Published online Dec 9, 2025. doi: 10.5492/wjccm.v14.i4.109786

Revised: June 17, 2025

Accepted: August 20, 2025

Published online: December 9, 2025

Processing time: 191 Days and 9.4 Hours

We present the first known case of simultaneous myocardial infarction, stroke, and bowel infarction, likely triggered by a thrombotic crisis.

A 72-year-old man was found unresponsive in his car and was diagnosed with acute inferoposterior ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) and slow atrial fibrillation (AF). A computed tomography (CT) brain scan initially ruled out stroke, and the preliminary diagnosis was cardiogenic shock, slow AF, and Killip 4 acute STEMI, complicated by lactic acidosis and delirium. The patient under

This case underscores the diagnostic challenges and complexities of managing thrombotic storms, particularly when multiple ischemic events occur simultaneously. It highlights the importance of timely diagnosis and multidisciplinary coordination in such cases. We recommend a time-sensitive management ap

Core Tip: This case describes the first known instance of simultaneous myocardial infarction, stroke, and bowel infarction, likely due to a thrombotic crisis. Synchronous cardiocerebral infarcts are rare (0.009%–0.29%) and typically affect older males. Etiology remains unclear but may involve cardiogenic shock reducing cerebral perfusion. Management requires a multidisciplinary approach. If within the thrombolysis window (4.5 hours), IV recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (0.9 mg/kg) should be given first, followed by coronary intervention. Outside this window, treatment prioritization depends on hemodynamic stability—cardiac intervention for shock, stroke management otherwise. Post-acute care involves high-dose statins if atherosclerosis is suspected and close monitoring in a high-acuity setting.

- Citation: Chan WJ, Tan TXZ, Ponampalam R, Thompson A. Thrombotic storm presenting with synchronous myocardial infarction, stroke and bowel ischaemia: A case report. World J Crit Care Med 2025; 14(4): 109786

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3141/full/v14/i4/109786.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5492/wjccm.v14.i4.109786

Simultaneous infarctions affecting multiple organ systems are rare and pose significant diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. Myocardial infarction and stroke occurring concurrently, known as cardiocerebral infarction (CCI), are already recognized as a critical condition with a reported incidence ranging from 0.009% to 0.29%[1-3,5].

This case report describes the presentation, clinical course, and management of a 72-year-old male in Singapore who was found unresponsive in his car and subsequently diagnosed with an acute inferoposterior ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), an ischemic stroke, and extensive bowel infarction. His deterioration despite aggressive medical and interventional management highlights the complexity of diagnosing and treating thrombotic crises that affect multiple vascular territories simultaneously.

Through this case, we aim to emphasize the importance of rapid, multidisciplinary assessment in cases of suspected systemic thromboembolism. This report also discusses potential pathophysiological mechanisms, diagnostic pitfalls, and treatment considerations, providing valuable insights for emergency and critical care physicians encountering similar rare but severe presentations. Additionally, we advocate for further research to establish evidence-based management strategies for thrombotic storms and simultaneous multi-organ infarctions.

In 2023, A 72-year-old Singaporean Chinese male taxi driver was conveyed via ambulance to the emergency department (ED). He was found by a passerby alone and unresponsive in his parked car. The car was switched off and there were no signs of trauma. There were also no drugs or alcohol found in the car or on the patient.

On arrival at scene, paramedics found the patient to be drowsy, with a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) of E2V2M4. The patient’s blood pressure was initially unrecordable, but he was noted to have a weak pulse.

Electronic health records revealed that he had a past medical history of diabetes, hyperlipidaemia, and gout.

No further history was available to the resuscitating team at the time of presentation as the patient was found alone.

On arrival to ED, the patient was bradycardic with a heart rate of 38 beats per minute. He was also drowsy and uncommunicative but was occasionally able to withdraw from painful stimuli (GCS E1V1M4) and appeared to be moving his right upper and lower limbs more than his left. The rest of his presenting vitals at triage were as follows: Blood pressure 105/70, respiratory rate 19, and an oxygen saturation of 100% at room air. His capillary blood glucose at presentation was 5.6 mmol/L.

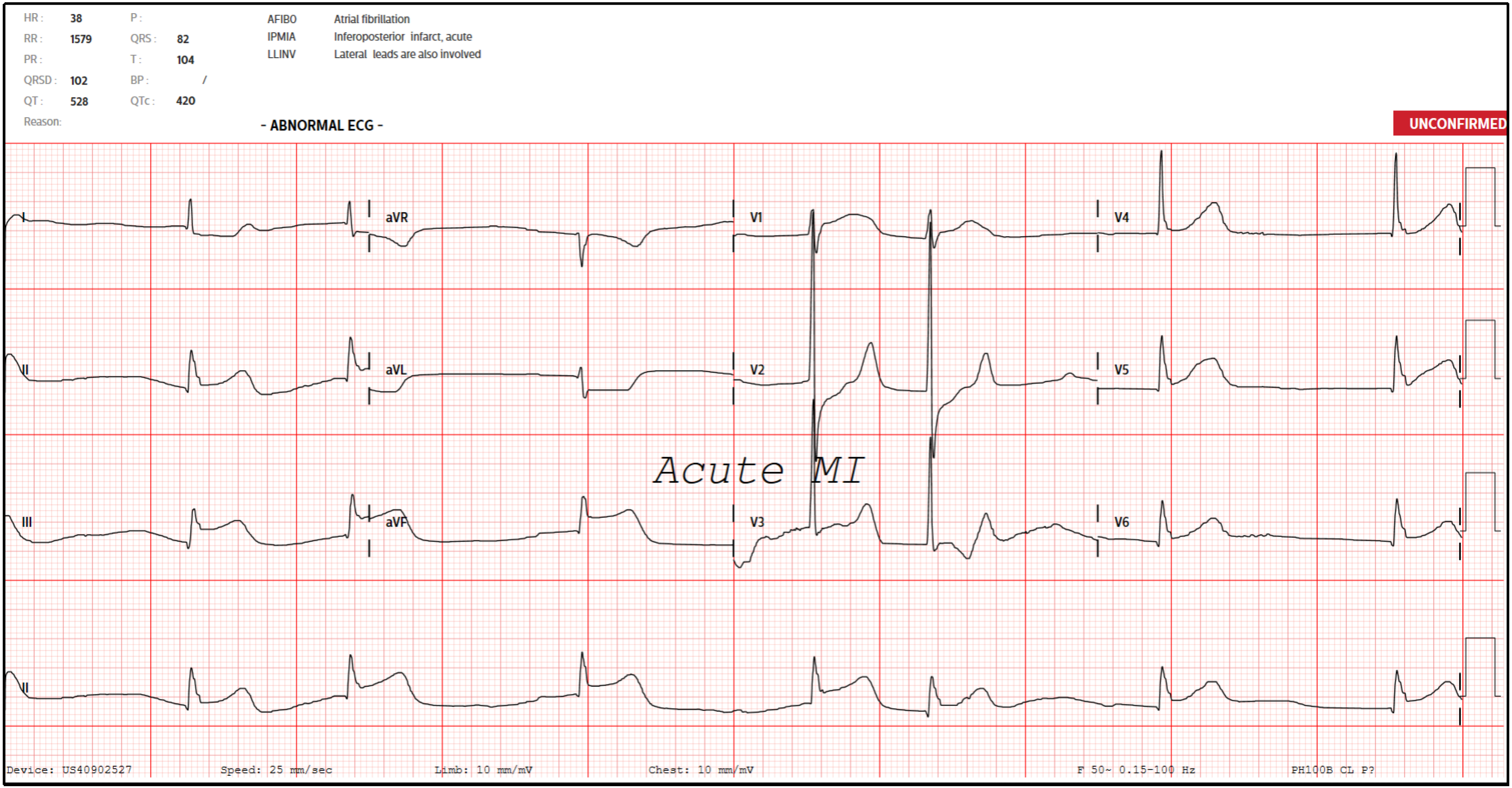

An electrocardiogram (ECG) was done (Figure 1) suggestive of acute inferoposterior STEMI and slow atrial fibrillation (AF). A bedside point-of-care ultrasound also revealed poor cardiac contractility with no significant pericardial effusion. A venous blood gas revealed that he was in concomitant respiratory and lactic acidosis. The provisional diagnosis was therefore an acute STEMI complicated by respiratory and lactic acidosis, slow AF, and reduced cardiac contractility.

His blood results subsequently returned, revealing a raised troponin of 71 ng/L, a lactate of 11.6 mmol/L, and a serum creatinine of 166 μmol/L. Calculations revealed a high anion gap metabolic acidosis attributed to high serum lactate. There was no previously documented creatinine or renal panel in the patient’s medical history, but an ultrasound of his kidneys seven years ago had noted chronic renal parenchymal disease then. As such, his raised creatinine was attributed to chronic kidney disease.

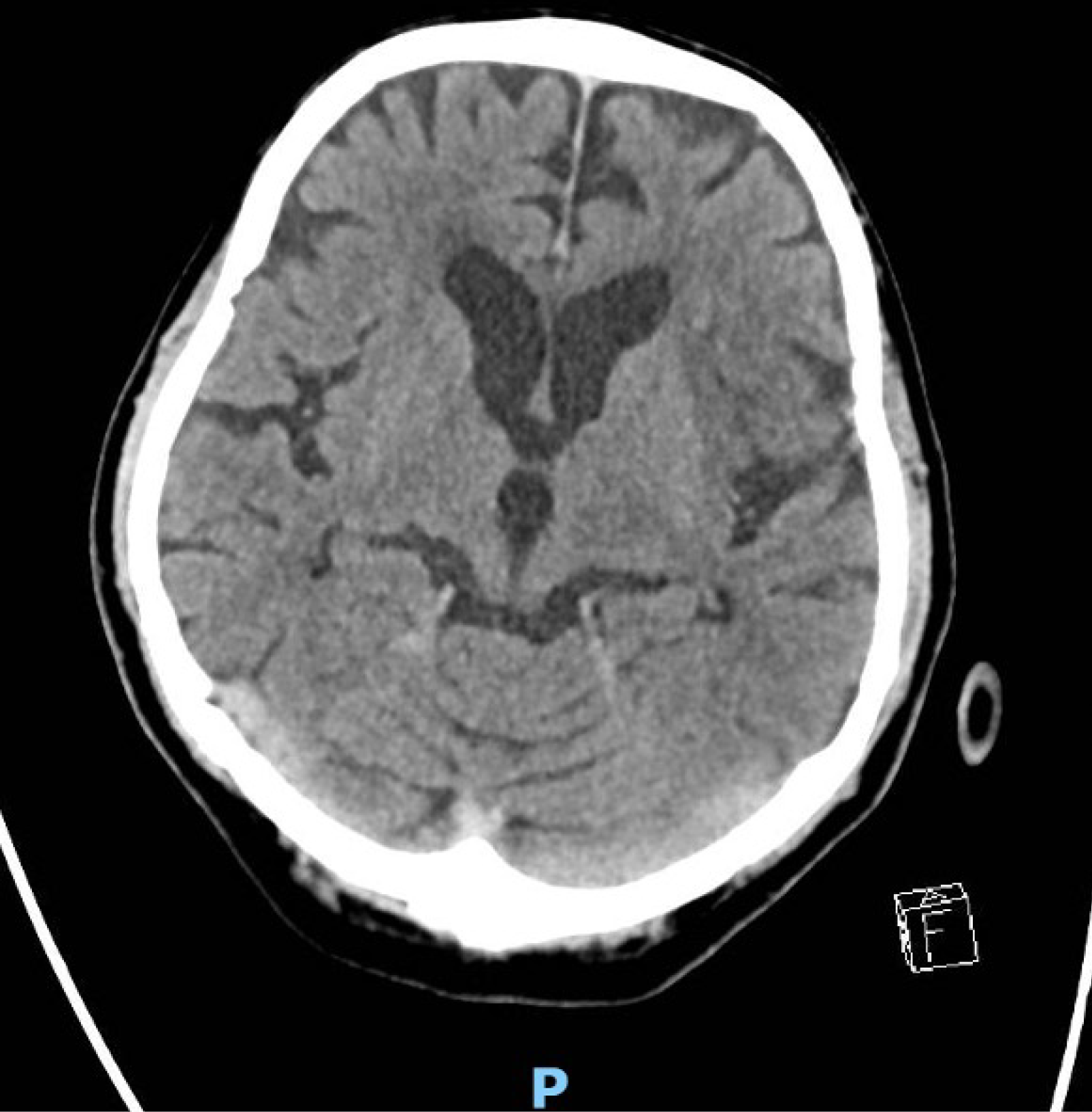

A computed tomography (CT) of the brain was done as part of work-up for low GCS at initial presentation, and it was reported no significant abnormalities with no acute intracranial haemorrhage or cerebrovascular event.

Synchronous CCI with ischaemic bowel.

Two doses of atropine and peripheral infusions of dopamine were administered with improvements to his heart rate and hemodynamic status. In view of his low GCS, the decision was made to establish a definitive airway. The patient was subsequently intubated with intravenous (IV) ketamine 100 mg and succinylcholine 100 mg. After intubation, he turned hypotensive and bradycardic again despite maximum doses of dopamine and was started on transcutaneous pacing. The initial working diagnosis was cardiogenic shock and slow AF secondary to a Killip 4 acute inferoposterior STEMI and sinoatrial node infarction, complicated by lactic acidosis and hypoactive delirium.

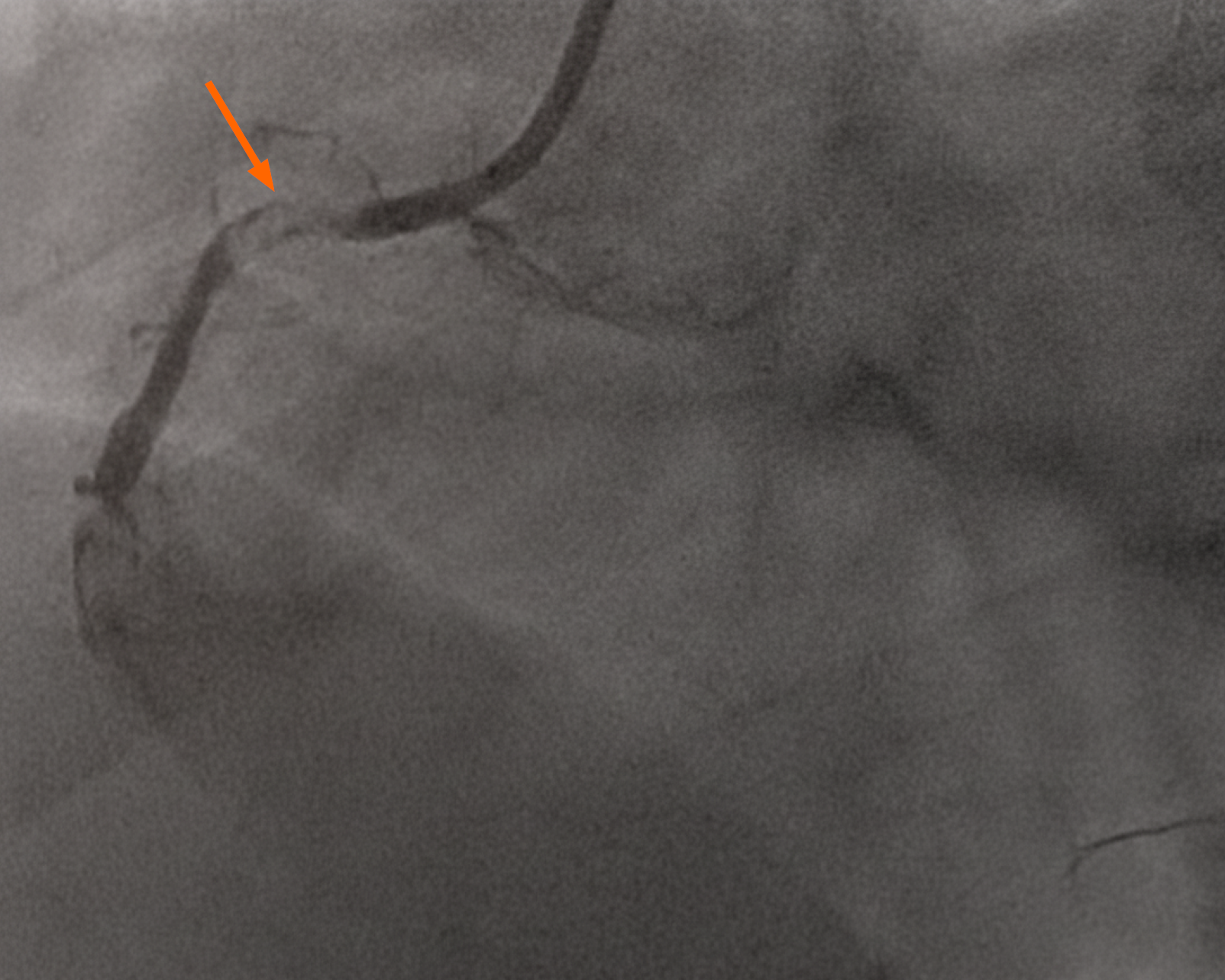

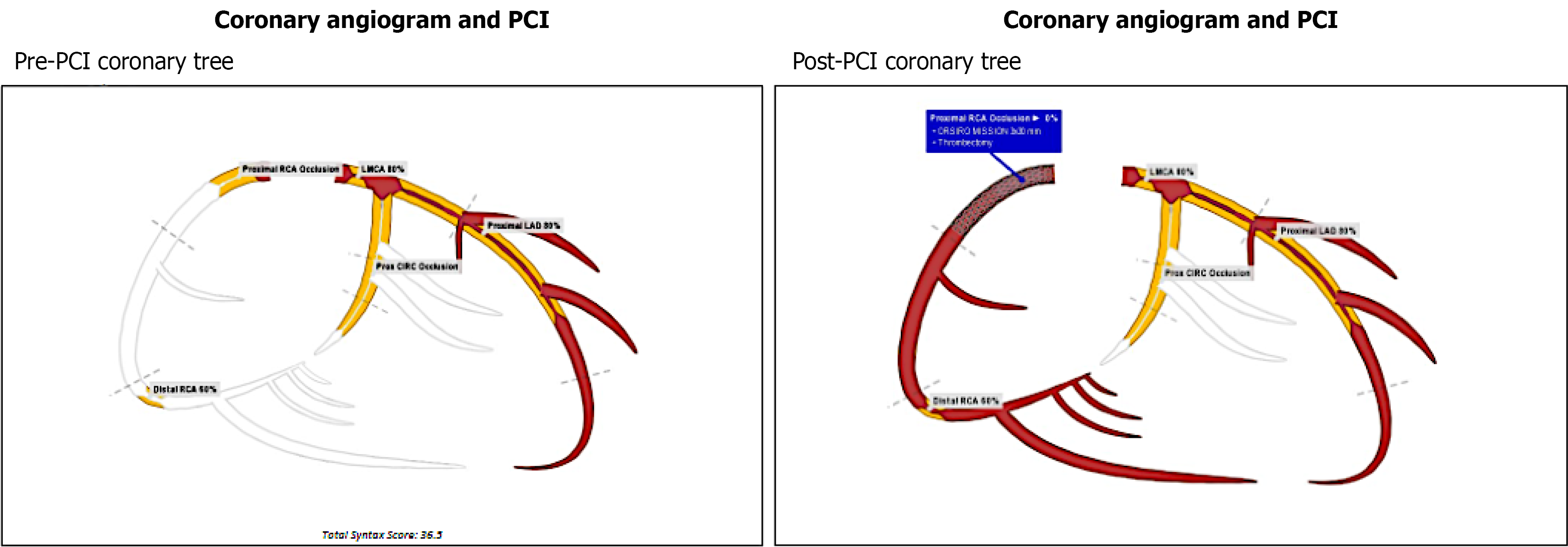

In view of the above findings, the patient was loaded with aspirin 300mg and ticagrelor 180 mg. The cardiac catheterization lab was activated, and the patient was noted to have complete occlusion of his right coronary artery (RCA), 80% thrombosis of his left main and proximal left anterior descending artery, and a diminutive and occluded left circumflex artery (Figure 2). The decision was made to proceed with a percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) to his RCA, which was noted to be the culprit lesion with a large thrombus burden (Figures 3 and 4). Multiple runs of aspiration thrombectomy was carried out with fresh red clots aspirated and IV integrillin was given during the procedure. An intra-aortic balloon pump was also inserted. Post-procedure, the patient was transferred to the Cardiac Critical Care Unit and his vitals improved significantly till he was gradually weaned off inotropes. His GCS was noted to be E1VTM5 on propofol and fentanyl infusions for sedation and endotracheal tube tolerance. He was continued on dual antiplatelets and direct oral anticoagulants. He was also started on atorvastatin 40 mg, and IV omeprazole for stress ulcer prophylaxis.

On the same day, approximately four hours post-procedure, the patient’s blood pressure dropped with a mean arterial pressure (MAP) of 55-60 mmHg. Dopamine and noradrenaline were started with the aim to keep the MAP more than 65 mmHg. The patient also started to experience runs of monomorphic non-sustained ventricular tachycardia (VT), before becoming bradycardic and then going into pulseless electrical activity (PEA). He was managed immediately as per Advanced Cardiac Life Support guidelines and two adrenaline boluses were given. Patient had a return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) after the second cycle of adrenaline but suffered another PEA collapse 10 minutes after, with a downtime of approximately two minutes. An arterial blood gas showed acidosis (pH of 7.19) and hyperkalaemia (potassium of 6.5 mEq/L). IV sodium bicarbonate was given, and the patient obtained ROSC after one cycle of adrenaline and chest compressions.

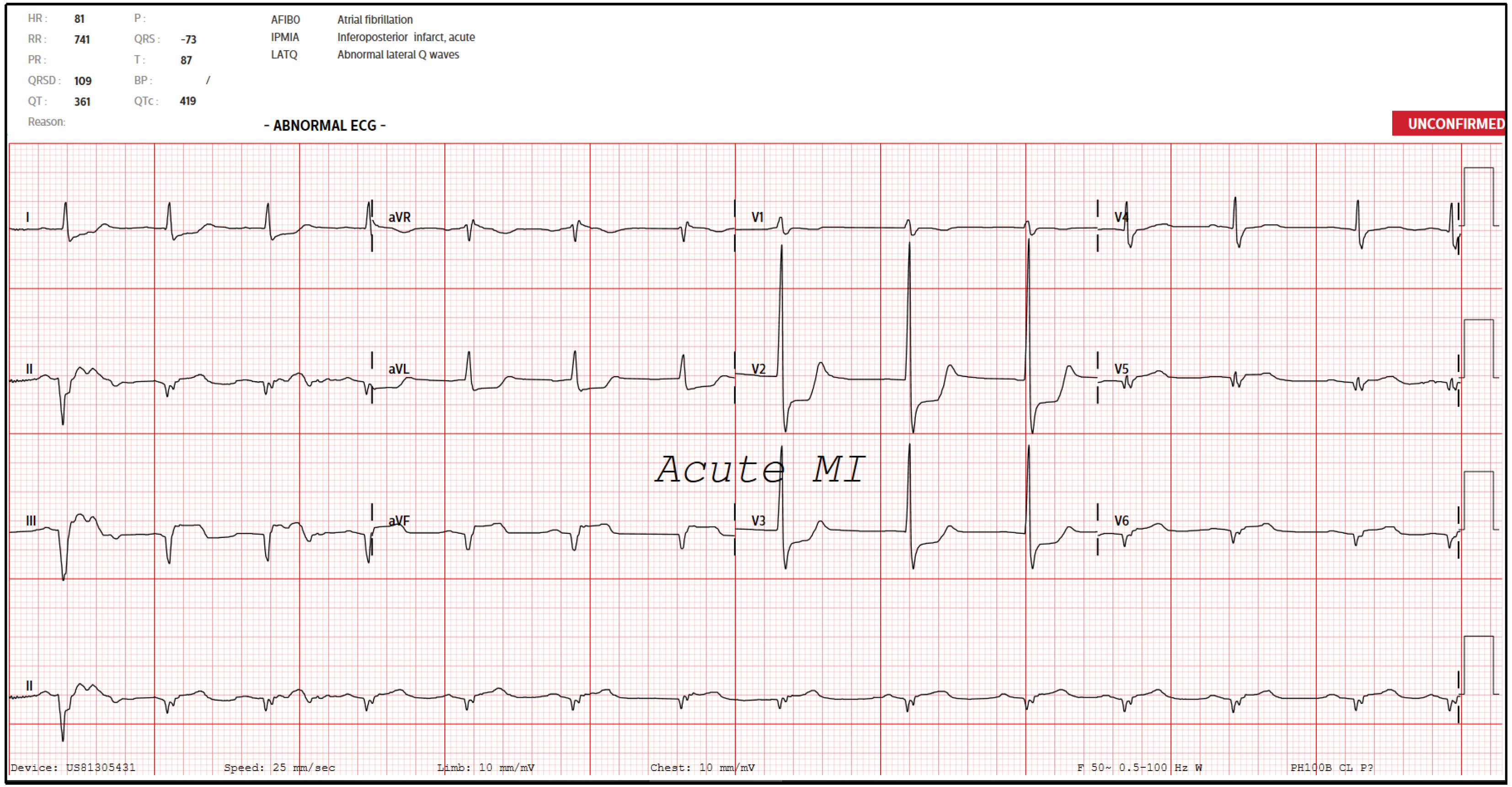

He was in atrial fibrillation post-ROSC, and IV amiodarone was started at 150 mg every 8 hourly. His post-ROSC ECG showed persistent ST segment elevations in the inferior leads with associated Q waves and ST segment depressions in V2-V3 with tall R waves (Figure 5). A repeat bedside cardiac ultrasound was done which showed an estimated ejection fraction of only 20%, with no right ventricular dilation, pericardial effusion, or severe valve regurgitation. His cardiac interventionist was notified about the above runs of sustained VT followed by episodes of short PEA collapses. These were attributed to sequelae of his STEMI, and the recommendation was for supportive management and not for relook coronary catheterization or percutaneous coronary intervention.

Post resuscitation, it was noted that his right pupil was about 4 mm and fixed, while his left pupil was 3 mm and reactive to light. A repeat CT brain was done to rule out an intracranial bleed in view of recent administration of in

Repeat blood tests on the same day showed an uptrending serum lactate (11.6 to 25.8 mmol/L), although his blood pressure maintained above 120/45 mmHg and his heart rate ranged from 71 to 95 beats per minute on dual inotropes (dopamine 5 mcg/kg/minute, noradrenaline 0.35 mcg/kg/minute). His abdomen also remained soft and non-distended, with good peripheral pulses and no signs of gangrene. A CT mesenteric angiogram was done in view of concerns of ischemic bowel, which revealed infarcts in the anterior splenic pole, left renal inferior pole, distal jejunum, splenic flexure, descending colon, and sigmoid colon (inferior mesenteric artery territory). A degree of bowel infarction was likely to have been present on presentation, explaining the initial raised lactate levels.

General surgery was consulted immediately, but the patient became increasingly drowsy and unresponsive with bilateral unresponsive pupils and increasing noradrenaline requirements (from 0.35 to 1.2 mcg/kg/minute). A third inotrope (Vasopressin) was added but despite that, continuous renal replacement therapy had to be terminated due to haemodynamic instability. Although the new neurological findings suggested a new or evolving middle cerebral artery infarct, he was deemed too haemodynamically unstable to go for a repeat CT brain. These portended an extremely poor prognosis, and he was deemed a poor candidate for any surgical intervention.

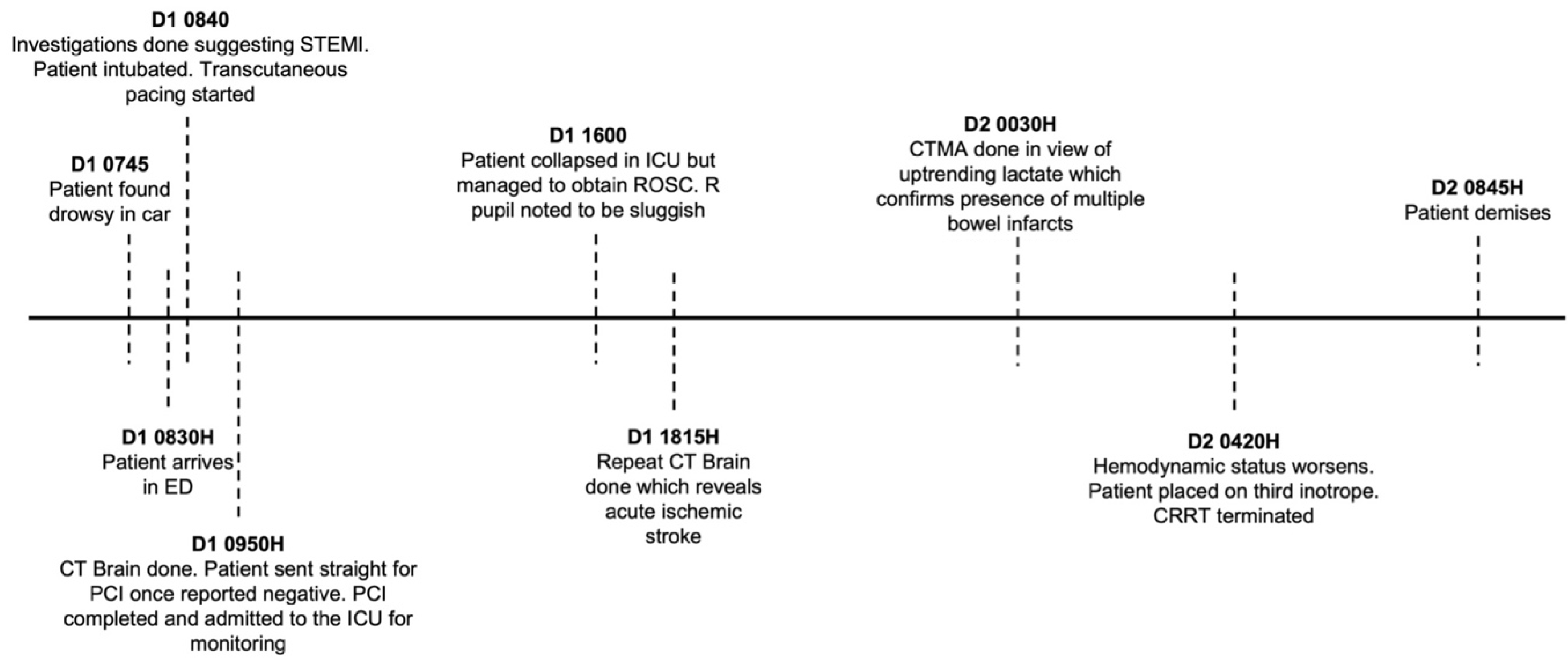

The patient’s hemodynamic status continued to deteriorate in a short span of hours. The decision was made for a do not resuscitate status. Eventually, the patient passed away approximately 48 hours since initial presentation. The sequence of events from presentation to demise is detailed in Figure 7.

As of time of writing, this is the first known case of a simultaneous myocardial infarction, stroke, and bowel infarction, likely precipitated by a thrombotic crisis. In the literature, there is only another case report of a patient who presented with simultaneous myocardial infarction, stroke, and critical limb ischemia suspected to be secondary to thrombosis of unknown etiology[1]. Synchronous myocardial infarctions and stroke, also known as CCI, are also uncommon but have been reported in literature[2]. Synchronous CCI are cases where both conditions occur simultaneously, while meta

Although rare, CCI often present critically unwell and pose complex and time-critical diagnostic and therapeutic dilemmas[5]. They often present in shock, as in this patient’s case[2,5]. Prognosis is therefore poor, evidenced by high mortality and morbidity rates (reported in-hospital mortality ranging from 23% to 45%)[2,3,5,7,8]. Clinicians should be aware of the possibility of such a phenomenon which may explain concurrent neurological and cardiac symptoms.

Several mechanisms have been postulated, which can be divided into 4 main categories – cardiac causes, cerebral causes, and non-cardiac and non-cerebral causes[8]. Cardiac causes include atherosclerosis[2], cardiac thromboemboli to the coronary and cerebral arteries[9], and massive aortic dissections extending to the coronary ostia and common carotid arteries[5,10]. Cerebral causes include insular infarcts resulting in arrhythmias and paradoxical emboli[2,11]. Non-cardiac non-cerebral causes include causes of hypotension such as septic shock resulting in global hypoperfusion[2,8] and other esoteric pathologies such as electrical injuries[12], Trousseau syndrome,[4] thromboangiitis obliterans[13], Behçet’s disease[14], rituximab therapy[15], and coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)-related coagulopathy[16]. Our patient was not known to be a smoker, did not have a history of thrombotic events, was not on any prothrombotic medications, and had tested negative for COVID-19. No tests were conducted to rule out other esoteric causes in view of medical futility.

In this case the etiology is unknown, although we suspect that cardiogenic shock and sinoatrial node dysfunction from a myocardial infarction resulted in reduced cerebral perfusion and subsequently a cerebral infarct, exacerbated by the upright position that our patient was in while seated in his car. The bowel infarcts may have been secondary to resultant atrial fibrillation or paradoxical emboli. Unfortunately, the cerebrovascular accident (CVA) was not identified until much later, after definitive management was already performed for his heart.

The inability of our patient to provide an adequate history, along with the findings of persistently low GCS and asymmetrical limb movements prompted the ED resuscitating team to order a CT Brain. If the cerebral infarct was indeed reported then, PCI might not have been performed as the insertion of a coronary stent entails the commencement of antiplatelets and direct oral anticoagulants which could exacerbate his stroke or lead to haemorrhagic conversion. The dilemma is oftentimes deciding which infarct to prioritise in terms of treatment. CCI patients have been reported to receive the whole gamut of therapeutics, ranging from interventions such as cardiac catheterization (with or without stent placement) and endovascular treatment, to medical therapy alone, down to conservative management due to poor premorbid status[2,7]. Patients have undergone cerebral artery thrombectomy first followed by PCI, while others managed by the same institution underwent PCI first[5].

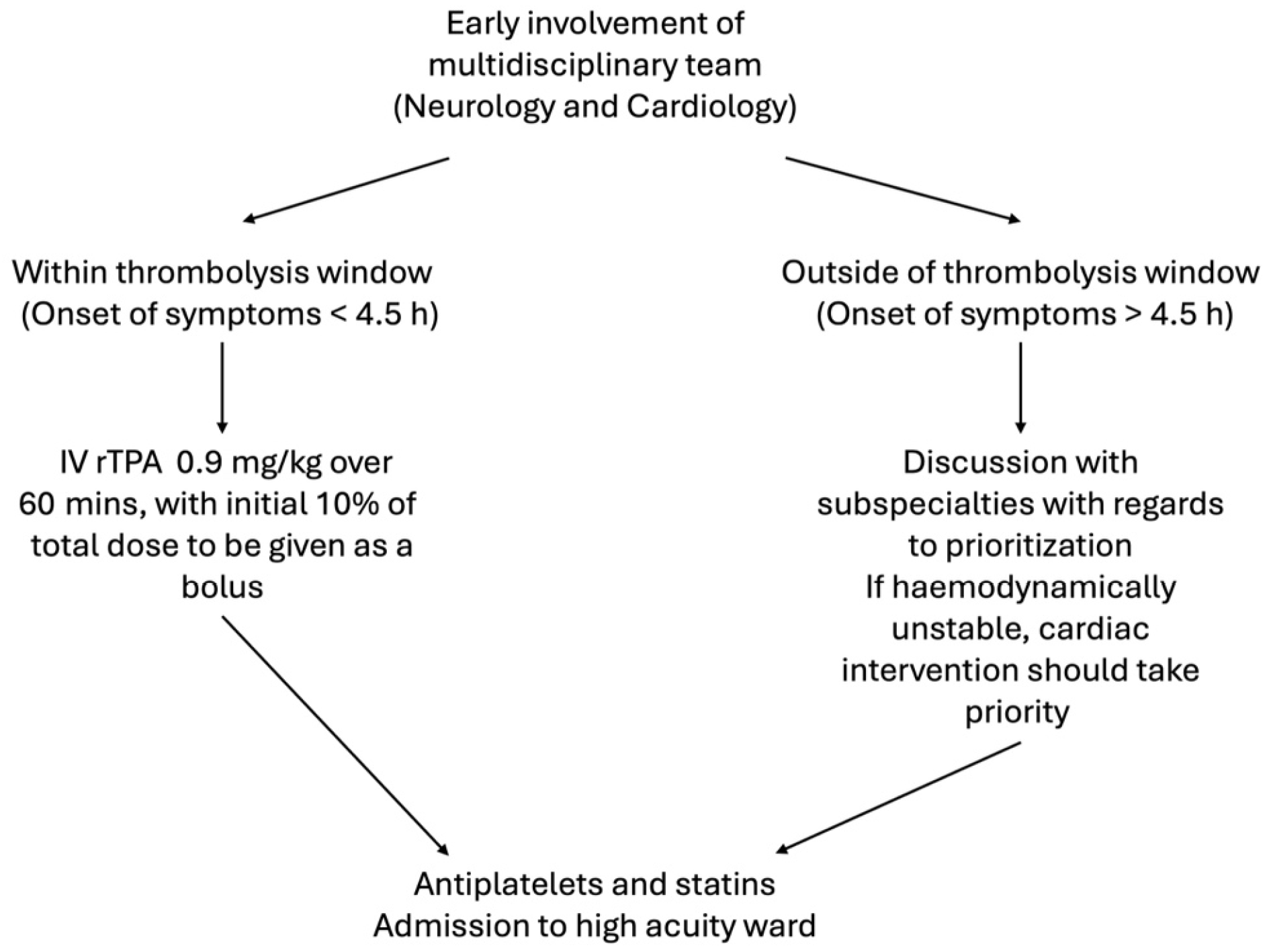

The consensus is that a multidisciplinary approach should be adopted as soon as possible, comprising of both a neurologist and a cardiologist to ascertain which infarct takes priority[5].

Following this, if the patient presented within thrombolysis window (4.5 hours), IV recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rTPA) should be commenced at the dose appropriate for cerebral ischemia (0.9mg/kg over 60 minutes with 10% of the total dose administered as an initial bolus), followed by coronary intervention and stent placement if indicated[3,8,17,18]. Cardiac doses of rTPA (1.0 mg/kg bolus) should be avoided to mitigate risks of haemorrhagic conversion of the concomitant CVA[5]. Although endorsed in the 2018 American Heart Association and American Stroke Association Guidelines[17], the added risks of this approach (risks and complications of rTPA and PCI alone notwithstanding), include cardiac wall rupture and tamponade in view of coronary intervention after rTPA administration.

If the patient presented outside thrombolysis window, it is suggested that the patient’s hemodynamic status should be utilized to guide management-if hemodynamically unstable due to cardiogenic shock or decompensated heart failure, cardiac intervention should take priority, and vice versa, although thrombolysis must be considered as it is a viable treatment option for both infarct sites[5,8,18].

Post-acute management, the patient should be monitored in a high acuity ward with continuous telemetry monitoring under the care of a multidisciplinary team including but not limited to stroke neurologists, cardiologists, intensivists, and the full spectrum of allied health and critical care professionals such as respiratory therapists, critical care nurses, and physiotherapists. Other than antiplatelets, high dose statins are also recommended if atherosclerosis is suspected as a primary or contributory mechanism[19]. Anticoagulation should also be a consideration but was not started in this case in view of concerns by the neurologists about haemorrhage conversion of his CVA. A summary of the above recommended management is attached in Figure 8.

| 1. | Simpson DL. Simultaneous acute myocardial infarction, stroke and critical limb ischaemia: an unusual presentation requiring multidisciplinary approach. BMJ Case Rep. 2021;14:e241565. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Chong CZ, Tan BY, Sia CH, Khaing T, Litt Yeo LL. Simultaneous cardiocerebral infarctions: a five-year retrospective case series reviewing natural history. Singapore Med J. 2022;63:686-690. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | de Castillo LLC, Diestro JDB, Tuazon CAM, Sy MCC, Añonuevo JC, San Jose MCZ. Cardiocerebral Infarction: A Single Institutional Series. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2021;30:105831. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Sakuta K, Mukai T, Fujii A, Makita K, Yaguchi H. Endovascular Therapy for Concurrent Cardio-Cerebral Infarction in a Patient With Trousseau Syndrome. Front Neurol. 2019;10:965. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Yeo LLL, Andersson T, Yee KW, Tan BYQ, Paliwal P, Gopinathan A, Nadarajah M, Ting E, Teoh HL, Cherian R, Lundström E, Tay ELW, Sharma VK. Synchronous cardiocerebral infarction in the era of endovascular therapy: which to treat first? J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2017;44:104-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kijpaisalratana N, Chutinet A, Suwanwela NC. Hyperacute Simultaneous Cardiocerebral Infarction: Rescuing the Brain or the Heart First? Front Neurol. 2017;8:664. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ng TP, Wong C, Leong ELE, Tan BY, Chan MY, Yeo LL, Yeo TC, Wong RC, Leow AS, Ho JS, Sia CH. Simultaneous cardio-cerebral infarction: a meta-analysis. QJM. 2022;115:374-380. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Habib M. Cardio-Cerebral infarction syndrome: definition, diagnosis, pathophysiology, and treatment. J Integr Cardiol. 2021;7. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 9. | Tokuda K, Shindo S, Yamada K, Shirakawa M, Uchida K, Horimatsu T, Ishihara M, Yoshimura S. Acute Embolic Cerebral Infarction and Coronary Artery Embolism in a Patient with Atrial Fibrillation Caused by Similar Thrombi. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2016;25:1797-1799. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Nguyen TL, Rajaratnam R. Dissecting out the cause: a case of concurrent acute myocardial infarction and stroke. BMJ Case Rep. 2011;2011:bcr0220113824. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Laowattana S, Zeger SL, Lima JA, Goodman SN, Wittstein IS, Oppenheimer SM. Left insular stroke is associated with adverse cardiac outcome. Neurology. 2006;66:477-83; discussion 463. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Verma GC, Jain G, Wahid A, Saurabh C, Sharma NK, Pathan AR, Ajmera D. Acute ischaemic stroke and acute myocardial infarction occurring together in domestic low-voltage (220-240V) electrical injury: a rare complication. J Assoc Physicians India. 2014;62:620-623. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Damanti S, Artoni A, Lucchi T, Mannucci PM, Mari D, Bergamaschini L. A thrombotic storm. Intern Emerg Med. 2017;12:69-73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Wu X, Li G, Huang X, Wang L, Liu W, Zhao Y, Zheng W. Behçet's disease complicated with thrombosis: a report of 93 Chinese cases. Medicine (Baltimore). 2014;93:e263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Karan A, Kiamos A, Reddy P. Thrombotic Storm Induced by Rituximab in a Patient With Pemphigus Vulgaris. Cureus. 2023;15:e35469. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Zebardast A, Latifi T, Shabani M, Hasanzadeh A, Danesh M, Babazadeh S, Sadeghi F. Thrombotic storm in coronavirus disease 2019: from underlying mechanisms to its management. J Med Microbiol. 2022;71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Powers WJ, Rabinstein AA, Ackerson T, Adeoye OM, Bambakidis NC, Becker K, Biller J, Brown M, Demaerschalk BM, Hoh B, Jauch EC, Kidwell CS, Leslie-Mazwi TM, Ovbiagele B, Scott PA, Sheth KN, Southerland AM, Summers DV, Tirschwell DL; American Heart Association Stroke Council. 2018 Guidelines for the Early Management of Patients With Acute Ischemic Stroke: A Guideline for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2018;49:e46-e110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2924] [Cited by in RCA: 3905] [Article Influence: 488.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 18. | Akinseye OA, Shahreyar M, Heckle MR, Khouzam RN. Simultaneous acute cardio-cerebral infarction: is there a consensus for management? Ann Transl Med. 2018;6:7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Wiggins BS, Saseen JJ, Page RL 2nd, Reed BN, Sneed K, Kostis JB, Lanfear D, Virani S, Morris PB; American Heart Association Clinical Pharmacology Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Hypertension; Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research; and Council on Functional Genomics and Translational Biology. Recommendations for Management of Clinically Significant Drug-Drug Interactions With Statins and Select Agents Used in Patients With Cardiovascular Disease: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;134:e468-e495. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 144] [Cited by in RCA: 245] [Article Influence: 24.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/