Published online Mar 5, 2026. doi: 10.4292/wjgpt.v17.i1.112825

Revised: September 8, 2025

Accepted: November 26, 2025

Published online: March 5, 2026

Processing time: 188 Days and 18.2 Hours

Risk of post colonoscopy colorectal cancer is related to adenoma miss rate (AMR) during colonoscopy. Artificial intelligence (AI) and Endocuff Vision are tools both used to increase adenoma detection rate (ADR).

To assess whether the combination of AI and Endocuff vision, compared to using AI alone, increases the ADR.

This is a single-center randomized, tandem colonoscopy trial. Patients with a Bos

Eighty-five patients were included in total (male: 51; mean age: 63 ± 8 years old). In 39 patients, the initial colonoscopy was performed using AI alone, while in 45 patients, it was carried out with a combination of AI and Endocuff. Colonoscopies without Endocuff were associated with a numerically higher ADR (19/39, 48.7% vs 14/45, 31.1%, P = 0.107) and an increased number of polyps detected per procedure (1.7 ± 2.5 vs 1.2 ± 1.4, P = 0.272). During tandem colonoscopy, an additional 0.4 ± 0.8 polyps per examination (polyp miss rate = 0.08 ± 0.15), along with 0.3 ± 0.7 adenomas (AMR = 0.10 ± 0.25), were identified. Adding Endocuff to AI during tandem colonoscopy did not provide any benefit in AMR or polyp miss rate when compared to initial AI combined with Endocuff-assisted endoscopy followed by tandem AI-only procedures (0.11 ± 0.24 vs 0.92 ± 0.27, P = 0.727; and 0.10 ± 0.15 vs 0.07 ± 0.14, P = 0.415, respe

Adding Endocuff to AI-assisted colonoscopy, according to our results, does not lead to increased adenoma dete

Core Tip: Adenoma detection rate (ADR) is associated with a decreased risk of developing interval colorectal cancer, whereas the adenoma miss rate during colonoscopy is related to the risk of post-colonoscopy colorectal cancer. Artificial in

- Citation: Stasinos I, Voulgaris T, Kouimtsidis IA, Zantza SA, Leventaki FA, Theodosopoulos TA, Vlachogiannakos J, Apostolopoulos PA, Karamanolis GP. Impact of Endocuff addition to real-time computer-aided detection of colorectal neoplasia in a randomised tandem colonoscopy trial. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther 2026; 17(1): 112825

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2150-5349/full/v17/i1/112825.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4292/wjgpt.v17.i1.112825

Colonoscopy is recognized as the leading screening tool for colorectal cancer (CRC)[1,2]. It offers the highest combined sensitivity and specificity for detecting CRC, and it also allows for the identification and removal of precancerous lesions such as adenomas, thereby playing an important preventive role[1,2]. The adenoma detection rate (ADR) - the proportion of screening colonoscopies in which an adenoma is found - is the most widely used, studied, and validated metric for assessing the quality of screening colonoscopy, as a higher ADR correlates with a reduced risk of developing interval CRC[3]. A more rigorous measure of screening effectiveness is the adenoma miss rate (AMR), which is directly associated with the incidence of interval cancers[4].

However, colonoscopy is still not a perfect screening modality, as even experienced endoscopists may miss up to one in four adenomas[5]. Over the years, numerous strategies have been implemented to improve the ADR, including modi

Incomplete visualization of blind spots - most notably the regions obscured by colonic folds - remains a major con

With the incorporation of AI into endoscopy, computer-aided detection (CADe) systems have emerged, using deep learning models to facilitate real-time recognition of lesions during colonoscopy. The United States Food and Drug Ad

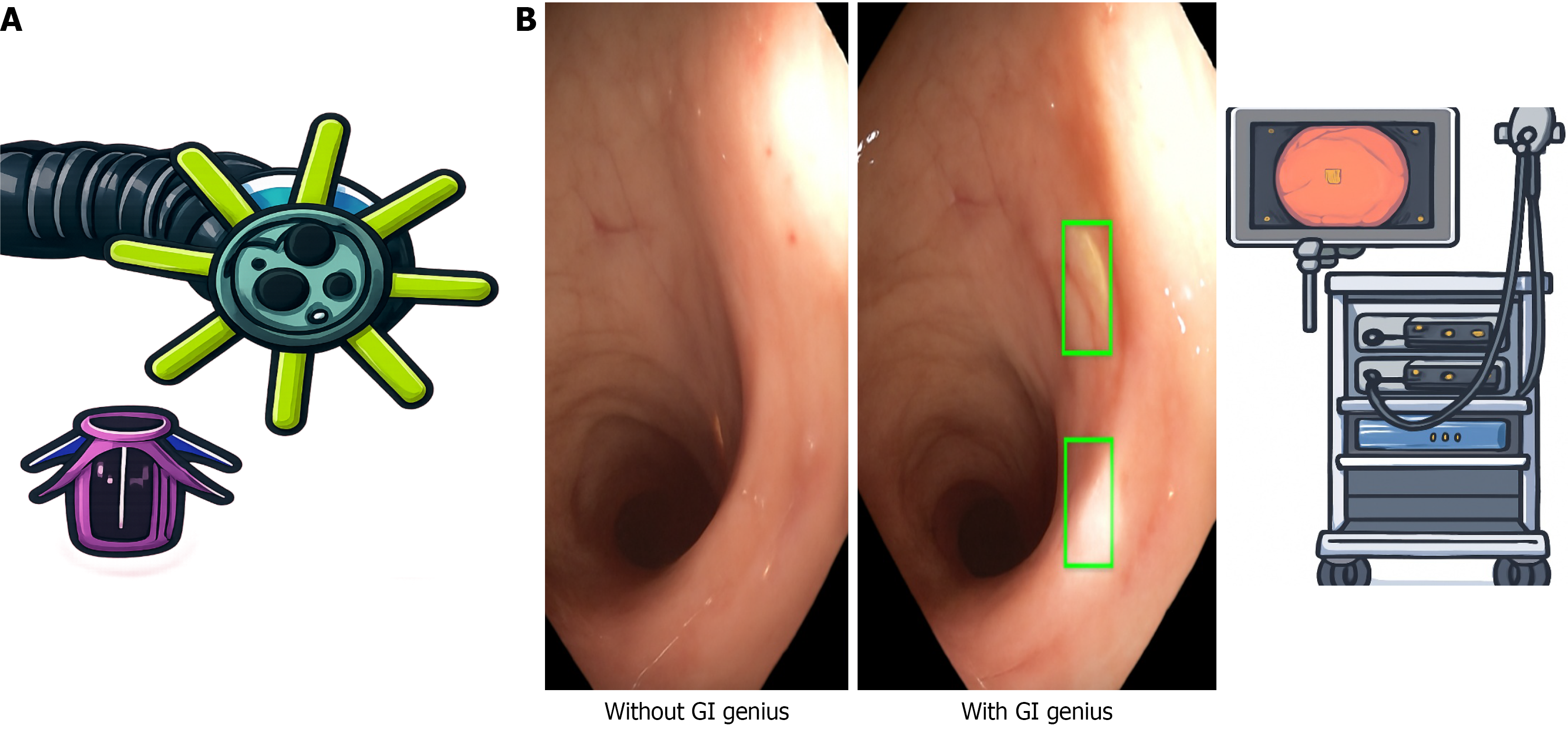

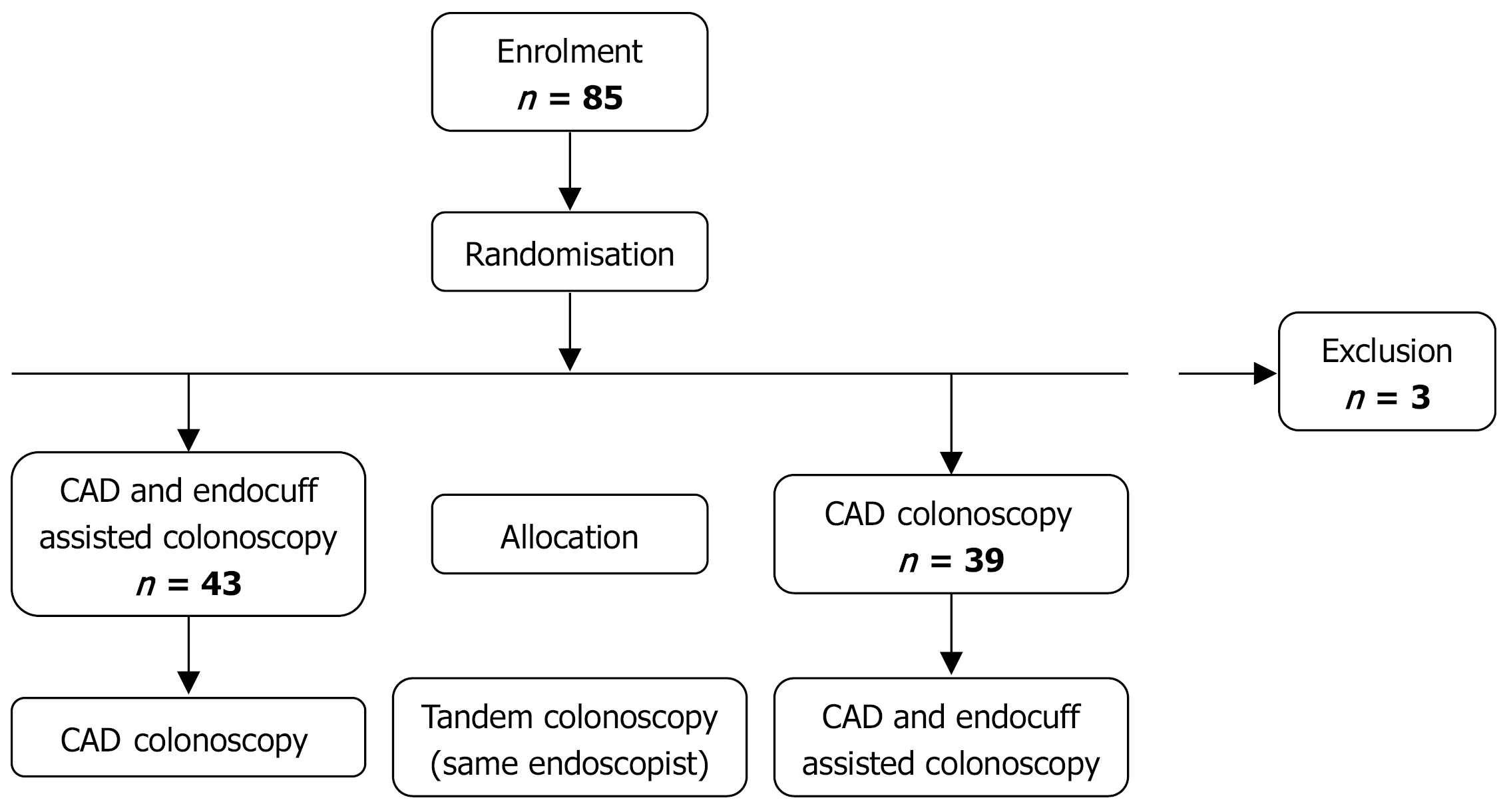

This is a single-center randomized, tandem colonoscopy trial in which each patient underwent back-to-back colonoscopies performed by the same endoscopists on the same day. The sequence of the procedures was randomized: The first colonoscopy was performed using AI with Endocuff Vision and the second using AI alone and vice versa. All procedures were performed by 2 experienced endoscopists using high definition colonoscopes (CF-H185 L, Olympus, Japan) and the GI Genius (Medtronic Minneapolis, MN, United States) CADe system (Figure 1). The use of antispasmodics and patient position changes during both insertion and withdrawal were recorded.

Major metrics assessed: (1) AMR: The number of adenomas found in the second colonoscopy by the total number of adenomas detected in both colonoscopies combined; (2) ADR: The proportion of screening colonoscopies in which an adenoma is found; (3) Polyp miss rate (PMR): The number of polyps found in the second colonoscopy by the total num

Patients referred for colonoscopy for: (1) Screening; (2) Surveillance post-polypectomy; or (3) Diagnostic reasons.

Study exclusion criteria: (1) Patients with a total Bristol Bowel Preparation score (BPPS) < 6 or BPPS = 0 in any segment of the colon; (2) A history of or newly diagnosed polyposis syndrome; (3) Known colonic stricture; (4) Known severe diver

Data were analyzed using SPSS v27 (IBM SPSS Statistics, Chicago, IL, United States). Variables were expressed as fre

In total, 85 patients were included in the study (51 male and 34 female participants; mean age 63 ± 8 years). Of these, 39 underwent initial colonoscopy with AI assistance alone, whereas 45 were examined using a combination of AI and Endocuff. The predominant indication for colonoscopy was CRC screening, representing 91.8% of all cases. Baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

| Characteristic | Value |

| Age (years) | 62.58 ± 7.587 |

| Male sex | 50 (58.8) |

| Indication | 85 (100) |

| Screening | 75 (88,2) |

| Surveillance | 7 (8.2) |

| Insertion time (minutes) | 5.84 ± 2.52 |

| Bristol Bowel Preparation score | 8.57 ± 1.011 |

| Position change | 79 (96.3) |

| Butylscopolamine | 39 (47.5) |

| Withdrawal time (minutes) | 7.2 ± 2.140 |

No significant differences were observed between the groups with respect to bowel preparation quality, demographic characteristics, or indication for colonoscopy. Withdrawal time did not differ significantly either (7.2 ± 2.5 minutes with Endocuff vs 7.2 ± 1.7 minutes without; P = 0.887). Notably, moderate to severe procedural discomfort was more frequently reported in the Endocuff group, with the difference nearing statistical significance (4/43; 9.3% vs 0/39; P = 0.071). A total of 120 polyps were detected including 53 adenomas, 68 diminutive polyps and 18 advanced adenomas (defined as serrated polyps > 1 cm, adenomas with low grade dysplasia > 1 cm and adenomas and adenomas with high grade dysplasia). A comparison of baseline characteristics between the two groups is presented in Table 2.

| Characteristic | CAD (n = 39) | CAD and E (n = 43) | P value |

| Age (years) | 63 ± 8 | 62 ± 7 | 0.453 |

| Sex (male/female) | 20/19 | 29/14 | 0.117 |

| Bristol Bowel Preparation score | 8.5 ± 0.9 | 8.7 ± 0.5 | 0.137 |

| Insertion time (minutes) | 5.82 ± 2.73 | 5.86 ± 2.34 | 0.943 |

| Position change | 37 (94.8) | 42 (97.6) | 0.456 |

| Butylscopolamine | 9 (30) | 30 (69.7) | < 0.001 |

| Withdrawal (minutes) | 7.2 ± 1.7 | 7.2 ± 2.5 | 0.887 |

| Discomfort (≥ 1) | 16 (41) | 19 (44.1) | 0.474 |

Among all patients the use of butylscopolamine did not affect either the PMR or ADR. The PMR was 0.081 ± 0.158 with butylscopolamine vs 0.083 ± 0.141 without it (P = 0.959), and the AMR was 0.130 ± 0.314 with butylscopolamine vs 0.079 ± 0.185 without it, (P = 0.362).

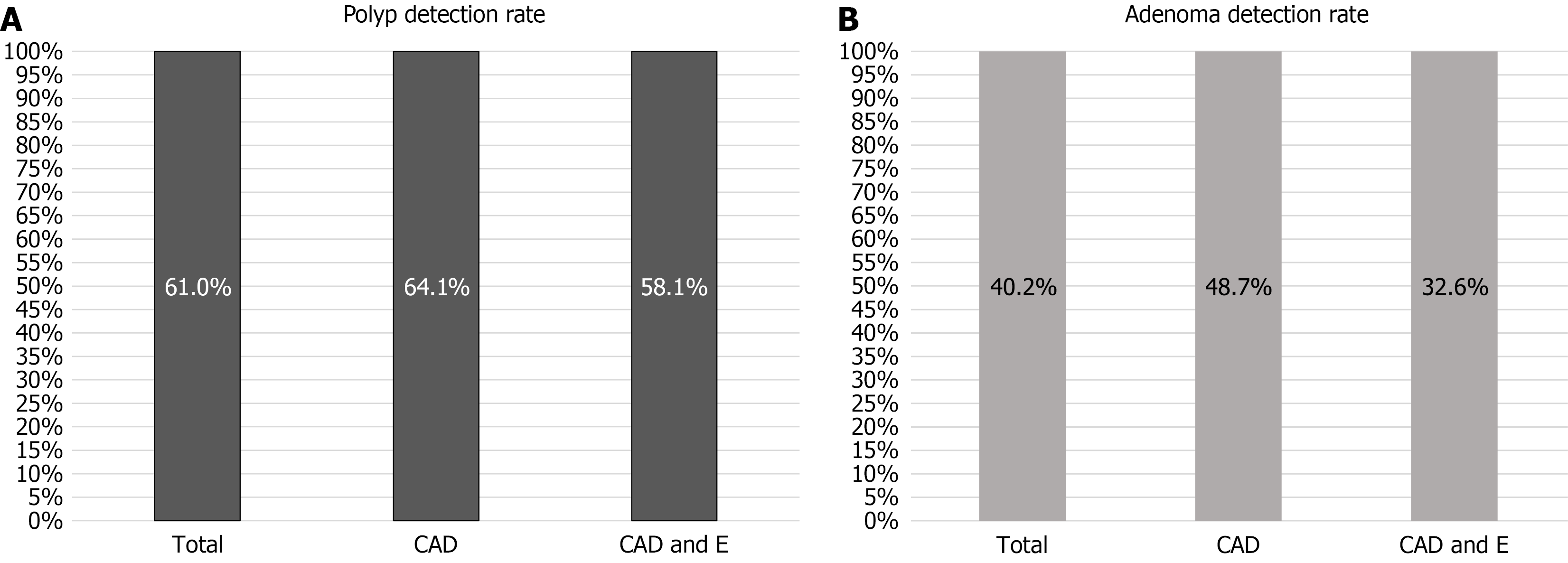

The PDR did not significantly differ between procedures performed with Endocuff (25/39, 64.1%) and those without it (25/43, 58.1%, P = 0.373), although the number of polyps detected per colonoscopy was numerically higher without Endocuff (1.7 ± 2.5 vs 1.2 ± 1.4, P = 0.272) (Figure 3A). No significant differences in PDR were observed in the left or right colon. Using Endocuff, PDRs were 16.3% in the left colon and 44.2% in the right colon, whereas the corresponding rates without Endocuff were 28.2% and 51.3% (P = 0.150 and P = 0.307, respectively). During tandem colonoscopy, an addi

When analyzing only patients who did not receive butylscopolamine, no significant differences in PMR were observed between the two groups (CAD and E: 0.256 ± 0.153 vs CAD: 0.108 ± 0.153, P = 0.088). Similarly, among patients who did receive butylscopolamine, PMR remained comparable (CAD and E: 0.092 ± 0.165 vs CAD: 0.044 ± 0.13333; P = 0.434).

The ADR was numerically higher without Endocuff (19/39, 48.7%) compared to with Endocuff (14/43, 32.6%), although this difference did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.107) (Figure 3B). There were no significant differences in ADR in the left or right colon between the two groups. With Endocuff detection rates were 14.0% (left) and 37.2% (right) vs 20.5% (left) and 48.7% (right) without Endocuff (P = 0.559 and P = 0.372, respectively).

Tandem colonoscopy identified an additional 0.3 ± 0.7 adenomas per procedure, resulting in an AMR of 0.10 ± 0.25. Among patients initially examined with AI alone, the addition of Endocuff during the tandem examination did not yield a significantly higher AMR compared with those initially examined using AI + Endocuff and subsequently with AI alone (0.11 ± 0.24 vs 0.92 ± 0.27; P = 0.727).

When analyzing only patients who did not receive butylscopolamine, no significant difference in AMR was observed (CAD and E: 0.001 vs CAD: 0.128 ± 0.210; P = 0.660). Similarly, among patients who did receive butylscopolamine, AMR remained comparable (CAD and E: 0.136 ± 0.314 vs CAD: 0.111 ± 0.333; P = 0.838). No adverse events were reported during the study.

Recent interest has been raised regarding the combination of novel techniques and devices to improve ADR. In this randomized tandem colonoscopy trial, we evaluated the additive effect of Endocuff Vision combined with AI-assisted colonoscopy on ADR and AMR. Our data did not demonstrate a significant increase in ADR or a reduction in AMR with the combination of Endocuff Vision and AI compared to AI alone. The numerical trend toward higher ADR and PDR without Endocuff was unexpected but not statistically significant.

Previous randomized controlled trials showed a significant increase in ADR with the combination of Endocuff and AI[19,20]. Contrary to expectations based on these studies, our study failed to demonstrate comparable results. Never

Another explanation for the lack of additive benefit from Endocuff could be a potential ceiling effect with AI. Although AI devices provide information solely about lesions within the field of view, it is questionable whether their capabilities in mucosal visualization and lesion detection diminish the incremental advantage offered by Endocuff’s mechanical flattening of the folds. When sub-analyses were performed in the left and right colon, the combination of Endocuff with AI failed to demonstrate an additional gain in the left colon - where most blind spots are traditionally observed - further reinforcing the above hypothesis.

In our study, dynamic position changing was recorded but not included in the initial randomization. An additional gain from combining dynamic position changes with AI warrants further investigation. Moreover, the AMR and PMR during tandem colonoscopy were low and comparable between groups, reinforcing the finding that Endocuff did not improve detection beyond AI. We acknowledge the operator bias inherent in tandem colonoscopy studies; however, no significant differences in procedure-related parameters such as withdrawal time or bowel preparation quality were observed between groups, supporting the notion that the findings are unlikely to be due to procedural confounders. This is a clinically relevant outcome since AMR has a direct link to interval CRC risk[4].

There are limitations to our study. It is a single-center study with a relatively small sample size, which may reduce the power to detect small differences in ADR or AMR. Moreover, both endoscopists performing the procedures were highly experienced. We did not include less experienced or low-detector endoscopists, so it remains uncertain whether AI com

Our study failed to demonstrate the superiority of the combination of Endocuff Vision and AI over AI alone in increasing ADR or reducing AMR. Currently, several large multicenter trials are underway to evaluate the combined efficacy of emerging technologies across different clinical settings and operator experience levels. There remains limited data on the synergistic effect of combining simple procedural techniques with technological innovations. Cost-effectiveness analyses would also be valuable to assess whether integrating these technologies justifies the additional expense.

| 1. | Shaukat A, Kahi CJ, Burke CA, Rabeneck L, Sauer BG, Rex DK. ACG Clinical Guidelines: Colorectal Cancer Screening 2021. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116:458-479. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 160] [Cited by in RCA: 539] [Article Influence: 107.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Qaseem A, Harrod CS, Crandall CJ, Wilt TJ; Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians, Balk EM, Cooney TG, Cross JT Jr, Fitterman N, Maroto M, Obley AJ, Tice J, Tufte JE, Shamliyan T, Yost J. Screening for Colorectal Cancer in Asymptomatic Average-Risk Adults: A Guidance Statement From the American College of Physicians (Version 2). Ann Intern Med. 2023;176:1092-1100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 15.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Corley DA, Jensen CD, Marks AR, Zhao WK, Lee JK, Doubeni CA, Zauber AG, de Boer J, Fireman BH, Schottinger JE, Quinn VP, Ghai NR, Levin TR, Quesenberry CP. Adenoma detection rate and risk of colorectal cancer and death. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1298-1306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1251] [Cited by in RCA: 1670] [Article Influence: 139.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Zhao S, Wang S, Pan P, Xia T, Chang X, Yang X, Guo L, Meng Q, Yang F, Qian W, Xu Z, Wang Y, Wang Z, Gu L, Wang R, Jia F, Yao J, Li Z, Bai Y. Magnitude, Risk Factors, and Factors Associated With Adenoma Miss Rate of Tandem Colonoscopy: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2019;156:1661-1674.e11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 205] [Cited by in RCA: 435] [Article Influence: 62.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Levin B, Lieberman DA, McFarland B, Smith RA, Brooks D, Andrews KS, Dash C, Giardiello FM, Glick S, Levin TR, Pickhardt P, Rex DK, Thorson A, Winawer SJ; American Cancer Society Colorectal Cancer Advisory Group; US Multi-Society Task Force; American College of Radiology Colon Cancer Committee. Screening and surveillance for the early detection of colorectal cancer and adenomatous polyps, 2008: a joint guideline from the American Cancer Society, the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, and the American College of Radiology. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58:130-160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1125] [Cited by in RCA: 1209] [Article Influence: 67.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ngu WS, Bevan R, Tsiamoulos ZP, Bassett P, Hoare Z, Rutter MD, Clifford G, Totton N, Lee TJ, Ramadas A, Silcock JG, Painter J, Neilson LJ, Saunders BP, Rees CJ. Improved adenoma detection with Endocuff Vision: the ADENOMA randomised controlled trial. Gut. 2019;68:280-288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 15.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Zorzi M, Hassan C, Battagello J, Antonelli G, Pantalena M, Bulighin G, Alicante S, Meggiato T, Rosa-Rizzotto E, Iacopini F, Luigiano C, Monica F, Arrigoni A, Germanà B, Valiante F, Mallardi B, Senore C, Grazzini G, Mantellini P; ItaVision Working Group. Adenoma detection by Endocuff-assisted versus standard colonoscopy in an organized screening program: the "ItaVision" randomized controlled trial. Endoscopy. 2022;54:138-147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Jaensch C, Jepsen MH, Christiansen DH, Madsen AH, Madsen MR. Adenoma and serrated lesion detection with distal attachment in screening colonoscopy: a randomized controlled trial. Surg Endosc. 2022;36:1-9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | van Doorn SC, van der Vlugt M, Depla A, Wientjes CA, Mallant-Hent RC, Siersema PD, Tytgat K, Tuynman H, Kuiken SD, Houben G, Stokkers P, Moons L, Bossuyt P, Fockens P, Mundt MW, Dekker E. Adenoma detection with Endocuff colonoscopy versus conventional colonoscopy: a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Gut. 2017;66:438-445. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Floer M, Tschaikowski L, Schepke M, Kempinski R, Neubauer K, Poniewierka E, Kunsch S, Ameis D, Heinzow HS, Auer A, Schmidt HH, Ellenrieder V, Meister T. Standard versus Endocuff versus cap-assisted colonoscopy for adenoma detection: A randomised controlled clinical trial. United European Gastroenterol J. 2021;9:443-450. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Patel HK, Chandrasekar VT, Srinivasan S, Patel SK, Dasari CS, Singh M, Le Cam E, Spadaccini M, Rex D, Sharma P. Second-generation distal attachment cuff improves adenoma detection rate: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;93:544-553.e7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Wang J, Ye C, Fei S. Endocuff-assisted versus standard colonoscopy for improving adenoma detection rate: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Tech Coloproctol. 2023;27:91-101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Walls M, Houwen BBSL, Rice S, Seager A, Dekker E, Sharp L, Rees CJ. The effect of the endoscopic device Endocuff™/Endocuff vision™ on quality standards in colonoscopy: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Colorectal Dis. 2023;25:573-585. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Spadaccini M, Marco A, Franchellucci G, Sharma P, Hassan C, Repici A. Discovering the first US FDA-approved computer-aided polyp detection system. Future Oncol. 2022;18:1405-1412. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Barua I, Vinsard DG, Jodal HC, Løberg M, Kalager M, Holme Ø, Misawa M, Bretthauer M, Mori Y. Artificial intelligence for polyp detection during colonoscopy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Endoscopy. 2021;53:277-284. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 179] [Article Influence: 35.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 16. | Hassan C, Spadaccini M, Mori Y, Foroutan F, Facciorusso A, Gkolfakis P, Tziatzios G, Triantafyllou K, Antonelli G, Khalaf K, Rizkala T, Vandvik PO, Fugazza A, Rondonotti E, Glissen-Brown JR, Kamba S, Maida M, Correale L, Bhandari P, Jover R, Sharma P, Rex DK, Repici A. Real-Time Computer-Aided Detection of Colorectal Neoplasia During Colonoscopy : A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2023;176:1209-1220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 47.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Makar J, Abdelmalak J, Con D, Hafeez B, Garg M. Use of artificial intelligence improves colonoscopy performance in adenoma detection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2025;101:68-81.e8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 42.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Maida M, Marasco G, Maas MHJ, Ramai D, Spadaccini M, Sinagra E, Facciorusso A, Siersema PD, Hassan C. Effectiveness of artificial intelligence assisted colonoscopy on adenoma and polyp miss rate: A meta-analysis of tandem RCTs. Dig Liver Dis. 2025;57:169-175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Lui TK, Lam CP, To EW, Ko MK, Tsui VWM, Liu KS, Hui CK, Cheung MK, Mak LL, Hui RW, Wong SY, Seto WK, Leung WK. Endocuff With or Without Artificial Intelligence-Assisted Colonoscopy in Detection of Colorectal Adenoma: A Randomized Colonoscopy Trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2024;119:1318-1325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Spadaccini M, Hassan C, Rondonotti E, Antonelli G, Andrisani G, Lollo G, Auriemma F, Iacopini F, Facciorusso A, Maselli R, Fugazza A, Bambina Bergna IM, Cereatti F, Mangiavillano B, Radaelli F, Di Matteo F, Gross SA, Sharma P, Mori Y, Bretthauer M, Rex DK, Repici A; CERTAIN Study Group. Combination of Mucosa-Exposure Device and Computer-Aided Detection for Adenoma Detection During Colonoscopy: A Randomized Trial. Gastroenterology. 2023;165:244-251.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Williet N, Tournier Q, Vernet C, Dumas O, Rinaldi L, Roblin X, Phelip JM, Pioche M. Effect of Endocuff-assisted colonoscopy on adenoma detection rate: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Endoscopy. 2018;50:846-860. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 22. | Facciorusso A, Buccino VR, Sacco R. Endocuff-assisted versus Cap-assisted Colonoscopy in Increasing Adenoma Detection Rate. A Meta-analysis. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2020;29:415-420. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Cavallaro LG, Hassan C, Lecis P, Galliani E, Dal Pont E, Iuzzolino P, Roldo C, Soppelsa F, Germanà B. The impact of Endocuff-assisted colonoscopy on adenoma detection in an organized screening program. Endosc Int Open. 2018;6:E437-E442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Triantafyllou K, Gkolfakis P, Tziatzios G, Papanikolaou IS, Fuccio L, Hassan C. Effect of Endocuff use on colonoscopy outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25:1158-1170. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/