Published online Dec 9, 2025. doi: 10.5492/wjccm.v14.i4.109565

Revised: May 22, 2025

Accepted: August 5, 2025

Published online: December 9, 2025

Processing time: 198 Days and 2 Hours

A thyroid storm (TS) or thyrotoxic crisis is an infrequent, life-threatening endo

Core Tip: Endocrine emergencies are potentially reversible clinical entities if identified and picked- up early. These emer

- Citation: El-Menyar A, Khan NA, Elmenyar E, Cander B, Szarpak L, Krishnan S V, Galwnkar S, Al-Thani H. Thyroid storm-induced cardiovascular complications and modalities of therapy: Up-to-date review. World J Crit Care Med 2025; 14(4): 109565

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3141/full/v14/i4/109565.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5492/wjccm.v14.i4.109565

Endocrine emergencies though rare, can pose significant life-threatening risks. However, with early recognition and timely intervention, these conditions are often reversible and manageable. These emergencies typically arise from profound dysregulation of the hormone axis, manifesting as either severe hormone deficiency or excess. Thyroid storm (TS), also known as hyperthyroid crisis or thyrotoxic storm, is a rare but life-threatening endocrine emergency that occurs because of undiagnosed or inadequately treated hyperthyroidism[1]. The initial description of TS highlighted its asso

The incidence of TS is not precisely known, but available data suggest that it affects approximately 1% to 5.6% of hospitalized patients with underlying thyroid disorders[4,5]. However, some reports have documented rates as high as 10%[6]. In Japan, the annual incidence among hospitalized individuals has been reported at 0.20 cases per 100000 population. Notably, the average age (42 to 43 years) of those experiencing this critical condition was similar to those with thyrotoxicosis but without TS, suggesting a shared underlying risk profile[3]. Based on data from Taiwan, the incidence of TS was reported to be 0.55 cases per 100000 individuals annually, and about 6.3 cases per 100000 hospitalized patients. The 90-day mortality rate associated with TS was reported to be 8.12%[7]. A study conducted in the United States re

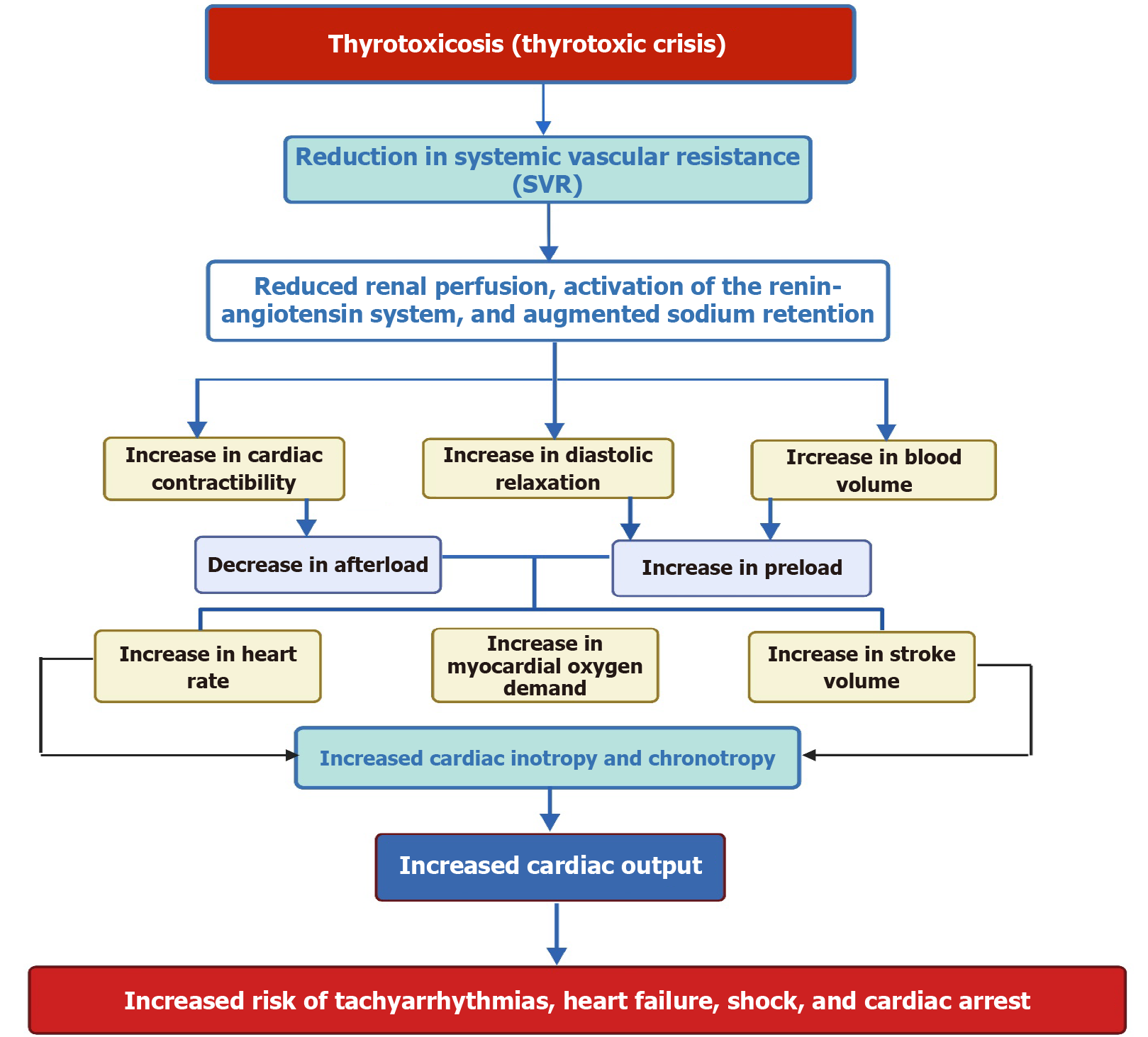

Clinically, TS can trigger or exacerbate cardiovascular disorders. From a physiological perspective, thyroid hormones (THs) closely interact with the cardiovascular system to regulate key factors such as systolic and diastolic blood pressure, heart rate, contractility, cardiac output, and systemic vascular resistance (SVR) by controlling crucial cardiac genes[17,18]. Consequently, an increase in THs levels directly affects the stability of blood flow and an increased chance of dysr

Data were extracted from PubMed and Google Scholar using English literature from inception to December 2024. Keywords included thyroid storm, thyroid crisis, hyperthyroidism, thyrotoxicosis, endocrine emergency, cardiovascular, tachyarrhythmias, circulatory collapse, high cardiac output heart failure, beta blockers, shock, circulatory support, antithyroid drugs, thyroid scoring, thyroidectomy. This narrative review summarizes the evidence and explores the clinical repercussions of TS on cardiovascular function, intricately dissecting the physiological nexus between TS and cardinal cardiovascular parameters. It also summarizes the current knowledge of pathophysiology and pharmacological and mechanical interventions, ranging from beta-blockers (BBs) to mechanical support and surgical interventions.

Thyroid storm is the most severe form of thyrotoxicosis, where organ function can deteriorate. Therefore, the diagnosis of TS primarily relies on clinical findings and a high index of suspicion during early evaluation. This is due to lack of clear laboratory signs, cutoffs in thyroid function testing, or globally recognized diagnostic criteria[5]. Clinical manifestation of TS usually comprises hyper-metabolic effects of thyroxine hormones, impacting various organs and an exaggerated feature of hyperthyroidism accompanied by manifestations of multiorgan dysfunction, depending on the rapidity of the available free no-bound fraction of the THs in circulation[5], and along with the presence of an acute precipitating factor[24].

TS is associated with worse outcomes in patients experiencing an adrenergic crisis with heightened responsiveness to endogenous catecholamines during thyrotoxic states[25]. Cardiovascular complications encompass conditions such as hypertension, myocarditis, acute myocardial infarction (AMI), tachyarrhythmia [sinus tachycardia, atrial fibrillation (AF), atrial flutter, supraventricular tachycardia (SVT), and ventricular arrhythmia], CHF, and cardiogenic shock (CS) and cardiopulmonary arrest. Thyrotoxicosis-induced cardiomyopathy is a rare occurrence, affecting less than 1% of instances[26]. It results in significant impairment of the ventricles' function. However, timely and suitable therapy for thyroid dysfunction could reverse this condition[27].

The diagnosis of thyrotoxicosis relies on elevated free Triiodothyronine (fT3) and free thyroxine (fT4), along with extremely low or undetectable thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) levels[28]. Conventional thyroid function tests are unable to differentiate between uncomplicated hyperthyroidism and TS, and the intensity of TH elevation is not a reliable indicator for diagnosing TS[29]. TS diagnosis relies on multiple factors, often necessitating superimposed events[30]. Nevertheless, many TS cases may not exhibit any obvious triggering factor[4,31].

Moreover, TS is identified by at least one central nervous system manifestation and one or more accompanying symptoms, such as thermoregulatory dysfunction, cardiovascular disorders (sinus tachycardia, AF, CHF), and gastrointestinal/hepatic dysfunction, along with a history of precipitating factors[32]. Alternatively, a combination of at least three features, like fever, CHF, tachycardia, or gastrointestinal/hepatic symptoms, can indicate TS[33]. The Burch–Wartofsky point scale (BWS), a quantitative diagnostic tool, confirms TS with a score surpassing 45 points, although these scoring systems primarily offer guidelines[32]. TS diagnosis is established by diverse systemic clinical findings[34]. BWS assesses various manifestations across major body systems, with a score of 45 or higher confirming TS, suggesting impending TS, and a score above 25 indicative of a pending storm[34]. Of note, there are few well-known scoring tools for diagnosis of TS (Burch-Wartofsky Point Scale, Japanese Thyroid Association Criteria and Akamizu Criteria). However, patients with subtle or atypical presentations may not be captured by these criteria. Elendu et al[35], have explored the shortcomings of these scoring tools in a comparative review and recommended more work to have a standardized criteria with higher diagnostic reliability and accuracy.

The progression from uncomplicated thyrotoxicosis to a state of thyrotoxic crisis or TS necessitates the presence of an additional provoking factor in some cases. Any underlying etiology of hyperthyroidism has the potential to evolve into a thyrotoxic crisis. Various precipitating factors exist, capable of instigating TS in individuals with undiagnosed thyrotoxicosis; some of these factors may initiate thyroid dysfunction, while others worsen pre-existing conditions, especially in patients with Graves’ disease[33]. Common precipitants include poor adherence to anti-thyroid medications, surgical procedures (both thyroid-related and unrelated), physical trauma, labor and delivery, molar pregnancy, acute physiological stress, certain medications, and excessive iodine exposure[4,5,33,36-38]. Moreover, infections can significantly worsen thyrotoxicosis in individuals with thyroid storm, particularly when left untreated or undiagnosed. Acute medical illnesses such as AMI, stroke, diabetic ketoacidosis, or hypoglycemia are also recognized as potential triggers for TS[39-45]. Because 99% of thyroid hormones are bound, stressors may decrease the hormone-binding capacity, which can result in an abrupt increase in the concentration of the free hormones, leading to TS[5,46]. Even minor trauma, such as fine-needle aspiration, can trigger thyroid storm in individuals with otherwise stable thyroid conditions[47]. Notably, around 25%-43% of individuals with TS do not have any recognized provoking factor[24,34].

Several case reports highlight diverse triggers for TS. Chen et al[48] discussed a 46-year-old female with neck abrasions from a fall, diagnosed with TS, which was further complicated by refractory CHF failure. Conte et al[49] documented a case of strangulation-induced TS in a patient without a thyroid disease history. Shrum et al[50] documented TS and cardiac arrest following a hanging suicide attempt. Kalpakam et al[51] identified bedside tracheostomy as a potential TS trigger, and Mathai and colleagues reported TS triggered by injecting heroin into the neck[52].

Common precipitating factors for TS include medications[39,53,54]. Drug-induced TS involves amiodarone, a class III antiarrhythmic drug used in 14%-18% of patients for tachyarrhythmia[55-57]. Amiodarone can lead to amiodarone-induced thyrotoxicosis (AIT), occurring in up to 10% of patients, with risk emerging after 18 months to 3 years and even after withdrawal due to prolonged tissue presence[58]. There are two recognized forms of AIT, with type 1 typically occurring in patients who already have existing thyroid abnormalities[59]. A study by Kinoshita et al[39] documented a case involving a patient with diabetes mellitus who experienced Takotsubo cardiomyopathy (TCM) due to a TS. In this case, the possible trigger was empagliflozin, a medication called sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitor (SGLT 2). It is worth noting that SGLT 2 inhibitors, like empagliflozin, are generally not known to be associated with TCM or TS. However, in this case, the patient had a history of thyroid disease, and the administration of the SGLT 2 inhibitor seemed to have caused the occurrence of thyroid storm.

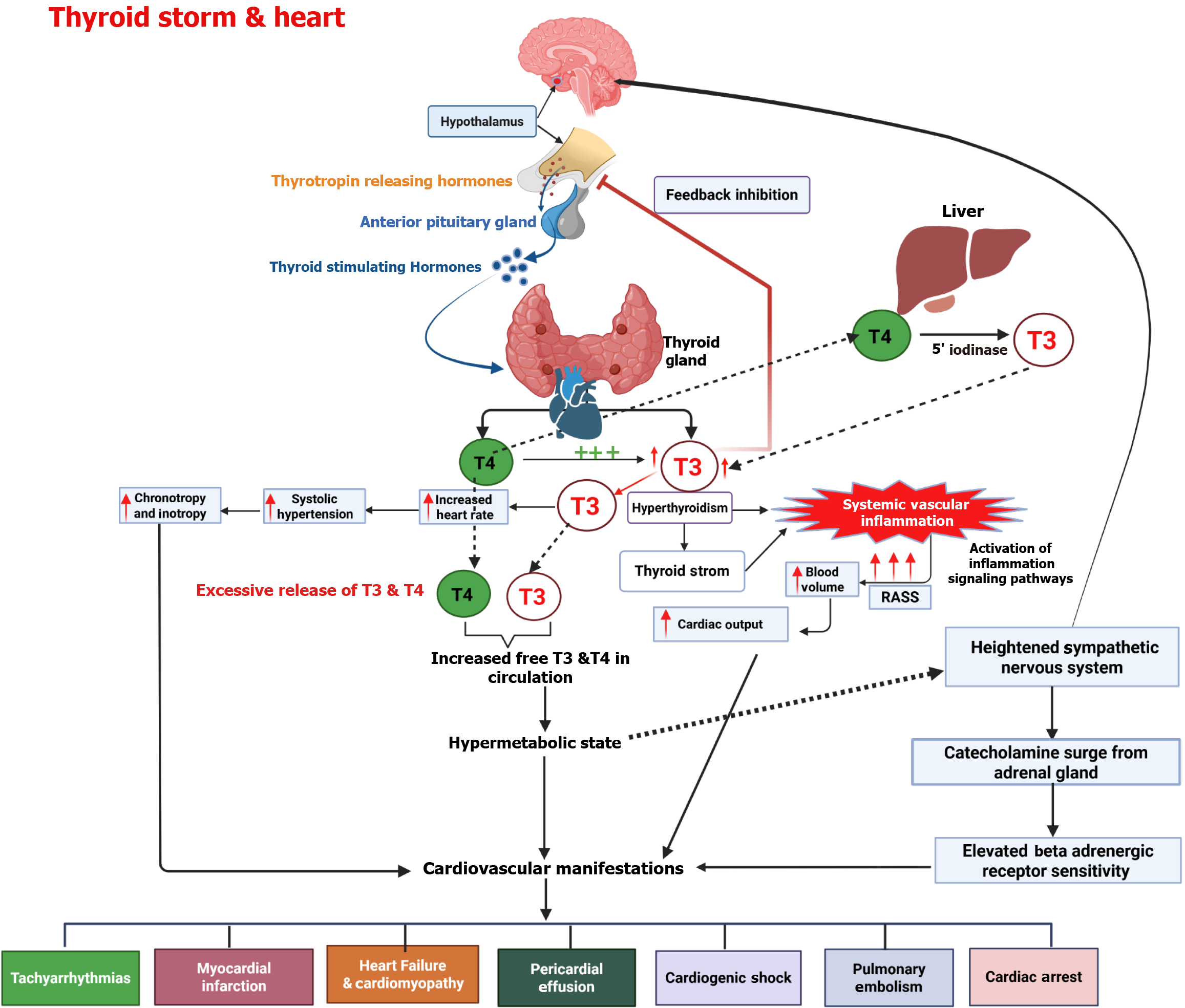

To understand the underlying causes and reasons behind the treatment methods for TS, it is crucial to have a deep understanding of the physiological processes that are involved in regulating thyroid hormones. The thyroid gland (TG) plays a role in maintaining growth, development, and metabolic function by producing two essential hormones, namely, 3,5,3',5' tetraiodothyronine thyroxine (T4) and 3,5,3′ triiodothyronine (T3). Both hormones exert their effects by interacting with TH receptors in target tissues, though T3 is regarded as the more biologically active form (Figure 1). TRHs exhibit a stronger affinity for T3 than for T4[60]. Therefore, Therefore, T4 must be converted into T3 to exert its full biological activity through receptor interaction. The thyroid gland produces less than 20% of circulating T3. Most of it is generated outside the thyroid through deiodination, primarily in the liver. THs bind to plasma proteins during circulation with thyroxine-binding globulin, a transporter protein that has a higher affinity for T4 than T3[61].

The cellular mechanism for the action of THs involves T3 binding to high-affinity nuclear receptors found on the cell surface. This is followed by the attachment of the T3-nuclear receptor complex to a DNA sequence known as the thyroid hormone response element located in regulatory regions of the genes. This process allows T3 to modulate gene transcription and protein synthesis. The interaction between hormones and receptors can have stimulating or suppressing effects directly. While T4 could also bind to these receptors, its affinity is lower than T3[62].

Moreover, although T4 can bind to nuclear receptors, it does not impact gene transcription[15]. Therefore, most of the effects associated with THs are attributed to T3 precisely[16]. 5' deiodinases control the conversion of T4 to T3 in the peripheral tissues. Certain medications, like Thionamide and propylthiouracil (PTU), can inhibit the activity of deiodinase D1. Moreover, glucocorticoids and BBs have been found to hinder the conversion of T4 to T3 in tissues, affecting levels of THs[62,63].

The pathophysiology of TS is still not fully understood, and multiple theories have been proposed to explain the underlying factors. The most common mechanism for TS is triggered by the acute release of heightened amounts of T4 or T3 from the thyroid gland. This sudden increase in hormone levels is often observed after treatments like radioiodine therapy, thyroidectomy, and discontinuation of medications or exposure to iodinated contrast agents. The process is further amplified by therapies that rapidly lower T4 or T3 Levels, such as dialysis or plasmapheresis. Another factor contributing to TS is illnesses that reduce the binding affinity of T4 and T3 to proteins in the bloodstream. This reduction in protein synthesis or the presence of inhibitors leads to a decrease in T4 and T3 Levels and an increase in concentrations of these hormones, contributing to TS[64].

Additionally, the symptoms closely resemble those seen with catecholamines surge due to sympathetic nervous system stimulation. This theory is supported by the sudden relief in symptoms observed when administering BBs. In situations involving hypoxemia, ketoacidosis, and infection, the cellular responses to THs are augmented, leading to uncoupling of the phosphorylation, excess level of ATP generation, increased substrate utilization, greater oxygen consumption, thermogenesis, and a rise in body temperature. Together, these factors contribute to the symptoms observed during TS, such as profuse perspiration and vasodilation[62,65].

Understanding these dynamics provides a rationale for using different types of drugs in treating TS. The lack of definitive understanding emphasizes the complexity of TS, necessitating the importance of continued research to improve treatment approaches and achieve better outcomes.

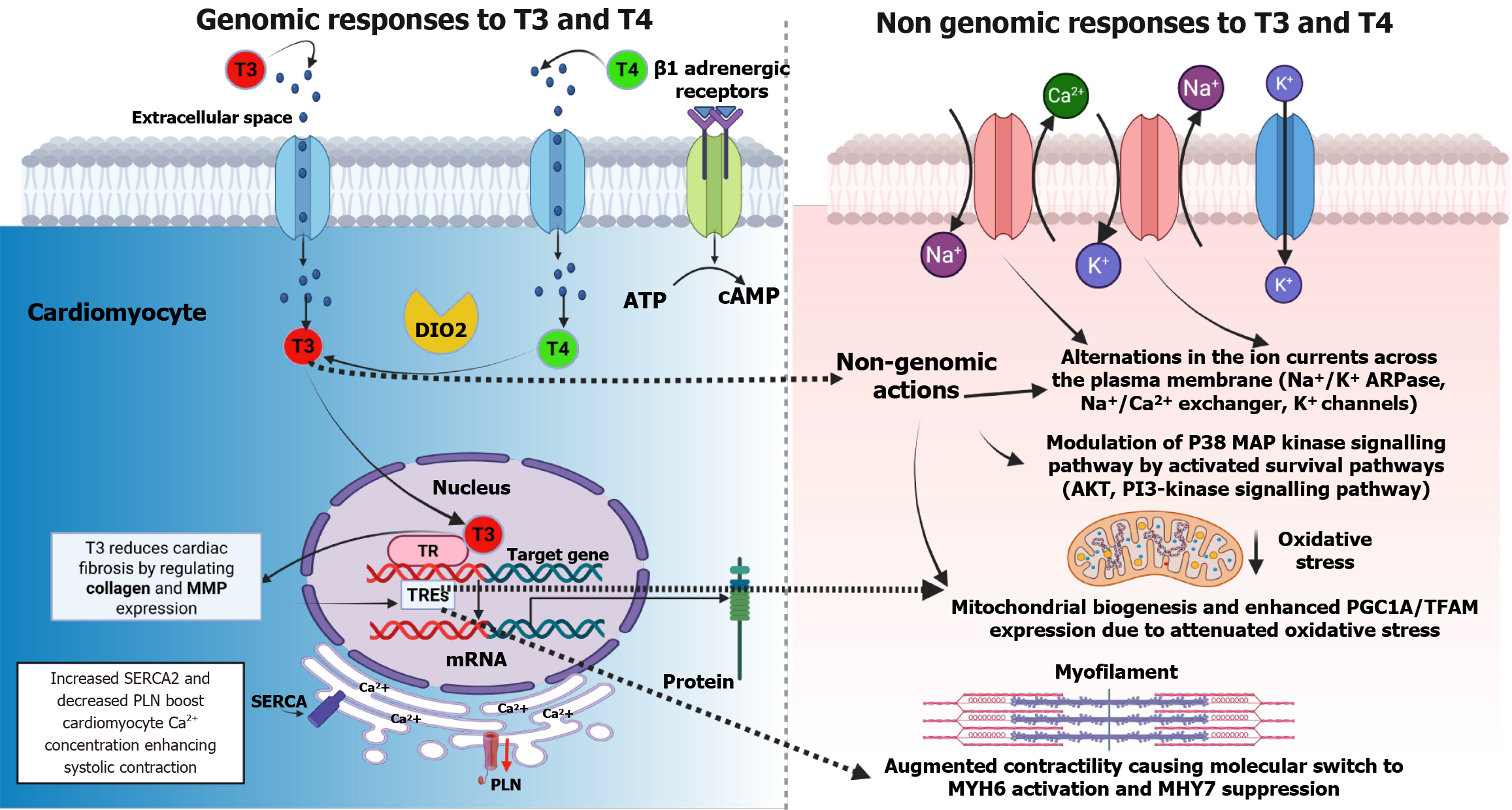

Thyroid hormones have a significant and broad-ranging effect on the cardiovascular system. The presence of THRs in the heart and endothelium means that changes in TH levels can impair cardiac function[61]. THs directly affect the heart by influencing activities within cardiomyocytes through nuclear receptors, which influence gene expression. Additionally, THs affect ion channels within cardiomyocytes. Moreover, THs also affect peripheral circulation and cardiovascular hemodynamics[66,67].

In the cardiomyocytes, the binding of T3 to nuclear THRs regulates gene transcription by interacting with thyroid hormone response elements in target genes. THs are essential for regulating genes in cardiomyocytes[68,69]. Thyroid hormone activity regulates myocardial contractility and the systolic function of cardiomyocytes by activating genes responsible for transporting sodium/potassium transporting ATPases, myosin heavy chain, and sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase 2 while negatively regulating myosin heavy chain and phospholamban. These genes control muscle contractions and calcium levels, directly affecting myocardial contractility and relaxation. Furthermore, THs increase SERCA2 Levels while reducing PLN (SERCA2 inhibitor) levels, which leads to the relaxation of ventricles through increased calcium absorption during diastole[70-74]. Additionally, THs directly enhance contractility by positively influencing the expression of genes related to β1 adrenergic receptors[75].

In addition, THs influence the functioning of the cardiovascular system through both genomic (slow-acting) and non-genomic (fast-acting) mechanisms, impacting the regulation of the autonomic nervous system as well as the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system[76] (Figure 2). They affect components of the adrenergic receptor complex and ion channels, leading to tachycardia and an increased likelihood of developing AF in hyperthyroid conditions[4]. The non-genomic effects extend to the cell membrane, where THs stimulate ion channels, affect mitochondria, and activate signaling pathways in both cardiomyocytes and vascular smooth muscle cells[53]. Elevated T3 Levels enhance the expression of genes that support cardiac function while downregulating those that have negative effects. This includes upregulation of alpha-myosin heavy chain, sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase, and beta1-adrenergic receptors, all of which contribute to improved myocardial performance.

One important pathway that is stimulated by THs is the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/serine/threonine-protein kinase signaling pathway, which contributes to the production of nitric oxide and is involved in reducing SVR, which causes smooth muscle relaxation[77,78]. Additionally, THs impact mitochondrial bioenergetics and alter cardiac mitochondrial function[79,80]. These non-genomic activities trigger vasodilation, decreasing resistance and increased calcium reuptake, ultimately improving cardiac output[81] (Figure 2).

The vasodilation triggered by THs activates the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and enhances sodium absorption. Additionally, T3 increases red cell mass, leading to elevated blood volume and preload[19]. Consequently, these physiological changes can significantly increase cardiac output by as much as 50% to 300% in individuals with hyperthyroidism. Additionally, hypertension may develop due to the vascular system’s limited capacity to handle the increased stroke volume, largely driven by a marked reduction in SVR, which can decrease by up to 70%[77].

Excessive levels of THs have complex effects on the metabolism of the cardiovascular system, specifically in the functioning of cardiac electrical conduction[54]. TS often manifests with arrhythmias, with sinus tachycardia being a prominent rhythm and a defining characteristic of patients[77,82]. Notably, a heart rate higher than 150 beats per minute has been associated with increased mortality in thyrotoxicosis[83]. In about 75% of cases, a thyrotoxic crisis causes a heart rate exceeding 130 bpm[5]. Among the arrhythmia seen in TS, the most common is AF, occurring in around 15% of cases and typically manifests as a persistent rather than paroxysmal form[84,85].

The underlying mechanism involves a pathological acceleration of the diastolic depolarization of the sinoatrial node due to action potential caused by the hyperthyroid state[86]. Overall, THs affect the cardiac conduction system by altering electrical signals, which involves shortening action potential and prolonging the atrioventricular cells' refractory period, ultimately leading to AF[77]. Furthermore, physiologically evident sympathetic activity and heightened THs levels may induce a cascade of chronotropic and inotropic alterations, contributing to tachyarrhythmia and myocardial ischemia. THs enhance the sensitivity and responsiveness of beta-adrenergic and muscarinic receptors to catecholamines, amplifying myocardial excitability. Electrocardiogram (ECG) manifestations, including atrial flutter, AF, ventricular tachycardia (VT), and multifocal tachycardia, have been observed in individuals with TS[82].

Animal studies have revealed that heightened THs elevates the expression of atrial ion channel messenger RNA, resulting in approximately two increases in potassium receptors[87]. This, in turn, augments intracellular potassium intake, reducing the atrial refractory period. Another contributing mechanism is the upregulation of adrenergic stimulation associated with the hyperthyroid state, promoting and stimulating the occurrence of atrial premature beats[88]. These premature beats, in turn, trigger acute episodes of AF within a dilated and remodeled atrial substrate, influenced by volume overload and stimulation from the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone (RAA) axis[88].

TS substantially influences the cardiovascular system, particularly in older adults who typically have comorbidities[82]. This can lead to cardiovascular events such as acute ischemia and CHF occurring more frequently. According to a study conducted by Bourcier et al[13] over 18 years using criteria for TS, 92 cases showed complications such as CHF (72%), cardiac arrest (15%), SVT (60%), and ventricular fibrillation (VF) in 13% of cases.

Atrial fibrillation: AF has been reported as the most common and prevalent dysrhythmia in TS (30%-40%)[89]. A study from Japan showed that almost half of TS patients who died had experienced AF[3]. The study conducted by Waqar and colleagues reported that AF accounted for the majority of cases (46%), while atrial flutter, VT, and SVT represented 7%, 5%, and 1.5%, respectively[82]. Moreover, a clinically significant correlation between levels of T4 and an increased incidence of AF has also been established[85]. The heightened susceptibility to AF in TS is due to myocytes that become more sensitive to THs. This sensitivity is caused by an increased expression of beta-adrenoreceptor genes in cardiac cells triggered by T3 Levels[61,77]. The rapid onset of AF in TS leads to hemodynamic collapse, lacking the usual benefits of atrial kick, atrioventricular synchrony, and heart rate control[89]. Consequently, the sudden appearance of AF acts as a triggering factor for decompensated heart failure in TS[90].

The most observed abnormalities on ECG include sinus tachycardia and a significant PR interval shortening[91]. Furthermore, a significant percentage of patients (up to 15%) exhibit altered intraventricular changes in conduction, primarily characterized by a right bundle branch block. Figure 3 illustrates a schematic flow depicting the cardiac and hemodynamic consequences of TS.

Few cases of sudden cardiac death (SCD) caused by TS have been documented in scientific literature[92-95]. The risk of mortality associated with cardiac arrest increases substantially within a brief period in individuals with TS, especially when accompanied by concurrent coronary artery disease[96]; in a documented case by Jao et al[97], TS manifested six months after discontinuing ATD, resulting in VT that progressed to VF.

The circulatory collapse during TS can be attributed to factors such as the use of BBs and calcium channel blockers (CCBs), persistent arrhythmias, decompensated CHF, CS, or severe coronary spasm[98]. Research has shown a link between levels of fT4 hormone and an increased risk of SCD, even in patients with normal thyroid function. The risk ratio for this connection is 1.87 for every 1 ng/dL increase in T4. As a result, it is recommended that individuals with levels of fT4 be monitored[98].

J-point elevation on ECG in TS: J waves, characterized by deflections occurring after or partially within the QRS com

The THs substantially influence the heart muscle by regulating the sympathetic nervous system[101]. The cardiac tissue contains β1 and β2 adrenergic receptor subtypes, and thyroid hormone influences these receptors, which affect the J point and ST segment observed on an ECG. Thyrotoxicosis increases the responsiveness of the sympathoadrenal system, leading to an increase in the number of β-adrenergic receptors, stimulatory guanine nucleotide regulatory proteins, and Gs proteins[102]. Ultimately, this results in a reduction of the J point[93].

In patients diagnosed with TS, BBs should be used cautiously if early repolarization is observed on the ECG because it can pose a risk. BBs may enhance J-point and ST-segment elevation, thereby increasing the voltage gradient across the myocardium and raising the risk of arrhythmias (arrhythmogenicity)[84]. Ueno et al[93] reported on a case of a 69-year-old man with TS who received landiolol (a short-acting BB). Despite efforts to restore average cardiac rhythm, the patient developed AF, followed by VF, ultimately leading to MOF and death.

Karashima et al[102] reported a 45-year-old man with VF and dynamic J point elevation in various baseline ECG leads. The diagnosis indicated the possibility of repolarization syndrome, which was compounded by thyrotoxicosis resulting from thyroiditis. They also found a correlation between the amplitude of J waves with serum triiodothyronine levels and a decline in this pattern during the remission of silent thyroiditis. Therefore, in patients with thyrotoxicosis or TS, close monitoring of J-wave amplitude in ECG leads is warranted due to its potential association with life-threatening arrhythmia, highlighting the clinical significance of this ECG pattern.

Thyrotoxicosis may lead to AMI[44,103]. Available evidence suggests a significant correlation between thyrotoxicosis and an increased risk of a prothrombotic state[104,105]. Long-term studies reveal elevated mortality rates from cardiovascular diseases in individuals with a history of overt hyperthyroidism[106]. Additionally, there is a 2.6-fold risk of coronary events associated with elevated fT3 concentration[107,108]. While it is uncommon for thyrotoxicosis to cause AMI in the absence of pre-existing CAD, the combination, especially when accompanied by TS, can pose significant challenges and risks. Timely diagnosis and appropriate treatment can provide a cure for both AMI and TS[106].

The exact cause of ischemia and AMI in patients with TS remains uncertain. It could be due to in situ thrombosis, a direct metabolic effect of THs on the myocardium, or other factors like SVT or AF[66]. Additionally, it has been suggested that coronary vasospasm may play a role in the development of AMI. Several studies have reported the incidence of severe spasms in the coronary arteries leading to AMI in young individuals with thyrotoxicosis, even without the presence of traditional risk factors for cardiovascular disease[66,109-111].

Most cases of TS include myocardial injury with or without accompanying alternations in the ECG. This damage is characterized by a concentration of cardiac troponin T equal to or above 0.03 ng/mL or a high sensitivity troponin T concentration equal to or exceeding 10 ng/L for women and 15 ng/L for men[112].

Patients with thyrotoxicosis, regardless of the presence of atherosclerosis, may experience either type I or II AMI[113]. The clinical relevance of troponin levels in thyroid TS remains unclear in many studies, particularly in cases where coronary angiography has not been performed. Challenges such as MOF and instability often limit the feasibility of proper treatment of AMI. In a small case series involving five individuals, TS was mistakenly diagnosed as AMI or CHF in several instances, leading to delays in appropriate management and suboptimal treatment outcomes[86].

Variables except for atherosclerosis contributing to myocardial injury involve an imbalance between the supply and demand of oxygen. This can arise from factors such as tachyarrhythmias or coronary spasms, ultimately leading to type 2 AMI[114]. Studies have found that elevated thyroxine levels have been linked to coronary spasm[115,116]. A case study conducted by Omar et al[94], reported a case involving a 40-year-old male who suffered an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest followed by an AMI. Subsequent coronary angiography identified a spasm in the right coronary artery. The treatment involved intracoronary administration, CCBs, BBs, and intravenous fluids. The underlying mechanisms of thyroxine-induced spasm may include increased cellular calcium content, heightened sensitivity of adrenergic receptors, elevated receptor numbers, increased sympathetic activity, hyperreactivity of vascular smooth muscles, and abnormalities in coronary vasomotor tone[93,114,116-118].

In another case reported by Zheng et al[116], a young man with AMI and toxic thyroiditis had patent coronary vessels. The authors attributed this to thyrotoxicosis-induced spasm, but it lacked documented evidence of TS-like clinical manifestations. The same authors reviewed 21 cases of AMI- linked thyrotoxicosis and found that 13 of them had normal coronary arteries[116,119]. Additionally, three cases had clear evidence of coronary vasospasm.

The proper functioning of the cardiovascular system is intricately linked to the thyroid status, which is directly influenced by T3 Levels in various components, including cardiomyocytes[120]. The correlation between CHF and overt hyperthyroidism varies, with data showing that approximately 2% to 7% of patients with CHF concurrently manifest overt hyperthyroidism, whereas 15% to 40% of patients with overt hyperthyroidism subsequently experience CHF[121-124].

TS can present as an initial manifestation of CHF and is a significant contributor to mortality[27]. The pathophysiology of CHF connected to TS is frequently manifested with high-output HF. Excess THs trigger activation of the RAA axis, leading to fluid and salt retention[27,125,126], and has the potential to progress to dilated cardiomyopathy and dys

THs stimulate erythropoietin production, increase preload, decrease afterload, increase blood volume by 25%, and augment cardiac output by 300%[90]. TS can cause HF without any existing cardiovascular illness. Studies conducted on mouse models have demonstrated that elevated T3 hormones are associated with changes in the heart, such as hypertrophy, fibrotic remodeling, cavity dilation, ventricular wall thinning, and increased cardiomyocyte apoptosis[127,128].

Dyspneic patients with brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) levels over 100 pg/mL or NT-proBNP levels above 400 pg/mL are at a higher risk of CHF[129]. A recently published review reported 56 incidences of TS, which were associated with high BNP levels. A study by Arai et al[33] reported eight TS patients with initial BNP levels of more than 700 pg/mL, four of which required intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) support. One patient required IABP, Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation (ECMO), and Continuous Renal Replacement Therapy (CRRT).

The treatment of HF associated with TS involves individualized approaches. Therapy is tailored for each patient and is often combined with HF treatment based on symptoms and ejection fraction considerations. Beta-blockers are frequently used to control adrenergic activity, and thioamides like methimazole and propylthiouracil are used as ATD. Radioactive iodine or steroids may also be considered[130]. Re-evaluating cardiac function during and after thyroid correction is crucial, considering the potential reversibility of TS-induced structural and functional changes. Adjustments or withdrawals of HF medications may also need reevaluation in this context[131-134].

Dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) is characterized by progressive, often non-ischemic, changes in the structure and functioning of the myocardium[135].

Dilated thyrotoxic cardiomyopathy (TCMP), an uncommon manifestation of TS, has been identified as the initial presentation of hyperthyroidism in 6% of patients, with severe left ventricular dysfunction observed in less than 1% of cases[1,90,136]. The presence of uncontrolled persistent tachycardia in hyperthyroid patients may lead to dilated cardiomyopathy in 6%-15% of cases[137]. This condition signifies the final stage of remodeling and functional changes in the left ventricle when hyperthyroidism is not promptly diagnosed or effectively treated. Elevated THs beyond the normal range intensify adrenergic activity, contributing to stress-induced cardiomyopathy. The clinical presentation of TCMP can deteriorate into overt CS, sometimes necessitating mechanical circulatory support devices. Therefore, acknowledging DCM as an uncommon yet reversible consequence of thyrotoxicosis is of significant clinical importance[82].

The development of DCM involves overexpression and release of too much thyroxine, which stimulates the sym

Small dosages of BBs (ultra-short-acting) can be given after ATDs' administration, as ATDs have a delayed onset of action. However, these BBs should be used after achieving acceptable blood pressure[90,139].

Despite being a recognized complication of thyroid disorders, pericardial effusion is uncommon in cases of thyrotoxicosis[140,141]. In contrast, hypothyroidism shows a higher association with pericardial effusion, affecting approximately 5% to 30% of individuals with the condition[142]. The absence of data that establishes a connection between pericardial effusion and thyrotoxicosis does not imply that both conditions do not coexist. Instead, it highlights the significance of main

Cardiovascular complications in TS may present with a delayed onset and are often accompanied by inflammation in the pericardium and inflammatory fluid accumulation. The suspected underlying mechanism involves an interaction between antibodies against thyroid hormones and the pericardium[143]. Additionally, analysis of the fluid accumulated around the heart in TS cases shows markers suggestive of inflammation, which may aid in diagnosis.

Interestingly, there are similarities between the pathophysiology of pericardial effusion associated with thyrotoxicosis and pretibial myxedema[144]. Both involve serous effusion due to albumin leakage and impaired clearance of proteins from interstitial fluids. Sometimes, in cases of TS, the fluid around the heart may have a mix of serum and blood[145]. While it is infrequent, there have been some reports in the literature of TS and pericardial effusion occurring together[146-151]. Pericardial effusion and pericarditis are not common in thyroid-related diseases. They might resolve on their own as hyperthyroidism resolves, potentially negating the need for specific treatments. A study by Bui et al[152] reported seven patients with pericardial effusions out of 12 patients with thyrotoxicosis caused by Grave's disease.

TS-induced CS is a rare complication associated with poor prognosis; however, very little data exists on its incidences and outcomes[153]. CS could be associated with a four-fold increased likelihood of mortality[3]. Several preluding factors can contribute to the development of thyrotoxicosis-induced CS. These include existing CHF, AF, valvular heart disease, coagulation disorders, drug abuse, fluid and electrolyte imbalances, as well as hepatic, renal, or pulmonary complications[147]. An early detection and involvement of a multidisciplinary team involving the cardiologist, endocrinologist, pulmonologist, and hospitalist may help the patient's acute management and survival with a potential recovery from the acute phase of the illness[126].

The precise pathophysiology of TS-induced CS remains unclear and complicated. It entails a multifactorial phe

The management of TS-induced CS involves assessing the cardiac function, preferably through an echocardiogram, before starting the patient on a non-cardio-selective beta-blocker in patients with hemodynamic instability. Also worth noting is the fact that although the traditional treatment of thyrotoxicosis includes non-selective beta-blockers, their use in patients presenting with TS-induced shock may be destructive and worsen their condition due to reduced stroke volume because of their negative inotropic and chronotropic effects, especially in situations where controlling the heart rate is fundamental to maintaining cardiac output[154-156].

Therefore, to prevent further worsening of clinical presentation, it is imperative to discontinue BBs and CCBs that may trigger CS. Mohananey et al[157] reported that about 51.8% of patients with AF also suffered from CS, with a resulting mortality rate of 54.8%. A study from the USA indicated a rise in CS incidence from 0.5% in 2003 to 3% in 2011, accompanied by a decrease in mortality from 60.5% in 2003 to 20.9% in 2011[157]. Iwańczuk reported a case involving a 51-year-old female who presented with TS and acute myocardial infarction (AMI)[119]. Despite patent coronary arteries, the patient experienced catecholamine-resistant shock and required support with dobutamine, norepinephrine, dopamine, and IABP. Subsequently, she had a subtotal thyroidectomy procedure done, after one week, and ultimately made a successful recovery.

Hyperthyroidism contributes to hypertension by stimulating the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and accelerating the progression of atherosclerosis[66]. On the other hand, the T3 hormone promotes vasodilation to enhance thermogenesis, resulting in reduced SVR and low diastolic pressure. Arterial stiffness, as determined by the ratio of elastin to collagen, is a surrogate indicator for atherosclerosis and can be influenced by various cardiovascular risk factors, including hyperthyroidism[158].

The occurrence of PH in hyperthyroidism is relatively common, with estimates ranging from 36% to 65%[101,159]. It's worth noting that most cases are mild or show no symptoms. Similar to the causes of PH, this complication has a prognosis mainly due to the failure of the right ventricle[17]. Proposed mechanisms responsible for PH in hyper

Approximately 10%-40% of individuals with hyperthyroidism experience embolism[160]. Several observational studies have found a connection between thyrotoxicosis/TS and PE, with a two-fold increased risk compared to individuals without thyroid dysfunction[160-162]. Importantly, it is worth noting that overt hyperthyroidism is associated with other complications, like deep vein thrombosis and cerebral venous thrombosis[163,164].

An elevated thyroid function affects Virchow's triad by shortening activated thromboplastin time, increasing fibrinogen and factor VIII levels, Von Willebrand factor, tissue plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1), and decreasing plasma capacity. This ultimately results in a state of hypercoagulability[164,165]. Additionally, the hemodynamic changes associated with hyperthyroidism, such as increased blood flow, can damage the endothelium, which may further exaggerate thromboembolic events[166].

While some studies have not definitively shown a connection between overt hyperthyroidism and the risk of embolism, especially in elderly or hospitalized populations[167,168], the overall weight of the evidence suggests a significant association. Therefore, many experts recommend testing thyroid function in patients with embolism and advocate for normalizing thyroid function as part of a comprehensive approach to preventing recurrent thrombotic events[162,169,170].

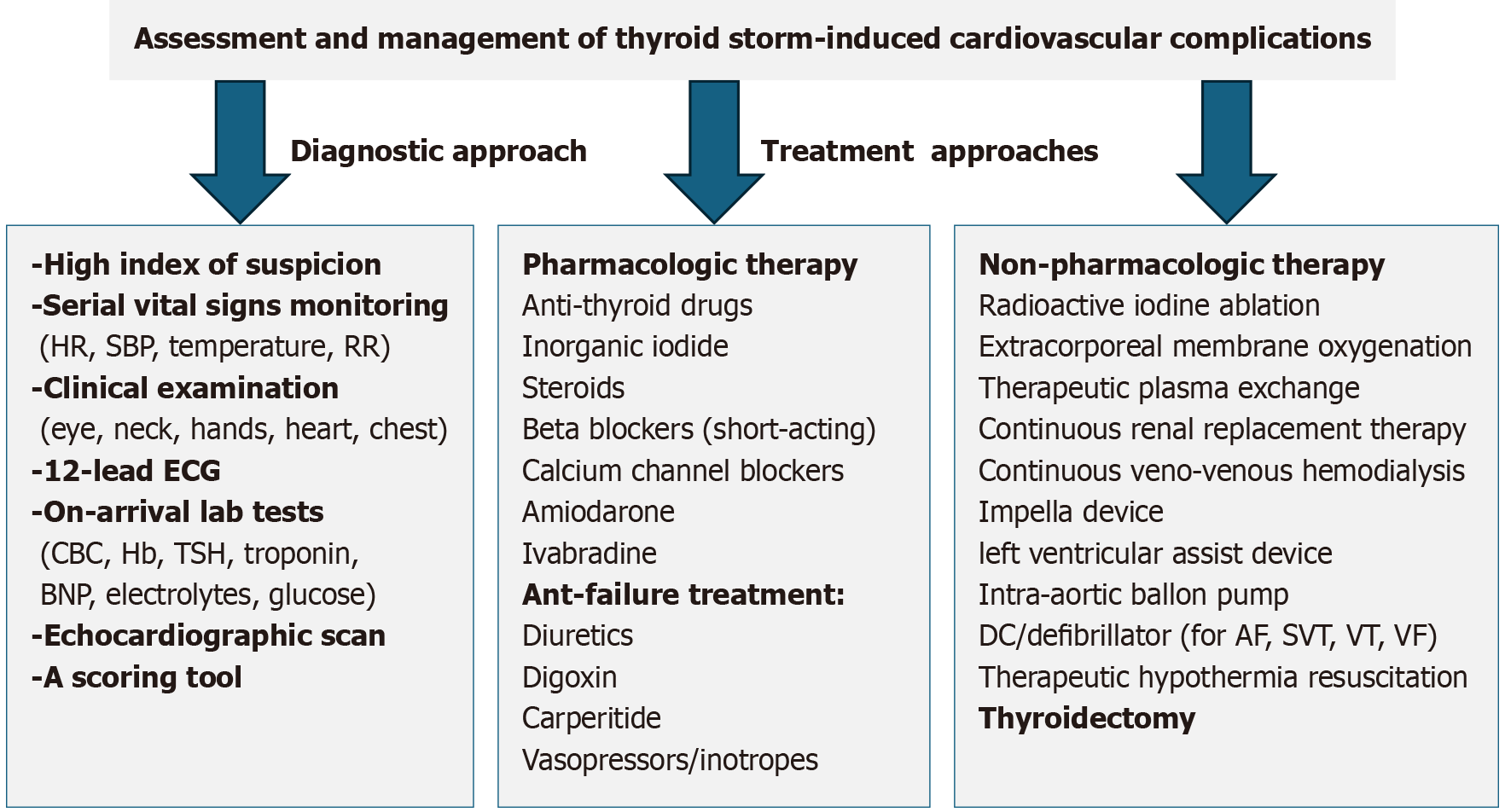

The treatment strategies for TS involve a comprehensive approach, combining pharmacological and supportive non-pharmacological measures (Figure 4). Timely attention, accurate evaluation, and preventing misdiagnosis of thyroid storm are crucial, as they impact multiple organs. Therefore, early intervention significantly influences the outcome, and effective management of life-threatening symptoms affecting multiple organs is imperative. In General, the Japanese treatment guidelines for TS focus on suppressing excessive thyroid hormone synthesis and release. Additionally, they also emphasize the management of systemic symptoms such as fever, dehydration, and shock, along with organ-specific complications involving the cardiovascular, neurological, and hepato-gastrointestinal systems. Identifying and addressing precipitating factors, along with implementing definitive therapy, form key components of this comprehensive treatment strategy[83].

Initial management with ATDs: The primary approach to treating thyroid storm involves using ATDs such as thionamide like PTU and imidazoles such as methimazole (MMI) and carbimazole (CBZ), to inhibit the production of new thyroid hormones. These medications work by inhibiting thyroid peroxidase, which prevents the formation of T3 and T4 from thyroglobulin[34]. While both methimazole and PTU are used, PTU is preferred over carbimazole and methimazole during a TS because it has a rapid onset of action and the ability to prevent the conversion of T4 to T3 by peripheral deiodinase[34].

Matsubara et al[54] documented an instance of agranulocytosis resulting from the administration of MMI, necessitating thyroidectomy as the ultimate therapeutic intervention. In a separate case, Voll et al[53] detailed the utilization of VA-ECMO, Lugol's iodine, and thyroidectomy in the treatment of TS in a patient who developed neutropenia due to CBZ.

Therapy with inorganic iodine: Organic iodine plays a role in decreasing the synthesis of new thyroid hormones, primarily through the inhibition of the organic binding of iodide to thyroglobulin, known as the Wolff-Chaikoff effect[171,172]. This effect is temporary, lasting approximately 50 hours[173]. To prevent iodine from serving as a substrate for new thyroid hormone production and exacerbating hyperthyroidism, it should be given at least one hour after thionamide administration. Thionamides must be continued during iodine therapy to prevent the organification of iodine and increase thyroid hormone production[6,174].

Notably, iodine's effect on inhibiting hormone release has a quicker onset than PTU. Combining thioamides with iodine normalizes serum T4 Levels within 4-5 days[175].

Treatment with steroids: In cases of thyrotoxicosis, the normal functioning of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis is compromised, resulting in a decrease in adrenal reserve. Although the adrenal glands produce cortisol to counteract the increased metabolism of glucocorticosteroids, in hyperthyroid states, they do not respond adequately to adrenocorticotropic-stimulating hormone. Consequently, corticosteroids are administered as prophylaxis to prevent insufficiency during TS. They also help reduce the conversion of T4 to T3 at the level[83]. Following the successful early management of severe thyrotoxicosis in thyroid storm, corticosteroids should be gradually tapered and discontinued once adrenocortical recovery is confirmed through fasting serum cortisol measurement[83].

Despite the anticipated beneficial effects of corticosteroids mentioned earlier, the level of evidence remains moderate[176]. Hence, determining the type and dose of corticosteroids on an individualized basis is crucial to enhance thyroid storm outcomes.

Treatment with beta-blockers: An essential aspect of managing TS is mitigating the peripheral effects of thyroid hormone excess. BBs counteract the heightened α- and β-adrenergic stimulation observed in TS, mitigating indirect TH effects. Several studies have reported the successful use of non-cardioselective BBs (NCBBs) and cardioselective BBs in TS. The potential complications include CS, acute HF, and bradycardia. Administration routes, dosages, and treatment durations vary based on patient needs. Propranolol is preferred due to its additional benefit of inhibiting the peripheral conversion of T4 to the more metabolically active T3[126].

However, the use of BBs in TS can present a therapeutic dilemma, particularly in patients with underlying thyrotoxic cardiomyopathy or subclinical thyroid dysfunction, especially those presenting with low-output heart failure. In such cases, administration of propranolol may precipitate circulatory collapse[177]. This phenomenon may be likely due to the non-cardioselective beta-blockers’ abrupt inhibition of the compensatory hyperadrenergic response triggered by thyrotoxicosis, which can lead to significant hemodynamic instability[177].

Approximately 25.8% of reported cases involving circulatory collapse in TS were potentially linked to BB use, with some also receiving concurrent BBs and CCB therapy[177]. Notably, propranolol, utilized in 46% of these cases, nece

Voll et al[53] observed the limited efficacy of dobutamine in reversing circulatory collapse induced by high-dose propranolol. Misumi et al[181] documented the first case of landiolol-induced cardiac arrest in TS, while Lim et al[177] reported a patient experiencing CS following esmolol administration for tachycardia. Chao et al[183] reported that decompensated heart failure can significantly diminish BB tolerability. However, Yamashita et al[180] successfully employed landiolol in a patient with TS and heart failure complicated by atrial fibrillation, suggesting its potential utility in specific scenarios.

CCBs and ivabradine: A few authors have reported using CCBs to treat TS. Subahi and colleagues reported the administration of intravenous diltiazem, a CCB with a negative inotropic effect, used to alleviate thyro-cardiac storm, led to adverse drug reactions, ultimately leading to CS[137] necessitating the use of inotropic and vasopressor support. In thyrotoxic patients experiencing low-output heart failure, THs that mediate adrenergic surges play a permissive role in maintaining cardiac output. The use of negative inotropic medications in such patients may disrupt this compensatory mechanism, leading to a severe reduction in ejection fraction and hemodynamic instability[137,184].

Another therapeutic agent, Ivabradine, which blocks the hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated channel, acts specifically and selectively on the sinoatrial node by inhibiting the pacemaker current (If), leading to heart rate reduction without compromising cardiac contractility. Frenkel et al[185] documented a case of a 37-year-old individual presented with thyrotoxicosis and CHF. Despite attempting to regulate the heart rate with high doses of propranolol, it proved ineffective. Subsequently, the initiation of Ivabradine resulted in successful heart rate reduction within 48 hours[185].

Amiodarone: Amiodarone, a potent class III antiarrhythmic drug, can be used to treat patients with TS experiencing various cardiac rhythm disturbances, including life-threatening tachyarrhythmia[186]. It affects thyroid function by inhibiting 5'-deiodinase activity, leading to decreased T3 generation from T4, increased reverse T3 production, and reduced clearance[187]. Despite its efficacy, amiodarone's high lipid affinity and tissue concentration contribute to numerous side effects, including pulmonary and hepatotoxicity, hyperthyroidism, and hypothyroidism[188]. The drug's impact on the thyroid gland is categorized into intrinsic effects from its compound properties and iodine-induced effects due to its iodine-rich structure, which can increase iodine 50-100 folds.

Amiodarone use can lead to AIT in 14%-18% of patients, with a higher prevalence in iodine-deficient regions and among men[59,186]. A daily dose between 200 and 400 mg is considered safe and effective for maintaining serum TSH levels. Nevertheless, when given intravenously, it can increase them[186].

Due to amiodarone's prolonged half-life, AIT can manifest either early in treatment or several months after discontinuation. Two main mechanisms contribute to AIT: Type 1 involves iodine-induced hyperthyroidism, while type 2 results from destructive thyroiditis caused by amiodarone's cytotoxic effects. Recent data suggest that type 2 AIT is more common, but both mechanisms may coexist in the same patient[189,190].

While amiodarone is known to induce AIT, Yamamoto et al[1] documented a case involving a patient initially diagnosed with multifocal atrial tachycardia complicated by CS. Faced with persistent refractory tachyarrhythmia, the medical team opted for IABP and continuous amiodarone infusion. Interestingly, as the patient's condition improved, subsequent blood samples from the first to the seventh day revealed a TS. Despite not following the conventional TS treatment regimen, the author asserted that amiodarone was a curative measure for TS. Due to its high iodine levels, this curative effect is attributed to amiodarone's ability to impede iodine uptake by thyroid cells[1].

Another derivative of amiodarone, Dronedarone (class III antiarrhythmic agent), lacks iodine groups and minimizes adverse effects by reducing tissue accumulation. Unlike amiodarone, Dronedarone is less lipophilic, has a shorter half-life, and undergoes extensive metabolism, showing no apparent thyroid, pulmonary, or neurological adverse effects associated with amiodarone[191,192]. Understanding these differences is vital for choosing the appropriate antiarrhythmic therapy based on individual patient characteristics and minimizing potential complications.

Anti-failure treatment in TS: Early intervention is crucial in managing TS-induced CHF. Serial echocardiography and monitoring of BNP levels are recommended. Effectively controlling AF is critical in such situations. Respiratory management strategies involve noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation or intratracheal intubation for artificial respiration if the patient's respiratory condition does not respond to oxygen administration[83,193].

Therapeutic strategies encompass medications such as digoxin, intravenous furosemide, sublingual or intravenous nitrates, and/or intravenous carperitide (human atrial natriuretic peptide) are recommended.

Dopamine is administered intravenously (5-20 μg/kg/min) when the SBP ranges from 70 to 90 mmHg. For patients in CS, dobutamine at a dose of approximately 10 μg/kg/min is recommended. Norepinephrine is administered at a dosage range of 0.03 to 0.3 μg/kg/min in cases where the patient’s hemodynamic status does not improve or when systolic blood pressure falls to 70 mmHg or below. In cases of elevated heart rate (≥ 150 bpm), short-acting beta1-selective adrenergic antagonists like landiolol or esmolol may be considered. Simultaneous use of digitalis is advised in the presence of atrial fibrillation.

The multifaceted anti-failure approach aims to alleviate symptoms, address hemodynamic imbalances, and improve overall cardiac function in hyperthyroid-induced CHF cases. Therefore, in most cases, pharmacological therapy alone cannot alleviate TS and maintain euthyroid and stable hemodynamic status, and mechanical support is required.

The therapeutic options for severe endocrine emergencies, mainly TS, have developed a robust armamentarium of mechanical and extracorporeal support systems. These support systems, including ECMO, Therapeutic plasma exchange (TPE), CRRT, IABP, and Impella, may serve as valuable tools for establishing stability and facilitating bridging therapies to definitive surgical intervention. While ECMO and TPE have been utilized together in several cases, the concurrent application of all three advanced support systems remains relatively uncommon and only a limited number involved the simultaneous use of all three support systems[149,194,195]. Existing literature surrounding their concurrent use primarily stems from individual case reports and small case series, needing more robust evidence of prospective clinical trials[177]. Despite their established efficacy in specific scenarios, these interventions have limitations. Their significant costs, potential side effects, and technical complexities necessitate the involvement of a skilled multidisciplinary team, alongside careful considerations for patient selection and timing.

Veno-arterial-ECMO: VA-ECMO is an established intervention that saves lives in cases of acute cardiopulmonary failure. Reports have documented its effectiveness in treating circulatory during TS. A series of cases with thyrotoxicosis-induced cardiovascular dysfunction reported that three out of four patients survived. All these patients experienced normalized thyroid function and improved health following supportive ECMO support for durations ranging from 19 to 114 hours[196]. White et al[197] documented the successful use of ECMO in treating thyrotoxicosis-induced cardiomyopathy in 11 out of 14 cases[55,125,198]. In severe cases, where conventional pharmacotherapy proves insufficient and often fails to restore cardiovascular function to normal following TS development, extracorporeal modalities like ECMO are implemented. Notably, in a separate analysis of 256 cases, the use of ECMO was reported in 16.3% as a primary and most used mode of mechanical support.

Eltahir et al[199] presented a case series of four patients (3 females and one male; age range 39-46) experiencing severe TS complicated by MOF and cardiac arrest. All patients received VA-ECMO support and underwent planned thyroidectomy. Notably, three individuals were treated successfully and were discharged, while one succumbed to prolonged cardiac arrest and sepsis. In life-threatening TS, VA-ECMO plays a crucial role in stabilizing patients, facilitating definitive surgical intervention, and optimizing postoperative endocrine management[199]. Simultaneously, as THs levels normalize, ECMO helps restore the euthyroid state[200]. Furthermore, several reports have indicated that using ECMO positively impacts the likelihood of favorable outcomes prior to thyroidectomy due to myocardial function stability[177]. Furthermore, when combined and used in conjunction with other extracorporeal modalities, the outcomes may be improved, leading to a more successful and effective therapy[177,200].

The integration and utilization of ECMO for managing endocrine disorders is a recent development. However, the estimates of the overall benefits in survival rate could be unreliable and misleading. Potential publication bias, inherent patient selection bias due to the critical nature of these diseases, and small sample size all add to the uncertainty in reported survival rates[177]. Additionally, the cause of mortality might not be solely associated with the use of ECMO, as underlying factors such as the severity of cardiomyopathy, shock, and other comorbidities may play a more significant role[177,196]. Furthermore, ECMO itself carries the risk of some complications, including bleeding, limb ischemia, thrombosis, and stroke[177,197]. Therefore, a cautious approach to interpreting survival rates is crucial, acknowledging both possible biases and the contribution of adverse events associated with ECMO to the overall clinical landscape.

TPE: TPE is one of the most effective extracorporeal purification methods to eliminate excessive thyroid hormones from the blood of patients with TS[26]. A rapid filtering technique effectively reduces protein-bound and free T4 and T3 Levels[177]. The American Society for Apheresis classifies, TPE as a category II treatment option for TS either as a primary therapy or in combination with other interventions, depending on individual clinical scenarios[177]. Since TPE may also remove essential components such as clotting factors and immunoglobulins, patients should receive appropriate replacement with colloids and blood products to reduce the risk of bleeding and infection[149]. An early and timely implementation of TPE therapy should be initiated in the treatment course to ensure optimal outcomes in TS[149]. However, in some cases, the process may be delayed due to more urgent complications. This delay might lead to technical difficulties, such as the requirement for Continuous Veno-Venous Hemodialysis (CVVHD) to address acute kidney injury (AKI) and metabolic acidosis[201]. TPE can also be incorporated into a broader, multimodal treatment strategy alongside interventions such as ECMO, Impella support, or continuous CRRT[177,202].

Furthermore, TPE also functions as an intermediary treatment until the patient attains stability to undergo thyroidectomy[149]. TPE reduces free and total thyroid hormones by approximately 10% to 80%. It works by multiple me

TPE is generally well-received by patients with a favorable tolerance profile. The incidence of side effects related to TPE varies, ranging from approximately 5% to 36%. Notably, the risk of mortality associated with TPE is as low as 0.05%[17]. In cases where fatalities do happen, they are usually attributed to the severity of the patient's underlying medical condition.

CRRT and continuous veno-venous hemofiltration: CRRT is a treatment method that combines hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis. It uses pump-driven circuits to provide renal support and maintain solute and fluid balance in the blood. This therapy needs proper vascular access, pumps, a permeable membrane, and various solutions to ensure fluid levels[204].

CRRT involves using substantial fluids at room temperature, such as dialysate and replacement fluids, which can cause hypothermia. Additionally, when albumin and plasma are administered intravenously during CRRT, they enhance the binding capacity of proteins to free thyroid hormones, which can influence the overall efficacy of therapy[202]. It is commonly employed in intensive care settings for patients with acute AKI, who are hemodynamically unstable, making it a preferred therapeutic option in such critical conditions. Several published case reports have provided evidence of the effectiveness of CRRT in managing thyroid TS. CRRT is favored due to its tolerability in hemodynamically unstable patients, as it allows for gradual fluid and solute exchange. Some case reports have demonstrated the combined effects of TPE and CRRT in eliminating THs[205]. Furthermore, one report observed up to an 80% improvement in T3 and T4 Levels with concurrent CRRT and standard medical therapy (without TPE), although the exact mechanisms for this improvement remain unclear[202]. These findings emphasize the advantages of integrating CRRT into the therapeutic options for managing TS, which could improve patient outcomes.

Moreover, continuous veno-venous hemofiltration (CVVH), one of the modes of CRRT, employs convective transport or clearance to remove solutes and toxins from the patient’s bloodstream. In contrast, CVVHD primarily depends on diffusion for clearance of solutes and toxins[206]. CVVH is particularly beneficial in reducing the risk of metabolic and hemodynamic complications, thereby offering a more stable and integrated treatment strategy. Parikh et al[207] and Koball et al[208] have highlighted using single-pass continuous venovenous albumin dialysis following limited response to TPE. This approach has improved thyroid hormone levels, reduced rebound thyrotoxicosis, and enhanced hormone removal.

IABP and Impella: A prior review showed 23 cases of TS treated with IABP[14]. In some cases, IABP was combined with ECMO to provide circulatory support while addressing the underlying cause of heart failure, such as TS. However, ECMO had been preferred over IABP[125].

The Impella device supports systemic circulation by drawing blood from the left ventricle and delivering it into the ascending aorta, providing a flow rate between 2.5 and 5.0 L/min. It is often favored over ECMO due to its ability to directly unload the left ventricle, thereby promoting myocardial recovery. This catheter-based device, utilized for ventricular support in CHF and CS patients, was implemented in a few cases, including a scenario where biventricular Impella (Bi-pella) usage demonstrated notable benefits[14,209].

Therapeutic hypothermia could reduce mortality rates by more than 25%[210]. It works by inducing hypothermia, which plays a role in slowing down the inflammatory cascade and inhibiting programmed cell death pathways that occur after cardiac arrest. Nowadays, therapeutic hypothermia is considered a treatment for TS-induced cardiac arrest. It helps to reduce the release of excitatory amino acids and free radicals while mitigating the intracellular effects caused by excitotoxin exposure. Additionally, therapeutic hypothermia helps decrease the brain's metabolic rate of oxygen, cerebral blood volume, and intracranial pressure. As a result, it significantly improves the balance between oxygen supply and demand[211].

Fu et al[212] presented a 24-year-old woman who experienced an arrest due to TS while being treated at the hospital. Following resuscitation, she developed hyperthermia and coma. Therapeutic hypothermia using intravascular cooling was initiated to prevent any damage. It took 72 hours to reach the target temperature of 34 °C despite episodes of fever. An ice blanket and hat were employed during this period until her condition stabilized.

Similarly, Shimoda et al[213] utilized a cooling blanket as part of their treatment approach for TS patients who also had CHF, atrial flutter, fever, hepatic failure, DIC, and elevated soluble interleukin-2 receptor (sIL-2R) levels.

Radioactive iodine ablation (RAI) is often used as a treatment for Grave's disease when thionamide therapy fails or when patients cannot tolerate ATDs, particularly if they have cardiac conditions[214]. Typically, the surgery is performed following treatment to decrease the risk of recurrence, resulting in around 80%-90% of patients experiencing hypothyroidism after undergoing RAI[202]. A recent scoping analysis has reported four cases where RAI proved successful in treating individuals with Grave’s disease who had subsequent heart failure[14]. Notably, more than one-third of those with hyperthyroidism may need RAI therapy to achieve recovery. All the abovementioned support can work until the definitive treatment (surgical) can be safely and effectively performed.

Before considering surgical intervention, it is essential to achieve a euthyroid condition, particularly for patients who indicate resistance to aggressive medical interventions[6]. This resistance is more prevalent in regions with an iodine deficit. In these cases, TS commonly occurs as a result of iodine contamination in patients with thyroid autonomy, which makes them less receptive to traditional therapies because of a large buildup of iodine inside the thyroid gland[215]. It is essential to stabilize the patient before considering urgent surgical interventions, and the surgical team should be involved early (within 12-72 hours) if the patient remains unresponsive to medical therapy[34].

Surgical options include partial or near-total thyroidectomy, which effectively and quickly resolves hyperthyroidism and reduces reliance on thionamide medication post-procedure[216]. Although thyroidectomy is quite adequate, it should be considered the last resort for treating TS as it does not provide complete protection against future relapses[53]. It is recommended that corticosteroids and BBs be continued and gradually taper during the perioperative period since this has been shown to have a significant association with lower mortality rates[217]. Nevertheless, the management of surgery during the early phase may be challenging due to the frailty of patients experiencing severe and refractory TS.

TS has potentially fatal consequences; however, the precise causes of mortality and prognostic components are ambiguous and still not fully understood. Furthermore, TS can be missed as no trigger is reported in 30% of cases[14]. Previous studies have indicated a fatality rate ranging from 10% to 30%[6,218]. These estimates may not be entirely accurate in the current scenario due to advancements in critical medicine. According to a survey conducted in Japan, the mortality rate for TS cases was found to be 10.7%, with half of the deaths directly attributed to CHF or MOF[3].

A scoping review by Elmenyar et al[14] reported that 16% of patients admitted to the hospital with thyrotoxicosis had TS. The mortality rate for thyrotoxicosis, with and without a storm, was twelve times greater for TS patients[8]. Another review article documented varying mortality rates for TS in hospitals, ranging from 10% to 75%[9]. Overall, the mortality rate was reported to be 13.5%. Furthermore, mortality rates for TS in hospitals vary, with estimates from 10% to 70%[9]. In addition, after the administration of BBs and/or CCBs, they could experience hemodynamic decompensation and circulatory collapse if blood pressure and ejection fraction status were not considered.

Of note, the utilization of CRRT was found to be significantly associated with augmented mortality rates in patients with acute renal injury and circulatory collapse[219].

The common causes of death following TS include MOF (25%), CHF (20%), and arrhythmia (8%). MOF increased the likelihood of death by ten times based on logistic regression analysis[3]. Moreover, a case report indicated a factor that could cause complications in TS along with MOF. It suggested that increased levels of sIL 2R trigger the immune response[220]. However, studies are needed to confirm this observation. Despite these findings, large-scale cohort studies on TS mortality are lacking. The available studies have limitations, such as treatment variations or small sample size.

Various clinical symptoms occur in TS, highlighting its ability to inflict widespread systemic injury affecting multiple organ systems due to the pleiotropic effects of THs in different metabolic processes. The cardiovascular system is particularly susceptible, requiring vigilance to avoid misdiagnosis of TS. The exact mechanisms leading to uncomplicated thyrotoxicosis transition to TS are not fully understood. The clinical implications of this article highlight the importance of TS in relation to heart-related complications and the need for comprehensive and well-planned studies to investigate pharmacological options for treating TS and its impact on improving our knowledge and understanding of the optimal therapeutic strategies available.

Management strategies for TS should be based on affected end organs, considering the safety and efficacy of targeted therapies, while prioritizing measures to prevent recurrence.

Timely recognition and appropriate management of TS in cardiac care settings involving a range of pharmacological, mechanical, and surgical interventions are crucial, especially for high-risk patients requiring mechanical support.

Decision-making regarding treatment should be tailored to individual patient characteristics, and Interdisciplinary collaboration is important.

Frontline physicians should be adept at recognizing not only "thyrotoxicosis" but also the specific entity of "TS", particularly in the absence of any prior history of hyperthyroidism or precipitating factors, as TS may be undiagnosed in many patients.

| 1. | Yamamoto H, Monno S, Ohta-Ogo K, Ishibashi-Ueda H, Hashimoto T. Delayed diagnosis of dilated thyrotoxic cardiomyopathy with coexistent multifocal atrial tachycardia: a case report. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2021;21:124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lahey FH. Apathetic Thyroidism. Ann Surg. 1931;93:1026-1030. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Akamizu T, Satoh T, Isozaki O, Suzuki A, Wakino S, Iburi T, Tsuboi K, Monden T, Kouki T, Otani H, Teramukai S, Uehara R, Nakamura Y, Nagai M, Mori M; Japan Thyroid Association. Diagnostic criteria, clinical features, and incidence of thyroid storm based on nationwide surveys. Thyroid. 2012;22:661-679. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 245] [Cited by in RCA: 251] [Article Influence: 17.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | De Almeida R, McCalmon S, Cabandugama PK. Clinical Review and Update on the Management of Thyroid Storm. Mo Med. 2022;119:366-371. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Chiha M, Samarasinghe S, Kabaker AS. Thyroid storm: an updated review. J Intensive Care Med. 2015;30:131-140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Nayak B, Burman K. Thyrotoxicosis and thyroid storm. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2006;35:663-686, vii. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 233] [Cited by in RCA: 187] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kornelius E, Chang KL, Yang YS, Huang JY, Ku MS, Lee KY, Ho SW. Epidemiology and factors associated with mortality of thyroid storm in Taiwan: a nationwide population-based study. Intern Emerg Med. 2021;16:601-607. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Galindo RJ, Hurtado CR, Pasquel FJ, García Tome R, Peng L, Umpierrez GE. National Trends in Incidence, Mortality, and Clinical Outcomes of Patients Hospitalized for Thyrotoxicosis With and Without Thyroid Storm in the United States, 2004-2013. Thyroid. 2019;29:36-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 11.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Klubo-Gwiezdzinska J, Wartofsky L. Thyroid emergencies. Med Clin North Am. 2012;96:385-403. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Swee du S, Chng CL, Lim A. Clinical characteristics and outcome of thyroid storm: a case series and review of neuropsychiatric derangements in thyrotoxicosis. Endocr Pract. 2015;21:182-189. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 11. | Angell TE, Lechner MG, Nguyen CT, Salvato VL, Nicoloff JT, LoPresti JS. Clinical features and hospital outcomes in thyroid storm: a retrospective cohort study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100:451-459. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ono Y, Ono S, Yasunaga H, Matsui H, Fushimi K, Tanaka Y. Factors Associated With Mortality of Thyroid Storm: Analysis Using a National Inpatient Database in Japan. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95:e2848. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Bourcier S, Coutrot M, Kimmoun A, Sonneville R, de Montmollin E, Persichini R, Schnell D, Charpentier J, Aubron C, Morawiec E, Bigé N, Nseir S, Terzi N, Razazi K, Azoulay E, Ferré A, Tandjaoui-Lambiotte Y, Ellrodt O, Hraiech S, Delmas C, Barbier F, Lautrette A, Aissaoui N, Repessé X, Pichereau C, Zerbib Y, Lascarrou JB, Carreira S, Reuter D, Frérou A, Peigne V, Fillatre P, Megarbane B, Voiriot G, Combes A, Schmidt M. Thyroid Storm in the ICU: A Retrospective Multicenter Study. Crit Care Med. 2020;48:83-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Elmenyar E, Aoun S, Al Saadi Z, Barkumi A, Cander B, Al-Thani H, El-Menyar A. Data Analysis and Systematic Scoping Review on the Pathogenesis and Modalities of Treatment of Thyroid Storm Complicated with Myocardial Involvement and Shock. Diagnostics (Basel). 2023;13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Nai Q, Ansari M, Pak S, Tian Y, Amzad-Hossain M, Zhang Y, Lou Y, Sen S, Islam M. Cardiorespiratory Failure in Thyroid Storm: Case Report and Literature Review. J Clin Med Res. 2018;10:351-357. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Feldt-Rasmussen U, Emerson CH. Further thoughts on the diagnosis and diagnostic criteria for thyroid storm. Thyroid. 2012;22:1094-1095. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Klein I, Ojamaa K. Thyrotoxicosis and the heart. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 1998;27:51-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Mendoza A, Hollenberg AN. New insights into thyroid hormone action. Pharmacol Ther. 2017;173:135-145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 191] [Article Influence: 21.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Cappola AR, Desai AS, Medici M, Cooper LS, Egan D, Sopko G, Fishman GI, Goldman S, Cooper DS, Mora S, Kudenchuk PJ, Hollenberg AN, McDonald CL, Ladenson PW. Thyroid and Cardiovascular Disease: Research Agenda for Enhancing Knowledge, Prevention, and Treatment. Circulation. 2019;139:2892-2909. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Marrakchi S, Kanoun F, Idriss S, Kammoun I, Kachboura S. Arrhythmia and thyroid dysfunction. Herz. 2015;40 Suppl 2:101-109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Dietrich JW, Müller P, Leow MKS. Editorial: Thyroid hormones and cardiac arrhythmia. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022;13:1024476. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Dahl P, Danzi S, Klein I. Thyrotoxic cardiac disease. Curr Heart Fail Rep. 2008;5:170-176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Ahmad M, Reddy S, Barkhane Z, Elmadi J, Satish Kumar L, Pugalenthi LS. Hyperthyroidism and the Risk of Cardiac Arrhythmias: A Narrative Review. Cureus. 2022;14:e24378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Wartofsky L. Clinical criteria for the diagnosis of thyroid storm. Thyroid. 2012;22:659-660. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Silva JE, Bianco SD. Thyroid-adrenergic interactions: physiological and clinical implications. Thyroid. 2008;18:157-165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 158] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Lorlowhakarn K, Kitphati S, Songngerndee V, Tanathaipakdee C, Sinphurmsukskul S, Siwamogsatham S, Puwanant S, Ariyachaipanich A. Thyrotoxicosis-Induced Cardiomyopathy Complicated by Refractory Cardiogenic Shock Rescued by Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation. Am J Case Rep. 2022;23:e935029. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Sourial K, Borgan SM, Mosquera JE, Abdelghani L, Javaid A. Thyroid Storm-induced Severe Dilated Cardiomyopathy and Ventricular Tachycardia. Cureus. 2019;11:e5079. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Abera BT, Abera MA, Berhe G, Abreha GF, Gebru HT, Abraha HE, Ebrahim MM. Thyrotoxicosis and dilated cardiomyopathy in developing countries. BMC Endocr Disord. 2021;21:132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Soomro R, Campbell N, Campbell S, Lesniak C, Sullivan M, Ong R, Cheng J, A. Hossain M. Thyroid Storm Complicated by Multisystem Organ Failure Requiring Plasmapheresis to Bridge to Thyroidectomy: A Case Report and Literature Review. Clin Case Rep Rev. 2019;5. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 30. | Burch HB, Wartofsky L. Life-threatening thyrotoxicosis. Thyroid storm. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 1993;22:263-277. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Sosa JA. Textbook of Endocrine Surgery, 2nd Edition. Ann Surg. 2006;244:322. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Sakaan RA, Poole MA, Long B. Diltiazem-Induced Reversible Cardiogenic Shock in Thyroid Storm. Cureus. 2021;13:e19261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Arai M, Asaumi Y, Murata S, Matama H, Honda S, Otsuka F, Tahara Y, Kataoka Y, Nishimura K, Noguchi T. Thyroid Storm Patients With Elevated Brain Natriuretic Peptide Levels and Associated Left Ventricular Dilatation May Require Percutaneous Mechanical Support. Crit Care Explor. 2021;3:e0599. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Pokhrel B, Aiman W, Bhusal K. Thyroid Storm. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL) ineligible companies. Disclosure: Wajeeha Aiman declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies. Disclosure: Kamal Bhusal declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies: StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2023, StatPearls Publishing LLC.; 2023. |

| 35. | Elendu C, Amaechi DC, Amaechi EC, Chima-Ogbuiyi NL, Afuh RN, Arrey Agbor DB, Abdi MA, Nwachukwu NO, Oderinde OO, Elendu TC, Elendu ID, Akintunde AA, Onyekweli SO, Omoruyi GO. Diagnostic criteria and scoring systems for thyroid storm: An evaluation of their utility - comparative review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2024;103:e37396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Jiménez-Labaig P, Mañe JM, Rivero MP, Lombardero L, Sancho A, López-Vivanco G. Just an Acute Pulmonary Edema? Paraneoplastic Thyroid Storm Due to Invasive Mole. Case Rep Oncol. 2022;15:566-572. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Samra T, Kaur R, Sharma N, Chaudhary L. Peri-operative concerns in a patient with thyroid storm secondary to molar pregnancy. Indian J Anaesth. 2015;59:739-742. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Kofinas JD, Kruczek A, Sample J, Eglinton GS. Thyroid storm-induced multi-organ failure in the setting of gestational trophoblastic disease. J Emerg Med. 2015;48:35-38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 39. | Kinoshita H, Sugino H, Oka T, Ichikawa O, Shimonaga T, Sumimoto Y, Kashiwabara A, Sakai T. A case in which SGLT2 inhibitor is a contributing factor to takotsubo cardiomyopathy and heart failure. J Cardiol Cases. 2020;22:177-180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Wu WT, Hsu PC, Huang HL, Chen YC, Chien SC. A Case of Takotsubo Cardiomyopathy Precipitated by Thyroid Storm and Diabetic Ketoacidosis with Poor Prognosis. Acta Cardiol Sin. 2014;30:574-577. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Chang CH, Lian HW, Sung YF. Cystic Encephalomalacia in a Young Woman After Cardiac Arrest Due to Diabetic Ketoacidosis and Thyroid Storm. Cureus. 2022;14:e23707. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |