Published online May 28, 2025. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v17.i5.106333

Revised: April 9, 2025

Accepted: May 10, 2025

Published online: May 28, 2025

Processing time: 92 Days and 23.9 Hours

Chinese surgeons often rely on intraoperative exploration of the esophageal hiatus to determine the need for concurrent type I hiatal hernia (HH) repair during laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. However, no standardized criteria for the esophageal hiatus size or indications for exploration exist in China.

To investigate normal anatomical parameter ranges of the esophageal hiatus in patients with obesity.

A total of 158 patients, aged 20-49 years, was analyzed from January 2020 to June 2024. The patients were classified into the no reflux esophagitis (RE) no HH group (HHG), RE group, and type I HHG. The transverse and sagittal diameters and cross-sectional area of the esophageal hiatus were measured using multiplanar reconstruction of the computed tomography images.

Body mass index was positively correlated with area and transverse and sagittal diameters of the esophageal hiatus (r = 0.72, 0.69, and 0.54, respectively; P < 0.01). In the no RE no HHG and RE group, the esophageal hiatus size in the subgroup with obesity was greater than that in the non-obesity subgroup (area: 326.15 ± 78 mm2 vs 208.12 ± 64.44 mm2, transverse diameters: 15.97 ± 2.06 mm vs 13.37 ± 1.99 mm, sagittal diameters: 15.7 ± 2.08 mm vs 11.73 ± 2.08 mm; P < 0.01). Patients with obesity showed no significant differences in esophageal hiatus size with or without RE or HH.

The esophageal hiatus size increased with body mass index and was larger in patients with obesity than in those without obesity.

Core Tip: Given the lack of standardized criteria for esophageal hiatus size in patients with obesity, this retrospective case-control study found that esophageal hiatus size increased with body mass index and was larger in patients with obesity than without obesity. The esophageal hiatus area and transverse and sagittal diameters were 326.15 ± 78 mm2, 15.97 ± 2.06 mm, and 15.7 ± 2.08 mm, respectively. Patients with obesity with mild reflux esophagitis or type I hiatal hernia did not exhibit an enlarged esophageal hiatus. Thus, further computed tomography measurements of the esophageal hiatus could provide support for determining the need for intraoperative exploration.

- Citation: Qi Z, Shi XC, Yan WM, Bai RX. Association of esophageal hiatus size with reflux esophagitis and type I hiatal hernia in patients with obesity. World J Radiol 2025; 17(5): 106333

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8470/full/v17/i5/106333.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4329/wjr.v17.i5.106333

The obesity rate in China exceeds 16.4% and increases annually[1]. Obesity is a high-risk factor for reflux esophagitis (RE)[2] and hiatal hernia (HH), and the incidence of these two diseases increases with weight gain. Individuals with a body mass index (BMI) exceeding 30 kg/m2 have a four- to five-times higher risk of HH than normal weight individuals[3]. Weight loss can relieve the symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). A cross-sectional study reported that with a BMI decrease of 3.5 kg/m2, the risk of frequent GERD symptoms decreased by 40% (odds ratio = 0.64)[2]. Bariatric surgery is currently the most effective method for long-term weight control. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) accounts for nearly 60% of bariatric surgeries performed globally every year, and its proportion in China is high at 87%[4]. Chinese surgeons generally conduct esophageal hiatus exploration during LSG to diagnose concurrent type I HH and determine the need for HH repair based on the exploration results. However, standardized criteria or guidelines for esophageal hiatus size have not yet been established, which may lead to unnecessary esophageal hiatus exploration and even cause complications.

Because the esophageal hiatus presents a noncircular inclined structure, measuring its diameter in the horizontal direction by computed tomography (CT) cannot fully reflect its actual size. In 2016, Ouyang et al[5] proposed the pro

Thus, our study retrospectively analyzed the data of patients aged 20-49 years. MPR was applied to the CT images to comprehensively measure the cross-sectional area and transverse and sagittal diameters of the esophageal hiatus. Through a case-control study of patients with and without obesity, the normal anatomical parameter ranges of the esophageal hiatus in patients with obesity were derived to provide data support to determine the need for esophageal hiatus exploration during LSG.

A total of 158 patients who underwent gastroscopy and chest/abdominal CT between January 1, 2020 and June 1, 2024 were included in this study. The inclusion criteria were age 20-49 years with a BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 (obesity group) or BMI < 30 kg/m2 (non-obesity group). The exclusion criteria were gastrointestinal tumors, history of gastrointestinal surgery, achalasia, Mallory-Weiss syndrome, gastric fundal varices, severe organ dysfunction, abdominal aortic aneurysm, and skeletal dysplasia. The patients in the obesity and non-obesity groups were matched 1:1 or 1:2 based on age, height, weight, and medical history.

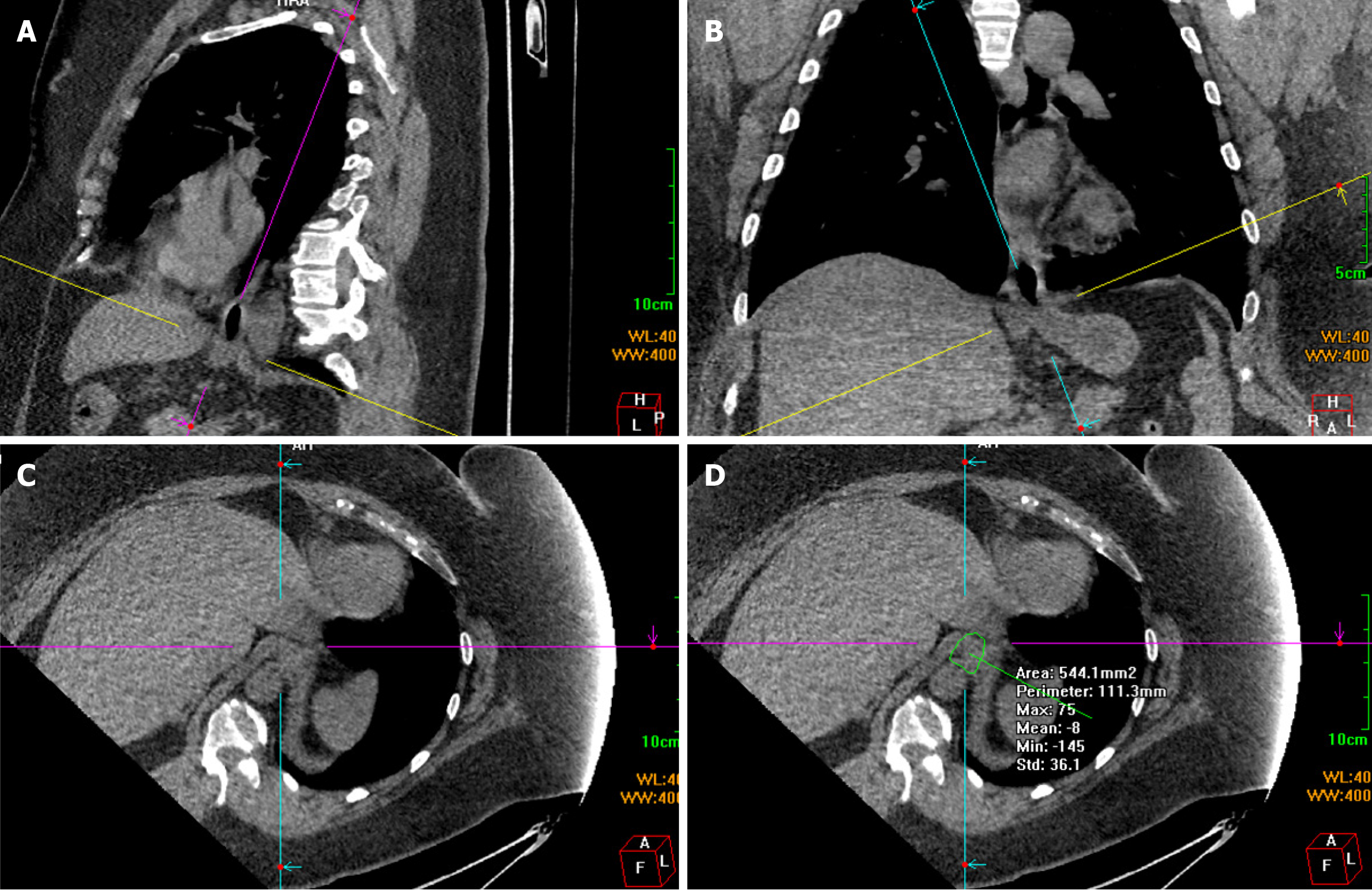

Chest and abdominal CT scans were performed using a 64-slice spiral CT scanner (Discovery CT750 HD; GE Medical Systems, Waukesha, WI, United States) covering the distal esophagus, diaphragm, and proximal stomach. Scanning was performed at a tube voltage of 120 kV, tube current of 70-260 mA, field of view of 50 cm, 521 × 512 matrix, and slice thickness of 5 mm. Scanning was enhanced with an intravenous bolus injection of 100 mL of the non-ionic contrast agent iohexol at 2.5-3.5 mL/second. The raw scan data were transmitted to a workstation for MPR with a slice thickness of 5 mm. The entire circumference of the esophageal hiatus was revealed using the double-oblique correction plane technique[5]. First, a slice passing through the center of the esophageal hiatus was identified in the sagittal plane. The line representing the axial plane was moved and rotated to intersect the anterior and posterior margins of the esophageal hiatus. This line generally slopes toward the spine. Consequently, the line representing the oblique coronal plane was approximately parallel to the distal esophagus (Figure 1A). The sagittal diameter was obtained by measuring the distance between the anterior and posterior margins. The line representing the axial plane was then moved and rotated on the coronal plane to intersect the left and right margins of the esophageal hiatus. This line generally tilted downward toward the right (Figure 1B). The distance between the left and right margins was measured to obtain the transverse diameter. The resulting double oblique axis plane was the esophageal hiatus plane (Figure 1C). The angle and position were slightly adjusted to maximize the hiatal margins. Finally, a polygonal tool was used to manually define the inner margins of the hiatus, and the cross-sectional area of the esophageal hiatus was measured (Figure 1D). Three researchers performed the measurements independently.

According to the Los Angeles classification[8], RE is classified into grades A-D based on the number, length, continuity, and circumferential involvement of the esophageal mucosal breaks. According to the refined Hill classification[9], HH is classified into grades I-IV based on the degree of tight fit between the mucosal fold of the gastroesophageal junction and the gastroscope.

The GERD-Q score[10] was calculated based on the frequency of reflux symptoms (heartburn, regurgitation, pain, nausea, and sleep disturbance) and medication use in the past 7 days, with a score of 8 indicating GERD.

All data were analyzed using SPSS 24.0 (IBM SPSS Statistics, Armonk, NY, United States). The measurement data are expressed as the means ± SD. Student’s t-test and Pearson’s correlation analysis were conducted for normally distributed data, whereas the rank-sum test and Spearman’s correlation analysis were performed for non-normally distributed data. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. Correlations were categorized as strong (r ≥ 0.9), moderate (0.9 > r ≥ 0.5), or weak (r < 0.5). Count data are presented as percentages (%). All figures were generated using Prism 8.4 (GraphPad Software, Boston, MA, United States) and ProcessOn (Beijing Da Mai Di LLC, Beijing, China).

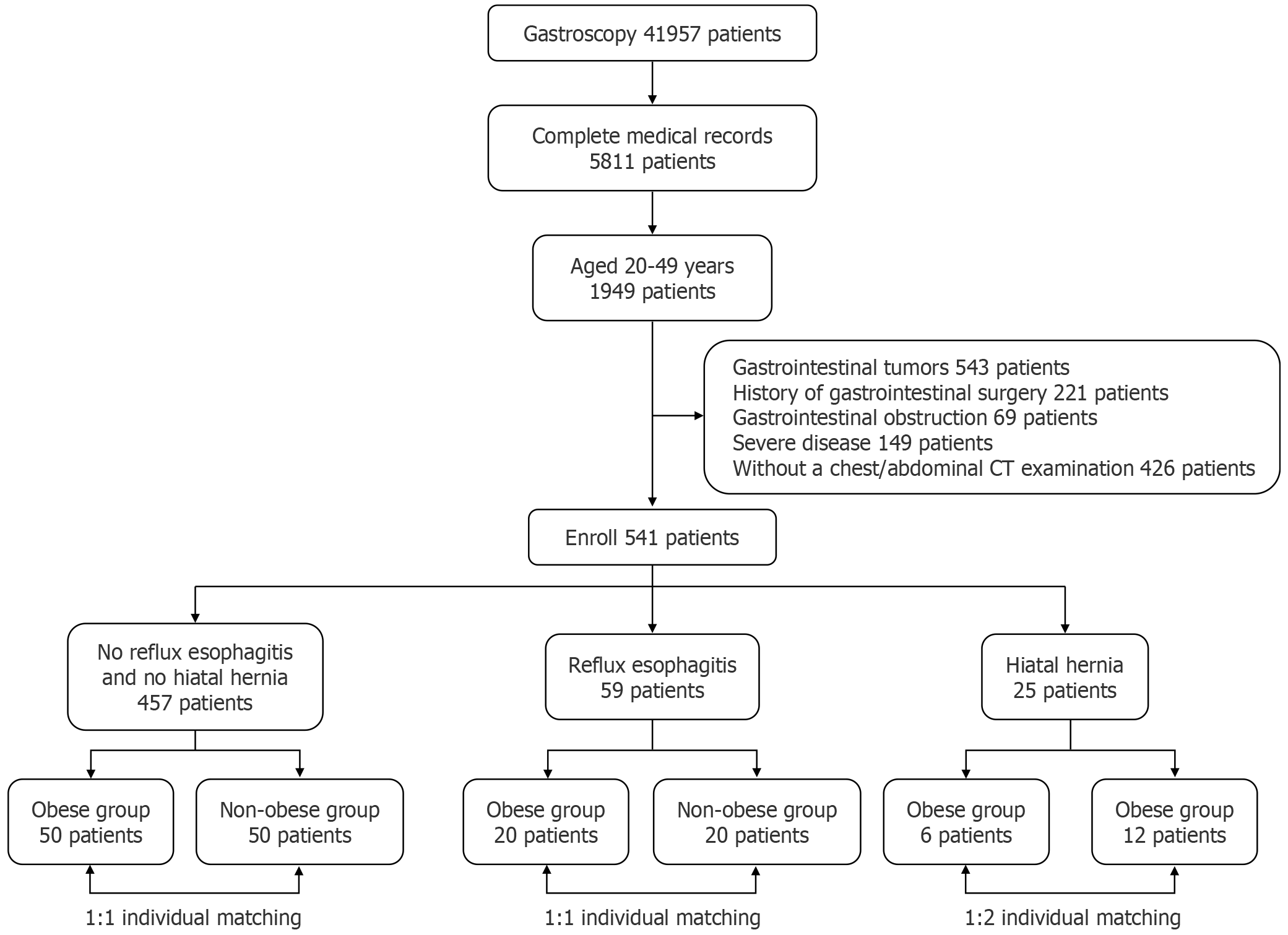

The initial screening yielded 41957 patients who underwent gastroscopy, and 36146 patients without complete medical records were excluded. Further screening yielded 1949 patients aged 20-49 years. Specifically, 543 patients with gastrointestinal tumors, 221 with a history of gastrointestinal surgery, 69 with gastrointestinal obstruction, 149 with severe disease, and 426 without chest/abdominal CT examinations were excluded based on the exclusion criteria. Ultimately, 541 patients were enrolled in this study. The participants were categorized according to their disease status into the no RE and no HH group (NRNHG), RE group (REG), and HH group (HHG). The NRNHG comprised 50 patients with obesity and 50 without obesity (all patients without obesity: BMI < 28 kg/m2). The REG consisted of 20 patients with obesity and 20 without obesity (2 patients without obesity: 30 kg/m2 > BMI > 28 kg/m2). The HHG included 6 patients with obesity and 12 without obesity (only 1 patient without obesity: 30 kg/m2 > BMI > 28 kg/m2) (Figure 2).

A total of 50 patients with and without obesity in the NRNHG were stratified by age in 10-year intervals. After statistical analyses, the rank-sum test results of multiple groups showed no statistically significant differences in height, weight, or BMI between the different age groups with or without obesity. The esophageal hiatus area and transverse and sagittal diameters were not significantly different between the groups (P > 0.05) (Table 1).

| Characteristic | Obese group | Non-obese group | ||||||

| 20-29 (n = 12) | 30-39 (n = 30) | 40-49 (n = 8) | P value | 20-29 (n = 12) | 30-39 (n = 30) | 40-49 (n = 8) | P value | |

| Age (year) | 25.42 ± 2.07 | 34.5 ± 3.14 | 41.75 ± 1.67 | < 0.01 | 25.83 ± 2.37 | 34.57 ± 2.76 | 41.88 ± 1.46 | < 0.01 |

| Height (cm) | 165.83 ± 5.1 | 165.87 ± 7.43 | 168.75 ± 4.68 | 0.248 | 165 ± 9.09 | 167.67 ± 9.25 | 168.5 ± 7.09 | 0.62 |

| Weight (kg) | 109.08 ± 13.4 | 106.65 ± 26.5 | 108.63 ± 20.03 | 0.424 | 53.14 ± 9.13 | 63.1 ± 10.12 | 59.19 ± 4.21 | 0.27 |

| BMI (kg/cm2) | 39.72 ± 5.23 | 38.6 ± 8.03 | 38.19 ± 7.09 | 0.498 | 19.39 ± 1.96 | 22.34 ± 2.37 | 20.87 ± 1.27 | 0.10 |

| Sagittal diameter (mm) | 14.95 ± 1.58 | 15.78 ± 2.38 | 16.55 ± 1.09 | 0.075 | 12.17 ± 2.37 | 11.72 ± 2.13 | 11.1 ± 1.44 | 0.572 |

| Transverse diameter (mm) | 15.29 ± 1.51 | 15.98 ± 2.14 | 16.97 ± 2.3 | 0.247 | 13.93 ± 2.97 | 13.07 ± 1.61 | 13.63 ± 1.45 | 0.538 |

| Area (mm2) | 319.77 ± 56.18 | 315.8 ± 85.6 | 374.56 ± 63.71 | 0.075 | 200.11 ± 86.65 | 210.22 ± 59.95 | 212.25 ± 47.21 | 0.564 |

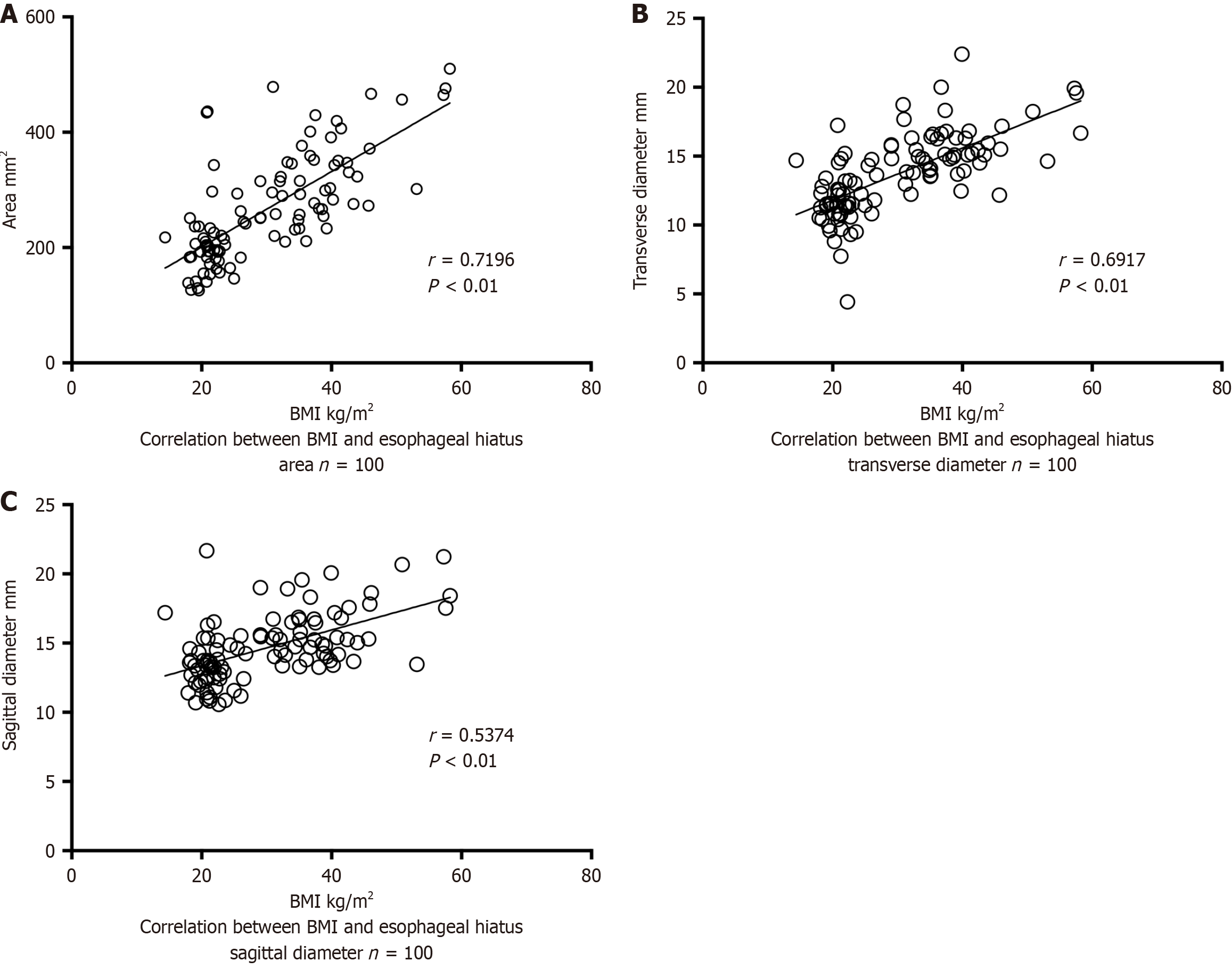

After excluding the effect of age on esophageal hiatus size, the correlation between BMI and esophageal hiatus size in 100 patients in the NRNHG was analyzed. Spearman’s correlation analysis showed a moderate positive correlation between BMI and the esophageal hiatus area and transverse and sagittal diameters (P < 0.01). Patients with a higher BMI had a larger esophageal hiatus area and larger transverse and sagittal diameters than their counterparts (Figure 3A-C).

The effect of obesity on esophageal hiatus size in the NRNHG and REG was analyzed. No statistically significant differences in age or height were observed between the obesity and non-obesity subgroups. Patients with obesity exhibited significantly larger esophageal hiatus area and transverse and sagittal diameters than patients without obesity

| Characteristic | NRNHG | REG | ||||

| Obese group (n = 50) | Non-obese group (n = 50) | P value | Obese group (n = 20) | Non-obese group (n = 20) | P value | |

| Age (year) | 33.48 ± 5.91 | 33.64 ± 5.71 | 0.912 | 38.4 ± 7.39 | 38.56 ± 7.61 | 0.942 |

| Height (cm) | 163.15 ± 24.2 | 167.16 ± 8.83 | 0.559 | 171.95 ± 6.55 | 173.06 ± 10.01 | 0.684 |

| Weight (kg) | 107.55 ± 22.68 | 60.08 ± 9.97 | < 0.01 | 105.46 ± 25.39 | 69.94 ± 12.41 | < 0.01 |

| BMI (kg/cm2) | 38.8 ± 7.2 | 21.4 ± 2.45 | < 0.01 | 35.54 ± 7.51 | 23.21 ± 2.72 | < 0.01 |

| Sagittal diameter (mm) | 15.7 ± 2.08 | 11.73 ± 2.08 | < 0.01 | 16.11 ± 2.31 | 15.13 ± 2.59 | 0.028 |

| Transverse diameter (mm) | 15.97 ± 2.06 | 13.37 ± 1.99 | < 0.01 | 16.77 ± 3.12 | 14.86 ± 3.59 | 0.022 |

| Area (mm2) | 326.15 ± 78 | 208.12 ± 64.44 | < 0.01 | 437.77 ± 444.25 | 259.66 ± 97.8 | 0.020 |

No statistically significant differences in age, height, weight, or BMI were noted between the two groups. Patients with obesity were classified as Los Angeles (LA)-A (70%) or LA-B (30%) according to the LA classification for RE, and their GERD-Q scores were 6.7 points. The esophageal hiatus area and transverse and sagittal diameters were larger in patients with RE than in those without RE; however, these differences were not statistically significant (P > 0.05). Patients without obesity were also classified as LA-A (60%) or LA-B (40%) according to the LA classification for RE, and their GERD-Q scores were 7.8 points. The esophageal hiatus area and sagittal diameter showed no significant differences (P > 0.05), whereas the transverse diameter was statistically different between patients with and without RE (P < 0.01) (Table 3).

| Characteristic | Obese group | Non-obese group | ||||

| RE (n = 20) | Non-RE (n = 20) | P value | RE (n = 20) | Non-RE (n = 20) | P value | |

| Age (year) | 38.4 ± 7.39 | 36.8 ± 5.47 | 0.524 | 38.56 ± 7.61 | 37.05 ± 5.39 | 0.558 |

| Height (cm) | 171.95 ± 6.55 | 168.2 ± 6.88 | 0.059 | 173.06 ± 10.01 | 168.5 ± 6.54 | 0.101 |

| Weight (kg) | 105.46 ± 25.39 | 109.8 ± 26.84 | 0.386 | 69.94 ± 12.41 | 61.87 ± 8.57 | 0.06 |

| BMI (kg/cm2) | 35.54 ± 7.51 | 38.67 ± 8.04 | 0.094 | 23.21 ± 2.72 | 21.71 ± 2.01 | 0.70 |

| Sagittal diameter (mm) | 16.11 ± 2.31 | 15.92 ± 1.89 | 0.715 | 14.86 ± 3.59 | 13.4 ± 1.45 | 0.335 |

| Transverse diameter (mm) | 16.77 ± 3.12 | 16.35 ± 2.15 | 0.839 | 15.13 ± 2.59 | 11.25 ± 1.52 | 0.023 |

| Area (mm2) | 437.77 ± 444.25 | 346.11 ± 70.75 | 0.935 | 259.66 ± 97.8 | 199.43 ± 38.23 | 0.079 |

Six patients with obesity complicated HH were included in this study. Among them, 3 patients (50%) were classified as having Hill grade III, with an esophageal hiatus diameter 1.5 times the width of the endoscope, and 3 patients were classified as having grade IV, with an esophageal hiatus diameter twice the width of the endoscope. No statistically significant differences in the esophageal hiatus area, transverse diameter, or sagittal diameter (P > 0.05) were observed between patients with and without HH. In addition, 12 patients without obesity had HH, of whom 7 (58.3%) were classified as having Hill grade III, with the esophageal hiatus expansion width reaching 1.5 times that of the endoscope, and 5 were classified as having grade IV, with the expansion width reaching twice that of the gastroscope. No statistically significant differences were found in the esophageal hiatus area and sagittal diameter, whereas the transverse diameter showed significant differences between patients with and without HH (P < 0.01) (Table 4).

| Characteristic | Obese group | Non-obese group | ||||

| HH (n = 6) | Non-HH (n = 12) | P value | HH (n = 12) | Non-HH (n = 12) | P value | |

| Age (year) | 40.17 ± 8.54 | 38.25 ± 6.72 | 0.279 | 41.58 ± 7.03 | 37.75 ± 5.86 | 0.68 |

| Height (cm) | 173.33 ± 6.62 | 168.75 ± 6.24 | 0.155 | 170.5 ± 7.24 | 167.25 ± 8.21 | 0.543 |

| Weight (kg) | 97.83 ± 4.54 | 109.96 ± 22.04 | 0.574 | 70.73 ± 8.35 | 65.45 ± 13.66 | 0.112 |

| BMI (kg/cm2) | 32.64 ± 2.23 | 38.49 ± 6.51 | 0.059 | 24.36 ± 2.71 | 23.19 ± 3.11 | 0.248 |

| Sagittal diameter (mm) | 15.07 ± 2.96 | 16.11 ± 1.3 | 0.349 | 13.7 ± 3.22 | 14.16 ± 2.18 | 0.525 |

| Transverse diameter (mm) | 15.91 ± 4.27 | 16.55 ± 2.25 | 0.399 | 15.45 ± 2.51 | 12.14 ± 2.25 | 0.005 |

| Area (mm2) | 302.45 ± 82.72 | 346.11 ± 75.85 | 0.075 | 276.33 ± 93.42 | 220.57 ± 51.34 | 0.106 |

The esophageal hiatus is composed of diaphragmatic muscle rather than the more resilient tendinous tissue. A physiological gap exists between the diaphragm and the esophagus, resulting in incomplete closure, which renders the area relatively weak and prone to herniation. The crura of the diaphragm, phrenoesophageal ligament, and esophageal branches of the phrenic nerve collectively form the anatomical basis for antireflux mechanisms and prevention of HH. However, there remains no universally accepted standard for defining the normal size of the esophageal hiatus, particularly in patients with obesity. Obesity is a well-established risk factor for RE and HH. The necessity of performing antireflux procedures or hernia repair concurrently with LSG in patients who do not meet the diagnostic criteria for GERD or have only type I HH remains controversial. Some experts advocate for routine intraoperative exploration of the hiatus during LSG in patients with obesity with preoperative reflux symptoms—even if they fall short of GERD criteria - or endoscopic evidence of any degree of RE, particularly when the Hill classification exceeds grade II. The decision to repair is often based on subjective assessments, such as the size of the anterior cardial depression or the perceived weakness of the hiatal tissues, rather than objective metrics, limiting its generalizability and reproducibility. Domestic studies frequently use a hiatal diameter of 5 cm as the threshold for intervention, while international studies often adopt 4 cm[11,12]. However, the esophageal hiatus is an oblique, noncircular structure, making unidirectional measurements inadequate for reflecting its true dimensions. Thus, establishing normative reference ranges for hiatal size in patients with obesity is of critical importance.

Age and obesity are significant contributing factors to HH. With age, the gradual loss of elastin, collagen, and matrix metalloproteinases that constitute the extracellular matrix causes muscle weakness and decreases diaphragmatic elasticity. Consequently, the function of the structures around the esophagus is weakened, the esophageal hiatus is enlarged, and the gastroesophageal junction moves upward, resulting in HH and reflux symptoms, with pronounced manifestations typically observed between 60 years and 80 years of age[13,14]. In this study, no significant differences in the esophageal hiatus area and transverse and sagittal diameters were observed among the different age groups of patients with and without obesity aged 20-49 years. This finding is supported by a retrospective study of 119 patients in North America that stratified participants aged 20-60 years and identified no correlation between age and esophageal hiatus size[15]. In the young and middle-aged strata, age had no effect on the esophageal hiatus size.

Among the NRNHG, the esophageal hiatus area of patients with obesity was significantly larger than that of patients without obesity, and BMI showed a moderate positive linear correlation with the esophageal hiatus area and transverse and sagittal diameters. In patients with obesity, the esophageal hiatus had sagittal and transverse diameters and area of 15.7 ± 2.08 mm, 15.97 ± 2.06 mm, and 326.15 ± 78 mm2, respectively. The maximum and minimum areas were 510.1 mm2 and 210.03 mm2, respectively. These results are consistent with the trends reported outside China. Boru et al[6] reported that the esophageal hiatus area of patients with normal weight and without HH or RE was 3.69 cm2, whereas that of patients with obesity was 3.98 cm2. During bariatric surgery, indications for esophageal hiatus exploration should be based on the effect of obesity on the esophageal hiatus. Preoperative CT-based hiatal measurement offers objective data, mitigating the risk of overestimating hiatal size due to pneumoperitoneum-induced artificial expansion during lapa

No consensus regarding the effects of LSG on the cause and exacerbation of GERD has been established. Studies have indicated that LSG can not only effectively alleviate GERD but may also induce or aggravate GERD, with incidences ranging from 8% to 52%[16,17], the highest being 83.3%[18]. This may be related to the lack of uniformity in the LSG details. The first factor is the integrity of the gastric antrum. The gastric antrum effectively facilitates gastric motility, promotes gastric emptying, and reduces intragastric pressure[19]. The second detail concerns the protection of antireflux anatomical structures at the cardia, such as maintaining the acute angle of His and protecting the integrity of the pharyngoesophageal ligament and esophageal branches of the phrenic nerve at the gastroesophageal junction[20,21]. A 1-year self-controlled study in 2013 reported that routine esophageal hiatus exploration during LSG increased the incidence of HH by 20%[22]. Improper manipulation of the gastroesophageal junction may lead to HH and intrathoracic sleeve migration, and > 40% of patients with intrathoracic sleeve migration developed GERD symptoms[23]. Santonicola et al[24] explored the esophageal hiatus during LSG and conducted concurrent HH repair in 78 patients with concomitant type I HH, and LSG alone in 108 patients without HH before surgery. The results of the 6-month postoperative follow-up showed that 43.3% of patients who underwent concurrent HH repair still had GERD symptoms, and 22.9% developed new GERD symptoms. In the LSG alone group, the percentages of patients with persistent and new GERD symptoms were 22.5% and 17.7%, respectively. Therefore, whether patients with obesity with type I HH but without GERD benefit from bariatric surgery combined with HH repair remains unclear.

In this study, 70% of patients with obesity with comorbid RE were classified as Los Angeles grade A, and all had GERD-Q scores ≤ 6.7, indicating mild RE at this stage. The esophageal hiatus area of patients with obesity with RE was 437.77 ± 444.25 mm2, which was larger than that of patients with obesity without RE. However, this difference was not statistically significant. This study included 6 patients with obesity with HH and 12 patients without obesity with HH. All HHs were diagnosed by gastroscopy and all were Hill grade > II. The hiatal width was less than twice the diameter of the endoscope, and no herniation of the stomach or other tissues into the thoracic cavity was observed, consistent with type I HH. No significant difference in esophageal hiatus size was detected between the two groups on CT. In patients with obesity with mild reflux and type I HH, no anatomical hiatal enlargement was observed. Excessive dissection or eva

International guidelines recommend observation for type I HHs in patients without GERD[25], especially for HHs detected by endoscopy, due to the extremely low probability of developing acute obstruction and progressive RE[26]. In the present study, the transverse diameter of the esophageal hiatus significantly increased in patients without obesity in the REG and HHG. This is consistent with the progression of HH, which mainly manifests as an enlarged transverse diameter of the esophageal hiatus, that is, a morphological change from the original elliptical shape to a circular shape[27-29]. These findings offer important reference values for formulating the indications for further related examinations and intraoperative exploration in patients with endoscopic evidence suggestive of RE or HH. Several limitations warrant consideration. First, the retrospective case-control design restricts causal inference, and the absence of longitudinal follow-up precludes assessment of disease progression. Second, the limited sample size - especially in the HH subgroup - may reduce statistical power. Finally, unmeasured confounders (e.g., dietary patterns, geographic disparities) could bias the observed associations.

Compared to patients without obesity, those with obesity had a larger esophageal hiatus size, with an esophageal hiatus area and transverse and sagittal diameters of 326.15 ± 78 mm2, 15.97 ± 2.06 mm, and 15.7 ± 2.08 mm, respectively. The esophageal hiatus area and transverse and sagittal diameters increased with increasing BMI. Patients with obesity with mild RE or type I HH did not exhibit an enlarged esophageal hiatus. For patients with endoscopic evidence suggestive of RE or HH, further CT measurements of the esophageal hiatus area and transverse and sagittal diameters could provide support for determining the need for intraoperative exploration. The transverse diameter of the esophageal hiatus offers greater reference values.

We thank Kai-Xuan Yang from the China National Clinical Research Center for Neurological Diseases, Beijing Tiantan Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing, China for reviewing the statistical methods used in this study.

| 1. | Bureau of Disease Prevention and Control. National Health Commission. Report on Nutrition and Chronic Disease Status of Chinese Residents (2020). Beijing: People’s medical Publishing House, 2021. |

| 2. | Jacobson BC, Somers SC, Fuchs CS, Kelly CP, Camargo CA Jr. Body-mass index and symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux in women. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2340-2348. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 504] [Cited by in RCA: 436] [Article Influence: 21.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Yu HX, Han CS, Xue JR, Han ZF, Xin H. Esophageal hiatal hernia: risk, diagnosis and management. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;12:319-329. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Li MY, Liu YJ, Wang GQ, Yu WH, Xin H, Li YX, Yao QY, Li Z, Liu SZ, Liu Y, Zhang SH, Lv JL, Liang XY, Xu DS, Lin HW, Lin LX, Ding YL, Meng FQ, Han JG, Wang J, Mao ZQ, Yao LB, Zhang XW, Akbar Ally and Yin JH, Zhang JC, Han JL, Zhang NW, Wu LS, Li GL, Jiang T, Zhu LY, Wang J, Wu LP, Wang B, Han W, Li ZF, Zhu SH, Kerimu Abdurayimu, Hu SY, Zhang P, Zhang ZT; Greater China Metabolic And Bariatric Surgery Group. [Greater China Bariatric and Metabolic Surgery Database 2023 Annual Report]. Zhongguo Shiyong Waike Zazhi. 2024;44:552-563. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 5. | Ouyang W, Dass C, Zhao H, Kim C, Criner G; COPDGene Investigators. Multiplanar MDCT measurement of esophageal hiatus surface area: association with hiatal hernia and GERD. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:2465-2472. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Boru CE, Rengo M, Iossa A, De Angelis F, Massaro M, Spagnoli A, Guida A, Laghi A, Silecchia G. Hiatal Surface Area's CT scan measurement is useful in hiatal hernia's treatment of bariatric patients. Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol. 2021;30:86-93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Rengo M, Boru CE, Badia S, Iossa A, Bellini D, Picchia S, Panvini N, Carbone I, Silecchia G, Laghi A. Preoperative measurement of the hiatal surface with MDCT: impact on surgical planning. Radiol Med. 2021;126:1508-1517. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Armstrong D, Bennett JR, Blum AL, Dent J, De Dombal FT, Galmiche JP, Lundell L, Margulies M, Richter JE, Spechler SJ, Tytgat GN, Wallin L. The endoscopic assessment of esophagitis: a progress report on observer agreement. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:85-92. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 754] [Cited by in RCA: 790] [Article Influence: 26.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Hill LD, Kozarek RA. The gastroesophageal flap valve. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1999;28:194-197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Dent J, Vakil N, Jones R, Bytzer P, Schöning U, Halling K, Junghard O, Lind T. Accuracy of the diagnosis of GORD by questionnaire, physicians and a trial of proton pump inhibitor treatment: the Diamond Study. Gut. 2010;59:714-721. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 223] [Cited by in RCA: 260] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Snyder B, Wilson E, Wilson T, Mehta S, Bajwa K, Klein C. A randomized trial comparing reflux symptoms in sleeve gastrectomy patients with or without hiatal hernia repair. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12:1681-1688. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Dalkılıç MS, Şişik A, Gençtürk M, Yılmaz M, Erdem H. Comment on: Impact of concurrent hiatal hernia repair during laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy on patient-reported gastroesophageal reflux symptoms: a state-wide analysis. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2023;19:666-667. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Shimazu T, Matsui T, Furukawa K, Oshige K, Mitsuyasu T, Kiyomizu A, Ueki T, Yao T. A prospective study of the prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux disease and confounding factors. J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:866-872. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kim J, Hiura GT, Oelsner EC, Yin X, Barr RG, Smith BM, Prince MR. Hiatal hernia prevalence and natural history on non-contrast CT in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2021;8:e000565. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Dass C, Dass G, Fisher S, Litvin J. The effect of age and sex on esophageal hiatal surface area among normal North American adults using multidetector computed tomography. Surg Radiol Anat. 2022;44:899-906. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Rosenthal RJ; International Sleeve Gastrectomy Expert Panel, Diaz AA, Arvidsson D, Baker RS, Basso N, Bellanger D, Boza C, El Mourad H, France M, Gagner M, Galvao-Neto M, Higa KD, Himpens J, Hutchinson CM, Jacobs M, Jorgensen JO, Jossart G, Lakdawala M, Nguyen NT, Nocca D, Prager G, Pomp A, Ramos AC, Rosenthal RJ, Shah S, Vix M, Wittgrove A, Zundel N. International Sleeve Gastrectomy Expert Panel Consensus Statement: best practice guidelines based on experience of >12,000 cases. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2012;8:8-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 713] [Cited by in RCA: 733] [Article Influence: 48.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Sancho Moya C, Bruna Esteban M, Sempere García-Argüelles J, Ferrer Barceló L, Monzó Gallego A, Mirabet Sáez B, Mulas Fernández C, Albors Bagá P, Vázquez Prado A, Oviedo Bravo M, Montalvá Orón E. The Impact of Sleeve Gastrectomy on Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease in Patients with Morbid Obesity. Obes Surg. 2022;32:615-624. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Georgia D, Stamatina T, Maria N, Konstantinos A, Konstantinos F, Emmanouil L, Georgios Z, Dimitrios T. 24-h Multichannel Intraluminal Impedance PH-metry 1 Year After Laparocopic Sleeve Gastrectomy: an Objective Assessment of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. Obes Surg. 2017;27:749-753. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Shi XC, Yan WM, Bai RX. [Efficacy of complete preservation of gastric antrum for postoperative reflux esophagitis during laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy]. Fubu Waike. 2022;35:174-179. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 20. | Petersen WV, Schneider JH. Functional importance of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy for the lower esophageal sphincter in patients with morbid obesity. Obes Surg. 2012;22:949. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Bhandarkar S, Kalikar V, Nasta A, Goel R, Patankar R. Post-laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy, intrathoracic sleeve migration and its management: A case series and review of literature. J Minim Access Surg. 2023;19:544-547. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Tai CM, Huang CK, Lee YC, Chang CY, Lee CT, Lin JT. Increase in gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms and erosive esophagitis 1 year after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy among obese adults. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:1260-1266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Karila-Cohen P, Pelletier AL, Saker L, Laouénan C, Bachelet D, Khalil A, Arapis K. Staple Line Intrathoracic Migration After Sleeve Gastrectomy: Correlation between Symptoms, CT Three-Dimensional Stomach Analysis, and 24-h pH Monitoring. Obes Surg. 2022;32:1-9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Santonicola A, Angrisani L, Cutolo P, Formisano G, Iovino P. The effect of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy with or without hiatal hernia repair on gastroesophageal reflux disease in obese patients. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2014;10:250-255. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Daly S, Kumar SS, Collings AT, Hanna NM, Pandya YK, Kurtz J, Kooragayala K, Barber MW, Paranyak M, Kurian M, Chiu J, Ansari MT, Slater BJ, Kohn GP. SAGES guidelines for the surgical treatment of hiatal hernias. Surg Endosc. 2024;38:4765-4775. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Ahmed SK, Bright T, Watson DI. Natural history of endoscopically detected hiatus herniae at late follow-up. ANZ J Surg. 2018;88:E544-E547. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Saad AR, Velanovich V. Anatomic Observation of Recurrent Hiatal Hernia: Recurrence or Disease Progression? J Am Coll Surg. 2020;230:999-1007. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Marchand P. The anatomy of esophageal hiatus of the diaphragm and the pathogenesis of hiatus herniation. J Thorac Surg. 1959;37:81-92. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Christensen J, Miftakhov R. Hiatus hernia: a review of evidence for its origin in esophageal longitudinal muscle dysfunction. Am J Med. 2000;108 Suppl 4a:3S-7S. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/