Published online Dec 9, 2025. doi: 10.5492/wjccm.v14.i4.111059

Revised: July 28, 2025

Accepted: November 4, 2025

Published online: December 9, 2025

Processing time: 159 Days and 22.7 Hours

Intensive care units (ICUs) are stressful milieus for patients, particularly when under mechanical ventilation. Music is a non-pharmacological intervention that has shown a positive impact on physiological and psychological parameters in patients on mechanical ventilation.

To evaluate outcome of music therapy on patients who are critically ill to note the effect on ICU stays.

One-hundred-and-thirty-six adult patients with acute respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation for 48 hours or more were randomized into the music therapy or routine care (control) groups. Patients were assessed for weaning criteria before music therapy was given. If eligible, a 30-minute music therapy was given prior to the extubation. Vital parameters were recorded at 5-minute intervals of therapy. Visual Analog Scale (VAS)-Dyspnea and VAS-Anxiety (VAS-A) were assessed before and after therapy. Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale and Numerical Rating Scale scoring were conducted.

The difference in times of ventilator support in the music therapy intervention group (58.22 ± 14.90 hours) and the control group (56.88 ± 13.10 hours) was not statistically significant. ICU length of stay was significantly lower in the music therapy group (4.97 ± 1.70 days vs control group: 5.70 ± 1.74 days). ICU mortality was significantly lower in the music therapy group as compared with the control group (7.4% vs 19.1%; P = 0.043). At 0 minute the VAS-A scores of the music therapy (6.82 ± 1.36) and control group (7.07 ± 1.07) were comparable. During the remainder of the observation period, the VAS score of the music therapy group was significantly lower than that of the control group.

Music therapy is an inexpensive non-pharmacological intervention for patients in the ICU. However, future multicenter studies are warranted before routinely using music therapy in patients in the ICU.

Core Tip: Patients who are critically ill on mechanical ventilation are under stress and anxiety that can lead to increased intensive care unit (ICU) stay lengths and poor outcomes. Music therapy is a non-pharmacological intervention that has shown a positive impact on physiological and psychological parameters in patients on mechanical ventilation. The current study determined the effect of music therapy for patients who were critically ill on outcomes including the length of the ICU stay.

- Citation: Mukhtar S, Mustahsin M, Dubey M, Kazmi SAH, Shishir P. Effect of music therapy on outcomes of critically ill patients. World J Crit Care Med 2025; 14(4): 111059

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3141/full/v14/i4/111059.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5492/wjccm.v14.i4.111059

Intensive care units (ICUs) are stressful milieus for patients, particularly when under mechanical ventilation. Anxiety can cause harmful effects on the course of recovery and overall well-being of patients[1]. This may prolong weaning and recovery time. Music is a non-pharmacological intervention that has a positive impact on physiological and psychological parameters in patients on mechanical ventilation[2]. Music promotes relaxation via biological mechanisms that include a reduction in blood cortisol[3]. Music intervention can relieve pain and anxiety and increase comfort in patients admitted to an ICU[4]. Listening to music consistently reduces respiratory rate (RR) and systolic blood pressure (BP) and has an anxiety-reducing effect for patients on mechanical ventilation.

Continuous high doses of sedative medications can cause severe long-term psychological damage such as continued anxiety, depression, and paranoid delusions after ICU discharge[5]. Neurological impairment from sedatives can necessitate reintubation and negatively impact the weaning process[6]. Continuous sedation is a major risk factor for extubation failure. Integrative therapies such as music in addition to sedative and analgesic medications can synergistically enhance comfort and relaxation during mechanical ventilation[7]. Most patients who are critically ill on mechanical ventilation have impaired consciousness and are subject to a high degree of psychological and physical stress. Therefore, these patients may be positively impacted in their clinical course and outcome in the ICU after music therapy. Limited studies have been carried out determining the effect of music therapy on patients who are critically ill on mechanical ventilation. Hence, the present study aimed to determine the impact of music on outcomes in patients who are critically ill on mechanical ventilation.

This randomized control trial was conducted in the Division of Critical Care Medicine in the Department of Anaes

After obtaining written informed consent from patient attendants, the patients were randomly allocated using the sequentially numbered opaque sealed envelope method into two groups: (1) The experimental (music therapy) group; and (2) The conventional care (control) group. The experimental group received 30 minutes of music therapy in addition to conventional care. Only routine care was provided to the conventional group. The study subjects comprised patients from 18-60 years of age that were admitted to the ICU and were on a ventilator for at least 48 hours or more. Patients under conscious sedation and able to listen to music via headphones were included. Patients with a hearing deficit, history of chronic pain, metastasis cancer, seizures or status epilepticus, evidence of delirium, dementia, or psychiatric diagnosis were excluded. Patients requiring more than two vasopressors or on narcotic medication were also excluded.

Attendants were informed of the benefits and risks of the study. Written and informed consent was taken. A questionnaire for choice of music was completed by the attendant to choose the patient’s music. The patient was assessed for weaning criteria before the music therapy was given. If eligible, 30 minutes of music therapy was given prior to the extubation. Vital parameters were recorded at every 5 minutes during the therapy. Visual Analog Scale (VAS)-Dyspnea (VAS-D) and VAS-Anxiety (VAS-A) were assessed before and after the therapy. Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale (RAAS) and Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) scoring was conducted as well.

The sample size was calculated at the Department of Social and Preventive Medicine, Era’s Lucknow Medical College and Hospital using the formula (Bernard R): n = (σ1² + σ2²/κ) × (Z1-α/2 + Z1-β)²/Δ².

Where n: Sample size, σ: Standard deviation, ∆: Difference of means, κ: Ratio, Z1-α/2: Two-sided Z value, and Z1-β: Power. Considering 90% power with 99% confidence intervals (two-sided), the sample size was 124. Considering 10% non-response rate (attrition bias), the total sample size was 136 (68 in each group).

The data were collected and stored in Statistical Package for the Social Sciences 25.0 software (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, United States) for statistical analysis using the χ2 test, Student’s t-test, and multiple regression analysis. P < 0.05 was statistically significant.

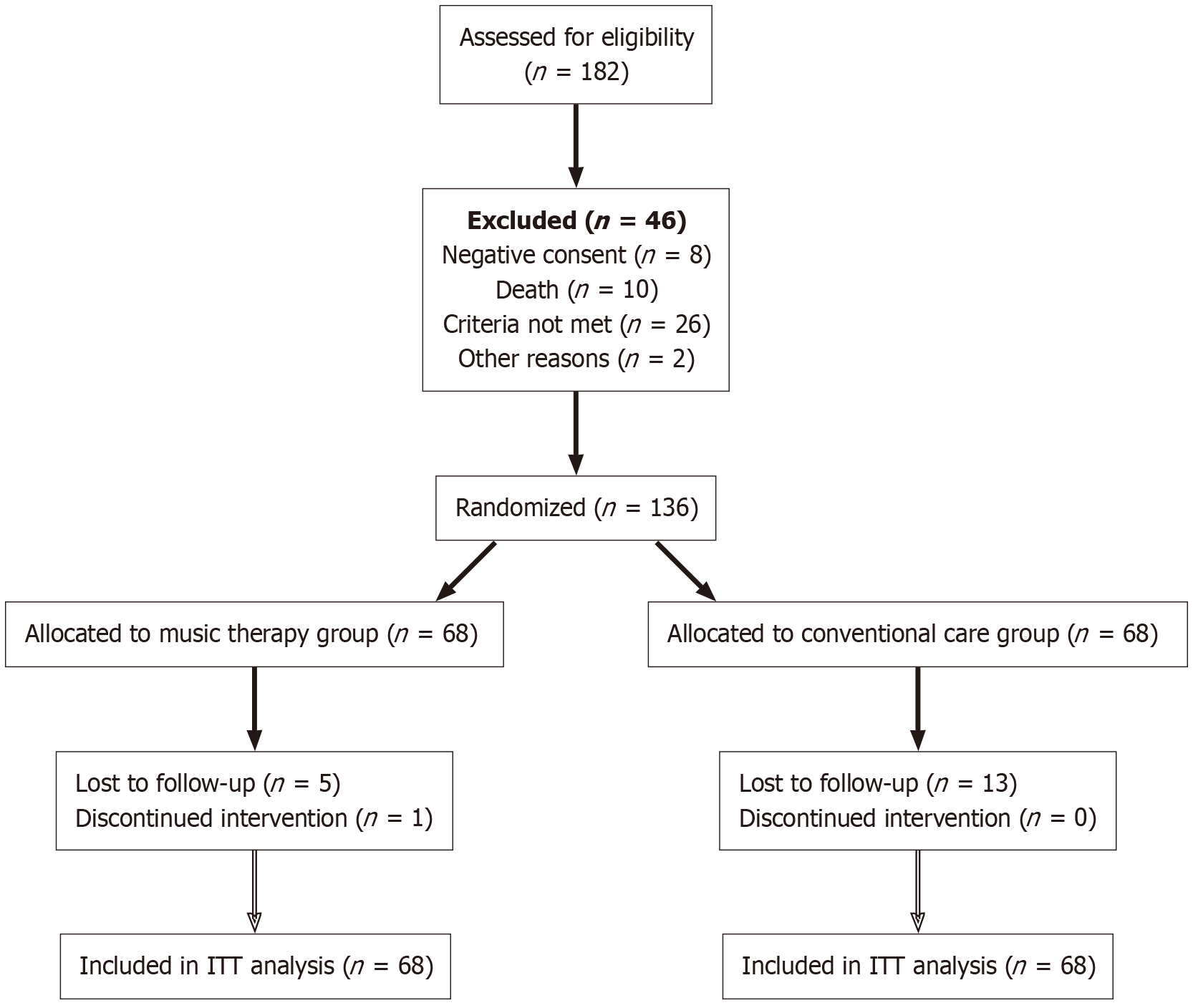

Out of 182 patients who were assessed for eligibility, 136 were randomly allocated into the music therapy group or the control group (Figure 1).

The mean age of the music therapy group (52.43 ± 10.37 years) was slightly higher than that of the control group (50.59 ± 11.54 years) (Table 1). There was a slight predominance of males (n = 74; 54.4%) in the overall study population as well as in the music therapy (55.9%) and the control (52.9%) groups. The sex ratio of the music therapy group and the control group did not show any significant difference (Table 1).

| Characteristic | Music therapy group (n = 68) | Control group (n = 68) | Statistics |

| Mean age (years) (mean ± SD) | 52.43 ± 10.37 | 50.59 ± 11.54 | t = 0.977; P = 0.330 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 38 (55.9) | 36 (52.9) | χ² = 0.119; P = 0.731 |

| Female | 30 (44.1) | 32 (47.1) | |

| Religion | |||

| Hindu | 23 (33.8) | 17 (25.0) | χ² = 1.275; P = 0.259 |

| Muslim | 45 (66.2) | 51 (75.0) | |

| Socioeconomic status | |||

| Lower | 8 (11.8) | 8 (11.8) | χ² = 1.014; P = 0.798 |

| Upper lower | 1 (1.5) | 0 (0) | |

| Lower middle | 35 (51.5) | 36 (52.9) | |

| Upper middle | 24 (35.3) | 24 (35.3) | |

| Mean Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II (mean ± SD) | 19.24 ± 2.36 | 19.49 ± 2.43 | t = 0.608; P = 0.544 |

Out of the 136 patients enrolled in the study, only 40 (29.4%) were Hindu while 96 (70.6%) were Muslims. The predominance of Muslims was observed in both the music therapy group (66.2%) and the control group (75.0%) (Table 1). The majority of the patients belonged to the lower-middle to upper-middle socioeconomic classes (n = 119; 87.5%), and the remaining patients belonged to the lower or upper-lower class. The differences in socioeconomic status of the music therapy group and the control group did not reach statistical significance (Table 1).

A multiple regression was conducted to adjust for potential confounders like baseline characteristics [age, body mass index (BMI), sex], known comorbidities, and history of chronic illness. Overall, the regression was non-significant [F (3, 26) = 13.31, P = 0.934, R2 = 0.10]. Of the predicators investigated, age [β = 0.05, t (130) = 0.592, P = 0.55], BMI [β = 0.027, t (130) = 0.296, P = 0.76], sex [β = 0.028, t (130) = 0.294, P = 0.77], known comorbidities [β = 0.024, t (130) = 0.250, P = 0.80], and history of chronic illness [β = 0.044, t (130) = 0.452, P = 0.652] were non-significant.

The difference in ventilator time for the music therapy group (58.22 ± 14.90 hours) and the control group (56.88 ± 13.10 hours) was not statistically significant (Table 2). The ICU stay for the control group (5.70 ± 1.74 days) was significantly longer than that of the music therapy group (4.97 ± 1.70 days).

| Outcome | Music therapy group (n = 68) | Control group (n = 68) | Statistics | |||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | t value | P value | |

| Ventilator time (hours) | 58.22 | 14.90 | 56.88 | 13.10 | 0.528 | 0.598 |

| Intensive care unit stay (days) | 4.97 | 1.70 | 5.70 | 0.74 | -2.299 | 0.023 |

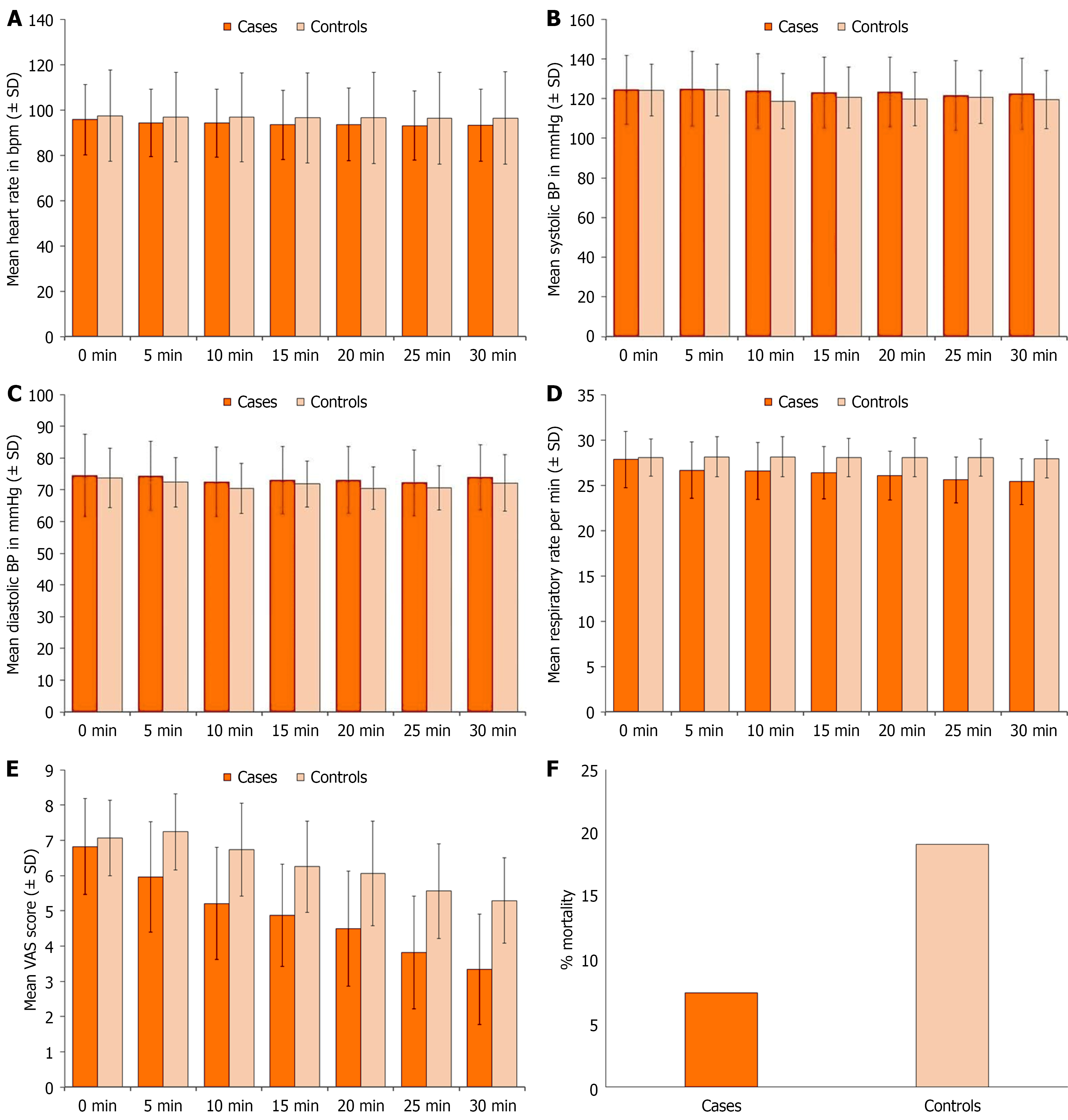

During music therapy the vitals of the patients were recorded every 5 minutes. The difference in the heart rate of the two groups was not statistically significant at any period of the observation. The heart rate of the music therapy group was at its maximum at 0 minute (95.69 ± 15.52 bpm) and at its minimum at 25 minutes (93.10 ± 15.32 bpm). The heart rate of the control group was at its maximum at 0 minute (97.43 ± 20.19 bpm) and at its minimum at 25 minutes (96.34 ± 2.21 bpm) (Table 3, Figure 2A).

| Time (minutes) | Music therapy group (n = 68) | Control group (n = 68) | Statistics | |||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | t value | P value | |

| 0 | 95.69 | 15.52 | 97.43 | 20.19 | -0.562 | 0.575 |

| 5 | 94.24 | 14.95 | 96.93 | 19.76 | -0.896 | 0.372 |

| 10 | 94.15 | 14.94 | 96.78 | 19.61 | -0.880 | 0.380 |

| 15 | 93.40 | 15.34 | 96.47 | 19.92 | -1.008 | 0.315 |

| 20 | 93.57 | 16.09 | 96.53 | 20.11 | -0.946 | 0.346 |

| 25 | 93.10 | 15.32 | 96.34 | 20.21 | -1.052 | 0.295 |

| 30 | 93.13 | 15.91 | 96.40 | 20.46 | -1.039 | 0.301 |

Systolic BP of the two groups was comparable at all periods of observation. The range of the systolic BP of the music therapy group was 121.53 ± 17.66 mmHg (25 minutes) to 124.85 ± 18.96 mmHg. The range of the systolic BP of the control group was 118.69 ± 13.91 mmHg (10 minutes) to 124.32 ± 13.04 mmHg (Table 4, Figure 2B). Diastolic BP of the two groups was comparable at all periods of observation. The diastolic BP of the music therapy group ranged between 72.25 ± 10.34 mmHg (25 minutes) and 74.44 ± 12.98 mmHg (0 minute). The diastolic BP of the control group ranged from 70.51 ± 7.89 mmHg (10 minutes) to 73.76 ± 9.39 mmHg (0 minute) (Table 5, Figure 2C).

| Time (minutes) | Music therapy group (n = 68) | Control group (n = 68) | Statistics | |||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | t value | P value | |

| 0 | 124.54 | 17.28 | 124.25 | 13.11 | 0.112 | 0.911 |

| 5 | 124.85 | 18.96 | 124.32 | 13.04 | 0.190 | 0.850 |

| 10 | 123.74 | 18.84 | 118.69 | 13.91 | 1.776 | 0.078 |

| 15 | 123.07 | 17.90 | 120.50 | 15.42 | 0.898 | 0.371 |

| 20 | 123.31 | 17.68 | 119.74 | 13.43 | 1.327 | 0.187 |

| 25 | 121.53 | 17.66 | 120.76 | 13.29 | 0.285 | 0.776 |

| 30 | 122.41 | 17.85 | 119.43 | 14.59 | 1.068 | 0.287 |

| Time (minutes) | Music therapy group (n = 68) | Control group (n = 68) | Statistics | |||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | t value | P value | |

| 0 | 74.44 | 12.98 | 73.76 | 9.39 | 0.348 | 0.728 |

| 5 | 74.32 | 10.88 | 72.38 | 7.82 | 1.195 | 0.234 |

| 10 | 72.47 | 10.93 | 70.51 | 7.89 | 1.196 | 0.234 |

| 15 | 72.97 | 10.66 | 71.87 | 7.24 | 0.706 | 0.481 |

| 20 | 73.09 | 10.60 | 70.53 | 6.62 | 1.688 | 0.094 |

| 25 | 72.25 | 10.34 | 70.65 | 7.03 | 1.057 | 0.292 |

| 30 | 73.93 | 10.19 | 72.15 | 8.91 | 1.085 | 0.280 |

Oxygen saturation levels of all the patients were maintained above 95%. At 0 minute the oxygen saturation of the two groups was comparable (97.72% ± 1.79% vs 96.40% ± 2.41%). During the remainder of the observation, the oxygen saturation level of the music therapy group was significantly higher than that of the control group. The range of oxygen saturation in the music therapy group varied between 97.66% ± 1.59% (15 minutes) and 97.85% ± 1.78%, while that of the control group ranged between 95.78 ± 2.91 (10 minutes) to 96.01% ± 2.59% (30 minutes) (Table 6).

| Time (minutes) | Music therapy group (n = 68) | Control group (n = 68) | Statistics | Confidence interval | |||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | t value | P value | ||

| 0 | 97.72 | 1.79 | 96.40 | 2.41 | 1.572 | 0.118 | 0.05-0.06 |

| 5 | 97.71 | 1.80 | 95.85 | 2.89 | 4.488 | < 0.001 | 0.00-0.02 |

| 10 | 97.82 | 1.78 | 95.78 | 2.91 | 4.942 | < 0.001 | 0.00-0.02 |

| 15 | 97.66 | 1.59 | 95.87 | 2.71 | 4.703 | < 0.001 | 0.00-0.02 |

| 20 | 97.71 | 1.83 | 95.90 | 2.55 | 4.758 | < 0.001 | 0.00-0.02 |

| 25 | 97.85 | 1.78 | 95.90 | 2.60 | 5.113 | < 0.001 | 0.00-0.02 |

| 30 | 97.82 | 1.70 | 96.01 | 2.59 | 4.808 | < 0.001 | 0.00-0.02 |

Before therapy, the difference in the RR of the music therapy group (27.84 ± 3.11 per minute) and the control group (28.06 ± 2.07 per minute) was comparable. During the remainder of the observation, the RR of the music therapy group was significantly lower than that of the control group (Table 7, Figure 2D). Body temperature was comparable at all periods of observation in both groups (Table 8).

| Time (minutes) | Music therapy group (n = 68) | Control group (n = 68) | Statistics | Confidence interval | |||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | t value | P value | ||

| 0 | 27.84 | 3.11 | 28.06 | 2.07 | -0.503 | 0.616 | 0.000-0.022 |

| 5 | 26.66 | 3.11 | 28.15 | 2.24 | -3.193 | 0.002 | 0.000-0.022 |

| 10 | 26.57 | 3.14 | 28.15 | 2.24 | -3.360 | 0.001 | 0.000-0.022 |

| 15 | 26.38 | 2.87 | 28.07 | 2.13 | -3.905 | < 0.001 | 0.000-0.022 |

| 20 | 26.09 | 2.70 | 28.06 | 2.15 | -4.711 | < 0.001 | 0.000-0.022 |

| 25 | 25.60 | 2.53 | 28.06 | 2.07 | -6.195 | < 0.001 | 0.000-0.022 |

| 30 | 25.41 | 2.53 | 27.90 | 2.09 | -6.240 | < 0.001 | 0.000-0.022 |

| Time (minutes) | Music therapy group (n = 68) | Control group (n = 68) | Statistics | |||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | t value | P value | |

| 0 | 98.59 | 0.87 | 98.41 | 0.93 | 1.129 | 0.261 |

| 5 | 98.53 | 0.81 | 98.35 | 0.88 | 1.217 | 0.226 |

| 10 | 98.53 | 0.81 | 98.35 | 0.88 | 1.217 | 0.226 |

| 15 | 98.51 | 0.82 | 98.35 | 0.88 | 1.092 | 0.277 |

| 20 | 98.51 | 0.82 | 98.35 | 0.88 | 1.092 | 0.277 |

| 25 | 98.51 | 0.82 | 98.34 | 0.84 | 1.221 | 0.224 |

| 30 | 98.51 | 0.82 | 98.34 | 0.84 | 1.221 | 0.224 |

The VAS-A scores of the music therapy group (6.82 ± 1.36) and the control group (7.07 ± 1.07) were comparable before the intervention. The VAS-A score of the music therapy group was significantly lower than that of the control group at all other observation timepoints (Table 9, Figure 2E). The VAS-D scores of the music therapy group (4.76 ± 1.09) and the control group (4.76 ± 0.90) were comparable before the intervention. No significant difference was observed between the two groups at 5 minutes and 10 minutes, although the scores were lower in the music therapy group. During the remainder of the observation period, the VAS-D score of the music therapy group was significantly lower than that of the control group (Table 10).

| Time (minutes) | Music therapy group (n = 68) | Control group (n = 68) | Statistics | Confidence interval | |||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | t value | P value | ||

| 0 | 6.82 | 1.36 | 7.07 | 1.07 | -1.192 | 0.235 | 0.000-0.022 |

| 5 | 5.96 | 1.57 | 7.24 | 1.08 | -5.539 | < 0.001 | 0.000-0.022 |

| 10 | 5.21 | 1.59 | 6.74 | 1.32 | -6.101 | < 0.001 | 0.000-0.022 |

| 15 | 4.88 | 1.45 | 6.25 | 1.30 | -5.794 | < 0.001 | 0.000-0.022 |

| 20 | 4.49 | 1.63 | 6.06 | 1.49 | -5.876 | < 0.001 | 0.000-0.022 |

| 25 | 3.82 | 1.60 | 5.56 | 1.34 | -6.847 | < 0.001 | 0.000-0.022 |

| 30 | 3.34 | 1.56 | 5.29 | 1.21 | -8.166 | < 0.001 | 0.000-0.022 |

| Time (minutes) | Music therapy group (n = 68) | Control group (n = 68) | Statistics | |||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | t value | P value | |

| 0 | 4.76 | 1.09 | 4.76 | 0.90 | < 0.001 | 1.000 |

| 5 | 4.71 | 1.08 | 4.75 | 0.90 | -0.258 | 0.797 |

| 10 | 4.24 | 0.98 | 4.54 | 0.87 | -1.943 | 0.054 |

| 15 | 3.51 | 1.00 | 4.18 | 0.85 | -4.168 | < 0.001 |

| 20 | 3.09 | 0.91 | 3.74 | 0.70 | -4.637 | < 0.001 |

| 25 | 2.94 | 0.88 | 3.60 | 0.83 | -4.511 | < 0.001 |

| 30 | 2.49 | 1.00 | 3.54 | 0.90 | -6.474 | < 0.001 |

At the 0-minute and 5-minute intervals, the NRS scores of the music therapy group (3.56 ± 0.82) and control group (3.75 ± 0.66) were comparable. During the remainder of the observation period, the NRS score of the music therapy group was significantly lower than that of the control group (Table 11). Before the intervention, the RAAS scores of the music therapy group (-3.19 ± 0.53) and the control group (-3.38 ± 0.73) were comparable. During the remainder of the observation period, the RAAS score of the music therapy group was significantly lower than that of the control group (Table 12). The mortality rate of the control group was significantly higher than that of the music therapy group (Table 13, Figure 2F).

| Time (minutes) | Music therapy group (n = 68) | Control group (n = 68) | Statistics | Confidence interval | |||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | t value | P value | ||

| 0 | 3.56 | 0.82 | 3.75 | 0.66 | -1.505 | 0.135 | 0.075-0.189 |

| 5 | 3.56 | 0.82 | 3.75 | 0.66 | -1.505 | 0.135 | 0.046-0.145 |

| 10 | 3.01 | 0.63 | 3.65 | 0.69 | -5.580 | < 0.001 | 0.046-0.145 |

| 15 | 2.54 | 0.68 | 3.65 | 0.69 | -9.425 | < 0.001 | 0.046-0.145 |

| 20 | 2.24 | 0.60 | 3.46 | 0.84 | -9.771 | < 0.001 | 0.046-0.145 |

| 25 | 2.06 | 0.77 | 3.15 | 0.72 | -8.522 | < 0.001 | 0.046-0.145 |

| 30 | 1.75 | 0.66 | 2.82 | 0.77 | -8.747 | < 0.001 | 0.046-0.145 |

| Time (minutes) | Music therapy group (n = 68) | Control group (n = 68) | Statistics | Confidence interval | |||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | t value | P value | ||

| 0 | -3.19 | 0.53 | -3.38 | 0.73 | 1.747 | 0.083 | 0.030-0.717 |

| 5 | -2.84 | 0.41 | -3.47 | 0.68 | 6.573 | < 0.001 | 0.030-0.717 |

| 10 | -2.59 | 0.60 | -3.24 | 0.76 | 5.515 | < 0.001 | 0.030-0.717 |

| 15 | -2.21 | 0.56 | -3.01 | 0.74 | 7.162 | < 0.001 | 0.030-0.717 |

| 20 | -1.88 | 0.64 | -3.01 | 0.74 | 9.551 | < 0.001 | 0.030-0.717 |

| 25 | -1.44 | 0.68 | -2.71 | 1.01 | 8.585 | < 0.001 | 0.030-0.717 |

| 30 | -0.90 | 0.85 | -2.60 | 1.04 | 10.487 | < 0.001 | 0.030-0.717 |

| Outcome | Music therapy group (n = 68) | Control group (n = 68) | Statistics | Confidence interval | |||

| n | % | n | % | χ² value | P value | ||

| Intensive care unit mortality | 5 | 7.4 | 13 | 19.1 | 4.098 | 0.043 | 0.2293-0.0047 |

The present study was carried out to assess the impact of music on the outcomes of patients who were critically ill. For this purpose, a total of 136 patients who were critically ill on mechanical ventilation were enrolled in the study and were randomized to two groups. A total of 68 patients were allocated to the intervention group and received music therapy in addition to standard ICU care, and the remaining 68 patients were allocated to the control group and received standard ICU care only.

In the present study, the ICU mortality rate was significantly lower in the music therapy group (7.4%) compared with the control group (19.1%). However, there were significant differences between the two groups for the duration of mechanical ventilation and length of ICU stay. After evaluating the literature, we did not find any reports relating music therapy with reduced ICU mortality or ventilator duration.

We used a randomized controlled design for this study. Randomized controlled studies are the hallmark of clinical research and provide the most robust clinical evidence to differentiate the efficacy between two or more drugs/in

We carried out sample size assessment based on a power analysis and maintained an adequate sample size for statistical significance (i.e. 68 patients in each group). A number of earlier studies had group sample sizes of 68 or less, and they did not face any statistical issue in studying the outcomes[10-12]. The adequacy of sample size was also determined by its ability to extend statistical matching of randomly allocated patients in two groups. In the present study, we found that both groups were comparable in this regard, and the adequacy of the sample size could also be tested on this ground.

The mean age of patients in the two groups was 52.43 years and 50.59 years, and the majority of patients in both groups (55.9% and 52.9%) were male. The effect of music therapy on patients who are critically ill has been evaluated in a diversified profile of patients in different age groups including children[13-15]. There are some studies that have been conducted in adults with a mean age of 50-60 years[16,17]. Compared with the present study in which the proportion of males was slightly higher than that of females, Mateu-Capell et al[12] had a clear predominance of males (77.3%). In another study that included patients with head trauma patients, 75% of the patients were males. Mata Ferro et al[18] in their study in the pediatric age group found that 55.2% of patients were males. In another study[19], 82.6% patients were females.

More than 75% of our patients were admitted to the ICU for respiratory reasons. Similarly, Messika et al[20] found that all the patients in their study were acute respiratory failure cases. A diverse profile of patients in the ICU was reported by Raisinghani et al[21] who enrolled patients with sepsis, congestive cardiac failure, acute respiratory distress syndrome, cerebrovascular episodes with complications, and chronic kidney disease with complications. Kobus et al[22] conducted their study among patients with chronic gastroenterological and nephrological diseases. Kakar et al[23] conducted systematic review and meta-analysis in adult critical care and surgical patients. In another study, Johnson et al[24] enrolled patients admitted to a trauma and orthopedic trauma unit. Stress levels in patients with different indications for admission to ICU may vary, and slight variances in the magnitude of stress and the resultant impact of music therapy may be envisaged in the highly diversified profiles of patients admitted to the ICU.

The majority of patients in the music therapy group (60.3%) and the control group (69.1%) had a history of chronic illness. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease was the most common chronic illness in the music therapy group (23.5%) as well as the control group (30.9%). Statistically, there was no significant difference between the two groups for the profile of chronic illnesses. Kakar et al[25] found a high prevalence of comorbidities like our study. In their study, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, and neurological chronic illnesses were seen in 61.4%, 22.7%, and 13.6% of patients in the intervention group and 50.0%, 30.0%, and 12.0% of patients in the control group, respectively. Patients in their study also had histories of chronic illnesses like chronic pain and psychiatric illness.

However, Raisinghani et al[21] reported histories of chronic illnesses in only 10% of their intervention group and 15% of their control group. Mata Ferro et al[18] found a history of chronic illness in 37.1% of their patients. In our study, a higher proportion of patients with chronic illnesses was likely due to the high prevalence of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease who were admitted to ICU following acute exacerbations.

Comorbidities like type 2 diabetes and hypertension were seen in 23.5% and 17.6% of patients in the music therapy group, respectively, and 14.7% and 13.2% of patients in the control group, respectively, in our study. Statistically, the two groups were matched for comorbidities. After reviewing the related studies, most did not report a history of comor

The mean Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II scores were similar in the two groups, reflecting a moderate risk of mortality. Compared with the present study, Raisinghani et al[21] used Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) scores to assess ICU severity and found them in the normal (> 12) range. However, in the study by Teja Chunduru and Gandhi[26] using GCS scores, the patients were in the moderate- to high-risk category. Kakar et al[25] used APACHE IV scores to evaluate the ICU severity, and they determined that their groups were in the suboptimal risk category. Due to the varying nature of scales and patients, it is difficult to compare patients in different severity categories.

The mean oxygen saturation and RAAS scores were significantly higher and RR was significantly lower in the music therapy group during the intervention. Similarly, after the 10-minute timepoint VAS-A, VAS-D, and NRS scores were lower in the music therapy group. These findings reflected that music intervention significantly impacted oxygen saturation, RR, anxiety, dyspnea, pain, and agitation-sedation.

Although pulse rate and systolic and diastolic BP remained unaffected by music in our study, Kakar et al[23] found music therapy showed significant improvement in sleep quality. In another study, sedation scores were affected positively by music therapy, and the heart beat stabilized. However, other vital parameters including oxygen saturation remained unaffected[13]. These findings are in partial agreement with our study. In a recent study conducted in children, Kobus et al[22] observed improvement in all vital signs including oxygen saturation. However, Golino et al[27] found that music therapy had a significant impact on RAAS scores but did not impact oxygen saturation. In their study in which live music therapy was used, significant reductions in agitation and heart rates were observed but no benefit on other vital parameters was seen.

We observed that music therapy had a significant impact on reducing anxiety, dyspnea, agitation, and pain scores. Thus, music had a significant relaxing impact. These findings are in agreement with a number of other studies reporting the relaxing effect of music therapy on these psychological aspects and pain scores[10,20,21,28]. Studies have indicated that music therapy can serve as a nursing strategy to modulate pain, sedation need, and anxiety in patients in the ICU[29].

Single-center design: This study was conducted at a single institution, Era’s Lucknow Medical College and Hospital in Lucknow (India). While randomized, this single-center approach may limit the generalizability of the findings to diverse patient populations and different healthcare settings as acknowledged by the authors’ call for future multicenter studies.

Limited intervention duration: The music therapy intervention consisted of a single 30-minute session administered prior to extubation. This brief, one-time exposure may not fully capture the potential benefits of music therapy as longer or repeated sessions could yield different or more sustained effects on physiological and psychological parameters.

No blinding of groups: In this study, the control group was given standard treatment by the treating clinician. No placebo equivalent like silent headphones was used. This might lead to bias related to psychological attention given to the experimental group.

Variability in music selection: While patient preference for music genre was considered by consulting attendants, the study did not specify or analyze the types/genres of music used. This variability could introduce an uncontrolled factor in the intervention, making it difficult to determine if specific musical characteristics are more effective than others.

The study emphasized that music therapy is an inexpensive non-pharmacological intervention suitable for patients who are critically ill in the ICU. This aligns with previous research suggesting the ability of music to promote relaxation by reducing cortisol levels and to relieve pain and anxiety in the ICU. However, the findings of this study are preliminary, and future multicenter studies are warranted before the routine use of music therapy in patients who are critically ill.

| 1. | Mofredj A, Alaya S, Tassaioust K, Bahloul H, Mrabet A. Music therapy, a review of the potential therapeutic benefits for the critically ill. J Crit Care. 2016;35:195-199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Hetland B, Lindquist R, Chlan LL. The influence of music during mechanical ventilation and weaning from mechanical ventilation: A review. Heart Lung. 2015;44:416-425. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Linnemann A, Ditzen B, Strahler J, Doerr JM, Nater UM. Music listening as a means of stress reduction in daily life. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2015;60:82-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Seyffert S, Moiz S, Coghlan M, Balozian P, Nasser J, Rached EA, Jamil Y, Naqvi K, Rawlings L, Perkins AJ, Gao S, Hunter JD 3rd, Khan S, Heiderscheit A, Chlan LL, Khan B. Decreasing delirium through music listening (DDM) in critically ill, mechanically ventilated older adults in the intensive care unit: a two-arm, parallel-group, randomized clinical trial. Trials. 2022;23:576. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Bradt J, Dileo C. Music interventions for mechanically ventilated patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2014:CD006902. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Nunes SL, Forsberg S, Blomqvist H, Berggren L, Sörberg M, Sarapohja T, Wickerts CJ. Effect of Sedation Regimen on Weaning from Mechanical Ventilation in the Intensive Care Unit. Clin Drug Investig. 2018;38:535-543. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Avcı A, Kaplan Serin E. The effect of music on pain in mechanically ventilated patients: A Systematic review. Nurs Crit Care. 2025;30:e13270. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sibbald B, Roland M. Understanding controlled trials. Why are randomised controlled trials important? BMJ. 1998;316:201. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 435] [Cited by in RCA: 464] [Article Influence: 16.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Stang A. Randomized controlled trials-an indispensible part of clinical research. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2011;108:661-662. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lee CH, Lee CY, Hsu MY, Lai CL, Sung YH, Lin CY, Lin LY. Effects of Music Intervention on State Anxiety and Physiological Indices in Patients Undergoing Mechanical Ventilation in the Intensive Care Unit. Biol Res Nurs. 2017;19:137-144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Küçük Alemdar D, Bulut A, Yilmaz G. Impact of music therapy and hand massage in the pediatric intensive care unit on pain, fear and stress: Randomized controlled trial. J Pediatr Nurs. 2023;71:95-103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Mateu-Capell M, Arnau A, Juvinyà D, Montesinos J, Fernandez R. Sound isolation and music on the comfort of mechanically ventilated critical patients. Nurs Crit Care. 2019;24:290-298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Buzzi F, Yahya NB, Gambazza S, Binda F, Galazzi A, Ferrari A, Crespan S, Al-Atroushy HA, Cantoni BM, Laquintana D; Collaborative Group. Use of Musical Intervention in the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit of a Developing Country: A Pilot Pre-Post Study. Children (Basel). 2022;9:455. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Menza R, Howie-Esquivel J, Bongiovanni T, Tang J, Johnson JK, Leutwyler H. Personalized music for cognitive and psychological symptom management during mechanical ventilation in critical care: A qualitative analysis. PLoS One. 2024;19:e0312175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Liu MH, Zhu LH, Peng JX, Zhang XP, Xiao ZH, Liu QJ, Qiu J, Latour JM. Effect of Personalized Music Intervention in Mechanically Ventilated Children in the PICU: A Pilot Study. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2020;21:e8-e14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Hetland B, Lindquist R, Weinert CR, Peden-McAlpine C, Savik K, Chlan L. Predictive Associations of Music, Anxiety, and Sedative Exposure on Mechanical Ventilation Weaning Trials. Am J Crit Care. 2017;26:210-220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Khan SH, Xu C, Purpura R, Durrani S, Lindroth H, Wang S, Gao S, Heiderscheit A, Chlan L, Boustani M, Khan BA. Decreasing Delirium Through Music: A Randomized Pilot Trial. Am J Crit Care. 2020;29:e31-e38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Mata Ferro M, Falcó Pegueroles A, Fernández Lorenzo R, Saz Roy MÁ, Rodríguez Forner O, Estrada Jurado CM, Bonet Julià N, Geli Benito C, Hernández Hernández R, Bosch Alcaraz A. The effect of a live music therapy intervention on critically ill paediatric patients in the intensive care unit: A quasi-experimental pretest-posttest study. Aust Crit Care. 2023;36:967-973. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Ettenberger M, Casanova-Libreros R, Chávez-Chávez J, Cordoba-Silva JG, Betancourt-Zapata W, Maya R, Fandiño-Vergara LA, Valderrama M, Silva-Fajardo I, Hernández-Zambrano SM. Effect of music therapy on short-term psychological and physiological outcomes in mechanically ventilated patients: A randomized clinical pilot study. J Intensive Med. 2024;4:515-525. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Messika J, Martin Y, Maquigneau N, Puechberty C, Henry-Lagarrigue M, Stoclin A, Panneckouke N, Villard S, Dechanet A, Lafourcade A, Dreyfuss D, Hajage D, Ricard JD; MUS-IRA team; MUS-IRA Investigators:. A musical intervention for respiratory comfort during noninvasive ventilation in the ICU. Eur Respir J. 2019;53:1801873. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Raisinghani N, Jawaharani A, Acharya S, Kumar S, Gadegone A. The effect of music therapy in critically ill patients admitted to the intensive care unit of a tertiary care center. J Datta Meghe Inst Med Sci Univ. 2019;14:320. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 22. | Kobus S, Buehne AM, Kathemann S, Buescher AK, Lainka E. Effects of Music Therapy on Vital Signs in Children with Chronic Disease. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:6544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Kakar E, Venema E, Jeekel J, Klimek M, van der Jagt M. Music intervention for sleep quality in critically ill and surgical patients: a meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2021;11:e042510. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Johnson K, Fleury J, McClain D. Music intervention to prevent delirium among older patients admitted to a trauma intensive care unit and a trauma orthopaedic unit. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2018;47:7-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Kakar E, Ottens T, Stads S, Wesselius S, Gommers DAMPJ, Jeekel J, van der Jagt M. Effect of a music intervention on anxiety in adult critically ill patients: a multicenter randomized clinical trial. J Intensive Care. 2023;11:36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Teja Chunduru T, Gandhi N. Effect of Music Therapy on Vitals and GCS Scores of Patients with Traumatic Brain Injury at ICUS. Int J Sci Res. 2021;10:239-242. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 27. | Golino AJ, Leone R, Gollenberg A, Gillam A, Toone K, Samahon Y, Davis TM, Stanger D, Friesen MA, Meadows A. Receptive Music Therapy for Patients Receiving Mechanical Ventilation in the Intensive Care Unit. Am J Crit Care. 2023;32:109-115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Chahal JK, Sharma P, Sulena, Rawat H. Effect of music therapy on ICU induced anxiety and physiological parameters among ICU patients: An experimental study in a tertiary care hospital of India. Clin Epidemiol Glob Health. 2021;11:100716. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Dallı ÖE, Yıldırım Y, Aykar FŞ, Kahveci F. The effect of music on delirium, pain, sedation and anxiety in patients receiving mechanical ventilation in the intensive care unit. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2023;75:103348. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/