Published online Dec 22, 2025. doi: 10.4291/wjgp.v16.i4.113488

Revised: September 21, 2025

Accepted: December 2, 2025

Published online: December 22, 2025

Processing time: 117 Days and 17.8 Hours

The gut microbiome is integral to human health, with emerging research under

To evaluate the influence of the gut microbiome on the pathogenesis and pro

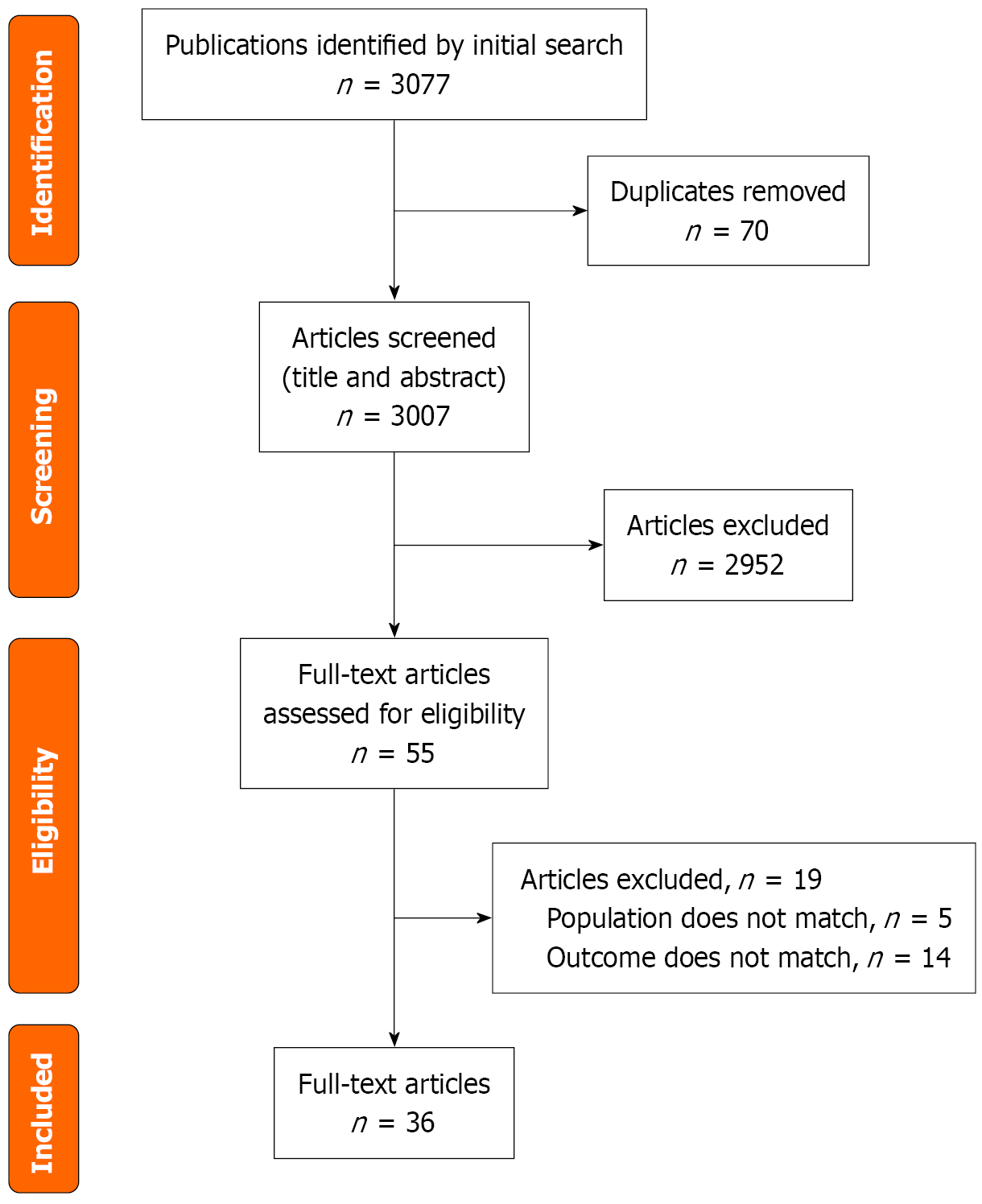

An extensive search of the scientific literature was undertaken by adhering to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews & Meta-Analyses standards, using PubMed (MEDLINE), Scopus, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Library as sources to locate studies addressing the relationship between the gut microbiome and human health. To capture all relevant publications, search terms were systematically applied across these major databases, without limiting the search by language or publication date. Inclusion criteria covered randomized controlled trials, non-randomized controlled trial, prospective studies, cross-sectional studies, and case-control studies. Out of the 3077 articles, 36 full texts were included in the review.

Ocular health appears to be shaped by the gut microbial community through mechanisms such as immune regulation, preservation of the blood–retinal barrier, and the generation of protective metabolites. Disturbances in this microbial balance can provoke measurable alterations in host immunity, providing a plausible immunopathogenic pathway that connects intestinal dysbiosis with eye disease. Both laboratory models and early human data suggest that targeted interventions, including prebiotics, probiotics, synbiotics, and faecal microbiota transfer, hold therapeutic potential.

The gut–eye relationship reflects a multifaceted interaction in which the intestinal microbiome contributes to ocular health through complex biological pathways. Integrating microbiome assessments into diagnostic methods can revolutionize disease management through early detection and targeted interventions. Further, randomised controlled clinical trials are necessary for ocular diseases to prove causal relationships.

Core Tip: The gut microbiome significantly influences ocular health through immune modulation, metabolic interactions, and maintenance of physiological barriers. Dysbiosis is linked to the onset and progression of major eye diseases such as uveitis, macular degeneration, dry eye, and glaucoma. Therapeutic interventions—including prebiotics, probiotics, synbiotics, and fecal microbiota transplantation—show promising results in preclinical and preliminary human studies, although further large-scale clinical trials are warranted to confirm their efficacy and safety in the context of ocular disease management.

- Citation: Priyanka P, Khullar S, Singh M, Morya AK, Sharma B, Periasamy B, Moharana B, Morya R. Role of gut microbiomes in different ocular pathologies: A systematic review. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol 2025; 16(4): 113488

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2150-5330/full/v16/i4/113488.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4291/wjgp.v16.i4.113488

Human health is strongly influenced by the microbiome, a complex network of microbial species that interact symbiotically to maintain normal biological function. It is composed of microbial populations together with their collective genomes, and its composition changes according to the body site in which they reside. It represents both the microbial communities and their genetic repertoire, with diversity shaped by the specific environment within the host. Of all human microbial habitats, the gut harbors the largest community, with an estimated 3.8 × 1013 bacteria roughly matching the total human cell count of 3.0 × 1013[1,2]. The composition of gut flora is individualised and dynamic, influenced by habits, nutrition, body weight, and cultural environment[3].

The dominant bacterial phyla in the gut include Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria, Fusobacteria, Proteobacteria, and Verrucomicrobia. The phyla Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes are the most predominant among these, comprising 70%-90% of the gut microbiota[3]. Firmicutes include both beneficial organisms, such as Lactobacillus and fiber-fermenting Rumino

Under physiological conditions, these microbial communities maintain homeostasis by aiding digestion, synthesizing vitamins, and producing short-chain fatty acids such as acetate, propionate, and butyrate, which preserve gut barrier integrity and modulate immune responses[7-10]. They also defend the host by competing with pathogenic organisms for nutrients and attachment sites, and by stimulating gut-associated lymphoid tissue[11]. This balance is highly sensitive to environmental influences. Diets rich in fat and sugar, sedentary behavior, or inappropriate antibiotic use can disturb microbial diversity, leading to dysbiosis. Such disruption has systemic consequences, including heightened inflammation and altered immune regulation[12-14].

Emerging evidence supports the concept of a gut-eye axis, wherein intestinal microbial imbalance may contribute to ocular disease[15]. Gut dysregulation can be assessed through several parameters, including overall species diversity and the ratio between the bacterial phyla Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes. These measures have been extensively examined in preclinical models investigating the gut-eye axis, yielding supportive findings[16,17]. Studies demonstrate that dysbiosis can activate dendritic cells and promote the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor alpha, while suppressing regulatory T-cell function. These changes may compromise the blood–retinal barrier, increase vascular permeability, and foster immune-mediated damage in the eye. In addition, microbial metabolites such as trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO) can enter systemic circulation and exert deleterious effects on ocular tissues[18].

Therapeutic approaches focused on modulating the intestinal microbiome present promising alternatives to traditional treatments for ocular inflammatory conditions. These strategies leverage the gut-eye connection to potentially control inflammation and disease progression in the eye by restoring or balancing microbiome health[1]. Treatment options include the use of prebiotics, probiotics, and fecal transplant therapy. Recently, attention has been focused on microbial components enhancing human health by promoting the growth of beneficial microbes like Lactobacillus, Bacteroides fragilis[19-21]. A prebiotic-rich diet that boosts butyrate-producing bacteria may help ease dry eye symptoms in Sjögren’s syndrome, linking gut microbiome changes to better eye health[22]. Probiotics influence critical signalling pathways within gut epithelial cells, promote mucus production, and enhance the tight junctions between these cells, hence, strengthening the intestinal barrier’s integrity[23,24]. However, there are major gaps, risks and limitations of the therapeutic promise of treatment of ocular disease related to gut dysbiosis. Precise pathways linking gut dysbiosis to ocular disease remain unclear, as most findings are based on animal models or small human associations. Modulating the gut microbiome could trigger systemic immune response, and gut-targeted therapies may affect other tissues or organs. Microbiome composition varies widely, making personalised therapy challenging when long-term effects of gut-modifying treatments are uncertain. Many microbiome-based therapies are still experimental and under investigation.

The experimental studies on autoimmune uveitis, dry eye, and diabetic retinopathy (DR) have shown efficacy in modulating immune responses in mouse models[25-27]. A study on a synbiotic formulation demonstrated improvement in uveitis and dry eye disease patients[28,29]. Current clinical evidence for the use of probiotics in ocular diseases remains limited, emphasizing the urgent need for large-scale randomized controlled trials to confirm their preventive and therapeutic efficacy[30].

Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) re-establishes eubiosis, reduces levels of inflammation, increases short-chain fatty acids (SCFA), and improves integrity of the gut barrier[31-34]. Emerging research has explored FMT as a modulator of the gut–eye axis, particularly focusing on its potential impact in autoimmune uveitis and Sjögren’s syndrome[35,36]. Although FMT is generally well tolerated, notable risks require careful consideration[37]. These include immediate complications from microbial translocation, potential long-term disruptions to the gut microbiome ecology, and increased sepsis risk in immunocompromised patients. Stringent donor screening and meticulous patient selection are crucial, especially for vulnerable individuals such as those with retinal disorders, to ensure both safety and treatment efficacy.

This systematic review provides a critical evaluation of how alterations in the gut microbiome contribute to the development of ocular disorders, highlighting new therapeutic opportunities for ophthalmology. It explores the composition and functional dynamics of the intestinal microbiota, along with dysbiosis-related changes, with particular emphasis on inflammatory eye diseases such as age-related macular degeneration, DR, glaucoma, retinal artery occlusion, uveitis, and dry eye. Potential interventions directed at restoring microbial balance are assessed as emerging approaches to reduce disease burden.

This study was conducted in accordance with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews & Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines and has been registered on the international prospective register of systematic reviews “PROSPERO” (registration number: CRD420251067162). A comprehensive literature search was carried out across multiple databases, including PubMed (MEDLINE), Scopus, EMBASE, and Cochrane Library. The primary keywords used in this extensive literature search included "gut microbiome", "intestinal flora", "dysbiosis", "ocular disease", "eye", "uveitis", "macular degeneration", "dry eye", "glaucoma", "diabetic retinopathy", "probiotics", "prebiotics", and "FMT". The search was confined to publications from 1997 to 2025 with no restriction on language.

A systematic search was performed using PubMed, Scopus, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Library to identify studies investigating the role of the gut microbiome in ocular health. The initial screening of published articles was conducted by examining titles and abstracts, followed by a full-text review completed independently by two reviewers. The inclusion criteria focused on human studies related to gut microbiome-associated ocular diseases, encompassing randomized controlled trials, prospective studies, cross-sectional studies, and case-control studies. Studies excluded from the analysis were reviews, case reports, opinion articles lacking full-text access, animal studies, and those investigating gut microbiome associations with systemic diseases unrelated to ocular conditions. Discrepancies in screening and quality assessment were resolved through consensus discussions between the reviewers.

Data extraction covered multiple variables, including study details (author, publication year, design, sample size), participant information (age, gender, diagnosis, disease severity, treatment goals, length of follow-up), methods used to assess the gut microbiome [such as ribosomal RNA (rRNA) sequencing, metagenomics, metabolomics], any interventions applied, and outcomes related to both ocular and gut health.

The primary objective was to systematically compile evidence regarding the link between gut microbiome dysbiosis and the occurrence, progression, severity, outcomes, and prognosis of ocular diseases. The secondary objective involved assessing the proposed mechanisms through which the gut microbiome affects ocular health. For ocular diseases with fully documented outcomes, a detailed disease-specific analysis was performed and included in the narrative review.

The risk of bias of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) was assessed by the Revised Cochrane Risk-of-Bias Tool for Randomized Trials (ROB2) tool, non-randomized trials were assessed by the risk of bias in non-randomized studies-of interventions (ROBINS-I) tool and for observational studies, quality assessment was done with the National Institutes of health (NIH) tool.

Study selection followed predefined eligibility standards and was summarized using a PRISMA flow diagram in Figure 1. The database search across PubMed (MEDLINE), EMBASE, Scopus, and the Cochrane Library identified 3077 records. After duplicates were removed, 3007 records were screened. Of these, 2952 were excluded after title and abstract review because they did not meet inclusion criteria or were not directly relevant to the study aims, often due to being experimental in design (Supplementary Tables 1-5). The remaining 55 studies underwent full-text evaluation, and 19 were excluded at this stage for not fulfilling eligibility requirements. Ultimately, 36 studies satisfied all criteria and were included in the final analysis of this review. This study reviewed various ocular pathologies involving either microbial communities or interference of the gut-inflammatory axis and summarised in Table 1. The bias assessment was displayed in Table 2. The bias assessment risk of two included RCTs (ROB2) and one non-randomised trial (ROBINS-I) was of low risk of bias. Quality assessment of observational studies was done with the NIH tool. Most of the included studies were of fair quality, with scores ranging from 6 to 8 among 14 questions (Supplementary Table 6).

| No. | Ref. | Type of study | Participants | Age (mean ± SD) | Ocular disease category | Methodology | Intervention, if any | Primary ocular outcome | GI outcome |

| 1 | Jayasudha et al[38], 2019 | Case-control | 14 uveitis, 24 HC | 43.64 ± 14.37, 45.92 ± 16.91 | Uveitis | Fecal fungal rRNA sequencing | None | None | Significant ↓ in gut fungal richness and diversity in uveitis patients compared to HC |

| 2 | Kalyana Chakravarthy et al[39], 2018 | Case-control | 13 uveitis, 13 HC | 44.54 ± 12.64, 43.08 ± 12.99 | Uveitis | Fecal 16S rRNA gene sequencing | None | None | Reduced diversity of several anti-inflammatory organisms in uveitis microbiomes; also ↓ probiotic and antibacterial organisms in uveitis |

| 3 | Huang et al[40], 2018 | Case-control | 38 AAU, 40 HC | 33.87 ± 8.77, 36.01 ± 6.87 | Uveitis | Fecal 16S rRNA gene sequencing | None | None | Significant difference in beta diversity of gut microbiota composition between AAU and controls; and also significant difference in fecal metabolite phenotype in uveitis patients from HC |

| 4 | Morandi et al[41], 2024 | Case-control study | 20 HLA-B27 uveitis, 27 control | 44.5 ± 16.3, 42.1 ± 14.9 | Uveitis | Fecal DNA sequencing | None | Bacteroides caccae may therefore play a protective role in the development of AU in HLA-B27-positive individual | AU development is associated with compositional and functional alterations of the GM |

| 5 | Wang et al[42], 2023 | Case-control | 37 Behcet’s uveitis, control-40 | Behcet uveitis | Fecal 16S rRNA gene sequencing | None | Restoration of healthy gut microbiota composition correlated with reduced ocular inflammation and slower progression of retinal disease | Targeting gut microbiota showed potential for modulating systemic immunity and ocular pathology | |

| 31 VKH, control-40 | VKH | None | |||||||

| 6 | Ye et al[43], 2020 | Case-control | 71 active VKH, 11 inactive VKH, 67 HC | 40.5 ± 15.1, 41.1 ± 13.5 | VKH | Fecal DNA sequencing | None | None | Depleted butyrate-producing bacteria, lactate-producing bacteria and methanogens as well as enriched Gram-negative bacteria were identified in the active VKH patients |

| 7 | Tecer et al[44], 2020 | Case-control | 7 BS, 12 (FMF), 9 CD and 16 HC | 35.57 ± 6.60, 32.17 ± 8.64, 35.00 ± 5.27, 39.38 ± 7.69 | Behcet’s syndrome | Fecal 16S rRNA gene sequencing | None | None | Significant differences in alpha diversity between four groups. Prevotella copri was dominant in BS group |

| 8 | Kim et al[45], 2021 | Case-control | 9 BD, 7 with RAU, 9 BD-matched HC, and 7 RAU-matched HC | Median 33, 47, 53, 44 | Behcet’s syndrome | Fecal 16S rRNA gene sequencing | None | BD patients with uveitis had different abundances of various taxa, compared to those without uveitis. Alterations in the fecal microbiome in patients with BD according to disease activity, and an association of the abundance of fecal bacterial species with BD disease activity and uveitis symptoms | A tendency toward clustering in the beta diversity & ↓ in alpha diversity of the fecal microbiome was observed between the active BD patients and HC. Active BD patients had a significantly higher abundance of fecal Bacteroides uniformis than their matched HC and patients with inactive disease state (P = 0.038) |

| 9 | Yasar Bilge et al[46], 2020 | Prospective cohort | 27 BD, 10 HC | 40.8 ± 9.3, 38.9 ± 4.9 | Behcet’s syndrome | Fecal 16S rRNA gene sequencing | None | None | No differences between the BD group and the control group in terms of alpha and beta microbial diversity and abundance indices (P > 0.05), significant differences in the relative abundance of some bacterial taxa between patient with BD and HC |

| 10 | Ye et al[47], 2018 | Case-control | 32 active BD and 74 HC | 47.1 ± 5.3, 45.9 ± 7.2 | Behcet’s syndrome | Fecal metagenomic DNA sequencing | None | None | Enriched in a SRB along with a lower level of butyrate-producing bacteria and methanogens |

| 11 | Zysset-Burri et al[48], 2019 | Case-control | 29 non-arteritic (RAO) and 30 HC | 69.4 ± 1.9, 69.0 ± 1.7 | RAO | Fecal DNA sequencing | None | None | Gut derived, TMAO was significantly higher in patients with RAO compared to controls (P = 0.023) |

| 12 | Zhang Y et al[49], 2023 | Case-control | 30 AMD, 17 control | Not applicable | AMD | Fecal 16S rRNA gene sequencing | None | None | Different bacterial compositions noted in the AMD compared to controls |

| 13 | Zysset-Burri et al[50], 2020 | Case-control | 12 nAMD, 11 control | 75.4 ± 8.3, 75.3 ± 7.1 | AMD | Fecal DNA sequencing | None | None | AMD patients show distinct gut microbiome composition and functional gene enrichment; genetic complement variants modulate these associations; microbiome–complement axis may contribute to AMD pathogenesis |

| 14 | Xue et al[51], 2023 | Case-control | 30 AMD, 30 control | 66.05 ± 9.26, 78.4 ± 7.4 | AMD | Fecal metagenomic DNA sequencing | None | Depleted Bacteroidaceae in patients with AMD was negatively associated with hemorrhage size | Gut microbiome may affect AMD severity by increasing intestinal permeability, thereby facilitating the translocation of microbes |

| 15 | Huang et al[52], 2021 | Cross sectional study | 25 DM without DR, 25 DM with DR, 25 control | 62.5 ± 5.2, 60.3 ± 9.1, 57.8 ± 7.5 | DR | Fecal 16S rRNA gene sequencing | None | None | Reduced alpha & beta diversity in both DM and DR groups compared to control |

| 16 | Moubayed et al[53], 2019 | Case-control | 9 diabetic patients without retinopathy, 8 diabetic patients with retinopathy, 18 HC | Not applicable | DR | Fecal DNA sequencing | None | None | Higher ratio of Bacteroides in diabetic groups than controls but no difference between those with and without retinopathy |

| 17 | Ye et al[54], 2021 | Case-control | 45 PDR, 90 diabetic without DR as control | 59.9 ± 11.3, 60.9 ± 9.9 | DR | Fecal 16S rRNA gene sequencing | None | None | Significantly lower bacterial diversity with significant depletion of 22 families and enrichment of 2 families in the PDR group as compared with the NDR group |

| 18 | Das et al[55], 2021 | Case-control | 25 with T2DM without DR, 28 with T2DM and DR, 30 HC | 57.3, 55.2, 52.2 | DR | Fecal 16S rRNA gene sequencing | None | None | Dysbiosis more pronounced in DR compared to DM, control & ↓ in anti-inflammatory, probiotic and pathogenic bacteria compared to HC |

| 19 | Jayasudha et al[56], 2020 | Cohort study | 21 DM, 24 DR, 30 HC | 57.5, 54.5, 52.2 | DR | Fecal DNA sequencing | None | None | More mycobiome dysbiosis in people with T2DM and DR than compared to HC |

| 20 | Khan R et al[57], 2021 | Case-control | 37 with sight Threatening DR, 21 control | 57.45 ± 8.08, 57.50 ± 7.60 | DR | Fecal DNA sequencing | None | None | No difference in gut microbial abundance between the 2 populations |

| 21 | Omar et al[58], 2024 | Prospective study | 23 were NM, 8 PM, and 21 SM | 31.96 ± 7.5, 32.35 ± 4.8, 30.62 ± 8.1 | Myopia | Fecal 16S rRNA gene sequencing | None | None | No significant differences in alpha and beta diversity between the three groups (NM, PM, and SM), Prevotella copri was predominant in stable myopia |

| 22 | Sun et al[59], 2024 | Case-control study | 35 myopia, 45 HC | Myopia | Fecal 16S rRNA gene sequencing | None | None | No significant difference in α diversity while β diversity reached a significant level | |

| 23 | Skondra et al[60], 2021 | Cross sectional study | 6 infants with type 1 ROP and 4 preterm infants without any ROP | 24.1 weeks, 25.6 weeks | ROP | Fecal 16S rRNA gene sequencing | None | Absence of Enterobacteriaceae overabundance, in addition to enrichment of amino acid biosynthesis pathways, may protect against severe ROP in high-risk preterm infants | Significant enrichment of Enterobacteriaceae & ↓ amino acid biosynthesis pathways in type 1 ROP |

| 24 | Chang et al[61], 2024 | Case-control study | 13 with type 1 ROP, 44 with type 2, and 53 without ROP | ROP | Fecal 16S rRNA gene sequencing | None | Reduced gut microbial diversity may be associated with ROP development in high-risk preterm infants | Type 1 ROP showed no significant difference in microbial diversity up to 8 postnatal weeks (P = 0.057), while type 2 and no ROP groups displayed increased diversity (P = 0.0015 and P = 0.049, respectively) | |

| 25 | Berkowitz et al[62], 2022 | Case-control | 25 IIH, 20 HC | 35.12, 48.5 | IIH | Fecal DNA sequencing | Acetazolamide examined in IIH patients | None | Lower diversity of bacterial species in IIH patients compared with HC, ↑ in Lactobacillus brevis, (beneficial bacterium) in acetazolamide treated patients |

| 26 | Gong et al[63], 2020 | Case-control | 30 POAG, 30 control | 54.77 ± 9.32, 53.80 ± 7.87 | POAG | Fecal 16S rRNA gene sequencing | None | Mean visual acuity was negatively correlated with Blautia, mean VF-MD was negatively correlated with Faecalibacterium, and average RNFL thickness was positively correlated with Streptococcus | Bacterial profile in the gut microbiome had significant differences between the POAG and control |

| 27 | Kalyana Chakravarthy et al[64], 2018 | Case-control | 32 fungal keratitis, 31 HC | 47.1, 42.2 | Fungal keratitis | Fecal 16S rRNA gene sequencing | None | None | No significant difference in fungal dysbiosis, but bacterial richness and diversity was significantly decreased in FK patients, strong association of disease phenotype with ↓ in beneficial bacteria and increase in pro-inflammatory and pathogenic bacteria in FK patients |

| 28 | Jayasudha et al[65], 2018 | Case-control | 19 BK, 21 HC | 48.8 | Bacterial keratitis | Fecal DNA sequencing | None | None | ↑ In number of antiinflammatory organisms in HC compared to BK |

| 29 | Mendez et al[66], 2020 | Case-control | 13 with Sjögren + dry eye, 8 with Sjögren without dry eye, 21 HC | 58.8 ± 10, 58.4 ± 726.0 | Sjögren syndrome | Fecal 16S rRNA gene sequencing | None | None | Shannon’s diversity index showed no differences between groups Faith’s phylogenetic diversity showed increased diversity in cases vs controls, which reached significance when comparing SDE and controls (P = 0.02) |

| 30 | Moon et al[67], 2020 | Case-control | 10 SS, 14 with environmental DES, 12 HC | 58.5 ± 3.05, 46.29 ± 2.6, 47.5 ± 4.05 | Sjögren syndrome | Fecal 16S rRNA gene sequencing | None | Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria and Bifidobacterium were significantly related with dry eye signs (P < 0.05), multivariate linear regression analysis revealed tear secretion was strongly affected by Prevotella (P = 0.025) | Gut microbiome showed significant differences in patients with Sjögren than compared to controls & DES; no significant difference in alpha-diversity across all 3 groups |

| 31 | Watane et al[68], 2021 | Non-randomized clinical trial | 10 dry eye due to Sjögren syndrome | 60.4 ± 4.2 | Sjögren syndrome | Fecal DNA sequencing | FMT | Improvement of subjective dry eye symptoms in 5 individuals after FMT at 3 month follow up | No side effect after FMT |

| 32 | Filippelli et al[69], 2021 | RCT | 26 children with chalazion | 8.3 | Chalazion | None | Probiotic supplementation | Decreased time to resolution of chalazion in probiotic group (P < 0.0001) | No adverse effect |

| 33 | Filippelli et al[70], 2022 | RCT | 20 adults with chalazion | 48.25 | Chalazion | None | Probiotic supplementation | Decreased time to resolution of small size. Chalazion in probiotic group (P < 0.039). Failure to resolve medium or large chalazion | No adverse effect |

| 34 | Yang et al[71], 2024 | Case-control study | 145 GD, 156 GO, 100 HC | 36, 44.50, 38 | Grave’s disease | Fecal 16S rRNA gene sequencing | None | Levels of IAA were negatively correlated with clinical activity score and serum TRAb in GO patients | Trp metabolites IAA maybe a novel biomarker for GO progression. and IPA, ILA and IAA may play a protective role in GO |

| 35 | Zhang et al[72], 2024 | Case-control study | 30 TAO, 29 HC | 43.40 ± 10.38, 41.79 ± 7.61 | Thyroid ophthalmopathy | Fecal 16S rRNA gene sequencing | None | Veillonella demonstrated a positive correlation with exophthalmos. Conversely, Alloprevotella showed a negative correlation with exophthalmos. Dialister and Clostridium sensu stricto 1 exhibited positive correlations with disease severity, while Streptococcus showed a negative correlation with disease severity | Reduced gut richness and diversity observed in patients with TAO |

| 36 | Zhang et al[73], 2023 | Case-control study | 62 GO, 18 HC | Graves orbitopathy | Fecal 16S rRNA gene sequencing | None | Klebsiella pneumoniae was positively correlated with disease severity | No remarkable difference in gut microbiota diversity between groups; however, the gut microbial community and dominant microbiota significantly differed among groups |

| Ref. | Type of study | Quality of evidence (NIH tool for observational studies) (ROBINS-I for non-randomized trial) (ROB2 for RCT) |

| Jayasudha et al[38], 2019 | Case-control | 8 |

| Kalyana Chakravarthy et al[39], 2018 | Case-control | 6 |

| Huang et al[40], 2018 | Case-control | 8 |

| Morandi et al[41], 2024 | Case-control | 8 |

| Wang et al[42], 2023 | Case-control | 8 |

| Ye et al[43], 2020 | Case-control | 8 |

| Tecer et al[44], 2020 | Case-control | 8 |

| Kim et al[45], 2021 | Case-control | 8 |

| Yasar Bilge et al[46], 2020 | Cohort | 9 |

| Ye et al[47], 2018 | Case-control | 8 |

| Zysset-Burri et al[48], 2019 | Case-control | 8 |

| Zhang et al[49], 2023 | Case-control | 8 |

| Zysset-Burri et al[50], 2020 | Case-control | 8 |

| Xue et al[51], 2023 | Case-control | 6 |

| Huang et al[52], 2021 | Cross-sectional | 8 |

| Moubayed et al[53], 2019 | Case-control | 8 |

| Ye et al[54], 2021 | Case-control | 8 |

| Das et al[55], 2021 | Case-control | 8 |

| Jayasudha et al[56], 2020 | Cohort study | 9 |

| Khan et al[57], 2021 | Case-control | 8 |

| Omar et al[58], 2024 | Cohort | 8 |

| Sun et al[59], 2024 | Case-control | 8 |

| Skondra et al[60], 2021 | Cross-sectional | 8 |

| Chang et al[61], 2024 | Case-control | 7 |

| Berkowitz et al[62], 2022 | Case-control | 8 |

| Gong et al[63], 2020 | Case-control | 8 |

| Kalyana Chakravarthy et al[64], 2018 | Case-control | 8 |

| Jayasudha et al[65], 2018 | Case-control | 8 |

| Mendez et al[66], 2020 | Case-control | 8 |

| Moon et al[67], 2020 | Case-control | 8 |

| Watane et al[68], 2021 | Non-randomized clinical trial | Low risk of bias |

| Filippelli et al[69], 2021 | Randomized control Trial | Low risk of bias |

| Filippelli et al[70], 2022 | Randomized control trial | Low risk of bias |

| Yang et al[71], 2024 | Case-control | 8 |

| Zhang et al[72], 2024 | Case-control | 8 |

| Zhang et al[73], 2023 | Case-control | 8 |

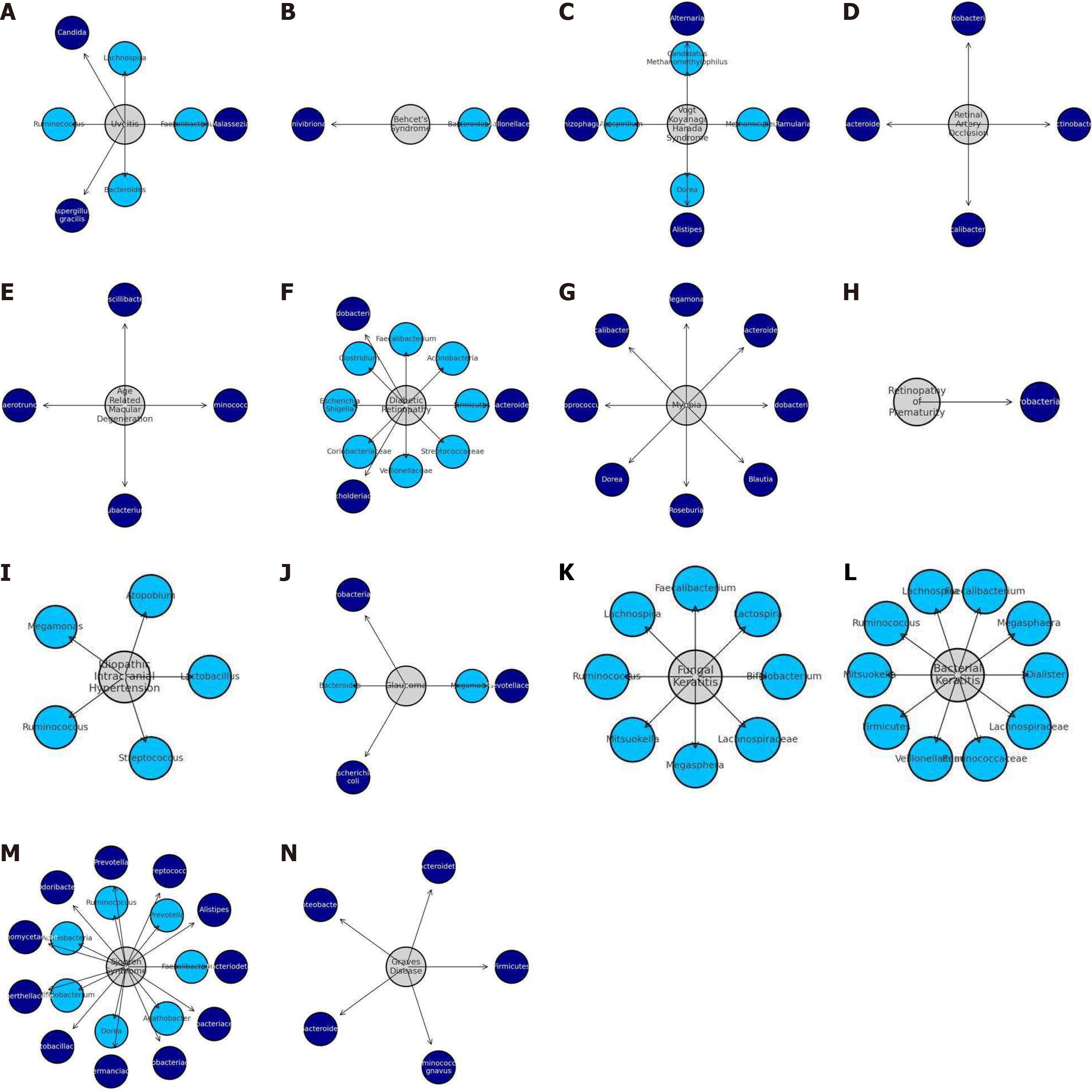

Recent studies have linked dysbiosis to various ocular diseases such as bacterial and fungal keratitis, dry eye syn

| Ocular disease category | Implicated micro-organisms increase | Implicated micro-organisms decrease |

| Uveitis | Malassezia, Candida, Candida, Aspergillus gracilis | Faecalibacterium, Lachnospira, Ruminococcus, Bacteroides |

| Behcet’s syndrome | Veillonellaceae, Succinivibrionaceae | Bacteroidaceae |

| Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome | Ramularia, Alternaria and Rhizophagus, Alistipes | Methanoculleus, Candidatus Methanomethylophilus and Azospirillum Dorea |

| Retinal artery occlusion | Actinobacter, Bifidobacterium, Bacteroides, Faecalibacterium | |

| Age related macular degeneration | Ruminococcus, Oscillibacter, Anaerotruncus, Eubacterium | |

| Diabetic retinopathy | Bacteriodes, Bifidobacterium, Burkholderiaceae | Firmicutes, Actinobacteria, Faecalibacterium, Clostridium, Escherichia Shigella, Coriobacteriaceae, Veillonellaceae, Streptococcaceae |

| Myopia | Bifidobacterium, Bacteroides, Megamonas, Faecalibacterium, Coprococcus, Dorea, Roseburia, and Blautia | |

| Retinopathy of prematurity | Enterobacteriaceae | |

| Idiopathic intracranial hypertension | Lactobacillus, Atopobium, Megamonas, Ruminococcus, Streptococcus | |

| Glaucoma | Prevotellaceae, Enterobacteriaceae, Escherichia coli | Megamonas, Bacterioides |

| Fungal keratitis | Bifidobacterium, Lactospira, Faecalibacterium, Lachnospira, Ruminococcus, Mitsuokella, Megasphera and Lachnospiraceae | |

| Bacterial keratitis | Dialister, Megasphaera, Faecalibacterium, Lachnospira, Ruminococcus, Mitsuokella, Firmicutes, Veillonellaceae, Ruminococcaceae and Lachnospiraceae | |

| Sjögren syndrome | Bacteriodetes, Alistipes, Streptococcus, Prevotella, Odoribacter, Actinomycetaceae, Eggerthellaceae, Lactobacillaceae, Akkermanciaceae, Coriobacteriaceae, and Eubacteriaceae | Faecalibacterium, Prevotella, and Ruminococcus, Actinobacteria, Bifidobacterium, Dorea, Agathobacter |

| Grave’s disease | Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Proteobacteria, Bacteroides, Ruminococcus gnavus |

Out of 4 studies on uveitis, one study reported dysbiosis of pathogenic Aspergillus and Candida in uveitic eyes compared to controls[38], while another found no significant differences in composition of microbiota between cases and controls. Affected patients exhibit a decreased diversity of anti-inflammatory microbial species[39]. A number of butyrate-producing bacteria, including Lachnospira, Dialister, Dorea, Blautia, Faecalibacterium, Akkermansia muciniphila, Megasphaera, and Roseburia, were found to be diminished in abundance[40]. Bacteroides caccae play a protective role in the development of anterior uveitis in HLA-B27-positive individual[41].

Out of 2 studies on Vogt–Koyanagi–Harada disease (VKH), one study showed reduced ocular inflammation and slower progression of retinal disease after restoration of healthy gut microbiota[42], while the other showed a mix of Bacteroides enterotype enriched with Bacteroides species, Paraprevotella species, Prevotella species, and Parabacteroides species, accompanied by a decrease in lactate-producing bacteria[43].

Among five available studies on Behçet’s disease, two demonstrated notable changes in alpha and beta microbial diversity[44,45], while one study did not detect any variation between cases and controls[46]. One study showed a decrease in Lachnospiraceae, Dorea, Blautia, Coprococcus, Erysipelotrichaceae and an increase in Bilophila and Stenotrophomonas in Behçet's-related uveitis patients[42]. An enrichment of sulfate-reducing bacteria has been observed, along with a decline in butyrate producers and methanogenic species[47].

There are reports of significantly higher atherogenic metabolite TMAO in retinal artery occlusion (RAO) patients compared to controls, with a direct association between TMAO and an increase in Akkermansia[48].

Reports indicate that the gut microbiome shows distinct alterations, with markedly reduced Firmicutes and relatively increased Proteobacteria and Bacteroidota[49,50]. One study showed a negative association of hemorrhage size in age-related macular degeneration (AMD) patients with depleted Bacteroidaceae[51].

Six studies have been published on the association of dysbiosis with DR, out of which 4 showed significant bacterial dysbiosis[52-55], while one study showed more mycobiome dysbiosis in DR compared to healthy controls[56]. However, one study has shown no difference in gut microbial flora in sight threatening DR[57].

Research in myopic patients revealed enrichment of gut bacteria linked to dopamine signaling and gamma-aminobutyric acid production, implicating these taxa in the development and progression of myopia. Prevotella copri was predominant in stable myopia[58]. The other study revealed a close relation of adolescent myopia to the gut microbiota[59].

A study on retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) showed depletion of Enterobacteriaceae as a protecting factor against ROP in preterm infants at high-risk[60] while another study showed reduced gut microbial diversity associated with ROP development in high-risk preterm infants[61].

The study also reported an increase in lactobacillus in acetazolamide-treated patients with idiopathic intracranial hypertension, suggesting gut dysbiosis serving as an immunometabolic and neurovascular modulator[62].

A study on primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) demonstrated an alteration in the bacterial profile of the gut microbiome. Findings indicated that higher abundance of Blautia correlated with poorer visual acuity, and Faecalibacterium levels were inversely related to mean visual field mean deviation. In contrast, retinal nerve fiber layer thickness showed a positive relationship with Streptococcus abundance[63].

In a study on fungal keratitis, no significant differences in fungal community composition were observed; however, bacterial richness and diversity were markedly reduced[64], while another study on bacterial keratitis found abundance in Prevotella copri (pro-inflammatory action)[65].

Out of 3 studies, two showed significant differences in gut microbiome diversity, with one study giving a significant relation of Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria, and Bifidobacterium with dry eye signs and Prevotella with tear secretion[66,67]. An interventional study evaluating FMT reported improvement in subjective dry eye symptoms in half of the patients at a 3-month follow-up[68].

Probiotic therapy has been assessed in two studies of chalazion. The pediatric trial reported a reduced time to lesion resolution[69], whereas the adult trial showed benefit only for smaller chalazia, with no improvement seen in larger ones[70].

One study reported significantly reduced serum concentrations of indolepropionic acid, indole-3-lactate, and indoleacetic acid (IAA) in patients with both Graves’ disease and Graves’ orbitopathy, with IAA identified as a potential biomarker for Graves’ orbitopathy progression[71]. Another investigation found strong associations between Veillonella and Megamonas and the clinical features of thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy, while Klebsiella pneumoniae showed a positive correlation with disease severity[72,73].

This systematic review offers a comprehensive synthesis of current evidence linking gut microbiota with ocular diseases. Expanding upon the foundational work of Bu et al[74], our analysis not only reinforces the concept of a gut–eye axis but also critically appraises methodological quality, biological plausibility, and the translational relevance of this emerging field. While prior reviews have catalogued preliminary associations between gut dysbiosis and ocular pathology, they often lacked mechanistic findings and a predictive strategy for future research. This review addresses these deficiencies by incorporating structured quality assessment tools and qualitative analysis of included studies.

Traditional culture-based methods yield a far less diverse microbial profile compared with modern molecular approaches[75]. Genomic techniques, particularly 16S rRNA polymerase chain reaction, allow broader identification of bacterial taxa from a given niche than culture techniques[76]. In this review, 23 of the 36 included studies employed 16S rRNA gene sequencing. Research on the intestinal microbiome faces several methodological challenges: Appropriate sample collection, preservation of specimen stability, and reliable downstream processing are critical for accurate DNA sequencing[77]. In clinical settings, factors such as diet, medication use, gut motility, and stool characteristics must also be considered when interpreting microbiota data[78,79]. Cross-sectional studies may be confounded by such environmental influences, and observed associations cannot establish causality. Therefore, randomized controlled clinical trials, inclu

Huang et al[40] reported no significant difference in gut microbial composition between uveitis cases and controls, suggesting bacteria may not play a central role in disease onset. This was further supported by Jayasudha et al[38], who identified increased fungal pathogens such as Aspergillus and Candida in affected patients, while Kalyana Chakravarthy et al[39] observed reduced diversity of anti-inflammatory bacterial species. Multiple butyrate-producing taxa, including Lachnospira, Dialister, Dorea, Blautia, Faecalibacterium, Akkermansia muciniphila, Magasphaera, and Roseburia, were found to be decreased. The decline in these protective microbes may exacerbate inflammatory activity. Napolitano et al[79] docu

In VKH, active disease is associated with depletion of butyrate/Lactate producers and methanogens, alongside enrichment of Gram-negative taxa. Parallel studies also demonstrate distinct mycobiome changes, indicating that bacteria and fungi jointly influence disease expression[43].

Tecer et al[44] documented a significant decline in gut microbial diversity among patients with Behçet’s disease compared with controls. Reduced butyrate production was also observed, which impaired regulatory T-cell activity and may contribute to disease pathogenesis[80]. Consistently, the genera Roseburia and Subdoligranulum were diminished in the fecal microbiota of affected individuals[81]. Across different clinical phenotypes, additional microbial variations were noted, with Lachnospiraceae particularly associated with Behçet’s patients presenting with uveitis, reinforcing the connection between gut imbalance and ocular pathology[46].

Beyond traditional risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes, and atherosclerosis, recent evidence suggests a role for gut dysbiosis in the development of RAO. Translocation of microbial products from the gut may aggravate systemic inflammation and endothelial dysfunction. Zysset-Burri et al[48] reported elevated TMAO levels in RAO patients, which correlated positively with Akkermansia abundance, indicating a possible mechanistic link between gut microbiota and RAO. The detection of microbial DNA within atherosclerotic plaques, together with raised concentrations of the pro-atherogenic metabolite TMAO, further supports the concept of a “gut–retina–vascular axis” in this disease[82,83].

Dysbiosis of the gut microbiota has been increasingly linked to AMD, particularly via mechanisms involving impaired intestinal barrier function[49,84]. Risk has been correlated with enrichment of Peptococcaceae, Bilophila, Faecalibacterium, and Roseburia, while protective associations were seen with Candidatus Solaeferrea, Desulfovibrio, and the Eubacterium ventriosum group[85]. While Zhang et al[49] found an increase in wet AMD cases, Baldi et al[84] found reductions in Bacteroidota, Bacteroidales, and Prevotellaceae abundance. Patients with AMD exhibit a significant decline in saturated fatty acid production, and wet AMD cases show decreased abundance of SCFA-producing microbes such as Phascolarctobacterium and Parabacteroides, underscoring the anti-inflammatory potential of SCFAs and their therapeutic implications in ocular health[85-87]. Several studies have demonstrated that patients with AMD display a unique gut microbial signature with diminished diversity and shifts in critical taxa. This dysbiosis compromises SCFA metabolism and lowers production of protective metabolites, while simultaneously enhancing systemic exposure to endotoxins and pathogen-associated molecular patterns, a pattern also described in other retinal disorders[88]. These molecules can activate retinal microglia and complement pathways, both of which are implicated in drusen formation and choroidal neovascularisation[89].

Gut microbial dysbiosis in DR drives immune dysregulation, which in turn accelerates vascular injury within the retina[90]. Alterations in microbial composition include a decline in Actinobacteria and Bacteroidetes, together with an overrepresentation of Escherichia, Faecalibacterium, and Prevotella[55,91]. Contradictory findings show that certain DR groups have elevated Bacteroidetes[52]. Qin and colleagues demonstrated that DR patients had diminished levels of Butyricicoccus and Ruminococcus torques, coupled with lower circulating SCFAs, consistent with compromised gut barrier function and heightened inflammatory signalling[92]. Microbial metabolites such as TMAO were found to be elevated in DR and associated with disease severity[93]. Similarly, succinate, a metabolite produced by microbial fermentation, was decreased in the ocular fluids of DR patients, suggesting metabolic contributions from the gut microbiota. Serban et al[94] analysed eight prospective cohort studies from 2020-2022 involving over 200 T2DM patients with DR and corresponding controls, focusing on gut microbiome diversity and composition using mainly 16S rRNA sequencing. Findings consistently showed a distinctive gut microbiota profile in DR characterised by decreased abundance of anti-inflammatory and short-chain fatty acid-producing bacteria. It also highlighted the potential therapeutic approaches to modulate gut dysbiosis in DR, including probiotics (Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium), dietary fibre, and engineered probiotics targeting pathways to reduce retinal inflammation and damage.

Omar et al[58] found that myopic individuals, including those with simple myopia (SM) and pathological myopia (PM), exhibited significantly higher abundances of Bacteroides, Bifidobacterium, Clostridium, and Ruminococcus. Furthermore, Prevotella copri was notably more abundant in SM compared to PM. These findings suggest distinct gut microbiome profiles in myopia, warranting further investigation into their potential role in myopia pathogenesis and progression. All of these bacterial genera are involved in modulating dopaminergic signalling pathways[95].

Emerging evidence suggests a potential role of the gut–retina axis, where intestinal dysbiosis may contribute to abnormal retinal angiogenesis by impairing vascular repair and disrupting vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) signalling. Increased gut permeability and endotoxemia may worsen retinal hypoxia and neovascularisation. While these associations support the gut–retina axis in ROP pathogenesis, causality remains unproven, and local oxygen fluctuations remain the primary driver of VEGF expression[96]. Small cohort studies support these associations, though results are limited by confounding factors such as antibiotic use, sepsis, and necrotizing enterocolitis[92,97]. The study by Skondra et al[60] concluded that a decline in Enterobacteriaceae and upregulation of amino acid biosynthesis pathways has been identified as protective factor against the development of severe ROP in high-risk preterm infants.

The gut–brain–eye axis interconnects intestinal microbiota with neuro-ophthalmic health through immune modulation, molecular mimicry, and vascular/metabolic influence (affecting intracranial pressure and perfusion). Decreased levels of Lactobacillus, Atopobium, Megamonas, Ruminococcus, Streptococcus have been implicated in idiopathic intracranial hyperten

Increasing evidence implicates the gut microbiome in modulating both susceptibility and progression of glaucoma through systemic immune and metabolic pathways. A pilot study conducted by Chen et al[98] explored the correlation of POAG and gut microbiota. A bidirectional Mendelian randomisation analysis conducted by Wu et al[99] concluded that the bacterial family Oxalobacteraceae and the genus Eggerthella negatively impact glaucoma, while the genera Bilophila, Lachnospiraceae, and Ruminiclostridium exert a positive effect. Additionally, increased levels of microbial metabolites like trimethylamine have been detected in the aqueous humor of patients with POAG[100]. McPherson et al[101] reported increased probability of glaucoma in patients with irritable bowel syndrome (OR = 5.84).

Kalyana Chakravarthy et al[64] and Jayasudha et al[65] found variation in gut bacterial and fungal microbiota in patients with keratitis compared to control patients. An increase in Aspergillus and Malassezia species in patients with bacterial keratitis suggests these fungi may contribute to heightened host vulnerability to bacterial corneal infections. In fungal keratitis, gut dysbiosis has been shown to disrupt Th17/Treg balance, promoting excessive inflammation that aggravates stromal damage. Jayasudha et al[65] observed that a significant decline in bacterial genera such as Dialister, Megasphaera, Lachnospira, Ruminococcus, Veillonellaceae, Ruminococcaceae, and Lachnospiraceae and increase in pro-inflammatory bacteria like Prevotella copri, Bilophila, Enterococcus, Dysgonomonas.

Studies have identified distinct changes in the gut microbiota of individuals with dry eye disease, especially those with Sjögren’s syndrome. These changes include a decline in beneficial bacteria such as Faecalibacterium and Bacteroides, alongside an increase in potentially harmful bacteria like Streptococcus and Escherichia/Shigella[102]. Regarding dry eye secondary to Sjögren’s syndrome, a decline in Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio and Bifidobacterium has been observed, suggesting that the disease’s severity is related to the groups of bacteria involved[67]. Interventions aimed at modulating the gut microbiome, including dietary changes, probiotic supplementation, and prebiotics, have demonstrated potential in enhancing tear film stability and alleviating ocular surface inflammation[103]. An RCT showed that a synbiotic mixture significantly improved tear secretion and ocular surface health in patients with dry eye disease[104].

Gut microbiome may indirectly modulate the risk and recurrence of chalazion through systemic inflammatory and metabolic pathways. Zhang et al[105] performed a two-sample Mendelian randomization study that demonstrated a causal link between the gut microbiome and chalazion. Their findings identified Catenibacterium, belonging to the phylum Firmicutes, as associated with a higher risk of chalazion, whereas Veillonella was found to have a protective effect[106]. Filippelli et al[69,70] reported a substantial reduction in the resolution time of the chalazion post probiotic supplementation.

Microbiota-derived tryptophan metabolites may protect against Graves’ orbitopathy by modulating inflammation and cell proliferation in orbital fibroblasts through inhibition of the Akt signaling pathway[107]. This suggests that targeting these metabolites could offer therapeutic potential for Graves’ orbitopathy through dietary interventions or oral probiotic supplementation. The decreased abundance of Ruminococcus gnavus in patients with thyroid-associated orbitopathy may contribute to disease development by promoting the activation of effector T cells[72].

While this review offers a critical advance over previous syntheses, several limitations must be acknowledged. The heterogeneity of included studies precluded quantitative meta-analysis. This review lacks causal association and also mechanistic link. Research article or RCT is mandated to establish a causal relationship, which is currently not available in the present literature. Many aspects, like specific pathogenic mechanisms, are still not fully clarified. Given the emerging nature of this field, many included studies were exploratory and lacked replication cohorts. Nonetheless, these limitations reflect broader challenges in microbiome research and reinforce the need for methodological standardization.

Given the established connection between gut microbiota and immune-related diseases, future research should focus on clarifying the role of gut commensal bacteria in shaping and sustaining the host's immune homeostasis. Uveitis patients exhibited changes in gut fungal diversity, underscoring the importance of considering the entire gut microbiome to optimize the effectiveness of FMT. Since probiotic effects are highly strain-specific, their therapeutic benefits cannot be broadly applied to entire genera or species. This highlights the necessity for precise selection and detailed characterization of probiotic strains for clinical use. Given the cooperative and dynamic interactions among gut bacteria, future therapeutic approaches may be more successful by employing multi-strain probiotic formulations that can synergistically and sustainably reshape the microbial ecosystem. Future research should aim to identify specific prebiotic compounds, optimise their dosage and administration, and clinically validate their benefits.

Accumulating evidence accentuates the role of the gut microbiome in the pathogenesis of ophthalmic diseases, positioning it as a promising target for both preventive and therapeutic strategies. Disruptions in microbial balance can alter immune regulation, promote inflammation, and impair the blood–retinal barrier, thereby contributing to conditions such as uveitis, AMD, DR, dry eye disease, and glaucoma. Numerous studies demonstrate that microbial imbalance affects systemic immunity and metabolism, with changes observed in T- and B-cell activity, cytokine profiles, and host metabolic responses. Although the underlying mechanisms remain incompletely defined, interventions that modify the microbiome, such as probiotics, prebiotics, synbiotics, and FMT, offer emerging therapeutic potential. At present, most supporting data derive from animal models; thus, well-designed human clinical trials are urgently needed to establish their efficacy and safety in ophthalmic care. A deeper understanding of gut–eye interactions may also lead to novel biomarkers for disease risk stratification and treatment responsiveness, paving the way toward personalized therapeutic approaches in ophthalmology.

| 1. | Sender R, Fuchs S, Milo R. Revised Estimates for the Number of Human and Bacteria Cells in the Body. PLoS Biol. 2016;14:e1002533. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2328] [Cited by in RCA: 3101] [Article Influence: 310.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 2. | Thursby E, Juge N. Introduction to the human gut microbiota. Biochem J. 2017;474:1823-1836. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1710] [Cited by in RCA: 2232] [Article Influence: 248.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (8)] |

| 3. | Rinninella E, Raoul P, Cintoni M, Franceschi F, Miggiano GAD, Gasbarrini A, Mele MC. What is the Healthy Gut Microbiota Composition? A Changing Ecosystem across Age, Environment, Diet, and Diseases. Microorganisms. 2019;7:14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 969] [Cited by in RCA: 2283] [Article Influence: 326.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 4. | Kho ZY, Lal SK. The Human Gut Microbiome - A Potential Controller of Wellness and Disease. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:1835. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 451] [Cited by in RCA: 694] [Article Influence: 86.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (20)] |

| 5. | Vavricka SR, Schoepfer A, Scharl M, Lakatos PL, Navarini A, Rogler G. Extraintestinal Manifestations of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21:1982-1992. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 546] [Cited by in RCA: 501] [Article Influence: 45.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lin P. The role of the intestinal microbiome in ocular inflammatory disease. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2018;29:261-266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kammoun S, Rekik M, Dlensi A, Aloulou S, Smaoui W, Sellami S, Trigui K, Gargouri R, Chaari I, Sellami H, Elatoui D, Khemakhem N, Hadrich I, Neji S, Abdelmoula B, Bouayed Abdelmoula N. The gut-eye axis: the retinal/ocular degenerative diseases and the emergent therapeutic strategies. Front Cell Neurosci. 2024;18:1468187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Czajkowska A, Kaźmierczak-Siedlecka K, Jamioł-Milc D, Gutowska I, Skonieczna-Żydecka K. Gut microbiota and its metabolic potential. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2020;24:12971-12977. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lei L, Zhao N, Zhang L, Chen J, Liu X, Piao S. Gut microbiota is a potential goalkeeper of dyslipidemia. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022;13:950826. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Johnson AJ, Vangay P, Al-Ghalith GA, Hillmann BM, Ward TL, Shields-Cutler RR, Kim AD, Shmagel AK, Syed AN; Personalized Microbiome Class Students, Walter J, Menon R, Koecher K, Knights D. Daily Sampling Reveals Personalized Diet-Microbiome Associations in Humans. Cell Host Microbe. 2019;25:789-802.e5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 308] [Cited by in RCA: 501] [Article Influence: 71.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Raza MH, Gul K, Arshad A, Riaz N, Waheed U, Rauf A, Aldakheel F, Alduraywish S, Rehman MU, Abdullah M, Arshad M. Microbiota in cancer development and treatment. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2019;145:49-63. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Monda V, Villano I, Messina A, Valenzano A, Esposito T, Moscatelli F, Viggiano A, Cibelli G, Chieffi S, Monda M, Messina G. Exercise Modifies the Gut Microbiota with Positive Health Effects. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2017;2017:3831972. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 217] [Cited by in RCA: 406] [Article Influence: 45.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 13. | Madison A, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. Stress, depression, diet, and the gut microbiota: human-bacteria interactions at the core of psychoneuroimmunology and nutrition. Curr Opin Behav Sci. 2019;28:105-110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 239] [Article Influence: 34.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kesavelu D, Jog P. Current understanding of antibiotic-associated dysbiosis and approaches for its management. Ther Adv Infect Dis. 2023;10:20499361231154443. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kugadas A, Wright Q, Geddes-McAlister J, Gadjeva M. Role of Microbiota in Strengthening Ocular Mucosal Barrier Function Through Secretory IgA. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2017;58:4593-4600. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Radjabzadeh D, Uitterlinden AG, Kraaij R. Microbiome measurement: Possibilities and pitfalls. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2017;31:619-623. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Allaband C, McDonald D, Vázquez-Baeza Y, Minich JJ, Tripathi A, Brenner DA, Loomba R, Smarr L, Sandborn WJ, Schnabl B, Dorrestein P, Zarrinpar A, Knight R. Microbiome 101: Studying, Analyzing, and Interpreting Gut Microbiome Data for Clinicians. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17:218-230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 205] [Article Influence: 29.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Zysset-Burri DC, Morandi S, Herzog EL, Berger LE, Zinkernagel MS. The role of the gut microbiome in eye diseases. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2023;92:101117. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 18.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Zhang X, M VJ, Qu Y, He X, Ou S, Bu J, Jia C, Wang J, Wu H, Liu Z, Li W. Dry Eye Management: Targeting the Ocular Surface Microenvironment. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:1398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in RCA: 165] [Article Influence: 18.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Klenkler B, Sheardown H. Growth factors in the anterior segment: role in tissue maintenance, wound healing and ocular pathology. Exp Eye Res. 2004;79:677-688. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 142] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Knop E, Knop N. Anatomy and immunology of the ocular surface. Chem Immunol Allergy. 2007;92:36-49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Rastmanesh R. Aquaporin5-Targeted Treatment for Dry Eye Through Bioactive Compounds and Gut Microbiota. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2021;37:464-471. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Liu Y, Wang J, Wu C. Modulation of Gut Microbiota and Immune System by Probiotics, Pre-biotics, and Post-biotics. Front Nutr. 2021;8:634897. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 173] [Article Influence: 43.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Nagpal R, Wang S, Ahmadi S, Hayes J, Gagliano J, Subashchandrabose S, Kitzman DW, Becton T, Read R, Yadav H. Human-origin probiotic cocktail increases short-chain fatty acid production via modulation of mice and human gut microbiome. Sci Rep. 2018;8:12649. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 258] [Article Influence: 32.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Dusek O, Fajstova A, Klimova A, Svozilkova P, Hrncir T, Kverka M, Coufal S, Slemin J, Tlaskalova-Hogenova H, Forrester JV, Heissigerova J. Severity of Experimental Autoimmune Uveitis Is Reduced by Pretreatment with Live Probiotic Escherichia coli Nissle 1917. Cells. 2020;10:23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Prasad R, Floyd JL, Dupont M, Harbour A, Adu-Agyeiwaah Y, Asare-Bediako B, Chakraborty D, Kichler K, Rohella A, Li Calzi S, Lammendella R, Wright J, Boulton ME, Oudit GY, Raizada MK, Stevens BR, Li Q, Grant MB. Maintenance of Enteral ACE2 Prevents Diabetic Retinopathy in Type 1 Diabetes. Circ Res. 2023;132:e1-e21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Verma A, Zhu P, Xu K, Du T, Liao S, Liang Z, Raizada MK, Li Q. Angiotensin-(1-7) Expressed From Lactobacillus Bacteria Protect Diabetic Retina in Mice. Transl Vis Sci Technol. 2020;9:20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Askari G, Moravejolahkami AR. Synbiotic Supplementation May Relieve Anterior Uveitis, an Ocular Manifestation in Behcet's Syndrome. Am J Case Rep. 2019;20:548-550. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Tavakoli A, Markoulli M, Papas E, Flanagan J. The Impact of Probiotics and Prebiotics on Dry Eye Disease Signs and Symptoms. J Clin Med. 2022;11:4889. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 30. | Russell MW, Muste JC, Kuo BL, Wu AK, Singh RP. Clinical trials targeting the gut-microbiome to effect ocular health: a systematic review. Eye (Lond). 2023;37:2877-2885. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Erdem B, Kaya Y, Kıran TR, Yılmaz S. An Association Between the Intestinal Permeability Biomarker Zonulin and the Development of Diabetic Retinopathy in Type II Diabetes Mellitus. Turk J Ophthalmol. 2023;53:91-96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Wei Y, Gong J, Zhu W, Guo D, Gu L, Li N, Li J. Fecal microbiota transplantation restores dysbiosis in patients with methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus enterocolitis. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15:265. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Xiao W, Su J, Gao X, Yang H, Weng R, Ni W, Gu Y. The microbiota-gut-brain axis participates in chronic cerebral hypoperfusion by disrupting the metabolism of short-chain fatty acids. Microbiome. 2022;10:62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 177] [Article Influence: 44.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Zhao Z, Ning J, Bao XQ, Shang M, Ma J, Li G, Zhang D. Fecal microbiota transplantation protects rotenone-induced Parkinson's disease mice via suppressing inflammation mediated by the lipopolysaccharide-TLR4 signaling pathway through the microbiota-gut-brain axis. Microbiome. 2021;9:226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 408] [Article Influence: 81.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Gunardi TH, Susantono DP, Victor AA, Sitompul R. Atopobiosis and Dysbiosis in Ocular Diseases: Is Fecal Microbiota Transplant and Probiotics a Promising Solution? J Ophthalmic Vis Res. 2021;16:631-643. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Choi RY, Asquith M, Rosenbaum JT. Fecal transplants in spondyloarthritis and uveitis: ready for a clinical trial? Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2018;30:303-309. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Baldi S, Mundula T, Nannini G, Amedei A. Microbiota shaping - the effects of probiotics, prebiotics, and fecal microbiota transplant on cognitive functions: A systematic review. World J Gastroenterol. 2021;27:6715-6732. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 38. | Jayasudha R, Kalyana Chakravarthy S, Sai Prashanthi G, Sharma S, Tyagi M, Shivaji S. Implicating Dysbiosis of the Gut Fungal Microbiome in Uveitis, an Inflammatory Disease of the Eye. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2019;60:1384-1393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Kalyana Chakravarthy S, Jayasudha R, Sai Prashanthi G, Ali MH, Sharma S, Tyagi M, Shivaji S. Dysbiosis in the Gut Bacterial Microbiome of Patients with Uveitis, an Inflammatory Disease of the Eye. Indian J Microbiol. 2018;58:457-469. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 142] [Article Influence: 17.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Huang X, Ye Z, Cao Q, Su G, Wang Q, Deng J, Zhou C, Kijlstra A, Yang P. Gut Microbiota Composition and Fecal Metabolic Phenotype in Patients With Acute Anterior Uveitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2018;59:1523-1531. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Morandi SC, Herzog EL, Munk M, Kreuzer M, Largiadèr CR, Wolf S, Zinkernagel M, Zysset-Burri DC. The gut microbiome and HLA-B27-associated anterior uveitis: a case-control study. J Neuroinflammation. 2024;21:120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Wang Q, Wu S, Ye X, Tan S, Huang F, Su G, Kijlstra A, Yang P. Gut microbial signatures and their functions in Behcet's uveitis and Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease. J Autoimmun. 2023;137:103055. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Ye Z, Wu C, Zhang N, Du L, Cao Q, Huang X, Tang J, Wang Q, Li F, Zhou C, Xu Q, Xiong X, Kijlstra A, Qin N, Yang P. Altered gut microbiome composition in patients with Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease. Gut Microbes. 2020;11:539-555. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Tecer D, Gogus F, Kalkanci A, Erdogan M, Hasanreisoglu M, Ergin Ç, Karakan T, Kozan R, Coban S, Diker KS. Succinivibrionaceae is dominant family in fecal microbiota of Behçet's Syndrome patients with uveitis. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0241691. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Kim JC, Park MJ, Park S, Lee ES. Alteration of the Fecal but Not Salivary Microbiome in Patients with Behçet's Disease According to Disease Activity Shift. Microorganisms. 2021;9:1449. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Yasar Bilge NS, Pérez Brocal V, Kasifoglu T, Bilge U, Kasifoglu N, Moya A, Dinleyici EC. Intestinal microbiota composition of patients with Behçet's disease: differences between eye, mucocutaneous and vascular involvement. The Rheuma-BIOTA study. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2020;38 Suppl 127:60-68. [PubMed] |

| 47. | Ye Z, Zhang N, Wu C, Zhang X, Wang Q, Huang X, Du L, Cao Q, Tang J, Zhou C, Hou S, He Y, Xu Q, Xiong X, Kijlstra A, Qin N, Yang P. A metagenomic study of the gut microbiome in Behcet's disease. Microbiome. 2018;6:135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 195] [Article Influence: 24.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Zysset-Burri DC, Keller I, Berger LE, Neyer PJ, Steuer C, Wolf S, Zinkernagel MS. Retinal artery occlusion is associated with compositional and functional shifts in the gut microbiome and altered trimethylamine-N-oxide levels. Sci Rep. 2019;9:15303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Zhang Y, Wang T, Wan Z, Bai J, Xue Y, Dai R, Wang M, Peng Q. Alterations of the intestinal microbiota in age-related macular degeneration. Front Microbiol. 2023;14:1069325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Zysset-Burri DC, Keller I, Berger LE, Largiadèr CR, Wittwer M, Wolf S, Zinkernagel MS. Associations of the intestinal microbiome with the complement system in neovascular age-related macular degeneration. NPJ Genom Med. 2020;5:34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Xue W, Peng P, Wen X, Meng H, Qin Y, Deng T, Guo S, Chen T, Li X, Liang J, Zhang F, Xie Z, Jin M, Liang Q, Wei L. Metagenomic Sequencing Analysis Identifies Cross-Cohort Gut Microbial Signatures Associated With Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2023;64:11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Huang Y, Wang Z, Ma H, Ji S, Chen Z, Cui Z, Chen J, Tang S. Dysbiosis and Implication of the Gut Microbiota in Diabetic Retinopathy. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2021;11:646348. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 24.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Moubayed NM, Bhat RS, Al Farraj D, Dihani NA, El Ansary A, Fahmy RM. Screening and identification of gut anaerobes (Bacteroidetes) from human diabetic stool samples with and without retinopathy in comparison to control subjects. Microb Pathog. 2019;129:88-92. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Ye P, Zhang X, Xu Y, Xu J, Song X, Yao K. Alterations of the Gut Microbiome and Metabolome in Patients With Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy. Front Microbiol. 2021;12:667632. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Das T, Jayasudha R, Chakravarthy S, Prashanthi GS, Bhargava A, Tyagi M, Rani PK, Pappuru RR, Sharma S, Shivaji S. Alterations in the gut bacterial microbiome in people with type 2 diabetes mellitus and diabetic retinopathy. Sci Rep. 2021;11:2738. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 24.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Jayasudha R, Das T, Kalyana Chakravarthy S, Sai Prashanthi G, Bhargava A, Tyagi M, Rani PK, Pappuru RR, Shivaji S. Gut mycobiomes are altered in people with type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Diabetic Retinopathy. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0243077. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 12.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Khan R, Sharma A, Ravikumar R, Parekh A, Srinivasan R, George RJ, Raman R. Association Between Gut Microbial Abundance and Sight-Threatening Diabetic Retinopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2021;62:19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Omar WEW, Singh G, McBain AJ, Cruickshank F, Radhakrishnan H. Gut Microbiota Profiles in Myopes and Nonmyopes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2024;65:2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Sun Y, Xie Y, Li J, Hou X, Sha Y, Bai S, Yu H, Liu Y, Wang G. Study on the relationship between adolescent myopia and gut microbiota via 16S rRNA sequencing. Exp Eye Res. 2024;247:110067. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Skondra D, Rodriguez SH, Sharma A, Gilbert J, Andrews B, Claud EC. The early gut microbiome could protect against severe retinopathy of prematurity. J AAPOS. 2020;24:236-238. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Chang YH, Yeh YM, Lee CC, Chiu CH, Chen HC, Hsueh YJ, Lee CW, Lien R, Chu SM, Chiang MC, Kang EY, Chen KJ, Wang NK, Liu L, Hwang YS, Lai CC, Wu WC. Neonatal gut microbiota profile and the association with retinopathy of prematurity in preterm infants. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2025;53:54-66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Berkowitz E, Kopelman Y, Kadosh D, Carasso S, Tiosano B, Kesler A, Geva-Zatorsky N. "More Guts Than Brains?"-The Role of Gut Microbiota in Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension. J Neuroophthalmol. 2022;42:e70-e77. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Gong H, Zhang S, Li Q, Zuo C, Gao X, Zheng B, Lin M. Gut microbiota compositional profile and serum metabolic phenotype in patients with primary open-angle glaucoma. Exp Eye Res. 2020;191:107921. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Kalyana Chakravarthy S, Jayasudha R, Ranjith K, Dutta A, Pinna NK, Mande SS, Sharma S, Garg P, Murthy SI, Shivaji S. Alterations in the gut bacterial microbiome in fungal Keratitis patients. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0199640. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Jayasudha R, Chakravarthy SK, Prashanthi GS, Sharma S, Garg P, Murthy SI, Shivaji S. Alterations in gut bacterial and fungal microbiomes are associated with bacterial Keratitis, an inflammatory disease of the human eye. J Biosci. 2018;43:835-856. [PubMed] |

| 66. | Mendez R, Watane A, Farhangi M, Cavuoto KM, Leith T, Budree S, Galor A, Banerjee S. Gut microbial dysbiosis in individuals with Sjögren's syndrome. Microb Cell Fact. 2020;19:90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Moon J, Choi SH, Yoon CH, Kim MK. Gut dysbiosis is prevailing in Sjögren's syndrome and is related to dry eye severity. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0229029. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 20.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Watane A, Cavuoto KM, Rojas M, Dermer H, Day JO, Banerjee S, Galor A. Fecal Microbial Transplant in Individuals With Immune-Mediated Dry Eye. Am J Ophthalmol. 2022;233:90-100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Filippelli M, dell'Omo R, Amoruso A, Paiano I, Pane M, Napolitano P, Bartollino S, Costagliola C. Intestinal microbiome: a new target for chalaziosis treatment in children? Eur J Pediatr. 2021;180:1293-1298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Filippelli M, dell'Omo R, Amoruso A, Paiano I, Pane M, Napolitano P, Campagna G, Bartollino S, Costagliola C. Effectiveness of oral probiotics supplementation in the treatment of adult small chalazion. Int J Ophthalmol. 2022;15:40-44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 71. | Yang W, Xu X, Xie R, Lin J, Hou Z, Xin Z, Cao X, Shi T. Tryptophan metabolites exert potential therapeutic activity in graves' orbitopathy by ameliorating orbital fibroblasts inflammation and proliferation. J Endocrinol Invest. 2025;48:1781-1795. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Zhang X, Dong K, Zhang X, Kang Z, Sun B. Exploring gut microbiota and metabolite alterations in patients with thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy using high-throughput sequencing and untargeted metabolomics. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2024;15:1413890. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Zhang Q, Tong B, Xie Z, Li Y, Li Y, Wang L, Luo B, Qi X. Changes in the gut microbiota of patients with Graves' orbitopathy according to severity grade. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2023;51:808-821. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Bu Y, Chan YK, Wong HL, Poon SH, Lo AC, Shih KC, Tong L. A Review of the Impact of Alterations in Gut Microbiome on the Immunopathogenesis of Ocular Diseases. J Clin Med. 2021;10:4694. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Lu LJ, Liu J. Human Microbiota and Ophthalmic Disease. Yale J Biol Med. 2016;89:325-330. [PubMed] |

| 76. | Dong Q, Brulc JM, Iovieno A, Bates B, Garoutte A, Miller D, Revanna KV, Gao X, Antonopoulos DA, Slepak VZ, Shestopalov VI. Diversity of bacteria at healthy human conjunctiva. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:5408-5413. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 217] [Cited by in RCA: 286] [Article Influence: 19.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Panek M, Čipčić Paljetak H, Barešić A, Perić M, Matijašić M, Lojkić I, Vranešić Bender D, Krznarić Ž, Verbanac D. Methodology challenges in studying human gut microbiota - effects of collection, storage, DNA extraction and next generation sequencing technologies. Sci Rep. 2018;8:5143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 17.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Cani PD. Human gut microbiome: hopes, threats and promises. Gut. 2018;67:1716-1725. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 821] [Cited by in RCA: 990] [Article Influence: 123.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Napolitano P, Filippelli M, D'andrea L, Carosielli M, dell'Omo R, Costagliola C. Probiotic Supplementation Improved Acute Anterior Uveitis of 3-Year Duration: A Case Report. Am J Case Rep. 2021;22:e931321. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Kosiewicz MM, Dryden GW, Chhabra A, Alard P. Relationship between gut microbiota and development of T cell associated disease. FEBS Lett. 2014;588:4195-4206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |