Published online Feb 26, 2026. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v18.i2.111032

Revised: August 1, 2025

Accepted: December 17, 2025

Published online: February 26, 2026

Processing time: 233 Days and 7.1 Hours

Catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia is a classic example of the successful transfer of genetic cardiology from gene discovery to implementation of precision medicine. This inherited arrhythmia syndrome induces potentially lethal ventricular arrhythmias by catecholaminergic stress in normally structured hearts and is most commonly due to ryanodine receptor 2 (RyR2) mutations in 60%-70% families. Pathophysiology involves gain-of-function mutations forming “leaky” calcium channels with increased sensitivity to catecholaminergic sti

Core Tip: Catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia serves as a paradigm of precision cardiology in which a mechanistic unravelling of the ryanodine receptor 2-mediated calcium ion channel abnormality helps in formulating a genotype-oriented treatment approach. Recent studies regarding the pathopharmacology of store overload-induced calcium ion release, together with mitochondrial interactions, posit the possibility of a more complex pathophysiology than the classic electrical disorders. Recent milestones in the application of the clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats gene editing tool together with artificial intelligence-assisted diagnostic techniques in association with a personalized form of pharmacotherapy have resulted in the successful treatment of 80%-90% of the affected subjects.

- Citation: Sharma V. Ryanodine receptor 2 mutations in catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia: From molecular mechanisms to precision medicine. World J Cardiol 2026; 18(2): 111032

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v18/i2/111032.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v18.i2.111032

Catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (CPVT) is a particularly challenging hereditary cardiac arrhythmia syndrome, distinguished by its paradoxical presentation of potentially fatal ventricular arrhythmias in the absence of structural heart disease[1]. CPVT is a model of the complex interaction between environmental triggers and genetic susceptibility with seemingly normal individuals dying of arrhythmic activity during physical or emotional stress. The cardiac ryanodine receptor 2 (RyR2) gene has been recognized as the major molecular determinant with mutations accounting for almost 60%-70% of CPVT[2]. The mutations go beyond the simple electrical defects to trigger a cascade of cellular dysfunctions with disturbances in calcium homeostasis, mitochondrial dysfunction, and alterations in cellular stress responses[3].

The practice implications are far-reaching: Patients can be asymptomatic on regular assessments but can have sudden cardiac arrest with activities that increase sympathetic drives[4,5]. New developments in the mechanisms of store overload-induced calcium release (SOICR) have transformed CPVT pathophysiological insight, offering new therapeutic targets and accounting for previous enigmatic clinical findings[6,7]. At the same time, new precision medicine strategies, such as base editing technologies and metabolomic profiling, hold the promise to shift patient treatment from empiric therapy to genotype-guided therapy[8,9]. This mini-review synthesized up-to-date in-depth knowledge of RyR2-mediated CPVT pathogenesis, the molecular mechanisms, the new developing diagnostic modalities, and the new promising treatment modalities that can potentially change patient care through precision medicine approaches.

The RyR2 channel is the predominant calcium release channel of the cardiac myocyte sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR). Under physiologic conditions RyR2 channels provide precise calcium homeostasis with very regulated open-close kinetics. CPVT mutations, on the other hand, essentially upset this fine balance through a variety of related mechanisms.

Gain-of-function mechanisms: Most CPVT-associated RyR2 mutations, such as the well-characterized R2474S variant, form “leaky” channels with enhanced calcium sensitivity[10]. The presensitized mutant channels are in an “on-state” and therefore are hyperresponsive to normal stimuli[11]. When activated by β-adrenergic stimulation, activation of the presensitized channels by protein kinase A (PKA) leads to abnormal release of calcium, causing delayed afterdepolarizations and triggered activity, causing ventricular arrhythmias[12].

SOICR: Recent mechanistic studies have confirmed SOICR as an important pathway in CPVT pathophysiology[6,7]. Unlike classical cytosolic calcium-induced calcium release, SOICR is triggered by an overload of SR calcium content. Therefore, it is particularly significant under catecholaminergic stress when SR calcium loading is augmented. CPVT mutations lower the threshold for SOICR activation. Therefore, there is an abnormal condition under which modest increases in SR calcium content will trigger spontaneous calcium release events[13,14].

Luminal calcium sensing dysfunction: The SR luminal calcium-sensing machinery, such as calsequestrin, junctin, and triadin, plays a significant role in CPVT pathogenesis[15]. Mutations of RyR2 can disrupt the interaction between these proteins and the RyR2 channel complex, rendering the channel incapable of sensing luminal calcium levels and terminating calcium release appropriately[16,17]. This dysfunction results in pathological prolonged calcium release events and increased susceptibility to triggered arrhythmias.

Structural consequences: Recent cryoelectron microscopy studies have disclosed that CPVT mutations destabilize the closed conformation of RyR2 channels, lowering the energy barrier for channel opening[18]. This conformational instability is expressed functionally as spontaneous calcium release events, especially under conditions of increased SR calcium load or sympathetic stimulation.

The pathophysiology of CPVT goes beyond the initial dysfunction of calcium channels to involve intricate organellar interactions. SR and mitochondria are closely apposed to each other, and they create microdomains that may allow calcium communication and metabolic coupling.

Calcium-induced calcium release disruption: Mutations in RyR2 interfere with normal mitochondrial-SR calcium cycling and cause mitochondrial overload with calcium, triggering production of reactive oxygen species[19]. This generates a pathological positive feedback mechanism in which reactive oxygen species-induced oxidation of RyR2 channels further enhances their activity, facilitating enhanced calcium leak and arrhythmia susceptibility[20].

Calstabin-2 destabilization: Oxidative stress promotes calstabin-2 dissociation. Calstabin-2 is an important stabilizing protein that otherwise maintains RyR2 channels in a closed conformation[21]. Calstabin-2 dissociation increases channel instability, thus promoting the progressive nature of CPVT pathophysiology. Therapeutic maneuvers promoting calstabin-2 binding have been recently suggested as new treatment strategies[22].

Metabolic reprogramming: Recent metabolomic analyses depict that CPVT cardiomyocytes have changed metabolic profiles, such as impaired fatty acid oxidation and glucose metabolism[23,24]. These metabolic changes could be a cause of cellular energy deficiency that aggravates arrhythmic susceptibility under stress.

The interaction of sympathetic stimulation and CPVT arrhythmogenesis is more complex than mere β-adrenergic receptor activation. Catecholamines initiate a multiplicity of cellular processes that lead to arrhythmic activity.

β-adrenergic signaling cascade: Norepinephrine and epinephrine bind to β1-adrenergic receptors, activate adenylyl cyclase, raising cyclic adenosine monophosphate levels and subsequently activating PKA[25]. PKA phosphorylation of RyR2 at serine 2808 increases channel sensitivity to calcium activation while Ca(2+)/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II phosphorylation at serine 2814 similarly enhances channel activity, both lowering the threshold for calcium-induced calcium release and SOICR[26,27].

α-adrenergic contributions: While β-adrenergic stimulation is the prevailing mechanism, α-adrenergic receptor stimulation is also involved in CPVT pathophysiology through the activation of protein kinase C and interference with calcium handling protein expression[28]. The reason non-selective β-blockers are more effective in general compared with β1-selective agents is this two-receptor action[28,89].

The clinical presentation of CPVT is characterized by extensive heterogeneity as influenced by the behavior of various factors such as mutation-specific effects, genetic modifiers, and environmental determinants[29,30]. The effect of RyR2 mutations on channel function can be classified into several distinct functional classes. Mutations of the central domain are more penetrant and occur earlier, consistent with the important regulatory role of this domain in RyR2 channel function (Table 1). This heterogeneity underscores the application of individualized risk stratification and genotype-dependent therapeutic strategies, most importantly in optimizing β-blocker therapy and exercise recommendations based on genotype-specific characteristics[31].

| Mutation | Domain | Functional effect | Clinical severity1 | Age of onset2 | Penetrance3 | β-blocker response | SOICR threshold4 |

| R2474S | Central | Reduced threshold for Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release | Moderate-severe | Childhood-adolescence | 80%-90% | Variable | Significantly reduced |

| N2386I | Central | Reduced threshold with enhanced sensitivity | Severe | Early childhood | 95% | Poor | Markedly reduced |

| R4497C | Transmembrane | Channel structural instability | Mild-moderate | Adolescence-early adulthood | 60%-70% | Good | Moderately reduced |

| S2246 L | Handle | Increased channel open probability | Moderate | Childhood | 75%-85% | Good | Reduced |

| T2504M | Central | Enhanced SR Ca2+ leak with impaired termination | Severe | Early childhood | 90%-95% | Variable | Severely reduced |

Next-generation sequencing: Large-scale genetic testing has transformed CPVT diagnosis, enabling the identification of known pathogenic mutations and new mutations[32]. Exome and targeted gene panel strategies have revealed new genetic determinants that were previously unrecognized, adding to the complexity of the heterogeneity of the disease. Current clinical gene panels generally encompass RyR2, calcium-sensing machinery, such as calsequestrin, CALM1-3, TRDN, and candidate novel genes[33,34].

Functional validation studies: Discovery of variants of uncertain significance requires functional characterization of pathogenicity[35]. XXX human induced pluripotent stem cell (hiPSC) models are now valuable tools for mutation-specific functional analysis, allowing personalized risk stratification and therapeutic testing[36]. The models permit direct quantification of calcium handling defects and drug response in patient-specific cardiomyocytes.

Copy number variation analysis: Genome analysis in recent years has detected copy number variations and structural variants in CPVT-associated genes that are capable of being implicated in disease pathogenesis[37]. Extensive genomic profiling encompassing these studies can enhance the yield in diagnostic cases with genotype negativity on previous occasions.

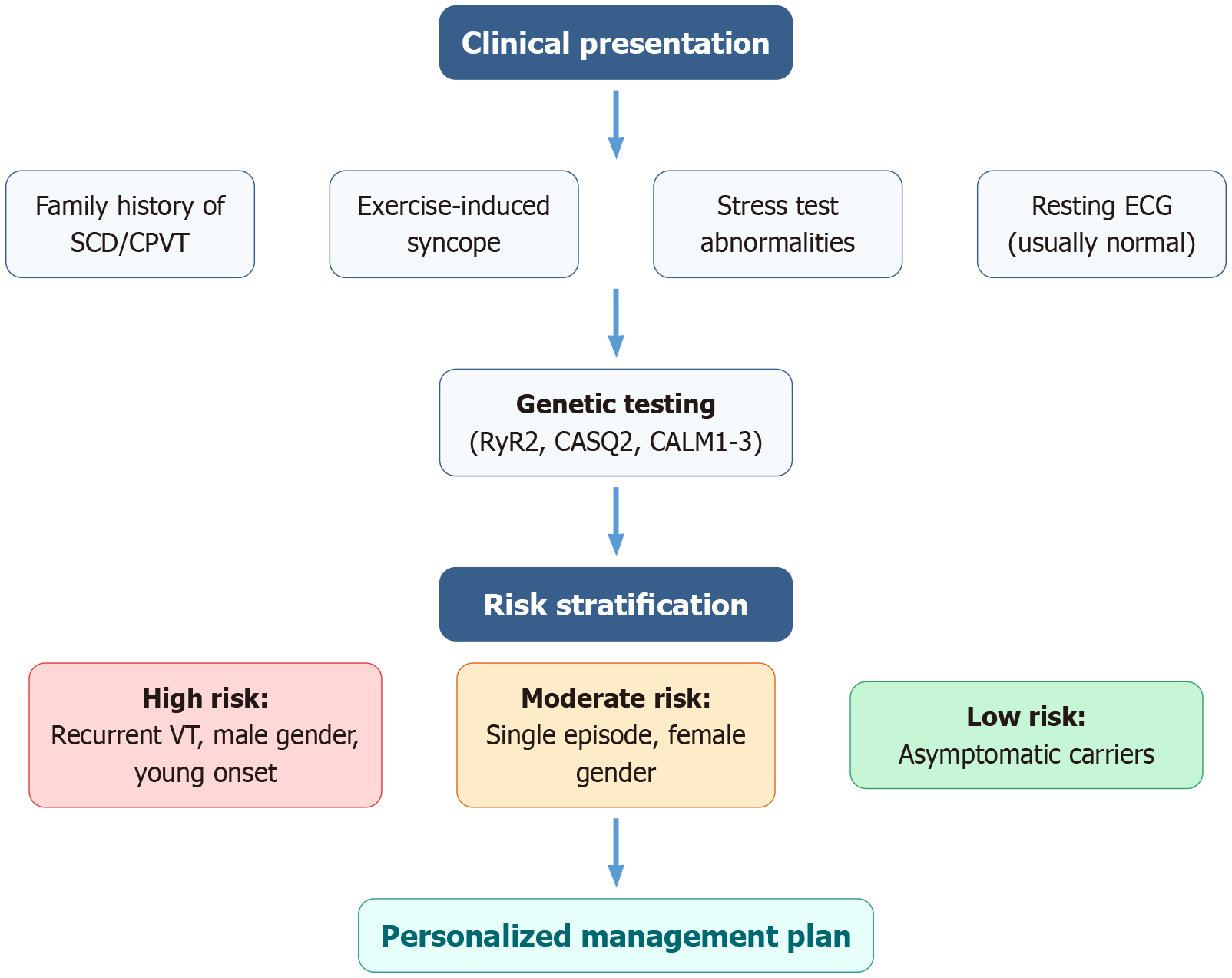

Enhanced risk stratification: Contemporary risk assessment integrates clinical presentation, genetic information, functional investigations, and new biomarkers. Features predictive of high risk include male gender, earlier presentation age, frequent arrhythmic episodes, some high-penetrance mutations (most prominently central domain variants), and proof of enhanced SOICR sensitivity[38,39] (Figure 1). Such a multidimensional assessment facilitates better prognostic prediction and evidence-based therapy decisions.

Exercise testing protocols: Standardized exercise testing continues to be an essential part of CPVT diagnosis and risk stratification. Best practice protocols include graduated exercise testing with ongoing monitoring with the goal of reaching maximum predicted heart rate or symptom onset[40]. Current practices highlight the necessity to monitor the recovery period since arrhythmias can be seen during the catecholamine washout phase[41].

Circulating biomarkers: Emerging research has identified potential biomarkers for CPVT risk prediction, such as circulating microRNAs (specifically microRNA-1 and microRNA-133), calcium-handling protein levels, and oxidative stress markers[42,43]. Not yet clinically confirmed, they could improve diagnostic sensitivity and therapeutic response assessment.

Metabolomic profiling: Recent research has discovered characteristic metabolomic fingerprints in patients with CPVT, such as alterations in amino acid metabolism and lipid levels[23,24]. Fingerprinting can provide complementary diagnostic information and disease progression.

β-adrenergic blockade: β-blockers are the first-line treatment for CPVT, reducing arrhythmic attacks by about 60%-70%[44,45]. Propranolol and nadolol are more effective than the selective β-blockers, possibly because they are non-selective receptor antagonists with longer half-lives. New evidence indicates that carvedilol with added α-blocking and antioxidant actions is superior to conventional β-blockers[46,47].

Flecainide as adjunctive therapy: The sodium channel blocking agent flecainide has also been shown to be an effective second-line therapy, especially in patients who do not respond to β-blockers[48]. Apart from sodium channel blockade, flecainide acts directly on the RyR2 channels by binding to the channel pore and decreasing calcium sensitivity, targeting the pathophysiologic substrate of CPVT[49]. Clinical trials yield striking arrhythmia reduction with the addition of β-blockade to flecainide with response rates of 80%-90%[50,51].

Dantrolene and RyR2 stabilizers: Dantrolene, a direct RyR2 antagonist has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for treating malignant hyperthermia and has been promising for CPVT treatment[52,53]. Through direct binding to RyR2 channels and lowering their sensitivity to calcium activation, dantrolene targets the fundamental mechanism of CPVT. While clinical trials show acute antiarrhythmic efficacy, long-term safety data specific to patients with CPVT remain limited, and potential hepatotoxicity requires careful monitoring, particularly with chronic use[54].

Implantable cardioverter defibrillators: For recurrent life-threatening arrhythmias in the setting of optimal medical therapy, implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) implantation offers definite protection against sudden cardiac death. Inappropriate shocks and device-related complications necessitate optimal programming and careful patient selection[55]. Optimal programming of ICD for patients with CPVT involves some guidelines, such as increased detection rate thresholds and increased detection intervals[56,57].

Left cardiac sympathetic denervation: This procedure interrupts sympathetic innervation to the heart, reducing arrhythmic triggers. Left cardiac sympathetic denervation (LCSD) is especially effective in patients with refractory CPVT, providing a termination of chronic ICD dependency[58]. Recent multicenter series report success rates of 70%-80% in reducing arrhythmic burden with minimal procedural morbidity if done by skilled surgeons[59,60] (Table 2).

| Ref. | Treatment strategy | Arrhythmia reduction | SCD prevention | Side effects | Clinical use | Cost effectiveness |

| Mazzanti et al[44], 2022; Baltogiannis et al[45], 2019; Zhou et al[46], 2011 | β-blockers alone | 60%-70% | Moderate | Fatigue, bradycardia | First-line | High |

| Watanabe et al[48], 2011 | β-blockers + Flecainide | 80%-90% | High | Proarrhythmia risk | Refractory cases | Moderate |

| Kannankeril et al[50], 2017 | Carvedilol | 70%-80% | Moderate-high | Hypotension, fatigue | Alternative first line | High |

| Penttinen et al[52], 2015; Kobayashi et al[53], 2009 | Dantrolene + β-blockers | 75%-85% | High | Hepatotoxicity, weakness | Experimental | Unknown |

| van der Werf et al[55], 2011 | ICD | > 95% | Very high | Device complications | High-risk patients | Low-moderate |

| De Ferrari et al[59], 2015; Hofferberth et al[60], 2014 | LCSD | 70%-80% | High | Surgical risks | β-blocker failure | Moderate |

Gene editing technologies: Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat-associated protein Cas9 gene correction is the holy grail of precision therapy. Its promise is to provide a definitive cure by targeted repair of mutations[61,62]. Preclinical use in patient-specific hiPSC models demonstrates proof-of-concept for mutation-specific gene editing although clinical translation remains years away due to delivery challenges and safety considerations.

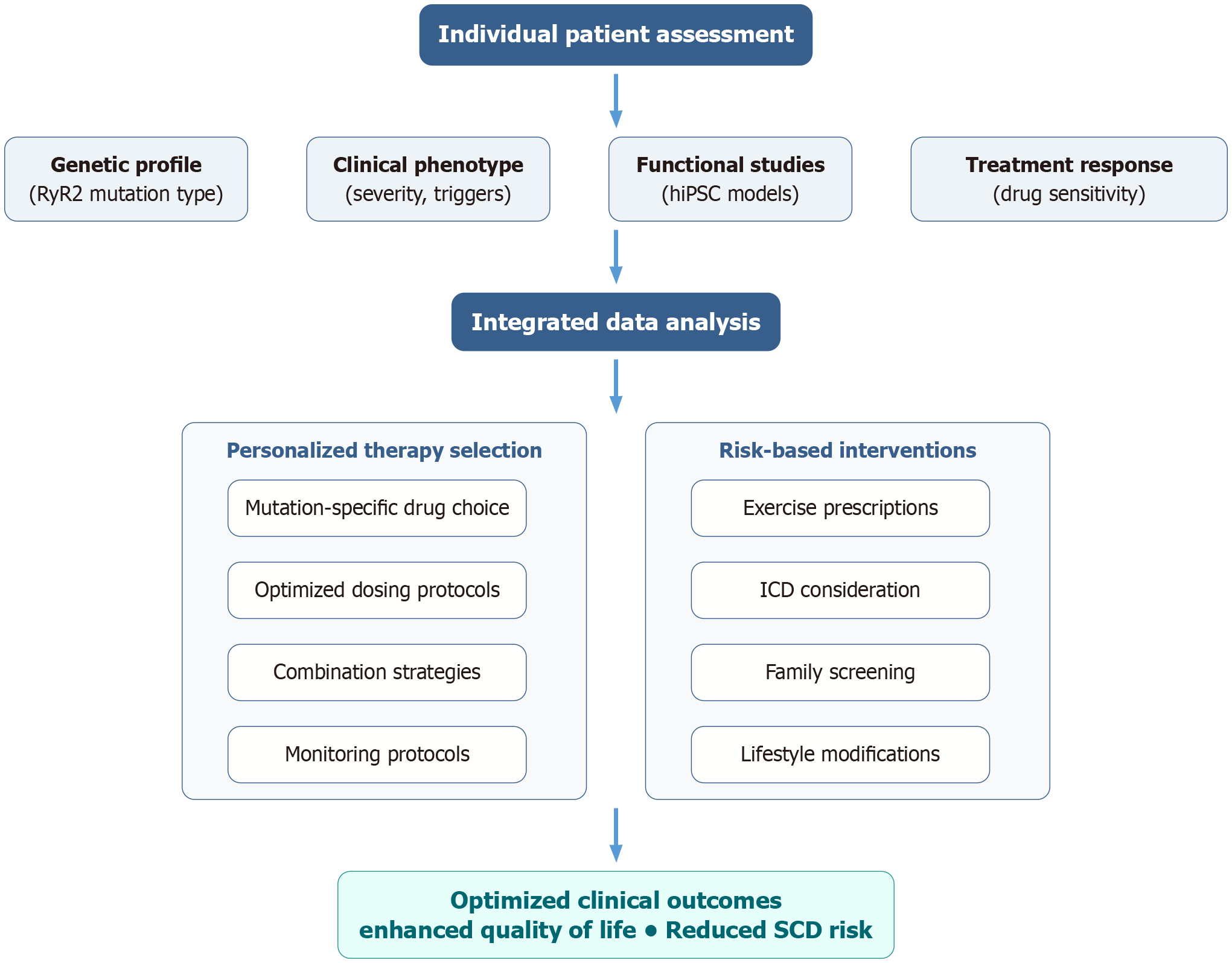

Targeted molecular interventions: Targeted molecular therapies represent new therapeutic strategies that target specific pathophysiological mechanisms[63-65] (Figure 2): (1) RyR2 channel stabilizers: Small molecules specially designed to restore normal channel kinetics and reduce calcium leakage[66]; (2) Calmodulin modulators: Drugs that augment regulation of calcium sensitivity and enhance excitation-contraction coupling[67,68]; (3) Mitochondrial protective therapies: Therapies aimed at oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction[19]; and (4) Calcium handling protein optimization: Gene therapy strategies to correct normal SR calcium cycling[69].

Successful management of CPVT requires a multidisciplinary team of geneticists, cardiologists, electrophysiologists, genetic counselors, and mental health providers. Multidisciplinary CPVT clinics allow for full care and provide specialized expertise in the management of this complicated disorder[70].

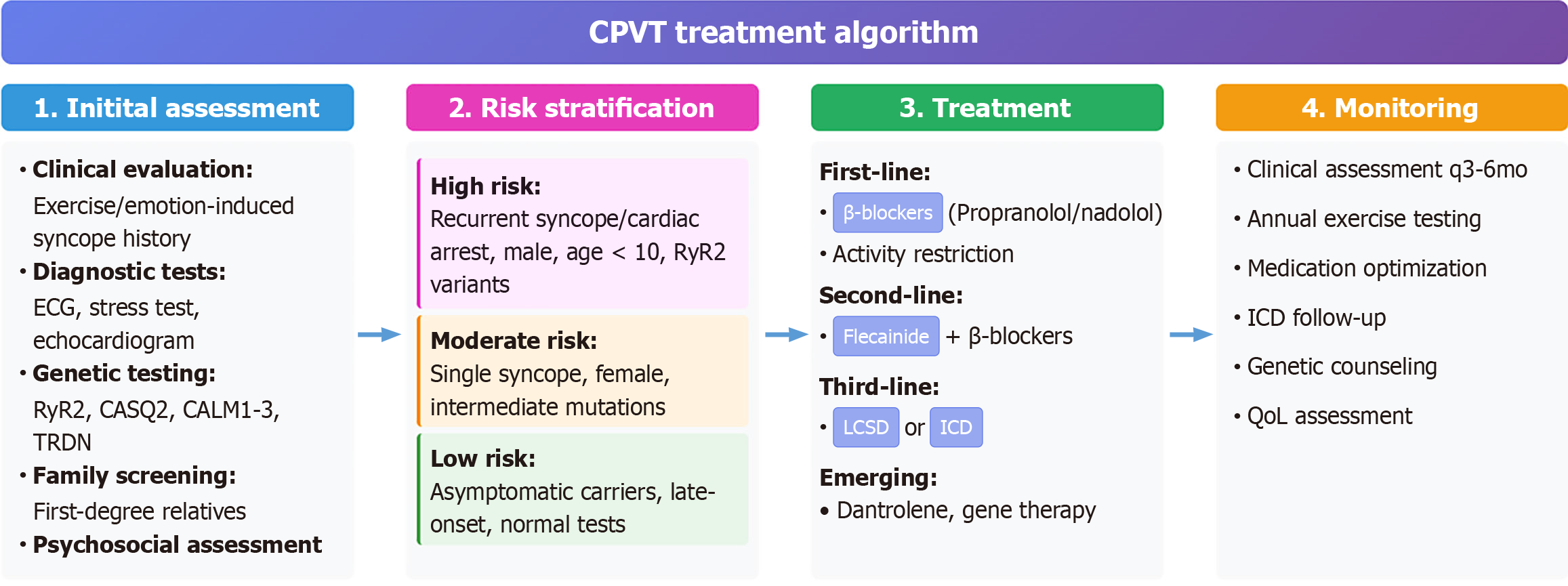

According to present proof and the agreement of specialists, the following treatment algorithm is recommended.

Initial assessment: (1) A thorough clinical history and physical examination; (2) 12-lead electrocardiogram and exercise stress test; (3) Genetic testing for CPVT-causing genes; (4) Cascade screening and family history assessment; and (5) Psychological evaluation and counseling.

Risk stratification: (1) High risk: Repeat syncope/cardiac arrest, male gender, early age at onset, high-penetrance mutations; (2) Moderate risk: One syncopal episode, female sex, moderate-penetrance mutations; and (3) Low risk: Asymptomatic carriers, late onset, low-penetrance mutations.

Treatment selection: (1) First-line: Β-blocker therapy (propranolol, nadolol, or carvedilol); (2) Second-line: Add flecainide for inadequate β-blocker response; (3) Third-line: Consider LCSD for medication-refractory cases; (4) ICD implantation for recurrent life-threatening arrhythmias; and (5) Emerging therapies: Gene editing, targeted molecular interventions (investigational) (Figure 3).

Combining multi-omic data (genomics, proteomics, metabolomics) with machine learning has the potential to provide more refined risk stratification and therapeutic monitoring[71]. Artificial intelligence-based strategies have the potential to detect new biomarkers, predict outcomes of treatment with unparalleled sensitivity, and tailor personalized management regimens.

Organoid and tissue engineering models: Patient-derived hiPSC three-dimensional cardiac organoids offer more physiologically accurate disease models to describe mechanisms and for drug discovery[36]. These systems allow for high-throughput screening of therapeutic compounds, personalized drug testing, and exploration of cell-cell interactions in CPVT pathophysiology.

Population screening: Population-based genetic screening for CPVT represents an emerging strategy for early identification of at-risk individuals before symptom onset. Current research focuses on developing cost-effective screening algorithms that balance detection sensitivity with healthcare resource utilization. Implementation considerations include establishing appropriate screening age thresholds, defining high-risk populations for targeted screening, and developing robust genetic counseling infrastructure to support population-level programs[72,73].

Preventive gene therapy: Prophylactic gene correction or supplementation therapy in high-risk asymptomatic carriers represents the ultimate precision medicine approach, potentially preventing disease manifestation prior to clinical presentation. Current research focuses on developing safe and effective delivery systems, optimizing therapeutic gene constructs, and establishing appropriate timing for intervention. Long-term safety studies and ethical considerations regarding intervention in asymptomatic individuals remain critical challenges that must be addressed before clinical implementation[62].

Early intervention strategies: Development of biomarker-guided early intervention protocols may enable treatment initiation before arrhythmic events occur. This includes establishing validated biomarker panels for disease progression monitoring, developing exercise prescription guidelines for asymptomatic carriers, and creating family-centered prevention programs that address both genetic and lifestyle factors contributing to arrhythmic risk.

Asymptomatic carrier management: The optimal approach for asymptomatic genetic carriers remains controversial. Some advocate prophylactic β-blocker treatment, whereas others suggest watchful waiting with activity modification[74,75].

Exercise recommendations: The level of activity restriction required in patients with CPVT is controversial. Individualized exercise prescriptions according to stress testing and genetic risk stratification are a new strategy[76,77].

Long-term outcomes: Comprehensive long-term follow-up data remain scarce for most CPVT treatments, particularly newer pharmacological agents and interventional strategies. The lack of randomized controlled trials in this rare disease population presents significant challenges for evidence-based treatment recommendations. Large-scale patient registries and collaborative research networks are essential to generate robust outcome data and establish optimal treatment algorithms. Current limitations include insufficient follow-up duration, heterogeneous treatment protocols across centers, and limited standardization of outcome measures[78].

Biomarker validation: Although several potential biomarkers have been identified, none have undergone rigorous validation for clinical implementation. Comprehensive validation studies examining sensitivity, specificity, and clinical utility across diverse patient populations are necessary before biomarkers can be integrated into routine clinical practice. Current research priorities include establishing standardized measurement protocols, defining appropriate reference ranges, and determining optimal timing for biomarker assessment in relation to clinical events[79].

CPVT mutational patterns exhibit geographic and ethnic diversity with some founder mutations being common in some populations[80,81]. These variations have important implications for diagnostic testing strategies and treatment approaches. Major global disparities exist in access to genetic testing, specialized cardiac care, and novel therapies for CPVT, creating significant healthcare inequities that must be addressed through international collaborative efforts and resource allocation strategies[82].

Resource limitations: Implementation of precision medicine approaches faces significant challenges, including limited access to genetic testing in developing countries, a shortage of specialized electrophysiology centers, and high costs of advanced therapies. Healthcare systems must develop sustainable funding models and training programs to ensure equitable access to CPVT care globally.

Insurance coverage: Variability in insurance coverage for genetic testing, specialized medications like flecainide, and advanced interventions such as LCSD creates barriers to optimal care. Advocacy efforts and health economics research are needed to demonstrate the cost-effectiveness of comprehensive CPVT management programs.

The quality-of-life effect of CPVT goes beyond mere arrhythmic events, adding psychological distress, restriction of activities, and social function[83,84]. The genetic nature of CPVT creates complex family dynamics requiring comprehensive genetic counseling addressing medical, psychological, and social implications[85,86]. Mental health support, patient education programs, and family-centered care approaches are essential components of comprehensive CPVT management.

CPVT represents a paradigm of successful translation from molecular cardiology research to clinical implementation, demonstrating the potential of mechanistic understanding to drive therapeutic innovation. The evolution from gene discovery to precision medicine highlights several key principles: (1) Integration of basic and clinical science: The greatest progress in CPVT treatment has resulted from intimate collaboration between basic scientists and clinicians with a focus on the need for translational research approaches[87-89]. The discovery of SOICR mechanisms and their therapeutic relevance is a classic example of effective integration; (2) Personalized medicine implementation: Current data validate mutation-specific risk stratification and individually targeted therapeutic interventions[29]. As genotype-phenotype correlations become better defined, increasingly precise personalized medicine approaches will become standard practice; (3) Multidisciplinary care models: Effective CPVT management requires coordinated care among geneticists, cardio

The evolution of CPVT from empiric to precision medicine demonstrates the transformative power of genetic cardiology in improving patient outcomes. As we advance toward more sophisticated therapeutic interventions, the ultimate goal remains clear: Prevention of sudden cardiac death while maintaining quality of life in this high-risk population. Understanding of RyR2-mediated CPVT provides a template for managing other inherited arrhythmia syndromes, illustrating the central role of molecular mechanisms in guiding clinical practice. The future integration of advanced science with compassionate patient care will undoubtedly yield further advances in this challenging yet rewarding field.

| 1. | Henriquez E, Hernandez EA, Mundla SR, Wankhade DH, Saad M, Ketha SS, Penke Y, Martinez GC, Ahmed FS, Hussain MS. Catecholaminergic Polymorphic Ventricular Tachycardia and Gene Therapy: A Comprehensive Review of the Literature. Cureus. 2023;15:e47974. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Roston TM, Yuchi Z, Kannankeril PJ, Hathaway J, Vinocur JM, Etheridge SP, Potts JE, Maginot KR, Salerno JC, Cohen MI, Hamilton RM, Pflaumer A, Mohammed S, Kimlicka L, Kanter RJ, LaPage MJ, Collins KK, Gebauer RA, Temple JD, Batra AS, Erickson C, Miszczak-Knecht M, Kubuš P, Bar-Cohen Y, Kantoch M, Thomas VC, Hessling G, Anderson C, Young ML, Choi SHJ, Cabrera Ortega M, Lau YR, Johnsrude CL, Fournier A, Van Petegem F, Sanatani S. The clinical and genetic spectrum of catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia: findings from an international multicentre registry. Europace. 2018;20:541-547. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | George CH, Higgs GV, Lai FA. Ryanodine receptor mutations associated with stress-induced ventricular tachycardia mediate increased calcium release in stimulated cardiomyocytes. Circ Res. 2003;93:531-540. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 191] [Cited by in RCA: 190] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Tester DJ, Ackerman MJ. Genetic testing for potentially lethal, highly treatable inherited cardiomyopathies/channelopathies in clinical practice. Circulation. 2011;123:1021-1037. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 158] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Aggarwal A, Stolear A, Alam MM, Vardhan S, Dulgher M, Jang SJ, Zarich SW. Catecholaminergic Polymorphic Ventricular Tachycardia: Clinical Characteristics, Diagnostic Evaluation and Therapeutic Strategies. J Clin Med. 2024;13:1781. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Chen W, Wang R, Chen B, Zhong X, Kong H, Bai Y, Zhou Q, Xie C, Zhang J, Guo A, Tian X, Jones PP, O'Mara ML, Liu Y, Mi T, Zhang L, Bolstad J, Semeniuk L, Cheng H, Zhang J, Chen J, Tieleman DP, Gillis AM, Duff HJ, Fill M, Song LS, Chen SR. The ryanodine receptor store-sensing gate controls Ca2+ waves and Ca2+-triggered arrhythmias. Nat Med. 2014;20:184-192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 145] [Cited by in RCA: 163] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Jiang D, Wang R, Xiao B, Kong H, Hunt DJ, Choi P, Zhang L, Chen SR. Enhanced store overload-induced Ca2+ release and channel sensitivity to luminal Ca2+ activation are common defects of RyR2 mutations linked to ventricular tachycardia and sudden death. Circ Res. 2005;97:1173-1181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 278] [Cited by in RCA: 288] [Article Influence: 13.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Wleklinski MJ, Kannankeril PJ, Knollmann BC. Molecular and tissue mechanisms of catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. J Physiol. 2020;598:2817-2834. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 15.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Siu A, Tandanu E, Ma B, Osas EE, Liu H, Liu T, Chou OHI, Huang H, Tse G. Precision medicine in catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia: Recent advances toward personalized care. Ann Pediatr Cardiol. 2023;16:431-446. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Wehrens XH, Lehnart SE, Reiken S, Vest JA, Wronska A, Marks AR. Ryanodine receptor/calcium release channel PKA phosphorylation: a critical mediator of heart failure progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:511-518. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 285] [Cited by in RCA: 279] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Priori SG, Chen SR. Inherited dysfunction of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ handling and arrhythmogenesis. Circ Res. 2011;108:871-883. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 376] [Cited by in RCA: 349] [Article Influence: 23.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Shan J, Betzenhauser MJ, Kushnir A, Reiken S, Meli AC, Wronska A, Dura M, Chen BX, Marks AR. Role of chronic ryanodine receptor phosphorylation in heart failure and β-adrenergic receptor blockade in mice. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:4375-4387. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 176] [Cited by in RCA: 194] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Gonano LA, Vila Petroff M. Direct Modulation of RyR2 Leading to a TRICky Ca(2+) Balance: The Effects of TRIC-A on Cardiac Muscle. Circ Res. 2020;126:436-438. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Zhao YT, Valdivia CR, Gurrola GB, Powers PP, Willis BC, Moss RL, Jalife J, Valdivia HH. Arrhythmogenesis in a catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia mutation that depresses ryanodine receptor function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:E1669-E1677. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Knollmann BC, Chopra N, Hlaing T, Akin B, Yang T, Ettensohn K, Knollmann BE, Horton KD, Weissman NJ, Holinstat I, Zhang W, Roden DM, Jones LR, Franzini-Armstrong C, Pfeifer K. Casq2 deletion causes sarcoplasmic reticulum volume increase, premature Ca2+ release, and catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:2510-2520. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 262] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Song L, Alcalai R, Arad M, Wolf CM, Toka O, Conner DA, Berul CI, Eldar M, Seidman CE, Seidman JG. Calsequestrin 2 (CASQ2) mutations increase expression of calreticulin and ryanodine receptors, causing catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1814-1823. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Postma AV, Denjoy I, Hoorntje TM, Lupoglazoff JM, Da Costa A, Sebillon P, Mannens MM, Wilde AA, Guicheney P. Absence of calsequestrin 2 causes severe forms of catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Circ Res. 2002;91:e21-e26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 302] [Cited by in RCA: 289] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Miotto MC, Weninger G, Dridi H, Yuan Q, Liu Y, Wronska A, Melville Z, Sittenfeld L, Reiken S, Marks AR. Structural analyses of human ryanodine receptor type 2 channels reveal the mechanisms for sudden cardiac death and treatment. Sci Adv. 2022;8:eabo1272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Hamilton S, Terentyeva R, Martin B, Perger F, Li J, Stepanov A, Bonilla IM, Knollmann BC, Radwański PB, Györke S, Belevych AE, Terentyev D. Increased RyR2 activity is exacerbated by calcium leak-induced mitochondrial ROS. Basic Res Cardiol. 2020;115:38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 16.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Belevych AE, Terentyev D, Terentyeva R, Ho HT, Gyorke I, Bonilla IM, Carnes CA, Billman GE, Györke S. Shortened Ca2+ signaling refractoriness underlies cellular arrhythmogenesis in a postinfarction model of sudden cardiac death. Circ Res. 2012;110:569-577. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Wehrens XH, Lehnart SE, Huang F, Vest JA, Reiken SR, Mohler PJ, Sun J, Guatimosim S, Song LS, Rosemblit N, D'Armiento JM, Napolitano C, Memmi M, Priori SG, Lederer WJ, Marks AR. FKBP12.6 deficiency and defective calcium release channel (ryanodine receptor) function linked to exercise-induced sudden cardiac death. Cell. 2003;113:829-840. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 554] [Cited by in RCA: 573] [Article Influence: 24.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Lehnart SE, Mongillo M, Bellinger A, Lindegger N, Chen BX, Hsueh W, Reiken S, Wronska A, Drew LJ, Ward CW, Lederer WJ, Kass RS, Morley G, Marks AR. Leaky Ca2+ release channel/ryanodine receptor 2 causes seizures and sudden cardiac death in mice. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:2230-2245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 206] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Park SJ, Zhang D, Qi Y, Li Y, Lee KY, Bezzerides VJ, Yang P, Xia S, Kim SL, Liu X, Lu F, Pasqualini FS, Campbell PH, Geva J, Roberts AE, Kleber AG, Abrams DJ, Pu WT, Parker KK. Insights Into the Pathogenesis of Catecholaminergic Polymorphic Ventricular Tachycardia From Engineered Human Heart Tissue. Circulation. 2019;140:390-404. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 14.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Bezzerides VJ, Caballero A, Wang S, Ai Y, Hylind RJ, Lu F, Heims-Waldron DA, Chambers KD, Zhang D, Abrams DJ, Pu WT. Gene Therapy for Catecholaminergic Polymorphic Ventricular Tachycardia by Inhibition of Ca(2+)/Calmodulin-Dependent Kinase II. Circulation. 2019;140:405-419. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Dobrev D, Wehrens XH. Role of RyR2 phosphorylation in heart failure and arrhythmias: Controversies around ryanodine receptor phosphorylation in cardiac disease. Circ Res. 2014;114:1311-9; discussion 1319. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 155] [Article Influence: 12.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Venetucci LA, Trafford AW, O'Neill SC, Eisner DA. The sarcoplasmic reticulum and arrhythmogenic calcium release. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;77:285-292. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 169] [Cited by in RCA: 170] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Houser SR. Role of RyR2 phosphorylation in heart failure and arrhythmias: protein kinase A-mediated hyperphosphorylation of the ryanodine receptor at serine 2808 does not alter cardiac contractility or cause heart failure and arrhythmias. Circ Res. 2014;114:1320-7; discussion 1327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Niggli E, Ullrich ND, Gutierrez D, Kyrychenko S, Poláková E, Shirokova N. Posttranslational modifications of cardiac ryanodine receptors: Ca(2+) signaling and EC-coupling. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1833:866-875. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Zaffran S, Kraoua L, Jaouadi H. Calcium Handling in Inherited Cardiac Diseases: A Focus on Catecholaminergic Polymorphic Ventricular Tachycardia and Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:3365. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Kurtzwald-Josefson E, Hochhauser E, Katz G, Porat E, Seidman JG, Seidman CE, Chepurko Y, Shainberg A, Eldar M, Arad M. Exercise training improves cardiac function and attenuates arrhythmia in CPVT mice. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2012;113:1677-1683. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Kallas D, Lamba A, Roston TM, Arslanova A, Franciosi S, Tibbits GF, Sanatani S. Pediatric Catecholaminergic Polymorphic Ventricular Tachycardia: A Translational Perspective for the Clinician-Scientist. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:9293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Kapplinger JD, Pundi KN, Larson NB, Callis TE, Tester DJ, Bikker H, Wilde AAM, Ackerman MJ. Yield of the RYR2 Genetic Test in Suspected Catecholaminergic Polymorphic Ventricular Tachycardia and Implications for Test Interpretation. Circ Genom Precis Med. 2018;11:e001424. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Altmann HM, Tester DJ, Will ML, Middha S, Evans JM, Eckloff BW, Ackerman MJ. Homozygous/Compound Heterozygous Triadin Mutations Associated With Autosomal-Recessive Long-QT Syndrome and Pediatric Sudden Cardiac Arrest: Elucidation of the Triadin Knockout Syndrome. Circulation. 2015;131:2051-2060. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Crotti L, Johnson CN, Graf E, De Ferrari GM, Cuneo BF, Ovadia M, Papagiannis J, Feldkamp MD, Rathi SG, Kunic JD, Pedrazzini M, Wieland T, Lichtner P, Beckmann BM, Clark T, Shaffer C, Benson DW, Kääb S, Meitinger T, Strom TM, Chazin WJ, Schwartz PJ, George AL Jr. Calmodulin mutations associated with recurrent cardiac arrest in infants. Circulation. 2013;127:1009-1017. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 277] [Cited by in RCA: 309] [Article Influence: 23.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Burke W, Parens E, Chung WK, Berger SM, Appelbaum PS. The Challenge of Genetic Variants of Uncertain Clinical Significance : A Narrative Review. Ann Intern Med. 2022;175:994-1000. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 22.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Bezzerides VJ, Zhang D, Pu WT. Modeling Inherited Arrhythmia Disorders Using Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Cardiomyocytes. Circ J. 2016;81:12-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Marsman RF, Barc J, Beekman L, Alders M, Dooijes D, van den Wijngaard A, Ratbi I, Sefiani A, Bhuiyan ZA, Wilde AA, Bezzina CR. A mutation in CALM1 encoding calmodulin in familial idiopathic ventricular fibrillation in childhood and adolescence. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:259-266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Roston TM, Guo W, Krahn AD, Wang R, Van Petegem F, Sanatani S, Chen SR, Lehman A. A novel RYR2 loss-of-function mutation (I4855M) is associated with left ventricular non-compaction and atypical catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. J Electrocardiol. 2017;50:227-233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Lieve KVV, Verhagen JMA, Wei J, Bos JM, van der Werf C, Rosés I Noguer F, Mancini GMS, Guo W, Wang R, van den Heuvel F, Frohn-Mulder IME, Shimizu W, Nogami A, Horigome H, Roberts JD, Leenhardt A, Crijns HJG, Blank AC, Aiba T, Wiesfeld ACP, Blom NA, Sumitomo N, Till J, Ackerman MJ, Chen SRW, van de Laar IMBH, Wilde AAM. Linking the heart and the brain: Neurodevelopmental disorders in patients with catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Heart Rhythm. 2019;16:220-228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Haugaa KH, Leren IS, Berge KE, Bathen J, Loennechen JP, Anfinsen OG, Früh A, Edvardsen T, Kongsgård E, Leren TP, Amlie JP. High prevalence of exercise-induced arrhythmias in catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia mutation-positive family members diagnosed by cascade genetic screening. Europace. 2010;12:417-423. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Bhuiyan ZA, Hamdan MA, Shamsi ET, Postma AV, Mannens MM, Wilde AA, Al-Gazali L. A novel early onset lethal form of catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia maps to chromosome 7p14-p22. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2007;18:1060-1066. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (8)] |

| 42. | Devalla HD, Gélinas R, Aburawi EH, Beqqali A, Goyette P, Freund C, Chaix MA, Tadros R, Jiang H, Le Béchec A, Monshouwer-Kloots JJ, Zwetsloot T, Kosmidis G, Latour F, Alikashani A, Hoekstra M, Schlaepfer J, Mummery CL, Stevenson B, Kutalik Z, de Vries AA, Rivard L, Wilde AA, Talajic M, Verkerk AO, Al-Gazali L, Rioux JD, Bhuiyan ZA, Passier R. TECRL, a new life-threatening inherited arrhythmia gene associated with overlapping clinical features of both LQTS and CPVT. EMBO Mol Med. 2016;8:1390-1408. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Gray B, Behr ER. New Insights Into the Genetic Basis of Inherited Arrhythmia Syndromes. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2016;9:569-577. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Mazzanti A, Kukavica D, Trancuccio A, Memmi M, Bloise R, Gambelli P, Marino M, Ortíz-Genga M, Morini M, Monteforte N, Giordano U, Keegan R, Tomasi L, Anastasakis A, Davis AM, Shimizu W, Blom NA, Santiago DJ, Napolitano C, Monserrat L, Priori SG. Outcomes of Patients With Catecholaminergic Polymorphic Ventricular Tachycardia Treated With β-Blockers. JAMA Cardiol. 2022;7:504-512. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Baltogiannis GG, Lysitsas DN, di Giovanni G, Ciconte G, Sieira J, Conte G, Kolettis TM, Chierchia GB, de Asmundis C, Brugada P. CPVT: Arrhythmogenesis, Therapeutic Management, and Future Perspectives. A Brief Review of the Literature. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2019;6:92. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Zhou Q, Xiao J, Jiang D, Wang R, Vembaiyan K, Wang A, Smith CD, Xie C, Chen W, Zhang J, Tian X, Jones PP, Zhong X, Guo A, Chen H, Zhang L, Zhu W, Yang D, Li X, Chen J, Gillis AM, Duff HJ, Cheng H, Feldman AM, Song LS, Fill M, Back TG, Chen SR. Carvedilol and its new analogs suppress arrhythmogenic store overload-induced Ca2+ release. Nat Med. 2011;17:1003-1009. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 217] [Cited by in RCA: 207] [Article Influence: 13.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Bos JM, Bos KM, Johnson JN, Moir C, Ackerman MJ. Left cardiac sympathetic denervation in long QT syndrome: analysis of therapeutic nonresponders. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2013;6:705-711. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Watanabe H, Steele DS, Knollmann BC. Mechanism of antiarrhythmic effects of flecainide in catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Circ Res. 2011;109:712-713. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Hilliard FA, Steele DS, Laver D, Yang Z, Le Marchand SJ, Chopra N, Piston DW, Huke S, Knollmann BC. Flecainide inhibits arrhythmogenic Ca2+ waves by open state block of ryanodine receptor Ca2+ release channels and reduction of Ca2+ spark mass. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2010;48:293-301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 182] [Cited by in RCA: 200] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Kannankeril PJ, Moore JP, Cerrone M, Priori SG, Kertesz NJ, Ro PS, Batra AS, Kaufman ES, Fairbrother DL, Saarel EV, Etheridge SP, Kanter RJ, Carboni MP, Dzurik MV, Fountain D, Chen H, Ely EW, Roden DM, Knollmann BC. Efficacy of Flecainide in the Treatment of Catecholaminergic Polymorphic Ventricular Tachycardia: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2017;2:759-766. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 19.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Wang G, Zhao N, Zhong S, Wang Y, Li J. Safety and efficacy of flecainide for patients with catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98:e16961. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Penttinen K, Swan H, Vanninen S, Paavola J, Lahtinen AM, Kontula K, Aalto-Setälä K. Antiarrhythmic Effects of Dantrolene in Patients with Catecholaminergic Polymorphic Ventricular Tachycardia and Replication of the Responses Using iPSC Models. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0125366. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Kobayashi S, Yano M, Suetomi T, Ono M, Tateishi H, Mochizuki M, Xu X, Uchinoumi H, Okuda S, Yamamoto T, Koseki N, Kyushiki H, Ikemoto N, Matsuzaki M. Dantrolene, a therapeutic agent for malignant hyperthermia, markedly improves the function of failing cardiomyocytes by stabilizing interdomain interactions within the ryanodine receptor. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:1993-2005. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 163] [Cited by in RCA: 155] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Jung CB, Moretti A, Mederos y Schnitzler M, Iop L, Storch U, Bellin M, Dorn T, Ruppenthal S, Pfeiffer S, Goedel A, Dirschinger RJ, Seyfarth M, Lam JT, Sinnecker D, Gudermann T, Lipp P, Laugwitz KL. Dantrolene rescues arrhythmogenic RYR2 defect in a patient-specific stem cell model of catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. EMBO Mol Med. 2012;4:180-191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 246] [Cited by in RCA: 254] [Article Influence: 18.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | van der Werf C, Kannankeril PJ, Sacher F, Krahn AD, Viskin S, Leenhardt A, Shimizu W, Sumitomo N, Fish FA, Bhuiyan ZA, Willems AR, van der Veen MJ, Watanabe H, Laborderie J, Haïssaguerre M, Knollmann BC, Wilde AA. Flecainide therapy reduces exercise-induced ventricular arrhythmias in patients with catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:2244-2254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 345] [Cited by in RCA: 304] [Article Influence: 20.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Roses-Noguer F, Jarman JW, Clague JR, Till J. Outcomes of defibrillator therapy in catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Heart Rhythm. 2014;11:58-66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Sumitomo N, Harada K, Nagashima M, Yasuda T, Nakamura Y, Aragaki Y, Saito A, Kurosaki K, Jouo K, Koujiro M, Konishi S, Matsuoka S, Oono T, Hayakawa S, Miura M, Ushinohama H, Shibata T, Niimura I. Catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia: electrocardiographic characteristics and optimal therapeutic strategies to prevent sudden death. Heart. 2003;89:66-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 275] [Cited by in RCA: 252] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (12)] |

| 58. | Collura CA, Johnson JN, Moir C, Ackerman MJ. Left cardiac sympathetic denervation for the treatment of long QT syndrome and catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia using video-assisted thoracic surgery. Heart Rhythm. 2009;6:752-759. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 253] [Cited by in RCA: 247] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | De Ferrari GM, Dusi V, Spazzolini C, Bos JM, Abrams DJ, Berul CI, Crotti L, Davis AM, Eldar M, Kharlap M, Khoury A, Krahn AD, Leenhardt A, Moir CR, Odero A, Olde Nordkamp L, Paul T, Rosés I Noguer F, Shkolnikova M, Till J, Wilde AA, Ackerman MJ, Schwartz PJ. Clinical Management of Catecholaminergic Polymorphic Ventricular Tachycardia: The Role of Left Cardiac Sympathetic Denervation. Circulation. 2015;131:2185-2193. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 193] [Cited by in RCA: 226] [Article Influence: 20.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Hofferberth SC, Cecchin F, Loberman D, Fynn-Thompson F. Left thoracoscopic sympathectomy for cardiac denervation in patients with life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;147:404-409. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Yamaguchi N, Zhang XH, Morad M. CRISPR/Cas9 Gene Editing of RYR2 in Human iPSC-Derived Cardiomyocytes to Probe Ca(2+) Signaling Aberrancies of CPVT Arrhythmogenesis. Methods Mol Biol. 2022;2573:41-52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Moore OM, Aguilar-Sanchez Y, Lahiri SK, Hulsurkar MM, Alberto Navarro-Garcia J, Word TA, Keefe JA, Barazi D, Munivez EM, Moore CT, Parthasarathy V, Davidson J, Lagor WR, Park SH, Bao G, Miyake CY, Wehrens XHT. Long-term efficacy and safety of cardiac genome editing for catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. J Cardiovasc Aging. 2024;4:8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Word TA, Quick AP, Miyake CY, Shak MK, Pan X, Kim JJ, Allen HD, Sibrian-Vazquez M, Strongin RM, Landstrom AP, Wehrens XHT. Efficacy of RyR2 inhibitor EL20 in induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes from a patient with catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. J Cell Mol Med. 2021;25:6115-6124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Engel MA, Wörmann YR, Kaestner H, Schüler C. An Optogenetic Arrhythmia Model-Insertion of Several Catecholaminergic Polymorphic Ventricular Tachycardia Mutations Into Caenorhabditis elegans UNC-68 Disturbs Calstabin-Mediated Stabilization of the Ryanodine Receptor Homolog. Front Physiol. 2022;13:691829. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Wangüemert F, Bosch Calero C, Pérez C, Campuzano O, Beltran-Alvarez P, Scornik FS, Iglesias A, Berne P, Allegue C, Ruiz Hernandez PM, Brugada J, Pérez GJ, Brugada R. Clinical and molecular characterization of a cardiac ryanodine receptor founder mutation causing catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Heart Rhythm. 2015;12:1636-1643. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Hartmann N, Pabel S, Herting J, Schatter F, Renner A, Gummert J, Schotola H, Danner BC, Maier LS, Frey N, Hasenfuss G, Fischer TH, Sossalla S. Antiarrhythmic effects of dantrolene in human diseased cardiomyocytes. Heart Rhythm. 2017;14:412-419. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Nakamura Y, Yamamoto T, Kobayashi S, Tamitani M, Hamada Y, Fukui G, Xu X, Nishimura S, Kato T, Uchinoumi H, Oda T, Okuda S, Yano M. Ryanodine receptor-bound calmodulin is essential to protect against catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. JCI Insight. 2019;4:e126112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Makita N, Yagihara N, Crotti L, Johnson CN, Beckmann BM, Roh MS, Shigemizu D, Lichtner P, Ishikawa T, Aiba T, Homfray T, Behr ER, Klug D, Denjoy I, Mastantuono E, Theisen D, Tsunoda T, Satake W, Toda T, Nakagawa H, Tsuji Y, Tsuchiya T, Yamamoto H, Miyamoto Y, Endo N, Kimura A, Ozaki K, Motomura H, Suda K, Tanaka T, Schwartz PJ, Meitinger T, Kääb S, Guicheney P, Shimizu W, Bhuiyan ZA, Watanabe H, Chazin WJ, George AL Jr. Novel calmodulin mutations associated with congenital arrhythmia susceptibility. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2014;7:466-474. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 146] [Article Influence: 12.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Kurtzwald-Josefson E, Yadin D, Harun-Khun S, Waldman M, Aravot D, Shainberg A, Eldar M, Hochhauser E, Arad M. Viral delivered gene therapy to treat catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (CPVT2) in mouse models. Heart Rhythm. 2017;14:1053-1060. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Mizusawa Y. Recent advances in genetic testing and counseling for inherited arrhythmias. J Arrhythm. 2016;32:389-397. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Lubitz SA, Ellinor PT. Next-generation sequencing for the diagnosis of cardiac arrhythmia syndromes. Heart Rhythm. 2015;12:1062-1070. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Giudicessi JR, Ackerman MJ. Genetic testing in heritable cardiac arrhythmia syndromes: differentiating pathogenic mutations from background genetic noise. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2013;28:63-71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Priori SG, Napolitano C, Tiso N, Memmi M, Vignati G, Bloise R, Sorrentino V, Danieli GA. Mutations in the cardiac ryanodine receptor gene (hRyR2) underlie catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Circulation. 2001;103:196-200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 931] [Cited by in RCA: 886] [Article Influence: 35.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Lahat H, Pras E, Olender T, Avidan N, Ben-Asher E, Man O, Levy-Nissenbaum E, Khoury A, Lorber A, Goldman B, Lancet D, Eldar M. A missense mutation in a highly conserved region of CASQ2 is associated with autosomal recessive catecholamine-induced polymorphic ventricular tachycardia in Bedouin families from Israel. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;69:1378-1384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 471] [Cited by in RCA: 459] [Article Influence: 18.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Swan H, Piippo K, Viitasalo M, Heikkilä P, Paavonen T, Kainulainen K, Kere J, Keto P, Kontula K, Toivonen L. Arrhythmic disorder mapped to chromosome 1q42-q43 causes malignant polymorphic ventricular tachycardia in structurally normal hearts. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;34:2035-2042. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 249] [Cited by in RCA: 213] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Laitinen PJ, Brown KM, Piippo K, Swan H, Devaney JM, Brahmbhatt B, Donarum EA, Marino M, Tiso N, Viitasalo M, Toivonen L, Stephan DA, Kontula K. Mutations of the cardiac ryanodine receptor (RyR2) gene in familial polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Circulation. 2001;103:485-490. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 502] [Cited by in RCA: 449] [Article Influence: 18.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Tiso N, Stephan DA, Nava A, Bagattin A, Devaney JM, Stanchi F, Larderet G, Brahmbhatt B, Brown K, Bauce B, Muriago M, Basso C, Thiene G, Danieli GA, Rampazzo A. Identification of mutations in the cardiac ryanodine receptor gene in families affected with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy type 2 (ARVD2). Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:189-194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 601] [Cited by in RCA: 534] [Article Influence: 21.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Priori SG, Napolitano C, Memmi M, Colombi B, Drago F, Gasparini M, DeSimone L, Coltorti F, Bloise R, Keegan R, Cruz Filho FE, Vignati G, Benatar A, DeLogu A. Clinical and molecular characterization of patients with catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Circulation. 2002;106:69-74. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 857] [Cited by in RCA: 812] [Article Influence: 33.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Mohamed U, Gollob MH, Gow RM, Krahn AD. Sudden cardiac death despite an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator in a young female with catecholaminergic ventricular tachycardia. Heart Rhythm. 2006;3:1486-1489. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Medeiros-Domingo A, Bhuiyan ZA, Tester DJ, Hofman N, Bikker H, van Tintelen JP, Mannens MM, Wilde AA, Ackerman MJ. The RYR2-encoded ryanodine receptor/calcium release channel in patients diagnosed previously with either catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia or genotype negative, exercise-induced long QT syndrome: a comprehensive open reading frame mutational analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:2065-2074. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 265] [Cited by in RCA: 270] [Article Influence: 15.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Sy RW, Gollob MH, Klein GJ, Yee R, Skanes AC, Gula LJ, Leong-Sit P, Gow RM, Green MS, Birnie DH, Krahn AD. Arrhythmia characterization and long-term outcomes in catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Heart Rhythm. 2011;8:864-871. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Ackerman MJ, Priori SG, Willems S, Berul C, Brugada R, Calkins H, Camm AJ, Ellinor PT, Gollob M, Hamilton R, Hershberger RE, Judge DP, Le Marec H, McKenna WJ, Schulze-Bahr E, Semsarian C, Towbin JA, Watkins H, Wilde A, Wolpert C, Zipes DP. HRS/EHRA expert consensus statement on the state of genetic testing for the channelopathies and cardiomyopathies this document was developed as a partnership between the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS) and the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA). Heart Rhythm. 2011;8:1308-1339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 761] [Cited by in RCA: 784] [Article Influence: 56.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Hayashi M, Denjoy I, Extramiana F, Maltret A, Buisson NR, Lupoglazoff JM, Klug D, Hayashi M, Takatsuki S, Villain E, Kamblock J, Messali A, Guicheney P, Lunardi J, Leenhardt A. Incidence and risk factors of arrhythmic events in catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Circulation. 2009;119:2426-2434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 391] [Cited by in RCA: 385] [Article Influence: 22.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Leenhardt A, Lucet V, Denjoy I, Grau F, Ngoc DD, Coumel P. Catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia in children. A 7-year follow-up of 21 patients. Circulation. 1995;91:1512-1519. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 637] [Cited by in RCA: 588] [Article Influence: 19.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Postma AV, Denjoy I, Kamblock J, Alders M, Lupoglazoff JM, Vaksmann G, Dubosq-Bidot L, Sebillon P, Mannens MM, Guicheney P, Wilde AA. Catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia: RYR2 mutations, bradycardia, and follow up of the patients. J Med Genet. 2005;42:863-870. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 208] [Cited by in RCA: 218] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 86. | van Langen IM, Hofman N, Tan HL, Wilde AA. Family and population strategies for screening and counselling of inherited cardiac arrhythmias. Ann Med. 2004;36 Suppl 1:116-124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 87. | Wehrens XH, Marks AR. Sudden unexplained death caused by cardiac ryanodine receptor (RyR2) mutations. Mayo Clin Proc. 2004;79:1367-1371. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 88. | Venetucci LA, Trafford AW, Eisner DA. Increasing ryanodine receptor open probability alone does not produce arrhythmogenic calcium waves: threshold sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium content is required. Circ Res. 2007;100:105-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 152] [Cited by in RCA: 161] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 89. | Maack C, Cremers B, Flesch M, Höper A, Südkamp M, Böhm M. Different intrinsic activities of bucindolol, carvedilol and metoprolol in human failing myocardium. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;130:1131-1139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |