Published online Dec 9, 2025. doi: 10.5492/wjccm.v14.i4.104703

Revised: April 24, 2025

Accepted: August 20, 2025

Published online: December 9, 2025

Processing time: 334 Days and 20 Hours

Diagnostic errors in critical care settings are a significant challenge, often leading to adverse patient outcomes and increased healthcare costs. Millimeter-wave (mmWave) technology, with its ability to provide high-resolution, real-time data, offers a transformative solution to enhance diagnostic accuracy and patient safety. This paper explores the integration of mmWave technology in intensive care units (ICUs) to enable non-invasive monitoring, minimize diagnostic errors, and improve clinical decision-making. By addressing key challenges, including data latency, signal interference, and implementation feasibility, this approach has the potential to revolutionize patient monitoring systems and set a new standard for critical care delivery. The paper discusses the high prevalence of diagnostic errors in medical care, particularly in primary care and ICUs, and emphasizes the need for improvement in diagnostic accuracy. Diagnostic errors are responsible for a significant number of deaths, disabilities, prolonged hospitalizations and delays in diagnosis worldwide.

To address this issue, the paper proposes the use of ultrafast wireless medical big data transmission in primary care, specifically in remote smart sensors monitoring devices. It suggests that wireless transmission with a speed up to 100 Gb/s (12.5 Gbytes/s) within a short distance (1-10 meters) is necessary to reduce diagnostic errors.

The method used in the study, includes system design and testing a channel sounder operating at 63.4-64.4 GHz frequency range. The system demonstrated dynamic range of 70 dB, noise level of -110 dBm, and a time resolution of 1 ns. The experiment measured the impulse response of the channel in 36 locations within the primary care/ICU scenario.

The system was tested in a simulated ICU environment to evaluate the Latency: Assessing the time delay in data transmission and processing. The results of the study showed that the system met the requirements of ICUs, providing excellent latency values. The delay spread and excess delay values were within acceptable limits, indicating successful resolution of ICU requirements. The paper suggests timely deployment of such a system. Impact on data transmission: A 100 MB magnetic resonance imaging scan can be transmitted in approximately 0.008 seconds; A 1 GB scan would take approximately 0.08 seconds; This capability could revolutionize healthcare, enabling real-time remote diagnostics and comparisons with artificial Intelligence models, even in large-scale systems.

The experiment demonstrated the feasibility of using high-speed wireless transmission for improved diagnostics in ICUs, offering potential benefits in terms of reduced errors and improved patient outcomes. The findings are deemed valuable to the medical community and public healthcare systems, and it is suggested further research in this area.

Core Tip: Millimeter-wave technology offers a transformative approach to preventing diagnostic errors in critical care. By providing precise, non-invasive, and real-time monitoring, this innovation enhances patient safety and supports better clinical outcomes. Future research should focus on refining the technology, addressing implementation challenges, and exploring its potential across diverse healthcare environments. We anticipated that our study to be a starting point for more sophisticated research in detecting and preventing diagnostics errors in primary care along with artificial intelligence, machine learning, internet of things and high computation in terms of mm-Wave wireless transmission.

- Citation: Siamarou AG. Preventing diagnostic errors in critical care using millimeter-wave technology: A transformative approach to patient safety. World J Crit Care Med 2025; 14(4): 104703

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3141/full/v14/i4/104703.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5492/wjccm.v14.i4.104703

The challenge of diagnostic errors in critical care environments, such as intensive care units (ICUs), are high-pressure settings where rapid and accurate diagnoses are essential. Despite advancements in medical technology, diagnostic errors remain a persistent issue, contributing to delayed treatment, increased morbidity, and preventable deaths. The impro

Intensive care patients are particularly vulnerable to erroneous diagnosis frequently require immediate diagnosis, receive treatment at several clinics and often undergo laboratory and tomographic studies. False diagnosis is possibly the most damaging and expensive form of erroneous diagnosis[2-5]. Diagnostic errors represent a critical, yet often underappreciated, challenge in contemporary healthcare systems. It is estimated that approximately 12 million adults in the United States are affected by diagnostic errors each year, with one-third of these errors resulting in serious patient harm[2,3].

Moreover, the financial burden of diagnostic errors is substantial. A 2020 study estimated that diagnostic inaccuracies contribute to an additional $750 billion in healthcare costs annually in the United States (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2015). Collectively, these statistics underscore the urgent need for systemic reforms to en

Most of the errors were related to the process interruption in the doctor's clinical sessions, delays or illnesses, complications of additional diagnostic tests or treatments that do not actually exist. This document reflects random factors associated with examination results in primary care and ICUs, a high level of knowledge in order to prevent diagnostic errors and to develop an understanding of pathological errors[10-17]. Perception errors are often associated with systemic factors, such as poor information flow and communication problems and failures[18-26]. Diagnostic inaccuracies are implicated in approximately 10% of patient deaths and 6%-17% of hospital adverse events as references by Singh et al[15,16,18,21].

Delays are particularly important for many applications i.e. mental health, networking, smart meters, automation, manufacturing, robotics, transportation, healthcare, entertainment, virtual reality and education. While the use of 60 GHz frequencies in ICU environments is generally safe when designed and regulated properly, potential risks such as thermal effects, electromagnetic interference, and psychological concerns must be carefully mitigated. By adhering to strict safety standards, performing thorough testing, and educating staff and patients, the risks can be minimized, ensuring a safe and effective deployment of Millimeter-wave (mmWave) technology in critical care settings.

There are potential risks to the equipment installed in ICUs, such as monitors, ventilators, and dialysis machines, when high-frequency technologies like 60 GHz mmWave are used. The primary concern is electromagnetic interference (EMI), which can disrupt the proper functioning of medical devices. 60 GHz mmWave technology in ICUs introduces potential risks to installed medical equipment, these risks can be mitigated with proper design, testing, and compliance with regulatory standards. By implementing strategies like EMI shielding, frequency management, and redundant systems, the integration of mmWave technology can be made safe without compromising the functionality of life-critical equip

The promise of mmWave technology mmWave technology, operating in the 30-300 GHz spectrum, is renowned for its high-frequency characteristics, enabling precise and non-invasive data acquisition. Originally developed for telecommunications and imaging, mmWave technology has shown great promise in healthcare applications, including real-time monitoring and enhanced diagnostic capabilities.

Advantages of mmWave technology: mmWave technology offers several advantages for critical care monitoring: Non-invasive monitoring: Enables continuous assessment of vital signs without direct contact; High spatial resolution: Facilitates detailed imaging of physiological changes; Real-time data transmission: Supports instant clinical decision-making; Low interference: Operates effectively in environments with electromagnetic noise.

This paper investigates the application of mmWave systems in critical care to mitigate diagnostic errors and improve patient safety. It highlights the severity of diagnostic errors in critical care environments, such as ICUs and their impact on adverse patient outcomes and increased healthcare costs. The paper provides a detailed exploration of integrating mmWave technology in ICUs, focusing on non-invasive monitoring, minimizing diagnostic errors, and improving clinical decision-making. The innovative aspects of this technology, especially in addressing key challenges such as data latency, signal interference, and implementation feasibility, offer promising new directions for patient monitoring systems.

Signal Interference Challenges: ICUs are dense with medical equipment and staff activity, which can disrupt or degrade mmWave signal quality. This limits its effectiveness without additional refinement. Compatibility Issues: MmWave systems must seamlessly integrate with existing monitoring devices and electronic health record systems. This requires extensive customizations, which can be both time-consuming and costly. Healthcare regulations around the use of mmWave in patient care are still evolving. Ensuring compliance with safety, accuracy, and compatibility standards is a time-intensive process. Addressing these hurdles will require collaboration among technology developers, healthcare providers, and policymakers. As research advances and integration becomes easier, mmWave technology could become a cornerstone of modern ICU care.

In case that the technology gets failed for any reason, the system should be equipped with a failure detection mechanism that immediately notifies ICU staff of the issue via alarms or notifications on monitoring dashboards. Switch to alternative monitoring methods already in place in the ICU, such as traditional bedside monitors (e.g., electrocardiogram, SpO2, respiratory monitors), wearable devices that use established wireless technologies (e.g., Bluetooth or Wi-Fi) and manual observation if electronic backups are unavailable. ICU staff should have access to technical support teams trained in resolving common issues. A combination of mmWave with fiber optics for data transmission to ensure data integrity even if mmWave devices fail.

Communication errors, especially with regard to the lack of communication between physicians, remain the most common factors. Another factor that improves security is the availability of better information[15,16,17,26]. Smart sensors monitoring offers a wide range of manuals, drug links and tools for treating infectious diseases. For example, smart screens can search for and recognize signals indicating the presence of decompensation in a patient. Information systems can support treatment in a number of important ways, providing patients with important information in laboratory settings and calculating doses of weight-based medications. Smart devices with electronic health cards can also be used to detect eliminate and monitor adverse events. Following anesthesia, drug safety monitoring of patients could be further investigated[18,19,20]. Almost half of all serious drug errors are due to the fact that doctors do not have enough infor

Big data analysis in the health sector can reduce treatment costs, provide epidemics with useful information such as coronavirus disease 2019, prevent diseases and improve overall quality of life. Big data refers to the large amount of information generated by digitization. Medical researchers can use large amounts of data, i.e. 100024 Mb/s, which can be transferred wirelessly over a second on treatment plans and recovery rates for i.e. cancer patients to find the trends and treatments that have the highest success rates in the real world. Radiologists no longer need to look at images, but will need to analyze the results of algorithms that will inevitably study and remember more images than they could in a lifetime[21,22,23,26]. Together, these technologies can increase the effectiveness of pandemic prevention and treatment and lead to the digital transformation of health systems in response to major public emergencies.

Effective communication and data exchange is necessary to control those infected and to manage critical situations. Research data shows that information technology can reduce the frequency of errors of various types and possibly the frequency of side effects associated with them. The main categories of strategies to prevent mistakes and side effects include tools that can improve communication, and make knowledge more accessible. This provides basic information, facilitates calculations, performs real-time checks, monitoring and provides decision support.

The data are visual images of the inner body that can be created in various ways [e.g., X-ray, ultrasound, computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance and positron emission tomography] collected for diagnostic identification. Visual images are usually interpreted by a radiologist or, in some cases, nuclear doctors, emergency doctors, or cardiologists[27-30]. Diagnostics analytics can find the root-causes, identify image anomalies, filtering and correlation of big data.

5G and beyond, the fifth generation of wireless mobile technology, can provide exceptional connectivity and high-speed data transfers that can help change the way doctors provide care. Data shows that up to 40500 adults in ICU in the United States may die due to improper treatment due to errors in the intensive care unit each year[1-9]. However, with respect to diagnostic errors, relatively little attention and means to support research are given. Future research should be aimed at a prospective assessment of the prevalence and impact of diagnostic errors and possible strategies to address them.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) can recognize restrained forms that humans can miss or ignore. Most cancers are diagnosed by biopsy however; a cancer diagnosis may be missed. A more recent approach uses magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). There is no question that cancer is a very complex disease. A tumor can have more than a billion cells. To better un

The integration of mmWave (millimeter-wave) technology with emerging technologies such as AI, internet of things (IoT), and machine learning (ML) presents significant opportunities to revolutionize diagnostic and monitoring systems. By combining the high-speed data transmission and sensing capabilities of mmWave with intelligent algorithms and interconnected devices, these technologies can offer real-time, efficient, and highly accurate solutions for various sectors, including healthcare, industrial monitoring, and more.

MmWave technology provides high-resolution imaging and sensing crucial for diagnostic applications. When paired with AI algorithms, this technology can enhance real-time analysis of data, aiding in the early detection of medical conditions like tumors or fractures. AI-driven systems can automatically identify complex patterns in mmWave data through deep learning, improving diagnostic accuracy and enabling faster interventions. Real-time monitoring powered by AI ensures timely alerts and improved patient outcomes.

IoT networks are transforming industries by enabling devices to communicate and share data seamlessly. mmWave technology supports high-speed, low-latency communication essential for IoT devices, particularly in healthcare. mmWave-enabled wearable devices or medical equipment can continuously collect and transmit data to cloud systems or edge devices. This allows for real-time health monitoring, predictive diagnostics, and immediate alerts to medical professionals, enhancing patient safety and care. Furthermore, IoT systems can use mmWave sensors for predictive main

The combination of mmWave technology with AI and ML creates a powerful synergy for diagnostic and monitoring systems. AI algorithms can continuously refine and adapt to new data, improving system accuracy over time. Machine learning enhances sensor sensitivity and data interpretation, ensuring that these systems are not only precise but also capable of evolving with each use. For example, AI can leverage mmWave data to predict medical conditions like cardiovascular events, distinguishing between normal and abnormal readings with greater accuracy.

One of the key benefits of combining mmWave with AI and ML is the ability to process data in real-time. In high-stakes environments like healthcare or industrial safety, real-time analysis is crucial. mmWave sensors, when integrated with AI, can rapidly detect changes in the environment and trigger autonomous decisions. In healthcare, for instance, real-time data analysis could alert medical staff of potential risks, enabling swift intervention. Similarly, in industrial settings, mmWave sensors can monitor equipment health and predict failures before they occur, reducing downtime and enhancing safety. The integration of mmWave technology with AI, IoT, and machine learning holds immense promise for transforming diagnostic and monitoring systems. By leveraging the strengths of each of these technologies, it is possible to create intelligent, efficient, and real-time systems capable of improving accuracy, timeliness, and predictive capabilities. These advancements will not only enhance healthcare outcomes but will also have a profound impact on a range of industries, paving the way for more autonomous, efficient, and data-driven environments.

Advanced medical services continue to address the issue of limited resources and an increasing number of patients. Due to a lack of staff and protocol orders, patients are more likely to be sent offline or identified by offline providers if they are unable to verify the status of the provider network[27-30]. When fully implemented, the sector will benefit greatly from advanced 5G technologies, as real-time access to data and the ability to make secondary decisions about human life are critical to healthcare systems. Healthcare professionals share their experiences with colleagues without getting too close to the patient. Better communication can help arrive at a diagnosis faster. The main transfer of files, images and other information is the low delay, about 1ms. Effective telemedicine requires a network that can support high-quality real-time video without slowing down the installed network. Adding high-speed 5G networks to existing architecture can support real-time medical advice videos to improve access to health care and quality care. Telemedicine already exists today, but 5G and beyond contributes to significant activation and acceleration. In addition, 5G will support healthcare technology as an external physician, extending the scope of the organization beyond the hospital. For example, 5G and AI allows language translators to communicate with patients and doctors on the other side of the network[28,29].

Smart ambulances need to carry out communication and emergency diagnostic equipment and play a unique role in health systems. In addition to transporting patients safely, smart ambulances can provide telemedicine, collect information, and send it to a hospital to develop treatment and isolation programs. To achieve this, the network needs to provide fast and stable data communication that can help the ambulance. Remote monitoring of patients is possible through telemedicine, including drug administration and coordination, based on data collection and analysis in real time[30-33]. Medical device providers use IoT devices to remotely monitor vital organs (heart, liver, lungs, etc.), monitor medications, and transmit data to help employees make informed decisions more quickly. 5G and higher technology improves connectivity to mobile devices, uses more speed to increase data capacity, supports more data transmission, and helps health care providers improve health care in real time on the evaluation and improvement of medical systems with the potential of information technology in the field of healthcare. Reported information technology related errors are shown in Table 1. One of the most difficult tasks is the desire to achieve a delay less than 1 ms. Health, logistics, au

| Errors |

| Abnormal imaging errors |

| Communications errors |

| Follow up errors |

| Tracking errors |

| Outpatient communication medical errors |

| Delayed communication in radiology |

| Ordering and interpretation errors |

| Detection errors |

The current capacity of different medical imaging modalities is shown in Table 2[34]. Medical imaging modalities generate data of varying sizes based on their specific use cases, resolution, and imaging techniques. The integration of high-speed wireless technologies like mm-Wave can enhance the transmission and analysis of these large datasets in real-time, especially in high-demand environments like ICUs or during telemedicine consultations. It can be clearly seen the data bandwidth increase of the proposed mm-wave indoor network capabilities in respect to the current capacities, the speeds and capabilities offered to the medical society. The massive data bandwidth increase (Table 3) of the proposed mm-wave indoor network capabilities with respect to the current capacities, speeds and capabilities offered to medical society can be clearly observed.

| Medical device | Data rates/capacity |

| Ultrasound, radiology and cardiology | 256 Kbytes (image size) |

| Magnetic resonance imaging | 384 Kbytes (image size) |

| Scanned X-ray | 1.8 Mbytes (image size) |

| Digital radiography | 6.0 Mbytes (image size) |

| Mammography | 24 Mbytes (image size) |

| Compress and full motion video (telemedicine) | 384 Kbps to 1.544 Mbps |

| Indoor 60 GHz mm-wireless technology | 100 Gbps/12.5 Gbytes/s |

| 1 byte (B) contains 8 bits of information |

| 1 kB contains 8000 bits of information |

| 1 MB contains 8000000 bits of information |

| 1 GB contains 8000000000 bits of information |

| 100 Gbits/s equals to 12.5 GB-100000000000 bits of information |

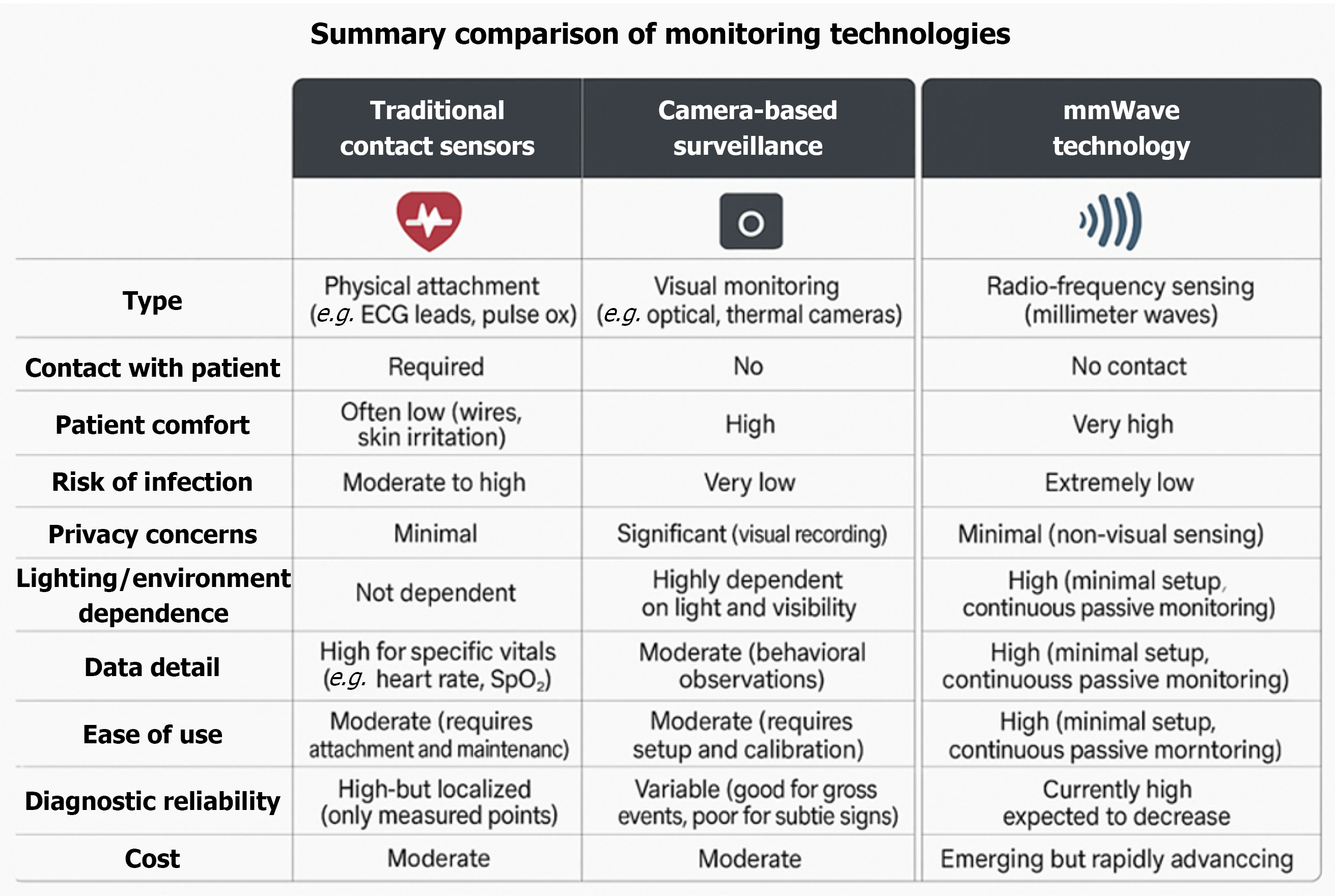

While mmWave technology offers exciting possibilities for enhancing patient monitoring in critical care, its true value becomes most apparent when compared to existing methods. Traditional contact-based sensors and camera-based surveillance systems have long been used to track vital signs and patient behavior, but they each have inherent limitations that can contribute to diagnostic errors and patient discomfort. A comparative analysis of these technologies reveals how mmWave solutions not only address many of these challenges but also introduce transformative advantages in terms of accuracy, patient safety, and clinical workflow efficiency. A summary comparison of monitoring technologies is shown in Figure 1.

Employing mmWave sensing in critical care requires specialized hardware (beamforming antennas, on-device processors), high-speed private networks (5G/6G), and smart edge computing for real-time data analysis. AI algorithms will extract vital signs, detect anomalies, and compress data efficiently. Key challenges like device compatibility, data security, and patient privacy can be addressed by using standardized APIs (HL7/FHIR), strong encryption (AES-256, TLS 1.3), blockchain for data integrity, and anonymization at the sensor level. By combining advanced technology and proactive security, mmWave solutions can move from concept to safe, real-world hospital use, significantly improving diagnostic accuracy and patient safety.

Study design: Data capacity and fast data transmission and communication in primary care/ICUs are inadequate to cover the expanding needs of the patients. Fast diagnosis and fast treatment will reduce significantly human losses and permanent disabilities at ICU’s due to diagnostics errors. The conceptual literature review, which is Part A of this contribution, uses qualitative published research work and articles, in which several studies show that technology-based decision making can significantly improve patient outcomes. Part B of the paper adheres on current needs and information regarding designing, implementing, experimenting and evaluating a novel high-resolution system at the 57-64 GHz band. The aim is to resolve the technical difficulties on the growing and expanding emergency care needs in terms of speed, computation capability, fast communication, and big data transmission.

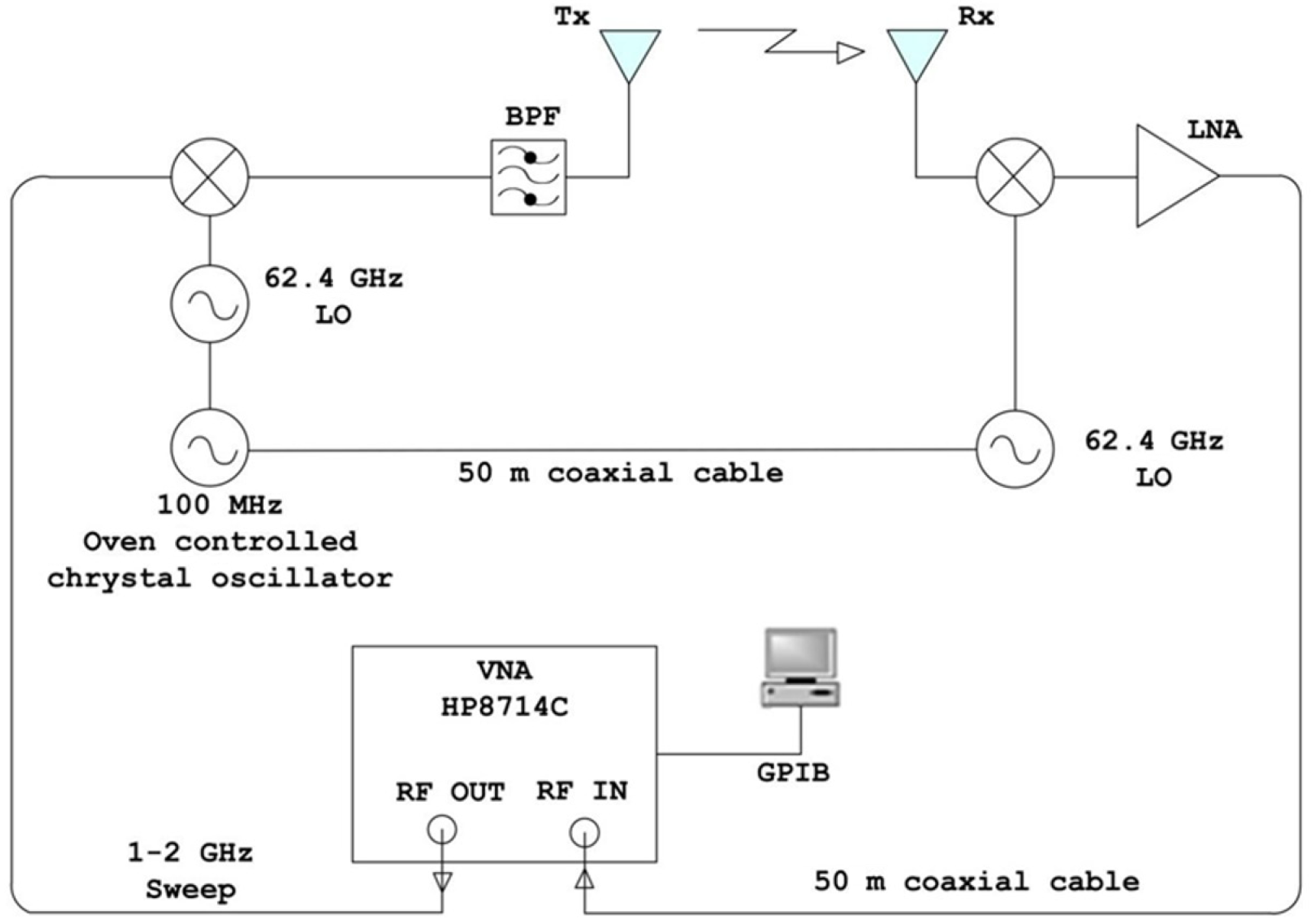

The 100 Gbps (12.5 Gbytes /s) 1-10 m indoor wireless system: Transmitter: In order to characterize the expanding needs in terms of speed and capacity the primary care/ICU care scenario, a 63.4-64.4 GHz channel sounder was designed, tested inside an anechoic chamber and used by the author for the experiment[35-37]. The experimental hardware is shown in Figure 2. At the transmitter, the output of a network (VNA) analyzer is transmitted in steps of 1 to 2 GHz, and then converted (mixed) in frequency with the carrier at 62.4 GHz before transmission[35-37]. An external controlled 10 MHz crystal was used as a reference for both locked oscillators. The up converter has an intermediate frequency bandwidth from DC to 6 GHz. The converter output signal consists of two side bands at a level of about 6-7 dB below the IF signal level. The upper side band with frequencies from 63.4 to 64.4 GHz passes through a belt filter in the center of 64.4 GHz. The filter also eliminates the lower side band between 60.4 and 61.4 GHz. The level of conquest (discharge zone) is set to > 20 dB. At the receiver, a 62.4 GHz signal is generated by the same 100 MHz Oven Controlled Oscillator, by connecting a flexible sucoflex coaxial cable with very little losses of 50 m length, from the transmitter to the receiver. The specified cable losses are between 0.23 and 0.73 dB/m. The connection between transmitter and receiver provides phase information.

The 1 to 2 GHz signal is synchronously recorded, amplified by an LNA with a bandwidth of 900 to 2000 MHz and a gain of 32 dB and then fed back to the reception port of the VNA via a second bendable 50 m Sucoflex coaxial cable This includes measuring the complex transfer function of the channel[36-42]. The dynamic range of the system is estimated at 70 dB with a minimum noise level of -110 dBm. The bandwidth of the measurement system was limited by the band

| Frequency | (GHz) | 63.4-64.4 | Environment | Number of Locations | Frequency (GHz) | Area (m) |

| Time resolution (ns) | 1 | Empty | 38 | 63.4-64.4 | 12.80 × 6.92 × 2.60 | |

| Frequency (KHz) | Resolution | 625 | Furniture | 38 | 63.4-64.4 | 12.80 × 6.92 × 2.60 |

| Spatial imaging | Resolution | 460-470 | Types of errors[12] diagnostics: Diagnostic error or delay. Refusal to use these tests, use of old tests or treatment methods, inaction as a result of observation or testing; Treatment: An error occurred while starting a function, process, or test. Wrong prescription, wrong dose or use of the drug, preventable delay in treatment or reaction to abnormal tests; Prevention: Failure to provide preventive treatment. Inadequate monitoring or controls system crash due to communication failure | |||

| (nm) | ||||||

| Dynamic range dB | 70 | |||||

| Max. excess delay (ns) | 1600 | |||||

| Operation range (m) | 50 | |||||

| Bandwidth (GHz) | 1 | |||||

| Applications in terms of speed and data capacity | HDTV, video, medical imaging, data transfer, integrating multiple data streams | |||||

| Big data | ||||||

| Analytics | ||||||

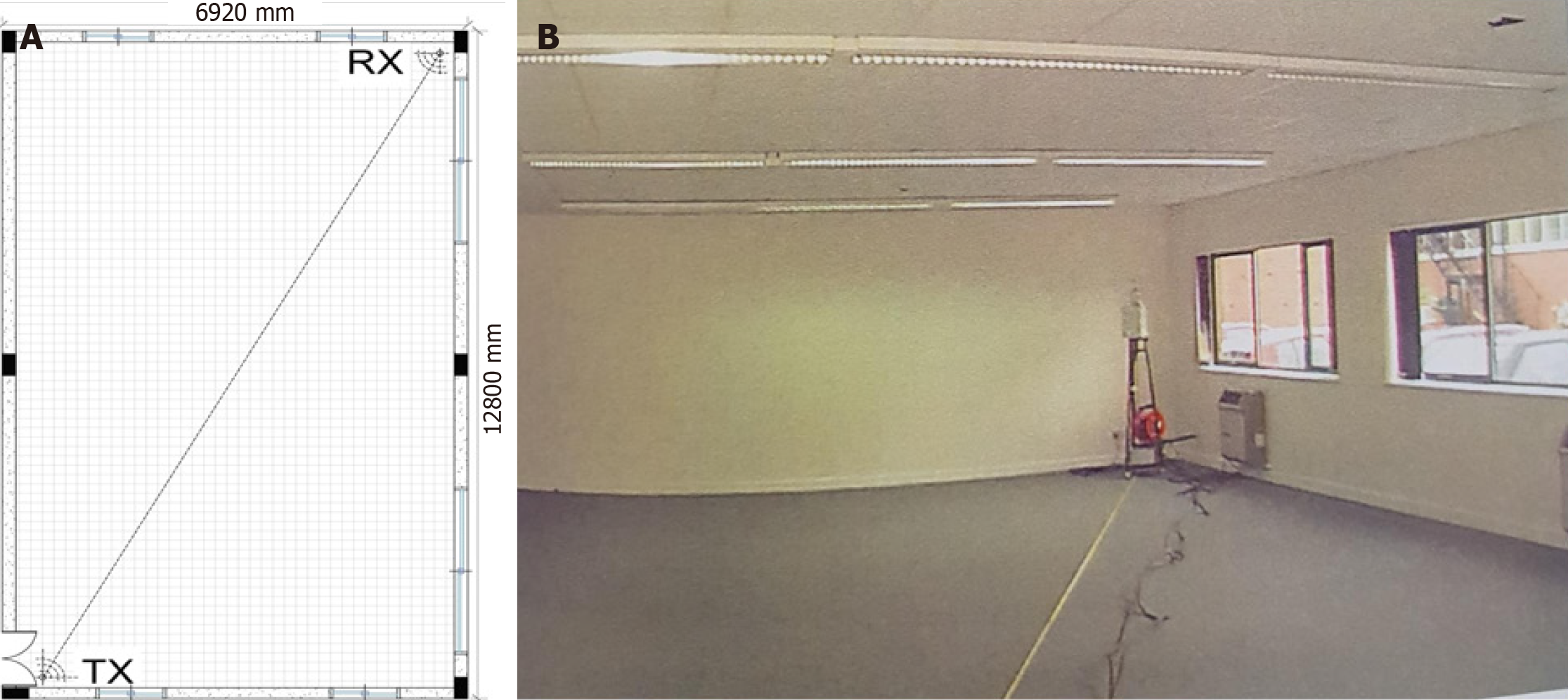

Very useful information can be obtained from measurements on various indoor and outdoor channels, delay spread and power losses. Two antenna configurations were used for each set of the 38 measurements. In the first configuration, two standard horn antennas were used on the transmitter and the receiver. In the second alignment, a standard Horn antenna and an omnidirectional antenna were used as transmission and reception antennas. Prior to the measurements, the equipment and cables were calibrated in the anechoic chamber to extract their influence from the measured data. Since the Vector Network Analyzer measures the complex transmission function of the radio channel, it was necessary to eliminate the effect of the antennas.

A total of 76 impulse responses were acquired for these experiments by sampling the channels at 60 λ intervals, where λ is the wavelength.

The ICU room scenario is shown in Figure 3A and B. Both transmitter and receiver were placed at a height of 1.70 m above floor level. A total of 76 impulse responses were acquired for these experiments by sampling the channels at 60 λ intervals, where λ is the wavelength. The room is a relatively new type of building, with thick brick and concrete walls, carpeted floors and polystyrene tiles[36-42]. The size of the environment, along with the number of measuring positions used in each case, is shown in Table 1. The transmitter was fixed in a strongbox and left in a motionless position at one end for propagation measurements in the room. The receiver has been moved step by step to numerous fixed positions along the center line. At this point, the fixed base station is at an angle and the moveable receiver moves along a sta

Diagnostic errors are an underappreciated cause of preventable mortality and morbidity in hospitalized patients, accounting for an estimated 40000-80000 annual deaths in United States. An incorrect diagnosis that harms the patient is often associated with various errors, as well as individual and systemic factors. Knowing the most common problems and factors can help define and prioritize strategies to avoid misdiagnosis. It's important to recognize that while the proposed deployment of high-speed wireless systems in ICUs has potential benefits, further research, validation, and practical implementation are necessary to assess its real-world impact on patient care, safety, and overall healthcare outcomes.

Medical imaging and diagnostics: High-speed data transfer at 100 Gbps (12.5 Gbytes/s) could facilitate rapid transmission of medical images, such as CT scans, PET (positron-emission tomography), MRIs, or ultrasound images, between different systems or departments within the hospital. This would allow for faster interpretation and analysis of critical medical data, aiding in the diagnosis and treatment of patients in the ICU. The current capacity for different Imaging modalities is shown in Table 2.

Real-time monitoring and telemetry: In the ICU, patients are often connected to various monitoring devices that continuously measure vital signs, such as heart rate, blood pressure, and oxygen saturation. With a high data transfer rate like 100 Gbps (12.5 Gbytes/s), the collected data can be transmitted in real time, enabling healthcare professionals to monitor and respond to changes in the patient's condition promptly. This could support more effective patient mana

Telemedicine and remote consultations: With the ability to transmit large amounts of data quickly, a high-speed connection at 100 Gbps could facilitate telemedicine applications in the ICU. For instance, doctors or specialists located remotely could have real-time access to patient data, video feeds, and diagnostic images, allowing them to provide expert consultations without physically being present in the ICU.

Research and data analytics: In an ICU research setting, where large amounts of data are collected for analysis and research purposes, a high-speed connection can facilitate the transfer of data to research systems or cloud-based platforms. This would support advanced data analytics, machine learning algorithms, and research initiatives aimed at improving ICU care and patient outcomes.

Medical Imaging and Health Big data: Can be transferred, analyzed and compared against imaging model tools utilizing AI, Machine, deep learning and augmented reality technologies. Fiber optic communication and optical medical imaging techniques can be investigated as well but fiber requires fixed infrastructure; cables need to be laid between devices and systems. Not suitable for dynamic environments requiring mobility or flexibility. On the other hand, mm-Wave Technology is completely wireless, making it highly adaptable for environments where flexibility and movement are crucial, like ICUs. Reduces cable clutter, improving patient comfort and operational efficiency. Ideal for fast, localized data sharing, such as between medical devices or from a patient monitor to a central server.

Big data analysis in the health sector can reduce treatment costs prevent diseases and improve overall quality of life. Big data refers to the large amount of information generated by digitization. Medical researchers can use large amounts of data, i.e. 12.5 Gbytes/s, which can be transferred wirelessly over a second on treatment plans and recovery rates for i.e. cancer patients to find the trends and treatments that have the highest success rates in the real world. Radiologists no longer need to look at images, but will need to analyze the results of algorithms that will inevitably study and remember more images than they could in a lifetime.

Effective communication and data exchange is necessary to control those infected and to manage critical situations. Research data shows that information technology can reduce the frequency of errors of various types and possibly the frequency of side effects associated with them. The main categories of strategies to prevent mistakes and side effects include tools that can improve communication, and make knowledge more accessible. This provides basic information, facilitates calculations, performs real-time checks, monitoring and provides decision support. The data are visual images of the inner body that can be created in various ways (e.g., X-ray, ultrasound, CT, magnetic resonance and positron emission tomography), collected for diagnostic identification. Visual images are usually interpreted by a radiologist, emergency doctors, or cardiologists. Diagnostics analytics can find the root-causes, identify image anomalies, filtering and correlation of big health data.

Regulatory considerations: The use of specific frequency bands for wireless communication is subject to regulatory requirements and spectrum allocation. Compliance with relevant regulations and obtaining the necessary licenses would be necessary for the deployment.

Technical feasibility: While millimeter-wave frequencies offer high data rates, they also have limitations in terms of signal propagation and range. The deployment of such systems would require careful consideration of the infrastructure, antenna design, and potential challenges related to signal attenuation and interference within the ICU environment.

Integration and interoperability: Seamless integration with existing healthcare systems, medical devices, and IT infrastructure within the ICU is crucial for successful deployment. Compatibility, interoperability, and data security considerations should be addressed to ensure efficient and secure data exchange.

Cost and practicality: Deploying advanced wireless systems can involve significant costs, including equipment, installation, maintenance, and training. While initial costs for deploying 60 GHz mmWave technology in ICUs can be high, the potential for long-term savings through improved patient outcomes, reduced complications, and lower consumable usage makes the technology a promising investment. For generalization, continued innovation and pilot studies to refine costs and demonstrate economic value will be essential.

Training: Integrating mmWave technology into ICUs requires a multi-disciplinary approach to training and workforce development. While clinical staff need basic operational knowledge, technical teams require specialized skills to manage and troubleshoot the system. By incorporating simulation-based training, certification programs, and ongoing professional development, hospitals can ensure that their workforce is equipped to operate mmWave systems efficiently and safely. Proper planning for manpower and training will be critical to achieving the technology's full potential in improving patient care.

Psychological and sociological factors that influence clinical decision-making: A deeper understanding of diagnostic errors requires a multifaceted approach that goes beyond technical shortcomings and considers the psychological and sociological factors that influence clinical decision-making. Addressing cognitive biases, managing physician workload, ensuring equitable access to medical resources, and fostering a supportive and collaborative healthcare environment are all critical steps in reducing diagnostic errors. By addressing the root causes of these errors—many of which stem from the complex interplay between human psychology, organizational structures, and societal inequities—we can create a more effective and reliable healthcare system, ultimately improving patient outcomes and reducing the incidence of diagnostic mistakes.

In this paper we show the investigation of the delay spread (latency) in the ICU channel, which provided a maximum delay spread of 50 ns and a maximum mean excess delay of 9.2 ns. The required bit energy in relation to the noise was estimated to take a predetermined probability of a bit error. We found based on the recorded delay spread values for the smart ICU’s requirements are completely resolved providing excellent latency values allowing 100 Gbps (100024 Mb/s) in a 1-10 m short distance wireless throughput. A 100 MB MRI scan can be transmitted in approximately 0.008 seconds. A 1 GB scan would take approximately 0.08 seconds. This capability could revolutionize healthcare, enabling real-time remote diagnostics and comparisons with AI models, even in large-scale systems.

Fast diagnosis and fast treatment will significantly reduce human losses and permanent disabilities at ICU’s due to diagnostics errors. This experiment is the ‘first of its kind’ for an ICU application scenario at these frequencies. The results of the study will be very valuable for the medical society and the general public healthcare systems. The author suggests timely deployment of such a system at the 60 GHz band in ICUs. It will reduce significantly human losses permanent disabilities and prolong stay in ICU’s at a number around 5% per year in respect to diagnostics errors. These findings will be compelling to researchers working in this field. The paper through a real time experiment resolves the technical difficulties on the growing and expanding emergency care needs in terms of speed, computation capability, fast wireless communication, big data analytics and massive data transmission.

mmWave technology offers a transformative approach to preventing diagnostic errors in critical care. By providing precise, non-invasive, and real-time monitoring, this innovation enhances patient safety and supports better clinical outcomes. Future research should focus on refining the technology, addressing implementation challenges, and exploring its potential across diverse healthcare environments. We anticipated that our study to be a starting point for more sophisticated research in detecting and preventing diagnostics errors in primary care along with AI, machine learning, IoT and high computation in terms of mm-Wave wireless transmission.

Quality of research has to do with confidence in estimates, no limitations and of the benefits and risks for human lives. With respect to diagnostic errors, relatively little attention and means to support research are given. Future research should be aimed at a prospective assessment of the prevalence and impact of diagnostic errors and possible strategies to address them. Prospective studies are crucial to validate the clinical and operational benefits of wireless big data transmission in ICUs. Combining randomized controlled trials, observational studies, and advanced data analytics can provide robust evidence to determine whether this technology genuinely improves patient care and outcomes.

This research study, apparatus and experiment took place when the author was with the University of Glamorgan, Department of Electronics and Information Technology, Wales, United Kingdom. Special thanks go to my ex-colleague, Professor Migdad Al-Nuaimi for his valuable advices.

| 1. | Harris E. Misdiagnosis Might Harm up to 800 000 US Patients Annually. JAMA. 2023;330:586. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Newman-Toker DE, Pronovost PJ. Diagnostic errors--the next frontier for patient safety. JAMA. 2009;301:1060-1062. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 320] [Cited by in RCA: 280] [Article Influence: 16.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Custer JW, Winters BD, Goode V, Robinson KA, Yang T, Pronovost PJ, Newman-Toker DE. Diagnostic errors in the pediatric and neonatal ICU: a systematic review. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2015;16:29-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Winters B, Custer J, Galvagno SM Jr, Colantuoni E, Kapoor SG, Lee H, Goode V, Robinson K, Nakhasi A, Pronovost P, Newman-Toker D. Diagnostic errors in the intensive care unit: a systematic review of autopsy studies. BMJ Qual Saf. 2012;21:894-902. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 225] [Cited by in RCA: 189] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (34)] |

| 5. | Parvez I, Rahmati A, Guvenc I, Sarwat AI, Dai H. A Survey on Low Latency Towards 5G: RAN, Core Network and Caching Solutions. IEEE Commun Surv Tutorials. 2018;20:3098-3130. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 6. | Kelly FP. Network routing. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, 1991; 337: 343-367. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Corson MS, Laroia R, Li J, Park V, Richardson T, Tsirtsis G. Toward proximity- aware internetworking. IEEE Wireless Commun. 2010;17:26-33. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 8. | European Emergency Number Association (EENA-112), V1, August 2019. Available from: https://eena.org/wp-content/uploads/EENA_AnnualReport_2019.pdf. |

| 9. | Diagnostic Errors in the Emergency Department: A Systematic Review [Internet]. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2022 Dec. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Sittig DF, Singh H. A new sociotechnical model for studying health information technology in complex adaptive healthcare systems. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010;19 Suppl 3:i68-i74. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 498] [Cited by in RCA: 452] [Article Influence: 28.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Reducing diagnostic errors in the ICU. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2018. Available from: https://healthmanagement.org/c/icu/news/reducing-diagnostic-errors-in-the-icu. |

| 12. | Bergl PA, Nanchal RS, Singh H. Diagnostic Error in the Critically III: Defining the Problem and Exploring Next Steps to Advance Intensive Care Unit Safety. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2018;15:903-907. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Committee on Diagnostic Error in Health Care. In: Balogh EP, Miller BT, Ball JR, editors. The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US), 2015. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 14. | Diagnostic Errors: Technical Series on Safer Primary Care ISBN 978-92-4-151163-6 © World Health Organization 2016. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/311679697_Diagnostic_Errors_Technical_Series_on_Safer_Primary_Care_Geneva_World_Health_Organization_2016_Licence_CC_BY-NC-SA_30_IGO. |

| 15. | Singh H, Giardina TD, Meyer AN, Forjuoh SN, Reis MD, Thomas EJ. Types and origins of diagnostic errors in primary care settings. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:418-425. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 309] [Cited by in RCA: 381] [Article Influence: 29.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Singh H, Meyer AN, Thomas EJ. The frequency of diagnostic errors in outpatient care: estimations from three large observational studies involving US adult populations. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23:727-731. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 296] [Cited by in RCA: 428] [Article Influence: 35.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 17. | Noro R, Hubaux JP, Meuli R, Laurini RN, Patthey R. Real-time telediagnosis of radiological images through an asynchronous transfer mode network: the ARTeMeD project. J Digit Imaging. 1997;10:116-121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Singh H, Naik AD, Rao R, Petersen LA. Reducing diagnostic errors through effective communication: harnessing the power of information technology. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:489-494. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Graber ML. The incidence of diagnostic error in medicine. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22 Suppl 2:ii21-ii27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 383] [Cited by in RCA: 385] [Article Influence: 29.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 20. | Gandhi TK, Kachalia A, Thomas EJ, Puopolo AL, Yoon C, Brennan TA, Studdert DM. Missed and delayed diagnoses in the ambulatory setting: a study of closed malpractice claims. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:488-496. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 425] [Cited by in RCA: 434] [Article Influence: 21.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 21. | Singh H, Arora HS, Vij MS, Rao R, Khan MM, Petersen LA. Communication outcomes of critical imaging results in a computerized notification system. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2007;14:459-466. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Brenner RJ, Bartholomew L. Communication errors in radiology: a liability cost analysis. J Am Coll Radiol. 2005;2:428-431. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Schiff GD. Introduction: Communicating critical test results. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2005;31:63-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 24. | Ash JS, Berg M, Coiera E. Some unintended consequences of information technology in health care: the nature of patient care information system-related errors. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2004;11:104-112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1028] [Cited by in RCA: 876] [Article Influence: 39.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Kuperman GJ, Teich JM, Tanasijevic MJ, Ma'Luf N, Rittenberg E, Jha A, Fiskio J, Winkelman J, Bates DW. Improving response to critical laboratory results with automation: results of a randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1999;6:512-522. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 148] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Weiner M, Biondich P. The influence of information technology on patient-physician relationships. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21 Suppl 1:S35-S39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Bates DW, Gawande AA. Improving safety with information technology. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2526-2534. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 906] [Cited by in RCA: 764] [Article Influence: 33.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Raab SS, Grzybicki DM. Quality in cancer diagnosis. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60:139-165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 29. | Raab SS, Grzybicki DM, Janosky JE, Zarbo RJ, Meier FA, Jensen C, Geyer SJ. Clinical impact and frequency of anatomic pathology errors in cancer diagnoses. Cancer. 2005;104:2205-2213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Novis DA. Detecting and preventing the occurrence of errors in the practices of laboratory medicine and anatomic pathology: 15 years' experience with the College of American Pathologists' Q-PROBES and Q-TRACKS programs. Clin Lab Med. 2004;24:965-978. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 31. | Carey M, Boyes AW, Bryant J, Turon H, Clinton-McHarg T, Sanson-Fisher R. The Patient Perspective on Errors in Cancer Care: Results of a Cross-Sectional Survey. J Patient Saf. 2019;15:322-327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Thammasitboon S, Thammasitboon S, Singhal G. Diagnosing diagnostic error. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2013;43:227-231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Kostopoulou O, Rosen A, Round T, Wright E, Douiri A, Delaney B. Early diagnostic suggestions improve accuracy of GPs: a randomised controlled trial using computer-simulated patients. Br J Gen Pract. 2015;65:e49-e54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Dandu RV. Storage media for computers in radiology. Indian J Radiol Imaging. 2008;18:287-289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Pinto A, Acampora C, Pinto F, Kourdioukova E, Romano L, Verstraete K. Learning from diagnostic errors: a good way to improve education in radiology. Eur J Radiol. 2011;78:372-376. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 36. | Siamarou A, Al-nuaimi M. Multipath delay spread and signal level measurements for indoor wireless radio channels at 62.4 GHz. IEEE VTS 53rd Vehicular Technology Conference, Spring 2001. Proceedings (Cat. No.01CH37202). 1:454-458. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 37. | Siamarou AG, Theofilakos P, Kanatas AG. 60 GHz Wireless Links for HDTV: Channel Characterization and Error Performance Evaluation. PIERC. 2013;36:195-205. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 38. | Siamarou A. Broadband wireless local-area networks at millimeter waves around 60 GHz. IEEE Antennas Propag Mag. 2003;45:177-181. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 39. | Siamarou AG, Al-nuaimi M. A Wideband Frequency-Domain Channel-Sounding System and Delay-Spread Measurements at the License-Free 57- to 64-GHz Band. IEEE Trans Instrum Meas. 2010;59:519-526. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 40. | Siamarou AG. A Swept-Frequency Wideband Channel Sounding System at the 63.4-64.4 GHz Band with 1 ns Time-Resolution. Int J Infrared Milli Waves. 2008;29:1186-1195. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 41. | Siamarou A. The 57-64-GHz Unlicensed Band: Correlation Bandwidth Estimation and Comparison for Time-Variant and Static Channels. IEEE Antennas and Wireless Propagation Letters, USA, 2008; 393-395. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 42. | Siamarou AG. Preventing Medical Errors Using mm-Wave Technology; a Letter to the Editor. Arch Acad Emerg Med. 2023;11:e64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/