Published online Jan 24, 2026. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v17.i1.113304

Revised: September 16, 2025

Accepted: December 1, 2025

Published online: January 24, 2026

Processing time: 151 Days and 16.7 Hours

Patients with esophageal cancer exhibit marked variability in prognosis, hi

To explore the triglyceride-glucose (TyG) index and its derivatives - indicators for insulin resistance, a core feature of metabolic syndrome. Given their controversial associations with cancer and limited research on their dynamic changes in ESCC patients post-treatment, this study aims to analyze these dynamic changes.

The present retrospective study analyzed 360 East Asian patients with ESCC who received definitive chemoradiotherapy to explore the associations of TyG, TyG-body weight, and TyG-body mass index (both pre- and post-treatment) with overall survival.

Elevated levels of post-treatment TyG and its derivatives (postTyG, postTyG-body weight, postTyG-body mass index) were significantly associated with a reduced risk of death, showing a superior prognostic value compared to the baseline levels (preTyG). Restricted cubic spline analysis confirmed the presence of non-linear or monotonic associations, with more pronounced correlations observed in male patients.

Post-treatment TyG and its derivatives may serve as independent prognostic indicators for East Asian patients with ESCC, providing a basis for personalized diagnosis and treatment.

Core Tip: This study shows post-treatment triglyceride-glucose (TyG) index and its derivatives (TyG-body weight, TyG-body mass index) correlate with lower death risk in East Asian esophageal squamous cell carcinoma patients after definitive chemoradiotherapy, outperforming pre-treatment levels (especially in males) and acting as independent prognostic indicators, which may guide prognosis stratification, treatment monitoring, offer novel insights into personalized management, and serve as a robust basis for clinical decision optimization.

- Citation: Xiao L, Liu YD, Zhang X, Zhang SC, Lyu JH. Post-treatment triglyceride-glucose index as survival protective factors in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. World J Clin Oncol 2026; 17(1): 113304

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-4333/full/v17/i1/113304.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5306/wjco.v17.i1.113304

Esophageal cancer (EC) ranks as the 11th most common malignancy and the 7th leading cause of cancer-related death globally. It exhibits distinct histopathological features across geographic regions, with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) predominating in East Asia, Southern Africa, and Eastern Africa, whereas esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC) being more prevalent in Western countries[1,2]. This geographic divergence reflects etiological heterogeneity, with regional variations in genetic backgrounds, dietary patterns, and lifestyle factors possibly shaping the metabolic profiles of these subtypes[3-5]. However, the mechanisms linking metabolic reprogramming in esophageal tumors to clinical prognosis remain poorly elucidated.

Metabolic syndrome (MetS), characterized by obesity, hypertension, hyperglycemia, and dyslipidemia[6,7], is centered on insulin resistance (IR), a which has been identified as a key driver of carcinogenesis and a valid tool for assessing cancer risk[8-11]. The triglyceride-glucose (TyG) index, a robust surrogate for IR, not only is associated with various cardiovascular and metabolic diseases but also has been linked to prognosis in several cancer types, including lung, breast, and prostate cancers, in recent studies[10-12]. However, critical inconsistencies persist. A cohort study of 3.52 million individuals analyzed the TyG index-mortality association. It showed a significant inverse L-shaped nonlinear correlation between TyG and all-cause/cardiovascular mortality: Death risk rose sharply when TyG exceeded thresholds (9.75 for all-cause, 9.85 for cardiovascular mortality). In contrast, TyG had a linear negative association with cancer mortality, with a slight but significant downward trend in cancer death risk as TyG increased[13]. Additionally, TyG and its derivatives reportedly are correlated with an increased EAC risk and a decreased ESCC risk, highlighting a “metabolic paradox” that warrants further validation[14].

Notably, current research presents several critical limitations. First, studies on the association between TyG and cancer prognosis remain scarce, particularly in EC. Second, only one study to date has explored the relationship between TyG and EC risk, focusing exclusively on European populations, leaving a gap in data from Asian cohorts[14]. Finally, most studies have focused solely on the baseline TyG levels, neglecting the prognostic value of the dynamic changes in the TyG levels before and after treatment - especially metabolic adaptive remodeling following intensive anti-tumor therapy[11-13].

Thus, the present study, focusing on East Asian ESCC patients, aimed to analyze the prognostic value of the dynamic changes in the levels of TyG and its derivatives across different treatment stages, as well as their distribution patterns across clinical characteristics. The study utilized Cox proportional hazards and restricted cubic spline models to evaluate the strength and non-linear relationships between these indices (at different stages) and overall survival (OS). Ultimately, stratified analyses by sex and treatment modality (chemotherapy alone vs chemoradiotherapy) were performed to clarify the heterogeneity in their prognostic value. The core objective of the present study was to elucidate the independent prognostic significance of post-treatment TyG (postTyG) and its derivatives in East Asian ESCC patients, providing a basis for optimizing the risk stratification systems and developing metabolism-based personalized diagnostic and therapeutic strategies.

The present retrospective study included 360 ESCC patients who underwent definitive chemoradiotherapy between 2012 and 2023. The eligibility criteria were as follows: (1) Histologically confirmed ESCC; (2) Unresectable tumor or patient refused surgery; (3) Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) score of ≥ 70; (4) Radiotherapy (RT) dose of ≥ 50 Gy; (5) Availability of fasting blood test data before and after treatment; (6) No distant metastasis at baseline; and (7) Tumor-node-metastasis staging based on the 7th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer classification.

All patients underwent RT. Spiral computed tomography (CT) simulation was performed for the tumor target volume and surrounding normal organ delineation. Concurrent chemotherapy was administered, with some patients receiving 1-6 cycles of platinum-based single-agent or combination chemotherapy, elderly patients being treated with oral S-1, and those intolerant to first-line chemotherapy receiving raltitrexed.

The patients’ clinical data, including age, sex, body weight, smoking and alcohol consumption status, body mass index (BMI), and chemoradiotherapy details, were extracted from their electronic medical records. For all participants, the serum biochemical parameters [triglycerides (TG), fasting glucose, total cholesterol (TC)] were collected before and after treatment, with the samples obtained after an overnight fast.

The following indices were calculated using the formulas below: TyG index (for male/female patients)[14]: TyG = ln[TG(mg/dL) × fasting glucose (mg/dL)/2]. TyG- body weight (BW) (for male/female patients): TyG-BW = TyG × BW. TyG-BMI (for male/female patients): TyG-BMI = TyG × BMI.

Follow-up evaluations were scheduled every 3 months in the first year, every 6 months in the next 2 years, and annually thereafter. The routine assessments included physical examination, blood tests, ultrasound examination, tumor marker assays, chest CT, and barium esophagography. All patients were followed up via outpatient visits or telephone calls.

This study performed statistical analyses and graphing using RStudio 4.3.1 software: For normally distributed continuous variables, Student’s t-test was applied for two-group comparisons while one-way analysis of variance was used for multi-group comparisons, and categorical variables were compared via the χ2 test; for continuous covariates at different treatment stages, optimal cutoff values were determined by combining the log-rank test with a stratified approach - first, the log-rank test was used to analyze survival differences of continuous variables, initially identifying critical intervals that could distinguish survival outcomes, and subsequently candidate cutoff values were further validated with clinical stratification factors (e.g., tumor stage, treatment modality) to finally confirm the cutoff value that maximized intergroup survival differences; to avoid overfitting, Bootstrap resampling (1000 iterations) was conducted for internal validation of these cutoff values; accordingly, patients were stratified into low-level and high-level groups according to the cutoff values, survival analysis was performed using the Kaplan-Meier method to generate survival curves (with intergroup differences compared via the log-rank test), univariate and multivariate analyses were carried out using the Cox proportional hazards regression model, and Pearson correlation analysis was applied to investigate the associations between relevant indicators and clinical/metabolic parameters (correlation strength was defined as follows: Negligible correlation (r < ± 0.10), weak correlation (± 0.11, ± 0.39), moderate correlation (± 0.40, ± 0.69), strong correlation (± 0.70, ± 0.89), and very strong correlation (r > ± 0.90); a two-tailed P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

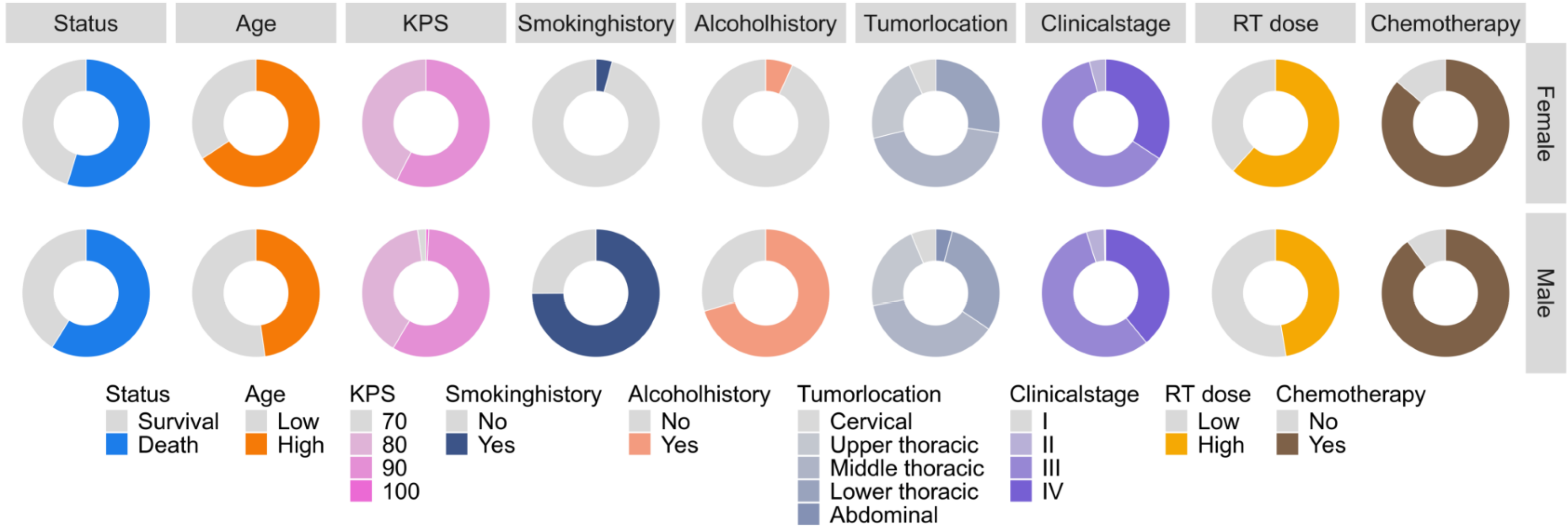

Altogether, 360 patients were enrolled; of these, 151 (41.9%) patients survived and 209 (58.1%) died at the last follow-up. The median OS for the entire cohort was 22.2 months [interquartile range (IQR): 12.0-38.8 months], with significantly longer OS in the survival group (38.6 months, IQR: 25.8-50.0 months) than in the deceased group (15.0 months, IQR: 8.5-23.2 months; P < 0.001). The cohort comprised 287 men (79.7%) and 73 women (20.3%), with a median age of 65 years (IQR: 58.8-70.0 years). No significant differences in smoking history (P = 0.924) or alcohol consumption (P = 0.409) were observed between the two groups. Most patients were diagnosed with stage III (57.2%) or IV (38.1%) disease; the survival group had a higher proportion of patients with stage I-II diseases, whereas the deceased group had a significantly higher proportion of patients with stage IV disease (P < 0.001). The median BMI was 21.6 kg/m2 (IQR: 19.9-23.9 kg/m2), with the survival group showing a higher BMI (P = 0.018). The fasting glucose levels before treatment were lower in the survival group (P = 0.047), whereas the pre-treatment TC and TG levels showed no between-group differences. After treatment, the survival group had significantly higher level of TC (P = 0.002), TG (P < 0.001), postTyG index, postTyG-BW, and postTyG-BMI (all P < 0.01), with no significant difference in the pre-treatment TyG (preTyG) levels observed between groups (Table 1, Figure 1).

| Characteristics | Overall | Survival | Death | P value |

| n | 360 | 151 (41.9) | 209 (58.1) | - |

| Survive time, median (IQR) | 22.2 (12, 38.78) | 38.57 (25.815, 50) | 15 (8.47, 23.17) | < 0.001 |

| Gender | 0.527 | |||

| Male | 287 (79.7) | 118 (32.8) | 169 (46.9) | |

| Female | 73 (20.3) | 33 (9.2) | 40 (11.1) | |

| Age, mean ± SD | 65 (58.75, 70) | 63.649 ± 7.5888 | 64.12 ± 9.497 | 0.602 |

| KPS | 0.006 | |||

| 70 | 6 (1.7) | 0 (0) | 6 (1.7) | |

| 80 | 144 (40) | 50 (13.9) | 94 (26.1) | |

| 90 | 208 (57.8) | 101 (28.1) | 107 (29.7) | |

| 100 | 2 (0.6) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.6) | |

| Smoking history | 0.924 | |||

| No | 142 (39.4) | 60 (16.7) | 82 (22.8) | |

| Yes | 218 (60.6) | 91 (25.3) | 127 (35.3) | |

| Alcohol history | 0.409 | |||

| No | 153 (42.5) | 68 (18.9) | 85 (23.6) | |

| Yes | 207 (57.5) | 83 (23.1) | 124 (34.4) | |

| Tumor location, median (IQR) | 2 (1, 3) | 2 (1, 3) | 2 (2, 3) | 0.036 |

| Clinical stage | < 0.001 | |||

| I | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0) | |

| II | 16 (4.4) | 12 (3.3) | 4 (1.1) | |

| III | 206 (57.2) | 106 (29.4) | 100 (27.8) | |

| IV | 137 (38.1) | 32 (8.9) | 105 (29.2) | |

| RT dose, median (IQR) | 65 (60, 66) | 60 (60, 66) | 66 (60, 66) | 0.001 |

| Chemotherapy | 0.029 | |||

| No | 39 (10.8) | 10 (2.8) | 29 (8.1) | |

| Yes | 321 (89.2) | 141(39.2) | 180 (50) | |

| BMI, median (IQR) | 21.6 (19.947, 23.885) | 22 (20.33, 24.17) | 21.11 (19.53, 23.44) | 0.018 |

| Pre-glucose, median (IQR) | 5.13 (4.71, 5.8225) | 5.03 (4.605, 5.78) | 5.24 (4.77, 5.84) | 0.047 |

| Pre-TC, median (IQR) | 4.725 (4.0475, 5.3625) | 4.82 (4.06, 5.425) | 4.69 (4.01, 5.3) | 0.410 |

| Pre-TG, median (IQR) | 1.13 (0.8975, 1.45) | 1.12 (0.9, 1.45) | 1.13 (0.89, 1.46) | 0.880 |

| Post-BMI, mean ± SD | 20.89 (19.325, 22.58) | 21.537 ± 2.6983 | 20.904 ± 2.6611 | 0.072 |

| Post-glucose, median (IQR) | 5.31 (4.81, 5.94) | 5.26 (4.825, 5.915) | 5.33 (4.8, 5.94) | 0.886 |

| Post-TC, median (IQR) | 4.48 (3.87, 5.29) | 4.64 (4.025, 5.525) | 4.26 (3.73, 5.17) | 0.002 |

| Post-TG, median (IQR) | 1.3 (0.9875, 1.67) | 1.43 (1.1, 1.775) | 1.23 (0.92, 1.53) | < 0.001 |

| PreTyG, median (IQR) | 8.4781 (8.1915, 8.7593) | 8.4357 (8.1754, 8.7729) | 8.5087 (8.207, 8.748) | 0.393 |

| PostTyG, mean ± SD | 9.8787 ± 0.31856 | 9.9299 ± 0.29319 | 9.8418 ± 0.33149 | 0.009 |

| PostTyG-BW, median (IQR) | 82.961 (73.243, 92.833) | 85.855 (74.724, 96.954) | 80.109 (72.236, 89.091) | 0.004 |

| PostTyG-BMI, median (IQR) | 214.85 (195.92, 234.25) | 218.76 (202.14, 237.33) | 211.38 (192.76, 230.09) | 0.006 |

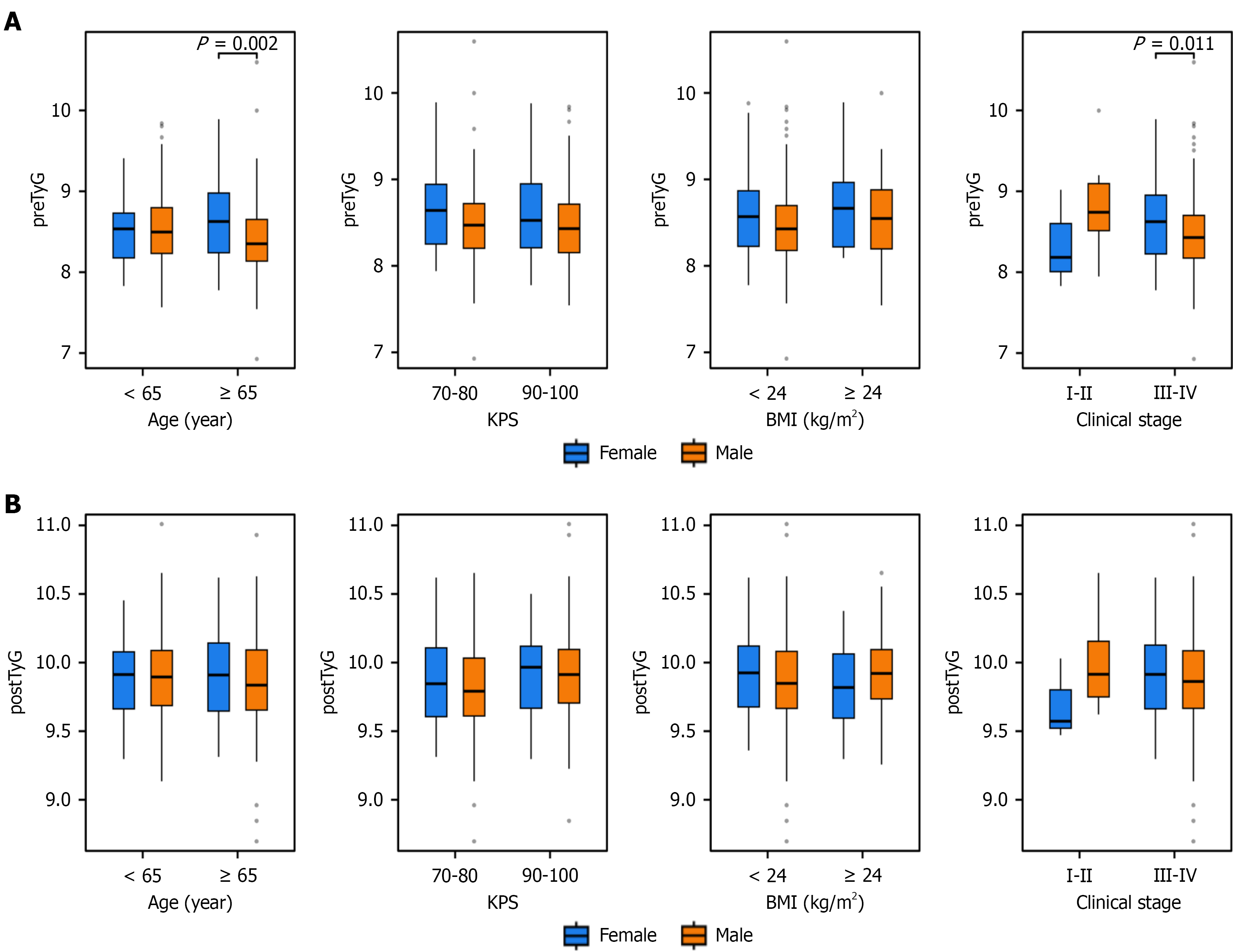

To explore the sex-specific effects on the TyG-related indices, we analyzed the distributions of preTyG, postTyG, postTyG-BW, and postTyG-BMI across the subgroups stratified by clinical features (age, KPS score, BMI, and TNM stage). Significant sex differences in preTyG levels were observed in the subgroups of age (< 65 years vs ≥ 65 years; P = 0.002), BMI (< 24 kg/m2vs ≥ 24 kg/m2; P = 0.045), and clinical stage (I-II vs III-IV; P = 0.011). PostTyG-BW showed significant sex differences across all subgroups (age, KPS score, BMI, and stage; all P < 0.05). For postTyG-BMI, significant sex differences were noted in age (< 65 years vs ≥ 65 years; P = 0.02), KPS score (70-80 vs 90-100; P = 0.02), and clinical stage (I-II: P = 0.047; III-IV: P = 0.006; Figure 2).

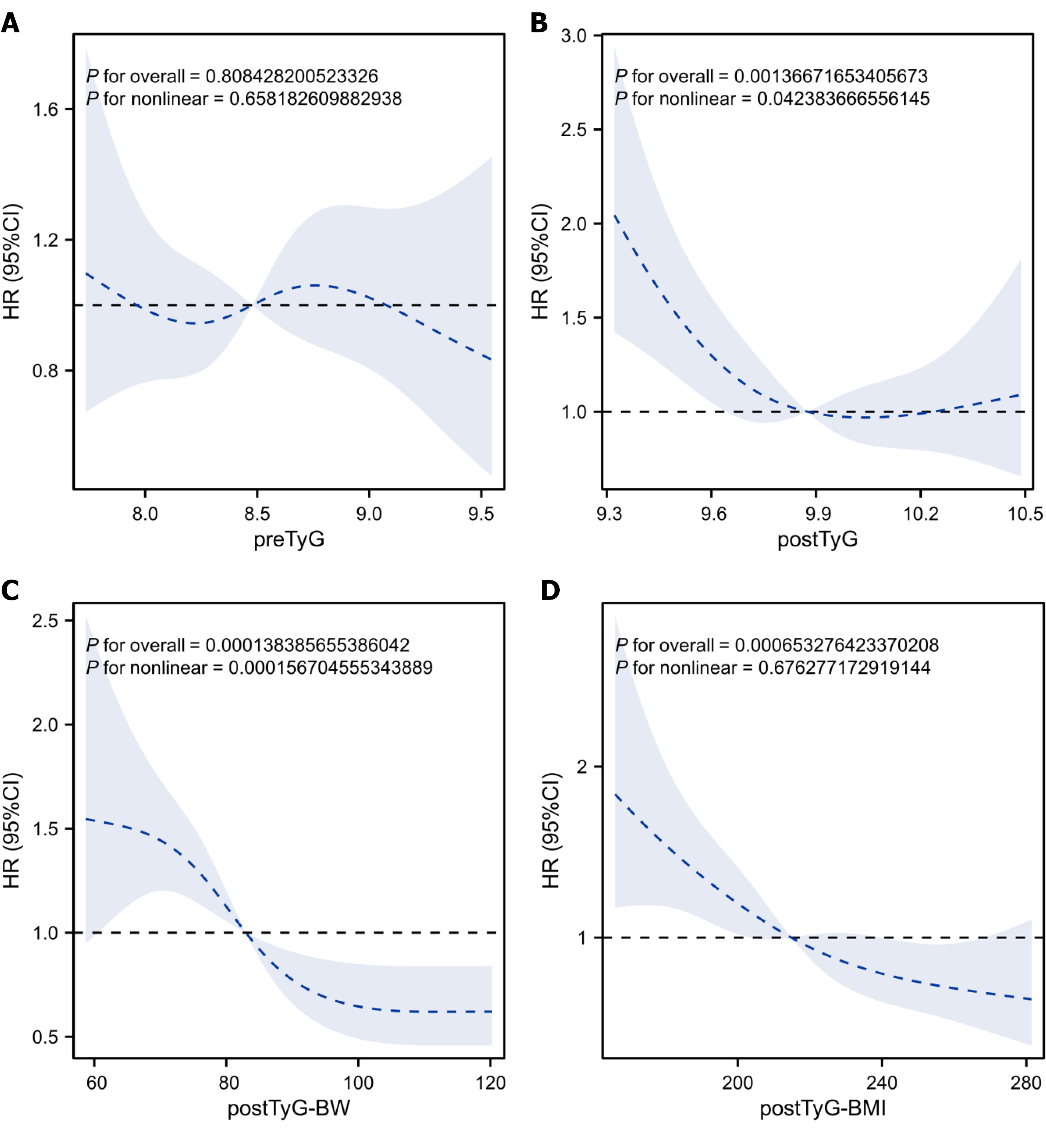

After adjusting for confounding factors (age, sex, KPS score, smoking/alcohol history, tumor location, TNM stage, and chemoradiotherapy), the restricted cubic spline plots revealed no significant dose-response relationship between preTyG and OS (overall P = 0.808; non-linear P = 0.698). Moreover, a reverse L-shaped non-linear association was found for postTyG (overall P = 0.001; non-linear P = 0.042), with postTyG of < 9.8 showing an association with an increased mortality risk [hazard risk (HR) > 1]. A monotonic decreasing association was noted for postTyG-BW (overall P < 0.001; non-linear P = 0.289), where the values of > 80 showed enhanced protective effects (decreasing HR with increasing postTyG-BW). A monotonic decreasing trend was observed for postTyG-BMI (overall P < 0.001; non-linear P = 0.078), with values of > 200 being identified as a protective factor for OS (Figure 3).

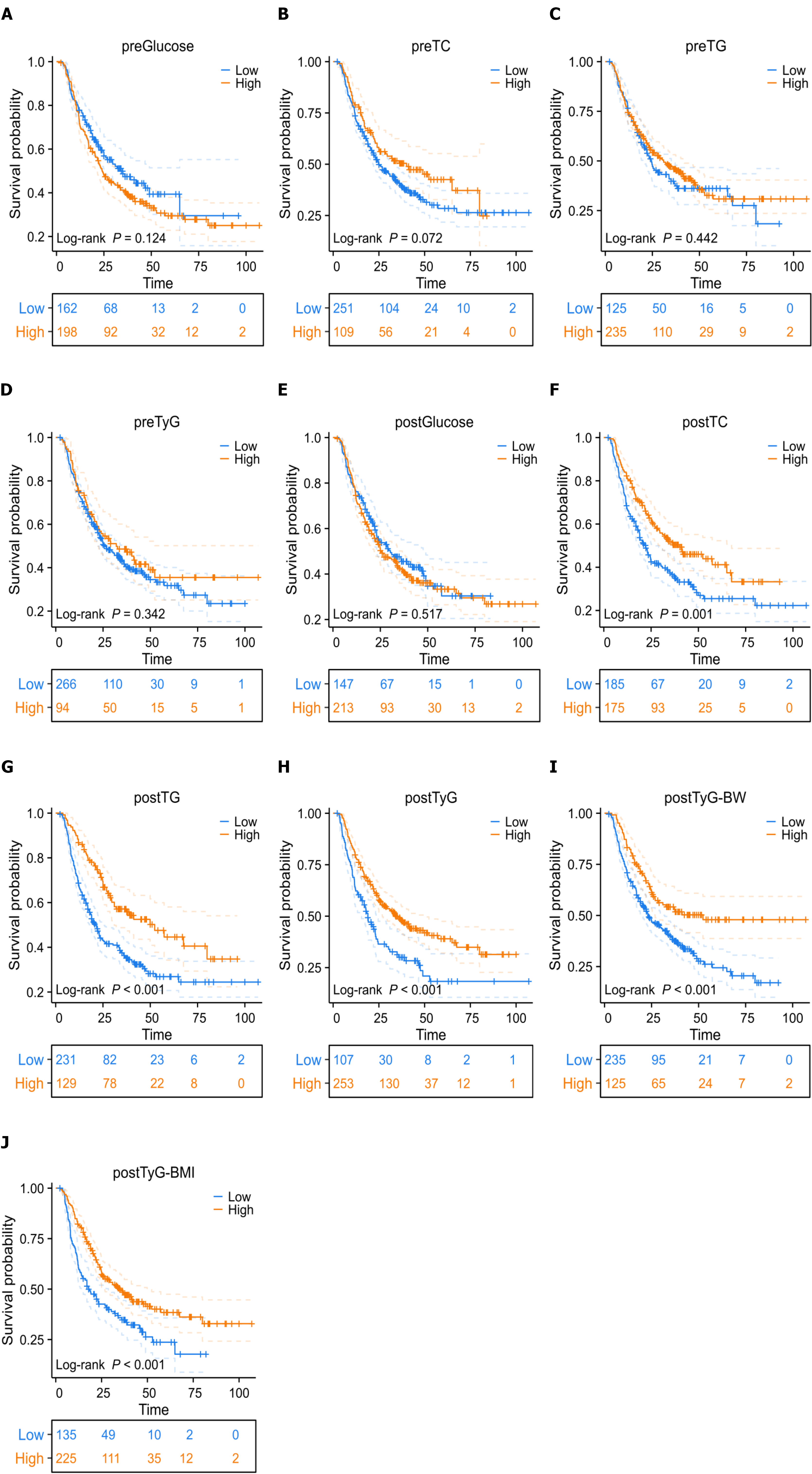

Kaplan-Meier analysis showed a median OS of 27.4 months for the entire cohort, with 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS rates of 75.2%, 43.7%, and 33.0%, respectively. For the subgroups stratified by pre-treatment indices, significant survival differences were observed for preTC (P = 0.072) and preTG (P = 0.042), but not for preGlucose (P = 0.124) or preTyG (P = 0.342). For the subgroups stratified by post-treatment indices, significant survival differences were noted for postTC (P = 0.001), postTG (P = 0.002), postTyG (P < 0.001), postTyG-BW (P < 0.001), and postTyG-BMI (P < 0.001), but not for postGlucose (P = 0.517). These findings highlight the superior prognostic value of post-treatment metabolic indices, particularly TyG derivatives (Figure 4).

The Pearson correlation analysis showed that, in the total cohort, postTyG was significantly correlated with clinical stage [R = -0.133, P = 0.012, false discovery rate (FDR) P = 0.036] and survival status (R = -0.125, P = 0.017, FDR P = 0.045) after FDR correction, while its correlation with survival time (r = 0.119, P = 0.023) became non-significant after correction. PostTyG-BW showed correlations with multiple features (e.g., clinical stage, BMI, survival time; all P < 0.05) before correction, but none remained significant after FDR adjustment. PostTyG-BMI remained significantly correlated with clinical stage (R = -0.221, P < 0.001, FDR P = 0.001), chemotherapy (r = 0.164, P = 0.002, FDR P = 0.033), BMI (r = 0.971, P < 0.001, FDR P < 0.001), survival time (r = 0.210, P < 0.001, FDR P = 0.014), and survival status (R = -0.146, P = 0.005, FDR P = 0.033) even after FDR correction. In men, postTyG was significantly correlated with clinical stage (R = -0.190, P = 0.001, FDR P = 0.008) after correction. PostTyG-BW only retained a significant correlation with BMI (r = 0.821, P < 0.001, FDR P = 0.033) after FDR adjustment. PostTyG-BMI remained significantly correlated with clinical stage (R = -0.222, P < 0.001, FDR P = 0.002), chemotherapy (r = 0.182, P = 0.002, FDR P = 0.033), BMI (r = 0.969, P < 0.001, FDR P < 0.001), survival time (r = 0.269, P < 0.001, FDR P = 0.002), and survival status (R = -0.152, P = 0.010, FDR P = 0.042) post-correction. In women, postTyG had no significant correlations. PostTyG-BW showed a correlation with BMI (r = 0.726, P < 0.001) and near-significant association with RT dose (R = -0.212, P = 0.071), but neither was significant after FDR correction. PostTyG-BMI only remained significantly correlated with BMI (r = 0.964, P < 0.001, FDR P < 0.001) after correction (Table 2).

| Group | TyG index | Clinical stage | RT dose | Chemotherapy | BMI | Survival time | Survival status | |

| Total patients | PostTyG | R | -0.133 | -0.024 | 0.079 | 0.049 | -0.125 | 0.119 |

| P value | 0.012 | 0.645 | 0.136 | 0.351 | 0.017 | 0.023 | ||

| FDR P value | 0.036 | 0.572 | 0.294 | 0.341 | 0.341 | 0.045 | ||

| PostTyG-BW | R | -0.218 | 0.052 | 0.133 | 0.787 | -0.151 | 0.2 | |

| P value | < 0.001 | 0.329 | 0.012 | < 0.001 | 0.004 | < 0.001 | ||

| FDR P value | 0.739 | 0.572 | 0.739 | 0.163 | 0.501 | 0.402 | ||

| PostTyG-BMI | R | -0.221 | 0.059 | 0.164 | 0.971 | -0.146 | 0.21 | |

| P value | < 0.001 | 0.264 | 0.002 | < 0.001 | 0.005 | < 0.001 | ||

| FDR P value | 0.001 | 0.46 | 0.033 | < 0.001 | 0.014 | 0.033 | ||

| Male | PostTyG | R | -0.19 | -0.016 | 0.096 | 0.075 | -0.115 | 0.142 |

| P value | 0.001 | 0.79 | 0.104 | 0.204 | 0.051 | 0.016 | ||

| FDR P value | 0.008 | 0.615 | 0.196 | 0.341 | 0.288 | 0.112 | ||

| PostTyG-BW | R | -0.245 | 0.072 | 0.174 | 0.821 | -0.163 | 0.257 | |

| P value | < 0.001 | 0.223 | 0.003 | < 0.001 | 0.006 | < 0.001 | ||

| FDR P value | 0.957 | 0.458 | 0.779 | 0.033 | 0.572 | 0.485 | ||

| PostTyG-BMI | R | -0.222 | 0.121 | 0.182 | 0.969 | -0.152 | 0.269 | |

| P value | < 0.001 | 0.04 | 0.002 | < 0.001 | 0.01 | < 0.001 | ||

| FDR P value | 0.002 | 0.288 | 0.033 | < 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.042 | ||

| Female | PostTyG | R | 0.089 | -0.074 | 0.023 | -0.047 | -0.156 | 0.029 |

| P value | 0.453 | 0.535 | 0.849 | 0.691 | 0.187 | 0.807 | ||

| FDR P value | 0.679 | 0.787 | 0.957 | 0.823 | 0.988 | 0.415 | ||

| PostTyG-BW | R | -0.158 | -0.212 | 0.117 | 0.726 | -0.124 | -0.018 | |

| P value | 0.183 | 0.071 | 0.323 | < 0.001 | 0.296 | 0.88 | ||

| FDR P value | 0.453 | 0.779 | 0.79 | 0.558 | 0.739 | 0.572 | ||

| PostTyG-BMI | R | -0.195 | -0.258 | 0.117 | 0.964 | -0.106 | -0.055 | |

| P value | 0.098 | 0.028 | 0.323 | < 0.001 | 0.373 | 0.641 | ||

| FDR P value | 0.458 | 0.447 | 0.558 | < 0.001 | 0.82 | 0.541 | ||

The Pearson correlation analysis showed that, in the total cohort, postTyG was significantly correlated with clinical stage (R = -0.133, P = 0.012), survival status (R = -0.125, P = 0.017), and survival time (r = 0.119, P = 0.023). Moreover, postTyG-BW was correlated with clinical stage (R = -0.218, P < 0.001), chemotherapy (r = 0.133, P = 0.012), BMI (r = 0.787, P < 0.001), survival status (R = -0.151, P = 0.004), and survival time (r = 0.200, P < 0.001). PostTyG-BMI was correlated with clinical stage (R = -0.221, P < 0.001), chemotherapy (r = 0.164, P = 0.002), BMI (r = 0.971, P < 0.001), survival status (R =

In men, postTyG was correlated with clinical stage (R = -0.190, P = 0.001) and survival time (r = 0.142, P = 0.016). PostTyG-BW was correlated with clinical stage (R = -0.245, P < 0.001), chemotherapy (r = 0.174, P = 0.003), BMI (r = 0.821, P < 0.001), survival status (R = -0.163, P = 0.006), and survival time (r = 0.257, P < 0.001). PostTyG-BMI was correlated with clinical stage (R = -0.222, P < 0.001), RT dose (r = 0.121, P = 0.040), chemotherapy (r = 0.182, P = 0.002), BMI (r = 0.969, P < 0.001), survival status (R = -0.152, P = 0.010), and survival time (r = 0.269, P < 0.001).

In women, no significant correlations were observed for postTyG. PostTyG-BW was correlated with BMI (r = 0.726, P < 0.001) and showed a near-significant correlation with RT dose (R = -0.212, P = 0.071). PostTyG-BMI was correlated with BMI (r = 0.964, P < 0.001) and RT dose (R = -0.258, P = 0.028) (Table 2).

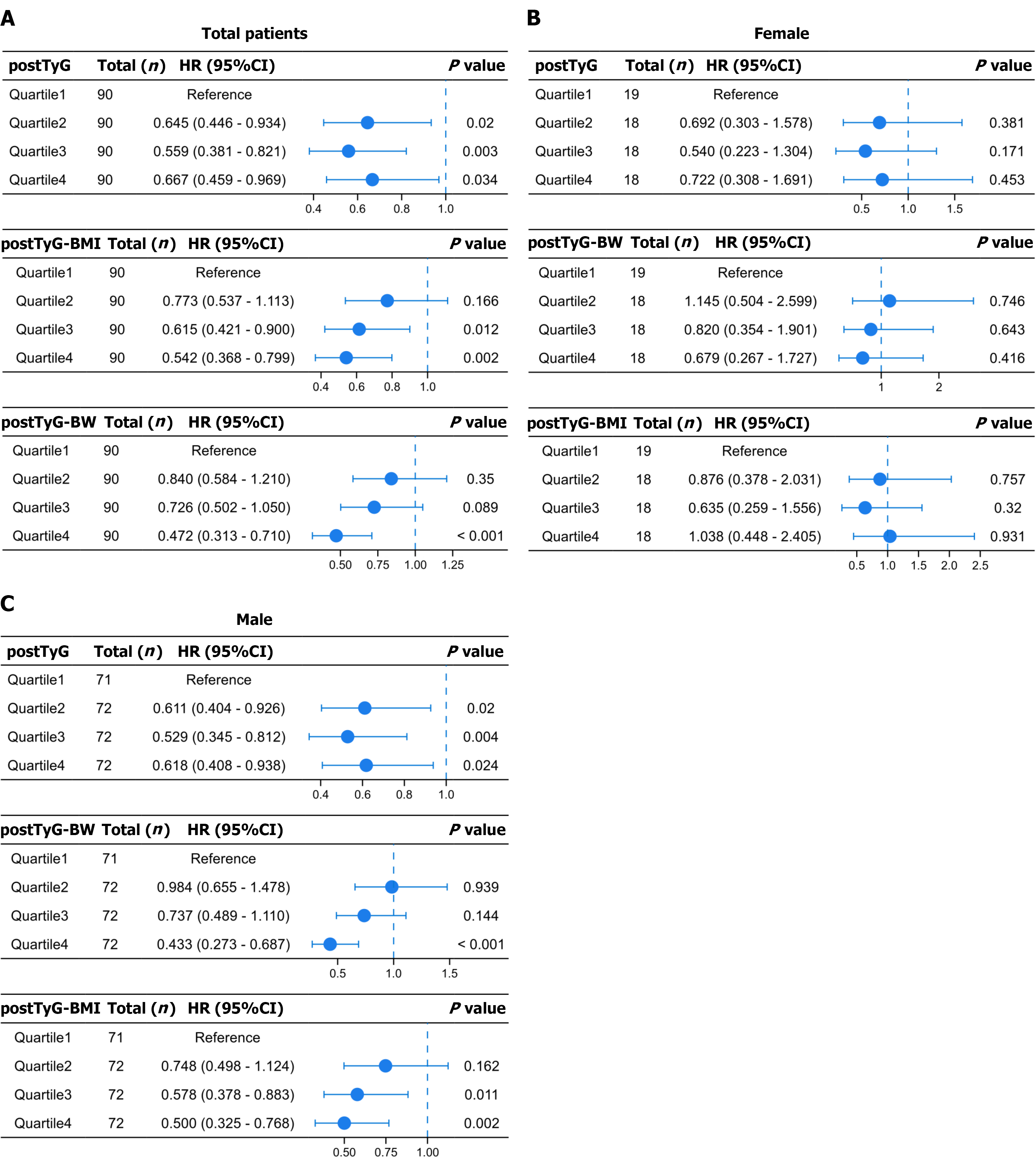

After adjusting for confounding factors, quartile-based analysis showed that, in the total cohort, postTyG Quartiles 2 [HR = 0.588, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.397-0.872, P = 0.008] and 3 (HR = 0.654, 95%CI: 0.451-0.949, P = 0.025) were associated with a significantly reduced mortality risk, as compared to the reference quartile. Moreover, Quartile 4 showed a near-significant trend (HR = 0.694, 95%CI: 0.476-1.010, P = 0.056). postTyG-BW Quartile 4 (HR = 0.471, 95%CI: 0.312-0.713, P < 0.001) was associated with a significantly reduced mortality risk. postTyG-BMI Quartiles 3 (HR = 0.619, 95%CI: 0.422-0.908, P = 0.014) and 4 (HR = 0.535, 95%CI: 0.361-0.794, P = 0.002) showed a significantly reduced mortality risk (Figure 5).

The prognostic relevance of MetS across cancer types remains highly contentious, stemming primarily from the stage-specific effects of metabolic indices, showing distinct impacts on carcinogenesis vs the clinical outcomes, and their modulation by tumor subtype and population characteristics[15,16]. The present study addresses this gap by investigating the prognostic value of IR surrogates, specifically the TyG index and its derivatives (TyG-BW and TyG-BMI), before and after treatment in ESCC patients. We demonstrate that elevated postTyG-related indices are correlated with a significantly reduced mortality risk in ESCC patients, with this association remaining robust after adjusting for confounding factors. Critically, postTyG outperforms baseline TyG (preTyG) in prognostic prediction, highlighting that dynamic metabolic changes post-treatment more accurately demonstrate the host’s metabolic adaptability and anti-tumor responses. This finding identifies a novel time window for clinical prognostic assessment.

Existing evidence supports the stage-specificity of MetS and its components in ESCC. Regarding carcinogenesis, Lee et al[17] have reported that MetS is correlated with an increased risk of ESCC-dominant EC in a Korean cohort (adjusted HR = 1.11), with increased waist circumference and hypertension as key risk factors. Conversely, a meta-analysis by Zhang et al[18] found no significant association between MetS and ESCC risk (I2 = 68.9%), although MetS was linked to an increased risk of developing EAC (pooled HR = 1.24). Such discrepancies likely stem from population heterogeneity; the high ESCC incidence in Korea is linked to fermented vegetable consumption and human papillomavirus infection, where MetS-driven inflammation may exacerbate this risk, whereas, in other regions, the MetS effects are overshadowed by confounding factors, including smoking and alcohol consumption.

Yang et al[14] have demonstrated that each 1-standard deviation increase in TyG index or METS-IR reduces the ESCC risk by 0.65-0.80-fold. Extending this, our data showed that elevated levels of postTyG derivatives are correlated with a reduced mortality risk, suggesting that the IR-related indices may exert protective effects throughout ESCC progression - mitigating both carcinogenesis and disease progression. Lindkvist et al[19] similarly reported that BMI is correlated with an increased EAC risk (relative risk = 7.34, 95%CI: 2.88-18.7) and a decreased ESCC risk (relative risk = 0.38, 95%CI: 0.23-0.62), aligning with our observation that post-treatment IR indices confer protection in ESCC patients. This is further supported by the negative correlation observed between postTyG and clinical stage (R = -0.133) and higher postTyG-BMI in patients with earlier-stage diseases.

Wen et al[20] have observed that ESCC patients with MetS exhibited superior survival and better tumor differentiation, suggesting that MetS may improve the outcomes by reducing tumor aggressiveness. Liu et al[21] have also identified diabetes as a protective factor in ESCC (HR = 0.668). Our findings extend these observations by highlighting the postTyG indices as superior prognostic markers; postTyG and postTyG-BMI were significantly higher in the survival group than in the deceased group (both P < 0.01), whereas preTyG showed no between-group differences. This “dynamic discrepancy” may arise from two mechanisms. The first mechanism is metabolic remodeling by treatment. ESCC chemoradiotherapy may upregulate TyG by enhancing insulin sensitivity, with elevated postTyG levels reflecting restored metabolic reserve and improved capacity to counteract cancer-related cachexia. This complements Liu et al’s finding[21] that weight loss increases the mortality risk (HR = 1.961), underscoring metabolic reserve as a critical prognostic determinant. The second mechanism is the stage-specific metabolic profile. PreTyG primarily reflects “inadequate intake + passive catabolism” during uncontrolled tumor growth, lacking protective effects; contrarily, the elevation of postTyG levels represents adaptive metabolic adjustments to support tissue repair and anti-tumor responses, explaining its prognostic utility.

Peng et al[22] have reported sex-specific effects of MetS on the mortality risk of ESCC patients, with significant associations found only in men (HR = 1.45); hyperglycemia and dyslipidemia emerged as the risk factors in men, whereas obesity predicted the poor outcomes in women. Our data confirmed the analogous sex specificity for postTyG and its derivatives, with inverse correlations with mortality restricted to men. This divergence may reflect the following: (1) Sex-based metabolic differences: The IR in male ESCC patients is more accurately quantifiable by measuring TyG (preTyG was significantly higher in men aged < 65 years with low BMI; P = 0.002), and post-treatment IR improvement may more potently enhance the immune function in men; and (2) Confounding in women: PostTyG-BMI in women is strongly correlated only with BMI (r = 0.964) and RT dose, suggesting that the outcomes women with ESCC are more dependent on radiation intensity, whereas those of their male counterparts are regulated by metabolic status.

Okamura et al[23] have shown that a high visceral-to-subcutaneous fat ratio predicts increased lymphovascular invasion, nodal metastasis, and poor response to neoadjuvant therapy among ESCC patients. Contrarily, our study found that postTyG is positively correlated with chemotherapy administration (r = 0.164, P = 0.002), with postTyG Quartiles 2-3 showing an association with a reduced mortality risk, suggesting that postTyG could monitor the treatment response. Clinically, dynamic postTyG monitoring may guide chemotherapy adjustments (e.g., enhanced nutritional support for patients with low postTyG levels). Additionally, the strong correlation between postTyG-BMI and BMI (r = 0.971) indicates that combining the metabolic and anthropometric indices (e.g., TyG-BMI) more accurately reflects the systemic status, outperforming single markers. This positions postTyG-BMI as a novel tool for ESCC risk stratification - particularly in men, where it acts as an independent prognostic factor.

In recent years, the integration of large-scale cohorts with radiomics/artificial intelligence (AI) models has further advanced the development of metabolic oncology and precision oncology. Among these advances, Wu et al[24] enrolled 589 postoperative patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, including internal and external validation cohorts. They combined CT radiomics with metabolic indicators (e.g., visceral fat index) to predict early recurrence. Second, a large cohort study focusing on breast cancer patients used radiomics to link metabolic disorders to prognosis[25,26]. Additionally, radiomics and AI have advanced rapidly in predicting tumor prognosis and evaluating treatment responses, providing new tools for clinical assessment. For instance, Cao et al[27] constructed a magnetic resonance imaging-based radiomics model for non-small cell lung cancer, which can accurately predict molecular changes and treatment responses. Fan et al[28] developed a CT-based delta-radiomics model for EC to effectively evaluate treatment responses. Wen et al[29] applied AI to immunotherapy, confirming its value in predicting therapeutic efficacy and toxicity. In comparison, the TyG index and its derived indicators - the focus of this study - exhibit superior clinical accessibility. The TyG index is calculated using conventional biochemical markers. It requires no specialized equipment, can be obtained via standard blood tests, and offers advantages including low cost, ease of operation, and the ability for dynamic monitoring.

However, this study has several limitations. First, this study adopts a single-center retrospective design. Inherent selection bias in this design cannot be completely avoided. In the future, verifying the reliability of the conclusions will require a multi-center prospective cohort. Second, female patients accounted for approximately 20% of the study population. This proportion aligns with the epidemiological characteristics of EC. However, it reduces the reliability of sex-stratified conclusions to some extent. Thus, the sex-stratified conclusions remain referenceable. Future plans include collaborating with centers with a high incidence of female EC to expand the sample size for further verification. Finally, several metabolic indicators (e.g., homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance, hypertension) were not included in this study. This omission hinders the comprehensive evaluation of IR’s impact on EC. Additionally, the mechanism underlying dynamic changes in metabolic indicators was not explored in depth. Meanwhile, the study was based on data from East Asian patients and lacked external validation. Further evidence should be obtained from multi-center, large-sample, and multi-population studies.

The postTyG, postTyG-BW, and postTyG-BMI may serve as prognostic indicators for ESCC, with elevated levels associated with a reduced risk of death; these IR surrogate markers may also hold potential as therapeutic response markers, providing a foundation for their integration into the personalized management of ESCC, and future studies will explore the mechanisms linking IR improvement to ESCC prognosis, including by manipulating insulin sensitivity at the ESCC cell level, simulating changes in TyG levels and metabolomic profiles in chemoradiotherapy animal models, and integrating these experimental approaches with dynamically measured TyG indices and immune markers in clinical settings.

We appreciate everyone who participated in the study.

| 1. | Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74:229-263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5690] [Cited by in RCA: 13018] [Article Influence: 6509.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (8)] |

| 2. | Morgan E, Soerjomataram I, Rumgay H, Coleman HG, Thrift AP, Vignat J, Laversanne M, Ferlay J, Arnold M. The Global Landscape of Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma and Esophageal Adenocarcinoma Incidence and Mortality in 2020 and Projections to 2040: New Estimates From GLOBOCAN 2020. Gastroenterology. 2022;163:649-658.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 796] [Cited by in RCA: 760] [Article Influence: 190.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Sheikh M, Roshandel G, McCormack V, Malekzadeh R. Current Status and Future Prospects for Esophageal Cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15:765. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 167] [Article Influence: 55.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Liu CQ, Ma YL, Qin Q, Wang PH, Luo Y, Xu PF, Cui Y. Epidemiology of esophageal cancer in 2020 and projections to 2030 and 2040. Thorac Cancer. 2023;14:3-11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 232] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Thrift AP. Global burden and epidemiology of Barrett oesophagus and oesophageal cancer. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;18:432-443. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 231] [Article Influence: 46.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Shanahan C. The energy model of insulin resistance: A unifying theory linking seed oils to metabolic disease and cancer. Front Nutr. 2025;12:1532961. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Caturano A, Erul E, Nilo R, Nilo D, Russo V, Rinaldi L, Acierno C, Gemelli M, Ricotta R, Sasso FC, Giordano A, Conte C, Ürün Y. Insulin resistance and cancer: molecular links and clinical perspectives. Mol Cell Biochem. 2025;480:3995-4014. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Szablewski L. Insulin Resistance: The Increased Risk of Cancers. Curr Oncol. 2024;31:998-1027. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 34.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Neeland IJ, Lim S, Tchernof A, Gastaldelli A, Rangaswami J, Ndumele CE, Powell-Wiley TM, Després JP. Metabolic syndrome. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2024;10:77. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 183] [Article Influence: 91.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Cai S, Xing H, Wang Y, Yang W, Luo H, Ye X. The association between triglyceride glucose-body mass index and overall survival in postoperative patient with lung cancer. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2025;16:1528644. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Zhang J, Yin B, Xi Y, Bai Y. Triglyceride-glucose index is a risk factor for breast cancer in China: a cross-sectional study. Lipids Health Dis. 2024;23:29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Zhou Y, Li T, Muheiyati G, Duan Y, Xiao S, Gao Y, Tao N, An H. Triglyceride-glucose index is a predictor of the risk of prostate cancer: a retrospective study based on a transprostatic aspiration biopsy population. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023;14:1280221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | He G, Zhang Z, Wang C, Wang W, Bai X, He L, Chen S, Li G, Yang Y, Zhang X, Cui J, Xu W, Song L, Yang H, He W, Zhang Y, Li X, Chen L. Association of the triglyceride-glucose index with all-cause and cause-specific mortality: a population-based cohort study of 3.5 million adults in China. Lancet Reg Health West Pac. 2024;49:101135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Yang C, Cheng W, Plum PS, Köppe J, Gockel I, Thieme R. Association between four insulin resistance surrogates and the risk of esophageal cancer: a prospective cohort study using the UK Biobank. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2024;150:399. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Yeh HY, Pan MH, Huang CJ, Hong SY, Yang HI, Yang YY, Huang CC, Tsai HC, Li TH, Su CW, Hou MC. Triglyceride-glucose index and cancer risk: a prospective cohort study in Taiwan. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2025;17:283. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Zou Y, Ye H, Xu Z, Yang Q, Zhu J, Li T, Cheng Y, Zhu Y, Zhang J, Bo Y, Wang P. Obesity, Sarcopenia, Sarcopenic Obesity, and Hypertension: Mediating Role of Inflammation and Insulin Resistance. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2025;80:glae284. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Lee JE, Han K, Yoo J, Yeo Y, Cho IY, Cho B, Park JH, Shin DW, Cho JH, Park YM. Association Between Metabolic Syndrome and Risk of Esophageal Cancer: a Nationwide Population-Based Study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2022;31:2228-2236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Zhang SH, Wang Y, Wang H, Zhong M, Qi X, Xie SH. Metabolic syndrome and risk of esophageal cancer by histological type: Systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Cancer Epidemiol. 2025;97:102849. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Lindkvist B, Johansen D, Stocks T, Concin H, Bjørge T, Almquist M, Häggström C, Engeland A, Hallmans G, Nagel G, Jonsson H, Selmer R, Ulmer H, Tretli S, Stattin P, Manjer J. Metabolic risk factors for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma: a prospective study of 580,000 subjects within the Me-Can project. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Wen YS, Huang C, Zhang X, Qin R, Lin P, Rong T, Zhang LJ. Impact of metabolic syndrome on the survival of Chinese patients with resectable esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Dis Esophagus. 2016;29:607-613. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Liu B, Cheng B, Wang C, Chen P, Cheng Y. The prognostic significance of metabolic syndrome and weight loss in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Sci Rep. 2018;8:10101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Peng F, Hu D, Lin X, Chen G, Liang B, Zhang H, Dong X, Lin J, Zheng X, Niu W. Analysis of Preoperative Metabolic Risk Factors Affecting the Prognosis of Patients with Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma: The Fujian Prospective Investigation of Cancer (FIESTA) Study. EBioMedicine. 2017;16:115-123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Okamura A, Watanabe M, Yamashita K, Yuda M, Hayami M, Imamura Y, Mine S. Implication of visceral obesity in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2018;403:245-253. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Wu L, Cen C, Ouyang D, Zhang L, Li X, Wu H, He M, Han P, Tan W, Chen L, Zheng C. Interpretable Machine Learning Model for Predicting Early Recurrence of Pancreatic Cancer: Integrating Intratumoral and Peritumoral Radiomics With Body Composition. Int J Surg. 2025;111:8198-8211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | You C, Su GH, Zhang X, Xiao Y, Zheng RC, Sun SY, Zhou JY, Lin LY, Wang ZZ, Wang H, Chen Y, Peng WJ, Jiang YZ, Shao ZM, Gu YJ. Multicenter radio-multiomic analysis for predicting breast cancer outcome and unravelling imaging-biological connection. NPJ Precis Oncol. 2024;8:193. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Su GH, Xiao Y, You C, Zheng RC, Zhao S, Sun SY, Zhou JY, Lin LY, Wang H, Shao ZM, Gu YJ, Jiang YZ. Radiogenomic-based multiomic analysis reveals imaging intratumor heterogeneity phenotypes and therapeutic targets. Sci Adv. 2023;9:eadf0837. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Cao P, Jia X, Wang X, Fan L, Chen Z, Zhao Y, Zhu J, Wen Q. Deep learning radiomics for the prediction of epidermal growth factor receptor mutation status based on MRI in brain metastasis from lung adenocarcinoma patients. BMC Cancer. 2025;25:443. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Fan L, Yang Z, Chang M, Chen Z, Wen Q. CT-based delta-radiomics nomogram to predict pathological complete response after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma patients. J Transl Med. 2024;22:579. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Wen Q, Qiu L, Qiu C, Che K, Zeng R, Wang X, Cao P, Xing L, Yang Z, Yu J. Artificial intelligence in predicting efficacy and toxicity of Immunotherapy: Applications, challenges, and future directions. Cancer Lett. 2025;630:217881. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/