Published online Dec 5, 2025. doi: 10.4292/wjgpt.v16.i4.110271

Revised: July 4, 2025

Accepted: September 28, 2025

Published online: December 5, 2025

Processing time: 184 Days and 19.5 Hours

The gut microbiota plays a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of liver diseases, par

Core Tip: The gut microbiota is a key player in the progression of liver diseases, especially hepatic encephalopathy, by influencing ammonia levels, inflammation, and neurocognitive function. This review discussed current and emerging therapies that target the gut-liver axis, including non-absorbable disaccharides, antibiotics, probiotics, synbiotics, postbiotics, and fecal microbiota transplantation. Novel agents such as bile acid modulators and microbiome-targeted molecules were also explored. Modulating gut microbiota may not only alleviate hepatic encephalopathy but also benefit conditions like metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease and cirrhosis, facilitating the way for more personalized and effective liver disease management strategies.

- Citation: Vargas-Beltran AM, Mialma-Omana SJ, Vivanco-Tellez DO. Targeting gut microbiota in liver disease: A pharmacological approach for hepatic encephalopathy and beyond. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther 2025; 16(4): 110271

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2150-5349/full/v16/i4/110271.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4292/wjgpt.v16.i4.110271

The gastrointestinal tract harbors a dense and diverse community of commensal microbes that play a vital role in maintaining physiological balance and are increasingly recognized as key contributors to disease development[1,2]. Among the organs most affected by microbial activity is the liver, which is closely connected to the gut through the portal circulation. This gut-liver axis involves bidirectional communication driven mainly by the gut microbiota and its metabolites, which can influence liver health or contribute to hepatic injury. The gastrointestinal barrier, composed of epithelial and endothelial cells along with innate and adaptive immune components, helps regulate this interaction. Blood from the intestines drains into the liver via the portal vein, making it a central conduit for microbial signals and metabolites and a crucial component in the pathogenesis of many liver diseases[3,4].

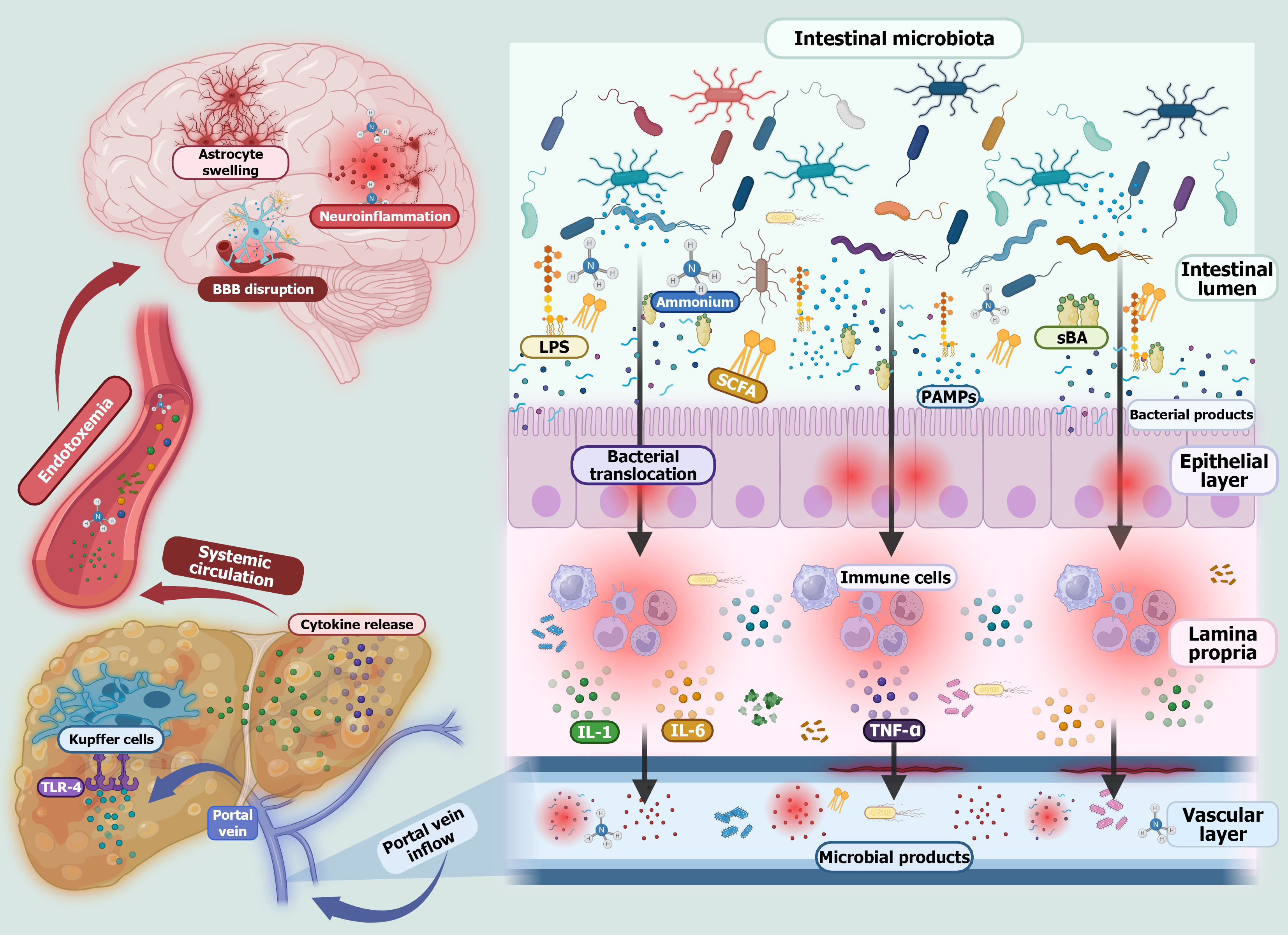

Hepatic encephalopathy (HE) is a complex neuropsychiatric disorder primarily associated with advanced liver disease, especially cirrhosis, and is closely linked to alterations within the gut-liver axis. A central contributor to its pathogenesis is gut dysbiosis, an imbalance characterized by the overgrowth of pathogenic bacteria and a reduction in beneficial microbial populations. This shift disrupts the production of microbial metabolites and compromises intestinal barrier integrity, promoting bacterial translocation, systemic inflammation, and endotoxemia. One of the hallmark features of HE is the accumulation of neurotoxic substances, including ammonia, phenylethylamine, indoles, and oxindoles. In healthy individuals these compounds are detoxified by the liver; however, in cirrhosis impaired hepatic clearance allows them to accumulate, leading to neuroinflammation and cognitive dysfunction (Figure 1)[5,6].

The gut-liver-brain axis further highlights the role of microbiota in HE. Dysbiosis not only increases neurotoxin pro

Therapies aimed at correcting dysbiosis, including probiotics, antibiotics like rifaximin, and fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT), seek to restore microbial balance and reduce neurotoxin levels. These strategies have shown encouraging results in mitigating cognitive decline and improving overall outcomes in patients with HE[9].

Non-absorbable disaccharides, such as lactulose and lactitol, are well-established therapies for managing HE, mainly in patients with cirrhosis. Their therapeutic effect is primarily achieved through modulation of the gut microbiota and reduction of ammonia production and absorption, a key neurotoxin implicated in HE pathogenesis. These compounds bypass absorption in the small intestine and are fermented by colonic bacteria into short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), such as acetate, in the colon. This fermentation process lowers colonic pH, creating an acidic environment that suppresses urease-producing, ammonia-generating bacteria. Additionally, their osmotic action draws water into the bowel lumen, increasing stool volume and promoting intestinal transit, which facilitates the excretion of ammonia[10].

A Cochrane review by Gluud et al[11] demonstrated that non-absorbable disaccharides are associated with significant improvements in both mortality and HE severity compared with placebo or no treatment although the quality of evidence varies. The review found no significant difference in efficacy between lactulose and lactitol, supporting the use of either agent based on availability and patient tolerance.

Beyond ammonia-lowering effects emerging evidence suggests these agents may also positively shape the gut mic

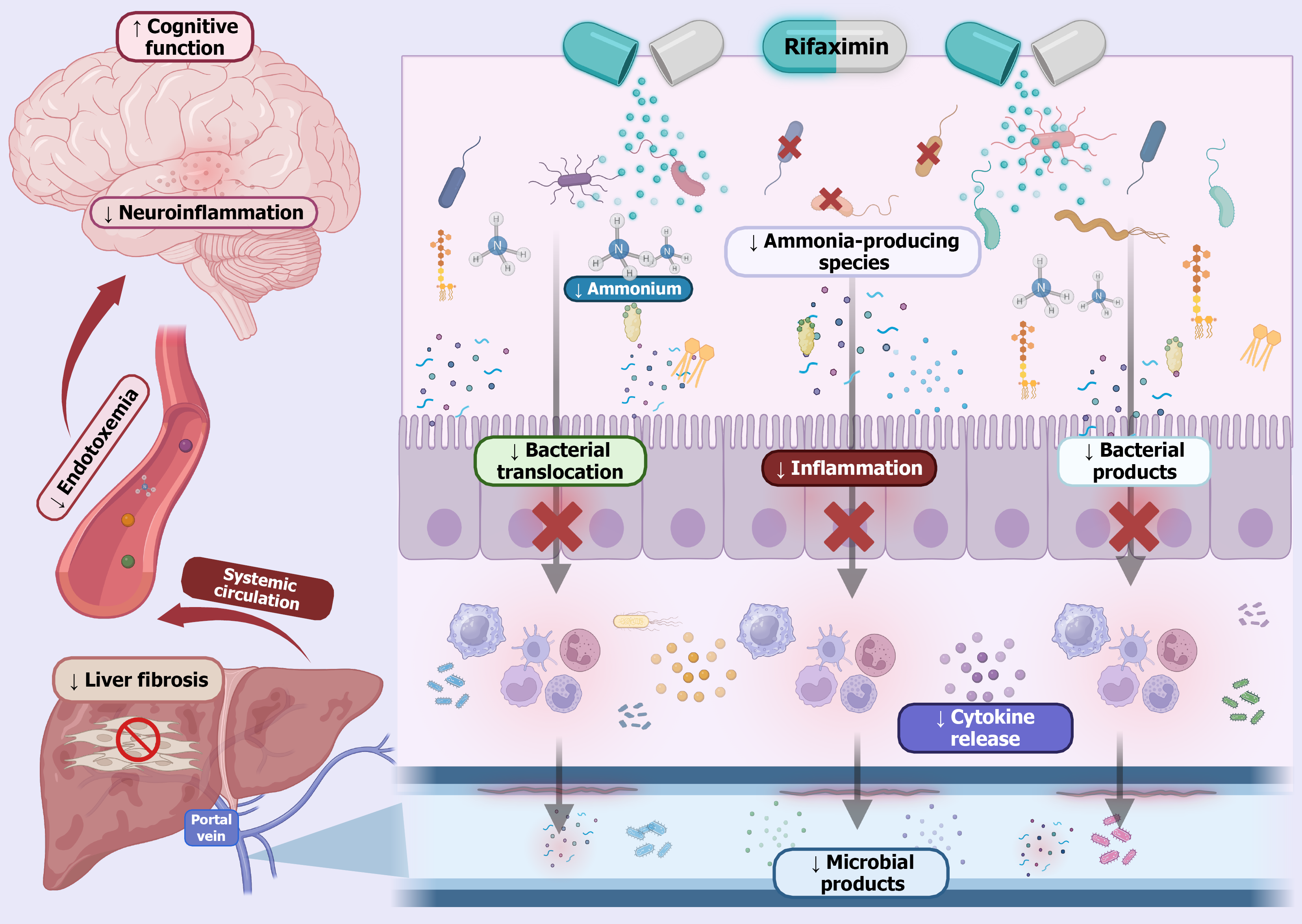

Rifaximin, a non-absorbable, broad-spectrum antibiotic, is a cornerstone therapy for the prevention of recurrent HE in patients with liver cirrhosis. Its effectiveness has been consistently demonstrated in multiple clinical trials, and it is wi

Rather than causing widespread microbial eradication, rifaximin selectively targets pathogenic bacteria associated with HE while fostering a more favorable gut microbial profile. This contributes to a reduction in gut-derived endotoxins and systemic inflammation, two key drivers of HE. Mechanistically, rifaximin downregulates toll-like receptor expression on immune cells such as neutrophils and suppresses proinflammatory cytokines like tumor necrosis factor alpha, thereby dampening inflammatory signaling. Another critical aspect of the action of rifaximin is its role in preserving intestinal barrier integrity. By enhancing gut barrier function, it limits bacterial translocation and lowers systemic endotoxemia, both of which are implicated in the progression of HE (Figure 2)[15,16].

Importantly, the therapeutic benefits of rifaximin are achieved without significantly disturbing the overall diversity of the gut microbiome. Its minimal systemic absorption and action at subinhibitory concentrations reduce the selective pressure that typically drives antibiotic resistance, making it a relatively safe long-term option in HE management[17].

Probiotics have emerged as a promising adjunctive therapy for HE, particularly in restoring gut microbial balance. Some meta-analyses have highlighted their ability to lower systemic ammonia levels, improving cognitive performance and reducing the incidence of minimal HE (MHE)[18,19], which represents the earliest and mildest form of HE and is characterized by subtle cognitive and psychomotor impairments that are not clinically obvious but can be detected through specialized neuropsychological testing. Although less severe than overt HE, MHE significantly affects patient quality of life and functional abilities, such as driving and work performance, and may progress to overt HE if left untreated[18,19].

Comparative trials have assessed probiotics against established therapies such as lactulose and rifaximin. While pro

The therapeutic effect of probiotics is primarily attributed to their ability to reshape gut microbiota. They promote the growth of beneficial bacteria like Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium while suppressing harmful species such as Enterobacter and Enterococcus. This shift reduces gut-derived endotoxins and systemic inflammation, contributing to symptomatic relief and neurocognitive improvement in patients with HE[21].

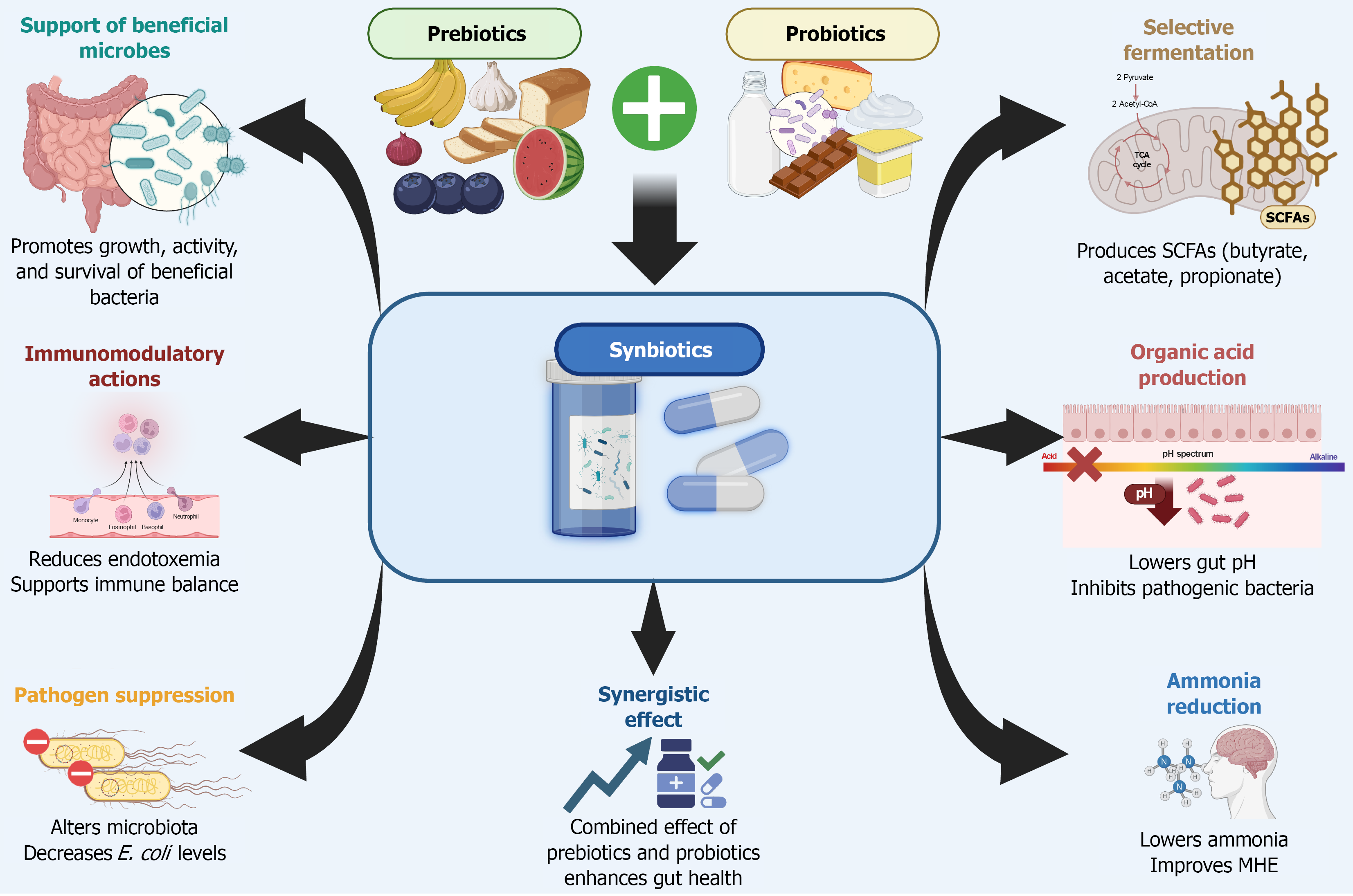

Synbiotics, which combine both probiotics and prebiotics in a single formulation, aim to optimize the therapeutic potential of each component by promoting the growth and activity of beneficial gut microbes. Although the theoretical advantage lies in their synergistic effects, clinical evidence supporting this synergy remains limited[21].

First, synbiotics restore microbial diversity and increase the abundance of beneficial commensals, such as Lactobacillus. This rebalancing of the microbiota helps suppress the overgrowth of pathogenic bacteria and reduces the production of harmful microbial metabolites. Second, synbiotics enhance intestinal barrier integrity by regulating tight junction proteins and mucins, thereby reducing gut permeability. This limits the translocation of endotoxins and other microbial products into the portal circulation.

Third, synbiotics modulate the metabolic activity of the gut microbiome, notably by increasing the production of SCFAs such as butyrate and acetate[22,23]. In a small single-center study, a synbiotic containing Bifidobacterium longum and fructo-oligosaccharides showed cognitive improvements and reduced serum ammonia levels. Similarly, in patients with MHE, both synbiotics and prebiotics alone were effective in reversing MHE in approximately half of the par

Moreover, synbiotics have demonstrated potential in improving neurocognitive function as reflected by enhanced performance on tests like the Trail Making Test and Inhibitory Control Test even in the absence of significant changes in ammonia levels. Clinical trials have also associated synbiotics with improved liver function, including reductions in ammonia and better Child-Turcotte-Pugh scores. Overall, synbiotics are well-tolerated and represent a promising, noninvasive alternative for managing MHE[25,26].

The limitations of using synbiotics include heterogeneity in clinical efficacy, lack of standardized formulations, and insufficient long-term safety data. Clinical studies and preclinical models demonstrate that synbiotics can improve gut barrier function and restore beneficial microbial populations, but the magnitude and consistency of these effects vary widely depending on the specific strains and prebiotic components used as well as patient-specific factors such as base

Postbiotics, bioactive metabolites and structural components derived from probiotics, are emerging as promising microbiome-based therapies. Although their role in HE remains largely underexplored, growing evidence highlights their potential in modulating host physiology. These compounds, which include microbial cell wall components such as peptidoglycans, lipoteichoic acids, and immunomodulatory proteins like p40 and p75, interact with host immune cells to modulate cytokine production, promote anti-inflammatory responses, and regulate both innate and adaptive immune pathways. In addition to their immunoregulatory functions, postbiotics promote intestinal barrier integrity by upregulating tight junction proteins, stimulating mucin secretion, and activating epithelial cell survival pathways.

Furthermore, they can trigger antioxidant defenses through pathways such as Nrf2/ARE signaling, mitigate oxidative stress, and inhibit pro-inflammatory cascades like toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)/nuclear factor kappa B[28-30]. These compounds, particularly SCFAs, are generated through bacterial fermentation of non-digestible polysaccharides and serve as a vital energy source for colonocytes. Beyond their nutritional value SCFAs play a critical role in maintaining intestinal barrier integrity, modulating immune responses, and promoting tolerance to commensal microbes. While direct clinical evidence in HE is still limited, postbiotics have shown promise in related conditions such as metabolic dysfun

Postbiotics face several limitations in modulating the gut microbiota. As non-viable agents, they cannot colonize or interact dynamically with the host microbiota, resulting in transient effects and minimal long-term impact on microbial composition. Their immunomodulatory and barrier-enhancing actions are often dose-dependent, requiring high or re

In cirrhosis reduced bile acid production disrupts the gut microbiota, leading to a decline in beneficial bacterial groups such as Lachnospiraceae, Ruminococcaceae, and Clostridiales, which are essential for SCFA production and maintenance of gut barrier integrity. Additionally, impaired hepatic detoxification and the presence of portosystemic shunts allow bacterial products, including endotoxins and ammonia, to enter the systemic circulation, contributing to systemic inflammation and cognitive decline[35].

Early-phase clinical trials reported improvements in cognitive performance and gut mucosal microbial diversity following FMT. Specifically, increases in beneficial bacteria such as Lachnospiraceae and Ruminococcaceae along with reductions in harmful groups like Streptococcaceae and Veillonellaceae have been observed. These microbial shifts are associated with enhanced brain function and lower levels of systemic inflammation, including decreased serum LPS-binding protein.

Clinical studies have shown that FMT is both safe and potentially effective in reducing the recurrence of HE. The THEMATIC trial, a phase II randomized, placebo-controlled study, demonstrated that FMT was well-tolerated with no serious adverse events directly linked to the treatment. Participants who received FMT experienced a notable reduction in HE recurrence compared with the placebo group regardless of the method of delivery, dosage, or donor variation. These findings support the role of FMT as a promising adjunctive strategy in HE management[35-37].

Furthermore, meta-analyses and systematic reviews support the therapeutic potential of FMT in HE[37-39], demon

Bile acid modulators have gained attention as potential treatments for HE due to their influence on bile acid signaling pathways. Dysregulation of these pathways may contribute to neuroinflammation and increased blood-brain barrier permeability in liver disease. In preclinical models, such as rats with thioacetamide-induced cirrhosis, bile acids have been shown to worsen HE symptoms by activating inflammatory pathways and receptors like TGR5. Certain bile acids can act on the blood-brain barrier and increase permeability themselves. It is believed that these bile acids act on the tight junction protein occludin through Rac1-dependent phosphorylation, and activation of this mechanism was determined to be independent of the bile acid receptors farnesoid X receptor (FXR) and TGR5. Agents that reduce bile acid levels, such as cholestyramine, have helped alleviate HE symptoms in these studies[41-43].

Elevated bile acid levels have also been linked to blood-brain barrier disruption and worsened neurological function in models of acute liver failure. Interventions aimed at lowering serum bile acids, either through diet or pharmacological inhibition of receptors like FXR have delayed cognitive decline in these settings. In murine models of acute liver failure, treatment with bile acid sequestrants such as cholestyramine has been shown to reduce bile acid concentrations in both serum and brain, mitigate cerebral edema, and delay neurological deterioration. Central administration of FXR antago

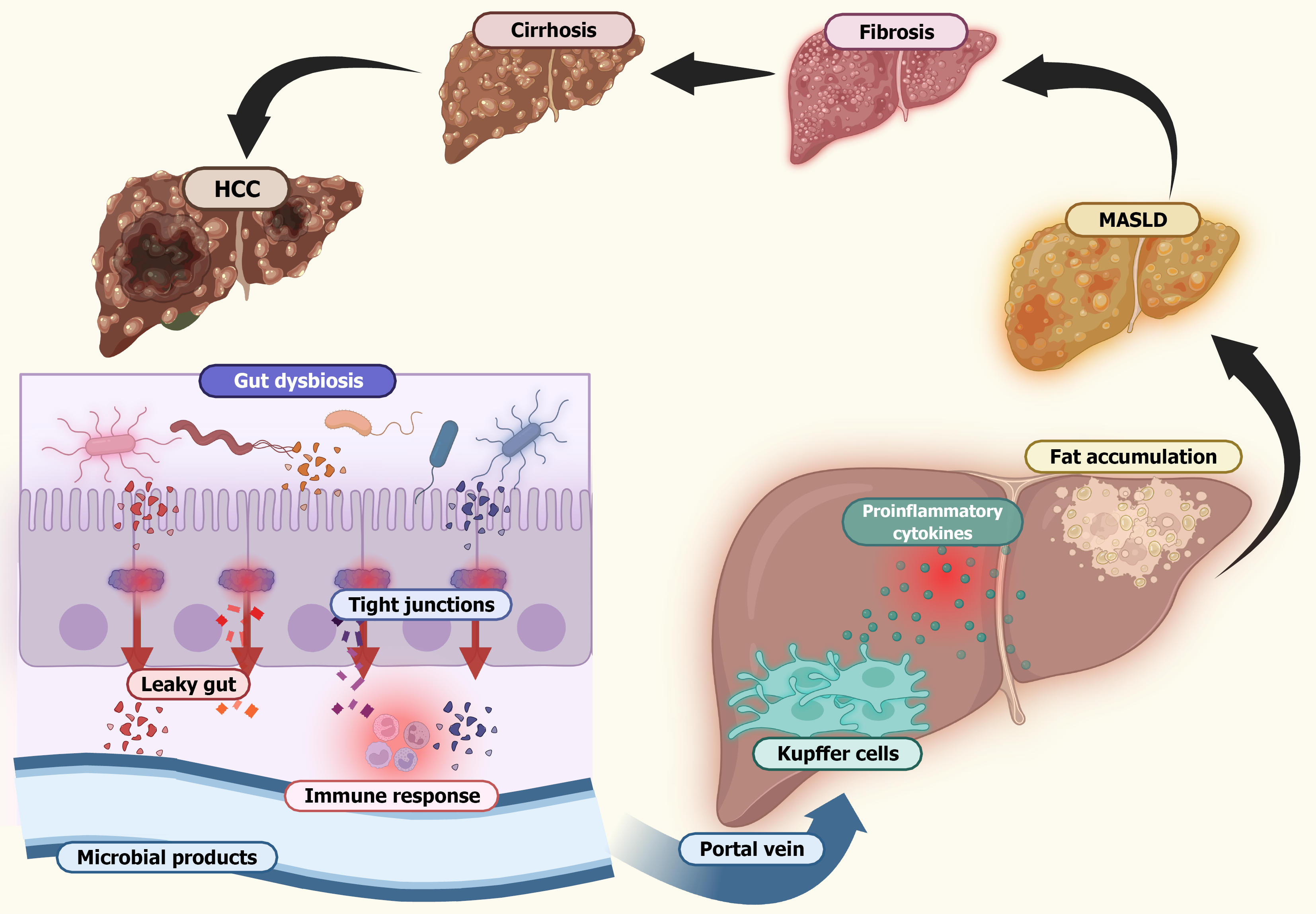

MASLD has gained significant attention due to its strong connection with gut dysbiosis, an imbalance in the composition of the intestinal microbiota. The gut-liver axis serves as a critical pathway in the development of MASLD in which dis

One of the key mechanisms linking gut dysbiosis to liver pathology is the disruption of intestinal barrier integrity, often resulting in increased permeability or leaky gut. This condition allows microbial components, such as LPS, to trans

Moreover, gut microbiota influences liver function through the production of various metabolites, including SCFAs, bile acids, and ethanol. Disruptions in SCFA production and bile acid metabolism have been implicated in MASLD progression and the development of fibrosis. In a dysbiotic state the gut microbiota generates lower levels of protective metabolites, including the SCFA, acetate, and tryptophan derivatives like indole-3-propionic acid and indole-3-acetic acid, which are essential for maintaining gut barrier integrity under healthy conditions. In contrast, microbial and fungal fermentation produces ethanol, leading to inflammation, fibrosis, and cell death. Individuals with MASLD exhibit enhanced microbial conversion of primary bile acids into unconjugated secondary bile acids in the intestine, compounds that are toxic to the liver and lead to disease progression. In addition, this dysregulation may stimulate hepatocytes to increase bile acid synthesis, further exacerbating liver injury[48].

Certain bacterial species, such as Ruminococcus gnavus (R. gnavus), have been linked to liver fat accumulation and inflammatory responses. Nevertheless, the precise mechanisms underlying this relationship and the direction of causality remain uncertain. In experimental studies male mice fed a high-fat diet for 16 weeks or orally colonized with R. gnavus exhibited elevated serum markers associated with fatty liver disease, such as increased levels of low-density lipoprotein, total cholesterol, and liver triglycerides, compared with control mice on a standard diet. Notably, levels of hepatic fibro

The immune system also plays a pivotal role in gut-liver interplay. Microbial products are recognized by TLRs on liver cells, initiating immune responses that can lead to chronic hepatic inflammation and progression to steatohepatitis. The widely accepted multiple hit hypothesis suggests that MASLD arises from a combination of factors, including insulin re

Alcoholic liver disease (ALD) constitutes a spectrum of liver pathologies resulting from chronic and excessive alcohol consumption. Although its precise pathogenesis remains incompletely understood, emerging evidence highlights in

Under physiological conditions enterocytes within the intestinal epithelium form tight junctions that serve as a barrier, limiting the transit of microorganisms and their products from the intestinal lumen to the systemic circulation. In ALD this barrier function is disrupted by the accumulation of ethanol and its metabolite acetaldehyde, which activate TLR4 and protein kinase C in intestinal epithelial cells. This activation leads to the phosphorylation of tight junction proteins, thereby increasing intestinal permeability. Consequently, bacterial translocation into the portal circulation is facilitated, initiating a systemic inflammatory response[52].

TLRs, part of pattern recognition receptors, are expressed in various hepatic and immune cells, including hepatocytes, cholangiocytes, hepatic stellate cells, and systemic immune-competent cells. These receptors recognize conserved microbial structures such as LPS, lipoteichoic acid, lipoarabinomannan, and bacterial DNA. Upon activation TLRs trigger the production of proinflammatory cytokines, contributing to the development of chronic inflammatory microenviron

The translocation of bacteria and their toxic products through the portal circulation activates hepatic immune cells, par

Finally, excessive alcohol consumption induces gut dysbiosis, characterized by a reduction in beneficial commensal bacteria, such as certain Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, and Lactobacillus species and an overgrowth of potentially pathogenic taxa, including Enterobacteriaceae and members of the Proteobacteria phylum. This shift promotes the expansion of both aerobic and anaerobic bacteria while decreasing the production of key microbial metabolites, such as SCFAs and indole derivatives. The loss of these metabolites impairs intestinal barrier function and fosters a chronic systemic inflammatory state, contributing to the progression of ALD[54].

Liver cirrhosis significantly disrupts the intestinal microbiota through multiple mechanisms. First, it reduces the synthesis of bile acids, which plays a crucial role in maintaining microbial balance and gut function. Second, cirrhosis leads to portal hypertension and gastrointestinal blood stasis, impairing the integrity of the intestinal barrier and promoting gut dysbiosis. As the barrier weakens, bacteria and their metabolites can translocate into the portal and systemic circulation, triggering systemic inflammation and endotoxemia. These processes not only accelerate the progression of cirrhosis but also contribute to a range of cirrhosis-related complications (Figure 4)[55,56].

Evidence of increased systemic endotoxemia in patients with liver cirrhosis has been demonstrated using the Limulus amebocyte lysate test. Subsequent quantitative assays further confirmed that plasma endotoxin levels rise progressively with liver fibrosis and the development of cirrhosis. Studies examining portal blood flow in patients with cirrhosis sup

Cirrhosis-associated immune dysfunction further complicates this scenario. Characterized by both systemic inflammation and an impaired immune defense, cirrhosis-associated immune dysfunction is exacerbated by the continuous in

Given this intricate gut-liver interplay, therapeutic interventions targeting the gut microbiota have gained attention. Strategies such as antibiotics, probiotics, and FMT aim to restore gut eubiosis, a state of balanced and diverse gut micro

Recent advances in microbiome sequencing technologies, such as 16S ribosomal RNA sequencing and metagenomics, have greatly improved our understanding of the role of the gut microbiota in liver diseases. 16S rRNA sequencing en

These technologies support a move toward personalized medicine in which treatments can be tailored to an indivi

Variations in treatment response to rifaximin and other therapies in HE is closely linked to differences in gut micro

Additionally, the broader microbiome, including bacterial and viral components such as bacteriophages, also impacts disease progression and treatment efficacy. Alterations in the phage-bacterial network have been documented in patients with cirrhosis and HE, and rifaximin has been shown to modulate these interactions. These observations suggest that microbiota-based profiling could be instrumental in predicting treatment outcomes and optimizing therapy choices[64].

For patients who are refractory to standard treatments like rifaximin and lactulose, FMT has emerged as a promising alternative. By restoring gut microbial balance, FMT offers a targeted approach to improving outcomes in HE, particularly for those who do not benefit from conventional therapies[36].

Next-generation probiotics (NGPs) represent a promising advancement in the treatment of liver diseases, offering potential benefits beyond those of conventional probiotics. Unlike traditional formulations, NGPs are carefully selected or bioengineered to target specific disease mechanisms with improved stability and viability. Utilizing tools from synthetic biology and bioinformatics, these probiotics can be tailored to address pathological conditions, including hepatic disorders, thereby enabling more precise therapeutic interventions. Engineered as live biotherapeutic agents, NGPs can be designed to carry out targeted functions such as suppressing pathogenic microbes or modulating immune activity, both of which are relevant to maintaining liver health. Despite their potential, the clinical application of NGPs remains under investigation, and further research is essential to refine their efficacy and establish safety profiles for broader therapeutic use[65].

The considerable interindividual variability in gut microbiota composition poses a major obstacle to the development of standardized therapeutic strategies, particularly in the context of NGPs for liver disease. This heterogeneity is shaped by a range of factors, such as host genetics, dietary habits, and environmental exposures, leading to highly personalized microbial profiles. As a result the efficacy of probiotic interventions can differ markedly between individuals, depending on their baseline microbiota and its metabolic capacity, making it challenging to identify universally effective strains or formulations[66,67]. In addition, the influence of the gut microbiome on drug metabolism and host physiological responses further complicates the standardization of microbiota-based therapies. Given the central role of the liver in pharmacokinetics, variations in microbial communities may significantly impact drug bioavailability and efficacy in patients with liver disorders. These complexities highlight the need for personalized or stratified treatment approaches that consider individual microbiome characteristics to improve clinical outcomes[68].

To address these challenges strategies such as pooled microbiome therapeutics have emerged in which microbiota from multiple donors are combined to create a more stable and functionally diverse therapeutic product. Preclinical studies have demonstrated that this approach can enhance efficacy and reduce variability in treatment responses. None

Emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence and systems biology are reshaping the future of microbiota-based therapies in liver disease. These innovations offer powerful tools for improving predictive modeling and designing more precise interventions, including FMT and engineered probiotics. Artificial intelligence and machine learning can integrate and analyze complex multi-omics datasets, such as metagenomics, metabolomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics, to uncover the intricate relationships between gut microbes and host physiology. This enables the identification of microbial biomarkers associated with disease progression and therapeutic responsiveness, supporting the development of personalized treatment strategies[70].

In parallel, systems and synthetic biology approaches allow for the rational design of microbial communities with therapeutic potential. For example, technologies like CRISPR/Cas9 and metabolic engineering are being leveraged to construct next-generation probiotics with specific functions, such as producing anti-inflammatory metabolites or restoring metabolic balance in the gut-liver axis. The integration of artificial intelligence with genome-scale metabolic models further enhances this process by predicting microbial behavior and interactions within host environments, in

Together, these technological innovations provide a powerful framework for advancing microbiota-based therapies. By enabling the development of personalized, functionally targeted interventions, they hold promises for improving clinical outcomes in liver diseases characterized by gut dysbiosis and immune dysregulation[71-73].

The gut microbiota has emerged as a central player in the pathophysiology of liver diseases through its influence on ammonia production, systemic inflammation, and neurocognitive dysfunction. This complex gut-liver-brain axis high

| 1. | Lee JY, Tsolis RM, Bäumler AJ. The microbiome and gut homeostasis. Science. 2022;377:eabp9960. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 272] [Article Influence: 68.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Vidal-Gallardo A, Méndez Benítez JE, Flores Rios L, Ochoa Meza LF, Mata Pérez RA, Martínez Romero E, Vargas Beltran AM, Beltran Hernandez JL, Banegas D, Perez B, Martinez Ramirez M. The Role of Gut Microbiome in the Pathogenesis and the Treatment of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Cureus. 2024;16:e54569. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Tilg H, Adolph TE, Trauner M. Gut-liver axis: Pathophysiological concepts and clinical implications. Cell Metab. 2022;34:1700-1718. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 465] [Article Influence: 116.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Wang J, Wang X, Zhuo E, Chen B, Chan S. Gutliver axis in liver disease: From basic science to clinical treatment (Review). Mol Med Rep. 2025;31:10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Zhu R, Liu L, Zhang G, Dong J, Ren Z, Li Z. The pathogenesis of gut microbiota in hepatic encephalopathy by the gut-liver-brain axis. Biosci Rep. 2023;43:BSR20222524. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Hsu CL, Schnabl B. The gut-liver axis and gut microbiota in health and liver disease. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2023;21:719-733. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 407] [Cited by in RCA: 393] [Article Influence: 131.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | He X, Hu M, Xu Y, Xia F, Tan Y, Wang Y, Xiang H, Wu H, Ji T, Xu Q, Wang L, Huang Z, Sun M, Wan Y, Cui P, Liang S, Pan Y, Xiao S, He Y, Song R, Yan J, Quan X, Wei Y, Hong C, Liao W, Li F, El-Omar E, Chen J, Qi X, Gao J, Zhou H. The gut-brain axis underlying hepatic encephalopathy in liver cirrhosis. Nat Med. 2025;31:627-638. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 33.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Mancini A, Campagna F, Amodio P, Tuohy KM. Gut : liver : brain axis: the microbial challenge in the hepatic encephalopathy. Food Funct. 2018;9:1373-1388. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Luo M, Xin RJ, Hu FR, Yao L, Hu SJ, Bai FH. Role of gut microbiota in the pathogenesis and therapeutics of minimal hepatic encephalopathy via the gut-liver-brain axis. World J Gastroenterol. 2023;29:144-156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 10. | American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases; European Association for the Study of the Liver. Hepatic encephalopathy in chronic liver disease: 2014 practice guideline by the European Association for the Study of the Liver and the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. J Hepatol. 2014;61:642-659. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 369] [Cited by in RCA: 354] [Article Influence: 29.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Gluud LL, Vilstrup H, Morgan MY. Non-absorbable disaccharides versus placebo/no intervention and lactulose versus lactitol for the prevention and treatment of hepatic encephalopathy in people with cirrhosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2016:CD003044. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Odenwald MA, Lin H, Lehmann C, Dylla NP, Cole CG, Mostad JD, Pappas TE, Ramaswamy R, Moran A, Hutchison AL, Stutz MR, Dela Cruz M, Adler E, Boissiere J, Khalid M, Cantoral J, Haro F, Oliveira RA, Waligurski E, Cotter TG, Light SH, Beavis KG, Sundararajan A, Sidebottom AM, Reddy KG, Paul S, Pillai A, Te HS, Rinella ME, Charlton MR, Pamer EG, Aronsohn AI. Bifidobacteria metabolize lactulose to optimize gut metabolites and prevent systemic infection in patients with liver disease. Nat Microbiol. 2023;8:2033-2049. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 15.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Patel VC, Lee S, McPhail MJW, Da Silva K, Guilly S, Zamalloa A, Witherden E, Støy S, Manakkat Vijay GK, Pons N, Galleron N, Huang X, Gencer S, Coen M, Tranah TH, Wendon JA, Bruce KD, Le Chatelier E, Ehrlich SD, Edwards LA, Shoaie S, Shawcross DL. Rifaximin-α reduces gut-derived inflammation and mucin degradation in cirrhosis and encephalopathy: RIFSYS randomised controlled trial. J Hepatol. 2022;76:332-342. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 154] [Article Influence: 38.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Cordova-Gallardo J, Vargas-Beltran AM, Armendariz-Pineda SM, Ruiz-Manriquez J, Ampuero J, Torre A. Brain reserve in hepatic encephalopathy: Pathways of damage and preventive strategies through lifestyle and therapeutic interventions. Ann Hepatol. 2025;30:101740. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Yu X, Jin Y, Zhou W, Xiao T, Wu Z, Su J, Gao H, Shen P, Zheng B, Luo Q, Li L, Xiao Y. Rifaximin Modulates the Gut Microbiota to Prevent Hepatic Encephalopathy in Liver Cirrhosis Without Impacting the Resistome. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2021;11:761192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 16. | Bajaj JS, Heuman DM, Sanyal AJ, Hylemon PB, Sterling RK, Stravitz RT, Fuchs M, Ridlon JM, Daita K, Monteith P, Noble NA, White MB, Fisher A, Sikaroodi M, Rangwala H, Gillevet PM. Modulation of the metabiome by rifaximin in patients with cirrhosis and minimal hepatic encephalopathy. PLoS One. 2013;8:e60042. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 254] [Cited by in RCA: 348] [Article Influence: 26.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | DuPont HL. The potential for development of clinically relevant microbial resistance to rifaximin-α: a narrative review. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2023;36:e0003923. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Huang L, Yu Q, Peng H, Zhen Z. Alterations of gut microbiome and effects of probiotic therapy in patients with liver cirrhosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2022;101:e32335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Zhou YL, Pu ST, Xiao JB, Luo J, Xue L. Meta-analysis of probiotics efficacy in the treatment of minimum hepatic encephalopathy. Liver Int. 2024;44:3164-3173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Wang MW, Ma WJ, Wang Y, Ma XH, Xue YF, Guan J, Chen X. Comparison of the effects of probiotics, rifaximin, and lactulose in the treatment of minimal hepatic encephalopathy and gut microbiota. Front Microbiol. 2023;14:1091167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Viramontes Hörner D, Avery A, Stow R. The Effects of Probiotics and Symbiotics on Risk Factors for Hepatic Encephalopathy: A Systematic Review. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2017;51:312-323. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kaufmann B, Seyfried N, Hartmann D, Hartmann P. Probiotics, prebiotics, and synbiotics in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and alcohol-associated liver disease. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2023;325:G42-G61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Chiu WC, Huang YL, Chen YL, Peng HC, Liao WH, Chuang HL, Chen JR, Yang SC. Synbiotics reduce ethanol-induced hepatic steatosis and inflammation by improving intestinal permeability and microbiota in rats. Food Funct. 2015;6:1692-1700. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Malaguarnera M, Greco F, Barone G, Gargante MP, Malaguarnera M, Toscano MA. Bifidobacterium longum with fructo-oligosaccharide (FOS) treatment in minimal hepatic encephalopathy: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:3259-3265. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 142] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Liu Q, Duan ZP, Ha DK, Bengmark S, Kurtovic J, Riordan SM. Synbiotic modulation of gut flora: effect on minimal hepatic encephalopathy in patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2004;39:1441-1449. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 444] [Cited by in RCA: 465] [Article Influence: 21.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Shukla S, Shukla A, Mehboob S, Guha S. Meta-analysis: the effects of gut flora modulation using prebiotics, probiotics and synbiotics on minimal hepatic encephalopathy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:662-671. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 153] [Cited by in RCA: 139] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Parthasarathy G, Malhi H, Bajaj JS. Therapeutic manipulation of the microbiome in liver disease. Hepatology. 2024. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Fang H, Rodrigues E-Lacerda R, Barra NG, Kukje Zada D, Robin N, Mehra A, Schertzer JD. Postbiotic Impact on Host Metabolism and Immunity Provides Therapeutic Potential in Metabolic Disease. Endocr Rev. 2025;46:60-79. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 27.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Bingöl FG, Ağagündüz D, Budán F. Probiotic Bacterium-Derived p40, p75, and HM0539 Proteins as Novel Postbiotics and Gut-Associated Immune System (GAIS) Modulation: Postbiotic-Gut-Health Axis. Microorganisms. 2024;13:23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Zhao X, Liu S, Li S, Jiang W, Wang J, Xiao J, Chen T, Ma J, Khan MZ, Wang W, Li M, Li S, Cao Z. Unlocking the power of postbiotics: A revolutionary approach to nutrition for humans and animals. Cell Metab. 2024;36:725-744. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Żółkiewicz J, Marzec A, Ruszczyński M, Feleszko W. Postbiotics-A Step Beyond Pre- and Probiotics. Nutrients. 2020;12:2189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 331] [Cited by in RCA: 448] [Article Influence: 74.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Zhang J, Duan X, Chen X, Qian S, Ma J, Jiang Z, Hou J. Lactobacillus rhamnosus 1.0320 Postbiotics Ameliorate Dextran Sodium Sulfate-Induced Colonic Inflammation and Oxidative Stress by Regulating the Intestinal Barrier and Gut Microbiota. J Agric Food Chem. 2024;72:25078-25093. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Yilmaz Y. Postbiotics as Antiinflammatory and Immune-Modulating Bioactive Compounds in Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2024;68:e2400754. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Bloom PP, Tapper EB, Young VB, Lok AS. Microbiome therapeutics for hepatic encephalopathy. J Hepatol. 2021;75:1452-1464. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Bajaj JS, Fagan A, Gavis EA, Sterling RK, Gallagher ML, Lee H, Matherly SC, Siddiqui MS, Bartels A, Mousel T, Davis BC, Puri P, Fuchs M, Moutsoglou DM, Thacker LR, Sikaroodi M, Gillevet PM, Khoruts A. Microbiota transplant for hepatic encephalopathy in cirrhosis: The THEMATIC trial. J Hepatol. 2025;83:81-91. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 21.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Bajaj JS, Salzman NH, Acharya C, Sterling RK, White MB, Gavis EA, Fagan A, Hayward M, Holtz ML, Matherly S, Lee H, Osman M, Siddiqui MS, Fuchs M, Puri P, Sikaroodi M, Gillevet PM. Fecal Microbial Transplant Capsules Are Safe in Hepatic Encephalopathy: A Phase 1, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Hepatology. 2019;70:1690-1703. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 237] [Article Influence: 33.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Madsen M, Kimer N, Bendtsen F, Petersen AM. Fecal microbiota transplantation in hepatic encephalopathy: a systematic review. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2021;56:560-569. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Bajaj JS, Kassam Z, Fagan A, Gavis EA, Liu E, Cox IJ, Kheradman R, Heuman D, Wang J, Gurry T, Williams R, Sikaroodi M, Fuchs M, Alm E, John B, Thacker LR, Riva A, Smith M, Taylor-Robinson SD, Gillevet PM. Fecal microbiota transplant from a rational stool donor improves hepatic encephalopathy: A randomized clinical trial. Hepatology. 2017;66:1727-1738. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 351] [Cited by in RCA: 483] [Article Influence: 53.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Gao J, Nie R, Chang H, Yang W, Ren Q. A meta-analysis of microbiome therapies for hepatic encephalopathy. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;35:927-937. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 40. | Shah YR, Ali H, Tiwari A, Guevara-Lazo D, Nombera-Aznaran N, Pinnam BSM, Gangwani MK, Gopakumar H, Sohail AH, Kanumilli S, Calderon-Martinez E, Krishnamoorthy G, Thakral N, Dahiya DS. Role of fecal microbiota transplant in management of hepatic encephalopathy: Current trends and future directions. World J Hepatol. 2024;16:17-32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Ren C, Cha L, Huang SY, Bai GH, Li JH, Xiong X, Feng YX, Feng DP, Gao L, Li JY. Dysregulation of bile acid signal transduction causes neurological dysfunction in cirrhosis rats. World J Hepatol. 2025;17:101340. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | McMillin M, Frampton G, Quinn M, Ashfaq S, de los Santos M 3rd, Grant S, DeMorrow S. Bile Acid Signaling Is Involved in the Neurological Decline in a Murine Model of Acute Liver Failure. Am J Pathol. 2016;186:312-323. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Williams E, Chu C, DeMorrow S. A critical review of bile acids and their receptors in hepatic encephalopathy. Anal Biochem. 2022;643:114436. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | DeMorrow S. Bile Acids in Hepatic Encephalopathy. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2019;9:117-124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Pasta A, Formisano E, Calabrese F, Marabotto E, Furnari M, Bodini G, Torres MCP, Pisciotta L, Giannini EG, Zentilin P. From Dysbiosis to Hepatic Inflammation: A Narrative Review on the Diet-Microbiota-Liver Axis in Steatotic Liver Disease. Microorganisms. 2025;13:241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Kobayashi T, Iwaki M, Nakajima A, Nogami A, Yoneda M. Current Research on the Pathogenesis of NAFLD/NASH and the Gut-Liver Axis: Gut Microbiota, Dysbiosis, and Leaky-Gut Syndrome. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:11689. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Benedé-Ubieto R, Cubero FJ, Nevzorova YA. Breaking the barriers: the role of gut homeostasis in Metabolic-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD). Gut Microbes. 2024;16:2331460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 62.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Schnabl B, Damman CJ, Carr RM. Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease and the gut microbiome: pathogenic insights and therapeutic innovations. J Clin Invest. 2025;135:e186423. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Zhang X, Zhao A, Sandhu AK, Edirisinghe I, Burton-Freeman BM. Red Raspberry and Fructo-Oligosaccharide Supplementation, Metabolic Biomarkers, and the Gut Microbiota in Adults with Prediabetes: A Randomized Crossover Clinical Trial. J Nutr. 2022;152:1438-1449. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Meadows V, Antonio JM, Ferraris RP, Gao N. Ruminococcus gnavus in the gut: driver, contributor, or innocent bystander in steatotic liver disease? FEBS J. 2025;292:1252-1264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Cheng Z, Yang L, Chu H. The role of gut microbiota, exosomes, and their interaction in the pathogenesis of ALD. J Adv Res. 2025;72:353-367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 17.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Eom JA, Jeong JJ, Han SH, Kwon GH, Lee KJ, Gupta H, Sharma SP, Won SM, Oh KK, Yoon SJ, Joung HC, Kim KH, Kim DJ, Suk KT. Gut-microbiota prompt activation of natural killer cell on alcoholic liver disease. Gut Microbes. 2023;15:2281014. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Zhang D, Liu Z, Bai F. Roles of Gut Microbiota in Alcoholic Liver Disease. Int J Gen Med. 2023;16:3735-3746. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Albillos A, de Gottardi A, Rescigno M. The gut-liver axis in liver disease: Pathophysiological basis for therapy. J Hepatol. 2020;72:558-577. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 542] [Cited by in RCA: 1467] [Article Influence: 244.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 55. | Nishimura N, Kaji K, Kitagawa K, Sawada Y, Furukawa M, Ozutsumi T, Fujinaga Y, Tsuji Y, Takaya H, Kawaratani H, Moriya K, Namisaki T, Akahane T, Fukui H, Yoshiji H. Intestinal Permeability Is a Mechanical Rheostat in the Pathogenesis of Liver Cirrhosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:6921. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 56. | Nie G, Zhang H, Xie D, Yan J, Li X. Liver cirrhosis and complications from the perspective of dysbiosis. Front Med (Lausanne). 2023;10:1320015. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Guan H, Zhang X, Kuang M, Yu J. The gut-liver axis in immune remodeling of hepatic cirrhosis. Front Immunol. 2022;13:946628. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Tranah TH, Edwards LA, Schnabl B, Shawcross DL. Targeting the gut-liver-immune axis to treat cirrhosis. Gut. 2021;70:982-994. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 26.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Solé C, Guilly S, Da Silva K, Llopis M, Le-Chatelier E, Huelin P, Carol M, Moreira R, Fabrellas N, De Prada G, Napoleone L, Graupera I, Pose E, Juanola A, Borruel N, Berland M, Toapanta D, Casellas F, Guarner F, Doré J, Solà E, Ehrlich SD, Ginès P. Alterations in Gut Microbiome in Cirrhosis as Assessed by Quantitative Metagenomics: Relationship With Acute-on-Chronic Liver Failure and Prognosis. Gastroenterology. 2021;160:206-218.e13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 26.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Chen Y, Guo J, Qian G, Fang D, Shi D, Guo L, Li L. Gut dysbiosis in acute-on-chronic liver failure and its predictive value for mortality. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;30:1429-1437. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 11.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Wu Z, Zhou H, Liu D, Deng F. Alterations in the gut microbiota and the efficacy of adjuvant probiotic therapy in liver cirrhosis. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2023;13:1218552. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Iebba V, Guerrieri F, Di Gregorio V, Levrero M, Gagliardi A, Santangelo F, Sobolev AP, Circi S, Giannelli V, Mannina L, Schippa S, Merli M. Combining amplicon sequencing and metabolomics in cirrhotic patients highlights distinctive microbiota features involved in bacterial translocation, systemic inflammation and hepatic encephalopathy. Sci Rep. 2018;8:8210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Ballester MP, Gallego JJ, Fiorillo A, Casanova-Ferrer F, Giménez-Garzó C, Escudero-García D, Tosca J, Ríos MP, Montón C, Durbán L, Ballester J, Benlloch S, Urios A, San-Miguel T, Kosenko E, Serra MÁ, Felipo V, Montoliu C. Metabolic syndrome is associated with poor response to rifaximin in minimal hepatic encephalopathy. Sci Rep. 2022;12:2463. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Bajaj JS, Sikaroodi M, Shamsaddini A, Henseler Z, Santiago-Rodriguez T, Acharya C, Fagan A, Hylemon PB, Fuchs M, Gavis E, Ward T, Knights D, Gillevet PM. Interaction of bacterial metagenome and virome in patients with cirrhosis and hepatic encephalopathy. Gut. 2021;70:1162-1173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Tiwari A, Ika Krisnawati D, Susilowati E, Mutalik C, Kuo TR. Next-Generation Probiotics and Chronic Diseases: A Review of Current Research and Future Directions. J Agric Food Chem. 2024;72:27679-27700. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Fassarella M, Blaak EE, Penders J, Nauta A, Smidt H, Zoetendal EG. Gut microbiome stability and resilience: elucidating the response to perturbations in order to modulate gut health. Gut. 2021;70:595-605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 438] [Article Influence: 87.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (70)] |

| 67. | Singh TP, Natraj BH. Next-generation probiotics: a promising approach towards designing personalized medicine. Crit Rev Microbiol. 2021;47:479-498. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 15.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Ford D. Interactions between the intestinal microbiota and drug metabolism - Clinical implications and future opportunities. Biochem Pharmacol. 2025;235:116809. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Reygner J, Delannoy J, Barba-Goudiaby M-T, Gasc C, Levast B, Gaschet E, Ferraris L, Paul S, Kapel N, Waligora-Dupriet A-J, Barbut F, Thomas M, Schwintner C, Laperrousaz B, Corvaïa N. Reduction of product composition variability using pooled microbiome ecosystem therapy and consequence in two infectious murine models. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2024;90:e0001624. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Rozera T, Pasolli E, Segata N, Ianiro G. Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence in the Multi-Omics Approach to Gut Microbiota. Gastroenterology. 2025;169:487-501. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 29.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Nazir A, Hussain FHN, Raza A. Advancing microbiota therapeutics: the role of synthetic biology in engineering microbial communities for precision medicine. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2024;12:1511149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Kumar P, Sinha R, Shukla P. Artificial intelligence and synthetic biology approaches for human gut microbiome. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2022;62:2103-2121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Li L, Nielsen J, Chen Y. Personalized gut microbial community modeling by leveraging genome-scale metabolic models and metagenomics. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2025;91:103248. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/