Published online Dec 9, 2025. doi: 10.5492/wjccm.v14.i4.108907

Revised: June 2, 2025

Accepted: August 29, 2025

Published online: December 9, 2025

Processing time: 217 Days and 12 Hours

Previous studies have reported the high predictive accuracy of 4C Mortality Score derived at hospital admission in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) patients. Very few studies have assessed it at intensive care unit (ICU) admission and compared it with the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (A

To describe the characteristics and outcomes of patients admitted to ICU with COVID-19 infection and to compare the accuracy of 4C score and APACHE score in predicting mortality in these patients.

We conducted this retrospective cohort study using an electronic database in a tertiary ICU in Sydney. We included all adult patients (age > 16 years) admitted to ICU with COVID-19 infection over a 5-month period (July 1, 2021 to November 30, 2021). We collected the data on demographics, clinical characteristics, in

A total of 140 patients (62% males, mean age 56 ± 17 years, mean APACHE II score 13 ± 57) were included in the study. Nineteen (13.6%) of 140 patients died in the hospital. Compared to survivors, the non-survivors were older, males, had more comorbidities, higher rate of mechanical ventilation and vasopressor use. The AUROC for the 4C Mortality Score at hospital and ICU admission and APACHE II and II score was 0.75, 0.80. 0.75 and 0.79 re

The 4C score at ICU admission had a higher accuracy in predicting mortality than the 4C score at hospital admission. The predictive accuracy was similar to that for APACHE III score. The 4C score at ICU admission needs to be validated in future studies.

Core Tip: This retrospective cohort study compared the predictive accuracy of the 4c Mortality Score and Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II and III scores for coronavirus disease 2019 patients admitted to intensive care unit (ICU). The 4C score at ICU admission showed an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve of 0.80, higher than at hospital admission (0.75) and comparable to APACHE III (0.79) and II (0.75). Non-survivors were older, predominantly male, with more comorbidities and higher intervention rates. The study suggests that the 4C score at ICU admission is a reliable predictor of mortality and is easier to calculate. These findings warrant further validation in a larger study.

- Citation: Deshpande K, Tripathi D. Predictive accuracy of 4C Mortality Score and Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation scores for mortality in COVID-19 patients admitted to intensive care unit. World J Crit Care Med 2025; 14(4): 108907

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3141/full/v14/i4/108907.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5492/wjccm.v14.i4.108907

The severe acute respiratory syndrome corona virus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic has affected millions of lives since its beginning in December 2019. There have been over 460 million cases and six million deaths so far[1]. The pandemic has been relentless, taking its toll with multiple waves and rapidly changing variants. The health care systems, especially the intensive care units (ICU), all over the world have been under enormous pressure in terms of resource allocation and delivery of medical care.

The prognosis of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) patients is dependent on many variables as is true in any pandemic. The spectrum of disease has varied from asymptomatic or mild symptomatic presentation to life-threatening acute respiratory distress syndrome, multiorgan failure, hyperinflammatory response and thromboembolic phenomena. It is challenging to predict the mortality during any pandemic due to rapidly developing treatments and variability of available resources which alter the outcome over the course of time.

During the peak of pandemic, the 4C (Coronavirus Clinical Characterisation Consortium) mortality score was developed as a part of ongoing International Severe Acute Respiratory and emerging Infection Consortium World Health Organisation Clinical Characterisation Protocol United Kingdom study[2]. It was derived and validated in a very large population cohort in 260 hospitals in United Kingdom. It is an easy to use and valid prediction tool for in-hospital mortality in COVID-19 and categorises patients in low, intermediate, or very high risk of death. The easier availability of all parameters used in 4C score, and earlier calculation as compared to 24-hour timeline for the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) scores makes it an attractive tool to not only predict the course of the disease process earlier but also help in disposition of patients and altering the treatment goals at the very outset.

The routinely used mortality prediction scores like APACHE II and APACHE III, Simplified Acute Physiology Score (SAPS), Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) etc. estimate the mortality risk of ICU population in general and are not specific to one illness. In the early phase of the pandemic, numerous risk stratification tools specific to COVID-19 were developed to support the frontline decision making. There have been around 32 published prognostic scores aimed at predicting mortality risk due to COVID-19 infection. But the limitations with many of the new tools were that they were validated in small samples sizes, had high risk of bias, and lacked formal validation[3].

Several studies have investigated the external validity of the 4C Mortality Score. However, most of these studies have used the score at hospital admission as reported in the original study. Very few studies have used the 4C score at ICU admission[4,5]. Majority of these studies have compared it with standard mortality scores like CURB-65, SOFA, NEWS etc. Though few studies have compared it with APACHE II score[5,6], the studies comparing 4C score with APACHE III score are lacking. Therefore, we decided to compare the 4c Mortality Score at hospital admission with that derived at ICU admission and also compare it with APACHE II and III scores which we collect routinely in all ICU patients. We hypothesised that the predictive accuracy of 4c Mortality Score at ICU admission will be higher than that at hospital admission and APACHE II and III scores.

We conducted this retrospective cohort study in the ICU at St George Hospital, Sydney. The ICU is a 36-bedded tertiary ICU and admits approximately 2700 patients annually.

We included all patients > 16 years of age with a confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19 infection and were admitted to ICU over a five-month period (July 1, 2021 to November 31, 2021). We also included all patients who had initial admission to St George ICU but later were transferred to other hospitals due to lack of beds or the need for ECMO. For patients readmitted to ICU, we included only the first admission in the study. We excluded the patients who were transferred to our ICU from other hospitals and those with incomplete data.

We interrogated our SPRINT-SARI (Short PeRiod IncideNce sTudy of Severe Acute Respiratory Infection) database, eRIC (Electronic record for Intensive Care) and eMR (Electronic Medical record) and extracted following data. Baseline characteristics – age, gender, number of comorbidities (using Charlson Comorbidity Index); Physiological and laboratory parameters – respiratory rate, saturation of partial pressure of oxygen on room air, Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), blood urea nitrogen, C-reactive protein; Severity of illness scores: APACHE II, APACHE III; Process measures: Respiratory support (O2via high flow nasal prongs, noninvasive ventilation, invasive mechanical ventilation, prone positioning, use of vasopressors and continuous renal replacement therapy); COVID-19 specific medications; Outcome measures: Duration of mechanical ventilation, ICU and hospital length of stay, hospital mortality; The primary outcome of the study was hospital mortality.

We calculated the 4C Mortality Score using the method described by Knight et al[2]. The variables used in the calculation are age, gender, number of comorbidities, respiratory rate, oxygen saturation on room air, Glasgow coma scale, Urea (mmol/L) and CRP (mg/L). We measured these variables at the time of hospital admission and ICU admission. The 4C score ranges from 0 to 21 with risk groups defined as Low (0-3), Intermediate (4-8), High (9-14), and very high (≥ 15). The components of 4C Mortality Score are shown in Table 1.

| Variable | 4C Mortality Score |

| Age (years) | |

| < 50 | - |

| 50-59 | +2 |

| 60-69 | +4 |

| 70-79 | +6 |

| ≥ 80 | +7 |

| Sex at birth | |

| Female | - |

| Male | +1 |

| 1Number of comorbidities | |

| 0 | 0 |

| 1 | +1 |

| ≥ 2 | +2 |

| Respiratory rate (breaths/minute) | |

| < 20 | - |

| 20-29 | +1 |

| ≥ 30 | +2 |

| Peripheral oxygen saturation on room air (%) | |

| ≥ 92 | - |

| < 92 | +2 |

| Glasgow coma scale score | |

| 15 | - |

| < 15 | +2 |

| Urea (mmol/L) | |

| < 7 | - |

| 7-14 | +1 |

| > 14 | +3 |

| C reactive protein (mg/L) | |

| < 50 | - |

| 50-99 | +1 |

| ≥ 100 | +2 |

As the 4C score has been validated for hospital admission only in the original study, it was difficult to obtain true values of certain variables such as oxygen saturation, GCS and respiratory rate for the patients who were endotracheally intubated in the Emergency Department or on the hospital wards before transfer to ICU. As these patients were transferred immediately to ICU after intubation, we collected their oxygen saturation, GCS, and respiratory rate just before intubation and used them as ICU admission values. We collected APACHE II and APACHE III scores at 24 hours of admission to ICU from the ICU electronic data base. The scores were automatically calculated in the eRIC.

We analysed the continuous variables using mean ± SD or median (IQR) and the categorical variables as numbers and percentages (%). To compare the distribution of characteristics and outcomes for survivors and non-survivors, we used χ2 test or Fisher exact test for categorical variables and independent-samples t-test or the non-parametric Wilcoxon Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables. We derived the predictive accuracy of 4C Mortality Score at hospital admission and ICU admission and APACHE II and III scores by the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC). We calculated the optimal cut-off value and the 95% confidence (CI) interval for each of these scores using the ‘nearest[0,1]’ method and bootstrapping. All analyses were performed using Stata[7].

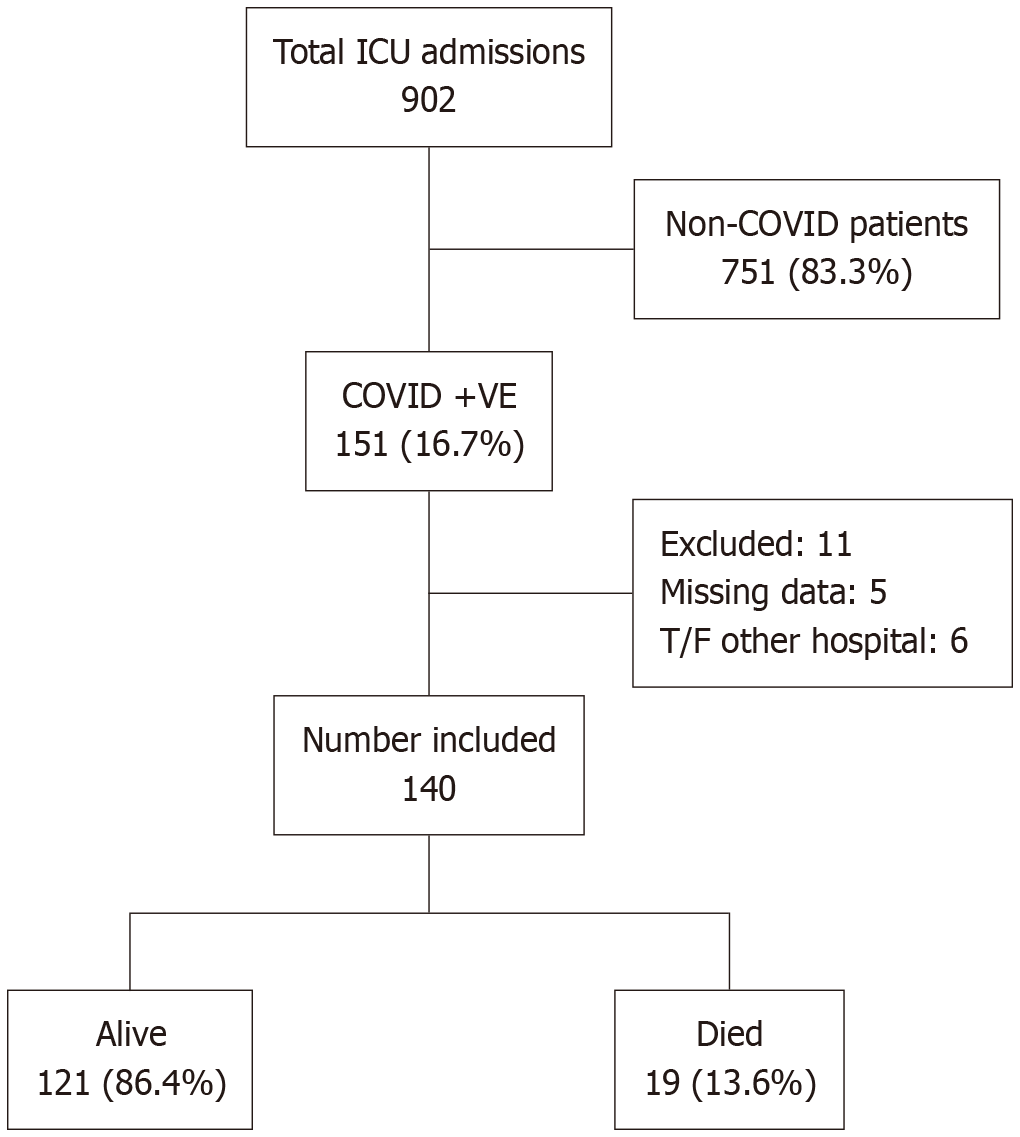

Of the 902 total ICU admissions during the study period, 151 (16.7%) patients had a confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19. A total of 140 patients had complete data and were included in the study. The participant flow chart is shown in Figure 1.

The baseline characteristics of all patients stratified by hospital outcome is shown in Table 2. The mean age was 55.67 ± 16.8 years, and 62% patients were males. The mean APACHE II score was 12.9 ± 5.4. Sixty percent of our patients were proned, 36% underwent invasive mechanical ventilation and vasopressors were used in 30.7% of patients. Overall, 19 (13.6%) patients died during the hospital admission. Compared to survivors, the non-survivors were older, males, had more comorbidities, higher rate of mechanical ventilation and vasopressor use. The median ICU length of stay was higher in non-survivors compared to survivors (13 days vs 5 days).

| All patients, n = 140 | Alive, n = 121 | Died, n = 19 | P value | |

| Age, years (mean ± SD) | 55.6 ± 16.8 | 53.3 ± 16.6 | 70.1 ± 9.6 | < 0.001 |

| Sex | 0.03 | |||

| Male | 87 (62.1) | 71 (81.6) | 16 (18.4) | |

| Female | 53 (37.9) | 50 (94.3) | 3 (5.7) | |

| No of comorbidities | 0.03 | |||

| 0 | 62 (44.3) | 59 (95.2) | 3 (4.8) | |

| 1 | 41 (29.3) | 33 (80.5) | 8 (19.5) | |

| ≥ 2 | 37 (26.4) | 29 (78.4) | 8 (21.6) | |

| Process measures | ||||

| Prone positioning | 0.57 | |||

| No | 58 (41.4) | 49 (85.5) | 9 (15.5) | |

| Yes | 82 (58.6) | 72 (87.8) | 10 (12.2) | |

| Mechanical ventilation | 0.009 | |||

| No | 89 (63.6) | 82 (92.1) | 7 (7.9) | |

| Yes | 51 (36.4) | 39 (76.5) | 12 (23.5) | |

| NIV + HFNP | 0.15 | |||

| No | 50 (35.7) | 46 (92.0) | 4 (8.0) | |

| Yes | 90 (64.3) | 75 (83.3) | 15 (16.7) | |

| Vasopressors | 0.03 | |||

| No | 97 (69.3) | 88 (90.7) | 9 (9.3) | |

| Yes | 43 (30.7) | 33 (76.7) | 10 (23.3) | |

| CRRT | 0.69 | |||

| No | 138 (98.6) | 120 (87.0) | 18 (13.0) | |

| Yes | 2 (1.4) | 1 (50.0) | 1 (50.0) | |

| COVID specific treatment | ||||

| Antiviral agents | 0.57 | |||

| No | 58 (41.4) | 49 (84.5) | 9 (15.5) | |

| Yes | 82 (58.6) | 72 (87.8) | 10 (12.2) | |

| Monoclonal antibodies | 0.16 | |||

| No | 109 (77.9) | 91 (83.5) | 18 (16.5) | |

| Tocilizumab | 30 (21.4) | 29 (96.7) | 1 (3.3) | |

| Sotrovimab | 1 (0.7) | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | |

| Baricitinib | 0.53 | |||

| No | 97 (69.3) | 85 (87.6) | 12 (12.4) | |

| yes | 43 (30.7) | 36 (83.7) | 7 (16.3) | |

| Length of stay, days | ||||

| ICU, median and [IQR] | 5.9 [3.2-12.8] | 5 [2.8-11.2] | 13 [9.8-18.3] | 0.004 |

| Hospital, median and [IQR] | 13.2 [7.7-22.6] | 11.9 [7.3-21.9] | 18.4 [14.1-22.3] | 0.09 |

The physiological and laboratory components of 4C Mortality Score are shown in Table 3. There was statistically significant difference in the mean Urea levels in those who survived and those who did not (6.8 mmol/L vs 9.6 mmol/L, P = 0.01). Other parameters were similar in the two groups. Compared to survivors, the average values of all 4 predictive scores were higher in non-survivors (Table 4).

| All patients, n = 140 | Alive, n = 121 | Died, n = 19 | P value | |

| At hospital admission | ||||

| Respiratory rate (breath/minute) | 28.8 ± 9.8 | 29.4 ± 10.2 | 25.4 ± 6.1 | 0.10 |

| Peripheral oxygen saturation on room air (%) | 92.6 ± 7.3 | 92.2 ± 7.7 | 94.8 ± 2.7 | 0.14 |

| Glasgow coma scale score | 14.7 ± 1.1 | 14.7 ± 1.2 | 14.6 ± 0.8 | 0.55 |

| Urea (mmol/L) | 6.8 ± 5.0 | 6.4 ± 4.5 | 8.9 ± 7.4 | 0.048 |

| C reactive protein (mg/L) [IQR] | 75 [41-121] | 74 [40-125] | 89 [42-107] | 0.81 |

| At ICU admission | ||||

| Respiratory rate (breath/minute) | 28.1 ± 9.5 | 28.2 ± 9.5 | 26.9 ± 9.3 | 0.56 |

| Peripheral oxygen saturation on room air (%) | 93.4 ± 3.9 | 93.5 ± 4.1 | 93.2 ± 2.8 | 0.75 |

| Glasgow coma scale score | 12.9 ± 4.3 | 12.9 ± 4.4 | 13.3 ± 3.8 | 0.72 |

| Urea (mmol/L) | 7.2 ± 4.4 | 6.8 ± 4.1 | 9.6 ± 5.4 | 0.01 |

| C reactive protein (mg/L) [IQR] | 75 [33-125] | 64 [31-124] | 100 [71-134] | 0.09 |

| All patients, n = 140 | Alive, n = 121 | Died, n = 19 | P value | |

| Mortality prediction scores | ||||

| 4C Mortality Score at hospital admission | 7.6 ± 4.2 | 7.2 ± 4.2 | 10.6 ± 2.7 | < 0.001 |

| 4C Mortality Score at ICU admission | 8.4 ± 4.2 | 7.8 ± 4.1 | 12.1 ± 2.6 | < 0.0001 |

| APACHE II | 12.9 ± 5.4 | 12.3 ± 5.3 | 16.9 ± 4.5 | 0.0004 |

| APACHE III | 50.7 ± 18.0 | 48.1 ± 16.7 | 67.2 ± 17.5 | < 0.0001 |

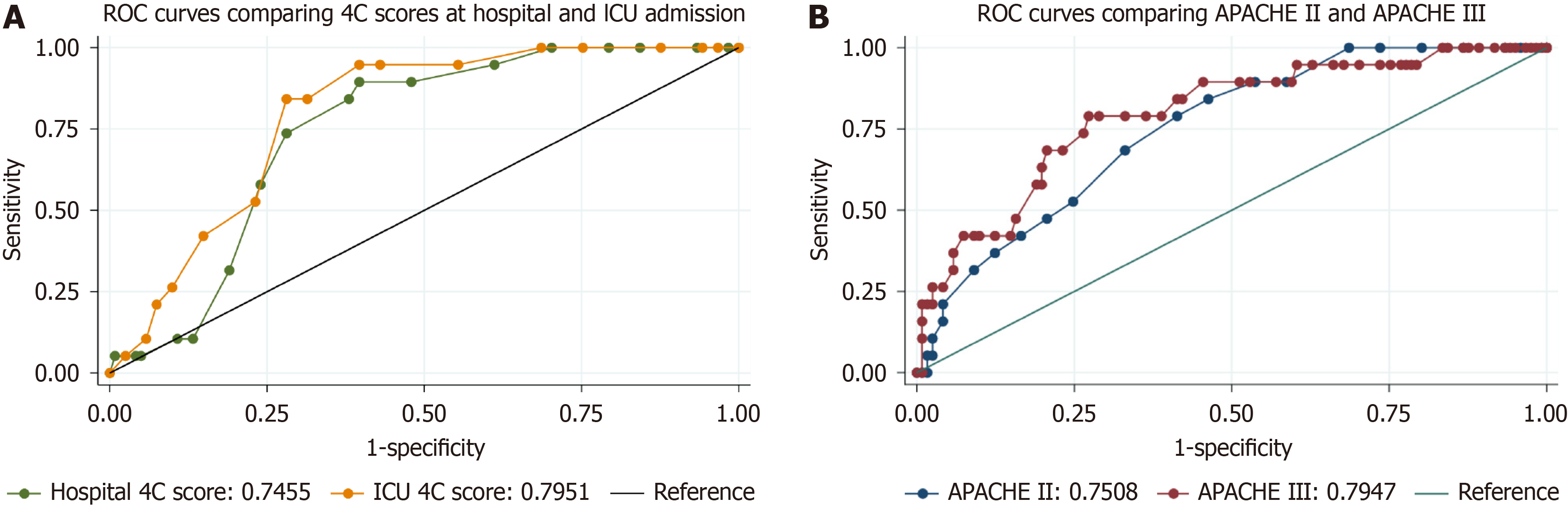

The predictive accuracy of all 4 scores and their cut-off value is shown in Tables 5 and 6. The ROC curves are shown in Figure 2. The AUROC for the 4C Mortality Score at hospital and ICU admission and APACHE II and II score was 0.75, 0.80. 0.75 and 0.79 respectively. The optimal cut-off value for these four scores was 9, 10, 14 and 56 respectively. The cut-off value for all the scores had higher sensitivity than specificity. The cut-off value for 4C score at ICU admission had highest AUROC and achieved optimal balance between sensitivity and specificity.

| AUROC | 95%CI | |

| 4C Mortality Score at hospital admission | 0.75 | 0.65-0.84 |

| 4C Mortality Score at ICU admission | 0.80 | 0.71-0.88 |

| APACHE II | 0.75 | 0.65-0.85 |

| APACHE III | 0.79 | 0.69-0.90 |

| Cut-off value | Sensitivity | Specificity | AUROC | 95%CI for cut-off value | |

| Hospital 4C mortality | 9 | 0.74 | 0.72 | 0.73 | 7.2-10.8 |

| ICU 4C mortality | 10 | 0.84 | 0.72 | 0.78 | 8.9-11.1 |

| APACHE II | 14 | 0.68 | 0.67 | 0.68 | 11.8-16.2 |

| APACHE III | 56 | 0.79 | 0.73 | 0.76 | 52.0-60.0 |

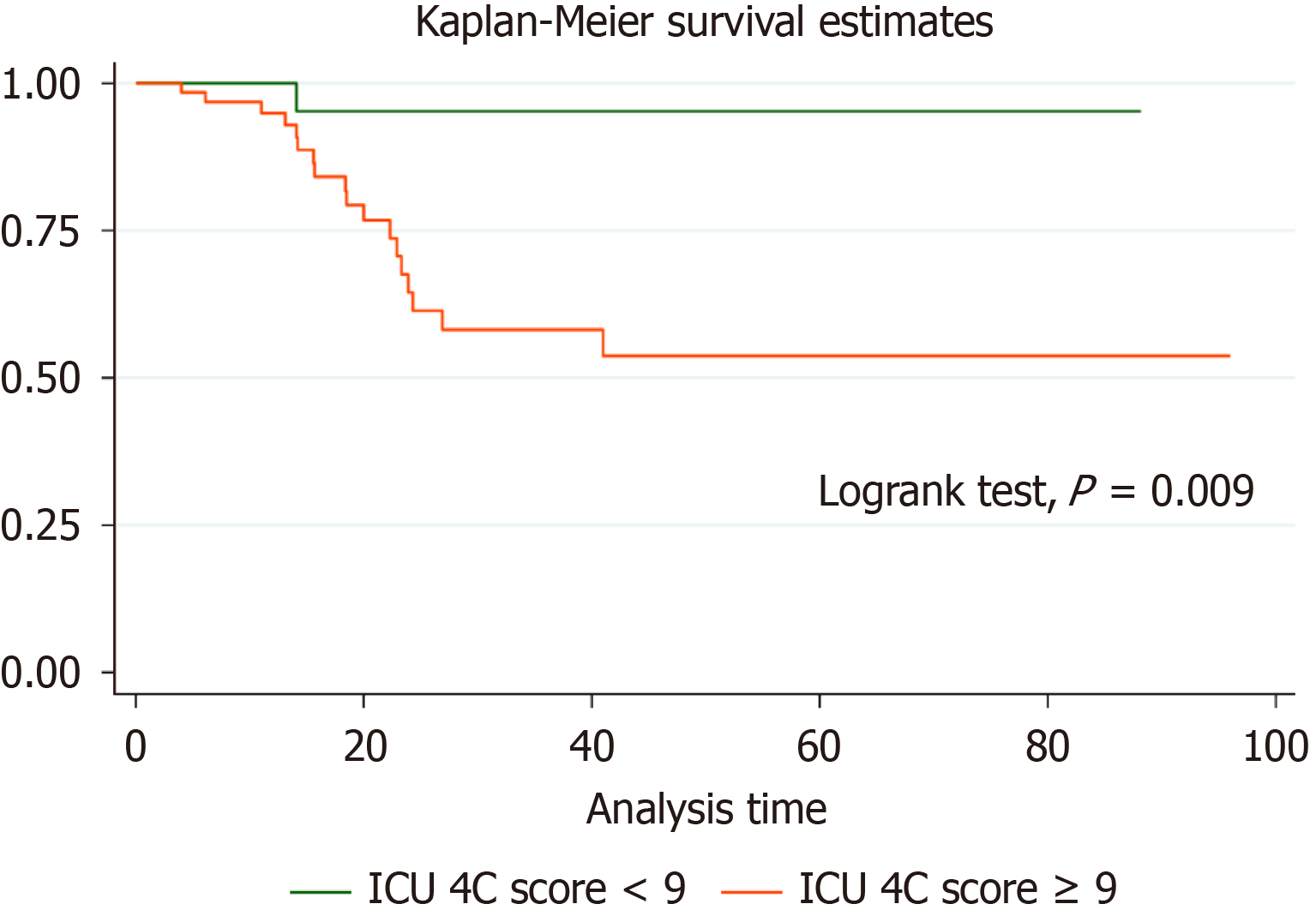

The mortality rates across ICU 4C score risk groups is shown in Table 7. Eighteen of 19 (95%) deaths were in the top two risk categories (score ≥ 9) and only 1 patient died in the group with the score < 9. This difference in survival was statistically significant (log rank P = 0.009) as shown in Figure 3.

| Risk groups | Total, n = 140 | Alive, n = 121 | Died, n = 19 |

| Low (0-3) | 15 | 15 | 0 |

| Intermediate (4-8) | 59 | 58 | 1 (1.7) |

| High (9-15) | 57 | 41 | 16 (28.1) |

| Very high (16-21) | 9 | 7 | 2 (22.2) |

In this retrospective cohort study, the accuracy of 4C score at ICU admission for predicting hospital mortality was similar to that for APACHE III score. It was higher than the predictive accuracy of 4C score at hospital admission and APACHE II. All four predictor scores at ICU admission were higher in non-survivors compared to survivors. The mortality was 95% in the high and very high-risk groups (score ≥ 9). These results have a potential to inform the decision making around timely escalation of therapy and admission location (ICU vs hospital ward). The score is easy to calculate and available within a few hours of admission and have a good predictive accuracy for hospital mortality in COVID-19 patients admitted to ICU.

Table 8 shows the comparison with similar studies that have been done in various countries since the onset of the pandemic[2-6,8-13]. They were done mainly for external validation of 4C score and to compare it with other predictive scores used routinely in the hospital or ICU setting. In all these studies 4C score had good predictive accuracy and consistently performed better when compared with other scores. All studies except one are retrospective with the sample size ranging from 53 to over 22000 patients. The mortality also varies widely from 6.1% to 41.4%. Most of these studies have measured the 4C score at hospital admission. The predictive accuracy measured by AUROC ranged from 0.75 to 0.90.

| Ref. | Study design | Sample size | Mortality% | 4C Mortality Score calculated at | Comparison | AUROC1 | 95%CI |

| Knight et al[2], United Kingdom | Multicenter prospective observational | 22361 | 30.9 | Hospital admission | Derivation and validation | 0.77 | 0.76-0.77 |

| Covino et al[12], Italy | Single centre retrospective | 210 | 20 | Hospital admission | COVID-GRAM, qCSI, NEWS | 0.79 | 0.73-0.85 |

| Wellbelove et al[10], United Kingdom | Exploratory analysis | 53 | 11 | Hospital admission | CURB-65, CRB-65, qSOFA, NEWS | 0.83 | 0.71-0.95 |

| Kuroda et al[11], Japan | Multicenter retrospective | 693 | 34.4 | Hospital admission | RISE-UP, A-DROP, REMS | 0.84 | 0.80-0.88 |

| Jones et al[13], Canada | Multicenter retrospective | 959 | 23 | Hospital admission | 4C score in wave1, 2 and 3 | 0.77 | 0.74-0.80 |

| Lombardi et al[3], France | Multicenter retrospective | 14343 | 35.3 | Hospital admission | 32 scores | 0.78 | 0.77-0.79 |

| Vicka et al[6], Lithuania | Single centre retrospective | 249 | 41.4 | Hospital admission | APACHE II, SOFA, SAPS | 0.75 | 0.69-0.81 |

| Mohammad et al[8], Saudi Arabia | Multicenter retrospective | 506 | 6.1 | Hospital admission | External validation | 0.90 | 0.85-0.95 |

| Durie et al[5], Australia | Multicenter prospective observational | 1492 | 13.2 | ICU admission | APACHE II | 0.79 | 0.68-0.90 |

| Altreby et al[4], Saudi Arabia | Single centre retrospective | 1493 | 37.9 | ICU admission | External validation | 0.81 | 0.79-0.83 |

| Ocho et al[9], Japan | Multicenter retrospective | 206 | 10.1 | Hospital admission | A-DROP, CURB-65, SOFA | 0.84 | 0.76-0.92 |

| Our study | Single centre retrospective | 140 | 13.6 | Hospital admission, | APACHE II, | 0.75, | 0.65-0.84, |

Of the 11 studies shown in the Table 8, only 2 studies (Aletreby et al[4] and Durie et al[5]) have calculated the 4C Mortality Score at ICU admission and only one study by Durie et al has compared it to APACHE II score. None of the studies have compared the 4C Mortality Score to APACHE III score. Altreby et al[4] have performed external validation of 4C Mortality Score and have not compared it with any other scores. Table 8 also shows different study populations as ‘country’ of study. The majority of studies are multicentre and retrospective. None of the studies have described treatment protocols. All these studies are ‘predictive’ studies and have evaluated the primary outcome by fitting the ROC curve.

A large multicentre cohort study was done in the Greater Paris university hospitals in approximately 14000 patients where they compared the predictive accuracy of 4C score at hospital admission with 31 other scores. The 4C score was found to have good external validity across all waves and all age groups[3].

The highest AUROC of 0.90 was found in a retrospective multicentre (two hospitals) study in Saudi Arabia by Mohamed et al[8]. The mortality rate was correctly estimated by their model with 71% sensitivity, 88.6% specificity though they had the lowest mortality (6.1%) of all the studies listed in Table 8.

Ocho et al[9] compared 4C score with qSOFA, A-DROP and CRUB-65 in a multicentre retrospective observational study in Japan to predict mortality and found that 4C score had good predictive accuracy [area under the curve (AUC): 0.84, 95%CI: 0.76-0.92] which was also much higher than the other scores (qSOFA: 0.66, 95%CI: 0.53-0.78, CURB-65: 0.82, 95%CI: 0.74-0.90, A-DROP: 0.78, 95%CI: 0.69-0.88).

Wellbelove et al[10] compared the 4C score with CURB-65, CRB-65 and qSOFA in a variety of respiratory infection cohorts, including COVID-19 infection in an exploratory analysis and found that 4C Mortality Score had the greatest AUC in COVID-19, community acquired pneumonia and Interstitial pulmonary disease patients and similar to Influenza cohort.

Kuroda et al[11] used the 4C score to predict in-hospital mortality for patients with COVID-19 and pre-existing cardiovascular disease or risk factors in a retrospective cohort study and compared it with RISE-UP, A-DROP and REMS scores. The patients were selected from the Japanese nationwide registry. They found that 4C score performed well in this cohort and hence may help in allocation of medical resources as well as disposition of the patients.

Covino et al[12] in their study of older patients (age 60-98 years) with COVID -19 have also found the best discrimination for 4C score at hospital admission (AUROC, 0.80) followed by COVID-GRAM (0.79), NEWS (0.76) and qCSI (0.75).

APACHE II was shown to have better discrimination in two studies. Durie et al[5] in their multicentre prospective observational cohort study compared the 4C score at ICU admission and compared it with APACHE II score. They had complete data only for 149 out of 461 patients under study. The predictive accuracy of 4C score was not superior to APACHE II score (AUROC of 0.79 and 0.81 respectively). Vicka et al[6] compared the predictive accuracy of 4C score at hospital admission with APACHE II, SOFA and SAPS in patients admitted with COVID-19 infection. They found the APACHE II score had the best discrimination (AUROC: 0.77) for predicting mortality compared to other scores. These results are contradictory to our findings.

Asmarawati et al[14], in their prospective cohort study of 53 patients with moderate-to-severe COVID-19 found that qSOFA, SOFA, APACHE II, and NEWS-2 scores on day 5 had good predictive values for mortality. APACHE-II score was best at predicting mortality and ICU admission rate. There was no comparison with 4C Mortality Score. The accom

Compared to the previous studies, the results of our study are slightly different. The predictive accuracy of 4C score at hospital admission (AUROC of 0.75) was less than that reported in these studies. The discriminating ability of APACHE II was lower than APACHE III. There were no studies to compare the predictive accuracy of APACHE III score (AUROC of 0.80) in our study.

Our study has several strengths. This is the first study to our knowledge comparing the 4C score with the routinely used APACHE III score in ICU. Our data were accurate and complete as we verified individual patient data manually and cross-checked it with eMR and eRIC. We did robust statistical analysis and used modern statistical methods such as machine learning to derive important variables in predicting mortality. Therefore, the study has excellent interval validity.

There are several limitations to our study. This was a single centre, retrospective study with a small sample size and low event rate (13.6%). The low mortaltiy in our study is consistent with that reported in the Australian setting. The study population included patients from the third wave only and although we presume from our study period that they were all delta variants, the actual COVID-19 variant and the genomic type were unknown. As the mortality in our study was low compared to some of the other studies, the results may not be applicable to those settings with high mortality. Therefore, the study has limited generalisability.

The 4C Mortality Score has been validated for use at the time of hospital admission. Its use at the time of ICU admission needs to be validated in large multicentre studies. The future studies should also test its applicability to various COVID-19 variants which have rapidly emerged over the course of the pandemic. Future studies should report the subgroup analysis looking at various subgroups such as elderly, vaccinated, immunocompromised patients, different variants of COVID-19 and specific treatments/interventions used. The studies should also look at trends in 4C score as they may be more informative. The outcome of the disease has changed concurrent with the rapid discovery of new therapies, vaccines and development of herd immunity. Therefore, the 4C score would also need revaluation and recalibration in future to keep pace with these changes. Modern technics such as machine learning methods may be useful for selection of new variables in the recalibrated model.

The 4C score at ICU admission had a higher accuracy in predicting mortality than the 4C score at hospital admission. The predictive accuracy was similar to that for APACHE III score. The 4C score at ICU admission needs to be validated in large multicentre studies.

We thank Warren Eather (ICU Data Manager), Garnett Fuller and Deborah Inskip (ICU Research Coordinators) and all ICU staff for their support.

| 1. | World Health Organization. WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. [cited 19 March 2022]. Available from: https://data.who.int/dashboards/covid19/data. |

| 2. | Knight SR, Ho A, Pius R, Buchan I, Carson G, Drake TM, Dunning J, Fairfield CJ, Gamble C, Green CA, Gupta R, Halpin S, Hardwick HE, Holden KA, Horby PW, Jackson C, Mclean KA, Merson L, Nguyen-Van-Tam JS, Norman L, Noursadeghi M, Olliaro PL, Pritchard MG, Russell CD, Shaw CA, Sheikh A, Solomon T, Sudlow C, Swann OV, Turtle LC, Openshaw PJ, Baillie JK, Semple MG, Docherty AB, Harrison EM; ISARIC4C investigators. Risk stratification of patients admitted to hospital with covid-19 using the ISARIC WHO Clinical Characterisation Protocol: development and validation of the 4C Mortality Score. BMJ. 2020;370:m3339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 619] [Cited by in RCA: 682] [Article Influence: 113.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Lombardi Y, Azoyan L, Szychowiak P, Bellamine A, Lemaitre G, Bernaux M, Daniel C, Leblanc J, Riller Q, Steichen O; AP-HP/Universities/INSERM COVID-19 Research Collaboration AP-HP COVID CDR Initiative. External validation of prognostic scores for COVID-19: a multicenter cohort study of patients hospitalized in Greater Paris University Hospitals. Intensive Care Med. 2021;47:1426-1439. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Aletreby WT, Mumtaz SA, Shahzad SA, Ahmed I, Alodat MA, Gharba M, Farea ZA, Mady AF, Mahmood W, Mhawish H, Abdulmowla MM, Nasser RM. External Validation of 4C ISARIC Mortality Score in Critically ill COVID-19 Patients from Saudi Arabia. Saudi J Med Med Sci. 2022;10:19-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Durie ML, Neto AS, Burrell AJC, Cooper DJ, Udy AA; SPRINT-SARI Australia Investigators. ISARIC-4C Mortality Score overestimates risk of death due to COVID-19 in Australian ICU patients: a validation cohort study. Crit Care Resusc. 2021;23:403-413. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Vicka V, Januskeviciute E, Miskinyte S, Ringaitiene D, Serpytis M, Klimasauskas A, Jancoriene L, Sipylaite J. Comparison of mortality risk evaluation tools efficacy in critically ill COVID-19 patients. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21:1173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 17. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC. 2021. [cited 23 August 2025]. Available from: https://www.stata.com. |

| 8. | Mohamed RAE, Abdelsalam EM, Maghraby HM, Al Jedaani HS, Rakha EB, Hussain K, Sultan I. Performance features and mortality prediction of the 4C Score early in COVID-19 infection: a retrospective study in Saudi Arabia. J Investig Med. 2022;70:421-427. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ocho K, Hagiya H, Hasegawa K, Fujita K, Otsuka F. Clinical Utility of 4C Mortality Scores among Japanese COVID-19 Patients: A Multicenter Study. J Clin Med. 2022;11:821. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Wellbelove Z, Walsh C, Perinpanathan T, Lillie P, Barlow G. Comparing the 4C mortality score for COVID-19 to established scores (CURB65, CRB65, qSOFA, NEWS) for respiratory infection patients. J Infect. 2021;82:414-451. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kuroda S, Matsumoto S, Sano T, Kitai T, Yonetsu T, Kohsaka S, Torii S, Kishi T, Komuro I, Hirata KI, Node K, Matsue Y. External validation of the 4C Mortality Score for patients with COVID-19 and pre-existing cardiovascular diseases/risk factors. BMJ Open. 2021;11:e052708. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Covino M, De Matteis G, Burzo ML, Russo A, Forte E, Carnicelli A, Piccioni A, Simeoni B, Gasbarrini A, Franceschi F, Sandroni C; GEMELLI AGAINST COVID-19 Group. Predicting In-Hospital Mortality in COVID-19 Older Patients with Specifically Developed Scores. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69:37-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 12.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Jones A, Pitre T, Junek M, Kapralik J, Patel R, Feng E, Dawson L, Tsang JLY, Duong M, Ho T, Beauchamp MK, Costa AP, Kruisselbrink R; COREG Investigators. External validation of the 4C mortality score among COVID-19 patients admitted to hospital in Ontario, Canada: a retrospective study. Sci Rep. 2021;11:18638. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Asmarawati TP, Suryantoro SD, Rosyid AN, Marfiani E, Windradi C, Mahdi BA, Sutanto H. Predictive Value of Sequential Organ Failure Assessment, Quick Sequential Organ Failure Assessment, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II, and New Early Warning Signs Scores Estimate Mortality of COVID-19 Patients Requiring Intensive Care Unit. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2022;26:464-471. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Siddiqui SS, Patnaik R, Kulkarni AP. General Severity of Illness Scoring Systems and COVID-19 Mortality Predictions: Is "Old Still Gold?". Indian J Crit Care Med. 2022;26:416-418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/