INTRODUCTION

Sepsis is a life-threatening condition with a substantial worldwide burden of disease. According to the Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3), sepsis has been defined as a “life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated immune response to infection”[1]. Sepsis results in widespread inflammation, tissue injury, and multi-organ dysfunction. Globally, sepsis affects 48.9 million people and is attributed to 11 million deaths in 2020, accounting for 20% of all deaths[2]. Sepsis is a complex dysregulation of the host immune response, characterised by an imbalance between pro- and anti-inflammatory mechanisms. This dysregulation triggers a systemic release of cytokines, mediators and pathogen-related molecules, subsequently activating the coagulation and complement cascades[3]. In 2002, the Society of Critical Care Medicine, the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine, and the International Sepsis Forum (ISF) launched the Surviving Sepsis Campaign to enhance global sepsis management through evidence-based guidelines and collaborative efforts[4]. By 2010, hospital mortality had decreased to 30.8%[5]. Despite advancements in diagnostic modalities and supportive therapies, sepsis remains associated with high mortality and long-term, highlighting the need for novel insights into its complex pathophysiology. A hallmark feature of sepsis is its systemic inflammatory response, which disrupts homeostasis and lead to multi-organ dysfunction, including the liver, lungs, kidneys, heart, and brain[6]. This dysfunction is primarily driven by a dysregulated immune response, resulting in widespread inflammation, endothelial injury and impaired perfusion, ultimately precipitating organ failure due to hypoxia[7] and, in severe cases, death.

Recent research underscores the gut microbiota’s critical role in regulating immune responses and maintaining systemic homeostasis[8]. However, its contribution to sepsis progression and associated organ dysfunction remains insufficiently explored. While dysbiosis is linked to intestinal barrier disruption, systemic inflammation, and multi-organ dysfunction, the specific interactions between gut microbiota and sepsis-associated organ dysfunction are inadequately understood and uncommonly compiled in a single scientific report. This scholarly work addresses the gap.

ROLE OF GUT

This review aims to synthesize current evidence on the organ-gastrointestinal tract axis in sepsis, with a focus on understanding the bidirectional relationships between gut dysbiosis and the dysfunction of major organ systems. By examining the gut-liver, gut-lung, gut-kidney, gut-brain, and gut-heart axes, this review highlights the systemic implications of gut microbiota in sepsis pathophysiology[9] through the induction, training and function of the host immune system as the immune system has predominantly evolved to preserve the symbiotic relationship between the host and its diverse, evolving microbial communities[10]. Furthermore, it explores emerging therapeutic strategies targeting the gut microbiota to improve sepsis outcomes[11]. By addressing these critical issues, this review addresses existing research gaps by consolidating the effect of sepsis on the various organ-gut axes. By consolidating these effects, this review provides a foundation for future research and innovations into the various therapies for sepsis management.

LITERATURE SEARCH

A comprehensive literature search was done on PubMed and Cochrane library from inception to July 2024 using the following keywords: “Sepsis”, “SIRS”, “systemic inflammatory response syndrome”. Additional keywords related to the specific axes were used: “Intestines”, “gastrointestinal microbiome”, “dysbiosis”, “colon”, “heart, “spleen”, “brain-gut axis”, “gut-brain axis”, “sepsis-associated encephalopathy”, “lung-gut axis”, “acute lung injury”, “acute respiratory distress syndrome”, “ARDS”, “liver-gut axis”, “pancreas-gut axis”. More details of the search strategy could be found in the appendix.

SEPSIS PATHOPHYSIOLOGY AND SYSTEMIC IMPACTS

Sepsis is triggered by dysregulated host response to infection, leading to systemic inflammation, tissue damage, and organ dysfunction[12,13]. The pathogenesis of sepsis begins with recognition of pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) from infectious agents or damage-associated molecular patterns released by injured host tissues[14]. These molecules activate pattern recognition receptors, like Toll-like receptors, on immune cells. This activation triggers an inflammatory cascade characterized by the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, which coordinate efforts to contain the infection and facilitate tissue repair[15,16].

In sepsis, this immune response becomes unregulated, causing widespread inflammation that extends beyond the initial site of infection. The resulting SIRS drives endothelial activation, vascular leakage, and microvascular thrombosis, which disrupt tissue perfusion and leads to cellular hypoxia. As sepsis progresses, an imbalance between pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory mediators results in immune exhaustion, impairing the host’s ability to clear infections and increasing the risk of secondary infections. This cycle of inflammation and immune dysfunction culminates in multi-organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS), characterized by failure of vital organ systems such as the lungs, kidneys, liver, brain, and heart. The clinical manifestations of MODS, including acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), acute kidney injury (AKI), hepatic failure, and sepsis-associated encephalopathy (SAE), contribute significantly to the high mortality associated with sepsis[6].

A key driver of sepsis is the cytokine storm, an overproduction of inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and IL-1β. These cytokines amplify the inflammatory response and induce endothelial injury, capillary leakage, and coagulation abnormalities[17]. The uncontrolled release of reactive oxygen species during this process exacerbates tissue damage through oxidative stress, impairing mitochondrial function and triggering apoptosis. Additionally, immune activation pathways, including nuclear factor kappa B and inflammasomes, orchestrate the production of pro-inflammatory mediators, while dysregulated complement and coagulation systems contribute to microvascular thrombosis and tissue ischemia. The breakdown of the endothelial barrier further aggravates vascular leakage and edema, perpetuating the cycle of inflammation and organ damage[18].

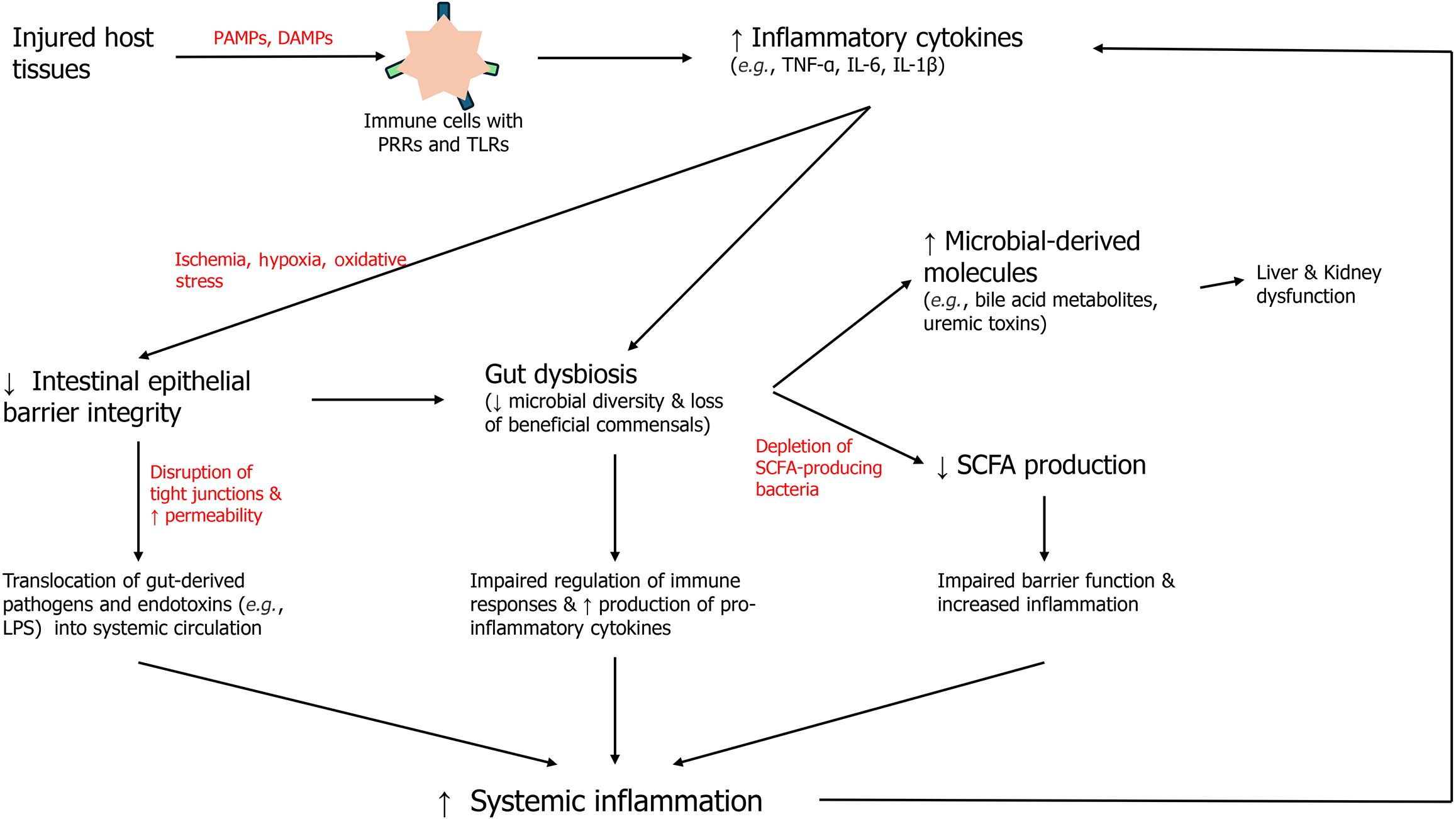

The gastrointestinal tract plays a pivotal role in the progression of sepsis, serving as both a target and a source of systemic inflammation. Intestinal epithelial barrier integrity is compromised by ischemia, hypoxia, and oxidative stress, which lead to the disruption of tight junctions and increased permeability. This allows translocation of gut-derived pathogens and their endotoxins, such as lipopolysaccharides (LPS), into the systemic circulation[19]. These groups of microbial communities or microbial synthesized metabolites act as potent activators of the immune system, triggering widespread cytokine release and systemic inflammation.

Gut-origin sepsis is further exacerbated by dysbiosis, a disruption of the gut microbiota characterized by a loss of commensal bacteria and overgrowth of pathogenic species. Dysbiosis not only impairs the gut’s ability to maintain homeostasis but also amplifies systemic inflammation through the production of metabolites[20]. The resulting immune activation creates a feedback loop, where systemic inflammation further damages the intestinal barrier, perpetuating microbial translocation and inflammation. This gut-driven immune dysregulation significantly contributes to the progression of sepsis and the development of MODS[21].

The gut microbiota plays a pivotal role in maintaining immune modulation, homeostasis, and metabolic functions (Figure 1). Under normal conditions, a healthy gut microbiota supports the host's immune system by promoting tolerance to commensal organisms while effectively responding to pathogens. It achieves this balance through direct interactions with gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT), production of anti-inflammatory metabolites, and regulation of epithelial barrier integrity. Moreover, gut microbiota contributes to essential metabolic processes, including the synthesis of vitamins, the fermentation of dietary fibers into short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), and the detoxification of harmful substances[22]. This symbiotic relationship between the host and its gut microbiota is integral to overall health.

Figure 1 Interplay between disrupted gut barrier integrity, microbial translocation, reduced short chain fatty acid production, and the resulting pro-inflammatory cascade that exacerbates multi-organ dysfunction through microbial-derived metabolites and cytokine release.

SCFA: Short chain fatty acid; PAMPs: Pathogen-associated molecular patterns; DAMPs: Damage-associated molecular patterns; TNF-α: Tumor necrosis factor-alpha; IL: Interleukin; LPS: Lipopolysaccharides.

During sepsis, however, this balance is disrupted, leading to a state of dysbiosis. Dysbiosis is a hallmark feature of sepsis pathophysiology. Studies have shown that sepsis is associated with a reduction in microbial diversity, characterized by loss of beneficial commensal bacteria such as Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes and the overgrowth of pathogenic species like Proteobacteria[20]. This microbial imbalance contributes to systemic inflammation by impairing the gut’s ability to regulate immune responses and by enhancing the production of pro-inflammatory mediators. Dysbiosis is further compounded by gut barrier dysfunction, a common feature in sepsis. The integrity of the intestinal epithelial barrier, which relies on tight junction proteins and mucus layers, is compromised during sepsis due to ischemia, hypoxia, and oxidative stress[23]. This disruption allows microbial translocation, where gut-derived bacteria and their products, including LPS, enter the systemic circulation. LPS, a potent endotoxin derived from Gram-negative bacteria, activates Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) signalling, triggering a cascade of systemic inflammatory responses that exacerbate organ dysfunction[17].

Microbial metabolites also play a crucial role in the interplay between gut dysbiosis and systemic inflammation during sepsis. SCFAs, such as acetate, propionate, and butyrate, are key anti-inflammatory metabolites produced by the fermentation of dietary fibers by commensal bacteria[22]. SCFAs maintain gut epithelial integrity by enhancing tight junction protein expression and modulating immune cell activity. In sepsis, the production of SCFAs is reduced due to the depletion of SCFA-producing bacteria, leading to impaired barrier function and increased inflammation. On the other hand, metabolites such as LPS and other PAMPs derived from pathogenic bacteria drive systemic immune activation[22].

In addition to LPS, other microbial-derived molecules, such as bile acid metabolites and uremic toxins, contribute to the pathophysiology of sepsis. Altered bile acid metabolism, driven by dysbiosis, can influence liver function and systemic immunity, while uremic toxins exacerbate kidney dysfunction during sepsis-associated acute kidney injury[24]. Together, these microbial metabolites create a complex network of interactions that link gut dysbiosis to systemic inflammation and multi-organ dysfunction.

ORGAN-GUT AXIS AND MULTI-ORGAN DYSFUNCTION IN SEPSIS

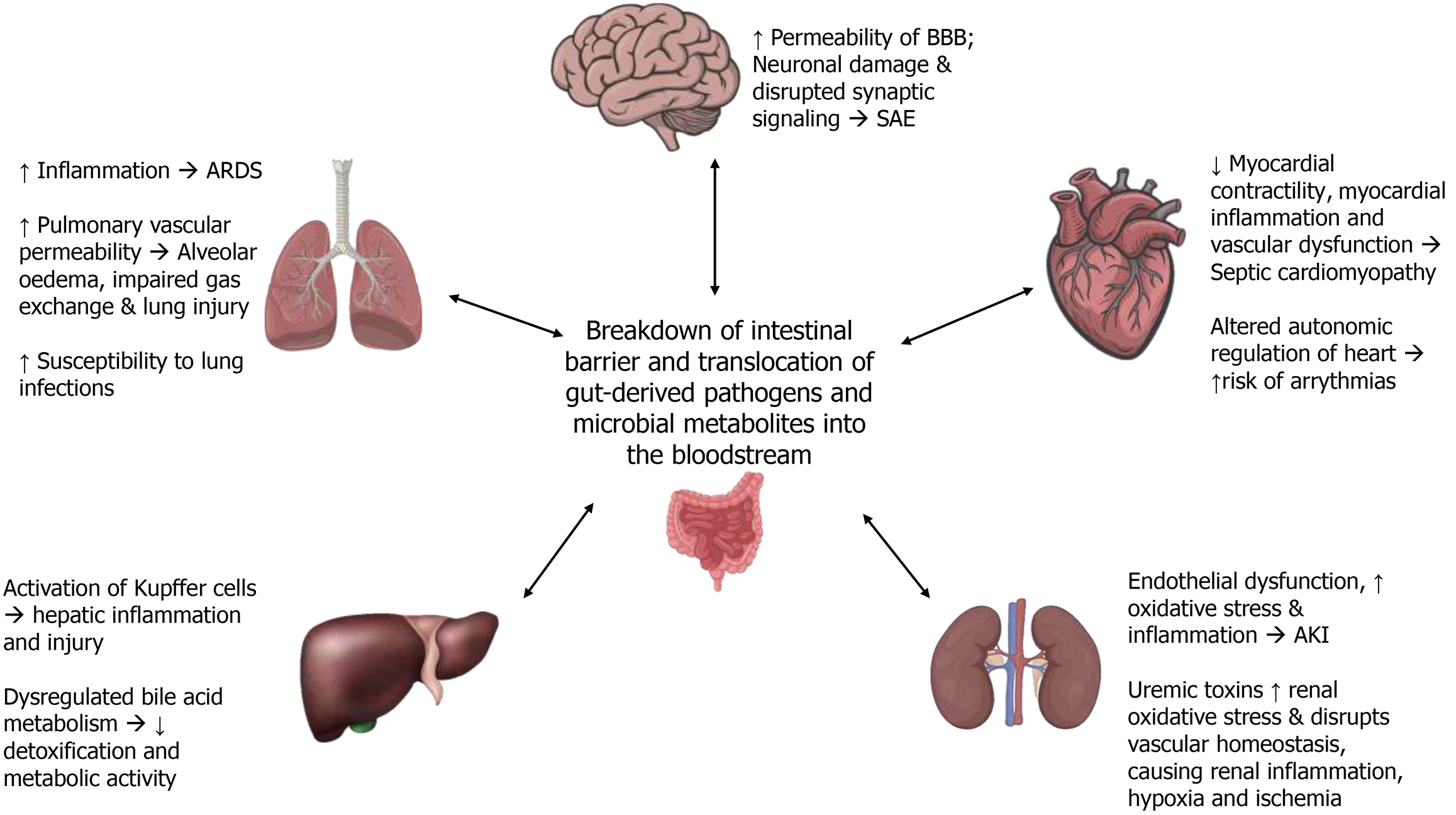

Sepsis induces a complex interplay between the gastrointestinal tract and various organ systems, mediated by the gut’s role as both a target and source of systemic inflammation. Dysbiosis, microbial translocation, and altered production of microbial metabolites contribute to a cascade of events that exacerbate MODS. This section explores the role of the gut-organ axes: Gut-liver, gut-lung, gut-kidney, gut-brain, and gut-heart—in the pathophysiology of sepsis (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Impact of gut-organ axes in sepsis on multi-organ dysfunction affecting the lungs, brain, heart, kidneys, and liver.

ARDS: Acute respiratory distress syndrome; SAE: Sepsis-associated encephalopathy; AKI: Acute kidney injury.

GUT-BRAIN AXIS

The gut-brain axis is a complex bidirectional communication network between the gastrointestinal system and the central nervous system (CNS), involving neural, endocrine, and immune signalling pathways[25,26]. In sepsis, this axis is profoundly disrupted, contributing to SAE, a severe neurological complication characterized by cognitive dysfunction, altered consciousness, and delirium. Gut dysbiosis, a hallmark of sepsis, plays a pivotal role in this disruption[27]. The most recent clinical guidelines on management of sepsis recognize mental obtundation or confusion as a specific defining symptom of sepsis, though this symptom is lacks sensitivity[28].

One key mechanism linking gut dysbiosis to neuroinflammation is the breakdown of the intestinal barrier, which allows microbial products such as LPS and other endotoxins to enter the bloodstream. These endotoxins activate systemic immune responses, leading to the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines like IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6[29]. These cytokines, compromise the blood-brain barrier (BBB), increasing its permeability. The influx of systemic cytokines and microbial products into the CNS triggers the activation of microglial cells, initiating a neuroinflammatory cascade that can damage neurons and disrupt synaptic signalling[30,31].

Microbial metabolites also play a critical role in the gut-brain axis during sepsis. SCFAs, which are produced by commensal gut bacteria through the fermentation of dietary fibers, are crucial for maintaining BBB integrity and modulating neuroinflammation. However, during sepsis, gut dysbiosis leads to a significant reduction in SCFA production[22]. This reduction impairs the brain's protective mechanisms, exacerbating neuroinflammatory responses and contributing to cognitive dysfunction[29]. Additionally, gut-derived neurotoxic metabolites such as ammonia, indoles, and tryptophan catabolites accumulate during sepsis and may further compromise neuronal function, leading to greater cognitive impairments.

The systemic inflammatory response induced by gut dysbiosis and microbial translocation can also alter neurotransmitter balance within the CNS, impacting cognitive and behavioral outcomes. For instance, tryptophan metabolism, which is regulated by gut bacteria, shifts toward the kynurenine pathway during inflammation. This shift produces neuroactive metabolites that can exacerbate excitotoxicity and oxidative stress, contributing to the neuropathological changes observed in SAE[32].

GUT-HEART AXIS

The gut-heart axis describes the bidirectional relationship between the gastrointestinal system and the cardiovascular system. During sepsis, this axis becomes critically important as gut dysbiosis and increased intestinal permeability contribute to systemic inflammation and myocardial dysfunction, leading to sepsis-induced cardiomyopathy.

The disruption of the intestinal barrier in sepsis allows microbial translocation and the release of endotoxins such as LPS into the systemic circulation. These endotoxins stimulate TLR4 on cardiomyocytes and vascular endothelial cells, leading to the activation of inflammatory signalling pathways. This results in the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α and IL-6, which impairs myocardial contractility, promote oxidative stress, and disrupt endothelial function[33]. The systemic inflammatory cascade, driven by gut-derived factors, exacerbates myocardial inflammation and contributes to cardiac dysfunction.

Gut dysbiosis during sepsis also affects the production of metabolites with direct cardiovascular effects. For example, trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO), a metabolite produced by gut bacteria from dietary choline and carnitine, has been associated with adverse cardiovascular outcomes[34]. Elevated TMAO levels during sepsis may exacerbate myocardial inflammation and vascular dysfunction, worsening the clinical course of septic cardiomyopathy. On the other hand, a reduction in SCFAs, which normally exert anti-inflammatory and cardioprotective effects, deprives the cardiovascular system of these beneficial metabolites, further contributing to myocardial injury[34].

Lastly, systemic inflammation driven by gut dysbiosis and microbial translocation can alter autonomic regulation of the heart. The release of various inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, IL-8 and TNF-α into the bloodstream in the course of sepsis inevitably results in aberrations to autonomic function[35]. This leads to a dysregulated cardiac response, characterized by reduced variability in heart rate and increased susceptibility to arrhythmias. These physiologic manifestations can predict morbidity and mortality in patients with severe sepsis[36]. The interaction between the gut microbiota and myocardial inflammatory signaling underscores the importance of the gut-heart axis in the pathophysiology of sepsis-induced cardiovascular dysfunction, highlighting its role in the progression of sepsis-related complications.

GUT-LIVER AXIS

The liver is the chemical factory in human body[37,38]. It makes and breaks carbohydrates, fats, protein, and lactic acid. Further, it acts as a filter of the portal circulation by trapping the microorganisms that travel upstream to prevent access to systemic circulation. The gut-liver axis represents a critical bidirectional communication network that integrates the gastrointestinal tract and the liver. Approximately 70% of the liver’s blood supply is derived from the intestine via the portal vein, creating a direct conduit for gut-derived substances, including nutrients, microbial metabolites, and toxins, to reach the liver. This anatomical and functional connection is particularly significant during sepsis, where the integrity of the intestinal barrier is compromised. Increased intestinal permeability allows the translocation of microbial products such as LPS, bacterial DNA, and peptidoglycans into the portal circulation[39,40]. These endotoxins activate hepatic immune cells, such as Kupffer cells, through Toll-like receptor signalling pathways. The resulting activation triggers the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α and IL-6, and chemokines, leading to hepatic inflammation, oxidative stress, and injury[41].

Recent studies have highlighted the role of gut microbiota dysbiosis in exacerbating sepsis-induced liver dysfunction. Dysbiosis, characterized by a reduction in beneficial bacteria and an overgrowth of pathogenic species, results in the production of harmful metabolites and a reduction in SCFAs[41]. SCFAs are critical for maintaining intestinal barrier integrity and exert anti-inflammatory effects on the liver. Their depletion weakens the barrier, facilitating the translocation of gut-derived pathogens and toxins into the liver. The accumulation of these microbial products exacerbates hepatic inflammation and contributes to hepatocyte apoptosis and necrosis[42]. Liver is hence the common site of intra-abdominal pyogenic abscess occurrence[43].

Furthermore, sepsis induces significant changes in bile acid metabolism. Bile acids, which play a role in regulating gut microbiota composition, become dysregulated during sepsis, promoting an environment that favors pathogenic bacteria[41]. This alteration creates a feedback loop where dysbiosis worsens, further compromising the liver's ability to detoxify and metabolize substances. This vicious cycle highlights the interdependence of the gut and liver during sepsis and underscores the gut-liver axis's role in propagating systemic inflammation and organ dysfunction.

GUT-LUNG AXIS

The gut-lung axis describes the intricate and bidirectional communication between the gastrointestinal tract and the respiratory system. During sepsis, disruption of the intestinal barrier allows microbial translocation and the release of endotoxins, such as LPS, into the systemic circulation[44]. These endotoxins can directly impact pulmonary function by increasing systemic inflammation and contributing to conditions like ARDS[45]. The systemic inflammatory response triggered by gut-derived products increases pulmonary vascular permeability, leading to alveolar edema, impaired gas exchange, and exacerbation of lung injury. In patients with severe sepsis and associated paralytic ileus, vomiting can cause aspiration pneumonia and this can directly worsen the impact on pulmonary gas exchange mechanism.

Recent research has elucidated the role of specific gut microbes in modulating immune responses within the lungs. Commensal gut bacteria can produce metabolites that influence pulmonary immunity. For example, SCFAs derived from fiber fermentation in the gut can enhance anti-inflammatory pathways in the lungs[22,46]. Conversely, dysbiosis reduces the availability of these protective metabolites, thereby compromising lung defense mechanisms. The presence of gut-derived endotoxins in the lungs activates alveolar macrophages and epithelial cells, resulting in the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6. These cytokines further perpetuate lung injury by recruiting neutrophils and promoting oxidative stress.

Additionally, studies have shown that gut-lung axis dysfunction may influence susceptibility to respiratory infections during sepsis[47]. A disrupted gut microbiome can impair mucosal immunity and the production of antimicrobial peptides, weakening lung defenses[48,49]. The findings highlight the gut-lung axis as a key contributor to sepsis pathophysiology and suggest that modulating gut microbiota may have protective effects against lung injury.

GUT-KIDNEY AXIS

The gut-kidney axis encompasses the bidirectional interactions between the gastrointestinal tract and renal function, playing a critical role in sepsis-associated AKI. During sepsis, increased intestinal permeability and gut dysbiosis allow translocation of microbial endotoxins and uremic toxins into the bloodstream[50]. These toxins, including indoxyl sulfate and p-cresyl sulfate, are derived from the metabolism of gut bacteria and have been implicated in the progression of AKI. These metabolites induce endothelial dysfunction and promote oxidative stress and inflammation within the kidneys, exacerbating renal injury[50]. In patients with severe sepsis, abdominal imaging with intravenous contrast agents is necessary for source identification, and AKI may ensure due to contrast nephropathy. In addition, intravenous antibiotics may also worsen the AKI if appropriate dose modifications are not done timely.

Gut dysbiosis during sepsis also alters the composition of beneficial bacteria, leading to a reduction in SCFA production[51]. SCFAs, such as butyrate, play a protective role in renal health by modulating immune responses and reducing inflammation. The loss of these anti-inflammatory metabolites compromises renal protection and facilitates the activation of inflammatory pathways that drive kidney injury. Additionally, gut-derived endotoxins can directly activate toll-like receptors on renal tubular cells, amplifying cytokine production and promoting apoptosis[51].

Recent studies have highlighted the importance of microbial metabolites in mediating gut-kidney interactions during sepsis. Uremic toxins derived from gut bacteria have been shown to exacerbate renal oxidative stress and disrupt vascular homeostasis[52]. Furthermore, dysbiosis-induced systemic inflammation increases vascular permeability in the kidneys, leading to ischemia and hypoxia that exacerbate AKI[52]. These findings underscore the importance of the gut-kidney axis in sepsis pathophysiology and suggest that targeting gut dysbiosis could mitigate renal injury in septic patients.

THERAPEUTIC POTENTIAL OF TARGETING THE GUT MICROBIOTA

Given the central role of gut dysbiosis in the pathophysiology of sepsis, targeting the gut microbiota represents a promising therapeutic avenue. Emerging therapies aim to restore microbial balance, enhance intestinal barrier integrity, and modulate systemic inflammation through interventions such as prebiotics, probiotics, synbiotics, and fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT). These strategies have shown potential in preclinical and early clinical studies, although significant challenges remain.

Prebiotics, non-digestible dietary fibers that stimulate the growth of beneficial gut bacteria, have demonstrated potential in restoring microbial balance. By promoting the growth of SCFA-producing bacteria, prebiotics can improve intestinal barrier integrity, reduce gut permeability, and modulate inflammatory responses[53]. Similarly, probiotics, live microorganisms that confer health benefits to the host, have shown promise in attenuating sepsis-induced gut dysbiosis. Specific strains of Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium have been reported to reduce microbial translocation, lower systemic inflammation, and improve survival in animal models of sepsis[53]. This is done through competition for resources for growth[54], the production of bacteriocins like plantaricin by Lactobacillus plantarum targeting Salmonella and Escherichia coli[55], the production of organic acids by probiotic strains such as Acetobacter aceti and Lactobacillus to inhibit the growth of bacteria and fungi by causing sublethal damage and promoting bacterial viability loss[56] and the production of hydrogen peroxide and other novel metabolites[57].

Synbiotics, a combination of prebiotics and probiotics, aim to synergize the benefits of these therapies by simultaneously promoting beneficial bacterial growth and introducing specific probiotic strains. In experimental studies, synbiotics have been associated with reduced cytokine production, improved intestinal permeability, and enhanced microbial diversity[53]. Another emerging approach, FMT, involves the transfer of stool from a healthy donor to restore a balanced gut microbiota in the recipient. Although primarily used to treat recurrent Clostridioides difficile infections[58], FMT has shown potential in ameliorating gut dysbiosis and improving outcomes in experimental sepsis models[59].

Advances in microbiota-based drugs are also gaining attention. These include defined microbial consortia, genetically engineered bacteria designed to secrete anti-inflammatory or barrier-protective molecules, and postbiotics—metabolites or components derived from probiotics that exert biological effects. Such approaches aim to harness the beneficial properties of gut microbiota without the variability associated with live microbial therapies[60].

Despite these promising interventions, several challenges limit the clinical application of microbiota-targeted therapies in sepsis. One major limitation is the heterogeneity in gut microbiota composition among individuals, influenced by factors such as genetics, diet, age, and antibiotic use. This variability complicates the standardization of therapies and their efficacy across diverse populations. Additionally, the dynamic nature of gut microbiota during sepsis poses challenges in identifying optimal treatment windows and microbial targets.

Interindividual variability in response to microbiota-targeted therapies further complicates their clinical use. Probiotic strains that benefit some individuals may have limited or adverse effects in others, depending on the existing microbiota composition and the patient’s immune status. Furthermore, the safety of microbiota-targeted interventions in critically ill patients remains a concern, as certain probiotics or FMT procedures carry a risk of introducing opportunistic infections or exacerbating inflammation.

Another challenge lies in the lack of reliable biomarkers to identify patients who would benefit most from microbiota-targeted therapies. Without precise diagnostic tools to assess gut dysbiosis or microbiota-related inflammation, the implementation of these therapies remains empirical and less targeted.

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS

This review highlights advances in understanding gut dysbiosis in sepsis and its systemic implications. Evidence establishes a link between gut microbiota alterations and sepsis outcomes, especially in MODS. Dysbiosis, marked by reduced microbial diversity and pathogenic overgrowth, exacerbates inflammation, compromises intestinal integrity, and promotes microbial translocation. The gut-organ axes—gut-liver, gut-lung, gut-kidney, gut-brain, and gut-heart—provide a framework for how gut-derived factors affect organ pathologies in sepsis, supporting microbiota-targeted therapies.

However, gaps remain, including a lack of longitudinal studies tracking microbiota changes throughout sepsis. These are crucial for identifying causal relationships and therapeutic windows. Preclinical models often do not translate well to human sepsis, and large-scale randomised controlled trials are needed to confirm the efficacy of microbiota-targeted interventions like probiotics and FMT. Early clinical studies show promise but vary in design, limiting generalizability. Additionally, the safety of microbiota-based therapies in critically ill patients needs further evaluation.

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS

The clinical relevance of microbiota-based approaches in sepsis lies in their potential to modulate systemic inflammation, restore intestinal barrier integrity, and prevent organ dysfunction. Targeting the gut microbiota represents a novel therapeutic paradigm that complements existing sepsis management strategies focused on infection control and supportive care. Interventions that restore microbial balance, such as the use of SCFA-producing probiotics or postbiotics, could mitigate the downstream effects of dysbiosis, including immune dysregulation and organ-specific pathologies.

Moreover, the concept of the organ-gut axis emphasizes the interconnectedness of organ systems during sepsis, highlighting the need for integrated therapeutic approaches. For instance, addressing gut-derived inflammation could have far-reaching benefits for the liver, lungs, kidneys, brain, and heart, potentially improving overall sepsis outcomes.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Future research should focus on integrative studies examining organ-specific interactions along the gut-organ axes. These studies could reveal how gut-derived factors influence each organ's unique pathophysiology, leading to targeted therapies for both systemic and organ-specific aspects of sepsis.

Multidisciplinary collaboration is crucial for advancing microbiota-based therapies. Teams of microbiologists, immunologists, critical care specialists, and bioinformatics experts can identify microbial signatures linked to sepsis and design precision therapies. Advances in high-throughput sequencing, metabolomics, and computational modelling will enhance our understanding of gut microbiota dynamics and their systemic effects.

Randomised controlled trials are necessary to determine the safety and efficacy of microbiota-based therapies in diverse sepsis populations, with biomarkers playing a crucial role in stratifying patients based on microbiota profiles and monitoring treatment responses. Integrating microbiota-based therapies into a multimodal sepsis management framework holds the potential to transform treatment approaches and alleviate the global burden of this life-threatening condition. In this context, antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) represent a promising adjunct due to their broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity and ability to overcome bacterial drug resistance[61], making them advantageous over traditional antibiotics. Furthermore, as natural host defence molecules, AMPs are well-suited for development into novel antimicrobial therapies, particularly when paired with advanced drug delivery systems[62], offering a strategic approach to combat drug-resistant infections in sepsis management.

CONCLUSION

In summary, gut dysbiosis is pivotal in sepsis, driving systemic inflammation and contributing to MODS. It worsens inflammation through intestinal barrier disruption, microbial translocation, and toxic metabolite production. The gut’s interaction with organs like the liver, lungs, kidneys, brain, and heart underscores its role in sepsis severity. Targeting the gut microbiota offers a promising approach to mitigate sepsis complications. Interventions such as probiotics, prebiotics, and FMT aim to restore microbial balance and improve intestinal integrity. Advances in microbiota-based therapies could transform sepsis management by addressing systemic dysregulation. Research and clinical trials are vital to developing effective therapies. Integrating these interventions into a multidisciplinary sepsis management framework could improve outcomes and reduce the global burden of the condition.