Published online Dec 5, 2025. doi: 10.4292/wjgpt.v16.i4.110273

Revised: July 1, 2025

Accepted: September 5, 2025

Published online: December 5, 2025

Processing time: 185 Days and 16.1 Hours

Crohn’s disease (CD) is a chronic immune-mediated inflammatory condition with significant morbidity. Several advanced therapies are now licenced for its treat

To assess if in those with uncontrolled disease on ustekinumab, switching to ri

A retrospective review of electronic health records was conducted for adult CD patients at a tertiary center who switched directly from ustekinumab to risankizu

Fifty-one patients with a mean disease duration of 12.7 years were included. HBI decreased significantly at all timepoints (P < 0.001), with clinical remission rates increasing from 37.1% at baseline to 94.4% at 9 months. Albumin increased significantly, while CRP and calprotectin showed numerical improvements without statistical significance. Superior responses were seen in patients with secondary loss of response (SLOR) to ustekinumab compared to primary non-response. No serious adverse events occurred.

Switching from ustekinumab to risankizumab in active CD led to significant clinical and biochemical impro

Core Tip: Despite evidence of superiority of risankizumab over ustekinumab when managing Crohn’s disease, it is unknown if switching from ustekinumab to risankizumab is effective. This retrospective study evaluated outcomes in 51 adults who switched from ustekinumab to risankizumab. Significant reductions in Harvey-Bradshaw Index scores were observed at all timepoints, with remission rates rising from 37.1% to 94.4% over 9 months. Albumin, C-reactive protein and calprotectin also improved. Patients with secondary loss of response to ustekinumab responded better than primary non-responders. No serious adverse events occurred. These findings support risankizumab as a safe, effective option after ustekinumab failure in refractory Crohn’s.

- Citation: Colwill M, Padley J, Qazi U, Mehta S, Donovan F, Alves AM, Pollok R, Patel K, Dawson P, Honap S, Poullis A. Risankizumab is effective following ustekinumab failure in Crohn’s disease: A real-world study from a tertiary center. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther 2025; 16(4): 110273

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2150-5349/full/v16/i4/110273.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4292/wjgpt.v16.i4.110273

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), predominantly incorporating Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), is a chronic inflammatory gastrointestinal condition that causes symptoms of abdominal pain, diarrhoea, bloody stools and weight loss[1]. CD, which is less common than UC, affects the entire gastrointestinal tract in a discontinuous pattern and is characterised by transmural inflammation which can lead to stricturing and penetrating complications such as fistulae, abscesses and perforations[1,2]. CD is associated with high levels of morbidity and long-term complications such as short-bowel syndrome, recurrent surgery and colorectal cancer. A significant proportion of patients with CD also fail to respond, or lose response, to advanced therapies and defined as suffering from refractory CD. These patients have higher morbidity, mortality and healthcare costs and often require multiple medical therapies to obtain disease control and the management of refractory CD poses a challenge to physicians[3,4].

Our understanding of the complex immunopathology and interplay between a genetically primed host and environmental factors that leads to the development of CD has increased significantly in recent years. This has led to a dramatic expansion in the medical armamentarium used to treat CD which now includes monoclonal antibodies that target tumour necrosis factor a (anti-TNFa), interleukin (IL)-23 and IL-12 and a4b7 integrins as well as small molecule agents, such as Janus Kinase inhibitors[5]. Along with novel therapeutics there has also been a change in the treatment strategies employed to manage CD. Traditionally, a step-up approach has been employed however the landmark PROFILE trial has demonstrated that early advanced therapy (AT), or ‘top-down’ treatment, for moderate to severe disease, is associated with superior steroid-free and surgery-free remission and fewer adverse events[6]. This top-down strategy, along with advanced combination therapy[7] and personalised therapeutic approaches[8], have all been proposed to assist in the treatment of refractory CD.

However, despite these novel therapeutics and strategies, a therapeutic ceiling continues to exist with even the newest therapeutic agents offering remission rates at 1 year of between 40%-50%[7]. There is also the phenomenon of ‘dimi

The SEQUENCE trial attempted to address one of these questions by providing a rare head-to-head randomised control double-blind trial comparing two anti-IL23 treatments in CD. Ustekinumab, a monoclonal antibody that targets the common p40 sub-unit on IL-12 and IL-23, has been licenced for the treatment of CD since 2016 and is widely pre

Whilst this study suggested superiority of risankizumab over ustekinumab, the population studied only included those with previous anti-TNFa treatment. There is evidence suggesting that prior ustekinumab use may negatively impact upon the efficacy of risankizumab[13] and therefore it is unclear whether, in patients who lose response or failed to respond to ustekinumab, switching treatment to risankizumab is still an effective and useful treatment strategy. In real-world practice, given the earlier approval of ustekinumab compared to risankizumab and novel biosimilars which offer significant cost savings to healthcare systems, there are large numbers of patients who are currently treated with ustekinumab. Hence, understanding whether, in patients who then lose response, switching to risankizumab directly from ustekinumab is still effective is a clinically relevant and unanswered question.

We therefore aimed to use real-world data to assess the effectiveness of switching ustekinumab to risankizumab in patients with active CD.

A retrospective AT database review was undertaken at a tertiary IBD centre to identify all adult patients with CD who had treatment switched directly from ustekinumab to risankizumab between the period of December 2023 and September 2024. Patients being treated with ustekinumab for an indication other than CD, participating in a clinical trial or without baseline data to provide disease activity assessment were excluded.

Electronic health records were reviewed to obtain data on patient demographics, disease phenotype, as per the Mon

The primary outcome of the study was disease activity assessed using clinical, biochemical, and endoscopic markers. This was collected at the time of therapy switch (baseline) and at 3,6 and 9 months afterwards. Clinical disease activity was assessed using the Harvey-Bradshaw Index (HBI) as documented during outpatient and infusion suite appointments with a score < 5 being indicative of clinical remission. Biochemical markers included C-reactive protein (CRP), serum albumin and faecal calprotectin (FCP). Endoscopic records were also reviewed to record the documented simple endoscopic score for CD (SES-CD). Values recorded for baseline data were taken from up to 8 weeks prior to therapy switch. All values for data following therapy switch were taken within a 4-week period of each follow-up interval.

The secondary outcome was adverse events within the follow-up period that were related to the drug. This included drug hypersensitivity reactions, any infection requiring hospital admission, bowel resection surgery, new cancer diag

Mean values were calculated to summarize continuous variables. Patient data points were included in our analysis up to the most recent clinical review even if previous follow-up data points were missing. Statistical significance was assessed using a linear mixed-effects model, to allow inclusion of patients with missing data points, and a generalized estimating equations model with a logistic link was used to assess changes in clinical remission (defined as HBI < 5) over time, ac

54 patients were identified as having switched from ustekinumab to risankizumab therapy, 3 were excluded from analysis as they were seen as part of a clinical trial. 51 patients were included in the study and their baseline demographic details are summarised in Table 1. The mean age at time of treatment switch was 45 years with an age range of 19-82 years and median disease duration 12.7 years. At the time of data collection in April 2025, 40 of 51 patients had been on treatment for 9 months or more. The median duration of follow-up was 333 days.

| Characteristics | n (%) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 27 (52.9) |

| Female | 24 (47.1) |

| Montreal disease classification | |

| Age at diagnosis | |

| A1 | 7 (13.7) |

| A2 | 25 (49) |

| A3 | 19 (37.3) |

| Location | |

| L1-ileal | 19 (37.3) |

| L2-colonic | 10 (19.6) |

| L3-ileocolonic | 21 (41.2) |

| L4-isolated upper gi disease | 1 (1.9) |

| Behaviour | |

| B1-non-stricturing | 22 (43.1) |

| B2-stricturing | 18 (35.3) |

| B2/3-stricturing and penetrating | 5 (9.8) |

| B3-penetrating | 6 (11.7) |

| Perianal disease | 7 (13.7) |

| Number of previous advanced therapies | |

| 1 | 7 (13.7) |

| 2 | 32 (62.8) |

| 3 | 9 (17.6) |

| 4 | 3 (5.9) |

9 patients were switched due to primary non-response (PNR) to ustekinumab, 41 due to secondary loss of response (SLOR) and 1 due to side effects (rash). All 51 patients remained on risankizumab at the end of our data collection.

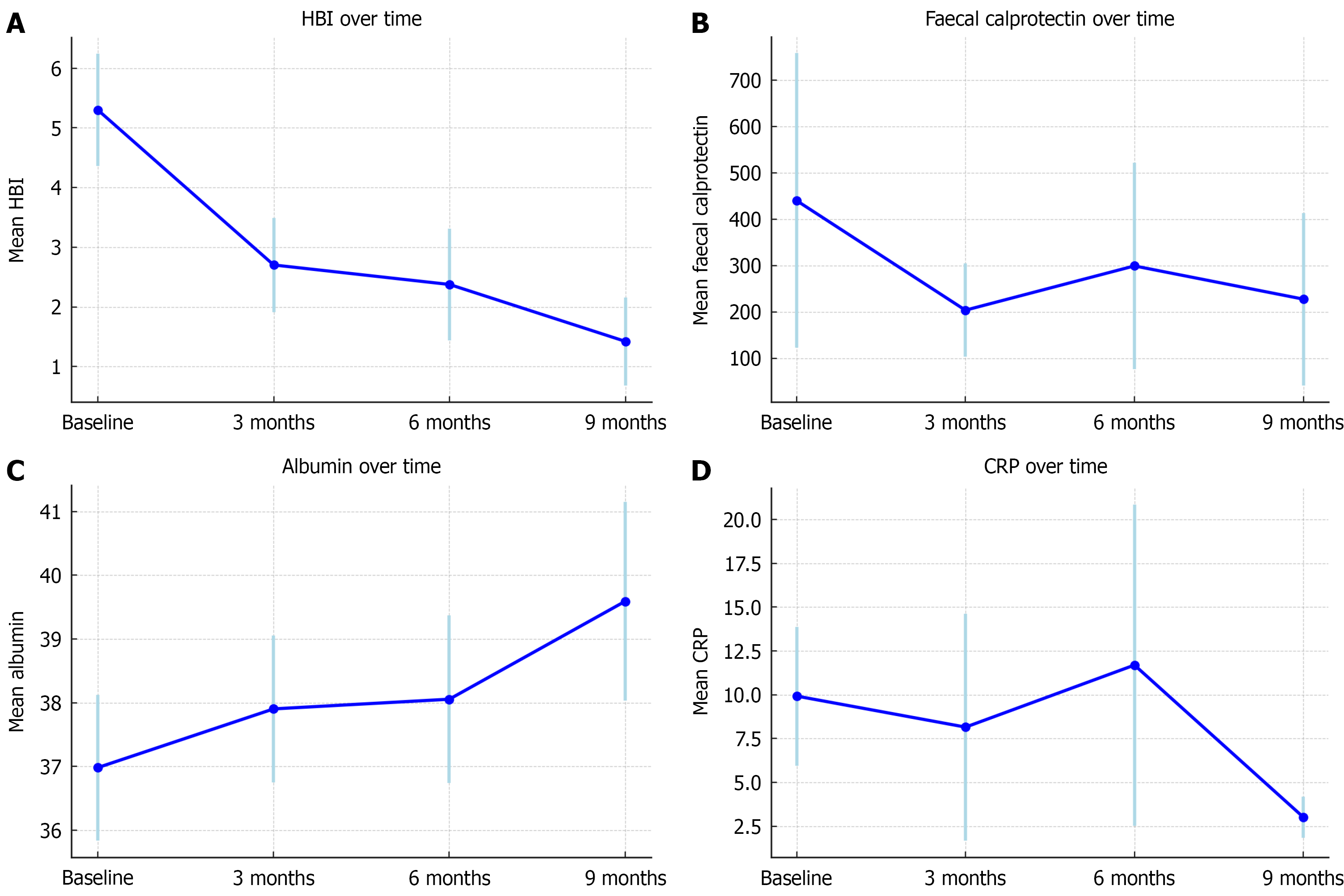

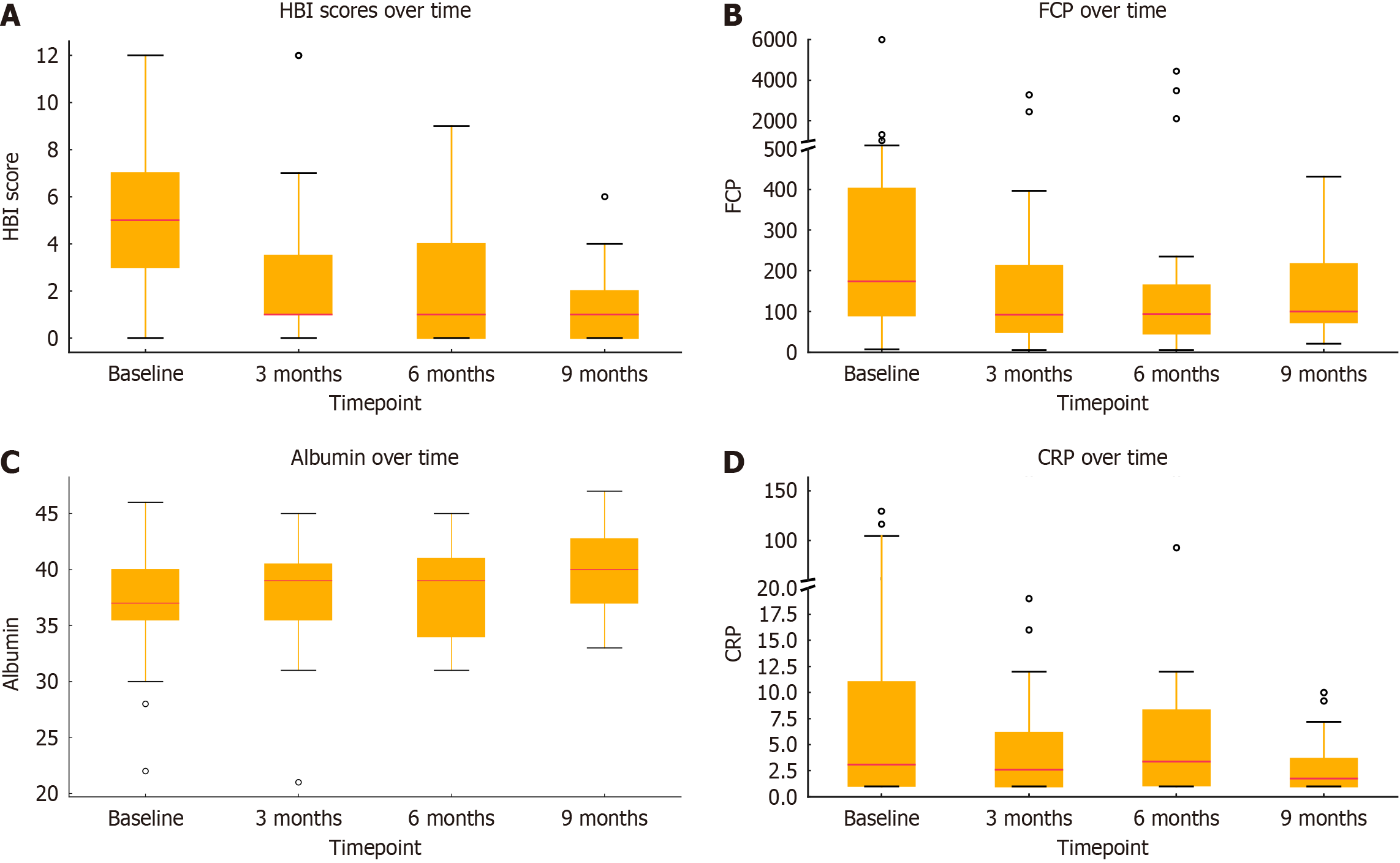

All 51 patients had clinical (HBI), biochemical FCP or serum CRP, or endoscopic evidence (SES-CD) of active disease at baseline. The results at baseline found a mean HBI of 5.3, mean FCP of 525 mg/g, mean serum CRP of 9.7 mg/L and mean serum albumin of 36.9 g/L. The changes in these clinical markers over time are summarised in Tables 2 and 3 and Figures 1 and 2.

| Marker | 3 months | 6 months | 9 months | |||||||||

| n | Mean change | 95%CI | P value | n | Mean change | 95%CI | P value | n | Mean change | 95%CI | P value | |

| Albumin (g/L) | 51 | +0.92 | 0.04-1.81 | 0.042 | 37 | +1.13 | 0.13-2.12 | 0.026 | 22 | +2.13 | 0.92-3.34 | < 0.001 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 51 | -1.75 | -9.06-5.56 | 0.639 | 37 | +1.5 | -6.52-9.52 | 0.714 | 22 | -6.85 | -16.46-2.76 | 0.163 |

| FCP (μg/g) | 33 | -253.3 | -541.48-34.95 | 0.085 | 22 | -141.3 | -468.65-186.08 | 0.398 | 12 | -193.5 | -601.82-214.86 | 0.353 |

| HBI | 48 | -2.5 | -3.32 to -1.76 | < 0.001 | 32 | -3.0 | -3.87 to -2.08 | < 0.001 | 19 | -4.36 | -5.51 to -3.20 | < 0.001 |

| Baseline | 3 months | 6 months | 9 months | |

| Remission (< 5) | 20 (39.2) | 33 (70.2) | 25 (78.1) | 18 (94.7) |

| Mild disease (5-7) | 14 (27.5) | 9 (19.2) | 6 (18.8) | 1 (5.3) |

| Moderate disease (8-16) | 12 (23.5) | 3 (6.4) | 1 (3.1) | 0 |

| Severe disease (> 16) | 4 (7.8) | 3 (6.4) | 0 | 0 |

The mean HBI at baseline was 5.3 [95% confidence interval (CI): 4.4-6.2; n = 51], this declined to 2.7 at 3 months (95%CI: 1.9-3.5; n = 47), and further to 2.4 at 6 months (95%CI: 0.68-2.16; n = 32) and 1.5 at 9 months (95%CI: 0.68-2.16; n = 18). All reductions

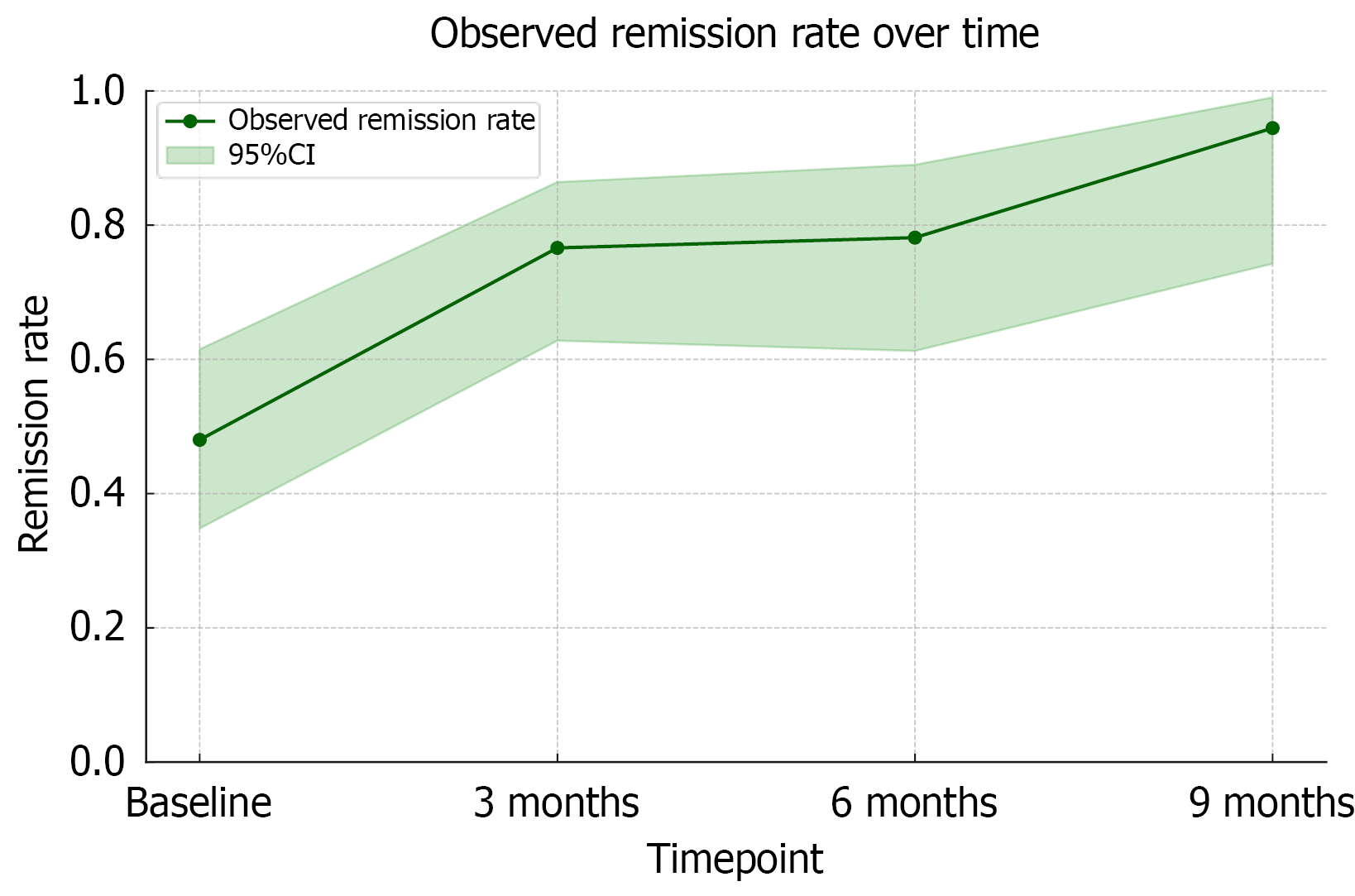

Remission rates assessed using HBI at baseline, 3,6 and 9 months were 39.2% (20/51), 70.2% (33/48), 78.1% (25/32) and 94.4% (18/19) respectively (Table 3). Compared to baseline, the odds of remission increased significantly at each follow-up (Figure 3). The odds ratio of remission at 3, 6 and 9 months were 3.55 (95%CI: 1.85-6.81; P < 0.001), 3.87 (95%CI: 1.28-11.74; P = 0.017) and 18.41 (95%CI: 2.60-130.9; P = 0.004) respectively.

The mean baseline serum albumin level was 37.0 g/L (95%CI: 35.8-38.1). This increased to 37.9 g/L at 3 months (95%CI: 36.8-39.1; n = 51), 38.1 g/L at 6 months (95%CI: 36.7-39.4; n = 37), and 39.6 g/L at 9 months (95%CI: 38.0-41.2; n = 22). The increases in albumin were statistically significant at all timepoints compared to baseline: +0.92 g/L at 3 months (P = 0.042), +1.13 g/L at 6 months (P = 0.026), and +2.13 g/L at 9 months (P = 0.001).

The mean FCP at baseline was 440.9 μg/g (95%CI: 122.7-759.1; n = 51), this decreased at 3 months to a mean of 204.1 μg/g (95%CI: 103.5-304.6; n = 33), at 6 months to 299.6 μg/g (95%CI: 77.2-522.1; n = 22), and at 9 months it was 227.9 μg/g (95%CI: 41.6-414.3; n = 12). None of these results were statistically significant. Substantial inter-patient variability was observed, as reflected by the large random effect variance (94).

Mean baseline CRP was 9.9 mg/L (95%CI: 6.0-13.9), this decreased to 8.2 mg/L at 3 months (95%CI: 1.7-14.6; n = 51), 11.7 mg/L at 6 months (95%CI: 2.5-20.9; n = 37), and 3.0 mg/L at 9 months (95%CI: 1.8-4.2; n = 22). No results were statistically significant. Substantial inter-individual variability in CRP response was observed (random effect variance: 73.9).

A sub-group analysis was performed using a linear mixed effects model only including patients with SLOR (Table 4). This demonstrated a significant increase in mean serum albumin levels at 3, 6 and 9 months from 36.66 g/L at baseline. Mean HBI at baseline was 5.13 (95%CI: 4.31-5.95) and significant improvements were observed at 6 months (-1.09; P = 0.031) and 9 months (-2.62; P < 0.001). FCP declined progressively from a baseline mean of 496 μg/g with the reduction at 9 months approaching statistical significance (P = 0.054). CRP levels showed a numerical reduction over time from a baseline mean of 9.93 mg/L.

| Marker | 3 months | 6 months | 9 months | |||||||||

| n | Mean change | 95%CI | P value | n | Mean change | 95%CI | P value | n | Mean change | 95%CI | P value | |

| Albumin (g/L) | 41 | +1.44 | 36.79-39.13 | 0.004 | 37 | +1.31 | 36.69-39.36 | 0.019 | 22 | +2.08 | 38.00-41.18 | 0.003 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 41 | -5.1 | -12.2-1.99 | 0.158 | 37 | 2.03 | -5.88-9.95 | 0.606 | 22 | -7.56 | -17.1-1.97 | 0.115 |

| FCP (μg/g) | 28 | -291 | -688.5-91.0 | 0.133 | 19 | -291 | -686.9-104.1 | 0.149 | 8 | -376 | -757.3 to -5.7 | 0.054 |

| HBI | 37 | -0.55 | 1.91-3.49 | 0.221 | 32 | -1.09 | 1.44-3.31 | 0.031 | 18 | -2.62 | 0.68-2.16 | < 0.001 |

A further sub-group analysis was performed comparing patients who were switched because of PNR compared to SLOR. At 3 months, the PNR saw a rise in CRP (n = 9, change/delta = +12.9 mg/L) and FCP (n = 3, mean change/delta = +169.0 μg/g), and modest decline in serum albumin (n = 9, change/delta = -1.0 g/L) compared to a decrease in the SLOR cohort in CRP (n = 37, change/delta = -5.6 mg/L; P = 0.0436), FCP (n = 24, change/delta = -392.3 μg/g; P = 0.0212) and an increase in albumin (n = 40, change/delta = +1.5 g/L; P = 0.0162) and all differences between the 2 cohorts were statistically significant. In both cohorts HBI improved but the change was more substantial in the SLOR group (n = 40, change/delta = -0.77) compared to the PNR group (n = 3, change/delta = -0.67). However, at 6 and 9 months there were no significant differences between the two groups in any parameters.

At baseline, 9/51 (17.7%) patients were using partial or exclusive enteral nutrition, this fell to 6/51 (11.8%) patients at 3 months, 4/51 (7.8%) patients at 6 months and 3/40 (7.5%) patients at 9 months. 1 patient received a course of predni

SES-CD scores were available for 3 patients at 6 months of which 1 improved, 1 worsened and 1 was unchanged.

Rates of adverse events were low. 1 patient was admitted at 3 months after initiation of risankizumab with a urinary tract infection requiring intravenous antibiotics and 1 patient was admitted with abdominal pain and vomiting however no evidence of active CD was seen on cross-sectional imaging and the patient was discharged without a change to IBD therapy. No MACE, hypersensitivity reactions, cancers or deaths were reported.

Our real-world study has shown that in patients with CD who have either not responded, or lost response, to ustekinu

Whilst a previous study has suggested that previous ustekinumab exposure may reduce the robustness of response to risankizumab[13], our data suggests that even if this is the case risankizumab remains an effective option for treating CD[14]. The reason for the difference in findings may be due to the heterogeneous nature of the groups that were studied and the fact that refractory CD is a challenging entity with multiple confounders, such as the phenotype or duration of disease, which are difficult to control for. Previous studies have also not focused specifically on patients with active disease or in direct switches from ustekinumab and our study demonstrates that even in a group who have refractory CD and have been already been exposed to multiple AT, risankizumab is still effective in the short term.

Our data also suggests that there may be a difference between those with PNR to ustekinumab compared to SLOR with results at 3 months suggesting a poor response, with an increase in CRP and FCP, for those with PNR compared to improvements seen in the SLOR cohort. Whilst data at 6 and 9 months did not show a significant difference, this may have been due to relatively small numbers and further work with larger cohorts is required. This correlates to previous work by Singh et al[10] which has shown that PNR to anti-TNFa is associated with a poorer response to ustekinumab and may be due a more treatment-resistant phenotype in these patients. Interestingly, in this meta-analysis, there was no difference in outcomes between PNR and SLOR cohorts when switched to vedolizumab, therefore in patients with PNR to ustekinumab switching out of class from IL-23 inhibitors is potentially a more appropriate treatment choice.

A previous real-world analysis found similar clinical remission rates, defined as HBI < 5, to our study at 6 months after treatment initiation - 63% compared to 78.1%- but a lower remission rate at 52 weeks, 54% in their cohort, compared to 94.4% in our cohort at 9 months[13]. We recognise our remission rate is high compared to both this and other studies[15] and is likely due to the small numbers for which HBI data was available at 9 months (n = 18).

The strength of our study is the fact that it uses real-world data to help to answer a clinically pertinent question and help guide physicians when making treatment decisions regarding which AT to utilise after ustekinumab failure. Our study also assessed a combination of clinical and biochemical markers and we were able to assess remission rates using HBI which has been shown to correlate well with CD Activity Index[16]. The limitations of our study are that it is from a single center and so may not be generalisable to other IBD populations and it is observational which introduces both a risk of bias and confounding variables. The number of patients involved was also relatively small and this may have skewed some of the results particularly when examining the later data points and sub-groups such as PNR and SLOR groups. It should also be noted that the last patient was enrolled in December 2024 and therefore some patients who had not reached the 6 or 9 months data collection point which further reduced the numbers available for data analysis. These relatively small numbers may also account for the numerical but not statistically significant findings with regards to CRP and FCP. We did not account for confounders such as the use of corticosteroids or enteral nutrition as adjunctive treatments. However, given the low rates of partial enteral nutrition or exclusive enteral nutrition use at 6 months (7.8%) and 9 months (7.5%) as well as the lack of any corticosteroid use in 3, 6 or 9 months data points we do not feel this will have significantly affected our results.

Future work will involve longer term data collection from multiple centres to provide greater clarity on the use of risankizumab after ustekinumab in the medium-to-long term and inform on the durability of the benefit obtained from treatment with risankizumab. We would also aim to collect more data on endoscopic severity scores.

Our real-world study has demonstrated that in patients with CD who do not respond to, or lose response to, ustekinumab switching to risankizumab is an effective option with improvements seen in clinical and biochemical markers of disease activity. Given the current wide use of ustekinumab, this data can help to inform physicians about the next steps in managing refractory CD.

| 1. | Marshall JK. Are there epidemiological differences between Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis? Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14 Suppl 2:S1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Dolinger M, Torres J, Vermeire S. Crohn's disease. Lancet. 2024;403:1177-1191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 300] [Article Influence: 150.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (104)] |

| 3. | Park KT, Ehrlich OG, Allen JI, Meadows P, Szigethy EM, Henrichsen K, Kim SC, Lawton RC, Murphy SM, Regueiro M, Rubin DT, Engel-Nitz NM, Heller CA. The Cost of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: An Initiative From the Crohn's & Colitis Foundation. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2020;26:1-10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 260] [Cited by in RCA: 344] [Article Influence: 57.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Knowles SR, Graff LA, Wilding H, Hewitt C, Keefer L, Mikocka-Walus A. Quality of Life in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-analyses-Part I. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24:742-751. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 156] [Cited by in RCA: 360] [Article Influence: 45.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Fudman DI, McConnell RA, Ha C, Singh S. Modern Advanced Therapies for Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: Practical Considerations and Positioning. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2025;23:454-468. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 29.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Noor NM, Lee JC, Bond S, Dowling F, Brezina B, Patel KV, Ahmad T, Banim PJ, Berrill JW, Cooney R, De La Revilla Negro J, de Silva S, Din S, Durai D, Gordon JN, Irving PM, Johnson M, Kent AJ, Kok KB, Moran GW, Mowat C, Patel P, Probert CS, Raine T, Saich R, Seward A, Sharpstone D, Smith MA, Subramanian S, Upponi SS, Wiles A, Williams HRT, van den Brink GR, Vermeire S, Jairath V, D'Haens GR, McKinney EF, Lyons PA, Lindsay JO, Kennedy NA, Smith KGC, Parkes M; PROFILE Study Group. A biomarker-stratified comparison of top-down versus accelerated step-up treatment strategies for patients with newly diagnosed Crohn's disease (PROFILE): a multicentre, open-label randomised controlled trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024;9:415-427. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 180] [Article Influence: 90.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Danese S, Solitano V, Jairath V, Peyrin-Biroulet L. The future of drug development for inflammatory bowel disease: the need to ACT (advanced combination treatment). Gut. 2022;71:2380-2387. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 13.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Centanni L, Cicerone C, Fanizzi F, D'Amico F, Furfaro F, Zilli A, Parigi TL, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Danese S, Allocca M. Advancing Therapeutic Targets in IBD: Emerging Goals and Precision Medicine Approaches. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2025;18:78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kumar A, Smith PJ. Horizon scanning: new and future therapies in the management of inflammatory bowel disease. eGastroenterology. 2023;1:e100012. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Singh S, George J, Boland BS, Vande Casteele N, Sandborn WJ. Primary Non-Response to Tumor Necrosis Factor Antagonists is Associated with Inferior Response to Second-line Biologics in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Crohns Colitis. 2018;12:635-643. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 182] [Article Influence: 22.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kapizioni C, Desoki R, Lam D, Balendran K, Al-Sulais E, Subramanian S, Rimmer JE, De La Revilla Negro J, Pavey H, Pele L, Brooks J, Moran GW, Irving PM, Limdi JK, Lamb CA; UK IBD BioResource Investigators, Parkes M, Raine T. Biologic Therapy for Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Real-World Comparative Effectiveness and Impact of Drug Sequencing in 13 222 Patients within the UK IBD BioResource. J Crohns Colitis. 2024;18:790-800. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 34.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Papp KA, Blauvelt A, Bukhalo M, Gooderham M, Krueger JG, Lacour JP, Menter A, Philipp S, Sofen H, Tyring S, Berner BR, Visvanathan S, Pamulapati C, Bennett N, Flack M, Scholl P, Padula SJ. Risankizumab versus Ustekinumab for Moderate-to-Severe Plaque Psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1551-1560. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 339] [Cited by in RCA: 421] [Article Influence: 46.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Risankizumab Effectiveness in Ustekinumab-Naive and Ustekinumab-Experienced Patients With Crohn's Disease: Real-World Data From a Large Tertiary Center. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2024;20:16-17. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Manski S, Andreone M, Swaminathan S, Cordero-baez F, Sanchez JC, Kantor J, Keith S, Shmidt E, Shivashankar R. S1156 A Multi-Center Study of the Outcomes of Risankizumab Use Stratified by Prior Ustekinumab Exposure in Patients With Crohn’s Disease: A Real-World Experience. Am J Gastroenterol. 2024;119:S820-S821. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 15. | Peyrin-Biroulet L, Chapman JC, Colombel JF, Caprioli F, D'Haens G, Ferrante M, Schreiber S, Atreya R, Danese S, Lindsay JO, Bossuyt P, Siegmund B, Irving PM, Panaccione R, Cao Q, Neimark E, Wallace K, Anschutz T, Kligys K, Duan WR, Pivorunas V, Huang X, Berg S, Shu L, Dubinsky M; SEQUENCE Study Group. Risankizumab versus Ustekinumab for Moderate-to-Severe Crohn's Disease. N Engl J Med. 2024;391:213-223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 52.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Vermeire S, Schreiber S, Sandborn WJ, Dubois C, Rutgeerts P. Correlation between the Crohn's disease activity and Harvey-Bradshaw indices in assessing Crohn's disease severity. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:357-363. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 283] [Cited by in RCA: 346] [Article Influence: 21.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/