Published online Nov 28, 2025. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v17.i11.113153

Revised: September 3, 2025

Accepted: November 7, 2025

Published online: November 28, 2025

Processing time: 102 Days and 10.5 Hours

The topography between the common carotid artery (CA), internal CA, and external CA (ECA) with the greater horn of the hyoid bone (GHHB) is of parti

To investigate these topographical relationships emphasizing anatomical classification, sexual dimorphism, and clinical significance.

A retrospective study was performed on 224 computed tomography angio

Type 0 (no arterial contact with the GHHB) was the most common configuration (46.9%), followed by type VI (ECA lateral to GHHB, 23.9%) and type VIII (internal CA and ECA lateral to GHHB, 13.2%). Bilateral symmetry was present in 54.02% of cases, mainly in males. Statistically significant sex-based differences were found (P = 0.012), while laterality was not significant (P = 0.779).

Carotid–hyoid topography displays significant anatomical variation with clini

Core Tip: The spatial relationship between the hyoid bone and carotid arteries is highly variable and may predispose patients to vascular compression, stroke, or surgical com

- Citation: Karangeli N, Triantafyllou G, Papadopoulos-Manolarakis P, Arkoudis NA, Velonakis G, Samolis A, Piagkou M. Variations in the spatial relationship between the hyoid bone and the carotid arteries and their clinical significance. World J Radiol 2025; 17(11): 113153

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8470/full/v17/i11/113153.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4329/wjr.v17.i11.113153

A complex interplay of muscular, skeletal, and neurovascular elements defines the anatomy of the head and neck. Among these, the vascular structures exhibit considerable morphological and topographical variability, often with critical implications during diagnostic assessments and surgical interventions[1-6].

The common carotid artery (CCA) bifurcates into the internal carotid artery (ICA) and the external carotid artery (ECA), typically around the C3-C5 vertebral levels. However, this variation can be significant across individuals[7]. The ECA supplies the extracranial tissues of the head and neck, whereas the ICA predominantly serves intracranial structures, including cerebral circulation[8].

During their cervical course, the ICA and ECA exhibit distinct spatial relationships with bony landmarks, including the hyoid bone (HB), styloid process, and mandible. These relationships are not merely anatomical curiosities - they carry potential clinical consequences. Positional anomalies can contribute to vascular compression, altered hemodynamics, or surgical hazards during procedures in the parapharyngeal, retropharyngeal, or suprahyoid spaces[2,9-11]. However, the current literature lacks anatomical classifications and clear linking to clinical symptoms.

Our previous study, based on 100 computed tomography angiography cases, dem

The objective of this radioanatomical study was to examine the topographical relationship between the CAs and the HB in a significantly larger dataset, with a focus on variant classification, sex differences, and potential clinical relevance.

This retrospective study analyzed 224 computed tomography angiography scans archived at the General Hospital of Nikaia-Piraeus, following approval by the institutional ethics committee, approval No. 56485. The sample consisted of 224 patients (161 males and 63 females), aged 20 years to 89 years (mean age, 63.2 years). All scans were acquired using a 128-slice SOMATOM go. Top scanner (Siemens Healthineers), with patients positioned supine and the head in a neutral alignment. A 30% iodine-based contrast medium (60 mL) was administered intravenously at a rate of 4.0-4.5 mL/second. Inclusion criteria were excellent quality of the scan, without pathological processes distorting the anatomy of the area. Scans exhibiting inadequate image quality or anatomical distortion due to pathology (e.g., tumor, trauma, congenital malformations) were excluded, as per the exclusion criteria defined in previous studies[9]. Image processing and analysis were performed using Horos software (Horos Project). Each dataset was reviewed in axial, coronal, and sagittal planes, with additional three-dimensional reconstructions generated for enhanced anatomical assessment.

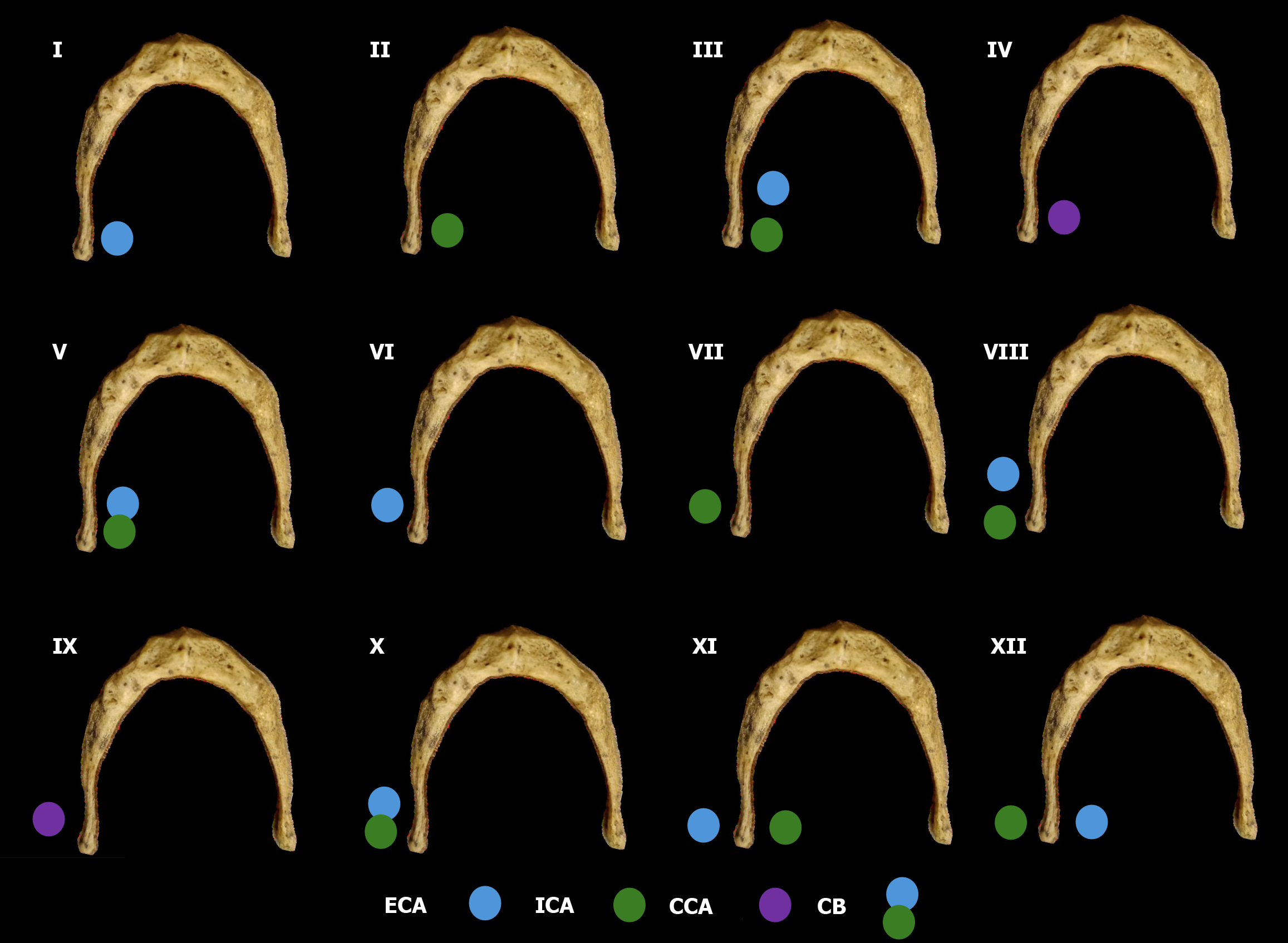

The carotid bifurcation (CB) was first classified as either suprahyoid or infrahyoid, based on its vertical relation to the greater horn of the HB (GHHB) observed in sagittal views. Subsequently, the topographical relationships between the Cas - CCA, ICA, and ECA - and the GHHB were assessed in axial and 3D views. These spatial configurations were cate

Demographic and anatomical data were stratified by side (left vs right) and sex (male vs female). Categorical variables were analyzed using the χ2 test for unpaired comparisons and McNemar’s test for paired variables. All statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics for macOS, Version 29 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States), with a P value < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

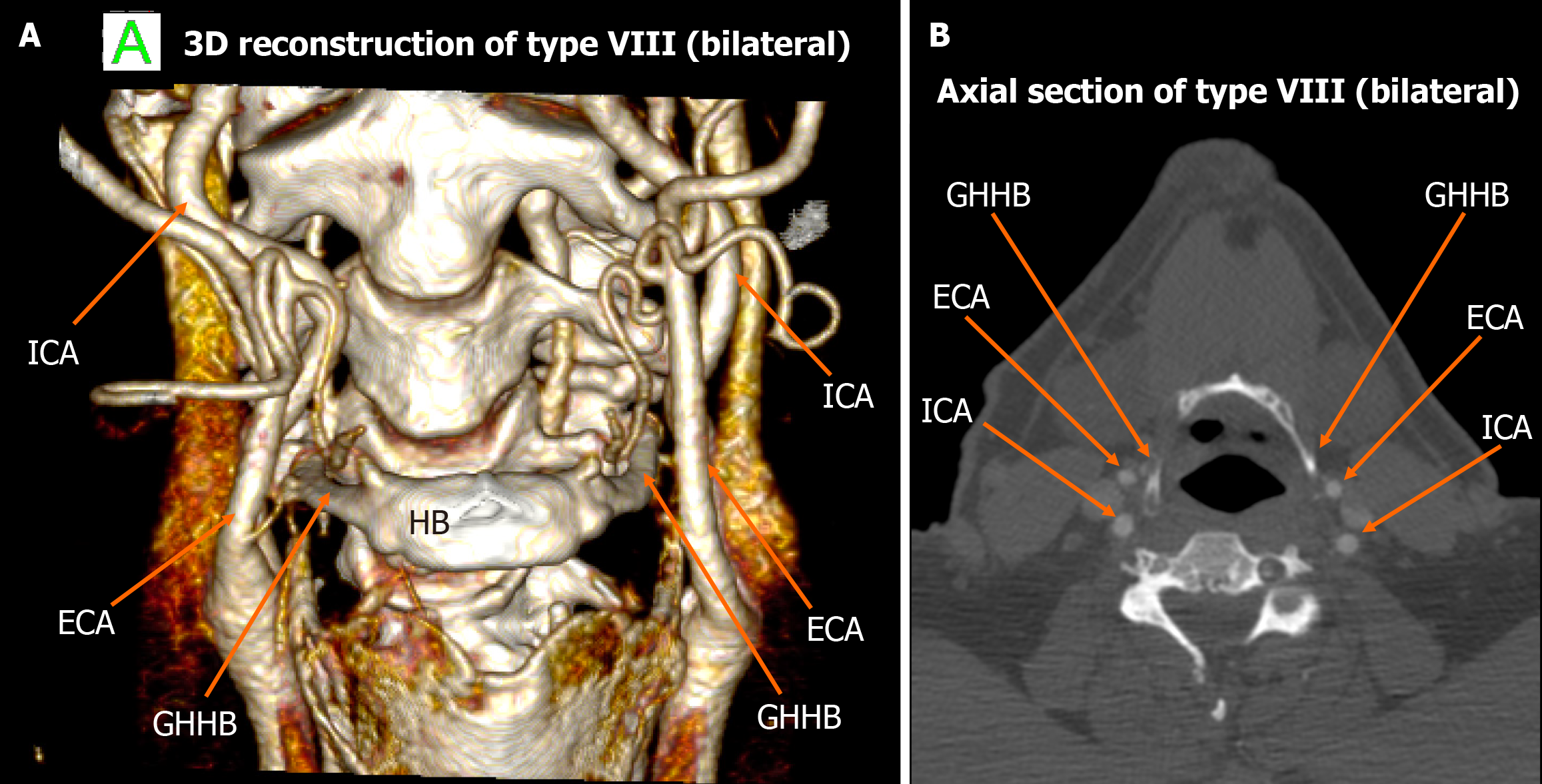

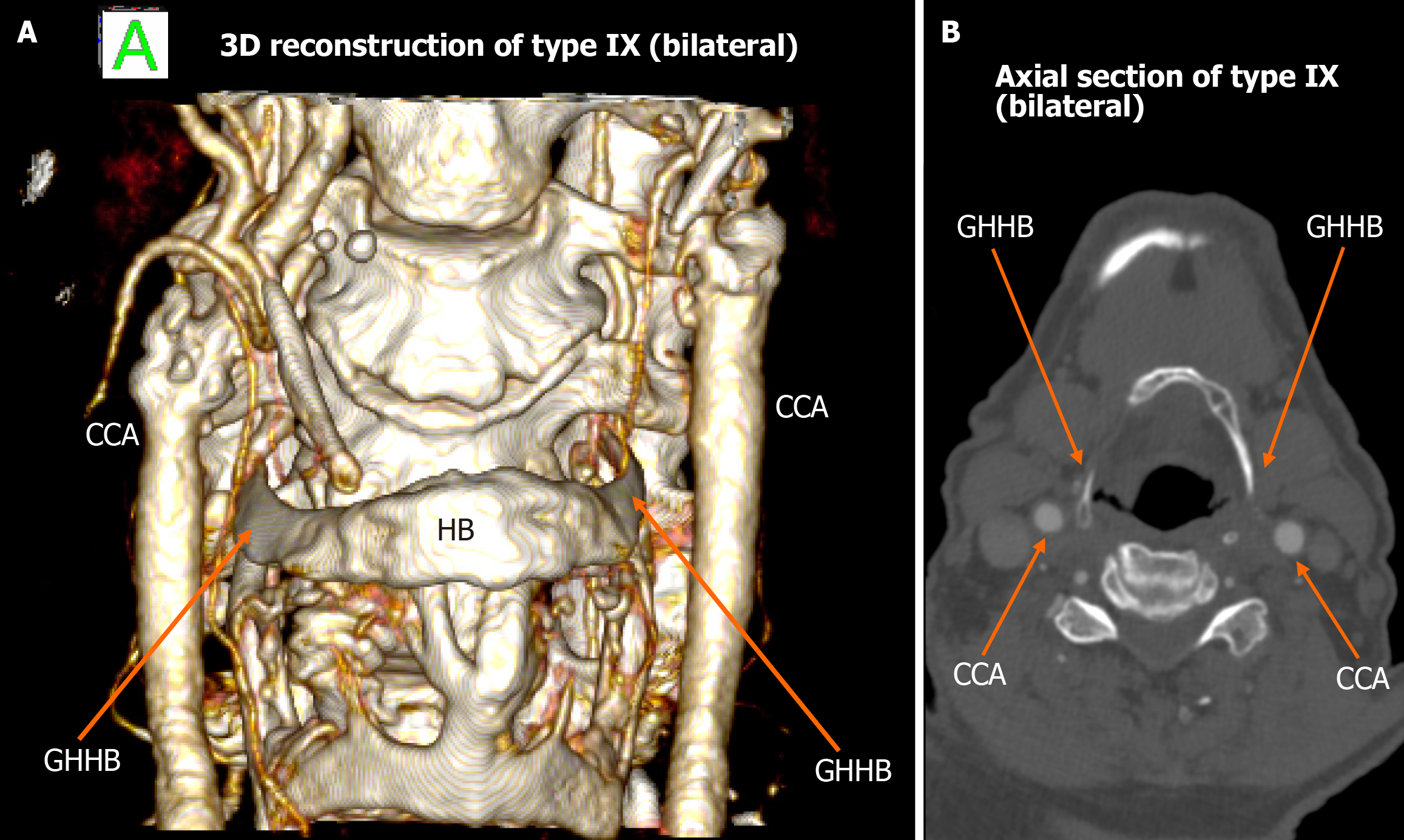

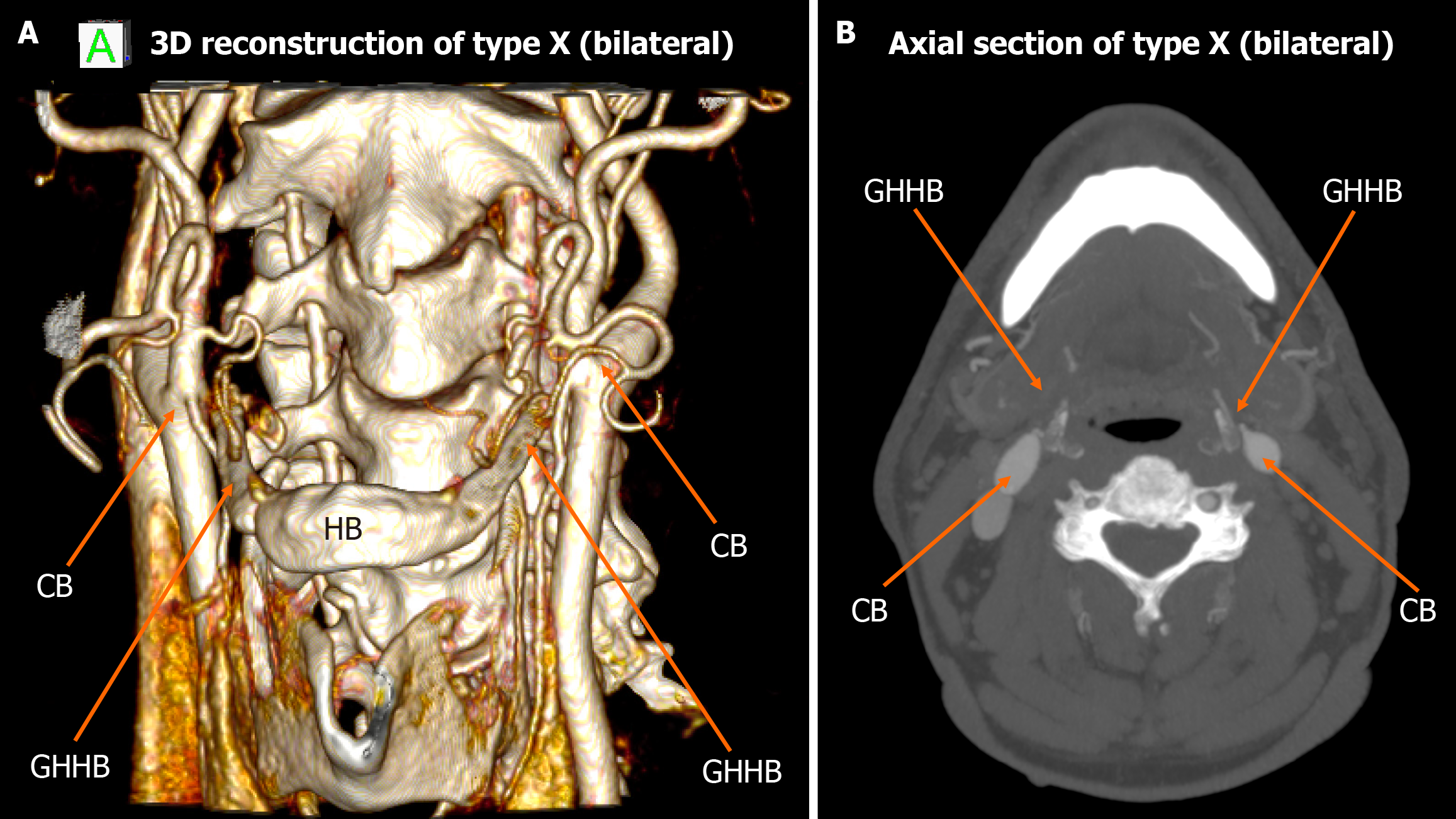

Among the 448 heminecks evaluated (224 patients), 46.9% demonstrated no direct spatial relationship between the CAs and the HB (type 0). All the observed relationships are presented in Figures 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7. The most common non-null configuration was type VI, in which the ECA was lateral to the GHHB, observed in 23.9% of sides (Figure 3). This was followed by type VIII (both ICA and ECA lateral to the GHHB) in 13.2% (Figure 5), and type IX (ICA medial to the GHHB) in 10% (Figure 6). Less frequent configurations included type X (CB lateral to GHHB, 3.6%) (Figure 7), type XI (ECA lateral, ICA medial, 1.1%) (Figure 2), type I (ECA medial, 0.4%) (Figure 1), type XII (ECA medial, ICA lateral, 0.4%) (Figure 4), and type IV (CCA medial, 0.2%) (Figure 2). Types II, III, V, and VII were not observed in this cohort (Table 1).

| Topographical types | Total | Left | Right | P value | Female | Male | P value |

| Type 0 | 210 (46.9) | 107 | 103 | 0.779 | 69 | 141 | 0.012a |

| Type I | 2 (0.4) | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | ||

| Type II | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Type III | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Type IV | 1 (0.2) | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | ||

| Type V | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Type VI | 107 (23.9) | 50 | 57 | 29 | 78 | ||

| Type VII | 1 (0.2) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Type VIII | 59 (13.2) | 28 | 31 | 12 | 47 | ||

| Type IX | 45 (10) | 24 | 21 | 7 | 38 | ||

| Type X | 16 (3.6) | 10 | 6 | 4 | 12 | ||

| Type XI | 5 (1.1) | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | ||

| Type XII | 2 (0.4) | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

Sex- and side-specific distributions depicted the following results: No significant association was found with side laterality (McNemar’s test, P = 0.779); however, sex-based differences were significant (χ2 test, P = 0.012). Males showed higher frequencies of types I, VI, and VIII, whereas females were more likely to present with types 0, IV, and IX through XII.

Analysis of bilateral symmetry revealed that 121 patients (54.02%) exhibited symmetrical carotid-hyoid topography. The most frequent symmetric configuration was bilateral type 0 (70 cases), followed by type VI (31 cases), type VIII (10 cases), type IX (9 cases), and type X (1 case). No bilateral cases were observed for the other configurations.

Bilateral symmetry was notably more common among males. Of the 70 bilateral null-type cases, 46 were male. Similarly, 25 of 31 type VI, 9 of 10 type VIII, and 7 of 9 type IX symmetric cases occurred in male patients. The single bilateral type X case was also male. No bilateral instances of types I, IV, XI, or XII were identified.

When comparing our findings with those reported by Manta et al[2], several notable differences and similarities become apparent. The proportion of null cases in our sample was lower (46.9%) compared to that reported by Manta et al[2] (57.14%), indicating possible variations in population anatomy, imaging protocols, or classification criteria. Both studies identified type VI as the most common anatomical pattern. However, differences emerged, such as the higher frequency of type VIII in our cohort vs its lower ranking in Manta et al[2] dataset. Conversely, types II, III, and V - found in Manta et al[2] study - were not observed in our analysis (Figure 8). These differences may be due to ethnic, geographical, or methodological factors and deserve further investigation across multiple centers (Table 2).

| Topographical types | Anatomical relationship | Current study | Manta et al[2] | Comments |

| Type 0 | Carotid arteries posterior to the tip of the GHHB | 46.9% | 57.14% | Null type |

| Type I | ECA medial to GHHB | 0.4% | 0.34% | Low clinical penetrance, hemodynamically not significant carotid artery compression |

| Type II | ICA medial to GHHB | 0% | 0.34% | Low clinical penetrance, associated with reported cases of TIAs in systemic prothrombotic conditions or repetitive mechanical neck stress situations |

| Type III | Both ICA and ECA medial to GHHB | 0% | 1.02% | Low clinical penetrance, hemodynamically not significant carotid artery compression |

| Type IV | CCA medial to GHHB | 0.2% | 1.02% | Low clinical penetrance, associated with neurological deficits contralateral to the affected vessel in elderly patients |

| Type V | CB medial to GHHB | 0% | 0.34% | Low clinical penetrance, hemodynamically not significant carotid artery compression |

| Type VI | ECA lateral to GHHB | 23.9% | 20.41% | High anatomical prevalence, not implicated in any reported cases of TIA or stroke |

| Type VII | ICA lateral to GHHB | 0.2% | 0% | Low clinical penetrance, hemodynamically not significant carotid artery compression |

| Type VIII | Both ICA and ECA lateral to GHHB | 13.2% | 3.74% | High clinical penetrance, associated with significant neurological symptomatology, including hemiparesis, hemiplegia, aphasia, cervical pain, and loss of somatosensory function |

| Type IX | CCA lateral to GHHB | 10% | 8.5% | Low clinical penetrance, associated with the formation of a carotid pseudoaneurysm |

| Type X | CB lateral to GHHB | 3.6% | 6.46% | Low clinical penetrance, associated with the dissection of a carotid pseudoaneurysm |

| Type XI | ICA medial and ECA lateral to GHHB | 1.1% | 0.34% | High clinical penetrance, involving cases of cryptogenic strokes or unexplained TIAs in younger patients |

| Type XII | ECA medial and ICA lateral to GHHB | 0.4% | 0.34% | Low clinical penetrance, associated with neurological deficits contralateral to the affected vessel in elderly patients |

Sexual dimorphism became a significant factor. Our data revealed statistical differences between male and female distributions, which partially align with Manta et al’s report[2]. The female predominance in types IV, X, and XI, and male dominance in types I, VI, and VIII, support the idea that sex influences vascular topography. However, these sex-related results should be taken into careful consideration due to the sex imbalance of our sample. These patterns suggest hormonal, developmental, or biomechanical effects and require further targeted biomechanical and morphometric research.

We reviewed the current literature for clinical references to carotid-hyoid relationships (Table 2). Several case reports within the existing literature have described a spectrum of carotid-hyoid topographical variants, underscoring both the anatomical intricacy and the potential clinical ramifications of these configurations. Within the reviewed bibliography, documented clinical cases have included two instances of type II, two of type IV, six of type VIII, one of type IX, two of type X, eight of type XI, and one of type XII, as per the classification system[13,14,16-33]. Strikingly, the majority of these cases involved young patients who presented with TIA in the absence of traditional cardiovascular or systemic risk factors, thereby prompting detailed vascular imaging and subsequent identification of atypical carotid-hyoid spatial relationships as potential etiological contributors. The reported TIA symptomatology commonly included hemiparesis affecting the ipsilateral upper and lower limbs, leading clinicians to consider mechanical or dynamic extrinsic arterial compromise in the differential diagnosis[24,31].

Notably, types I, III, V, VI, and VII have not been documented in any clinical case reports to date. This absence may be indicative of low clinical penetrance, or may alternatively reflect a diminished propensity of these configurations to induce hemodynamically significant CA compression. However, the possibility of subclinical or context-dependent risk cannot be excluded, and warrants further investigation - particularly under dynamic conditions such as cervical rotation, swallowing, or phonation.

Of particular interest is type VI, which emerged as the most frequently encountered non-null configuration in both our dataset and that of Manta et al[2]. Despite its high anatomical prevalence, type VI has not been implicated in any reported cases of TIA or stroke, suggesting that this configuration may be inherently benign with respect to cerebrovascular compromise. One possible explanation for the clinical silence of type VI is that the lateral positioning of the ECA relative to the HB places it at lower risk of compression during swallowing or cervical motion, compared to medial or combined medial-lateral configurations. This apparent paradox between anatomical frequency and clinical silence raises important considerations regarding the threshold at which spatial proximity translates into pathological interaction, and highlights the need for functional imaging studies and longitudinal clinical correlation to distinguish anatomical variants of no consequence from those with latent pathogenic potential[2].

In the context of type II carotid-hyoid configurations, where the ICA lies medial to the GHHB, both published case reports to date involve young female patients, highlighting a possible sex- and age-related anatomical susceptibility[16,17]. Tokunaga et al[17] reported a patient with transient left hemiparesis and ipsilateral sensory disturbance, in the setting of underlying Sjögren’s syndrome. Dynamic carotid ultrasonography revealed positional displacement of the right ICA, with significant shifts observed during head rotation and deglutition, implicating a mechanical interaction between the HB and the CA. In a separate report, Kho et al[16] described a young female patient who, in addition to transient hemiparesis and sensory deficits, exhibited dysphagia. Following vascular imaging, the aberrant medial positioning of the ICA relative to the HB was identified. Notably, symptom onset was temporally associated with a behavioral habit of frequent, rapid side-to-side cervical movements described as “neck clicking”. This repetitive mechanical motion likely exacerbated dynamic ICA compression, resulting in neurological symptoms attributable to transient arterial insufficiency or microembolism. Together, these cases underscore the clinical relevance of type II configurations, particularly when compounded by systemic prothrombotic conditions or repetitive mechanical neck stress, and suggest that even anatomically rare variants may have significant cerebrovascular implications under specific dynamic or behavioral circumstances.

In cases of type IV carotid-hyoid configuration, wherein the CCA is positioned medially to the GHHB, the literature documents two clinically significant cases, both involving 70-year-old individuals who presented with neurological deficits contralateral to the affected vessel, and in both instances, pathology was localized to the right CCA[13,18]. In the first case, the patient exhibited mild left-sided hemiparesis with preserved sensory function but demonstrated disorientation to place, attributed to a 90% stenosis of the right CCA[18]. In the second report, the patient presented with left-sided hemiplegia accompanied by motor aphasia. Imaging revealed an unstable atherosclerotic plaque within the right CCA, presumed to be the source of embolic eve. These cases suggest that the type IV anatomical configuration may predispose the CCA to mechanical stress or compression, potentially contributing to plaque instability and subsequent cerebrovascular ischemia. Although direct causality remains speculative, the medial displacement of the CCA relative to the hyoid apparatus may represent a contributory factor in cases of otherwise unexplained common carotid pathology, particularly in elderly patients[13,18].

In the context of type VIII carotid-hyoid configuration, where both the external and internal CAs (ECA and ICA, respectively) are positioned lateral to the GHHB, multiple case reports have documented significant neurological symptomatology, including hemiparesis, hemiplegia, aphasia, cervical pain, and loss of somatosensory function. These events are frequently attributed to TIAs, potentially precipitated by dynamic vascular compression during cervical movement or elevated intrathoracic pressure[19,23]. Behavioral and lifestyle factors appear to play a contributory role in some of these cases. Notably, activities such as heavy weightlifting and golfing - which involve abrupt or repetitive cervical rotation and strain - have been associated with the onset of TIA symptoms in patients exhibiting type VIII anatomy[20,22]. In one case, the ICA entrapment observed in conjunction with type VIII was exacerbated by both an elongated GHHB and a coexisting elongated styloid process, although the styloid-hyoid complex appeared to be the principal mechanical factor in arterial compromise[20]. In our study, type VIII was observed in 13.2% of cases, making it one of the most prevalent non-null configurations. Given both its relatively high frequency in the general population and its documented association with symptomatic cases in the literature, this variant should raise clinical caution, especially in patients presenting with unexplained cerebrovascular symptoms.

Schneider et al[25] reported a case of carotid pseudoaneurysm formation associated with a type IX carotid-hyoid configuration, characterized by lateral displacement of the CCA relative to the GHHB. The patient was asymptomatic but presented with a palpable cervical mass, prompting further vascular imaging. The investigation revealed that the chronic mechanical irritation of the arterial wall - due to its close spatial relationship with the GHHB - had likely contributed to localized inflammation and subsequent pseudoaneurysm development. The patient’s history of heavy weightlifting was identified as a potential exacerbating factor, amplifying repetitive microtrauma at the site of arterial-bony contact.

Type X carotid-hyoid configurations, in which the CB is positioned laterally to the GHHB, have been implicated in clinically relevant vascular pathology. Ye et al[27] described a case involving a patient who presented with right-sided hemiparesis, in whom imaging revealed two cystic lesions with internal calcifications and a pronounced spatial proximity between the GHHB and the ICA. A dissecting aneurysm of the ICA was identified, which the authors attributed to mechanical stress and chronic irritation associated with an elongated HB abutting the arterial wall[2].

Type XI carotid-hyoid configurations, characterized by the ECA positioned laterally and the ICA medially to the GHHB, appear to be the most frequently represented anatomical variant in the published clinical literature concerning TIAs. All reported cases have presented with classic focal neurological deficits[14,26,28-32]. Importantly, these cases span a wide age range, with several involving young adults lacking conventional cardiovascular risk factors, thereby con

Notably, in the majority of these reports, the CB was found to be situated lower than its typical anatomical location - often at the C3-C4 vertebral level or below. Given both the frequency of type XI in symptomatic individuals and the potential for recurrent or unexplained cerebrovascular events, this configuration warrants heightened clinical attention, particularly in cases of cryptogenic stroke or unexplained TIAs in younger patients[14,31]. Keshelava et al[32] doc

A nuanced understanding of the medial vs lateral displacement of the CAs relative to the GHHB is essential for pre

In contrast, types VI-X, characterized by lateral displacement of the carotid vessels, present a different set of challenges. The close spatial relationship between the arteries and the sternocleidomastoid muscle, as well as deeper structures like the posterior belly of the digastric and stylopharyngeus muscles, may lead to increased arterial compression during dynamic head and neck motion and can complicate transcervical surgical approaches to parapharyngeal or retro

Finally, aberrant courses of the CAs should always be included in the differential diagnosis of submucosal oropha

The current study is limited by its moderate sample size and sex imbalance. Additionally, our findings are based on a single-center cohort and may not apply universally. The sex imbalance could have affected our sample and the statistically significant difference identified between female and male patients. Due to the retrospective and anatomical nature of the present study, the patients’ medical history was unknown. Future research should include larger, multicenter, and demographically diverse groups. Incorporating dynamic imaging, functional testing, and long-term clinical follow-up would help better define the accurate risk profile of each topographical variant, while biomechanical and genetic studies will enhance our knowledge for sex- and nationality-based differences.

This study highlights the significant diversity of carotid-hyoid relationships and identifies specific spatial patterns with clear clinical implications. Using the classification system of Manta et al[2], we confirmed that type VI is the most common non-null variant; however, its apparent clinical silence contrasts with the pathological potential of less frequent configurations, such as types VIII and XI, which have been linked to TIA s and other vascular complications. Our findings also demonstrate pronounced sexual dimorphism and lateral asymmetry, highlighting the importance of personalized anatomical assessment evaluation. Carotid variants that are displaced medially increase surgical risk, especially in transoral and pharyngeal procedures, while lateralized types may lead to dynamic arterial compression or complicate cervical access routes. Including carotid-hyoid topographical assessment in routine preoperative imaging and clinical decision-making can help prevent iatrogenic injury, improve diagnostic accuracy in cryptogenic stroke, and enhance surgical planning.

| 1. | Paulsen F, Tillmann B, Christofides C, Richter W, Koebke J. Curving and looping of the internal carotid artery in relation to the pharynx: frequency, embryology and clinical implications. J Anat. 2000;197 Pt 3:373-381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 160] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Manta MD, Rusu MC, Hostiuc S, Vrapciu AD, Manta BA, Jianu AM. The Carotid-Hyoid Topography Is Variable. Medicina (Kaunas). 2023;59:1494. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Rusu MC, Tudose RC, Vrapciu AD, Popescu ŞA. Lowered hyoid bone overlapping the thyroid cartilage in CT angiograms. Surg Radiol Anat. 2024;46:333-339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Dumitru CC, Vrapciu AD, Jianu AM, Hostiuc S, Rusu MC. The retromandibular loop of the external carotid artery. Ann Anat. 2024;253:152226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Triantafyllou G, Paschopoulos I, Duparc F, Tsakotos G, Tsiouris C, Olewnik Ł, Georgiev G, Zielinska N, Piagkou M. The superior thyroid artery origin pattern: A systematic review with meta-analysis 2024 Preprint. Available from: bioRxiv: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-4557932/v1. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 6. | Triantafyllou G, Vassiou K, Duparc F, Vlychou M, Paschopoulos I, Tsakotos G, Tudose RC, Rusu MC, Piagkou M. The lingual and facial arteries' common origin: a systematic review with meta-analysis and a computed tomography angiography study. Surg Radiol Anat. 2024;46:1937-1947. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Manta MD, Rusu MC, Hostiuc S, Tudose RC, Manta BA, Jianu AM. The vertical topography of the carotid bifurcation - original study and review. Surg Radiol Anat. 2024;46:1253-1263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Standring S, Anand N, Birch R, Collins P, Crossman A, Gleeson M, Jawaheer G, Smith A, Spratt J, Stringer M, Tubbs S, Tunstall R, Wein A, Wigley C. Gray's Anatomy: the anatomical basis of clinical practice. 41st ed. London: Elsevier, 2015. |

| 9. | Karangeli N, Triantafyllou G, Duparc F, Vassiou K, Vlychou M, Tsakotos G, Piagkou M. Retrostyloid and retromandibular courses of the external carotid artery. Surg Radiol Anat. 2024;47:23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Triantafyllou G, Botis G, Vassiou K, Vlychou M, Tsakotos G, Kalamatianos T, Matsopoulos G, Piagkou M. Τhe styloid process length and the stylohyoid chain ossification affect its relationship with the carotid arteries. Ann Anat. 2025;257:152342. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Triantafyllou G, Papadopoulos-Manolarakis P, Vassiou K, Vlychou M, Karangeli N, Papanagiotou P, Tsakotos G, Piagkou M. The impact of the styloid process angulation on the carotid arteries. Ann Anat. 2025;258:152378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Karangeli N, Triantafyllou G, Papadopoulos-Manolarakis P, Tsakotos G, Vassiou K, Vlychou M, Papanagiotou P, Piagkou M. The Anatomical Relationship Between the Hyoid Bone and the Carotid Arteries. Diagnostics (Basel). 2025;15:1485. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Suematsu T, Kawabata S, Nishikawa Y, Hirai N, Nakamura M, Terada E, Kajikawa R, Tsuzuki T. Mechanical compression of the carotid artery by the pharynx in the retropharyngeal space during swallowing and the induction of stenosis and embolic stroke: illustrative case. J Neurosurg Case Lessons. 2024;8:CASE2483. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 14. | Mutimer CA, Campbell BCV. Thromboembolism From Hyoid Bone-Related Direct Carotid Artery Compression. Stroke. 2024;55:e157-e158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Bouille F, De Malherbe M, Pico F. Ischemic Stroke Due to Compression of a Wandering Internal Carotid Artery by the Hyoid Bone. JAMA Neurol. 2025;82:303-304. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kho LK, Bates TR, Thompson A, Dharsono F, Prentice D. Cerebral embolism and carotid-hyoid impingement syndrome. J Clin Neurosci. 2019;64:27-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Tokunaga K, Uehara T, Kanamaru H, Kataoka H, Saito K, Ishibashi-Ueda H, Shobatake R, Yamamoto Y, Toyoda K. Repetitive Artery-to-Artery Embolism Caused by Dynamic Movement of the Internal Carotid Artery and Mechanical Stimulation by the Hyoid Bone. Circulation. 2015;132:217-219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Abdelaziz OS, Ogilvy CS, Lev M. Is there a potential role for hyoid bone compression in pathogenesis of carotid artery stenosis? Surg Neurol. 1999;51:650-653. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Mori M, Yamamoto H, Koga M, Okatsu H, Shono Y, Toyoda K, Fukuda K, Iihara K, Yamada N, Minematsu K. Hyoid bone compression-induced repetitive occlusion and recanalization of the internal carotid artery in a patient with ipsilateral brain and retinal ischemia. Arch Neurol. 2011;68:258-259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Renard D, Freitag C. Hyoid-related internal carotid artery dissection. J Neurol. 2012;259:2501-2502. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Renard D, Rougier M, Aichoun I, Labauge P. Hyoid bone-related focal carotid vasculopathy. J Neurol. 2011;258:1540-1541. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Hong JM, Kim TJ, Lee JS, Lee JS. Neurological picture. Repetitive internal carotid artery compression of the hyoid: a new mechanism of golfer's stroke? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2011;82:233-234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Yukawa S, Yamamoto S, Hara H. Carotid artery dissection associated with an elongated hyoid bone. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2014;23:e411-e412. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | González Villaman CM, Domínguez Quiñónez R, Castillo Espinal L. Internal carotid artery dissection associated with an elongated hyoid bone in a patient with vascular Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. BMJ Case Rep. 2024;17:e260764. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Schneider CG, Kortmann H. Pseudoaneurysm of the common carotid artery due to ongoing trauma from the hyoid bone. J Vasc Surg. 2007;45:186-187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Liu S, Nezami N, Dardik A, Nassiri N. Hyoid bone impingement contributing to symptomatic atherosclerosis of the carotid bifurcation. J Vasc Surg Cases Innov Tech. 2020;6:89-92. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Ye Q, Liu Y, Tang H, Zhou Q, Zhang H, Liu H. Hyoid bone compressioninduced carotid dissecting aneurysm: A case report. Exp Ther Med. 2023;26:551. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Kölbel T, Holst J, Lindh M, Mätzsch T. Carotid artery entrapment by the hyoid bone. J Vasc Surg. 2008;48:1022-1024. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Martinelli O, Fresilli M, Jabbour J, Di Girolamo A, Irace L. Internal Carotid Stenosis Associated with Compression by Hyoid Bone. Ann Vasc Surg. 2019;58:379.e1-379.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Plotkin A, Bartley MG, Bowser KE, Yi JA, Magee GA. Carotid Artery Entrapment by the Hyoid Bone-A Rare Cause of Recurrent Strokes in a Young Patient. Ann Vasc Surg. 2019;57:48.e7-48.e11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Bicevska K, Skrastina S, Kupcs K, Raita A, Balodis A. Functional Compression of the Right Internal Carotid Artery by the Hyoid Bone in a Patient with Moyamoya Syndrome and Low Internal Carotid Artery Bifurcation: A Case Report. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2025;21:383-389. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Keshelava G, Robakidze Z. Internal Carotid Artery Stenosis and Entrapment by the Hyoid Bone. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2024;68:422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Keshelava G, Robakidze Z, Tsiklauri D. External Carotid Artery Entrapment by the Hyoid Bone Associated with an Atherosclerotic Stenosis of the Internal Carotid Artery. Diseases. 2024;12:258. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Bernardes MND, Cascudo NCM, El Cheikh MR, Gonçalves VF, Lamounier P, Ramos HVL, Costa CC. Aberrant common and internal carotid arteries and their surgical implications: a case report. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2021;87:366-369. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Baba A, Kurokawa R, Kayama R, Tsuneoka Y, Kurokawa M, Ota Y, Suzuki T, Yamauchi H, Matsushima S, Ojiri H. A rare case of positional changes of carotid artery depicted within a single MR study and a wandering carotid artery depicted on a serial MR studies. Radiol Case Rep. 2022;17:50-53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/