Published online Dec 5, 2025. doi: 10.4292/wjgpt.v16.i4.111889

Revised: August 15, 2025

Accepted: November 10, 2025

Published online: December 5, 2025

Processing time: 146 Days and 22.1 Hours

External gastrointestinal fistulas (EGIFs) are serious postoperative complications associated with prolonged hospital stays, sepsis, malnutrition, and high mortality rates. Reducing gastrointestinal secretions with somatostatin or its analogues may facilitate fistula closure. The clinical effectiveness of these therapies, however, re

To investigate the effectiveness of somatostatin-based therapy for EGIFs.

A systematic review and meta-analysis (Prospero CRD420251054344) of nine randomized controlled trials (442 patients) compared somatostatin-based thera

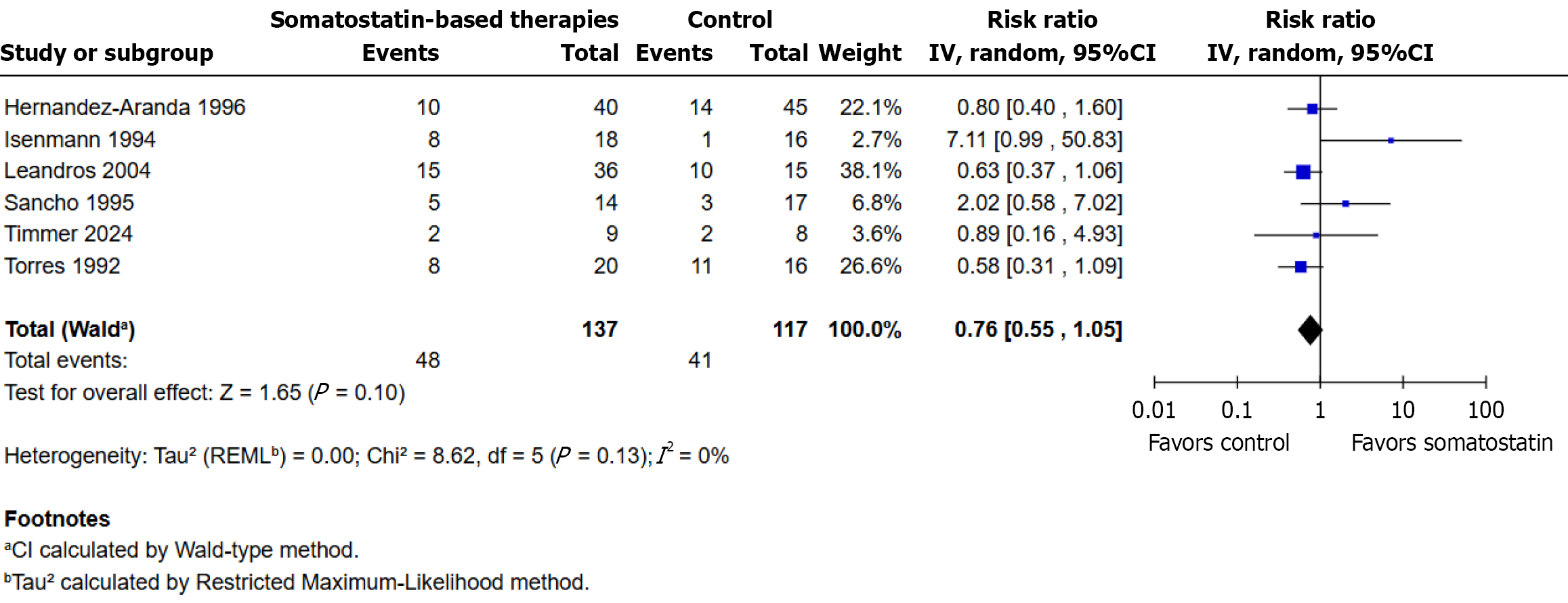

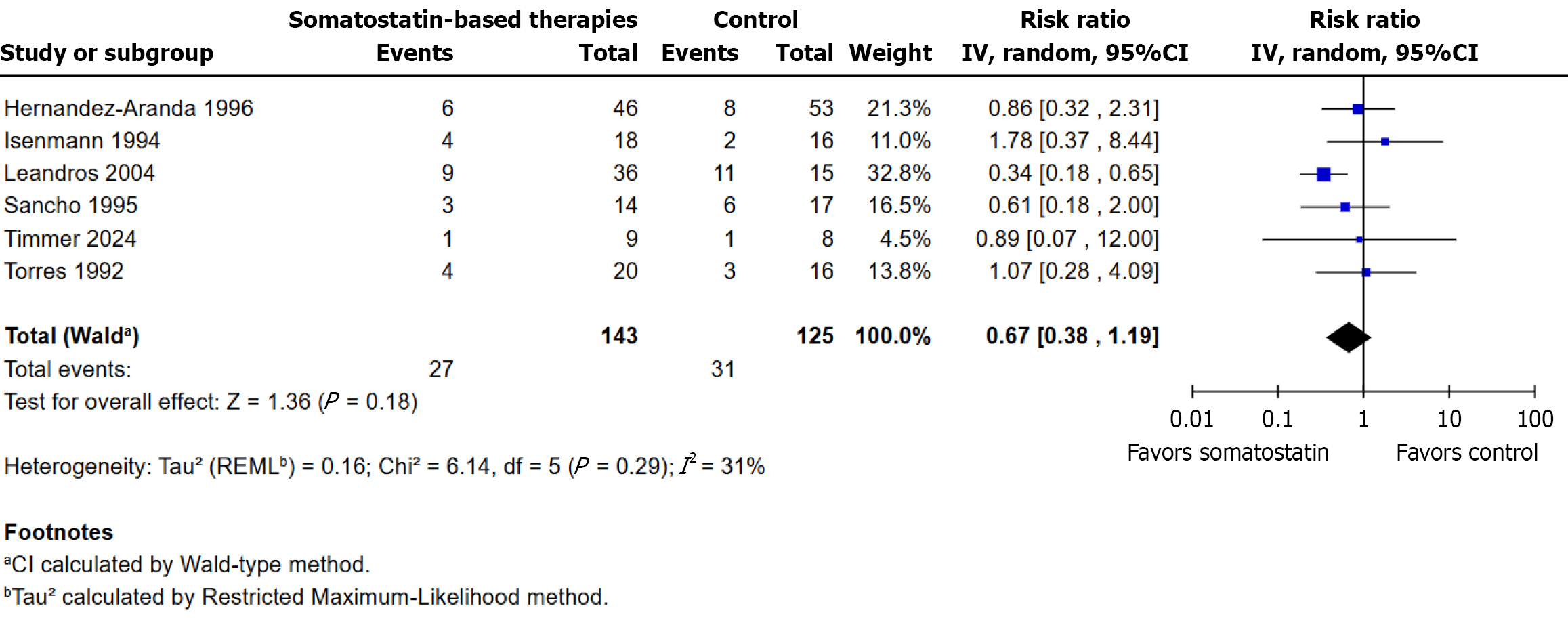

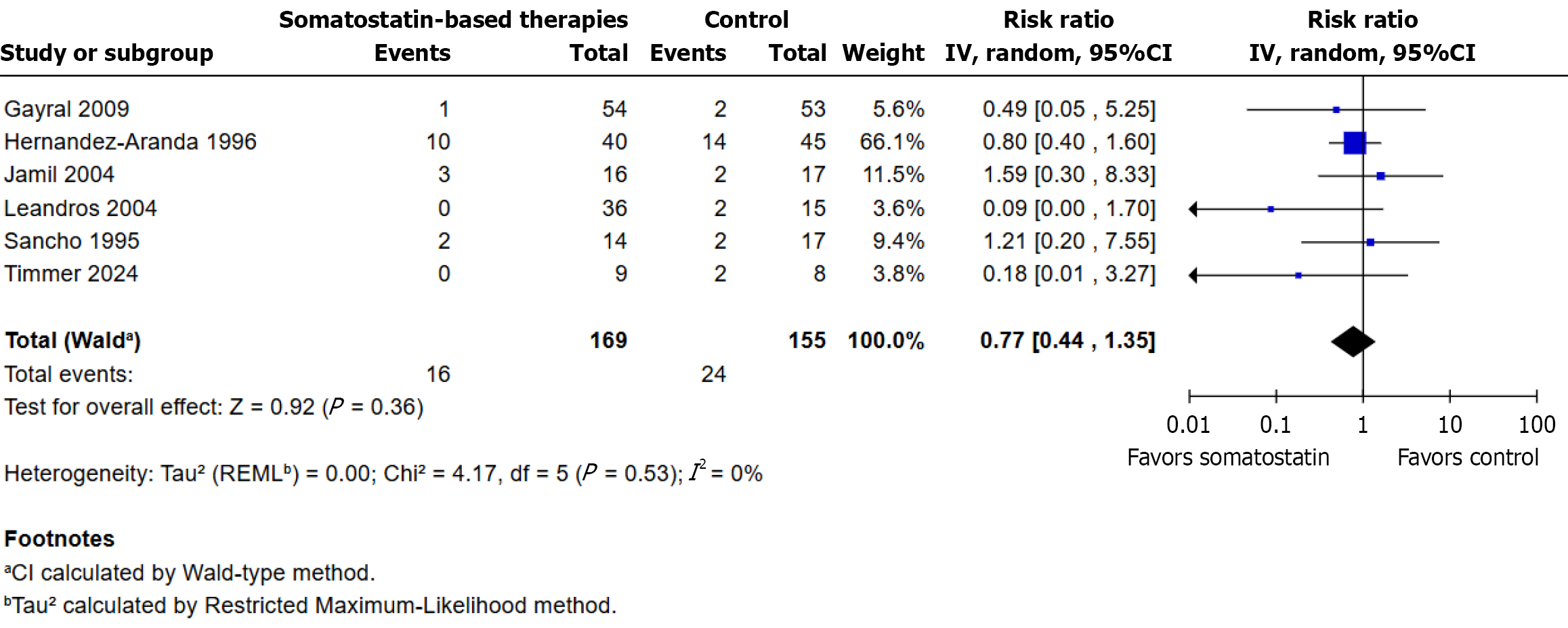

There was no statistically significant difference in closure rate (RR: 1.11, 95%CI: 0.95-1.28, P = 0.19, I² = 0%) between 134/193 patients receiving somatostatin-based therapy and 99/170 control patients. Time to closure was reduced by 6.16 days (mean difference -6.16, 95%CI: -7.44 to -4.88, P < 0.001, I² = 0%) in 126 patients in intervention group vs 114 in control group. Hospital stay was shortened by 4.00 days (mean difference -4.00, 95%CI: -7.99 to -0.01, P = 0.05, I² = 0%) in 56 vs 62 patients. There were no differences in complications (RRs: 0.76, 95%CI: 0.55-1.05), need for surgical intervention (RRs: 0.67, 95%CI: 0.38-1.19), or mortality (RRs: 0.77, 95%CI: 0.44-1.35). Limitations include small sample sizes, heterogeneity in treatment regimens, and inconsistent outcome definitions, which may affect generalizability. Limited data for some outcomes, such as hospital stay, and exclusion of some datasets for methodological reasons reduced statistical power.

Somatostatin-based therapies did not significantly improve fistula closure rates but were associated with shorter time to closure and hospital stay. Mortality, complications, and surgical intervention requirements remained un

Core Tip: This meta-analysis of nine randomized controlled trials found that somatostatin and its analogues do not increase spontaneous closure rates of external gastrointestinal fistulas compared to standard care. However, treatment significantly shortens hospital stay and time to closure. These benefits suggest that somatostatin-based therapy may be useful as an adjunct in selected patients requiring faster recovery and reduced hospitalization.

- Citation: Ribeiro Junior MAF, Fontenelle Vieira L, Thalib HI, Fouzaan Albeez S, Heba Fakruddin F, Mirza Zafar Baig A, Mohammed H, Nafeesa Hashim S, Rauf Khan AA, Dib Possiedi R. Somatostatin-based therapies for external gastrointestinal fistulas: Updated meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther 2025; 16(4): 111889

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2150-5349/full/v16/i4/111889.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4292/wjgpt.v16.i4.111889

External gastrointestinal fistulas (EGIFs) are abnormal communications between the gastrointestinal tract and the skin, most often arising as complications after abdominal surgery[1]. They include enterocutaneous fistulas, which have a defined tract to the skin, and enteroatmospheric fistulas, where the bowel opens directly into an open abdominal wound without soft tissue coverage[2]. EGIFs are among the most frequent and serious postoperative complications in gastrointestinal surgery, particularly in malnourished or hypercatabolic patients[3]. In contrast to internal fistulas, EGIFs open externally, allowing direct visualization and measurement of output, which enables objective monitoring of healing and standardized assessment in clinical trials. Despite optimal conservative management, spontaneous closure occurs in only 24% to 61% of cases, and persistent high-output or septic fistulas may have mortality rates approaching 30%, with hospital stays often exceeding several weeks at a high economic cost[1-3]. The standard treatment approach includes managing the source of the fistula together with nutritional care and thorough wound management. The clinical value of using somatostatin and its analogues to decrease gastrointestinal secretions and enhance spontaneous closure remains ambiguous.

The evaluation of somatostatin-based therapies in this context has been conducted through meta-analyses[3-6]. How

This comprehensive meta-analysis examined randomized controlled trials that directly compared somatostatin or its analogues to control treatments in adult patients with external gastrointestinal fistulas. The analysis included only studies that provided separate data for each treatment arm. The analysis excluded studies that presented median values without standard deviation measures or studies with skewed results that could not be converted to a usable format. The research team extracted duplicate data thoroughly while using the Cochrane RoB 2.0 tool to evaluate study bias[8]. The study evaluated four main outcomes which included spontaneous closure rate and time to closure as well as length of hospital stay, need for surgical intervention and mortality. The analysis used appropriate statistical models to analyze each outcome while accounting for heterogeneity.

The aim of the present study is to evaluate the effectiveness of somatostatin-based treatments for external gastroin

This systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted and reported in accordance with the Cochrane Handbook and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines[9,10]. Studies were included based on the following the Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcome, Timing, Setting criteria: (1) Population: Patients with confirmed external gastrointestinal fistulas; (2) Intervention: Somatostatin or its analogues (e.g., octreotide, lanreotide); (3) Comparator: Placebo or standard non-somatostatin care; (4) Outcomes: Fistula closure rate, output reduction, time to closure, length of hospital stay, complication rates, and mortality; (5) Timeline: No restrictions on publication date; and (6) Study design: RCTs. Studies were excluded if they did not meet the predefined eligibility criteria. Specifically, we excluded studies involving non-gastroenterocutaneous fistulas (e.g., respiratory or vascular), studies using somatostatin analogues for indications other than fistula management, and non-randomized study designs such as observational studies, case series, case reports, reviews, editorials, or letters. Conference abstracts without access to full data, as well as studies lacking a comparator group or without extractable outcome data relevant to fistula closure, output reduction, hospital stay, complications, or mortality, were also excluded. Duplicate publications or subgroup analyses were excluded unless they provided new, relevant data. No language restrictions were applied during the selection process. The literature search included randomized controlled trials published between 1990 and 2025.

This systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted according to a predefined protocol registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews[11] on 16 May 2025, under registration number CRD420251054344, ensuring transparency and methodological rigor.

Two independent reviewers conducted a systematic search of PubMed, Scopus, EMBASE, Cochrane, LILACS, WHO ICTRP, Web of Science, and ClinicalTrials.gov in May 2025. The search strategy used keywords that linked fistulas to somatostatin therapy through "Enteric fistula", "Intestinal fistula", "Digestive fistula" and "Somatostatin", "Octreotide", "Lanreotide". The complete search approach for all databases and trial registries appears in Supplementary material.

A manual review of reference lists from included studies was performed to identify extra relevant publications for complete coverage. The selection of eligible studies followed established inclusion and exclusion criteria. The kappa sta

Two reviewers used Rayyan[12] to conduct independent study selection. First evaluated titles and abstracts based on established eligibility criteria before proceeding to full-text evaluation of relevant studies. A third reviewer was consulted to resolve disagreements until the reviewers reached an agreement. Cohen’s kappa to measure inter-reviewer agreement was not considered due to small number of conflicts that needed adjudication, indicative of high agreement.

Two independent reviewers used a standardized form to extract data from included studies. The following data were collected: (1) Study characteristics, including year of publication, authors, study design (prospective or retrospective), and number of patients in intervention and control groups; (2) Baseline patient demographics (age, sex) and fistula characteristics, including origin (esophagus, stomach, pancreas, duodenum, small bowel, jejunum, ileum, ileocolic, or other), pretreatment output (maximum, minimum), and classification (Type 1a or 1b for non-pancreatic fistulas); (3) Clinical parameters, including presence of pre-trial sepsis, hyperglycemia, and whether initial surgery was elective or emergency; (4) Intervention details, encompassing somatostatin or analogue regimen (dose, duration) and duration of nutritional support (mean ± SD days); and (5) Outcomes, including fistula output reduction (mean ± SD at 24 hours, 48 hours, and 72 hours), time to achieve 50%, 75%, and 100% output reduction (days), fistula closure rates (with or without surgery), morbidity (total and subtypes: Catheter-related sepsis, abdominal sepsis, urinary sepsis, pneumonia, pneumothorax, wound infection), mortality, and mean hospital length of stay (± SD). The researchers documented both follow-up duration and essential observations which included latency time and delay time to intervention.

We used PlotDigitizer[13] as a web-based application to extract numerical data from graphical presentations of outcomes in studies that only showed results in graphical format. The tool helped convert data points from Kaplan-Meier curves and bar graphs and other important figures into numerical values for fistula output reduction and time to closure when these values were not available in the text or tables. The extracted coordinates underwent conversion into estimated means and standard deviations and time-to-event values through established methods. Two reviewers independently extracted graph data until they reached consensus to resolve discrepancies which ensured methodological accuracy and consistency.

The analysis of randomized controlled trials was limited to specific outcomes because of major differences in outcome definitions and measurement methods and reporting formats. The following outcomes were analyzed through forest plots: (1) Fistula closure; (2) Time to fistula closure; (3) Need for surgical intervention; (4) Hospital length of stay; (5) Clinical complications, and (6) Mortality. The selected outcomes were based on the availability of comparable data across at least two studies. The analysis excluded outcomes that had inconsistent definitions or insufficient numerical reporting or significant methodological variability.

The risk of bias assessment was conducted by two independent reviewers for all included randomized controlled trials using the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool (RoB 2.0)[8]. The evaluation systematically examined five critical areas: (1) The ran

The Cochrane Handbook suggests performing qualitative publication bias assessment when the number of included RCTs is below 10. The analysis of funnel plots together with statistical tests (e.g., Egger’s regression) was not feasible because of insufficient power and the potential for incorrect interpretation. The evaluation used a structured domain-based assessment instead of funnel plots and statistical tests (e.g., Egger’s regression) because of insufficient power and risk of misleading interpretation. The evaluation assessed five aspects which included (1) Small-study effects; (2) Effect size distribution by sample size; (3) Temporal distribution; (4) Geographic pattern; and (5) Selective outcome reporting. The analysis used extracted data about sample sizes together with binary and continuous outcome information and publication dates and study country[9,14].

The certainty of evidence for each outcome was evaluated using the GRADE approach[8,9]. Five domains were assessed: Risk of bias, informed by Cochrane RoB 2.0 assessments; inconsistency, based on the I² statistic and effect direction; indirectness, based on outcome relevance; imprecision, based on confidence interval width and sample size; and pub

The researchers conducted a meta-analysis of RCTs through a random-effects model to handle the anticipated clinical and methodological differences between studies. Review Manager[15] served as the platform for performing all statistical tests. The Forest plots displayed both individual and combined effect size estimates.

The analysis of dichotomous outcomes including fistula closure rate, mortality, complication rate and need for surgical intervention used risk ratios (RRs) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) derived from raw event data obtained directly from the included trials. The Mantel-Haenszel method was used to pool RRs.

The analysis of continuous outcomes such as hospital length of stay and time to fistula closure used mean differences (MDs) with 95%CIs when mean and standard deviation (SD) data were available or could be reliably estimated. The estimation of mean and SD used validated statistical methods[16,17] when studies presented medians with ranges or interquartile intervals and the distribution assumptions were valid. The analysis of pooled continuous data was excluded when the data included skewed distributions or right-censored time-to-event outcomes because estimation proved inappropriate.

The Higgins I² statistic[18] was used to evaluate between-study heterogeneity. The 95%CI should not contain the null value for effect sizes to be considered statistically significant.

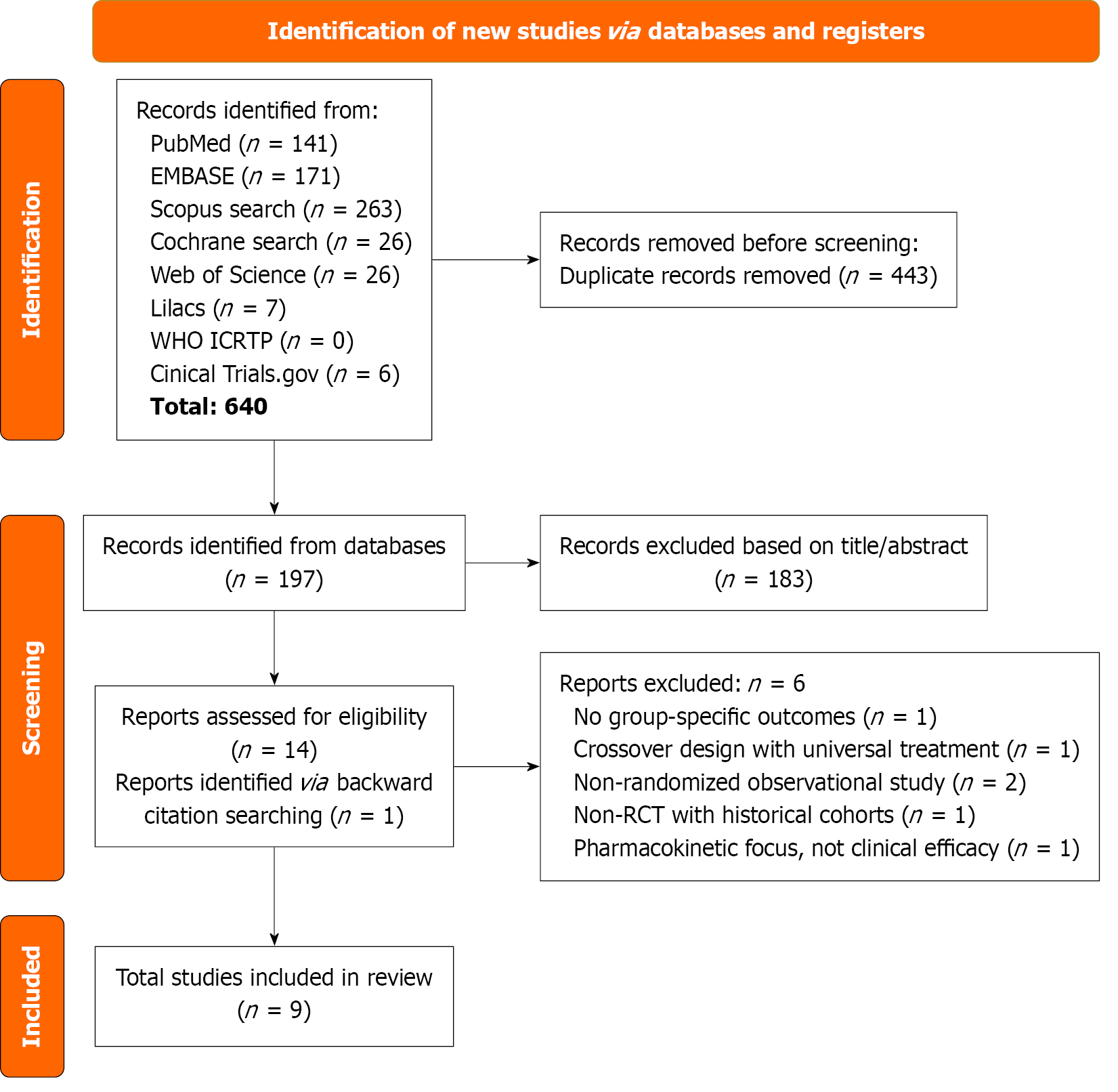

A total of 640 articles were identified from the six databases and two registration trials. After removing 443 duplicates, 197 articles were screened based on title and abstract. Subsequently, 15 full-text reports were examined, and nine studies were included in the quantitative synthesis. One additional article was included during the screening of previous reviews. Ultimately, 9 RCTs were included[1,2,7,19-24], with a total of 442 patients, of whom patients were assigned to somatostatin-based therapies and 211 patients were assigned to control group. Study characteristics are present in Table 1. More information is provided in Figure 1.

| Ref. | Follow-up, days | Type of study | Intervention group | Control group | No. of patients | Age years1 | Male | Fistula type | High output | Low output | Output mL/day |

| Torres et al[1], 1992 | 20.4 | Prospective, randomized, multicenter. Blinding status is unclear | TPN combined with continuous intravenous infusion of somatostatin (250 µg/hour) | TPN alone for first 15 days; supportive care included nasogastric suction, antibiotics, wound protection; patients with < 30% output reduction after 15 days could cross over to somatostatin | 40 | 55.7 (35-78); mean (range) | 10 (50) | Duodenum n = 5; pancreatic n = 7; jejunum n = 7; ileum n = 18; ileocolic n = 3 | 0 | 40 (100) | 286.1 |

| Scott et al[19], 19932 | 12 | Prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial | Octreotide 100 µg subcutaneously three times daily for 12 days | Placebo (acetate-buffered saline injections) for 12 days | 19 | 61.4 (22-78) | 7 (36.8) | Stomach n = 2; duodenum n = 4; pancreatic n = 2; small n = 11 | NR | NR | 359 |

| Isenmann et al[20], 1994 | 30 | Prospective, randomized, multicenter. Blinding status is unclear | IV somatostatin 250 µg/hour continuous infusion; increased to 500 µg/hour if output > 500 mL/day after 7 days; maintained until closure + 1-3 days; TPN only; NPO except 200-300 mL water/day | TPN alone; no somatostatin; NPO except 200-300 mL water/day; continued for ≥ 14 days, with possible crossover to somatostatin after 2 weeks if no improvement | 45 | 57.7 (28-82), mean (range) | 28 (68%) | Pancreatic n = 20; bile duct n = 4; small bowel | 0 | 45 (100) | 334.7 |

| Sancho et al[21], 1995 | 20 | Prospective, randomized, double-blind, multicenter | Early administration of octreotide (100 μg subcutaneously every 8 hours) combined with total parenteral nutrition | Placebo (1 mL 0.9% saline SC every 8 hours) + total parenteral nutrition (TPN: 40 kcal/kg/day, 0.2 g protein/kg/day, 50% glucose, 50% lipids); all received H2 blockers (cimetidine/ranitidine), nasogastric tube, and antibiotics as needed | 31 | 64.5 (58-73); mean (range) | 19 (61.29) | Stomach n = 1; duodenum n = 11; pancreatic n = 5; jejunum n = 5; ileum n = 9 | NR | NR | 835.7 |

| Hernández-Aranda et al[2], 1996 | 28 | Prospective, randomized. Blinding and center status are unclear | Octreotide 100 µg SC every 8 hours + conventional care (fluid/electrolyte replacement, skin protection, nutritional support, antibiotics); surgery if sepsis or fistula-persisting factors were present | Conventional care only: Fluid and electrolyte replacement, skin protection, nutritional support, and antibiotics; surgery if sepsis or fistula-persisting factors were present | 99 | 50.1 (19.5); mean (SD) | 55 (55.56) | Esophagus n = 11; stomach n = 10; duodenum n = 22; small bowel n = 56 | 84 (84.8) | 15 (15.2) | NR |

| Leandros et al[22], 2004 | NA | Prospective, randomized, single-center. Blinding status is unclear | Somatostatin group: Somatostatin 6000 IU/day IV continuous infusion + SMT. Octreotide Group: Octreotide 100 µg SC three times daily + SMT | SMT only: Fluid/electrolyte correction, nutritional support, sepsis control, and wound care | 51 | 67 (14.7); median (SD) | 31 (60.8%) | Stomach n = 4; pancreatic n = 13; bile duct n = 8; small and large bowel n = 23; other n = 3 | 24 (47.1) | 27 (56.3) | NR |

| Jamil et al[23], 2004 | 90 | Prospective, randomized, single-center. Blinding status is unclear | Octreotide 300 µg/day SC in three divided doses (100 µg TID) + standard supportive care (TPN, antibiotics, fluid/electrolyte replacement, skin/wound care, NPO until fistula output < 200 mL/day) | Standard supportive care only: TPN, antibiotics, fluid/electrolyte replacement, skin/wound care, NPO until fistula output < 200 mL/day | 33 | 38.3 (mean) | 18 (55) | Duodenum n = 2; jejunum n = 6; ileum n = 17; colon n = 4; appendicular n = 1; bibiopancreatic n = 3 | NR1 | NR1 | NR |

| Gayral et al[7], 2009 | NA | Prospective, randomized, double-blind, multicenter | Lanreotide 30 mg PR could receive up to 6 injections at 10-day intervals | Placebo IM injection (matching schedule) + systemic standard care (fluid/electrolyte balance, sepsis control, nutritional support) | 107 (ITT n = 102) | 56.9 (15); mean (SD) | 59 (55.1) | Duodenum n = 18; pancreatic n = 71; small bowel n = 18 | NR | NR | 3369 |

| Timmer et al[24], 2024 | 56 | Prospective, randomized, open-label, multicenter | Standard treatment plus lanreotide 120 mg subcutaneous injection once every 4 weeks for in total 8 weeks | Standard care only: Fluid/electrolyte replacement, sepsis control, nutritional support, and wound care | 17 | 60.6 (14); mean (SD) | 10 (58.8) | Duodenum n = 2; small bowel n = 15 | 17 (100) | 0 | 1484 |

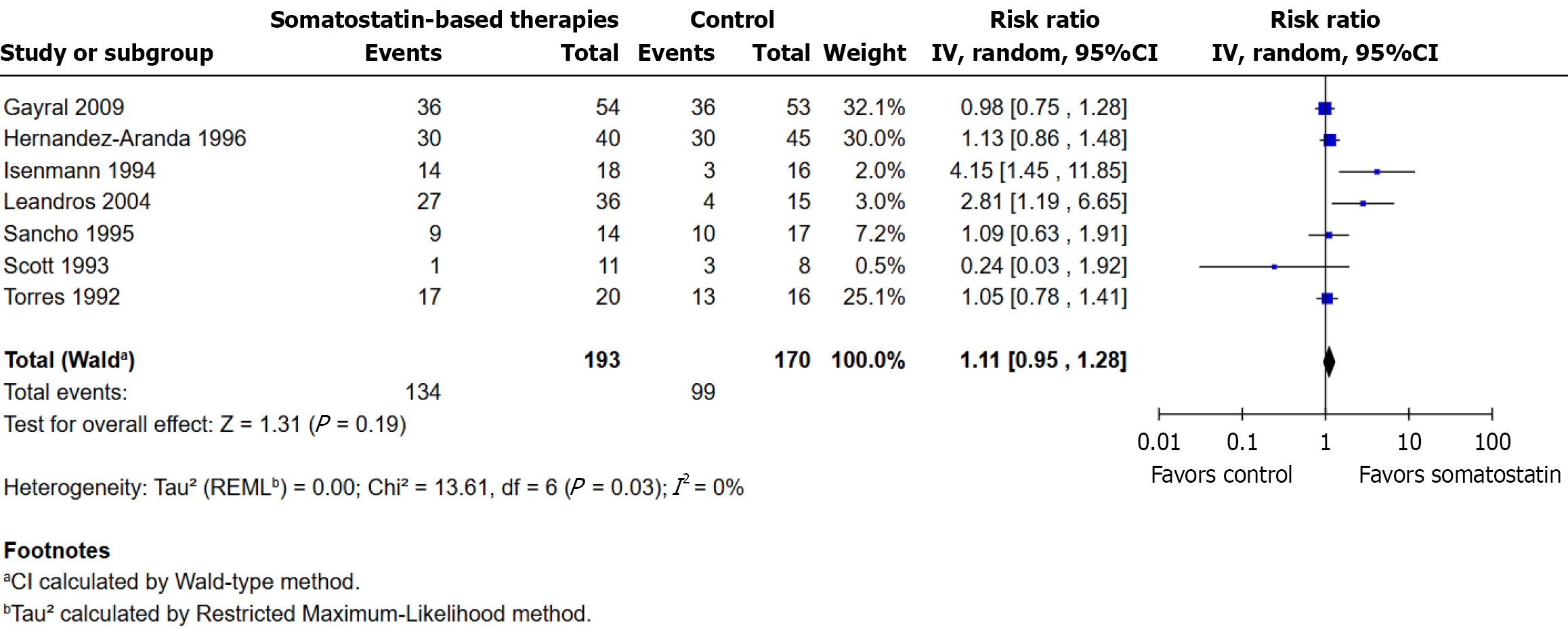

The analysis included seven randomized controlled trials. Fistula closure occurred in 134/193 participants (69.4%) in the somatostatin group and in 99/170 participants (58.2%) in the control group. No statistically significant difference was observed (RR: 1.11; 95%CI: 0.95 to 1.28; P = 0.19). Heterogeneity was low (I² = 0%, τ² = 0.00, χ² P = 0.70). The direction of effect varied among studies, with some favoring somatostatin-based treatments and others favoring the control group. Gayral et al[7] (32.1%) and Hernández-Aranda et al[2] (30.0%) contributed the most to the total weight (Figure 2). Fistula closure definitions across the nine included studies varied in output thresholds (< 5 mL/day to < 50 mL/day, or zero output for 1-3 days), duration of assessment (24 hours to 3 months), and confirmation methods (clinical, radiological, or ultrasonographic), as summarized in Supplementary Table 1.

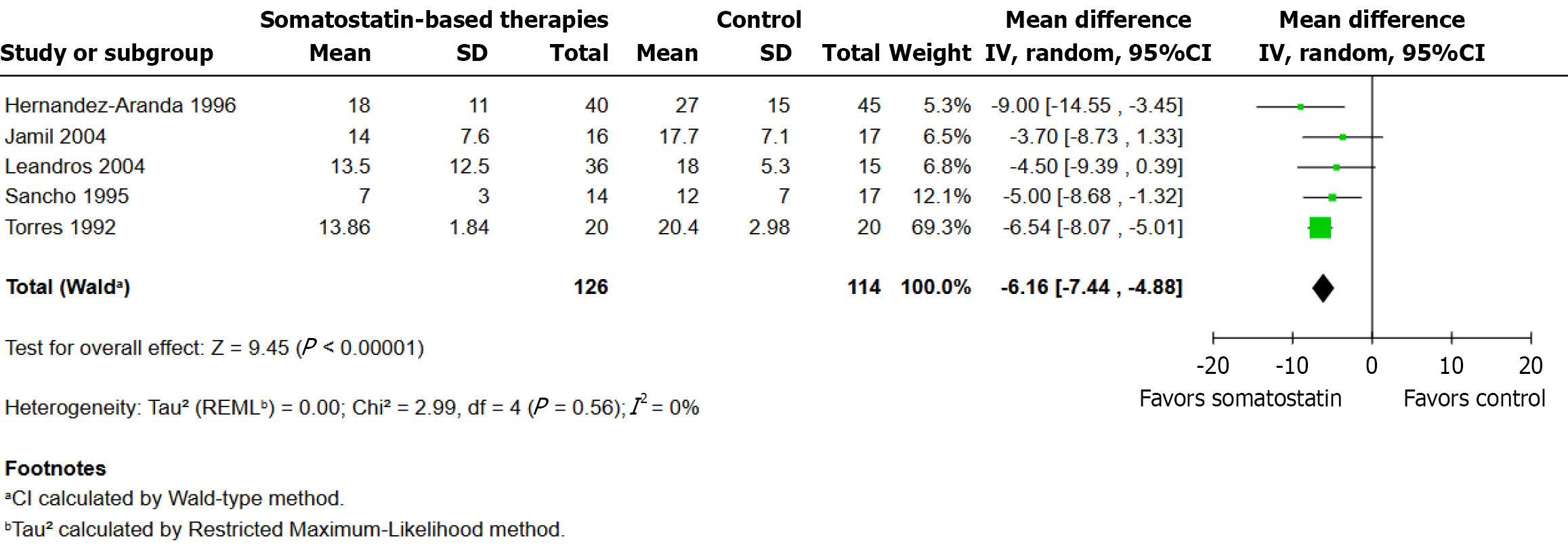

Five randomized controlled trials were included in this analysis, with a total of 126 patients in the somatostatin therapy group and 114 in the control group. Using a random-effects model, the pooled analysis showed that the somatostatin group had a statistically significant decrease in closure time (MD: -6.16 days; 95%CI: -7.44 to -4.88; P < 0.001; I2 = 0%). All five studies demonstrated that somatostatin-based therapy resulted in faster closure times and their effect estimates pointed in the same direction with Torres et al[1] contributing the most weight (69.3%) to the pooled estimate because their study included a larger sample and narrower confidence interval (Figure 3).

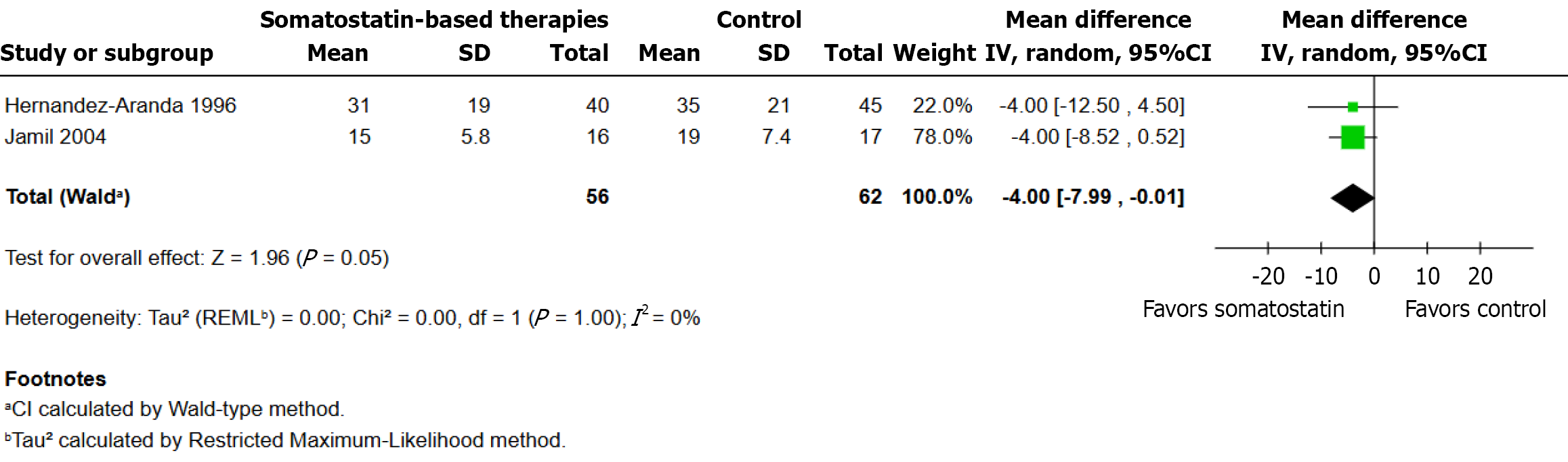

Data from two randomized controlled trials with a total of 56 patients in the somatostatin therapy group and 62 patients in the control group were included in this analysis. The pooled analysis revealed a statistically significant reduction (MD: -4.00 days; 95%CI: -7.99 to -0.01; P = 0.05; I2 = 0%) in hospital stay duration for the somatostatin group. Both studies demonstrated that intervention treatment outperformed control and the effects pointed in the same direction with similar magnitudes (Figure 4).

A total of six randomized controlled trials were included in this analysis. Clinical complications or adverse events occurred in 48/137 participants (35.0%) in the somatostatin-based therapies group and in 41/117 participants (35.0%) in the control group. The pooled analysis, conducted using a random-effects model, showed no statistically significant difference between groups (RR: 0.76; 95%CI: 0.55 to 1.05; P = 0.10; I² = 0%). The weight distribution across studies varied, with Leandros et al[22] contributing the most (38.1%) and Isenmann et al[20] the least (2.7%). While four studies favored somatostatin-based therapies, one favored the control group, and another had a risk ratio close to unity, reflecting con

Six randomized controlled trials were included in this analysis. Surgical intervention was required in 27/143 participants (18.9%) in the somatostatin-based therapies group and in 31/125 participants (24.8%) in the control group. No statistically significant difference was observed between groups (RR: 0.67; 95%CI: 0.38 to 1.19; P = 0.18). Heterogeneity was low (I² = 31%, τ² = 0.16, χ² P = 0.29). Four studies favored somatostatin-based therapies, although wide confidence intervals often included the line of no effect. Leandros et al[22] contributed the largest weight (32.8%) to the pooled estimate (Figure 6).

Six randomized controlled trials were examined. Mortality occurred in 16/169 participants (9.5%) in the somatostatin-based therapies group and in 24/155 participants (15.5%) in the control group. The pooled analysis, performed using a random-effects model, showed no statistically significant difference between groups (RR: 0.77; 95%CI: 0.44 to 1.35; P = 0.36; I² = 0%). Effect estimates varied in direction and magnitude, with some trials favoring the intervention and others the control, and wide confidence intervals in most comparisons. Hernández-Aranda et al[2] contributed the highest weight (66.1%) to the overall estimate (Figure 7).

The risk of bias assessment revealed considerable variability in methodological rigor among the included randomized controlled trials. Most trials exhibited at least some concerns regarding the randomization process. Several studies failed to describe the method of sequence generation or allocation concealment[2,19-22], while others were rated as high risk due to absent methodological information and baseline imbalances[1,23]. Deviation from intended interventions was generally not a significant issue, with most trials maintaining treatment fidelity; however, performance bias could not be excluded in studies lacking blinding or using open-label designs[1,7,23,24].

The handling of missing outcome data was adequate in most trials, with low dropout rates and complete reporting[19,20,24]. Nonetheless, some studies did not clarify whether intention-to-treat analyses were performed or how withdrawals were handled[21]. Regarding outcome measurement, the majority of studies used objective criteria such as fistula output or closure time, minimizing detection bias.

Selective reporting was a recurrent issue, as several studies lacked trial registration or published protocols, raising concerns about outcome reporting bias[1,2,19,21,23]. Additionally, other sources of bias were identified in some trials, including small sample sizes, underpowered analyses, and potential influence from industry funding[1,7,19,23,24]. The detailed risk of bias assessments for each trial are available in Supplementary Table 2.

The qualitative assessment of the included RCTs showed no sign of publication bias. The smaller studies did not consistently report exaggerated treatment effects, and there was no observable trend linking sample size to outcome magnitude. The included trials were published over a broad time frame, with several older studies reporting non-significant findings, which reduces concern regarding time-related suppression of neutral results. Geographically, the studies represented diverse settings, including both high- and middle-income countries. In multiple trials, incomplete or inconsistent reporting of secondary endpoints such as complications and cost was noted, warranting moderate concern. Detailed results are provided in Supplementary Table 3.

The certainty of evidence for each outcome was assessed using the GRADE approach. Overall, the certainty ranged from moderate (for time to closure) to low (for all other outcomes), mainly due to concerns regarding risk of bias, imprecision, and limited sample sizes. A summary of the GRADE ratings is presented in Supplementary Table 4.

The analysis of nine RCTs evaluating somatostatin or its analogues (octreotide, lanreotide) in patients with EGIFs provides a comprehensive evaluation of their efficacy compared to standard care. The use of somatostatin-based the

The observed acceleration in fistula closure aligns with the pharmacologic properties of somatostatin and its analogues, which reduce gastrointestinal secretions and splanchnic blood flow, potentially facilitating healing by decreasing output and enzymatic damage to surrounding tissues. This effect is particularly relevant for patients with high-output fistulas, who are often more refractory to conservative management[1,2,21-23]. The reduction in hospital LOS supports the potential for these therapies to optimize resource-limited healthcare systems, although limited data availability for this outcome underscores the need for further research. The lack of impact on closure rates and mortality highlights the complexity of EGIF management, where fistula etiology, anatomical location, and comorbidities play critical roles.

The previous meta-analyses produced conflicting results because of their methodological constraints. The study by Rahbour et al[3] showed positive results in closure rates but incorporated non-randomized studies and incorrectly presented data from essential trials[1,7,20,21,23]. The study by Coughlin et al[6] focused on pancreatic fistulas which restricted the generalizability of their findings to EGIFs while also containing errors in standard deviation reporting[1,2,6]. Stevens et al[4] and Gefen et al[5] conducted their analysis with limited RCTs while using outdated statistical methods without performing thorough risk-of-bias evaluations. This meta-analysis used RCTs exclusively and excluded pancreatic-only cohorts while employing the Cochrane RoB 2.0 tool and validated methods to estimate means from medians when appropriate which improved methodological rigor[16,17].

This study's strengths include its focus on EGIFs, exclusion of non-randomized studies, and comprehensive risk-of-bias assessment, which revealed concerns in most trials, particularly regarding randomization[1,23]. The observed variability in definitions of fistula closure across studies likely contributed to heterogeneity in pooled estimates, potentially masking differences in closure rates. Standardizing outcome definitions, such as output thresholds and confirmation methods, in future trials could improve comparability and reduce bias in meta-analyses. The homogeneity in primary outcomes supports the reliability of pooled estimates. However, limitations include heterogeneity in intervention regimens (soma

Somatostatin-based therapies appear to reduce time to fistula closure and hospital stay in patients with external gas

We are sincerely grateful to Professor Dr. Rainer Isenmann and to Mrs. Shabana Seemee, Managing Editor of the Journal of the College of Physicians and Surgeons Pakistan, for their generous support in providing access to two key articles that were otherwise unavailable online or through United States institutional libraries. Their assistance was instrumental in ensuring the completeness and rigor of this study. Artificial intelligence tools were used to assist with deduplication and citation management (Zotero), study screening (Rayyan), plagiarism checking (Ref-n-write), language editing (ChatGPT), data extraction from figures (PlotDigitizer), and statistical analysis (RevMan) during manuscript preparation. The authors reviewed and approved all AI-generated content and are fully responsible for its accuracy and integrity.

| 1. | Torres AJ, Landa JI, Moreno-Azcoita M, Argüello JM, Silecchia G, Castro J, Hernandez-Merlo F, Jover JM, Moreno-Gonzales E, Balibrea JL. Somatostatin in the management of gastrointestinal fistulas. A multicenter trial. Arch Surg. 1992;127:97-9; discussion 100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Hernández-Aranda JC, Gallo-Chico B, Flores-Ramírez LA, Avalos-Huante R, Magos-Vázquez FJ, Ramírez-Barba EJ. [Treatment of enterocutaneous fistula with or without octreotide and parenteral nutrition]. Nutr Hosp. 1996;11:226-229. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Rahbour G, Siddiqui MR, Ullah MR, Gabe SM, Warusavitarne J, Vaizey CJ. A meta-analysis of outcomes following use of somatostatin and its analogues for the management of enterocutaneous fistulas. Ann Surg. 2012;256:946-954. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Stevens P, Foulkes RE, Hartford-Beynon JS, Delicata RJ. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the role of somatostatin and its analogues in the treatment of enterocutaneous fistula. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;23:912-922. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Gefen R, Garoufalia Z, Zhou P, Watson K, Emile SH, Wexner SD. Treatment of enterocutaneous fistula: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Tech Coloproctol. 2022;26:863-874. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Coughlin S, Roth L, Lurati G, Faulhaber M. Somatostatin analogues for the treatment of enterocutaneous fistulas: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Surg. 2012;36:1016-1029. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Gayral F, Campion JP, Regimbeau JM, Blumberg J, Maisonobe P, Topart P, Wind P; Lanreotide Digestive Fistula. Randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study of the efficacy of lanreotide 30 mg PR in the treatment of pancreatic and enterocutaneous fistulae. Ann Surg. 2009;250:872-877. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, Boutron I, Cates CJ, Cheng HY, Corbett MS, Eldridge SM, Emberson JR, Hernán MA, Hopewell S, Hróbjartsson A, Junqueira DR, Jüni P, Kirkham JJ, Lasserson T, Li T, McAleenan A, Reeves BC, Shepperd S, Shrier I, Stewart LA, Tilling K, White IR, Whiting PF, Higgins JPT. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366:l4898. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6581] [Cited by in RCA: 18895] [Article Influence: 2699.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Higgins J, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page M, Welch V, Flemyng E. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.5 [Internet]. Cochrane, 2024. Available from: www.cochrane.org/handbook. |

| 10. | Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 52948] [Cited by in RCA: 48675] [Article Influence: 2863.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 11. | National Institute for Health and Care Research. PROSPERO International prospective register of systematic reviews: CRD420251054344 [Internet]. University of York; 2025. Report No.: CRD420251054344. Available from: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD420251054344. |

| 12. | Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016;5:210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5711] [Cited by in RCA: 14504] [Article Influence: 1450.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | PlotDigitizer [Internet]. Available from: https://plotdigitizer.com. |

| 14. | Harbord RM, Harris RJ, Sterne JAC. Updated Tests for Small-study Effects in Meta-analyses. Stata J. 2009;9:197-210. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 15. | Cochrane Collaboration. Review Manager (RevMan) [Internet]. London; 2025. Available from: https://revman.cochrane.org/. |

| 16. | Luo D, Wan X, Liu J, Tong T. Optimally estimating the sample mean from the sample size, median, mid-range, and/or mid-quartile range. Stat Methods Med Res. 2018;27:1785-1805. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2418] [Cited by in RCA: 2779] [Article Influence: 347.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Wan X, Wang W, Liu J, Tong T. Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from the sample size, median, range and/or interquartile range. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14:135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3433] [Cited by in RCA: 8069] [Article Influence: 672.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21:1539-1558. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21630] [Cited by in RCA: 27090] [Article Influence: 1128.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Scott NA, Finnegan S, Irving MH. Octreotide and postoperative enterocutaneous fistulae: a controlled prospective study. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 1993;56:266-270. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Isenmann R, Schielke D, Mörl F, Wünsch N, Vestweber K, Doertenbach J, Konradt J, Hantschmann, Horst VDW, Loch H, Buchler M. Adjuvante Therapie postoperativer PankreasGalle- und Dünndarmfisteln mit Somatostatin i.v. 9 Eine multizentrische, randomisierte Studie. Aktuelle Chir. 1994;96:96-99. |

| 21. | Sancho JJ, di Costanzo J, Nubiola P, Larrad A, Beguiristain A, Roqueta F, Franch G, Oliva A, Gubern JM, Sitges-Serra A. Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial of early octreotide in patients with postoperative enterocutaneous fistula. Br J Surg. 1995;82:638-641. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Leandros E, Antonakis PT, Albanopoulos K, Dervenis C, Konstadoulakis MM. Somatostatin versus octreotide in the treatment of patients with gastrointestinal and pancreatic fistulas. Can J Gastroenterol. 2004;18:303-306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Jamil M, Ahmed U, Sobia H. Role of somatostatin analogues in the management of enterocutaneous fistulae. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2004;14:237-240. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Timmer AS, de Vries F, Gans SL, Zwanenburg PR, Bemelman WA, Dijkgraaf MGW, Dijkstra G, van der Heide F, Haveman JW, Serlie MJ, Boermeester MA. Clinical trial: The effectiveness of long-acting somatostatin analogue for output reduction of high-output intestinal fistula or small bowel enterostomy. A randomised controlled trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2024;60:727-736. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/