Published online Aug 28, 2023. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v15.i8.250

Peer-review started: June 16, 2023

First decision: July 19, 2023

Revised: July 23, 2023

Accepted: July 31, 2023

Article in press: July 31, 2023

Published online: August 28, 2023

Processing time: 68 Days and 22.1 Hours

Abernethy malformation is a rare congenital vascular malformation with a portosystemic shunt that may clinically manifest as cholestasis, dyspnea, or hepatic encephalopathy, among other conditions. Early diagnosis and classification are very important to further guide treatment. Typically, patients with congenital portosystemic shunts have no characteristics of portal hypertension. Herein, we report an 18-year-old female with prominent portal hypertension that manifested mainly as rupture and bleeding of esophageal varices. Imaging showed a thin main portal vein, no portal vein branches in the liver, and bleeding of the esophageal and gastric varices caused by the collateral circulation upwards from the proximal main portal vein. Patients with Abernethy malformation type I are usually treated with liver transplantation, and patients with type II are treated with shunt occlusion, surgery, or transcatheter coiling. Our patient was treated with endoscopic surgery combined with drug therapy and had no portal hypertension and good hepatic function for 24 mo of follow-up.

This case report describes our experience in the diagnosis and treatment of an 18-year-old female with Abernethy malformation type IIC and portal hypertension. This condition was initially diagnosed as cirrhosis combined with portal hypertension. The patient was ultimately diagnosed using liver histology and subsequent imaging, and the treatment was highly effective. To publish this case report, written informed consent was obtained from the patient, including the attached imaging data.

Abernethy malformation type IIC may develop portal hypertension, and traditional nonselective beta-blockers combined with endoscopic treatment can achieve high efficacy.

Core Tip: Abernethy malformation is a rare congenital vascular malformation with portosystemic shunts that may clinically manifest as cholestasis, dyspnea, or hepatic encephalopathy, among other conditions. Typically, patients with congenital portosystemic shunts have no characteristics of portal hypertension. We reported an 18-year-old woman with Abernethy malformation type II and portal hypertension. This condition was initially diagnosed as cirrhosis combined with portal hypertension. The patient was ultimately diagnosed by liver puncture and biopsy with subsequent imaging.

- Citation: Yao X, Liu Y, Yu LD, Qin JP. Rare portal hypertension caused by Abernethy malformation (Type IIC): A case report. World J Radiol 2023; 15(8): 250-255

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8470/full/v15/i8/250.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4329/wjr.v15.i8.250

Among patients accompanied by portal hypertension, Esophageal variceal bleeding is a frequent complication. However, although the prevalence of Abernethy malformation is approximately 1 in 30000–50000 people[1], and it typically presents no characteristics of portal hypertension, this congenital occult disease should not be ignored in clinical practice. As imaging studies have progressed, the diagnosis of Abernethy malformation has increased. The shunts of Abernethy malformation type II most often occur in the main portal vein (MPV) and in the mesenteric, gastric, and splenic veins[2]. To date, no reports have described the shunt entering the splenic hilum through the splenic vein and establishing collateral circulation, which then enters the inferior vena cava (IVC) through the splenorenal shunt. In addition, this patient developed portal hypertension, which was treated effectively.

An 18-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital with a 10-d history of left upper abdominal distension, pain, and discomfort, accompanied by hematemesis.

The patient had no history of present illness.

The patient had no history of past illness.

The patient had no special personal history or family history.

Physical examination showed no abnormalities, except for the spleen palpable 2 cm below the left costal margin.

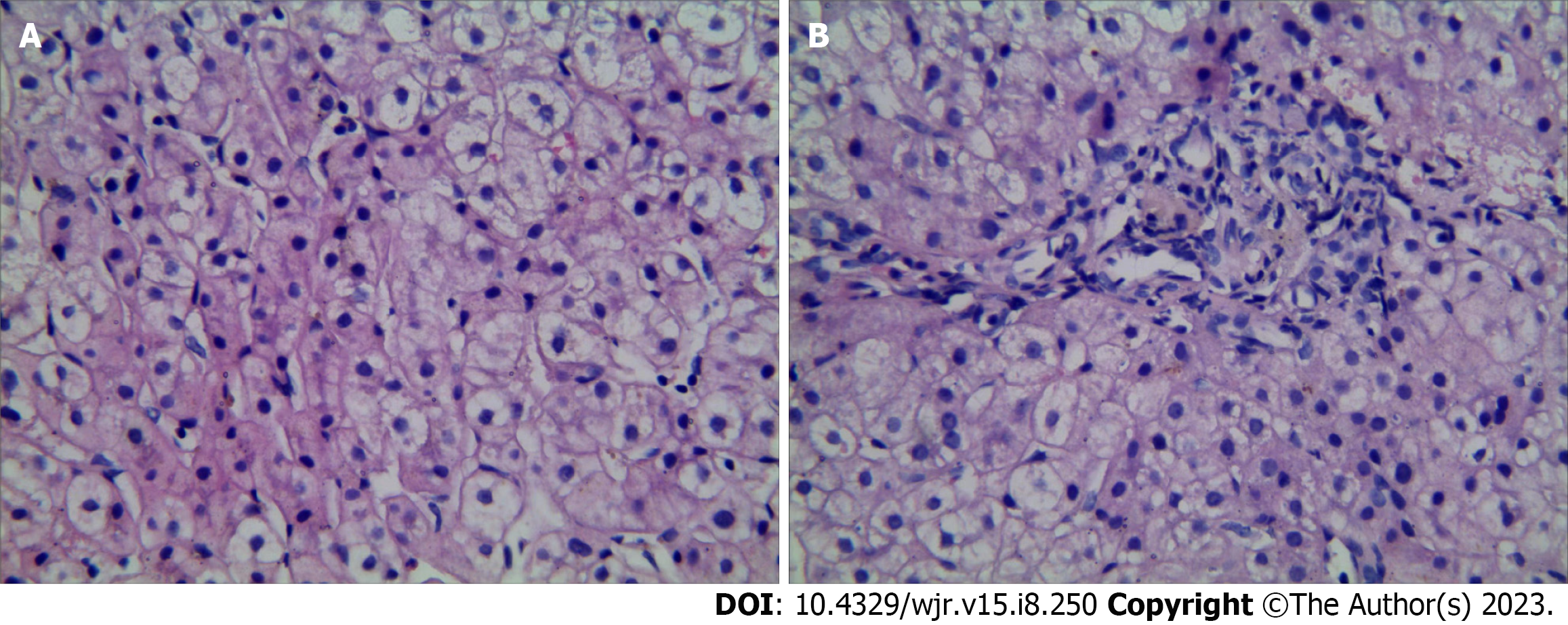

On routine blood tests, the hematocrit was 25.6%, the hemoglobin concentration was 73 g/L, the red blood cell count was 3.71 × 1012/L, the platelet count was 152 × 109/L, and the white blood cell count was 1.31 × 109/L. The results of laboratory examinations were Child–Pugh grade A liver function. Test results for hepatitis and autoimmune antibodies were negative. Ceruloplasmin was normal. Bone marrow (BM) smear displayed active proliferation of karyocytes, with 59% granulocytes and 22% erythroid cells (granulocytes/erythroid cell ratio of 2.68); most of the mature red blood cells were expanded in the central light-stained area. Active proliferation of BM tissue was shown on BM puncture and biopsy without other special changes. Punctured hepatic tissue. The structure of hepatic lobules was normal, the hepatic sinusoids were not dilated, the diameter of the central vein was generally normal, and the hepatic parenchyma had no obvious inflammatory changes. No portal vein branch entering the hepatic lobule was detected. The number and shape of small bile ducts in the portal area were normal, and the stroma was infiltrated by a small number of chronic inflammatory cells (Figure 1).

Colonoscopy suggested no abnormalities. Gastroscopy revealed severe esophageal varices (type G1OV1). Further imaging with 320-detector row computed tomography (CT) angiography and three-dimensional (3D) reconstruction of the portal vein showed a thin MPV, no portal vein branch in the liver, disordered vessels at the proximal MPV, and esophageal varices caused by collateral circulation upwards at the origin of the portal vein. The superior mesenteric vein and the splenic vein formed a common trunk. After entering the splenic hilum, the splenic vein formed collateral circulation along the lower left side of the vertebral body, resulting in a venous tumor thrombus, and then flowed into the renal vein and returned to the IVC (Figure 2). Ultrasound of the portal vein showed no portal vein branch in the liver, a thin MPV with blood flow, no thrombosis or cavernous transformation, reversed blood flow in the splenic vein, and thickened hepatic arteries suspected to be compensation. Cardiac ultrasound showed no abnormalities.

Abernethy malformation type IIC: Portal hypertension.

Patients with Abernethy malformation type II can be treated with shunt occlusion and liver transplantation, and the patient selected conservative treatment. After the first endoscopic ligation of esophageal varices, endoscopic treatment was carried out 3 consecutive times at an interval of 1 mo. Simultaneously, 10 mg of oral propranolol hydrochloride was given 3 times/d. The heart rate was controlled at approximately 55 times/min.

Three months later, gastroscopy indicated esophageal varices (mild, RC-) and a local scar after ligation. Thus, 2.5 mg of warfarin per day was administered. The patient was followed up for 24 consecutive months and showed no portal hypertension and Child–Pugh grade A.

John Abernethy first reported Abernethy malformation, also known as a congenital extrahepatic portosystemic shunt, in 1793. Abernethy malformation is a rare clinical disease with a prevalence of one case out of 30000–50000[1]. It is characterized by the absence or dysplasia of the portal vein caused by abnormal development of fetal umbilical veins and vitelline veins, with abnormal shunts between the portal vein system and the vena cava system[3]. In 1994, Morgan et al[2] defined Abernethy malformation type I as the absence of portal vein flow in the liver caused by the congenital absence of the portal vein. Abernethy malformation type II was defined as a significant reduction in intrahepatic blood flow caused by a thin MPV. In type I Abernethy malformation patients, the superior mesenteric vein does not merge with the splenic vein, and merging of the superior mesenteric vein with the splenic vein is classified as type Ib. In 2011, Lautz et al[4] classified patients with congenital portal vein dysplasia into type IIa (shunt occurring in the left or right portal vein of the liver, including patent ductus venosus), type IIb (shunt occurring in the MPV), and type IIc (shunt occurring in the mesenteric veins, gastric veins, or splenic veins) based on the different anatomical positions of the portosystemic shunts. However, this classification method includes patients with congenital intrahepatic portosystemic shunts and is not widely used.

The clinical manifestations of Abernethy malformation vary greatly, from incidental detection to hepatoencephalopathy and hepatic failure, and depend on the type of abnormality. Patients may be asymptomatic or present with nonspecific symptoms, such as hypergalactosemia, hyperbilirubinemia, and hyperammonemia, due to delayed metabolism of these metabolites in the liver or their metabolism outside of the liver[5,6]. Abernethy malformation may also cause pulmonary venous congestion, leading to hepatopulmonary syndrome, which manifests as dyspnea caused by pulmonary hypertension and even syncope[7]. In addition, Abernethy malformation can be complicated by multiple malformations[2], such as congenital heart disease, skeletal muscle system malformations, and polysplenia. When patients visit with symptoms, including dyspnea and varicose veins of the lower limbs[8], misdiagnosis or missed diagnosis is likely. This patient was admitted due to rupture and bleeding of esophageal varices, which is easily misdiagnosed as cirrhotic portal hypertension accompanied by cavernous transformation of the portal vein. Hepatobiliary abnormalities, such as cirrhosis, veno-occlusive disease, noncirrhotic portal fibrosis, and biliary atresia, were excluded based on the percutaneous liver biopsy. A BM smear and biopsy excluded hematological system-related diseases. The thin portal vein and no portal vein branches in the liver indicated Abernethy malformation. However, CT showed a similar cavernous transformation at the proximal portal vein, so Abernethy malformation needed to be differentiated from extrahepatic portal vein obstruction-related diseases.

Imaging is the preferred diagnostic method for Abernethy malformations. Abdominal ultrasound can be used as a preliminary screening tool. Portal vein CT angiography and 3D reconstruction can help identify abnormal development of the portal vein and the anatomy of extrahepatic shunts in Abernethy malformations. Webb et al[9] described the ultrasound display of the portal vein in Abernethy malformations as an intact empty hepatic hilum with portal vein block appearing as a wide, rhombic high-level echo band. Patients with congenital portosystemic shunts do not have characteristics of portal hypertension, such as splenomegaly, varicosity, and collateral branches[10]. A recent study[11] suggested that acquired extrahepatic portosystemic shunts are usually detected in patients with cirrhosis. In addition, noncirrhotic portal vein thrombosis may also present manifestations similar to Abernethy malformation. In this patient, an ultrasound of the portal vein showed no portal vein branches in the liver, thrombosis, or cavernous transformation but showed thin MPV with visible blood flow signals and reversed blood flow in the splenic vein. Although the CT of this patient showed a similar cavernous transformation in the MPV, the author’s team believes that extrahepatic portal vein obstruction caused by chronic thrombosis and cavernous transformation of the portal vein was excluded by ultrasound. No shunt between the portal vein and the splenic vein was detected, but after entering the splenic hilum, the blood flowed back to the IVC in the form of a thick “spleen kidney” shunt through the collateral circulation, which is different from the usual form of Abernethy syndrome and may be another manifestation of Abernethy malformation type IIC. Several studies[12,13] showed that various congenital malformations are related to Abernethy malformation, and cardiac abnormalities are the most common. This patient presented with no abnormalities on cardiac ultrasound, so cardiac malformations could be excluded. We speculate that this patient may have a congenital hypoplastic portal vein system. Because of the thin MPV and no portal vein branch, the “splenorenal communicating branch” that should degenerate during development continued to exist chronically. The blood flow returning to the liver was blocked at the portal vein origin, forming regional portal hypertension (consistent with the appearance of abundant capillary collateral circulation around the MPV origin on CT, which is similar to cavernous transformation). In addition, the blood flow of the splenic vein was reversed, causing splenic congestion and swelling, and then returned to the IVC through the splenic-renal communicating branch.

Hepatic damage in patients with Abernethy malformations is milder than the damage in patients with cirrhosis, and the increases in bilirubin and aminopherase are often not obvious[14]. This patient’s hepatic function was normal, with no hepatic encephalopathy, which is in line with previous research results[5,15]. Most patients with Abernethy malformations have elevated blood ammonia, but fewer patients present with hepatic encephalopathy. Although the thin portal vein may lead to insufficient blood flow to the liver, the hepatic artery may play a compensatory role in the long-term course of the disease, which is consistent with hepatic artery thickening on portal ultrasound and compensatory performance.

Liver transplantation is the main treatment method for Abernethy malformation type I. Patients with Abernethy malformation type II are treated with shunt occlusion and liver transplantation[6,16]. The choice of an interventional or surgical method is based on the degree of extrahepatic portosystemic shunts, the anatomical position of shunts, and the diameter of the shunts. The liver tumors, hepatopulmonary syndrome, and hyperammonemia disappear after the occlusion of the abnormal shunts[4,15]. Portal hypertension caused by Abernethy malformation has not been reported; thus, we first recommended liver transplantation for this patient, and the patient finally chose conservative treatment. Endoscopic ligation may aggravate portal hypertension, slow portal vein blood flow, and form thrombi[17]. Therefore, nonselective beta-blockers and anticoagulant drugs were added. After 24 mo of follow-up, the patient presented with no complications of portal hypertension or portal thrombosis and good hepatic function. We will continue to monitor this patient.

Abernethy malformation type IIC may cause portal hypertension, and combining traditional nonselective beta-blockers with endoscopic therapy is an effective treatment.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Ghazanfar A, United Kingdom; Pizanias M, United Kingdom S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhao S

| 1. | Abernethy J. Account of Two Instances of Uncommon Formation in the Viscera of the Human Body: From the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Med Facts Obs. 1797;7:100-108. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Morgan G, Superina R. Congenital absence of the portal vein: two cases and a proposed classification system for portasystemic vascular anomalies. J Pediatr Surg. 1994;29:1239-1241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 318] [Cited by in RCA: 304] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Peček J, Fister P, Homan M. Abernethy syndrome in Slovenian children: Five case reports and review of literature. World J Gastroenterol. 2020;26:5731-5744. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Lautz TB, Tantemsapya N, Rowell E, Superina RA. Management and classification of type II congenital portosystemic shunts. J Pediatr Surg. 2011;46:308-314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ponziani FR, Faccia M, Zocco MA, Giannelli V, Pellicelli A, Ettorre GM, De Matthaeis N, Pizzolante F, De Gaetano AM, Riccardi L, Pompili M, Rapaccini GL. Congenital extrahepatic portosystemic shunt: description of four cases and review of the literature. J Ultrasound. 2019;22:349-358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Uchida H, Sakamoto S, Kasahara M, Kudo H, Okajima H, Nio M, Umeshita K, Ohdan H, Egawa H, Uemoto S; Japanese Liver Transplantation Society. Longterm Outcome of Liver Transplantation for Congenital Extrahepatic Portosystemic Shunt. Liver Transpl. 2021;27:236-247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Lin XQ, Rao JY, Xiang YF, Zhang LW, Cai XL, Guo YS, Lin KY. Case Report: A Rare Syncope Case Caused by Abernethy II and a Review of the Literature. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021;8:784739. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Wang W, Li Q, Wen L. An Unusual Cause of Left Lower Extremity Varicose Veins. Gastroenterology. 2022;162:e9-e11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Webb LJ, Berger LA, Sherlock S. Grey-scale ultrasonography of portal vein. Lancet. 1977;2:675-677. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ghuman SS, Gupta S, Buxi TB, Rawat KS, Yadav A, Mehta N, Sud S. The Abernethy malformation-myriad imaging manifestations of a single entity. Indian J Radiol Imaging. 2016;26:364-372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kumar P, Bhatia M, Garg A, Jain S, Kumar K. Abernethy malformation: A comprehensive review. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2022;28:21-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kim ES, Lee KW, Choe YH. The Characteristics and Outcomes of Abernethy Syndrome in Korean Children: A Single Center Study. Pediatr Gastroenterol Hepatol Nutr. 2019;22:80-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ponziani FR, Faccia M, Zocco MA, Giannelli V, Pellicelli A, Ettorre GM, De Matthaeis N, Pizzolante F, De Gaetano AM, Riccardi L, Pompili M, Rapaccini GL. Congenital extrahepatic portosystemic shunt: description of four cases and review of the literature. J Ultrasound. 2019;22:349-358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Alonso-Gamarra E, Parrón M, Pérez A, Prieto C, Hierro L, López-Santamaría M. Clinical and radiologic manifestations of congenital extrahepatic portosystemic shunts: a comprehensive review. Radiographics. 2011;31:707-722. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Zhou M, Zhang J, Luo L, Wang B, Zheng R, Li L, Jing H, Zhang S. Surgical Ligation for the Treatment of an Unusual Presentation of Type II Abernethy Malformation. Ann Vasc Surg. 2020;65:285.e1-285.e5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Tanaka H, Saijo Y, Tomonari T, Tanaka T, Taniguchi T, Yagi S, Okamoto K, Miyamoto H, Sogabe M, Sato Y, Muguruma N, Tsuneyama K, Sata M, Takayama T. An Adult Case of Congenital Extrahepatic Portosystemic Shunt Successfully Treated with Balloon-occluded Retrograde Transvenous Obliteration. Intern Med. 2021;60:1839-1845. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Wang L, Guo X, Shao X, Xu X, Zheng K, Wang R, Chawla S, Basaranoglu M, Qi X. Association of endoscopic variceal treatment with portal venous system thrombosis in liver cirrhosis: a case-control study. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2022;15:17562848221087536. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |