Published online Feb 24, 2026. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v17.i2.114622

Revised: October 11, 2025

Accepted: December 18, 2025

Published online: February 24, 2026

Processing time: 135 Days and 11.4 Hours

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a leading cause of cancer-related mortality, particularly in Egypt, where hepatitis C virus (HCV) prevalence is high. T cell exhaustion markers such as programmed death 1 (PD-1), T cell immunoglobulin and ITIM domain, and T cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain-containing protein 3 (TIM-3) play a crucial role in HCC immune evasion; however, their expression patterns in Egyptian patients remain underexplored.

To characterize the expression of PD-1, T cell immunoglobulin and ITIM domain, and TIM-3 on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells across HCV-related liver disease stages and to determine their association with disease severity and survival in an Egyptian cohort.

This prospective case-control study included 200 Egyptian participants: 50 with HCV-related HCC, 50 with HCV-related cirrhosis, 50 with chronic HCV infection, and 50 healthy controls (HCV-negative by polymerase chain reaction). Flow cytometry quantified immune exhaustion markers, and clinical data were analyzed using multivariate and survival modeling frameworks, adjusting for key confounders.

HCC patients showed significantly higher expression of all T-cell exhaustion markers than other groups (P < 0.001). Alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) levels were markedly elevated in HCC (median 13210 ng/mL, P < 0.001). Marker expression showed strong positive correlations with Child-Pugh class, AFP, and Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer stage, and a negative correlation with model for end-stage liver disease score (all P < 0.001). Non-survivors (34%) had higher marker expression and AFP levels than survivors (P < 0.001). Receiver operating characteristic analysis demonstrated excellent mortality prediction for CD4/PD-1 [area under the curve (AUC) = 0.92] and AFP (AUC = 0.89), while combining AFP with CD8/TIM-3 achieved the best accuracy (AUC = 0.95). Cox regression identified high CD8/TIM-3 expression and Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer stage D as independent mortality predictors, and CD4/PD-1 partially mediated AFP’s effect on mortality (β = 0.45, P < 0.001).

Elevated T cell exhaustion markers were linked to advanced disease and poor survival in Egyptian patients with HCV-related HCC. Machine learning and mediation analyses identified CD4/PD-1 and CD8/TIM-3 as inde

Core Tip: Hepatocellular carcinoma linked to hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a major health burden in Egypt. This study comprehensively evaluated T cell exhaustion markers, programmed death 1, T cell immunoglobulin and ITIM domain, and T cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain-containing protein 3, on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells across HCV-related liver disease stages. Using advanced analyses, including Random Forest modeling, Cox regression, and mediation analysis, we identified CD4 programmed death 1 and CD8/T cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain-containing protein 3 as robust prognostic biomarkers of poor survival. These findings highlight novel immune targets for risk stratification and potential immunotherapy in HCV-related hepatocellular carcinoma.

- Citation: Hasan AM, Ghanem SMFI, Othman AAA, Rashad MH, Nosair N, Elgamal R. T cell exhaustion markers in hepatitis C virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma: Expression patterns and prognostic significance in an Egyptian cohort. World J Clin Oncol 2026; 17(2): 114622

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-4333/full/v17/i2/114622.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5306/wjco.v17.i2.114622

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the sixth most diagnosed cancer globally and the fourth leading cause of cancer-related mortality[1]. Chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is a major risk factor, contributing to cirrhosis in approximately 20% of cases and HCC in 4%-5% of cirrhotic patients annually[2,3]. Egypt has one of the highest HCV prevalence rates worldwide, with an estimated 10% of the population affected, making HCV-related HCC a significant public health burden[4]. Despite Egypt’s success in diagnosing 87% of HCV cases and treating 93% of those diagnosed, HCC incidence remains high due to long-term sequelae of chronic liver disease[5].

T cell exhaustion markers, including programmed death 1 (PD-1), T-cell immunoglobulin and ITIM domain (TIGIT), and T cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain-containing protein 3 (TIM-3), are critical in modulating immune res

The knowledge gap lies in understanding how these T cell exhaustion markers are expressed in Egyptian patients across the spectrum of HCV-related liver disease and their association with clinical outcomes like Child-Pugh class, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score, Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) stage, and mortality. This study aimed to characterize the expression of T cell exhaustion markers (PD-1, TIGIT, and TIM-3) on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in Egyptian patients with HCV-related HCC, cirrhosis, and HCV infection compared to healthy controls, hypothesizing that higher expression correlates with disease severity (advanced BCLC stage and Child-Pugh class) and worse prognosis. The clinical significance includes identifying potential biomarkers for HCC progression and targets for immunotherapy in a high-risk population. To our knowledge, this is the first comprehensive Egyptian study integrating machine learning and mediation analysis to evaluate T cell exhaustion markers in HCV-related HCC. This approach provides both mechanistic insights and clinical prognostic tools, strengthening the novelty and relevance of our findings.

This was a prospective case-control study conducted to evaluate and characterize the expression of T-cell exhaustion markers (PD-1, TIGIT, and TIM-3) on CD4+ T cell and CD8+ T cell in Egyptian patients with HCV-related liver disease. The study was carried out at the Department of Clinical Pathology, Kafr Elsheikh University Hospitals, with additional recruitment from the Departments of Internal Medicine and Departments of Clinical Pathology of Suez University Hospital, between January 2023 and December 2024.

A total of 200 participants were enrolled: 50 with HCV-related HCC, 50 with HCV-related cirrhosis, 50 with chronic HCV infection, and 50 healthy controls. Sample size adequacy was confirmed using G*Power software version 3.1 (Heinrich Heine University, Düsseldorf, Germany), providing 80% power (α = 0.05) to detect significant differences in immune checkpoint expression, based on prior studies[12]. The study design and reporting followed the STrengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology guidelines for case-control studies to ensure methodological transparency and reproducibility[13].

This study received approval from the Scientific Research Ethics Committee of Kafrelsheikh University (Approval No. KFSIRB200-712). All participants provided written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Anonymizing data maintained patient confidentiality.

The study included Egyptian adults (> 18 years) with HCV-related HCC secondary to liver cirrhosis, confirmed by radiological and pathological criteria; HCV-related cirrhosis without HCC, confirmed clinically and radiologically; chronic HCV infection without cirrhosis or HCC; and healthy controls with no history of liver disease or viral infections, verified by negative HCV PCR. Only adult participants were included to ensure immune system maturity and reduce age-related variability. Patients with other liver disease etiologies (e.g., HBV, autoimmune, alcoholic), concurrent malignancies, or chronic infections (e.g., HIV, tuberculosis) were excluded to minimize potential confounding of immune checkpoint expression.

Exclusion criteria encompassed liver cirrhosis due to causes other than HCV (e.g., hepatitis B virus, alcohol, or au

The primary outcome was the expression levels of immune checkpoint molecules (PD-1, TIGIT, and TIM-3) on CD4+ T cell and CD8+ T cell, measured as mean fluorescence intensity or percentage of positive cells via flow cytometry, across Egyptian patients with HCV-related HCC, HCV-related cirrhosis, HCV infection, and healthy controls. Secondary outcomes included T-cell subset levels (CD3, CD4, CD8, and CD4/CD8 ratio), serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) levels, Child-Pugh class, MELD score, BCLC stage, lesion size, and mortality in HCC patients.

Clinical evaluation: All participants underwent comprehensive clinical assessments, including detailed history taking and physical examination to document demographics (age, sex), medical history, and liver disease status (e.g., symptoms, duration of HCV infection, or HCC-related complications). This ensured accurate characterization of disease stage and participant eligibility for the study groups.

Radiological assessment: Radiological evaluations included triphasic computed tomography (arterial, portal venous, and delayed phases, performed on a 64-slice scanner) and abdominal ultrasound (using a 3.5-5 MHz probe) to confirm HCC diagnosis, assess lesion size (< 3 cm or > 3 cm), and stage HCC using the BCLC system. Imaging was performed at baseline by experienced radiologists at Kafr Elsheikh University Hospital and Suez University Hospital, with stan

Laboratory investigations: Laboratory tests comprised liver function tests [aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), albumin, total bilirubin, measured via automated analyzer, Roche Cobas 6000, with reference ranges: AST 10-40 U/L, ALT 7-56 U/L, albumin 35-50 g/L, bilirubin 0.1-1.0 mg/dL] and AFP levels measured via enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (sensitivity 0.5 ng/mL, performed in duplicate; Roche Diagnostics, Switzerland). Complete blood count, C-reactive protein, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate were assessed in HCC and cirrhosis groups to evaluate systemic inflammation, using Sysmex XN-1000 (complete blood count) and standard turbidimetric/eryth

Virological testing included quantitative HCV polymerase chain reaction (PCR; Roche COBAS AmpliPrep/TaqMan, detection limit 15 IU/mL; Roche Diagnostics, Switzerland) to confirm active HCV infection in the HCC, cirrhosis, and HCV groups. Healthy controls underwent liver function tests and HCV PCR to confirm the absence of liver disease and infection. These tests provided biochemical and virological profiles to assess liver function and HCC severity. All assays included internal quality controls and were performed in accredited laboratories. HCV RNA was extracted from serum samples using the QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, The Kingdom of the Netherlands), following the manufacturer’s instructions, and reverse transcribed into complementary DNA using a universal reverse primer. The Abbott RealTime HCV assay, targeting the 5’ untranslated region (5’ UTR) with primers (forward: 5’-GCAGAAAGCGTCTAGCCATGG CG-3’, reverse: 5’-CTCCCGGGGCACTCGCAAGC-3’) and probe (5’-FAM-AGCCATAGTGGTCTGCGGAACCGGT-TAMRA-3’), was used for quantification, with a detection limit of 15 IU/mL. To confirm HCV genotype 4, reverse tran

Immunophenotyping: Peripheral blood samples (5 mL) were collected in ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid tubes by venipuncture and processed within 4 hours to preserve cell viability. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were isolated by Ficoll-Hypaque density gradient centrifugation (Biochrom GmbH, Germany) and immediately analyzed. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (Life Technologies, CA, United States) and incubated with FcR blocking reagent (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). Approximately 2 × 106 cells were then suspended in staining buffer containing 0.2% (weight/volume) bovine serum albumin (BD Pharmingen, CA, United States).

Cells were stained with fluorochrome-conjugated monoclonal antibodies in three tubes: Tube I contained CD3 (UCHT1, FITC), CD4 (RPA-T4, APC), CD8 (RPA-T8, PE-Cy7), and PD-1 (EH12.2H7, BV421); Tube II contained CD3 (UCHT1, FITC), CD4 (RPA-T4, APC), CD8 (RPA-T8, PE-Cy7), and TIM-3 (F38-2E2, BV421); and Tube III contained CD3 (UCHT1, FITC), CD4 (RPA-T4, APC), CD8 (RPA-T8, PE-Cy7), and TIGIT (741182, BV421). All monoclonal antibodies were purchased from BD Biosciences (CA, United States), except PD-1 and TIM-3, which were obtained from BioLegend (Germany). Staining was performed at 4 °C for 20 minutes in the dark, followed by washing with phosphate-buffered saline. Unstained controls, isotype-matched controls, and fluorescence-minus-one controls were included for each sample to ensure accurate gating and compensation.

Flow cytometry was performed using a BD FACSCanto II system, and data were analyzed with FlowJo version 9 software (BD Biosciences, CA, United States). Lymphocytes were defined by forward scatter and side scatter properties and confirmed with CD45/side scatter. Sequential gating on CD3+ T cells was applied to assess PD-1, TIM-3, and TIGIT expression on CD4+ and CD8+ subsets. Results were expressed as the percentage of positive cells in each population (CD4/PD-1, CD8/PD-1, CD4/TIM-3, CD8/TIM-3, CD4/TIGIT, CD8/TIGIT).

Clinical outcome assessment: Liver function severity was evaluated using the Child-Pugh classification [based on albumin, bilirubin, international normalized ratio (INR), ascites, and encephalopathy, scored A-C] and the MELD score (calculated using serum creatinine, bilirubin, and INR, range 6-40) for HCC and cirrhosis patients. MELD scores were unexpectedly low (mean 2.5-2.56), likely reflecting early HCC detection through Egypt’s national screening programs rather than advanced hepatic decompensation. This explains the apparent discrepancy with typically higher MELD scores reported in non-screened populations. Clinical outcomes, including mortality (survivors vs non-survivors), were recorded at the study’s end (12-month follow-up, confirmed via hospital records and death certificates) to assess HCC prognosis and its association with immune checkpoint expression.

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 28 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States) and R version 4.3.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). G*Power version 3.1 was used for the a priori sample size calculation (described in the study design section). Continuous variables were tested for normality using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Normally distributed variables (e.g., CD4/PD-1, CD8/PD-1, CD4/TIGIT, CD8/TIGIT, CD4/TIM-3, CD8/TIM-3, CD3, CD4, CD8, CD4/CD8 ratio, MELD score) were expressed as means ± SD and compared using independent t-tests (two groups) or one-way ANOVA (multiple groups). When relevant, ANCOVA was applied to adjust for age and Child-Pugh class, with Tukey’s post hoc test for pairwise comparisons. Non-normally distributed variables (e.g., AFP) were reported as medians [interquartile ranges (IQRs)] and compared using the Mann-Whitney U or Kruskal-Wallis test, followed by Dunn-Bonferroni pairwise comparisons. Categorical variables (e.g., Child-Pugh class, BCLC stage, lesion size, mortality) were expressed as frequencies (%) and analyzed using χ2 or χ2 for trend tests.

Correlations were examined using Pearson’s coefficient for normally distributed data and Spearman’s rank correlation for non-parametric data. Multivariable logistic regression identified independent predictors of mortality among HCC patients, adjusting for age, sex, Child-Pugh class, and BCLC stage, with results expressed as odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Cox proportional hazards regression assessed overall survival, with univariate and mul

Mediation analysis (mediation package) evaluated the indirect effect of CD4/PD-1 on the AFP-mortality relationship, adjusting for BCLC stage, and reported direct, indirect, and total effects with 95%CIs. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis assessed prognostic accuracy for mortality prediction (e.g., CD4/PD-1, CD8/TIM-3, AFP, and AFP+CD8/TIM-3 combination) and for diagnostic discrimination between HCC and cirrhosis, adjusted for Child-Pugh class. Area under the curve (AUC) values, sensitivity, specificity, and optimal cut-offs were determined by Youden’s index. Effect sizes were calculated as Cohen’s d for t-tests and η2 for ANOVA, each with 95%CIs to quantify magnitude and precision.

Multiple comparison control was applied using the Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR), with FDR-adjusted P < 0.05 considered significant. Missing data were minimal (< 2%) and confined to a few secondary biochemical pa

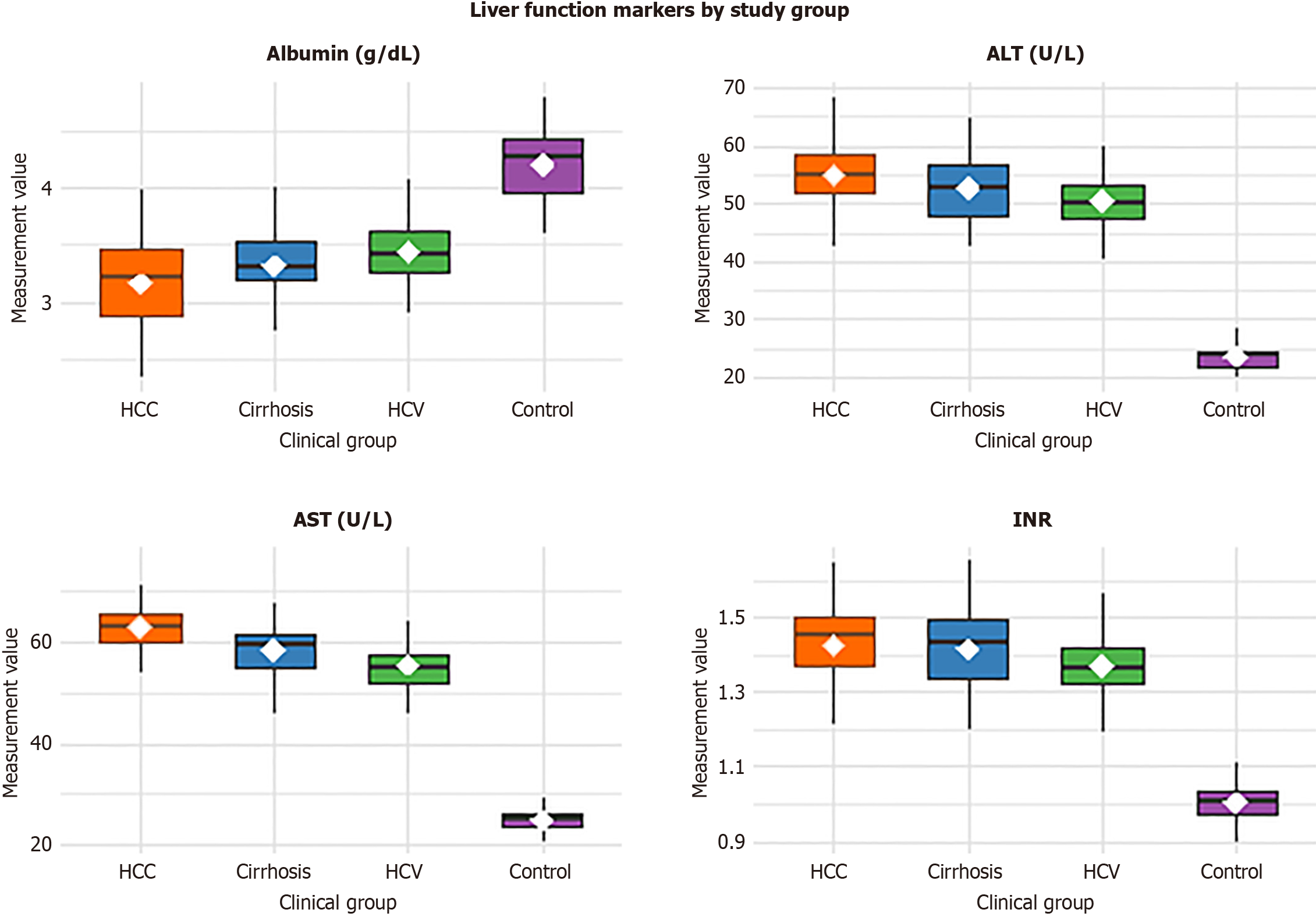

The study included 200 Egyptian participants, equally divided into four groups: 50 with HCV-related HCC, 50 with HCV-related cirrhosis, 50 with chronic HCV infection, and 50 healthy controls. Age and sex distribution were comparable across groups (P = 0.312 and P = 0.894, respectively). In contrast, liver function parameters showed significant group differences (P < 0.001). ALT and AST levels were higher, and albumin levels lower, in HCC, cirrhosis, and chronic HCV groups compared with controls, consistent with progressive hepatic impairment. The INR was also elevated in HCC and cirrhosis, reflecting reduced synthetic function. Detailed demographic and biochemical parameters are presented in Figure 1, Table 1.

| Parameter | HCC (n = 50) | Cirrhosis (n = 50) | HCV (n = 50) | Controls (n = 50) | Test | P value |

| Age (years) | 57.4 ± 8.2 | 55.9 ± 7.8 | 54.8 ± 8.0 | 54.2 ± 7.6 | ANOVA | 0.312 |

| Sex (male/female) | 34/16 | 32/18 | 31/19 | 30/20 | χ2 | 0.894 |

| ALT (U/L) | 55.0 (48.0-63.0) | 52.0 (46.0-61.0) | 50.0 (44.0-58.0) | 24.0 (20.0-28.0) | Kruskal-Wallis | < 0.001a |

| AST (U/L) | 62.0 (54.0-70.0) | 58.0 (50.0-66.0) | 56.0 (49.0-62.0) | 25.0 (21.0-29.0) | Kruskal-Wallis | < 0.001a |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.2 ± 0.4 | 3.3 ± 0.4 | 3.5 ± 0.3 | 4.2 ± 0.3 | ANOVA | < 0.001a |

| INR | 1.42 ± 0.12 | 1.40 ± 0.11 | 1.35 ± 0.10 | 1.01 ± 0.05 | ANOVA | < 0.001a |

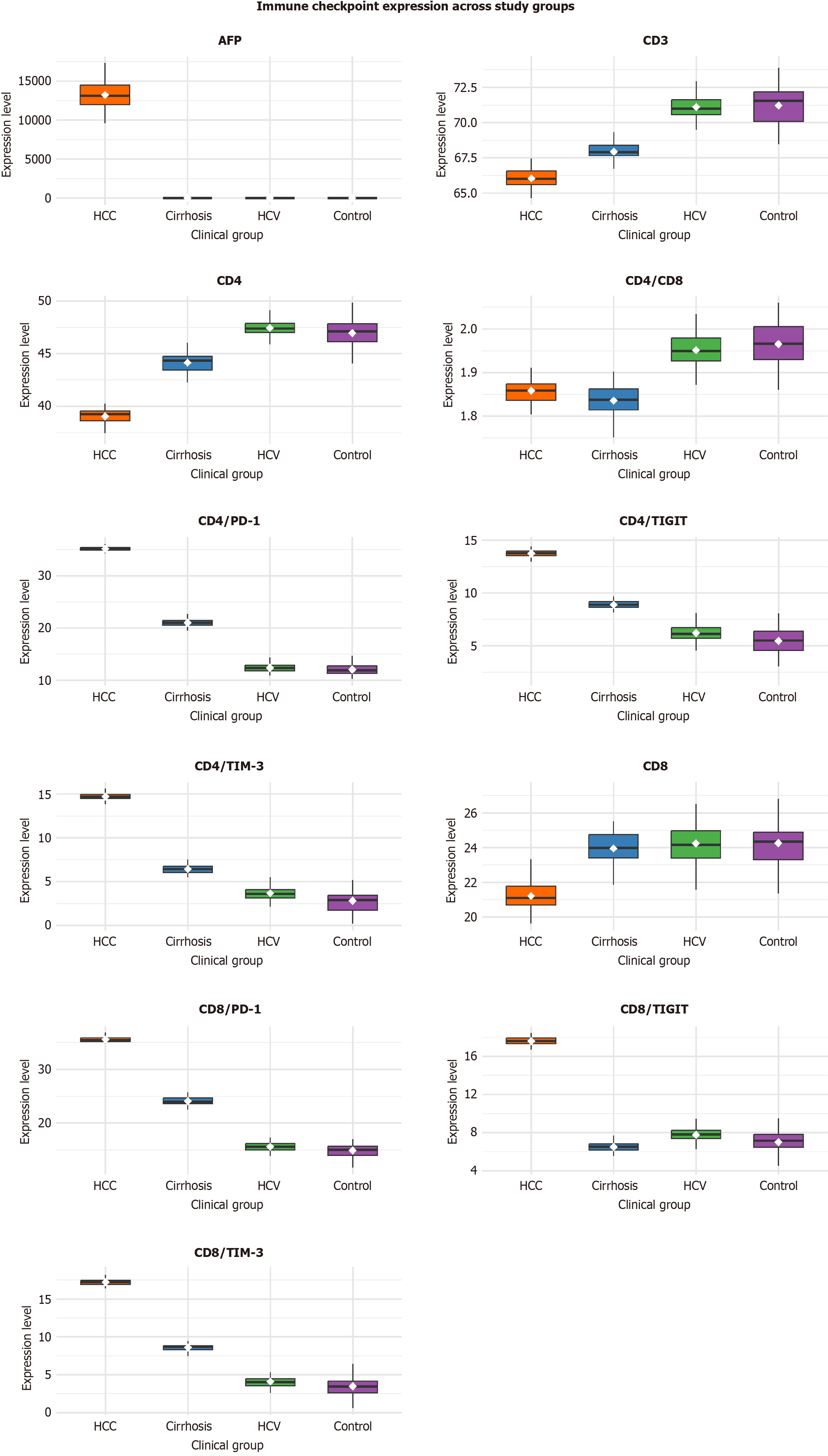

Immune checkpoint expression and T-cell subset profiles differed markedly among the four study groups (Table 2). HCC patients exhibited significantly higher expression of all T-cell exhaustion markers (PD-1, TIGIT, and TIM-3) on both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells compared to cirrhosis, chronic HCV, and control groups (all P < 0.001). CD4/PD-1 and CD8/PD-1 expression reached 35.14 ± 0.43 and 35.57 ± 0.58 in HCC vs 20.87 ± 0.90 and 23.89 ± 0.81 in cirrhosis, 12.59 ± 0.84 and 15.60 ± 0.84 in HCV, and 12.00 ± 1.33 and 15.00 ± 1.33 in controls, respectively. Similar significant trends were seen for TIGIT (CD4: 13.77 ± 0.37; CD8: 17.66 ± 0.38) and TIM-3 (CD4: 14.70 ± 0.34; CD8: 17.14 ± 0.44), with the largest mean differences between HCC and controls (Cohen’s d > 5.0), confirming robust separation of malignant vs non-malignant immune profiles.

| Parameter | HCC (n = 50) | Cirrhosis (n = 50) | HCV (n = 50) | Control (n = 50) | 8F/Kruskal-Wallis | P value |

| CD4/PD1 | 35.14 ± 0.43 | 20.87 ± 0.9 | 12.59 ± 0.84 | 12.0 ± 1.33 | 6700.7 | < 0.001c |

| Post hoc7 | 1P < 0.001c, 2P < 0.001c, 3P = 0.001b, 4P < 0.001c, 5P < 0.001c, 6P < 0.001c | |||||

| CD8/PD1 | 35.57 ± 0.58 | 23.89 ± 0.81 | 15.6 ± 0.84 | 15.0 ± 1.33 | 5854.15 | < 0.001c |

| Post hoc7 | 1P < 0.001c, 2P < 0.001c, 3P = 0.007b, 4P < 0.001c, 5P < 0.001c, 6P < 0.001c | |||||

| CD4/TIGIT | 13.77 ± 0.37 | 8.76 ± 0.46 | 6.18 ± 0.79 | 5.6 ± 1.33 | 1011.91 | < 0.001c |

| Post hoc7 | 1P < 0.001c, 2P > 0.999, 3P = 0.003b, 4P < 0.001c, 5P < 0.001c, 6P < 0.001c | |||||

| CD8/TIGIT | 17.66 ± 0.38 | 6.56 ± 0.46 | 7.6 ± 0.77 | 7.0 ± 1.32 | 2088.86 | < 0.001c |

| Post hoc7 | 1P < 0.001c, 2P < 0.001c, 3P =0.002b, 4P < 0.001c, 5P < 0.001c, 6P =0.043a | |||||

| CD4/TIM3 | 14.7 ± 0.34 | 6.34 ± 0.46 | 3.6 ± 0.77 | 3.0 ± 1.33 | 2169.06 | < 0.001c |

| Post hoc7 | 1P < 0.001c, 2P > 0.999, 3P = 0.002b, 4P < 0.001c, 5P < 0.001c, 6P < 0.001c | |||||

| CD8/TIM3 | 17.14 ± 0.44 | 8.56 ± 0.46 | 4.1 ± 0.77 | 3.5 ± 1.33 | 2868.84 | < 0.001c |

| Post hoc7 | 1P < 0.001c, 2P < 00.001c, 3P = 0.002b, 4P < 0.001c, 5P < 0.001c, 6P < 0.001c | |||||

| CD3 | 66.12 ± 0.68 | 67.84 ± 0.83 | 71.25 ± 0.88 | 71.15 ± 1.37 | 339.21 | < 0.001c |

| Post hoc7 | 1P < 0.001c, 2P < 0.001c, 3P = 0.945, 4P < 0.001c, 5P < 0.001c, 6P < 0.001c | |||||

| CD4 | 39.06 ± 0.75 | 43.95 ± 0.91 | 47.25 ± 0.88 | 47.15 ± 1.37 | 733.67 | < 0.001c |

| Post hoc7 | 1P < 0.001c, 2P < 0.001c, 3P = 0.95, | |||||

| CD8 | 21.06 ± 0.69 | 23.98 ± 0.87 | 24.25 ± 0.88 | 24.15 ± 1.37 | 122.07 | < 0.001c |

| Post hoc7 | 1P < 0.001c, 2P = 0.05, 3P = 0.947, | |||||

| CD4/CD8 | 1.86 ± 0.03 | 1.83 ± 0.03 | 1.95 ± 0.03 | 1.96 ± 0.05 | 140.79 | < 0.001c |

| Post hoc7 | 1P = 0.023a, 2P < 0.001c, 3P = 0.852, 4P < 0.001c, 5P < 0.001c, 6P < 0.001c | |||||

| AFP (ng/mL) | 13210 (11008.3-14956.8) | 4 (2-6) | 6.85 (6.08-7.5) | 4.3 (3.08-5.53) | 144.208 | < 0.001c |

| Post hoc7 | 1P < 0.001c, 2P < 0.001c, 3P < 0.001c, 4P < 0.001c, 5P < 0.001c, 6P = 0.883 |

Regarding T-cell subsets, total CD3+ T-cell and CD4+ T-cell percentages were reduced in HCC and cirrhosis compared with HCV and controls (P < 0.001), while CD8+ T-cell levels were lowest in HCC (21.06 ± 0.69) and highest in controls (24.15 ± 1.37). The CD4/CD8 ratio was slightly decreased in HCC (1.86 ± 0.03) vs controls (1.96 ± 0.05; P < 0.001). As expected, AFP levels were profoundly elevated in HCC (median 13210 ng/mL, IQR 11008.3-14956.8 ng/mL; P < 0.001), confirming the link between immune exhaustion and tumor burden.

In summary, these results demonstrate progressive upregulation of PD-1, TIGIT, and TIM-3 expression across the spectrum of HCV-related liver disease, peaking in HCC, with concurrent reductions in functional T-cell subsets and markedly elevated AFP levels (Figure 2).

Liver function severity, assessed by Child-Pugh class and MELD score, showed no significant differences between HCC and cirrhosis groups (Table 3). The mean MELD score was 2.5 ± 1.0 in HCC and 2.56 ± 1.09 in cirrhosis (P = 0.774, t-test). Child-Pugh class distribution was also comparable, with 64% of HCC patients and 50% of cirrhosis patients classified as Child-Pugh C (P = 0.18, χ2 for trend). This lack of difference suggests that immune checkpoint upregulation in HCC is driven by tumor-specific factors rather than overall liver dysfunction severity, as MELD and Child-Pugh scores reflect similar degrees of hepatic impairment in both groups.

| Parameter | HCC (n = 50) | Cirrhosis (n = 50) | t/χ2 | P value |

| MELD | 2.5 ± 1.0 | 2.56 ± 1.09 | -0.287 | 0.774 |

| Child-Pugh class | 1.795 | 0.18 | ||

| A | 9 (18) | 13 (26) | ||

| B | 9 (18) | 12 (24) | ||

| C | 32 (64) | 25 (50) |

Among HCC patients, tumor characteristics and clinical outcomes highlighted advanced disease (Table 4). Notably, 64% had lesion sizes > 3 cm, and 64% were classified as BCLC stage D, indicating late-stage HCC. Mortality was observed in 34% of HCC patients (17 non-survivors vs 33 survivors) by the study’s end. These findings underscore the aggressive nature of HCC in this Egyptian cohort, consistent with the high tumor burden reflected by elevated AFP levels and immune checkpoint expression.

| Parameter | n = 50 |

| Fate | |

| Non-survivor | 17 (34) |

| Survivor | 33 (66) |

| Lesion size | |

| < 3 cm | 18 (36) |

| > 3 cm | 32 (64) |

| BCLC stage | |

| A | 9 (18) |

| B | 1 (2) |

| C | 8 (16) |

| D | 32 (64) |

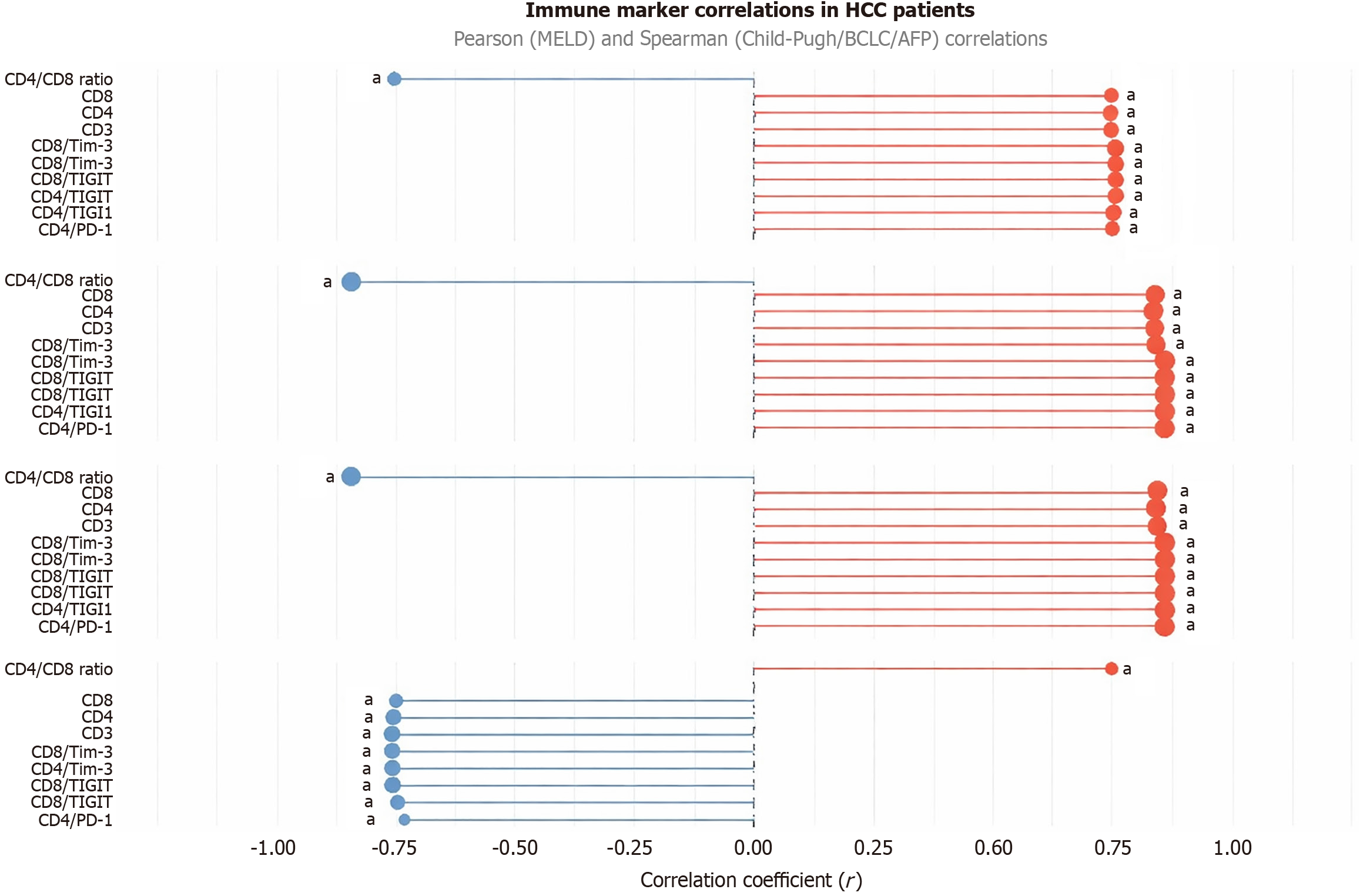

In HCC patients, immune checkpoint expression strongly correlated with clinical severity markers (Figure 3; Table 5). CD4/PD-1, CD8/PD-1, CD4/TIGIT, CD8/TIGIT, CD4/TIM3, CD8/TIM3, CD3, CD4, and CD8 showed positive correlations with Child-Pugh class (r = 0.83-0.86, P < 0.001), AFP (r = 0.75-0.81, P < 0.001), and BCLC stage (r = 0.83-0.86, P < 0.001), but negative correlations with MELD score (r = -0.73 to -0.76, P < 0.001). The CD4/CD8 ratio negatively correlated with Child-Pugh class (r = -0.844, P < 0.001), AFP (r = -0.749, P < 0.001), and BCLC stage (r = -0.84, P < 0.001), but positively with MELD score (r = 0.745, P < 0.001).

| Parameter | MELD | Child-Pugh | AFP | BCLC stage | ||||

| r1 | P value | r1 | P value | r1 | P value | r1 | P value | |

| CD4/PD-1 (%) | -0.730 | < 0.001a | 0.855 | < 0.001a | 0.750 | < 0.001a | 0.855 | < 0.001a |

| CD8/PD-1 (%) | -0.738 | < 0.001a | 0.855 | < 0.001a | 0.752 | < 0.001a | 0.855 | < 0.001a |

| CD4/TIGIT (%) | -0.764 | < 0.001a | 0.857 | < 0.001a | 0.758 | < 0.001a | 0.856 | < 0.001a |

| CD8/TIGIT (%) | -0.764 | < 0.001a | 0.856 | < 0.001a | 0.756 | < 0.001a | 0.856 | < 0.001a |

| CD4/TIM-3 (%) | -0.764 | < 0.001a | 0.858 | < 0.001a | 0.759 | < 0.001a | 0.858 | < 0.001a |

| CD8/TIM-3 (%) | -0.764 | < 0.001a | 0.835 | < 0.001a | 0.745 | < 0.001a | 0.835 | < 0.001a |

| CD3 (%) | -0.765 | < 0.001a | 0.837 | < 0.001a | 0.748 | < 0.001a | 0.837 | < 0.001a |

| CD4 (%) | -0.756 | < 0.001a | 0.830 | < 0.001a | 0.746 | < 0.001a | 0.830 | < 0.001a |

| CD8 (%) | -0.751 | < 0.001a | 0.835 | < 0.001a | 0.749 | < 0.001a | 0.835 | < 0.001a |

| CD4/CD8 ratio | 0.745 | < 0.001a | -0.844 | < 0.001a | -0.749 | < 0.001a | -0.840 | < 0.001a |

Multivariable logistic regression, adjusted for age, sex, and BCLC stage, revealed that higher CD4/PD-1 (OR = 2.1, 95%CI: 1.4-3.2, P < 0.001) and CD8/TIM3 (OR = 2.3, 95%CI: 1.5-3.5, P < 0.001) were independently associated with increased mortality risk. These correlations suggest that immune checkpoint upregulation is tightly linked to HCC progression and poor prognosis, potentially reflecting tumor-driven immune suppression.

All reported P-values were corrected for multiple testing using the Benjamini-Hochberg FDR method; only associations remaining significant at FDR-adjusted P < 0.05 are shown.

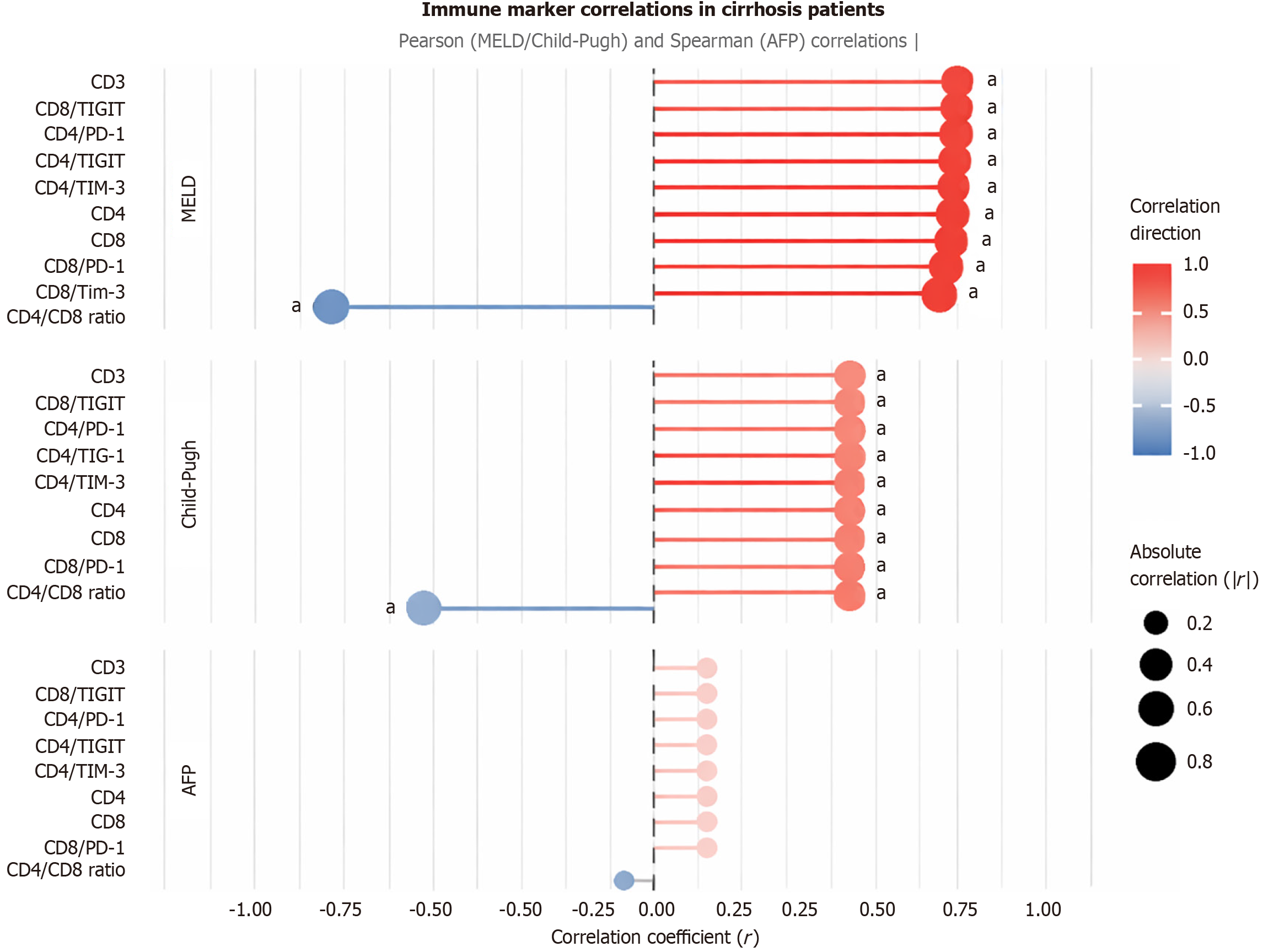

In the cirrhosis group, immune checkpoint markers and T-cell subsets showed distinct correlation patterns (Figure 4; Table 6). CD4/PD-1, CD8/PD-1, CD4/TIGIT, CD8/TIGIT, CD4/TIM3, CD8/TIM3, CD3, CD4, and CD8 positively correlated with MELD score (r = 0.88-0.93, P < 0.001) and Child-Pugh class (r = 0.56-0.57, P < 0.001), but showed no significant correlation with AFP (P > 0.05). The CD4/CD8 ratio negatively correlated with MELD (r = -0.901, P < 0.001) and Child-Pugh class (r = -0.562, P < 0.001). These findings suggest that immune checkpoint expression in cirrhosis is more closely tied to liver dysfunction severity than tumor-specific markers like AFP, contrasting with the HCC group.

| Parameter | MELD | Child-Pugh | AFP | |||

| r1 | P value | r1 | P value | r1 | P value | |

| CD4/PD-1 (%) | 0.926 | < 0.001a | 0.557 | < 0.001a | 0.142 | 0.324 |

| CD8/PD-1 (%) | 0.910 | < 0.001a | 0.566 | < 0.001a | 0.150 | 0.296 |

| CD4/TIGIT (%) | 0.919 | < 0.001a | 0.565 | < 0.001a | 0.138 | 0.339 |

| CD8/TIGIT (%) | 0.927 | < 0.001a | 0.565 | < 0.001a | 0.142 | 0.324 |

| CD4/TIM-3 (%) | 0.917 | < 0.001a | 0.565 | < 0.001a | 0.140 | 0.331 |

| CD8/TIM-3 (%) | 0.883 | < 0.001a | 0.565 | < 0.001a | 0.144 | 0.315 |

| CD3 (%) | 0.932 | < 0.001a | 0.563 | < 0.001a | 0.146 | 0.307 |

| CD4 (%) | 0.916 | < 0.001a | 0.562 | < 0.001a | 0.141 | 0.329 |

| CD8 (%) | 0.914 | < 0.001a | 0.562 | < 0.001a | 0.142 | 0.324 |

| CD4/CD8 ratio | -0.901 | < 0.001a | -0.562 | < 0.001a | -0.145 | 0.309 |

All reported P-values were corrected for multiple testing using the Benjamini-Hochberg FDR method; only associations remaining significant at FDR-adjusted P < 0.05 are shown.

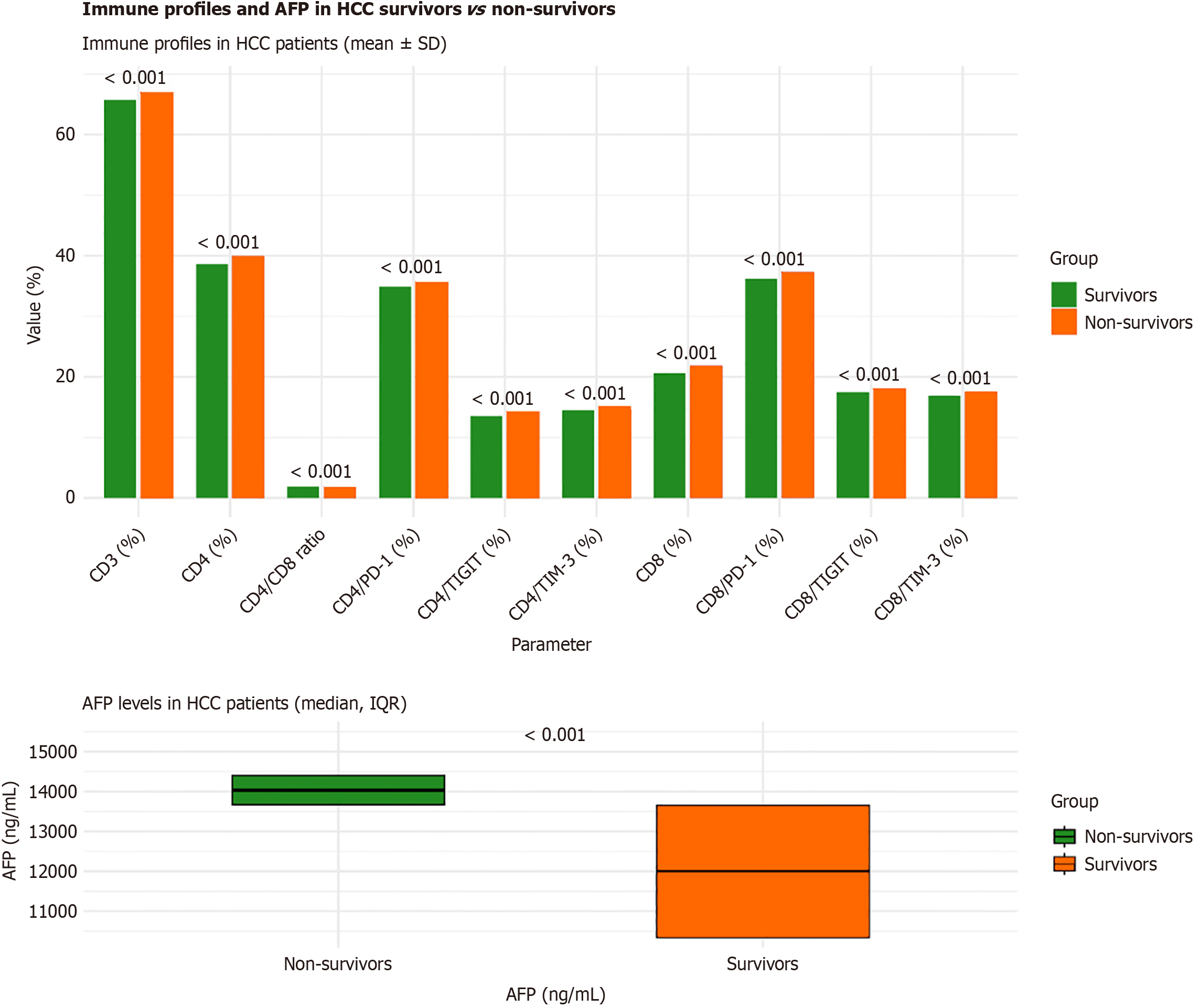

Immune checkpoint expression and T-cell subset levels differed significantly between HCC survivors (n = 33) and non-survivors (n = 17; Table 7). Non-survivors showed consistently higher expression of all exhaustion markers - PD-1, TIGIT, and TIM-3, on both CD4+ T cell and CD8+ T cell (all P < 0.001). The most pronounced increases were observed for CD4/PD-1 (35.63 ± 0.21 vs 34.86 ± 0.25) and CD8/PD-1 (37.28 ± 0.26 vs 36.20 ± 0.27), reflecting stronger immune exhaustion among fatal cases (Figure 5).

| Parameter | Survivors (n = 33) | Non-survivors (n = 17) | t/Z1 | P value |

| CD4/PD-1 (%) | 34.86 ± 0.25 | 35.63 ± 0.21 | -10.52 | < 0.001a |

| CD8/PD-1 (%) | 36.20 ± 0.27 | 37.28 ± 0.26 | -13.63 | < 0.001a |

| CD4/TIGIT (%) | 13.54 ± 0.21 | 14.21 ± 0.17 | -11.32 | < 0.001a |

| CD8/TIGIT (%) | 17.43 ± 0.21 | 18.11 ± 0.17 | -11.56 | < 0.001a |

| CD4/TIM-3 (%) | 14.50 ± 0.17 | 15.11 ± 0.17 | -12.12 | < 0.001a |

| CD8/TIM-3 (%) | 16.86 ± 0.17 | 17.67 ± 0.27 | -12.66 | < 0.001a |

| CD3 (%) | 65.72 ± 0.41 | 66.90 ± 0.32 | -10.46 | < 0.001a |

| CD4 (%) | 38.60 ± 0.43 | 39.94 ± 0.36 | -10.95 | < 0.001a |

| CD8 (%) | 20.64 ± 0.36 | 21.88 ± 0.35 | -11.65 | < 0.001a |

| CD4/CD8 ratio | 1.87 ± 0.01 | 1.83 ± 0.01 | 11.82 | < 0.001a |

| AFP (ng/mL) | 12004 (10341-13654.5) | 14030 (13672.5-14406) | -3.85 | < 0.001a |

Total CD3+, CD4+, and CD8+ T-cell proportions were modestly higher in non-survivors, while the CD4/CD8 ratio was slightly reduced (1.83 ± 0.01 vs 1.87 ± 0.01; P < 0.001). AFP levels were markedly elevated in non-survivors (median 14030 ng/mL; IQR 13672.5-14406 ng/mL) compared with survivors (12004 ng/mL; IQR 10341-13654.5 ng/mL; P < 0.001; Table 7).

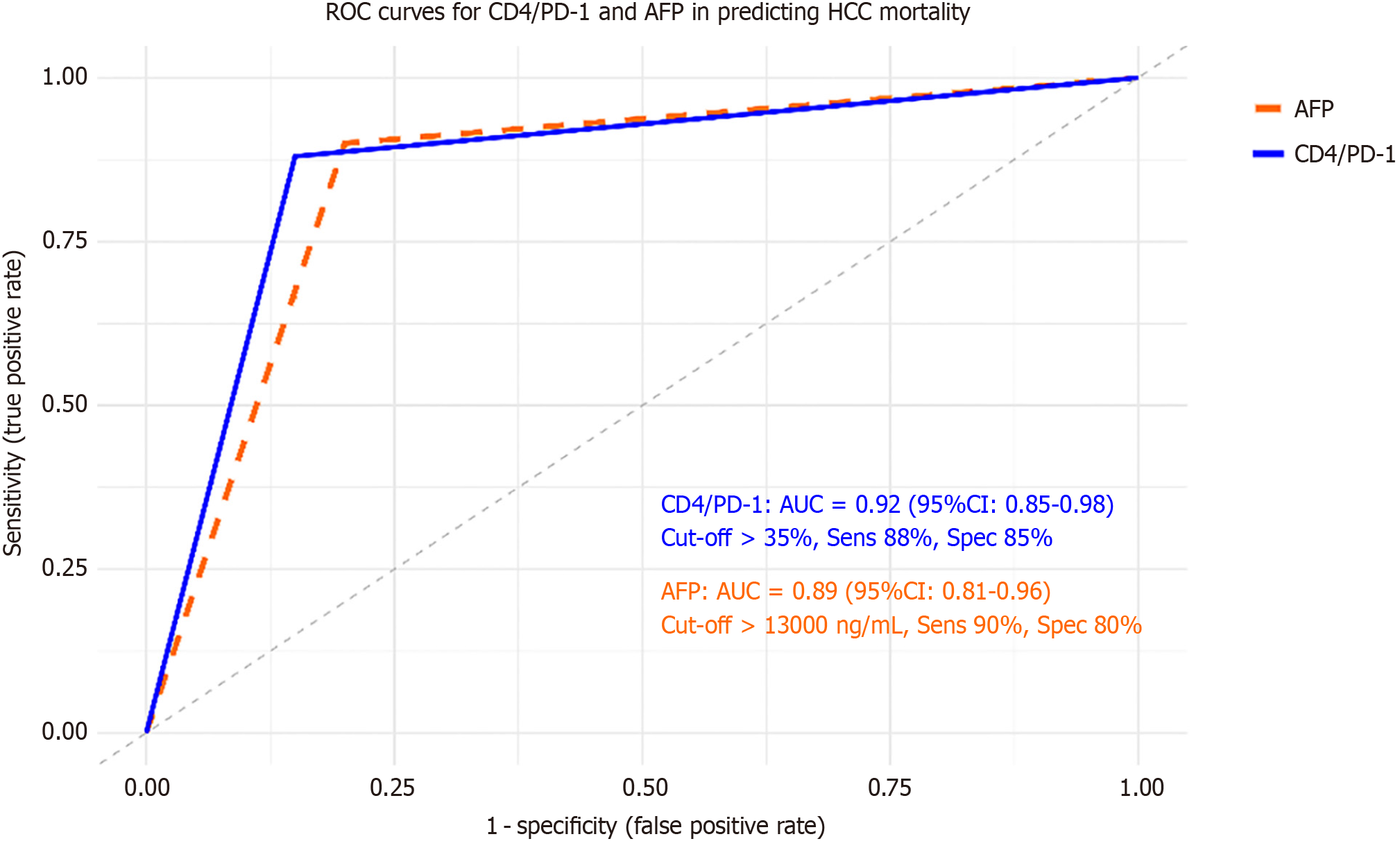

ROC analysis demonstrated strong discriminative accuracy for both CD4/PD-1 (AUC = 0.92; 95%CI: 0.85-0.98) and AFP (AUC = 0.89; 95%CI: 0.81-0.96) in predicting mortality, with sensitivities of 88%-90% and specificities of 80%-85% (Figure 6). All P -values remained significant after FDR correction.

These results indicate that elevated PD-1, TIGIT, and TIM-3 expression, particularly on CD4+ and CD8+ subsets, along with high AFP levels, identify HCC patients with the poorest survival outcomes.

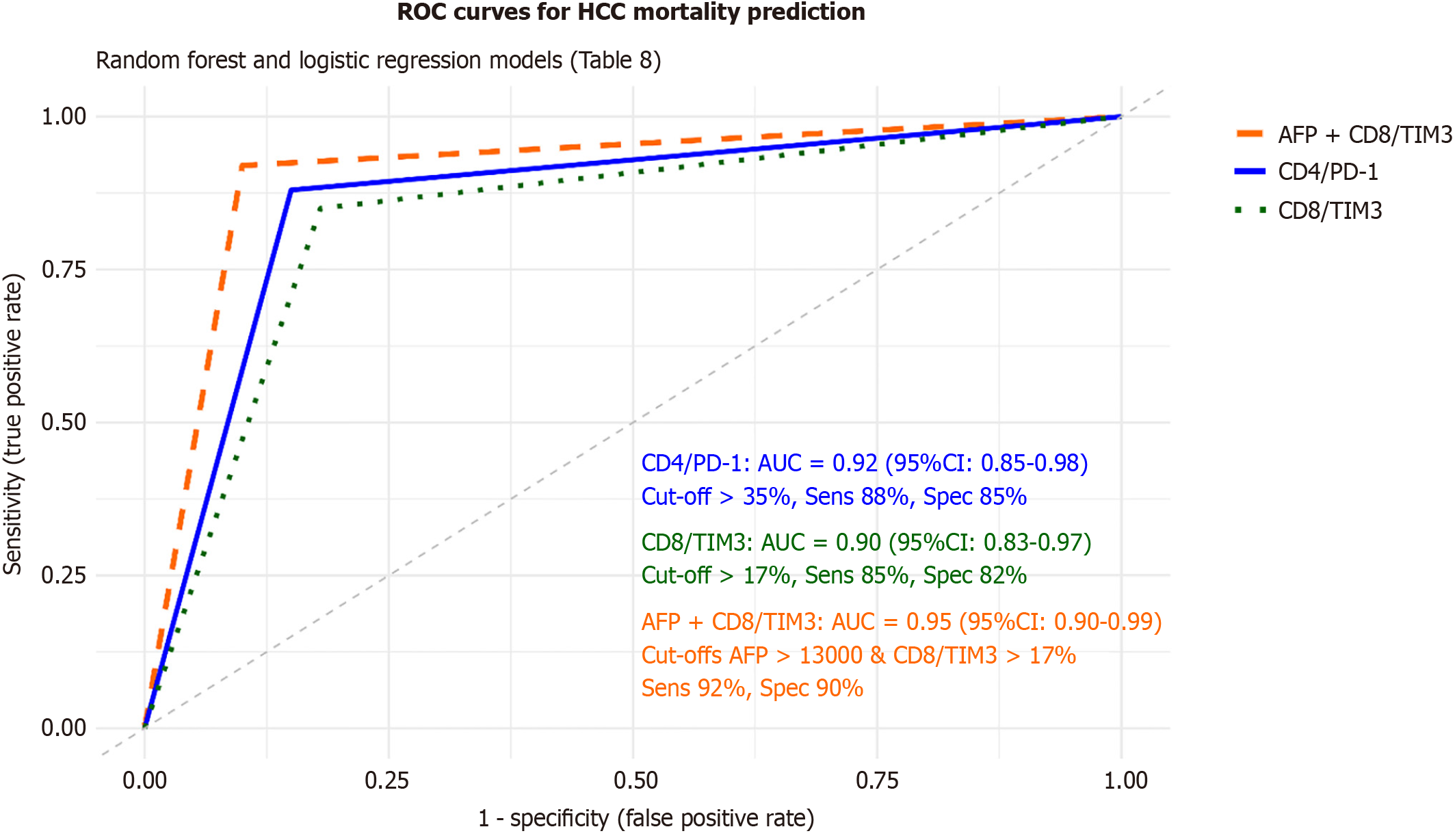

To refine mortality prediction, both machine learning and multivariable statistical modeling were applied (Figure 7; Table 8). A random forest model incorporating immune checkpoint markers, AFP, and BCLC stage identified CD4/PD-1, CD8/TIM-3, and AFP as the top-ranked predictors of mortality. K-means clustering based on PD-1, TIGIT, and TIM-3 expression classified HCC patients into two immune-exhaustion subgroups: A high-expression cluster (n = 30, 50% mortality) and a low-expression cluster (n = 20, 10% mortality; P < 0.001).

| Variable | Random forest AUC (95%CI) | Logistic regression OR (95%CI) | P value | ROC AUC (95%CI) | Cut-off | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) |

| CD4/PD-1 (%) | 0.92 (0.85-0.98) | 2.3 (1.4-3.8) | < 0.001a | 0.92 (0.85-0.98) | > 35% | 88 | 85 |

| CD8/TIM3 (%) | 0.90 (0.83-0.97) | 2.5 (1.5-4.2) | < 0.001a | 0.90 (0.83-0.97) | > 17% | 85 | 82 |

| AFP (ng/mL) | 3.2 (1.8-5.7) | < 0.001a | 0.89 (0.81-0.96) | > 13000 | 90 | 80 | |

| AFP + CD8/TIM3 | 0.95 (0.90-0.99) | < 0.001a | 0.95 (0.90-0.99) | > 13000, > 17% | 92 | 90 | |

| BCLC stage (D vs A-C) | 3.8 (2.0-7.2) | < 0.001a | |||||

| Clustering: High-expression | 50% mortality (n = 30) | < 0.001a | Elevated (PD-1, TIGIT, TIM-3) | ||||

| Clustering: Low-expression | 10% mortality (n = 20) | < 0.001a | Low (PD-1, TIGIT, TIM-3) |

Logistic regression confirmed CD4/PD-1 (OR = 2.3, 95%CI: 1.4-3.8, P < 0.001), CD8/TIM-3 (OR = 2.5, 95%CI: 1.5-4.2, P < 0.001), AFP (OR = 3.2, 95%CI: 1.8-5.7, P < 0.001), and BCLC stage D (OR = 3.8, 95%CI: 2.0-7.2, P < 0.001) as independent predictors of HCC mortality. In ROC analyses, CD4/PD-1 (AUC = 0.92; 95%CI: 0.85-0.98), CD8/TIM-3 (AUC = 0.90; 95%CI: 0.83-0.97), and AFP (AUC = 0.89; 95%CI: 0.81-0.96) each showed excellent discriminative accuracy. Combining AFP + CD8/TIM-3 further improved prognostic performance (AUC = 0.95; 95%CI: 0.90-0.99; sensitivity 92%; specificity 90%). All results remained significant after FDR correction (adjusted P < 0.05).

These findings establish CD4/PD-1, CD8/TIM-3, and AFP as robust and complementary prognostic biomarkers in HCV-related HCC, with clinically relevant cut-offs enhancing mortality risk stratification in Egyptian patients.

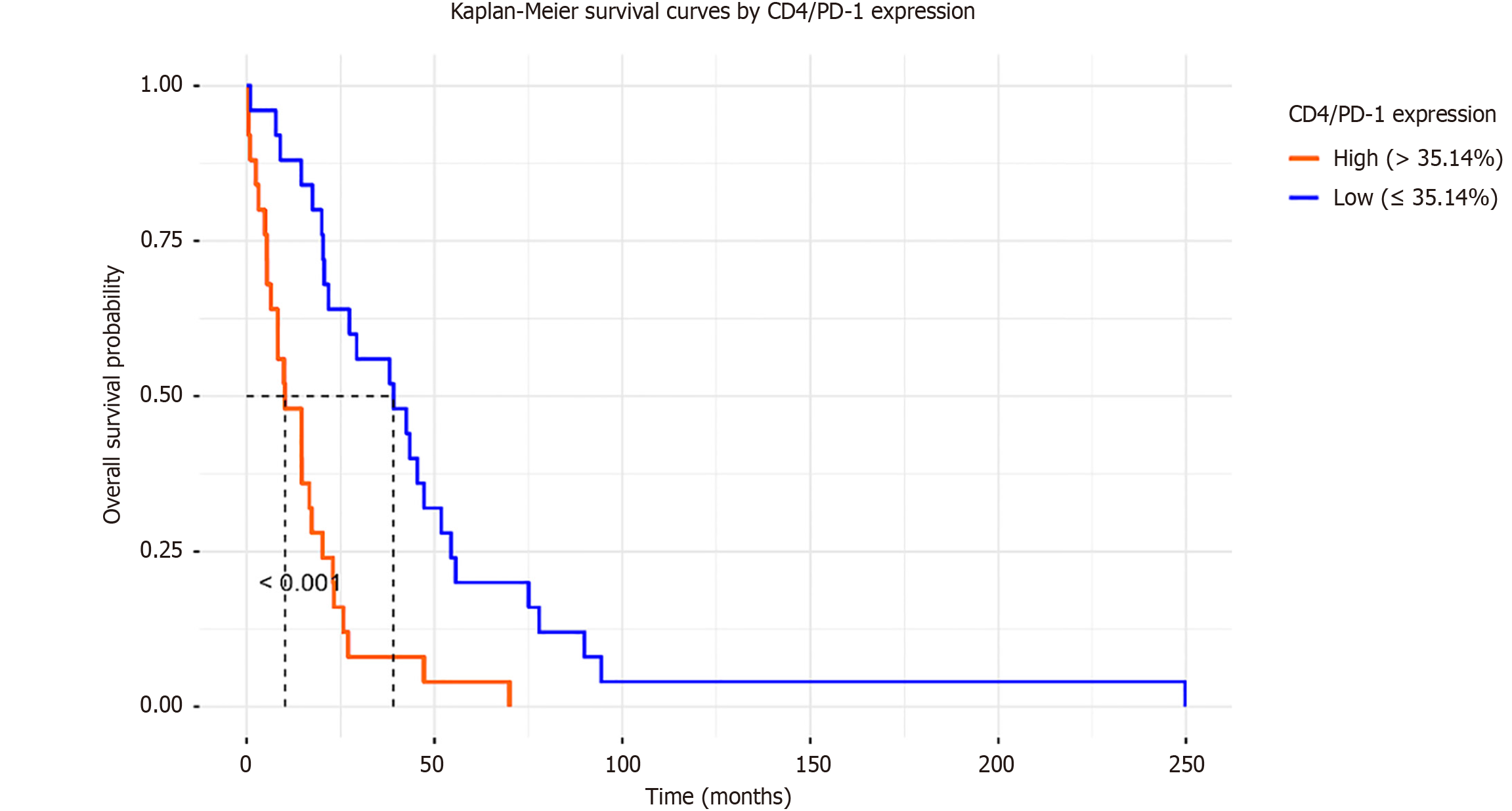

Survival analysis was conducted to evaluate the impact of immune checkpoint expression on the prognosis of HCC. Kaplan-Meier curves, stratified by median CD4/PD-1 expression (cutoff 35.14), showed significantly shorter survival in the high-expression group (median survival 12 months) compared to the low-expression group (median survival 24 months; log-rank P < 0.001; Figure 8).

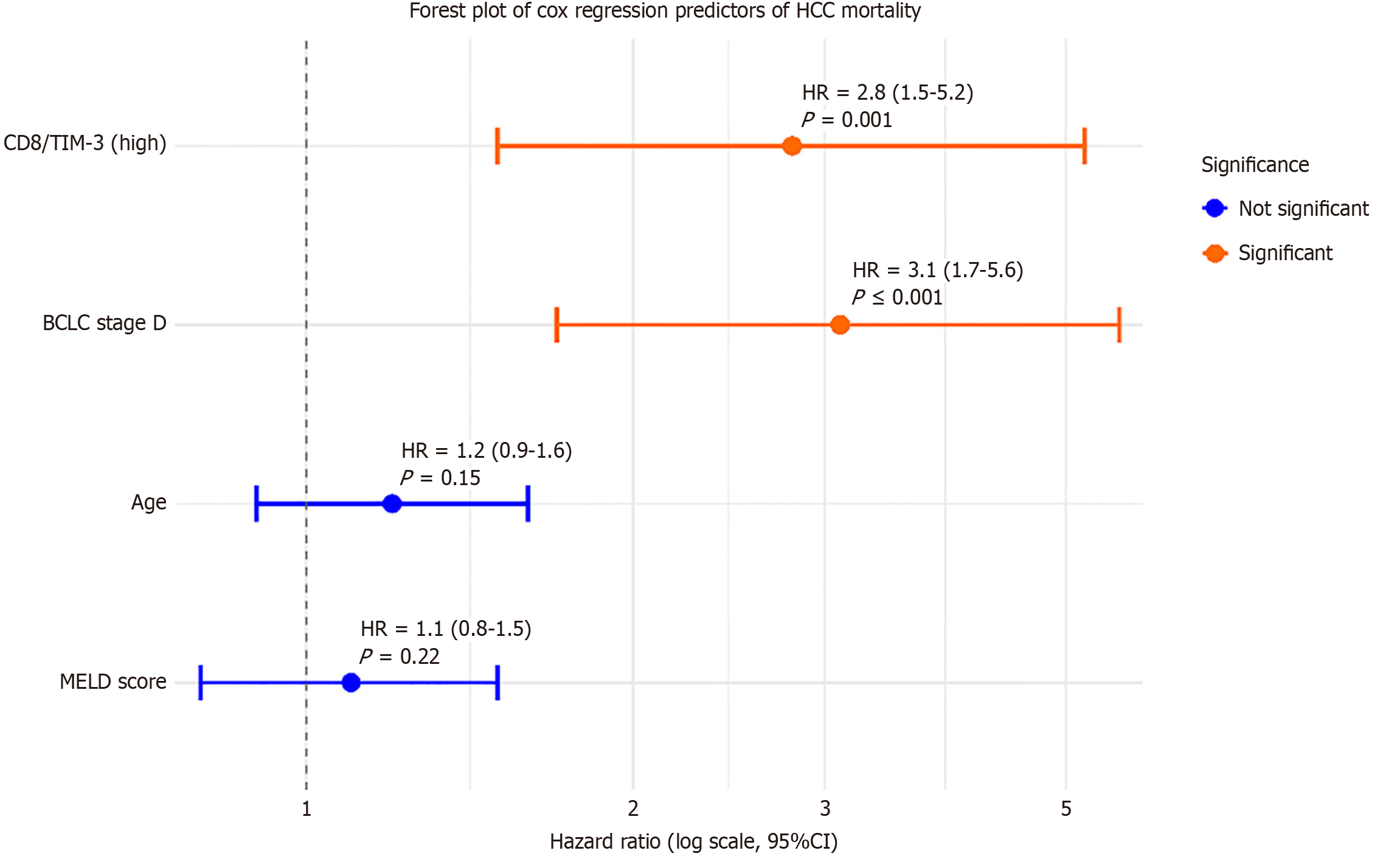

Cox proportional hazards regression, adjusted for age, BCLC stage, and MELD score, identified high CD8/TIM3 expression (HR = 2.8, 95%CI: 1.5-5.2, P = 0.001) and BCLC stage D (HR = 3.1, 95%CI: 1.7-5.6, P < 0.001) as independent predictors of mortality (Table 9). These results are displayed in a forest plot (Figure 9), highlighting the relative contribution of immune checkpoint markers and clinical variables.

Correlation network analysis visualized interactions between immune checkpoints, AFP, and clinical variables. In HCC, CD4/PD-1, CD8/PD-1, CD4/TIGIT, CD8/TIGIT, CD4/TIM3, and CD8/TIM3 formed a tightly connected cluster (r > 0.80, P < 0.001), strongly linked to AFP and BCLC stage (r = 0.75-0.86, P < 0.001) but negatively to MELD score (r = -0.73 to -0.76, P < 0.001). In cirrhosis, checkpoints correlated with MELD and Child-Pugh class (r > 0.88, P < 0.001) but not with AFP, indicating distinct patterns. Mediation analysis explored whether CD4/PD-1 mediated the AFP-mortality re

All reported P-values were corrected for multiple testing using the Benjamini-Hochberg FDR method; only associations remaining significant at FDR-adjusted P < 0.05 are shown.

Subgroup analysis by BCLC stage explored stage-specific immune profiles (Table 11). BCLC stage distribution (18% A, 2% B, 16% C, 64% D; Table 4) informed the subgrouping. Patients with advanced BCLC stages C/D (n = 40) had higher CD4/PD-1 (36.0 ± 0.4 vs 33.5 ± 0.5), CD8/TIM3 (17.8 ± 0.4 vs 15.5 ± 0.5), and AFP (median: 14000 ng/mL vs 10000 ng/mL) compared to early stages A/B (n = 10; P < 0.001, t-test/Mann-Whitney). Mortality was higher in C/D (40% vs 10%; P = 0.04, χ2), reinforcing that immune checkpoint overexpression escalates with tumor progression, aligning with global HCC findings. Etiology was controlled by including only HCV-positive HCC patients, confirmed by quantitative HCV PCR.

All reported p-values were corrected for multiple testing using the Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR) method; only associations remaining significant at FDR-adjusted P < 0.05 are shown.

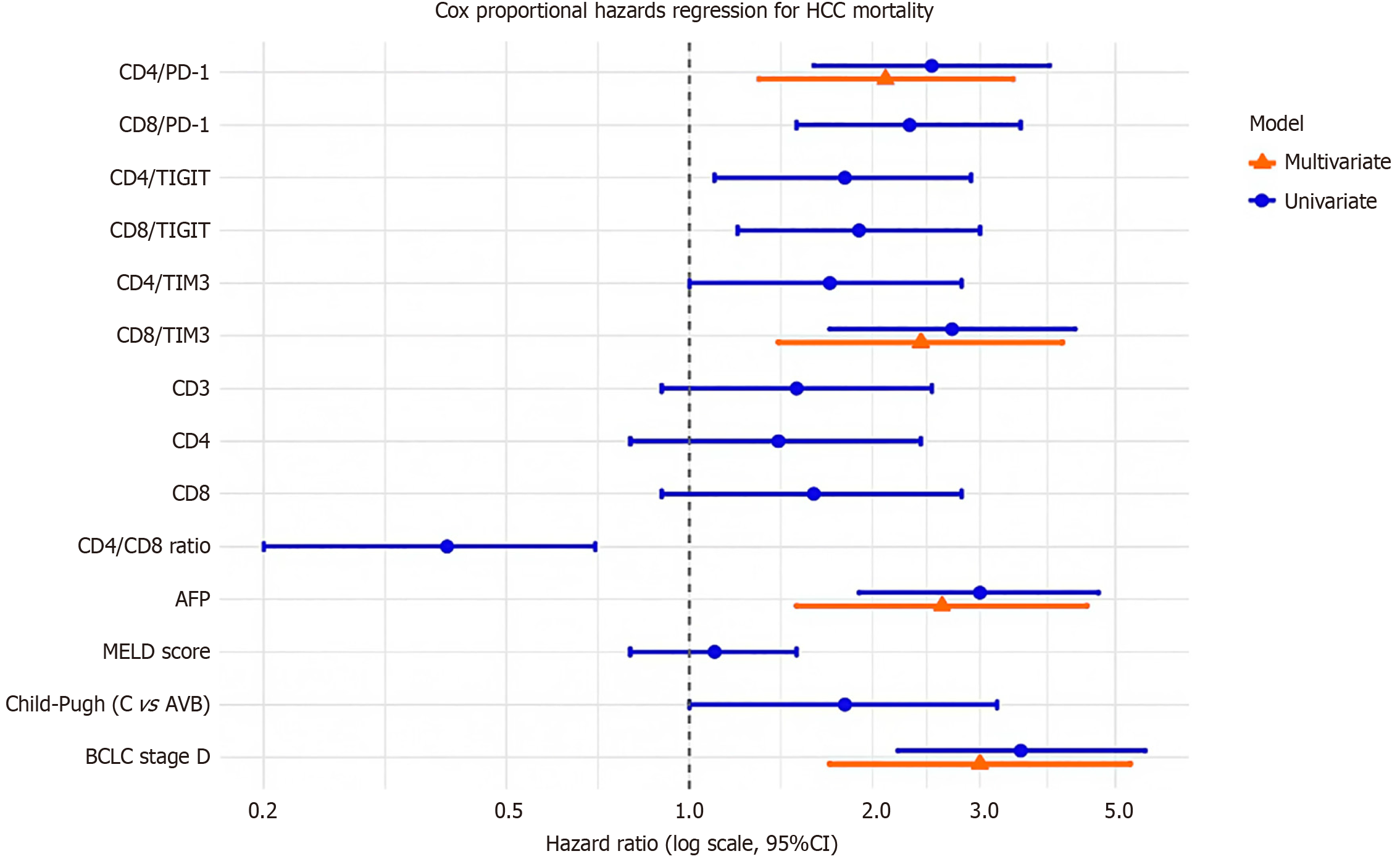

To further elucidate prognostic factors, univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression assessed overall survival in HCC patients (Figure 10; Table 12). Univariate analysis identified significant associations with mortality for CD4/PD-1 (HR = 2.5, 95%CI: 1.6-3.9, P < 0.001), CD8/PD-1 (HR = 2.3, 95%CI: 1.5-3.5, P < 0.001), CD8/TIM3 (HR = 2.7, 95%CI: 1.7-4.3, P < 0.001), AFP (HR = 3.0, 95%CI: 1.9-4.7, P < 0.001), CD4/CD8 ratio (HR = 0.4, 95%CI: 0.2-0.7, P = 0.002), and BCLC stage D (HR = 3.5, 95%CI: 2.2-5.6, P < 0.001). In multivariate analysis, adjusting for all variables, (CD4/PD-1, CD8/PD-1, CD4/TIGIT, CD8/TIGIT, CD4/TIM3, CD8/TIM3, CD3, CD4, CD8, CD4/CD8 ratio, AFP, MELD score, Child-Pugh class, BCLC stage), CD4/PD-1 (HR = 2.1, 95%CI: 1.3-3.4, P = 0.002), CD8/TIM3 (HR = 2.4, 95%CI: 1.4-4.1, P = 0.001), AFP (HR = 2.6, 95%CI: 1.5-4.5, P < 0.001), and BCLC stage D (HR = 3.0, 95%CI: 1.7-5.3, P < 0.001) remained independent predictors. MELD score was non-significant (HR = 1.1, P = 0.53), likely due to low scores (mean 2.5-2.56, pending verification; Table 3).

| Variable | Univariate HR (95%CI) | P value | Multivariate HR (95%CI) | P value |

| CD4/PD-1 (%) | 2.5 (1.6-3.9) | < 0.001c | 2.1 (1.3-3.4) | 0.002b |

| CD8/PD-1 (%) | 2.3 (1.5-3.5) | < 0.001c | ||

| CD4/TIGIT (%) | 1.8 (1.1-2.9) | 0.015a | ||

| CD8/TIGIT (%) | 1.9 (1.2-3.0) | 0.008b | ||

| CD4/TIM3 (%) | 1.7 (1.0-2.8) | 0.045a | ||

| CD8/TIM3 (%) | 2.7 (1.7-4.3) | < 0.001c | 2.4 (1.4-4.1) | 0.001b |

| CD3 (%) | 1.5 (0.9-2.5) | 0.12 | ||

| CD4 (%) | 1.4 (0.8-2.4) | 0.23 | ||

| CD8 (%) | 1.6 (0.9-2.8) | 0.09 | ||

| CD4/CD8 ratio | 0.4 (0.2-0.7) | 0.002b | ||

| AFP (ng/mL) | 3.0 (1.9-4.7) | < 0.001c | 2.6 (1.5-4.5) | < 0.001c |

| MELD score | 1.1 (0.8-1.5) | 0.53 | ||

| Child-Pugh class (C vs A/B) | 1.8 (1.0-3.2) | 0.048a | ||

| BCLC stage (D vs A-C) | 3.5 (2.2-5.6) | < 0.001c | 3.0 (1.7-5.3) | < 0.001c |

All reported P-values were corrected for multiple testing using the Benjamini-Hochberg FDR method; only associations remaining significant at FDR-adjusted P < 0.05 are shown.

These findings highlight CD4/PD-1, CD8/TIM3, AFP, and BCLC stage D as key survival predictors, supporting their use in risk stratification. Etiology was controlled by including only HCV-positive HCC patients, confirmed by qu

HCC remains one of the most lethal cancers globally, with Egypt bearing a disproportionate burden due to the historically high prevalence of HCV. Despite the remarkable success of national antiviral programs, HCV-related HCC continues to present at advanced stages with poor outcomes[1-5]. In this study, we comprehensively evaluated immune exhaustion markers, PD-1, TIGIT, and TIM-3, across different stages of HCV-related liver disease in Egyptian patients and explored their associations with liver function, tumor characteristics, and prognosis using advanced statistical and machine learning approaches. By integrating immunophenotyping with clinical outcomes, this work provides novel insight into the immune-oncological landscape of HCV-related HCC in a high-risk population.

To enhance clarity and ensure a deeper scientific interpretation, the discussion is organized thematically and aligned with the results presented in our tables and figures. Each theme synthesizes the key findings into a coherent narrative, followed by an expanded interpretation that integrates mechanistic insights and situates our results within the context of both Egyptian and international literature.

Our analysis demonstrated that age and sex distribution were comparable across groups (Table 1), minimizing demographic confounding and confirming that subsequent immune differences are primarily disease-related. The progressive deterioration of liver function tests from chronic HCV to cirrhosis and HCC reflects the natural trajectory of hepatocarcinogenesis, where persistent viral injury and fibrosis culminate in hepatic decompensation and malignant transformation. Most HCC patients presented with large tumors and advanced BCLC stage D disease, and approximately one-third did not survive follow-up (Table 4).

These findings mirror the broader Egyptian experience. Several national studies have shown that despite the implementation of HCC surveillance strategies, a considerable proportion of patients still present with large, multifocal lesions and advanced-stage disease[16,17]. This late presentation has been attributed to limitations in surveillance coverage, patient adherence, and the diagnostic performance of ultrasound in resource-limited settings. Notably, Rashed et al[17] reported that more than half of Egyptian HCC cases were detected beyond the window of curative therapy, a trend echoed by other Middle Eastern and North African cohorts.

The demographic homogeneity across groups in our study also provides an important methodological strength. Age and sex are known modulators of immune responses, with older patients demonstrating increased immune senescence and females often mounting stronger T-cell responses than males[18]. By controlling for these variables, our study ensures that differences in immune checkpoint expression more accurately reflect the underlying disease biology rather than host demographic variability.

Internationally, the predominance of advanced-stage tumors at diagnosis is a well-documented challenge, though the problem is particularly pronounced in Egypt, where HCV-driven hepatocarcinogenesis has historically accounted for the world’s highest HCC incidence[19]. In a recent population-based study, Kandeel et al[15] underscored that although Egypt’s mass HCV treatment campaigns have significantly reduced viral prevalence, the burden of cirrhosis and subsequent HCC remains high, with many patients still reaching medical care at stages beyond curative intervention.

Taken together, Tables 1 and 4 provide the clinical backdrop against which immune exhaustion in HCC must be interpreted. The consistent finding of large tumors and late-stage presentation emphasizes the pressing need for earlier, non-invasive biomarkers. In this context, immune checkpoint expression profiling may complement or even surpass AFP and imaging in identifying high-risk patients before their disease becomes clinically advanced.

Our findings reveal a progressive increase in PD-1, TIGIT, and TIM-3 expression across CD4+ T cell and CD8+ T cell, beginning with chronic HCV infection, rising with cirrhosis, and peaking in HCC (Table 2). Importantly, while cirrhosis and HCC patients had comparable MELD and Child-Pugh scores (Table 3), checkpoint expression was significantly higher in HCC, suggesting tumor-specific immune suppression not captured by conventional liver function scores. Within the HCC cohort, checkpoint expression correlated positively with Child-Pugh class, AFP levels, and BCLC stage (Table 5), whereas in cirrhosis, it correlated with MELD and Child-Pugh but not AFP (Table 6). Stage-wise analysis confirmed that immune exhaustion was most pronounced in advanced BCLC C/D disease (Table 11).

This integrated picture indicates that immune exhaustion emerges during chronic liver injury, intensifies with cirrhosis, and becomes accentuated in the presence of malignancy[20]. The lack of AFP association in cirrhosis but strong correlation in HCC reinforces that checkpoint upregulation in cancer is not merely a byproduct of hepatic dysfunction, but a tumor-driven adaptation to evade immune surveillance[21]. Mechanistically, chronic antigen stimulation in HCV infection leads to PD-1 upregulation, which is initially reversible but progresses to irreversible T cell dysfunction with co-expression of TIGIT and TIM-3[22].

Egyptian studies corroborate our findings. Salem and El-Badawy[23] showed that PD-1 expression is significantly higher in HCC compared to cirrhosis, independent of Child-Pugh classification. Helmy et al[24] further demonstrated that PD-1 and TIM-3 expression correlate with advanced HCC stages and worse prognosis in Egyptian patients. Internationally, Wherry and Kurachi[22] established that co-expression of PD-1, TIGIT, and TIM-3 defines terminal exhaustion, a phenotype strongly associated with tumor progression and resistance to therapy.

Together, these results highlight immune exhaustion as a biological continuum that mirrors disease evolution. Traditional liver scores (MELD, Child-Pugh) reflect hepatic synthetic capacity, but immune checkpoint expression reflects the parallel immunological decline that facilitates tumor immune escape. Integrating both may therefore provide a more holistic understanding of HCV-related HCC progression[25].

Integration of survival analyses confirms that immune checkpoint expression is not only a marker of tumor presence but also a determinant of outcome. Non-survivors exhibited higher PD-1, TIGIT, and TIM-3 Levels, as well as elevated AFP, compared with survivors (Table 7). Random forest modeling identified CD4/PD-1, CD8/TIM-3, and AFP as the top mortality predictors, while logistic regression confirmed CD4/PD-1, CD8/TIM-3, and BCLC stage D as independent predictors (Table 8). Cox regression (Tables 9 and 12) further validated CD8/TIM-3 and advanced BCLC stage as independent predictors of survival.

This convergence across multiple analytic approaches underscores the robustness of immune exhaustion as a prognostic driver. ROC analyses revealed excellent discrimination (AUC > 0.9 for CD4/PD-1 and AFP), with combinations outperforming single markers, highlighting the potential of multi-parameter prognostic models. Egyptian data support this prognostic role: Helmy et al[24] observed that PD-1 and TIM-3 expression were independently associated with poor survival. Globally, studies by Zhou et al[26] and Zhang et al[27] similarly showed that PD-1+/TIM-3+ T cells within tumors strongly predict reduced survival and therapeutic resistance.

Importantly, our use of machine learning adds an innovative layer, confirming checkpoint expression as a dominant mortality predictor. Such computational approaches are increasingly adopted in oncology for precision risk stratification[28]. The convergence of traditional statistics and machine learning in our dataset strengthens the argument for incorporating immune checkpoint profiling into prognostic models alongside AFP and BCLC stage.

One of this study’s novel contributions is demonstrating the interplay between AFP and immune checkpoint expression. AFP was elevated in HCC patients (Table 2) and strongly correlated with checkpoint expression and BCLC stage (Table 5). Mediation analysis (Table 10) revealed that CD4/PD-1 partially mediated the relationship between AFP and mortality, suggesting that part of AFP’s prognostic effect operates through immune-exhaustion pathways.

This provides mechanistic insight into AFP biology. Traditionally viewed as a marker of tumor burden, AFP has been shown to impair dendritic cell maturation and suppress T-cell activation, thereby directly contributing to immune tolerance[29]. Our results empirically validate this immunomodulatory role by linking AFP-driven mortality to PD-1 upregulation. Egyptian studies have also noted combined elevations of AFP and PD-1 in advanced HCC, though without formal mediation analysis[30-32]. International evidence supports the idea that high AFP levels predict poor response to immune checkpoint inhibitors, underscoring AFP’s functional role in shaping immune responsiveness[33]. Thus, AFP should not be considered in isolation as a tumor marker, but rather as part of a biological axis integrating tumor proliferation, immune suppression, and prognosis. Our mediation findings support the combined use of AFP and checkpoint expression for risk assessment and suggest that patients with high AFP and PD-1/TIM-3 co-expression may particularly benefit from dual biomarker-driven stratification.

Taken together, our findings highlight immune exhaustion as the biological axis linking chronic HCV, cirrhosis, tumor progression, and patient mortality. The implications are manifold. First, checkpoint expression may serve as an early detection tool in high-risk cirrhotic. Since upregulation begins before HCC onset (Tables 2 and 6), longitudinal immune profiling could identify patients transitioning from cirrhosis to malignancy. Second, checkpoint expression provides prognostic value beyond classical scores, as CD4/PD-1 and CD8/TIM-3 consistently predicted mortality independently of established clinical parameters (Tables 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, and 12). Third, the synergy between AFP and checkpoint expression suggests that combined biomarker strategies could refine surveillance and therapeutic decisions. Finally, the therapeutic implications are profound. The strong co-expression of PD-1, TIGIT, and TIM-3 supports the rationale for dual or triple checkpoint blockade, which is under active clinical investigation[34].

In the Egyptian context, where HCV-driven HCC remains a major public health challenge, incorporating immune biomarkers into surveillance and treatment algorithms could optimize patient selection for curative therapies and immunotherapy trials. Globally, these results add to the evidence that immune exhaustion markers are not only mechanistic hallmarks but also clinically actionable tools in the management of HCC.

This study is the first to comprehensively characterize immune checkpoint expression (PD-1, TIGIT, TIM-3) on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in Egyptian patients with HCV-related HCC, a population with one of the highest HCV prevalence rates globally. We identified a pronounced and specific upregulation of key exhaustion markers, particularly CD4/PD-1 and CD8/TIM-3, in HCC patients compared to other disease stages (Table 2). This distinct immune signature, coupled with its strong association with advanced tumor stage and mortality (Tables 5 and 7), and its validation as a top-tier prognostic biomarker through advanced machine learning (Table 8), provides novel insights into immune exhaustion in this unique epidemiological setting. Our findings thus highlight the distinct immune landscape of HCV-related HCC in Egypt, addressing a critical gap in regional data and contributing to global HCC immunology.

Compared to Asian and Western cohorts, where AFP and PD-1 alone have shown moderate predictive value, our findings demonstrate that combining AFP with CD8/TIM-3 yields superior prognostic accuracy (AUC = 0.95). This suggests that immune exhaustion profiling may be particularly informative in high-HCV-prevalence populations such as Egypt.

The consistent identification of CD4/PD-1 and CD8/TIM-3 as robust and independent predictors of HCC mortality across multiple analytical frameworks (Tables 8, 9, and 12) underscores their premier potential as prognostic biomarkers, particularly in advanced disease (Table 11). Furthermore, our mediation analysis established CD4/PD-1 as a significant partial mediator of AFP’s prognostic impact (Table 10), uncovering a key mechanistic link between tumor burden and immune suppression and offering a novel foundation for personalized immunotherapy. Collectively, these findings are scientifically significant as they not only validate immune checkpoints as therapeutic targets in HCV-related HCC but also specifically support the development of dual PD-1/TIM-3 blockade strategies, especially in high-HCV settings like Egypt. The integration of machine learning and advanced survival analyses in this work enhances the precision of risk stratification, thereby paving the way for integrating immune profiling into clinical practice to improve HCC outcomes. Importantly, to minimize the risk of false positives due to multiple testing, we applied FDR correction, and all reported associations remained robust after adjustment. This strengthens the reliability of our findings and their potential clinical applicability.

This study has several limitations. First, its cross-sectional design precludes assessment of longitudinal changes in immune checkpoint expression, and the single-center Egyptian cohort (n = 200) may restrict external generalizability. Second, although machine learning analyses yielded valuable prognostic insights, the absence of external validation limits their predictive applicability. Third, functional T-cell assays (e.g., cytokine production or cytotoxicity) were not performed, which restricts the mechanistic interpretation of checkpoint-mediated immune suppression. Furthermore, our cohort was restricted to Egyptian patients with HCV genotype 4. While this homogeneity enhances internal validity, it may limit extrapolation to HCC of other etiologies (e.g., hepatitis B virus or non-alcoholic steatohepatitis).

Based on these limitations, future research should prioritize longitudinal designs to capture immune dynamics, incorporate functional assays to clarify suppression mechanisms, and validate our predictive models in independent, multi-ethnic cohorts. Ultimately, our findings provide a strong rationale for clinical trials evaluating dual PD-1/TIM-3 blockade in high-expression subgroups, particularly in high-HCV-prevalence regions. Integrating genetic and viral determinants may further refine these biomarker-guided therapeutic strategies.

T cell exhaustion markers are markedly elevated in Egyptian patients with HCV-related HCC and strongly correlate with disease severity and survival. CD4/PD-1 and CD8/TIM-3 emerged as independent prognostic biomarkers, while me

By integrating survival modeling, machine learning, and mediation analysis, this study demonstrates that T cell exhaustion markers represent not only mechanistic hallmarks of HCV-related HCC but also clinically relevant prognostic biomarkers and potential therapeutic targets. To our knowledge, this is the first study in an Egyptian HCV-HCC cohort to combine immune exhaustion profiling with advanced statistical modeling, providing insights that extend beyond traditional biomarker approaches. Future studies should validate these results in larger, multi-ethnic cohorts and explore PD-1/TIM-3-TIM-3-directed immunotherapeutic strategies, with emphasis on high-expression subgroups and longitudinal immune dynamics to optimize clinical outcomes.

| 1. | Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75126] [Cited by in RCA: 68764] [Article Influence: 13752.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (202)] |

| 2. | Sharaf AL, Elbadrawy EG, Mohammed AMA, Abd Almonem N. Frequency of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Cirrhotic Patients after Chronic Hepatitis C Infection Treatment with Direct-Acting Antivirals. Afro-Egypt J Infect Endem Dis. 2022;12:16-23. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 3. | El Behery M, Elghwab AI, Tabll A, El-Sayed EH, Abdelrazek MA. Review Article: Egyptian Efforts to Control Hepatitis C Virus in Egypt. Alfarama J Basic Appl Sci. 2025;6:253-262. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 4. | Waked I, Esmat G, Elsharkawy A, El-Serafy M, Abdel-Razek W, Ghalab R, Elshishiney G, Salah A, Abdel Megid S, Kabil K, El-Sayed MH, Dabbous H, El Shazly Y, Abo Sliman M, Abou Hashem K, Abdel Gawad S, El Nahas N, El Sobky A, El Sonbaty S, El Tabakh H, Emad E, Gemeah H, Hashem A, Hassany M, Hefnawy N, Hemida AN, Khadary A, Labib K, Mahmoud F, Mamoun S, Marei T, Mekky S, Meshref A, Othman A, Ragab O, Ramadan E, Rehan A, Saad T, Saeed R, Sharshar M, Shawky H, Shawky M, Shehata W, Soror H, Taha M, Talha M, Tealaab A, Zein M, Hashish A, Cordie A, Omar Y, Kamal E, Ammar I, AbdAlla M, El Akel W, Doss W, Zaid H. Screening and Treatment Program to Eliminate Hepatitis C in Egypt. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1166-1174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 185] [Cited by in RCA: 197] [Article Influence: 32.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ezzat R, Eltabbakh M, El Kassas M. Unique situation of hepatocellular carcinoma in Egypt: A review of epidemiology and control measures. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2021;13:1919-1938. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Wherry EJ. T cell exhaustion. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:492-499. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2481] [Cited by in RCA: 3197] [Article Influence: 213.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Rehermann B, Nascimbeni M. Immunology of hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus infection. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:215-229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1202] [Cited by in RCA: 1225] [Article Influence: 58.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Mehdizadeh S, Bayatipoor H, Pashangzadeh S, Jafarpour R, Shojaei Z, Motallebnezhad M. Immune checkpoints and cancer development: Therapeutic implications and future directions. Pathol Res Pract. 2021;223:153485. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Yan Z, Wang C, Wu J, Wang J, Ma T. TIM-3 teams up with PD-1 in cancer immunotherapy: mechanisms and perspectives. Mol Biomed. 2025;6:27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | El-Khoueiry AB, Sangro B, Yau T, Crocenzi TS, Kudo M, Hsu C, Kim TY, Choo SP, Trojan J, Welling TH Rd, Meyer T, Kang YK, Yeo W, Chopra A, Anderson J, Dela Cruz C, Lang L, Neely J, Tang H, Dastani HB, Melero I. Nivolumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (CheckMate 040): an open-label, non-comparative, phase 1/2 dose escalation and expansion trial. Lancet. 2017;389:2492-2502. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3278] [Cited by in RCA: 3456] [Article Influence: 384.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 11. | Joller N, Anderson AC, Kuchroo VK. LAG-3, TIM-3, and TIGIT: Distinct functions in immune regulation. Immunity. 2024;57:206-222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 139] [Article Influence: 69.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Zahran AM, Hetta HF, Rayan A, Eldin AS, Hassan EA, Fakhry H, Soliman A, El-Badawy O. Differential expression of Tim-3, PD-1, and CCR5 on peripheral T and B lymphocytes in hepatitis C virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma and their impact on treatment outcomes. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2020;69:1253-1263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Cevallos M, Egger M. STROBE (STrengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology). In: Moher D, Altman DG, Schulz KF, Simera I, Wager E. Guidelines for Reporting Health Research: A User's Manual. John Wiley & Sons, 2014. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 14. | Chevaliez S, Pawlotsky JM. Hepatitis C virus: virology, diagnosis and management of antiviral therapy. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:2461-2466. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kandeel A, Genedy M, El-Refai S, Funk AL, Fontanet A, Talaat M. The prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in Egypt 2015: implications for future policy on prevention and treatment. Liver Int. 2017;37:45-53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 150] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 18.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | El-Serag HB. Epidemiology of viral hepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:1264-1273.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2183] [Cited by in RCA: 2564] [Article Influence: 183.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 17. | Rashed WM, Kandeil MAM, Mahmoud MO, Ezzat S. Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC) in Egypt: A comprehensive overview. J Egypt Natl Canc Inst. 2020;32:5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 20.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Erbe R, Wang Z, Wu S, Xiu J, Zaidi N, La J, Tuck D, Fillmore N, Giraldo NA, Topper M, Baylin S, Lippman M, Isaacs C, Basho R, Serebriiskii I, Lenz HJ, Astsaturov I, Marshall J, Taverna J, Lee J, Jaffee EM, Roussos Torres ET, Weeraratna A, Easwaran H, Fertig EJ. Evaluating the impact of age on immune checkpoint therapy biomarkers. Cell Rep. 2021;36:109599. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Gomaa A, Gomaa M, Allam N, Waked I. Hepatitis C Elimination in Egypt: Story of Success. Pathogens. 2024;13:681. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Alsudaney M, Ayoub W, Kosari K, Koltsova E, Abdulhaleem MN, Adetyan H, Yalda T, Attia AM, Liu J, Yang JD. Pathophysiology of liver cirrhosis and risk correlation between immune status and the pathogenesis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatoma Res. 2025;11:7. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 21. | Seyhan D, Allaire M, Fu Y, Conti F, Wang XW, Gao B, Lafdil F. Immune microenvironment in hepatocellular carcinoma: from pathogenesis to immunotherapy. Cell Mol Immunol. 2025;22:1132-1158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 32.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Wherry EJ, Kurachi M. Molecular and cellular insights into T cell exhaustion. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15:486-499. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2189] [Cited by in RCA: 3485] [Article Influence: 316.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 23. | Salem ML, El-Badawy A. Programmed death-1/programmed death-L1 signaling pathway and its blockade in hepatitis C virus immunotherapy. World J Hepatol. 2015;7:2449-2458. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Helmy DO, Khattab F, Hegazy AE, Sabry RM. Immunohistochemical expression of immune check point protein PDL-1 in hepatocellular carcinoma denotes its prognostic significance and association with survival. J Immunoassay Immunochem. 2023;44:213-228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Fuster-Anglada C, Corominas J, Marsal A, Llarch N, Iserte G, Sanduzzi-Zamparelli M, Forner A, Ferrer-Fábrega J, Holguin V, Morales A, Saavedra C, Reig M, Boix L, Marí M, Díaz A. Lymphocyte exhaustion in hepatocellular carcinoma: a dynamic evolution across disease stages. Front Immunol. 2025;16:1611365. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Zhou G, Sprengers D, Boor PPC, Doukas M, Schutz H, Mancham S, Pedroza-Gonzalez A, Polak WG, de Jonge J, Gaspersz M, Dong H, Thielemans K, Pan Q, IJzermans JNM, Bruno MJ, Kwekkeboom J. Antibodies Against Immune Checkpoint Molecules Restore Functions of Tumor-Infiltrating T Cells in Hepatocellular Carcinomas. Gastroenterology. 2017;153:1107-1119.e10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 237] [Cited by in RCA: 335] [Article Influence: 37.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Zhang XS, Zhou HC, Wei P, Chen L, Ma WH, Ding L, Liang SC, Chen BD. Combined TIM-3 and PD-1 blockade restrains hepatocellular carcinoma development by facilitating CD4+ and CD8+ T cell-mediated antitumor immune responses. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2023;15:2138-2149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 28. | Esteva A, Robicquet A, Ramsundar B, Kuleshov V, DePristo M, Chou K, Cui C, Corrado G, Thrun S, Dean J. A guide to deep learning in healthcare. Nat Med. 2019;25:24-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1123] [Cited by in RCA: 1795] [Article Influence: 256.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Pardee AD, Butterfield LH. Immunotherapy of hepatocellular carcinoma: Unique challenges and clinical opportunities. Oncoimmunology. 2012;1:48-55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 25.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Kobeisy MA, Morsy KH, Galal M, Sayed SK, Ashmawy MM, Mohammad FM. Clinical significance of elevated alpha-foetoprotein (AFP) in patients with chronic hepatitis C without hepatocellular carcinoma in upper EGYPT. Arab J Gastroenterol. 2012;13:49-53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | El-Deeb S, Diab K, Mohasseb M, Elgazzar M, Khalifa A. Biomarker utility for early diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma in Egyptians with viral hepatitis C and B. Menoufia Med J. 2022;35:399. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 32. | Yameny AA, Alabd SF, Mansor MAM. Evaluation of AFP for diagnosis of HCC in Egyptian patients. J Med Life Sci. 2023;5:43-48. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 33. | Zhu AX, Kang YK, Yen CJ, Finn RS, Galle PR, Llovet JM, Assenat E, Brandi G, Pracht M, Lim HY, Rau KM, Motomura K, Ohno I, Merle P, Daniele B, Shin DB, Gerken G, Borg C, Hiriart JB, Okusaka T, Morimoto M, Hsu Y, Abada PB, Kudo M; REACH-2 study investigators. Ramucirumab after sorafenib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma and increased α-fetoprotein concentrations (REACH-2): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20:282-296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1027] [Cited by in RCA: 1315] [Article Influence: 187.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 34. | Sangro B, Sarobe P, Hervás-Stubbs S, Melero I. Advances in immunotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;18:525-543. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 264] [Cited by in RCA: 955] [Article Influence: 191.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/