Published online Dec 9, 2025. doi: 10.5492/wjccm.v14.i4.103782

Revised: April 1, 2025

Accepted: June 7, 2025

Published online: December 9, 2025

Processing time: 364 Days and 0.2 Hours

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a significant public health issue, leading to long-term neurological impairments. Current treatments offer limited recovery, particularly in restoring lost functions. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes (MSCdE) have shown potential for promoting neuroprotection and regeneration. This study evaluates the safety and efficacy of MSCdE therapy in TBI patients.

To evaluate the safety and efficacy of MSCdE therapy in TBI patients.

Five patients (mean age 27.00 ± 4.06 years) with TBI from combat injuries were treated with six rounds of MSCdE therapy (3 mL intrathecally and 3 mL intramuscularly per round). The patients were followed for one year. Adverse events were assessed using the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 5.0 (CTCAE v5.0), and functional outcomes were evaluated with the functional independence measure (FIM), Modified Ashworth Scale (MAS), and Karnofsky Performance Scale (KPS).

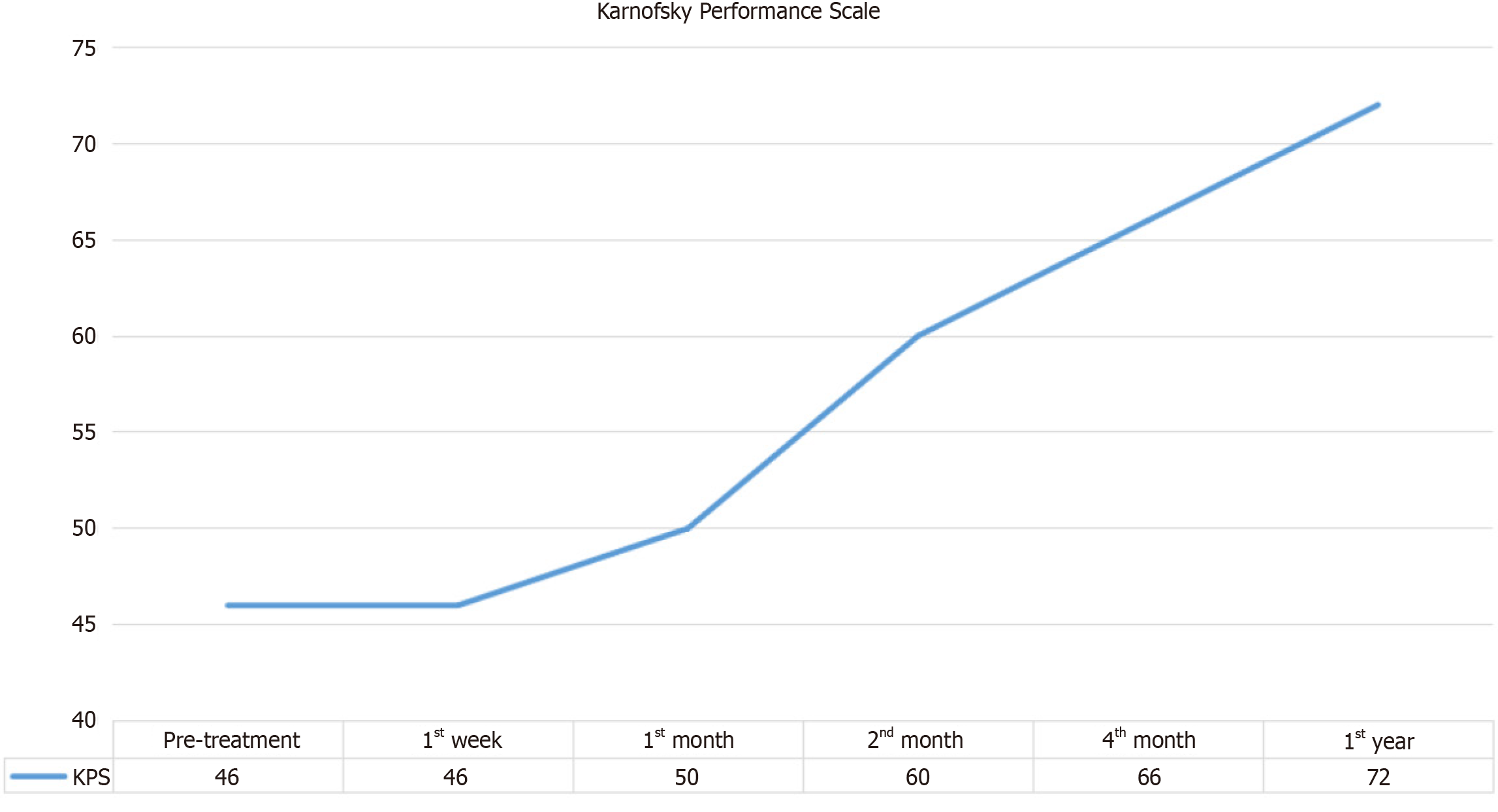

No serious adverse events occurred, and only mild side effects [subfebrile fever (37.5 °C-37.9 °C), pain] were reported (CTCAE Grade 1). FIM motor scores improved significantly (46.20 ± 16.39 to 64.20 ± 18.20, P < 0.01), and FIM cognitive scores also showed significant improvement (30.60 ± 4.56 to 34.00 ± 1.41, P < 0.001). While MAS scores improved (right/left: 4.60/3.60 to 2.20/1.60), these changes were not statistically significant (P > 0.05), possibly due to low baseline spasticity. KPS scores significantly improved (46.00 ± 11.40 to 72.00 ± 8.37, P < 0.001), indicating enhanced overall functional status and quality of life.

MSCdE therapy is safe and effective in improving motor function, cognition, and quality of life in TBI patients. Larger, controlled trials are needed to further validate these findings and optimize MSCdE therapy for TBI treatment.

Core Tip: Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes (MSCdE) therapy shows promise for traumatic brain injury (TBI) patients, with significant improvements in motor and cognitive function reflected in functional independence measure scores. The treatment was well tolerated, with mild, temporary side effects such as subfebrile fever and pain, and no serious adverse events reported. Enhanced Karnofsky Performance Scale scores suggest improved quality of life and functional status, supporting its potential for long-term recovery. While spasticity improvement was observed, it was not statistically significant, possibly due to mild baseline spasticity. These findings support MSCdE therapy as a potential treatment for TBI, warranting further validation through larger randomized controlled trials.

- Citation: Kabatas S, Civelek E, Savrunlu EC, Kaplan N, Akkoc T, Küçükçakır N, Bozkurt M, Karaöz E. Efficacy and safety of exosomes from Wharton’s Jelly-derived mesenchymal stem cells in traumatic brain injury. World J Crit Care Med 2025; 14(4): 103782

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3141/full/v14/i4/103782.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5492/wjccm.v14.i4.103782

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) remains a significant global health concern, characterized by brain dysfunction caused by external forces. With an estimated 69 million cases occurring annually worldwide, TBI disproportionately affects low- and middle-income countries, where 90% of injuries occur due to traffic accidents, falls, and violence[1]. The incidence of TBI-related hospitalizations in high-income countries approaches 1 per 1000 individuals each year, reflecting its substantial public health burden[2]. Socioeconomic consequences are severe, including lifelong disability, reduced quality of life for survivors, and annual costs exceeding $76 billion in the United States alone[3].

Current TBI treatments primarily focus on acute care and symptomatic management but offer limited solutions for secondary injury mechanisms that complicate recovery[4]. Advances in regenerative medicine, particularly mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) therapies, present new therapeutic avenues[5].

The therapeutic potential of mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes (MSCdE) lies in their cargo of neuroprotective miRNAs, proteins, and lipids that modulate key injury mechanisms[6]. Following primary mechanical injury, TBI progresses through secondary phases involving glutamate excitotoxicity mediated by excessive N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor activation and impaired astrocytic glutamate uptake[7]. MSCdEs address this by upregulating glutamate transporter GLT-1 expression and restoring calcium homeostasis, as demonstrated in ischemic brain injury models[8]. Concurrently, MSCdEs combat oxidative stress by delivering antioxidant enzymes like superoxide dismutase and catalase, while their miRNA cargo (e.g., miR-21, miR-146a) suppresses nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase activity and activates the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway[9].

The inflammatory component of TBI, characterized by microglial activation and pro-inflammatory cytokine release (tumor necrosis factor-alpha, interleukin-1 beta), is attenuated through MSCdE-mediated transfer of anti-inflammatory miRNAs like miR-124 and modulation of NF-κB signaling[10]. Furthermore, MSCdEs exhibit potent anti-apoptotic effects by regulating Bcl-2 family proteins and inhibiting caspase-3 activation[11]. These multifaceted mechanisms synergize to preserve blood-brain barrier integrity, reduce neuronal loss, and promote functional recovery in preclinical TBI models[12]. Compared to whole-cell therapies, MSCdEs offer superior safety profiles and can be engineered to enhance target specificity, making them particularly attractive for clinical translation[13].

This study aims to evaluate the safety and efficacy of MSCdE therapy in combat-related TBI patients. We administered exosomes intrathecally and intramuscularly, followed by comprehensive functional and health assessments. Our findings contribute to the growing body of evidence on the clinical utility of exosome-based therapies for TBI.

This Phase I study was a prospective, longitudinal trial carried out at Romatem Bursa and Kocaeli Hospitals. The study design aimed to evaluate the safety and preliminary efficacy of MSCdE therapy in patients with TBI. Approval was obtained from the institutional ethics board (protocol number: 22122023.1), ensuring adherence to ethical standards and patient safety. Legal representatives of each patient were informed about the study procedures, and informed consent was obtained in line with the Declaration of Helsinki guidelines. Prior to treatment, general information was collected, including age, gender, duration of time since TBI, and relevant medical history, to provide a baseline for evaluation.

The study included five patients aged 24 to 34 years (mean age 27 ± 4.06 years), all of whom sustained TBI due to combat injuries. The study included five patients aged 24 to 34 years (mean age 27 ± 4.06 years), all of whom sustained TBI due to combat injuries. The injuries were classified based on the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) and imaging findings [computed tomography/magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)] as follows:

Severity: All patients had moderate to severe TBI (GCS scores 6–12 at initial injury).

Chronicity: Patients were in the chronic phase of TBI (8–18 months post-injury), with persistent motor and cognitive deficits despite prior rehabilitation.

Each patient had previously undergone rehabilitation for six to twelve months with limited functional improvement. Treatment histories revealed that muscle spasticity was a persistent issue for these patients; in one case, botulinum toxin injections were administered to manage muscle spasms but provided only temporary relief. MSCdE therapy was initiated 8 to 18 months after TBI onset, allowing an evaluation of MSCdE’s potential as a secondary therapy in chronic-phase TBI.

All patient data were anonymized and coded to ensure confidentiality. Personal identifiers were removed from datasets, and access was restricted to the research team. Electronic records were stored on password-protected hospital servers compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act and the General Data Protection Regulation standards. Only aggregated data were used for analysis and publication. Legal representatives provided written consent for data use in research, with the understanding that individual privacy would be protected at all stages.

Eligible patients had TBI confirmed by imaging studies, including computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging, and detailed neurological evaluations. Inclusion criteria were established to ensure that only patients with TBI without other central nervous system pathologies were enrolled. Exclusion criteria included the presence of any other central nervous system lesion, such as neoplastic lesions, and chronic systemic diseases requiring long-term medication, which could potentially interfere with the MSCdE therapy’s outcomes. Before treatment whole central nervous MRIs were performed. In addition, chest X-rays and electrocardiograms were seen before each round, and electrolytes, kidney and liver functions were monitored with routine blood tests. Each patient underwent an interdisciplinary assessment involving neurosurgeons and physical medicine and rehabilitation specialists to confirm eligibility and establish baseline neurological status.

The MSCdE treatment protocol involved a combination of intrathecal (i.t.) and intramuscular (i.m.) injections, strategically timed to maximize therapeutic potential while maintaining patient safety. Prior to each procedure, patients were screened to ensure clinical stability, with checks for contraindications to sedoanesthesia, such as underlying internal medicine concerns or active infections. Intramuscular injections were conducted under ultrasound guidance to precisely target affected muscle groups, particularly those with the highest degree of spasticity or functional impairment. Each patient received six rounds of MSCdE therapy; in each round, 30 billion exosomes were administered via i.t. injection and another 30 billion via i.m. injection. The detailed administration schedule is presented in Table 1.

| Rounds | Route | Exosomes from Wharton’s Jelly-derived mesenchymal stem cells |

| Round 1 | IT | 30 × 109 exosomes in 3 mL |

| IM | 30 × 109 exosomes in 3 mL | |

| Round 2 (week 2) | IT | 30 × 109 exosomes in 3 mL |

| IM | 30 × 109 exosomes in 3 mL | |

| Round 3 (week 6) | IT | 30 × 109 exosomes in 3 mL |

| IM | 30 × 109 exosomes in 3 mL | |

| Round 4 (week 10) | IT | 30 × 109 exosomes in 3 mL |

| IM | 30 × 109 exosomes in 3 mL | |

| Round 5 (week 14) | IT | 30 × 109 exosomes in 3 mL |

| IM | 30 × 109 exosomes in 3 mL | |

| Round 6 (week 18) | IT | 30 × 109 exosomes in 3 mL |

| IM | 30 × 109 exosomes in 3 mL |

MSC were cultured with a serum-free medium to avoid the contamination of protein that will come from serum to produce a concentrated and adequate amount of exosome. Exosomes were made containing 5% CO2 at 37 °C for 24-36 hours then the serum-free medium was collected. Centrifuge at 300 g for 10 minutes to discard the remaining cells. In the last step, the cells are thrown away and the supernatant is used for the following step. In the second step, the supernatant was centrifuged at 5000 g for 20 minutes and in the third step, the supernatant was centrifuged at 10000 g for 60. The final supernatant is ultra-centrifuged at 110000 g for 120 minutes and collected pellet that the small vesicles that correspond to exosomes from the pellet. The pellets in each tube are dissolved in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and vortexed. The pellets are collected in one tube and centrifuged at 110000 g for 120 minutes. Depending on the pellet amount is dissolved in 1000 µL PBS and can be stored at -80 °C for 1 month and at -152 °C for 1 year[14].

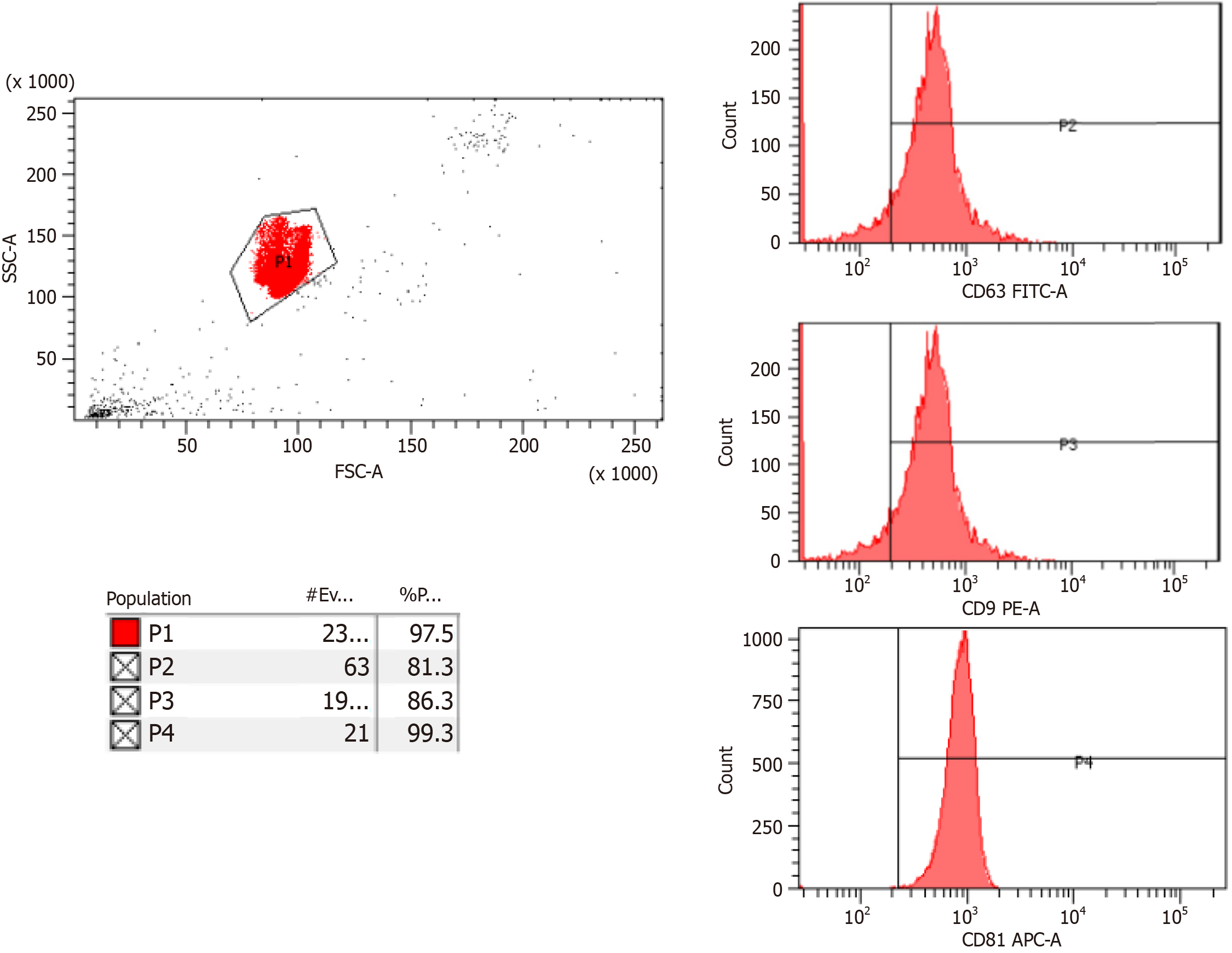

The isolated exosomes were labelled with CD81, CD9 and CD63 and the characterization data were acquired with Flow Cytometry analysis which are tetraspanins such as CD9, CD63, and CD81 (Figure 1). 5-10 billion exosomes and negative samples are prepared, 4% sulfate latex (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.) is added and incubated overnight at +4 °C. 100 mmol/L glycine is added to the samples and incubated at room temperature. Then, centrifugation is performed at 5000 rpm for 5 minutes. The supernatant is removed PBS is added, and the centrifugation process is repeated. The supernatant is removed, and antibodies prepared with antibody diluent are added. Incubation is done in the dark at room temperature. PBS is added to the samples whose incubation is completed and centrifuged at 300 g for 5 minutes. The upper phase is removed and suspended with 500 uL PBS and read on the flow device (BD FACSCanto II, United States).

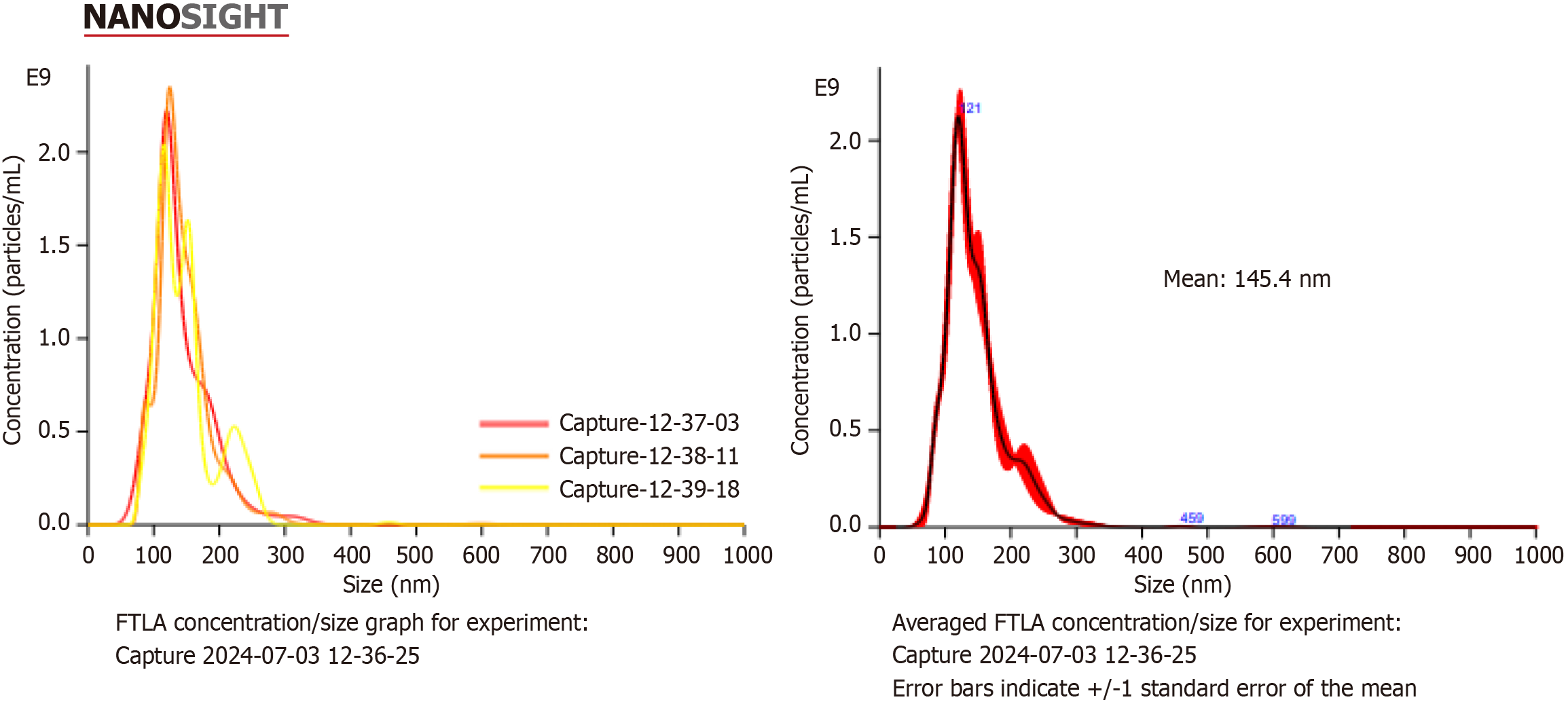

The size of the exosomes should be 50-220 nm on average. The size and quantity of exosomes are determined with the nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) test. Exosomes are suspended with a pipette. Exosomes samples are diluted 50 × or 100 × and transferred to a 2 mL cryovial. PBS is added to make the final volume 1 mL. The prepared sample is loaded into the device with a 1 mL insulin syringe and the reading is taken. The settings of the NTA device (Malvern Panalytical NanoSight NS300, United Kingdom) are adjusted and recorded (Figure 2).

Pre-treatment assessment: A comprehensive baseline assessment was performed before treatment initiation. This evaluation was carried out by a multidisciplinary team composed of specialists in neurology, rehabilitation, and internal medicine. Functional capabilities and quality of life were measured using the functional independence measure (FIM) Scale and the Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) Scale, which allowed a standardized assessment of daily living skills and functional capacity. Spasticity, a key complication in TBI, was quantified using the Modified Ashworth Scale (MAS), which rated muscle tone on a graded scale. These pre-treatment scores served as a baseline for post-treatment compa

Rigorous safety monitoring was conducted throughout the treatment period and during follow-up. Patients were assessed for signs of infection, including fever, elevated C-reactive protein levels, and leukocytosis. In addition, potential anesthesia-related complications, wound infections, allergic reactions, and shock were closely observed to mitigate risks during and after MSCdE administration. Short-term safety assessments were conducted during the first two weeks post-procedure, and long-term safety monitoring continued over a one-year period to evaluate any delayed effects of MSCdE therapy. This extended follow-up included checks for infections, tumor formation, neuropathic pain, and signs of neurological deterioration. All observed adverse effects were recorded and classified per the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 5.0 (CTCAE v5.0) to maintain consistent and thorough documentation of patient safety.

Follow-up assessments evaluated the impact of MSCdE therapy on neurological and functional recovery over time. Spasticity was measured at each follow-up point using the MAS, and quality of life was reassessed with the FIM and KPS Scales. Functional recovery was assessed at various time points to track gradual improvements. Additional follow-up assessments included monitoring for neuropathic pain, urinary tract infections, secondary infections, and pressure ulcers, ensuring a comprehensive understanding of patient progress and any possible secondary complications.

To assess the efficacy of MSCdE therapy, changes in FIM, MA, and KPS scores were analyzed using nonparametric tests. First, the Friedman Test was employed to detect any significant differences across multiple time points, specifically between pre-treatment and post-treatment scores at 1 week, 1 month, 2 months, 4 months, and 12 months. For cases where the Friedman Test indicated significant changes, the Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test was conducted to perform pairwise comparisons between specific time points, allowing identification of specific intervals with statistically significant improvements. All statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS software package, and significance was set at P < 0.05 for all tests. This approach ensured rigorous evaluation of MSCdE’s potential therapeutic impact on functional and neurological outcomes in TBI patients.

The administration of MSCdE therapy was well-tolerated by all patients, with no major adverse effects observed. Five patients reported mild, short-term side effects, including low-grade fever, moderate headache, and muscle soreness at the injection sites. These were classified as Grade 1 events per CTCAE v5.0, indicating minor, temporary symptoms that did not significantly impact daily activities. No serious or lasting complications, such as infections, immune reactions, or cancer, were noted over the one-year follow-up period, highlighting a positive safety profile for MSCdE therapy in this cohort.

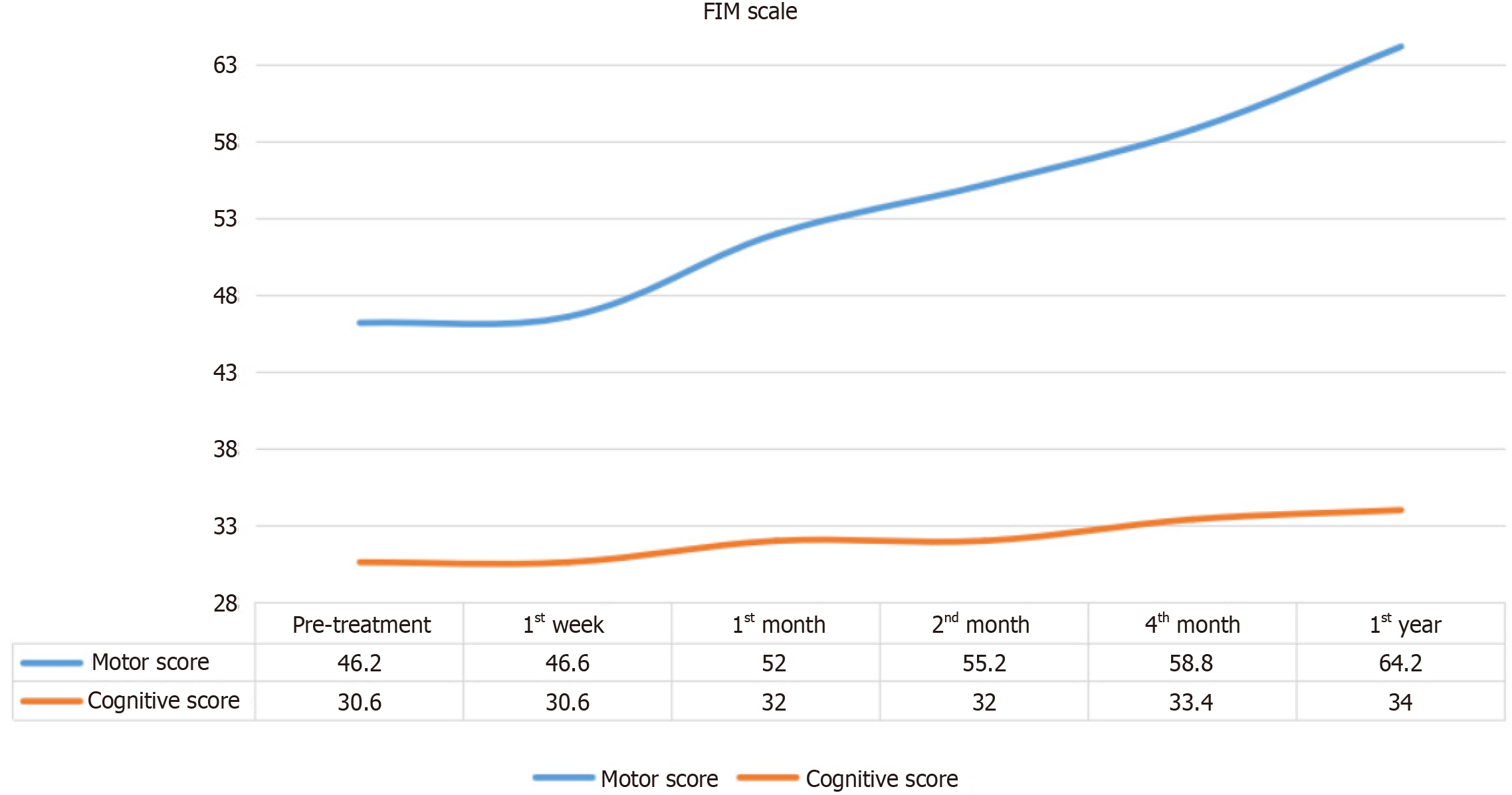

Changes in FIM Motor and Cognitive Scores over time are shown in Figure 3. FIM Motor Scores gradually improved starting from the first week post-treatment, with cognitive improvements observed as well, though to a lesser degree.

Table 2 shows the Friedman Test results, which reveal statistically significant changes in FIM Motor Scores over time (χ2 = 24.883, P < 0.001). The Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Test identified specific intervals of significant motor improvement, particularly between baseline and post-treatment scores at the 1st month (z = -2.032, P = 0.042), 2nd month (z = -2.023, P = 0.043), 4th month (z = -2.023, P = 0.042), and 12th month (z = -2.041, P = 0.041). No significant difference was seen between baseline and the 1st week (z = -1.000, P = 0.317), indicating a delayed onset of motor function improvement.

| n | Mean | SD | Mean rank | χ2 | df | P value | |

| Preoperative | 5 | 46.20 | 16.39 | 1.40 | 24.883 | 5 | 0.000 |

| Postoperative 1st week | 5 | 46.60 | 16.23 | 1.60 | |||

| Postoperative 1st month | 5 | 52.00 | 17.01 | 3.00 | |||

| Postoperative 2nd month | 5 | 55.20 | 17.81 | 4.00 | |||

| Postoperative 4th month | 5 | 58.80 | 18.95 | 5.00 | |||

| Postoperative 12th month | 5 | 64.20 | 18.90 | 6.00 |

Table 3 shows the Friedman Test results for FIM Cognitive Scores, indicating significant changes across time points

| n | Mean | SD | Mean rank | χ2 | df | P value | |

| Preoperative | 5 | 30.60 | 4.56 | 2.30 | 14.898 | 5 | 0.011 |

| Postoperative 1st week | 5 | 30.60 | 4.56 | 2.30 | |||

| Postoperative 1st month | 5 | 32.00 | 3.46 | 3.50 | |||

| Postoperative 2nd month | 5 | 32.00 | 3.46 | 3.50 | |||

| Postoperative 4th month | 5 | 33.40 | 2.30 | 4.50 | |||

| Postoperative 12th month | 5 | 34.00 | 1.41 | 4.90 |

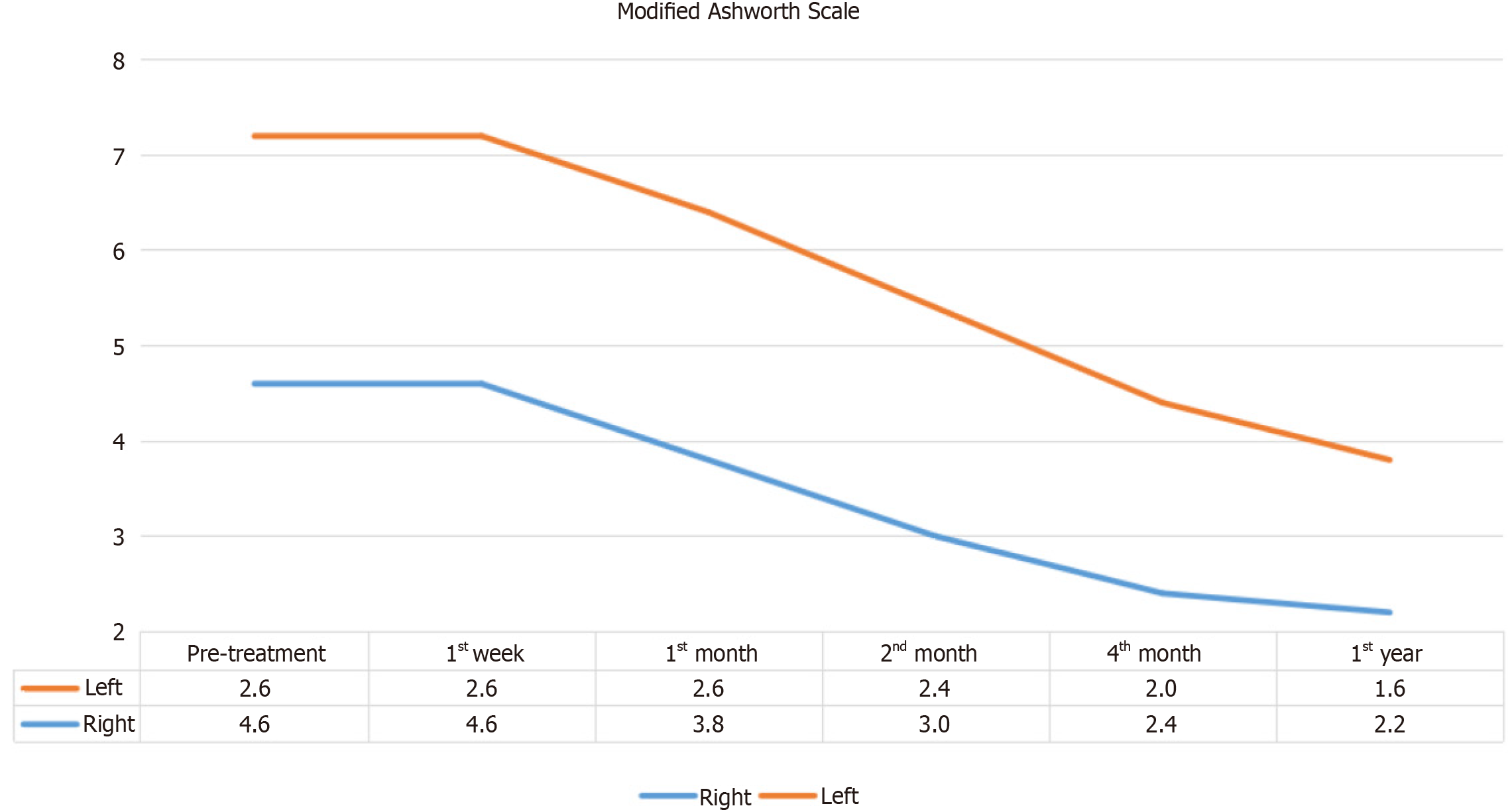

The MAS results, depicted in Figure 4, showed a decrease in muscle spasticity on the right side beginning from the first week post-treatment. While this suggests a beneficial trend, Table 4 indicates that the reduction in MAS scores on the right side was not statistically significant (χ2 = 9.688, P > 0.05). Similarly, Table 5 shows no statistically significant changes in MAS scores on the left side over the study period, suggesting that while MSCdE therapy may help reduce spasticity, further studies with larger sample sizes are needed to confirm these findings.

| n | Mean | SD | Mean rank | χ2 | df | P value | |

| Preoperative | 5 | 4.60 | 7.40 | 4.30 | 9.688 | 5 | 0.085 |

| Postoperative 1st week | 5 | 4.60 | 7.40 | 4.30 | |||

| Postoperative 1st month | 5 | 3.80 | 6.50 | 3.70 | |||

| Postoperative 2nd month | 5 | 3.00 | 5.20 | 3.10 | |||

| Postoperative 4th month | 5 | 2.40 | 3.91 | 2.90 | |||

| Postoperative 12th month | 5 | 2.20 | 3.49 | 2.70 |

| n | Mean | SD | Mean rank | χ2 | df | P value | |

| Preoperative | 5 | 3.60 | 4.93 | 4.30 | 9.615 | 5 | 0.087 |

| Postoperative 1st week | 5 | 3.60 | 4.93 | 4.30 | |||

| Postoperative 1st month | 5 | 2.60 | 3.58 | 3.60 | |||

| Postoperative 2nd month | 5 | 2.40 | 3.29 | 3.30 | |||

| Postoperative 4th month | 5 | 2.00 | 2.83 | 2.90 | |||

| Postoperative 12th month | 5 | 1.60 | 2.19 | 2.60 |

Karnofsky performance scale (KPS) results, which measure patients' functional status and ability to perform daily activities, showed an upward trend post-treatment, as shown in Figure 5. Improvements were noted from the first week and were maintained throughout the follow-up period.

Table 6 displays the Friedman Test results for the KPS, indicating statistically significant differences over time (χ2 = 23.526, P < 0.001). The Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Test revealed significant improvements in functional status at the 2nd month (z = -2.070, P = 0.038), 4th month (z = -2.060, P = 0.039), and 12th month post-treatment (z = -2.070, P = 0.038). However, no significant changes were observed between baseline and the 1st week (z = 0.000, P = 1.000) or the 1st month (z = -1.414, P = 0.157), suggesting that improvements in functional status were evident only after the initial treatment period.

| n | Mean | SD | Mean rank | χ2 | df | P value | |

| Preoperative | 5 | 46.00 | 11.402 | 1.80 | 23.526 | 5 | 0.000 |

| Postoperative 1st week | 5 | 46.00 | 11.402 | 1.80 | |||

| Postoperative 1st month | 5 | 50.00 | 7.071 | 2.50 | |||

| Postoperative 2nd month | 5 | 60.00 | 12.247 | 4.10 | |||

| Postoperative 4th month | 5 | 66.00 | 11.402 | 5.00 | |||

| Postoperative 12th month | 5 | 72.00 | 8.367 | 5.80 |

This study aimed to evaluate the safety and efficacy of MSCdE therapy in patients with TBI. Our findings demonstrate that MSCdE therapy has a favorable safety profile, with only minor, temporary adverse effects, such as low-grade fever, moderate headache, and muscle soreness, all classified as Grade 1 according to CTCAE v5.0. These results are consistent with previous research suggesting that MSC-based therapies are generally well-tolerated in neurological conditions, likely due to the immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory properties of MSCs, which help reduce the risk of adverse reactions[15-18].

Regarding functional outcomes, significant improvements were observed in FIM Motor Scores over a one-year period, particularly from the first month to the twelfth month post-intervention. This finding is consistent with previous literature indicating that MSC-based therapies can enhance motor recovery in TBI patients through regenerative properties such as tissue repair, neuroprotection, and cell survival support[5,19]. The lack of significant changes in FIM Motor Scores during the first week is likely due to the time required for MSCdE therapy to manifest its full effects, as suggested by other studies showing delayed benefits of MSC-based interventions[19].

In contrast, FIM Cognitive Scores did not show statistically significant improvements. This can be attributed to the fact that only two patients had baseline cognitive scores below 30, with a range from a minimum of 5 to a maximum of 35. Although these patients demonstrated notable improvements in cognitive function, the small sample size limited the statistical power to detect significant changes. These results suggest that while MSCdE therapy might offer cognitive benefits, these effects may be less pronounced or more variable than improvements in motor function. Mixed results regarding cognitive recovery in MSC-based therapy studies are well documented and are likely due to the complex nature of cognitive recovery in TBI, which is influenced by various factors such as injury location, severity, and individual characteristics[20].

Although there were trends toward improvement in spasticity, as measured by MAS scores, these changes did not reach statistical significance. Some individual patients showed notable improvements in spasticity, but with only two patients experiencing significant baseline spasticity, the statistical power was insufficient to detect changes across the entire cohort. Similar challenges in evaluating spasticity have been reported in other studies, which suggest that more sensitive tools may be necessary to detect meaningful changes in spasticity after MSC-based therapies[21,22].

We also observed significant improvements in KPS scores from the first week to the twelfth month. This result aligns with existing literature, which suggests that MSC-based therapies can enhance overall functional capacity and quality of life in TBI patients[23]. The improvements in KPS suggest that MSCdE therapy may positively impact the daily functioning and well-being of TBI patients, supporting the long-term benefits of MSCdE therapy for patients recovering from brain injury.

The positive outcomes observed in this study are consistent with recent research on MSC-derived exosomes in neurodegenerative and traumatic brain injuries[24]. The significant improvements in motor function and quality of life align with findings from preclinical and early-phase clinical trials showing that MSCdE therapy promotes neuroprotection, synaptic plasticity, and neurogenesis[25,26]. However, the variability in cognitive improvements and spasticity highlights the complexity of TBI recovery and the need for further research to fully understand the factors influencing therapeutic outcomes. While MSCdE therapy appears promising, its effects can be heterogeneous, likely due to factors such as injury severity, patient characteristics, and the timing of treatment[27,28].

This study has several limitations, including a small sample size and variability in patient responses, which may have influenced the statistical outcomes, particularly in cognitive function and spasticity measures. Future studies should focus on larger, more diverse cohorts and consider extended follow-up periods to confirm these findings and gain a better understanding of MSCdE therapy’s effects. Additionally, more sensitive and specific assessment tools for cognitive function and spasticity should be employed to better capture the potential benefits of MSCdE therapy in these areas. Furthermore, investigating different dosing regimens, routes of administration, and the timing of MSCdE therapy may help identify optimal treatment protocols and patient subgroups most likely to benefit from MSCdE therapy.

Further research should also aim to explore the underlying biological mechanisms by which MSCdE therapy exerts its therapeutic effects in TBI, such as neurogenesis, synaptic plasticity, and inflammation modulation. Studies focusing on optimizing administration schedules, dosage, and timing of MSCdE therapy could maximize its therapeutic impact. Identifying patient subgroups that would benefit most from MSCdE therapy will also be critical for advancing this field and ensuring more personalized, effective treatments.

In conclusion, MSCdE therapy demonstrates promising potential for improving motor function, quality of life, and overall recovery in TBI patients. Although certain outcomes, such as spasticity and cognitive function, did not show significant statistical changes, individual patient improvements suggest that MSCdE therapy can provide meaningful benefits in these areas. These findings support the continued exploration of MSCdE therapy as a novel therapeutic approach for TBI. Further research is needed to optimize treatment protocols, explore the mechanisms underlying the observed improvements, and validate these results in larger, controlled studies. With ongoing research, MSCdE therapy may become a valuable addition to the therapeutic options available for patients with TBI, offering significant potential to improve their recovery and quality of life.

| 1. | Dewan MC, Rattani A, Gupta S, Baticulon RE, Hung YC, Punchak M, Agrawal A, Adeleye AO, Shrime MG, Rubiano AM, Rosenfeld JV, Park KB. Estimating the global incidence of traumatic brain injury. J Neurosurg. 2019;130:1080-1097. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1255] [Cited by in RCA: 1751] [Article Influence: 250.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Maas AIR, Menon DK, Manley GT, Abrams M, Åkerlund C, Andelic N, Aries M, Bashford T, Bell MJ, Bodien YG, Brett BL, Büki A, Chesnut RM, Citerio G, Clark D, Clasby B, Cooper DJ, Czeiter E, Czosnyka M, Dams-O'Connor K, De Keyser V, Diaz-Arrastia R, Ercole A, van Essen TA, Falvey É, Ferguson AR, Figaji A, Fitzgerald M, Foreman B, Gantner D, Gao G, Giacino J, Gravesteijn B, Guiza F, Gupta D, Gurnell M, Haagsma JA, Hammond FM, Hawryluk G, Hutchinson P, van der Jagt M, Jain S, Jain S, Jiang JY, Kent H, Kolias A, Kompanje EJO, Lecky F, Lingsma HF, Maegele M, Majdan M, Markowitz A, McCrea M, Meyfroidt G, Mikolić A, Mondello S, Mukherjee P, Nelson D, Nelson LD, Newcombe V, Okonkwo D, Orešič M, Peul W, Pisică D, Polinder S, Ponsford J, Puybasset L, Raj R, Robba C, Røe C, Rosand J, Schueler P, Sharp DJ, Smielewski P, Stein MB, von Steinbüchel N, Stewart W, Steyerberg EW, Stocchetti N, Temkin N, Tenovuo O, Theadom A, Thomas I, Espin AT, Turgeon AF, Unterberg A, Van Praag D, van Veen E, Verheyden J, Vyvere TV, Wang KKW, Wiegers EJA, Williams WH, Wilson L, Wisniewski SR, Younsi A, Yue JK, Yuh EL, Zeiler FA, Zeldovich M, Zemek R; InTBIR Participants and Investigators. Traumatic brain injury: progress and challenges in prevention, clinical care, and research. Lancet Neurol. 2022;21:1004-1060. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 855] [Article Influence: 213.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Surveillance Report of Traumatic Brain Injury-related Emergency Department Visits, Hospitalizations, and Deaths. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/traumatic-brain-injury/media/pdfs/TBI-surveillance-report-2018-2019-508.pdf. |

| 4. | Smith DH, Johnson VE, Stewart W. Chronic neuropathologies of single and repetitive TBI: substrates of dementia? Nat Rev Neurol. 2013;9:211-221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 432] [Cited by in RCA: 576] [Article Influence: 44.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Zhang Y, Chopp M, Meng Y, Katakowski M, Xin H, Mahmood A, Xiong Y. Effect of exosomes derived from multipluripotent mesenchymal stromal cells on functional recovery and neurovascular plasticity in rats after traumatic brain injury. J Neurosurg. 2015;122:856-867. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 613] [Cited by in RCA: 561] [Article Influence: 51.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Zhang B, Yin Y, Lai RC, Tan SS, Choo AB, Lim SK. Mesenchymal stem cells secrete immunologically active exosomes. Stem Cells Dev. 2014;23:1233-1244. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 431] [Cited by in RCA: 531] [Article Influence: 44.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Lai TW, Zhang S, Wang YT. Excitotoxicity and stroke: identifying novel targets for neuroprotection. Prog Neurobiol. 2014;115:157-188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 666] [Cited by in RCA: 882] [Article Influence: 67.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Wu KJ, Yu SJ, Chiang CW, Lee YW, Yen BL, Hsu CS, Kuo LW, Wang Y. Wharton' jelly mesenchymal stromal cell therapy for ischemic brain injury. Brain Circ. 2018;4:124-127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Xin H, Li Y, Cui Y, Yang JJ, Zhang ZG, Chopp M. Systemic administration of exosomes released from mesenchymal stromal cells promote functional recovery and neurovascular plasticity after stroke in rats. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2013;33:1711-1715. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 838] [Cited by in RCA: 784] [Article Influence: 60.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Li D, Zhang P, Yao X, Li H, Shen H, Li X, Wu J, Lu X. Exosomes Derived From miR-133b-Modified Mesenchymal Stem Cells Promote Recovery After Spinal Cord Injury. Front Neurosci. 2018;12:845. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 18.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Otero-Ortega L, Laso-García F, Gómez-de Frutos MD, Rodríguez-Frutos B, Pascual-Guerra J, Fuentes B, Díez-Tejedor E, Gutiérrez-Fernández M. White Matter Repair After Extracellular Vesicles Administration in an Experimental Animal Model of Subcortical Stroke. Sci Rep. 2017;7:44433. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 155] [Article Influence: 17.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Williams AM, Dennahy IS, Bhatti UF, Halaweish I, Xiong Y, Chang P, Nikolian VC, Chtraklin K, Brown J, Zhang Y, Zhang ZG, Chopp M, Buller B, Alam HB. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes Provide Neuroprotection and Improve Long-Term Neurologic Outcomes in a Swine Model of Traumatic Brain Injury and Hemorrhagic Shock. J Neurotrauma. 2019;36:54-60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Wiklander OPB, Brennan MÁ, Lötvall J, Breakefield XO, El Andaloussi S. Advances in therapeutic applications of extracellular vesicles. Sci Transl Med. 2019;11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 521] [Cited by in RCA: 776] [Article Influence: 110.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (15)] |

| 14. | Civelek E, Kabatas S, Savrunlu EC, Diren F, Kaplan N, Ofluoğlu D, Karaöz E. Effects of exosomes from mesenchymal stem cells on functional recovery of a patient with total radial nerve injury: A pilot study. World J Stem Cells. 2024;16:19-32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kabatas S, Civelek E, Boyalı O, Sezen GB, Ozdemir O, Bahar-Ozdemir Y, Kaplan N, Savrunlu EC, Karaöz E. Safety and efficiency of Wharton's Jelly-derived mesenchymal stem cell administration in patients with traumatic brain injury: First results of a phase I study. World J Stem Cells. 2024;16:641-655. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (71)] |

| 16. | Kabataş S, Civelek E, Kaplan N, Savrunlu EC, Sezen GB, Chasan M, Can H, Genç A, Akyuva Y, Boyalı O, Diren F, Karaoz E. Phase I study on the safety and preliminary efficacy of allogeneic mesenchymal stem cells in hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. World J Exp Med. 2021;11:17-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kabatas S, Civelek E, Savrunlu EC, Kaplan N, Boyalı O, Diren F, Can H, Genç A, Akkoç T, Karaöz E. Feasibility of allogeneic mesenchymal stem cells in pediatric hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy: Phase I study. World J Stem Cells. 2021;13:470-484. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 18. | Boyalı O, Kabatas S, Civelek E, Ozdemir O, Bahar-Ozdemir Y, Kaplan N, Savrunlu EC, Karaöz E. Allogeneic mesenchymal stem cells may be a viable treatment modality in cerebral palsy. World J Clin Cases. 2024;12:1585-1596. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Williams AM, Bhatti UF, Brown JF, Biesterveld BE, Kathawate RG, Graham NJ, Chtraklin K, Siddiqui AZ, Dekker SE, Andjelkovic A, Higgins GA, Buller B, Alam HB. Early single-dose treatment with exosomes provides neuroprotection and improves blood-brain barrier integrity in swine model of traumatic brain injury and hemorrhagic shock. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2020;88:207-218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Zhang ZG, Buller B, Chopp M. Exosomes - beyond stem cells for restorative therapy in stroke and neurological injury. Nat Rev Neurol. 2019;15:193-203. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 260] [Cited by in RCA: 413] [Article Influence: 59.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Li Y, Yang YY, Ren JL, Xu F, Chen FM, Li A. Exosomes secreted by stem cells from human exfoliated deciduous teeth contribute to functional recovery after traumatic brain injury by shifting microglia M1/M2 polarization in rats. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2017;8:198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 163] [Article Influence: 18.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Papa S, Vismara I, Mariani A, Barilani M, Rimondo S, De Paola M, Panini N, Erba E, Mauri E, Rossi F, Forloni G, Lazzari L, Veglianese P. Mesenchymal stem cells encapsulated into biomimetic hydrogel scaffold gradually release CCL2 chemokine in situ preserving cytoarchitecture and promoting functional recovery in spinal cord injury. J Control Release. 2018;278:49-56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Cox CS Jr, Hetz RA, Liao GP, Aertker BM, Ewing-Cobbs L, Juranek J, Savitz SI, Jackson ML, Romanowska-Pawliczek AM, Triolo F, Dash PK, Pedroza C, Lee DA, Worth L, Aisiku IP, Choi HA, Holcomb JB, Kitagawa RS. Treatment of Severe Adult Traumatic Brain Injury Using Bone Marrow Mononuclear Cells. Stem Cells. 2017;35:1065-1079. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Xin H, Katakowski M, Wang F, Qian JY, Liu XS, Ali MM, Buller B, Zhang ZG, Chopp M. MicroRNA cluster miR-17-92 Cluster in Exosomes Enhance Neuroplasticity and Functional Recovery After Stroke in Rats. Stroke. 2017;48:747-753. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 401] [Cited by in RCA: 452] [Article Influence: 50.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Doeppner TR, Herz J, Görgens A, Schlechter J, Ludwig AK, Radtke S, de Miroschedji K, Horn PA, Giebel B, Hermann DM. Extracellular Vesicles Improve Post-Stroke Neuroregeneration and Prevent Postischemic Immunosuppression. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2015;4:1131-1143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 432] [Cited by in RCA: 625] [Article Influence: 56.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Webb RL, Kaiser EE, Jurgielewicz BJ, Spellicy S, Scoville SL, Thompson TA, Swetenburg RL, Hess DC, West FD, Stice SL. Human Neural Stem Cell Extracellular Vesicles Improve Recovery in a Porcine Model of Ischemic Stroke. Stroke. 2018;49:1248-1256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 175] [Article Influence: 21.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Chen KH, Chen CH, Wallace CG, Yuen CM, Kao GS, Chen YL, Shao PL, Chen YL, Chai HT, Lin KC, Liu CF, Chang HW, Lee MS, Yip HK. Intravenous administration of xenogenic adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells (ADMSC) and ADMSC-derived exosomes markedly reduced brain infarct volume and preserved neurological function in rat after acute ischemic stroke. Oncotarget. 2016;7:74537-74556. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in RCA: 197] [Article Influence: 24.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Lankford KL, Arroyo EJ, Nazimek K, Bryniarski K, Askenase PW, Kocsis JD. Intravenously delivered mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes target M2-type macrophages in the injured spinal cord. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0190358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 154] [Cited by in RCA: 166] [Article Influence: 20.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/