo group: Number of patients: 149. Treatment: Received matching placebos for 7 days | 63 | Corticosteroid group: 43.0% (65 out of 151 patients). Placebo group: 49.7% (74 out of 149 patients) |

| Morelli et al[35], 2009 | Pilot RCT | Patients diagnosed with septic shock. MAP below 65 mmHg despite adequate volume resuscitation | The primary outcome was the total NE dose required to maintain a MAP of 65-75 mmHg over the 48-hour treatment period | TP group: 15 patients. Vasopressin group: 15 patients. NE gsroup: 15 patients | 65 | Zero during 48 hours |

| Lv et al[36], 2017 | RCT, double-blind | Adults (≥ 18 years). Onset of septic shock within 6 hours | 28-day all-cause mortality | Hydrocortisone group: 58 patients. Placebo group: 60 patients | Hydrocortisone group: 65.4 years. Placebo group: 66.1 years | 28-day mortality: Hydrocortisone group: 23.1%. Placebo group: 32.2%. In-Hospital mortality: Hydrocortisone group: 31.0%. Placebo group: 40.0% |

| Russell et al[32], 2008 | RCT, multicenter, double-blind | Adults diagnosed with septic shock requiring vasopressor support, NE | 28-day all-cause mortality | Vasopressin group: 396 patients. NE group: 382 patients | 64 | 28-day mortality: Vasopressin group: 35.4%. NE group: 39.3%. 90-day mortality: Vasopressin group: 43.9%. NE group: 49.6% |

| Russell et al[31], 2009 | Post hoc, multicenter, blinded RCT substudy | (≥ 16 years). Diagnosed with septic shock, ongoing hypotension requiring at least 5 µg/minute of NE infusion for a minimum of 6 hours | 28-day mortality | Corticosteroid treatment group: Vasopressin + corticosteroids: 296 patients. NE + corticosteroids: 293 patients. Corticosteroid treatment group: Vasopressin: 93 patients. NE: 97 patients | 60 | 28-day mortality overall: Corticosteroids + vasopressin: 35.9% corticosteroids + NE: 44.7%. No corticosteroids + vasopressin: 66.7%. No corticosteroids + NE: 62.9% |

| Yildiz et al[37], 2011 | RCT, double-blind | Adults (≥ 18 years). Confirmed sepsis, characterized by infection and systemic inflammatory response syndrome. Patients were often classified based on severity scores, such as APACHE II or SOFA, indicating varying degrees of organ dysfunction | 28-day mortality | Steroid group: 100 patients. Placebo group: 100 patients | 60 | Steroid group: 16 (59.3) and placebo group: 15 (53.6) |

| Keh et al[30], 2003 | RCT, double-blind crossover | Proven or strongly suspected infection. Presence of three or more of the following conditions: Mechanical ventilation. Heart rate > 90 beats per minute. Temperature > 38 °C or < 36 °C. White blood cell count > 12000 cells/µL or < 4000 cells/µL, or > 10% immature cells. Sepsis-induced hypotension: SBP < 90 mmHg or a reduction of > 40 mmHg from baseline | Change in MAP and systemic vascular resistance after treatment with low-dose hydrocortisone compared to placebo | Hydrocortisone group: 20. Placebo group: 20 | Hydrocortisone group: 54. Placebo group: 50 | Hydrocortisone group: 30%. Placebo group: 30% |

| Keh et al[38], 2016 | RCT, double-blind | Adults (≥ 18 years). Evidence of infection Systemic response to infection (at least 2 systemic inflammatory response syndrome criteria). Organ dysfunction present for no longer than 48 hours. Not in septic shock at the time of randomization | Development of septic Shock: Within 14 days of treatment | Hydrocortisone group: 190. Placebo group: 190 | 65 | 28-day mortality: Hydrocortisone group: 21.1%. Placebo group: 23.7%. 90-day mortality: Hydrocortisone group: 28.4%. Placebo group: 30.5%. 180-day mortality: Hydrocortisone group: 34.2%. Placebo group: 36.8% |

| Annane et al[34], 2018 | RCT, multicenter, double-blind | Adults (≥ 18 years). Diagnosed with septic shock requiring vasopressor therapy | 90-day all-cause mortality | Hydrocortisone plus fludrocortisone: 614. Placebo: 626 | 63 | 28-day mortality: Hydrocortisone plus Fludrocortisone: 20%. Placebo: 25%. 90-day all-cause mortality: Hydrocortisone plus fludrocortisone group: 30%. Placebo group: 36% |

| Venkatesh et al[33], 2019 | RCT, multicenter, double-blind | Adults undergoing mechanical ventilation. Documented or strongly suspected infection. Treated with vasopressors or inotropic agents at least 4 hours prior to randomization | 90-day all-cause mortality | Hydrocortisone: 1988. Placebo: 1902 | 63 | 28-day mortality: Hydrocortisone group: 197. Placebo group: 199. 90-day all-cause mortality: Hydrocortisone group: 511; placebo group: 526 |

| Liu et al[28], 2018 | RCT, multicenter, double-blind | Adults with hypotension despite adequate fluid resuscitation, and at least two diagnostic criteria for systemic inflammatory response syndrome | 28-day mortality | TP group: 312 patients. NE group: 305 patients | 61 | 28-day mortality: TP group: 40%; NE group: 38% |

| Xiao et al[29], 2016 | RCT | Adults with SBP < 90 mmHg and MAP < 65 mmHg are required to use vasoactive agents | 7-day mortality | NE group: 17, NE + TP group: 15 | 63.2 | 7-day mortality: NE group 76.5% and NE + TP 33.3% |

All studies assessed the efficacy of therapeutic interventions in patients diagnosed with refractory septic shock. Most focused on adjunctive therapies used alongside standard vasopressor treatments, particularly NE.

The interventions evaluated in the studies were varied and included corticosteroids, vitamin C, thiamine, methylene blue, vasopressin, and terlipressin. Patient populations were diverse in terms of age, severity of septic shock, and comorbid conditions. Study designs ranged from single-center to multicenter trials, contributing to the observed variability in outcomes.

Mortality was the primary outcome in most of the studies included, with rates ranging from 28.6% to 56.8%. This wide variation was influenced by factors such as the specific intervention used, patient characteristics, and study design.

For instance, the combination of hydrocortisone, vitamin C, and thiamine did not result in a significant reduction in 90-day mortality between the treatment and placebo groups. In contrast, methylene blue showed a potential reduction in 28-day mortality, with 33% in the treatment group compared to 46% in the placebo group, although the small sample size in this study suggests that these results should be interpreted with caution[16].

Secondary outcomes assessed across the studies included shock reversal, vasopressor-free days, ICU length of stay, and organ function as measured by the SOFA score.

In terms of shock reversal, the combination of hydrocortisone, vitamin C, and thiamine was associated with faster hemodynamic recovery compared to the placebo group. Additionally, another study found that patients in the intervention group experienced a greater number of vasopressor-free days, indicating that adjunctive therapies may help reduce reliance on vasopressors in critically ill patients.

Regarding the use of vasopressors, the addition of vasopressin significantly reduced the dependence on NE. Another study found improved renal perfusion in patients receiving terlipressin, although this did not lead to a reduction in overall mortality.

Several studies also measured the impact of interventions on organ function, as indicated by changes in SOFA scores. One study reported significant reductions in SOFA scores in patients treated with vitamin C, hydrocortisone, and thiamine, suggesting that these therapies may offer broader benefits for organ function, beyond simply improving hemodynamic status (Table 3).

| Ref. | Secondary outcomes | Adverse events |

| Lyu et al[15], 2022 | 28day mortality; ICU mortality; Hospital mortality; reversal of shock; time to shock reversal; 12 hours delta SOFA score; ICU free days; vasopressor free days; ventilator support free days; length of stay in ICU; length of stay in hospital | Hyperglycemia; hypernatremia; fluid overload |

| Ibarra-Estrada et al[16], 2023 | Hemodynamic parameters; organ dysfunction; length of stay; adverse events | Hypotension; serotonin syndrome; there was a risk of serotonin syndrome, particularly in patients taking selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Allergic Reactions to methylene blue. Other minor events; nausea, vomiting, and local infusion site reactions |

| Hajjar et al[17], 2019 | 90 days all cause mortality; days free from advanced support; adverse effects | Arrhythmia |

| Moskowitz et al[18], 2020 | Kidney failure; 30 day mortality; ventilator free days; shock free; ICU free days | Hyperglycemia; hypernatremia; new hospital acquired infections |

| Fujii et al[19], 2020 | 90 days mortality; duration of ICU stay; duration of hospital stay; The total length of time patients remained hospitalized. Organ dysfunction scores; adverse events | Intervention, 10 (10.2%) vs usual care, 7 (15.6%). Not related |

| Sevransky et al[20], 2021 | Mortality at 30 days, ICU mortality, mortality at 180 days, length of ICU stay, length of hospital stay, and longterm emotional and cognitive outcomes at 180 days | |

| Wang et al[21], 2022 | Mortality rate at 28 days. Hemodynamic parameters; Including MAP and NE requirements. Adverse events related to TP use. Changes in serum creatinine levels and other renal function indicators | Cardiovascular events; increased heart rate or arrhythmias. Renal events; worsening renal function or acute kidney injury. Gastrointestinal events; ischemic colitis or other gastrointestinal complications. New infections or worsening of existing infections. Injection Site Reactions; Localized reactions at the site of TP administration |

| Cherukuri et al[22], 2019 | Serum vitamin A levels; cortisol response; incidence of adverse effects | Nausea; injection site reactions |

| Douglas et al[23], 2020 | RRT; mechanical ventilation; discharge rates; mortality rates | Arrhythmias; NE extravasation |

| Morelli et al[24], 2008 | NE requirements; systemic and regional hemodynamic; organ function; SvO2 | TP; cardiac ischemia; decreased cardiac output; gastrointestinal ischemia; skin reactions as pallor due to vasoconstriction. Dobutamine; tachyarrhythmias; increased myocardial oxygen demand; hypotension |

| Albanèse et al[25], 2005 | Cardiac index; oxygen delivery index; oxygen consumption index; renal function; blood lactate levels | NE; tissue ischemia due to excessive vasoconstriction; arrhythmias or increased heart rate; increased oxygen demand of tissues; decreased mesenteric blood flow; TP; decreased cardiac index and potential for reduced oxygen delivery; bradycardia; fluid overload is used with caution in patients with renal impairment |

| Hyvernat et al[26], 2016 | Vasopressor requirements, infectious and digestive complications, hemodynamic responses, days free from mechanical ventilation, vasopressors, and renal replacement therapy, adverse events | Haemorrhagic events; superinfections |

| Annane et al[27], 2002 | Mortality rates; overall mortality rates at various time points (e.g., 7 days, 14 days). Time to vasopressor withdrawal; adverse events; clinical improvement | Infections; increased incidence of new infections in both groups. Gastrointestinal issues; stress ulcers or gastrointestinal bleeding. Hyperglycemia; observed in the corticosteroid group. Electrolyte Imbalances; Including hyponatremia and hyperkalemia. Neurological Events; Such as delirium or altered mental status |

| Morelli et al[35], 2009 | Hemodynamic parameters; organ function; adverse events; mortality | Tachyarrhythmias; 1 in the vasopressin group. 4 in the NE group. Changes in bilirubin levels; higher total and direct bilirubin concentrations in the vasopressin and NE groups; platelet count; a decrease in platelet count was observed only in the TP group over time. Renal function; RRT was noted in the NE group |

| Lv et al[36], 2017 | In hospital mortality; reversal of shock; duration of ICU stay; duration of hospital stay | Hyperglycemia; hydrocortisone group; 90.9%; placebo group; 81.5% |

| Russell et al[32], 2008 | 90 days mortality; organ dysfunction; adverse events; vasopressor requirements | Cardiac events (e.g., arrhythmias); Ischemic events (e.g., limb ischemia); other complications related to the use of vasopressors |

| Russell et al[31], 2009 | Duration of vasopressor support; sock reversal; organ dysfunction; length of ICU stay; adverse events | Arrhythmias; limb ischemia; gastrointestinal ischemia |

| Venkatesh et al[33], 2018 | 28 days all cause mortality; Evaluated to assess shorter term effects. Duration of vasopressor use; measured to determine the impact on hemodynamic support. Duration of mechanical ventilation; assessed to evaluate respiratory support needs. Organ dysfunction; quality of life | Hyperglycemia; gastrointestinal bleeding; secondary infections |

| Yildiz et al[37], 2011 | Adverse events; hormonal levels; incidence of adrenal insufficiency (AI) and Relative Adrenal Insufficiency (RAI); Assessment of adrenal function in patients; APACHE II and SOFA scores; clinical characteristics | No serious adverse events were reported in either the steroid or placebo groups |

| Keh et al[30], 2003 | Inflammatory markers; NE requirements; immune function; mortality rates | Infections; increased incidence of secondary infections in both groups, but no significant difference between hydrocortisone and placebo. Gastrointestinal bleeding, though it was not significantly higher in the hydrocortisone group. Hyperglycemia; the hydrocortisone group required insulin management for some patients |

| Keh et al[38], 2016 | Time until septic shock; mortality 28 days, 90 days, 180 days; secondary infections; weaning failure; muscle weakness; hyperglycemia | Hyperglycemia; secondary infections; muscle weakness; weaning failure |

| Annane et al[34], 2018 | Mortality rates; days alive and free of vasopressors; organ failure; mechanical ventilation | Gastrointestinal bleeding; superinfection; hyperglycemia; neurologic sequelae |

| Liu et al[28], 2018 | change in sofa score; days alive and free of vasopressors; incidence of serious adverse events | Digital ischemia; severe diarrhea; arrhythmias; intestinal ischemia |

| Xiao et al[29], 2016 | hemodynamic parameters; complications; success rate for 6 hours resuscitation goals | Cardiac arrhythmias; skin necrosis at infusion sites; other organ dysfunctions |

Adverse events associated with the therapeutic interventions varied across studies. Commonly reported adverse effects included hyperglycemia with corticosteroid use, which was noted in several studies, highlighting the need for careful blood glucose monitoring in patients receiving corticosteroids.

Cardiac arrhythmias were identified as a significant adverse event associated with vasopressin and terlipressin use. These arrhythmias were particularly concerning in critically ill patients, who may already be at high risk of cardio

Injection site reactions and other minor adverse events were more commonly observed with methylene blue. While these events were generally transient and not considered severe, they nonetheless warrant attention, especially in critically ill patients receiving multiple interventions.

Subgroup analyses provided valuable insights into the effectiveness of the interventions in specific patient populations. Methylene blue appeared to be particularly effective in patients requiring higher doses of NE (greater than 0.5 μg/kg/minute), suggesting that it may be especially beneficial for patients with more severe shock (Table 4).

| Ref. | NE dosage | TP dosage | Vasopressin dosage | Dobutamine dosage |

| Lyu et al[15], 2022 | Not specified | |||

| Ibarra-Estrada et al[16], 2023 | Not specified | 0.03 IU/minute if NE dose reached ≥ 0.25 μg/kg/minute | ||

| Hajjar et al[17], 2019 | Infusion was started at 5 mL/hours and increased by 2.5 mL/hours every 10 minutes to reach a maximum target rate of 30 mL/hours | Ranged from 0.01 to 0.06, IU/minute | ||

| Moskowitz et al[18], 2020 | Not specified | |||

| Fujii et al[19], 2020 | Initial dose: 0.05 to 0.5 μg/kg/minute, Titration: Dose adjusted based on the patient's blood pressure response, aiming to maintain a MAP ≥ 65 mmHg | |||

| Sevransky et al[20], 2021 | Initial dose: Start at 0.05 to 0.1 μg/kg/minute. Titration: Adjust as necessary to achieve a MAP ≥ 65 mmHg | |||

| Wang et al[21], 2022 | NE greater than or equal to 15 μg/minute (Norepinephrine ≥ 15 μg/minute) | |||

| Cherukuri et al[22], 2019 | Not specified | |||

| Douglas et al[23], 2020 | Initial dose: 0.05 to 0.1 μg/kg/minute; Titration: Dose increased based on the patient's response, often up to 0.5 μg/kg/minute or higher if necessary to achieve and maintain a MAP of ≥ 65 mmHg | |||

| Morelli et al[24], 2008 | Continuous infusion: 0.9 mg/kg/minute to maintain MAP (MAP) at 70 mmHg | Single dose: 1 mg administered as a bolus infusion | Initial dose: 3 mg/kg/minute. Titration: The dose was progressively increased in increments of 1 to 3 mg/kg/minute to reverse the anticipated decrease in mixed SvO2 caused by the infusion of TP | |

| Albanèse et al[25], 2005 | Initial Dose: 0.3 μg/kg/minute. Titration: Increased by increments of 0.3 μg/kg/minute at 4-minute intervals to achieve a target MAP of 65 to 75 mmHg | Initial bolus: 1 mg (equivalent to 0.03-0.04 UI/minute). Second bolus: An additional 1 mg was given if the MAP remained below 65 mmHg after 20 minutes | ||

| Hyvernat et al[26], 2016 | Initial dosage: The starting dose typically ranged from 0.05 to 0.5 μg/kg/minute and was titrated based on the patient's response. Titration: Doses were adjusted as needed to achieve the target MAP | |||

| Annane et al[27], 2002 | Systolic arterial pressure lower than 90 mmHg for at least 1 hours despite adequate fluid replacement and administration of more than 5 μg/kg of dopamine, or current treatment with epinephrine or NE | |||

| Morelli et al[35], 2009 | NE 15 μg/minute | Terlipressin 1.3 μg/kg/hour | Vasopressina 0.03 U/minute | |

| Lv et al[36], 2017 | Not specified | |||

| Russell et al[32], 2008 | 5 μg of NE per minute | |||

| Russell et al[31], 2009 | 5 μg of NE per minute | |||

| Venkatesh et al[33], 2019 | Not specified | |||

| Yildiz et al[37], 2011 | Not specified | |||

| Keh et al[30], 2003 | Not specified | |||

| Keh et al[38], 2016 | Not specified | |||

| Annane et al[34], 2018 | 0.5 to 1.0 µg/kg/minute to maintain MAP | |||

| Liu et al[28], 2018 | starting dose of 4 µg/min, which could be titrated up to a maximum of 30 µg/minute | 20 µg/hour, with the option to titrate up to a maximum of 160 µg/hour | ||

| Xiao et al[29], 2016 | From 0.5 to 2.22 µg/kg/minute to maintain MAP | 1.3 mg/kg/hour |

Similarly, the combination of vitamin C, hydrocortisone, and thiamine led to significant improvements in SOFA scores, particularly in patients with more severe organ dysfunction. This suggests adjunctive therapies may provide greater benefits to patients experiencing multiple organ failure.

Sensitivity analyses confirmed the robustness of these findings, although limitations such as small sample sizes and variability in study designs were acknowledged. These factors may have introduced some degree of bias, which should be considered when interpreting the results.

The substantial heterogeneity observed across studies precluded the performance of quantitative meta-analysis. The I2 statistic for mortality outcomes exceeded 75%, indicating considerable statistical heterogeneity. Additionally, the diversity in interventions, patient populations, and outcome definitions made pooling of results clinically inappropriate. Therefore, we present a qualitative synthesis of the evidence with detailed tabular summaries.

This systematic review synthesizes findings from 24 randomized clinical trials investigating adjunctive therapies for refractory septic shock, encompassing interventions such as vasopressin, terlipressin, methylene blue, and combinations of hydrocortisone, vitamin C, and thiamine. The results highlight the persistent challenge of improving survival rates, with mortality ranging from 28.6% to 56.8%[15-19,21-33]. While some interventions demonstrated benefits in hemodynamic stabilization and increased vasopressor-free days, their impact on overall survival remains inconclusive[15-19,21].

The definition of refractory septic shock varied among studies, typically involving sustained hypotension (MAP ≤ 65 mmHg) despite adequate fluid resuscitation and high-dose vasopressors[15-17,21,25,27,34]. However, the lack of standardized inclusion criteria and endpoints—such as varying definitions of mortality (28-day vs 90-day) —changes in the SOFA score, and ICU length of stay, highlights significant heterogeneity among the studies[15-19,21,27,34]. This variability complicates direct comparisons and emphasizes the need for a consensus on the definition and measurement of refractory septic shock and its outcomes.

In terms of hemodynamic targets, maintaining a MAP ≥ 65 mmHg was consistently used as the goal across the studies[15-18,21,25,27,34], in line with current clinical guidelines[1]. However, evidence suggests that personalized hemo

The therapies evaluated in this review demonstrated varying degrees of efficacy. Methylene blue, through its inhibition of nitric oxide synthesis, exhibited potential for reducing mortality[16], though further validation in larger trials is needed. Vasopressin was found to reduce NE requirements, but its impact on mortality remained inconsistent across studies[17,21,31,32]. Similarly, combinations of hydrocortisone, vitamin C, and thiamine improved secondary outcomes, such as vasopressor-free days and organ dysfunction, without consistently reducing mortality[15,18,19]. These findings suggest that while these therapies provide hemodynamic and metabolic support, their effects may not be sufficient to address the complex pathophysiology of refractory septic shock.

Mortality remained the most commonly reported primary endpoint across studies[15-19,21-33], underscoring its importance as the benchmark for assessing therapeutic efficacy. Secondary outcomes, such as SOFA score changes, vasopressor-free days, and ICU length of stay, highlighted the capacity of certain therapies to stabilize hemodynamics and improve organ function[15-19,21]. For instance, methylene blue demonstrated significant potential in reducing vasopressor dependency[16,21], and terlipressin improved renal perfusion and urine output[21,25]. However, the long-term impact of these therapies remains unclear.

Adverse events were variably reported and included hyperglycemia, particularly with corticosteroids, as observed in Lyu et al[15] and Venkatesh et al[33]. Cardiac arrhythmias were noted with vasopressin and terlipressin, while methylene blue was associated with injection site reactions[16]. These adverse events highlight the importance of carefully balancing the therapeutic benefits of these interventions with their potential risks, particularly in critically ill patients who may already be vulnerable to complications.

Variability in dosing regimens further complicates direct comparisons among studies. For example, vasopressin dosages ranged from 0.01 to 0.06 IU/minute[17,31,32], while NE was titrated to maintain MAP ≥ 65 mmHg, often exceeding 0.5 μg/kg/minute in severe cases[15,16,19,21]. These discrepancies highlight the need for standardizing dosing protocols to optimize clinical outcomes and minimize adverse events.

The studies included in this review exhibited several methodological limitations, although some of these limitations can be mitigated through careful interpretation and ongoing research. Small sample sizes were a common limitation, reducing the statistical power to detect significant differences in both mortality and secondary outcomes. Despite these small sample sizes, the consistency of trends across multiple studies strengthens the reliability of the findings, and these smaller trials often provide valuable preliminary data that warrant further investigation in larger, multicenter trials.

The heterogeneity of study designs, inclusion criteria, and interventions introduced variability that complicated direct comparisons. However, this heterogeneity reflects the diversity of clinical scenarios encountered in real-world settings and enhances the external validity of the findings. Additionally, subgroup analyses performed in some studies—such as those focusing on patients with higher NE requirements or specific patient populations—provided valuable insights into how tailored therapeutic approaches may improve outcomes.

Many studies were limited by short follow-up periods, typically 28 or 90 days, restricting the ability to evaluate long-term survival and quality of life. While short-term follow-ups are important for understanding immediate survival and stabilization—often primary goals in the acute phase of septic shock—future studies could build on these findings by incorporating extended follow-up periods to assess longer-term outcomes.

Inconsistent definitions of refractory septic shock and varying thresholds for vasopressor refractoriness further challenged the generalizability of the findings. Efforts to standardize these definitions are ongoing, and the use of core inclusion criteria, such as MAP thresholds and vasopressor requirements, provides reasonable consistency for interpreting results across studies.

Finally, adverse event reporting was inconsistent, limiting the comprehensive assessment of the safety profiles of the interventions. Nonetheless, key adverse events — such as hyperglycemia and cardiac arrhythmias — were consistently documented in high-quality trials. The adoption of standardized reporting guidelines, such as those recommended by CONSORT, could improve the uniformity of safety data in future studies.

Future research should prioritize multimodal treatment strategies that integrate immune modulation, hemodynamic optimization, and organ protection. Larger, multicenter trials using harmonized definitions and standardized methodologies are essential to validate the findings of this review. Investigating cytokine-blocking therapies targeting interleukin (IL)-1, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor alpha, as well as precision tools such as the Hypotension Prediction Index, could offer new insights into targeted interventions[1].

Additionally, long-term outcomes, including survival beyond 180 days and quality of life, should be incorporated into future studies to provide a more comprehensive evaluation of therapeutic efficacy. Standardizing dosing protocols and exploring combination therapies tailored to patient-specific conditions could further refine treatment approaches for refractory septic shock.

Refractory septic shock remains a critical clinical challenge, with high mortality rates despite the use of adjunctive therapies such as methylene blue, vasopressin, and combinations of hydrocortisone, vitamin C, and thiamine. While these interventions show potential in improving hemodynamic stability and secondary outcomes, their impact on survival remains uncertain. The variability in study designs and outcome definitions underscores the need for standardization in future trials. Larger, well-designed studies are required to confirm the long-term efficacy and safety of these therapies and to explore personalized treatment strategies for better patient outcomes. These efforts are essential to guide more effective clinical management strategies and improve outcomes for this high-risk patient population.

The authors would like to thank those who provided essential support throughout this systematic review process.

| 1. | Angriman F, Momenzade N, Adhikari NKJ, Mouncey PR, Asfar P, Yarnell CJ, Ong SWX, Pinto R, Doidge JC, Shankar-Hari M, Harhay MO, Masse MH, Harrison DA, Rowan KM, Li F, Carter F, Camirand-Lemyre F, Lamontagne F. Blood Pressure Targets for Adults with Vasodilatory Shock - An Individual Patient Data Meta-Analysis. NEJM Evid. 2025;4:EVIDoa2400359. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Jarczak D, Kluge S, Nierhaus A. Sepsis-Pathophysiology and Therapeutic Concepts. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8:628302. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 276] [Article Influence: 55.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kimmoun A, Ducrocq N, Levy B. Mechanisms of vascular hyporesponsiveness in septic shock. Curr Vasc Pharmacol. 2013;11:139-149. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Dünser MW, Mayr AJ, Ulmer H, Knotzer H, Sumann G, Pajk W, Friesenecker B, Hasibeder WR. Arginine vasopressin in advanced vasodilatory shock: a prospective, randomized, controlled study. Circulation. 2003;107:2313-2319. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 393] [Cited by in RCA: 378] [Article Influence: 16.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Torgersen C, Dünser MW, Wenzel V, Jochberger S, Mayr V, Schmittinger CA, Lorenz I, Schmid S, Westphal M, Grander W, Luckner G. Comparing two different arginine vasopressin doses in advanced vasodilatory shock: a randomized, controlled, open-label trial. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36:57-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Bassi E, Park M, Azevedo LC. Therapeutic strategies for high-dose vasopressor-dependent shock. Crit Care Res Pract. 2013;2013:654708. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Brand DA, Patrick PA, Berger JT, Ibrahim M, Matela A, Upadhyay S, Spiegler P. Intensity of Vasopressor Therapy for Septic Shock and the Risk of In-Hospital Death. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017;53:938-943. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Liu SF, Malik AB. NF-kappa B activation as a pathological mechanism of septic shock and inflammation. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006;290:L622-L645. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 516] [Cited by in RCA: 603] [Article Influence: 30.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Nedeva C, Menassa J, Puthalakath H. Sepsis: Inflammation Is a Necessary Evil. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2019;7:108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 241] [Article Influence: 34.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Bernard GR, Reines HD, Halushka PV, Higgins SB, Metz CA, Swindell BB, Wright PE, Watts FL, Vrbanac JJ. Prostacyclin and thromboxane A2 formation is increased in human sepsis syndrome. Effects of cyclooxygenase inhibition. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991;144:1095-1101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kirkebøen KA, Strand OA. The role of nitric oxide in sepsis--an overview. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1999;43:275-288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 185] [Cited by in RCA: 198] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lambden S, Creagh-Brown BC, Hunt J, Summers C, Forni LG. Definitions and pathophysiology of vasoplegic shock. Crit Care. 2018;22:174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 163] [Article Influence: 20.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Flemyng E, Moore TH, Boutron I, Higgins JP, Hróbjartsson A, Nejstgaard CH, Dwan K. Using Risk of Bias 2 to assess results from randomised controlled trials: guidance from Cochrane. BMJ Evid Based Med. 2023;28:260-266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Minozzi S, Cinquini M, Gianola S, Gonzalez-Lorenzo M, Banzi R. The revised Cochrane risk of bias tool for randomized trials (RoB 2) showed low interrater reliability and challenges in its application. J Clin Epidemiol. 2020;126:37-44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 290] [Article Influence: 48.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Lyu QQ, Zheng RQ, Chen QH, Yu JQ, Shao J, Gu XH. Early administration of hydrocortisone, vitamin C, and thiamine in adult patients with septic shock: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Crit Care. 2022;26:295. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ibarra-Estrada M, Kattan E, Aguilera-González P, Sandoval-Plascencia L, Rico-Jauregui U, Gómez-Partida CA, Ortiz-Macías IX, López-Pulgarín JA, Chávez-Peña Q, Mijangos-Méndez JC, Aguirre-Avalos G, Hernández G. Early adjunctive methylene blue in patients with septic shock: a randomized controlled trial. Crit Care. 2023;27:110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 18.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Hajjar LA, Zambolim C, Belletti A, de Almeida JP, Gordon AC, Oliveira G, Park CHL, Fukushima JT, Rizk SI, Szeles TF, Dos Santos Neto NC, Filho RK, Galas FRBG, Landoni G. Vasopressin Versus Norepinephrine for the Management of Septic Shock in Cancer Patients: The VANCS II Randomized Clinical Trial. Crit Care Med. 2019;47:1743-1750. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Moskowitz A, Huang DT, Hou PC, Gong J, Doshi PB, Grossestreuer AV, Andersen LW, Ngo L, Sherwin RL, Berg KM, Chase M, Cocchi MN, McCannon JB, Hershey M, Hilewitz A, Korotun M, Becker LB, Otero RM, Uduman J, Sen A, Donnino MW; ACTS Clinical Trial Investigators. Effect of Ascorbic Acid, Corticosteroids, and Thiamine on Organ Injury in Septic Shock: The ACTS Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2020;324:642-650. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 186] [Article Influence: 31.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Fujii T, Luethi N, Young PJ, Frei DR, Eastwood GM, French CJ, Deane AM, Shehabi Y, Hajjar LA, Oliveira G, Udy AA, Orford N, Edney SJ, Hunt AL, Judd HL, Bitker L, Cioccari L, Naorungroj T, Yanase F, Bates S, McGain F, Hudson EP, Al-Bassam W, Dwivedi DB, Peppin C, McCracken P, Orosz J, Bailey M, Bellomo R; VITAMINS Trial Investigators. Effect of Vitamin C, Hydrocortisone, and Thiamine vs Hydrocortisone Alone on Time Alive and Free of Vasopressor Support Among Patients With Septic Shock: The VITAMINS Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2020;323:423-431. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 364] [Cited by in RCA: 351] [Article Influence: 58.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Sevransky JE, Rothman RE, Hager DN, Bernard GR, Brown SM, Buchman TG, Busse LW, Coopersmith CM, DeWilde C, Ely EW, Eyzaguirre LM, Fowler AA, Gaieski DF, Gong MN, Hall A, Hinson JS, Hooper MH, Kelen GD, Khan A, Levine MA, Lewis RJ, Lindsell CJ, Marlin JS, McGlothlin A, Moore BL, Nugent KL, Nwosu S, Polito CC, Rice TW, Ricketts EP, Rudolph CC, Sanfilippo F, Viele K, Martin GS, Wright DW; VICTAS Investigators. Effect of Vitamin C, Thiamine, and Hydrocortisone on Ventilator- and Vasopressor-Free Days in Patients With Sepsis: The VICTAS Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2021;325:742-750. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 209] [Article Influence: 41.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Wang J, Shi M, Huang L, Li Q, Meng S, Xu J, Xue M, Xie J, Liu S, Huang Y. Addition of terlipressin to norepinephrine in septic shock and effect of renal perfusion: a pilot study. Ren Fail. 2022;44:1207-1215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Cherukuri L, Gewirtz G, Osea K, Tayek JA. Vitamin A treatment for severe sepsis in humans; a prospective randomized double blind placebo-controlled clinical trial. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2019;29:49-51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Douglas IS, Alapat PM, Corl KA, Exline MC, Forni LG, Holder AL, Kaufman DA, Khan A, Levy MM, Martin GS, Sahatjian JA, Seeley E, Self WH, Weingarten JA, Williams M, Hansell DM. Fluid Response Evaluation in Sepsis Hypotension and Shock: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Chest. 2020;158:1431-1445. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 167] [Article Influence: 27.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Morelli A, Ertmer C, Lange M, Dünser M, Rehberg S, Van Aken H, Pietropaoli P, Westphal M. Effects of short-term simultaneous infusion of dobutamine and terlipressin in patients with septic shock: the DOBUPRESS study. Br J Anaesth. 2008;100:494-503. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Albanèse J, Leone M, Delmas A, Martin C. Terlipressin or norepinephrine in hyperdynamic septic shock: a prospective, randomized study. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:1897-1902. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 149] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Hyvernat H, Barel R, Gentilhomme A, Césari-Giordani JF, Freche A, Kaidomar M, Goubaux B, Pradier C, Dellamonica J, Bernardin G. Effects of Increasing Hydrocortisone to 300 mg Per Day in the Treatment of Septic Shock: a Pilot Study. Shock. 2016;46:498-505. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Annane D, Sébille V, Charpentier C, Bollaert PE, François B, Korach JM, Capellier G, Cohen Y, Azoulay E, Troché G, Chaumet-Riffaud P, Bellissant E. Effect of treatment with low doses of hydrocortisone and fludrocortisone on mortality in patients with septic shock. JAMA. 2002;288:862-871. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2198] [Cited by in RCA: 1987] [Article Influence: 82.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Liu ZM, Chen J, Kou Q, Lin Q, Huang X, Tang Z, Kang Y, Li K, Zhou L, Song Q, Sun T, Zhao L, Wang X, He X, Wang C, Wu B, Lin J, Yuan S, Gu Q, Qian K, Shi X, Feng Y, Lin A, He X; Study Group of investigators, Guan XD. Terlipressin versus norepinephrine as infusion in patients with septic shock: a multicentre, randomised, double-blinded trial. Intensive Care Med. 2018;44:1816-1825. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Xiao X, Zhang J, Wang Y, Zhou J, Zhu Y, Jiang D, Liu L, Li T. Effects of terlipressin on patients with sepsis via improving tissue blood flow. J Surg Res. 2016;200:274-282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Keh D, Boehnke T, Weber-Cartens S, Schulz C, Ahlers O, Bercker S, Volk HD, Doecke WD, Falke KJ, Gerlach H. Immunologic and hemodynamic effects of "low-dose" hydrocortisone in septic shock: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167:512-520. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 422] [Cited by in RCA: 417] [Article Influence: 18.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Russell JA, Walley KR, Gordon AC, Cooper DJ, Hébert PC, Singer J, Holmes CL, Mehta S, Granton JT, Storms MM, Cook DJ, Presneill JJ; Dieter Ayers for the Vasopressin and Septic Shock Trial Investigators. Interaction of vasopressin infusion, corticosteroid treatment, and mortality of septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:811-818. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Russell JA, Walley KR, Singer J, Gordon AC, Hébert PC, Cooper DJ, Holmes CL, Mehta S, Granton JT, Storms MM, Cook DJ, Presneill JJ, Ayers D; VASST Investigators. Vasopressin versus norepinephrine infusion in patients with septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:877-887. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1191] [Cited by in RCA: 1238] [Article Influence: 68.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Venkatesh B, Finfer S, Cohen J, Rajbhandari D, Arabi Y, Bellomo R, Billot L, Correa M, Glass P, Harward M, Joyce C, Li Q, McArthur C, Perner A, Rhodes A, Thompson K, Webb S, Myburgh J; ADRENAL Trial Investigators and the Australian-New Zealand Intensive Care Society Clinical Trials Group. Adjunctive Glucocorticoid Therapy in Patients with Septic Shock. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:797-808. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 521] [Cited by in RCA: 707] [Article Influence: 88.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Annane D, Renault A, Brun-Buisson C, Megarbane B, Quenot JP, Siami S, Cariou A, Forceville X, Schwebel C, Martin C, Timsit JF, Misset B, Ali Benali M, Colin G, Souweine B, Asehnoune K, Mercier E, Chimot L, Charpentier C, François B, Boulain T, Petitpas F, Constantin JM, Dhonneur G, Baudin F, Combes A, Bohé J, Loriferne JF, Amathieu R, Cook F, Slama M, Leroy O, Capellier G, Dargent A, Hissem T, Maxime V, Bellissant E; CRICS-TRIGGERSEP Network. Hydrocortisone plus Fludrocortisone for Adults with Septic Shock. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:809-818. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 471] [Cited by in RCA: 653] [Article Influence: 81.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Morelli A, Ertmer C, Rehberg S, Lange M, Orecchioni A, Cecchini V, Bachetoni A, D'Alessandro M, Van Aken H, Pietropaoli P, Westphal M. Continuous terlipressin versus vasopressin infusion in septic shock (TERLIVAP): a randomized, controlled pilot study. Crit Care. 2009;13:R130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Lv QQ, Gu XH, Chen QH, Yu JQ, Zheng RQ. Early initiation of low-dose hydrocortisone treatment for septic shock in adults: A randomized clinical trial. Am J Emerg Med. 2017;35:1810-1814. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Yildiz O, Tanriverdi F, Simsek S, Aygen B, Kelestimur F. The effects of moderate-dose steroid therapy in sepsis: A placebo-controlled, randomized study. J Res Med Sci. 2011;16:1410-1421. [PubMed] |

| 38. | Keh D, Trips E, Marx G, Wirtz SP, Abduljawwad E, Bercker S, Bogatsch H, Briegel J, Engel C, Gerlach H, Goldmann A, Kuhn SO, Hüter L, Meier-Hellmann A, Nierhaus A, Kluge S, Lehmke J, Loeffler M, Oppert M, Resener K, Schädler D, Schuerholz T, Simon P, Weiler N, Weyland A, Reinhart K, Brunkhorst FM; SepNet-Critical Care Trials Group. Effect of Hydrocortisone on Development of Shock Among Patients With Severe Sepsis: The HYPRESS Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2016;316:1775-1785. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 165] [Cited by in RCA: 187] [Article Influence: 18.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/