Published online Dec 5, 2025. doi: 10.4292/wjgpt.v16.i4.110827

Revised: June 24, 2025

Accepted: September 24, 2025

Published online: December 5, 2025

Processing time: 172 Days and 8.1 Hours

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), recognized as the most prevalent liver disease worldwide and a leading cause of liver trans

Core Tip: Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH), have emerged as leading causes of chronic liver disease globally, paralleling the rise in obesity, type 2 diabetes, and metabolic syndrome. These conditions significantly increase the risk of cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carci

- Citation: Zacharia GS, Ashraf MH, Sosa F, Jacob A, Patel H. Quick glance at 'metabolic dysfunction associated steatotic liver disease' therapeutics: Targets, trials, and trends. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther 2025; 16(4): 110827

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2150-5349/full/v16/i4/110827.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4292/wjgpt.v16.i4.110827

From a hepatology perspective, the most significant development in 2023 was likely the change in nomenclature from nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) to MASLD. Accordingly, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) was replaced by MASH. The NAFLD or MASLD spectrum constitutes the most frequent liver disease worldwide. In 2016, a meta-analysis with more than eight million subjects reported a global prevalence of 25.2% of NAFLD[1]. The prevalence is much higher in individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), as high as 65%[2]. MASLD is a risk factor for cirrhosis and hepatocellular cancer (HCC) and is the most common indication for liver transplantation in the United States. It is closely related to cardiovascular diseases, which are also the most common cause of mortality in MASLD[3]. First reported by Ludwig et al[4] in 1980, little progress has been made in the pharmacotherapy of NAFLD/MASLD over the past quarter-century. This review article explores the available pharmacological options and their clinical evidence in treating the most common global liver disease.

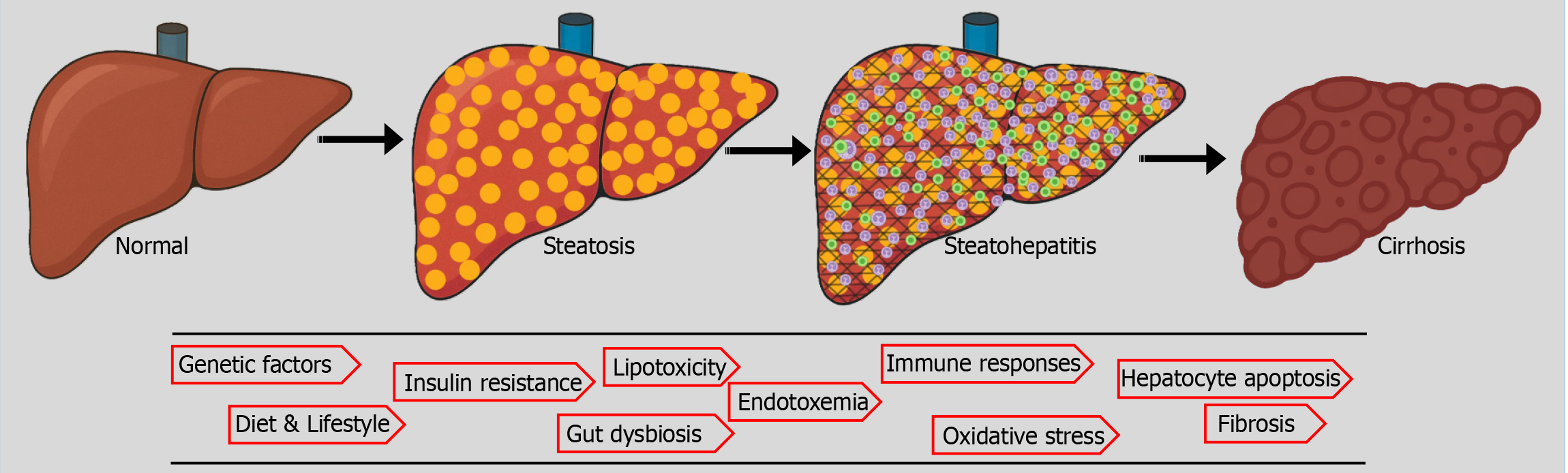

MASLD is a complex and multifactorial disease with a spectrum ranging from simple steatosis to concomitant inflammation, fibrosis, and cirrhosis (Figure 1). A "multiple-hit hypothesis" better explains the pathogenesis, which encom

Genetic factors are believed to play a key role in the pathogenesis of MASH/MASLD, which could explain the regional and ethnic variability in the incidence, progression, and severity of steatotic liver diseases. It is considered to be a polygenic disorder; a few implicated include patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing protein 3 (PNPLA3), fat mass and obesity-associated, sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1 (SREBP1), insulin receptor, torsin family 1-member B, glucuronidase beta, membrane-bound O-acyltransferase domain-containin/transmembrane channel-like 4, cordon-bleu WH2 repeat protein like 1/growth factor receptor-bound protein 14 and protein tyrosine phosphatase receptor type D genes. The PNPLA3 I148M variant and the TM6SF2 E167K variant are the best-studied genetic variants strongly associated with MASLD/MASH. Conversely, specific genetic variants of Pleckstrin and Sec7 domain-containing 3, alcohol dehydrogenase 1B, and mammalian tribbles homolog 1 confer protection against steatotic liver diseases[6]. First-degree relatives of patients with MASLD cirrhosis carry a 12-fold higher risk of advanced fibrosis[7]. A family history of hepatic steatosis does increase an individual's risk by nearly two-fold[8]. Twin studies reveal high concordance in hepatic steatosis and fibrosis between monozygotic but not dizygotic twins[9].

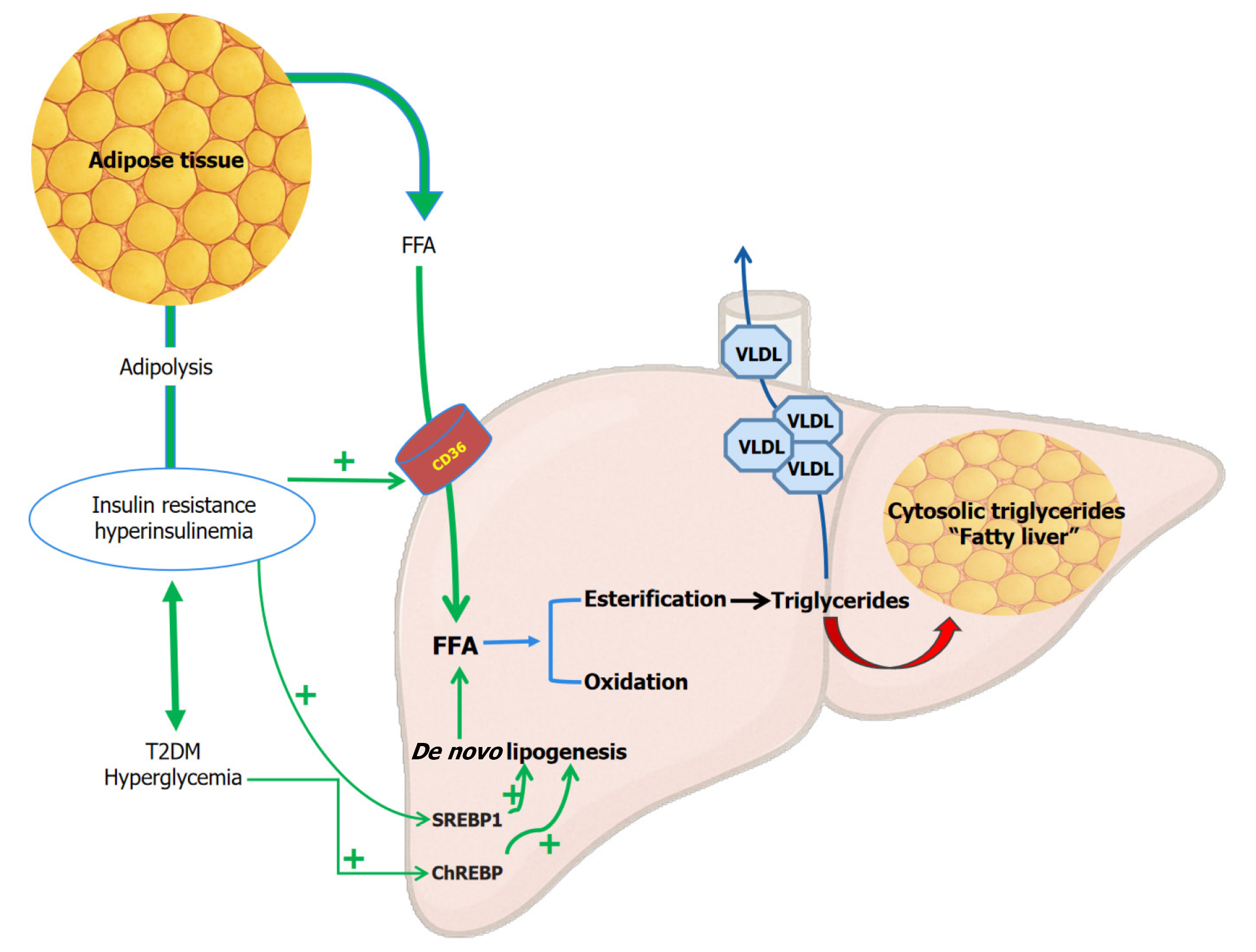

Insulin resistance: Insulin plays a crucial role in lipid metabolism by increasing lipogenesis and decreasing lipolysis. It inhibits hormone-sensitive lipases in adipose tissue. Quantitative insulin deficiency or insulin resistance promotes adipolysis, increasing the availability of circulating free fatty acids (FFA). The liver takes the circulating FFAs with the help of fatty acid translocase (CD36) and fatty acid-binding proteins. Within the hepatocytes, the FFA undergoes beta-oxidation or esterification to generate triglycerides. Insulin resistance and subsequent hyperinsulinemia promote hepatic FFA uptake and esterification, while inhibiting beta-oxidation, leading to the accumulation of triglycerides within hepatocytes, a condition known as fatty liver[10-12]. This 'paradoxical hepatic lipogenesis', unlike the lipolysis in the periphery, is at least partially explained by the upregulation of sterol regulatory element binding protein 1c, a transcription factor induced by hyperinsulinemia in the liver. Hyperinsulinemia also promotes the activity of hepatic acetyl-CoA carboxylase and fatty acid synthase, contributing to hepatic de novo lipogenesis, which converts glucose into fatty acids and triglycerides within the liver[13,14]. The role of insulin resistance in the pathogenesis of MASLD/MASH is depicted in Figure 2.

Lipotoxicity is believed to be a primary contributor to the progression of fatty liver disease to steatohepatitis and ultimately to fibrosis and cirrhosis. Excess FFA in the liver, especially in cases of insulin resistance, overwhelms the hepatic capacity to handle it. The excess FFA is metabolized into intermediates such as ceramides, diacylglycerol, and lysophosphatidylcholine, which can be potentially hepatotoxic. The excess mitochondrial oxidation of FFA generates oxygen-free radicals, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial dysfunction. The FFA also impairs the protein folding function of the endoplasmic reticulum. In addition to promoting hepatocyte apoptosis, lipotoxicity contributes to an inflammatory response through the activation of nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) pathways. The loss of hepatocytes and inflammation activate hepatic stellate cells, leading to the deposition of extracellular matrix, fibrosis, and, ultimately, cirrhosis[15-18].

Gut dysbiosis: Alterations in the intestinal microbiome, characterized by increased loads of harmful bacteria and a decline in favorable fauna, are associated with diet, lifestyle, and host environmental or genetic factors. Studies in MASLD/MASH have revealed a higher Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes (F/B) ratio. At the genus level, an increase in Escherichia, Prevotella, Shigella, and Streptococcus has been reported in NAFLD[19,20]. The Enterobacteriaceae contribute to the synthesis of endogenous alcohol and endotoxin[20]. Eubacterium, Lachnospiraceae, and Subdoligranulum, the bacteria that produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), are depleted in obesity and NAFLD[20]. Intestinal bile acid metabolism is closely linked to the gut microbiome and involves several processes, including deconjugation, dihydroxylation, oxidation, and sulfation, among others. Bile acids exert regulatory effects on bacterial colonies due to their physical and antimicrobial properties[21]. The microbiome-bile acid interplay is intricate, and gut dysbiosis impacts bile acid homeostasis. The altered bile acid proportions are frequently reported in NAFLD/NASH[22]. Overall, gut dysbiosis contributes to the spectrum of steatotic liver disease by altering intestinal permeability, inducing endotoxemia, disrupting the bile acid pool, and promoting endogenous alcohol synthesis[23].

SCFA: SCFA plays an integral role in maintaining the mucosal barrier by providing nutrition to colonocytes, increasing the expression of tight junctions, and synthesizing mucin. SCFA interacts with free fatty acid receptors FFAR2 and FFAR3 and increases the secretion of peptide YY (PYY) and GLP-1 by the intestinal L-cells. The PYY is an anorexigenic hormone and an inhibitor of gastric emptying, which induces satiety. GLP-1 induces insulin secretion while suppressing glucagon synthesis and gastric emptying[24]. The SCFA exhibits anti-inflammatory activity by inhibiting histone deacetylases in the T cells[25]. Butyrate is also postulated to suppress the NF-kB signaling and enhance the expression of anti-inflammatory cytokines[26]. Alterations in the gut microbiome negatively affect the synthesis of SCFA, subsequently increasing the risk of cardiometabolic and steatotic liver diseases.

Farnesoid X receptor: Farnesoid X receptor (FXR) is a nuclear hormone receptor expressed at the highest density in the intestine and liver. It is also known as a bile acid receptor, as its natural ligands are bile acids. However, besides bile acid homeostasis, they play crucial roles in glucose and lipid metabolism, liver growth and regeneration, and immune responses[27]. The enterocyte FXR, when activated by the bile acids, generates FGF19, which binds with fibroblast growth factor receptor 4 (FGFR4) in the liver and suppresses the cytochrome P450 enzymes, CYP7A1 and CYP8B1, responsible for bile acid synthesis[27]. The key regulator of hepatic lipogenesis, sterol regulatory element binding protein 1c, is downregulated by the activation of FXR. FXR activation also suppresses IR, gluconeogenesis, and inflammatory response, enhancing liver regeneration through multiple pathways. FXR-deficient animal models display hyperglycemia, hypertriglyceridemia, hepatic steatosis, inflammation, and fibrosis[28]. Yang et al[29] have demonstrated decreased FXR expression in patients with NAFLD[29].

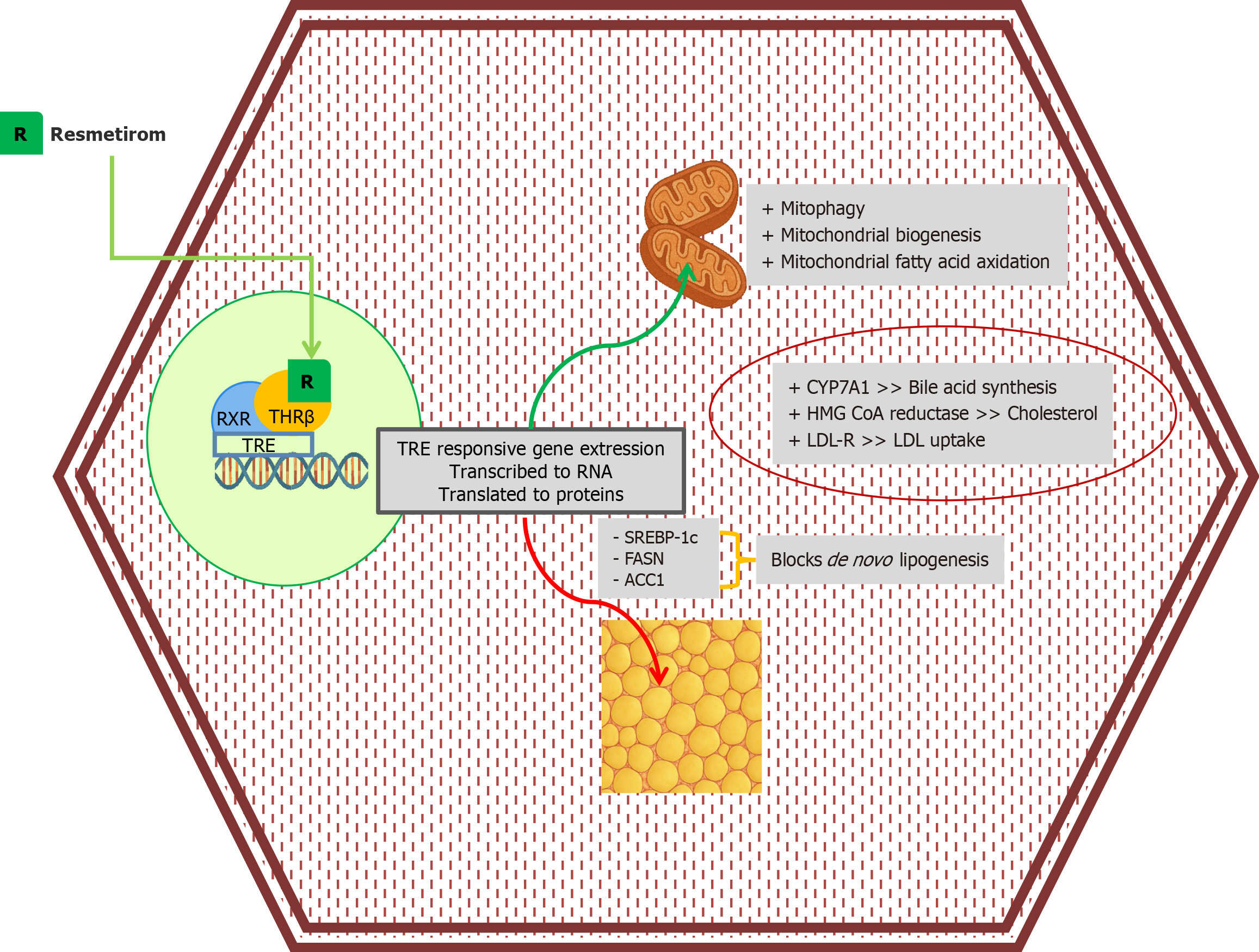

Thyroid hormones and receptors: Thyroid hormones have pleiotropic effects, with metabolic impacts being the most well-known. Hypothyroidism is associated with elevated levels of total cholesterol, low-density lipoproteins (LDL), and triglycerides. A higher incidence of hypercholesterolemia, cardiovascular diseases, and NAFLD/NASH has been observed in subclinical and clinical hypothyroidism[30]. Interestingly, studies have reported a higher risk of NASH, over and above NAFLD, in patients with hypothyroidism[30,31]. The nuclear THR-β mediate the effects of thyroid hormones. The α isoform is primarily expressed in the cardiac and skeletal muscles, bone, and brain, while the β isoform is mainly expressed in the liver, kidney, and pituitary[32]. The net impact of hepatic THR-β activity on lipid metabolic pathways is the clearance of intrahepatic fat via enhanced intrahepatic lipolysis, lipophagy, β-oxidation, and bile acid synthesis (Figure 3)[33]. In animal models, loss-of-function THR-β mutations have been associated with hepatic steatosis[34]. Furthermore, thyroid hormones and THR-β ligands reduced hepatic triglyceride content, suggesting their potential role in the pathogenesis of steatotic liver diseases[23-36].

PPAR: PPARs are nuclear receptors that, upon activation by ligand interaction, promote the transcription of a wide range of genes involved in lipid and glucose homeostasis, energy balance, inflammation, and other processes[37]. The isoform PPARβ/δ is ubiquitously expressed, while PPARα is predominant in the liver and muscles, and PPARγ is concentrated in adipose tissue, as well as to a lesser extent in the liver. The endogenous PPAR ligands include free fatty acids, eico

Fibrosis: The onset and progression of fibrosis have detrimental effects on outcomes of MASLD/MASH. Histologically graded by METAVIR score, hepatic fibrosis ranges from no fibrosis (F0) to cirrhosis (F4)[41]. Fibrosis is the final common pathway in all liver diseases, leading to cirrhosis. Advancing hepatic fibrosis predicts poorer liver outcomes, deve

Vitamin E is one of the most frequently utilized medications for treating steatotic liver disease. Due to its antioxidant effects, vitamin E helps neutralize hepatic oxidative stress. Through protein kinase C inhibition, α-tocopherol inhibits cellular proliferation in various cell types, including monocytes/macrophages, neutrophils, fibroblasts, and vascular smooth muscle cells. Inhibition of the lipoxygenase pathway leads to reduced levels of IL-1β, a pro-inflammatory cyt

Multiple studies have demonstrated the biochemical and histological benefits of Vitamin E in fatty liver[49,50]. The PIVENS trial demonstrated a statistically significant improvement in NASH in non-diabetic individuals with 800 IU/day of vitamin E over 96 weeks. Beyond ALT, improvement was also noted in hepatic steatosis and inflammation, hepatocyte ballooning, and NASH activity score. Subsequent analysis of the PIVENS data confirmed that the benefits were irrespective of the weight loss, further substantiating the beneficial effects of vitamin E[51,52]. A meta-analysis by Sato et al[53] revealed significant improvement in hepatic biochemistry and histological changes in NASH treated with vitamin E. A 2022 phenome-wide association study identified protective benefits of vitamin E, most pronounced in overweight and diabetic patients, at doses exceeding 400 IU/day, and with an overall reduction in mortality[54]. Conversely, the TONIC trial, a multicenter study involving pediatric and adolescent subjects, failed to demonstrate a statistically significant improvement in hepatic chemistries[55]. Casting further shadows over prolonged vitamin E therapy, the SELECT trial reported an increased incidence of prostate cancer (Hazard ratio: 1.17; 99%CI: 1.004-1.36, P = 0.008) among men on vitamin E compared to those on placebo[56]. Considering the lack of convincing long-term data on the beneficial effects and concerns over prostate cancer, vitamin E is currently not recommended as a targeted therapy for MASH by the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) practice guidelines, 2024[57]. The 2023 AASLD guideline states that vitamin E supplements can be considered in select individuals with NASH without diabetes mellitus; however, vitamin E lacks United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for use in NAFLD[58].

Bile acids, whether primary or secondary, are the endogenous FXR ligands, with chenodeoxycholic acid being the most potent. The 6α-ethyl chenodeoxycholic acid, known as obeticholic acid (OCA), is a synthetic FXR agonist. The drug was approved in 2016 for use in primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) in patients without cirrhosis or with compensated cirrhosis, not responding or intolerant to ursodeoxycholic acid. However, post-marketing, pooled data analysis of patients with PBC treated with OCA also revealed a higher incidence of dose-dependent, serious hepatic complications, including decompensation and death. Hence, the FDA recommends against the use of OCA in decompensated cirrhosis as well as in patients with compensated cirrhosis with portal hypertension. In 2018, the drug received a black box warning rega

OCA was also used, off-label, in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis and NASH. In 2015, the FLINT trial reported histologic improvement with OCA, including attenuation of steatosis, inflammation, and fibrosis in non-cirrhotic NASH[60]. The REGENERATE Phase III trial also demonstrated biochemical and histological improvement, as well as superior results with 25 mg daily compared to 10 mg dosing in pre-cirrhotic NASH[61]. The trials reported dose-dependent pruritus as the most frequent adverse effect, occurring in 23% of participants in FLINT and 51% in RE

The newer FXR agonists in the pipeline include cilofexor, TERN-101, tropifexor, vonafexor, MET-409, and nidufexor. All these medications are in phase I or II trials, and available data reveal favorable impacts on hepatic biochemistry and histology. All these drugs report pruritus as a significant adverse effect but with fewer lipid disturbances. Further controlled trials and real-life data should confirm the beneficial effects of these promising classes of medications[63].

Resmetirom, a selective THR-β, was approved for human use in March 2024. The MAESTRO-NASH trial, a Phase III, multicenter, randomized controlled trial conducted across 15 countries, reported improved steatoinflammatory changes and fibrosis in patients with biopsy-proven NASH, with fibrosis scores ranging from F1b to F3. Resolution of NASH was reported in 25.9% of patients receiving 80 mg and 29.9% receiving 100 mg of resmetirom, compared to 9.7% in the placebo arm, at the end of 52 weeks. Improvement in fibrosis occurred in 24.2% and 25.9% of patients treated with 80 mg and 100 mg resmetirom, respectively, compared to 14.2% in the placebo group. However, those with no fibrosis and cirrhosis were excluded from the study[64]. A subsequent meta-analysis by Dutta et al[65] reported significant improvements in lipids, hepatic biochemistry, cytokeratin 18, and radiological parameters, including Fibroscan® and magnetic resonance imaging-proton density fat fraction (MRI-PDFF). The MRI-PDFF reported a mean difference of -27.76% and -36.01% for 80 mg and 100 mg of resmetirom, respectively, suggesting a significant reduction in hepatic fat content. Firboscan reported a mean difference of -21.45 dBm with an 80 mg dose and -25.51 dBm with a 100 mg dose. The significant adverse effects reported in trials included gastrointestinal disturbances, such as diarrhea and nausea[66]. The ongoing MAESTRO-NASH-OUTCOMES and MAESTRO-NAFLD-OLE trials are expected to provide further insights into this groundbreaking medication regarding its role in compensated cirrhosis and long-term safety, respectively. Other selective THR-β agonists include sobetirome, eprotirome, and VK2809. Eprotirome trials were halted due to funding issues, according to the manufacturer, while sobetirome trials were halted due to concerns about hepatotoxicity, cartilage damage, and increased cardiovascular risk[67]. The phase IIb VOYAGE trial reported promising data with VK2809, again with no significant adverse effects[68].

PPARα agonists: This class of molecules includes the traditional fibrates: Fenofibrate, bezafibrate, gemfibrozil, and the novel selective agent, pemafibrate.

Conventional agents have proven benefits in hypertriglyceridemia and, to a lesser extent, in elevating HDL levels. While some studies demonstrate benefits with reduced liver enzymes and fat accumulation, the overall impact in patients with MASLD/MASH remains inconsistent and unclear[69,70]. Fibrates are myotoxic, especially in combination with statins or in those with impaired renal function. Fenofibrate has been associated with an increase in creatinine and a decline in glomerular filtration rates compared to placebo trials[71]. Pemafibrate, a selective PPARα modulator, is more effective in lowering triglyceride levels than other medications. In a 48-week trial involving patients with MASLD, pemafibrate significantly reduced liver enzymes and NAFLD fibrosis scores[72]. It appears to be better tolerated and safer than traditional fibrates, particularly in patients with kidney dysfunction.

PPARγ agonists: The thiazolidinedione class primarily focuses on glucose homeostasis through improved insulin sensitivity. They also positively affect lipid profiles by increasing HDL and lowering triglyceride levels. Pioglitazone and rosiglitazone, the molecules belonging to this family, are approved for the treatment of T2DM. Pioglitazone has demonstrated benefits in NASH, particularly in individuals with insulin resistance, with the attenuation of steatosis, inflammation, and even fibrosis in some cases[51,73]. Although the PIVENS study reported improvements in individual components of NAFLD/NASH, it failed to achieve the prespecified outcome in the trial and was found to be inferior to vitamin E[51]. Additionally, side effects like weight gain, fluid retention, and a higher risk of heart failure have limited its broader use. Thiazolidinediones are primarily metabolized in the liver and therefore require no dose adjustment in cases of renal dysfunction. Instead, they confer renoprotective effects through anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and anti-apoptotic effects[74].

Dual PPARα/γ agonists: Saroglitazar activates both PPARα and PPARγ, thereby helping to reduce high triglyceride, total cholesterol, and LDL levels while also augmenting insulin sensitivity. The molecule has been evaluated to be safe and effective in diabetic dyslipidemia[75]. Trials with Saroglitazar reported improvement in transaminase levels, hepatic fat content, and NASH activity indices[76,77]. According to the drug manufacturer, Zydus, saroglitazar received approval from the Drug Controller General of India for the treatment of NASH in 2020; however, this information could not be verified from the Central Drugs Standard Control Organisation portal of the country[78,79]. Saroglitazar at a dose of 4 mg/day improves lipid and glycemic profile, transaminase levels, and liver stiffness[80]. The molecule is generally safe; however, possible side effects may include mild stomach upset, fluid retention, and weight gain, which are likely due to its partial action on PPARγ.

Pan-PPAR agonists: Lanifibranor activates PPAR α, γ, and δ; targets multiple aspects of MASH pathogenesis. It enhances fatty acid oxidation via PPAR-α, improves insulin sensitivity, and reduces inflammation via PPAR-γ while modulating lipid metabolism via PPAR-δ. The phase II NATIVE trial showed encouraging results, improving inflammation and fibrosis in people with NASH[81]. It also improved the glycemic and lipid profiles, with few adverse effects: Weight gain, peripheral edema, and anemia. The drug is undergoing Phase III NATiV3 clinical trials to evaluate its efficacy and safety. The Phase III trial was temporarily paused in February 2024 after a patient developed an unexpected elevation in liver enzymes; however, it continued and completed enrollment in April 2025, with results expected in late 2026[82,83].

GLP-1 is a gut-derived incretin, which, via increased insulin secretion coupled with attenuation of glucagon release and gastric emptying, induces satiety, promotes weight loss, and improves glucose-lipid homeostasis. This class of medication includes liraglutide, semaglutide, dulaglutide, exenatide, and tirzepatide, all of which are approved for the management of T2DM. All these molecules have been evaluated in MASLD/MASH, as insulin resistance, hyperlipidemia, and body mass index also play a role in the pathogenesis of steatotic liver diseases. The LEAN trial, in patients with biopsy-proven NASH, evaluated liraglutide at 1.8 mg/day vs placebo for 48 weeks. It reported NASH resolution in 39% of the liraglutide arm compared to 9% in the placebo group, with reduced progression of fibrosis[84]. Semaglutide has shown efficacy in resolving NASH in 59% of patients, compared to 17% in the placebo arm, in a phase 2 trial; however, improvement in fibrosis was not statistically significant[85]. Data from the REWIND trial suggest favorable hepatic outcomes with dulaglutide, particularly with a once-weekly dose, although it has yet to be evaluated in a dedicated NASH biopsy trial[86]. Klonoff et al[87] reported a reduction in hepatic fat content and transaminase levels in patients with NAFLD and diabetes with exenatide; again, histological evidence of improvement is limited. Tirzepatide, a dual agonist of GLP-1 and Glucose-dependent Insulinotropic Polypeptide (GIP), has demonstrated superior metabolic and hepatic effects compared to isolated GLP-1 agonists. In the SYNERGY-NASH trial, tirzepatide significantly reduced liver fat and improved non-invasive markers of liver inflammation[88].

Tirzepatide is more effective than semaglutide and liraglutide in terms of weight loss, glycemic control, and major adverse cardiac events; the same may be true for its efficacy in MASLD/MASH; however, there are very limited head-to-head comparisons available[89]. The additional benefits could be a result of the combined GLP1/GIP agonism. The meta-analysis by Luo et al[90] reported that semaglutide is superior to liraglutide and dulaglutide. To date, none of these agents have been approved for managing patients with MASLD/MASH despite promising results and a favorable safety profile.

SGLT-2 inhibitors, a class of oral antidiabetic agents, have demonstrated hepatoprotective effects, making them yet another therapeutic option for patients with MASLD/MASH, especially those with T2DM. In the E-LIFT trial, empag

Metformin, the only biguanide currently in clinical use, has a well-established safety and efficacy profile in T2DM, which has been demonstrated over more than five decades. It is believed to act by reducing hepatic glucose synthesis, increasing gut glucose utilization, increasing GLP-1 levels, and attenuating insulin resistance. The insulin-sensitizing effects of metformin have been explored in the treatment of MASLD/MASH, as insulin resistance plays a key role in its patho

Insulin and insulin secretagogues: Physiologically, insulin inhibits lipolysis and promotes lipogenesis; therefore, it should be beneficial for fatty liver disease. Hyperinsulinemia is not the cause of fatty liver disease but rather the effect of insulin resistance. Neither insulin nor its secretagogues, sulfonylureas, significantly impact insulin sensitivity. Very few trials have explored the role of insulin therapy in MASLD/MASH, likely due to the theoretically counterproductive mechanism. In an animal model trial, utilizing NASH hamsters with streptozotocin-induced hyperglycemia, insulin therapy improved hyperglycemia, dyslipidemia, hepatic steatosis, inflammation, and fibrosis[101]. The fallacy of this study is that streptozotocin-induced DM by pancreatic β-cell toxicity is more similar to type 1 rather than T2DM. Fatty liver disease is a primary concern in T2DM and metabolic syndrome rather than in type 1 DM; hence, this data might not apply in clinical practice. Liu et al[102] reported improved liver fat content with insulin glargine in patients with NAFLD and T2DM, although to a lesser extent than with exenatide, in a randomized controlled trial. The addition of insulin glargine to oral hypoglycemic agents was associated with reduced hepatic fat measures, as estimated by magnetic resonance spectroscopy, in patients with T2DM[103]. On the contrary, patients with DM and fatty liver disease on insulin or sulfonylurea had a higher prevalence of advanced fibrosis on liver biopsy[104]. Limited data also exist suggesting an increased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma, irrespective of cirrhosis, in patients on insulin therapy[105]. Sulfonylureas and meglitinides are metabolized in the liver and carry a higher risk of hypoglycemia in patients with poor hepatic reserve. They are not recommended for patients with advanced liver disease[106]. Overall, the data is sparse in recommending or refuting insulin or its secretagogues from a pure fatty liver perspective.

Statins, which inhibit 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase, a key enzyme in lipid metabolism, reduce in vivo cholesterol synthesis. They possess a wide range of hypolipidemic effects, reducing LDL by 25% to 60%, total cholesterol by 17% to 35%, and triglycerides by 10% to 40%, depending on the type and dose of statins[107,108]. Large-scale studies have reported a very high incidence of hypertriglyceridemia and hyperlipidemia in patients with MASLD and MASH, up to 60% to 80%[1,109]. Beyond their lipid-lowering effects, statins exhibit a multitude of impacts, col

FGF21 analogs have been extensively evaluated for their antifibrotic and antisteatotic effects in the MASH model. Pegbelfermin was the first drug of this class to be assessed; however, it has largely fallen out of favor due to the failure to demonstrate significant histological improvement in the Phase IIb FALCON 1 and 2 trials[112,113]. Efruxifermin and pegozafermin belong to the same class and are undergoing phase III trials in patients with advanced fibrosis[114].

FGF19 analogs, Aldafermin and NGM282, are undergoing trials for the treatment of MASLD/MASH. FGF19 is a gut-derived, mostly ileal, hormone that interacts with the hepatic receptor FGFR4 to initiate many metabolic effects. It attenuates bile acid synthesis, regulates carbohydrate and lipid metabolism, and enhances β-oxidation, reducing oxidative stress and inflammation, ultimately leading to a favorable response to fatty liver disease. Rinella et al[115] reported a significant reduction in hepatic fibrosis in patients with compensated NASH cirrhosis following the administration of Aldafermin 3 mg for 48 weeks. A recent meta-analysis of four trials, including 491 patients, reported MASH resolution, improvement in fibrosis, and a reduction in hepatic fat fraction in biopsy-proven MASH, with a favorable safety profile. However, concerns exist regarding FGF19 and FGFR4 activation due to their potential links to cancers, including HCC[116].

Fatty acid synthase inhibitors block de novo lipogenesis, thereby attenuating lipotoxicity, inflammation, and subsequent fibrosis. Denifanstat, as reported in the recently concluded Phase IIb trial, FASCINATE-2, showed statistically significant improvements in NAFLD activity scores, NASH resolution, and fibrosis stage compared to placebo[117]. The positive results from the trial yielded Denifanstat, a breakthrough therapy designation from the FDA, for treating MASH with advanced fibrosis.

Rencofilstat, a non-immunosuppressive cyclophilin inhibitor, was evaluated in MASH and showed promising antifibrotic effects in Phase IIa trials[118]. The FDA granted Rencofilstat fast-track designation for treating NASH in 2021; however, the phase IIB trials were halted in 2024, citing resource constraints[119].

The galectin-3 inhibitor belapectin was found to reduce hepatic fibrosis and portal hypertension in preclinical trials, with a favorable safety profile in Phase 1 trials[120]. However, Phase IIb trials failed to reproduce the similar benefits observed over placebo[121].

Aramchol, a stearoyl-CoA desaturase inhibitor, has shown modest improvement in hepatic fibrosis and NASH resolution without significant adverse effects; however, it failed to demonstrate a favorable impact on hepatic fat content[122].

Acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) inhibitors reduce hepatic de novo lipogenesis via the acetyl-CoA carboxylase 1 isoenzyme while enhancing mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation through the ACC2 isoenzyme. The net reduction in hepatic lipid load attenuates lipotoxicity, characterized by apoptosis, inflammation, and fibrosis. The first molecule of this class, Firsocostat, reported a median relative reduction in hepatic fat content of 29% compared to 8% in the placebo group. Paradoxically, the agent was associated with plasma hypertriglyceridemia in a subset of patients[123].

Other novel agents in the pipeline include a CC-chemokine receptor antagonist, Cenicriviroc; mitochondrial pyruvate carrier inhibitors, such as MSDC-0602K; a pan-caspase inhibitor, Emricasan; a lysyl oxidase-like 2 inhibitor, Simtuzumab; and patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing protein-3 targeting agents, including ION839 and LY3849891. Prebiotics, probiotics, and even fecal microbiota transplants have been explored in treating MASLD/MASH, targeting the gut microbiome alterations observed in these patients[124].

In summary, as of mid-2025, resmetirom is the only United States-FDA-approved medication for patients with MASH and moderate to advanced fibrosis, specifically stages F2 to F3. The AASLD practice guidance, 2023, states that the use of semaglutide and pioglitazone in the context of DM could benefit NASH, while vitamin E can be considered for patients without DM. However, none of these agents are approved by the United States FDA, and their use is rather off-label for MASLD/MASH[58]. The drug manufacturer of Saroglitazar in India claims that the molecule received approval for the treatment of NASH; however, the author(s) could not confirm this information[78,79]. Despite having an ample number of molecules in the pipeline for the management of MASLD/MASH, translating these into day-to-day clinical practice faces major hurdles due to genetic and ethnic patient heterogeneity, lack of validated non-invasive endpoints, limited long-term outcome data, safety concerns, and high costs. Many of these factors lead to regulatory uncertainties, further complicating the real-world application of these therapeutic molecules. An excerpt of candidate molecules, including their mechanism of action, therapeutic targets, and the phase of trials in the treatment of MASLD/MASH, is tabulated in Table 1.

| Class of medication | Mechanism of action/target(s) | Candidate medication | Phase of development notable trials | |

| FXR agonists | Regulates bile acid metabolism; Reduces insulin resistance; Reduces hepatic lipogenesis, inflammation, fibrosis | Obeticholic acid | Phase 3 (REGENERATE) | |

| Tropifexor | Phase 2 (FLIGHTFXR) | |||

| Cilofexor | Phase 2 | |||

| PPAR agonists | Increased clearance of intrahepatic fat; Improves insulin sensitivity; Downregulates stellate cells; Attenuates fibrogenesis | Pan PPAR-α/δ/γ | Lanifibranor | Phase 3 (NATiV3) |

| Dual PPAR-α/δ | Elafibranor | Phase 3 (RESOLVE-IT) | ||

| Dual PPAR-α/γ | Saroglitazar | Phase 2b | ||

| THR-βagonists | Reduce hepatic triglycerides by enhanced intrahepatic lipolysis, lipophagy, β-oxidation, and bile acid synthesis | Resmetirom | Phase 3 (MAESTRO-NASH) | |

| VK2809 | Phase 2b (VOYAGE) | |||

| GLP-1 agonists | Induces satiety, weight loss; Incretin effect: Improved glycemic control; Positive effects lipid metabolism | Semaglutide | Phase 3 (ESSENCE) | |

| Liraglutide | Phase 2 (LEAN) | |||

| SGLT2 inhibitors | Improves glycemic control, lipid profile; Weight loss; Postulated anti-inflammatory/antifibrotic effects | Dapagliflozin | Phase 3 (DEAN), Phase 4 | |

| Empagliflozin | Phase 4 | |||

| Galectin-3 inhibitors | Reduce macrophage-mediated inflammation; Inhibits activation and proliferation of stellate cells; Reduces hepatocyte apoptosis, promotes regeneration | Belapectin | Phase 3 (NAVIGATE) | |

| Selvigaltin | Phase 1b/2a (GULLIVER-2) | |||

| FGF analogues | Decreases hepatic fat content; Improves insulin sensitivity; Anti-inflammatory, antifibtotic effects | FGF21 | Pegbelfermin | Phase 2b |

| FGF19 | Aldafermin | Phase 2b (ALPINE) | ||

| ACC inhibitors | Decreses de novo lipogenesis; Promotes fatty acid oxidation | Firsocostat | Phase 2 | |

| MPC inhibitors | Inhibits pyruate transport from cytosol to mitocondria | MSDC-0602K | Phase 2b (EMMINENCE) | |

| Decreases de novo lipogeneis, Increases fatty acid oxidation | PXL065 | Phase 2 (DESTINY-1) | ||

| CCR2/CCR5 antagonist | Anti-inflammatory, antifibrotic effects | Cenicriviroc | Phase 3 (AURORA) | |

| Cyclophiphin inhibitor | Regulates collagen and extracellular matrix; Antisteatotic, anti-inflammatory, antifibrotic effects | Rencofilstat | Phase 2b (ASCEND-NASH) | |

| Pan-caspase inhibitor | Anti-apoptotic, anti-inflammatory effects | Emricasan | Phase 2 (ENCORE-NF) | |

| SCD1 inhibitor | Prevents hepatic triglyceride synthesis | Aramchol | Phase 3 (ARMOR) | |

| LOXL2 inhibitor | Impedes collagen cross linking, fibrosis progression | Simtuzumab | Phase 2 | |

| siRNA | Silencing effects of interfering RNA on metabolic pathways, inflammation, callagen synthesis, fibrosis, etc. | GalNAc-siPLIN2 | Preclinical | |

| ALN-HSD | Phase 1/2 | |||

| BMS986263 | Phase 2 | |||

| FASN inhibitor | Inhibits de novo hepatic lipogenesis | Denifanstat | Phase 2b (FASCINATE-2) | |

| Vitamin E | Antioxidant action: Reduces hepatic oxidative stress/injury | Vitamin E | Phase 3 (PIVENS; TONIC) | |

| Statins | HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor - blocks cholestrol biosynthesis; Pleomorphic effects: Anti-inflammatory, antifibtotic | Atorvastatin | Phase 2/3 | |

Pharmacotherapy for MASLD/MASH, formerly NAFLD/NASH, is rapidly evolving, with multiple agents demon

| 1. | Younossi ZM, Koenig AB, Abdelatif D, Fazel Y, Henry L, Wymer M. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease-Meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology. 2016;64:73-84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5322] [Cited by in RCA: 7944] [Article Influence: 794.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (8)] |

| 2. | Younossi ZM, Golabi P, Price JK, Owrangi S, Gundu-Rao N, Satchi R, Paik JM. The Global Epidemiology of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Among Patients With Type 2 Diabetes. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024;22:1999-2010.e8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 193] [Article Influence: 96.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Chan WK, Chuah KH, Rajaram RB, Lim LL, Ratnasingam J, Vethakkan SR. Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD): A State-of-the-Art Review. J Obes Metab Syndr. 2023;32:197-213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 462] [Article Influence: 154.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Ludwig J, Viggiano TR, McGill DB, Oh BJ. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: Mayo Clinic experiences with a hitherto unnamed disease. Mayo Clin Proc. 1980;55:434-438. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Buzzetti E, Pinzani M, Tsochatzis EA. The multiple-hit pathogenesis of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Metabolism. 2016;65:1038-1048. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1490] [Cited by in RCA: 2309] [Article Influence: 230.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Moretti V, Romeo S, Valenti L. The contribution of genetics and epigenetics to MAFLD susceptibility. Hepatol Int. 2024;18:848-860. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Caussy C, Soni M, Cui J, Bettencourt R, Schork N, Chen CH, Ikhwan MA, Bassirian S, Cepin S, Gonzalez MP, Mendler M, Kono Y, Vodkin I, Mekeel K, Haldorson J, Hemming A, Andrews B, Salotti J, Richards L, Brenner DA, Sirlin CB, Loomba R; Familial NAFLD Cirrhosis Research Consortium. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease with cirrhosis increases familial risk for advanced fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2017;127:2697-2704. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 15.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Long MT, Gurary EB, Massaro JM, Ma J, Hoffmann U, Chung RT, Benjamin EJ, Loomba R. Parental non-alcoholic fatty liver disease increases risk of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in offspring. Liver Int. 2019;39:740-747. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Loomba R, Schork N, Chen CH, Bettencourt R, Bhatt A, Ang B, Nguyen P, Hernandez C, Richards L, Salotti J, Lin S, Seki E, Nelson KE, Sirlin CB, Brenner D; Genetics of NAFLD in Twins Consortium. Heritability of Hepatic Fibrosis and Steatosis Based on a Prospective Twin Study. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:1784-1793. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 230] [Cited by in RCA: 312] [Article Influence: 28.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Holm C. Molecular mechanisms regulating hormone-sensitive lipase and lipolysis. Biochem Soc Trans. 2003;31:1120-1124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 370] [Cited by in RCA: 392] [Article Influence: 17.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Donnelly KL, Smith CI, Schwarzenberg SJ, Jessurun J, Boldt MD, Parks EJ. Sources of fatty acids stored in liver and secreted via lipoproteins in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:1343-1351. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2112] [Cited by in RCA: 2678] [Article Influence: 127.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Fabbrini E, Magkos F, Mohammed BS, Pietka T, Abumrad NA, Patterson BW, Okunade A, Klein S. Intrahepatic fat, not visceral fat, is linked with metabolic complications of obesity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:15430-15435. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 792] [Cited by in RCA: 763] [Article Influence: 44.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (6)] |

| 13. | Samuel VT, Shulman GI. The pathogenesis of insulin resistance: integrating signaling pathways and substrate flux. J Clin Invest. 2016;126:12-22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 686] [Cited by in RCA: 1000] [Article Influence: 100.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Wood PA. Defects in mitochondrial beta-oxidation of fatty acids. Curr Opin Lipidol. 1999;10:107-112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Wasilewska N, Lebensztejn DM. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and lipotoxicity. Clin Exp Hepatol. 2021;7:1-6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Feldstein AE, Werneburg NW, Canbay A, Guicciardi ME, Bronk SF, Rydzewski R, Burgart LJ, Gores GJ. Free fatty acids promote hepatic lipotoxicity by stimulating TNF-alpha expression via a lysosomal pathway. Hepatology. 2004;40:185-194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 586] [Cited by in RCA: 619] [Article Influence: 28.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Wei Y, Rector RS, Thyfault JP, Ibdah JA. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and mitochondrial dysfunction. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:193-199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 240] [Cited by in RCA: 266] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 18. | Wree A, Broderick L, Canbay A, Hoffman HM, Feldstein AE. From NAFLD to NASH to cirrhosis-new insights into disease mechanisms. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;10:627-636. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 396] [Cited by in RCA: 488] [Article Influence: 37.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 19. | Koning M, Herrema H, Nieuwdorp M, Meijnikman AS. Targeting nonalcoholic fatty liver disease via gut microbiome-centered therapies. Gut Microbes. 2023;15:2226922. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Chuaypen N, Asumpinawong A, Sawangsri P, Khamjerm J, Iadsee N, Jinato T, Sutheeworapong S, Udomsawaengsup S, Tangkijvanich P. Gut Microbiota in Patients with Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease without Type 2 Diabetes: Stratified by Body Mass Index. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25:1807. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Larabi AB, Masson HLP, Bäumler AJ. Bile acids as modulators of gut microbiota composition and function. Gut Microbes. 2023;15:2172671. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 219] [Article Influence: 73.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Jiao TY, Ma YD, Guo XZ, Ye YF, Xie C. Bile acid and receptors: biology and drug discovery for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2022;43:1103-1119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 22.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Yang K, Song M. New Insights into the Pathogenesis of Metabolic-Associated Fatty Liver Disease (MAFLD): Gut-Liver-Heart Crosstalk. Nutrients. 2023;15:3970. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Fusco W, Lorenzo MB, Cintoni M, Porcari S, Rinninella E, Kaitsas F, Lener E, Mele MC, Gasbarrini A, Collado MC, Cammarota G, Ianiro G. Short-Chain Fatty-Acid-Producing Bacteria: Key Components of the Human Gut Microbiota. Nutrients. 2023;15:2211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 662] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Li X, He M, Yi X, Lu X, Zhu M, Xue M, Tang Y, Zhu Y. Short-chain fatty acids in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: New prospects for short-chain fatty acids as therapeutic targets. Heliyon. 2024;10:e26991. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Silva YP, Bernardi A, Frozza RL. The Role of Short-Chain Fatty Acids From Gut Microbiota in Gut-Brain Communication. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2020;11:25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 780] [Cited by in RCA: 1914] [Article Influence: 319.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 27. | Umer M, Vaidyanathan R, Nguyen NT, Shiddiky MJA. Circulating tumor microemboli: Progress in molecular understanding and enrichment technologies. Biotechnol Adv. 2018;36:1367-1389. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Xu JY, Li ZP, Zhang L, Ji G. Recent insights into farnesoid X receptor in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:13493-13500. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Yang ZX, Shen W, Sun H. Effects of nuclear receptor FXR on the regulation of liver lipid metabolism in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatol Int. 2010;4:741-748. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 176] [Cited by in RCA: 182] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Liu H, Peng D. Update on dyslipidemia in hypothyroidism: the mechanism of dyslipidemia in hypothyroidism. Endocr Connect. 2022;11:e210002. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Kim D, Kim W, Joo SK, Bae JM, Kim JH, Ahmed A. Subclinical Hypothyroidism and Low-Normal Thyroid Function Are Associated With Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis and Fibrosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16:123-131.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 138] [Cited by in RCA: 147] [Article Influence: 18.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Anyetei-Anum CS, Roggero VR, Allison LA. Thyroid hormone receptor localization in target tissues. J Endocrinol. 2018;237:R19-R34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Sinha RA, Singh BK, Yen PM. Direct effects of thyroid hormones on hepatic lipid metabolism. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2018;14:259-269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 463] [Cited by in RCA: 466] [Article Influence: 58.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Araki O, Ying H, Zhu XG, Willingham MC, Cheng SY. Distinct dysregulation of lipid metabolism by unliganded thyroid hormone receptor isoforms. Mol Endocrinol. 2009;23:308-315. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Cable EE, Finn PD, Stebbins JW, Hou J, Ito BR, van Poelje PD, Linemeyer DL, Erion MD. Reduction of hepatic steatosis in rats and mice after treatment with a liver-targeted thyroid hormone receptor agonist. Hepatology. 2009;49:407-417. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 170] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Erion MD, Cable EE, Ito BR, Jiang H, Fujitaki JM, Finn PD, Zhang BH, Hou J, Boyer SH, van Poelje PD, Linemeyer DL. Targeting thyroid hormone receptor-beta agonists to the liver reduces cholesterol and triglycerides and improves the therapeutic index. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:15490-15495. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 149] [Cited by in RCA: 191] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Choudhary NS, Kumar N, Duseja A. Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptors and Their Agonists in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2019;9:731-739. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Tyagi S, Gupta P, Saini AS, Kaushal C, Sharma S. The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor: A family of nuclear receptors role in various diseases. J Adv Pharm Technol Res. 2011;2:236-240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 509] [Cited by in RCA: 755] [Article Influence: 53.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Grygiel-Górniak B. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors and their ligands: nutritional and clinical implications--a review. Nutr J. 2014;13:17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 811] [Cited by in RCA: 919] [Article Influence: 76.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Hazra S, Miyahara T, Rippe RA, Tsukamoto H. PPAR Gamma and Hepatic Stellate Cells. Comp Hepatol. 2004;3 Suppl 1:S7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Garcia-Tsao G, Friedman S, Iredale J, Pinzani M. Now there are many (stages) where before there was one: In search of a pathophysiological classification of cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2010;51:1445-1449. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 359] [Cited by in RCA: 401] [Article Influence: 25.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Dowman JK, Tomlinson JW, Newsome PN. Pathogenesis of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. QJM. 2010;103:71-83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 472] [Cited by in RCA: 534] [Article Influence: 33.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 43. | Ganz M, Szabo G. Immune and inflammatory pathways in NASH. Hepatol Int. 2013;7 Suppl 2:771-781. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 154] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Parola M, Pinzani M. Liver fibrosis in NAFLD/NASH: from pathophysiology towards diagnostic and therapeutic strategies. Mol Aspects Med. 2024;95:101231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 64.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Nagashimada M, Ota T. Role of vitamin E in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. IUBMB Life. 2019;71:516-522. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Nan YM, Wu WJ, Fu N, Liang BL, Wang RQ, Li LX, Zhao SX, Zhao JM, Yu J. Antioxidants vitamin E and 1-aminobenzotriazole prevent experimental non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in mice. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:1121-1131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Kim DY, Kim J, Ham HJ, Choue R. Effects of d-α-tocopherol supplements on lipid metabolism in a high-fat diet-fed animal model. Nutr Res Pract. 2013;7:481-487. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Jin X, Song L, Liu X, Chen M, Li Z, Cheng L, Ren H. Protective efficacy of vitamins C and E on p,p'-DDT-induced cytotoxicity via the ROS-mediated mitochondrial pathway and NF-κB/FasL pathway. PLoS One. 2014;9:e113257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Kawanaka M, Mahmood S, Niiyama G, Izumi A, Kamei A, Ikeda H, Suehiro M, Togawa K, Sasagawa T, Okita M, Nakamura H, Yodoi J, Yamada G. Control of oxidative stress and reduction in biochemical markers by Vitamin E treatment in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a pilot study. Hepatol Res. 2004;29:39-41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Ersöz G, Günşar F, Karasu Z, Akay S, Batur Y, Akarca US. Management of fatty liver disease with vitamin E and C compared to ursodeoxycholic acid treatment. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2005;16:124-128. [PubMed] |

| 51. | Sanyal AJ, Chalasani N, Kowdley KV, McCullough A, Diehl AM, Bass NM, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Lavine JE, Tonascia J, Unalp A, Van Natta M, Clark J, Brunt EM, Kleiner DE, Hoofnagle JH, Robuck PR; NASH CRN. Pioglitazone, vitamin E, or placebo for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1675-1685. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2642] [Cited by in RCA: 2550] [Article Influence: 159.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (18)] |

| 52. | Hoofnagle JH, Van Natta ML, Kleiner DE, Clark JM, Kowdley KV, Loomba R, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Sanyal AJ, Tonascia J; Non-alcoholic Steatohepatitis Clinical Research Network (NASH CRN). Vitamin E and changes in serum alanine aminotransferase levels in patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38:134-143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Sato K, Gosho M, Yamamoto T, Kobayashi Y, Ishii N, Ohashi T, Nakade Y, Ito K, Fukuzawa Y, Yoneda M. Vitamin E has a beneficial effect on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutrition. 2015;31:923-930. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 146] [Article Influence: 12.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 54. | Scorletti E, Creasy KT, Vujkovic M, Vell M, Zandvakili I, Rader DJ, Schneider KM, Schneider CV. Dietary Vitamin E Intake Is Associated With a Reduced Risk of Developing Digestive Diseases and Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022;117:927-930. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Lavine JE, Schwimmer JB, Van Natta ML, Molleston JP, Murray KF, Rosenthal P, Abrams SH, Scheimann AO, Sanyal AJ, Chalasani N, Tonascia J, Ünalp A, Clark JM, Brunt EM, Kleiner DE, Hoofnagle JH, Robuck PR; Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Clinical Research Network. Effect of vitamin E or metformin for treatment of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in children and adolescents: the TONIC randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2011;305:1659-1668. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 864] [Cited by in RCA: 872] [Article Influence: 58.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Klein EA, Thompson IM Jr, Tangen CM, Crowley JJ, Lucia MS, Goodman PJ, Minasian LM, Ford LG, Parnes HL, Gaziano JM, Karp DD, Lieber MM, Walther PJ, Klotz L, Parsons JK, Chin JL, Darke AK, Lippman SM, Goodman GE, Meyskens FL Jr, Baker LH. Vitamin E and the risk of prostate cancer: the Selenium and Vitamin E Cancer Prevention Trial (SELECT). JAMA. 2011;306:1549-1556. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1218] [Cited by in RCA: 1256] [Article Influence: 83.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL); European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD); European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO). EASL-EASD-EASO Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD). J Hepatol. 2024;81:492-542. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 980] [Article Influence: 490.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 58. | Rinella ME, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Siddiqui MS, Abdelmalek MF, Caldwell S, Barb D, Kleiner DE, Loomba R. AASLD Practice Guidance on the clinical assessment and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2023;77:1797-1835. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1465] [Cited by in RCA: 1598] [Article Influence: 532.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 59. | Krupa KN, Nguyen H, Parmar M. Obeticholic Acid. 2024 Jul 1. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025. [PubMed] |

| 60. | Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Loomba R, Sanyal AJ, Lavine JE, Van Natta ML, Abdelmalek MF, Chalasani N, Dasarathy S, Diehl AM, Hameed B, Kowdley KV, McCullough A, Terrault N, Clark JM, Tonascia J, Brunt EM, Kleiner DE, Doo E; NASH Clinical Research Network. Farnesoid X nuclear receptor ligand obeticholic acid for non-cirrhotic, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (FLINT): a multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;385:956-965. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1726] [Cited by in RCA: 1841] [Article Influence: 167.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 61. | Rinella ME, Dufour JF, Anstee QM, Goodman Z, Younossi Z, Harrison SA, Loomba R, Sanyal AJ, Bonacci M, Trylesinski A, Natha M, Shringarpure R, Granston T, Venugopal A, Ratziu V. Non-invasive evaluation of response to obeticholic acid in patients with NASH: Results from the REGENERATE study. J Hepatol. 2022;76:536-548. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 29.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Healio. 'Unfavorable benefit-risk': FDA panel votes against obeticholic acid approval for NASH [Internet]. Dec 26, 2024. [cited 27 December 2024]. Available from: www.healio.com. |

| 63. | Adorini L, Trauner M. FXR agonists in NASH treatment. J Hepatol. 2023;79:1317-1331. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Harrison SA, Bedossa P, Guy CD, Schattenberg JM, Loomba R, Taub R, Labriola D, Moussa SE, Neff GW, Rinella ME, Anstee QM, Abdelmalek MF, Younossi Z, Baum SJ, Francque S, Charlton MR, Newsome PN, Lanthier N, Schiefke I, Mangia A, Pericàs JM, Patil R, Sanyal AJ, Noureddin M, Bansal MB, Alkhouri N, Castera L, Rudraraju M, Ratziu V; MAESTRO-NASH Investigators. A Phase 3, Randomized, Controlled Trial of Resmetirom in NASH with Liver Fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2024;390:497-509. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 840] [Cited by in RCA: 1130] [Article Influence: 565.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Dutta D, Kamrul-Hasan ABM, Mondal E, Nagendra L, Joshi A, Bhattacharya S. Role of Resmetirom, a Liver-Directed, Thyroid Hormone Receptor Beta-Selective Agonist, in Managing Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Endocr Pract. 2024;30:631-638. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Suvarna R, Shetty S, Pappachan JM. Efficacy and safety of Resmetirom, a selective thyroid hormone receptor-β agonist, in the treatment of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2024;14:19790. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 67. | Cho SW. Selective Agonists of Thyroid Hormone Receptor Beta: Promising Tools for the Treatment of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul). 2024;39:285-287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Viking Therapeutics. Viking Therapeutics Announces Positive 52-Week Histologic Data from Phase 2b VOYAGE Study of VK2809 in Patients with Biopsy-Confirmed Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis (NASH) [Internet]. Jun 4, 2024. [cited 29, December 2024]. Available from: https://ir.vikingtherapeutics.com/2024-06-04-Viking-Therapeutics-Announces-Positive-52-Week-Histologic-Data-from-Phase-2b-VOYAGE-Study-of-VK2809-in-Patients-with-Biopsy-Confirmed-Non-Alcoholic-Steatohepatitis-NASH. |

| 69. | Mahmoudi A, Moallem SA, Johnston TP, Sahebkar A. Liver Protective Effect of Fenofibrate in NASH/NAFLD Animal Models. PPAR Res. 2022;2022:5805398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Athyros VG, Tziomalos K, Gossios TD, Griva T, Anagnostis P, Kargiotis K, Pagourelias ED, Theocharidou E, Karagiannis A, Mikhailidis DP; GREACE Study Collaborative Group. Safety and efficacy of long-term statin treatment for cardiovascular events in patients with coronary heart disease and abnormal liver tests in the Greek Atorvastatin and Coronary Heart Disease Evaluation (GREACE) Study: a post-hoc analysis. Lancet. 2010;376:1916-1922. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 506] [Cited by in RCA: 516] [Article Influence: 32.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Kim S, Ko K, Park S, Lee DR, Lee J. Effect of Fenofibrate Medication on Renal Function. Korean J Fam Med. 2017;38:192-198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Ono H, Atsukawa M, Tsubota A, Arai T, Suzuki K, Higashi T, Kitamura M, Shioda-Koyano K, Kawano T, Yoshida Y, Okubo T, Hayama K, Itokawa N, Kondo C, Nagao M, Iwabu M, Iwakiri K. Impact of pemafibrate in patients with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease complicated by dyslipidemia: A single-arm prospective study. JGH Open. 2024;8:e13057. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Cusi K, Orsak B, Bril F, Lomonaco R, Hecht J, Ortiz-Lopez C, Tio F, Hardies J, Darland C, Musi N, Webb A, Portillo-Sanchez P. Long-Term Pioglitazone Treatment for Patients With Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis and Prediabetes or Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Randomized Trial. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165:305-315. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 592] [Cited by in RCA: 772] [Article Influence: 77.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Gao J, Gu Z. The Role of Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptors in Kidney Diseases. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:832732. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Joshi SR. Saroglitazar for the treatment of dyslipidemia in diabetic patients. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2015;16:597-606. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Gawrieh S, Noureddin M, Loo N, Mohseni R, Awasty V, Cusi K, Kowdley KV, Lai M, Schiff E, Parmar D, Patel P, Chalasani N. Saroglitazar, a PPAR-α/γ Agonist, for Treatment of NAFLD: A Randomized Controlled Double-Blind Phase 2 Trial. Hepatology. 2021;74:1809-1824. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 279] [Article Influence: 55.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Rajesh NA, Drishya L, Ambati MMR, Narayanan AL, Alex M, R KK, Abraham JJ, Vijayakumar TM. Safety and Efficacy of Saroglitazar in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Patients With Diabetic Dyslipidemia-A Prospective, Interventional, Pilot Study. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2022;12:61-67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Zydus Lifesciences Ltd. Zydus receives approval from DCGI for Saroglitazar Magnesium for treatment of Type II Diabetes [Internet]. Ahmedabad: Zydus Lifesciences Ltd. Feb 3, 2020. [cited May 5, 2025]. Available from: https://www.zyduslife.com/public/pdf/pressrelease/Zydus_SaroglitazarMg_Diabetes_approval.pdf. |

| 79. | Central Drugs Standard Control Organization. Drugs [Internet]. New Delhi: Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, Government of India. [cited 5 May 2025]. Available from: https://cdscoonline.gov.in/CDSCO/Drugs. |

| 80. | Bandyopadhyay S, Samajdar SS, Das S. Effects of saroglitazar in the treatment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease or non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2023;47:102174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Francque SM, Bedossa P, Ratziu V, Anstee QM, Bugianesi E, Sanyal AJ, Loomba R, Harrison SA, Balabanska R, Mateva L, Lanthier N, Alkhouri N, Moreno C, Schattenberg JM, Stefanova-Petrova D, Vonghia L, Rouzier R, Guillaume M, Hodge A, Romero-Gómez M, Huot-Marchand P, Baudin M, Richard MP, Abitbol JL, Broqua P, Junien JL, Abdelmalek MF; NATIVE Study Group. A Randomized, Controlled Trial of the Pan-PPAR Agonist Lanifibranor in NASH. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:1547-1558. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 541] [Article Influence: 108.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Inventiva. Inventiva provides an update on its NATiV3 clinical program evaluating lanifibranor in patients with MASH/NASH and its financial position [Internet]. Daix (France): Inventiva. Jul 5, 2024. [cited 5 May 2025]. Available from: https://inventivapharma.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Inventiva-PR-NATiV3-and-fiancial-situation-updates-EN-07-05-2024.pdf. |

| 83. | Inventiva. Inventiva announces completion of enrollment in the Phase 3 NATiV3 clinical trial of lanifibranor in patients with MASH and advanced fibrosis [Internet]. Yahoo Finance. Apr 1, 2025. [cited 5 May 2025]. Available from: https://finance.yahoo.com/news/inventiva-announces-completion-enrollment-phase-210000499.html. |

| 84. | Armstrong MJ, Gaunt P, Aithal GP, Barton D, Hull D, Parker R, Hazlehurst JM, Guo K; LEAN trial team, Abouda G, Aldersley MA, Stocken D, Gough SC, Tomlinson JW, Brown RM, Hübscher SG, Newsome PN. Liraglutide safety and efficacy in patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (LEAN): a multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 2 study. Lancet. 2016;387:679-690. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1100] [Cited by in RCA: 1594] [Article Influence: 159.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 85. | Newsome PN, Buchholtz K, Cusi K, Linder M, Okanoue T, Ratziu V, Sanyal AJ, Sejling AS, Harrison SA; NN9931-4296 Investigators. A Placebo-Controlled Trial of Subcutaneous Semaglutide in Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:1113-1124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 513] [Cited by in RCA: 1409] [Article Influence: 281.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 86. | Gerstein HC, Colhoun HM, Dagenais GR, Diaz R, Lakshmanan M, Pais P, Probstfield J, Botros FT, Riddle MC, Rydén L, Xavier D, Atisso CM, Dyal L, Hall S, Rao-Melacini P, Wong G, Avezum A, Basile J, Chung N, Conget I, Cushman WC, Franek E, Hancu N, Hanefeld M, Holt S, Jansky P, Keltai M, Lanas F, Leiter LA, Lopez-Jaramillo P, Cardona Munoz EG, Pirags V, Pogosova N, Raubenheimer PJ, Shaw JE, Sheu WH, Temelkova-Kurktschiev T; REWIND Investigators. Dulaglutide and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes: an exploratory analysis of the REWIND randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2019;394:131-138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 425] [Cited by in RCA: 438] [Article Influence: 62.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 87. | Klonoff DC, Buse JB, Nielsen LL, Guan X, Bowlus CL, Holcombe JH, Wintle ME, Maggs DG. Exenatide effects on diabetes, obesity, cardiovascular risk factors and hepatic biomarkers in patients with type 2 diabetes treated for at least 3 years. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24:275-286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 361] [Cited by in RCA: 411] [Article Influence: 22.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 88. | Hartman ML, Sanyal AJ, Loomba R, Wilson JM, Nikooienejad A, Bray R, Karanikas CA, Duffin KL, Robins DA, Haupt A. Effects of Novel Dual GIP and GLP-1 Receptor Agonist Tirzepatide on Biomarkers of Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2020;43:1352-1355. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 278] [Article Influence: 46.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 89. | Karimi MA, Gholami Chahkand MS, Dadkhah PA, Sheikhzadeh F, Yaghoubi S, Esmaeilpour Moallem F, Deyhimi MS, Arab Bafrani M, Shahrokhi M, Nasrollahizadeh A. Comparative effectiveness of semaglutide versus liraglutide, dulaglutide or tirzepatide: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Pharmacol. 2025;16:1438318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 90. | Luo Q, Wei R, Cai Y, Zhao Q, Liu Y, Liu WJ. Efficacy of Off-Label Therapy for Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Improving Non-invasive and Invasive Biomarkers: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:793203. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 91. | Kuchay MS, Krishan S, Mishra SK, Farooqui KJ, Singh MK, Wasir JS, Bansal B, Kaur P, Jevalikar G, Gill HK, Choudhary NS, Mithal A. Effect of Empagliflozin on Liver Fat in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes and Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Randomized Controlled Trial (E-LIFT Trial). Diabetes Care. 2018;41:1801-1808. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 298] [Cited by in RCA: 490] [Article Influence: 61.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 92. | Eriksson JW, Lundkvist P, Jansson PA, Johansson L, Kvarnström M, Moris L, Miliotis T, Forsberg GB, Risérus U, Lind L, Oscarsson J. Effects of dapagliflozin and n-3 carboxylic acids on non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in people with type 2 diabetes: a double-blind randomised placebo-controlled study. Diabetologia. 2018;61:1923-1934. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 200] [Cited by in RCA: 298] [Article Influence: 37.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 93. | Arai T, Atsukawa M, Tsubota A, Mikami S, Ono H, Kawano T, Yoshida Y, Tanabe T, Okubo T, Hayama K, Nakagawa-Iwashita A, Itokawa N, Kondo C, Kaneko K, Emoto N, Nagao M, Inagaki K, Fukuda I, Sugihara H, Iwakiri K. Effect of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus: a propensity score-matched analysis of real-world data. Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab. 2021;12:20420188211000243. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 94. | Rena G, Hardie DG, Pearson ER. The mechanisms of action of metformin. Diabetologia. 2017;60:1577-1585. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1320] [Cited by in RCA: 1561] [Article Influence: 173.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 95. | Feng W, Gao C, Bi Y, Wu M, Li P, Shen S, Chen W, Yin T, Zhu D. Randomized trial comparing the effects of gliclazide, liraglutide, and metformin on diabetes with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Diabetes. 2017;9:800-809. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 14.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 96. | Zhang R, Cheng K, Xu S, Li S, Zhou Y, Zhou S, Kong R, Li L, Li J, Feng J, Wu L, Liu T, Xia Y, Lu J, Guo C, Zhou Y. Metformin and Diammonium Glycyrrhizinate Enteric-Coated Capsule versus Metformin Alone versus Diammonium Glycyrrhizinate Enteric-Coated Capsule Alone in Patients with Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2017;2017:8491742. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 97. | Yabiku K, Mutoh A, Miyagi K, Takasu N. Effects of Oral Antidiabetic Drugs on Changes in the Liver-to-Spleen Ratio on Computed Tomography and Inflammatory Biomarkers in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes and Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Clin Ther. 2017;39:558-566. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 98. | Omer Z, Cetinkalp S, Akyildiz M, Yilmaz F, Batur Y, Yilmaz C, Akarca U. Efficacy of insulin-sensitizing agents in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;22:18-23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 99. | Yan J, Yao B, Kuang H, Yang X, Huang Q, Hong T, Li Y, Dou J, Yang W, Qin G, Yuan H, Xiao X, Luo S, Shan Z, Deng H, Tan Y, Xu F, Xu W, Zeng L, Kang Z, Weng J. Liraglutide, Sitagliptin, and Insulin Glargine Added to Metformin: The Effect on Body Weight and Intrahepatic Lipid in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Hepatology. 2019;69:2414-2426. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 207] [Article Influence: 29.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 100. | Li Y, Liu L, Wang B, Wang J, Chen D. Metformin in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Biomed Rep. 2013;1:57-64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 144] [Cited by in RCA: 228] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 101. | Jensen VS, Fledelius C, Zachodnik C, Damgaard J, Nygaard H, Tornqvist KS, Kirk RK, Viuff BM, Wulff EM, Lykkesfeldt J, Hvid H. Insulin treatment improves liver histopathology and decreases expression of inflammatory and fibrogenic genes in a hyperglycemic, dyslipidemic hamster model of NAFLD. J Transl Med. 2021;19:80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 102. | Liu L, Yan H, Xia M, Zhao L, Lv M, Zhao N, Rao S, Yao X, Wu W, Pan B, Bian H, Gao X. Efficacy of exenatide and insulin glargine on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2020;36:e3292. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 15.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 103. | Tang A, Rabasa-Lhoret R, Castel H, Wartelle-Bladou C, Gilbert G, Massicotte-Tisluck K, Chartrand G, Olivié D, Julien AS, de Guise J, Soulez G, Chiasson JL. Effects of Insulin Glargine and Liraglutide Therapy on Liver Fat as Measured by Magnetic Resonance in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes: A Randomized Trial. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:1339-1346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 104. | Boonbee G. Diabetes Mellitus, Insulin, Sulfonylurea and Advanced Fibrosis in Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. J Diabetes Metab. 2014;5. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 105. | Kurniawan J, Teressa M. Insulin Use and The Risk of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Insights and Implications. Acta Med Indones. 2024;56:107-113. [PubMed] |

| 106. | Papazafiropoulou A, Melidonis A. Antidiabetic agents in patients with hepatic impairment. World J Meta-Anal. 2019;7:380-388. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (17)] |

| 107. | Edwards JE, Moore RA. Statins in hypercholesterolaemia: a dose-specific meta-analysis of lipid changes in randomised, double blind trials. BMC Fam Pract. 2003;4:18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 108. | Feingold KR. Cholesterol Lowering Drugs. 2024 Feb 12. In: Endotext [Internet]. South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc.; 2000. [PubMed] |

| 109. | Martin A, Lang S, Goeser T, Demir M, Steffen HM, Kasper P. Management of Dyslipidemia in Patients with Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2022;24:533-546. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 110. | Konyn P, Ahmed A, Kim D. Causes and risk profiles of mortality among individuals with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2023;29:S43-S57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 25.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 111. | Camara Planek MI, Silver AJ, Volgman AS, Okwuosa TM. Exploratory Review of the Role of Statins, Colchicine, and Aspirin for the Prevention of Radiation-Associated Cardiovascular Disease and Mortality. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9:e014668. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 112. | Loomba R, Sanyal AJ, Nakajima A, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Goodman ZD, Harrison SA, Lawitz EJ, Gunn N, Imajo K, Ravendhran N, Akahane T, Boone B, Yamaguchi M, Chatterjee A, Tirucherai GS, Shevell DE, Du S, Charles ED, Abdelmalek MF. Pegbelfermin in Patients With Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis and Stage 3 Fibrosis (FALCON 1): A Randomized Phase 2b Study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024;22:102-112.e9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 29.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 113. | Abdelmalek MF, Sanyal AJ, Nakajima A, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Goodman ZD, Lawitz EJ, Harrison SA, Jacobson IM, Imajo K, Gunn N, Halegoua-DeMarzio D, Akahane T, Boone B, Yamaguchi M, Chatterjee A, Tirucherai GS, Shevell DE, Du S, Charles ED, Loomba R. Pegbelfermin in Patients With Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis and Compensated Cirrhosis (FALCON 2): A Randomized Phase 2b Study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024;22:113-123.e9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 31.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 114. | Harrison SA, Rolph T, Knott M, Dubourg J. FGF21 agonists: An emerging therapeutic for metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis and beyond. J Hepatol. 2024;81:562-576. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |