Published online Dec 5, 2025. doi: 10.4292/wjgpt.v16.i4.110559

Revised: July 15, 2025

Accepted: November 4, 2025

Published online: December 5, 2025

Processing time: 179 Days and 19.6 Hours

Diverticular disease of the intestine is a major gastrointestinal cause of mortality in the United States and the world. It is one of the most common gastrointestinal conditions responsible for hospital admissions.

To identify mortality trends of diverticular disease among adults in the United States, examining regional and demographic variations, as these have not been previously studied. These trends are highly beneficial to studying disease burden and vulnerable populations.

Diverticular disease-related mortality data were extracted as age-adjusted mort

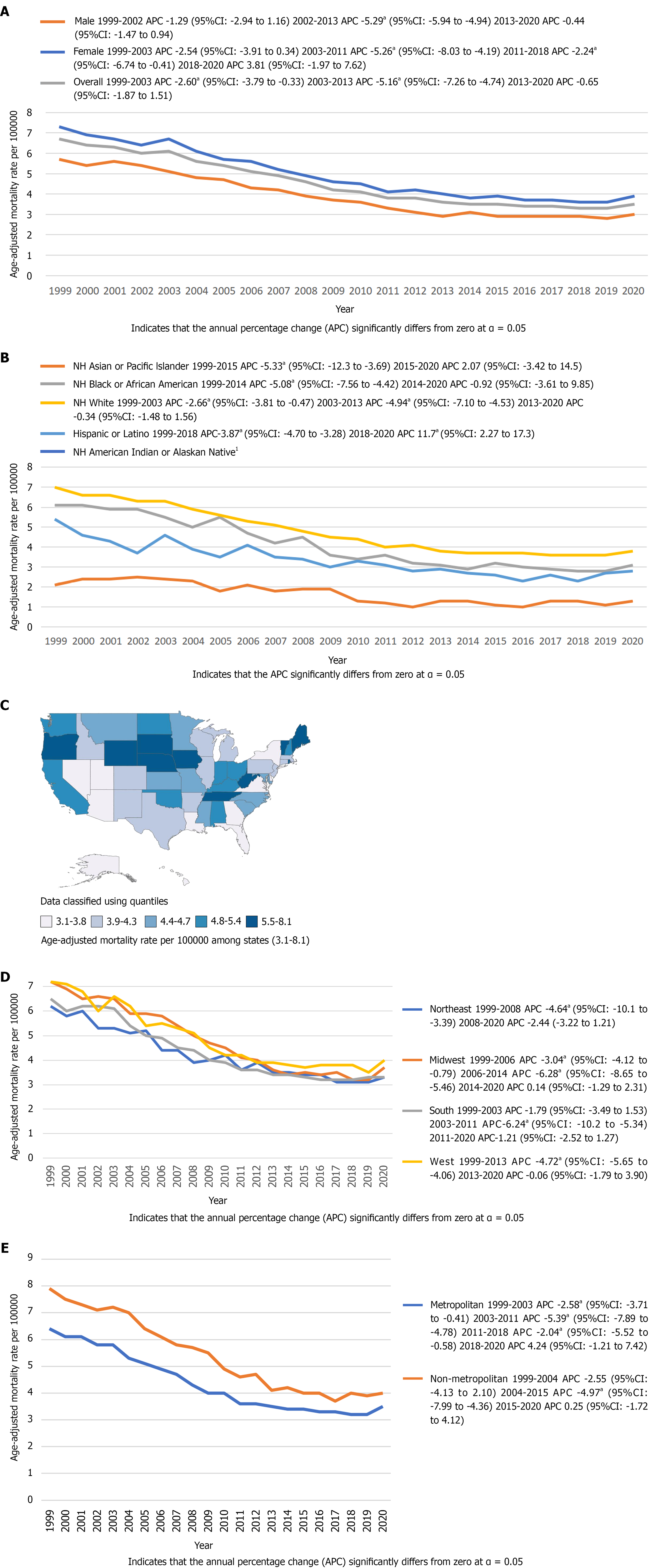

Between 1999 and 2020, a total of 114044 diverticular disease-related deaths were reported among adults ≥ 45 years of age. Our analysis reports progressive decline in mortality with AAMR decreasing from 6.7 in 1999 to 6.1 in 2003 [APC: -2.60; 95% confidence interval (CI): -3.79 to -0.33], after which it further declined to 3.6 in 2013 (APC: -5.16; 95%CI: -7.26 to -4.74), with a minimal decrease to 3.5 in 2020 (APC: -0.65; 95%CI: -1.87 to 1.51). Women had a higher AAMR (4.8) than men (3.8) throughout the study period. The racial analysis reported the highest overall AAMR in non-Hispanic (NH) Whites (4.7), followed by NH Black or African American (3.9), Hispanic or Latino (3.1), and Asian or Pacific Islander (1.5), with unreliable data for the American Indian or Alaska Native population. States in the top 90th percentile, such as Wyoming and Vermont, had approximately double the AAMRs compared to states in the bottom 10th percentile. The mortality rate also exhibited regional disparities, with an overall AAMR higher in the Midwest and West regions (4.7) compared to the Northeast and South regions (4.2), and higher in nonmetropolitan areas (5.4) compared to metropolitan areas (4.2).

Although the annual mortality of diverticular disease has decreased since 1999, there are certain demographic and regional disparities, with mortality rates higher in women, NH White and NH Black adults, Western regions, and nonmetropolitan areas. Further research is needed to identify factors responsible for these disparities and plan appropriate interventions.

Core Tip: There is limited comprehensive data on mortality rates due to diverticular disease. This study aims to investigate the mortality trends of diverticular disease over a two-decade period through demographic and regional stratification. Overall mortality has decreased over two decades; however, females and non-Hispanic whites have higher mortality rates. The study also identifies states and regions showing higher mortality rates. The study suggests that further research is necessary to identify the factors contributing to demographic and regional disparities in mortality, thereby enhancing public health measures for vulnerable populations.

- Citation: Maqbool U, Raza MA, Maqbool A, Chaudhri S, Runau F. Trends in diverticular disease mortality among United States adults (1999–2020) by gender, race, and geographic region. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther 2025; 16(4): 110559

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2150-5349/full/v16/i4/110559.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4292/wjgpt.v16.i4.110559

Gastrointestinal disease is one of the major causes of morbidity and mortality in the United States[1]. Among gastro

This investigation utilized the CDC WONDER database to extract mortality data from the death certificates. This data was examined from 1999 to 2020 to identify diverticular disease of intestine-related mortality in adults aged 45 years or older, using the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems-10th Revision (ICD-10) codes, K57.0 to K57.9. In other studies, these same ICD codes have been used to identify diverticular disease of the intestine[7,8]. The Multiple Cause-of-Death Public Use Registry was used to select only those death certificates in which diverticular disease was identified as the underlying or the contributing cause of death. This data set includes mortality data from 50 states and the District of Columbia. The adults in this study were defined as those who were 45 years or older at the time of death, as the incidence of diverticular disease rises above this age; however, the incidence is also increasing in young adults (18-44 years)[9]. The study did not require Institutional Review Board approval, as it contains de-identified patient data from the CDC database. This aligns with the institutional guidelines of CDC WONDER for the use of this data. The study adheres to the STROBE guidelines for reporting observational data.

Mortality data reported in this study were abstracted for demographics, geographical regions, states, urban-rural classification, and place of death. All data abstraction included adults aged 45 years or older at the time of death. The demographics included stratification of deaths in terms of sex and race/ethnicity. The geographical regions were divided into Northeast, Midwest, South, and West, following the United States Census Bureau Classification, and have been used in similar studies[10]. The study reports diverticular disease-related deaths in the 50 states and the District of Columbia. The urban-rural classification was done by comparing deaths in metropolitan and non-metropolitan areas. This classification was based on the National Center for Health Statistics, which assessed population by urban [large metropolitan area (a population of 1 million or more), medium/small metropolitan area (population ranging from 50000-999999)] and rural (population less than 50000) counties by the 2013 United States census classification[11]. The mortality data compared deaths through their location, including those at medical facilities (outpatient, inpatient, emergency room, death on arrival, and unknown status), homes, nursing homes/Long-term care facilities, and hospices. The racial mortality data were classified into Non-Hispanic (NH) White, NH Black or African American, NH American Indian or Alaskan Native, NH Asian or Pacific Islander, and Hispanic or Latino. Similar data abstraction methods have been used in previous analyses of CDC WONDER[12].

The study aimed to examine diverticular disease-related mortality from 1999 to 2020 to identify national trends. This was done by extracting crude mortality rates and age-adjusted mortality rates (AAMRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) per 100000 United States population from the death certificate data retrieved from the CDC database, stratified by sex, race, age, geographical regions, states, urban-rural status, and location of death. This data also reported the total number of deaths and the population in the specified year. We obtained the crude mortality rates by dividing the total number of deaths by the United States population in that particular year. The AAMRs, on the other hand, were obtained by dividing the total number of deaths by the standard United States population in the year 2000 to obtain standardized rates[13]. These standardized age-adjusted rates were then analyzed using the Joinpoint Regression Program (Version 5.0.2, National Cancer Institute) to generate Annual Percent Changes (APCs) with 95%CIs in AAMRs[14,15]. This program employed long-linear regression analysis to identify changes in AAMRs from 1999 to 2020 and generate APCs, which helped identify trends in diverticular disease mortality from 1999 to 2020. Depending on the mortality slope showing a significant difference from zero using 2-tailed t-testing, the APCs were accordingly classified as increasing or decreasing. These analyses yielded a P value that was considered statistically significant when less than 0.05.

Overall, 114044 deaths were reported to be linked to diverticular disease of the intestine in adults who were 45 years or older, according to the death certificates retrieved from CDC WONDER from 1999 to 2020 (Supplementary Table 1). An analysis of deaths through their location reported 110914 deaths; 65.9% of these were reported at medical facilities, 16.8% at nursing homes/Long-term care facilities, 4% at hospices, and 13.1% at homes (Supplementary Table 2).

The AAMRs for diverticular disease of the intestine in 1999 was 6.7 (95%CI: 6.5-6.9). The AAMR dropped to 3.5 (95%CI: 3.4-3.6) in 2020. A joinpoint regression analysis showed that from 1999 to 2003, the AAMR declined with an APC of -2.60 (95%CI: -3.79 to -0.33). The AAMR further decreased from 2003-2013, showing an APC of -5.16 (95%CI: -7.26 to -4.74), while from 2013-2020, there was a slight decrease with an APC of -0.65 (95%CI: -1.87-1.51) (Figure 1A, Supplementary Tables 3 and 4).

During the longitudinal examination from 1999 to 2020, it was found that females had a higher overall AAMR of 4.8 (95%CI: 4.8-4.9) compared to males, whose overall AAMR was 3.8 (95%CI: 3.7-3.8) in the target population. The AAMR of males in 1999 was 5.7 (95%CI: 5.4-5.9), which decreased to 3 (95%CI: 2.9-3.2) in 2020. A trend analysis of these AAMRs showed an annual percent decrease of -1.29 (95%CI: -2.94-1.16) from 1999-2002 and a further steady annual decline of -5.29 (95%CI: -5.94 to -4.94) from 2002 to 2013. From 2013 to 2020, the AAMR in males remained relatively stable, with an APC of -0.44 (95%CI: -1.47-0.94). In the case of females, the AAMR was 7.3 (95%CI: 7.1-7.5) in 1999. This steadily declined to an AMMR of 6.7 (95%CI: 6.5-6.9) with an annual percent decrease of -2.54 (95%CI: -3.91-0.34). The trend analysis showed further reduction in female AAMR from 2003 to 2011 with an APC of -5.26 (95%CI: -8.03 to -4.19) and from 2011 to 2018 with an APC of -2.24 (95%CI: -6.74 to -0.41). The AAMR in females showed a significant escalation from 3.6 (95%CI: 3.5-3.7) in 2018 to 3.9 (95%CI: 3.8-4) in 2020, with an APC of 3.81 (95%CI: -1.97-7.62) (Figure 1A, Supplementary Tables 3 and 4).

The mortality data stratified by race revealed that diverticular disease-related AAMR was highest in the NH White population [4.7 (95%CI: 4.6-4.7)], followed by NH Black or African American community [3.9 (95%CI: 3.9-4)], Hispanic or Latino population [3.1 (95%CI: 3.1-3.2)], and NH Asian or Pacific Islander [1.5 (95%CI: 1.4-1.6)]. The AAMRs for the NH American Indian or Alaska Native population were unreliable and not included. This is because the number of mort

The study period reported different AAMRs in different states of the United States. The lowest diverticular disease-related overall AAMR was recorded as 3.1 (95%CI: 2.8 to 3.4) for Hawaii. In contrast, Vermont had the highest overall AAMR, at 8.1 (95%CI: 7.3 to 8.8). All other states had their AAMRs scattered between these two opposites. The states with AAMRs in the lowest 10th percentile included Hawaii, Nevada, Arizona, Louisiana, Florida, Georgia, and Utah. The states with AAMRs in the top 90th percentile included West Virginia, Nebraska, Iowa, Rhode Island, Maine, South Dakota, Wyoming, and Vermont (Figure 1C, Supplementary Table 6).

The mortality data stratified by census regions showed that from 1999 to 2020, the Midwest and West had a higher overall AAMR of 4.7 (95%CI: 4.7-4.8) compared to the Northeast and South regions’ overall AAMR of 4.2 (95%CI: 4.1-4.3). The AAMR of the Midwest showed considerable reduction from 1999 to 2006 and 2006 to 2014, with an annual percent decrease of -3.04 (95%CI: -4.12 to -0.79) and -6.28 (95%CI: -8.65 to -5.46), respectively. It remained relatively constant from 2014 to 2020 with an APC of 0.14 (95%CI: -1.29-2.31). The AAMR of the West region had a consistent annual percent decline of -4.72 (95%CI: -5.65 to -4.06) from 1999 to 2013, after which it remained reasonably stable till 2020 with an APC of -0.06 (95%CI: -1.79-3.90). The Northeast region also showed an annual percent decline of -4.64 (95%CI: -10.1 to -3.39) and -2.44 (95%CI, -3.22-1.21) from 1999 to 2008 and 2008 to 2020, respectively. The AAMR of the South lessened by an APC of -1.79 (95%CI: -3.49-1.53) from 1999 to 2003. It then reduced further by an annual percent decline of -6.24 (95%CI: -10.2 to -5.34) from 2003 to 2011 and -1.21 (95%CI: -2.52 to 1.27) till 2020 (Figure 1D, Supplementary Tables 3 and 7).

This longitudinal study revealed that nonmetropolitan areas had a higher overall AAMR of 5.4 (95%CI: 5.3 to 5.4) compared to the metropolitan overall AAMR of 4.2 (95%CI: 4.2 to 4.3) due to the diverticular disease of intestine from 1999 to 2020. The AAMR in nonmetropolitan areas had a considerable annual percent increase of 2.55 (95%CI: -4.13 to 2.10) from 1999 to 2004. It declined by a yearly percentage of -4.97 (95%CI: -7.99 to -4.36) till 2015 but increased again with an APC of 0.25 (95%CI: 1.72 to 4.12) till 2020. The metropolitan areas, on the other hand, had a consistent annual percent decline of -2.58 (95%CI: -3.71 to -0.41), -5.39 (95%CI: -7.89 to -4.78), and -2.04 (95%CI: -5.52 to -0.58) from 1999-2003, 2003-2011, and 2011-2018, respectively. However, it showed a considerable annual percent increase of 4.24 (-1.21 to 7.42) from 2018 to 2020 (Figure 1E, Supplementary Tables 3 and 8).

This retrospective longitudinal study has revealed some key findings regarding mortality rates of diverticular disease in adults in the United States over 21 years that have profound public health implications. The death certificate data from the CDC WONDER database shows that the annual mortality due to diverticular disease has declined consistently and progressively from 1999 to 2013. After that, the yearly mortality has remained relatively stable, with only a minimal annual percent decrease till 2020. This decrease in annual mortality is likely attributable to more disease screening and awareness, better healthcare resources, and treatment modalities over the past two decades, as the prevalence of diverticular disease has risen, in contrast, indicated by increased hospitalization rates[16]. The mortality rates have demonstrated spikes in the terminal part of the study period in some sub-groups, including women and the Midwest and West regions. These trend changes may be explained by shifts in healthcare access, broader systemic factors, and the impact of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic in 2020. There has been an increased prevalence of diverticular disease in the past two decades, particularly in patients younger than 50 years of age[17,18]. This enhancement is ascribable to decreased physical activity, a rise in obesity, and reduced fiber intake[19,20].

The study shows significant sex-stratified differences in mortality, where the overall mortality due to diverticular disease is higher in women compared to men from 1999 to 2020. These findings concur with the findings of another study that reported higher mortality due to diverticulitis in females compared to males in the United States[21]. These mortality rates differ from the general mortality trends, where males generally have higher mortality due to most causes of death[22,23]. It is reported that the incidence of diverticular disease is higher in men before 50 years of age, but higher in women above 50 years of age[24]. Another study, however, reports that females have reduced odds of diverticulosis at any age compared to males, based on colonoscopy data gathered from 2000 to 2012[25]. Nonetheless, our study demonstrates that after a consistent decrease in the female mortality rate from 1999 to 2018, it increased considerably from 2018 to 2020, requiring investigation for probable causes. The mortality rate in males shows a progressive downward trend.

The study also demonstrates significant racial differences in diverticular disease-related mortality. The mortality rate was highest in the NH White community and lowest in the NH Asian or Pacific Islander community. These mortality rates align with the racial differences in the prevalence of diverticulosis observed in colonoscopy data[25]. The mortality rates of the NH Asian or Pacific Islander population and Hispanic or Latino population have demonstrated a considerable increase close to 2020 after years of consistent decrease. In light of these mortality rates, a culturally tailored approach should be adopted to plan interventions to target ethnically vulnerable groups.

The analysis also highlights remarkable differences in diverticular disease mortality across different states, where states such as West Virginia, Nebraska, Iowa, Rhode Island, Maine, South Dakota, Wyoming, and Vermont had almost double the mortality rates compared to states like Hawaii, Nevada, Arizona, Louisiana, Florida, Georgia, and Utah. This difference is likely attributable to multifactorial causes and requires policy changes in the highly affected states to lower mortality.

A noteworthy point this analysis disclosed was the higher mortality rates in nonmetropolitan areas compared to metropolitan areas over 21 years of study. Although the mortality trends show a downward progression in both regions, the mortality rates fairly escalated in the urban areas from 2018 to 2020, which is of concern. The increased burden of mortality in nonmetropolitan areas is likely due to low socioeconomic status in rural areas and limited access to primary care physicians and specialists. A study reveals that from 2002 to 2015, the number of primary care physicians in rural areas declined twice as much as in urban areas, which likely explains these disparities[26].

A geographical analysis demonstrated that the Midwest and West had higher mortality due to diverticular disease than the Northeast and South regions from 1999 to 2020. A study investigating diverticulitis admissions from 1998 to 2005 reported the highest number of admissions in the Northeast region due to diverticulitis[16]. Our investigation, however, reveals that mortality due to diverticulitis is higher in the Midwest and Western regions. These regional disparities are partly attributable to differences in lifestyles, dietary habits, quality of healthcare, and Medicaid regulations. Extensive longitudinal studies are necessary to identify the primary factors responsible for these disparities and to plan interventions accordingly.

While our study reports some critical aspects of diverticular disease mortality, it has certain limitations. The data extracted from the CDC WONDER was based on ICD-10 codes on death certificates. There is an inherent risk of omission of some deaths where diverticular disease was a cause of death. The data also does not provide socioeconomic determinants of patients, the treatments received, investigative findings (such as colonoscopy results), dietary and behavioral factors, and a family history of diverticulosis, all of which would help better understand the epidemiology and prevalence of diverticular disease.

Although the prevalence of diverticular disease is increasing in the United States, our study reports a declining trend in the AAMRs of diverticular disease in adults from 1999 to 2020. The higher AAMRs were observed in females, NH Whites, NH Blacks, and in the states of West Virginia, Nebraska, Iowa, Rhode Island, Maine, South Dakota, Wyoming, and Vermont, as well as in the Midwest and West regions, and nonmetropolitan areas. Further research is necessary to identify the contributing factors to mortality in vulnerable populations and to intensify efforts for prevention and treatment.

| 1. | Everhart JE, Ruhl CE. Burden of digestive diseases in the United States part II: lower gastrointestinal diseases. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:741-754. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 290] [Cited by in RCA: 346] [Article Influence: 20.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Rezapour M, Ali S, Stollman N. Diverticular Disease: An Update on Pathogenesis and Management. Gut Liver. 2018;12:125-132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Peery AF, Crockett SD, Barritt AS, Dellon ES, Eluri S, Gangarosa LM, Jensen ET, Lund JL, Pasricha S, Runge T, Schmidt M, Shaheen NJ, Sandler RS. Burden of Gastrointestinal, Liver, and Pancreatic Diseases in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:1731-1741.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 697] [Cited by in RCA: 726] [Article Influence: 66.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Carabotti M, Falangone F, Cuomo R, Annibale B. Role of Dietary Habits in the Prevention of Diverticular Disease Complications: A Systematic Review. Nutrients. 2021;13:1288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kim YS. [Diagnosis and Treatment of Colonic Diverticular Disease]. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2022;79:233-243. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Li D, Baxter NN, McLeod RS, Moineddin R, Wilton AS, Nathens AB. Evolving practice patterns in the management of acute colonic diverticulitis: a population-based analysis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2014;57:1397-1405. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Erichsen R, Strate L, Sørensen HT, Baron JA. Positive predictive values of the International Classification of Disease, 10th edition diagnoses codes for diverticular disease in the Danish National Registry of Patients. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2010;3:139-142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Cirocchi R, Popivanov G, Corsi A, Amato A, Nascimbeni R, Cuomo R, Annibale B, Konaktchieva M, Binda GA. The Trends of Complicated Acute Colonic Diverticulitis-A Systematic Review of the National Administrative Databases. Medicina (Kaunas). 2019;55:744. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Munie ST, Nalamati SPM. Epidemiology and Pathophysiology of Diverticular Disease. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2018;31:209-213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Al Hussein Al Awamlh B, Patel N, Ma X, Calaway A, Ponsky L, Hu JC, Shoag JE. Variation in the Use of Active Surveillance for Low-Risk Prostate Cancer Across US Census Regions. Front Oncol. 2021;11:644885. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Uddin J, Zhu S, Malla G, Levitan EB, Rolka DB, Carson AP, Long DL. Regional and rural-urban patterns in the prevalence of diagnosed hypertension among older U.S. adults with diabetes, 2005-2017. BMC Public Health. 2024;24:1326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Friede A, Reid JA, Ory HW. CDC WONDER: a comprehensive on-line public health information system of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Am J Public Health. 1993;83:1289-1294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Klein RJ, Schoenborn CA. Age adjustment using the 2000 projected U.S. population. Healthy People 2010 Stat Notes. 2001;1-10. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 14. | Anderson RN, Rosenberg HM. Age standardization of death rates: implementation of the year 2000 standard. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 1998;47:1-16, 20. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Kim HJ, Chen HS, Midthune D, Wheeler B, Buckman DW, Green D, Byrne J, Luo J, Feuer EJ. Data-driven choice of a model selection method in joinpoint regression. J Appl Stat. 2023;50:1992-2013. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Nguyen GC, Sam J, Anand N. Epidemiological trends and geographic variation in hospital admissions for diverticulitis in the United States. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:1600-1605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (6)] |

| 17. | Ricciardi R, Baxter NN, Read TE, Marcello PW, Hall J, Roberts PL. Is the decline in the surgical treatment for diverticulitis associated with an increase in complicated diverticulitis? Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52:1558-1563. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Etzioni DA, Mack TM, Beart RW Jr, Kaiser AM. Diverticulitis in the United States: 1998-2005: changing patterns of disease and treatment. Ann Surg. 2009;249:210-217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 457] [Cited by in RCA: 420] [Article Influence: 24.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | King DE, Mainous AG 3rd, Carnemolla M, Everett CJ. Adherence to healthy lifestyle habits in US adults, 1988-2006. Am J Med. 2009;122:528-534. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 217] [Cited by in RCA: 217] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Aldoori WH, Giovannucci EL, Rockett HR, Sampson L, Rimm EB, Willett WC. A prospective study of dietary fiber types and symptomatic diverticular disease in men. J Nutr. 1998;128:714-719. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 204] [Cited by in RCA: 159] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Sell NM, Perez NP, Stafford CE, Chang D, Bordeianou LG, Francone TD, Kunitake H, Ricciardi R. Are There Variations in Mortality From Diverticular Disease By Sex? Dis Colon Rectum. 2020;63:1285-1292. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Zhao E, Crimmins EM. Mortality and morbidity in ageing men: Biology, Lifestyle and Environment. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2022;23:1285-1304. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Wong MD, Chung AK, Boscardin WJ, Li M, Hsieh HJ, Ettner SL, Shapiro MF. The contribution of specific causes of death to sex differences in mortality. Public Health Rep. 2006;121:746-754. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Strate LL, Morris AM. Epidemiology, Pathophysiology, and Treatment of Diverticulitis. Gastroenterology. 2019;156:1282-1298.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 244] [Cited by in RCA: 306] [Article Influence: 43.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Peery AF, Keku TO, Galanko JA, Sandler RS. Sex and Race Disparities in Diverticulosis Prevalence. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18:1980-1986. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Basu S, Berkowitz SA, Phillips RL, Bitton A, Landon BE, Phillips RS. Association of Primary Care Physician Supply With Population Mortality in the United States, 2005-2015. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179:506-514. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 182] [Cited by in RCA: 361] [Article Influence: 51.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/