Published online Mar 5, 2026. doi: 10.4292/wjgpt.v17.i1.112803

Revised: October 23, 2025

Accepted: January 4, 2026

Published online: March 5, 2026

Processing time: 189 Days and 6.3 Hours

Increasing age is a major risk factor for colorectal neoplasia, with older adults showing a higher incidence of adenomas compared to individuals under 60 years. Early detection of colonic adenomas and polyps significantly reduces the risk of colorectal cancer. Key quality indicators for colonoscopy include the adenoma detection rate (ADR), polyp detection rate (PDR), and cecal intubation rate (CIR). However, studies comparing these metrics in elderly patients deeply sedated with propofol vs those undergoing colonoscopy without sedation show mixed results.

To evaluate deep propofol sedation vs no sedation impact on ADR, PDR, and CIR in elderly patients undergoing screening colonoscopy.

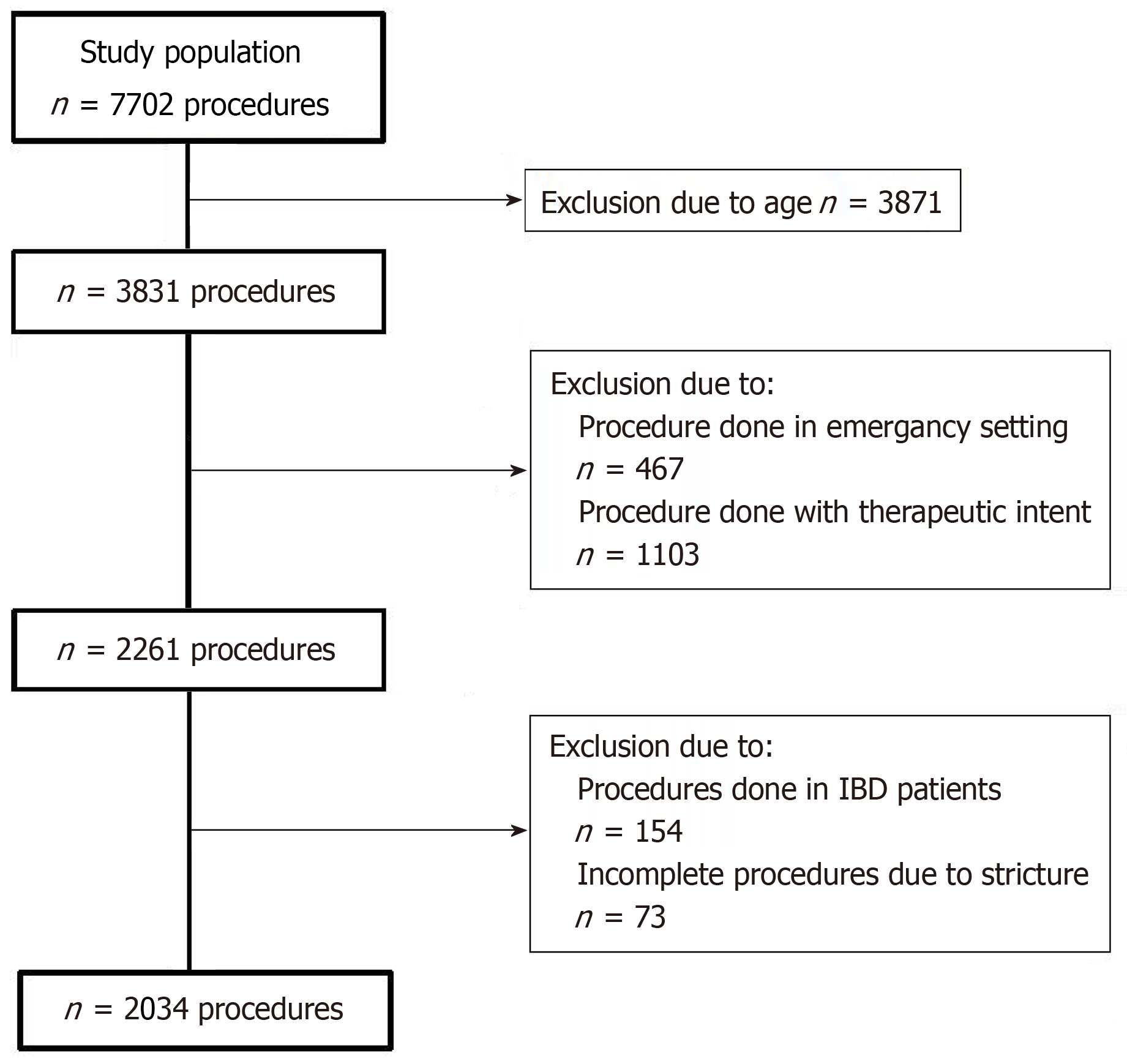

This retrospective cohort study included adults over 60 years who underwent their first screening colonoscopy between January 2017 and September 2023. Exclusion criteria were emergency procedures, inflammatory bowel disease, procedures performed for therapeutic intent, and inadequate bowel preparation [Boston Bowel Pre

A total of 2034 patients (46.4% female; mean age: 70 years) were included, of whom 622 (30.6%) underwent colonoscopy under deep sedation. The overall PDR was 51.65%, ADR was 33.3%, and CIR was 94.25%. After adjusting for confounders [age, sex, body mass index (BMI), BBPS, operation, and diverticulosis], no significant differences were observed in PDR (51.8% vs 51.5%), ADR (33.5% vs 32.5%), or CIR (93.2% vs 95.3%) between the no-sedation and deep-sedation groups. Higher BMI (B = 0.96, P < 0.01) and male sex (B = 0.64, P < 0.01) were independent predictors of higher ADR.

In this elderly cohort, propofol-induced deep sedation did not significantly improve ADR, PDR, or CIR. Further research is warranted to clarify its effect on colonoscopy quality metrics in older populations.

Core Tip: Increasing life expectancy and population aging have increased the incidence of colorectal adenomas and cancers, especially among elderly individuals with obesity. Individual health assessments are crucial, as strict age-based decision-making alone is insufficient. Physicians need to prioritize both patient comfort and procedural safety when considering sedation. Although sedation may not boost overall detection and completion rates, it may be beneficial for obese, male, and late-elderly patients. Effective bowel preparation is the key factor influencing colonoscopy completion in the elderly. Therefore, providing additional guidance and support on bowel preparation is essential for obese elderly men to improve colonoscopy outcomes.

- Citation: Tomasic V, Ćaćić P, Siranovic Pongrac I, Pelajić S, Barsic N, Arefijev A, Lerotic I, Blazevic A, Bišćanin A. Impact of sedation on adenoma and polyp detection rates and cecal intubation in elderly patients undergoing screening colonoscopy. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther 2026; 17(1): 112803

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2150-5349/full/v17/i1/112803.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4292/wjgpt.v17.i1.112803

According to recent statistics, approximately 10% of all cancer cases worldwide are colorectal cancer (CRC), making it the second most frequent cancer worldwide and the second leading cause of cancer-related mortality[1-3]. The majority of CRC cases occur among elderly patients. Over the last couple of years, its incidence has been decreasing in high-income countries, predominantly because of the implementation of effective screening programs[2]. However, in most cases, the diagnosis is still made at advanced stages when treatment options are limited. Therefore, early diagnosis and removal of potential precancerous lesions are crucial to reduce CRC-related mortality.

Colonoscopy is the gold standard and the most effective method to screen for CRC and detect precancerous lesions[4]. It can identify high-risk neoplastic lesions, thereby considerably reducing the development of CRC and improving patient prognosis. To assess colonoscopy performance and minimize the risk of interval CRC, numerous quality indicators have been proposed[5,6]. Among those, adenoma detection rate (ADR) is considered the most important[7]. ADR is influenced by multiple factors, such as the minimal colonoscopy withdrawal time, quality of bowel preparation, cecal intubation rate (CIR), use of sedation, retroflexion in the right colon, differences in colorectal segments, and the use of highlighting tools such as high-definition endoscopy and virtual chromoendoscopy[8-10]. An ideal colonoscopy quality indicator is an ADR of at least 20% for female patients and 30% or more for male patients[11]. However, ADR can be challenging to measure owing to its dependency on pathology reporting. Alternatively, the polyp detection rate (PDR) might be utilized as a surrogate quality indicator[12]. PDR has been shown to correlate well with ADR, with ADRs of 25% in men and 15% in women corresponding to PDRs of 40% and 30%, respectively[13]. Another key quality indicator is the CIR, which reflects the rate of complete colonoscopy and thorough mucosal inspection[14,15]. A complete colonoscopy is required to ensure a high-quality colon inspection. In contrast, incomplete procedures may result in missed lesions, additional costs, and patient inconvenience owing to the need for repeat examinations[16].

The diagnostic yield of colonoscopy generally increases with age, as the incidence of colorectal pathology and related symptoms rises over time. Consequently, a significant proportion of diagnostic, screening, and surveillance colonoscopies are performed in elderly patients. However, colonoscopy carries an increased risk of adverse events, inadequate bowel preparation, and incomplete examinations[17]. The procedure is also technically more challenging in elderly individuals and is associated with lower completion rates. Therefore, colonoscopy in older or frail patients should be performed only when the potential benefits clearly outweigh the associated risks.

Colonoscopy is frequently associated with anxiety, embarrassment, pain, and discomfort, all of which contribute to reduced adherence to CRC screening guidelines and deter patients from completing recommended procedures. Among various anxiety-reduction strategies used in outpatient settings, propofol sedation has emerged as an effective approach to enhance patient comfort while maintaining procedural efficacy.

Sedation has become a routine practice in endoscopic procedures during the last few decades[18]. Several studies have demonstrated that sedation not only minimizes patient discomfort and pain but also enhances operator satisfaction by shortening procedural duration[19-21]. However, considerable debate remains regarding the influence of sedation on colonoscopy quality indicators, such as ADR and CIR, as well as that of endoscopist experience on these outcomes[22]. More research is needed to determine whether sedation is favorable for ADR.

Limited safety data currently exist regarding the use of propofol sedation during screening colonoscopy in elderly patients, warranting further investigation into its risks and benefits in this population. Therefore, this study aimed to determine the impact of propofol sedation in patients aged 60 years and above on ADR, PDR, and CIR during screening and diagnostic colonoscopies.

This single-center, STROBE-compliant retrospective cohort study was performed using data retrieved from the electronic database of our clinical center. We included patients aged 60 years and above who underwent their initial screening or diagnostic colonoscopy from January 2017 to September 2023.

The exclusion criteria were: (1) Emergency colonoscopies; (2) Inflammatory bowel disease; (3) Procedures performed with therapeutic intent; and (4) Incomplete colonoscopies due to failed cecal intubation resulting from patient-reported pain, colonic stricture, or inadequate bowel preparation, defined as a Boston bowel preparation scale (BBPS) score below 6.

The research was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, the STROBE guidelines, and the recommendations of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors[23,24]. The study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Sestre Milosrdnice University Hospital Center, Zagreb, Croatia (approval No. 251-29-11/3-25-11). Owing to the retrospective nature of the study, which involved physicians reviewing patient records they had authored and to which they had authorized access, additional informed consent was not required.

All authors declare that they have no financial nor personal relationships with other people or organizations that could have influenced their work. The authors did not receive any financial support for the research, authorship, nor publication of this manuscript.

The primary colonoscopy quality indicators analyzed were ADR, PDR, and CIR.

The following data were collected: Age, sex, height, weight, history of previous abdominal or pelvic surgery, use of sedation during colonoscopy, BBPS score, presence of colonic diverticulosis, ADR, PDR, and CIR. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated using the standard formula: Weight (kg) divided by the square of the height (m). All direct and indirect individual identifiers were removed to ensure confidentiality. Data accuracy was independently verified by two investigators.

In accordance with the World Health Organization definition, an age of 60 years was used as the cutoff for defining elderly status in this study[25]. The PDR was defined as the percentage of complete colonoscopies in which one or more polyps were detected. The ADR was defined as the percentage of complete colonoscopies in which one or more histologically confirmed adenomas were detected. CIR was defined as the percentage of colonoscopies in which the cecum was successfully intubated, with clear visualization of key anatomical landmarks such as the appendiceal orifice and the ileocecal valve.

All patients were thoroughly informed about the procedure and provided written informed consent before undergoing screening colonoscopy. At our center, patients had the option to undergo the procedure with or without sedation. In the sedation group, all patients received propofol and sufentanyl, administered under the supervision and at the discretion of an anesthesiologist. Patients in the non-sedation group did not receive conscious sedation, analgesia, or on-demand sedation/analgesia.

All colonoscopies were performed by experienced endoscopists who had performed more than 500 procedures and demonstrated consistent achievement of established quality metrics. The procedures were conducted using the latest generation of high-definition white-light endoscopes (EVIS EXERA III Endoscopy System; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Participants’ characteristics were assessed using descriptive statistics. The normality of data distribution was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, supported by visual inspection of distribution plots and comparison of mean and median values. Continuous variables were reported as medians with interquartile ranges, while categorical variables were presented as frequencies and valid percentages. Continuous variables were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U test and categorical variables using the χ2 test. Binary logistic regression analysis was conducted to adjust for confounders. All tests were two-tailed, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Univariable logistic regression analysis was used to examine the effect size of factors associated with PDR, ADR, and CIR, with results presented as odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Multivariable logistic regression was subsequently performed to assess the association between sedation and outcomes, adjusting for potential confounding variables.

Statistical review of the study was performed by a biomedical statistician. All analyses were performed using SPSS Version 30.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States).

This retrospective analysis included data extracted from a single-center electronic database comprising patients’ case charts from computerized registries.

After applying the exclusion criteria (Figure 1), we enrolled patients aged 60 years and above who underwent their first screening or diagnostic colonoscopy at our clinical center between January 2017 and September 2023. A total of 2034 procedures were analyzed, of which 622 (30.6%) were performed under propofol sedation. The median age of the patients was 70 (range: 65-75) years, and 1014 (49.9%) of them were female. The overall CIR was 93.9%, with terminal ileum intubation achieved in 50.3% of cases. The PDR was 51.7%, and the ADR was 33.2%. Assessment of normality indicated that the data significantly deviated from a normal distribution.

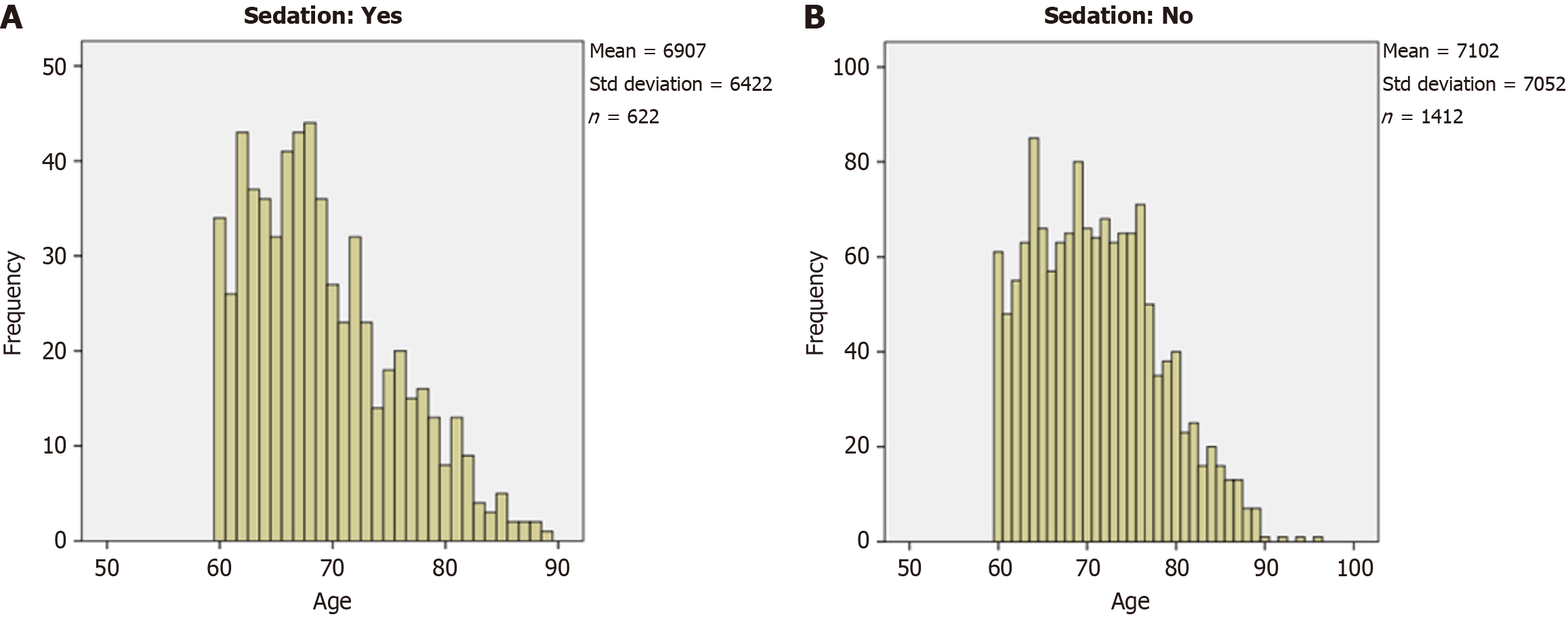

Patient characteristics and outcomes according to groups are presented in Table 1, with age distribution available in Figure 2. Patients in the sedation group were slightly younger (U = 368204, Z = -5.8, P < 0.01), more likely to have diverticulosis [χ² (1, n = 2031) = 8.14], and less likely to have a history of prior surgery [χ² (1, n = 2034) = 4.4]. Moreover, a significantly higher proportion of women were in the sedation group than in the sedation-free group [χ2 (1, n = 2034) = 22.17, P < 0.01].

| Variable | Sedation, n = 622 | No sedation, n = 1412 | P value |

| Age in years | 68 (64-73) | 70 (65-76) | < 0.01a |

| Female sex | 359 (57.7) | 655 (46.4) | < 0.01b |

| BMI kg/m2 | 27.1 (23.7-29.9) | 27 (24.3-30.5) | 0.25 |

| BBPS | 9 (6-9) | 8 (6-9) | 0.15 |

| PDR | 320 (51.5) | 731 (51.8) | 0.92 |

| ADR | 202 (32.5) | 472 (33.5) | 0.68 |

| CIR | 593 (95.3) | 1316 (93.2) | 0.07 |

| Intubation of terminal ileum | 342 (55.1) | 680 (48.2) | < 0.01a |

| Previous operation | 186 (29.9) | 488 (34.6) | 0.04 |

| Diverticulosis | 272 (43.8) | 523 (37.1) | < 0.01c |

To explore the effect of the factors on PDR, ADR, and CIR, univariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses were performed. Only patients who underwent a complete colonoscopy (i.e. with cecal intubation achieved) were included in the analyses of PDR and ADR.

As shown in Tables 2, 3, and 4, univariable logistic regression analysis identified male sex and higher BMI as significant predictors of increased PDR and ADR. Additionally, younger age, higher BBPS scores, and the presence of diverticulosis were significantly associated with higher CIR. Although a trend toward higher CIR was observed in the sedation group, this difference did not reach statistical significance. No significant association was observed between sedation and either ADR or PDR.

Furthermore, multivariable analyses were performed for each endoscopic outcome (Tables 5, 6, and 7). Higher BMI was a risk factor for higher PDR and ADR but a lower CIR. Male sex was also independently associated with a higher ADR, while the presence of diverticulosis was associated with a lower ADR. Female patients and those with higher BBPS scores were more likely to achieve a complete colonoscopy. Even after adjusting for all relevant parameters, sedation was not found to be significantly associated with improvements in PDR, ADR, or CIR (Table 8).

| Variable | B | S.E. | Wald | df | Sig. | Exp(B) | 95%CI lower-upper |

| Sex (1) | -0.214 | 0.162 | 1.733 | 1 | 0.188 | 0.807 | 0.587-1.11 |

| Age | 0.012 | 0.012 | 1.025 | 1 | 0.311 | 1.012 | 0.989-1.035 |

| Sedation (1) | 0.183 | 0.179 | 1.054 | 1 | 0.305 | 1.201 | 0.846-1.705 |

| BBPS | -0.006 | 0.045 | 0.016 | 1 | 0.9 | 0.994 | 0.911-1.085 |

| Diverticulosis (1) | -0.161 | 0.169 | 0.911 | 1 | 0.34 | 0.851 | 0.612-1.185 |

| Operations (1) | 0.15 | 0.164 | 0.83 | 1 | 0.362 | 1.161 | 0.842-1.602 |

| BMI | 0.062 | 0.015 | 16.005 | 1 | 0a | 1.064 | 1.032-1.096 |

| Constant | -1.88 | 1.018 | 3.409 | 1 | 0.065 | 0.153 |

| Variable | B | S.E. | Wald | df | Sig. | Exp(B) | 95%CI lower-upper |

| Sex (1) | -0.366 | 0.158 | 5.354 | 1 | 0.021a | 0.694 | 0.509-0.946 |

| Age | 0.006 | 0.011 | 0.286 | 1 | 0.593 | 1.006 | 0.984-1.028 |

| Sedation (1) | -0.041 | 0.173 | 0.056 | 1 | 0.814 | 0.96 | 0.683-1.349 |

| BBPS | -0.01 | 0.043 | 0.053 | 1 | 0.819 | 0.99 | 0.91-1.077 |

| Diverticulosis (1) | -0.334 | 0.165 | 4.084 | 1 | 0.043b | 0.716 | 0.518-0.99 |

| Operations (1) | 0.105 | 0.159 | 0.433 | 1 | 0.51 | 1.11 | 0.813-1.516 |

| BMI | 0.039 | 0.015 | 7.024 | 1 | 0.008c | 1.04 | 1.01-1.07 |

| Constant | -1.43 | 0.989 | 2.092 | 1 | 0.148 | 0.239 |

| Variable | B | S.E. | Wald | df | Sig. | Exp(B) | 95%CI for Exp(B) |

| Sex | -0.450 | 0.159 | 7.956 | 1 | 0.005a | 0.638 | 0.467-0.872 |

| Age | -0.012 | 0.011 | 1.221 | 1 | 0.269 | 0.988 | 0.966-1.010 |

| Sedation | 0.219 | 0.173 | 1.596 | 1 | 0.206 | 1.245 | 0.886-1.748 |

| BBPS | 0.346 | 0.045 | 59.857 | 1 | 0.000b | 1.414 | 1.295-1.543 |

| Diverticulosis | 0.238 | 0.166 | 2.064 | 1 | 0.151 | 1.268 | 0.917-1.754 |

| Operation | -0.129 | 0.160 | 0.647 | 1 | 0.421 | 0.879 | 0.642-1.204 |

| BMI | -0.040 | 0.015 | 7.116 | 1 | 0.008c | 0.961 | 0.934-0.990 |

| Constant | -0.541 | 0.993 | 0.297 | 1 | 0.586 | 0.582 | - |

| Variable | OR (95%CI) | P value |

| PDR | 1.2 (0.85-1.71) | 0.31 |

| ADR | 0.96 (0.68-1.35) | 0.81 |

| CIR | 1.25 (0.89-1.75) | 0.21 |

Additionally, the cohort was stratified into two age groups (60-74 years and ≥ 75 years) to assess the potential differential impact of sedation between the groups (Table 9). In both groups, higher BMI was a significant predictor of increased PDR. For ADR, male sex and higher BMI were significant predictors in the younger group, whereas in the older group, only BMI was associated with higher ADR. Although sedation in the older group showed a trend toward improving ADR, this finding did not reach statistical significance. The only significant predictor of higher CIR in both age groups was a higher BBPS score. Complete analyses of multivariable logistic regression are provided in Tables 5, 6, 7, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, and 15.

| Variable | Age group 60-74 years | Age group ≥ 75 years | ||

| OR (95%CI) | P value | OR (95%CI) | P value | |

| PDR | 1.23 (0.81-1.88) | 0.32 | 1.05 (0.55-2.01) | 0.88 |

| ADR | 1.22 (0.81-1.83) | 0.35 | 0.52 (0.28-0.99) | 0.05 |

| CIR | 0.79 (0.18-3.56) | 0.76 | 0.77 (0.18-3.42) | 0.74 |

| Variable | B | S.E. | Wald | df | Sig. | Exp(B) | 95%CI for Exp(B) (lower-upper) |

| Sex (1) | -0.285 | 0.198 | 2.060 | 1 | 0.151 | 0.752 | 0.510-1.110 |

| Age | 0.019 | 0.024 | 0.634 | 1 | 0.426 | 1.019 | 0.973-1.068 |

| Sedation (1) | 0.214 | 0.214 | 1.002 | 1 | 0.317 | 1.239 | 0.815- 1.884 |

| BBPS | -0.059 | 0.057 | 1.076 | 1 | 0.300 | 0.943 | 0.844-1.054 |

| Diverticulosis (1) | -0.092 | 0.210 | 0.191 | 1 | 0.662 | 0.912 | 0.605-1.376 |

| Operations (1) | 0.149 | 0.201 | 0.549 | 1 | 0.459 | 1.161 | 0.782-1.722 |

| BMI | 0.052 | 0.017 | 9.612 | 1 | 0.002a | 1.053 | 1.019-1.089 |

| Variable | B | S.E. | Wald | df | Sig. | Exp(B) | 95%CI for Exp(B) (lower-upper) |

| Sex (1) | 0.031 | 0.295 | 0.011 | 1 | 0.916 | 1.032 | 0.579-1.839 |

| Age | -0.023 | 0.038 | 0.351 | 1 | 0.553 | 0.978 | 0.907-1.054 |

| Sedation (1) | 0.049 | 0.331 | 0.022 | 1 | 0.882 | 1.051 | 0.549-2.011 |

| BBPS | 0.089 | 0.075 | 1.402 | 1 | 0.236 | 1.093 | 0.943-1.266 |

| Diverticulosis (1) | -0.266 | 0.298 | 0.797 | 1 | 0.372 | 0.766 | 0.427-1.374 |

| Operations (1) | 0.123 | 0.296 | 0.174 | 1 | 0.677 | 1.131 | 0.633-2.020 |

| BMI | 0.107 | 0.038 | 8.016 | 1 | 0.005a | 1.113 | 1.033-1.198 |

| Variable | B | S.E. | Wald | df | Sig. | Exp(B) | 95%CI for Exp(B) (lower-upper) |

| Sex (1) | -0.498 | 0.196 | 6.441 | 1 | 0.011a | 0.608 | 0.414-0.893 |

| Age | 0.021 | 0.023 | 0.863 | 1 | 0.353 | 1.022 | 0.976-1.069 |

| Sedation (1) | 0.196 | 0.209 | 0.884 | 1 | 0.347 | 1.217 | 0.808-1.832 |

| BBPS | -0.060 | 0.054 | 1.241 | 1 | 0.265 | 0.942 | 0.847-1.047 |

| Diverticulosis (1) | -0.328 | 0.208 | 2.503 | 1 | 0.114 | 0.720 | 0.479-1.082 |

| Operations (1) | 0.130 | 0.197 | 0.434 | 1 | 0.510 | 1.139 | 0.774-1.675 |

| BMI | 0.034 | 0.017 | 4.232 | 1 | 0.040b | 1.035 | 1.002-1.069 |

| Variable | B | S.E. | Wald | df | Sig. | Exp(B) | 95%CI for Exp(B) (lower-upper) |

| Sex (1) | -0.036 | 0.284 | 0.016 | 1 | 0.901 | 0.965 | 0.553-1.685 |

| Age | -0.063 | 0.038 | 2.705 | 1 | 0.100 | 0.939 | 0.871-1.012 |

| Sedation (1) | -0.653 | 0.326 | 4.009 | 1 | 0.045a | 0.520 | 0.275-0.986 |

| BBPS | 0.082 | 0.073 | 1.254 | 1 | 0.263 | 1.086 | 0.940-1.254 |

| Diverticulosis (1) | -0.311 | 0.289 | 1.159 | 1 | 0.282 | 0.732 | 0.416-1.291 |

| Operations (1) | 0.012 | 0.284 | 0.002 | 1 | 0.967 | 1.012 | 0.579-1.767 |

| BMI | 0.065 | 0.033 | 3.883 | 1 | 0.049b | 1.067 | 1.000-1.138 |

| Variable | B | S.E. | Wald | df | Sig. | Exp(B) | 95%CI for Exp(B) (lower-upper) |

| Sex | -0.681 | 0.623 | 1.195 | 1 | 0.274 | 0.506 | 0.149-1.716 |

| Age | 0.056 | 0.086 | 0.427 | 1 | 0.514 | 1.058 | 0.894-1.253 |

| Sedation (1) | -0.232 | 0.766 | 0.092 | 1 | 0.762 | 0.793 | 0.177-3.559 |

| BBPS | 0.544 | 0.119 | 20.911 | 1 | 0.000a | 1.724 | 1.365-2.177 |

| Diverticulosis (1) | 0.748 | 0.714 | 1.099 | 1 | 0.294 | 2.113 | 0.522-8.562 |

| Operations (1) | 0.100 | 0.610 | 0.027 | 1 | 0.870 | 1.105 | 0.334-3.655 |

| BMI | 0.063 | 0.058 | 1.181 | 1 | 0.277 | 1.065 | 0.951-1.193 |

| Variable | B | S.E. | Wald | df | Sig. | Exp(B) | 95%CI for Exp(B) (lower-upper) |

| Sex | -0.681 | 0.623 | 1.195 | 1 | 0.274 | 0.506 | 0.149-1.716 |

| Age | 0.056 | 0.086 | 0.427 | 1 | 0.514 | 1.058 | 0.894-1.253 |

| Sedation (1) | -0.232 | 0.766 | 0.092 | 1 | 0.762 | 0.793 | 0.177-3.559 |

| BBPS | 0.544 | 0.119 | 20.911 | 1 | 0.000a | 1.724 | 1.365-2.177 |

| Diverticulosis (1) | 0.748 | 0.714 | 1.099 | 1 | 0.294 | 2.113 | 0.522-8.562 |

| Operations (1) | 0.100 | 0.610 | 0.027 | 1 | 0.870 | 1.105 | 0.334-3.655 |

| BMI | 0.063 | 0.058 | 1.181 | 1 | 0.277 | 1.065 | 0.951-1.193 |

This retrospective analysis assessed the impact of deep sedation on key colonoscopy quality metrics (ADR, PDR, and CIR), specifically in elderly patients undergoing screening or diagnostic procedures. The main findings indicate that, after adjusting for confounders (age, sex, BMI, and BBPS for PDR/ADR; and age, sex, BMI, BBPS, operation type, and diverticulosis for CIR), there were no statistically significant differences in PDR, ADR, nor CIR between the non-sedation and deep-sedation groups. Furthermore, higher BMI and male sex emerged as independent predictors of increased ADR.

The most significant primary non-modifiable risk factors for adenomatous polyps are age and sex. Increasing age is a significant risk factor for the incidence of CRC. Individuals aged 70-75 years have a 10%-15% higher risk of developing adenomas compared to those aged 50-55 years[26]. In a study by Liang et al[27], the PDR was 1.51 times higher in patients aged 50-59 years (95%CI: 1.13-2.01, P = 0.005) and 1.88 times higher in those aged 60-69 years (95%CI: 1.37-2.58, P < 0.001). Additionally, the PDR was 1.622 times higher in male patients compared to female patients (95%CI: 1.278-2.058, P < 0.001). These findings align with GLOBOCAN data, which report a higher global incidence of CRC in men, with an age-standardized rate of 23.4 per 100000 compared to 16.2 per 100000 in women, yielding a male-to-female ratio of 1.4[2].

There has been a dramatic increase in obesity worldwide. Since 1990, the global prevalence of obesity has increased by 155.1% in males and 104.9% in females, and by 2050, it is estimated to affect over half of the adult population[28]. Current evidence indicates that obesity is one of the key modifiable risk factors for precancerous polyps and sporadic CRC[26]. Recent reviews have shown that overweight and obese individuals have approximately 18% and 32% higher risks of CRC, respectively, compared to those with normal weight[29,30]. Moreover, a random-effects meta-analysis of 17 studies encompassing 168201 participants revealed even stronger associations with colorectal adenomas, demonstrating a greater than 40% increased risk for both overweight and obese groups[31]. The presence of central obesity, sarcopenic obesity, and current smoking habits has been strongly linked to the occurrence of advanced adenomatous lesions[32]. These lesions are characterized by adenomas measuring more than 10 mm, the presence of three or more non-advanced adenomas, adenomas with a villous component, high-grade dysplasia, or invasive CRC. As global populations age, the prevalence of obesity among older adults is also expected to rise. Between 2007 and 2010, about 35% of adults aged 65 years and older in the United States were classified as obese based on BMI, and this population is projected to more than double-from 40.2 million to 88.5 million-by the year 2050[33].

Most of the CRC cases and deaths in the United States are potentially attributable to modifiable risk factors[34]. Colorectal polyps, especially adenomas, are well-known precursors of CRC, and lifestyle-related factors such as obesity play a significant role in the development and progression of these polyps[35]. Primary prevention of CRC focuses on identifying and reducing these risk factors, while secondary prevention focuses on early detection and removal of premalignant colorectal lesions through screening. Between 2008 and 2017, CRC mortality rates among individuals aged 65 years and older declined by 3% annually[36]. This reduction is largely attributed to increased participation in CRC screening programs, primarily using colonoscopy, and the subsequent removal of precancerous adenomas[37].

In real-world clinical practice, the miss rate for colorectal neoplastic polyps can be as high as 28%, indicating that as many as one in four polyps may go undetected during colonoscopy[38]. Studies have shown that patients whose colonoscopies are performed by endoscopists with an ADR below 20% face more than a tenfold higher risk of developing CRC, primarily owing to undetected precancerous lesions during screening[39]. Moreover, ADR shows a strong inverse relationship with the risk of post-colonoscopy CRC, with each 1% increase in ADR associated with a 3% decrease in the incidence of CRC[40]. These findings highlight the role of ADR as a modifiable quality indicator capable of significantly reducing cancer incidence and mortality through meticulous colonoscopy practice.

Several studies have examined the impact of sedation on ADR and PDR, but their findings have been limited and inconclusive[41-47]. The number of patients included in many studies differs significantly between the sedated and non-sedated groups, which may have affected the generalizability of the results.

Zhang et al[41] reported a significant positive association between the increasing use of sedation during colonoscopy and improvements in key quality indicators over a 7-year period. As the proportion of sedated colonoscopies rapidly increased, the ADR increased markedly from 13.53% to 24.69%, and the CIR improved from 91.18% to 96.85%. Furthermore, when directly comparing sedated and non-sedated colonoscopies, significantly higher ADR (22.5% vs 17.0%, P < 0.001) and CIR (94.7% vs 91.2%, P < 0.001) were observed in the sedation group, independent of the endoscopists’ experience level.

A recent study by Xu et al[42] used univariable and multivariate logistic regression analyses to examine the relationship between sedation and ADR during colonoscopy. The results showed that ADR was significantly higher in patients who underwent sedation (36.9%) compared to those who did not (29.1%), with an OR of 1.42 (95%CI: 1.31-1.55, P < 0.001). Multivariate analysis confirmed that sedation was an independent factor associated with increased ADR (OR: 1.49, 95%CI: 1.35-1.65, P < 0.001). However, no significant difference was observed between the sedated and non-sedated groups in the detection rate of advanced adenomas.

In a large single-center study utilizing an electronic endoscopic database of 24795 patients who underwent colonoscopy with or without sedation between 2011 and 2018, multivariable analysis revealed that outpatient colonoscopy performed with sedation was associated with a significantly higher CIR (OR: 3.79, 95%CI: 2.39-6.00) and ADR (OR: 1.45, 95%CI: 1.00-2.10) compared with procedures performed without sedation[43].

In contrast, our findings align with prior single-center studies reporting minimal or no significant impact of sedation on adenoma detection metrics in average-risk populations[44-47].

After propensity score matching, Liang et al[27] performed binary logistic regression analysis on data from 1472 patients divided into two groups based on whether they underwent screening colonoscopy with or without sedation. The results showed no significant difference in ADR or PDR between the groups (P > 0.05).

Han et al[44] investigated the impact of sedated colonoscopy on both overall and segment-specific PDR and ADR, recognizing that CRC incidence and prognosis vary by tumor location. Using multivariate logistic regression analyses, they found that sedated colonoscopy was independently associated with lower overall PDR and ADR, as well as reduced detection rates in the right-sided colon and for both single and multiple polyps or adenomas.

In an analysis of 54063 colonoscopies recorded in the New Hampshire Colonoscopy Registry, multivariate logistic regression initially showed that propofol sedation was associated with a modestly higher ADR (OR: 1.07, 95%CI: 1.03-1.11)[45]. However, when the analysis was restricted to a sample adjusted using inverse probability of treatment weighting based on propensity scores and adjusted for clustering at the endoscopist level, the association between propofol use and ADR was no longer statistically significant (OR: 1.00; 95%CI: 0.95-1.05).

Analysis of data from the Austrian Quality Management for Colon Cancer Prevention program found that sedation during colonoscopy did not increase ADR nor PDR[46]. However, sedation was associated with a higher CIR in both men and women. After accounting for intra-observer variability among endoscopists, the overall CIR was significantly influenced by the interaction between sex and age (P = 0.0049), whereas sedation use itself showed no independent association (P = 0.1435). This aligns with the findings of Zhao et al[47], who reported that sedation during colonoscopy significantly increased the CIR (88.92% with sedation vs 80.64% without sedation, P < 0.0001), while ADR (13.0% vs 12.44%, P = 0.337) and PDR (26.67% vs 27.22%, P = 0.474) remained unchanged regardless of sedation status.

Although direct comparisons cannot be made owing to differences in patient populations, our findings are generally consistent with previous studies suggesting a limited impact of sedation on colonoscopy quality metrics. Nevertheless, additional research is warranted to confirm these observations across broader and more diverse cohorts.

A potential explanation for the lack of significant differences in ADR, PDR, and CIR between sedated and non-sedated groups in our study is that all procedures were performed by experienced endoscopists, which likely minimized performance variability. In both groups, the overall ADR, PDR, and CIR exceeded the recommended benchmarks[14].

Furthermore, the choice of sedation type was left to the patients, with their decisions influenced in part by subjective perceptions of anxiety, stress, and fear related to the colonoscopy procedure. An important factor is also the technical organization of the procedures at our center, where colonoscopies with sedation are typically performed in the morning, and those without sedation in the afternoon, which may further affect the patients’ decisions regarding sedation.

Patient age has traditionally been considered an important factor influencing colonoscopy success rates; however, the widespread adoption of deep sedation with propofol has led to notable improvements in procedural performance. In a study by Cardin et al[48], 1480 consecutive colonoscopies were analyzed, including 319 procedures in patients older than 73 years. The success rate was significantly lower in this older group compared with younger patients (88.1% vs 94.4%, P = 0.0001), although no major technical nor sedation-related complications associated with propofol were observed. Multivariate stepwise logistic regression identified inadequate bowel preparation as the primary factor affecting procedural success in elderly patients (OR: 5.9, 95%CI: 2.25-15.72; P = 0.0003).

Overall, the risk of complications approximately doubles in patients aged 75 years and older compared to younger cohorts, with cardiovascular comorbidities significantly increasing the likelihood of adverse events[49,50]. Colonoscopy in elderly patients is technically more challenging than in younger individuals due to several factors, including a higher prevalence of extensive diverticulosis, increased bowel tortuosity, and the presence of post-surgical adhesions. A meta-analysis found that the mean CIR was 84% for patients over 65 years of age and slightly higher at 84.7% among those over 80-year-old[51], both falling below the recommended benchmarks. Current guidelines recommend achieving a minimum CIR of 90%, with a target of 95% for screening colonoscopies[52]. Additionally, elderly patients are less likely to tolerate large doses of sedation and are more prone to inadequate bowel preparation, both of which can hinder the completion of the procedure. Nonetheless, multiple studies have demonstrated that propofol sedation can be safely administered in elderly patients, despite its tendency to lower blood pressure[53-55].

In certain subgroups of patients aged over 70 years, the risk of screening-related complications may exceed the projected benefits. However, across all ages and life expectancies, the mortality reduction benefits of CRC screening and surveillance consistently surpass the risk of colonoscopy-associated fatalities[56,57].

In elderly individuals with multiple chronic health comorbidities, such as heart disease, diabetes, or chronic respiratory disorders, there is a clear need to carefully weigh the risks and benefits of sedation, as sedative medications can interact with their existing treatments or exacerbate underlying conditions. In these cases, unsedated colonoscopy may be considered, offering distinct advantages such as faster recovery, lower procedural costs, and no requirement for post-procedure escorts. Conversely, elderly patients with high anxiety, low pain tolerance, or conditions that make remaining still difficult may benefit from sedation to improve comfort and the quality of the colonoscopy.

In a prospectively collected, retrospective matched cohort study comparing colonoscopies performed without sedation (with 3.45% of these patients ultimately requiring sedation to complete the procedure) to those performed with sedation, no statistically significant differences were observed between the groups in several key outcomes: Mean cecal intubation time (11.28 minutes vs 10.38 minutes, P = 0.129), ADR (25.1% vs 35.8%, P = 0.060), percentage of patients who experienced no pain during the procedure (93.5% vs 93.5%, P = 1.000), and BBPS scores (2.23 vs 2.34, P = 0.370)[58]. Based on these findings, the authors concluded that on-demand sedation colonoscopy is a feasible and safe alternative that significantly reduces recovery room time before discharge, without compromising procedural quality nor patient comfort.

Another important factor to consider is the type of sedation used. In a bivariate analysis of 574 screening colonoscopies (mean age of 59.26 ± 7.21 years; 52.4% female; mean BMI of 28.08 ± 4.89 kg/m2), no significant differences were observed in PDR nor ADR between the conscious sedation and deep sedation groups[59].

The first randomized controlled trial comparing post-colonoscopy outcomes after water exchange (WE) insertion and insufflation of air or carbon dioxide (CO2) during withdrawal vs CO2 insufflation throughout the procedure demonstrated that CO2 insufflation was associated with less post-colonoscopy discomfort compared to air insufflation, while WE insertion results in less procedural pain compared to both CO2 and air insufflation[60]. Importantly, these findings indicate that patient comfort achieved with this technique is comparable to that achieved with routine or on-demand sedation.

These findings raise the question of whether routine sedation is necessary for all colonoscopy procedures, especially when minimally invasive techniques such as WE and CO2 insufflation can provide similar comfort and satisfaction while potentially reducing the risks, costs, and recovery time associated with sedation.

Recent evidence suggests that both WE and cap-assisted colonoscopy (CAC) are effective techniques for reducing insertion-related pain in unsedated patients undergoing screening colonoscopy[61]. Both methods independently improve ADR and CIR. Furthermore, combining WE with CAC has been shown to provide greater pain reduction compared to WE alone, while maintaining or enhancing detection efficacy.

The global trend of increased life expectancy, coupled with population aging, poses new challenges for public health systems worldwide. The rising prevalence of obesity in the geriatric population, together with the aging process itself, represents a significant primary risk factor for the development of colorectal adenomas and carcinoma. Accordingly, the implementation of effective secondary preventive measures, primarily colonoscopy aimed at early detection and removal of precancerous lesions, remains a crucial aspect of CRC prevention in the elderly population.

Improving the quality of screening colonoscopy by increasing ADR, PDR, and CIR within the geriatric population represents a complex challenge. Although sedation during colonoscopy is occasionally employed to enhance patient comfort, current evidence does not consistently demonstrate its benefit in improving procedural quality indicators. Therefore, its routine use cannot be universally recommended nor applied using a “one size fits all” approach. Our adjusted analysis confirms that deep sedation neither enhances nor impairs lesion detection or cecal intubation success. This suggests that procedural quality benchmarks remain attainable regardless of the sedation strategy used.

When assessing procedural risk, a patient’s physiological age, reflected by their overall health and the presence of comorbidities, is more relevant than their chronological age. Therefore, it is essential to evaluate each patient’s individual health status rather than relying solely on strict age-based thresholds.

The decision to undergo unsedated or sedated screening colonoscopy should be tailored to individual preferences and clinical considerations, such as patient age, comfort, medical history, and procedural needs, to ensure both safety and optimal quality of care.

Mechanistically, sedation may influence colonic motility and patient positioning; however, our data indicate these effects do not translate into measurable differences in mucosal visualization or cecal intubation efficacy. The results of our study indicate that bowel preparation quality in elderly individuals is the primary modifying factor significantly affecting the CIR. While the sedation group exhibited a trend toward a higher CIR, this difference was not statistically significant. Consistent bowel preparation quality across groups likely mitigated any subtle differences attributable to sedation. There is a clear correlation between a higher CIR and enhanced ADR performance[62]. Furthermore, obesity in elderly patients was significantly associated with both ADR and PDR. These findings underscore the importance of providing additional counseling and support on proper bowel preparation for obese elderly individuals, especially males, who have an increased risk of CRN.

A sub-analysis revealed a trend toward improved ADR in late elderly patients (aged over 75 years) undergoing colonoscopy with sedation. Considering the significantly increased risk of colonic polyps in this age group, as well as the elevated risks related to sedation, a personalized and careful approach is required for this vulnerable population.

While sedation did not significantly improve ADR/PDR/CIR in this elderly cohort, patient-centered factors such as comfort and safety profiles must remain primary in procedural decision-making. The findings add nuance to the ongoing discussion surrounding sedation in elderly screening colonoscopy and reinforce the need for individualized care in clinical practice.

The reliability and comprehensiveness of our study results are supported by a relatively large and well-balanced sample size, the inclusion of multiple confounding factors, and a focus on an elderly population-an age group often underrepresented in sedation studies. All colonoscopies were performed by experienced endoscopists using the latest generation of high-definition white-light endoscopes. Specifically, we adjusted for age, sex, BMI, and BBPS when analyzing PDR and ADR, and for age, sex, BMI, BBPS, operation type, and diverticulosis when assessing CIR. This approach allowed for a robust and accurate evaluation of the independent effect of sedation on modifiable quality indicators of screening colonoscopy in a real-world clinical setting. However, the absence of data regarding patient comfort and recovery time precludes assessment of sedation-related benefits beyond detection metrics.

We evaluated only the overall effect of sedated colonoscopy on PDR and ADR without conducting subgroup analyses of segment-specific detection rates or differentiating between single and multiple PDRs or ADRs. Additionally, we did not assess the impact of sedation on the detection rate of sessile serrated lesions (SSLs) in the elderly population. SSLs are the second most common precursor lesions to CRC, characterized by a distinct carcinogenic pathway, unique genetic and epidemiologic features, and an unclear relationship with age[29].

Sedation in this study was patient-driven rather than randomized, which may have introduced selection bias. Additionally, withdrawal time, an important factor in colonoscopy quality, was not included owing to the unavailability of data. The retrospective, single-center design of this analysis also limits the generalizability of the findings. Moreover, several potential confounders were not included, such as right-colon second-look practices, standard high-definition white-light vs image-enhanced endoscopy, real-time AI-based automatic polyp detection systems, patient positioning, comfort and satisfaction levels, dosage of propofol and sufentanyl, sedation-related medical complications, and the additional financial burden associated with sedation costs during screening colonoscopy.

We believe that our results contribute important data and a valuable regional perspective to the ongoing discussion on colonoscopy quality metrics and sedation practices in aging populations. However, it remains uncertain whether our single-center retrospective results can be generalized to other settings, such as screening colonoscopies performed by trainee endoscopists, non-gastroenterologists, or among elderly populations from different ethnic groups. Future prospective, multicenter, randomized studies with large, well-balanced cohorts that incorporate multiple potential quality and financial confounders are essential to definitively elucidate the impact of propofol sedation on key performance metrics of screening colonoscopy in the elderly population.

In our mixed cohort of elderly patients undergoing screening and diagnostic colonoscopies, propofol-induced deep sedation did not significantly enhance ADR, PDR, or CIR after adjusting for relevant confounders, although higher BMI and male sex were identified as independent predictors of increased ADR. These results support a flexible, patient-centered approach to sedation choice without compromising procedural quality. Future prospective, multicenter studies with comprehensive adjustment for clinical, procedural, and patient-related confounders are crucial to draw definitive conclusions regarding the role of propofol sedation in colonoscopy performance among the elderly.

| 1. | World Health Organization. Colorectal cancer. [cited 11 July 2023]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/colorectal-cancer. |

| 2. | Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75126] [Cited by in RCA: 68713] [Article Influence: 13742.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (201)] |

| 3. | Ferlay J, Ervik M, Lam F, Colombet M, Mery L, Piñeros M, Znaor A, Soerjomataram I, Bray F. Global Cancer Observatory: Cancer Today. Available from: https://gco.iarc.fr/today. |

| 4. | Yang DX, Gross CP, Soulos PR, Yu JB. Estimating the magnitude of colorectal cancers prevented during the era of screening: 1976 to 2009. Cancer. 2014;120:2893-2901. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Hilsden RJ, Dube C, Heitman SJ, Bridges R, McGregor SE, Rostom A. The association of colonoscopy quality indicators with the detection of screen-relevant lesions, adverse events, and postcolonoscopy cancers in an asymptomatic Canadian colorectal cancer screening population. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;82:887-894. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Rex DK. Key quality indicators in colonoscopy. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf). 2023;11:goad009. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kaminski MF, Wieszczy P, Rupinski M, Wojciechowska U, Didkowska J, Kraszewska E, Kobiela J, Franczyk R, Rupinska M, Kocot B, Chaber-Ciopinska A, Pachlewski J, Polkowski M, Regula J. Increased Rate of Adenoma Detection Associates With Reduced Risk of Colorectal Cancer and Death. Gastroenterology. 2017;153:98-105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 266] [Cited by in RCA: 401] [Article Influence: 44.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Schoenfeld PS, Cohen J. Quality indicators for colorectal cancer screening for colonoscopy(). Tech Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;15:59-68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Barclay RL, Vicari JJ, Doughty AS, Johanson JF, Greenlaw RL. Colonoscopic withdrawal times and adenoma detection during screening colonoscopy. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2533-2541. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 911] [Cited by in RCA: 975] [Article Influence: 48.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Rex DK. Maximizing detection of adenomas and cancers during colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2866-2877. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 186] [Cited by in RCA: 186] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kovacevic M, Rizvanovic N, Sabanovic Adilovic A, Barucija N, Abazovic A. Adenoma Detection Rate in Colonoscopic Screening with Ketamine-based Sedation: A Prospective Observational Study. Medeni Med J. 2022;37:79-84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Wang P, Berzin TM, Glissen Brown JR, Bharadwaj S, Becq A, Xiao X, Liu P, Li L, Song Y, Zhang D, Li Y, Xu G, Tu M, Liu X. Real-time automatic detection system increases colonoscopic polyp and adenoma detection rates: a prospective randomised controlled study. Gut. 2019;68:1813-1819. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 398] [Cited by in RCA: 591] [Article Influence: 84.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kaltenbach T, Gawron A, Meyer CS, Gupta S, Shergill A, Dominitz JA, Soetikno RM, Nguyen-Vu T, A Whooley M, Kahi CJ. Adenoma Detection Rate (ADR) Irrespective of Indication Is Comparable to Screening ADR: Implications for Quality Monitoring. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19:1883-1889.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kaminski MF, Thomas-Gibson S, Bugajski M, Bretthauer M, Rees CJ, Dekker E, Hoff G, Jover R, Suchanek S, Ferlitsch M, Anderson J, Roesch T, Hultcranz R, Racz I, Kuipers EJ, Garborg K, East JE, Rupinski M, Seip B, Bennett C, Senore C, Minozzi S, Bisschops R, Domagk D, Valori R, Spada C, Hassan C, Dinis-Ribeiro M, Rutter MD. Performance measures for lower gastrointestinal endoscopy: a European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) quality improvement initiative. United European Gastroenterol J. 2017;5:309-334. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 195] [Article Influence: 21.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Rex DK, Bond JH, Winawer S, Levin TR, Burt RW, Johnson DA, Kirk LM, Litlin S, Lieberman DA, Waye JD, Church J, Marshall JB, Riddell RH; U. S. Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Quality in the technical performance of colonoscopy and the continuous quality improvement process for colonoscopy: recommendations of the U.S. Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1296-1308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 691] [Cited by in RCA: 736] [Article Influence: 30.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Villa NA, Pannala R, Pasha SF, Leighton JA. Alternatives to Incomplete Colonoscopy. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2015;17:43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Machlab S, Francia E, Mascort J, García-Iglesias P, Mendive JM, Riba F, Guarner-Argente C, Solanes M, Ortiz J, Calvet X. Risks, indications and technical aspects of colonoscopy in elderly or frail patients. Position paper of the Societat Catalana de Digestologia, the Societat Catalana de Geriatria i Gerontologia and the Societat Catalana de Medicina de Familia i Comunitaria. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024;47:107-117. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Cohen LB. Sedation issues in quality colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2010;20:615-627. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Dossa F, Medeiros B, Keng C, Acuna SA, Baxter NN. Propofol versus midazolam with or without short-acting opioids for sedation in colonoscopy: a systematic review and meta-analysis of safety, satisfaction, and efficiency outcomes. Gastrointest Endosc. 2020;91:1015-1026.e7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Thornley P, Al Beshir M, Gregor J, Antoniou A, Khanna N. Efficiency and patient experience with propofol vs conventional sedation: A prospective study. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;8:232-238. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Korman LY, Haddad NG, Metz DC, Brandt LJ, Benjamin SB, Lazerow SK, Miller HL, Mete M, Patel M, Egorov V. Effect of propofol anesthesia on force application during colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;79:657-662. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Radaelli F, Meucci G, Sgroi G, Minoli G; Italian Association of Hospital Gastroenterologists (AIGO). Technical performance of colonoscopy: the key role of sedation/analgesia and other quality indicators. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:1122-1130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 167] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP; STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:573-577. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3559] [Cited by in RCA: 6565] [Article Influence: 345.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE). Preparing a Manuscript for Submission to a Medical Journal. Available from: https://www.icmje.org/recommendations/browse/manuscript-preparation/preparing-for-submission.html. |

| 25. | World Health Organization. Ageing. Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/ageing#tab=tab_1. |

| 26. | Sninsky JA, Shore BM, Lupu GV, Crockett SD. Risk Factors for Colorectal Polyps and Cancer. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2022;32:195-213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 28.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Liang M, Zhang X, Xu C, Cao J, Zhang Z. Anesthesia Assistance in Colonoscopy: Impact on Quality Indicators. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:872231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | GBD 2021 Adult BMI Collaborators. Global, regional, and national prevalence of adult overweight and obesity, 1990-2021, with forecasts to 2050: a forecasting study for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet. 2025;405:813-838. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 391] [Article Influence: 391.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 29. | Zhang C, Cheng Y, Luo D, Wang J, Liu J, Luo Y, Zhou W, Zhuo Z, Guo K, Zeng R, Yang J, Sha W, Chen H. Association between cardiovascular risk factors and colorectal cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;34:100794. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Lei X, Song S, Li X, Geng C, Wang C. Excessive Body Fat at a Young Age Increases the Risk of Colorectal Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutr Cancer. 2021;73:1601-1612. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Wong MC, Chan CH, Cheung W, Fung DH, Liang M, Huang JL, Wang YH, Jiang JY, Yu CP, Wang HH, Wu JC, Chan FK, Sung JJ. Association between investigator-measured body-mass index and colorectal adenoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 168,201 subjects. Eur J Epidemiol. 2018;33:15-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Choe AR, Song EM, Seo H, Kim H, Kim G, Kim S, Byeon JR, Park Y, Tae CH, Shim KN, Jung SA. Different modifiable risk factors for the development of non-advanced adenoma, advanced adenomatous lesion, and sessile serrated lesions, on screening colonoscopy. Sci Rep. 2024;14:16865. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Fakhouri TH, Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of obesity among older adults in the United States, 2007-2010. NCHS Data Brief. 2012;1-8. [PubMed] |

| 34. | Islami F, Goding Sauer A, Miller KD, Siegel RL, Fedewa SA, Jacobs EJ, McCullough ML, Patel AV, Ma J, Soerjomataram I, Flanders WD, Brawley OW, Gapstur SM, Jemal A. Proportion and number of cancer cases and deaths attributable to potentially modifiable risk factors in the United States. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:31-54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 902] [Cited by in RCA: 1042] [Article Influence: 130.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 35. | Roshandel G, Ghasemi-Kebria F, Malekzadeh R. Colorectal Cancer: Epidemiology, Risk Factors, and Prevention. Cancers (Basel). 2024;16:1530. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 186] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 36. | Siegel RL, Miller KD, Goding Sauer A, Fedewa SA, Butterly LF, Anderson JC, Cercek A, Smith RA, Jemal A. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70:145-164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2268] [Cited by in RCA: 3363] [Article Influence: 560.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 37. | Sullivan BA, Noujaim M, Roper J. Cause, Epidemiology, and Histology of Polyps and Pathways to Colorectal Cancer. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2022;32:177-194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 21.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Leufkens AM, van Oijen MG, Vleggaar FP, Siersema PD. Factors influencing the miss rate of polyps in a back-to-back colonoscopy study. Endoscopy. 2012;44:470-475. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 205] [Cited by in RCA: 211] [Article Influence: 15.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 39. | Corley DA, Jensen CD, Marks AR, Zhao WK, Lee JK, Doubeni CA, Zauber AG, de Boer J, Fireman BH, Schottinger JE, Quinn VP, Ghai NR, Levin TR, Quesenberry CP. Adenoma detection rate and risk of colorectal cancer and death. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1298-1306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1251] [Cited by in RCA: 1671] [Article Influence: 139.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 40. | Shaukat A, Holub J, Pike IM, Pochapin M, Greenwald D, Schmitt C, Eisen G. Benchmarking Adenoma Detection Rates for Colonoscopy: Results From a US-Based Registry. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116:1946-1949. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Zhang Q, Dong Z, Jiang Y, Zhan T, Wang J, Xu S. The Impact of Sedation on Adenoma Detection Rate and Cecal Intubation Rate in Colonoscopy. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2020;2020:3089094. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Xu C, Tang D, Xie Y, Ni M, Chen M, Shen Y, Dou X, Zhou L, Xu G, Wang L, Lv Y, Zhang S, Zou X. Sedation Is Associated with Higher Polyp and Adenoma Detection Rates during Colonoscopy: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2023;2023:1172478. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Khan F, Hur C, Lebwohl B, Krigel A. Unsedated Colonoscopy: Impact on Quality Indicators. Dig Dis Sci. 2020;65:3116-3122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Han J, Cao R, Su D, Li Y, Gao C, Wang K, Gao F, Qi X. Sedated Colonoscopy may not be Beneficial for Polyp/Adenoma Detection. Cancer Control. 2024;31:10732748241272482. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Quaye AN, Hisey WM, Mackenzie TA, Robinson CM, Richard JM, Anderson JC, Warters RD, Butterly LF. Association between Colonoscopy Sedation Type and Polyp Detection: A Registry-based Cohort Study. Anesthesiology. 2024;140:1088-1097. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Bannert C, Reinhart K, Dunkler D, Trauner M, Renner F, Knoflach P, Ferlitsch A, Weiss W, Ferlitsch M. Sedation in screening colonoscopy: impact on quality indicators and complications. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1837-1848. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Zhao S, Deng XL, Wang L, Ye JW, Liu ZY, Huang B, Kan Y, Liu BH, Zhang AP, Li CX, Li F, Tong WD. The impact of sedation on quality metrics of colonoscopy: a single-center experience of 48,838 procedures. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2020;35:1155-1161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Cardin F, Andreotti A, Martella B, Terranova C, Militello C. Current practice in colonoscopy in the elderly. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2012;24:9-13. [PubMed] |

| 49. | Lin OS. Performing colonoscopy in elderly and very elderly patients: Risks, costs and benefits. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;6:220-226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Causada-Calo N, Bishay K, Albashir S, Al Mazroui A, Armstrong D. Association Between Age and Complications After Outpatient Colonoscopy. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e208958. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Day LW, Kwon A, Inadomi JM, Walter LC, Somsouk M. Adverse events in older patients undergoing colonoscopy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:885-896. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 211] [Cited by in RCA: 196] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 52. | Rex DK, Schoenfeld PS, Cohen J, Pike IM, Adler DG, Fennerty MB, Lieb JG 2nd, Park WG, Rizk MK, Sawhney MS, Shaheen NJ, Wani S, Weinberg DS. Quality indicators for colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:31-53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 649] [Cited by in RCA: 876] [Article Influence: 79.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Martínez JF, Aparicio JR, Compañy L, Ruiz F, Gómez-Escolar L, Mozas I, Casellas JA. Safety of continuous propofol sedation for endoscopic procedures in elderly patients. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2011;103:76-82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Heuss LT, Schnieper P, Drewe J, Pflimlin E, Beglinger C. Conscious sedation with propofol in elderly patients: a prospective evaluation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:1493-1501. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Schilling D, Rosenbaum A, Schweizer S, Richter H, Rumstadt B. Sedation with propofol for interventional endoscopy by trained nurses in high-risk octogenarians: a prospective, randomized, controlled study. Endoscopy. 2009;41:295-298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Ko CW, Sonnenberg A. Comparing risks and benefits of colorectal cancer screening in elderly patients. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:1163-1170. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Williams GJ, Hellerstedt ST, Scudder PN, Calderwood AH. Yield of Surveillance Colonoscopy in Older Adults with a History of Polyps: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Dig Dis Sci. 2022;67:4059-4069. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Kaan HL, Khor V, Liew WC, Loh TF, Leong SW, Teo SL, Keh CHL. The efficacy of on-demand sedation colonoscopy: a STROBE-compliant retrospective cohort study. Surg Endosc. 2022;36:930-935. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Tarhini H, Alrazim A, Ghusn W, Hosni M, Kerbage A, Soweid A, Sharara AI, Mourad F, Francis F, Shaib Y, Barada K, Daniel F. Impact of sedation type on adenoma detection rate by colonoscopy. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2022;46:101981. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Cadoni S, Falt P, Gallittu P, Liggi M, Smajstrla V, Leung FW. Impact of carbon dioxide insufflation and water exchange on postcolonoscopy outcomes in patients receiving on-demand sedation: a randomized controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85:210-218.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Leung FW, Cheung R, Friedland S, Jacob N, Leung JW, Pan JY, Quan SY, Sul J, Yen AW, Jamgotchian N, Chen Y, Dixit V, Shaikh A, Elashoff D, Saha A, Wilhalme H. Prospective randomized controlled trial of water exchange plus cap versus water exchange colonoscopy in unsedated veterans. Gastrointest Endosc. 2025;101:402-413.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Lee TJ, Rees CJ, Blanks RG, Moss SM, Nickerson C, Wright KC, James PW, McNally RJ, Patnick J, Rutter MD. Colonoscopic factors associated with adenoma detection in a national colorectal cancer screening program. Endoscopy. 2014;46:203-211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/