Published online Jan 18, 2026. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v17.i1.112625

Revised: September 12, 2025

Accepted: November 21, 2025

Published online: January 18, 2026

Processing time: 160 Days and 17.8 Hours

There has been an increasing focus in recent years on health-care disparities. Studies investigating return to work (RTW) or sports are often performed in large, urban areas. Relatively few studies have investigated rates of return to farming or other heavy labor that is of interest to patients in rural areas.

To evaluate the literature regarding RTW in farming or heavy labor after orthopedic hip, knee, or shoulder surgery.

A search was performed in the PubMed and EMBASE databases using Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines. Studies were included if they reported patients employed in farming or heavy labor, RTW rates after orthopedic surgery of the hip, knee, or shoulder, and had a minimum 6-month follow-up. A meta-analysis of proportions using a random-effects model was performed on three single-arm observational studies to estimate the pooled RTW rate following arthroscopic shoulder surgery.

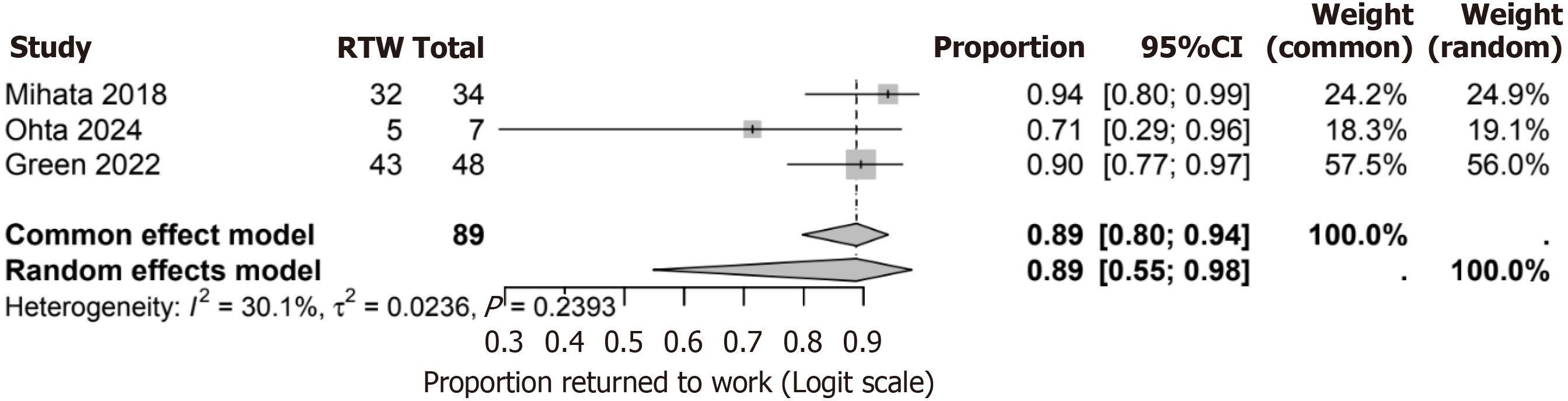

Ten studies were included, and 101 farmers were identified among 440 total patients. One study involved hip surgery, two studies involved knee surgery, and seven studies involved shoulder surgery. RTW rates across studies varied by type of surgery and follow-up interval, ranging from 24% to 100%. The RTW rate was only 53.6% at 1 year following total hip arthroplasty. No studies investigated RTW in farmers following total knee arthroplasty. Among non-comparative studies, meta-analysis revealed a pooled RTW rate of 89% following arthroscopic shoulder surgery, with low heterogeneity (I2 = 30.1%). Among comparative studies, one study reported significantly higher RTW odds for patients undergoing anatomic total shoulder arthroplasty compared to reverse shoulder arthroplasty (odds ratio = 5.45). Overall, surgical intervention for shoulder pathology was associated with a high likelihood of RTW across multiple techniques, with particularly favorable outcomes for anatomic total shoulder arthroplasty.

This systematic review highlights the high rates of RTW in farmers and heavy laborers after shoulder surgery. However, our findings also underscore the need for more rural-specific research to guide patient counseling, rehabilitation expectations, and shared decision-making in this underserved population, particularly for orthopedic surgery of the hip and knee.

Core Tip: This systematic review evaluates return to work outcomes among farmers and heavy laborers following orthopedic surgeries of the hip, knee, and shoulder. The study identifies a high return to work rate after shoulder procedures, especially anatomic total shoulder arthroplasty, and reveals a significant lack of data for hip and knee surgeries in rural labor-intensive populations. These findings highlight a critical gap in orthopedic outcomes research and underscore the need for targeted studies to inform surgical decision-making and postoperative rehabilitation in physically demanding occupations.

- Citation: Lehtonen E, Kambli R, Mandalia K, Beall K, Shah SS. Return to farming after orthopedic surgery: A systematic review. World J Orthop 2026; 17(1): 112625

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v17/i1/112625.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v17.i1.112625

Orthopedic patients often consider the impact of surgery on their ability to work in surgical decision-making and timing. For younger patients, the ability to return to work (RTW) can represent an important measure of surgical success. For surgeons, there is a constant and evolving need for research pertaining to the timing and ability for patients to RTW, particularly as surgical techniques evolve. This is no simple task, as the demands of each surgery and occupation are unique, and the expected timing or ability to return must be individualized for each patient.

There has been an increasing focus in recent years on health-care disparities[1]. In regard to disparities between rural and urban patient populations, it has been reported that patients in rural areas can experience limited access to care and worse outcomes compared to their urban counterparts[2-6]. Additionally, rural patients tend to be older, experience higher rates of diabetes, obesity, and osteoarthritis (OA), and are more likely to be uninsured or insured through Medicaid[1]. One study found that in 2018, only 33.5% of rural Unted States counties had access to an orthopedic surgeon[4]. As a result of these healthcare desserts, rural patients are often under-represented in the orthopedic literature. According to the United States Department of Agriculture, 14% of the Unted States population resides in non-metropolitan areas, while farmers represent about 2% of Unted States families[7]. Direct on farm jobs in the Unted States employed an estimated 2.6 million workers in 2022, compared to an estimated 15000 Unted States professional athletes[8,9]. Like athletes, a farmer’s livelihood is dependent on his or her physical abilities, and the work is often seasonal in nature. While there is an abundance of studies investigating rates of return to sport or work after orthopedic surgery, these studies are often performed in large, urban areas. Relatively limited attention has been paid to rates of return to farming or other heavy labor that is of interest to rural patients. The purpose of this review is to evaluate the available evidence regarding the rate of RTW in farming or agricultural labor after orthopedic hip, knee, or shoulder surgery.

The systematic review was performed following Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines.

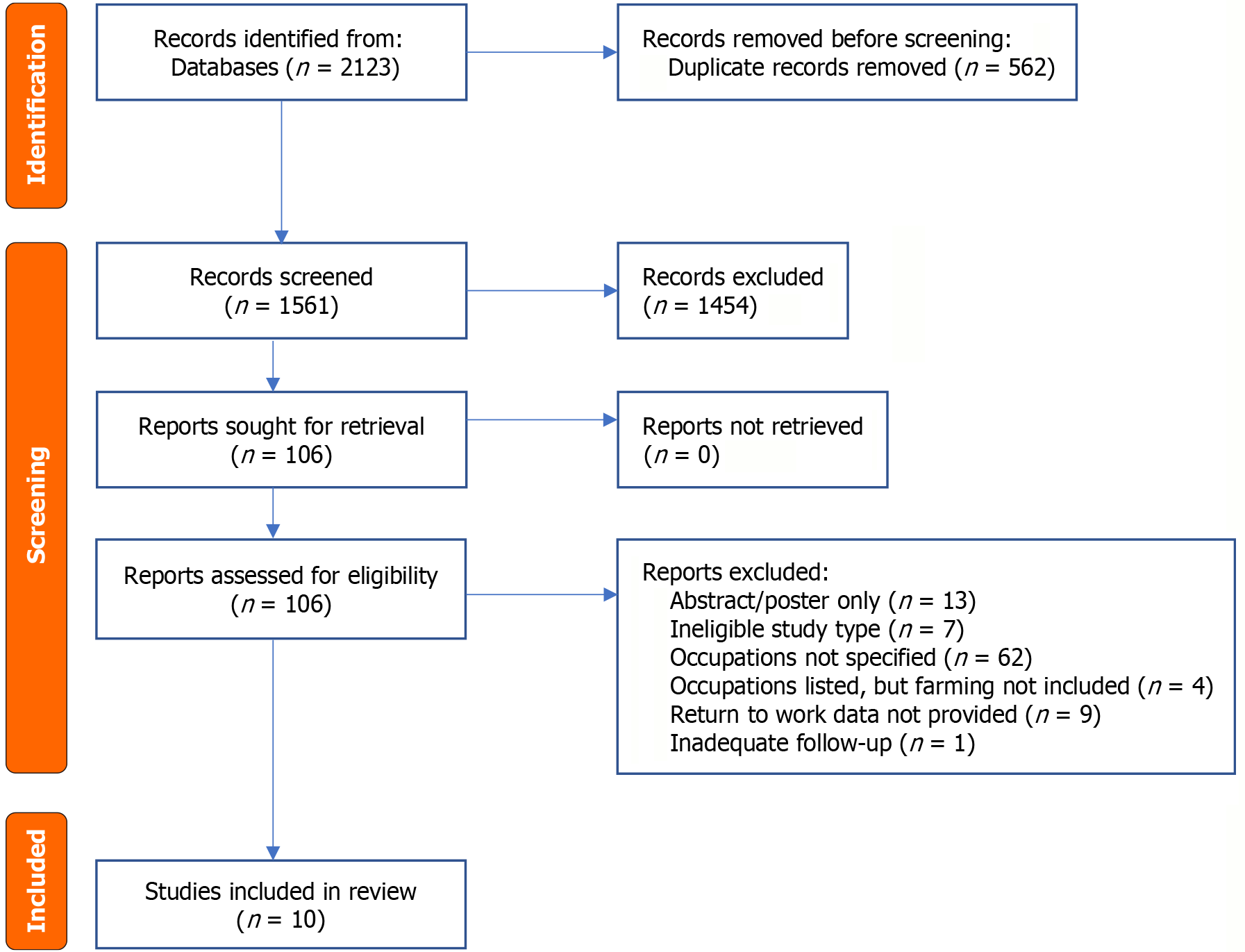

The search was performed in the PubMed and EMBASE databases in January 2025. The search terms used were: (“RTW” or return), and (farm* or agricultur* or rural or labor*), and (shoulder or “rotator cuff” or glenoid or humer* or clavic* or scapula or knee or tibia or femur or hip or joint or labr* or menisc* or ligament or tendon), and (surg* or arthroscop* or repair or reconstruction or arthroplasty or replacement or hemiarthroplasty or resurfacing or osteotomy or ORIF or fixation). The search resulted in 2123 total titles. After removal of 562 duplicates, a total of 1561 unique titles were screened for relevance.

The titles and abstracts were reviewed to determine the relevance of the study by two independent investigators (Lehtonen E and Kambli R). After irrelevant titles and abstracts were excluded, the full texts of 106 studies were reviewed for inclusion.

Study eligibility was assessed independently by two investigators. Studies were included if they reported the RTW rates in farming or agricultural work following any orthopedic hip, knee, or shoulder surgery. Only studies that include farmers or agricultural workers were considered eligible for inclusion. The following types of studies were excluded: (1) Case reports; (2) Reviews, editorials; (3) Cadaver or biomechanical studies; (4) Studies with < 6 months of patient follow-up; (5) Papers published in a language other than English and unable to be translated; (6) Studies that failed to report occupation; and (7) Studies in which the RTW rate could not be calculated. A total of 10 studies were deemed eligible following application of inclusion and exclusion criteria (Figure 1).

Two investigators extracted relevant data from the studies. Discrepancies between selected studies are settled by the senior author. RTW rates were reported as a percentage, when available. Ability to return to full or limited duty was compared, if available. If RTW rates were not reported separately for farming or agricultural work, the most specific pooled data was used. For example, if farmers are included in a study but RTW rates are pooled by level of demand, the pooled data for the group that includes farmers was used. Timing of return to full duty was also reported, if available. The methodological index for non-randomized studies (MINORS) criteria was used for appraisal of bias in the individual studies.

A summary of the included studies is provided in Table 1. Seven studies were retrospective case series, while the remaining 3 were retrospective comparative studies. Across all included studies, a total of 101 farmers were identified among a total of 440 patients. One study involved hip surgery[10], two studies involved surgery around the knee[11,12], and seven studies involved the shoulder[13-19]. There were 3 case series by a single author[15-17] involving the same patient cohort at 1 year, 4 years, 5 years, and 10 years following superior capsular reconstruction. MINORS criteria of the included studies are reported in Table 2. In general, the quality of included studies was moderate to low. Prospective calculation of study size, loss to follow up, and unbiased assessment of outcomes were the most common reasons for downgraded scoring.

| Ref. | Design | Years of Study | Location | Inclusion/exclusion | Comparison groups | Patients per group | Follow-up | Outcomes | Study type |

| Gowd et al[13], 2019 | Retrospective cohort | Not specified (mean follow-up 69 months) | United States | Patients undergoing hemiarthroplasty or aTSA for OA; excluded if incomplete follow-up | Hemi RR vs aTSA | Hemi RR: 25 (2 farmers) aTSA: 28 | Mean 69 months | Return to heavy labor, ASES scores, satisfaction | Comparative; shoulder arthroplasty |

| Mihata et al[16], 2019 | Retrospective case series | SCR cohort followed to 5 years | Japan | Patients with irreparable rotator cuff tears; excluded prior surgery or Goutallier > 3 | None | 30 (5 farmers in labor subgroup) | 5 years | Return to work, shoulder function scores | Single-arm; SCR |

| Shimada et al[14], 2023 | Retrospective cohort | 2012-2017 | Japan | Patients undergoing aTSA or RSA for OA; excluded if revision or incomplete data | aTSA vs RSA | aTSA: 64 (3 farmers) RSA: 68 (12 farmers) | Mean 3-4 years | Return to sport/work, ROM, satisfaction | Comparative; shoulder arthroplasty |

| Mihata et al[17], 2025 | Retrospective case series | 10-year follow-up study | Japan | Patients with irreparable rotator cuff tears undergoing SCR | None | 36 (9 farmers) | 10 years | Graft integrity, RTW, ASES scores | Single-arm; SCR |

| Carlson [11], 2005 | Retrospective case series | 1985-2002 (approximately) | United States | Posterior bicondylar tibial plateau fractures treated with ORIF | None | 5 (1 farmer) | 13 months average | Return to work, ROM, complications | Single-arm; ORIF |

| Pop et al[10], 2016 | Retrospective survey | 2003-2014 | Poland | Patients with THA, rural background, working age, 10-year follow-up | None | 32 (6 farmers) | 10 years | Employment status, Harris Hip Score, health status | Single-arm; THA |

| Ohta et al[18], 2024 | Retrospective cohort | Not stated | Japan | Patients undergoing ASCR for IRCT | Pseudoparalysis vs non-pseudoparalysis, and graft healed vs not | 49 (2 farmers) | Minimum 2 years (mean approximately 34 months) | RTW, ROM, graft integrity, constant, JOA | Single-arm; SCR |

| Mihata et al[15], 2018 | Retrospective cohort | Follow-up to 4 years | Japan | Patients undergoing SCR; outcomes stratified by physical activity | Heavy labors vs others | 100 (9 farmers in heavy labor group) | 4 years | RTW, sports, function scores | Single-arm; SCR |

| Green et al[19], 2022 | Retrospective case series | 2015-2019 | United States | Manual laborers aged 50-60 years with full-thickness RCT, no workers’ comp | None | 48 (3 farmers) | 34 months average | RTW, time to return, SANE, ASES, VAS | Single-arm; RCR |

| Korovessis et al[12], 1999 | Prospective cohort | 1983-1985 surgeries; 5-12 years follow-up | Greece | Agricultural workers with medial OA | Mittelmeier vs AO closing wedge osteotomy | M: 35, AO: 28 (all farmers) | Mean 11 years | RTW, knee axis, satisfaction, TKA conversion | Comparative; HTO |

| MINORS criterion | Korovessis et al[12], 1999 | Carlson [11], 2005 | Pop et al[10], 2016 | Mihata et al[15], 2018 | Gowd et al[13], 2019 | Mihata et al[16], 2019 | Shimada et al[14], 2023 | Ohta et al[18], 2024 | Mihata et al[17], 2025 | Green et al[19], 2022 |

| Cleary stated aim | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Inclusion of consecutive patients | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Prospective collection of data | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| Endpoints appropriate to the aim of the study | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Unbiased assessment of the study endpoint | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Follow-up period appropriate to the arm of the study | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Loss to follow-up < 5% | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Prospective calculation of the study size | 0 | - | - | 0 | 0 | - | 0 | 0 | - | - |

| Adequate control group | 2 | - | - | 2 | 2 | - | 2 | 2 | - | - |

| Contemporary groups | 2 | - | - | 2 | 2 | - | 2 | 2 | - | - |

| Baseline equivalence of groups | 1 | - | - | 1 | 2 | - | 1 | 2 | - | - |

| Adequate statistical analyses | 1 | - | - | 2 | 2 | - | 2 | 2 | - | - |

| Total score | 17 | 8 | 8 | 19 | 19 | 11 | 18 | 18 | 11 | 11 |

Only one eligible study discussed occupational activity at 10 years following total hip arthroplasty[10]. This was a Polish, single-institution case series with a total of 32 patients. Inclusion criteria required that patients be of working age at the time of surgery, have at least 10 years of follow up, and agree to participate. Participants completed a survey with qu

There were no eligible studies evaluating return to farming after total knee arthroplasty (TKA). One study examined medium to long term results following two techniques for performing high tibial osteotomy for the treatment of medial compartment OA[12]. Only patients employed in agriculture were included. Sixty three patients were treated with either a two-level Mittelmeier osteotomy (35 patients) or an association for the study of internal fixation closing wedge osteotomy using an L plate (28 patients), with an average follow up of 11 years. Postoperatively, 56/63 (89%) patients were able to return to their previous agricultural activity at 8 months to 12 months after surgery. Knee function scores were closely correlated to returning to work, as 56/63 (89%) patients achieved good or excellent scores, while 59/63 (94%) reported being satisfied or very satisfied with the surgery. Twelve patients (19%) required TKA at 6-10 years post-surgery due to OA progression.

A retrospective series reported posterior bicondylar tibial plateau fractures treated with dual incision open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) with an average of 13 months follow up[11]. The study included 5 patients that underwent ORIF, including one 48 years old male farmer, who sustained the injury while falling from a truck bed. This patient was able to return to his previous employment, despite suffering complications including deep vein thrombosis and superficial wound dehiscence, as well as a 45 degrees flexion contracture, which was resolved with physical therapy. Three of five (60%) patients returned to their prior employment in heavy manual jobs - two heavy laborers and one farmer.

Studies by Mihata et al[15] investigated the short-term, mid-term, and long-term outcomes of arthroscopic superior capsule reconstruction (aSCR) using fascia lata autograft for irreparable rotator cuff tears. The 2018 study evaluated return to sports and physical work among 100 patients with 4 years follow up. Of these, 34 performed physically demanding jobs, including 9 farmers. All patients in physically demanding jobs returned to work (34/34), although one farmer and one mechanic did so at a reduced capacity[15]. The 2019 study evaluated 1-year and 5-year outcomes in 30 patients. There were 12 patients with physically demanding jobs, including 5 farmers. At 5 years, 11/12 (92%) heavy duty workers remained employed[16]. The 2025 study followed 36 patients for up to 10 years, including 17 heavy laborers and 9 farmers. This found that at 10 years, 15/17 (88%) heavy laborers remained employed. The graft survival rate was also high (89% at 5-10 years), and graft healing prevented the progression of cuff tear arthropathy[17]. The authors concluded that aSCR leads to significant improvements in shoulder function and pain relief, which were maintained over time in most patients, including farmers[15-17].

Ohta et al[18] similarly reported on aSCR using fascia lata in 49 patients (2 farmers) with irreparable rotator cuff tears with a minimum 2-year follow-up. The authors reported that 16/18 (89%) patients were able to return to their previous work, including 2/2 (100%) of farmers. Among those engaged in heavy labor, only 3/5 were able to return to full duty, while 2/5 changed to less demanding jobs. Return to farming occurred on average 4.5 months after surgery[18].

Green et al[19] investigated return to manual labor, including farming, after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair in 48 patients (3 farmers) with a minimum 2-year follow-up. Patients were included if they were aged 50-60 years and employed in a job requiring heavy lifting or prolonged heavy use of the shoulder. The authors found that 34/48 (77%) of patients overall returned to their pre-injury work, including 3/3 (100%) dairy farmers. Average time to RTW among all patients was 5 months (range, 4-10 months). Factors associated with a successful RTW included smaller tear size, lower preoperative pain levels, and greater early postoperative improvement[19]. Meta-analysis of these three non-comparative studies (89 patients) evaluating return to farming work within 2 years following arthroscopic surgery for treatment of rotator cuff pathology revealed a pooled RTW rate of 89%, with low heterogeneity (I2 = 30.1%) as shown in Figure 2.

Gowd et al[13] compared work-related outcomes in 53 patients (2 farmers) after hemiarthroplasty with concentric glenoid reaming (Hemi RR) and anatomic total shoulder arthroplasty (aTSA) for OA[13]. The average age was 53 years, and average follow up was 69 months. There were 25 patients treated with Hemi RR, including 2 farmers among 7 heavy duty workers. There were no farmers among 28 patients treated with aTSA, of whom 4 were employed in heavy duty jobs. Return to heavy duty work was higher in patients treated with hemi RR vs aTSA (100% vs 50%, P = 0.038). The average time to return to heavy duty work was 3.1 months and 3.0 months for Hemi RR and aTSA, respectively. Of note, patients in the aTSA group were counseled on permanent overhead lifting restrictions, while hemi RR were allowed to resume unrestricted activity.

Shimada et al[14] investigated return to sports and physical work, including farming, after anatomical (aTSA) and reverse shoulder arthroplasty (RSA)[14]. The study of 132 patients (64 aTSA, 68 RSA) included a total of 15 farmers (3 aTSA, 12 RSA). Farming was classified as a medium activity load. Authors reported that while a significant proportion of patients returned to some form of work or sport after surgery, there were limitations. The rates of complete return to medium and heavy physical work were higher in the aTSA group compared to the RSA group. For medium load, such as farming, complete return was achieved in 70% with aTSA compared with 24% with RSA (P = 0.002). Average time to return was 5.7 months and 6.7 months for aTSA and RSA, respectively. Applying random-effects model, Shimada et al[14] suggests significantly higher RTW odds for patients undergoing aTSA compared to RSA (odds ratio = 5.45).

This systematic review, encompassing ten studies and a total of 101 farmers, provides a preliminary overview of return to farming following orthopedic surgery of the hip, knee, and shoulder. The limited number of studies specifically focusing on this occupational group highlights the under-representation of farmers in orthopedic research, despite their significant contribution to the workforce and the physically demanding nature of their profession.

The single study on hip arthroplasty indicated a modest RTW rate of 53.6% at 1 year in a predominantly rural population of physical laborers, including a subset of farmers[10]. This suggests that returning to farming after hip replacement may be challenging, although the study did not provide specific details for the agricultural workers. This finding stands in contrast to broader literature, which generally reports RTW rates after total hip arthroplasty in the range of 70%-90% in the general working age population, particularly among patients with less physically demanding occupations[20]. It is unclear if these findings reflect the unique physical demands of farming and physical labor specifically or the limited access to care, including rehabilitation and postoperative support, affecting patients in rural settings.

In the knee, the evidence is sparse. One study on high tibial osteotomy reported a high return rate (89%) to agricultural work at a medium to long term follow-up, suggesting this procedure may be effective for maintaining employment in this population with medial compartment OA[12]. However, the study noted that 19% of patients went on to TKA within 6-9 years, compared to 92% 10 years arthroplasty free survival reported in other studies[21]. This may suggest higher failure rates of joint preserving osteotomy among farmers when compared to other cohorts. The case series on tibial plateau fractures included a single farmer who successfully returned to work after ORIF, highlighting the potential for return even after significant trauma, although broader conclusions cannot be drawn from a single case[11]. Notably, no studies specifically addressing return to farming after TKA met the inclusion criteria, representing a significant gap in the literature. In contrast, multiple studies have reported RTW rates of 70%-85% after TKA in general populations[20,22], although rates tend to be lower in heavy manual laborers. Given the physical intensity of farming and rural health disparities, further research is needed to clarify expected outcomes in this subgroup.

The majority of the included studies focused on shoulder surgery. For irreparable rotator cuff tears, superior capsule reconstruction (SCR) demonstrated promising results, with high rates of return to physically demanding work, including farming, reported across multiple studies[15-18]. Return to farming after SCR appears to be a realistic outcome, with some studies reporting 100% return in the small farmer cohorts. Similarly, arthroscopic rotator cuff repair in a select population of active individuals aged 50-60 years showed a 100% return rate to dairy farming, emphasizing the potential for successful return after repair in appropriately selected patients[19]. It is worth noting that SCR has largely fallen out of favor in the United States due to its technical demands, high graft cost, and mixed long-term outcomes[23,24]. Alternative procedures, such as lower trapezius tendon transfer[25] and subacromial balloon spacers[26], have gained attention as potential options for managing irreparable rotator cuff tears; however, these techniques require further evaluation, particularly regarding RTW outcomes in physically demanding professions such as farming.

In the context of shoulder arthroplasty, the findings suggest a divergence between hemiarthroplasty, anatomic and reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. Hemiarthroplasty with concentric glenoid reaming demonstrated a 100% return to heavy-duty work, which included two farmers[13]. In contrast, anatomic shoulder arthroplasty showed a 70% rate of return to medium-load activities like farming, compared to only 24% for reverse shoulder arthroplasty[14]. This difference may be attributed to patient selection, surgeon-imposed postoperative activity restrictions, and changes to shoulder biomechanics. Further research is needed to determine the most reliable treatment option for farmers with limiting glenohumeral arthritis who are hoping to RTW.

Beyond the type of major joint surgery, return to farming must also be analyzed through the lens of social determinants of health. Farmers, due to the nature of their work, face barriers to physical recovery beyond that of the average, healthy patient. These include limited geographical access to specialty surgical care and rehabilitation services, lower baseline income and insurance coverage, and fewer opportunities for job modifications[27]. Rural residents are also more likely to have lower rates of health literacy, which can affect treatment adherence and rehabilitation follow through[28]. As a result, rural residents have higher rates of comorbidities and are more likely to delay seeking care, compounding the challenges faced during the postoperative recovery period. These contextual factors significantly influence outcomes after orthopedic surgery, but are difficult to account for in literature. More granular data collection is needed to explore how geographic proximity and socioeconomic factors intersect with clinical outcomes in farming populations.

Despite these findings, several limitations warrant consideration. The overall number of farmers included across all studies is small (n = 101), limiting the statistical power and generalizability of the conclusions specifically for this population. The definition of “farming” and the specific physical demands involved were often not clearly delineated, potentially encompassing a wide range of agricultural activities with varying physical requirements. Furthermore, the heterogeneity in surgical techniques, outcome measures, and follow-up periods across the included studies makes direct comparisons challenging. The methodological quality of the included studies, as assessed by the MINORS criteria, was generally moderate to low, with common limitations including the lack of prospective sample size calculation, unclear handling of loss to follow-up, and potential for bias in outcome assessment.

This systematic review underscores the need for more rigorous and focused research on return to farming after orthopedic surgery. Future studies should aim to: (1) Specifically recruit and identify farmers within their cohorts; (2) Provide detailed descriptions of the agricultural tasks involved in their work; (3) Utilize standardized outcome measures relevant to farming activities; (4) Employ prospective study designs with adequate sample sizes; and (5) Ensure comprehensive long-term follow-up. As orthopedic surgery continues to evolve, addressing these limitations will provide more robust evidence to guide surgical decision-making and its impact on populations whose livelihood depend on physical labor. Farmers represent one such group, and their unique needs deserve more attention in surgical planning, rehabilitation, and long-term outcome research.

| 1. | Pandya NK, Wustrack R, Metz L, Ward D. Current Concepts in Orthopaedic Care Disparities. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2018;26:823-832. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Mullens CL, Ibrahim AM, Clark NM, Kunnath N, Dieleman JL, Dimick JB, Scott JW. Trends in Timely Access to High-Quality and Affordable Surgical Care in the United States. Ann Surg. 2024;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Thomas HM, Jarman MP, Mortensen S, Cooper Z, Weaver M, Harris M, Ingalls B, von Keudell A. The role of geographic disparities in outcomes after orthopaedic trauma surgery. Injury. 2023;54:453-460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Wu VS, Schmidt JE, Jella TK, Cwalina TB, Freidl SL, Pumo TJ, Kamath AF. Rural Communities in the United States Face Persistent Disparities in Access to Orthopaedic Surgical Care. Iowa Orthop J. 2023;43:15-21. [PubMed] |

| 5. | The Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research. 195 Rural Hospital Closures and Conversions. [cited 5 June 2025]. Available from: https://www.shepscenter.unc.edu/programs-projects/rural-health/rural-hospital-closures/. |

| 6. | American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. The State of Musculoskeletal Health in Rural America. [cited 5 June 2025]. Available from: https://www.aaos.org/aaosnow/2025/jan/managing/managing03/. |

| 7. | Davis JC, Cromartie J, Farrigan T, Genetin B, Sanders A, Winikoff JB. Rural America at a Glance: 2023 Edition. [cited 3 July 2025]. Available from: https://doi.org/10.32747/2023.8134362.ers. |

| 8. | United States Census Bureau. Beyond the Farm: Rural Industry Workers in America. [cited 5 June 2025]. Available from: https://www.census.gov/newsroom/blogs/random-samplings/2016/12/beyond_the_farm_rur.html. |

| 9. | U. S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics. [cited 5 June 2025]. Available from: https://www.bls.gov/oes/2023/may/oes452093.htm. |

| 10. | Pop T, Czenczek-Lewandowska E, Lewandowski B, Leszczak J, Podgórska-Bednarz J, Baran J. Occupational Activity in Patients 10 Years after Hip Replacement Surgery. Ortop Traumatol Rehabil. 2016;18:327-336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Carlson DA. Posterior bicondylar tibial plateau fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2005;19:73-78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Korovessis P, Katsoudas G, Salonikides P, Stamatakis M, Baikousis A. Medium- and long-term results of high tibial osteotomy for varus gonarthrosis in an agricultural population. Orthopedics. 1999;22:729-736. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Gowd AK, Garcia GH, Liu JN, Malaret MR, Cabarcas BC, Romeo AA. Comparative analysis of work-related outcomes in hemiarthroplasty with concentric glenoid reaming and total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2019;28:244-251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Shimada Y, Matsuki K, Sugaya H, Takahashi N, Tokai M, Hashimoto E, Ochiai N, Ohtori S. Return to sports and physical work after anatomical and reverse shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2023;32:1445-1451. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Mihata T, Lee TQ, Fukunishi K, Itami Y, Fujisawa Y, Kawakami T, Ohue M, Neo M. Return to Sports and Physical Work After Arthroscopic Superior Capsule Reconstruction Among Patients With Irreparable Rotator Cuff Tears. Am J Sports Med. 2018;46:1077-1083. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 158] [Article Influence: 19.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Mihata T, Lee TQ, Hasegawa A, Fukunishi K, Kawakami T, Fujisawa Y, Ohue M, Neo M. Five-Year Follow-up of Arthroscopic Superior Capsule Reconstruction for Irreparable Rotator Cuff Tears. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2019;101:1921-1930. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 23.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Mihata T, Lee TQ, Hasegawa A, Fukunishi K, Fujisawa Y, Ohue M. Long-term Clinical and Structural Outcomes of Arthroscopic Superior Capsule Reconstruction for Irreparable Rotator Cuff Tears: 10-Year Follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2025;53:46-56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Ohta S, Ueda Y, Komai O. Postoperative results of arthroscopic superior capsule reconstruction using fascia lata: a retrospective cohort study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2024;33:686-697. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Green CK, Scanaliato JP, Dunn JC, Rosner RS, Parnes N. Rates of Return to Manual Labor After Arthroscopic Rotator Cuff Repair. Am J Sports Med. 2022;50:2227-2233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Tilbury C, Schaasberg W, Plevier JW, Fiocco M, Nelissen RG, Vliet Vlieland TP. Return to work after total hip and knee arthroplasty: a systematic review. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2014;53:512-525. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Dal Fabbro G, Balboni G, Paolo SD, Varchetta G, Grassi A, Marcheggiani Muccioli GM, Zaffagnini S. Lateral closing wedge high tibial osteotomy procedure for the treatment of medial knee osteoarthritis: eleven years mean follow up analysis. Int Orthop. 2025;49:1655-1666. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kuijer PP, de Beer MJ, Houdijk JH, Frings-Dresen MH. Beneficial and limiting factors affecting return to work after total knee and hip arthroplasty: a systematic review. J Occup Rehabil. 2009;19:375-381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Denard PJ, Brady PC, Adams CR, Tokish JM, Burkhart SS. Preliminary Results of Arthroscopic Superior Capsule Reconstruction with Dermal Allograft. Arthroscopy. 2018;34:93-99. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 298] [Cited by in RCA: 353] [Article Influence: 44.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Zastrow RK, London DA, Parsons BO, Cagle PJ. Superior Capsule Reconstruction for Irreparable Rotator Cuff Tears: A Systematic Review. Arthroscopy. 2019;35:2525-2534.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Elhassan BT, Wagner ER, Werthel JD. Outcome of lower trapezius transfer to reconstruct massive irreparable posterior-superior rotator cuff tear. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2016;25:1346-1353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in RCA: 202] [Article Influence: 20.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Verma N, Srikumaran U, Roden CM, Rogusky EJ, Lapner P, Neill H, Abboud JA; on behalf of the SPACE GROUP. InSpace Implant Compared with Partial Repair for the Treatment of Full-Thickness Massive Rotator Cuff Tears: A Multicenter, Single-Blinded, Randomized Controlled Trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2022;104:1250-1262. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 17.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Probst J, Eberth JM, Crouch E. Structural Urbanism Contributes To Poorer Health Outcomes For Rural America. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019;38:1976-1984. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 22.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Zahnd WE, Scaife SL, Francis ML. Health literacy skills in rural and urban populations. Am J Health Behav. 2009;33:550-557. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, Moher D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372: n71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44932] [Cited by in RCA: 51349] [Article Influence: 10269.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/