Published online Dec 9, 2025. doi: 10.5492/wjccm.v14.i4.109164

Revised: June 17, 2025

Accepted: September 16, 2025

Published online: December 9, 2025

Processing time: 212 Days and 2.8 Hours

The intra-arterial catheter is a fundamental tool in contemporary critical care medicine. Intra-arterial catheters are widely used for a range of diagnostic and therapeutic purposes, and catheter insertion is an important clinical skill for clinicians managing critically unwell patients. The concepts and practical implications of catheter design on procedural technique and outcomes are frequently overlooked. This narrative review describes the clinical application of arterial catheters, the evidence supporting their use, and the rationale for key device characteristics.

Core Tip: Given the variety of available catheter products, operator expertise, patient circumstances and healthcare settings, there is insufficient evidence to identify the best devices and catheterization techniques. Intra-arterial catheter insertion and utilization practices must be individualized.

- Citation: Yaxley J. Intra-arterial catheters: An evidence-based review of device design, function and application. World J Crit Care Med 2025; 14(4): 109164

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3141/full/v14/i4/109164.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5492/wjccm.v14.i4.109164

The intra-arterial catheter is a valuable tool for directing the management of critically ill patients. Intra-arterial catheters are utilized for approximately 40% of patients admitted to intensive care units (ICUs) in Europe and the United States[1-3], including many cases where they are placed in the emergency department or operating room prior to ICU arrival[3]. Intra-arterial catheters were developed more than 50 years ago to enable continuous invasive hemodynamic monitoring and reliable access to arterial circulation, thereby facilitating precise, responsive manipulation of the cardiovascular and cardiopulmonary systems in patients with tenuous hemodynamic states. Insertion of an intra-arterial catheter typically involves percutaneous access of an appropriately selected artery. Inserting a catheter transducer system directly into the arterial lumen provides more accurate blood pressure measurements than noninvasive methods in unstable patients and makes it easier for healthcare providers and more comfortable for patients when frequent arterial blood sampling is required[4,5].

Although intra-arterial catheter placement is an important and relatively straightforward skill that requires minimal equipment, complications and technical failures are common. Patient-level evidence to guide the use of intra-arterial catheters is limited. Ideal catheter properties include biocompatibility and hemocompatibility, resilience to kinking or collapsing, resistance to degradation, softness, and a comfortably small caliber. A greater appreciation by clinicians of theoretic design principles may refine practice and improve outcomes. This narrative review explores the process of intra-arterial catheter insertion, the impact of device structure, and external factors that influence outcomes. This article is intended for physicians who may be tasked with utilizing an intra-arterial catheter or treating critically ill patients.

Intra-arterial catheters are also known as arterial or intra-arterial lines and are hereafter referred to as arterial lines. This article implies radial arterial catheterization unless otherwise stated, although content is generally applicable to most insertion sites, and specifically relates to adult patients rather than pediatric. The terms ‘catheter’ and ‘cannula’ are used interchangeably. Some related issues are not discussed in this review, such as resuscitation goals, troubleshooting, and waveform interpretation.

A structured search of the PubMed database was performed from inception to June 2025 using a range of pertinent search terms and combinations, such as “arterial catheter” and “design”. Results were screened for relevance. A broad selection of articles was obtained, including clinical trials and commentaries. Additional papers were retrieved by manually searching reference lists. Articles were allowed in any language. Results of the literature search were synthesized to generate this narrative review, prioritizing publications with higher levels of evidence.

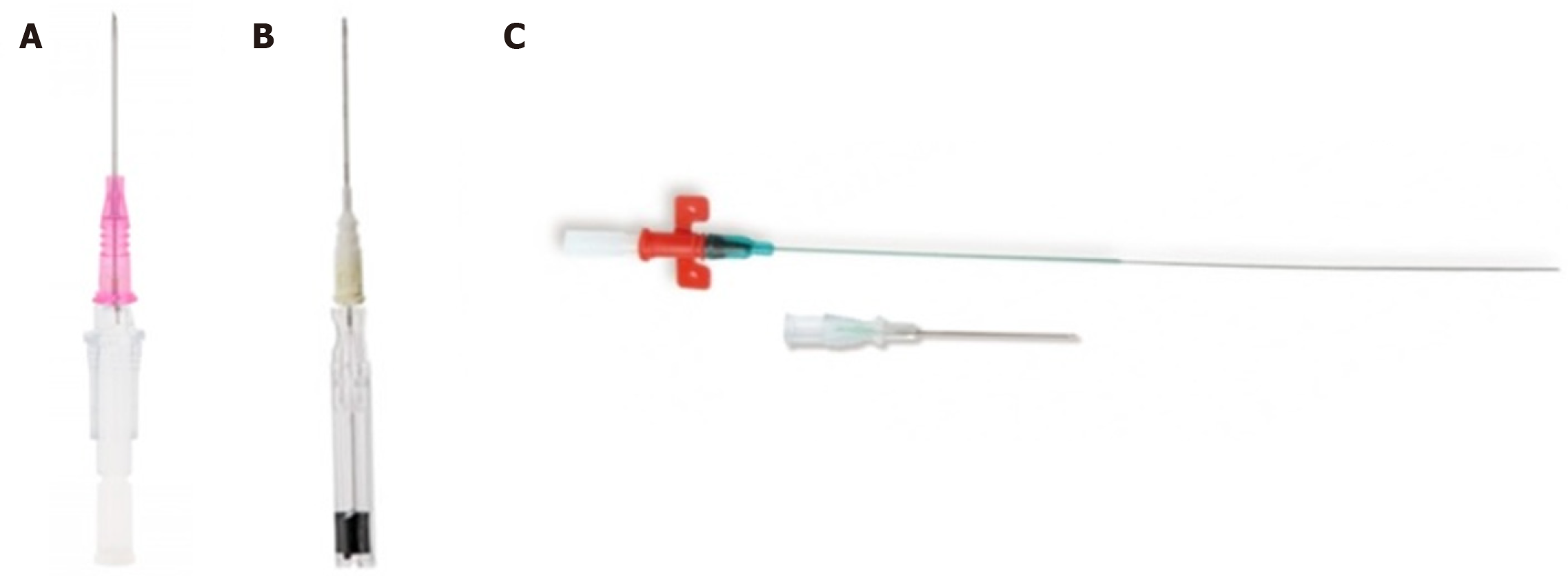

Three device categories are commonly used for arterial line insertion, each involving a specific procedural technique. These include the catheter-over-needle technique, integral-wire modified-Seldinger technique, and classic Seldinger technique (Figure 1). A standard peripheral intravenous cannula (e.g., BD Insyte, Becton Dickinson, UT, United States) represents the archetypal catheter-over-needle system in which a pliable sheath is advanced directly over an inner metallic needle after vessel puncture. The integral-wire modified-Seldinger method utilizes a coaxial assembly incor

There is limited evidence to support the superiority of one insertion method over another. In observational studies of radial arterial line insertions, Seldinger-based techniques employing a guidewire were associated with fewer puncture attempts and shorter procedure times than a catheter-over-needle technique[6]. In a South African randomized controlled trial (RCT) of 195 arterial line insertions in the ICU, the failure rates of the catheter-over-needle, integral-wire modified-Seldinger and Seldinger methods were 24%, 17% and 7%, respectively (P ≤ 0.02)[7]. In smaller prospective trials of patients undergoing elective surgery and anesthesia, there were no differences in overall catheterization success between an integral-wire modified-Seldinger method and a catheter-over-needle method[8-10].

Published comparisons are confounded by inconsistent clinician experience, patient populations, and frequency of ultrasound guidance. Outcomes may depend on operator expertise, and anecdotally, the catheter-over-needle method can be deployed just as effectively by experienced providers, particularly anesthetists, among whom this technique appears to be more common[11]. Providers in the South African RCT were relatively inexperienced registrars. Areas of difficulty for novice clinicians may be overcome with experience. The Seldinger technique may be preferred by many clinicians because arterial puncture is readily identified, whereas the feedback of continued pulsatile arterial flow is less pron

Most commonly marketed products are available in a range of hub shapes and profiles. Hubs can vary in height and length, as well as in the presence or absence of wings and ports. There are no robust data for the effect of hub design. When performing arterial line insertion with the catheter-over-needle approach, open cannula systems may be preferred over closed systems because the safeguard mechanisms in closed systems reduce versatility and may reduce the like

The intended catheterization site influences device suitability. Most arterial line insertion studies concern the radial artery but also likely apply to other peripheral sites. Arterial line placement in the large central femoral artery is almost always performed with the classic Seldinger technique. This perhaps reflects tradition and the fact that catheter-over-needle or modified-Seldinger systems of a suitable length for femoral access become unwieldy to handle.

Transducer signal quality and the accuracy of blood pressure readings are theoretically influenced by catheter length and cross-sectional area. In laboratory conditions, the resistance produced by a longer narrower catheter causes lower resonant frequency response and more signal damping with distortion of the arterial waveform compared to a shorter wider catheter. Catheter radius appears to be a stronger determinant of flow than length. However, observations from preclinical studies do not always translate into real-world practice. In human studies of standard arterial line products between 20G and 24G diameters, there was no significant difference in blood pressure measurements or waveforms[13,14].

The potential advantages of using a larger catheter gauge must be weighed against the increased risk of intravascular thrombosis. As catheter diameter increases relative to the vessel wall diameter, there is progressive obstruction to surrounding blood flow and a proportionate rise in thrombosis incidence. In an RCT of 30 patients in Turkey, those assigned to radial catheterization with a 22G or 20G cannula prior to general anesthesia had arterial occlusion rates of 6% and 26%, respectively (P = 0.02)[14]. Similarly, in an RCT of 108 patients comparing 20G and 18G radial arterial lines, the rates of occlusion were 8% and 34%, respectively (P ≤ 0.05). These findings are consistent with several non-randomized studies[15,16]. Some experts recommend a catheter-vessel ratio less than 45%[17,18]. A 20G catheter, the most common radial arterial line size for adults, has an outer diameter of approximately 1.1 mm (Table 1), while the average diameter of the radial artery at the wrist in adults is approximately 2.5 mm, giving an approximate ratio of 44%. Owing to the spacious diameter of the femoral artery, the rate of thrombotic complications is significantly lower for femoral arterial lines than for radial and other peripheral lines[19] (Table 1).

| Needle or catheter gauge | Needle or catheter outer diameter (mm) | Matching guidewire thickness (inches) | Gravity flow rate (mL/minute) |

| 22G | 0.7-0.9 | 0.014 | 35 |

| 21G | 0.8-0.9 | 0.018 | 60 |

| 20G | 0.9-1.1 | 0.025 | 65 |

| 18G | 1.2-1.3 | 0.035 | 100 |

Other disadvantages of a larger arterial line include increased procedural difficulty and hematoma formation. In the Turkish RCT, the 20G cannula group required twice as many puncture attempts (median of 1 vs 2 punctures, P = 0.02) and sustained more hematomas (33% vs 7%, P = 0.02) than the 22G group[14]. Further comparative trial data on bleeding risks are limited. Modern needles and catheters are manufactured with the thinnest possible walls to maximize their internal diameter while minimizing external diameter and maintaining integrity. Wall thickness differs by less than ~0.2 mm among currently available arterial line products.

An arterial line should be long enough to ensure adequate purchase within the target vessel. In prospective studies of peripheral intravenous cannulation in the emergency department, the incidence of dysfunction or dislodgement was significantly lower when at least 2.5 cm of cannula length was positioned within the vessel[20,21]. With average depths from the skin to the radial and femoral arteries in adults of approximately 0.3 cm and 1.7 cm, respectively, standard arterial line kits generally provide sufficient length and stability. Peripheral vascular catheters are manufactured in lengths typically ranging from 30 mm to 50 mm, with the specific dimensions determined somewhat arbitrarily by manufacturing practices and findings from experimental studies.

The optimal length of an arterial line remains uncertain, aside from ensuring that an adequate segment is positioned within the vessel lumen. In vivo, catheter length shows little association with thrombotic complications. Although it is common practice to use longer lines (e.g., Leadercath, Vygon, France) when extended use is anticipated, such as in the ICU, and shorter lines (e.g. BD Insyte, Becton Dickinson, UT, United States) when only brief use is expected, such as preoperatively for elective general anesthesia, this approach has not been formally evaluated.

Parameters of standard arterial line products that stocked in the author’s local hospitals are outlined in Table 2.

| Product | Pink BD Insyte | Blue BD Insyte | Vygon Leadercath | Arrow Quickflash | Arrow Integrated | Arrow Seldinger | BD Floswitch |

| Assembly style | CN | CN | S | IW | IW | S | CN |

| Intended insertion site | Radial | Radial | Radial | Radial | Radial | Femoral | Radial |

| Catheter material | Polyurethane | Polyurethane | Polyethylene | Polyurethane | Polyurethane | Polyurethane | Polyurethane |

| Catheter gauge | 20G | 22G | 20G | 20G | 20G | 18G | 20G |

| Catheter length (cm) | 3 | 2.5 | 8 | 3.8 | 4.5 | 16 | 4.5 |

| Introducer needle gauge | 21G | 23G | 20G | 21G | 22G | 18G | 21G |

| Introducer needle length (cm) | 3.8 | 7 | |||||

| Guidewire material | Stainless steel | Stainless steel | Stainless steel | Stainless steel | |||

| Guidewire gauge (inches) | 0.021 | 0.018 | 0.018 | 0.025 |

Contemporary vascular catheters are typically made with thermosensitive polyurethane. Alternative materials include polyethylene and polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE). Thermosensitive plastic is considered advantageous because it remains relatively stiff at room temperature, facilitating percutaneous insertion, while softening within body tissues to reduce the risk of endothelial injury. Because of its favorable properties, polyurethane has gradually become the predominant material for vascular catheters. Polyethylene and PTFE are stiffer polymers than polyurethane. In observational and preclinical studies, polyurethane peripheral catheters have consistently outperformed PTFE catheters in terms of phlebitis rates, dwell time, ease of percutaneous advancement, and clinician-reported satisfaction[7,22-30]. Comparative studies of PTFE vs polyethylene-like catheters[31,32] and polyethylene vs polyurethane catheters[33-37] reported conflicting results. Silicone is a soft material infrequently used for arterial lines. Silicone catheters have demonstrated poorer patency rates in observational studies, consistent with studies in animal models in which silicone’s porosity promoted intraluminal thrombosis and its flexibility allowed luminal collapse under negative suction during blood aspiration[38]. Currently, evidence is insufficient to support the routine use of catheters embedded with antimicrobial or antithrombotic surface coatings.

Percutaneous vessel access requires a rigid, sharp entry needle, either housed within a cannula, as in catheter-over-needle systems, or be used separately to introduce an access wire, as in Seldinger-based systems. Needles are typically manu

Arterial line insertion is frequently performed under ultrasound guidance. Practitioners should be aware that the needle in a catheter-over-needle device is less echogenic than a bare metal needle because of blurring by the outer plastic sheath.

Seldinger-based radial arterial line kits contain straight-tipped guidewires. Straight-tipped wires pass more freely through small target vessels than J-tipped wires[41,42]. Femoral arterial line placement is usually performed over a J-tipped guidewire. J-wires are theoretically atraumatic to intravascular endothelium and easily navigate through the femoral artery’s large diameter[43,44]. The arc of a J-tip may also prevent misdirection into small femoral arterial tribut

Guidewire tips are usually soft and floppy relative to their firmer shaft. The metallic spring wires contained in commercial arterial line kits are constructed from stainless steel or nitinol. Steel provides more stiffness whereas nitinol is more pliant and less prone to kinking. Steel and nitinol are hydrophobic and comfortable to handle. A wide variety of guidewires are available, supported by extensive ex vivo experience but limited by a paucity of comparative clinical trials. Therefore, the wire products deployed in practice are typically dependent on operator preferences and judgment. The selected wire and introducer needle must have concordant diameters.

The approach to arterial line insertion relies on physician discretion. Decisions must be nuanced and individualized because there is insufficient evidence to uniformly recommend a superior arterial line device or insertion method. It is reasonable to conclude that there are no major differences between a catheter-over-needle and a Seldinger-based technique, although Seldinger techniques may be more successful for inexperienced operators. In general, the physical and chemical properties of standard commercially available products are sufficiently similar that brand and style selection is determined primarily by physician preference and experience.

Standard indications for arterial line placement include the need for continuous hemodynamic monitoring, repeated arterial blood gas measurements or regular phlebotomy in a critically ill patient, and situations where non-invasive recordings would be considered unreliable. However, definitive data that directly substantiate these indications and the use of arterial lines more broadly are somewhat limited.

The utility of arterial lines is inferred indirectly from evidence that superior blood pressure control improves outcomes across numerous conditions, as well as from their perceived value in facilitating close monitoring of patients receiving vasoactive medications. The presence of arterial lines has been associated with improved blood pressure stability in a range of acute indications[45-49], and invasive monitoring is associated with reduced mortality in septic patients in the ICU[50]. Arterial line placement is recommended for individuals with shock requiring vasopressors[51-53] and should also be considered as a management aid in individuals with blood pressure lability.

The need for hemodynamic monitoring is broadly interpreted and on a case-by-case basis. For example, appropriate indications could include intra-operative use during cardiac surgery, treatment of heart failure with non-invasive ventilation or acute respiratory distress syndrome with mechanical ventilation, and observation following subarachnoid hemorrhage. The subset of patients with such indications who warrant arterial line placement is poorly defined. There is also no consensus on when non-invasive readings would be considered unreliable; however, common scenarios may include obesity or tachyarrhythmias. The threshold frequency of blood draws at which an indwelling catheter becomes preferable to repeated needle sticks for blood gas analysis is unknown; however, many clinicians recommend catheter insertion when arterial sample is anticipated at least once daily.

Contraindications to arterial line placement may be considered relative or absolute, depending on the urgency of monitoring and the availability of alternative insertion sites. Arterial line insertion should be avoided at sites with local infection, anatomical abnormalities, proximal traumatic injuries, severe Raynaud’s syndrome or peripheral vascular disease. Sites with vulnerable circulation should be avoided if feasible, such as the brachial artery. The role of the Allen’s test before radial catheterization is controversial. Other contraindications include coagulopathy, thrombocytopenia, or an environment in which resources are inadequate to properly monitor the patient.

The steps of arterial line insertion are described elsewhere[54,55] and will not be covered in detail in this article. However, we explore several technical points because of their particular educational value in improving procedural success. A working knowledge of the basic components and skills of arterial line insertion is assumed.

Site selection: The radial artery is the most frequent site for arterial line insertion. In a large Australian ICU dataset, radial and femoral arterial lines accounted for 83% and 8% of arterial lines, respectively[56]. In an American anesthesia database, more than 90% of arterial lines for intraoperative indications were radial[57]. Less common sites include the brachial, dorsalis pedis and axillary arteries. Radial arterial lines are associated with reduced infective and bleeding complications, are comfortable for patients, and are relatively easy to place. Femoral arterial lines are less likely to dislodge or thrombose, more accurately measure central arterial pressure, and are also relatively straightforward to place. The right radial artery is used more frequently than the left, as accessing the right side of the patient is reportedly more ergonomic for right-handed proceduralists[6,56]. Although comfort presumably optimizes success, the effect of laterality on outcomes has not been examined. For radial arterial line insertion, the distal quarter of the forearm at least 4 cm from the wrist joint was associated with improved procedural success vs distal or proximal locations along the radial artery in small RCTs when ultrasound guidance was used[58,59], whereas a lower site within 4 cm of the wrist was superior in observational studies when placing catheters blindly[60-62].

Patient positioning: Moderate wrist dorsiflexion raises the radial artery closer to the skin and increases vessel diameter. Prospective trial evidence indicates that dorsiflexion to approximately 45 degrees improves insertion success compared with both greater and lesser degrees of dorsiflexion[63,64]. The optimal method for maintaining wrist positioning has not been formally studied. In common practice, the hand is supinated and immobilized by placing a towel or board beneath the wrist and gently securing the hand and thumb with tape to prevent movement. Experts advocate advancing the needle at an angle of 15-45 degrees. The optimal operator position and the most effective technique for gripping the needle and cannula during placement remain uncertain.

Ultrasound guidance: Ultrasound is increasingly utilized for arterial line insertion and many guidelines now state that ultrasound guidance should be considered. Regarding radial arterial line placement, meta-analyses of RCTs demon

Local anesthesia: Local anesthesia should be administered prior to the procedure unless the patient is deeply sedated. There is strong evidence that local anesthesia reduces pain during arterial puncture[73-75]. Whether local anesthetic instillation affects cannulation success is unclear; however, a survey of junior doctors in Britain found that most did not perceive the use of local anesthesia as making the procedure more difficult[73].

Sterility and antibiotic prophylaxis: A sterile technique including skin antisepsis, drapes and sterile gloves is recom

Routine intravenous peri-procedural antibiotic prophylaxis is not recommended by guidelines. This advice is based on the findings of randomized trials of central venous catheters[76,79,80]. The incidence of catheter-associated infection appears similar for arterial lines and central venous catheters[81,82].

Catheter cares: Some of the key nursing and maintenance practices that affect arterial line outcomes are summarized in Table 3[76,83-90].

| Daily care | Explanation |

| Dressings | The optimal dressing products, frequency of dressing changes and frequency of site inspections are uncertain. A common practice is to replace dressings weekly or sooner if they become loose or unclean. Local institutional policies should be followed. A topical cleansing agent should be applied to the catheter site during a dressing change to prevent infection[76,83] |

| Antibiotic prophylaxis | Daily antimicrobial prophylaxis to prevent infection while the arterial line is in situ is not advised, as evidence is insufficient |

| Securement | Both sutures and adhesive dressings are suitable methods for catheter securement. No consistent differences in adverse events have been demonstrated[84]. Sutures were associated with fewer arterial line displacements in retrospective studies compared with sutureless fixation dressings but may predispose to infection |

| Flushing | A continuous slow infusion of normal saline is delivered through the arterial line to maintain patency. A pressure bag attached to the transducer system is commonly inflated to 300 mmHg to deliver fluid at a rate of ~3 mL/hour. This configuration reduced adverse events compared with intermittent flushes or infusion rates[85,86]. Heparin does not improve patency over normal saline[87] |

| Routine catheter changes | Routine arterial line changes are not recommended. Regular arterial line replacement does not reduce the risk of catheter-related sepsis as opposed to a process of replacement only when clinically indicated[88-90]. The relationship between catheter dwell time and the incidence of infection is unclear |

The main mechanical complications of arterial line placement include thrombosis and embolism, vessel injury, ischemia, and bleeding. Infective complications may be local or systemic. As mentioned in preceding sections, the frequency and severity of complications vary with patient circumstances, insertion sites, duration of use, procedural technique and, to a much lesser extent, device characteristics.

One of the strongest predictors of procedure-related complications may be operator experience. There is ample literature describing a clear association between inexperience and worse procedural outcomes across a range of critical care procedures[91,92]. Nonetheless, the effect of operator experience specifically for arterial line placement is poorly studied. Other notable risk factors for arterial line complications at any site include hypotension, peripheral vascular disease, catheterization under emergent conditions, and illness severity[56].

An individualized approach to arterial line placement is needed in many circumstances without directly relevant studies. For example, obesity may reduce the reliability of pulse palpation and may increase the complications of femoral arterial line placement. In individuals with severe atherosclerosis, who are at greater risk of mechanical complications, the femoral artery may be a more appropriate insertion site than smaller arteries. Alternatively, during radial cannulation, a more cephalad site along the radial artery may be considered. In patients with an existing arteriovenous fistula for hemodialysis, or in those anticipated to require one in the future, radial cannulation may compromise long-term patency and is therefore discouraged. Finally, in operative settings, anesthetists must anticipate surgical steps to ensure uninterrupted monitoring and that the catheter is reachable throughout surgery. For example, a radial arterial line is typically avoided in cardiac surgery when unilateral radial artery harvest is planned, whereas bilateral lines may be required during aortic surgery.

There are no published guidelines specifically dedicated to the insertion and maintenance of arterial lines. However, continuous hemodynamic monitoring is often recommended as a management component, such as in guidelines for sepsis[89], neurosurgery[93], and cardiac anesthesia[94].

Arterial lines are prevalent in contemporary practice, although their utilization is declining[95,96]. For example, Medicare data from Australia demonstrate that the per capita frequency of arterial line placement roughly halved between 1994 and 2024[95]. Possible explanations include improvements in non-invasive monitoring technologies, reduced morbidity with the uptake of minimally invasive surgery over traditional open or radical approaches, and a lack of evidence justifying the role of invasive hemodynamic monitoring in most situations[91].

Despite decades of experience, the implementation of arterial lines continues to be subject to considerable regional heterogeneity and diverse physician and center practices[3,57,97-99]. The use of arterial lines has increased over time in emergency departments and among patients with sepsis but appears to have declined in intraoperative settings and in patients with diagnoses other than sepsis. In emergency departments in the United States, arterial lines are more likely to be placed by physicians in academic centers than in rural settings[99]. Studies from Australia and the United States report that about two-thirds of arterial lines are placed in ICUs, while about one-third are placed in other areas[57].

Invasive monitoring may be underutilized in some situations that are traditionally managed without the placement of an arterial line. Arterial lines are seldom used in coronary care units or respiratory high-dependency bays, despite the frequent need in these settings for advanced therapies such as non-invasive ventilation or inotropic support. Many patients admitted to these units could benefit from continuous monitoring; however, few such studies have been performed, and further research to identify unrecognized indications for arterial line placement is warranted. Because the use of arterial lines is essentially confined to ICUs in most hospitals, extension into other settings must be accompanied by proof of improved patient outcomes and cost-effectiveness, as well as provision of adequate healthcare resources and training.

Considering the prevalence of arterial line use in contemporary practice, the overall body of relevant literature is lacking and few recent scientific advancements have been made. The results of a small number of relevant prospective clinical trials that are currently underway will be helpful: Two upcoming RCTs are evaluating arterial line insertion sites, and one is evaluating the utility of invasive monitoring in arthroscopic shoulder surgery.

A host of non-invasive alternatives to arterial lines for continuous monitoring are being investigated in preclinical and clinical studies. Proposed options include wearable sensor technologies based on bioimpedance, photoplethysmography, electrocardiography, tonometry, or ultrasound. The technology appears promising but is yet to enter mainstream practice. In the future, non-invasive devices may permit closer monitoring for patients in lower-acuity or remote environments like general medical wards or the community. Additional research is necessary before non-invasive modalities can acceptably replace the present clinical approach to hemodynamic monitoring and treatment.

Arterial line insertion is a crucial skill that enables physicians to provide responsive, exact care of critically ill patients. There is a wide variety of available arterial line products in current practice, without convincing evidence of superiority for one over another. The choice of device and insertion technique must be decided through a combination of theoretical concepts, patient circumstances, imperfect evidence, and physician judgment. The value of arterial lines is potentially unrealized in many conditions, and further evaluation of appropriate indications and practical application is needed.

| 1. | Muller G, Kamel T, Contou D, Ehrmann S, Martin M, Quenot JP, Lacherade JC, Boissier F, Monnier A, Vimeux S, Brunet Houdard S, Tavernier E, Boulain T. Early versus differed arterial catheterisation in critically ill patients with acute circulatory failure: a multicentre, open-label, pragmatic, randomised, non-inferiority controlled trial: the EVERDAC protocol. BMJ Open. 2021;11:e044719. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Gershengorn HB, Wunsch H, Scales DC, Zarychanski R, Rubenfeld G, Garland A. Association between arterial catheter use and hospital mortality in intensive care units. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:1746-1754. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Gershengorn HB, Garland A, Kramer A, Scales DC, Rubenfeld G, Wunsch H. Variation of arterial and central venous catheter use in United States intensive care units. Anesthesiology. 2014;120:650-664. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Lehman LW, Saeed M, Talmor D, Mark R, Malhotra A. Methods of blood pressure measurement in the ICU. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:34-40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 161] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Wax DB, Lin HM, Leibowitz AB. Invasive and concomitant noninvasive intraoperative blood pressure monitoring: observed differences in measurements and associated therapeutic interventions. Anesthesiology. 2011;115:973-978. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Armstrong C, Butson B, Kwa P. Arterial line insertion. Emerg Med Australas. 2023;35:142-147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Beards SC, Doedens L, Jackson A, Lipman J. A comparison of arterial lines and insertion techniques in critically ill patients. Anaesthesia. 1994;49:968-973. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Mangar D, Thrush DN, Connell GR, Downs JB. Direct or modified Seldinger guide wire-directed technique for arterial catheter insertion. Anesth Analg. 1993;76:714-717. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Yildirim V, Ozal E, Cosar A, Bolcal C, Acikel CH, Kiliç S, Kuralay E, Guzeldemir ME. Direct versus guidewire-assisted pediatric radial artery cannulation technique. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2006;20:48-50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Singla D, Mangla M, Agarwal A, Kumari R. Comparative Evaluation of Three Different Techniques of Radial Artery Cannulation: A Prospective Randomised Study. Cureus. 2024;16:e52326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Roberts JR, Custalow CB, Thomsen TW, Hedges JR. Roberts and Hedges’ Clinical Procedures in Emergency Medicine. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders, 2014. |

| 12. | Asai T, Hidaka I, Kawashima A, Miki T, Inada K, Kawachi S. Efficacy of catheter needles with safeguard mechanisms. Anaesthesia. 2002;57:572-577. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Oh H, Choe SH, Kim YJ, Yoon HK, Lee HC, Park HP. Intraarterial catheter diameter and dynamic response of arterial pressure monitoring system: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Monit Comput. 2022;36:387-395. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Eker HE, Tuzuner A, Yilmaz AA, Alanoglu Z, Ates Y. The impact of two arterial catheters, different in diameter and length, on postcannulation radial artery diameter, blood flow, and occlusion in atherosclerotic patients. J Anesth. 2009;23:347-352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Bedford RF. Radial arterial function following percutaneous cannulation with 18- and 20-gauge catheters. Anesthesiology. 1977;47:37-39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Davis FM, Stewart JM. Radial artery cannulation. A prospective study in patients undergoing cardiothoracic surgery. Br J Anaesth. 1980;52:41-47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Imbrìaco G, Monesi A, Spencer TR. Preventing radial arterial catheter failure in critical care - Factoring updated clinical strategies and techniques. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med. 2022;41:101096. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Spencer TR, Mahoney KJ. Reducing catheter-related thrombosis using a risk reduction tool centered on catheter to vessel ratio. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2017;44:427-434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Scheer B, Perel A, Pfeiffer UJ. Clinical review: complications and risk factors of peripheral arterial catheters used for haemodynamic monitoring in anaesthesia and intensive care medicine. Crit Care. 2002;6:199-204. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 502] [Cited by in RCA: 551] [Article Influence: 23.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Pandurangadu AV, Tucker J, Brackney AR, Bahl A. Ultrasound-guided intravenous catheter survival impacted by amount of catheter residing in the vein. Emerg Med J. 2018;35:550-555. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Bahl A, Hijazi M, Chen NW, Lachapelle-Clavette L, Price J. Ultralong Versus Standard Long Peripheral Intravenous Catheters: A Randomized Controlled Trial of Ultrasonographically Guided Catheter Survival. Ann Emerg Med. 2020;76:134-142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | McKee JM, Shell JA, Warren TA, Campbell VP. Complications of intravenous therapy: a randomized prospective study--Vialon vs. Teflon. J Intraven Nurs. 1989;12:288-295. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Treuren BC, Galletly DC. A comparison of intravenous cannulae available in New Zealand. Anaesth Intensive Care. 1990;18:540-546. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Eriksson E, Larsson N, Nitescu P, Appelgren L, Linder LE, Curelaru I. Penetration forces in cannulation of the dorsal veins of the hand: I. A comparison between polyurethane (Insyte) and polytetrafluoroethylene (Venflon) cannulae. Results of a study in volunteers compared with those from an in vitro study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1991;35:306-314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Treuren BC, Yusuf A, Galletly DC, Robinson BJ. A comparison of three ported cannulae available in New Zealand. Anaesth Intensive Care. 1993;21:337-341. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Lambert D, Martin C, Perrin G, Saux P, Papazian L, Gouin F. [Risk of thrombosis in prolonged catheterization of the radial artery: comparison of 2 types of catheters]. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim. 1990;9:408-411. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Matthews R, Gavin NC, Marsh N, Marquart-Wilson L, Keogh S. Peripheral intravenous catheter material and design to reduce device failure: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Infect Dis Health. 2023;28:298-307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Gaukroger PB, Roberts JG, Manners TA. Infusion thrombophlebitis: a prospective comparison of 645 Vialon and Teflon cannulae in anaesthetic and postoperative use. Anaesth Intensive Care. 1988;16:265-271. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Maki DG, Ringer M. Risk factors for infusion-related phlebitis with small peripheral venous catheters. A randomized controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 1991;114:845-854. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 367] [Cited by in RCA: 339] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Kuş B, Büyükyılmaz F. Effectiveness of vialon biomaterial versus teflon catheters for peripheral intravenous placement: A randomized clinical trial. Jpn J Nurs Sci. 2020;17:e12328. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Davis FM. Radial artery cannulation: influence of catheter size and material on arterial occlusion. Anaesth Intensive Care. 1978;6:49-53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Slogoff S, Keats AS, Arlund C. On the safety of radial artery cannulation. Anesthesiology. 1983;59:42-47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 267] [Cited by in RCA: 225] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Thomsen HK, Kjeldsen K, Hansen JF. Thrombogenic properties of arterial catheters: a scanning electron microscopic examination of the surface structure. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn. 1977;3:351-358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Touquet S, Martin P, Poisson DM, Bercault N, Fleury C, Gueveler C. [Comparison of polyurethane and polyethylene for central venous catheter in intensive care units]. Agressologie. 1992;33 Spec No 3:140-142. [PubMed] |

| 35. | Poisson DM, Touquet S, Bercault N, Arbeille B. [Polyurethane versus polyethylene: in vivo randomized study of infectious complications of central catheterization]. Pathol Biol (Paris). 1991;39:668-673. [PubMed] |

| 36. | Pottecher T, Forrler M, Picardat P, Krause D, Bellocq JP, Otteni JC. Thrombogenicity of central venous catheters: prospective study of polyethylene, silicone and polyurethane catheters with phlebography or post-mortem examination. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 1984;1:361-365. [PubMed] |

| 37. | Hecker JF, Scandrett LA. Roughness and thrombogenicity of the outer surfaces of intravascular catheters. J Biomed Mater Res. 1985;19:381-395. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Teilmann AC, Falkenberg MK, Hau J, Abelson KS. Comparison of silicone and polyurethane catheters for the catheterization of small vessels in mice. Lab Anim (NY). 2014;43:397-403. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Tanabe H, Oosawa K, Miura M, Mizuno S, Yokota T, Ueda T, Zushi Y, Nagata M, Murayama R, Abe-Doi M, Sanada H. Effect of a thin-tipped short bevel needle for peripheral intravenous access on the compressive deformation and displacement of the vein: A preclinical study. J Vasc Access. 2024;25:265-273. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Kondo M, Kim SJ, Fujiwara Y, Iinuma A, Koji K, Irie Y, Tazumi K, Noguchi S, Monden M. Evaluation of ten intravenous catheters for operability and safety in the infusion room. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 2004;31:2005-2008. [PubMed] |

| 41. | Kim EH, Kang P, Song IS, Ji SH, Jang YE, Lee JH, Kim HS, Kim JT. Straight-tip guidewire versus J-tip guidewire for central venous catheterisation in neonates and small infants: A randomised controlled trial. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2022;39:656-661. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Jia H, Zhang K, Han J, Liu Q, Chen P, Wang Y, Huang S. Short peripheral intravenous cannula and straight-tip guide wire in ultrasound-guided neonatal central venous catheterization. J Vasc Access. 2023;24:1332-1339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Gay DA, Edwards AJ, Puckett MA, Roobottom CA. A comparison of a 'J' wire and a straight wire in successful antegrade cannulation of the superficial femoral artery. Clin Radiol. 2005;60:112-115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Ben-Dor I, Maluenda G, Mahmoudi M, Torguson R, Xue Z, Bernardo N, Lindsay J, Satler LF, Pichard AD, Waksman R. A novel, minimally invasive access technique versus standard 18-gauge needle set for femoral access. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;79:1180-1185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Green M, Paulus DA, Roan VP, van der Aa J. Comparison between oscillometric and invasive blood pressure monitoring during cardiac surgery. Int J Clin Monit Comput. 1984;1:21-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Jacquet-Lagrèze M, Bredèche F, Louyot C, Pozzi M, Grinberg D, Flagiello M, Portran P, Ruste M, Schweizer R, Fellahi JL. Central Versus Peripheral Arterial Pressure Monitoring in Patients Undergoing Cardiac Surgery: A Prospective Observational Study. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2023;37:1631-1638. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Kouz K, Wegge M, Flick M, Bergholz A, Moll-Khosrawi P, Nitzschke R, Trepte CJC, Krause L, Sessler DI, Zöllner C, Saugel B. Continuous intra-arterial versus intermittent oscillometric arterial pressure monitoring and hypotension during induction of anaesthesia: the AWAKE randomised trial. Br J Anaesth. 2022;129:478-486. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Dekker PK, Noe N, Bekeny JC, Lavin C, Zolper EG, Song DH, Fan KL. Intraoperative Invasive Blood Pressure Monitoring in Flap-Based Breast Reconstruction: Does It Change Outcomes? Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2021;9:e3284. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Naylor AJ, Sessler DI, Maheshwari K, Khanna AK, Yang D, Mascha EJ, Suleiman I, Reville EM, Cote D, Hutcherson MT, Nguyen BM, Elsharkawy H, Kurz A. Arterial Catheters for Early Detection and Treatment of Hypotension During Major Noncardiac Surgery: A Randomized Trial. Anesth Analg. 2020;131:1540-1550. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 50. | Xiao L, Shen P, Han X, Yu Y. Association between delayed invasive blood pressure monitoring and all-cause mortality in intensive care unit patients with sepsis: a retrospective cohort study. Front Med (Lausanne). 2024;11:1446890. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Evans L, Rhodes A, Alhazzani W, Antonelli M, Coopersmith CM, French C, Machado FR, Mcintyre L, Ostermann M, Prescott HC, Schorr C, Simpson S, Wiersinga WJ, Alshamsi F, Angus DC, Arabi Y, Azevedo L, Beale R, Beilman G, Belley-Cote E, Burry L, Cecconi M, Centofanti J, Coz Yataco A, De Waele J, Dellinger RP, Doi K, Du B, Estenssoro E, Ferrer R, Gomersall C, Hodgson C, Hylander Møller M, Iwashyna T, Jacob S, Kleinpell R, Klompas M, Koh Y, Kumar A, Kwizera A, Lobo S, Masur H, McGloughlin S, Mehta S, Mehta Y, Mer M, Nunnally M, Oczkowski S, Osborn T, Papathanassoglou E, Perner A, Puskarich M, Roberts J, Schweickert W, Seckel M, Sevransky J, Sprung CL, Welte T, Zimmerman J, Levy M. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: International Guidelines for Management of Sepsis and Septic Shock 2021. Crit Care Med. 2021;49:e1063-e1143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 306] [Cited by in RCA: 1724] [Article Influence: 344.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 52. | Cecconi M, De Backer D, Antonelli M, Beale R, Bakker J, Hofer C, Jaeschke R, Mebazaa A, Pinsky MR, Teboul JL, Vincent JL, Rhodes A. Consensus on circulatory shock and hemodynamic monitoring. Task force of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Intensive Care Med. 2014;40:1795-1815. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 947] [Cited by in RCA: 1131] [Article Influence: 94.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Yu Y, Gong Y, Hu B, Ouyang B, Pan A, Liu J, Liu F, Shang XL, Yang XH, Tu G, Wang C, Ma S, Fang W, Liu L, Liu J, Chen D. Expert consensus on blood pressure management in critically ill patients. J Intensive Med. 2023;3:185-203. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Tegtmeyer K, Brady G, Lai S, Hodo R, Braner D. Videos in Clinical Medicine. Placement of an arterial line. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:e13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Ailon J, Mourad O, Chien V, Saun T, Dev SP. Videos in clinical medicine. Ultrasound-guided insertion of a radial arterial catheter. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:e21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Schults JA, Young ER, Marsh N, Larsen E, Corley A, Ware RS, Murgo M, Alexandrou E, McGrail M, Gowardman J, Charles KR, Regli A, Yasuda H, Rickard CM; RSVP Study Investigators. Risk factors for arterial catheter failure and complications during critical care hospitalisation: a secondary analysis of a multisite, randomised trial. J Intensive Care. 2024;12:12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Nuttall G, Burckhardt J, Hadley A, Kane S, Kor D, Marienau MS, Schroeder DR, Handlogten K, Wilson G, Oliver WC. Surgical and Patient Risk Factors for Severe Arterial Line Complications in Adults. Anesthesiology. 2016;124:590-597. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Yücel ED, Tekgul ZT, Okur O. The distal quarter of the forearm is the optimal insertion site for ultrasound-guided radial artery cannulation: A randomized controlled trial. J Vasc Access. 2024;25:538-545. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Wu XL, Wang JJ, Yuan DQ, Chen WT. Ultrasound-guided radial artery catheterization at different sites: a prospective and randomized study. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2022;26:415-421. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Imbriaco G, Monesi A, Giugni A, Cilloni N. Radial artery cannulation in intensive care unit patients: Does distance from wrist joint increase catheter durability and functionality? J Vasc Access. 2021;22:561-567. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Kaye J, Heald GR, Morton J, Weaver T. Patency of radial arterial catheters. Am J Crit Care. 2001;10:104-111. [PubMed] |

| 62. | Riachy M, Riachy E, Sleilaty G, Dabar G, Yazigi A, Khayat G. [Reliability and survival of arterial catheters: optimal dynamic response]. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim. 2007;26:119-124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Melhuish TM, White LD. Optimal wrist positioning for radial arterial cannulation in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Emerg Med. 2016;34:2372-2378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Pandey R, Ashraf H, Bhalla AP, Garg R. Optimal wrist angulation shortens time needed for radial artery catheterization: a prospective, randomized, and blinded study. Acta Anaesthesiol Belg. 2012;63:187-190. [PubMed] |

| 65. | Zhao W, Peng H, Li H, Yi Y, Ma Y, He Y, Zhang H, Li T. Effects of ultrasound-guided techniques for radial arterial catheterization: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Emerg Med. 2021;46:1-9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Moussa Pacha H, Alahdab F, Al-Khadra Y, Idris A, Rabbat F, Darmoch F, Soud M, Zaitoun A, Kaki A, Rao SV, Kwok CS, Mamas MA, Alraies MC. Ultrasound-guided versus palpation-guided radial artery catheterization in adult population: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am Heart J. 2018;204:1-8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Peters C, Schwarz SK, Yarnold CH, Kojic K, Kojic S, Head SJ. Ultrasound guidance versus direct palpation for radial artery catheterization by expert operators: a randomized trial among Canadian cardiac anesthesiologists. Can J Anaesth. 2015;62:1161-1168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Quan Z, Tian M, Chi P, Cao Y, Li X, Peng K. Modified short-axis out-of-plane ultrasound versus conventional long-axis in-plane ultrasound to guide radial artery cannulation: a randomized controlled trial. Anesth Analg. 2014;119:163-169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Gutte S, Azim A, Poddar B, Gurjar M, Kumar A. Arterial cannulation in adult critical care patients: A comparative study between ultrasound guidance and palpation technique. Med Intensiva (Engl Ed). 2023;47:391-401. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Marquis-Gravel G, Tremblay-Gravel M, Lévesque J, Généreux P, Schampaert E, Palisaitis D, Doucet M, Charron T, Terriault P, Tessier P. Ultrasound guidance versus anatomical landmark approach for femoral artery access in coronary angiography: A randomized controlled trial and a meta-analysis. J Interv Cardiol. 2018;31:496-503. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Sorrentino S, Nguyen P, Salerno N, Polimeni A, Sabatino J, Makris A, Hennessy A, Giustino G, Spaccarotella C, Mongiardo A, De Rosa S, Juergens C, Indolfi C. Standard Versus Ultrasound-Guided Cannulation of the Femoral Artery in Patients Undergoing Invasive Procedures: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J Clin Med. 2020;9:677. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Jolly SS, AlRashidi S, d'Entremont MA, Alansari O, Brochu B, Heenan L, Skuriat E, Tyrwhitt J, Raco M, Tsang M, Valettas N, Velianou JL, Sheth T, Sibbald M, Mehta SR, Pinilla-Echeverri N, Schwalm JD, Natarajan MK, Kelly A, Akl E, Tawadros S, Camargo M, Faidi W, Bauer J, Moxham R, Nkurunziza J, Dutra G, Winter J. Routine Ultrasonography Guidance for Femoral Vascular Access for Cardiac Procedures: The UNIVERSAL Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2022;7:1110-1118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Lightowler JV, Elliott MW. Local anaesthetic infiltration prior to arterial puncture for blood gas analysis: a survey of current practice and a randomised double blind placebo controlled trial. J R Coll Physicians Lond. 1997;31:645-646. [PubMed] |

| 74. | Beaumont M, Goret M, Orione C, Fauche A, Nowak E, Dion A, Darnois V, Tromeur C, Cogulet V, Leroyer C, Couturaud F, Le Mao R. Effect of Local Anesthesia on Pain During Arterial Puncture: The GAEL Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial. Respir Care. 2021;66:976-982. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Giner J, Casan P, Belda J, González M, Miralda RM, Sanchis J. Pain during arterial puncture. Chest. 1996;110:1443-1445. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | O'Grady NP, Alexander M, Burns LA, Dellinger EP, Garland J, Heard SO, Lipsett PA, Masur H, Mermel LA, Pearson ML, Raad II, Randolph AG, Rupp ME, Saint S; Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Guidelines for the prevention of intravascular catheter-related infections. Am J Infect Control. 2011;39:S1-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 699] [Cited by in RCA: 745] [Article Influence: 49.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Bull DA, Neumayer LA, Hunter GC, Sethi GK, McIntyre KE, Bernhard VM, Putnam CW. Improved sterile technique diminishes the incidence of positive line cultures in cardiovascular patients. J Surg Res. 1992;52:106-110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Rijnders BJ, Van Wijngaerden E, Wilmer A, Peetermans WE. Use of full sterile barrier precautions during insertion of arterial catheters: a randomized trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:743-748. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Buetti N, Souweine B, Mermel L, Mimoz O, Ruckly S, Loiodice A, Mongardon N, Lucet JC, Parienti JJ, Timsit JF. Concurrent systemic antibiotics at catheter insertion and intravascular catheter-related infection in the ICU: a post hoc analysis using individual data from five large RCTs. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2021;27:1279-1284. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Practice Guidelines for Central Venous Access 2020: An Updated Report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Central Venous Access. Anesthesiology. 2020;132:8-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 162] [Article Influence: 27.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Wittekamp BH, Chalabi M, van Mook WN, Winkens B, Verbon A, Bergmans DC. Catheter-related bloodstream infections: a prospective observational study of central venous and arterial catheters. Scand J Infect Dis. 2013;45:738-745. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Traoré O, Liotier J, Souweine B. Prospective study of arterial and central venous catheter colonization and of arterial- and central venous catheter-related bacteremia in intensive care units. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:1276-1280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Maki DG, Ringer M, Alvarado CJ. Prospective randomised trial of povidone-iodine, alcohol, and chlorhexidine for prevention of infection associated with central venous and arterial catheters. Lancet. 1991;338:339-343. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 648] [Cited by in RCA: 553] [Article Influence: 15.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Schults JA, Reynolds H, Rickard CM, Culwick MD, Mihala G, Alexandrou E, Ullman AJ. Dressings and securement devices to prevent complications for peripheral arterial catheters. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2024;5:CD013023. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Johnson DG, Ito T. Continuous flush of arterial pressure-recording catheters. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1969;57:675-678. [PubMed] |

| 86. | Oh T, Opie NJ, Davis NJ. Continuous flush system for radial artery cannulation. Anaesth Intensive Care. 1976;4:29-32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 87. | Robertson-Malt S, Malt GN, Farquhar V, Greer W. Heparin versus normal saline for patency of arterial lines. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2014:CD007364. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 88. | Eyer S, Brummitt C, Crossley K, Siegel R, Cerra F. Catheter-related sepsis: prospective, randomized study of three methods of long-term catheter maintenance. Crit Care Med. 1990;18:1073-1079. [PubMed] |

| 89. | Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Carlet JM, Bion J, Parker MM, Jaeschke R, Reinhart K, Angus DC, Brun-Buisson C, Beale R, Calandra T, Dhainaut JF, Gerlach H, Harvey M, Marini JJ, Marshall J, Ranieri M, Ramsay G, Sevransky J, Thompson BT, Townsend S, Vender JS, Zimmerman JL, Vincent JL; International Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines Committee; American Association of Critical-Care Nurses; American College of Chest Physicians; American College of Emergency Physicians; Canadian Critical Care Society; European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases; European Society of Intensive Care Medicine; European Respiratory Society; International Sepsis Forum; Japanese Association for Acute Medicine; Japanese Society of Intensive Care Medicine; Society of Critical Care Medicine; Society of Hospital Medicine; Surgical Infection Society; World Federation of Societies of Intensive and Critical Care Medicine. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2008. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:296-327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3537] [Cited by in RCA: 3095] [Article Influence: 171.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 90. | Wang Y, Han L, Xiao Y, Wang F, Yuan C. Appraising the quality of guidelines for peripheral arterial catheters care: A systematic review of reviews. Aust Crit Care. 2023;36:669-675. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 91. | Hixson R, Jensen KS, Melamed KH, Qadir N. Device associated complications in the intensive care unit. BMJ. 2024;386:e077318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 92. | Konrad C, Schüpfer G, Wietlisbach M, Gerber H. Learning manual skills in anesthesiology: Is there a recommended number of cases for anesthetic procedures? Anesth Analg. 1998;86:635-639. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 93. | Varma MK, Price K, Jayakrishnan V, Manickam B, Kessell G. Anaesthetic considerations for interventional neuroradiology. Br J Anaesth. 2007;99:75-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 94. | Troianos CA, Hartman GS, Glas KE, Skubas NJ, Eberhardt RT, Walker JD, Reeves ST; Councils on Intraoperative Echocardiography and Vascular Ultrasound of the American Society of Echocardiography; Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists. Special articles: guidelines for performing ultrasound guided vascular cannulation: recommendations of the American Society of Echocardiography and the Society Of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists. Anesth Analg. 2012;114:46-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 223] [Cited by in RCA: 236] [Article Influence: 16.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 95. | Services Australia, Australian Government. Medicare Item Reports. [cited 5 September 2025]. Available from: https://medicarestatistics.humanservices.gov.au/statistics/mbs_item.html. |

| 96. | Xu R, Nair SK, Materi J, Raj D, Medikonda R, Shah PP, Kannapadi NV, Wang A, Mintz D, Gottschalk A, Antonik LJ, Huang J, Bettegowda C, Lim M. Case Series in the Utility of Invasive Blood Pressure Monitoring in Microvascular Decompression. Oper Neurosurg. 2022;22:262-268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 97. | Nagrebetsky A, Dutton RP, Ehrenfeld JM, Urman RD. Variation in Frequency of Intraoperative Arterial, Central Venous and Pulmonary Artery Catheter Placement During Kidney Transplantation: An Analysis of Invasive Monitoring Trends. J Med Syst. 2018;42:66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 98. | Mahendra M, McQuillen P, Dudley RA, Steurer MA. Variation in Arterial and Central Venous Catheter Use in Pediatric Intensive Care Units. J Intensive Care Med. 2021;36:1250-1257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 99. | Shappell E, Dutta S, Sakaria S, McEvoy DS, Egan DJ. Variability in Emergency Department Procedure Rates and Distributions in a Regional Health System: A Cross-Sectional Observational Study. Ann Emerg Med. 2023;81:624-629. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/