Published online Sep 24, 2024. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v15.i9.1239

Revised: May 26, 2024

Accepted: June 12, 2024

Published online: September 24, 2024

Processing time: 129 Days and 16.2 Hours

Bladder neuroendocrine tumors are few and exhibit a high degree of aggressiveness. The bladder is characterized by four distinct forms of neuroendocrine tumors. Among them, large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma is the least prevalent, but has the highest level of aggressiveness. The 5-year survival rate for large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the bladder is exceedingly poor. To date, only a few dozen cases have been reported.

Here, we report the case of a 65-year-old man with large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the bladder. The patient presented to the Department of Urology at our hospital due to the presence of painless hematuria without any identifiable etiology. During hospitalization, abdominal computed tomography revealed the presence of an irregular mass on the right anterior wall of the bladder. A cystoscopic non-radical resection of the bladder lesion was performed. The postoperative pathological examination revealed large-cell neuroendocrine bladder cancer. Previous reports on cases of large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma cases were retrieved from PubMed, and the present paper discusses the currently recognized best diagnostic and treatment options for large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma based on the latest research progress.

Large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the bladder is an uncommon malignancy with a highly unfavorable prognosis. Despite ongoing efforts to prolong patient survival through multidisciplinary therapy, the prognosis remains unfavorable. Large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma continues to be a subject of uncertainty.

Core Tip: This report presents a case of large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the bladder. This tumor is extremely rare and has been poorly reported in the medical literature, highlighting the need for early diagnosis and multimodal treatment. The report emphasizes that, although large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma is clinically rare, it is extremely aggressive. Most patients have a very poor prognosis, although spontaneous remission is possible. There is thus considerable uncertainty surrounding this tumor.

- Citation: Zhou Y, Yang L. Large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the bladder: A case report. World J Clin Oncol 2024; 15(9): 1239-1244

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-4333/full/v15/i9/1239.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5306/wjco.v15.i9.1239

Neuroendocrine (NE) tumors of the bladder are rare, accounting for < 1% of bladder malignancies. Most NE tumors of the bladder are small-cell neuroendocrine carcinomas (SCNECs). Large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (LCNEC) is much rarer, difficult to diagnose, prone to distant metastasis, and has low survival rates, requiring early diagnosis and intensive combined therapy. In this article, we report a case of LCNEC of the bladder with the aim of improving the understanding thereof through the reporting of the case and review of the relevant literature.

A 65-year-old man presented to the Urology Clinic with a 3-month duration of painless hematuria without any identifiable etiology.

The patient had experienced macroscopic hematuria without obvious cause for 3 months. The blood was bright red in color, without blood clots. The hematuria had occurred several times during the course of the disease. He had no other symptoms, such as frequent urination, urgency, pain, difficulty urinating, or back pain.

The patient’s medical history was devoid of any conditions, including the absence of other diseases such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, heart disease, tuberculosis, or other tumors.

The patient had no risk factors other than a prolonged history of smoking and alcohol usage. The patient reported no family history of any disease or cancerous growth.

A physical examination showed that the kidneys were symmetrical, with no bulging, no tenderness to percussion, no tenderness to bilateral costovertebral points, and no vascular murmurs. There was no bulge in the lower abdomen, no tenderness over the pubic bone, and no tympanic sound on percussion. The vital signs of the patient were recorded as follows: body temperature of 36.7 °C; arterial blood pressure of 133/92 mmHg; SpO2 level of 98%; pulse rate of 74 beats per min; and respiration rate of 18 breaths per min. In general, the findings of the physical examination were within normal limits.

Laboratory analyses revealed an absolute lymphocyte value of 1.0 × 109/L, a neutrophil percentage of 77.0%, lymphocyte percentage of 16.1%, eosinophil percentage of 0.3%, albumin level of 39.1 g/L, urine erythrocyte level of 236.0/UL, urine leukocyte level of 69.0/UL, and a weakly positive result for tissue polypeptide antigen. The remainder of the laboratory test results were within normal limits.

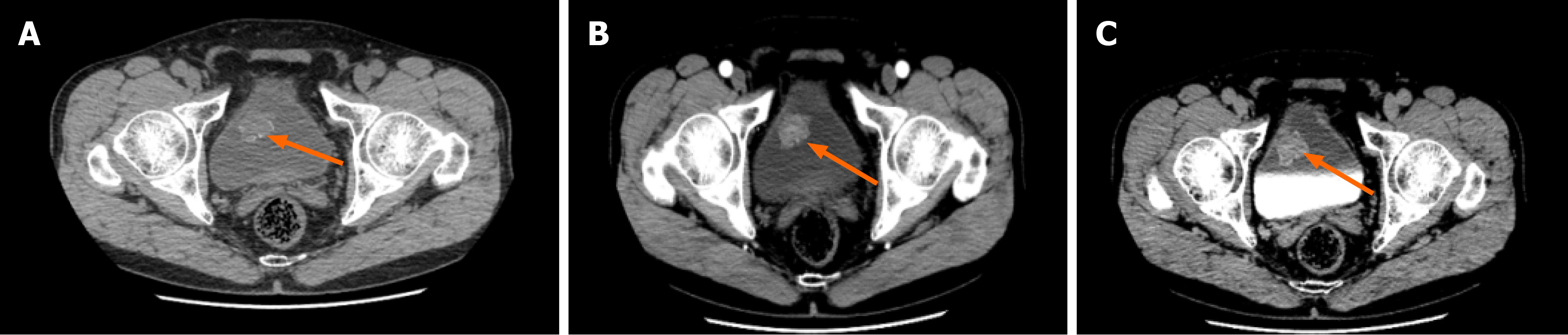

Ultrasound showed atypical echoes in the bladder and a substantial blood supply. The results of the non-contrast computed tomography of the whole abdomen and contrast-enhanced computed tomography of the urinary system revealed the presence of an irregular mass on the right anterior wall of the bladder (Figure 1). The mass had a size of approximately 30 mm × 29 mm and was observed to project into the lumen. Additionally, the lesion exhibited multiple speckles of hyperdense shadows, which became more pronounced after enhancement.

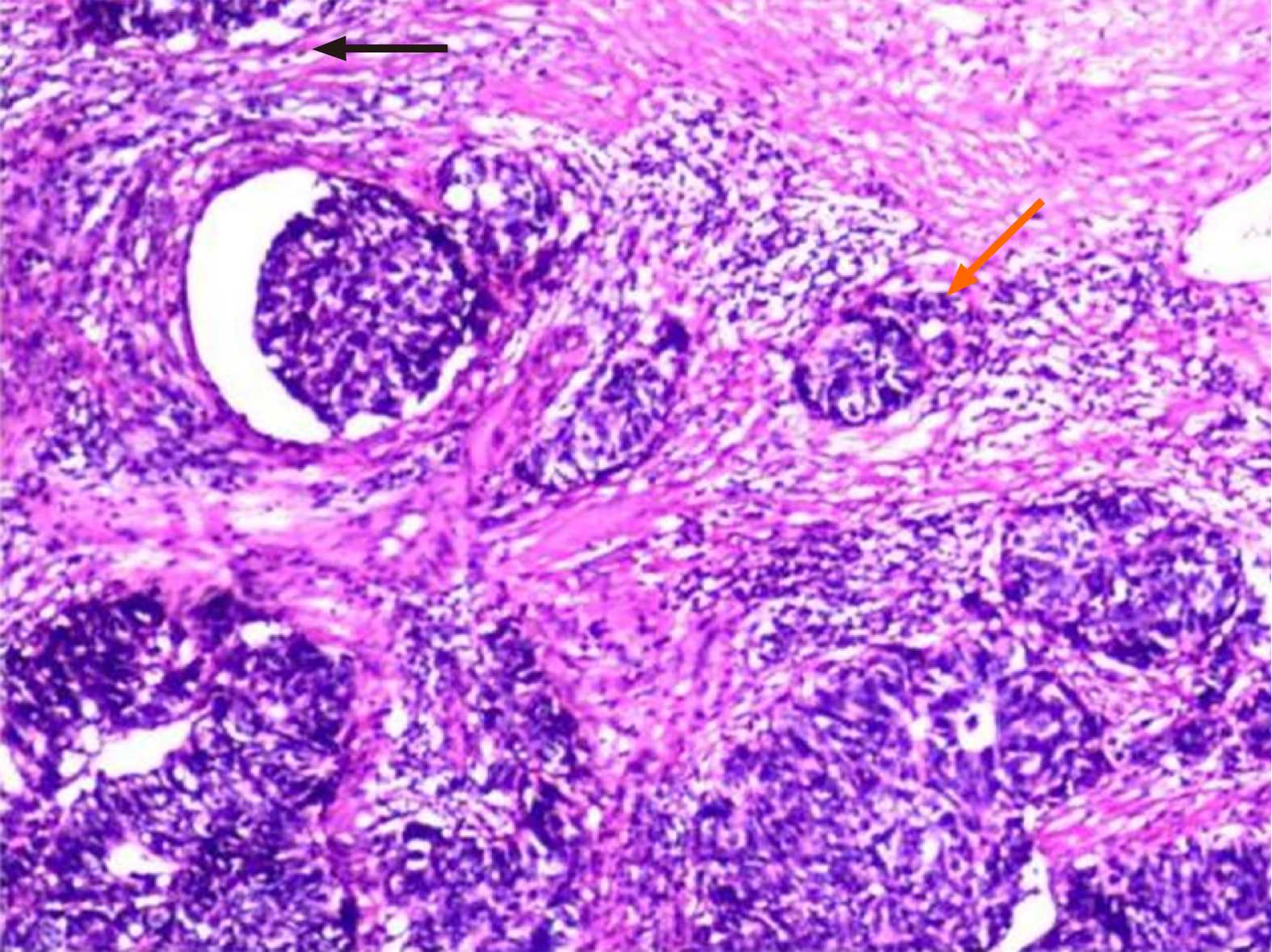

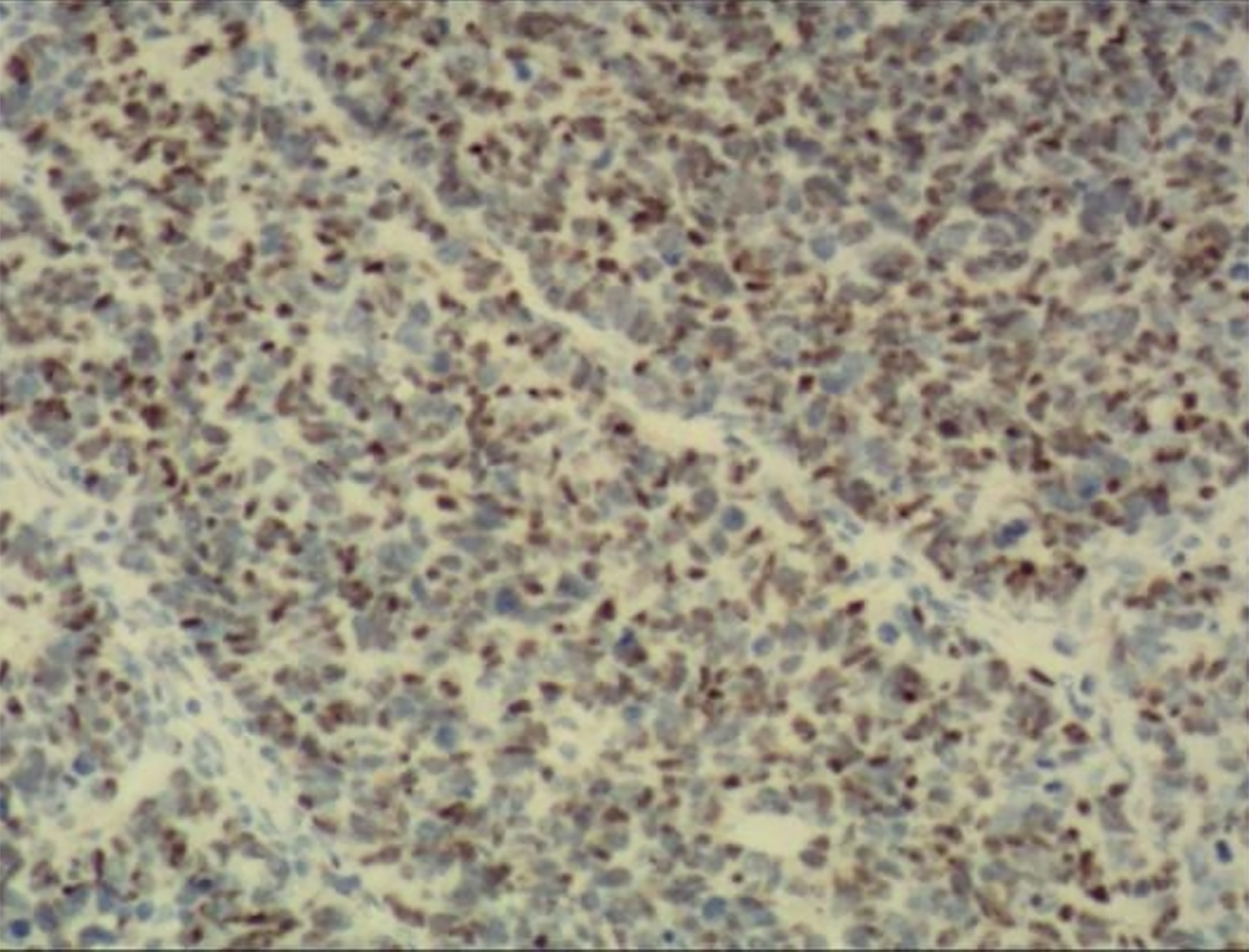

A histological investigation conducted after the surgery demonstrated the presence of large-cell neuroendocrine bladder cancer (Figure 2), characterized by the invasion of the muscular layer of the mucosa. The immunohistochemistry and histology results, as depicted in Figure 3, indicated the presence of SMA (+), GATA3 (+), HER-2 (+), CD56 (+), SYN (+), CGA (+), INSM1 (+), P53 (+), and Ki67 (+, 60%).

Based on the patient’s history, laboratory test results, imaging, and histopathology, the patient was diagnosed with LCNEC of the bladder.

We first performed cystoscopic non-radical resection of the bladder lesion, and the chemotherapy regimen of etoposide + cisplatin was used after clarification based on postoperative pathological and immunohistochemical results. As the patient had undergone diagnostic resection with limited surgical scope without lymph node dissection, and considering the high rate of local recurrence of the tumor, separate cyst infusion chemotherapy was used.

The patient received a thoracic and abdominal non-contrast computed tomography 10 days post-surgery. The results revealed the presence of scattered nodules in both lungs, which were classified as low-risk nodules. No apparent abnormalities were observed. Due to the specific pathological type of the bladder tumor, the patient was transferred to the Oncology Department for follow-up chemotherapy. After discharge, the patient received regular chemotherapy and follow-up. No obvious metastasis or recurrence was found during the 7-month follow-up after surgery.

NE tumors predominantly manifest in the pulmonary and gastrointestinal systems, although occurrences in the bladder are few[1]. Based on the categorization provided by the World Health Organization in 2016, primary NE tumors of the bladder can be categorized into four distinct subtypes: SCNEC, LCNEC, well-differentiated NE tumors, and highly indolent paragangliomas. LCNEC is considered the least common NE tumor affecting the bladder. The disease has a high susceptibility to recurrence and metastasis, a significantly low survival rate[2], and a scarcity of related research data.

The potential misdiagnosis of bladder LCNEC may have occurred due to its scarcity and limited clinical understanding[3,4]. This phenomenon was initially documented in 1986 by Abenoza et al[5]. Bladder LCNEC is frequently observed in males between the ages of 50 years and 80 years. It has been linked to persistent inflammatory irritation, bladder stones, and cigarette smoking[6]. Additionally, it has been shown that the lateral wall of the bladder is the most frequently affected site for LCNEC[4,7]. Most individuals with LCNEC experience fast development and quickly acquire widespread systemic metastases[8]. The liver, lung, groin, bone, adrenal gland, and pelvis are frequently affected by metastases[9,10]. Patients with LCNEC of the bladder typically exhibit intermittent, painless, full-thickness, grossly macroscopic hematuria as their initial symptom. In some cases, dysuria may occur due to diffuse carcinoma in situ or tumor myometrial infiltration, resulting in urinary frequency, urgency, and painful urination[11]. Additionally, there have been cases where patients did not exhibit any apparent visible blood in the urine or any urinary symptoms, and the diagnosis of LCNEC of the bladder was only confirmed due to the presence of oliguria[6]. The patient exhibited painless evident blood in the urine, had a prolonged smoking habit, and the tumor was situated in the right bladder wall. The postoperative chest computed tomography revealed dispersed nodules in both lungs, which were classified as low-risk nodules.

The etiology of bladder LCNEC remains incompletely elucidated. According to most researchers, bladder LCNEC is thought to originate from multifunctional stem cells present in the bladder mucosa. The coexistence of bladder LCNEC with other cancer forms, such as urothelial carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, lymphoepithelial carcinoma, and carcinosarcoma, may be attributed to this phenomenon[4,6,12-15].

The gold standard to diagnose LCNEC is histopathology. Ancillary tests have a suggestive nature and do not possess qualitative values. 111In-DTPA-octreotide scintigraphy can be employed with conventional imaging to identify cancer cells and metastasis, owing to the abnormal secretory capability of NE tumors[4]. Positron emission tomography/computed tomography (CT) imaging with 18F-Fluoro-2-deoxyglucose has demonstrated efficacy in treating lymph node metastases.

Currently, there is a lack of widely acknowledged agreement or standard for the management of LCNEC in academic settings. The current chemotherapy regimens for LCNEC are based on the treatment experience of lung NE[4,12]. Neoadjuvant or adjuvant etoposide and platinum medicines are the primary options for chemotherapeutic treatments[4]. It has been suggested that LCNEC has greater sensitivity to cisplatin, gemcitabine, or etoposide compared to typical uroepithelial carcinoma[16]. In this case, the lesion filling the bladder was initially subjected to plasma electrocution, then followed by a combination of etoposide and cisplatin. We used plasma electrosurgery to treat bladder-occupying lesions in this patient. The treatment combination of etoposide + cisplatin was implemented following a definitive diagnosis of LCNEC, as determined by surgical pathology and immunohistochemistry findings. The individual had a diagnostic resection procedure characterized by a restricted surgical scope and the absence of lymph node dissection. Given the elevated incidence of local tumor recurrence, an adjunctive bladder infusion chemotherapy was administered. The biological and clinicopathological characteristics of bladder LCNEC are mostly based on a limited number of research and case reports, owing to its rarity. LCNEC is still characterized by a multitude of uncertainties, hence constraining the progress and assessment of its treatment protocols. Nevertheless, the effectiveness of multimodal therapy has been demonstrated[3,6-8,12]. The necessity of employing a mix of chemotherapy, radiation, and surgery for treatment is indisputable. Studies have demonstrated that administering neoadjuvant chemotherapy and then performing surgical resection can enhance patient survival rates for restricted LCNEC[4,7,12,13,15,17].

Nevertheless, the prognosis for individuals who experience metastases is often unfavorable. Immune checkpoint inhibitors have been proposed to be highly effective in treating LCNEC. Examining specific genetic changes in patients with LCNEC might potentially serve as a novel treatment approach. Currently, ongoing trials are being conducted to evaluate the efficacy of nivolumab, ipilimumab, and cabozantinib in the treatment of uncommon genitourinary cancers[3].

Regarding prognosis, the survival of patients is consistently linked only to tumor-node-metastasis staging[18]. The cancer infiltrated the muscularis propria at stage T2 in this case. Following the surgical excision, a regimen of cyclic chemotherapy was delivered, and subsequent frequent follow-up assessments were carried out. At 7 months postoperatively, there was no notable recurrence or tumor spread, indicating a favorable prognosis. This finding provides evidence for the efficacy of our diagnostic and treatment regimens in the context of this patient. Nevertheless, given the very intrusive characteristics of LCNEC, it is imperative to undergo cystoscopy every 3 months, and imaging studies of the urinary system hold comparable significance. Currently, there is a lack of a universally accepted follow-up practice for individuals diagnosed with LCNEC. According to a study, the prevalence of brain metastases in SCNEC is estimated to be approximately 11%[19]. Hence, it is crucial to do brain magnetic resonance imaging monitoring in individuals diagnosed with LCNEC.

In this case, the patient was not treated with adjuvant chemotherapy before surgery, and the diagnosis was confirmed by postoperative pathological biopsy. According to the examination results, the patient’s stage was T2a, and the surgical method used was tumor resection only without lymph node dissection. We thus chose to perform bladder perfusion therapy after surgery, and the patient was discharged from the hospital with regular chemotherapy. The patient was followed up for 7 months after surgery and no obvious abnormality was found.

Bladder LCNEC is an uncommon malignant neoplasm with a highly unfavorable prognosis. Although there are ongoing efforts to enhance patient survival through multidisciplinary therapy, the prognosis remains unfavorable. LCNEC continues to be a subject of uncertainty. A patient with LCNEC at T4a experienced a local recurrence following surgery, as described. Following a year of declining further systemic therapy, the positron emission tomography-CT follow-up revealed a state of full spontaneous remission[20]. Hence, further investigation is required to comprehend this condition.

We express our gratitude to Lin Yang for his valuable contributions to this manuscript. His expertise and insights have significantly enhanced the quality of our work. We would also like to express our gratitude to our patient and his family for allowing us to publish this case report.

| 1. | Olivieri V, Fortunati V, Bellei L, Massarelli M, Ruggiero G, Abate D, Serra N, Griffa D, Forte F, Corongiu E. Primary small-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the bladder: Case report and literature review. Arch Ital Urol Androl. 2020;92. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Halabi R, Abdessater M, Boustany J, Kanbar A, Akl H, El Khoury J, El Hachem C, El Khoury R. Large Cell Neuroendocrine Carcinoma of the Bladder with Adenocarcinomatous Component. Case Rep Urol. 2020;2020:8827646. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Lopedote P, Yosef A, Kozyreva O. A Case of Bladder Large Cell Carcinoma with Review of the Literature. Case Rep Oncol. 2022;15:326-337. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Sanguedolce F, Calò B, Chirico M, Tortorella S, Carrieri G, Cormio L. Urinary Tract Large Cell Neuroendocrine Carcinoma: Diagnostic, Prognostic and Therapeutic Issues. Anticancer Res. 2020;40:2439-2447. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Abenoza P, Manivel C, Sibley RK. Adenocarcinoma with neuroendocrine differentiation of the urinary bladder. Clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural study. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1986;110:1062-1066. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Akdeniz E, Bakirtas M, Bolat MS, Akdeniz S, Özer I. Pure large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the bladder without urological symptoms. Pan Afr Med J. 2018;30:134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Niu Q, Lu Y, Xu S, Shi Q, Guo B, Guo Z, Huang T, Wu Y, Yu J. Clinicopathological characteristics and survival outcomes of bladder neuroendocrine carcinomas: a population-based study. Cancer Manag Res. 2018;10:4479-4489. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Quek ML, Nichols PW, Yamzon J, Daneshmand S, Miranda G, Cai J, Groshen S, Stein JP, Skinner DG. Radical cystectomy for primary neuroendocrine tumors of the bladder: the university of southern california experience. J Urol. 2005;174:93-96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Akamatsu S, Kanamaru S, Ishihara M, Sano T, Soeda A, Hashimoto K. Primary large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the urinary bladder. Int J Urol. 2008;15:1080-1083. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lee KH, Ryu SB, Lee MC, Park CS, Juhng SW, Choi C. Primary large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the urinary bladder. Pathol Int. 2006;56:688-693. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Witjes JA, Bruins HM, Cathomas R, Compérat EM, Cowan NC, Gakis G, Hernández V, Linares Espinós E, Lorch A, Neuzillet Y, Rouanne M, Thalmann GN, Veskimäe E, Ribal MJ, van der Heijden AG. European Association of Urology Guidelines on Muscle-invasive and Metastatic Bladder Cancer: Summary of the 2020 Guidelines. Eur Urol. 2021;79:82-104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 517] [Cited by in RCA: 1379] [Article Influence: 229.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Wang G, Yuan R, Zhou C, Guo C, Villamil C, Hayes M, Eigl BJ, Black P. Urinary Large Cell Neuroendocrine Carcinoma: A Clinicopathologic Analysis of 22 Cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2021;45:1399-1408. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Radović N, Turner R, Bacalja J. Primary "Pure" Large Cell Neuroendocrine Carcinoma of the Urinary Bladder: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2015;13:e375-e377. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Oshiro H, Gomi K, Nagahama K, Nagashima Y, Kanazawa M, Kato J, Hatano T, Inayama Y. Urinary cytologic features of primary large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the urinary bladder: a case report. Acta Cytol. 2010;54:303-310. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Coelho HM, Pereira BA, Caetano PA. Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the urinary bladder: case report and review. Curr Urol. 2013;7:155-159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Batista da Costa J, Gibb EA, Bivalacqua TJ, Liu Y, Oo HZ, Miyamoto DT, Alshalalfa M, Davicioni E, Wright J, Dall'Era MA, Douglas J, Boormans JL, Van der Heijden MS, Wu CL, van Rhijn BWG, Gupta S, Grivas P, Mouw KW, Murugan P, Fazli L, Ra S, Konety BR, Seiler R, Daneshmand S, Mian OY, Efstathiou JA, Lotan Y, Black PC. Molecular Characterization of Neuroendocrine-like Bladder Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25:3908-3920. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Dowd K, Rotenberry C, Russell D, Wachtel M, de Riese W. Rare Occurrence of a Poorly Differentiated Neuroendocrine Tumor of the Bladder. Case Rep Med. 2017;2017:4812453. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Alijo Serrano F, Sánchez-Mora N, Angel Arranz J, Hernández C, Alvarez-Fernández E. Large cell and small cell neuroendocrine bladder carcinoma: immunohistochemical and outcome study in a single institution. Am J Clin Pathol. 2007;128:733-739. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Bhatt VR, Loberiza FR Jr, Tandra P, Krishnamurthy J, Shrestha R, Wang J. Risk factors, therapy and survival outcomes of small cell and large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of urinary bladder. Rare Tumors. 2014;6:5043. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Chong V, Zwi J, Hanning F, Lim R, Williams A, Cadwallader J. A case of large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the bladder with prolonged spontaneous remission. J Surg Case Rep. 2017;2017:rjw179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/