Published online Dec 24, 2025. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v16.i12.112871

Revised: September 14, 2025

Accepted: November 13, 2025

Published online: December 24, 2025

Processing time: 137 Days and 15.4 Hours

The technical complexity and potential for complications associated with en

To examine the results of ESD and hybrid ESD, a simpler adaptation of the ESD technique, for stage 1 rectal NETs.

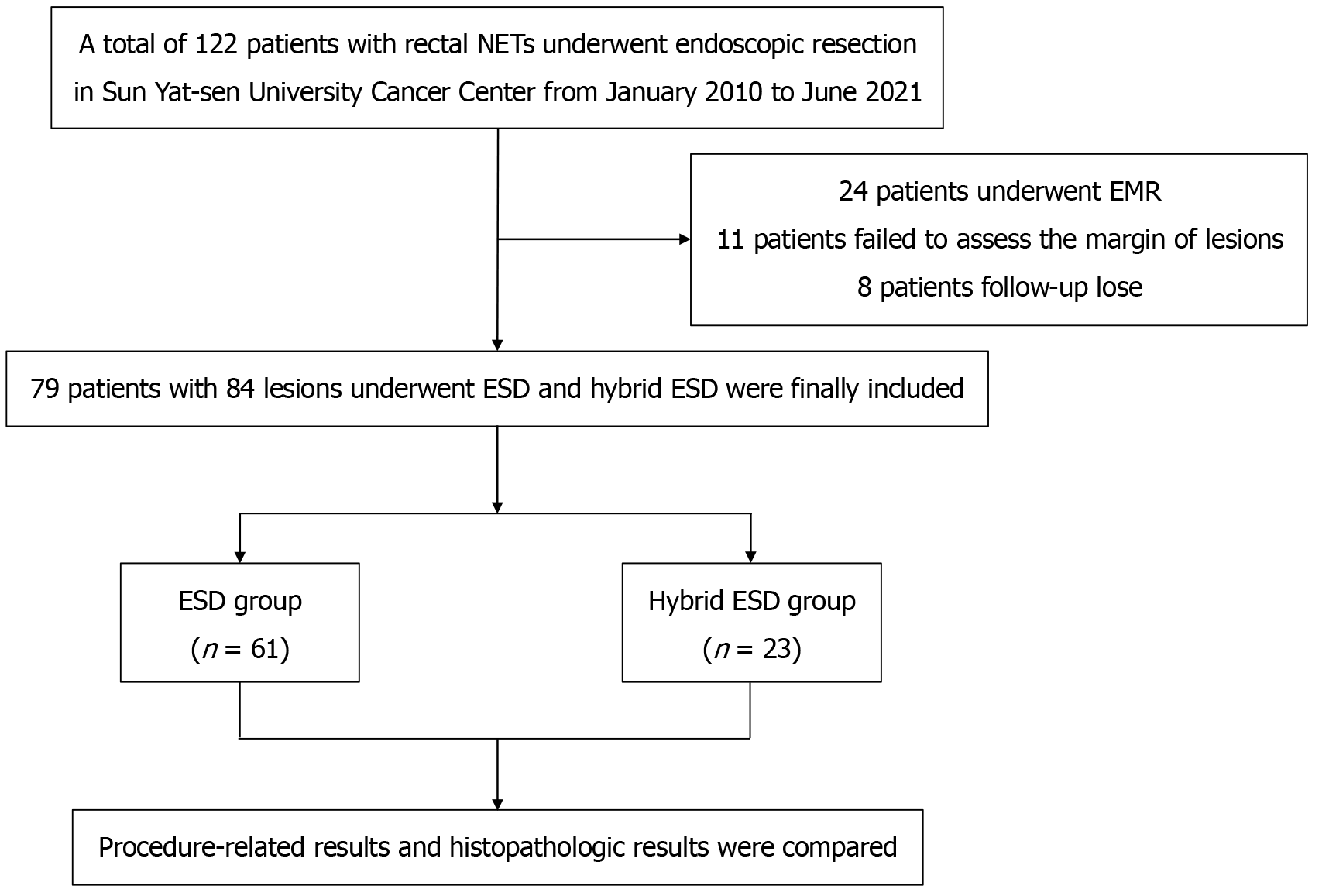

Seventy-nine patients with 84 lesions of clinical stage 1 rectal NETs who received treatment at Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center from January 2010 to June 2021 were reviewed retrospectively.

Sixty-one lesions in 58 patients were treated with ESD, while 23 in 21 patients were treated with hybrid ESD. The 84 rectal NETs had a median diameter of 8 (5) mm (range, 3-20 mm), with the median lesion size 8 (5) mm for ESD and 8 (4) mm for hybrid ESD (P = 0.359). For ESD, the median duration of procedure was 46.00 (14.00) minutes, while for hybrid ESD, it was 32.00 (15.00) minutes (P < 0.001). Both the ESD and hybrid ESD groups had identical rates of en bloc resection (100.00% vs 100.00%, P = 1.000), R0 resection (86.89% vs 86.96%, P = 1.000), perforation (1.64% vs 0.00%, P = 1.000), and delayed bleeding (1.64% vs 4.35%, P = 0.475). After a median of 27.50 (30.00) months of observation, neither group had recurrence.

For endoscopic excision of stage 1 rectal NETs, both ESD and hybrid ESD were well tolerated and produced posi

Core Tip: Despite a high complete resection (R0) rate, its technical difficulty and risk of complications limit the widespread use of endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) for stage 1 rectal neuroendocrine tumors (NETs). One simplified modification to ESD is hybrid ESD (ESD with snaring). This research analyzed 84 lesions who were diagnosed with rectal NETs and treated with ESD or hybrid ESD. We found that both ESD and hybrid ESD were safe and effective for endoscopic resection of stage 1 rectal NETs, and hybrid ESD can be a good alternative to ESD for R0 resection of stage 1 rectal NETs.

- Citation: Qiao XY, Shen XJ, Lv YH, Chen RB, Weng J, Xu GL, Wen G, Bai KH. Endoscopic submucosal dissection and hybrid endoscopic submucosal dissection for stage 1 rectal neuroendocrine tumors. World J Clin Oncol 2025; 16(12): 112871

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-4333/full/v16/i12/112871.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5306/wjco.v16.i12.112871

Rectal neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) are uncommon but potentially malignant tumors. The detection rate with colonoscopy is around 0.05%-0.17%, although the worldwide incidence of rectal NETs has increased several to a dozen times as a result of the significant rise in colonoscopy popularity over the last several decades[1-3]. Clinicians are becoming more and more concerned about the variable prognosis of rectal NETs due to factors such as tumor size, grade, depth of invasion and lymphatic vascular. It has been noticed that between 80% and 90% of rectal NETs are quite small when first discovered during a routine colonoscopy[4,5].

Low-risk lymph node metastases and local endoscopic excision are now accepted for rectal NETs less than 20 mm in diameter that are limited to the mucosa and submucosa[4,6,7]. To achieve a more histologically complete excision of the lesion and a lower incidence of remaining tissue, endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) is also recommended for the endoscopic treatment of rectal NETs[6,8-10]. However, ESD has not been commonly utilized for the removal of rectal NETs, presumably because it is technically more difficult, takes longer, and has a greater risk of major consequences including perforation when compared to other techniques. Hybrid ESD (ESD with snaring) is a straightforward variant on the original method[11]. While the first part of the hybrid ESD process is performed similarly to conventional ESD, the last step includes the use of a snare to capture and remove the undissected, constricted submucosal tissue.

This research analyzed patients with stage 1 rectal NETs who were treated with ESD or hybrid ESD. En bloc and R0 resection rates, surgery time, complications, histopathological findings and follow-up data were all evaluated.

A single-center retrospective cohort study was conducted on a cohort of 79 patients with 84 lesions of clinical stage 1 (cT1N0M0)[7] rectal NETs who received treatment at Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center from January 2010 to June 2021 (Figure 1). Prior to the surgery, invasion depth, as well as to assess the presence of local lymph node involvement or distant metastases were ruled out by magnetic resonance imaging, abdominopelvic computed tomography or endoscopic ultrasonography in all patients. The excision of the lesions was performed by ESD or hybrid ESD, followed by histological examination. The criteria for inclusion in the study were: (1) The lesion was situated in the rectum, specifically at a distance of less than 15 cm from the anus; (2) The lesion exhibited a lengthy diameter of less than 20 mm; (3) Prior to the endoscopic resection, examinations using endoscopic ultrasonography/magnetic resonance imaging/computed tomography did not reveal any evidence of invasion into the muscularis propria, involvement of local lymph nodes, or presence of distant metastases; and (4) the diagnosis was confirmed by histopathology. The exclusion criteria included: (1) Patients combined with other types of malignant tumors; and (2) participants with a follow-up period of less than 6 months.

Prior to undergoing endoscopic resection, all patients were duly informed about the possible risks and advantages associated with the procedure. In addition, they provided written informed permission as a prerequisite for their participation. The techniques conducted in this study adhere to the guidelines outlined in the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and subsequent ethics that are pertinent to the research. The retrospective research was approval by the Ethics Committee of the Institutional Review Board of the Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center, approval No. SL-B2023-722-01 and informed consent was exempt.

The study used a single-channel endoscope (manufactured by Olympus Co, Tokyo, Japan) for ESD. A transparent hood was affixed to the distal end of the endoscope. Following a thorough examination of the lesion, a submucosal injection was administered in the vicinity of the lesion in order to elevate it from the muscular layer. The solution used in this study consisted of sodium hyaluronate that was diluted with a normal saline solution at a ratio of 1:4. Additionally, a tiny quantity of indigo carmine was introduced into the solution. Following the administration of the injection, an incision was made in the mucosa around the elevated lesion using a stationary and adaptable snare knife. A surgical procedure was performed in which the mucosa was carefully cut, ensuring a distance of about 2 mm to 3 mm from the outside edge of the lesion. This was done to ensure that the lateral resection margin was free from any tumor tissue. Following a mucosal incision that encompassed around 50% of the lesion's diameter, the submucosal tissue underlying the lesion was separated from the muscular layer using the same surgical instrument. Following the procedure of submucosal dissection, the remaining portion of the lesion that was not initially raised was subsequently elevated with an additional submucosal injection. Subsequently, the mucosal incision was fully executed. The lesion was fully removed from the muscle layer with further submucosal dissection. Following the resection procedure, the visible blood vessels inside the ulcer that occurred during ESD were effectively eliminated with the use of either hemostatic forceps or argon plasma coagulation. The electrosurgical machines utilized in this study were manufactured by Elektromedizin GmbH, Tuebingen, Germany.

The hybrid ESD procedure entails the first execution of ESD, followed by the use of snaring as the final resection technique. The ESD procedure was conducted in a manner consistent with previous descriptions, with the exception that submucosal dissection was deferred until the lesion had been fully detached from the muscular layer. Instead, the submucosal dissection was advanced in a circumferential manner only up to the point where the remaining undissected submucosal tissue accounted for less than 1/4 of the lesion’s width. Then, the enclosed, restricted submucosal tissue was then captured and excised by the use of an electrical current with snaring.

The selection between ESD or hybrid ESD was determined by the judgment of the endoscopist. The primary indications for hybrid ESD were twofold. Firstly, it was used for faster resection in cases which snaring the remaining undissected submucosal portion appeared to be a straightforward task. Secondly, hybrid ESD was employed to complete the resection in cases where the location of the lesion or the presence of submucosal fibrosis made complete submucosal dissection challenging. In such instances, performing ESD alone could have potentially increased the risk of perforation.

An ESD specialist refers to an endoscopist who has autonomously conducted over 100 instances of colorectal ESD. An ESD beginner refers to an endoscopist who has autonomously conducted fewer than 100 instances of colorectal ESD.

Histological examination was conducted on the resected tumors to assess parameters such as lymphovascular invasion, the depth of invasion, and the status of the resected margin of the specimen, determining whether it was positive or negative. The assessment of mitotic rate and Ki-67 index was conducted in accordance with the guidelines provided by the World Health Organization[6,7].

En bloc resection was originally described as a surgical procedure involving the removal of a tumor or lesion in a single, intact piece. A R0 resection is operationally defined as a surgical procedure in which both the lateral margin and vertical margin are found to be negative upon microscopic inspection. Curative resection refers to a surgical procedure known as R0 resection, which involves the complete removal of a tumor without any evidence of vascular invasion or perineurium invasion. Non-curative resection was operationally defined as a surgical procedure with evidence of positive vertical margins, positive lateral margins, vascular invasion, or perineurium invasion upon microscopic inspection of the resected tumors.

The procedure time was operationally defined as the duration from the initiation of submucosal injection and the full completion of lesion excision. The size of the lesion was assessed endoscopically, with open biopsy forceps serving as a reference. Delayed bleeding is characterized by the presence of hematochezia and/or melena after the conclusion of endoscopic resection, necessitating another endoscopy for the purpose of achieving hemostasis. The identification of perforation was determined by the examination of endoscopic and/or radiographic evidence. The American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) lexicon classification was used for assessment of the severity of complications.

For patients with non-curative resection of stage 1 rectal NETs with G2/G3, a salvage radical surgical procedure was recommended, while for patients with non-curative resected stage 1 rectal NETs with G1, salvage local resection (endoscopic resection or transanal endoscopic microsurgery) or close follow-up was recommended[10].

The clinical results were determined by retrospective examination of the medical data. The first clinical follow-up was conducted within 1 weeks to 2 weeks subsequent to the endoscopic resection procedure. The assessment was conducted to determine the incidence of problems, such as delayed bleeding. It was suggested that individuals who have had curative resection get a colonoscopy examination every six months during the first year after the surgical procedure. In the absence of any indications of recurrence, it was advised to do an annual colonoscopy check. Colonoscopy was advised at intervals of 3 months, 6 months, and 12 months after the procedure for patients who had undergone R0 resection but exhibited vascular invasion, or for patients who had undergone non-R0 resection and declined further surgical intervention. Subsequently, an annual colonoscopy was indicated in the absence of any local recurrence. In the event that a potential recurrence was seen during a follow-up colonoscopy, it was advised to proceed with a biopsy.

Typically, continuous variables that follow a normal distribution were represented using means and standard deviations. On the other hand, for continuous variables that did not follow a normal distribution, medians and interquartile ranges were employed. Categorical variables were often represented as proportions. The variables were compared via statistical tests such as t-tests, Kruskal-Wallis tests, χ2 tests, or Fisher's exact tests, depending on the nature of the data. The missing data was removed.

A binary logistic regression analysis was conducted to determine the risk variables associated with non-R0 resection. The odds ratio (OR) for each item was computed along with a 95% confidence interval (CI). The significance level was set at P < 0.05 for a two-tailed test. Statistical testing was conducted using SAS v9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., United States).

The summary of the baseline characteristics analyses may be seen in Table 1. The investigation included a collective of 84 lesions among 79 patients. A total of 61 lesions in 58 patients had ESD, whereas 23 lesions in 21 patients had hybrid ESD. There were 33 (56.89%) men in the ESD group and 12 (57.14%) men in the hybrid ESD group (P = 0.984). The mean ages were 45.38 ± 13.15 years and 42.61 ± 14.38 years (P = 0.424) and the median lesion size was 8 (5) mm and 8 (4) mm in the respective groups (P = 0.359).

| Characteristic | ESD (n = 61) | Hybrid ESD (n = 23) | t/χ2 value | P value |

| Lesion size, mm | 8 (5) | 8 (4) | 0.842 | 0.359 |

| Age (year), mean ± SD | 45.38 ± 13.15 | 42.61 ± 14.38 | 0.800 | 0.424 |

| Procedure time, minute | 46.00 (14.00) | 32.00 (15.00) | 25.093 | < 0.001 |

| Follow-up time, month | 24.00 (23.00) | 34.00 (32.00) | 5.010 | 0.024 |

| Male | 33 (56.89) | 12 (57.14) | 0.000 | 0.984 |

| Location | ||||

| Anus ≤ 5 cm | 24 (39.34) | 8 (34.78) | 0.147 | 0.701 |

| Anus > 5 cm | 37 (60.66) | 15 (65.21) | ||

| Operator | ||||

| Specialist | 53 (86.89) | 17 (73.91) | 2.024 | 0.192 |

| Beginner | 8 (13.11) | 6 (26.09) | ||

| Perforation | 1 (1.64) | 0 (0.00) | 0.382 | 1.000 |

| Delayed hemorrhage | 1 (1.64) | 1 (4.35) | 0.527 | 0.475 |

| Histologic grade | ||||

| G1 | 55 (90.16) | 20 (86.96) | 0.672 | 0.700 |

| G2 | 6 (9.84) | 3 (13.04) | ||

| Invasion depth | ||||

| Mucosa | 5 (8.20) | 1 (4.35) | 0.541 | 1.000 |

| Submucosa | 56 (91.80) | 22 (95.65) | ||

| En-bloc resection | 61 (100.00) | 23 (100.00) | ||

| R0 resection | 53 (86.89) | 20 (86.96) | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Vascular invasion | 0 (0.00) | 1 (4.35) | 2.684 | 0.274 |

| Recurrence | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | ||

The average duration of the procedure was substantially higher for ESD compared to hybrid ESD, with median times of 46.00 (14.00) minutes and 32.00 (15.00) minutes, respectively (P < 0.001) (Table 1). The en bloc resection rate achieved a 100.00% success rate for both procedures.

There was one case of perforation, which was classified as moderate adverse event according to the ASGE lexicon, resulting in prolongation of the hospital stay by 4 days. The perforated case was effectively treated using the OTSC technique, obviating the need for further surgical intervention. Two cases of delayed bleeding occurred, both of which were classified as moderate adverse events according to the ASGE lexicon and were treated with repeat endoscopy (endoscopic hemostasis was used for the medical management of the two cases of delayed bleeding). The incidence of perforation (1.64% vs 0.00%, P = 1.000) and delayed bleeding (1.64% vs 4.35%, P = 0.475) exhibited no significant differences between the two groups.

A total of 11 subjects had positive vertical margins, leading to a R0 resection rate of 86.90% (73/84) (Table 1). Only a single instance was completely resected (R0), although vascular involvement was evident. Hence, the rate of curative resection was 85.71% (72/84). In the ESD group, the rate of R0 resection was 86.89% (53/61 cases), whereas in the hybrid ESD group, the rate of R0 resection was 86.96% (20/23 cases) (P = 1.000). Based on the categorization of mitoses and the Ki-67 proliferation index, it was determined that 89.29% (75/84) of cases fell into the G1 category, whereas 10.71% (9/84) of cases were categorized as G2. In 7.14% (6/84) of the cases, the lesions were limited to the mucosal layer, whereas in 92.96% (78/84) of the cases, the lesions had penetrated into the submucosal layer.

The results of outcome analyses based on lesion size are shown in Table 2. The research included a collective of 56 lesions measuring less than 10 mm and 28 lesions measuring between 10-20 mm. In both lesions measuring less than 10 mm and lesions measuring 10-20 mm, hybrid ESD demonstrated comparable outcomes to ESD in terms of having no significant difference for en bloc resection rate, R0 resection rate and complication rate. Nevertheless, hybrid ESD exhibited was more efficient compared to ESD, in terms of having shorter procedure time.

| Characteristic | 1A (< 10 mm, n = 56) | 1B (10-20 mm, n = 28) | ||||||

| ESD (n = 41) | Hybrid ESD | t/χ2 value | P value | ESD (n = 20) | Hybrid ESD | t/χ2 value | P value | |

| Procedure time, minute | 44.00 (16.00) | 30.00 (13.00) | 14.905 | < 0.001 | 50.50 (10.00) | 33.00 (20.00) | 11.471 | < 0.001 |

| Follow-up time, month | 22.00 (24.00) | 30.00 (27.00) | 1.426 | 0.232 | 26.50 (31.50) | 48.00 (22.00) | 4.905 | 0.027 |

| Perforation | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | / | / | 1 (5.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0.415 | 1.000 |

| Delayed hemorrhage | 1 (2.43) | 0 (0.00) | 0.373 | 1.000 | 0 (0.00) | 1 (12.50) | 2.593 | 0.286 |

| En bloc resection | 41 (100.00) | 15 (100.00) | / | / | 20 (100.00) | 8 (100.00) | / | / |

| R0 resection | 37 (90.24) | 13 (86.67) | 0.147 | 0.654 | 16 (80.00) | 7 (87.50) | 0.219 | 1.000 |

| Recurrence | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | / | / | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | / | / |

The subsequent data is succinctly described in Table 3. Out of the 12 cases of non-curative resection, three cases with positive vertical margins underwent salvage surgery, resulting in the absence of residual tumor cells upon microscopic examination. Additionally, five cases with positive vertical margins underwent mucosal biopsy in the postoperative scar, revealing no residual tumor cells upon microscopic examination. Furthermore, three cases with positive vertical margins and one case with vascular invasion underwent colonoscopy follow-up without mucosal biopsy. The median duration of follow-up for the 12 patients was 25.00 (18.00) months, during which no instances of tumor recurrence were observed.

| Number | Gender | Age | Size (mm) | Method | Grade | Invasion depth | Salvage therapy | Microscopic examination | Follow-up (month) | Recurrence |

| 1 | Male | 41 | 10 | ESD | G1 | Submucosa | Colonoscopy | / | 76 | No |

| 2 | Female1 | 20 | 5 | hybrid ESD | G1 | Submucosa | Colonoscopy | / | 30 | No |

| 3 | Male | 34 | 10 | ESD | G1 | Submucosa | Salvage local resection | Negative | 24 | No |

| 4 | Female | 46 | 8 | ESD | G1 | Submucosa | Salvage radical surgery | Negative | 16 | No |

| 5 | Female | 32 | 6 | hybrid ESD | G1 | Submucosa | Colonoscopy | / | 12 | No |

| 6 | Male | 27 | 10 | ESD | G1 | Submucosa | Salvage local resection | Negative | 34 | No |

| 7 | Female | 51 | 15 | hybrid ESD | G1 | Submucosa | Colonoscopy + biopsy | Negative | 38 | No |

| 8 | Female | 31 | 8 | hybrid ESD | G1 | Submucosa | Colonoscopy + biopsy | Negative | 25 | No |

| 9 | Male | 53 | 5 | ESD | G1 | Submucosa | Colonoscopy | / | 20 | No |

| 10 | Male | 35 | 4 | ESD | G1 | Submucosa | Colonoscopy + biopsy | Negative | 29 | No |

| 11 | Male | 36 | 10 | ESD | G1 | Submucosa | Colonoscopy + biopsy | Negative | 15 | No |

| 12 | Male | 55 | 5 | ESD | G1 | Submucosa | Colonoscopy + biopsy | Negative | 10 | No |

The factors associated with non-R0 resection for stage 1 rectal NETs are shown in Table 4. The proportion of beginners was significantly higher in the non-R0 resection group compared to in the R0 resection group (45.45% vs 12.33%, P = 0.016). There were no significant differences between the two groups in terms of age, lesion size, sex, tumor location, resection method, pathological grade and invasion depth.

| Characteristic | Non-R0 resection (n = 11) | R0 resection (n = 73) | t/χ2 value | P value |

| Age (year), mean ± SD | 40.09 ± 9.71 | 45.38 ± 13.88 | 1.210 | 0.229 |

| Lesion size, mm | 8.00 (5.00) | 8.00 (4.00) | 0.186 | 0.666 |

| Procedure time, minute | 49.00 (18.00) | 42.00 (16.00) | 0.721 | 0.399 |

| Male | 7 (63.63) | 38 (55.88) | 0.232 | 0.749 |

| Location | ||||

| Anus ≤ 5 cm | 4 (36.36) | 28 (38.36) | 0.016 | 1.000 |

| Anus > 5 cm | 7 (63.63) | 45 (61.64) | ||

| Operator | ||||

| Specialist | 6 (54.55) | 64 (87.67) | 7.553 | 0.016 |

| Beginner | 5 (45.45) | 9 (12.33) | ||

| Resection method | ||||

| ESD | 8 (72.73) | 53 (72.60) | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Hybrid ESD | 3 (27.27) | 20 (27.29) | ||

| Grade | ||||

| G1 | 11 (100.00) | 64 (87.67) | 1.519 | 0.598 |

| G2 | 0 (0.00) | 9 (12.33) | ||

| Invasion depth | ||||

| Mucosal | 0 (0.00) | 6 (8.22) | 0.974 | 1.000 |

| Submucosal | 11 (100.00) | 67 (91.78) | ||

Multivariate analysis was conducted to evaluate the variables that influence non-R0 resection (Table 5). In comparison to individuals with expertise in ESD, those classified as ESD beginners exhibited ORs of 7.31 (95%CI: 1.70-31.42, P = 0.008) for non-R0 resection. The non-R0 resection was not influenced by other variables such as age, sex, lesion size, location, and resection method, since they were not shown to be independent factors.

| Characteristic | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

| OR (95%CI) | P value | OR (95%CI) | P value | |

| Age (year), mean ± SD | 0.97 (0.92-1.02) | 0.229 | 0.97 (0.92-1.03) | 0.284 |

| Lesion size, mm | 1.03 (0.85-1.25) | 0.730 | 1.01 (0.81-1.26) | 0.913 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Female | 0.72 (0.19-2.70) | 0.631 | 0.74 (0.17-3.23) | 0.688 |

| Location | ||||

| Anus ≤ 5 cm | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Annus > 5 cm | 1.09 (0.29-4.06) | 0.899 | 1.18 (0.28-5.05) | 0.824 |

| Operator | ||||

| Specialist | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Beginner | 5.93 (1.50-23.48) | 0.011 | 7.31 (1.70-31.42) | 0.008 |

| Resection method | ||||

| ESD | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Hybrid ESD | 0.99 (0.24-4.12) | 0.993 | 0.81 (0.16-3.97) | 0.792 |

The current research proved that both ESD and hybrid ESD are viable and successful treatment methods for stage 1 (cT1N0M0) rectal NETs. Hybrid ESD was employed in cases where the execution of full submucosal dissection posed challenges or carried a heightened risk of perforation compared to ESD[11]. Consequently, hybrid ESD offers distinct advantages for lesions situated in anatomically challenging sites or exhibiting submucosal fibrosis[12,13]. Besides, it is evident that hybrid ESD is inherently less complex than ESD[14,15]. Consequently, we propose that hybrid ESD may be a viable alternative for the management of rectal NETs < 20 mm. It should be noted, however, that the present investigation only included a collective of 28 lesions ranging in size from 10 mm to 20 mm. The majority of the lesions seen ranged from 10 mm to 15 mm, with an average size of 11.5 ± 2.7 mm. Hence, the results of our study are more likely favor the safety and efficacy of hybrid ESD as a viable treatment option for rectal NETs measuring less than 15 mm in size.

In the present investigation, the rate of R0 resection was 86.89% in the ESD, a finding that aligns with past research in this field. Pan et al[16] conducted a comprehensive assessment of 14 papers with a total of 823 cases involving endoscopic resection of rectal NETs measuring less than 10 mm. The findings of their meta-analysis revealed an overall R0 resection rate of 90.2%. Specifically, the R0 resection rate for ESD was 84.1%. Kim et al[17] provided a comprehensive summary of 277 cases with rectal NETs measuring less than 10 mm. The authors reported that the percentage of R0 varied between 72% and 74% across various endoscopic resection techniques. Li et al[18] found that the R0 endoscopic resection rate of rectal NETs less than 10 mm among 101 cases was 88.7%, which was also similar with our results.

There was no recurrence in any of the 12 cases in our analysis that had a positive vertical resection margin or vascular invasion. Microscopic examination revealed no trace of tumor cells in the five patients who had mucosal biopsy in the postoperative scar or the three patients who underwent salvage surgery. Therefore, whether salvage treatment is necessary for non-R0 endoscopic resection of stage 1 rectal NETs? A total of 407 cases of rectal NETs were studied retrospectively by Moon et al[19], with 148 cases receiving non-R0 endoscopic resection. Among the 148 cases, 14 underwent salvage surgery, and 134 opted for follow-up monitoring. There was no significant difference in the local recurrence rate between the non-R0 resection group and the R0 resection group (2.1% vs 1.2%) at a median follow-up of 56.8 months. The 322 cases of rectal NETs that were studied retrospectively by Cha et al[20] included 76 cases of non-R0 resection, 38 cases of which had salvage surgery, and 38 cases of which were solely followed up. There was a median follow-up of 40.5 months, with no evidence of either local recurrence or distant metastases among the 322 patients. According to a retrospective study by Li et al[21], 54 of 428 cases included non-R0 resection with no salvage therapy for rectal NETs. Patients were followed for a median of 38 months, during which no evidence of local tumor recurrence or distant metastasis was found. Because cauterization may eliminate nearby tumor cells, some endoscopists may not see pathologically positive resection margins as indicative of recurring or residual malignancies[16,22,23]. Some endoscopists may have decided against salvage therapy and instead opted for routine follow-up colonoscopy and biopsy of the resection site. It is possible that the cheap cost and high availability of colonoscopy in China have contributed to a decrease in the number of salvage procedures.

Tumor size, invasion depth, pathological grade, and endoscopic methods are all potential risk factors that might influence R0 resection, as indicated in a small number of prior studies[17,21,24-27]. An independent risk factor for non-R0 endoscopic resection was endoscopic morphological manifestation of rectal NETs, according to Wang et al[25]. Flat or slightly raised lesions (type II) and depression or ulcer on the surface of lesions (type III) were associated with a considerably greater risk of non-R0 resection than protruding lesions (type I), with corresponding ORs of 6.65 (95%CI: 1.24-35.74, P = 0.03), and 6.81 (95%CI: 1.06-43.56, P = 0.04). Tumor size was a risk factor for non-R0 resection of stage 1 rectal NETs by Zheng et al[24], with a 64% increase in the probability of non-R0 resection for every 1mm increase in tumor size (OR = 1.64, 95%CI: 1.59-4.39, P < 0.001). Kim et al[17] demonstrated that the likelihood of endoscopic R0 resection of stage 1 rectal NETs dropped by 10% for every 1 mm rise in tumor size (OR 0.90, 95%CI 0.82-0.99, P = 0.02). Central depression on the surface of the tumor was associated with an increased probability of non-R0 endoscopic resection, as shown by Choi et al[27] (OR = 11.53, 95%CI: 2.38-55.92, P = 0.002). Uni- and multivariate analysis of our data revealed that, unlike tumor size and morphological presentation, ESD operating experience was linked with non-R0 resection. However, only 11 non-R0 endoscopic resection instances were included in our analysis. These negative findings should be approached with caution due to the limited sample size.

The present research exhibits some strengths and limitations that need careful assessment. One notable strength of this research is its comparison of the safety and effectiveness of ESD vs hybrid ESD in the treatment of stage 1 rectal NETs. Hybrid ESD is inherently less complex than ESD, and the present study found that hybrid ESD could be equally effective as ESD in achieving R0 resection, while also being less time-consuming, for stage 1 rectal NETs. Hybrid ESD could be advantageous in scenarios where the presence of submucosal fibrosis complicates the ESD process and poses a higher risk of perforation. Thus, the present results demonstrate a significant finding with clear clinical implications. Nevertheless, this research is constrained by its restricted sample size, increasing the risk of a type II error, indicating that there may be differences that the study failed to detect. Especially, the incidence of both a specific complication and overall complications is low, which make it difficult to find significant differences. As a result, it is imperative that the findings and conclusions drawn from our investigation are needed to be substantiated by the implementation of multicenter studies encompassing a larger sample size. Second, it is important to note that the present investigation was retrospective and single-center, potentially introducing possible selection bias when comparing the outcomes of ESD with hybrid ESD. Third, a subset of patients had a limited duration of follow-up. Fourth, the choice for ESD or hybrid ESD was not standardized and was made by the appointed endoscopist. Therefore, there is selection bias in this study.

It was determined that both ESD and hybrid ESD are deemed as safe and efficacious methods for the removal of stage 1 rectal NETs. Hybrid ESD may serve as a viable substitute for ESD in achieving R0 resection of rectal NETs measuring less than 20 mm. This is particularly relevant in cases where accomplishing a thorough submucosal dissection proved challenging or carried a greater likelihood of perforation when using ESD. It is necessary to conduct extensive, prospective, randomized studies to validate these recommendations.

| 1. | Eick J, Steinberg J, Schwertner C, Ring W, Scherübl H. [Rectal neuroendocrine tumors: endoscopic therapy]. Chirurg. 2016;87:288-291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Taghavi S, Jayarajan SN, Powers BD, Davey A, Willis AI. Examining rectal carcinoids in the era of screening colonoscopy: a surveillance, epidemiology, and end results analysis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2013;56:952-959. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Jung YS, Yun KE, Chang Y, Ryu S, Park JH, Kim HJ, Cho YK, Sohn CI, Jeon WK, Kim BI, Park DI. Risk factors associated with rectal neuroendocrine tumors: a cross-sectional study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2014;23:1406-1413. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Weinstock B, Ward SC, Harpaz N, Warner RR, Itzkowitz S, Kim MK. Clinical and prognostic features of rectal neuroendocrine tumors. Neuroendocrinology. 2013;98:180-187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | McDermott FD, Heeney A, Courtney D, Mohan H, Winter D. Rectal carcinoids: a systematic review. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:2020-2026. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ramage JK, De Herder WW, Delle Fave G, Ferolla P, Ferone D, Ito T, Ruszniewski P, Sundin A, Weber W, Zheng-Pei Z, Taal B, Pascher A; Vienna Consensus Conference participants. ENETS Consensus Guidelines Update for Colorectal Neuroendocrine Neoplasms. Neuroendocrinology. 2016;103:139-143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 185] [Cited by in RCA: 239] [Article Influence: 23.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Shah MH, Goldner WS, Benson AB, Bergsland E, Blaszkowsky LS, Brock P, Chan J, Das S, Dickson PV, Fanta P, Giordano T, Halfdanarson TR, Halperin D, He J, Heaney A, Heslin MJ, Kandeel F, Kardan A, Khan SA, Kuvshinoff BW, Lieu C, Miller K, Pillarisetty VG, Reidy D, Salgado SA, Shaheen S, Soares HP, Soulen MC, Strosberg JR, Sussman CR, Trikalinos NA, Uboha NA, Vijayvergia N, Wong T, Lynn B, Hochstetler C. Neuroendocrine and Adrenal Tumors, Version 2.2021, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2021;19:839-868. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 391] [Article Influence: 78.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Chen X, Li B, Wang S, Yang B, Zhu L, Ma S, Wu J, He Q, Zhao J, Zheng Z, Li S, Wang T, Liang L. Efficacy and safety of endoscopic submucosal dissection for gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors: a 10-year data analysis of Northern China. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2019;54:384-389. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Yong JN, Lim XC, Nistala KRY, Lim LKE, Lim GEH, Quek J, Tham HY, Wong NW, Tan KK, Chong CS. Endoscopic submucosal dissection versus endoscopic mucosal resection for rectal carcinoid tumor. A meta-analysis and meta-regression with single-arm analysis. J Dig Dis. 2021;22:562-571. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Rinke A, Ambrosini V, Dromain C, Garcia-Carbonero R, Haji A, Koumarianou A, van Dijkum EN, O'Toole D, Rindi G, Scoazec JY, Ramage J. European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society (ENETS) 2023 guidance paper for colorectal neuroendocrine tumours. J Neuroendocrinol. 2023;35:e13309. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 33.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | Byeon JS, Yang DH, Kim KJ, Ye BD, Myung SJ, Yang SK, Kim JH. Endoscopic submucosal dissection with or without snaring for colorectal neoplasms. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:1075-1083. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | McCarty TR, Bazarbashi AN, Thompson CC, Aihara H. Hybrid endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) compared with conventional ESD for colorectal lesions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Endoscopy. 2021;53:1048-1058. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Esaki M, Ihara E, Sumida Y, Fujii H, Takahashi S, Haraguchi K, Iwasa T, Somada S, Minoda Y, Ogino H, Tagawa K, Ogawa Y. Hybrid and Conventional Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection for Early Gastric Neoplasms: A Multi-Center Randomized Controlled Trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;21:1810-1818.e8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Milano RV, Viale E, Bartel MJ, Notaristefano C, Testoni PA. Resection outcomes and recurrence rates of endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) and hybrid ESD for colorectal tumors in a single Italian center. Surg Endosc. 2018;32:2328-2339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Yang B, Shen J, Zhong W, Han H, Lu P, Jiang F. Conventional versus hybrid knife endoscopic submucosal dissection in large colorectal laterally spreading tumors: A propensity score analysis. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2023;29:111-118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Pan J, Zhang X, Shi Y, Pei Q. Endoscopic mucosal resection with suction vs. endoscopic submucosal dissection for small rectal neuroendocrine tumors: a meta-analysis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2018;53:1139-1145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kim J, Kim JH, Lee JY, Chun J, Im JP, Kim JS. Clinical outcomes of endoscopic mucosal resection for rectal neuroendocrine tumor. BMC Gastroenterol. 2018;18:77. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Li D, Xie J, Hong D, Liu G, Wang R, Jiang C, Ye Z, Xu B, Wang W. Efficacy and safety of ligation-assisted endoscopic submucosal resection combined with endoscopic ultrasonography for treatment of rectal neuroendocrine tumors. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2022;57:734-739. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Moon CM, Huh KC, Jung SA, Park DI, Kim WH, Jung HM, Koh SJ, Kim JO, Jung Y, Kim KO, Kim JW, Yang DH, Shin JE, Shin SJ, Kim ES, Joo YE. Long-Term Clinical Outcomes of Rectal Neuroendocrine Tumors According to the Pathologic Status After Initial Endoscopic Resection: A KASID Multicenter Study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:1276-1285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Cha JH, Jung DH, Kim JH, Youn YH, Park H, Park JJ, Um YJ, Park SJ, Cheon JH, Kim TI, Kim WH, Lee HJ. Long-term outcomes according to additional treatments after endoscopic resection for rectal small neuroendocrine tumors. Sci Rep. 2019;9:4911. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Li Y, Pan F, Sun G, Wang ZK, Meng K, Peng LH, Lu ZS, Dou Y, Yan B, Liu QS. Risk Factors and Clinical Outcomes of 54 Cases of Rectal Neuroendocrine Tumors with Incomplete Resection: A Retrospective Single-Center Study. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2021;17:1153-1161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Park CH, Cheon JH, Kim JO, Shin JE, Jang BI, Shin SJ, Jeen YT, Lee SH, Ji JS, Han DS, Jung SA, Park DI, Baek IH, Kim SH, Chang DK. Criteria for decision making after endoscopic resection of well-differentiated rectal carcinoids with regard to potential lymphatic spread. Endoscopy. 2011;43:790-795. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Kwaan MR, Goldberg JE, Bleday R. Rectal carcinoid tumors: review of results after endoscopic and surgical therapy. Arch Surg. 2008;143:471-475. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Zheng Y, Guo K, Zeng R, Chen Z, Liu W, Zhang X, Liang W, Liu J, Chen H, Sha W. Prognosis of rectal neuroendocrine tumors after endoscopic resection: a single-center retrospective study. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2021;12:2763-2774. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Wang XY, Chai NL, Linghu EQ, Qiu ST, Li LS, Zou JL, Xiang JY, Li XX. The outcomes of modified endoscopic mucosal resection and endoscopic submucosal dissection for the treatment of rectal neuroendocrine tumors and the value of endoscopic morphology classification in endoscopic resection. BMC Gastroenterol. 2020;20:200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Kim HH, Park SJ, Lee SH, Park HU, Song CS, Park MI, Moon W. Efficacy of endoscopic submucosal resection with a ligation device for removing small rectal carcinoid tumor compared with endoscopic mucosal resection: analysis of 100 cases. Dig Endosc. 2012;24:159-163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Choi CW, Park SB, Kang DH, Kim HW, Kim SJ, Nam HS, Ryu DG. The clinical outcomes and risk factors associated with incomplete endoscopic resection of rectal carcinoid tumor. Surg Endosc. 2017;31:5006-5011. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/