Published online Dec 5, 2025. doi: 10.4292/wjgpt.v16.i4.111977

Revised: August 13, 2025

Accepted: November 13, 2025

Published online: December 5, 2025

Processing time: 144 Days and 2.5 Hours

Chronic pancreatitis is a progressive, debilitating condition with no standardized treatment. Pirfenidone and simvastatin are potential therapeutic agents that exert anti-inflammatory and antifibrotic effects on pancreatic acinar cells.

To evaluate the synergistic effects of pirfenidone and simvastatin in an L-arginine-induced chronic pancreatitis model in mice.

A preclinical, 7-week study was performed using a mouse model of L-arginine-induced chronic pancreatitis. The mice were divided into five groups: Normal control; model control; pirfenidone-treated; simvastatin-treated; and combination-treated (pirfenidone + simvastatin). Treatment started in week 3 after disease induction. Mice were euthanized at weeks 4 and 7 for blood collection and tissue sampling for histological and biomarker analysis, including cytokines, oxidative stress markers, and indicators of fibrosis.

Combination therapy significantly reduced levels of tumor necrosis factor-alpha (11.10 ± 1.57 pg/mL vs 24.30 ± 2.00 pg/mL), interleukin-10 (11.70 ± 1.12 pg/mL vs 19.60 ± 1.27 pg/mL), and transforming growth factor-beta 1 (236.13 ± 6.95 pg/mL vs 550.52 ± 42.18 pg/mL) at week 7 (P < 0.05 vs model control). The glutathione peroxidase 1 level increased across all treatment groups, significantly in the pirfenidone-treated group (5.47 ± 0.34 IU/mL vs 5.04 ± 0.43 IU/mL; P < 0.05). Lipid peroxidation levels decreased significantly in the combination-treated group (111.87 ± 7.36 mmol/mL vs 192.85 ± 0.98 mmol/mL; P < 0.05). Histology revealed extensive collagen accumulation and damage to the exocrine pancreas in the model control group (vs treatment groups). Combination therapy elicited the least damage.

Combination of pirfenidone and simvastatin demonstrated a synergistic therapeutic effect in reducing inflammation, fibrosis, and oxidative stress in an L-arginine-induced chronic pancreatitis mouse model, suggesting promise for chronic pancreatitis management.

Core Tip: Combination therapy with pirfenidone and simvastatin significantly attenuated inflammation, fibrosis, and oxidative stress in an L-arginine-induced mouse model of chronic pancreatitis. The synergistic action led to reduced tumor necrosis factor-alpha, transforming growth factor-beta 1, and lipid peroxidation levels, along with a preservation of pancreatic tissue architecture. The combination therapy also enhanced antioxidant defense as evidenced by increased glutathione peroxidase 1 activity, indicating mitigation of oxidative damage. These findings highlighted a promising strategy targeting multiple pathological pathways, namely inflammatory, fibrotic, and oxidative stress mechanisms, and supported further evaluation of this combination in translational and clinical studies for chronic pancreatitis.

- Citation: Mehta R, Patel A, Vyas B, Desai B, Adhvaryu D, Sojitra P, Bhuptani S. L-arginine-induced chronic pancreatitis in mice: Evaluating effects of pirfenidone and simvastatin. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther 2025; 16(4): 111977

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2150-5349/full/v16/i4/111977.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4292/wjgpt.v16.i4.111977

Chronic pancreatitis is characterized by inflammation, acinar atrophy, and fibrosis in the pancreas, all of which lead to irreversible damage and a decline in pancreatic functions[1,2]. The prevalence of chronic pancreatitis is increasing, and there is an urgent need for innovative therapeutic strategies to alleviate symptoms and halt disease progression[3,4].

Pirfenidone is approved by the Food and Drug Administration for treatment of pulmonary fibrosis. It has shown promising efficacy in preclinical studies for acute and chronic pancreatitis[5,6]. Similarly, a class of cholesterol-lowering medications, statins, have demonstrated notable anti-inflammatory properties. Simvastatin showed protective effects on pancreatic acinar cells in acute pancreatitis[7-9]. While the respective potentials of pirfenidone and simvastatin have been explored individually in numerous in vivo models, their synergistic effect remains unknown.

The present study investigated the combined therapeutic potential of pirfenidone and simvastatin in a well-established L-arginine-induced chronic pancreatitis model[10]. By evaluating their impact on inflammatory markers, cytokines, fibrotic markers, and antioxidant levels, this study provided a comprehensive understanding of the synergistic effects of these two drugs in mitigating the multifaceted challenges posed by chronic pancreatitis.

Male C57BL/6 mice, aged 6-8 weeks and weighing 20-25 g, were obtained from the Institutional Animal Facility. The animals were housed under standard laboratory conditions (22 ± 2 °C, 55% ± 5% humidity, 12-hour light/dark cycle) with ad libitum access to food and water. All experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Ethics Committee and conducted in accordance with national guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals.

Chronic pancreatitis was induced in the mice via intraperitoneal injection of Larginine hydrochloride (SigmaAldrich, St Louis, MO, United States) administered intraperitoneally (i.p.) at 4.50 g/kg, 2 doses at 1-hour intervals for week 1; i.p. 4.60 g/kg, 2 doses at 1-hour intervals for week 2; and i.p. 4.75 g/kg, 2 doses at 1-hour intervals for weeks 3 and 4. The Larginine had been dissolved in sterile 0.9% NaCl (pH 7.4) immediately prior to use. Pirfenidone was administered by oral gavageat 400 mg/kg. It had been prepared in warm normal saline to enhance solubility. Simvastatin was given orally by gavageat 1 mg/kg. It had been suspended in water and sonicated prior to use to improve dissolution as described in previous rodent studies. The selected simvastatin dose of 1 mg/kg was based on previously published studies demonstrating efficacy in various fibrotic and inflammatory disease models[6,7]. While higher doses (e.g., 5-20 mg/kg) have been explored, they have shown frequent association with increased risk of hepatotoxicity and off-target effects in mice, particularly in long-term studies. Simvastatin undergoes extensive first-pass hepatic metabolism and lower doses more accurately reflect human therapeutic exposure when adjusted using interspecies allometric scaling. Thus, the chosen regimen balances safety with pharmacological relevance. Future pharmacokinetic and dose-optimization studies will be essential to strengthen the translational applicability of this dosing strategy.

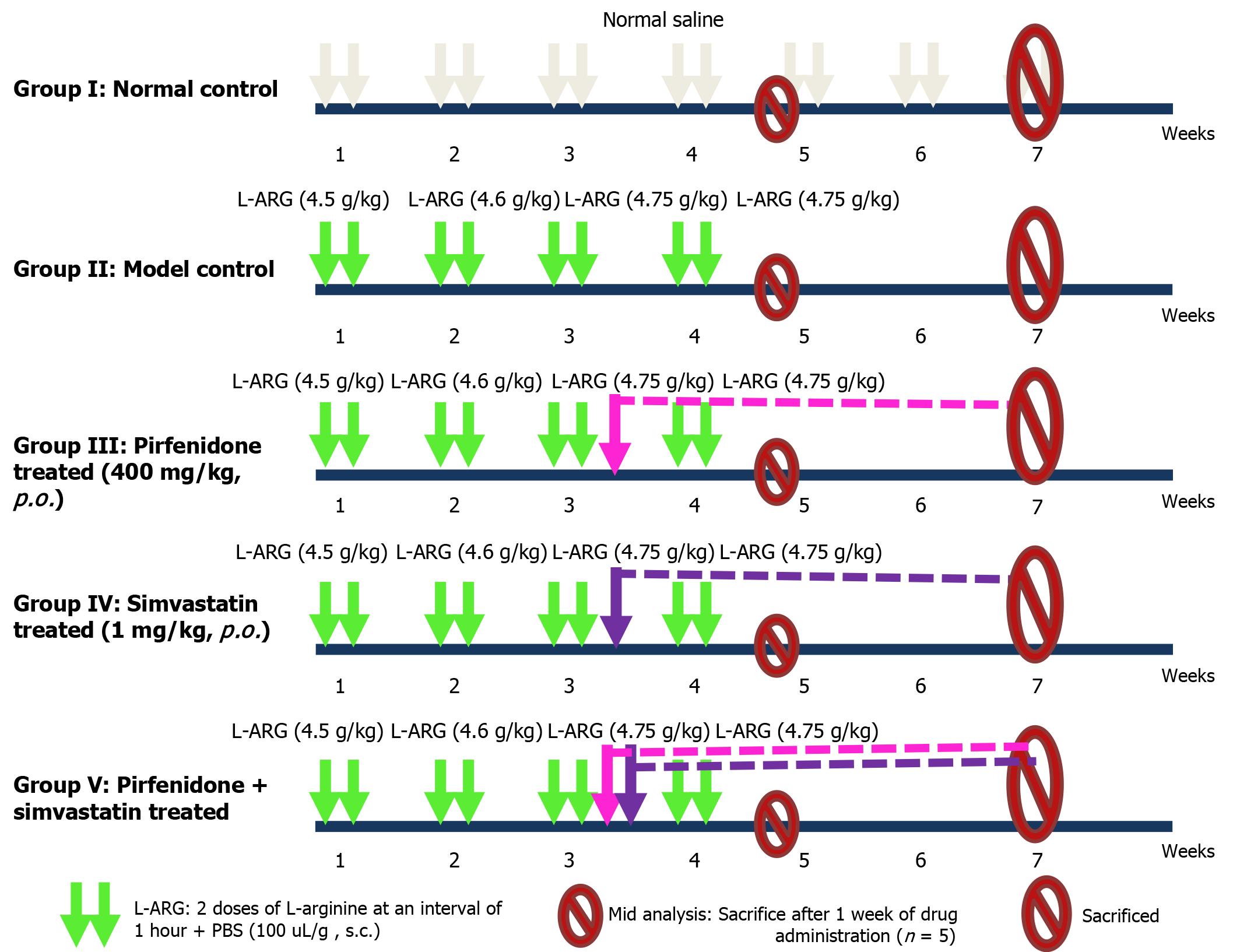

A total of 48 mice were used for the study and were divided into five groups as shown in Table 1 and Figure 1.

| Animal group | Treatment |

| I: Normal control group (n = 8) | Normal saline |

| II: Model control group (n = 10) | L-arginine administered: i.p. 4.50 g/kg, 2 doses at 1-hour intervals for week 1; i.p. 4.60 g/kg, 2 doses at 1-hour intervals for week 2; and i.p. 4.75 g/kg, 2 doses at 1-hour intervals for weeks 3 and 4 |

| III: Pirfenidone-treated group (n = 10) | L-arginine administered: i.p. 4.50 g/kg, 2 doses at 1-hour intervals for week 1; i.p. 4.60 g/kg, 2 doses at 1-hour intervals for week 2; and i.p. 4.75 g/kg, 2 doses at 1-hour intervals for weeks 3 and 4. Pirfenidone administered: p.o. 400mg/kg, from week 3 |

| IV: Simvastatin-treated group (n = 10) | L-arginine administered: i.p. 4.50 g/kg, 2 doses at 1-hour intervals for week 1; i.p. 4.60 g/kg, 2 doses at 1-hour intervals for week 2; and i.p. 4.75 g/kg, 2 doses at 1-hour intervals for weeks 3 and 4. Simvastatin administered: p.o. 1 mg/kg, for weeks 3-7 |

| V: Pirfenidone + simvastatin-treated group (n = 10) | L-arginine administered: i.p. 4.50 g/kg, 2 doses at 1-hour intervals for week 1; i.p. 4.60 g/kg, 2 doses at 1-hour intervals for week 2; and i.p. 4.75 g/kg, 2 doses at 1-hour intervals for weeks 3 and 4. Pirfenidone administered: p.o. 400 mg/kg, for weeks 3-7; Simvastatin administered; p.o. 1mg/kg, for weeks 3-7 |

| Total animals | 48 |

After grouping, the animals were acclimatized for 1 week before the study was initiated. Dosing was performed per the dosing schedule described in Figure 1. Upon completion of weeks 4 and 7 of treatment, representative animals from each group were euthanized via over-anesthetization using a high dose of anesthetic agent. Resected pancreatic tissues were stored in formalin for histopathological study. In addition, whole pancreatic tissue samples were stored at -20 °C for assessment of fibrotic markers and the intrapancreatic modulation of cytokine activity (Table 2).

| Histopathological changes | Scoring | ||||

| NC | MC | Pir | Sim | Pir + sim | |

| Inflammatory cell infiltration | 0 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Congestion | 0 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Fatty replacement of exocrine pancreas | 0 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Areas of abnormal pancreatic tissue architecture from the total parenchyma1 | 01 | 31 | 21 | 11 | 11 |

| Glandular atrophy | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Fibrosis/collagen deposition in exocrine pancreas (Masson’s trichome stain) | 0 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Distortion/degeneration of exocrine pancreas | 0 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

At the end of the treatment period, representative mice were first anesthetized using isoflurane and then euthanized by anesthetic overdose. Blood samples were collected via cardiac puncture, and serum was separated by centrifugation at 3000 rpm for 15 minutes. The pancreas was excised rapidly, rinsed in cold saline, and divided into portions for histopathological, biochemical, and molecular analyses. Tissue samples were collected from all surviving animals at endpoint without selection bias.

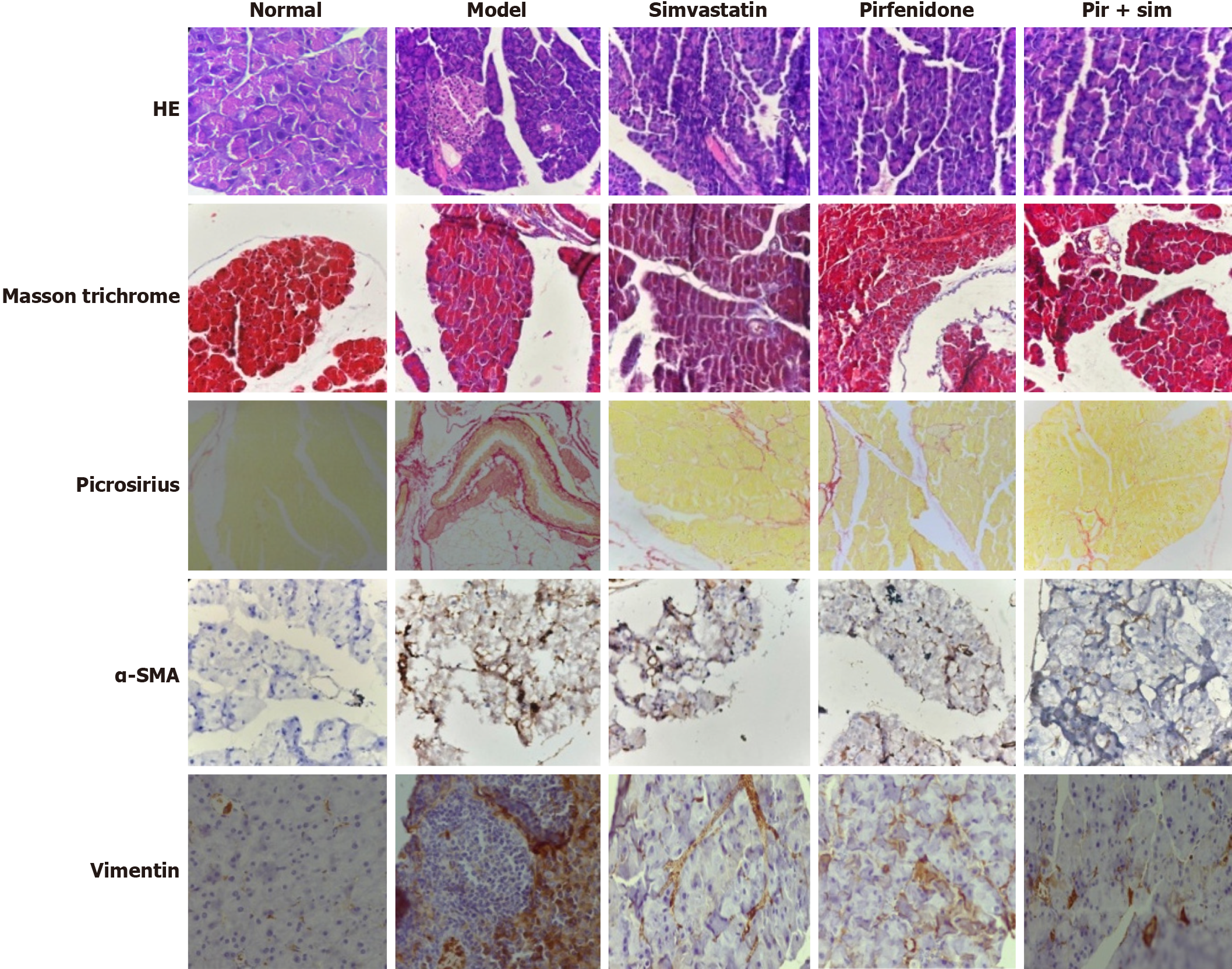

Pancreatic tissue samples were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned at a thickness of 4 µm. Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin to assess general morphology, Masson’s trichrome to evaluate collagen deposition and fibrosis, and Picrosirius Red stain to visualize collagen fiber structure under polarized light. For immunohistochemistry, additional sections were processed using antibodies against vimentin and alpha-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) to detect activated mesenchymal cells and myofibroblasts, respectively. Vimentin and α-SMA are both key indicators of fibrotic remodeling in chronic pancreatitis.

All stained slides were mounted using dibutyl phthalate polystyrene xylene, air-dried, and examined under a light microscope. The extent and severity of histological damage were graded using a semi-quantitative scoring system described by Demols et al[11]. The scoring system is widely accepted for evaluating chronic pancreatitis in experimental models.

The grading involved assessment of overall pancreatic architecture, in which a score of 0 indicated no abnormalities, 1 indicated rare lesions, 2 denoted mild involvement affecting less than 10% of the pancreatic parenchyma, 3 signified moderate damage involving less than 50%, and 4 reflected extensive damage affecting more than 50%. Within these affected areas, three pathological features were specifically evaluated: Glandular atrophy, indicating loss or shrinkage of acinar cells, was graded from 0 (absent) to 3 (severe); pseudo-tubular complexes, representing abnormal duct-like structures formed during tissue remodeling, were graded from 0 (absent) to 3 (extensive); and fibrosis or scar tissue deposition was scored as 0 if absent, 2 if limited to localized areas, and 4 if diffusely spread throughout the pancreatic tissue. Images from each slide were quantified for the extent of fibrosis using ImageJ software (La Jolla, CA, United States).

Serum levels of amylase and lipase were quantified using commercially available assay kits (Sigma-Aldrich) following the manufacturer’s protocols. For tissue-based analyses, pancreatic samples were homogenized in ice-cold PBS and centrifuged at 12000 rpm for 10 minutes at 4 °C. The resulting supernatants were collected for the assessment of molecular markers.

Proinflammatory cytokine tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and anti-inflammatory cytokine interleukin (IL)-10 were measured using ELISA kits (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, United States). Fibrotic markers, including transforming growth factor-beta 1 (TGF-β1), were quantified similarly. To evaluate oxidative stress status, glutathione peroxidase (GPx1) (antioxidant marker) and lipid peroxidation (LPO; an oxidative damage marker) were measured using ELISA-based colorimetric assays. All samples were analyzed in duplicate to ensure accuracy and reproducibility.

Data were expressed as mean ± SD. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test for multiple comparisons. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

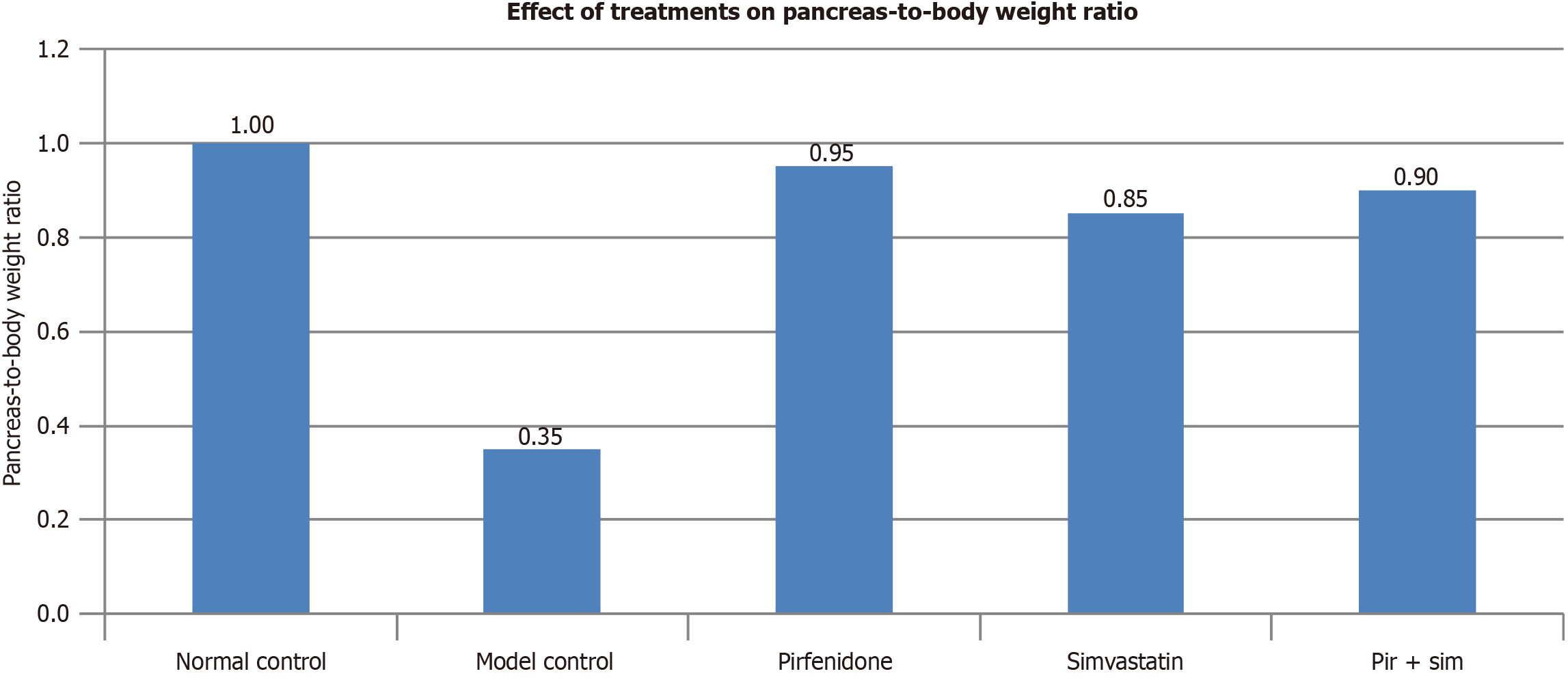

The model control group (L-arginine-induced chronic pancreatitis) exhibited a marked reduction in the pancreas-to-body weight ratio (pancreatic index), indicating pancreatic atrophy and tissue damage. The groups treated with pirfenidone, simvastatin, and the combination treatment demonstrated ratios comparable with the normal control group, suggesting a protective or restorative effect of these interventions on pancreatic integrity (Figure 2).

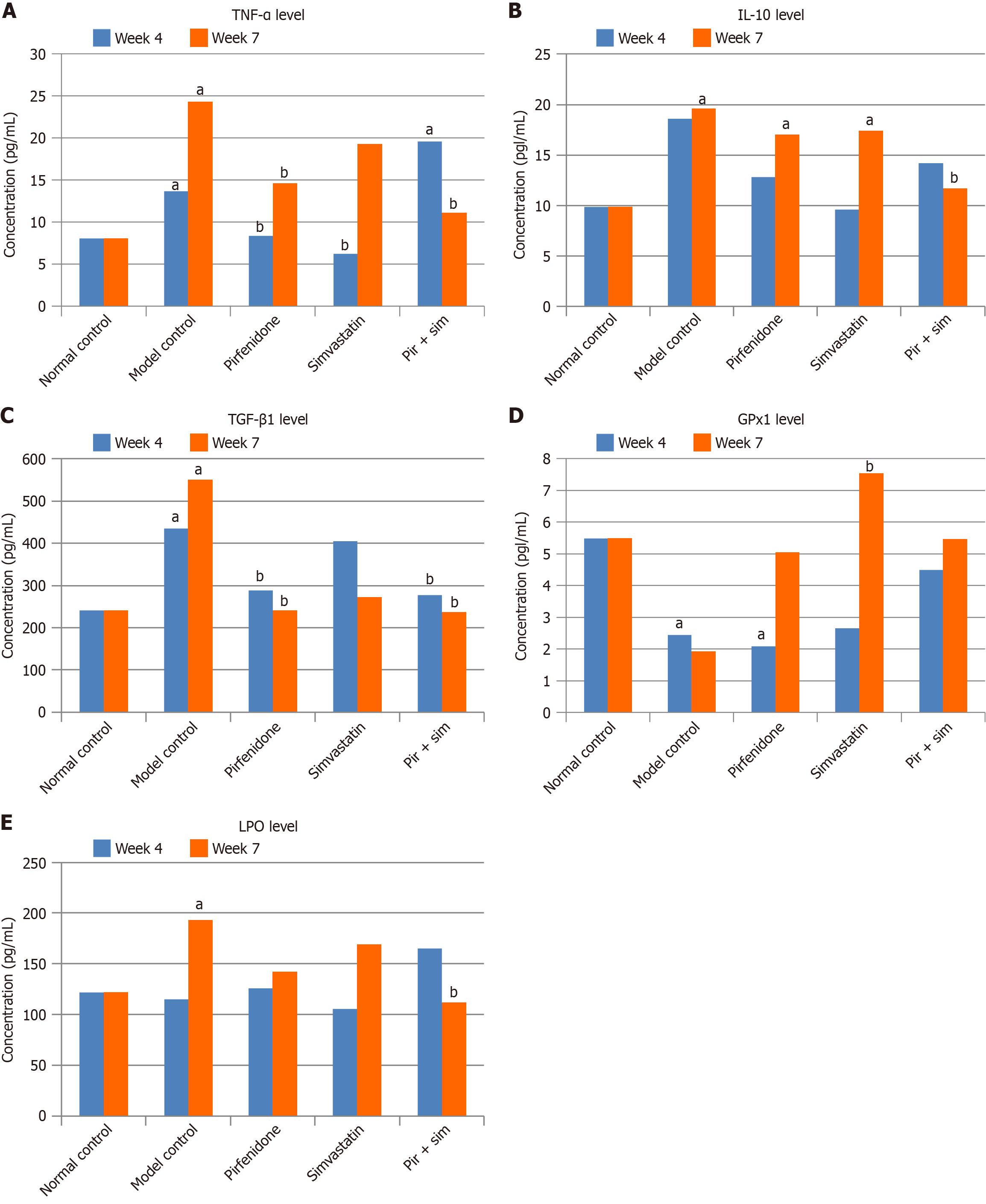

The anti-inflammatory efficacy of pirfenidone and simvastatin in chronic pancreatitis was evaluated by measuring pancreatic tissue levels of TNF-α. As shown in Figure 3A and Table 3, the L-arginine-induced model control group demonstrated a significant increase in TNF-α levels at week 4 (13.70 ± 0.07 pg/mL) and week 7 (24.30 ± 2.01 pg/mL) compared with the normal control (8.07 ± 0.36 pg/mL at both time points). Pirfenidone treatment resulted in a significant reduction in TNF-α at week 4 (8.37 ± 0.74 pg/mL) and week 7 (14.60 ± 1.42 pg/mL) compared with the model group. Simvastatin-treated mice showed a substantial reduction at week 4 (6.25 ± 0.26 pg/mL) but levels increased by week 7 (19.30 ± 0.29 pg/mL). However, these levels were below that of the model control group. The combination-treated group showed an initial elevation at week 4 (19.60 ± 3.30 pg/mL), possibly reflecting transient immunological modulation. There was a significant decline at week 7 (11.10 ± 1.57 pg/mL), indicating a delayed but synergistic anti-inflammatory effect.

| Animal group | TNF-α in pg/mL | IL-10 in pg/mL | TGF-β1 in pg/mL | GPx-1 in IU/mL | LPO in mmol/mL | |||||

| Week 4 | Week 7 | Week 4 | Week 7 | Week 4 | Week 7 | Week 4 | Week 7 | Week 4 | Week 7 | |

| Normal control | 8.07 ± 0.36 | 8.07 ± 0.36 | 9.85 ± 0.30 | 9.85 ± 0.50 | 240.73 ± 14.86 | 240.73 ± 8.71 | 5.48 ± 0.92 | 5.48 ± 0.92 | 122.19 ± 5.88 | 122.19 ± 5.88 |

| Model control | 13.70 ± 0.07 | 24.30 ± 2.01 | 18.60 ± 3.25 | 19.60 ± 1.27 | 434.91 ± 53.19 | 550.52 ± 42.18 | 2.44 ± 0.42 | 1.92 ± 0.21 | 114.82 ± 3.91 | 192.85 ± 0.98 |

| Pirfenidone | 8.37 ± 0.74 | 14.60 ± 1.42 | 12.80 ± 0.09 | 17.00 ± 1.37 | 288.95 ± 18.90 | 241.34 ± 20.45 | 2.08 ± 0.09 | 5.04 ± 0.43 | 126.18 ± 6.83 | 142.14 ± 1.60 |

| Simvastatin | 6.25 ± 0.26 | 19.30 ± 0.29 | 9.61 ± 0.27 | 17.40 ± 0.29 | 405.43 ± 19.30 | 273.43 ± 8.72 | 2.65 ± 0.06 | 7.54 ± 0.53 | 105.69 ± 12.50 | 169.16 ± 25.30 |

| Pir + sim | 19.60 ± 3.30 | 11.10 ± 1.57 | 14.20 ± 0.28 | 11.70 ± 1.12 | 277.10 ± 21.02 | 236.13 ± 6.95 | 4.50 ± 0.24 | 5.47 ± 0.34 | 164.84 ± 7.78 | 111.87 ± 7.36 |

At week 4, the IL-10 level in the model control group (18.60 ± 3.25 pg/mL) were higher than that in the normal control group (9.85 ± 0.30 pg/mL) (Figure 3B). This increase was not statistically significant (P > 0.05). Neither the individual treatment groups nor the combination-treated groups showed significant changes in IL-10 levels compared with the normal and model control groups. However, by week 7 IL-10 levels increased significantly (P < 0.05) in the model control (19.60 ± 1.27 pg/mL), pirfenidone-treated (17.00 ± 1.37 pg/mL), and simvastatin-treated (17.40 ± 0.29 pg/mL) groups compared with the normal control group (9.85 ± 0.50 pg/mL). Notably, the combination-treated group exhibited a significant (P < 0.05) decrease in IL-10 levels compared with the model control group (11.70 ± 1.12 pg/mL vs 19.60 ± 1.27 pg/mL).

The fibrotic marker TGF-β1 was significantly elevated in the model control group by week 7 compared with the normal control group (550.52 ± 42.18 pg/mL vs 240.73 ± 8.71 pg/mL; P < 0.05), indicating progressive fibrosis (Figure 3C). The pirfenidone-treated and combination-treated groups exhibited significantly reduced TGF-β1 levels at weeks 4 and 7 compared with the model control group (pirfenidone: 288.95 ± 18.90 pg/mL and 241.34 ± 20.45 pg/mL; pirfenidone + simvastatin: 277.10 ± 21.02 pg/mL and 236.13 ± 6.95 pg/mL; P < 0.05). Although TGF-β1 levels in the simvastatin-treated group decreased, the change was not statistically significant. As illustrated in Table 4, the area of fibrosis/collagen deposition in the exocrine pancreas was 75% less in the combination-treated group (3.97%) compared with the model control group (18.88%).

| Area | Normal control | Model control | Pirfenidone + simvastatin | Simvastatin-treated | Pirfenidone-treated |

| Average | 2.21% | 18.88% | 3.99% | 8.66% | 6.81% |

As illustrated in Figure 3D, the model control group exhibited significantly lower GPx1 activity at week 4 (2.44 ± 0.42 IU/mL) and week 7 (1.92 ± 0.21 IU/mL) compared with the normal control (5.48 ± 0.92 IU/mL), indicating oxidative damage. The pirfenidone-treated and combination-treated groups showed moderate restoration of GPx1 levels by week 7. However, the simvastatin-treated group demonstrated a statistically significant (P < 0.05) increase in GPx1 activity at week 7 (7.54 ± 0.53 IU/mL), highlighting its potent antioxidant effect.

Figure 3E shows that by week 7 the model control group had a significantly elevated LPO level (192.85 ± 0.98 mmol/mL) compared with the normal control group (122.19 ± 5.88 mmol/mL), reflecting increased oxidative stress. Combination treatment significantly reduced LPO levels (111.87 ± 7.36 mmol/mL; P < 0.05). Pirfenidone and simvastatin individually showed a downward trend, although it was not statistically significant.

Histological evaluation of pancreatic tissue demonstrated marked architectural disruption and extensive degeneration of the exocrine compartment in the model control group as visualized by hematoxylin and eosin staining (Figure 4). In contrast, treatment with pirfenidone, simvastatin, and particularly the combination led to notable preservation of pancreatic structure. The model control group exhibited intense fibrotic remodeling on Masson’s trichrome and Picrosirius Red staining, while the treatment groups showed reduced fibrosis. The most significant attenuation was observed in the combination therapy group. These findings aligned with the known antifibrotic action of pirfenidone and suggested a synergistic benefit when combined with simvastatin. Immunohistochemical staining for vimentin and α-SMA, which are markers of activated pancreatic stellate cells, supported these observations. Expression levels of both markers were substantially lower in the treatment groups, especially in the combination-treated group, indicating reduced activation of fibrogenic pathways.

This study adopted a multifaceted approach by assessing cytokine levels, oxidative stress markers, and histopathology to evaluate the synergistic effects of pirfenidone and simvastatin in an L-arginine-induced chronic pancreatitis model. The marked decline in GPx1 Levels in the model control group supported the reliability of the model in mimicking chronic pancreatitis. Consistent histopathological evidence of pancreatic damage and reduced tissue mass in the model control group further validated successful disease induction. Additionally, the decline in the pancreatic index highlighted the effectiveness of the model in replicating chronic pancreatitis pathology.

TNF-α levels significantly decreased by week 7 in the combination-treated animals, indicating a strong anti-inflammatory and antifibrotic effect. Pirfenidone monotherapy showed consistent TNFα suppression at both weeks 4 and 7, while simvastatin was effective only at week 4. Prior studies have demonstrated pirfenidone and simvastatin reducing TNFα in pancreatic inflammation models[12-14], showing consistency in the effects of the two drugs. The transient rise in TNFα in the combination-treated group at week 4 may reflect early injury or delayed drug response. Ultimately, this transient rise may reflect early immune activation or variability in pharmacodynamic responses. On the other hand, the delayed suppression observed by week 7 supports the possibility of time-dependent immunomodulatory synergy between pirfenidone and simvastatin. Finally, the marked reduction by week 7 highlighted the long-term therapeutic potential of the combination.

IL-10 levels progressively increased in the model control group by week 7, showing consistency with its established role as a late-phase counter-regulatory cytokine. Notably, pirfenidone and simvastatin monotherapies also resulted in elevated IL-10 levels at week 7, suggesting their ability to promote an anti-inflammatory milieu[13,14]. Interestingly, the combination-treated group demonstrated a significant reduction in IL-10 levels compared with the model control group, indicating a more effective and earlier suppression of inflammation and reducing IL-10 upregulation. This unique pattern could reflect a synergistic effect of the combination therapy, leading to faster resolution of pancreatic injury and offering a novel insight into its mechanism of action.

IL-10 is a key anti-inflammatory cytokine that suppresses inflammation and limits fibrosis. Demols et al[11] demon

GPx1 levels were significantly reduced in the model control group, indicating impaired antioxidant defense and elevated oxidative stress. Simvastatin monotherapy significantly restored GPx1 levels by week 7, consistent with earlier findings by Matalka et al[16]. Those authors had reported enhanced GPx1 and glutathione S-transferase activity and reduced LPO in simvastatin-treated rats with L-arginine-induced pancreatitis. The combination-treated group showed an increasing trend in GPx1 levels at weeks 4 and 7. This trend, however, was not statistically significant, likely due to the limited sample size.

LPO level was elevated in the model group by week 7 but lower in all treatment arms, particularly in the combination-treated group, indicating reduced oxidative stress. While not statistically significant, these trends highlight the anti

Our histological findings support the antifibrotic efficacy of pirfenidone[5,16] and suggest that its combination with simvastatin may further enhance pancreatic tissue recovery by attenuating pancreatic stellate cell activation and fibrogenesis in chronic pancreatitis.

The 7-week L-arginine-induced protocol has been used widely in preclinical studies to replicate the histological and biochemical features of chronic pancreatitis[9-11]. Nevertheless, we recognize that this period may not fully mimic the protracted course of human disease. Based on existing literature and our institutional experience, female C57BL/6 mice exhibit higher baseline mortality in response to repeated L-arginine administration, which could compromise study consistency. Thus, we used male mice exclusively in order to minimize mortality and biological variability. Moreover, simvastatin's anti-inflammatory effects may be short-lived in this model or at the dose used, and future studies should explore dose titration and pharmacokinetics as they relate to sustainment of cytokine suppression. We also acknowledge that this study did not include mechanistic investigations, such as gene or protein expression profiling; there is a need for future studies focused on mechanistic insights, particularly involving the NF-κB signaling pathway, which is known to regulate inflammation and fibrosis in chronic pancreatitis.

The combination of pirfenidone and simvastatin showed significant promise in treating chronic pancreatitis. The combination treatment effectively reduced inflammation, fibrosis, and oxidative stress. Although the study demonstrated the beneficial effects of the combination therapy, it did not fully elucidate the underlying mechanisms driving these effects. Future research should focus on exploring the specific pathways and interactions between pirfenidone and simvastatin that contribute to their combined efficacy.

| 1. | Lew D, Afghani E, Pandol S. Chronic Pancreatitis: Current Status and Challenges for Prevention and Treatment. Dig Dis Sci. 2017;62:1702-1712. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kleeff J, Whitcomb DC, Shimosegawa T, Esposito I, Lerch MM, Gress T, Mayerle J, Drewes AM, Rebours V, Akisik F, Muñoz JED, Neoptolemos JP. Chronic pancreatitis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3:17060. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 255] [Cited by in RCA: 332] [Article Influence: 36.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Pham A, Forsmark C. Chronic pancreatitis: review and update of etiology, risk factors, and management. F1000Res. 2018;7:F1000 Faculty Rev-F1000 Faculty 607. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Garg PK, Narayana D. Changing phenotype and disease behaviour of chronic pancreatitis in India: evidence for gene-environment interactions. Glob Health Epidemiol Genom. 2016;1:e17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Palathingal Bava E, George J, Iyer S, Sahay P, Tarique M, Jain T, Vaish U, Giri B, Sharma P, Saluja AK, Dawra RK, Dudeja V. Pirfenidone ameliorates chronic pancreatitis in mouse models through immune and cytokine modulation. Pancreatology. 2022;22:553-563. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Palathingal Bava E, Tarique M, Iyer S, Sahay P, Dawra R, Saluja A, Dudeja V. Pirfenidone Alleviates Features of Well-Established Chronic Pancreatitis in Mouse Models. Am J Clin Pathol. 2020;154:S74-S74. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Boyd AR, Hinojosa CA, Rodriguez PJ, Orihuela CJ. Impact of oral simvastatin therapy on acute lung injury in mice during pneumococcal pneumonia. BMC Microbiol. 2012;12:73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Wu BU, Pandol SJ, Liu IL. Simvastatin is associated with reduced risk of acute pancreatitis: findings from a regional integrated healthcare system. Gut. 2015;64:133-138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Almeida JL, Sampietre SN, Mendonça Coelho AM, Trindade Molan NA, Machado MC, Monteiro da Cunha JE, Jukemura J. Statin pretreatment in experimental acute pancreatitis. JOP. 2008;9:431-439. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Garg SK, Dawra R, Barlass U, Yuan Z, Dixit AK, Saluja A. Sa1792 Development of a New Mouse Model of Chronic Pancreatitis Induced by Administration of L-Arginine. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:S-297. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 11. | Demols A, Van Laethem JL, Quertinmont E, Degraef C, Delhaye M, Geerts A, Deviere J. Endogenous interleukin-10 modulates fibrosis and regeneration in experimental chronic pancreatitis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2002;282:G1105-G1112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Binker MG, Binker-Cosen AA, Richards D, Gaisano HY, de Cosen RH, Cosen-Binker LI. Chronic stress sensitizes rats to pancreatitis induced by cerulein: role of TNF-α. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:5565-5581. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Grattendick KJ, Nakashima JM, Feng L, Giri SN, Margolin SB. Effects of three anti-TNF-alpha drugs: etanercept, infliximab and pirfenidone on release of TNF-alpha in medium and TNF-alpha associated with the cell in vitro. Int Immunopharmacol. 2008;8:679-687. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Piplani H, Marek-Iannucci S, Sin J, Hou J, Takahashi T, Sharma A, de Freitas Germano J, Waldron RT, Saadaeijahromi H, Song Y, Gulla A, Wu B, Lugea A, Andres AM, Gaisano HY, Gottlieb RA, Pandol SJ. Simvastatin induces autophagic flux to restore cerulein-impaired phagosome-lysosome fusion in acute pancreatitis. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2019;1865:165530. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Palathingal Bava E, George J, Tarique M, Iyer S, Sahay P, Gomez Aguilar B, Edwards DB, Giri B, Sethi V, Jain T, Sharma P, Vaish U, C Jacob HK, Ferrantella A, Maynard CL, Saluja AK, Dawra RK, Dudeja V. Pirfenidone increases IL-10 and improves acute pancreatitis in multiple clinically relevant murine models. JCI Insight. 2022;7:e141108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Matalka II, Mhaidat NM, Fatlawi LA. Antioxidant activity of simvastatin prevents L-arginine-induced acute toxicity of pancreas. Int J Physiol Pathophysiol Pharmacol. 2013;5:102-108. [PubMed] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/