Published online Dec 9, 2025. doi: 10.5492/wjccm.v14.i4.110079

Revised: June 20, 2025

Accepted: September 17, 2025

Published online: December 9, 2025

Processing time: 184 Days and 3 Hours

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is the second most common presentation of trauma victims. Among the various non-neurological complications after TBI, acute kidney injury (AKI) is not uncommon.

To establish the incidence, risk factors, and predictors of AKI in TBI victims. The secondary aim was to study the impact of AKI development on the outcomes of patients with TBI.

This was a single-center retrospective cohort study of TBI victims with a Glasgow coma scale (GCS) ≤ 11 in an apex trauma center in a metropolitan city.

The incidence of AKI after TBI was 11%. The risk factors for AKI after TBI were old age (P < 0.001), comorbidities (P = 0.023), shock (P < 0.001), blood transfusion (P = 0.016), consecutive neurosurgical intervention (P = 0.029), high intracranial pressure (ICP) (P < 0.001), rhabdomyolysis (P < 0.001), and diabetes insipidus (P < 0.001). The predictors of AKI after TBI were, on point-biserial correlation: Lower GCS (rpb = -0.27, n = 331, P < 0.001); and on multivariate logistic regression: (1) Shock (odds ratio [OR]: -11.94, P < 0.001); (2) Rhabdomyolysis (OR: -7.33, P = 0.001); (3) High ICP (OR: -4.39, P = 0.018); (4) High Carlson comorbidity index (OR: -1.97, P = 0.001); and (5) High acute physiology and chronic health evaluation-2 (APACHE-2) score (OR: -1.13, P < 0.001). The phenomenon of post-TBI AKI increased the extent of stay in intensive care unit (P = 0.008), demand for ventilators (P = 0.0170), ventilator days (P < 0.001), incidence of brain death (P < 0.001), and mortality (P < 0.001).

Every tenth TBI victim suffers from AKI. AKI after TBI can be predicted by the patient's underlying comorbidities, on arrival low GCS, high APACHE-2 score, shock, rhabdomyolysis, and high ICP. The occurrence of AKI in TBI victims adversely affects outcome variables; however, this may be a reflection of the severe nature of TBI in the AKI group. New research is needed to understand the effects of AKI on outcome variables.

Core Tip: After traumatic brain injury (TBI), patients are prone to develop non-neurological complications. Intensivists play a vital role in managing patients with TBI and preventing non-neurological complications. Among various non-neurological complications after TBI, acute kidney injury (AKI) is not uncommon and can negatively affect the patient's outcome. The incidence, risk factors, and predictors of AKI events in patients with TBI are further revealed by this study. In general, the severity of injury is the main determinant of both the development of AKI and the patient's outcome after TBI.

- Citation: Wankhade BS, El Kholi MHIA, Alrais ZF, Elkhouly AES, Naidu GAK, Patel AA, Sameer M, Abbas MS, Elbasier NNF, El Hadi AF. Acute kidney injury in critically ill patients with traumatic brain injury: A single-center retrospective cohort study. World J Crit Care Med 2025; 14(4): 110079

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3141/full/v14/i4/110079.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5492/wjccm.v14.i4.110079

Traumatic injury is the sixth leading cause of death worldwide, particularly in young individuals[1]. Following fractures of long bones, traumatic brain injury (TBI) is the second most common presentation of trauma victims[2,3]. While TBI is a neurosurgical emergency, its early management heavily relies on the expertise of acute care physicians for airway control, resuscitation, and stabilization of intracranial pressure (ICP)[4]. The main aim of medical management after TBI is to prevent secondary brain insult and manage complications[5]. Common non-neurological complications that can occur after TBI include sepsis, respiratory infections, shock, respiratory failure, and acute kidney injury (AKI)[6]. The reported incidence of AKI in patients with TBI is approximately 10%, which is significantly higher than that in the general population[7-9]. The incidence of AKI events in patients with TBI has been well-documented by previous studies; however, there are still discrepancies in the risk factors and predictors of AKI after TBI[7-9]. Pathologically, the cause of AKI in TBI victims is mostly pre-renal, less frequently intrinsic renal, and rarely post-renal[7-9]. In most cases, management includes modification of pre-renal factors, and on rare occasions, patients require renal replacement therapy (RRT)[7-9]. There is sparse data available on whether AKI events in patients with TBI impact the patient's outcome in terms of neurological recovery, morbidity, and mortality[7-9].

Due to the limited research on AKI events in patients with TBI, some of the abovementioned questions remain unanswered. To fill a gap in the current literature, we conducted an observational study on TBI victims. The primary aim of this research was to establish the incidence, risk factors, and predictors of AKI in TBI victims. The secondary aim was to study the impact of AKI development on the outcomes of patients with TBI.

We conducted a retrospective cohort study at the apex trauma center (ATC) in a metropolitan city with a population of about 3.6 million. ATC is a 762-bed tertiary-level health care center with 110 intensive care unit (ICU) beds. This study was conducted after obtaining approval from the institutional review board (No. MBRU IRB-2023-323). The use of retrospective de-identified data in the study resulted in the waiver of written informed consent from patients.

The inclusion criteria were: Patients with TBI admitted to an ATC between January 1, 2019 and December 31, 2023; age 18 to 60 years; admitted within 12 hours following injury; Glasgow coma scale (GCS) score ≤ 11; and Injury Severity Score (ISS) ≤ 25. Exclusion criteria were: Patients who either had pre-existing renal dysfunction or received renal transplants; patients with direct injuries to their kidney, ureter, or bladder, which were detected clinically or radiologically; patients who were potentially brain dead; and patients who were brain dead and who opted for either organ donation or withdrawal of life-sustaining measures.

We used the patient’s electronic medical record (EMR), “epic hyperspace version 2023” (Epic Systems Corp., Madison, WI, United States) for data collection. Data were retrospectively extracted from EMRs covering the entire hospitalization period for each eligible patient. The following variables were studied in our cohort of TBI victims: (1) Patient demographics and baseline characters: Age, sex, nationality, body mass index, mechanism of injury (e.g., road traffic accidents [RTA], falls, work-related injury, assault), GCS, ISS, and acute physiology and chronic health evaluation-2 (APACHE-2); (2) Exposure to risk factors: Shock on admission, contrast use (single, multiple), neurosurgery (first, consecutive, type), blood transfusion, high ICP, rhabdomyolysis, mannitol use, diabetes insipidus, and nephrotoxic drugs. For patients who progressed to brain death, the risk factor was only considered positive if it was present before documentation of brain death. In patients who were brain dead, if brain death was documented on the 14th day of ICU stay and the patient was exposed to risk factors like rhabdomyolysis on the 3rd day of ICU stay and diabetes insipidus on the 15th day of ICU stay. In such patients, rhabdomyolysis was considered “present” because it was demonstrated before brain death documentation, and diabetes insipidus was considered “absent” because it was demonstrated after brain death documentation; (3) Presence of AKI was defined according to kidney disease: Improving global outcomes (KDIGO) 2012 clinical practice definition[10]; and (4) Patient outcome variable: Length of stay (LOS) hospital, LOS-ICU, need of mechanical ventilator (MV), ventilator days, need for tracheostomy, GCS at ICU discharge/death, need for RRT, brain death, 28-day mortality, > 28-day mortality. The following definitions were used during data collection: (1) To quantify patients underlying comorbidity, we used the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI)[11]; (2) To quantify patients on admission neurological status, the severity of the injury, and alteration in physiology, we used GCS, ISS, and APACHE-2 scores respectively[12-14]; (3) Use of contrast media was defined as intravenous administration of 70-120 mL Iohexol (Omnipaque; GE HealthCare, Shanghai, China) 350 mg/mL for computed tomography (CT) brain or CT polytrauma protocol; (4) Shock was defined as mean arterial pressure (MAP) < 65 mmHg. The shock was also considered to be present if a patient was receiving vasopressors to keep MAP ≥ 65 mmHg; (5) Blood transfusion was defined as when blood or any other blood product was administered to the patient according to common practice guidelines[15]; (6) Rhabdomyolysis was defined as an increased serum creatinine phosphokinase level of more than 6000 U/L[16]; (7) Minor neurosurgery was defined as a burr hole with either the ICP monitor or the insertion of an extra ventricular drain[17]; (8) Major neurosurgery was defined as craniotomy and decompressive craniectomy[17]. Major neurosurgery was considered when patients underwent combined minor and major neurosurgery in one setting; (9) High ICP was defined as a persistent increase in ICP over 20 mmHg for more than 30 minutes[17]; (10) Use of mannitol was defined as intravenous administration of mannitol in the concentration of 20%; (11) Nephrotoxic drugs were defined as the use of any of the following drugs: Aminoglycosides, amphotericin B, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin-receptor blockers, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, or diuretics; (12) Diabetes insipidus was defined as in a patient of hypernatremia (> 146 mmol/L) when a measured urine specific gravity was less than or equal to 1.005 and urine osmolality was ≥ 200 mOsm/kg[18]; (13) The requirement of RRT was defined when RRT was done for any of the following indications: Volume overload, metabolic acidosis, hyperkalemia, uremia, or persistent/progressive AKI[19]; and (14) Brain death was defined when it was certified in any patient by neurological criteria[20].

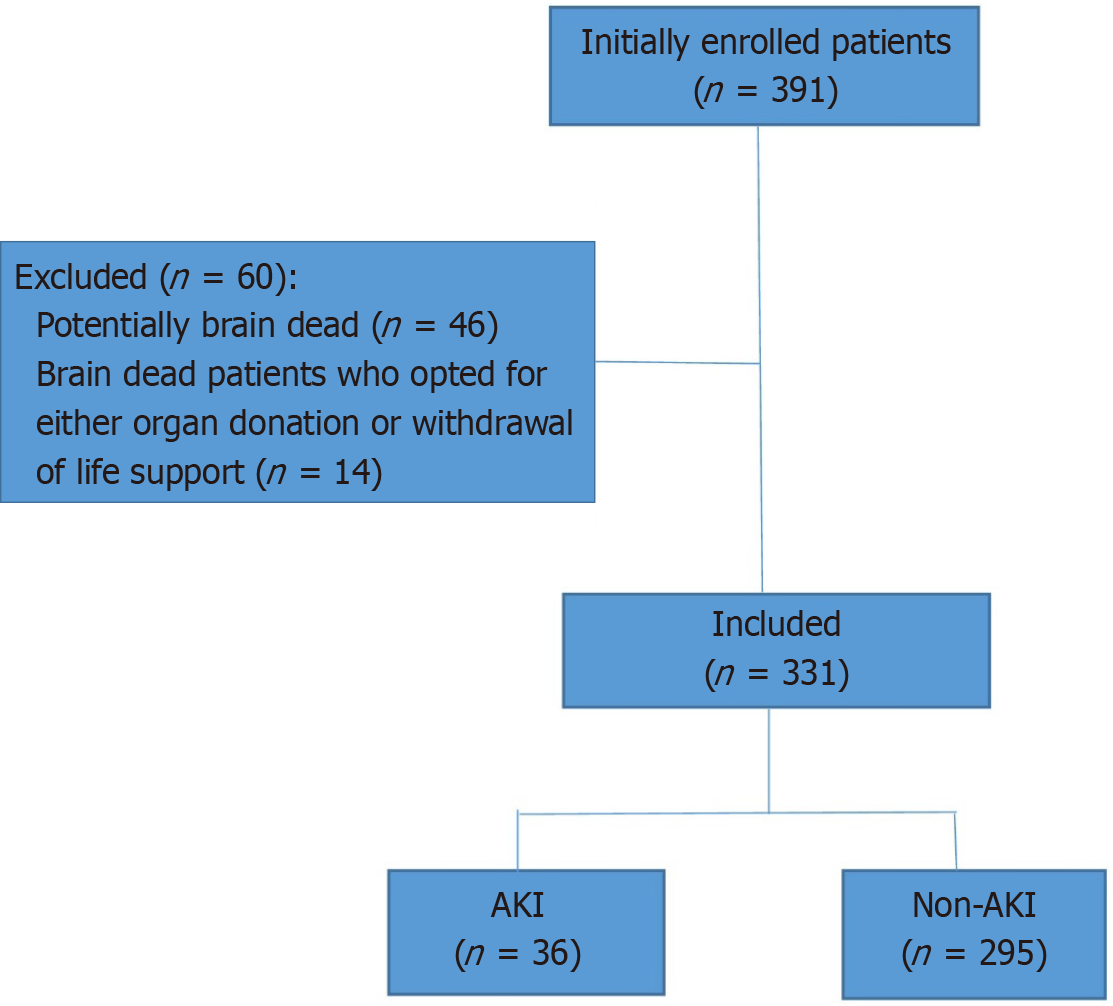

Initially, we enrolled a total of 391 patients with TBI with an admission GCS ≤ 11 in the study; however, we later excluded 60 patients who belonged to two categories: (1) Patients who were potentially brain dead, had severe TBI with GCS 3 on admission, and had the absence of at least one brain stem reflex (n = 46); and (2) Patients after the development of brain death who opted for either organ donation or withdrawal of life support (n = 14) (Figure 1). Included patients were divided into two groups, the non-AKI group, and the AKI group, according to the KDIGO 2012 clinical practice definition.

The data were collected in a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet and analyzed by IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 24.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States). Frequencies and proportions were used to represent the categorical variables and they were analyzed using the Pearson χ2 test. The independent samples test was used to analyze the mean and standard deviation for quantitative variables that had a normal distribution. The Mann-Whitney U-test was used to analyze the quantitative variables that had a skewed distribution, which was represented by the median and interquartile range. A likelihood value P < 0.05 was contemplated as the point of statistical significance, and P < 0.01 was contemplated as a high degree of statistical significance. Finally, we developed a statistically appropriate correlation and regression model using variables that have a probability value of less than 0.05 to predict AKI after TBI.

In our study, we observed 10.88% of the incidence of AKI in patients with TBI.

The demographic and baseline clinical variables are outlined in Table 1. The TBI was more common in young males after RTA. The AKI was more common in the TBI age group between 51 and 60 years (age group 51-60 years, non-AKI group 23 patients [7.8%] vs AKI group 10 patients [27.78%]; P < 0.001). Correspondingly, AKI was common in patients with comorbidities. The CCI was higher in the AKI group (0.72 ± 1.21 vs 0.23 ± 0.78, P = 0.023). AKI was particularly more frequent in patients with TBI who presented to the hospital with lower GCS scores (4 [3-8] vs 8 [6-11]; P < 0.001). The ISS score was comparable in both groups. The APACHE-2 score was significantly high in the AKI group compared to the non-AKI group (23 [15-28] vs 12 [8-18]; P < 0.001).

| Variable | Non-AKI group (n = 295) | AKI group (n = 36) | P value |

| Age (years) | < 0.0011 | ||

| 18-30 | 104 (35.25) | 19 (52.78) | |

| 31-40 | 111 (37.63) | 4 (11.11) | |

| 41-50 | 57 (19.32) | 3 (8.33) | |

| 51-60 | 23 (7.8) | 10 (27.78) | |

| Sex | 0.8311 | ||

| Male | 281 (95.25) | 34 (94.44) | |

| Female | 14 (4.75) | 02 (5.56) | |

| Nationality | 0.0911 | ||

| Emirati | 39 (13.22) | 5 (13.89) | |

| Non-Emirati | |||

| Asian | 210 (71.19) | 28 (77.78) | |

| Middle eastern | 32 (10.85) | 1 (2.78) | |

| African | 11 (3.73) | 0 (0) | |

| European-American | 3 (1.02) | 2 (5.56) | |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 24 (22-26.65) | 24.5 (22-27.03) | 0.4362 |

| Charlson comorbidity index | 0.23 ± 0.78 | 0.72 ± 1.21 | 0.0233 |

| Mechanism of injury | 0.2161 | ||

| Road traffic accident | 194 (65.76) | 21 (58.33) | |

| Fall | 83 (28.14) | 15 (41.67) | |

| Assault | 16 (5.42) | 0 (0) | |

| Work related | 2 (0.68) | 0 (0) | |

| Glasgow coma scale on admission to hospital | 8 (6-11) | 4 (3-8) | < 0.0012 |

| Injury Severity Score on admission to hospital | 17 (15-24.5) | 23 (18-25) | 0.0052 |

| Acute physiology and chronic health evaluation-2 score on admission to intensive care unit | 12 (8-18) | 23 (15-28) | < 0.0012 |

The likely risk factors for AKI after TBI are outlined in Table 2. The shock on admission was observed more frequently in patients in the AKI group than in the non-AKI group (yes: 22 [61.11%] vs 65 [22.03%], no: 14 [38.89%] vs 230 [77.97%]; P < 0.001). Contrast exposure (single or multiple times) has not shown any statistically significant difference in either group. An equal proportion of patients from either group underwent major and minor neurosurgical procedures. The difference is not statistically significant. However, patients from the AKI group underwent second neurosurgery more frequently than patients from the non-AKI group (yes: 10 [27.78%] vs 41 [13.9%], no: 26 [72.22%] vs 254 [86.1%]; P = 0.029). Patients from the AKI group had higher episodes of high ICP compared to patients from the non-AKI group (yes: 11 [64.71%] vs 20 [12.9%], no: 6 [35.29%] vs 135 [87.1%]; P < 0.001). The requirement for blood product was higher in the AKI group than in the non-AKI group (yes: 7 [19.44%] vs 22 [7.46%], no: 29 [80.56%] vs 273 [92.54%]; P = 0.016). The statistically significant number of patients from the AKI group had rhabdomyolysis in contrast with patients from the non-AKI group (yes: 12 [33.33%] vs 29 [9.83%], no: 24 [66.67%] vs 266 [90.17%]; P < 0.001). The diabetes insipidus was common in patients with AKI in contrast with patients without AKI (yes: 19 [52.78%] vs 29 [9.83%], no: 17 [47.22%] vs 266 [90.17%]; P < 0.001). Mannitol was administered to a similar proportion of patients in both groups. None of the patients from either group had received any nephrotoxic drug.

| Variable | Non-AKI group (n = 295) | AKI group (n = 36) | P value1 |

| Shock in 24 hours | < 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 65 (22.03) | 22 (61.11) | |

| No | 230 (77.97) | 14 (38.89) | |

| CT with contrast | 0.068 | ||

| Yes | 229 (77.63) | 23 (63.89) | |

| No | 66 (22.37) | 13 (36.11) | |

| Second CT with contrast | 0.23 | ||

| Yes | 43 (14.58) | 8 (22.22) | |

| No | 252 (85.42) | 28 (77.78) | |

| First neurosurgery | 0.062 | ||

| Yes | 179 (60.68) | 16 (44.44) | |

| No | 116 (39.32) | 20 (55.56) | |

| Type of first neurosurgery | Non-AKI group (n = 179) | AKI group (n = 16) | 0.3 |

| Major | 113 (63.13) | 8 (50) | |

| Minor | 66 (36.87) | 8 (50) | |

| Second neurosurgery | 0.029 | ||

| Yes | 41 (13.9) | 10 (27.78) | |

| No | 254 (86.1) | 26 (72.22) | |

| Type of second neurosurgery | Non-AKI group (n = 41) | AKI group (n = 10) | 0.007 |

| Major | 38 (92.68) | 6 (60) | |

| Minor | 3 (7.32) | 4 (40) | |

| Blood transfusion | 0.016 | ||

| Yes | 22 (7.46) | 7 (19.44) | |

| No | 273 (92.54) | 29 (80.56) | |

| ICP monitored | 0.546 | ||

| Yes | 155 (52.54) | 17 (47.22) | |

| No | 140 (47.46) | 19 (52.78) | |

| High ICP | Non-AKI group (n = 155) | AKI group (n = 17) | < 0.001 |

| Yes | 20 (12.9) | 11 (64.71) | |

| No | 135 (87.1) | 6 (35.29) | |

| Rhabdomyolysis | < 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 29 (9.83) | 12 (33.33) | |

| No | 266 (90.17) | 24 (66.67) | |

| Mannitol use | 0.229 | ||

| Yes | 47 (15.93) | 3 (8.33) | |

| No | 248 (84.07) | 33 (91.67) | |

| Diabetes insipidus | < 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 29 (9.83) | 19 (52.78) | |

| No | 266 (90.17) | 17 (47.22) |

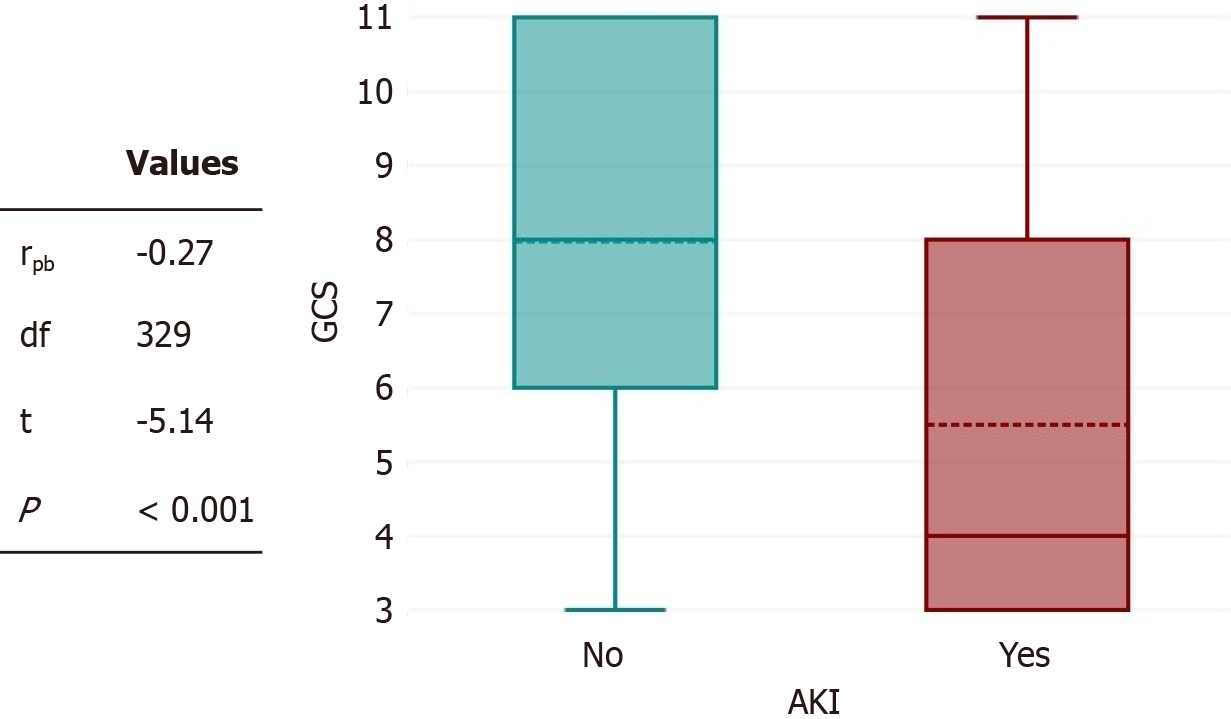

There was a negative point-biserial correlation between on-arrival GCS and AKI (Figure 2), which was statistically significant (rpb = -0.27, n = 331; P < 0.001). These results indicate that patients with better GCS scores on admission are less likely to develop AKI after TBI. On a multivariate logistic regression (Table 3.) The main predictors of AKI after TBI found were the presence of shock (odds ratio [OR]: -11.94, 95% confidence interval [CI]: -3.38 to 42.19; P < 0.001), rhabdomyolysis (OR: -7.33,95%CI: -2.28 to 23.61; P = 0.001), high ICP (OR: -4.39, 95%CI: -1.28 to 14.99; P = 0.018), high CCI (OR: -1.97, 95%CI: -1.33 to 2.92; P = 0.001), and high APACHE-2 score (OR: -1.13, 95%CI: -1.07 to 1.19; P < 0.001).

| Coefficient B | SE | Z value | P value | Odds ratio | 95%CI | |

| Constant | -6.89 | 0.95 | 7.25 | < 0.001 | 0 | 0-0.01 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | 0.68 | 0.2 | 3.37 | 0.001 | 1.97 | 1.33-2.92 |

| Acute physiology and chronic health evaluation-2 | 0.12 | 0.03 | 4.56 | < 0.001 | 1.13 | 1.07-1.19 |

| Shock | 2.48 | 0.64 | 3.85 | < 0.001 | 11.94 | 3.38-42.19 |

| Blood transfusion | -1.29 | 0.69 | 1.87 | 0.062 | 0.27 | 0.07-1.07 |

| Rhabdomyolysis | 1.99 | 0.6 | 3.34 | 0.001 | 7.33 | 2.28-23.61 |

| 2nd neurosurgery | 1.17 | 0.61 | 1.9 | 0.057 | 3.21 | 0.96-10.7 |

| High intracranial pressure | 1.48 | 0.63 | 2.36 | 0.018 | 4.39 | 1.28-14.99 |

| Diabetes insipidus | 0.87 | 0.54 | 1.62 | 0.106 | 2.38 | 0.83-6.8 |

The outcome variables are outlined in Table 4. The need for MV was significantly higher in the AKI group compared to the non-AKI group (yes: 34 [94.44%] vs 228 [77.29%], no: 2 [5.56%] vs 67 [22.71%]; P = 0.017). Similarly, patients from the AKI group spent more days on ventilators than patients from the non-AKI group (17.5 [7-24.5] vs 5 [1-12]; P < 0.001). Nevertheless, patients with or without AKI required tracheostomy in similar proportions for ventilator weaning. LOS in ICU was also significantly higher in patients who developed AKI than in patients without AKI (18 [7-24.5] vs 8 [5-17]; P = 0.008). However, LOS in the hospital was almost similar in either group. GCS at the time of death or discharge from ICU was significantly lower in the AKI group than in the non-AKI group (3 [3-3] vs 14 [11-15]; P < 0.001). A statistically significant percentage of patients from the AKI group progressed to brain death in contrast to patients from the non-AKI group (yes: 20 [55.56%] vs 18 [6.1%], no: 16 [44.44%] vs 277 [93.9%]; P < 0.001), which contributed to the high observed 28-day mortality in the AKI group in contrast with the non-AKI group (yes: 22 [61.11%] vs 22 [7.46%], no: 14 [38.89%] vs 273 [92.54%]; P < 0.001). In an almost identical way, the reported more than 28-day mortality was high in the AKI group compared with the non-AKI group (yes: 7 [50%] vs 3 [1.1%], no: 7 [50%] vs 270 [98.9%]; P < 0.001).

| Variable | Non-AKI group (n = 295) | AKI group (n = 36) | P value |

| LOS in hospital (day) | 22 (12-58) | 18 (7-41) | 0.052 |

| LOS in ICU (day) | 8 (5-17) | 18 (7-24.5) | 0.0082 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 0.0171 | ||

| Yes | 228 (77.29) | 34 (94.44) | |

| No | 67 (22.71) | 2 (5.56) | |

| Ventilator day | 5 (1-12) | 17.5 (7-24.5) | < 0.0012 |

| Glasgow coma scale at discharge or death from ICU | 14 (11-15) | 3 (3-3) | < 0.0012 |

| Tracheostomy | 0.7941 | ||

| Yes | 68 (23.05) | 9 (25) | |

| No | 227 (76.95) | 27 (75) | |

| Brain death | < 0.0011 | ||

| Yes | 18 (6.1) | 20 (55.56) | |

| No | 277 (93.9) | 16 (44.44) | |

| 28-day mortality | < 0.0011 | ||

| Yes | 22 (7.46) | 22 (61.11) | |

| No | 273 (92.54) | 14 (38.89) | |

| More than 28-day mortality | Non-AKI group (n = 273) | AKI group (n = 14) | < 0.0011 |

| Yes | 3 (1.1) | 7 (50) | |

| No | 270 (98.9) | 7 (50) |

Descriptive statistics of the AKI group are outlined in Table 5. Of a total of 36 patients with AKI, stage 1 AKI was observed in 50% (18) patients, stage 2 was observed in 25% (9) patients, and stage 3 was observed in 25% (9) patients. A total of 25% (9) patients require dialysis. A total of 39% (14) patients showed complete renal recovery. A total of 56% (20) patients progressed to brain death, which contributed to 81% mortality in the AKI group.

| Variable | Stage 1 | Stage 2 | Stage 3 |

| Number of patients (n = 36, 100%) | 18 (50) | 9 (25) | 9 (25) |

| Renal replacement therapy (n = 9, 25%) | 0 | 0 | 9 |

| Full renal recovery (n = 14, 39%) | 6 | 2 | 6 |

| Brain dead (n = 20, 56%) | 7 | 6 | 7 |

| Mortality (n = 29, 81%) | |||

| 28-day mortality | 11 | 8 | 3 |

| More than 28-day mortality | 2 | 0 | 5 |

TBI does not only affect the patient’s consciousness, but it frequently causes a rise in ICP[5]. An increase in ICP can lead to autonomic system dysfunction, sympathetic system activation, and dysregulation of the rennin-angiotensin-aldosterone axis[7-9]. This pathophysiological interplay may be responsible for the development of AKI after TBI[7-9]. Patients with TBI frequently require contrast-enhanced radiological investigation, intensive resuscitations, major surgical procedures, sedation, MV, and hemodynamic support[5]. The patients may sometimes be exposed to hepatotoxic/nephrotoxic drugs during their treatment[5]. Certain conditions are frequently observed after TBI, such as rhabdomyolysis and diabetes insipidus[21,22]. Kidneys are the most vulnerable organ of the body. AKI is not uncommon due to pathophysiological changes, management intervention, and complications associated with TBI.

According to multiple retrospective cohort studies, the incidence of AKI after TBI is approximately 10%[23-25]. In our study, we found the incidence of AKI to be about 11% (10.88%). Another important finding in our study is that AKI was more often in patients who experienced a serious TBI, as pointed out by a low GCS score on admission to the hospital. Following TBI, the GCS score provides a quick preliminary neurological evaluation of patients[12]. The GCS score helps determine the severity and management decisions, and predict a patient’s outcome after TBI[26,27]. The present research demonstrates that the GCS score on admission aids in anticipating AKI after TBI. Patients with better GCS scores are less likely to develop AKI after a TBI. APACHE-2 score within 24 hours of ICU admission is routinely employed to determine the aggressiveness of critical illness and prognosis of critically ill patients[14]. Sutiono et al[28] also indicated that the APACHE-2 scoring system can help predict ventilator-associated pneumonia after TBI. In our study, we found that patients with TBI with high ICU admission APACHE-2 scores are likely to develop AKI. Moore et al[29] also observed, an almost similar relation between high APACHE-3 score in TBI victims and development of AKI.

Diverse risk factors[7-9] have been implicated in the development of AKI after TBI[23-25]. In our study, we found the following risk factors age over 51 years, preexisting comorbidities, shock, blood transfusion, consecutive neurosurgical intervention, development of high ICP, accompanying rhabdomyolysis, and occurrence of diabetes insipidus. One of the aims of our study was to determine predictors of AKI after TBI. So, if the modifiable predictors are identified early in management, one can prevent AKI. In our study, we found six predictors: (1) Patient's underlying comorbidities; (2) On arrival low GCS; (3) On ICU admission high APACHE-2 score; (4) Shock; (5) Rhabdomyolysis; and (6) High ICP.

In our study, according to KIDCO clinical practice guidelines, stage 1 of AKI was the most observed AKI stage (50% of patients). About one-fourth of patients with AKI after TBI require an RRT. This finding corresponds with results from the “Collaborative European Neurotrauma effectiveness research in TBI” study[23] and another large-scale study done by Barea-Mendoza JA et al[24].

AKI after TBI can cause a delay in neurological recovery, which can affect a patient’s morbidity and mortality indi

Diversity in sample selection: Our patients were diverse in ethnicity and age because this study was conducted in a hospital that caters to a cosmopolitan population.

Isolated TBI: Our selection of patients was restricted to those with isolated TBI and no other significant systemic trauma (as indicated by ISS less than 25 in both groups). According to some studies, the severity of polytrauma is linked to an increase in the incidence of AKI[30]. By excluding subjects with multisystem polytrauma, we could avoid bias caused by factors associated with polytraumas. Thus, this study provides knowledge about specific aspects related to TBI.

Mortality due to brain death: Similar earlier studies endorsed that AKI after TBI is associated with increased mortality[23,24]. However, they did not specify “what was the cause of high mortality”. In our study, we specifically studied the occurrence of brain death after AKI in TBI victims. We found that the incidence of brain death was significantly higher in TBI victims after the development of AKI, which was responsible for high mortality rates among the AKI group.

No association with contrast media or mannitol: Some studies have implicated that the use of contrast or mannitol may cause AKI after TBI[23,31]. In our study, we did not find any association between the use of radiological contrast media or mannitol and the development of AKI after TBI.

Setup and resource: As AKI is not uncommon after TBI, a hospital routinely treating TBI should have a protocol for anticipation and management of AKI after TBI.

Application of care bundles: This study found three modifiable predictors for AKI after TBI shock, rhabdomyolysis, and high ICP. They can be managed through the application of care bundles and local goal-directed therapy. By that means one can easily avoid this vulnerable organ dysfunction.

This study was conducted at a single center and had a sample size of only 331 TBI patients with 36 AKI events. Also, because of the retrospective nature of this study, some biases were inevitable. Hence, implementing the results of this research in clinical practice requires caution. Our study was a record review and retrospective observational study. The observation about the adequacy of initial resuscitations and subsequent management of physiological variables are important to discovering AKI after TBI[25]. In our study protocol, we have not investigated the adequacy of resuscitations and the management of risk factors. So, it is difficult to determine whether all patients were managed uniformly or not. These factors can be possibly called confounding factors, and this aspect is a limitation in the study. Occult baseline renal dysfunction, although the patient with underlying renal ailment was excluded during case selection. But because we have not implemented any test or protocol to detect any occult renal dysfunction in the study population. Some patients with unapparent renal dysfunction or occult renal injury might be included in the study, and resulted in a possible selection bias. Outcome variables: The development of AKI harmed outcome variables after TBI. However, on admission, the GCS score was also lower in the AKI group. Patients who are admitted with lower GCS scores after TBI are more likely to experience a higher LOS-ICU, requirement of MV, ventilator days, and subsequent mortality[26,27]. It is difficult to determine whether the bad outcome in the AKI group was caused by AKI or was a reflection of lower GCS in the group. Accordingly, to determine the precise impact of AKI on outcome variables, further large-scale multicenter studies are needed. In this study, we did not study or provide any specific treatment strategies for AKI in patients with TBI.

The Incidence of AKI is about 11% in TBI victims. Patients with TBI with lower GCS scores are more likely to develop AKI. Common risk factors for AKI in TBI victims are age over 51 years, preexisting comorbidities, shock, blood transfusion, consecutive neurosurgical intervention, development of high ICP, accompanying rhabdomyolysis, and occurrence of diabetes insipidus. AKI after TBI can be predicted by the patient's underlying comorbidity, lower on-arrival GCS, higher on-ICU admission APACHE-2 score, shock, rhabdomyolysis, and high ICP. Stage 1 of AKI is most commonly the observed stage of AKI. About one-fourth of patients require dialysis. The development of AKI in TBI victims can negatively affect a patient’s morbidity and mortality. However, this negative outcome can reflect the severe nature of TBI in the AKI group. New prospective multicenter studies are required to determine the precise repercussion of the development of AKI after TBI on outcome.

| 1. | Rhee P, Joseph B, Pandit V, Aziz H, Vercruysse G, Kulvatunyou N, Friese RS. Increasing trauma deaths in the United States. Ann Surg. 2014;260:13-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 318] [Cited by in RCA: 418] [Article Influence: 34.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Majdan M, Plancikova D, Brazinova A, Rusnak M, Nieboer D, Feigin V, Maas A. Epidemiology of traumatic brain injuries in Europe: a cross-sectional analysis. Lancet Public Health. 2016;1:e76-e83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 211] [Cited by in RCA: 340] [Article Influence: 34.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Huang XF, Ma SF, Jiang XH, Song RJ, Li M, Zhang J, Sun TJ, Hu Q, Wang WR, Yu AY, Li H. Causes and global, regional, and national burdens of traumatic brain injury from 1990 to 2019. Chin J Traumatol. 2024;27:311-322. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Dixon J, Comstock G, Whitfield J, Richards D, Burkholder TW, Leifer N, Mould-Millman NK, Calvello Hynes EJ. Emergency department management of traumatic brain injuries: A resource tiered review. Afr J Emerg Med. 2020;10:159-166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Konar S, Maurya I, Shukla DP, Maurya VP, Deivasigamani B, Dikshit P, Mishra R, Agrawal A. Intensive Care Unit Management of Traumatic Brain Injury Patients. J Neurointensive Care. 2022;5:1-8. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 6. | Goyal K, Hazarika A, Khandelwal A, Sokhal N, Bindra A, Kumar N, Kedia S, Rath GP. Non- Neurological Complications after Traumatic Brain Injury: A Prospective Observational Study. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2018;22:632-638. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | De Vlieger G, Meyfroidt G. Kidney Dysfunction After Traumatic Brain Injury: Pathophysiology and General Management. Neurocrit Care. 2023;38:504-516. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Husain-Syed F, Takeuchi T, Neyra JA, Ramírez-Guerrero G, Rosner MH, Ronco C, Tolwani AJ. Acute kidney injury in neurocritical care. Crit Care. 2023;27:341. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Pesonen A, Ben-Hamouda N, Schneider A. Acute kidney injury after brain injury: does it exist? Minerva Anestesiol. 2021;87:823-827. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kellum JA, Lameire N; KDIGO AKI Guideline Work Group. Diagnosis, evaluation, and management of acute kidney injury: a KDIGO summary (Part 1). Crit Care. 2013;17:204. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1192] [Cited by in RCA: 1995] [Article Influence: 153.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Quan H, Li B, Couris CM, Fushimi K, Graham P, Hider P, Januel JM, Sundararajan V. Updating and validating the Charlson comorbidity index and score for risk adjustment in hospital discharge abstracts using data from 6 countries. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173:676-682. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2771] [Cited by in RCA: 4689] [Article Influence: 312.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Mehta R; GP trainee, Chinthapalli K; consultant neurologist. Glasgow coma scale explained. BMJ. 2019;365:l1296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Copes WS, Champion HR, Sacco WJ, Lawnick MM, Keast SL, Bain LW. The Injury Severity Score revisited. J Trauma. 1988;28:69-77. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 588] [Cited by in RCA: 630] [Article Influence: 16.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, Zimmerman JE. APACHE II: a severity of disease classification system. Crit Care Med. 1985;13:818-829. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10902] [Cited by in RCA: 11389] [Article Influence: 277.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Montgomery EY, Barrie U, Kenfack YJ, Edukugho D, Caruso JP, Rail B, Hicks WH, Oduguwa E, Pernik MN, Tao J, Mofor P, Adeyemo E, Ahmadieh TYE, Tamimi MA, Bagley CA, Bedros N, Aoun SG. Transfusion Guidelines in Traumatic Brain Injury: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Currently Available Evidence. Neurotrauma Rep. 2022;3:554-568. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Cabral BMI, Edding SN, Portocarrero JP, Lerma EV. Rhabdomyolysis. Dis Mon. 2020;66:101015. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 171] [Article Influence: 28.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Hawryluk GWJ, Rubiano AM, Totten AM, O'Reilly C, Ullman JS, Bratton SL, Chesnut R, Harris OA, Kissoon N, Shutter L, Tasker RC, Vavilala MS, Wilberger J, Wright DW, Lumba-Brown A, Ghajar J. Guidelines for the Management of Severe Traumatic Brain Injury: 2020 Update of the Decompressive Craniectomy Recommendations. Neurosurgery. 2020;87:427-434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 218] [Cited by in RCA: 284] [Article Influence: 47.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Tomkins M, Lawless S, Martin-Grace J, Sherlock M, Thompson CJ. Diagnosis and Management of Central Diabetes Insipidus in Adults. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2022;107:2701-2715. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 20.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Tandukar S, Palevsky PM. Continuous Renal Replacement Therapy: Who, When, Why, and How. Chest. 2019;155:626-638. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 200] [Article Influence: 25.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Greer DM, Shemie SD, Lewis A, Torrance S, Varelas P, Goldenberg FD, Bernat JL, Souter M, Topcuoglu MA, Alexandrov AW, Baldisseri M, Bleck T, Citerio G, Dawson R, Hoppe A, Jacobe S, Manara A, Nakagawa TA, Pope TM, Silvester W, Thomson D, Al Rahma H, Badenes R, Baker AJ, Cerny V, Chang C, Chang TR, Gnedovskaya E, Han MK, Honeybul S, Jimenez E, Kuroda Y, Liu G, Mallick UK, Marquevich V, Mejia-Mantilla J, Piradov M, Quayyum S, Shrestha GS, Su YY, Timmons SD, Teitelbaum J, Videtta W, Zirpe K, Sung G. Determination of Brain Death/Death by Neurologic Criteria: The World Brain Death Project. JAMA. 2020;324:1078-1097. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 194] [Cited by in RCA: 375] [Article Influence: 62.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Ghallab M, Bernieh B, Jamjoum S, Allam M. Rhabdomyolysis and acute renal failure in head injury patients. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 1995;6:294-297. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Capatina C, Paluzzi A, Mitchell R, Karavitaki N. Diabetes Insipidus after Traumatic Brain Injury. J Clin Med. 2015;4:1448-1462. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Robba C, Banzato E, Rebora P, Iaquaniello C, Huang CY, Wiegers EJA, Meyfroidt G, Citerio G; Collaborative European NeuroTrauma Effectiveness Research in Traumatic Brain Injury (CENTER-TBI) ICU Participants and Investigators. Acute Kidney Injury in Traumatic Brain Injury Patients: Results From the Collaborative European NeuroTrauma Effectiveness Research in Traumatic Brain Injury Study. Crit Care Med. 2021;49:112-126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Barea-Mendoza JA, Chico-Fernández M, Quintana-Díaz M, Serviá-Goixart L, Fernández-Cuervo A, Bringas-Bollada M, Ballesteros-Sanz MÁ, García-Sáez Í, Pérez-Bárcena J, Llompart-Pou JA; Neurointensive Care and Trauma Working Group of the Spanish Society of Intensive Care Medicine (SEMICYUC). Traumatic Brain Injury and Acute Kidney Injury-Outcomes and Associated Risk Factors. J Clin Med. 2022;11:7216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 25. | Anteneh ZA, Kebede SK, Azene AG. Incidence and predictors of acute kidney injury among traumatic brain injury patients in Northwest Ethiopia: a cohort study using survival analysis. BMC Nephrol. 2025;26:96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Reith FCM, Lingsma HF, Gabbe BJ, Lecky FE, Roberts I, Maas AIR. Differential effects of the Glasgow Coma Scale Score and its Components: An analysis of 54,069 patients with traumatic brain injury. Injury. 2017;48:1932-1943. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Kochar A, Borland ML, Phillips N, Dalton S, Cheek JA, Furyk J, Neutze J, Lyttle MD, Hearps S, Dalziel S, Bressan S, Oakley E, Babl FE. Association of clinically important traumatic brain injury and Glasgow Coma Scale scores in children with head injury. Emerg Med J. 2020;37:127-134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Budi Sutiono A, Zafrullah Arifin M, Adhipratama H, Hermanto Y. The utilization of APACHE II score to predict the incidence of ventilator-associated pneumonia in patients with severe traumatic brain injury: A single-center study. Interdiscip Neurosurg. 2022;28:101457. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Moore EM, Bellomo R, Nichol A, Harley N, Macisaac C, Cooper DJ. The incidence of acute kidney injury in patients with traumatic brain injury. Ren Fail. 2010;32:1060-1065. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 30. | Wankhade BS, Alrais ZF, Alrais GZ, Hadi AMA, Naidu GAK, Abbas MS, Kheir ATYA, Hadad H, Sharma S, Sait M. Epidemiology and outcome of an acute kidney injuries in the polytrauma victims admitted at the apex trauma center in Dubai. Acute Crit Care. 2023;38:217-225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (6)] |

| 31. | Kelemen JA, Kaserer A, Jensen KO, Stein P, Seifert B, Simmen HP, Spahn DR, Pape HC, Neuhaus V. Prevalence and outcome of contrast-induced nephropathy in major trauma patients. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2022;48:907-913. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/