Published online Sep 22, 2025. doi: 10.4291/wjgp.v16.i3.107573

Revised: April 30, 2025

Accepted: July 3, 2025

Published online: September 22, 2025

Processing time: 177 Days and 15.7 Hours

Fatigue is a prevalent and often debilitating symptom in individuals with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), affecting a substantial proportion of patients, even during periods of disease remission. The prevalence of fatigue in IBD remains high, affecting around half of the IBD patients and being more common in pa

Core Tip: Fatigue is a prevalent and debilitating symptom in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), affecting nearly half of all patients and three-fourths with active disease. Its origins are multifactorial, involving inflammation, nutritional deficiencies, sleep issues, psychological factors, gut microbiota, muscle dysfunction, and inactivity. Identifying and addressing these factors is key to management. The IBD fatigue and functional assessment in chronic illness therapy - fatigue scales are common assessment tools for adults, with PedsQL for pediatric patients. Management involves physical exercise, medical or surgical management of active disease, correcting nutritional deficiencies, and addressing psychological and sleep disorders. Persistent fatigue may require physical and psychological interventions through a multidisciplinary approach.

- Citation: Giri S, Harindranath S, Kulkarni A, Sahoo JK, Joshi H, Nath P, Sahu MK. Fatigue in inflammatory bowel disease: Prevalence, risk factors, assessment, outcomes, and management. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol 2025; 16(3): 107573

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2150-5330/full/v16/i3/107573.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4291/wjgp.v16.i3.107573

Fatigue is conventionally defined as “a sense of continuing tiredness with periods of sudden and overwhelming lack of energy that interferes with the performance of daily activities and is not sufficiently improved with adequate rest”[1]. Nevertheless, due to its multidimensional character, a simplistic description may fail to encompass the complexities of fatigue. Markowitz et al[2] reported three components of fatigue: The perception of generalized weakness, characterized by an inability or difficulty in initiating activities; rapid fatigability and diminished capacity to sustain activities; and mental fatigue, leading to challenges in concentration, emotional stability, and memory. Fatigue is linked to several chronic inflammatory disorders, including inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), rheumatoid arthritis, and multiple sclerosis, resulting in a detrimental effect on quality of life (QoL). It is one of the most prevalent and disabling symptoms affecting patients with IBD, contributing substantially to the illness burden as well as healthcare costs[3].

Fatigue in IBD is often multifactorial, involving factors like nutritional deficiencies and anemia, though it can occur independently of these as well[3,4]. As definitions of health and disease evolve, there is increasing recognition of subjective symptoms that persist beyond the resolution of inflammation and disease activity. Fatigue is an often underrecognized entity in the context of IBD, silently contributing to the poor QoL of patients[4]. In this review, we summarize the current evidence on fatigue in IBD, including prevalence, predictive factors, methods of assessment, and management strategies. Based on the findings from the included studies, we aim to propose a systematic approach to evaluating and managing fatigue in patients with IBD.

Fatigue is one of the most prevalent and disabling symptoms in patients with IBD, as reported by an initial systematic review, affecting 86% of patients with active disease and 41%-48% of those with clinically quiescent disease[5]. It poses a significant burden regarding poor health-related QoL and cost to patients and the healthcare system. Multiple studies have reported on the prevalence of fatigue in patients with IBD, with the majority of the publications being in the last 5 years, indicating an increasing interest in studying fatigue in the context of IBD[6].

One of the earliest studies by Minderhoud et al[7] found that approximately 40% of patients with IBD in clinical remission suffered from fatigue, a figure comparable to patients with cancer. In a prospective study by Villoria et al[8] of 202 patients with IBD [28% ulcerative colitis (UC); 72% Crohn’s disease (CD)] in remission, fatigue was present in 54% of the population. A population-based study explored fatigue in 440 patients with IBD over two decades, compared to a control group of 2287 Norwegians aged 19-80 years, randomly selected from the general population by the Norwegian Government Computer Centre. Chronic fatigue occurred in a significantly higher proportion of patients with IBD (21% of UC; 25% of CD) than in the general population (11%). In addition, active disease was associated with increased fatigue rates (38% for both UC and CD) compared to disease remission (16% for UC, 20% for CD). The study also reported that fatigue was more prevalent among women compared to men (28% vs 17%)[9]. A higher prevalence of anemia, with higher levels of psychiatric comorbidities among women with IBD, may explain this gender disparity[9]. Another population-based study in the Manitoba IBD cohort estimated the prevalence of fatigue to be 72% in those with active disease and 30% with inactive disease[10]. Earlier literature posits that fatigue may reflect the cumulative effect of long-standing disease. However, in a study by Cohen et al[11] in 220 patients with newly diagnosed IBD, fatigue was present in 26.4% of patients, challenging this hypothesis.

In a recent meta-analysis of 20 studies, the reported prevalence of fatigue in IBD varied from 24% to 87%. The pooled prevalence (n = 20 studies) of fatigue in IBD was 47% [95% confidence interval (CI): 41%–54%] with significant heterogeneity[6]. Based on disease activity, the prevalence was higher in those with active disease (n = 6 studies) compared to those in remission (n = 7 studies) (72%, 95%CI: 59%–85% vs 47%, 95%CI: 36%–57%). The pooled prevalence for CD (n = 10 studies) was 42% (95%CI: 35%–50%), while the pooled prevalence for UC (n = 11 studies) was 36% (95%CI: 30%–42%)[6]. In a systematic review of pediatric studies, the pooled prevalence of fatigue in pediatric patients with IBD varied from 8% to 75%, with fatigue being associated with disease activity[12]. Thus, there is a high prevalence of fatigue in both pediatric and adult patients with IBD. Patients with CD are reported to have a higher prevalence of fatigue compared to UC. CD often presents with more severe and fluctuating disease activity compared to UC, which can contribute to higher fatigue levels. Also, patients with CD frequently experience more extensive bowel involvement and complications, including anemia, leading to an increased prevalence of fatigue[3,6]. However, the limitations with prevalence estimates are the significant heterogeneity due to differing definitions and assessment methods used, and not accounting for confounding factors (anemia, malnutrition, fibromyalgia etc.) by most of the studies.

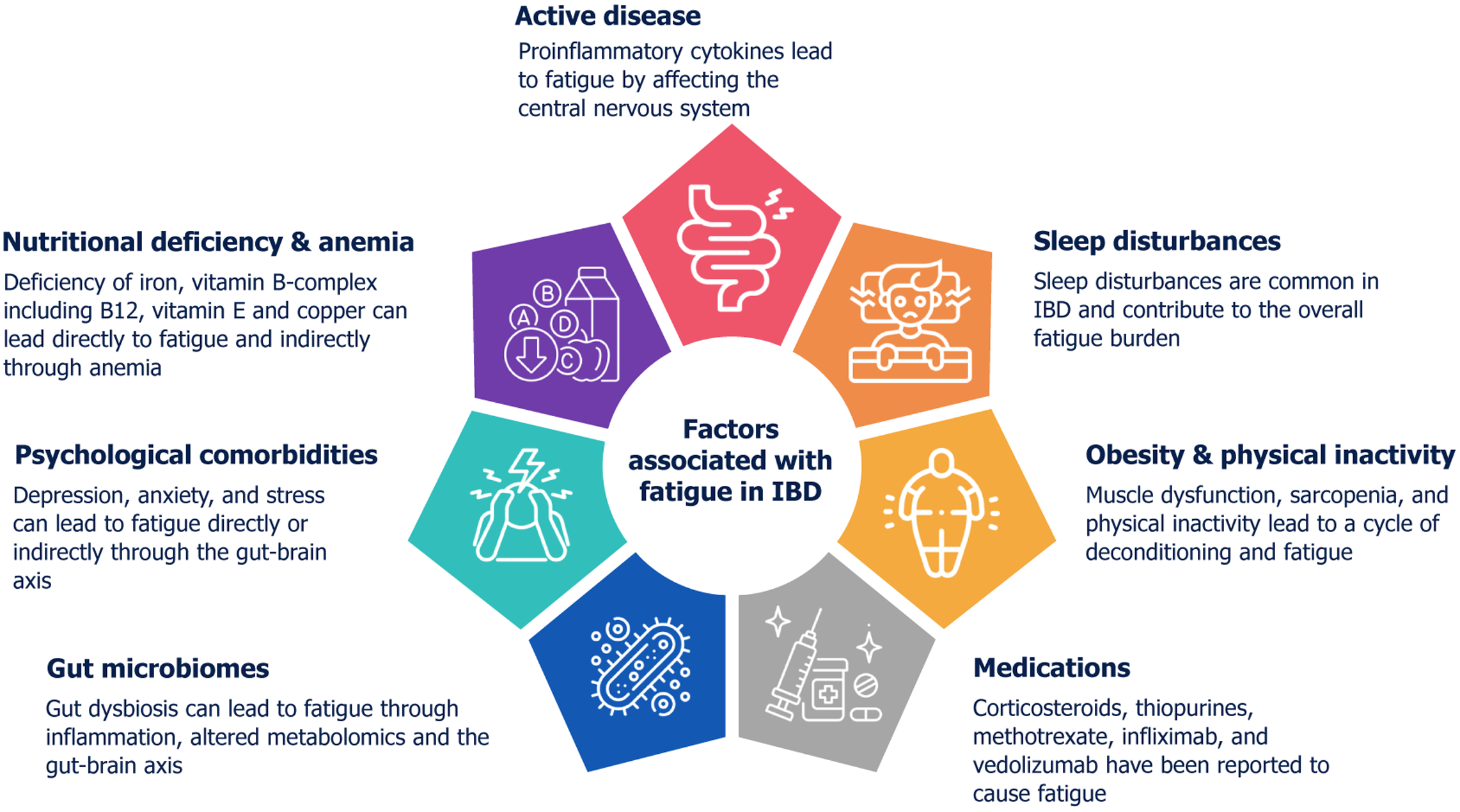

Fatigue in IBD is multifactorial, and multiple mechanisms can be at play simultaneously (Figure 1).

IBD is characterized by chronic inflammation in the gastrointestinal tract, which can trigger a systemic inflammatory response. This systemic inflammation involves the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin (IL)-1, and IL-6. These cytokines can cross the blood-brain barrier and affect the central nervous system, leading to various symptoms, including fatigue[3,4]. They can disrupt neurotransmitter balance, influence sleep patterns, and alter energy metabolism, all of which contribute to feelings of fatigue[3,4]. Active disease has been reported to have a higher prevalence of fatigue; thus, control of the disease remains an important therapeutic approach for managing fatigue in IBD.

While addressing inflammation is crucial, many patients continue to experience fatigue even during remission. In the study by Casellas et al[13], including patients with mucosal healing, fatigue was seen in the subset of patients without normalization of health-related quality of life (HRQOL). This indicates that factors other than inflammation may also play a significant role in this complex symptom. Vogelaar et al[14] compared the expression of various cytokines in stimulated whole blood and serum samples of patients with IBD in remission with and without fatigue. They reported an increase in levels of TNF-α (P = 0.022) and interferon (IFN)-γ (P = 0.047) in the fatigue group. The serum levels of IL-12 (P < 0.001) and IL-10 (P = 0.005) were also significantly higher in the fatigue group compared with the non-fatigue group[13]. The study by Kvivik et al[15] highlighted that high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) and other biomolecules, like IL-1 receptor antagonist and heat shock protein 90 alpha (HSP90α), significantly impact fatigue severity, emphasizing the interconnectedness of inflammation and fatigue in chronic conditions. Another study in pediatric patients with sub-clinical IBD reported that patients with insulin-like growth factor 1 Z scores in the lowest quartile had significantly more fatigue and a significantly higher serum level of IL-10, IL-17A, IL-6, and IFN-γ[16]. One study reported elevated levels of fecal calprotectin were more frequent in patients with fatigue compared to those without (32.4% vs 10.6%; P = 0.006 in UC; 9.5% vs 1.3%; P = 0.035 in CD), while another reported no such association[17,18]. This suggests that biomarkers for inflammation may not always help predict fatigue. Chronic subclinical inflammation contributes to increased fatigue, even in those with remission. Whether escalating treatment to address this subclinical inflammation will improve fatigue remains a topic of future research.

Micronutrient deficiencies play a significant role in the manifestation of fatigue among patients with IBD. Micronutrient deficiencies can occur in patients with IBD as a result of several factors, including impaired absorption, diarrhea, self-imposed dietary restrictions, or a catabolic state. These deficiencies can exacerbate fatigue by impairing metabolic pro

Vitamin deficiency: Deficiencies in B vitamins, particularly thiamine (B1), have been implicated in the development of fatigue in IBD patients. Thiamine is essential for energy metabolism, and its deficiency can lead to decreased energy production and increased fatigue[19]. Vitamin E deficiency can also lead to muscle weakness, further exacerbating fatigue symptoms in IBD patients[20]. As the terminal ileum is the site of absorption of B12, patients with IBD are at risk for B12 deficiency due to either the disease process or surgical resection. Vitamin B12 deficiency is common in patients with CD, while folate deficiency is uncommon. However, either deficiency can lead to fatigue in IBD, even in the absence of anemia[20]. Vitamin D deficiency is common in patients with IBD and is associated with disease activity. However, a definite association of vitamin D deficiency with fatigue in IBD has not been reported. A study from Norway of 405 patients with IBD reported no association between total fatigue score and chronic fatigue with vitamin D deficiency[21].

Mineral deficiency: Iron deficiency is the most common micronutrient deficiency in IBD and is closely linked to fatigue. Iron is crucial for hemoglobin production, and its deficiency can lead to anemia, a direct cause of fatigue. However, Bager et al[22] reported no association of fatigue with anemia or iron deficiency. Another study from Canada reported no evidence of an association between iron deficiency and fatigue in the absence of anemia, suggesting that iron deficiency is not a clinically relevant contributor to fatigue in IBD[23]. Studies have shown mixed results regarding the impact of iron deficiency without anemia on fatigue, but iron replacement therapy is recommended to alleviate fatigue in iron-deficient patients[24]. Copper deficiency is associated with anemia and muscle weakness, both of which contribute to fatigue[20]. Thus, testing for and replacing deficient nutrients and ensuring a nutritionally replete diet, generally in collaboration with an experienced dietician, could improve symptoms, although data are limited.

Sleep plays a critical role in the experience of fatigue among patients with IBD. IBD patients have poor sleep quality, which may be related to active disease, leading to abdominal pain and nocturnal passage of stool. Psychological comor

IBD patients manifest significant mental health comorbidities, with reported lifetime diagnoses of 30% for anxiety, 40% for depression, and 48.1% for diminished QoL, which can exacerbate fatigue symptoms[28]. While the therapeutic impact of depression and anxiety management on IBD-associated fatigue is still unknown, the substantial prevalence of these comorbidities highlights the necessity for routine clinical screening. In a study by Banovic et al[29], increased disease activity correlated with heightened depressive symptoms, which subsequently led to greater fatigue. While anxiety was prevalent, it did not significantly mediate fatigue levels. Additionally, emotional processing deficits were observed in patients with active disease, further contributing to fatigue[29], In a path analysis model, Davis et al[30] reported a direct effect of both anxiety and depression on fatigue. Additionally, significant indirect effects were observed, where de

The gut microbiome plays a significant role in fatigue experienced by individuals with IBD through several potential mechanisms, primarily mediated by the gut-brain axis.

Gut dysbiosis and inflammation: IBD is often characterized by gut dysbiosis, an imbalance in the gut microbiota com

Production of short-chain fatty acids: Several studies suggest that lower abundances of short-chain fatty acids (SCFA)-producing bacteria are associated with fatigue in IBD[34,36,37]. SCFAs, such as butyrate, are produced by the gut micro

Gut-brain axis communication: The bidirectional communication between the gut microbiome and the central nervous system (the gut-brain axis) is increasingly recognized as a key factor in mediating fatigue in IBD[3,40]. The gut microbiota can influence the brain through various mechanisms, including direct interaction with the immune system (via cytokines), altering the hypo

In summary, the gut microbiome plays a significant and multifaceted role in the development and persistence of fatigue in IBD. Imbalances in the microbial community, alterations in metabolic functions, and communication through the gut-brain axis are all implicated in this complex symptom. Further research is needed to fully elucidate these mecha

Malnutrition, a frequently under-recognized complication of IBD, affects a substantial proportion of patients, ranging from 20% to 85%[41]. Depletion of adipose and muscle reserves, coupled with micronutrient deficiencies, has been implicated in fatigue within the general population. However, similar data for patients with IBD are limited, and studies evaluating the effects of nutritional interventions on fatigue outcomes in IBD are conspicuously absent.

Sarcopenia is common in IBD, affecting up to one-fifth of the patients, with more than one-third having myopenia and pre-sarcopenia[42]. It leads to reduced muscle mass and strength, contributing to fatigue and poor disease outcomes[43]. Inflammation and gut dysbiosis in IBD promote a low-grade inflammatory state, which can upregulate several molecular pathways leading to muscle failure. This is part of the 'gut-muscle axis' hypothesis, where gut microbiota alterations affect muscle function, leading to fatigue[44,45]. Physical inactivity, often due to fear of exacerbating symptoms, further compounds these issues, leading to a cycle of deconditioning and fatigue.

Assessing these risk factors is important as it helps in understanding their contributions to developing fatigue. Furthermore, from a therapeutic perspective, they help in providing hard end-points to target with interventions. Clini

The fundamental problem with the assessment of fatigue in patients with IBD is that the symptom is subjective and can be perceived differently, not only by different patients but also by the same individual at two different times, depending on their disease activity. The fact that multiple medications (corticosteroids, cyclosporine, tacrolimus) can also cause muscle weakness and interfere with the perception of fatigue adds to the complexity. Some authors have provided a definition of fatigue[46,47]. The other factor complicating the redressal of this problem is the lack of recognition of this entity among clinicians as a contributor to the low QoL. Fatigue is often overlooked as it is a part & parcel of the disease. In a patient-focused questionnaire-based study of fatigue in IBD, patients reported having asked their clinicians for a treatment for fatigue and were not impressed by the efforts taken in that direction[48]. Another issue with this subjectively expressed symptom is that it has not been assessed in a uniformly quantifiable manner. The QoL in patients with IBD has been assessed with validated questionnaires such as IBD-Q[49]. However, even in this widely utilized questionnaire, only two questions are dedicated to fatigue.

A substantial number of questionnaires have been developed and validated to assess fatigue in chronic illnesses. However, only a few of these questionnaires have been used for fatigue assessment in IBD, and not all are validated (Table 1)[49-74]. Tinsley et al[50] validated the functional assessment in chronic illness therapy - fatigue (FACIT-F), which is a fatigue-oriented component of the wider FACIT questionnaire, originally used for cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. The first attempt to validate a dedicated inflammatory bowel disease fatigue (IBD-F) questionnaire came from the United States[58]. The IBD-F correlated well with the Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI) and the Multidimensional Assessment of Fatigue (MAF) scale in the validation phase and had good test-retest stability[58]. Another group from Spain tried to correlate the IBD activity and the scoring of three fatigue questionnaires: Daily Fatigue Impact Scale (DFIS), Modified Fatigue Impact Scale, and Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS) to assess the accuracy of fatigue assessment[56]. The three questionnaires correlate well with the QoL as assessed by the IBD-Q and showed an acceptable correlation among themselves for quantifying fatigue. Of these, DFIS showed the greatest correlation with clinical activity and QoL of patients. Norton et al[59] compared IBD-F, MFI, and MAF and reported similar performance of the three scores. Another questionnaire validated in IBD patients is the PROMIS-SF-7a questionnaire[69]. Since these questionnaires can be time-consuming and cannot eliminate subjectivity, there is currently no ideal questionnaire that has been recommended to assess fatigue in IBD.

| Scales for fatigue assessment used in patients with IBD | Validated in IBD |

| Functional assessment of chronic illness therapy-fatigue[49-55] | Yes |

| Daily fatigue impact scale[56,57] | Yes |

| Modified fatigue impact scale[56,57] | Yes |

| Fatigue severity scale[56] | Yes |

| Inflammatory bowel disease fatigue scale[58-63] | Yes |

| Multidimensional fatigue inventory[58,59,64-67] | Yes |

| Patient-reported outcomes measurement information system® fatigue short form 7a (SF-7a) scale[68,69]1 | Yes |

| Multidimensional assessment of fatigue[58,59] | No |

| Fatigue questionnaire[66,70,71] | No |

| Brief fatigue inventory[64] | No |

| PedsQLTM multidimensional fatigue scale[72,73]1 | Yes |

| Multidimensional fatigue scale[74]1 | No |

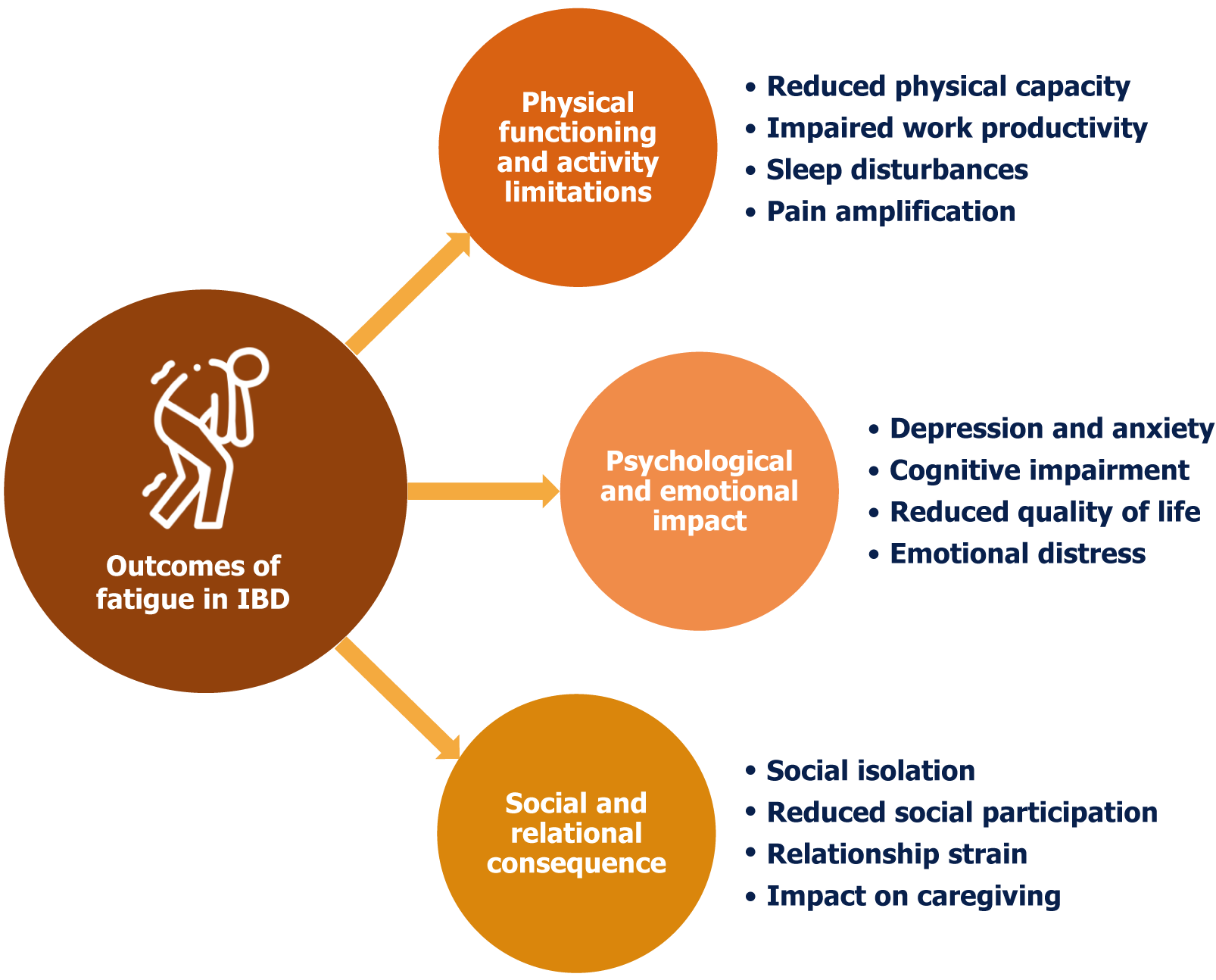

Fatigue is a pervasive and debilitating symptom experienced by a significant proportion of individuals with IBD. Unlike the transient tiredness experienced by healthy individuals, IBD-related fatigue is often described as overwhelming, persistent, and disproportionate to physical activity. It significantly impacts QoL, affecting various aspects of daily functioning, emotional well-being, and social participation. Understanding the multifaceted outcomes of fatigue in IBD (Figure 2) is crucial for developing effective management strategies and improving patient outcomes.

Reduced physical capacity: Fatigue directly translates to reduced physical capacity, hindering individuals from engaging in routine activities. Simple tasks, such as grocery shopping, household chores, or even climbing stairs, can become in

Impaired work productivity: For those in the workforce, fatigue can significantly impact work performance. Jobs that require physical exertion can be particularly challenging for individuals experiencing fatigue. Even seemingly minor physical tasks can become overwhelming. Reduced concentration, difficulty maintaining focus, and decreased stamina can lead to absenteeism, presenteeism (being present but unproductive), and, ultimately, job loss[75,77].

Sleep disturbances: The relationship between fatigue and sleep in IBD is complex and often bidirectional. IBD-related inflammation and discomfort can disrupt sleep patterns, leading to poor sleep quality and exacerbating fatigue. Conversely, fatigue can lead to difficulty falling asleep or staying asleep, contributing to insomnia. The sheer exhaustion can also cause periods of excessive daytime sleepiness, further disrupting nighttime sleep. Thus, fatigue and poor sleep in IBD create a cycle where each exacerbates the other, leading to a significant impact on an individual's daily life[78-80].

Pain amplification: Chronic fatigue can contribute to a state of central sensitization, where the central nervous system becomes hypersensitive to pain signals. Fatigue often coexists with psychological distress, such as anxiety and depre

Depression and anxiety: Co-existent fatigue has been reported with depression and anxiety in IBD patients. A fatigued person will have a reduced ability to cope with stress and emotional challenges. This can make them more susceptible to anxiety and depression. The constant struggle with fatigue and its impact on daily life can lead to feelings of hope

Cognitive impairment: People with IBD show significant deficits in attention, executive function, and working memory compared to healthy controls[85]. Fatigue can impair cognitive function, affecting concentration, memory, and decision-making. This "brain fog" can further contribute to feelings of frustration and inadequacy, impacting work performance and social interactions[86].

Reduced quality of life: The impact of fatigue on QoL is subjective and can vary significantly between individuals. The cumulative effect of physical limitations, psychological distress, and cognitive impairment significantly reduces QoL[41]. Individuals with IBD and severe fatigue may experience a diminished sense of well-being, reduced social engagement, and a decreased ability to enjoy life[87]. Both in patients with CD and UC, fatigue is a predictor of health-related QoL, independent of disease activity or anemia[88].

Emotional distress: The constant feeling of being tired, even after adequate rest, creates a sense of emotional distress. This may manifest as irritability, frustration, and a general feeling of being overwhelmed. The emotional burden of fatigue can strain relationships and contribute to social isolation[89].

Social isolation and reduced social participation: Fatigue can lead to social isolation as individuals withdraw from social activities due to a lack of energy and motivation. Participation in hobbies, recreational activities, and community events can decrease drastically. This loss of social engagement can further exacerbate feelings of loneliness and depression[75,90].

Relationship strain: Fatigue can strain relationships with family, friends, and partners. The inability to participate in social activities or fulfill responsibilities can lead to misunderstandings and resentment. Partners may feel burdened by the increased responsibilities, while individuals with IBD may feel guilty or inadequate[91]. Fatigue may adversely affect sexual well-being and intimacy in people with IBD, rendering sexual closeness overwhelming[92].

Impact on caregiving: For individuals with IBD who are caregivers, fatigue can significantly impact their ability to pro

Almost 10%-25% of adult IBD patients have their onset before 18 years of age, with the most severe form of the disease seen in this age group[94]. Children often complain of fatigue, but this is mostly overlooked in regular follow-ups[95,96]. Pediatric IBD (PIBD), like other chronic childhood illnesses, has a profound negative impact on QoL, affecting physical, emotional, cognitive, and social functioning, leading to disabling fatigue despite opting for standard treatment options[96]. Factors like lack of inquiry regarding fatigue during routine follow-up visits, lack of a pediatric-specific tool to measure it, and failure of research studies to consider it as an outcome result in under-reporting of fatigue in PIBD[12]. A systematic review reported that fatigue decreased physical activity, and sleep problems were more common in PIBD than their healthy peers. Active disease causes nocturnal pain in the abdomen and diarrhea, which impairs sleep. Inflammation, along with immune activation, causes glial cells and mitochondrial damage, leading to decreased ATP production, which adds up to fatigue[96]. A similar association had also been shown in other studies, where 92% of those with active disease had fatigue as compared to 63% in the remission group (P = 0.01)[12].

A recent study from China showed that fatigue in IBD is significantly influenced by region, age, disease severity and use of corticosteroids and biological agents (P < 0.05), where gender, source of medical expenses, disease course, disease type, immunosuppressants, enteral nutrition and per capita income had no significant effect on experiencing fatigue (P > 0.05)[74]. Other studies also didn’t show any relation with puberty stages, socio-economic status, and BMI[12,68,72,96]. But Grossman et al[68] reported lesser anxiety and fatigue among Blacks/African Americans than whites, (40.7 vs 47.5, P = 0.001) and (44.3 vs 48.4, P = 0.047) respectively using PROMIS score.

Patient outcomes in IBD typically focus on disease activity scores, but it is important also to consider the child’s perception of the disease and its impact on his/her daily functioning[73]. However, like the adult population, there are limited metrics for assessment fatigue in PIBD with variability. First is the PROMIS score, which had multiple domains, including anxiety, depression, fatigue, peer relationships and pain interference[68]. However, this score is not validated in pediatric population.

A cross-sectional study using the PedsQL Multidimensional Fatigue Scale in PIBD found a higher prevalence of fatigue and lower HRQOL in PIBD compared to control subjects[72]. Another study from Romania using PedsQL reported similar findings. The relation between PedsQL Multidimensional Fatigue Scale scores and CDI: S scores (r = -0.43, P < 0.0001) suggested a direct relationship between fatigue and depressive symptoms. Sleep was significantly affected in children with IBD as compared to controls[73]. Using the IMPACT III questionnaire response, Turner et al[12] showed that 78% and 11% of children with PIBD had moderate and severe fatigue, respectively, whereas 9% of healthy controls had only moderate fatigue (P = 0.007). 90% of the cases in the same study had experienced some degree of fatigue by 4 months of treatment induction[12]. Brenner et al[97] showed that a change in PROMIS score was associated with changes in IMPACT III scores (r = -0.59). Hence, similar to adults, there are no recommended scores for assessment of fatigue in PIBD, requiring future research in this aspect.

The treatment of fatigue in PIBD is the same as in adult patients, with normalized QoL and absence of disability as long-term targets of treatment of IBD. Apart from pharmacotherapy, lifestyle modifications like regular physical activity, limiting screen time, practicing a healthy sleep schedule, a balanced/high protein diet, and family affection are required to support and motivate the children.

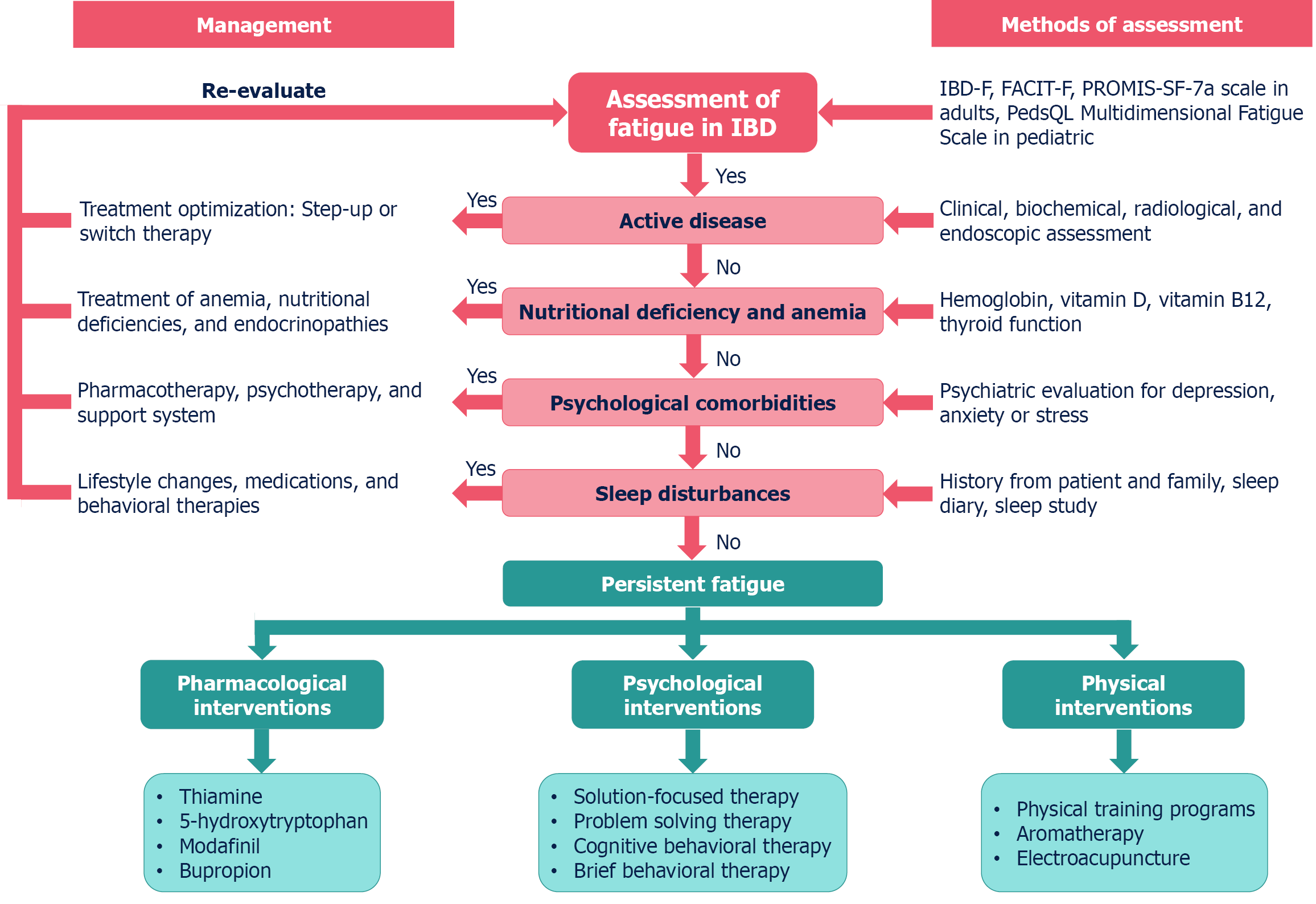

Fatigue is a prevalent and debilitating symptom for individuals with IBD, impacting their QoL, work productivity, and social functioning. It is experienced by a significant proportion of IBD patients, even during periods of disease remission. Given the complex and multifactorial nature of IBD-related fatigue, a comprehensive, multidisciplinary approach that addresses various contributing factors is often recommended. Table 2 summarizes the current available literature for the management of fatigue in IBD[95,98-122]. The treatment approaches can be broadly categorized into:

| Ref. | Country, study design, No. of patients | Patient characteristics and number | Intervention | Outcome |

| Pharmacotherapy for control of disease activity | ||||

| Grimstad et al[98], 2016 | Norway, prospective, n = 82 (UC: 100%) | Treatment-naïve adult patients with active UC | Conventional treatment with 5-aminosalicylate ± corticosteroid or azathioprine | Median fVAS reduced from 40 (0-94) to 22 (0-81) (P < 0.001) over 3 months, with the prevalence of significant fatigues (fVAS ≥ 50) reduced from 40.2% to 20.7% |

| Bączyk et al[99], 2019 | Poland, prospective, n = 60 (UC: 50%, CD: 50%) | Patients with active IBD | Surgical treatment for IBD | There was a significant reduction in the fatigue score after surgery in both patients with UC and CD, with improvement in systemic and social function |

| Danese et al[100], 2023 | Multicentric, RCT (UC: 100%) | Patients with moderate to severe active UC | UPA induction (45 mg) for 8 weeks, followed by maintenance (30 mg or 15 mg) for 52 weeks | A reduction of ≥ 5 points in the FACIT-F score was higher in the UPA group both at 8 weeks (59.1% vs 33.8% with placebo) and 52 weeks (UPA 30 mg: 58.8% vs UPA 15 mg: 55.4% vs placebo: 35.1%) |

| Ghosh et al[101], 2024 | Multicentric, RCT, n = 1021 (CD: 100%) | Patients with moderate to severe active CD | UPA induction (45 mg) for 8 weeks, followed by maintenance (30 mg or 15 mg) for 52 weeks | FACIT-F score was higher in the UPA group both at 8 weeks (42% vs 27% with placebo in U-EXCEL and 42.3% vs 20% with placebo in U-EXCEED) and 52 weeks (UPA 30 mg: 43.3% vs UPA 15 mg: 28.4% vs placebo: 16.9%) |

| Regueiro et al[102], 2024 | Multicentric, RCT, n = 191 (CD: 100%) | Patients with moderate to severe active CD | Mirikizumab | At 12 weeks, mirikizumab groups reported improved FACIT-F scores compared with placebo, and improvement was maintained through week 52 and week 104 |

| Other pharmacotherapies | ||||

| Costantini and Pala[103], 2013 | Italy, prospective, single-arm, n = 12 (UC: 75%, CD: 25%) | Patients in remission with moderate to severe fatigue as per CFS scale | Thiamine started at 600 mg/day and increased by 300 mg every two days if no improvement | In 10/12 (83.3%) patients, the values of the CFS scale after therapy were equal to zero, suggesting complete improvement. Two other patients had 50% and 66.6% regression from baseline score |

| Scholten et al[104], 2018 | The Netherlands, RCT, n = 39 (UC: 49%, CD: 51%) | Fatigue duration > 3 months with a high score (≥ 35) on the fatigue subscale of CIS score and not on corticosteroids | 8-weeks period treatment with 1000 μg vitamin B12 | Scores on the CIS subscale ‘motivation’ improved, but no significant improvement was observed in the overall score and subscale ‘subjective fatigue’ |

| Bager et al[105], 2021 | Denmark, RCT, n = 40 (UC: 50%, CD: 50%) | Patients in remission with chronic fatigue (IBD-Fatigue score > 12 and duration > 6 months) | Weight and gender-based high-dose oral thiamine ranging from 600-1800 mg/d for 4 weeks | Significant decrease in fatigue score and health-related quality of life from baseline, and a significantly higher proportion of patients showed improvement with thiamine compared to placebo |

| Moradi et al[106], 2021 | Iran, RCT, n = 80 (UC: 100%) | Active mild-to-moderate UC | 500 mg capsule of Spirulina, twice daily for eight weeks | There was no difference between the two groups in terms of fatigue score, nor there was any improvement from the baseline score |

| Bager et al[107], 2022 | Denmark, RCT, n = 40 (UC: 50%, CD: 50%) | Patients in remission with chronic fatigue (IBD-Fatigue score > 12 & duration > 6 months) recruited from the previous trial | Maintenance dose oral thiamine 300 mg/d for 12 weeks followed by self-treatment with over-the-counter thiamine × 6 m | No beneficial effect of thiamine for 12 weeks on fatigue. Patients who took OTC thiamine had lower level of fatigue at 52 weeks (7.8; 5.5–10.1) compared to no thiamine (11.0; 9.2–12.8) (P = 0.02) |

| Truyens et al[108], 2022 | Belgium, RCT, n = 166 (UC: 28%, CD: 72%) | Patients in remission for > 3 months with fVAS score ≥ 5 | 8-week treatment of HTP orally 100 mg twice daily | The proportion of patients achieving ≥ 20% reduction and a mean reduction in fVAS was comparable between 5-HTP and placebo |

| Bager et al[109], 2023 | Denmark, RCT, n = 40 (UC: 50%, CD: 50%) | Adult patients with quiescent, IBD and chronic fatigue (IBD-F score > 12) | Weight and gender-based high-dose oral thiamine ranging from 600-1800 mg/day for 4 weeks | Reduction in the fatigue score by ≥ 3 points was observed in 65% (26/40) patients |

| Moulton et al[110], 2024 | United Kingdom, prospective case series, n = 10 (UC: 20% CD: 80%) | Patients with quiescent or mildly active disease and severe fatigue (IBD fatigue assessment scale score ≥ 11) | Modafinil 100 mg twice a day and gradually increased to 200 mg twice a day based on response | There was an improvement in the mean score by 58.1% from the baseline, with 60% reporting ≥ 50% improvement from the baseline score |

| Psychological interventions | ||||

| Vogelaar et al[111], 2011 | The Netherlands, RCT, n = 29 | A high score on the fatigue scale (CIS score ≥ 35) and in clinical remission | Psychological interventions, including PST and SFT | Improvement in fatigue score was observed in 85.7% and 60% of SFT and PST groups, respectively, compared to 45.5% in controls. Medical costs lowered in 57.1% of the patients in the SFT group, 45.5% in the control group and 20% in the PST group |

| Vogelaar et al[112], 2014 | The Netherlands, RCT, n = 98 (UC: 41%, CD: 59%) | A high score on the fatigue scale (CIS score ≥ 35) and in clinical remission | SFT vs CAU | 39% of patients in the SFT group achieved a CIS-fatigue score < 35 after treatment, compared to 18% in the CAU group (P = 0.03). Although SFT significantly reduced fatigue and improved QoL at 3 and 6 months, these benefits diminished by 9 months |

| Artom et al[113], 2019 | United Kingdom, RCT, n = 31 (UC: 22.6%, CD: 67.7%) | Patients in remission with self-reported fatigue | CBT: One 60-minute & seven 30-minute sessions over 8-weeks | There was more reduction in the impact of fatigue than the severity of fatigue at 6 months with CBT, with improvement in quality-of-life scores |

| O’Connor et al[114], 2019 | United Kingdom, RCT, n = 29 (UC: 13% CD: 87%) | Patients in remission with score ≥ 1 on Section I of the Crohn’s and Colitis. United Kingdom IBD fatigue self-assessment scale | Psychoeducational intervention: Delivered in small groups for 1 hour every 8 weeks over a period of 6 months | Mean fatigue severity and impact scores improved for patients in the intervention group and worsened in the control group |

| Hashash et al[115], 2022 | United States, RCT, n = 52 (100% CD) | Biopsy-proven, young (15-30 years) CD patients with PSQI ≥ 7 and Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI) ≥ 4 | Sequential brief behavioral therapy for sleep followed by bupropion for those not improving | There was a significant improvement in fatigue following 4 weeks of behavioral therapy. Adding bupropion improved fatigue further, but was not statistically significant |

| Strobel et al[116], 2022 | United States, retrospective, n = 19 (UC: 21%, CD: 79%) | Patients with controlled, but persistent, symptoms | Functional medicine program, including dietary advice: 2-hour sessions alternate weeks for 10 weeks | There was a significant improvement in the median score of the FSS from 43 (27-53.5) to 27 (18-45). 73% (11) of the 15 patients who completed the follow-up had improvement in FSS score |

| Regev et al[117], 2023 | Israel, RCT, n = 120 (CD: 100%) | Confirmed diagnosis of CD for ≥ 1 year, with mild-to-moderate disease activity | Cognitive-behavioral and mindfulness based stress reduction with daily exercise | The intervention group demonstrated significantly lower levels of fatigue and the change in fatigue was independent of the changes in disease activity |

| Bredero et al[118], 2024 | The Netherlands, RCT, n = 108 (UC: 47%, CD: 53%) | Patients in remission with elevated levels of fatigue (CIS – subjective fatigue ≥ 27) | Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) for 8 weeks | Improvements in IBD-related fatigue following MBCT are maintained during a 9-month follow-up period, with about one-third of patients reporting clinically significant enhancement from pretreatment to follow-up |

| Physical intervention | ||||

| Horta et al[119], 2020 | Spain, RCT, n = 52 (UC: 11.5%, CD: 88.5%) | Patients in clinical remission with persistent fatigue (Two consecutive Functional FACIT-FS scores < 40) | Electroacupuncture: 2 sessions in the first week and then 1 per week for 7 weeks (Total 8 weeks) vs acupuncture vs none | Significant improvement in fatigue in both electroacupuncture and acupuncture groups from baseline. Fatigue improvement (≥ 3-point increase in FACIT-FS) seen in 86.6%, 66.6%, & 8.3% of electroacupuncture, acupuncture, & none group fatigue remission (FACIT-FS > 40) observed in 27.7%, 11.1%, & 0% of electroacupuncture, acupuncture, & none group |

| van Erp et al[120], 2021 | The Netherlands, prospective, n = 25 (UC: 16%, CD: 84%) | Fatigue duration > 3 months with a high score (≥ 35) on the fatigue subscale of CIS score and in clinical remission | Personalized exercise program (aerobic + resistance based on cardiopulmonary exercise test) of three training sessions per week for 12 consecutive weeks | There was a significant reduction in the total CIS score and severity of fatigue (CIS-F score), with the scores remaining unchanged in only one patient. There was a significant improvement in the health-related quality of life as assessed by IBD questionnaire |

| Lamers et al[121], 2022 | The Netherlands, prospective, n = 25 (UC: 54%, CD: 46%) | Patients with a diagnosis of IBD for > 2 years with mild active disease or in remission | Personalized dietary and physical activity advice in 6 consults | Significant decrease in mean IBD-F from baseline at 3 months (P = 0.002) and 6 months (P = 0.008), but not at 1 month (P = 0.07) |

| You et al[122], 2022 | China, RCT, n = 70 (UC: 63%, CD: 37%) | Patients with fatigue and quiescent or mildly active disease and receiving stable medication | Aromatherapy through the skin and by inhalation: 30 minutes × 3 times a week | There was no difference between the two groups based on the Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory score, but there was significant improvement in sub-dimensions of physical and mental fatigue |

| Scheffers et al[95], 2023 | The Netherlands, RCT, n = 15 (UC: 33.3%, CD: 66.7%) | Pediatric patients aged 6-8 years with a diagnosis of IBD | 12-week lifestyle program (3 physical training sessions per week plus personalized healthy dietary advice) | Significant reduction in disease activity, fecal calprotectin and fatigue and improvement in quality of life |

Since disease activity is a known contributor to fatigue, induction of disease remission is a primary step in managing fatigue in IBD.

Conventional drug treatment: Improvements in fatigue at 3 months of follow-up have been observed with conventional drug treatment, including 5-aminosalicylate ± corticosteroid or azathioprine for UC, possibly due to the overall effect of being in a treatment setting or as a result of alleviating disease symptoms[98].

Biologicals and small molecules: Some studies suggest that anti-TNF-α agents may reduce fatigue in CD, potentially due to a reduction in disease activity or through direct effects on fatigue signaling mechanisms. A study on the trajectory of fatigue in IBD, which included a majority of the patients in remission, reported no effect of anti-TNF on the fatigue trajectory[123]. Longitudinal studies have indicated that biologic therapies improve fatigue in IBD patients with active disease. Upadacitinib has been reported to significantly reduce fatigue both during induction and maintenance, as assessed by the FACIT-F score. This improvement is more marked in patients with UC (59.1% vs 33.8% with placebo at 8 weeks) than CD (42% vs 27% with placebo in U-EXCEL and 42.3% vs 20% with placebo in U-EXCEED trial at 8 weeks)[100,101]. Similarly, the use of mirikizumab improved fatigue in patients with moderate to severe active CD at 12 weeks, with improvements sustained to week 104[102].

Surgical treatment: The severity of fatigue in IBD correlates with the disease activity. Surgical treatment can significantly reduce fatigue symptoms in IBD patients, particularly when the disease is resistant to medical management. In a study by Bączyk et al[99], there was a significant reduction in the fatigue score after surgery in both patients with active UC and CD, with improvement in systemic and social function.

Cognitive behavioral therapy: Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is a viable option for improving fatigue and QoL in IBD patients by targeting cognitions, emotions, and behaviors related to fatigue. In a pilot study by Artom et al[113], patients received one 60-minute and seven 30-minute telephone sessions weekly with a therapist over 8-weeks. The authors reported a greater reduction in the impact of fatigue than the severity of fatigue at 6 months with CBT, with improvement in quality-of-life scores[113]. In a recent RCT, Regev et al[117] assessed the utility of cognitive-behavioral and mindfulness-based stress reduction with daily exercise in patients with mild-to-moderate CD. The intervention group demonstrated significantly lower levels of fatigue and the change in fatigue was independent of the changes in disease activity[117]. In a survey of IBD patients, respondants preferred CBT over other psychological interventions for fatigue[124]. This highlights the potential of a brief, structured, multidisciplinary program of psychological support in improving fatigue, mood, and QoL in patients with quiescent IBD.

Problem-solving therapy: Problem-solving therapy (PST) is designed to enhance patients' capacities to manage the daily stressors associated with IBD. This consequently enhances the overall QoL and mitigates the adverse effects of psychological and physical ailments. In a previous study, PST improved fatigue in 60% of the patients with quiescent IBD compared to 45.5% in the control group, although it was not statistically significant. The QoL also showed improvement in 60% of the patients compared to baseline[111].

Solution-focused therapy: Solution-focused therapy (SFT) is a brief psychological intervention based on the solution-focused model of solving problems. SFT has demonstrated effectiveness in reducing fatigue in IBD patients and has shown significant beneficial effects on fatigue severity lasting up to 6 months. In the first study evaluating the role of psychological interventions in IBD, PST improved fatigue in 85.7% of the patients with quiescent IBD compared to 60% with PST and 45.5% in the control group. The QoL also showed improvement in 71.4% of the patients compared to baseline[111]. In a subsequent RCT, it was found that 39% of patients in the SFT group had a fatigue score below 35, compared to 18% in the usual care group, and the SFT group showed a greater reduction in fatigue across the first six months. However, at the end of 9 months, no significant differences were observed between the groups, suggesting a loss of response over follow-up[112].

Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy: While mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) and CBT aim to improve mental health, the key difference lies in their approach to managing thoughts: MBCT focuses on accepting and detaching from thoughts through mindfulness practices, while CBT actively challenges and changes negative thought patterns to create more positive ones. MBCT has been shown to effectively reduce fatigue in IBD patients in remission, with effects maintained over a nine-month follow-up period[118].

Brief behavioral therapy: This brief, targeted therapy empowers participants to manage their insomnia symptoms. One study explored the effect of brief behavioral therapy and bupropion on sleep and fatigue in adolescents and young adults with IBD. The study reported the benefits of this intervention in patients with insomnia and fatigue[115].

Treating or correcting anemia, iron deficiency, or vitamin deficiencies (B12, folate, vitamin D) may help reduce fatigue.

Thiamine supplementation: Some studies suggest that fatigue in IBD may be a manifestation of mild intracellular thiamine deficiency, and high-dose thiamine supplementation has shown promise in reducing fatigue. One study found that 10 out of 12 patients experienced complete regression of fatigue after treatment with high-dose thiamine (started at 600 mg/day and increased by 300 mg every two days if there was no improvement)[103]. Another study confirmed a significant beneficial effect of high-dose thiamine (ranging from 600-1800 mg/day for 4 weeks) in chronic fatigue in IBD[105]. However, a study using 300 mg of thiamine daily for 12 weeks did not maintain the achieved levels of fatigue, and no significant effect was found[107]. Also, high-dose thiamine may result in tachycardia. Administering high dosages of thiamine (1200–1500 mg/day) at night may induce sleep disturbances. To mitigate the occurrence of this effect, thiamine should be administered before evening.

Vitamin B12 supplementation: One study aimed to determine the effect of high-dose oral vitamin B12 supplementation (1000 μg/day) on fatigue. Scores on the CIS subscale ‘motivation’ improved, but no significant improvement was observed in the overall score and subscale ‘subjective fatigue’[104].

Physical exercise: Physical exercise has been shown to improve fatigue in IBD patients, as well as improve aerobic capacity and muscle strength. One study found that fatigued IBD patients have impaired physical fitness and are less physically active[75]. van Erp et al[120] analyzed the role of a personalized exercise program (aerobic + resistance based on a cardiopulmonary exercise test of 3 training sessions/week for 12 weeks) in patients with IBD in remission and fatigue. There was a significant reduction in the total CIS score and severity of fatigue (CIS-F score), with the scores remaining unchanged in only one patient[121]. Scheffers et al[95] used a 12-week lifestyle program (3 physical training sessions per week plus personalized healthy dietary advice) in pediatric patients with IBD and reported a significant reduction in disease activity, fecal calprotectin and fatigue and improvement in QoL. Thus, patients with IBD should be advised to exercise regularly to alleviate fatigue and improve their overall QoL.

Aromatherapy: Aromatherapy has been shown to be a potentially effective method of relieving fatigue and sleep problems. A study using aromatherapy through the skin and by inhalation over 30 minutes and 3 times a week showed no difference between the treatment and placebo groups based on the Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory score, but there was a significant improvement in sub-dimensions of physical and mental fatigue[122].

Sleep interventions: Poor sleep quality has been reported to be an independent predictor of the progression of fatigue over time[26]. Addressing sleep disturbances with behavioral interventions may be helpful in managing fatigue[115].

Modafinil: Modafinil is a medication that enhances dopamine neurotransmission, resulting in a stimulant effect. Mod

Bupropion: Bupropion, a dopamine and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor, may be considered in the management of fatigue in IBD. Bupropion, a noradrenaline and dopamine reuptake inhibitor, may be particularly promising in IBD because it marginally slows gut motility, reduces tumor necrosis factor concentrations, may improve fatigue and is the only antidepressant that improves sexual function[125]. In a study, adding bupropion in those not responding to sequential brief behavioral therapy improved fatigue further but was not statistically significant[115].

Online self-management tools are being developed to help IBD patients manage fatigue, pain, and urgency/incontinence. These tools can assist with symptom tracking, medication management, and activity tracking[31]. A patient-centered, multidisciplinary approach to fatigue, including gastroenterology, psychology, and occupational therapy, is more likely to provide comprehensive benefits to patients.

Based on the findings of the present review, we present a step-wise approach to the diagnosis and management of fatigue in IBD (Figure 3).

Despite the progress in understanding and managing IBD-related fatigue, several challenges remain. First, there is a lack of consistent definitions and assessment tools for fatigue, which makes it difficult to compare findings across studies. Second, the multifactorial nature of fatigue requires interventions that target multiple areas to achieve meaningful improvement. Third, the evidence base for the effectiveness of many interventions for IBD-related fatigue is limited, requiring more high-quality, well-powered studies. Lastly, the long-term effectiveness of some interventions for managing fatigue in IBD patients needs further research.

In conclusion, managing fatigue in IBD is a complex and challenging task, requiring a comprehensive and multidisciplinary approach. While there is no one-size-fits-all solution, combining disease management with psychological support, lifestyle changes, nutritional interventions, and, in some cases, pharmacological treatments holds promise for improving the lives of individuals with IBD who experience debilitating fatigue. Continued research and a greater awareness of this symptom among healthcare providers are essential to achieving better outcomes for these patients.

| 1. | Billones R, Liwang JK, Butler K, Graves L, Saligan LN. Dissecting the fatigue experience: A scoping review of fatigue definitions, dimensions, and measures in non-oncologic medical conditions. Brain Behav Immun Health. 2021;15:100266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 15.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Markowitz AJ, Rabow MW. Palliative management of fatigue at the close of life: "it feels like my body is just worn out". JAMA. 2007;298:217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Borren NZ, van der Woude CJ, Ananthakrishnan AN. Fatigue in IBD: epidemiology, pathophysiology and management. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16:247-259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 184] [Article Influence: 26.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Nocerino A, Nguyen A, Agrawal M, Mone A, Lakhani K, Swaminath A. Fatigue in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: Etiologies and Management. Adv Ther. 2020;37:97-112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | van Langenberg DR, Gibson PR. Systematic review: fatigue in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:131-143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 180] [Cited by in RCA: 177] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | D'Silva A, Fox DE, Nasser Y, Vallance JK, Quinn RR, Ronksley PE, Raman M. Prevalence and Risk Factors for Fatigue in Adults With Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Systematic Review With Meta-Analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20:995-1009.e7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 21.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Minderhoud IM, Oldenburg B, van Dam PS, van Berge Henegouwen GP. High prevalence of fatigue in quiescent inflammatory bowel disease is not related to adrenocortical insufficiency. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1088-1093. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Villoria A, García V, Dosal A, Moreno L, Montserrat A, Figuerola A, Horta D, Calvet X, Ramírez-Lázaro MJ. Fatigue in out-patients with inflammatory bowel disease: Prevalence and predictive factors. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0181435. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Huppertz-Hauss G, Høivik ML, Jelsness-Jørgensen LP, Opheim R, Henriksen M, Høie O, Hovde Ø, Kempski-Monstad I, Solberg IC, Jahnsen J, Hoff G, Moum B, Bernklev T. Fatigue in a population-based cohort of patients with inflammatory bowel disease 20 years after diagnosis: The IBSEN study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2017;52:351-358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Graff LA, Vincent N, Walker JR, Clara I, Carr R, Ediger J, Miller N, Rogala L, Rawsthorne P, Lix L, Bernstein CN. A population-based study of fatigue and sleep difficulties in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:1882-1889. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 186] [Cited by in RCA: 234] [Article Influence: 15.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Cohen BL, Zoëga H, Shah SA, Leleiko N, Lidofsky S, Bright R, Flowers N, Law M, Moniz H, Merrick M, Sands BE. Fatigue is highly associated with poor health-related quality of life, disability and depression in newly-diagnosed patients with inflammatory bowel disease, independent of disease activity. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39:811-822. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Turner ST, Focht G, Orlanski-Meyer E, Lev-Tzion R, Ledder O, Yogev D, Assa A, Shaoul R, Crowely E, Otley A, Griffiths AM, Turner D. Fatigue in pediatric inflammatory bowel diseases: A systematic review and a single center experience. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2024;78:241-251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Casellas F, Barreiro de Acosta M, Iglesias M, Robles V, Nos P, Aguas M, Riestra S, de Francisco R, Papo M, Borruel N. Mucosal healing restores normal health and quality of life in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;24:762-769. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Vogelaar L, de Haar C, Aerts BR, Peppelenbosch MP, Timman R, Hanssen BE, van der Woude CJ. Fatigue in patients with inflammatory bowel disease is associated with distinct differences in immune parameters. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2017;10:83-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kvivik I, Grimstad T, Bårdsen K, Jonsson G, Kvaløy JT, Omdal R. High mobility group box 1 and a network of other biomolecules influence fatigue in patients with Crohn's disease. Mol Med. 2023;29:81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Lucia Casadonte CJ, Brown J, Strople J, Neighbors K, Fei L, Alonso EM. Low Insulin-like Growth Factor-1 Influences Fatigue and Quality of Life in Children With Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2018;67:616-621. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Gibble TH, Shan M, Zhou X, Naegeli AN, Dubey S, Lewis JD. Association of fatigue with disease activity and clinical manifestations in patients with Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis: an observational cross-sectional study in the United States. Curr Med Res Opin. 2024;40:1537-1544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Uhlir V, Stallmach A, Grunert PC. Fatigue in patients with inflammatory bowel disease-strongly influenced by depression and not identifiable through laboratory testing: a cross-sectional survey study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2023;23:288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Jayawardena D, Dudeja PK. Micronutrient Deficiency in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: Cause or Effect? Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;9:707-708. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kamel AY, Johnson ZD, Hernandez I, Nguyen C, Rolfe M, Joseph T, Dixit D, Shen S, Chaudhry N, Pham A, Rampertab SD, Zimmermann E. Micronutrient deficiencies in inflammatory bowel disease: an incidence analysis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024;36:1186-1192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Frigstad SO, Høivik ML, Jahnsen J, Cvancarova M, Grimstad T, Berset IP, Huppertz-Hauss G, Hovde Ø, Bernklev T, Moum B, Jelsness-Jørgensen LP. Fatigue is not associated with vitamin D deficiency in inflammatory bowel disease patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24:3293-3301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Bager P, Befrits R, Wikman O, Lindgren S, Moum B, Hjortswang H, Hjollund NH, Dahlerup JF. Fatigue in out-patients with inflammatory bowel disease is common and multifactorial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35:133-141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Goldenberg BA, Graff LA, Clara I, Zarychanski R, Walker JR, Carr R, Rogala L, Miller N, Bernstein CN. Is iron deficiency in the absence of anemia associated with fatigue in inflammatory bowel disease? Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:1392-1397. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Sartain S, Al-Ezairej M, McDonnell M, Westoby C, Katarachia V, Wootton SA, Cummings JRF. Iron deficiency and fatigue in inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic review. PLoS One. 2025;20:e0304293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Guadagnoli L, Horrigan J, Walentynowicz M, Salwen-Deremer JK. Sleep Quality Drives Next Day Pain and Fatigue in Adults With Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Short Report. J Crohns Colitis. 2024;18:171-174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 26. | Hashash JG, Ramos-Rivers C, Youk A, Chiu WK, Duff K, Regueiro M, Binion DG, Koutroubakis I, Vachon A, Benhayon D, Dunn MA, Szigethy EM. Quality of Sleep and Coexistent Psychopathology Have Significant Impact on Fatigue Burden in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2018;52:423-430. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Kamp KJ, Yoo L, Clark-Snustad K, Winders S, Burr R, Buchanan D, Barahimi M, Jacobs J, Heitkemper M, Lee SD. Relationship of Sleep Health and Endoscopic Disease Activity in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Endoscopic Disease Activity and Sleep. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2023;46:465-474. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Lewis K, Marrie RA, Bernstein CN, Graff LA, Patten SB, Sareen J, Fisk JD, Bolton JM; CIHR Team in Defining the Burden and Managing the Effects of Immune-Mediated Inflammatory Disease. The Prevalence and Risk Factors of Undiagnosed Depression and Anxiety Disorders Among Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019;25:1674-1680. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Banovic I, Montreuil L, Derrey-Bunel M, Scrima F, Savoye G, Beaugerie L, Gay MC. Toward Further Understanding of Crohn's Disease-Related Fatigue: The Role of Depression and Emotional Processing. Front Psychol. 2020;11:703. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Davis SP, Chen DG, Crane PB, Bolin LP, Johnson LA, Long MD. Influencing Factors of Inflammatory Bowel Disease-Fatigue: A Path Analysis Model. Nurs Res. 2021;70:256-265. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Konturek PC, Brzozowski T, Konturek SJ. Stress and the gut: pathophysiology, clinical consequences, diagnostic approach and treatment options. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2011;62:591-599. [PubMed] |

| 32. | Bonaz BL, Bernstein CN. Brain-gut interactions in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:36-49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 423] [Cited by in RCA: 514] [Article Influence: 39.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Overman EL, Rivier JE, Moeser AJ. CRF induces intestinal epithelial barrier injury via the release of mast cell proteases and TNF-α. PLoS One. 2012;7:e39935. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 177] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 34. | Santana PT, Rosas SLB, Ribeiro BE, Marinho Y, de Souza HSP. Dysbiosis in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Pathogenic Role and Potential Therapeutic Targets. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 180] [Cited by in RCA: 217] [Article Influence: 54.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 35. | Missaghi B, Barkema HW, Madsen KL, Ghosh S. Perturbation of the human microbiome as a contributor to inflammatory bowel disease. Pathogens. 2014;3:510-527. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Sartor RB. Microbial influences in inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:577-594. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1339] [Cited by in RCA: 1399] [Article Influence: 77.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 37. | Glassner KL, Abraham BP, Quigley EMM. The microbiome and inflammatory bowel disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;145:16-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 222] [Cited by in RCA: 631] [Article Influence: 105.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 38. | Guo C, Che X, Briese T, Ranjan A, Allicock O, Yates RA, Cheng A, March D, Hornig M, Komaroff AL, Levine S, Bateman L, Vernon SD, Klimas NG, Montoya JG, Peterson DL, Lipkin WI, Williams BL. Deficient butyrate-producing capacity in the gut microbiome is associated with bacterial network disturbances and fatigue symptoms in ME/CFS. Cell Host Microbe. 2023;31:288-304.e8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 34.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Morell Miranda P, Bertolini F, Kadarmideen HN. Investigation of gut microbiome association with inflammatory bowel disease and depression: a machine learning approach. F1000Res. 2019;7:702. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Truyens M, Lernout H, De Vos M, Laukens D, Lobaton T. Unraveling the fatigue puzzle: insights into the pathogenesis and management of IBD-related fatigue including the role of the gut-brain axis. Front Med (Lausanne). 2024;11:1424926. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Goh J, O'Morain CA. Review article: nutrition and adult inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:307-320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 192] [Cited by in RCA: 170] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Tasson L, Zingone F, Barberio B, Valentini R, Ballotta P, Ford AC, Scarpa M, Angriman I, Fassan M, Savarino E. Sarcopenia, severe anxiety and increased C-reactive protein are associated with severe fatigue in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Sci Rep. 2021;11:15251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 43. | Fatani H, Olaru A, Stevenson R, Alharazi W, Jafer A, Atherton P, Brook M, Moran G. Systematic review of sarcopenia in inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Nutr. 2023;42:1276-1291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Picca A, Ponziani FR, Calvani R, Marini F, Biancolillo A, Coelho-Junior HJ, Gervasoni J, Primiano A, Putignani L, Del Chierico F, Reddel S, Gasbarrini A, Landi F, Bernabei R, Marzetti E. Gut Microbial, Inflammatory and Metabolic Signatures in Older People with Physical Frailty and Sarcopenia: Results from the BIOSPHERE Study. Nutrients. 2019;12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 139] [Article Influence: 19.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Nardone OM, de Sire R, Petito V, Testa A, Villani G, Scaldaferri F, Castiglione F. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases and Sarcopenia: The Role of Inflammation and Gut Microbiota in the Development of Muscle Failure. Front Immunol. 2021;12:694217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 21.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Donovan KA, Jacobsen PB, Small BJ, Munster PN, Andrykowski MA. Identifying clinically meaningful fatigue with the Fatigue Symptom Inventory. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;36:480-487. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Barsevick AM, Cleeland CS, Manning DC, O'Mara AM, Reeve BB, Scott JA, Sloan JA; ASCPRO (Assessing Symptoms of Cancer Using Patient-Reported Outcomes). ASCPRO recommendations for the assessment of fatigue as an outcome in clinical trials. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;39:1086-1099. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Czuber-Dochan W, Dibley LB, Terry H, Ream E, Norton C. The experience of fatigue in people with inflammatory bowel disease: an exploratory study. J Adv Nurs. 2013;69:1987-1999. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Pallis AG, Mouzas IA, Vlachonikolis IG. The inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire: a review of its national validation studies. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2004;10:261-269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Tinsley A, Macklin EA, Korzenik JR, Sands BE. Validation of the functional assessment of chronic illness therapy-fatigue (FACIT-F) in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34:1328-1336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Saraiva S, Cortez-Pinto J, Barosa R, Castela J, Moleiro J, Rosa I, da Siva JP, Dias Pereira A. Evaluation of fatigue in inflammatory bowel disease - a useful tool in daily practice. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2019;54:465-470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Tiankanon K, Limsrivilai J, Poocharoenwanich N, Phaophu P, Subdee N, Kongtub N, Aniwan S. Burden of Inflammatory Bowel Disease on Patient Mood, Fatigue, Work, and Health-Related Quality of Life in Thailand: A Case-Control Study. Crohns Colitis 360. 2021;3:otab077. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Loftus EV Jr, Ananthakrishnan AN, Lee WJ, Gonzalez YS, Fitzgerald KA, Wallace K, Zhou W, Litcher-Kelly L, Ollis SB, Su S, Danese S. Content Validity and Psychometric Evaluation of the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue (FACIT-Fatigue) in Patients with Crohn's Disease and Ulcerative Colitis. Pharmacoecon Open. 2023;7:823-840. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Regueiro M, Delbecque L, Hunter T, Stassek L, Harding G, Lewis J. Experience and measurement of fatigue in adults with Crohn's disease: results from qualitative interviews and a longitudinal 2-week daily diary pilot study. J Patient Rep Outcomes. 2023;7:75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Regueiro M, Su S, Vadhariya A, Zhou X, Durand F, Stassek L, Kawata AK, Clucas C, Jairath V. Psychometric evaluation of the Functional Assessment of chronic illness therapy-fatigue (FACIT-Fatigue) in adults with moderately to severely active Crohn's disease. Qual Life Res. 2025;34:509-521. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Castillo-Cejas MD, Robles V, Borruel N, Torrejón A, Navarro E, Peláez A, Casellas F. Questionnaries for measuring fatigue and its impact on health perception in inflammatory bowel disease. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2013;105:144-153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Marrie RA, Fisk JD, Dolovich C, Lix LM, Graff LA, Patten SB, Bernstein CN. Psychometric Performance of Fatigue Scales in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2024;30:53-63. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Czuber-Dochan W, Norton C, Bassett P, Berliner S, Bredin F, Darvell M, Forbes A, Gay M, Nathan I, Ream E, Terry H. Development and psychometric testing of inflammatory bowel disease fatigue (IBD-F) patient self-assessment scale. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:1398-1406. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Norton C, Czuber-Dochan W, Bassett P, Berliner S, Bredin F, Darvell M, Forbes A, Gay M, Ream E, Terry H. Assessing fatigue in inflammatory bowel disease: comparison of three fatigue scales. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;42:203-211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Vestergaard C, Dahlerup JF, Bager P. Validation of the Danish version of Inflammatory Bowel Disease Self-assessment Scale. Dan Med J. 2017;64:A5394. [PubMed] |

| 61. | Lage AC, Oliveira CC, Batalha APDB, Araújo AF, Czuber-Dochan W, Chebli JMF, Cabral LA, Malaguti C. The inflammatory bowel disease-fatigue patient self-assessment scale: translation, cross-cultural adaptation and psychometric properties of the Brazilian Version (IBD-F Brazil). Arq Gastroenterol. 2020;57:50-63. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Liebert A, Wileńska A, Czuber-Dochan W, Kłopocka M. Translation and validation of the inflammatory bowel disease fatigue (IBD-F) patient self-assessment questionnaire. Prz Gastroenterol. 2021;16:136-143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Varbobitis I, Kokkotis G, Gizis M, Perlepe N, Laoudi E, Bletsa M, Bekiari D, Koutsounas I, Kounadis G, Xourafas V, Lagou S, Kolios G, Papakonstantinou I, Bamias G. The IBD-F Patient Self-Assessment Scale Accurately Depicts the Level of Fatigue and Predicts a Negative Effect on the Quality of Life of Patients With IBD in Clinical Remission. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2021;27:826-835. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Aluzaite K, Al-Mandhari R, Osborne H, Ho C, Williams M, Sullivan MM, Hobbs CE, Schultz M. Detailed Multi-Dimensional Assessment of Fatigue in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm Intest Dis. 2019;3:192-201. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Falling CL, Siegel CA, Salwen-Deremer JK. Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Pain Interference: A Conceptual Model for the Role of Insomnia, Fatigue, and Pain Catastrophizing. Crohns Colitis 360. 2022;4:otac028. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Jelsness-Jørgensen LP, Moum B, Grimstad T, Jahnsen J, Hovde Ø, Frigstad SO, Bernklev T. The multidimensional fatigue inventory (MFI-20): psychometrical testing in a Norwegian sample of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2022;57:683-689. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Lee HH, Gweon TG, Kang SG, Jung SH, Lee KM, Kang SB. Assessment of Fatigue and Associated Factors in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Questionnaire-Based Study. J Clin Med. 2023;12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Grossman A, Mauer E, Gerber LM, Long MD, Kappelman MD, Gupta N. Black/African American Patients with Pediatric Crohn's Disease Report Less Anxiety and Fatigue than White Patients. J Pediatr. 2020;225:146-151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Feagan BG, Sandborn WJ, Sands BE, Liu Y, Vetter M, Mathias SD, Huang KG, Johanns J, Germinaro M, Han C. Qualitative and psychometric evaluation of the PROMIS®-Fatigue SF-7a scale to assess fatigue in patients with moderately to severely active inflammatory bowel disease. J Patient Rep Outcomes. 2023;7:115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Holten KIA, Bernklev T, Opheim R, Johansen I, Olsen BC, Lund C, Strande V, Medhus AW, Perminow G, Bengtson MB, Cetinkaya RB, Vatn S, Frigstad SO, Aabrekk TB, Detlie TE, Hovde Ø, Kristensen VA, Småstuen MC, Henriksen M, Huppertz-Hauss G, Høivik ML, Jelsness-Jørgensen LP. Fatigue in Patients with Newly Diagnosed Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Results from a Prospective Inception Cohort, the IBSEN III Study. J Crohns Colitis. 2023;17:1781-1790. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Holten KA, Bernklev T, Opheim R, Olsen BC, Detlie TE, Strande V, Ricanek P, Boyar R, Bengtson MB, Aabrekk TB, Asak Ø, Frigstad SO, Kristensen VA, Hagen M, Henriksen M, Huppertz-Hauss G, Høivik ML, Jelsness-Jørgensen LP. Fatigue in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Remission One Year After Diagnosis (the IBSEN III Study). J Crohns Colitis. 2025;19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Marcus SB, Strople JA, Neighbors K, Weissberg-Benchell J, Nelson SP, Limbers C, Varni JW, Alonso EM. Fatigue and health-related quality of life in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:554-561. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Ioan A, Ionescu MI, Boboc C, Anghel M, Boboc AA, Cinteza EE, Galos F. Applicability of the PedsQLTM 4.0 Generic and Fatigue Modules in Romanian Children with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Pilot Study. Maedica (Bucur). 2023;18:607-614. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Zuo Y, Cao J, Wang Y, Cai W, Li M. Fatigue in children and adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease: a cross-sectional study. Front Pediatr. 2024;12:1519779. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Opheim R, Fagermoen MS, Bernklev T, Jelsness-Jorgensen LP, Moum B. Fatigue interference with daily living among patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Qual Life Res. 2014;23:707-717. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |