Published online Nov 24, 2025. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v16.i11.110687

Revised: July 8, 2025

Accepted: October 9, 2025

Published online: November 24, 2025

Processing time: 158 Days and 1.6 Hours

Outcomes of early breast cancer in African women are currently not well defined.

To analyze survival outcomes and prognostic factors in Moroccan women with operable breast cancer treated with multimodal therapies.

We retrospectively analyzed the data of a large cohort of 400 patients diagnosed with nonmetastatic breast cancer who completed surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy at the National Institute of Oncology in Rabat, from January 2001 to December 2003.

The mean age at diagnosis was 45 years (range: 22-91 years). Surgery was performed in all cases: Mastectomy in 86% and breast-conserving surgery in 14%. Most tumors (> 87%) were classified as pathologic T2 stage or higher, and axillary lymph nodes were involved in 75.5% of cases. Ninety-five percent of patients completed six cycles of adjuvant chemotherapy, and all received radiotherapy. At a median follow-up of 74.5 months, the 5-year overall survival (OS) was 82.1% [95% confidence interval (CI): 78.1-86.3], and the 5-year disease-free survival was 78.1% (95%CI: 73.8-82.6). In univariate analysis, negative nodal status [pN- vs pN+, hazard ratio (HR) = 0.34, 95%CI: 0.16-0.75; P = 0.007] and lower American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) stage (I-II vs III, HR = 0.29, 95%CI: 0.16-0.52; P < 0.001) were significantly associated with better OS. In multivariate analysis, AJCC stage I-II vs stage III remained the strongest predictor of improved OS (HR = 0.32, 95%CI: 0.15-0.67; P = 0.002), followed by treatment with anthracyclines vs cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, fluorouracil (CMF; HR = 0.58, 95%CI: 0.35-0.94; P = 0.027).

Moroccan women with early breast cancer exhibited more aggressive disease compared to women in high-income countries. AJCC stage III was the strongest predictor of poorer OS, followed by chemotherapy regimen (CMF vs anthracycline). A multimodal treatment approach, including surgery, systemic therapy, and radiotherapy, is essential to improve breast cancer outcomes.

Core Tip: In this retrospective study, we investigated demographics, tumor characteristics, and outcomes in women with early breast cancer in a cohort of 400 Moroccan women. At a median follow-up of 74.5 months, the 5-year overall survival (OS) was 82.1%, and the 5-year disease-free survival was estimated at 78.1%. In univariate analysis, patients with negative pathologic nodal stage and American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) stage I-II had better OS than those with pN+ and stage III disease, respectively. In multivariate analysis, AJCC stage I-II (vs stage III) showed the strongest association with improved OS, followed by treatment with anthracyclines (vs cyclophosphamide, methotrexate and fluorouracil).

- Citation: Ismaili N, Guessous F, El Majjaoui S. Clinical outcomes of early-stage breast cancer in Morocco: A cohort of 400 women. World J Clin Oncol 2025; 16(11): 110687

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-4333/full/v16/i11/110687.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5306/wjco.v16.i11.110687

In Africa, breast cancer is the most common cancer and the leading cause of cancer-related-death in women[1,2]. For various reasons, national cancer registries are still not fully established[3]. However, according to the GLOBOCAN (2022), the estimated incidence ranges from 26.7/100000 in Middle Africa to 53.2/100000 in Northern Africa[2]. This is lower than in high-income countries, where the incidence varies from 89/100000 in France to 100/100000 in Australia and New Zealand[1]. In North African countries, breast cancer predominantly affects younger women and is often diagnosed at advanced stages[4-8]. It exhibits more aggressive behavior and poorer outcomes compared to high-income countries[2,4,5]. Data on mortality and survival patterns remain limited, primarily coming from regional studies[1,2]. Five-year breast cancer survival rates range from 59.8% in Algeria to 76.6% in Libya[2,7]. Limited access to oncology services, including pathology, surgery, radiotherapy, and systemic therapy such as chemotherapy, endocrine therapies, and targeted therapies, contributes to such poor outcomes[7].

In Morocco, breast cancer is also a major health concern, accounting for more than 35% of all cancers in women and more than 20% of all cancers across both sexes[3]. According to the greater Casablanca registry, the standardized incidence rate of breast cancer is estimated at 39.9/100000 women[3]. Consistent with other African countries, Moroccan patients frequently present with advanced-stage disease due to late diagnosis, and limited access to breast cancer awareness and screening[5]. Stages III and IV account for more than 30% of cases[5,9,10], and the proportion of breast cancer in women under 35-40 years is relatively high(6.7%-17%)[11,12].

Several challenges in breast cancer management have been successfully addressed in Morocco. The country now has over 30 multidisciplinary cancer centers, both public and private, thanks to the effort of the Ministry of Health and non-profit organizations and foundations. These centers provide widespread access to pathology services, including immunohistochemistry (Herceptest, hormone receptor status, KI67 index) and molecular biology techniques (fluorescence in situ hybridization, chromogenic in situ hybridization, next-generation sequencing, molecular signatures), as well as modern oncology treatments such as taxane-chemotherapy, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-targeted therapies, and advanced radiotherapy techniques[5,12]. Additionally, the Moroccan Ministry of Health has supported oncology capacity-building in several African countries (Gabon, Mauritania, Mali, Burkina Faso), helping train specialists and upgrade radiotherapy and cancer treatment facilities. However, data on long-term survival for these women, particularly in the context of multimodal treatment, remain limited.

In this retrospective study, we examined the clinical, pathological, and treatment characteristics, as well as outcomes, overall survival (OS), disease-free survival (DFS), and locoregional relapse-free survival (LRRFS) of women with early breast cancer treated at the National Institute of Oncology in Rabat, Morocco. We also explored the influence of prognostic factors, including age, histology, tumor grade, hormone receptor status, nodal status, T stage, American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) stage, and chemotherapy, on patient survival.

The medical record of women diagnosed and treated for operable breast cancer at the National Institute of Oncology in Rabat between January 2001 to December 2003 were analyzed.

A total of 400 women with pathologically confirmed, non-metastatic breast cancer [pathologic tumor stages (pT1-T4)/pathologic lymph node stages (pN0-3)], who underwent complete excision of the pT, either by mastectomy or breast conserving therapy, and received adjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy, were included. Only patients who completed their preplanned treatments, including surgery, chemotherapy and radiotherapy, were considered. Diagnostic investigations for staging included mammography, chest radiograph, and abdominal ultrasound for all patients, while bone scans were performed in 61 patients.

Patients with metastatic breast cancer or those who did not complete surgery, adjuvant chemotherapy, and/or radiotherapy, were excluded.

Patient medical record, including demographic data, clinical characteristics, disease stages, nodal status, histological and immunohistochemical findings, and outcomes, were retrospectively reviewed. Radiological, pathological, and surgical reports were examined to determine disease stage according to tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) staging for breast tumors (8th edition). The AJCC 8th edition stage was assigned based on pathological assessment of the pT and dissected lymph nodes (pN). Treatment reports, including surgery, systemic therapy, and radiotherapy, were retrieved from the electronic medical record. Dates of recurrence, and if applicable, death were also considered.

OS was defined as the time from pathological diagnosis (fine-needle aspiration, biopsy, or surgery) to death from any cause or last follow-up. DFS was defined as the time from pathological diagnosis to the first relapse, death, or last follow-up. LRRFS was defined as the time from pathological diagnosis to locoregional relapse, death or last follow-up.

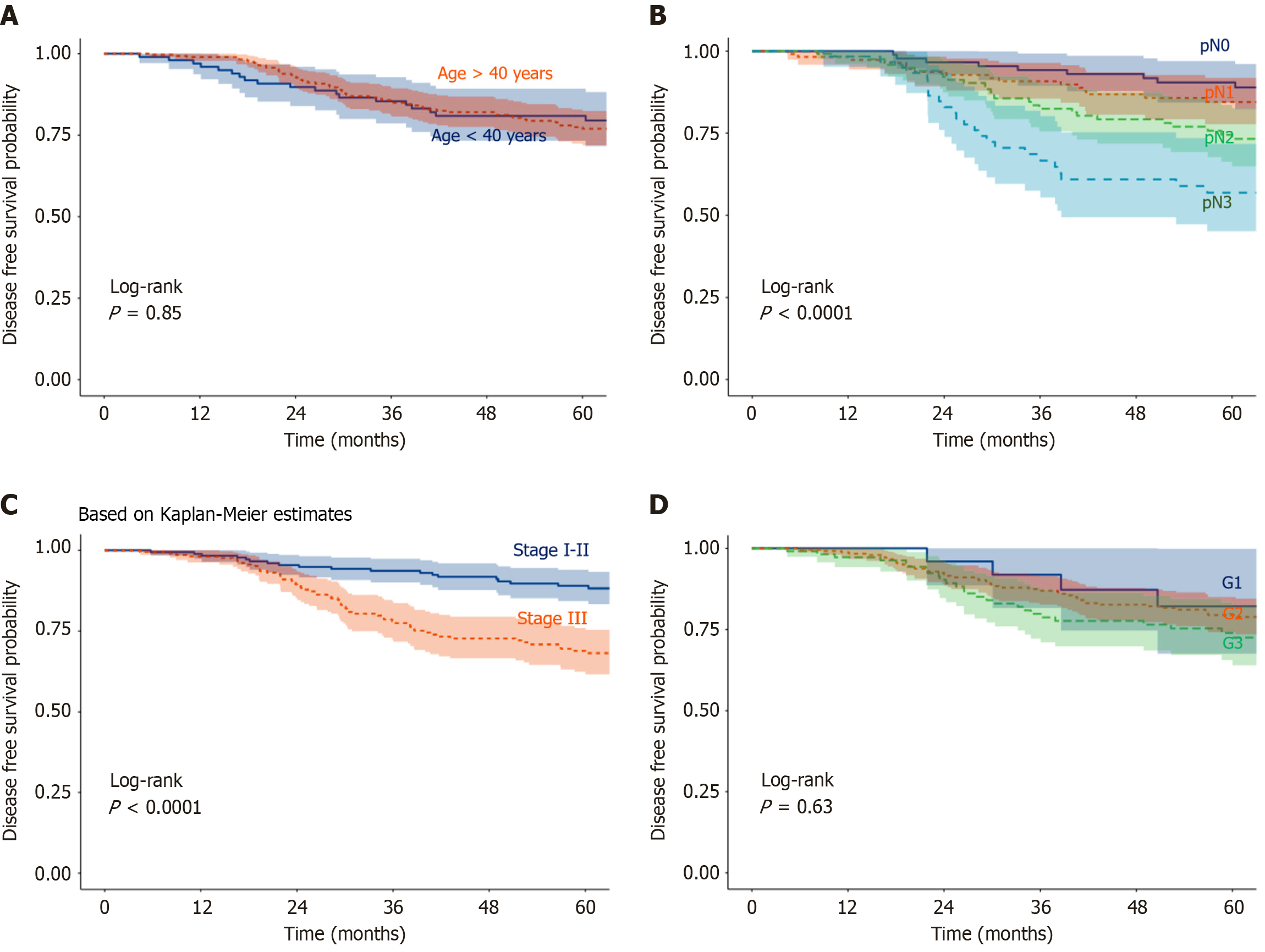

Survival curves for OS, DFS, and LRRFS were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Group differences were assessed with the log-rank test to evaluate the impact of prognostic factors (age, histology, tumor grade, lymph node involvement, T stage, AJCC stage, hormone receptor status, treatments) on OS and DFS. At the time of analysis, 112 patients (28%) were lost to follow-up and therefore censored. Statistical analyses were performed using JAMOVI statistical software.

We evaluated key prognostic factors in our cohort, including age, histological type (invasive ductal carcinoma, invasive lobular carcinoma, or other types), tumor grade [Scarf-Bloom-Richardson (SBR)], TNM stage, hormone receptor status, and treatment regimen [cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, fluorouracil (CMF) vs anthracycline-based]. These parameters are well-established predictors of breast cancer outcomes and were selected to understand the effects of multimodal treatment.

Associations between these factors and survival outcomes, OS and DFS, were assessed using univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression models. Age was categorized as < 40 years vs ≥ 40 years, pT stage as pT3-4 vs pT1-2, nodal status as pN+ vs pN-, tumor grade as 3 vs 2 vs 1, and hormone receptor status as negative vs positive. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Treatment decisions were made by the medical staff according to drug availability in Morocco. Oral consent was obtained from all patients, and the study protocol was approved by the institutional review boards of the National Institute of Oncology Cancer Center in Rabat. Ethical approval was also granted by the Ethics Committee of Mohammed VI University of Sciences and Health (UM6SS). This retrospective study complies with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Table 1 summarizes the demographic and clinical characteristics of the 400 patients. The mean age at diagnosis was 45 years (range 22-91 years). Breast cancer affected younger women (< 40 years) in 30% of cases (n = 119), with the highest incidence observed between 41 and 50 years (44%, n = 176). The majority of patients were premenopausal (n = 263).

| Characteristic | Patients (n) | % |

| Age (years) | ||

| < 40 | 119 | 30.0 |

| 40-50 | 176 | 44.0 |

| > 50 | 105 | 26.0 |

| Menopausal status | ||

| No | 263 | 66.0 |

| Yes | 137 | 34.0 |

| Tumor side | ||

| Right breast | 194 | 48.5 |

| Left breast | 205 | 51.0 |

| Bilateral | 1 | 0.5 |

| Histology | ||

| IDC | 367 | 92.0 |

| ILC | 25 | 6.0 |

| Others | 8 | 2.0 |

| Grade (SBR) | ||

| I | 27 | 6.7 |

| II | 250 | 62.5 |

| III | 112 | 28.0 |

| Missing | 11 | 2.8 |

| Hormone receptor | ||

| Positive | 398 | 73.0 |

| Negative | 100 | 25.0 |

| Missing | 2 | 0.5 |

| Tumor stage (pT) | ||

| T1 | 49 | 12.2 |

| T2 | 226 | 56.5 |

| T3 | 98 | 24.5 |

| T4 | 19 | 4.8 |

| Missing | 8 | 2.0 |

| Axillary status (pN) | ||

| N0 | 96 | 24.0 |

| N+ | 301 | 75.0 |

| N1 | 114 | 28.5 |

| N2 | 124 | 31.0 |

| N3 | 63 | 15.5 |

| Missing | 3 | 1.0 |

| AJCC stage | ||

| I | 8 | 2.0 |

| II | 161 | 40.2 |

| III | 216 | 54.0 |

| Missing | 15 | 3.8 |

The most predominant histological type was infiltrating ductal carcinoma [infiltrating carcinoma of non-specific type (NST); n = 367, 92%]. Most tumors were classified as SBR grade 2 or 3 (93.3%, n = 373). Hormone receptor status was available for 398 patients, and 73% of the tumors had hormone receptor-positive (estrogen receptor and/or progesterone receptor). Information on HER2 expression and the Ki-67 percentage was not available at the time of diagnosis.

All patients underwent surgery: Mastectomy in 86% (n = 344) and breast-conserving surgery in 14% (n = 56). Most tumors were classified as stages pT2 or higher (87.7%, n = 351). Pathological axillary lymph node involvement (pN+) was present in 75.5% of patients (n = 302). According to AJCC stage, 4.5% (n = 18) were stage I, 40% (n = 161) stage II, and 55.5% (n = 216) stage III.

Table 2 summarizes the treatment characteristics. All patients received adjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Radiotherapy was administered to the breast or chest wall in all patients; 83% (n = 333) received also radiotherapy to the supraclavicular and internal mammary chains, and 15% (n = 60) to the axilla.

| Treatment | Patients (n) | % |

| Surgery | ||

| Mastectomy | 344 | 86.0 |

| Breast-conserving surgery | 56 | 14.0 |

| Chemotherapy | ||

| Anthracycline-based regimen | 249 | 62.2 |

| CMF regimen | 151 | 37.8 |

| Radiotherapy - breast/thoracic wall | ||

| Breast | 56 | 14.0 |

| Thoracic wall | 344 | 86.0 |

| Radiotherapy - lymph nodes | ||

| Supraclavicular ± IMC | 333 | 83.2 |

| Axillary | 60 | 15.0 |

All patients underwent chemotherapy: 249 received anthracycline-based regimens [doxorubicin plus cyclophosphamide (n = 173), doxorubicin plus cyclophosphamide and fluorouracil (n = 21), epirubicin plus cyclophosphamide and fluorouracil (n = 37), or a sequential protocol combining anthracycline, cyclophosphamide, methotrexate and fluorouracil (n = 18)], whereas 151 received CMF (cyclophosphamide, methotrexate and fluorouracil). A total of 95% of the patients (n = 381) completed six cycles of chemotherapy, while 5% (n = 19) received only four cycles.

Endocrine therapy with tamoxifen was prescribed to patients with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer.

Table 3 summarizes patient outcomes in patients with early breast cancer in Morocco.

| Survival | At 1-year (95%CI) | At 3-year (95%CI) | At 5-year (95%CI) |

| OS | 99% (98%-100%) | 91.4% (88.6%-94.4%) | 82.1% (78.1%-86.3%) |

| DFS | 98.5% (97.3%-99.7%) | 85.4% (81.9%-89.1%) | 78.1% (73.8%-82.6%) |

| LRRFS | 99.7% (99.2%-100%) | 96.9% (95.1%-98.7%) | 96.5% (96.4%-98.5%) |

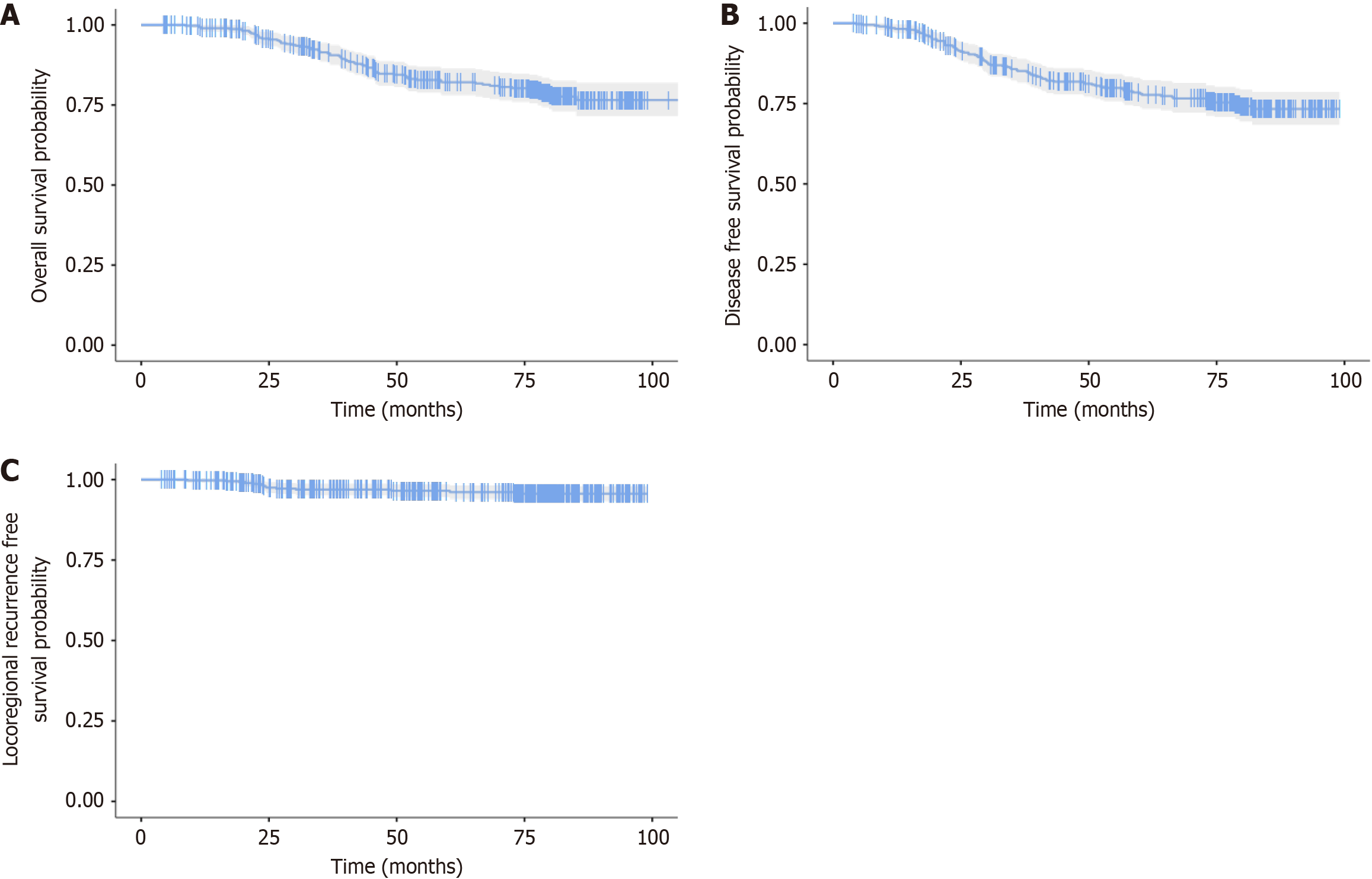

OS: At a median follow-up of 74.5 months (range 4.3-106.6), 61 deaths were reported. The 5-year OS was 82.1% [95% confidence interval (CI): 78.1-86.3; Figure 1A].

DFS: At the same median follow-up, 76 patients experienced locoregional or distant relapse. The 5-year DFS was 78.1% (95%CI: 73.8-82.6; Figure 1B).

LRRFS: During follow-up, 11 patients developed locoregional relapse (breast, contralateral breast, or regional pN). The 5-year LRRFS was 96.5% (95%CI: 94.6-98.5; Figure 1C).

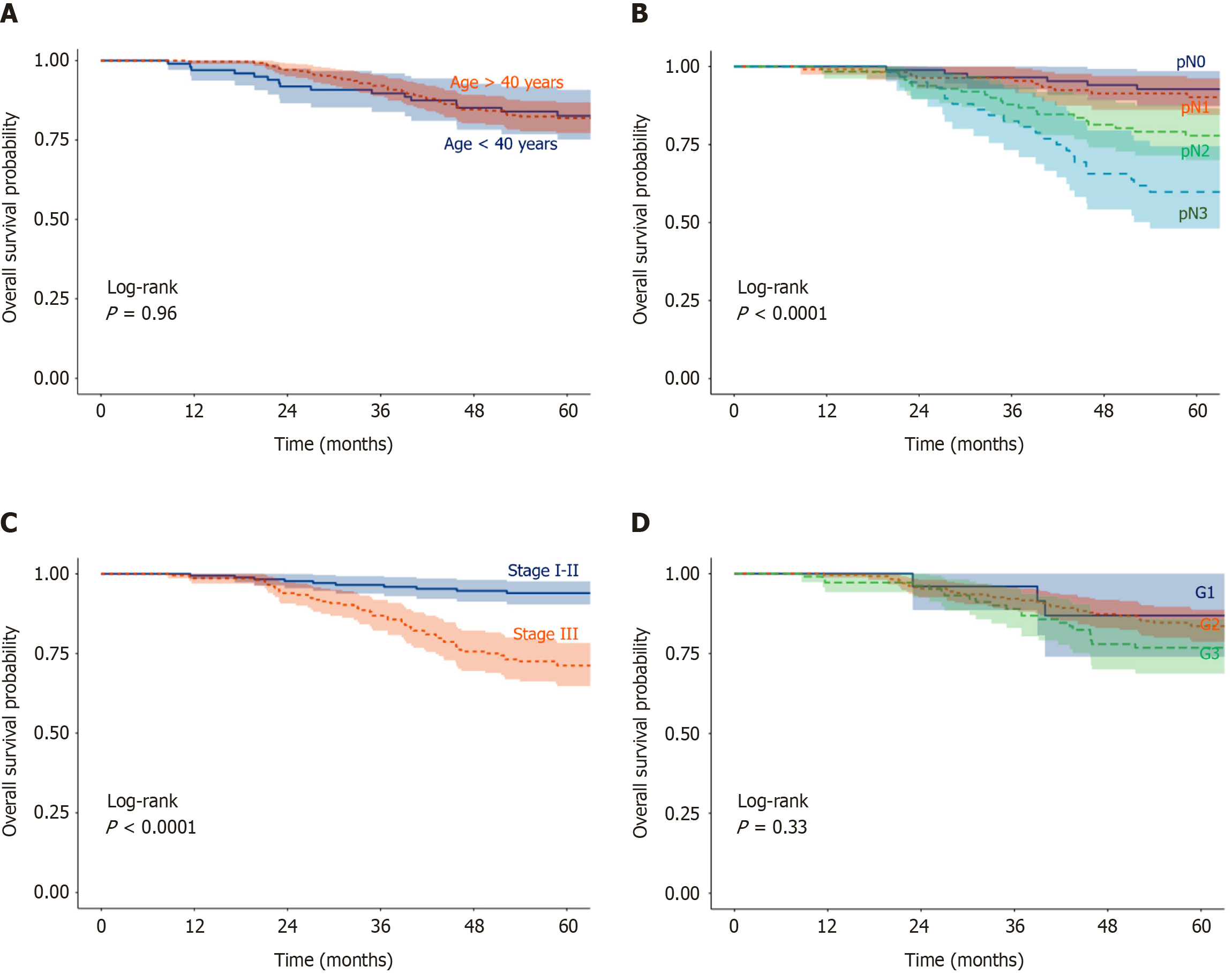

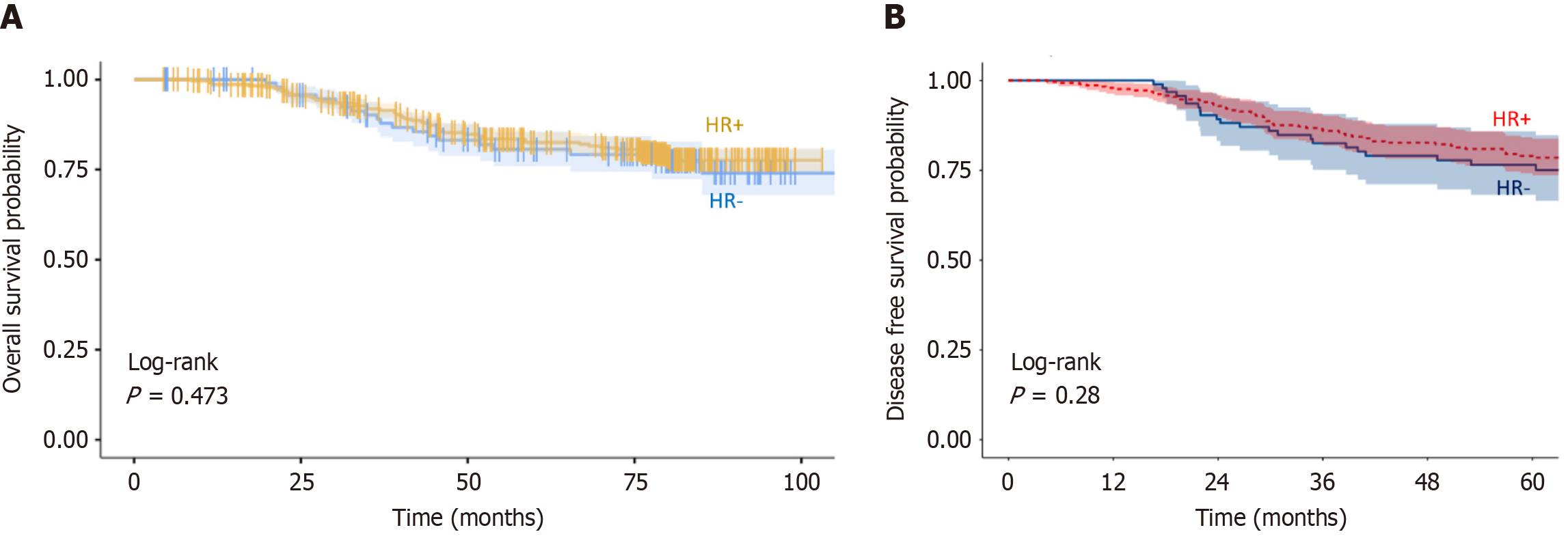

Factors influencing OS: In univariate analysis (Table 4), negative nodal status [pN- vs pN+, hazard ratio (HR) = 0.34, 95%CI: 0.16-0.75; P = 0.007] and lower AJCC stage (I-II vs III, HR = 0.29, 95%CI: 0.16-0.52; P < 0.001) were significantly associated with improved OS. Age, SBR grade, histology, and hormone receptor status showed no significant impact on OS (Figures 2 and 3A).

| Factors | Participants | Hazard ratio (univariable) | Hazard ratio (multivariable) | |

| Age (year) | ≥ 40 | 282 (75.2) | - | - |

| < 40 | 93 (24.8) | 0.96 (0.56-1.67, P = 0.897) | 1.15 (0.65-2.02, P = 0.636) | |

| Grade (SBR) | 1-2 | 268 (71.5) | - | - |

| 3 | 107 (28.5) | 1.48 (0.90-2.44, P = 0.121) | 1.44 (0.85-2.43, P = 0.171) | |

| Histology | IDC | 355 (94.7) | - | - |

| ILC | 20 (5.3) | 1.48 (0.59-3.68, P = 0.401) | 1.77 (0.69-4.54, P = 0.237) | |

| Hormone receptor | HR- | 94 (25.1) | - | - |

| HR+ | 281 (74.9) | 0.89 (0.52-1.51, P = 0.660) | 0.97 (0.56-1.67, P = 0.903) | |

| pT | pT2-3 | 111 (29.6) | - | - |

| pT1-2 | 264 (70.4) | 0.64 (0.39-1.04, P = 0.071) | 1.00 (0.59-1.72, P = 0.988) | |

| pN | pN+ | 288 (76.8) | - | - |

| pN0 | 87 (23.2) | 0.34 (0.16-0.75, P = 0.007) | 0.70 (0.27-1.82, P = 0.469) | |

| Stage | 3 | 208 (55.5) | - | - |

| 1-2 | 167 (44.5) | 0.29 (0.16-0.52, P < 0.001) | 0.32 (0.15-0.67, P = 0.002) | |

| Treatment | CMF | 142 (37.9) | - | - |

| Anthra | 233 (62.1) | 0.67 (0.42-1.08, P = 0.098) | 0.58 (0.35-0.94, P = 0.027) | |

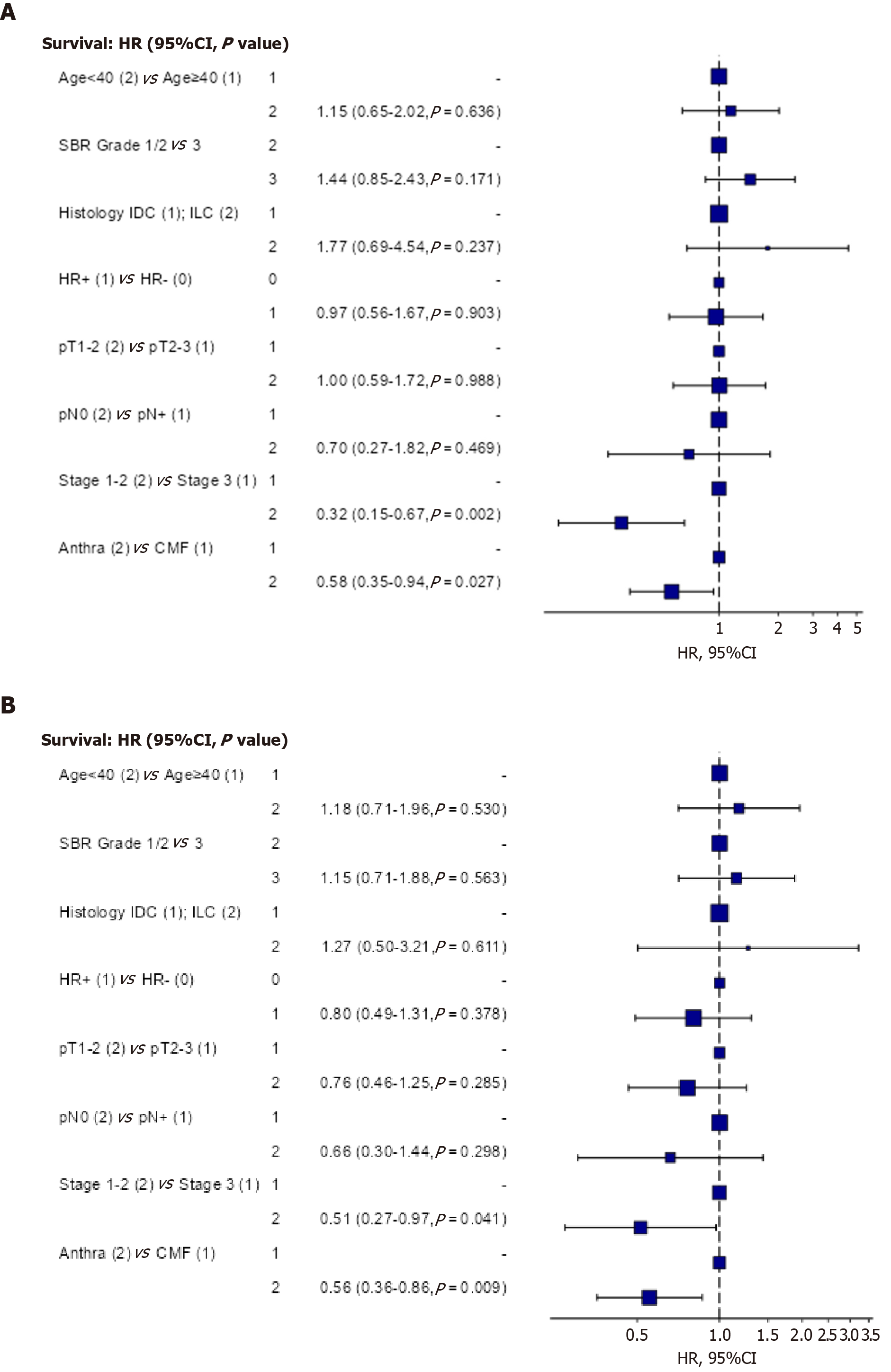

In multivariate analysis (Table 4), AJCC stage remained the strongest prognostic factor, with stages I-II showing better OS compared to stage III (HR = 0.32, 95%CI: 0.15-0.67; P = 0.002). Treatment with anthracycline-based regimens was also independently associated with improved OS compared to CMF (HR = 0.58, 95%CI: 0.35-0.94; P = 0.027) (Figure 4A).

Factors influencing DFS: In univariate analysis (Table 5), lower pT stage (pT1-2 vs pT3-4, HR = 0.56, 95%CI: 0.36-0.88; P = 0.012), negative nodal status (pN- vs pN+, HR = 0.46, 95%CI: 0.24-0.86; P = 0.016), lower AJCC stage (I-II vs III, HR = 0.41, 95%CI: 0.25-0.67; P < 0.001), and anthracycline-based treatment (vs CMF, HR = 0.63, 95%CI: 0.41-0.98; P = 0.040) were significantly associated with DFS. Age, SBR grade, histology, and hormone receptor status had no significant effect on DFS (Figures 3B and 5).

| Factors | Participants | Hazard ratio (univariable) | Hazard ratio (multivariable) | |

| Age (year) | ≥ 40 | 282 (75.2) | - | - |

| < 40 | 93 (24.8) | 1.01 (0.62-1.66, P = 0.964) | 1.18 (0.71-1.96, P = 0.530) | |

| Grade (SBR) | 1-2 | 268 (71.5) | - | - |

| 3 | 107 (28.5) | 1.28 (0.80-2.04, P = 0.301) | 1.15 (0.71-1.88, P = 0.563) | |

| Histology | IDC | 355 (94.7) | - | - |

| ILC | 20 (5.3) | 1.25 (0.50-3.08, P = 0.632) | 1.27 (0.50-3.21, P = 0.611) | |

| Hormone receptor | HR- | 94 (25.1) | - | - |

| HR+ | 281 (74.9) | 0.76 (0.48-1.22, P = 0.262) | 0.80 (0.49-1.31, P = 0.378) | |

| pT | pT2-3 | 111 (29.6) | - | - |

| pT1-2 | 264 (70.4) | 0.56 (0.36-0.88, P = 0.012) | 0.76 (0.46-1.25, P = 0.285) | |

| pN | pN+ | 288 (76.8) | - | - |

| pN0 | 87 (23.2) | 0.46 (0.24-0.86, P = 0.016) | 0.66 (0.30-1.44, P = 0.298) | |

| Stage | Stage 3 | 208 (55.5) | - | - |

| Stage 1-2 | 167 (44.5) | 0.41 (0.25-0.67, P < 0.001) | 0.51 (0.27-0.97, P = 0.041) | |

| Treatment | CMF | 142 (37.9) | - | - |

| Anthra | 233 (62.1) | 0.63 (0.41-0.98, P = 0.040) | 0.56 (0.36-0.86, P = 0.009) | |

In multivariate analysis (Table 5), AJCC stage (I-II vs III) and anthracycline-based treatment (vs CMF) remained independently associated with better DFS (Figure 4B).

In Morocco, based on our investigation, we conclude that breast cancer management has evolved since the early 2000s, thanks to the efforts of Ministry of Health and oncology specialists, surgeons, and pathologists. The survival rate at 5-year exceeded 80%, even in the absence of targeted therapies and modern endocrine therapies at that time.

However, the disease showed more aggressive clinical, pathological, and molecular characteristics compared to those observed in high-income countries. The proportion of breast cancer in young women (< 40 years) was high (30% in our investigation), compared to Iceland, where it was less than 5.6%[5,12-14]. In addition, the highest incidence was observed between 40 and 49 years, vs 75 and 79 years in United States; and the median age at diagnosis was lower and ranging between 44 and 50 years, compared to 50 and 63 years in high-income countries[1,3,5,12,15]. In Morocco, the disease is diagnosed at advanced stages (III and IV) in more than 30% of cases[5,9,10,12,15]. In our investigation, we reported stage III disease in more than 50% of the patients. Furthermore, the size of the tumor at diagnosis exceeded 2 cm in the vast majority of cases (75% in our study), and pN was frequently involved in our study as well as in other Moroccan studies, in 65%-78% of cases[4,5,9,10,15]. These results are aligned with those reported in Tunisia and Bahrain, respectively (tumor size > 2 cm in 70%)[16,17]. In fact, in Africa, women with breast cancer were commonly diagnosed at younger ages and advanced stages compared to women in high-income countries. There is also a higher incidence of aggressive subtypes[8]. However, in Europe, the diagnosis is mainly made at early stages, and tumor size at diagnosis is < 2 cm in 70% of cases[15].

Infiltrating ductal carcinoma of NST (World Health Organization classification) was the most reported subtype in our study, reported in more than 80% of cases, consistent with others published studies[5,9,10]. The vast majority of tumors were classified as grade 2 or 3 (85%-93%)[5,10,12]. In our study, only 6.7% of the patients were classified as grade 1 tumor, whereas in Europe, 30% of patients were diagnosed with grade 1 tumors[15].

The prevalence of breast cancer subtypes was analyzed in two reports from Fez (n = 366) and Eastern Morocco (n = 2260)[9,10]. Among patients diagnosed with infiltrating breast carcinoma, immunohistochemical studies showed that 53.6%-61.1% of tumors were luminal A, 16.1%-16.4% luminal B, 8.6%-12.6% HER2-overexpressing, and 14.2%-12.6% basal-like[9,10]. In a recent large investigation from National Institute of Oncology, nearly 29% of the tumors were HER2-overexpressing and 13.9% were triple-negative[5]. In our study, 73% of tumors expressed hormone receptors; however, HER2 and Ki-67 status, which are important for breast cancer management, were not determined due to unavailability. Overall, Moroccan patient characteristics were consistent with those reported in non-African American population, in which the prevalence of breast cancer molecular subtype showed a high proportion of luminal A (54%), followed by luminal B (16%-18%), HER2 (9%), and basal-like (16%)[18]. Moroccan patients with the luminal A subclass had a better prognosis, whereas those with basal like subclass had a poorer prognosis. Patients with luminal B and HER2-positive subtypes, had intermediate prognosis[9]. According to a study conducted at Rabat, triple-negative breast cancer accounted for 16.5% of all breast cancers, with a 5-year survival rate of 76% in this aggressive subgroup[19].

Treatment modalities for breast cancer in Morocco showed to be more aggressive[12]. Standard mastectomy was the treatment of choice in more than 80% of the cases in our study. In addition, due to the more aggressive clinical and pathological breast tumor characteristics (advanced stage, node-positive disease, younger age), adjuvant and neoadjuvant chemotherapy were frequently used[6]. These treatments, however, were associated with more side effects and severe complications.

Access to innovative therapies and radiotherapy is limited in many African countries, leading to poor clinical outcomes[7]. In our investigation, all patients received surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy. In fact, in Morocco, breast cancer management has shown remarkable progress since the early 2000s, thanks to the effort of the Ministry of Health and major non-profit foundations, such as Mohammed VI Foundation of Sciences and Health and Lalla Salma Foundation. These initiatives have led to greater adoption of international treatment guidelines[20], broader availability of pathology services including immunohistochemistry and molecular biology, increased access to modern radiotherapy machines, and the introduction of modern chemotherapy and targeted therapies such as trastuzumab and pertuzumab in HER2-positive disease.

In our study, the estimated disease-free and OS rates at 5-year were 78.1% and 82.1%, respectively. According to more recent investigation from National Institute of Oncology, 5-year DFS in the era of modern treatments was estimated at 80%[5]. The main prognostic factors influencing survival in early breast cancer were young age, advanced stage, node-positive status, high grade, hormone receptor-negative status, HER2-positive status, triple-negative breast cancer subtype, and poor molecular signatures[20]. To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first published investigation analyzing prognostic factors in women with early breast cancer in Morocco. The main prognostic factors identified were AJCC stage (stage III vs stage I-II), nodal stage (pN+ vs pN-), tumor size (pT3-4 vs pT1-2), and treatment type (CMF vs anthracycline).

The strengths of our study include the large population of 400 patients, the high percentage of complete data from oncology and radiotherapy reports, and the long-term follow-up, which allowed us to report meaningful results. However, the major limitations are its retrospective nature and the lack of some important information, such as HER2 status and Ki-67 status (Table 1).

Our study confirms that breast cancer is the most common and deadliest cancer among women in Morocco. Due to late diagnosis, mastectomy was performed in more than 80% of cases. Nevertheless, clinical outcomes in patients who completed multimodal treatments were comparable to those reported in high-income countries. For the majority of patients diagnosed at advanced stage III (> 50% of cases), prognosis remains poor. These findings highlight the urgent need for a nationwide early detection and screening program to improve clinical outcomes. Future research should focus on strategies to raise awareness, facilitate early diagnosis, and optimize treatment access to reduce the overall burden of breast cancer in Morocco[21].

| 1. | Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74:229-263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5690] [Cited by in RCA: 13018] [Article Influence: 6509.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (8)] |

| 2. | Allemani C, Weir HK, Carreira H, Harewood R, Spika D, Wang XS, Bannon F, Ahn JV, Johnson CJ, Bonaventure A, Marcos-Gragera R, Stiller C, Azevedo e Silva G, Chen WQ, Ogunbiyi OJ, Rachet B, Soeberg MJ, You H, Matsuda T, Bielska-Lasota M, Storm H, Tucker TC, Coleman MP; CONCORD Working Group. Global surveillance of cancer survival 1995-2009: analysis of individual data for 25,676,887 patients from 279 population-based registries in 67 countries (CONCORD-2). Lancet. 2015;385:977-1010. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1738] [Cited by in RCA: 1782] [Article Influence: 162.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Bouchbika Z, Haddad H, Benchakroun N, Eddakaoui H, Kotbi S, Megrini A, Bourezgui H, Sahraoui S, Corbex M, Harif M, Benider A. Cancer incidence in Morocco: report from Casablanca registry 2005-2007. Pan Afr Med J. 2013;16:31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Corbex M, Bouzbid S, Boffetta P. Features of breast cancer in developing countries, examples from North-Africa. Eur J Cancer. 2014;50:1808-1818. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Mrabti H, Sauvaget C, Benider A, Bendahhou K, Selmouni F, Muwonge R, Alaoui L, Lucas E, Chami Y, Villain P, Abousselham L, Carvalho AL, Bennani M, Errihani H, Sankaranarayanan R, Bekkali R, Basu P. Patterns of care of breast cancer patients in Morocco - A study of variations in patient profile, tumour characteristics and standard of care over a decade. Breast. 2021;59:193-202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Sharma R, Aashima, Nanda M, Fronterre C, Sewagudde P, Ssentongo AE, Yenney K, Arhin ND, Oh J, Amponsah-Manu F, Ssentongo P. Mapping Cancer in Africa: A Comprehensive and Comparable Characterization of 34 Cancer Types Using Estimates From GLOBOCAN 2020. Front Public Health. 2022;10:839835. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 30.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Vanderpuye V, Grover S, Hammad N, PoojaPrabhakar, Simonds H, Olopade F, Stefan DC. An update on the management of breast cancer in Africa. Infect Agent Cancer. 2017;12:13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Anyanwu SN. Temporal trends in breast cancer presentation in the third world. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2008;27:17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Bennis S, Abbass F, Akasbi Y, Znati K, Joutei KA, El Mesbahi O, Amarti A. Prevalence of molecular subtypes and prognosis of invasive breast cancer in north-east of Morocco: retrospective study. BMC Res Notes. 2012;5:436. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Elidrissi Errahhali M, Elidrissi Errahhali M, Ouarzane M, El Harroudi T, Afqir S, Bellaoui M. First report on molecular breast cancer subtypes and their clinico-pathological characteristics in Eastern Morocco: series of 2260 cases. BMC Womens Health. 2017;17:3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Abahssain H, Lalya I, El M'rabet FZ, Ismaili N, Razine R, Tazi MA, M'rabti H, El Mesbahi O, Benjaafar N, Abouqal R, Errihani H. Breast cancer in moroccan young women: a retrospective study. BMC Res Notes. 2010;3:286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ismaili N, Elmajjaoui S, Lalya I, Boulaamane L, Belbaraka R, Abahssain H, Aassab R, Benjaafar N, El Guddari Bel K, El Mesbahi O, Sbitti Y, Ismaili M, Errihani H. Anthracycline and concurrent radiotherapy as adjuvant treatment of operable breast cancer: a retrospective cohort study in a single institution. BMC Res Notes. 2010;3:247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Chung M, Chang HR, Bland KI, Wanebo HJ. Younger women with breast carcinoma have a poorer prognosis than older women. Cancer. 1996;77:97-103. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 14. | Howlader N, Chen VW, Ries LA, Loch MM, Lee R, DeSantis C, Lin CC, Ruhl J, Cronin KA. Overview of breast cancer collaborative stage data items--their definitions, quality, usage, and clinical implications: a review of SEER data for 2004-2010. Cancer. 2014;120 Suppl 23:3771-3780. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Blamey RW, Hornmark-Stenstam B, Ball G, Blichert-Toft M, Cataliotti L, Fourquet A, Gee J, Holli K, Jakesz R, Kerin M, Mansel R, Nicholson R, Pienkowski T, Pinder S, Sundquist M, van de Vijver M, Ellis I. ONCOPOOL - a European database for 16,944 cases of breast cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:56-71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Fakhro AE, Fateha BE, al-Asheeri N, al-Ekri SA. Breast cancer: patient characteristics and survival analysis at Salmaniya medical complex, Bahrain. East Mediterr Health J. 1999;5:430-439. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Missaoui N, Jaidene L, Abdelkrim SB, Abdelkader AB, Beizig N, Yaacoub LB, Yaacoubi MT, Hmissa S. Breast cancer in Tunisia: clinical and pathological findings. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2011;12:169-172. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Carey LA, Perou CM, Livasy CA, Dressler LG, Cowan D, Conway K, Karaca G, Troester MA, Tse CK, Edmiston S, Deming SL, Geradts J, Cheang MC, Nielsen TO, Moorman PG, Earp HS, Millikan RC. Race, breast cancer subtypes, and survival in the Carolina Breast Cancer Study. JAMA. 2006;295:2492-2502. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2859] [Cited by in RCA: 2801] [Article Influence: 140.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Rais G, Raissouni S, Aitelhaj M, Rais F, Naciri S, Khoyaali S, Abahssain H, Bensouda Y, Khannoussi B, Mrabti H, Errihani H. Triple negative breast cancer in Moroccan women: clinicopathological and therapeutic study at the National Institute of Oncology. BMC Womens Health. 2012;12:35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Loibl S, André F, Bachelot T, Barrios CH, Bergh J, Burstein HJ, Cardoso MJ, Carey LA, Dawood S, Del Mastro L, Denkert C, Fallenberg EM, Francis PA, Gamal-Eldin H, Gelmon K, Geyer CE, Gnant M, Guarneri V, Gupta S, Kim SB, Krug D, Martin M, Meattini I, Morrow M, Janni W, Paluch-Shimon S, Partridge A, Poortmans P, Pusztai L, Regan MM, Sparano J, Spanic T, Swain S, Tjulandin S, Toi M, Trapani D, Tutt A, Xu B, Curigliano G, Harbeck N; ESMO Guidelines Committee. Early breast cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2024;35:159-182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 552] [Article Influence: 276.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Selmouni F, Bendahhou K, Sauvaget C, Abahssain H, Lucas E, Muwonge R, Mimouni H, Ismaili R, Bidar S, Benkaddour FZ, Abousselham L, Chami Khazraji Y, Belakhel L, Basu P. Impact of clinical breast examination-based screening program on care pathway, stage at diagnosis, nature of treatment, and overall survival among breast cancer patients in Morocco. Cancer. 2024;130:3353-3363. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/