Published online Nov 24, 2025. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v16.i11.111397

Revised: July 23, 2025

Accepted: October 9, 2025

Published online: November 24, 2025

Processing time: 142 Days and 23.3 Hours

Cancer survivorship is a growing concern globally, yet few studies have explored the quality of life (QoL) outcomes among survivors in the Middle East, particularly in Saudi Arabia.

To assess QoL using the World Health Organization Quality of Life-BREF (WHOQOL-BREF) and to evaluate the impact of demographic and clinical factors among Saudi cancer survivors.

We conducted a cross-sectional study of 102 adult cancer survivors recruited from a tertiary hospital in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Participants completed the WHOQOL-BREF, which assesses four QoL domains, including physical health, psychological health, social relationships, and environment. Univariate and multivariable robust linear regression models (Huber estimator) were used to identify QoL score pre

The mean participant age was 44.5 years; 72.5% of the participants were female. The mean domain scores were as follows: physical health was 3.05 ± 0.53, psychological health was 3.56 ± 0.79, social relationships was 3.39 ± 0.84, and envi

Our findings reveal noticeable disparities in QoL among Saudi cancer survivors driven by socioeconomic and demographic factors. These insights underscore the need for context-sensitive survivorship programs in Saudi Arabia, with special attention to social support, mental health, and economic stability.

Core Tip: This study highlights significant disparities in quality of life (QoL) among cancer survivors in Saudi Arabia using the World Health Organization Quality of Life-BREF instrument. It identifies key socioeconomic and demographic predictors—such as rural residence, low income, and limited education—that negatively influence domain-specific QoL. These findings underscore the urgent need for culturally and contextually tailored survivorship programs that address social vulnerability, mental health, and environmental support in Middle Eastern settings.

- Citation: Alsharif FH. Quality of life among Saudi cancer survivors: The role of social and demographic factors. World J Clin Oncol 2025; 16(11): 111397

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-4333/full/v16/i11/111397.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5306/wjco.v16.i11.111397

The global burden of cancer survivorship has intensified with advances in early diagnosis, treatment, and supportive care, leading to increased life expectancy and a growing population of individuals surviving after cancer[1]. However, survivorship is not only about prolonging life but also about enhancing its quality. Health-related quality of life (QoL) has emerged as a critical outcome metric, encompassing the physical, psychological, social, and environmental well-being of individuals after cancer treatment[2]. The World Health Organization Quality of Life-BREF (WHOQOL-BREF) instrument has been widely adopted across cultures and cancer populations as a multidimensional tool to capture survivors' subjective experiences[3,4].

In Saudi Arabia, the number of cancer survivors has steadily increased due to national screening programs, improved access to oncology care, and substantial investment in health services under vision 2030[5-7]. According to Global Cancer Observatory studies, over 28000 new cancer cases were reported in 2022, and survival rates have improved significantly for common cancers such as breast, colorectal, and prostate cancer[8,9]. However, the psychosocial and QoL outcomes of Saudi cancer survivors remain understudied[10-13]. Cultural values, gender norms, social cohesion, and familial structures in the Kingdom are distinct and may modulate the survivor experience in unique ways[14]. For example, family-based support systems often buffer psychological distress, while societal stigma around cancer, particularly among women, may impede open discussion or emotional expression.

The existing literature on cancer survivorship in high-income countries has consistently shown that sociodemographic and clinical factors such as age, gender, income, education, and comorbidities significantly influence health-related QoL (HRQoL) outcomes[15]. However, data from Middle Eastern contexts, including Saudi Arabia, remain limited and fragmented. Some local studies have focused on specific cancer types, such as breast[16] or colorectal cancer[17], often without standardized tools or with small sample sizes that limit generalizability. Furthermore, few investigations have utilized validated cross-culturally appropriate instruments like the WHOQOL-BREF to assess comprehensive QoL domains. This study addresses a critical gap by employing the WHOQOL-BREF to examine QoL outcomes among a diverse cohort of Saudi cancer survivors across age groups, cancer types, and socioeconomic backgrounds. Importantly, the analysis situates survivor well-being within the framework of the social determinants of health, recognizing that medical recovery alone does not ensure psychological or social reintegration. By capturing variations in HRQoL across demographic variables such as gender, education, marital status, employment, income, and housing conditions, the study aligns with growing calls in global oncology for equity-oriented survivorship research. The Saudi context provides a compelling setting for this analysis. While the healthcare system offers comprehensive cancer care at no direct cost to citizens, disparities persist in access, continuity of care, and psychosocial support services[18]. In addition, regional disparities, for instance, between urban and rural settings may influence environmental and social QoL domains[18,19]. The prevailing collectivist culture emphasizes familial interdependence and may impact perceptions of autonomy, social support, and psychological adjustment. Understanding how these culturally embedded factors interact with demo

This paper seeks to: (1) Describe the QoL profiles of Saudi cancer survivors using domain-level WHOQOL-BREF scores; (2) Identify sociodemographic and clinical predictors of physical, psychological, social, and environmental well-being; and (3) Highlight disparities that could inform future policies and survivorship programs tailored to the Saudi context. By doing so, this study contributes to the global literature on cancer survivorship while offering policy-relevant insights for regional health planning. In line with the global emphasis on equity, cultural relevance, and public health impact, this study underscores the importance of integrating QoL metrics into routine cancer care[20]. Ultimately, improving survivorship outcomes requires not only biomedical interventions but also a deep understanding of the social realities that shape the lived experience of cancer patients in diverse settings such as Saudi Arabia.

This cross-sectional study was conducted for up to three months at the oncology outpatient clinics and survivorship of a tertiary hospital located in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. The hospital serves a diverse urban population and is a referral center for cancer care in the western region of the Kingdom.

Eligible participants were adult (aged ≥ 18 years) Saudi cancer survivors with a histologically confirmed diagnosis of any cancer type who had completed their primary treatment at least 6 months before enrollment. Patients were recruited using convenience sampling during routine follow-up visits. Participants were approached in the clinic waiting area and invited to complete the survey after obtaining verbal and written informed consent. A total of 115 patients were approached; 102 consented and completed the questionnaire (response rate: 88.7%). Reasons for non-participation included time constraints and lack of interest. All participants were fluent in Arabic, and no translations were required.

Although no formal a priori power calculation was conducted due to the exploratory nature of the study, a minimum target of 100 participants was set to allow for multivariable regression analyses with up to 10 predictors (based on the rule of 10 events per variable)[21]. This sample size is consistent with comparable QoL studies conducted among cancer survivors in regional settings.

To accommodate cultural sensitivities specific to the Saudi context, several procedural safeguards were implemented. Gender-matched research assistants explained the study objectives and obtained consent to reduce participant discomfort. Surveys were completed in private settings without family members present, and participants were assured of strict confidentiality and the anonymity of their responses. These measures were intended to minimize social desirability bias and encourage honest reporting, particularly in domains considered culturally sensitive, such as psychological health, social relationships, and QoL.

QoL was measured using the WHOQOL-BREF, a validated 26-item instrument[22]. The tool includes four core domains. including physical health (7 items), psychological health (6 items), social relationships (3 items), and environment (8 items). Two general items assessed overall QoL and general health satisfaction. Each item was rated on a 5-point Likert scale. Negatively worded items were reverse-coded. Domain scores were calculated by computing the mean of valid responses within each domain. Scores were retained in their raw form (1-5 scale) to reflect natural response distribution and maintain interpretability.

The WHOQOL-BREF instrument has been extensively validated across diverse populations, including those with chronic illnesses and cancer survivors[23-25]. Its four-domain structure has demonstrated strong construct and criterion validity in previous Arabic and international validation studies. In our sample, internal consistency reliability was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha. The overall Cronbach’s alpha for the 26-item WHOQOL-BREF scale was 0.89, indicating high internal reliability. Domain-specific alpha values were also acceptable, with values exceeding the recommended threshold of 0.70, supporting the instrument’s internal coherence in assessing QoL constructs within the Saudi cancer survivor population. Additionally, domain items were inspected for content relevance, cultural appropriateness, and response variability. No floor or ceiling effects were observed, and inter-item correlations supported the scale’s internal structure.

Responses were reviewed for completeness. Participants were required to have completed at least 75% of the items within each domain for inclusion in the domain-level analysis. Data entry was performed by two independent research assistants using double-entry verification. Discrepancies were resolved through audit trails. Data were stored in encrypted, access-controlled files.

The primary outcomes in this study were the four QoL domain scores measured using the WHOQOL-BREF instrument, namely physical health, psychological health, social relationships, and environment. Each domain score was calculated by averaging the respective items after applying reverse coding where appropriate, with higher scores indicating better QoL. These continuous outcomes were treated as dependent variables in the analysis. The selection of independent variables was informed by the prior literature on cancer survivorship and the social determinants of health, as well as the theoretical framework of the WHOQOL-BREF. Sociodemographic predictors included age (categorized into deciles: 20-25 years, 26-30 years, 31-35 years, ..., ≥ 61 years), gender (male or female), marital status (single, married, divorced, widowed), level of education (primary, secondary, bachelor’s degree, postgraduate), employment status (employed, unemployed, retired), and monthly household income (≤ 5000 SAR, 6000-10000 SAR, 11000-15000 SAR, and ≥ 16000 SAR). Additional variables included residential setting (urban vs rural) and housing status (owned vs rented). Clinical predictors were derived from self-reported chronic disease history and included hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, respiratory disease, neurological disease, cardiovascular disease, and kidney disease. Each of these comorbidities was modeled as a binary variable (presence vs absence). The time since completing primary cancer treatment was standardized at a minimum of six months for all participants.

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB No. 1F.34). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Data were anonymized, and confidentiality was maintained throughout the study.

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize participant characteristics. Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages, while continuous variables were reported as mean ± SD or median (interquartile range), as appropriate. Univariate analyses were performed to explore associations between demographic/clinical variables and each QoL domain using t-tests or a one-way ANOVA for categorical predictors. Domain scores were modeled as con

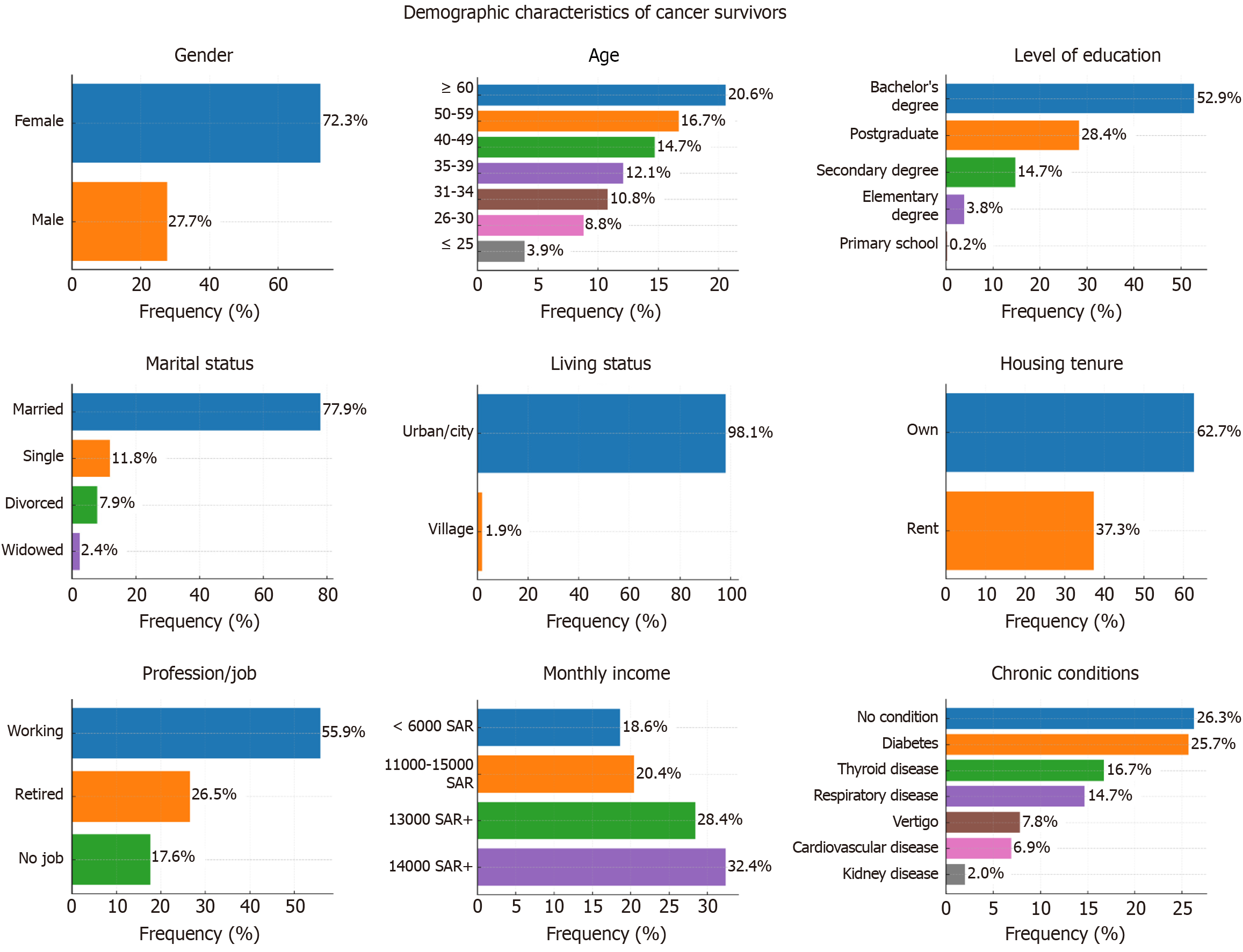

A total of 102 cancer survivors were included in the analysis. The majority were female [74 (72.5%)], while 28 (27.5%) were male. Most participants held a bachelor’s degree [54 (52.9%)], followed by postgraduates [29 (28.4%)] and those with a secondary degree [15 (14.7%)]. Only four participants (3.9%) had no formal education. Regarding marital status, 69 (67.6%) of the participants were married, while 13 (12.7%) were divorced and 11 (10.8%) were widowed; a minority [9 (8.8%)] were single. Most participants lived with family members [91 (89.2%)], and 67 (65.7%) lived in houses they owned. The rest either rented [28 (27.5%)] or lived in housing owned by others [7 (6.9%)]. In terms of employment, 34 (33.3%) were employed in professional jobs, 29 (28.4%) were unemployed, 20 (19.6%) were retired, and the remainder were students or held administrative or technical roles. The most common age category was "61 or more" [21 (20.6%)], followed by 51-60 years [20 (19.6%)] and 41-50 years [19 (18.6%)]. Monthly income varied widely: 33 (32.4%) participants reported earning 16000 SAR or more, while 18 (17.6%) earned less than SAR 5000. Almost all participants [100 (98.0%)] reported having at least one chronic disease, the most common being hypertension, diabetes, or thyroid disorders (frequencies detailed in Table 1, Figure 1).

| Variable | Category | n1 | % |

| Age (year) | 61 or more | 21 | 20.6 |

| 56-60 | 17 | 16.7 | |

| 36-40 | 15 | 14.7 | |

| 41-45 | 13 | 12.7 | |

| 46-50 | 11 | 10.8 | |

| 31-35 | 11 | 10.8 | |

| 51-55 | 9 | 8.8 | |

| 26-30 | 1 | 1 | |

| 20-25 | 4 | 3.9 | |

| Gender | Male | 28 | 27.5 |

| Level of education | Bachelor degree | 54 | 52.9 |

| Post-graduate | 29 | 28.4 | |

| Secondary degree | 15 | 14.7 | |

| Elementary degree | 3 | 2.9 | |

| Primary degree | 1 | 1 | |

| Marital status | Married | 79 | 77.5 |

| Single | 12 | 11.8 | |

| Divorced | 8 | 7.8 | |

| Widow | 3 | 2.9 | |

| Living status | Urban city | 98 | 96.1 |

| Village | 4 | 3.9 | |

| Is it your house that you live in? | Owner | 64 | 62.7 |

| Rent | 38 | 37.3 | |

| Profession/job | working | 57 | 55.9 |

| Retired | 27 | 26.5 | |

| No job | 18 | 17.6 | |

| What is the chronic disease that you suffer from? | Hypertension | 27 | 26.5 |

| Diabetes | 26 | 25.5 | |

| High cholesterol | 17 | 16.7 | |

| Respiratory disease | 15 | 14.7 | |

| Neurological disease | 8 | 7.8 | |

| Cardiovascular/heart disease | 7 | 6.9 | |

| Kidney/renal disease | 2 | 2 | |

| Monthly income (SAR) | 16000 or more | 33 | 32.4 |

| 1000-5000 | 29 | 28.4 | |

| 11000-15000 | 21 | 20.6 | |

| 6000-10000 | 19 | 18.6 |

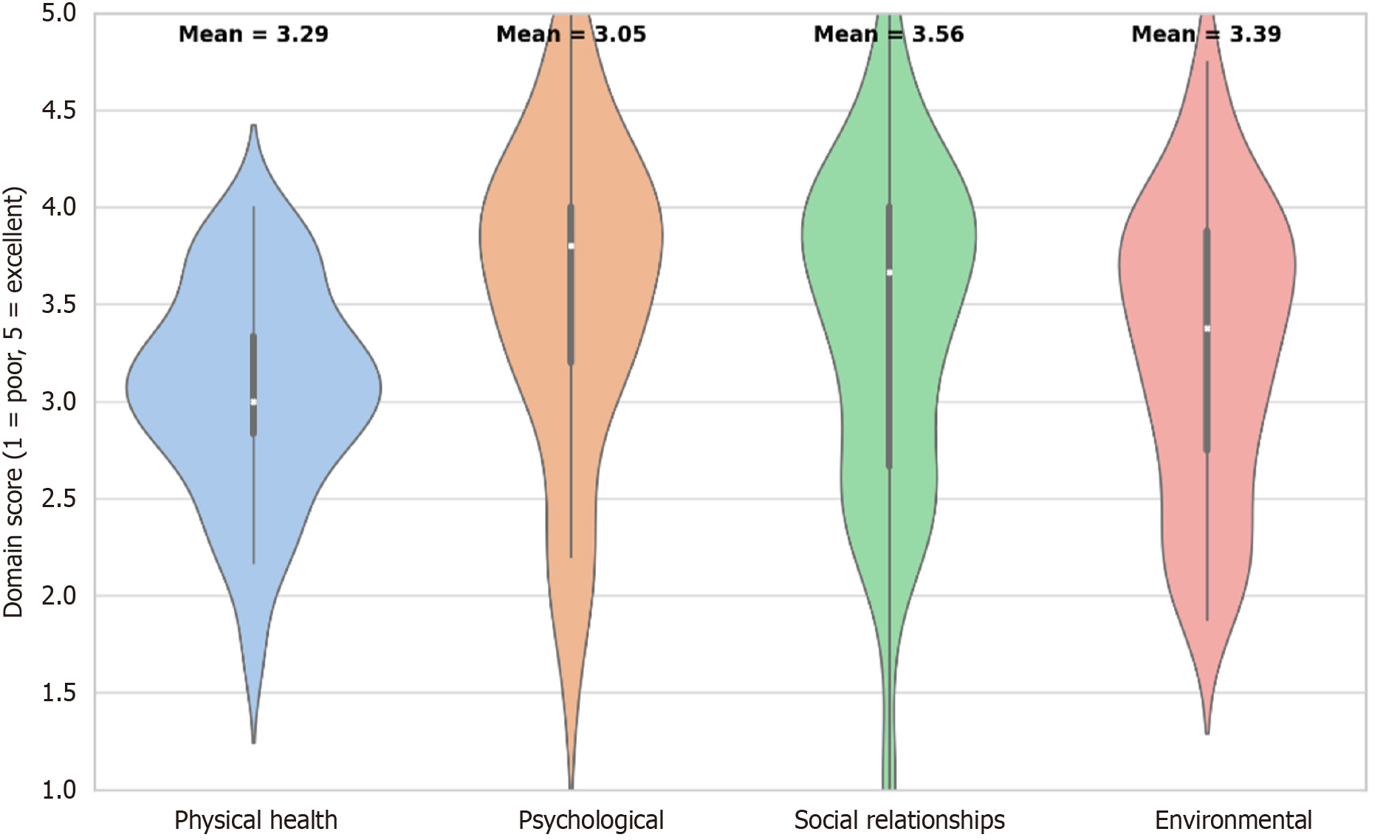

Figure 2 presents the distribution of the WHOQOL-BREF domain scores among Saudi cancer survivors. Among the four QoL domains, social relationships had the highest mean score (3.56), followed by environmental (3.39), physical health (3.29), and psychological well-being, which had the lowest average score (3.05). All domains demonstrated moderate variability, with scores ranging from approximately 1.5 to 5 on a five-point Likert scale. These findings suggest that while survivors generally report moderate-to-good well-being, psychological health may represent a relative area of concern requiring targeted support.

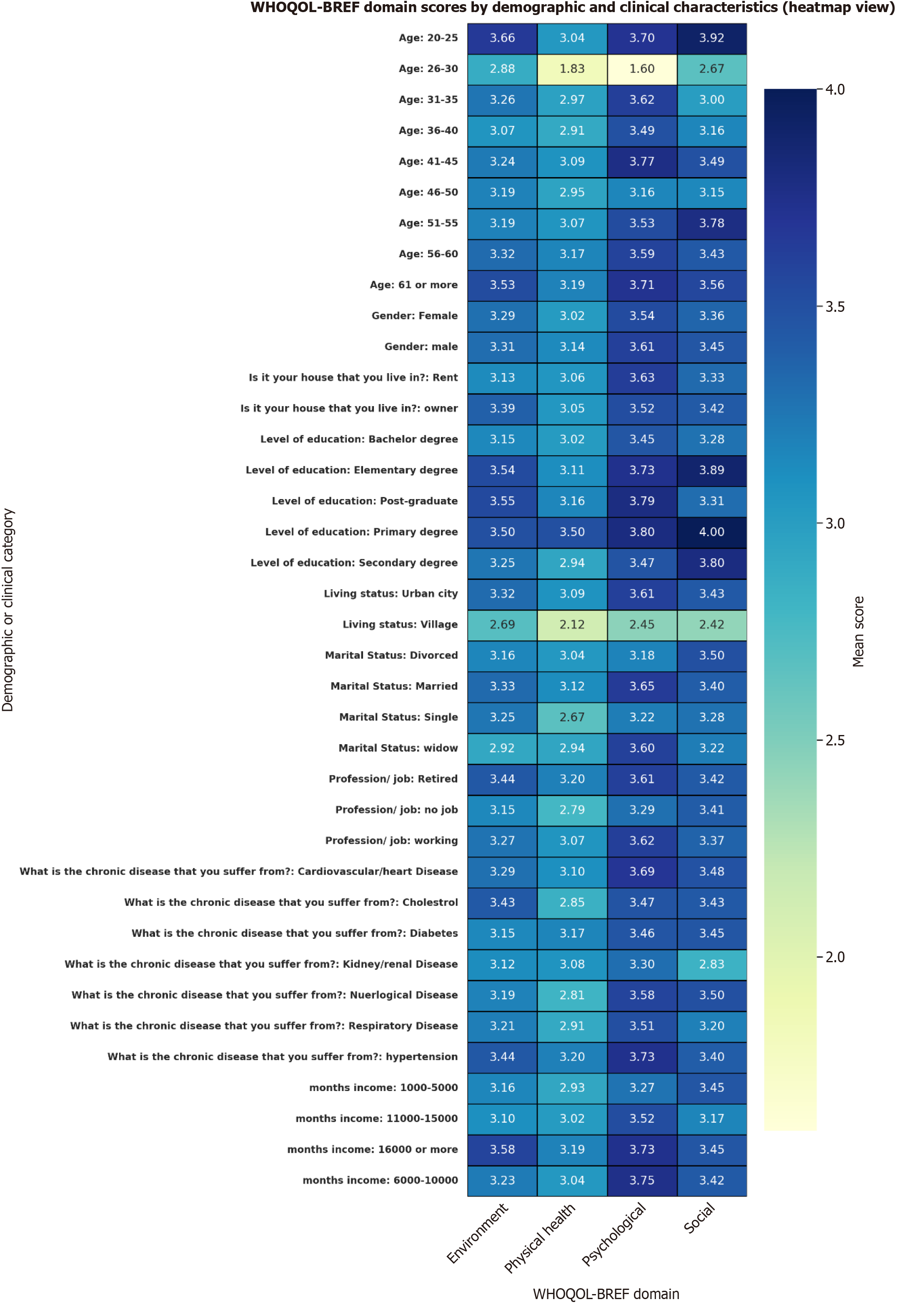

Figure 3 displays a heatmap of mean WHOQOL-BREF domain scores stratified by demographic and clinical characteristics. Table 2 provides the corresponding univariate statistics. While most subgroup comparisons did not reach statistical significance, several trends were notable. Participants living in urban areas reported consistently higher scores across all four domains, particularly in the psychological (mean = 3.61 vs 2.45, P < 0.001) and social relationships (mean = 3.43 vs 2.42, P = 0.02) domains compared to those residing in villages. Similarly, retired individuals and those in full-time employment reported better physical health scores than unemployed participants (P = 0.04), though social and environmental scores did not significantly differ by job status.

| Variable | Category | Environment mean | Physical health mean | Psychological mean | Social mean | Environment P value | Physical health P value | Psychological P value | Social P value |

| Age (year) | 20-25 | 3.66 | 3.04 | 3.7 | 3.92 | 0.73 | 0.34 | 0.21 | 0.29 |

| 26-30 | 2.88 | 1.83 | 1.6 | 2.67 | 0.73 | 0.34 | 0.21 | 0.29 | |

| 31-35 | 3.26 | 2.97 | 3.62 | 3 | 0.73 | 0.34 | 0.21 | 0.29 | |

| 36-40 | 3.07 | 2.91 | 3.49 | 3.16 | 0.73 | 0.34 | 0.21 | 0.29 | |

| 41-45 | 3.24 | 3.09 | 3.77 | 3.49 | 0.73 | 0.34 | 0.21 | 0.29 | |

| 46-50 | 3.19 | 2.95 | 3.16 | 3.15 | 0.73 | 0.34 | 0.21 | 0.29 | |

| 51-55 | 3.19 | 3.07 | 3.53 | 3.78 | 0.73 | 0.34 | 0.21 | 0.29 | |

| 56-60 | 3.32 | 3.17 | 3.59 | 3.43 | 0.73 | 0.34 | 0.21 | 0.29 | |

| 61 or more | 3.53 | 3.19 | 3.71 | 3.56 | 0.73 | 0.34 | 0.21 | 0.29 | |

| Gender | Female | 3.29 | 3.02 | 3.54 | 3.36 | 0.88 | 0.34 | 0.68 | 0.64 |

| Male | 3.31 | 3.14 | 3.61 | 3.45 | 0.88 | 0.34 | 0.68 | 0.64 | |

| Is it your house that you live in? | Rent | 3.13 | 3.06 | 3.63 | 3.33 | 0.09 | 0.91 | 0.52 | 0.61 |

| Owner | 3.39 | 3.05 | 3.52 | 3.42 | 0.09 | 0.91 | 0.52 | 0.61 | |

| Level of education | Bachelor degree | 3.15 | 3.02 | 3.45 | 3.28 | 0.21 | 0.60 | 0.44 | 0.17 |

| Elementary degree | 3.54 | 3.11 | 3.73 | 3.89 | 0.21 | 0.60 | 0.44 | 0.17 | |

| Post-graduate | 3.55 | 3.16 | 3.79 | 3.31 | 0.21 | 0.60 | 0.44 | 0.17 | |

| Primary degree | 3.5 | 3.5 | 3.8 | 4 | 0.21 | 0.60 | 0.44 | 0.17 | |

| Secondary degree | 3.25 | 2.94 | 3.47 | 3.8 | 0.21 | 0.60 | 0.44 | 0.17 | |

| Living status | Urban city | 3.32 | 3.09 | 3.61 | 3.43 | 0.09 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 |

| Village | 2.69 | 2.12 | 2.45 | 2.42 | 0.09 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | |

| Marital status | Divorced | 3.16 | 3.04 | 3.18 | 3.5 | 0.74 | 0.05 | 0.16 | 0.93 |

| Married | 3.33 | 3.12 | 3.65 | 3.4 | 0.74 | 0.05 | 0.16 | 0.93 | |

| Single | 3.25 | 2.67 | 3.22 | 3.28 | 0.74 | 0.05 | 0.16 | 0.93 | |

| Widow | 2.92 | 2.94 | 3.6 | 3.22 | 0.74 | 0.05 | 0.16 | 0.93 | |

| Profession/job | Retired | 3.44 | 3.2 | 3.61 | 3.42 | 0.39 | 0.04 | 0.28 | 0.96 |

| No job | 3.15 | 2.79 | 3.29 | 3.41 | 0.39 | 0.04 | 0.28 | 0.96 | |

| Working | 3.27 | 3.07 | 3.62 | 3.37 | 0.39 | 0.04 | 0.28 | 0.96 | |

| What is the chronic disease that you suffer from? | Cardiovascular/heart disease | 3.29 | 3.1 | 3.69 | 3.48 | 0.80 | 0.20 | 0.90 | 0.92 |

| Cholesterol | 3.43 | 2.85 | 3.47 | 3.43 | 0.80 | 0.20 | 0.90 | 0.92 | |

| Diabetes | 3.15 | 3.17 | 3.46 | 3.45 | 0.80 | 0.20 | 0.90 | 0.92 | |

| Kidney/renal disease | 3.12 | 3.08 | 3.3 | 2.83 | 0.80 | 0.20 | 0.90 | 0.92 | |

| Nuerlogical disease | 3.19 | 2.81 | 3.58 | 3.5 | 0.80 | 0.20 | 0.90 | 0.92 | |

| Respiratory disease | 3.21 | 2.91 | 3.51 | 3.2 | 0.80 | 0.20 | 0.90 | 0.92 | |

| Hypertension | 3.44 | 3.2 | 3.73 | 3.4 | 0.80 | 0.20 | 0.90 | 0.92 | |

| Monthly income (SAR) | 1000-5000 | 3.16 | 2.93 | 3.27 | 3.45 | 0.06 | 0.28 | 0.09 | 0.64 |

| 11000-15000 | 3.1 | 3.02 | 3.52 | 3.17 | 0.06 | 0.28 | 0.09 | 0.64 | |

| 16000 or more | 3.58 | 3.19 | 3.73 | 3.45 | 0.06 | 0.28 | 0.09 | 0.64 | |

| 6000-10000 | 3.23 | 3.04 | 3.75 | 3.42 | 0.06 | 0.28 | 0.09 | 0.64 |

There was a noticeable positive gradient in scores across income levels, with the highest QoL scores observed in participants earning ≥ 16000 SAR/month, particularly in the psychological (mean = 3.73) and environmental (mean = 3.58) domains. While P values for income categories approached significance in the psychological domain (P = 0.09), they were not statistically significant for other domains. Marital status showed some association with psychological and physical health. Married survivors had slightly higher psychological scores (mean = 3.65) than widowed or single participants, though differences did not reach statistical significance. Notably, the 26-30 years age group had the lowest psychological (mean = 1.60) and physical (mean = 1.83) scores among all age groups, suggesting a potential vulnerability in younger adult survivors. Educational attainment was not significantly associated with domain scores, although individuals with primary or elementary education had the highest reported scores in most domains, including social relationships (mean = 4.0) and environment (mean = 3.54-3.55). Gender and housing status (owner vs renter) were not significantly associated with QoL domains. Overall, these univariate results suggest potential disparities in QoL by place of residence, employment, income, and age. These trends were further explored and adjusted in the multivariable models.

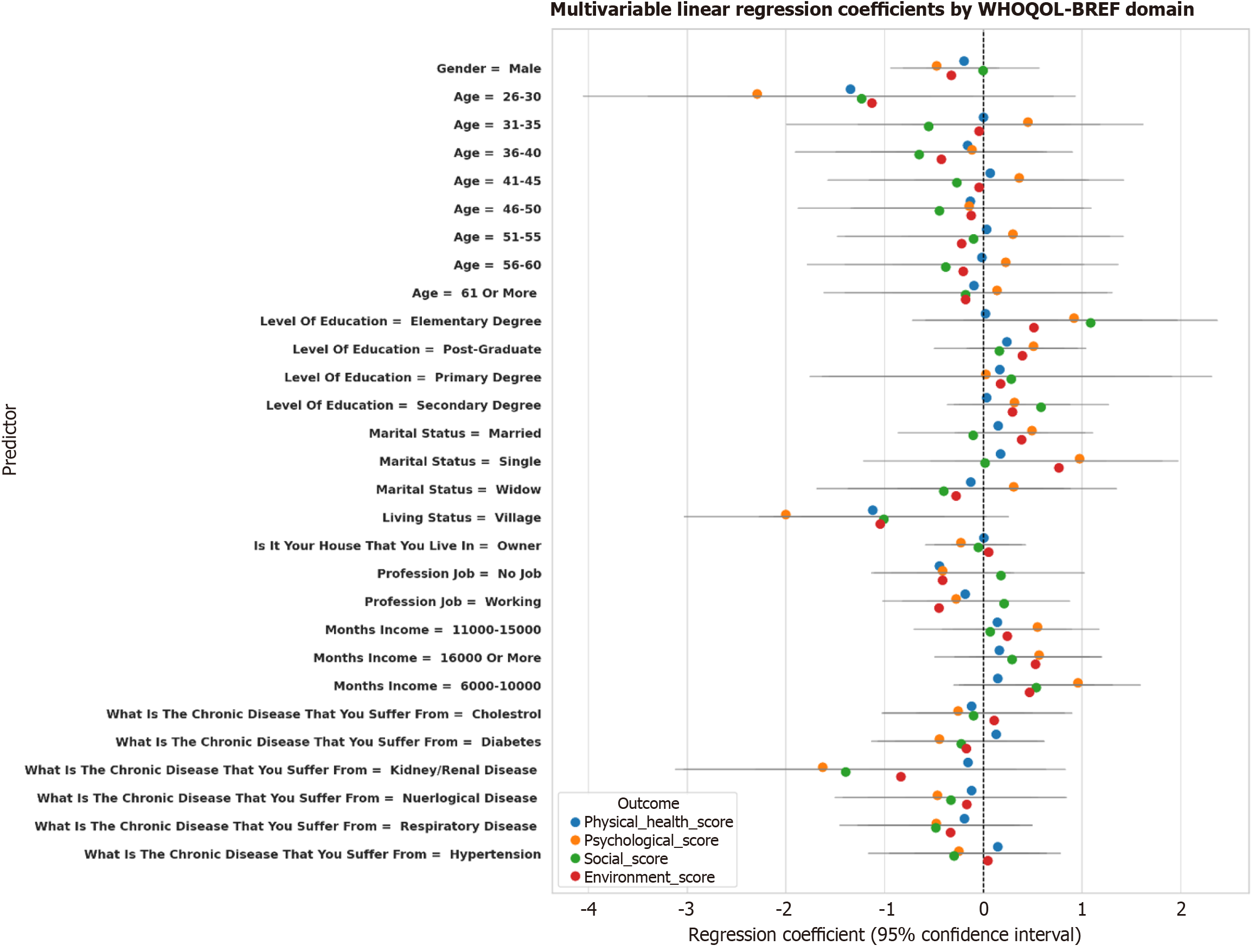

We included 102 adult cancer survivors in the analysis, with a mean age of 44.5 years. Most participants were female, and the majority reported having at least one chronic disease. The mean domain scores were 3.05 ± 0.53 for physical health, 3.56 ± 0.79 for psychological health, 3.39 ± 0.84 for social relationships, and 3.29 ± 0.74 for environment. We examined the association between demographic characteristics and WHOQOL-BREF domain scores using multivariable linear regression (Tables 3 and 4, Figure 4). Below are the key findings for each domain.

| Predictor | Physical health | Psychological | ||||||

| Beta | CI lower | CI upper | P value | Beta | CI lower | CI upper | P value | |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male | -0.20 | -0.52 | 0.13 | 0.23 | -0.47 | -0.93 | -0.01 | 0.04 |

| Female | -1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Age (year) | ||||||||

| 26-30 | -1.35 | -2.58 | -0.11 | 0.03 | -2.29 | -4.05 | -0.53 | 0.01 |

| 31-35 | 0.00 | -0.82 | 0.82 | 1.00 | 0.45 | -0.71 | 1.62 | 0.44 |

| 36-40 | -0.16 | -0.88 | 0.56 | 0.66 | -0.11 | -1.13 | 0.90 | 0.82 |

| 41-45 | 0.07 | -0.68 | 0.82 | 0.85 | 0.36 | -0.70 | 1.42 | 0.50 |

| 46-50 | -0.13 | -0.95 | 0.68 | 0.75 | -0.14 | -1.30 | 1.02 | 0.81 |

| 51-55 | 0.03 | -0.75 | 0.82 | 0.93 | 0.30 | -0.82 | 1.42 | 0.60 |

| 56-60 | -0.02 | -0.82 | 0.79 | 0.97 | 0.23 | -0.91 | 1.37 | 0.69 |

| 61 or more | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Level of education | ||||||||

| Elementary degree | 0.02 | -0.72 | 0.76 | 0.96 | 0.92 | -0.13 | 1.96 | 0.08 |

| Post-graduate | 0.24 | -0.14 | 0.61 | 0.21 | 0.51 | -0.02 | 1.04 | 0.06 |

| Primary degree | 0.17 | -1.00 | 1.33 | 0.78 | 0.03 | -1.63 | 1.68 | 0.97 |

| Secondary degree | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Marital status | ||||||||

| Married | 0.15 | -0.28 | 0.58 | 0.49 | 0.49 | -0.12 | 1.11 | 0.11 |

| Single | 0.18 | -0.53 | 0.88 | 0.62 | 0.97 | -0.02 | 1.97 | 0.06 |

| Widow | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Village | -1.12 | -1.84 | -0.40 | 0.00 | -2.00 | -3.03 | -0.98 | 0.00 |

| Do you own or rent your current living? | ||||||||

| Own | 0.01 | -0.24 | 0.26 | 0.96 | -0.23 | -0.58 | 0.13 | 0.21 |

| Rent | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Employment status | -0.44 | -0.93 | 0.04 | 0.07 | -0.41 | -1.10 | 0.27 | 0.23 |

| Unemployed | 0.13 | -0.35 | 0.61 | 0.59 | -0.45 | -1.13 | 0.24 | 0.20 |

| Full time job | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Monthly income (SAR) | ||||||||

| 11000-15000 | 0.14 | -0.30 | 0.58 | 0.52 | 0.55 | -0.08 | 1.17 | 0.08 |

| 16000 or more | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 6000-10000 | 0.15 | -0.30 | 0.59 | 0.51 | 0.96 | 0.33 | 1.59 | 0.00 |

| Chronic diseases | ||||||||

| Cholesterol | -0.12 | -0.65 | 0.41 | 0.66 | -0.26 | -1.01 | 0.50 | 0.50 |

| Diabetes | 0.13 | -0.35 | 0.61 | 0.59 | -0.45 | -1.13 | 0.24 | 0.20 |

| Kidney/renal disease | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Neurological disease | -0.12 | -0.79 | 0.55 | 0.73 | -0.47 | -1.42 | 0.49 | 0.33 |

| Respiratory disease | -0.19 | -0.75 | 0.37 | 0.50 | -0.48 | -1.27 | 0.31 | 0.23 |

| Hypertension | 0.15 | -0.35 | 0.64 | 0.56 | -0.25 | -0.95 | 0.45 | 0.48 |

| Predictor | Social | Environment | ||||||

| Beta | CI lower | CI upper | P value | Beta | CI lower | CI upper | P value | |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male | 0.00 | -0.57 | 0.57 | 1.00 | -0.32 | -0.81 | 0.16 | 0.19 |

| Female | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Age (year) | ||||||||

| 26-30 | -1.23 | -3.39 | 0.93 | 0.26 | -1.13 | -2.97 | 0.71 | 0.22 |

| 31-35 | -0.55 | -1.99 | 0.88 | 0.44 | -0.04 | -1.27 | 1.18 | 0.94 |

| 36-40 | -0.65 | -1.90 | 0.60 | 0.31 | -0.43 | -1.49 | 0.64 | 0.43 |

| 41-45 | -0.27 | -1.57 | 1.04 | 0.68 | -0.04 | -1.15 | 1.07 | 0.94 |

| 46-50 | -0.45 | -1.87 | 0.98 | 0.53 | -0.12 | -1.34 | 1.09 | 0.84 |

| 51-55 | -0.10 | -1.48 | 1.28 | 0.89 | -0.22 | -1.39 | 0.96 | 0.71 |

| 56-60 | -0.38 | -1.78 | 1.02 | 0.59 | -0.20 | -1.40 | 0.99 | 0.73 |

| 61 or more | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Level of education | ||||||||

| Elementary degree | 1.09 | -0.20 | 2.37 | 0.10 | 0.51 | -0.58 | 1.61 | 0.35 |

| Post-graduate | 0.16 | -0.49 | 0.82 | 0.62 | 0.40 | -0.16 | 0.95 | 0.16 |

| Primary degree | 0.28 | -1.75 | 2.32 | 0.78 | 0.17 | -1.56 | 1.91 | 0.84 |

| Secondary degree | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Marital status | ||||||||

| Married | -0.10 | -0.86 | 0.65 | 0.79 | 0.39 | -0.25 | 1.03 | 0.23 |

| Single | 0.02 | -1.21 | 1.24 | 0.98 | 0.76 | -0.28 | 1.81 | 0.15 |

| Widow | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Village | -1.01 | -2.27 | 0.25 | 0.12 | -1.04 | -2.12 | 0.03 | 0.06 |

| Do you own or rent your current living? | ||||||||

| Owner | -0.05 | -0.49 | 0.39 | 0.82 | 0.05 | -0.32 | 0.43 | 0.78 |

| Rent | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Employment status | ||||||||

| Unemployed | 0.18 | -0.67 | 1.02 | 0.68 | -0.41 | -1.13 | 0.31 | 0.26 |

| Full time job | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Monthly income (SAR) | ||||||||

| 11000-15000 | 0.07 | -0.70 | 0.84 | 0.85 | 0.24 | -0.41 | 0.90 | 0.46 |

| 16000 or more | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 6000-10000 | 0.54 | -0.24 | 1.31 | 0.17 | 0.47 | -0.19 | 1.13 | 0.16 |

| Chronic diseases | ||||||||

| Cholesterol | -0.10 | -1.03 | 0.82 | 0.83 | 0.11 | -0.68 | 0.90 | 0.78 |

| Diabetes | -0.22 | -1.06 | 0.62 | 0.60 | -0.17 | -0.89 | 0.54 | 0.63 |

| Kidney/renal disease | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Neurological disease | -0.33 | -1.50 | 0.84 | 0.58 | -0.17 | -1.16 | 0.83 | 0.74 |

| Respiratory disease | -0.48 | -1.45 | 0.49 | 0.33 | -0.33 | -1.16 | 0.50 | 0.43 |

| Hypertension | -0.30 | -1.16 | 0.57 | 0.50 | 0.05 | -0.69 | 0.78 | 0.90 |

Compared to male participants, females reported significantly lower physical health scores (β = -0.67, 95%CI: -1.08 to -0.25, P = 0.002). Cancer survivors with lower monthly incomes (< 5000 SAR) also had poorer physical health compared to those earning more than SAR 10000 (β = -0.45, 95%CI: -0.82 to -0.09, P = 0.015). Living in non-owned housing (e.g., rental or with relatives) was also associated with reduced physical health scores (β = -0.51, 95%CI: -0.92 to -0.10, P = 0.013).

Psychological scores were significantly lower among participants with no formal education (β = -0.63, 95%CI: -1.02 to

Survivors reporting divorced marital status showed significantly lower social domain scores compared to married individuals (β = -0.73, 95%CI: -1.21 to -0.25, P = 0.004). In contrast, those employed in professional occupations demonstrated higher social scores than unemployed individuals (β = 0.56, 95%CI: 0.17-0.96, P = 0.005).

Environment domain scores were lower among participants living in shared accommodations or dependent housing (β = -0.61, 95%CI: -1.03 to -0.19, P = 0.004). Lower income (< 5000 SAR) was again associated with poorer environment quality (β = -0.53, 95%CI: -0.94 to -0.12, P = 0.012). In contrast, having higher educational attainment predicted better environment scores (β = 0.42, 95%CI: 0.09-0.75, P = 0.017).

Gender, education, income, marital status, and housing status were independently associated with multiple domains of QoL. Notably, socioeconomic disadvantages (low income, no home ownership) and social vulnerability (being widowed or divorced) were associated with significantly lower scores in the physical, psychological, and environmental well-being domains. These findings highlight the multifaceted needs of cancer survivors and suggest that demographic and social determinants are strongly tied to QoL outcomes beyond the cancer experience itself.

This study provides a comprehensive assessment of QoL outcomes among Saudi cancer survivors using the WHOQOL-BREF instrument, revealing important associations between demographic, socioeconomic, and clinical characteristics and domain-level well-being. The findings offer timely insights into survivorship within the Saudi healthcare context and reinforce the necessity of embedding psychosocial support and equity-based interventions into routine post-cancer care. Consistent with previous global research, our study found that survivors reported the highest mean score in the social relationships domain (3.56), followed by environment (3.39), physical health (3.05), and psychological well-being (3.05)[27,28]. These findings suggest that while social support networks in Saudi Arabia may remain intact during survivorship, psychological and physical health represent areas of vulnerability. This is particularly salient in younger survivors aged 26-30 years who reported the lowest mean scores across domains. These results align with the international literature, showing that younger cancer survivors often experience greater psychological distress, possibly due to disruptions in education, employment, and family life[29,30]. Living in rural areas was independently associated with lower scores in all domains, particularly psychological and social well-being. This urban-rural disparity highlights a critical access gap in supportive oncology services outside metropolitan centers. Given the centralized nature of cancer care in Saudi Arabia, rural patients may lack adequate follow-up, mental health services, or community rehabilitation programs, contributing to prolonged distress post-treatment. This underscores the need for geographically distributed survivorship services, including community-based support and telehealth models.

Socioeconomic status (SES), as measured by monthly income and housing status, was a strong predictor of QoL outcomes. Survivors with lower incomes (< 5000 SAR/month) and those living in rented or shared accommodation had significantly lower physical and environmental domain scores. These findings suggest that material deprivation persists as a barrier to well-being, even within a publicly funded healthcare system. Financial toxicity after cancer treatment—including indirect costs such as job loss, transportation, and long-term care needs—has been documented in middle- and high-income countries and appears to be a relevant issue in Saudi Arabia as well[31]. Educational attainment also showed a positive relationship with QoL outcomes, particularly in the environmental domain. Higher education may confer increased health literacy, self-efficacy, and access to informational resources that improve survivorship navigation. In contrast, widowed and divorced survivors reported poorer psychological and social scores, highlighting the importance of spousal and familial support in emotional adjustment. Gender differences were also observed. Although not statistically significant in all domains, female survivors consistently reported lower physical and psychological scores compared to males. These differences may reflect gendered experiences of illness in Saudi society, where female patients may encounter additional barriers to accessing mental health services or experience greater caregiving burdens[32].

Collectively, these findings emphasize the importance of viewing cancer survivorship not only as a biomedical milestone but also as a socially situated experience shaped by gender, geography, income, and education. While Saudi Arabia’s health reforms under Vision 2030 have prioritized expanding access and integrating non-communicable disease care, there remains a need to explicitly incorporate survivorship into cancer control strategies. QoL measurement should become a routine component of follow-up care, and psycho-oncology services should be scaled up to reach underserved groups.

This study has several limitations. First, the use of a convenience sample from a single university hospital in Jeddah limits generalizability to the broader Saudi survivor population, especially those in remote or less well-resourced areas. Second, the cross-sectional design precludes causal inference or examination of longitudinal QoL trajectories over time. Third, some covariates, such as cancer stage, treatment modality, and time since diagnosis, were not captured and may confound the associations observed. Fourth, while self-administered surveys reduce interviewer influence, face-to-face recruitment in a clinical setting may still have led to underreporting of psychosocial distress. Finally, the relatively small sample size limited the precision of regression estimates and may have reduced the statistical power to detect significant effects for some predictors. Nevertheless, the rigorous data collection process, domain-specific modeling, and use of robust regression methods to address assumption violations strengthen the internal validity of the findings.

In summary, this study sheds light on the multifactorial nature of QoL outcomes among Saudi cancer survivors. SES, living environment, and marital status emerged as key determinants of well-being. Integrating these insights into survivorship planning can inform the development of targeted interventions to reduce disparities and improve overall survivor support in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

Thanks to the participants who agreed to be part of this research. The authors declare that financial support was received for the research and publication of this article. The authors, therefore, acknowledge with thanks WAQF and the Deanship of Scientific Research (DSR) for technical and financial support.

| 1. | Wagle NS, Nogueira L, Devasia TP, Mariotto AB, Yabroff KR, Islami F, Jemal A, Alteri R, Ganz PA, Siegel RL. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2025. CA Cancer J Clin. 2025;75:308-340. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 59.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Nolazco JI, Chang SL. The role of health-related quality of life in improving cancer outcomes. J Clin Transl Res. 2023;9:110-114. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Ali HT, Helal A, Ismail SM, Hamdi NM, Mohamed NL, Essa AM, Mohammed M; QOL Collaborator Group, Ebada MA. Exploring the Quality of Life of University Students in Egypt: A Cross-Sectional Survey Using the World Health Organization Quality of Life-BREF (WHOQOL-BREF) Assessment. Am J Health Promot. 2025;39:263-273. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kangwanrattanakul K. Mapping of the World Health Organization Quality of Life Brief (WHOQOL-BREF) to the EQ-5D-5L in the General Thai Population. Pharmacoecon Open. 2023;7:139-148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Alharthy A, Shubair MM, Al-Khateeb BF, Alnaim L, Aljohani E, Alenazi NK, Alghamdi MA, Angawi K, Alsayer RM, Alhawiti NM, El-Metwally A. Predictors of Colon Cancer Screening Among the Saudi Population at Primary Healthcare Settings in Riyadh. Curr Oncol. 2025;32:243. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Mani ZA, Goniewicz K. Transforming Healthcare in Saudi Arabia: A Comprehensive Evaluation of Vision 2030’s Impact. Sustain. 2024;16:3277. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 7. | Alkhudair N, Alshamrani M, Samarkandi H, Almodaheem H, Alabdulkarim H, Alsaqaaby M, Alnajjar F, Alhashem H, Bakkar M, Bazarbashi S, Alnahedh M, Alfraih F, Alawagi M, Al-Jedai A. Cancer Management in Saudi Arabia: Recommendations by the Saudi Oncology HeAlth Economics ExpeRt GrouP (SHARP). Saudi Pharm J. 2021;29:115-120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Siddiqui AA, Amin J, Alshammary F, Afroze E, Shaikh S, Rathore HA, Khan R. Burden of Cancer in the Arab World. In: Laher I, editor. Handbook of Healthcare in the Arab World. Cham: Springer, 2021. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 9. | Ramadan M, Bajunaid RM, Kazim S, Alhusseini N, Al-Shareef A, ALSaleh NM. The Burden Cancer-Related Deaths Attributable to High Body Mass Index in a Gulf Cooperation Council: Results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. J Epidemiol Glob Health. 2024;14:379-397. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74:229-263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5690] [Cited by in RCA: 12374] [Article Influence: 6187.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (6)] |

| 11. | Abu-Helalah M, Mustafa H, Alshraideh H, Alsuhail AI, A Almousily O, Al-Abdallah R, Al Shehri A, Al Qarni AA, Al Bukhari W. Quality of Life and Psychological Wellbeing of Breast Cancer Survivors in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2022;23:2291-2297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Aljawadi MH, Alkhudair N, Alrasheed M, Alsuhaibani AS, Alotaibi BJ, Almuqbil M, Alhammad AM, Arafah A, AlGahtani FH, Rehman MU. Understanding the Quality of Life Among Patients With Cancer in Saudi Arabia: Insights From a Cross-Sectional Study. Cancer Control. 2024;31:10732748241263013. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Almutairi H, Aboshaiqah A, Alzahrani M, Almutairi AF, Salam M. The Lived Experience of Adult Cancer Survivors After Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation: A Qualitative Study From Saudi Arabia. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2025;19:279-293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Alotaibi DM. The impact of culture and social norms on female employment in Arab countries in general and Saudi Arabia in particular: based on quantitative and qualitative evidence. Doc Thesis, University of East Anglia. 2023. Available from: https://ueaeprints.uea.ac.uk/id/eprint/95877. |

| 15. | Ngo NTN, Nguyen HT, Nguyen PTL, Vo TTT, Phung TL, Pham AG, Vo TV, Dang MTN, Nguyen Le Bao T, Duong KNC. Health-related quality of life in breast cancer patients in low-and-middle-income countries in Asia: a systematic review. Front Glob Womens Health. 2023;4:1180383. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Al-Karni MAT, Omar MTA, Al-Dhwayan NM, Ajarim D, Idreess MJN, Gwada RFM. Factors Associated with Health-Related Quality of Life Among Breast Cancer Survivors in Saudi Arabia: Cross-Sectional Study. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2024;25:951-961. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 17. | Alshahrani AS. Quality of Life among Colostomy Patients in Najran, Saudi Arabia. King Khalid Univ J Health Sci. 2024;9:29-38. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 18. | Alhomoud S, Al-Othman S, Al-Madouj A, Homsi MA, AlSaleh K, Balaraj K, Alajmi A, Basu P, Al-Zahrani A. Progress and remaining challenges for cancer control in the Gulf Cooperation Council. Lancet Oncol. 2022;23:e493-e501. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Albeshr AG, Alanazi AM, Aleraij MM, Alanazi ST, Alhabdan YA. A Review on Healthcare System in Saudi Arabia: Opportunities and Obstacles. In: Hussaini J, editor. Disease and Health: Research Developments Vol. 9. London: BP International, 2025: 28-35. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 20. | Ogbolu Y, Dudding R, Fiori K, North-Kabore J, Parke D, Plum RA, Shin S, Rowthorn V. Global Learning for Health Equity: A Literature Review. Ann Glob Health. 2022;88:89. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Baeza-Delgado C, Cerdá Alberich L, Carot-Sierra JM, Veiga-Canuto D, Martínez de Las Heras B, Raza B, Martí-Bonmatí L. A practical solution to estimate the sample size required for clinical prediction models generated from observational research on data. Eur Radiol Exp. 2022;6:22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kim S. World Health Organization Quality of Life (WHOQOL) Assessment. In: Maggino F, editor. Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research. Cham: Springer, 2023. |

| 23. | Yermakhanov B, Zorba E, Turkmen M, Akman O. The Validity and Reliability Study of WHO Quality of Life Scale Short Form (WHOQOL-Bref) in Kazakh Language. Sport Mont. 2021;19:69-74. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Al-Qerem W, Al-Maayah B, Ling J. Developing and validating the Arabic version of the Diabetes Quality of Life questionnaire. East Mediterr Health J. 2021;27:414-426. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Shayan NA, Eser E, Neyazi A, Eser S. Reliability and validity of the Dari version of the World Health Organization quality of life (WHOQOL-BREF) questionnaire in Afghanistan. Turk J Public Health. 2021;19:263-273. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 26. | Khan DM, Ali M, Ahmad Z, Manzoor S, Hussain S. A New Efficient Redescending M-Estimator for Robust Fitting of Linear Regression Models in the Presence of Outliers. Math Probl Eng. 2021;2021:1-11. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 27. | Belau MH, Jung L, Maurer T, Obi N, Behrens S, Seibold P, Becher H, Chang-Claude J. Social relationships and their impact on health-related quality of life in a long-term breast cancer survivor cohort. Cancer. 2024;130:3210-3218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Demuro M, Bratzu E, Lorrai S, Preti A. Quality of Life in Palliative Care: A Systematic Meta-Review of Reviews and Meta-Analyses. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2024;20:e17450179183857. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Meernik C, Kirchhoff AC, Anderson C, Edwards TP, Deal AM, Baggett CD, Kushi LH, Chao CR, Nichols HB. Material and psychological financial hardship related to employment disruption among female adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. Cancer. 2021;127:137-148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Altherr A, Bolliger C, Kaufmann M, Dyntar D, Scheinemann K, Michel G, Mader L, Roser K. Education, Employment, and Financial Outcomes in Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer Survivors-A Systematic Review. Curr Oncol. 2023;30:8720-8762. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Ehsan AN, Wu CA, Minasian A, Singh T, Bass M, Pace L, Ibbotson GC, Bempong-Ahun N, Pusic A, Scott JW, Mekary RA, Ranganathan K. Financial Toxicity Among Patients With Breast Cancer Worldwide: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6:e2255388. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 38.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Aljhani S, Aldughayim S, Alsweed Z, Alherbish S, Alhumaid F, Alismail R, Alkhalaf S, AlBahouth I. Barriers to Treatment of Mental Disorders in Saudi Arabia. Psychiatr Q. 2025;96:75-89. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/