Published online Dec 28, 2025. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v17.i12.114211

Revised: October 22, 2025

Accepted: December 3, 2025

Published online: December 28, 2025

Processing time: 103 Days and 21.8 Hours

Thermal ablation has become an established minimally invasive alternative to surgery for papillary thyroid carcinoma, particularly in low-risk patients seeking effective treatment with reduced morbidity. While clinical outcomes are favora

Core Tip: Thermal field management offers a new way to perform thyroid ablation by focusing on how heat spreads within the tissue rather than just removing the nodule. It combines two key ideas of actively adjusting the ablation power and position to control heat, and passively protecting nearby structures using methods such as hydrodissection and careful preservation of tissue layers. This approach aims to treat the disease effectively while reducing the chance of voice changes, pain, or discomfort. Thermal field management shifts attention from technical success alone to overall safety and comfort, making ablation a more precise and patient-centered procedure.

- Citation: Sathish S. Thermal field management in thyroid ablation for papillary thyroid carcinoma: Advancing precision and patient-centered care. World J Radiol 2025; 17(12): 114211

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8470/full/v17/i12/114211.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4329/wjr.v17.i12.114211

Papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC) accounts for over 80% of all thyroid cancers and generally carries an excellent prognosis. For decades, surgical thyroidectomy has been the standard of care, yet it often carries long-term burdens including hypothyroidism, cervical scarring, and impaired quality of life[1,2]. Minimally invasive approaches such as thermal ablation (TA) techniques, including radiofrequency ablation and microwave ablation, have demonstrated safety and efficacy in benign nodules and in selected patients with PTC. They offer preservation of thyroid function and avoidance of surgical morbidity[3-5]. According to the 2024 International Expert Consensus on Ultrasound-Guided TA for T1N0M0 PTC, TA is best suited for solitary or recurrent T1N0M0 PTC[6]. It offers advantages such as smaller scars, reduced pain, preservation of thyroid function, and shorter recovery, compared with traditional surgery, while also improving postoperative quality of life and economic outcomes[7]. Contraindications include multifocal disease, extrathyroidal extension, and nodal metastasis beyond the central compartment. However, outcomes across centers remain heterogeneous, particularly with regard to minor but clinically meaningful complications such as dysphonia, pain, and cervical discomfort. Although technical success rates are consistently high, patient-reported experiences vary widely. Systematic reviews report complication rates ranging from 0% to 16.7%, with voice change, pain, and neck discomfort being most common[5]. Such variability highlights that procedural success depends not only on equipment or operator skill but on conceptual frameworks that systematically minimize collateral injury. Injury to the surrounding tissues during the ablation is considered as the primary etiological factor for such variable patient outcomes[8]. To overcome this, Cai et al[9], introduce the concept of thermal field management (TFM) in a retrospective cohort study of 490 patients with PTC treated with TA. Their results show a statistically significant reduction in voice change and a numerical reduction in pain in patients treated under a TFM framework compared with those treated conventionally. TFM provides a structured method for confining heat to the target lesion while protecting adjacent structures. In this article, the discussion primarily focuses on the role of TFM in PTC rather than benign nodules, to reflect its emerging role in oncologic safety and precision.

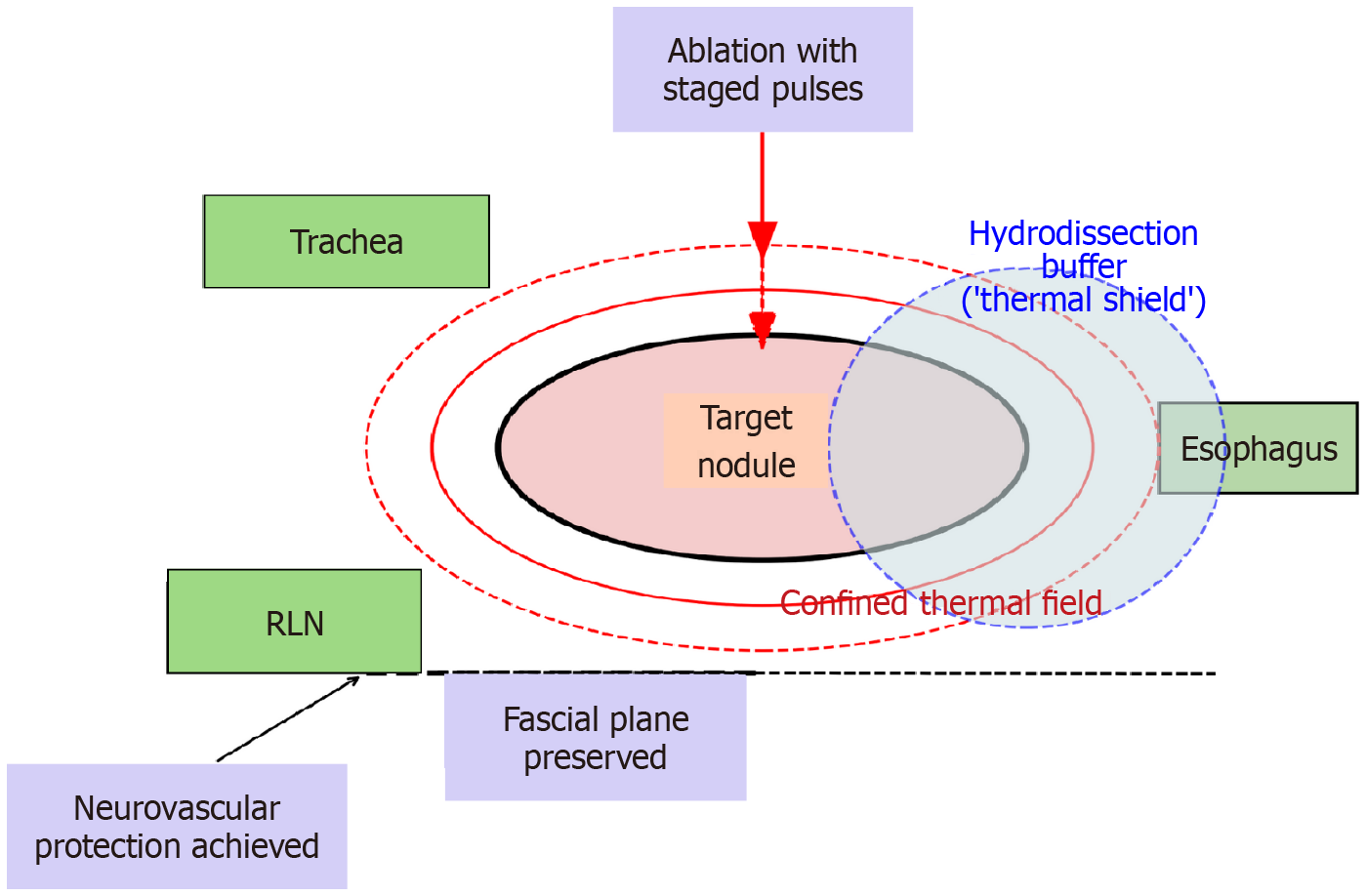

TA relies on the propagation of heat through tissue until cytotoxic thresholds are reached[10]. In the thyroid, the challenge is not generating sufficient heat but containing its spread within a narrow margin. The thyroid is surrounded by heat-sensitive structures including recurrent laryngeal nerves, trachea, esophagus, vascular structures, and perithyroidal fascia. A small excess in energy delivery or unrecognized heat leakage can result in complications that are minor in classification but significant for the patient[10-12].

Active management: Active TFM describes the deliberate control of how heat is generated and shaped during ablation. Conventional practice has often emphasized needle placement and endpoint assessment, but TFM argues for conscious modulation of power and timing throughout the procedure. In practical terms, this involves adjusting generator output in stages, allowing tissue impedance and echogenic changes to stabilize before proceeding further. Such pacing prevents uncontrolled conductive surges that may propagate into adjacent structures. Shorter dwell times and micro-pauses can reduce nociceptive spikes, while careful reorientation of the applicator modifies the geometry of isotherms and permits a more tailored ablation zone. Ultrasound feedback, such as microbubble formation and tissue echogenicity, provides real-time information that guides power titration before excessive thermal spread occurs.

The clinical relevance of active TFM is supported by early studies reporting reductions in dysphonia and procedural pain when such strategies are applied. In Cai et al’s retrospective cohort[9], patients managed under an active TFM framework had significantly fewer episodes of voice change compared with conventional ablation. Similar principles have been adopted in benign nodule ablation, where staged power delivery shortened recovery time and minimized discomfort[13,14]. These observations indicate that active TFM is biologically plausible and clinically valuable.

Passive management: Passive TFM refers to techniques that limit the extension of thermal energy beyond the target lesion. The most widely recognized method is hydrodissection, which introduces fluid between the ablation zone and vulnerable structures[15,16]. Injecting dextrose 5% in water during radiofrequency ablation is favored because it reduces ionic conduction, whereas isotonic saline is often employed in microwave ablation. The mechanical displacement produced by these fluids can create several millimeters of protective distance, sufficient to lower the risk of nerve or esophageal injury. Importantly, hydrodissection should not be applied indiscriminately but guided by anatomic risk; in posterior capsule lesions, separation of the recurrent laryngeal nerve groove is critical, while medial lesions require tracheal displacement[17].

In addition to fluid buffers, passive TFM emphasizes the preservation of natural fascial planes. Maintaining these barriers prevents adhesional fibrosis and reduces the development of painful tethering between strap muscles and the thyroid capsule. By respecting fascial integrity, operators decrease the likelihood of chronic discomfort and swallowing impairment.

The effectiveness of hydrodissection and fascial preservation is well supported in interventional oncology[18]. In hepatic ablation, hydrodissection of the gallbladder or bowel reduces collateral injury[19-21]. In thyroid ablation, studies have consistently shown that posterior capsule hydrodissection lowers the incidence of recurrent laryngeal nerve damage[15,22]. Passive TFM, therefore, consolidates these protective maneuvers into an explicit doctrine for routine practice.

The evidence base for TFM is still limited but growing. Cai et al[9] reported that TFM reduced transient voice change from 6.5% to 0.9% and decreased pain complaints compared with conventional ablation. Systematic reviews also suggest that procedures incorporating deliberate energy modulation and structured hydrodissection achieve lower complication rates[3-5]. In benign nodules, long-term series have demonstrated that careful pacing and boundary protection produce durable volume reduction with minimal morbidity[23-25].

Analogous evidence comes from other organ systems. In hepatocellular carcinoma, the use of hydrodissection to displace adjacent bowel is a recognized method of preventing perforation and peritonitis[25,26]. Similarly, in renal tumor ablation, protecting the collecting system with ureteral stents or fluid instillation reduces strictures and urine leaks[27-29]. These examples demonstrate that the principle of protecting vulnerable structures by controlling energy propagation is not unique to the thyroid. What distinguishes TFM in the neck is the narrow margin for error: Millimeters separate the target from structures essential for voice and swallowing. Thus, while TFM may generalize conceptually, its greatest clinical impact may remain in sites where functional structures are densely clustered around the lesion (Figure 1).

The clinical implications of TFM are evident both for individual patients and for broader practice standardization. By deliberately integrating active modulation of energy with passive protection of surrounding structures, TFM reduces complication rates and enhances recovery. In Cai et al’s cohort[9] of 490 patients, transient voice change occurred in only 0.9% of those treated with TFM compared to 6.5% with conventional ablation (P = 0.049), while pain complaints were also numerically lower (3.7% vs 9.7%). These data illustrate that TFM is not a theoretical refinement but a clinically meaningful intervention that improves patient comfort and functional outcomes. By containing the thermal field, TFM lowers peak temperature and steep thermal gradients at capsule–nerve interfaces, limiting neurotoxicity and edema. Hydrodissection increases the effective distance-to-danger (recurrent laryngeal nerve external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve, paratracheal vessels), while pulsed power delivery reduces conductive overshoot that precipitates neurapraxia and microvascular injury[30]. The net effect is fewer nerve-related voice changes and less perilesional swelling or hematoma without compromising ablation completeness[13,31]. Emerging evidence also indicates that careful control of thermal fields may reduce sequelae such as rupture, hematoma, and delayed bleeding in both benign and malignant thyroid ablations[32]. Incorporating TFM principles during benign nodule ablation could thus enhance safety and reduce post-procedural complications. Importantly, TFM also provides a framework that can be taught, measured, and standardized, in the same way that Enhanced Recovery After Surgery protocols transformed perioperative care by packaging existing practices into reproducible pathways with demonstrable impact[33,34]. Thus, TFM has the potential to narrow inter-operator variability, facilitate structured training, and provide benchmarks for quality assurance. Table 1 shows how TFM-governed ablation differs from conventional practice in its conceptual orientation, control of energy, protection of boundaries, and emphasis on reproducibility.

| Domain | Conventional thyroid ablation | TFM-governed ablation |

| Energy delivery | Continuous or static power settings | Staged power modulation with deliberate pacing and micro-pauses |

| Applicator control | Fixed orientation and depth | Dynamic repositioning and geometry adjustment to tailor ablation zone |

| Boundary protection | Occasional or ad-hoc hydrodissection | Structured hydrodissection with fascial-plane preservation |

| Risk awareness | Operator-dependent judgment | Explicit attention to RLN, esophagus, trachea during planning and delivery |

| Clinical outcomes | Variable rates of dysphonia and post-procedural pain | Reduced dysphonia (0.9% vs 6.5%) and fewer pain complaints (3.7% vs 9.7%) |

| Reproducibility | Highly dependent on operator skill | Codified doctrine allowing standardization across operators and centers |

Despite these advantages, the current evidence for TFM is derived from a retrospective, single-center study with a median follow-up of only 10 months. This short duration is a significant limitation, as the ultimate success of any cancer therapy is measured not just by immediate results but by oncologic durability, the long-term control of the disease and prevention of recurrence. For PTC, recurrence can occur years after the initial treatment[35,36]. Therefore, a 10-month follow-up is insufficient to definitively assess the treatment’s long-term effectiveness. Prospective multicenter studies with extended follow-up periods are essential to confirm the safety and efficacy of TFM. Such studies are also needed to validate whether such heat-field control influences recurrence or long-term prognosis as primary end-point in PTC[37]. Such studies can provide the robust data needed to establish TFM as a credible and lasting alternative to traditional surgery. Also, while statistically significant reductions were seen in transient voice change, further research is needed to validate the effect on pain. Furthermore, the results reflect the performance of experienced operators in a high-volume setting; therefore, their generalizability to broader practice environments remains uncertain.

Moving forward, TFM must evolve from a descriptive concept into a codified, evidence-based practice. Technological integration will also play a central role: Artificial intelligence can play a central role by assisting with predictive thermal mapping. By analyzing real-time data from the ablation process, such as tissue impedance and echogenicity, an AI system could model the predicted thermal spread. This would provide the operator with a visual, real-time “heat map” to show exactly where the thermal energy is going. The AI could then offer real-time guidance on power and timing adjustments to contain the heat within the target lesion and away from vulnerable structures. Beyond real-time feedback, advanced imaging, such as contrast-enhanced ultrasound, elastography, and computed tomography perfusion, can provide objective assessments of heat spread[38,39]. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound, for example, could be used to confirm that the entire tumor has been ablated by showing the absence of blood flow in the treated area. Elastography could assess chan

| 1. | Yan L, Li Y, Li X, Xiao J, Jing H, Yang Z, Li M, Song Q, Wang S, Che Y, Luo Y. Thermal Ablation for Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2024;151:9-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Min Y, Wang X, Chen H, Chen J, Xiang K, Yin G. Thermal Ablation for Papillary Thyroid Microcarcinoma: How Far We Have Come? Cancer Manag Res. 2020;12:13369-13379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Gao X, Yang Y, Wang Y, Huang Y. Efficacy and safety of ultrasound-guided radiofrequency, microwave and laser ablation for the treatment of T1N0M0 papillary thyroid carcinoma on a large scale: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Hyperthermia. 2023;40:2244713. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Chatzisouleiman I, Kolovou V, Tolley N, Mochloulis G, Katotomichelakis M, Chaidas K. Radiofrequency and microwave ablation as promising minimally invasive treatment options for papillary thyroid micro-carcinoma: a systematic review. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2025. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Tong M, Li S, Li Y, Li Y, Feng Y, Che Y. Efficacy and safety of radiofrequency, microwave and laser ablation for treating papillary thyroid microcarcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Hyperthermia. 2019;36:1278-1286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Zhao ZL, Wang SR, Kuo J, Çekiç B, Liang L, Ghazi HA, Xu SH, Amabile G, Wu SS, Yadav A, Dong G, Janssen I, Fan BQ, Fukunari N, He JF, Dung LT, Yu SY, Leong S, Yu JJ, Chou YH, De Cicco R, Che Y, Cheng KL, Kandil E, Lin WC, Xu D, Russell J, Lu M, Tufano RH, Qian LX, Randolph GW, Zhou JQ, Mauri G, Su HH, Russell M, Abdelhamid Ahmed AH, Patel K, Baek JH, Kim JH, Wei Y, Yu MA. 2024 International Expert Consensus on US-guided Thermal Ablation for T1N0M0 Papillary Thyroid Cancer. Radiology. 2025;315:e240347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Papini E, Basile M, Novizio R, Paoletta A, Persichetti A, Samperi I, Scoppola A, Crescenzi A, D'Amore A, Deandrea M, Frasoldati A, Garberoglio R, Guglielmi R, Mauri G, Lombardi CP, Puglisi S, Rago T, Triggiani V, Van Doorne D, Salvatore D, Saulle R, Attanasio R. Cost analysis and resource allocation in the management of benign thyroid nodules: a comparison of surgery and thermal ablation techniques. J Endocrinol Invest. 2025;48:1769-1780. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ntelis S, Linos D. Efficacy and safety of radiofrequency ablation in the treatment of low-risk papillary thyroid carcinoma: a review. Hormones (Athens). 2021;20:269-277. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Cai WJ, Li Y, Wei Y, Zhao ZL, Wu J, Cao SL, Peng LL, Li SQ, Yu MA. Thermal field management improves patient-reported outcomes during ablation for papillary thyroid carcinoma: A retrospective cohort study. World J Radiol. 2025;17:111924. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Zhao ZL, Wei Y, Peng LL, Li Y, Lu NC, Yu MA. Recurrent Laryngeal Nerve Injury in Thermal Ablation of Thyroid Nodules-Risk Factors and Cause Analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2022;107:e2930-e2937. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Baek JH, Lee JH, Valcavi R, Pacella CM, Rhim H, Na DG. Thermal ablation for benign thyroid nodules: radiofrequency and laser. Korean J Radiol. 2011;12:525-540. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 174] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Issa PP, Cironi K, Rezvani L, Kandil E. Radiofrequency ablation of thyroid nodules: a clinical review of treatment complications. Gland Surg. 2024;13:77-86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Xu MH, Dou JP, Guo MH, Yi WQ, Han ZY, Liu FY, Yu J, Cheng ZG, Yu XL, Wang H, Bai N, Wang SR, Yu MA, Liang P, Chen L. Risk factors for recurrent laryngeal nerve injury in microwave ablation of thyroid nodules: A multicenter study. Radiother Oncol. 2024;200:110516. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Mei X, Fu Q, Li G, Ai X, Sun Y, Tian J, Leng X, Jiang S. Clinical study on the impact of microwave ablation energy on the treatment efficacy of benign thyroid nodules. Front Oncol. 2025;15:1568697. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Wu J, Wei Y, Zhao ZL, Cao SL, Li Y, Peng LL, Li SQ, Yu MA. Safety enhancement of improved hydrodissection for microwave ablation in lymph node metastasis from papillary thyroid carcinoma: a comparative study. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2025;16:1594561. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Zhao ZL, Wei Y, Peng LL, Li Y, Lu NC, Wu J, Yu MA. Upgraded hydrodissection and its safety enhancement in microwave ablation of papillary thyroid cancer: a comparative study. Int J Hyperthermia. 2023;40:2202373. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Hu Z, Wang L, Lu M, Yang W, Wu X, Xu J, Zhuang M, Wang S. Protect the recurrent laryngeal nerves in US-guided microwave ablation of thyroid nodules at Zuckerkandl tubercle: a pilot study. BMC Cancer. 2024;24:271. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Garnon J, Cazzato RL, Caudrelier J, Nouri-Neuville M, Rao P, Boatta E, Ramamurthy N, Koch G, Gangi A. Adjunctive Thermoprotection During Percutaneous Thermal Ablation Procedures: Review of Current Techniques. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2019;42:344-357. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Song Y, Wu M, Zhou R, Zhao P, Mao D. Application and evaluation of hydrodissection in microwave ablation of liver tumours in difficult locations. Front Oncol. 2023;13:1298757. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Garnon J, Cazzato RL, Auloge P, Ramamurthy N, Koch G, Gangi A. Adjunctive hydrodissection of the bare area of liver during percutaneous thermal ablation of sub-cardiac hepatic tumours. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2020;45:3352-3360. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Garnon J, Koch G, Caudrelier J, Boatta E, Rao P, Nouri-Neuville M, Ramamurthy N, Cazzato RL, Gangi A. Hydrodissection of the Retrohepatic Space: A Technique to Physically Separate a Liver Tumour from the Inferior Vena Cava and the Ostia of the Hepatic Veins. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2019;42:137-144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Ma Y, Wu T, Yao Z, Zheng B, Tan L, Tong G, Lian Y, Baek JH, Ren J. Continuous, Large-Volume Hydrodissection to Protect Delicate Structures around the Thyroid throughout the Radiofrequency Ablation Procedure. Eur Thyroid J. 2021;10:495-503. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Iñiguez-Ariza NM, Brito JP. Management of Low-Risk Papillary Thyroid Cancer. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul). 2018;33:185-194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Tarasova VD, Tuttle RM. Current Management of Low Risk Differentiated Thyroid Cancer and Papillary Microcarcinoma. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2017;29:290-297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | O'Shea A, Leon D, Arellano RS. Microwave Ablation of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Adjacent to the Esophagus: Value of Hydrodissection for Esophageal Protection. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2023;46:406-407. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Liu C, He J, Li T, Hong D, Su H, Shao H. Evaluation of the efficacy and postoperative outcomes of hydrodissection-assisted microwave ablation for subcapsular hepatocellular carcinoma and colorectal liver metastases. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2021;46:2161-2172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Adebanjo GAR, Bertolotti L, Iemma E, Martini C, Arrigoni F, Ziglioli F, Maestroni U, De Filippo M. Protection from injury to organs adjacent to a renal tumor during Imaging-guided thermal ablation with hydrodissection and pyeloperfusion. Eur J Radiol. 2024;181:111759. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Samadi K, Arellano RS. Ureteral protection during microwave ablation of renal cell carcinoma: combined use of pyeloperfusion and hydrodissection. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2018;24:388-391. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Yamagami T, Yoshimatsu R, Kajiwara K, Yamanishi T, Minamiguchi H, Karashima T, Inoue K. Protection from injury of organs adjacent to a renal tumor during percutaneous cryoablation. Int J Urol. 2019;26:785-790. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Ou D, Chen C, Jiang T, Xu D. Research Review of Thermal Ablation in the Treatment of Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma. Front Oncol. 2022;12:859396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Chen W, Lei J, You J, Lei Y, Li Z, Gong R, Tang H, Zhu J. Predictive factors and prognosis for recurrent laryngeal nerve invasion in papillary thyroid carcinoma. Onco Targets Ther. 2017;10:4485-4491. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Liu YT, Wei Y, Zhao ZL, Wu J, Cao SL, Yu N, Li Y, Peng LL, Yu MA. Thyroid nodule rupture after thermal ablation for benign thyroid nodules: incidence, risk factors, and clinical management. Int J Hyperthermia. 2025;42:2439536. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Melnyk M, Casey RG, Black P, Koupparis AJ. Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocols: Time to change practice? Can Urol Assoc J. 2011;5:342-348. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Parks L, Routt M, De Villiers A. Enhanced Recovery After Surgery. J Adv Pract Oncol. 2018;9:511-519. [PubMed] |

| 35. | Amoako-Tuffour Y, Graham ME, Bullock M, Rigby MH, Trites J, Taylor SM, Hart RD. Papillary thyroid cancer recurrence 43 Years following Total Thyroidectomy and radioactive iodine ablation: a case report. Thyroid Res. 2017;10:8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Bates MF, Lamas MR, Randle RW, Long KL, Pitt SC, Schneider DF, Sippel RS. Back so soon? Surgery. 2018;163:118-123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Li R, Yang L, Xu M, Wu B, Liu Q, An Q, Sun Y, Zhang Y, Liu Y. Current evidence and strategies for preventing tumor recurrence following thermal ablation of papillary thyroid carcinoma. Cancer Imaging. 2025;25:88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Solomon C, Petea-Balea DR, Dudea SM, Bene I, Silaghi CA, Lenghel ML. Role of Ultrasound Elastography and Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound (CEUS) in Diagnosis and Management of Malignant Thyroid Nodules-An Update. Diagnostics (Basel). 2025;15:599. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Lekht I, Gulati M, Nayyar M, Katz MD, Ter-Oganesyan R, Marx M, Cen SY, Grant E. Role of contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) in evaluation of thermal ablation zone. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2016;41:1511-1521. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/