Published online Feb 26, 2026. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v18.i2.110803

Revised: July 20, 2025

Accepted: November 21, 2025

Published online: February 26, 2026

Processing time: 238 Days and 18.6 Hours

The recent Cardiac Output in Patients with Small Annuli Undergoing Trans

To investigate the understudied role of atrial fibrillation (AF) on cardiac output in patients undergoing TAVI.

The COPS-TAVI study enrolled consecutive patients with severe aortic stenosis and small annuli who underwent successful TAVI. Cardiac output was measured using echocardiography within 4 weeks following TAVI. Data were analyzed according to the presence of AF and stratified by SEV or BEV.

A total of 138 patients were included in the analysis, of whom 22% had AF. Cardiac output was significantly lower in patients with AF compared to those without it (4.6 L/minute vs 5.3 L/minute, P = 0.02). Consistent with the main study findings, the difference in cardiac output was evident among patients without AF who underwent SEV vs BEV (P < 0.05). On the other hand, there was no difference in cardiac output in patients with AF, irrespective of the implanted platform (P > 0.05). There was no difference in clinical outcomes between the two groups.

Cardiac output, as measured by echocardiography, was larger in patients with small annuli who underwent TAVI procedure with SEV compared to BEV in patients without AF. This observation should be considered during procedural planning.

Core Tip: Cardiac output, as measured by echocardiography, was larger in patients with small annuli who underwent transcatheter aortic valve implantation procedure with self-expanding valves compared to balloon-expandable in patients without atrial fibrillation. This observation should be considered during procedural planning.

- Citation: Omari M, Ibrahim M, Abukhalaf O, Abdalwahab A, Edwards R, Das R, Zaman A, Farag M, Alkhalil M. Differences in cardiac output of patients undergoing trans-catheter aortic valve implantation according to their underlying rhythm. World J Cardiol 2026; 18(2): 110803

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v18/i2/110803.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v18.i2.110803

Aortic stenosis (AS) is one of the most prevalent valvular heart diseases, and its incidence markedly increases with age[1]. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) has emerged as a transformative treatment modality for patients with severe AS, particularly those deemed high-risk or inoperable for surgical valve replacement. Recent technological advances and improved imaging techniques have led to expanded indications for TAVI, extending its use to younger, lower-risk populations[2-4]. Consequently, the long-term performance and hemodynamic durability of TAVI prostheses are becoming increasingly important, particularly in patients with small annuli[5].

Post-procedural hemodynamics can be influenced by several factors, including prosthetic valve size and patient-specific factors such as body surface area. Specific anatomical challenges, such as small aortic annuli, typically defined as annular area < 430.0 mm2, are associated with higher transvalvular gradients and potentially worse outcomes following TAVI[5,6].

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common sustained arrhythmia in the general population with a prevalence of 0.5%-1%[7,8]. It is frequently observed in AS patients, occurring in up to 50% of individuals undergoing TAVI[9,10]. The coexistence of AF and AS introduces further complexity to hemodynamic evaluation and patient outcomes. AF has been associated with adverse outcomes in various AS cohorts[11-17], although some studies have failed to demonstrate its independent prognostic impact[18]. AF in AS patients is often a marker of advanced structural heart disease resulting from chronic pressure overload, diastolic dysfunction, and atrial remodeling[19,20].

Given the prevalence of AF in this population and its potential to alter hemodynamic parameters post-TAVI, there is a critical need to evaluate how different valve platforms perform in patients with AF vs sinus rhythm (SR). Therefore, the aim of this study was to compare the hemodynamic parameters after TAVI among patients with small annuli receiving self-expanding valves (SEVs) and balloon-expandable valves (BEVs), stratified according to their rhythm status (AF vs SR).

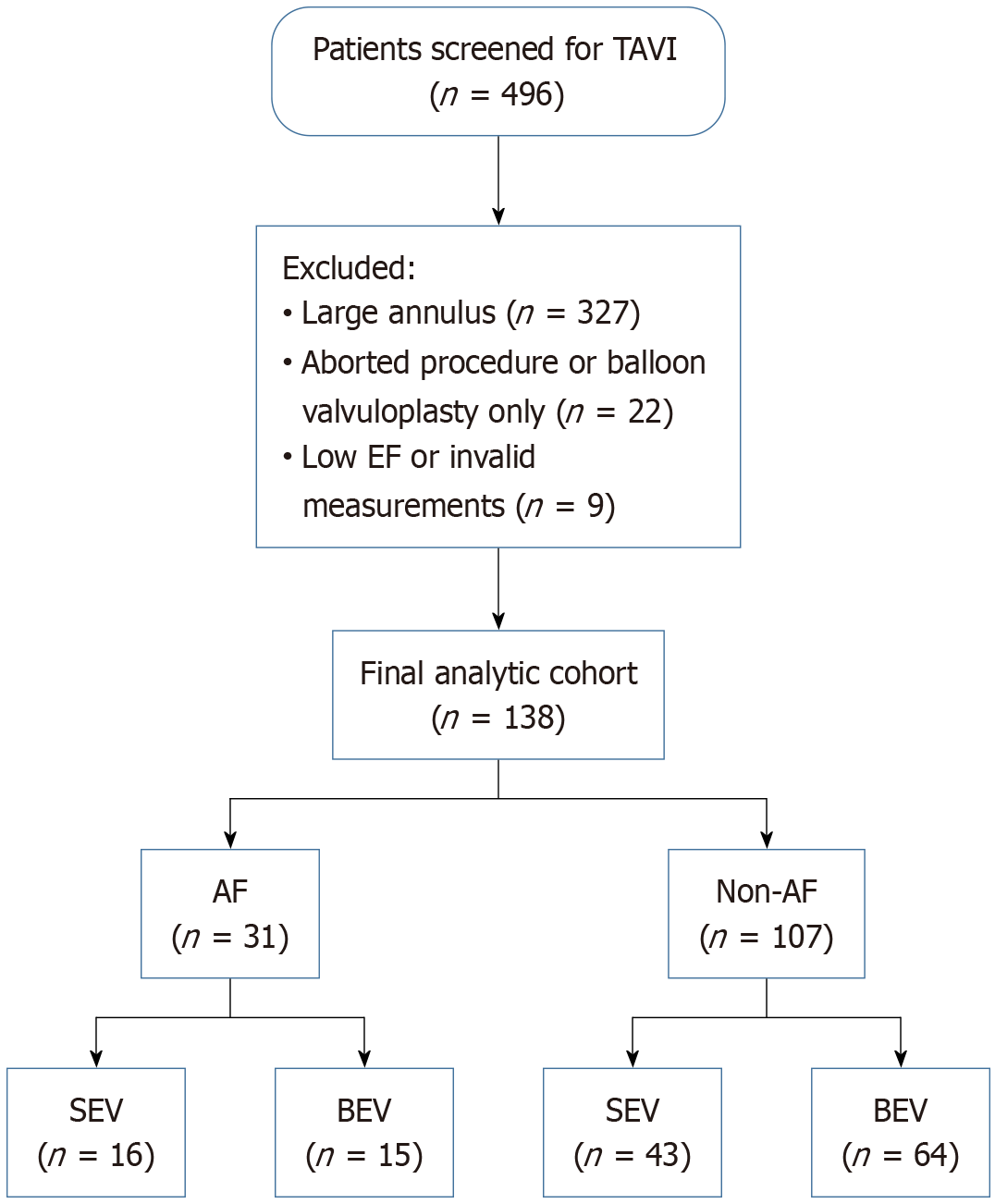

This is a sub-group analysis from the Cardiac Output in Patients with Small Annuli Undergoing Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation with Self-Expanding vs Balloon Expandable Valve (COPS-TAVI) study[21]. This was a single-center, observational study conducted at the Freeman Hospital between June 2020 and June 2022. The study enrolled consecutive patients with severe AS and small aortic annuli who underwent successful TAVI (Figure 1).

Patients with severe AS, defined according to the following transthoracic echocardiography criteria: Aortic valve area

AF was defined as any history of paroxysmal, persistent, or permanent AF confirmed by electrocardiography. New-onset AF following TAVI was recorded, but no such cases were observed in this cohort. SR was confirmed by routine electrocardiogram and clinical records at the time of hemodynamic evaluation.

Transthoracic echocardiogram was performed within 3 months before and within 4 weeks after the procedure. All of the studies were performed by accredited sonographers with extensive experience in scanning and reporting studies on patients with AS or post-TAVI. Left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) diameter was measured in mid-systole from the parasternal long-axis view, and LVOT velocity-time integral (VTI) was obtained via pulsed-wave Doppler in the apical 5-chamber view, as previously described[22-24]. Measurements were performed offline by an experienced, blinded sonographer. Echocardiographic parameters were collected at baseline (within 3 months before TAVI) and post-procedure (within 4 weeks). Table 1 presents pre-procedural values, while post-TAVI hemodynamic data are sum

| Variable | Whole cohort (n = 138) | Non-atrial fibrillation (n = 107) | Atrial fibrillation (n = 31) | P value |

| Age | 82 ± 6 | 82 ± 6 | 82 ± 6 | 0.77 |

| Male gender | 30 (22) | 26 (24) | 4 (13) | 0.18 |

| Body surface area | 1.8 ± 0.2 | 1.8 ± 0.2 | 1.8 ± 0.2 | 0.64 |

| Diabetes | 37 (27) | 25 (23) | 12 (39) | 0.089 |

| Smoker | 10 (7) | 10 (9) | 0 (0) | 0.077 |

| Hemoglobin | 121 ± 17 | 121 ± 17 | 121 ± 18 | 0.72 |

| Previous MI | 14 (10) | 10 (9) | 4 (13) | 0.56 |

| Chronic lung disease | 36 (26) | 27 (25) | 9 (29) | 0.67 |

| Previous CVA/TIA | 20 (15) | 14 (13) | 6 (19) | 0.38 |

| Previous cardiac surgery | 17 (12) | 10 (9) | 7 (23) | 0.048 |

| Valve size | 23 (23-26) | 23 (23-26) | 23 (23-26) | 0.50 |

| Peak gradient | 79 ± 25 | 77 ± 26 | 85 ± 22 | 0.17 |

| Mean gradient | 47 ± 18 | 46 ± 18 | 51 ± 15 | 0.25 |

| Valve area | 0.66 ± 0.16 | 0.68 ± 0.16 | 0.59 ± 0.15 | 0.005 |

| Low flow low gradient | 27 (20) | 23 (22) | 4 (13) | 0.29 |

| Preserved LV function | 112 (81) | 88 (82) | 21 (68) | 0.081 |

| Annulus area | 378 ± 39 | 377 ± 40 | 384 ± 38 | 0.37 |

| Variable | Non-atrial fibrillation | Atrial fibrillation | ||||

| BEV (n = 59) | SEV (n = 48) | P value | BEV (n = 20) | SEV (n = 11) | P value | |

| Peak gradient, mmHg | 29 ± 12 | 17 ± 8 | < 0.001 | 29 ± 16 | 21 ± 15 | 0.15 |

| Mean gradient, mmHg | 16 ± 7 | 9 ± 5 | < 0.001 | 17 ± 9 | 11 ± 8 | 0.09 |

| LVOT VTI, cm | 25 ± 6 | 26 ± 6 | 0.20 | 21 ± 4 | 22 ± 7 | 0.53 |

| LVOT diameter, cm | 1.92 ± 0.17 | 1.90 ± 0.17 | 0.57 | 1.94 ± 0.16 | 1.90 ± 0.22 | 0.54 |

| Heart rate beat per minute | 70 ± 11 | 76 ± 14 | 0.014 | 76 ± 16 | 73 ± 15 | 0.61 |

| Stroke volume, mL | 72 ± 18 | 75 ± 21 | 0.45 | 63 ± 16 | 65 ± 25 | 0.87 |

| Cardiac output, L/minute | 5.0 ± 1.3 | 5.7 ± 1.5 | 0.029 | 4.6 ± 0.9 | 4.5 ± 1.2 | 0.67 |

| Cardiac index, L/minute/m2 | 2.9 ± 0.8 | 3.2 ± 0.8 | 0.083 | 2.6 ± 0.7 | 2.5 ± 0.6 | 0.83 |

Patients with left ventricular ejection fraction < 30%, bradycardia (< 50 bpm), tachycardia (> 110 bpm), or physiologically implausible measurements (cardiac output < 2.5 L/minute or cardiac index < 1.5 L/minute/m2) were excluded. Normal cardiac output and cardiac index were defined as > 5.0 L/minute and > 2.2 L/minute/m2, respectively.

Categorical variables presented as n (%) and compared using the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. Continuous variables were assessed for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test, visual histograms, and skewness, then reported as mean ± SD or median with interquartile range and compared using unpaired t-tests or Mann-Whitney U tests as appropriate. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 28.0, with a P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Between June 2020 and June 2022, a total of 496 patients underwent transcatheter aortic valve procedures at the Freeman Hospital. Of these, 349 patients were excluded: 327 due to the presence of large aortic annuli and 22 due to either abandoned procedures or balloon valvuloplasty without valve implantation. This left 147 patients who underwent successful TAVI specifically for small annuli. From this subset, a further 9 patients were excluded: 3 due to severe left ventricular impairment, 3 due to severe heart rate abnormalities (including 2 with bradycardia and 1 with tachycardia), and 3 due to unreliable measurements of left ventricular outflow diameter or velocity-time interval. The final study cohort consisted of 138 patients. Similarly, there were 31 (22%) patients with AF and 107 (78%) without AF in this cohort. None of the patients developed new onset AF.

Table 1 presents the baseline clinical and echocardiographic characteristics of the 138 patients included in the study, stratified according to the presence or absence of AF. Post-TAVI measurements are provided in Table 2. The mean age of the cohort was 82 ± 6 years, with no significant difference between patients with and without AF in baseline clinical characteristics or conventional cardiovascular risk factors. Diabetes and smoking history were more frequent in patients with AF compared to those without, but this did not reach statistical significance.

On the other hand, a significantly higher proportion of patients with AF had a history of previous cardiac surgery (23% vs 9%, P = 0.048). Additionally, echocardiographic findings revealed a smaller valve area in the AF group (0.59 ± 0.15 cm2vs 0.68 ± 0.16 cm2, P = 0.005). While peak and mean gradients were slightly higher in the AF group, these differences were not statistically significant (P = 0.17 and P = 0.13, respectively). Among patients with AF (n = 31), 12 (39%) had paroxysmal AF, 10 (32%) had persistent AF, and 9 (29%) had permanent AF. None developed new-onset AF following the procedure.

There were no differences in other echocardiographic parameters, including left ventricle function, low-flow low-gradient status, or annulus area on computed tomography between the two groups. Patients with AF had lower cardiac output (4.6 ± 1.0 L vs 5.3 ± 1.5 L, P = 0.02) and lower cardiac index (2.6 ± 0.6 L/m2vs 3.0 ± 0.8 L/m2, P = 0.02) compared to those without AF. There was no significant difference in the mean heart rate between the two groups (75 ± 15 vs 73 ± 13, P = 0.55).

Out of 138 patients, 79 received BEV, and 59 patients received SEVs. Table 3 summarizes the clinical and echocardiographic features of patients stratified by AF status and type of implanted transcatheter heart valve (BEV or SEV).

| Variable | Non-atrial fibrillation | Atrial fibrillation | ||||

| BEV (n = 59) | SEV (n = 48) | P value | BEV (n = 20) | SEV (n = 11) | P value | |

| Age | 82 ± 6 | 82 ± 7 | 0.53 | 83 ± 4 | 79 ± 8 | 0.14 |

| Male gender | 15 (25) | 11 (23) | 0.76 | 2 (10) | 2 (18) | 0.52 |

| Body surface area | 1.8 ± 0.2 | 1.8 ± 0.2 | 0.47 | 1.8 ± 0.2 | 1.8 ± 0.3 | 0.52 |

| Diabetes | 14 (24) | 11 (23) | 0.92 | 8 (40) | 4 (36) | 0.84 |

| Smoker | 5 (9) | 5 (10) | 0.73 | 0 | 0 | |

| Hemoglobin | 123 ± 16 | 118 ± 17 | 0.12 | 120 ± 17 | 124 ± 20 | 0.59 |

| Previous MI | 5 (9) | 5 (10) | 0.73 | 4 (20) | 0 (0) | 0.11 |

| Chronic lung disease | 15 (25) | 12 (25) | 0.96 | 6 (30) | 3 (27) | 0.87 |

| Previous CVA/TIA | 8 (14) | 6 (13) | 0.87 | 5 (25) | 1 (9) | 0.28 |

| Previous cardiac surgery | 9 (15) | 1 (2) | 0.02 | 6 (30) | 1 (9) | 0.18 |

| Valve size | 23 (23-23) | 26 (26-29) | < 0.001 | 23 (23-26) | 26 (26-29) | < 0.001 |

| Peak gradient | 75 ± 23 | 80 ± 30 | 0.26 | 84 ± 19 | 86 ± 26 | 0.80 |

| Mean gradient | 45 ± 15 | 48 ± 21 | 0.40 | 51 ± 13 | 51 ± 21 | 0.99 |

| Valve area | 0.65 ± 0.17 | 0.71 ± 0.15 | 0.09 | 0.56 ± 0.14 | 0.63 ± 0.16 | 0.23 |

| Low flow low gradient | 15 (25) | 8 (17) | 0.27 | 2 (10) | 2 (18) | 0.52 |

| Preserved LV function | 44 (75) | 44 (92) | 0.021 | 14 (70) | 7 (64) | 0.72 |

| Annulus area | 379 ± 36 | 374 ± 44 | 0.60 | 388 ± 37 | 380 ± 41 | 0.56 |

Among patients without AF (n = 107), there were 59 BEV recipients and 48 SEV recipients. Baseline characteristics, including age, gender distribution, body surface area, diabetes, smoking status, hemoglobin levels, and comorbidities such as prior myocardial infarction, chronic lung disease, and cerebrovascular events, were similar between the BEV and SEV groups (all P > 0.05).

SEV recipients had a significantly higher peak and mean gradients (80 ± 30 mmHg vs 75 ± 20 mmHg and 48 ± 21 mmHg vs 45 ± 15 mmHg, respectively) and a trend toward a larger valve area (0.71 ± 0.15 cm2vs 0.65 ± 0.17 cm2, P = 0.09). Left ventricular function was preserved in 92% of SEV patients compared to 75% of BEV patients (P = 0.021).

In patients with AF (n = 31), 20 received BEVs, and 11 received SEVs. Both subgroups were comparable in terms of age, gender, body surface area, and most comorbid conditions (all P > 0.05). The prevalence of previous cardiac surgery and preserved left ventricular function was not significantly different between BEV and SEV recipients (30% vs 9% and 70% vs 64%, respectively). The between-valve difference in cardiac output among AF patients corresponded to a small effect size (Cohen’s d = 0.09; 95% confidence interval: -0.54 to 0.71), underscoring the low likelihood of a clinically meaningful disparity. There were no significant differences between SEV and BEV groups in terms of hemodynamic performance (peak gradient, mean gradient, valve area).

Following TAVI procedure, patients receiving BEVs (n = 59) demonstrated significantly higher peak and mean transvalvular gradients compared to those receiving SEVs (29 ± 12 mmHg vs 17 ± 8 mmHg and 16 ± 7 mmHg vs 9 ± 5 mmHg, respectively; both P < 0.001). LVOT VTI, LVOT diameter, and stroke volume were similar between groups (all P > 0.05).

Despite similar stroke volumes, BEV patients exhibited significantly lower cardiac output than SEV recipients (5.0 ± 1.3 L/minute vs 5.7 ± 1.5 L/minute, P = 0.029). A trend toward a lower cardiac index in BEV recipients was observed (2.9 ± 0.8 L/minute/m2vs 3.2 ± 0.8 L/minute/m2, P = 0.083), although this difference did not reach statistical significance.

The Table 2 presents the post-procedural echocardiographic parameters of patients who underwent TAVI, categorized by the type of valve implanted - BEV vs SEV - and further stratified by AF status.

Among patients with AF, there were no statistical differences between BEV (n = 20) and SEV (n = 11) recipients across all echocardiographic parameters. Peak and mean gradients were numerically higher in SEV recipients (21 ± 15 mmHg vs 29 ± 16 mmHg, P = 0.15; and 11 ± 8 mmHg vs 17 ± 9 mmHg, P = 0.09, respectively), but these differences did not reach statistical significance.

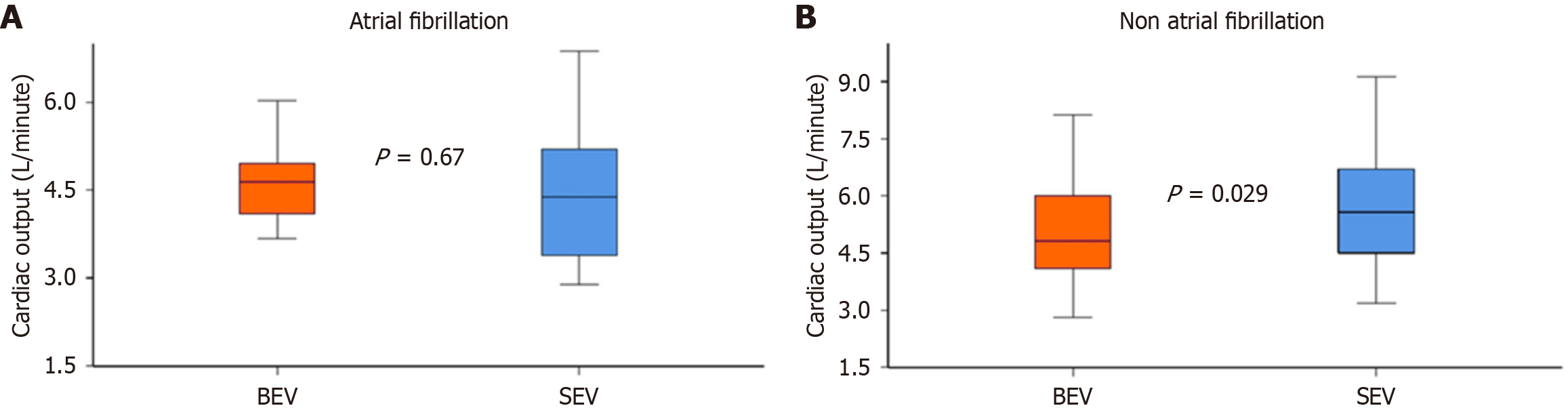

Stroke volume, LVOT VTI, and LVOT diameter were comparable between the groups (P > 0.5). Cardiac output and cardiac index were numerically lower in SEV patients with AF, but the differences were not statistically significant (cardiac output: 4.5 ± 1.2 L/minute vs 4.6 ± 0.9 L/minute, P = 0.67; cardiac index: 2.5 ± 0.6 L/minute/m2vs 2.6 ± 0.7 L/minute/m2, P = 0.83; Figure 2A).

On the other hand, patients without AF who underwent SEV demonstrated larger cardiac output (5.7 ± 1.5 L/minute vs 5.0 ± 1.3 L/minute, P = 0.029; Figure 2B) Similarly, they had larger cardiac index (3.2 ± 0.8 L/minute/m2vs 2.9 ± 0.8 L/minute/m2, P = 0.083), although this did not reach statistical significance.

This study focused exclusively on patients with severe AS and small annuli undergoing TAVI, a subgroup known to be at higher risk of prosthesis-patient mismatch and higher residual gradients. Therefore, all findings should be interpreted within this anatomical context rather than extrapolated to the general TAVI population. Given the modest sample size and single-center nature of this subgroup analysis, these observations should be viewed as exploratory and interpreted cautiously.

The principal findings of this exploratory analysis are as follows: (1) Among patients with small aortic annuli undergoing TAVI, those with AF exhibited lower cardiac output and cardiac index compared to patients in SR, despite comparable heart rates; (2) Within the SR subgroup, recipients of SEVs demonstrated higher cardiac output and a trend toward higher cardiac index compared to those receiving BEVs; and (3) Among patients with AF, hemodynamic parameters were similar between valve platforms, although interpretation is limited by small sample size and heterogeneous AF subtypes. Given the relatively small number of patients with AF in this analysis, the findings should be interpreted as exploratory and hypothesis-generating. The absence of a statistically significant difference should not be interpreted as evidence of equivalence but rather as ‘no difference detected’ within the limits of the current sample size.

TAVI has emerged as the default strategy and become a standard of care for patients with symptomatic severe AS[25,26]. AF is a common arrhythmia either before or as a complication following TAVI or surgical aortic valve replacement in patients with severe AS[27-30]. The pressure overload on the left heart system due to AS is related to a higher incidence of AF. Furthermore, the TAVI procedure itself could be associated with a systemic inflammatory response and oxidative stress, resulting in slow atrial conduction, short refractoriness, and endo-epicardial dissociation that can, in turn, induce re-entry, ectopic activity, and new-onset AF[10].

Theoretically, the atrioventricular desynchrony and irregular ventricular contraction caused by AF could impair heart function of patients with severe AS. In this regard, AF has been associated with poorer clinical outcomes than those found in patients with a SR after TAVI[31-34]. Many studies, registries, and subsequent meta-analyses have consistently shown that both pre-existing and new-onset AF post-TAVI are associated with poor outcomes, including increased mortality, stroke, prolonged hospitalization, and higher rates of permanent pacemaker implantation[35-37]. Similarly, new-onset AF following surgical aortic valve replacement is significantly associated with increased long-term risk of mortality independent of the preoperative disease severity[29]. There are several factors that have been linked to the development of new-onset AF, including advanced age, higher New York Heart Association class, non-transfemoral access, and the need for balloon post-dilation[35]. While these studies underscore AF as a potent marker of frailty and cardiac compromise, the causality between AF and poor outcomes remains debated.

According to our observations, patients with AF were more likely to have a history of previous cardiac surgery and a trend toward higher diabetes prevalence and reduced left ventricular function. Notably, patients with AF had comparable mean and peak gradients but demonstrated smaller valve area compared to those without AF. One potential mechanism is related to heart rate variability associated with AF and its effect on flow across the aortic valve. The reduction in flow secondary to losing ‘atrial kick’ in patients with AF would inevitably contribute to the bigger discordance in this group compared to patients without AF. Importantly, we attempted to address this by averaging few heart beats when measuring stroke volume in this study.

The current study highlights the nuanced interplay between atrial rhythm status and valve platform selection in shaping post-TAVI hemodynamic outcomes. Our findings support previous observations suggesting that SEVs may confer superior hemodynamic performance in terms of transvalvular gradients and cardiac output in patients undergoing SEV, particularly in patients with SR[21,38,39]. Notably, in our non-AF subgroup, SEV recipients demonstrated signi

The primary focus of this study was on post-procedural hemodynamic performance rather than clinical outcomes. Therefore, the findings should not be extrapolated to predict long-term clinical events, which were beyond the scope of this analysis. Interestingly, despite a smaller pre-procedural aortic valve area among AF patients, peak and mean gradients were not significantly different compared with the sinus-rhythm cohort. This apparent discrepancy may be explained by arrhythmia-induced beat-to-beat variability in transvalvular flow, which can cause under- or over-estimation of instantaneous gradients on Doppler assessment. Furthermore, chronic AF is associated with reduced left-ventricular compliance and altered loading conditions that may attenuate gradient-area concordance. These factors, together with differences in ventricular remodeling and stroke-volume variability, likely contribute to the observed gradient-area mismatch.

The diminished stroke volume and cardiac output observed in AF patients may be attributed to impaired atrial contraction and suboptimal ventricular filling, which are hallmarks of this arrhythmia[19]. These physiological disturbances likely obscure the hemodynamic benefits conferred by specific valve designs. The attenuated performance of SEVs in AF patients may reflect the pathophysiologic effects of AF, particularly atrioventricular asynchrony, irregular ventricular filling, impaired atrial contraction, and suboptimal ventricular filling due to impaired diastolic filling dynamics[19]. These factors may mask the intrinsic hemodynamic advantages of SEVs, such as larger effective orifice areas and lower gradients.

This was also evident in other echocardiographic parameters beyond cardiac output, such as valvular gradients. From a clinical standpoint, these results underscore the importance of rhythm monitoring in TAVI patients and suggest that valve selection should be individualized not only based on anatomical and procedural factors but also considering rhythm status. For patients in SR, especially those with small annuli or borderline cardiac output, the use of SEVs might offer a hemodynamic advantage. In contrast, in AF patients, especially those with longstanding arrhythmia and compro

Our study has several limitations that need to be acknowledged. Firstly, this was a single-center retrospective sub-group analysis with inherent limitations associated with the current design. Secondly, the measurement of LVOT has been shown to affect stroke volume and cardiac output, particularly in patients with AF. The current analysis attempted to overcome this issue by averaging LVOT VTI from 5 beats to minimize variations secondary to irregular cardiac cycle. Finally, the number of patients with AF was relatively small, and type 2 errors cannot be excluded when comparing hemodynamic outcomes between SEV and BEV platforms. The small sample size did not allow for adequate control of confounders between the two groups. Furthermore, due to sample constraints, multivariable or propensity-score analyses to adjust for baseline imbalances (e.g., prior cardiac surgery, smaller valve area) were not performed; thus, residual confounding cannot be excluded. However, the lack of difference was consistent across all echocardiographic parameters make this less likely. Importantly, the AF subgroup was relatively small, and this exploratory analysis may have been underpowered to detect clinically meaningful differences. Hence, our findings should be viewed as hypothesis-generating and validated in larger, prospective studies.

Another limitation is the lack of formal reproducibility assessment (intra-observer and inter-observer variability) for echocardiographic measurements, particularly within the AF subgroup. Because of the limited number of patients, multivariable regression analysis to identify independent determinants of cardiac output was not feasible. Future studies with larger sample sizes should apply multivariable modeling to clarify whether valve platform independently predicts post-TAVI hemodynamic performance.

Cardiac output, as measured by echocardiography, was larger in patients with small annuli who underwent TAVI procedure with SEV compared to BEV in patients without AF. Future prospective studies are needed to confirm these findings and clarify whether rhythm-guided valve selection could improve outcomes in TAVI recipients.

| 1. | Iung B, Baron G, Butchart EG, Delahaye F, Gohlke-Bärwolf C, Levang OW, Tornos P, Vanoverschelde JL, Vermeer F, Boersma E, Ravaud P, Vahanian A. A prospective survey of patients with valvular heart disease in Europe: The Euro Heart Survey on Valvular Heart Disease. Eur Heart J. 2003;24:1231-1243. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2255] [Cited by in RCA: 2298] [Article Influence: 99.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Leon MB, Smith CR, Mack MJ, Makkar RR, Svensson LG, Kodali SK, Thourani VH, Tuzcu EM, Miller DC, Herrmann HC, Doshi D, Cohen DJ, Pichard AD, Kapadia S, Dewey T, Babaliaros V, Szeto WY, Williams MR, Kereiakes D, Zajarias A, Greason KL, Whisenant BK, Hodson RW, Moses JW, Trento A, Brown DL, Fearon WF, Pibarot P, Hahn RT, Jaber WA, Anderson WN, Alu MC, Webb JG; PARTNER 2 Investigators. Transcatheter or Surgical Aortic-Valve Replacement in Intermediate-Risk Patients. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1609-1620. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3232] [Cited by in RCA: 3947] [Article Influence: 394.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 3. | Mack MJ, Leon MB, Thourani VH, Pibarot P, Hahn RT, Genereux P, Kodali SK, Kapadia SR, Cohen DJ, Pocock SJ, Lu M, White R, Szerlip M, Ternacle J, Malaisrie SC, Herrmann HC, Szeto WY, Russo MJ, Babaliaros V, Smith CR, Blanke P, Webb JG, Makkar R; PARTNER 3 Investigators. Transcatheter Aortic-Valve Replacement in Low-Risk Patients at Five Years. N Engl J Med. 2023;389:1949-1960. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 321] [Cited by in RCA: 392] [Article Influence: 130.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Forrest JK, Deeb GM, Yakubov SJ, Gada H, Mumtaz MA, Ramlawi B, Bajwa T, Teirstein PS, Tchétché D, Huang J, Reardon MJ; Evolut Low Risk Trial Investigators. 4-Year Outcomes of Patients With Aortic Stenosis in the Evolut Low Risk Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2023;82:2163-2165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 142] [Article Influence: 47.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Abdalwahab A, Omari M, Alkhalil M. Aortic Valve Intervention in Patients with Aortic Stenosis and Small Annulus. Rev Cardiovasc Med. 2025;26:26738. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Angellotti D, Manzo R, Castiello DS, Immobile Molaro M, Mariani A, Iapicca C, Nappa D, Simonetti F, Avvedimento M, Leone A, Canonico ME, Spaccarotella CAM, Franzone A, Ilardi F, Esposito G, Piccolo R. Hemodynamic Performance of Transcatheter Aortic Valves: A Comprehensive Review. Diagnostics (Basel). 2023;13:1731. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Chugh SS, Blackshear JL, Shen WK, Hammill SC, Gersh BJ. Epidemiology and natural history of atrial fibrillation: clinical implications. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37:371-378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 535] [Cited by in RCA: 573] [Article Influence: 22.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Gersh BJ, Tsang TS, Seward JB. The changing epidemiology and natural history of nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: clinical implications. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 2004;115:149-160; discussion159. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Rudolph TK, Messika-Zeitoun D, Frey N, Thambyrajah J, Serra A, Schulz E, Maly J, Aiello M, Lloyd G, Bortone AS, Clerici A, Delle-Karth G, Rieber J, Indolfi C, Mancone M, Belle L, Lauten A, Arnold M, Bouma BJ, Lutz M, Deutsch C, Kurucova J, Thoenes M, Bramlage P, Steeds RP. Impact of selected comorbidities on the presentation and management of aortic stenosis. Open Heart. 2020;7:e001271. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Tarantini G, Mojoli M, Urena M, Vahanian A. Atrial fibrillation in patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve implantation: epidemiology, timing, predictors, and outcome. Eur Heart J. 2017;38:1285-1293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Levy F, Rusinaru D, Maréchaux S, Charles V, Peltier M, Tribouilloy C. Determinants and prognosis of atrial fibrillation in patients with aortic stenosis. Am J Cardiol. 2015;116:1541-1546. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Chew NWS, Ngiam JN, Tan BY, Sia CH, Sim HW, Kong WKF, Tay ELW, Yeo TC, Poh KK. Differences in Clinical and Echocardiographic Profiles and Outcomes of Patients With Atrial Fibrillation Versus Sinus Rhythm in Medically Managed Severe Aortic Stenosis and Preserved Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction. Heart Lung Circ. 2020;29:1773-1781. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Delesalle G, Bohbot Y, Rusinaru D, Delpierre Q, Maréchaux S, Tribouilloy C. Characteristics and Prognosis of Patients With Moderate Aortic Stenosis and Preserved Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8:e011036. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 13.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kubala M, Bohbot Y, Rusinaru D, Maréchaux S, Diouf M, Tribouilloy C. Atrial fibrillation in severe aortic stenosis: Prognostic value and results of aortic valve replacement. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2023;166:771-779. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Moretti M, Fabris E, Morosin M, Merlo M, Barbati G, Pinamonti B, Gatti G, Pappalardo A, Sinagra G. Prognostic significance of atrial fibrillation and severity of symptoms of heart failure in patients with low gradient aortic stenosis and preserved left ventricular ejection fraction. Am J Cardiol. 2014;114:1722-1728. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Greve AM, Gerdts E, Boman K, Gohlke-Baerwolf C, Rossebø AB, Nienaber CA, Ray S, Egstrup K, Pedersen TR, Køber L, Willenheimer R, Wachtell K. Prognostic importance of atrial fibrillation in asymptomatic aortic stenosis: the Simvastatin and Ezetimibe in Aortic Stenosis study. Int J Cardiol. 2013;166:72-76. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Burup Kristensen C, Jensen JS, Sogaard P, Carstensen HG, Mogelvang R. Atrial fibrillation in aortic stenosis--echocardiographic assessment and prognostic importance. Cardiovasc Ultrasound. 2012;10:38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Zhang H, El-Am EA, Thaden JJ, Pislaru SV, Scott CG, Krittanawong C, Chahal AA, Breen TJ, Eleid MF, Melduni RM, Greason KL, McCully RB, Enriquez-Sarano M, Oh JK, Pellikka PA, Nkomo VT. Atrial fibrillation is not an independent predictor of outcome in patients with aortic stenosis. Heart. 2020;106:280-286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Tsang TS, Barnes ME, Bailey KR, Leibson CL, Montgomery SC, Takemoto Y, Diamond PM, Marra MA, Gersh BJ, Wiebers DO, Petty GW, Seward JB. Left atrial volume: important risk marker of incident atrial fibrillation in 1655 older men and women. Mayo Clin Proc. 2001;76:467-475. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 440] [Cited by in RCA: 477] [Article Influence: 19.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Lorell BH, Carabello BA. Left ventricular hypertrophy: pathogenesis, detection, and prognosis. Circulation. 2000;102:470-479. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 680] [Cited by in RCA: 742] [Article Influence: 28.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 21. | Omari M, Durrani T, Diaz Nuila ME, Thompson A, Irvine T, Edwards R, Das R, Zaman A, Farag M, Alkhalil M. Cardiac output in patients with small annuli undergoing transcatheter aortic valve implantation with self-expanding versus balloon expandable valve (COPS-TAVI). Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2025;73:15-22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Al-Atta A, Farag M, Jeyalan V, Gazzal Asswad A, Thompson A, Irvine T, Edwards R, Das R, Zaman A, Alkhalil M. Low Transvalvular Flow Rate in Patients Undergoing Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation (TAVI) Is a Predictor of Mortality: The TFR-TAVI Study. Heart Lung Circ. 2023;32:1489-1499. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Jeyalan V, Al-Atta A, Das R, Edwards R, Zaman A, Alkhalil M. Prognostic Role of Sex-Specific Flow Threshold in Patients UndergoingTranscatheter Aortic Valve Replacement. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2022;36:164-165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Alkhalil M, Brennan P, McQuillan C, Jeganathan R, Manoharan G, Owens CG, Spence MS. Flow, Reflected by Stroke Volume Index, Is a Risk Marker in High-Gradient Aortic Stenosis Patients Undergoing Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement. Can J Cardiol. 2020;36:112-118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Vahanian A, Beyersdorf F, Praz F, Milojevic M, Baldus S, Bauersachs J, Capodanno D, Conradi L, De Bonis M, De Paulis R, Delgado V, Freemantle N, Gilard M, Haugaa KH, Jeppsson A, Jüni P, Pierard L, Prendergast BD, Sádaba JR, Tribouilloy C, Wojakowski W; ESC/EACTS Scientific Document Group. 2021 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2021;60:727-800. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 404] [Article Influence: 80.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Erwin JP 3rd, Gentile F, Jneid H, Krieger EV, Mack M, McLeod C, O'Gara PT, Rigolin VH, Sundt TM 3rd, Thompson A, Toly C. 2020 ACC/AHA Guideline for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2021;143:e35-e71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 303] [Cited by in RCA: 680] [Article Influence: 136.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Mentias A, Saad M, Girotra S, Desai M, Elbadawi A, Briasoulis A, Alvarez P, Alqasrawi M, Giudici M, Panaich S, Horwitz PA, Jneid H, Kapadia S, Vaughan Sarrazin M. Impact of Pre-Existing and New-Onset Atrial Fibrillation on Outcomes After Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;12:2119-2129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Sannino A, Gargiulo G, Schiattarella GG, Perrino C, Stabile E, Losi MA, Galderisi M, Izzo R, de Simone G, Trimarco B, Esposito G. A meta-analysis of the impact of pre-existing and new-onset atrial fibrillation on clinical outcomes in patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve implantation. EuroIntervention. 2016;12:e1047-e1056. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Filardo G, Hamilton C, Hamman B, Hebeler RF Jr, Adams J, Grayburn P. New-onset postoperative atrial fibrillation and long-term survival after aortic valve replacement surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;90:474-479. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Jørgensen TH, Thygesen JB, Thyregod HG, Svendsen JH, Søndergaard L. New-onset atrial fibrillation after surgical aortic valve replacement and transcatheter aortic valve implantation: a concise review. J Invasive Cardiol. 2015;27:41-47. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Chopard R, Teiger E, Meneveau N, Chocron S, Gilard M, Laskar M, Eltchaninoff H, Iung B, Leprince P, Chevreul K, Prat A, Lievre M, Leguerrier A, Donzeau-Gouge P, Fajadet J, Mouillet G, Schiele F; FRANCE-2 Investigators. Baseline Characteristics and Prognostic Implications of Pre-Existing and New-Onset Atrial Fibrillation After Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation: Results From the FRANCE-2 Registry. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;8:1346-1355. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Stortecky S, Buellesfeld L, Wenaweser P, Heg D, Pilgrim T, Khattab AA, Gloekler S, Huber C, Nietlispach F, Meier B, Jüni P, Windecker S. Atrial fibrillation and aortic stenosis: impact on clinical outcomes among patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2013;6:77-84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Shahim B, Malaisrie SC, George I, Thourani VH, Biviano AB, Russo M, Brown DL, Babaliaros V, Guyton RA, Kodali SK, Nazif TM, Kapadia S, Pibarot P, McCabe JM, Williams M, Genereux P, Lu M, Yu X, Alu M, Webb JG, Mack MJ, Leon MB, Kosmidou I. Postoperative Atrial Fibrillation or Flutter Following Transcatheter or Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement: PARTNER 3 Trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;14:1565-1574. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Mojoli M, Gersh BJ, Barioli A, Masiero G, Tellaroli P, D'Amico G, Tarantini G. Impact of atrial fibrillation on outcomes of patients treated by transcatheter aortic valve implantation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am Heart J. 2017;192:64-75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Tarantini G, Mojoli M, Windecker S, Wendler O, Lefèvre T, Saia F, Walther T, Rubino P, Bartorelli AL, Napodano M, D'Onofrio A, Gerosa G, Iliceto S, Vahanian A. Prevalence and Impact of Atrial Fibrillation in Patients With Severe Aortic Stenosis Undergoing Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement: An Analysis From the SOURCE XT Prospective Multicenter Registry. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;9:937-946. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 153] [Article Influence: 15.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Nso N, Emmanuel K, Nassar M, Bhangal R, Enoru S, Iluyomade A, Marmur JD, Ilonze OJ, Thambidorai S, Ayinde H. Impact of new-onset versus pre-existing atrial fibrillation on outcomes after transcatheter aortic valve replacement/implantation. Int J Cardiol Heart Vasc. 2022;38:100910. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Ryan T, Grindal A, Jinah R, Um KJ, Vadakken ME, Pandey A, Jaffer IH, Healey JS, Belley-Coté ÉP, McIntyre WF. New-Onset Atrial Fibrillation After Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2022;15:603-613. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (14)] |

| 38. | Regazzoli D, Chiarito M, Cannata F, Pagnesi M, Miura M, Ziviello F, Picci A, Reifart J, De Marco F, Bedogni F, Adamo M, Curello S, Teles R, Taramasso M, Barbanti M, Tamburino C, Stefanini GG, Mangieri A, Giannini F, Pagnotta PA, Maisano F, Kim WK, Van Mieghem NM, Colombo A, Reimers B, Latib A; TAVI-SMALL Investigators. Transcatheter Self-Expandable Valve Implantation for Aortic Stenosis in Small Aortic Annuli: The TAVI-SMALL Registry. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2020;13:196-206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Mauri V, Kim WK, Abumayyaleh M, Walther T, Moellmann H, Schaefer U, Conradi L, Hengstenberg C, Hilker M, Wahlers T, Baldus S, Rudolph V, Madershahian N, Rudolph TK. Short-Term Outcome and Hemodynamic Performance of Next-Generation Self-Expanding Versus Balloon-Expandable Transcatheter Aortic Valves in Patients With Small Aortic Annulus: A Multicenter Propensity-Matched Comparison. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2017;10:e005013. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |