INTRODUCTION

The interface between cardiology and nephrology is frequently marked by a perceived tension, particularly regarding the management of fluid balance in cardiorenal dysfunction. This dichotomy, commonly echoed in medical training environments and amplified on social media, portrays cardiologists as proponents of aggressive diuresis despite worsening kidney function, while nephrologists are seen as favoring fluid administration in response to rising serum creatinine. Although these views stem from historical practice patterns, they are overly simplistic, potentially misleading, and may contribute to suboptimal patient care. Such binary narratives have perpetuated common misconceptions, including the belief that diuretics are intrinsically nephrotoxic or that all cases of acute kidney injury result from hypovolemia. Compounding the problem, a host of persistent myths surrounding diuretic use continue to influence clinical decision-making, further clouding the appropriate management of fluid status in this complex patient population[1]. In clinical practice, most patients with heart failure demonstrate some degree of renal impairment, and the reverse is also true. This overlap, commonly referred to as cardiorenal syndrome, reflects a complex interplay of reduced cardiac output, neurohormonal activation, fluid overload, and venous congestion, where both insufficient and excessive diuresis may lead to adverse outcomes. These intricacies highlight the importance of individualized treatment strategies guided by objective hemodynamic assessment rather than fixed assumptions. This review aims to reframe current approaches to cardiorenal medicine by challenging entrenched myths, such as the notion that "the heart likes it dry and the kidneys like it wet", and by promoting a unified, physiology-based framework that encourages collaboration between specialties.

This narrative review synthesizes key concepts and evidence shaping the evolving understanding of cardiorenal physiology and bedside hemodynamic assessment. Literature was selected through targeted searches in PubMed and Google Scholar, supplemented by manual screening of reference lists. The review prioritizes clinically impactful studies, expert opinions, and physiologic investigations relevant to nephrology, cardiology, and critical care. The intent is not to provide a systematic or exhaustive review, but rather to offer a practical, concept-driven framework.

EVOLVING CONCEPTS IN CARDIORENAL MEDICINE: REFRAMING THE FOCUS FROM FORWARD FLOW TO CONGESTION

The pathophysiology of cardiorenal syndrome has traditionally been viewed through the lens of reduced cardiac output. This long-standing model suggests that diminished forward flow leads to decreased renal perfusion, impaired glomerular filtration, and a subsequent rise in serum creatinine. As a result, therapeutic strategies have historically focused on augmenting cardiac output through interventions such as intravenous fluids, vasodilators, or inotropes to restore renal perfusion. However, the forward flow-focused framework, often referred to as the underfill hypothesis, does not fully account for the complexity of renal dysfunction in heart failure. Emerging evidence has begun to challenge the assumption that reduced cardiac output or index (CI) is the dominant driver.

An analysis utilizing the registry and randomized arms of the Evaluation Study of Congestive Heart Failure and Pulmonary Artery Catheterization Effectiveness (ESCAPE) examined this relationship in a cohort of 575 patients undergoing pulmonary artery catheterization[2]. Across multiple subgroups and clinical settings, the study found no meaningful association between CI and renal function. In fact, a weak but statistically significant inverse correlation was observed between CI and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), with higher CI paradoxically linked to worse eGFR. There was no association between CI and other renal markers such as blood urea nitrogen (BUN) or the BUN-to-creatinine ratio, and no threshold or nonlinear relationship could be identified. Longitudinal analysis of patients with serial measurements also failed to show any within-subject relationship between changes in CI and renal function or the development of worsening renal function. These findings suggest that reduced forward flow, as measured by CI, is unlikely to be the primary driver of kidney dysfunction in hospitalized patients with heart failure, further supporting the growing emphasis on venous congestion and other mechanisms in the pathophysiology of cardiorenal syndrome.

Earlier evidence pointing in this direction came from a 2010 analysis of the Cardiac Insufficiency Bisoprolol Study II registry, which evaluated 2647 patients with NYHA class III or IV heart failure. This study examined the association between clinical signs of congestion, such as elevated jugular venous pressure, orthopnea, ascites, and peripheral edema, renal function, and clinical outcomes. Nearly half of the patients exhibited at least one sign of congestion, and 10% had more than three. Patients with clinical congestion had significantly lower eGFR, and this association remained significant after multivariable adjustment. Moreover, mortality rates increased progressively with the number of congestion signs, nearly doubling in those with three or more signs compared to those without congestion. Even a single sign of congestion was associated with increased risk of death and adverse outcomes[3]. The same investigative group conducted a large observational study to examine the relationship between invasively measured central venous pressure (CVP), renal function, and long-term outcomes. The study included 2557 patients who underwent right heart catheterization at a single center over a 17-year period, encompassing a broad spectrum of cardiovascular conditions. The analysis revealed a significant inverse association between CVP and eGFR, suggesting that higher CVP was linked with worse renal function. Although CI was also modestly correlated with eGFR, multivariate analysis confirmed that CVP remained independently associated with renal impairment. Importantly, CVP was not only a marker of worsening kidney function but also an independent predictor of long-term mortality. Over a median follow-up of 10.7 years, elevated CVP was associated with an increased risk of death, with a hazard ratio of 1.03 per mm Hg increase[4]. Similar findings were observed in a cohort of patients with acute decompensated heart failure admitted to the intensive care unit. Patients who developed worsening renal function (WRF) had significantly higher CVP both at admission and after intensive therapy. Notably, achieving a CVP below 8 mmHg was associated with a lower risk of WRF, and this relationship held true regardless of systemic blood pressure, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure, CI, or baseline renal function[5].

These observations are indeed supported by fundamental hemodynamic principles. Renal perfusion pressure is the difference between mean arterial pressure and CVP; when CVP is elevated, perfusion pressure decreases, leading to impaired renal blood flow. In addition, activation of the renin angiotensin aldosterone system, sodium and water retention, interstitial edema, endothelial dysfunction, and increased intra-abdominal pressure all contribute to elevated pressure within the encapsulated kidney. This so-called renal tamponade further compromises kidney function. In turn, declining renal function worsens fluid retention, perpetuating a vicious cycle of congestion and organ dysfunction[6,7]. In fact, congestive nephropathy is not a new concept, but one that has largely been lost in clinical translation over time. In an elegant mammalian study published in 1931 in the Journal of Physiology, Winton[8] demonstrated that hypervolemia and acute elevations in renal venous pressure led to marked azotemia, accompanied by reduced GFR, decreased urine output, and sodium retention. Notably, cardiac output, renal blood flow, and mean arterial pressure were maintained within normal limits, and renal function remained stable until renal vein pressure exceeded a threshold of 18 to 20 mmHg. Beyond this point, renal function progressively declined. Importantly, both urine output and GFR improved once renal vein pressure was normalized, underscoring the direct and reversible impact of venous congestion on kidney function.

In a separate analysis using the ESCAPE registry, persistent congestion at discharge accompanied by WRF was associated with worse outcomes compared to patients without either condition[2]. However, among those who were effectively decongested by discharge, in-hospital WRF was not significantly linked to 180-day all-cause mortality, regardless of whether decongestion was assessed using hemodynamic, clinical, or estimated plasma volume markers. These findings, supported by additional evidence, highlight the importance of achieving meaningful decongestion when evaluating patients with WRF. On the flip side, not all rises in creatinine should be dismissed as benign. A rising creatinine despite clinical improvement and apparent decongestion may unmask an underlying structural kidney injury or reflect excessive diuresis[9,10]. Rather than relying solely on changes in creatinine, clinicians should focus on accurately evaluating congestion through an “objective bedside assessment” of the patient's hemodynamic status. This shift in approach requires moving beyond automatic reactions to laboratory values and instead asking critical questions: Is the patient clinically improving? Is there clear evidence of decongestion? Or do signs of ongoing congestion, hypoperfusion, or another renal insult persist?

LIMITATIONS OF TRADITIONAL HEMODYNAMIC ASSESSMENT

While objective hemodynamic assessment is clearly essential for guiding management in patients with cardiorenal dysfunction and fostering alignment across specialties, it is neither practical nor evidence-based to place a pulmonary artery catheter in every patient with hemodynamic disturbances. Traditionally, bedside evaluation has relied on physical examination findings such as jugular venous distension, peripheral edema, pulmonary rales, extremity temperature, capillary refill, and heart rate[11]. Although these signs are routinely used, they are limited by low sensitivity, significant interobserver variability, and a lack of reliability in detecting early or subclinical congestion. In patients with heart failure or shock, physical exam findings often lag behind the underlying hemodynamic changes, resulting in delayed or inappropriate therapeutic decisions[7,12]. Interestingly, a systematic review reported that physician estimates of cardiac output based solely on bedside examination were accurate only about 50 percent of the time-essentially no better than chance[13]. Additionally, individual signs such as skin mottling and capillary refill time correlated poorly with actual hemodynamic parameters, and even structured scoring systems have shown limited generalizability across diverse patient populations. Daily weight measurements are also prone to inconsistency due to differences in equipment, technique, and patient factors such as clothing, and they do not account for fluid redistribution in the absence of net fluid gain. Serum creatinine, often misused as a surrogate for intravascular volume, is influenced by multiple non-hemodynamic variables including muscle mass, medications, dilutional effects, baseline kidney function, and renal functional reserve. It also lags behind acute changes in kidney function. Natriuretic peptides, while diagnostically helpful, may be falsely elevated in chronic kidney disease or paradoxically low in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction and obesity[14,15]. Similarly, surrogates such as lactate and hematocrit are influenced by confounders and lack the specificity needed for individualized decision-making.

Chest radiography remains a commonly used tool for evaluating pulmonary congestion but often underestimates true fluid burden. Up to 20 percent of patients admitted with acute heart failure may have normal chest X-rays despite significant congestion. Radiographic signs such as Kerley B lines and pleural effusions typically appear later in the course of decompensation and may be absent in early stages[15]. CVP measurements also correlate poorly with true intravascular volume and do not reliably indicate organ-level congestion[16]. Obtaining CVP requires placement of a central venous catheter, limiting its routine applicability. Although blood volume analysis offers accurate measurements, it requires steady-state conditions and is not practical for routine use in acutely ill patients. Emerging biomarkers such as CA125 show promise but remain limited by lack of specificity, sensitivity to renal function, and inability to reflect dynamic changes in intravascular volume[17,18].

This persistent diagnostic gap underlies the differing assessments and often conflicting opinions among specialists, each influenced by their own specialty-specific perspectives. It underscores the critical need for bedside tools that offer real-time, physiologically meaningful insights into both forward flow and congestion in an integrated and clinically actionable way.

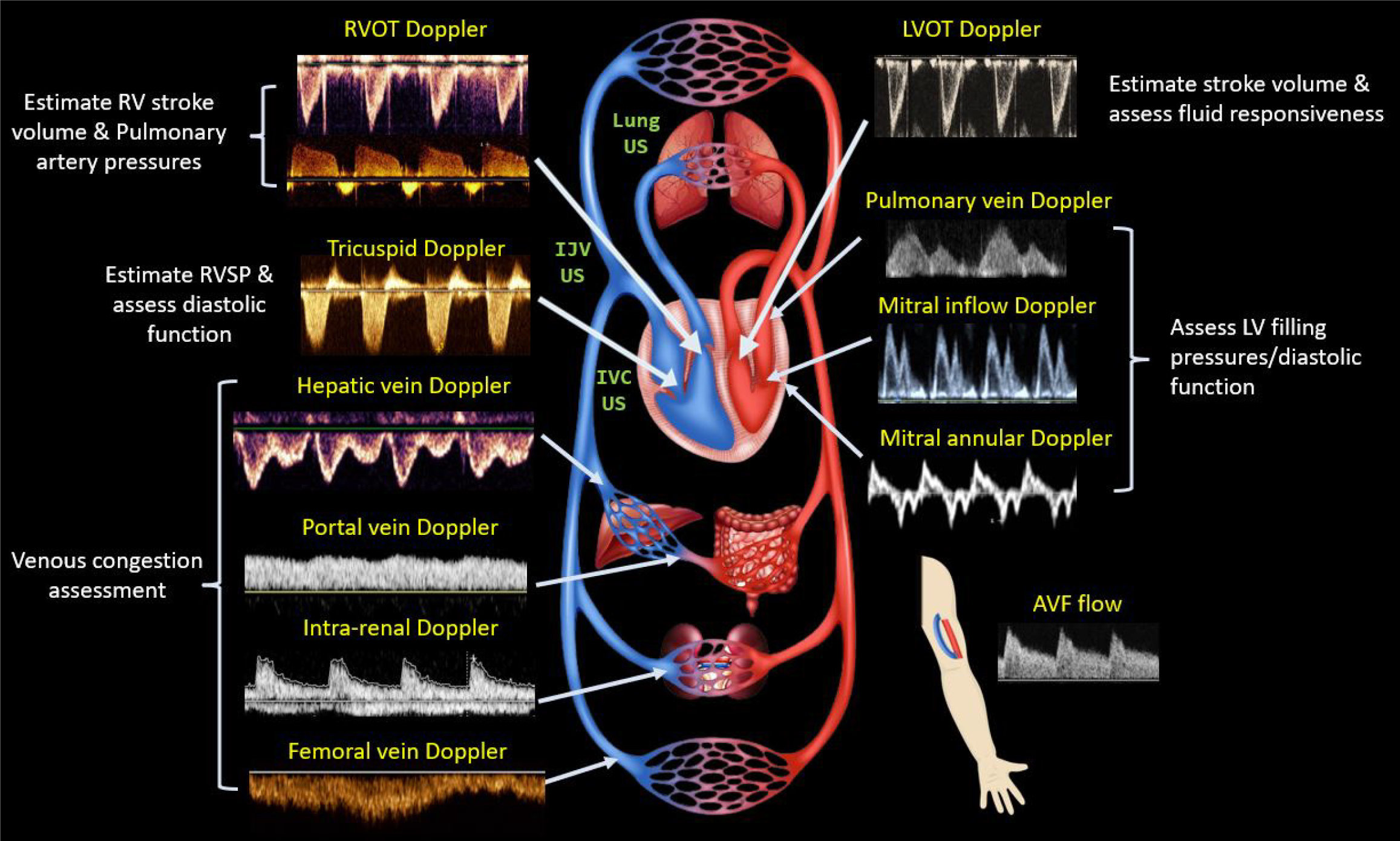

POINT-OF-CARE ULTRASOUND-GUIDED HEMODYNAMIC ASSESSMENT: TOWARD A COMMON LANGUAGE ACROSS SPECIALTIES

Point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) is a focused, clinician-performed bedside examination that serves as an adjunct to the physical exam. It brings dynamic physiology directly to the bedside and shifts the diagnostic paradigm. Rather than guessing whether a patient is underfilled, volume overloaded, obstructed, or experiencing intraabdominal hypertension from ascites, POCUS allows clinicians to visualize these conditions in real time. The “pump, pipes, and leaks” framework, previously proposed by our group, demonstrates how POCUS facilitates precise management decisions[19]. Briefly, focused cardiac ultrasound, the “pump” assesses left and right ventricular function, filling pressures, and pericardial effusion[20]. Doppler imaging of hepatic, portal, and renal parenchymal veins evaluates systemic venous congestion-the “pipes”. Lung ultrasound, which detects extravascular lung water, along with abdominal ultrasound for identifying ascites represent the “leaks”[21]. Each of these components provides a piece of the cardiorenal puzzle, allowing clinicians to evaluate the hemodynamic circuit holistically rather than relying on isolated data points[22].

Take, for example, a patient with rising serum creatinine during aggressive diuresis. Does this signify hypovolemia from overdiuresis, effective decongestion, or impaired forward flow due to worsening cardiac function? POCUS can help clarify the picture. If cardiac output remains stable, venous Doppler waveforms are improving, and lung ultrasound shows fewer B-lines (artifacts suggestive of interstitial edema), the creatinine rise may reflect hemoconcentration or changes in intraglomerular dynamics rather than true renal injury[22]. On the other hand, if venous congestion has resolved but cardiac output has fallen, continuing high-dose diuretics empirically could worsen renal perfusion and lead to clinical deterioration[10]. In such cases, POCUS becomes essential for real-time physiological assessment and for guiding individualized, safe therapy.

Each POCUS component adds unique value. For example, cardiac output estimation using left ventricular outflow tract Doppler has shown accuracy comparable to invasive thermodilution techniques[23]. Although Doppler imaging is an advanced skill, artificial intelligence may improve its reproducibility and accessibility by supporting image acquisition and waveform interpretation[24]. Doppler-based estimates of left ventricular filling pressures, such as the mitral E/e′ ratio and tricuspid regurgitation jet velocity, are useful in determining fluid tolerance and differentiating cardiogenic from pneumogenic pulmonary edema[19,25]. Pulmonary artery pressures can also be estimated using tricuspid regurgitation jet velocity, right ventricular outflow tract and pulmonary regurgitation Doppler signals. When combined with grayscale and Doppler findings, this approach may help distinguish between group I and group II pulmonary hypertension, which has important implications for treatment strategies such as optimizing diuretics vs pulmonary vasodilators and determining the need for right heart catheterization. Ultimately, it is not just the volume but also the pressure that drives congestion[26,27]. Furthermore, POCUS can measure arteriovenous fistula flow in patients with end stage kidney disease or kidney transplant recipients, where high output cardiac failure may contribute to pulmonary hypertension[28].

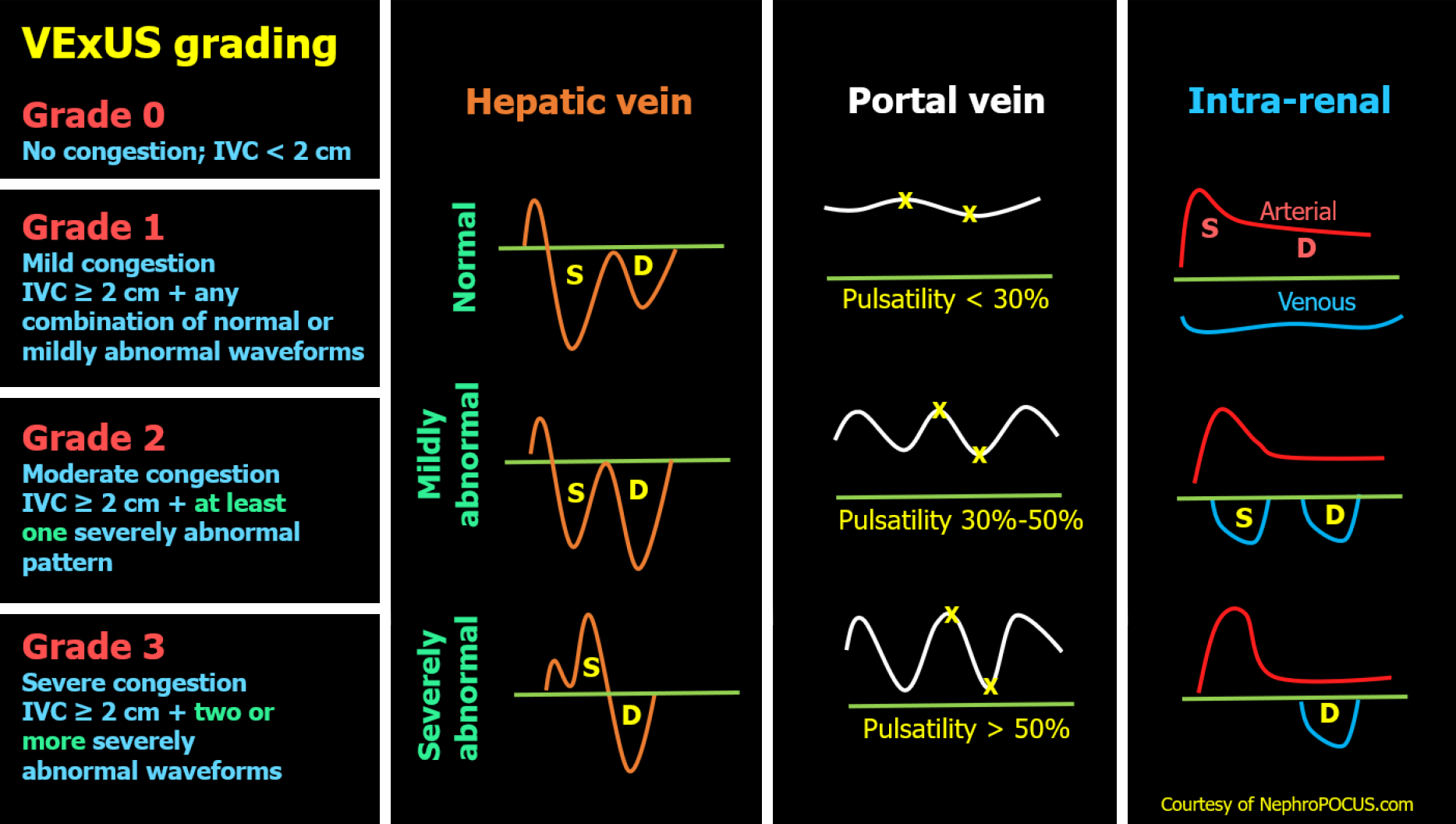

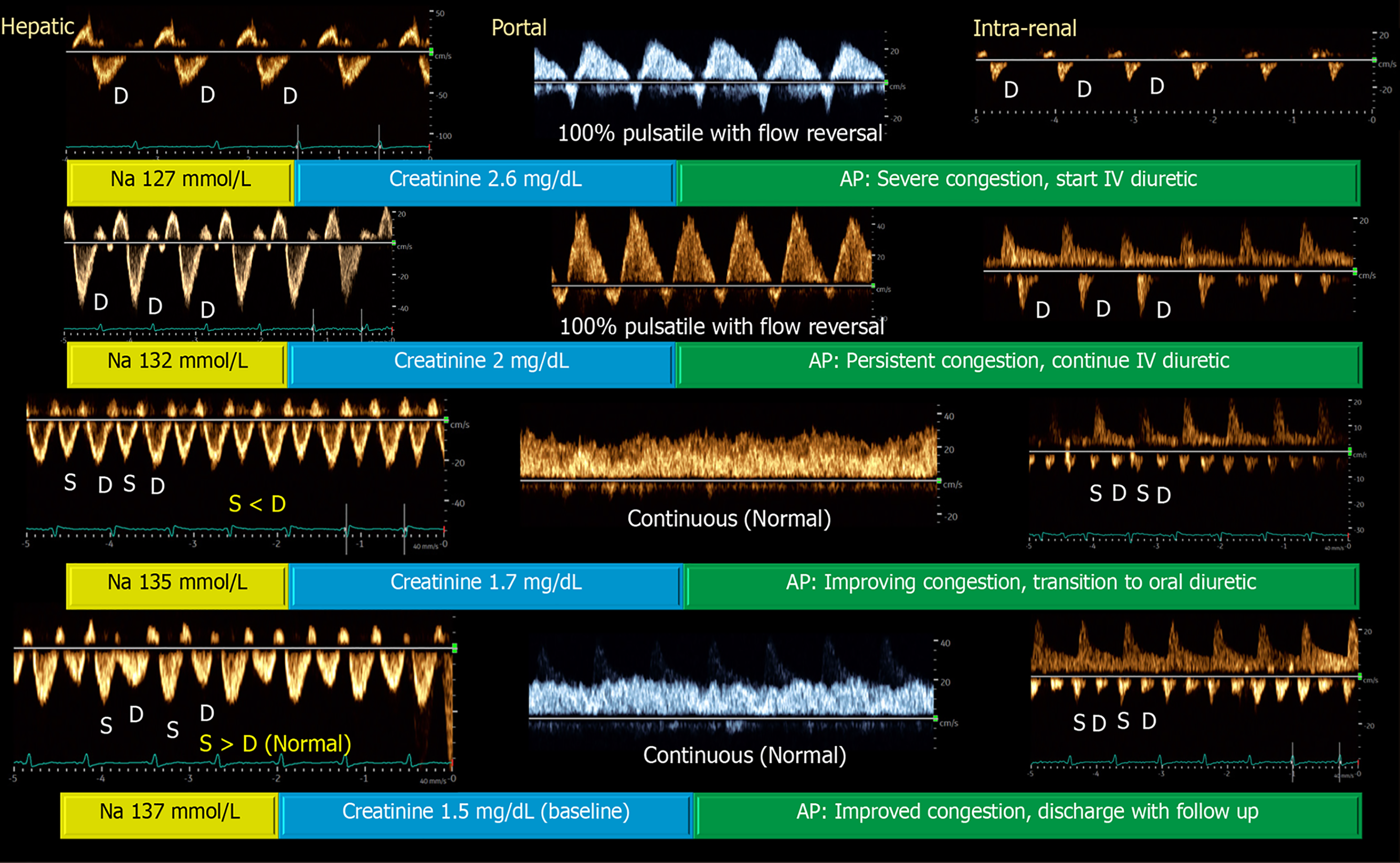

The venous system, initially a compliant reservoir, gives way to organ dysfunction when its capacitance is exhausted. At that point, small changes in volume cause large increases in venous pressure at the organ level[29,30]. Inferior vena cava (IVC) ultrasound, often favored by novice POCUS users for its perceived technical ease, is commonly used to estimate right atrial pressure or CVP. However, IVC assessment has multiple technical and interpretive limitations as discussed elsewhere[31]. The venous excess ultrasound (VExUS) grading system addresses this gap by integrating multiple venous Doppler waveforms (hepatic, portal and intrarenal) into a structured score to quantify organ level congestion[32]. Figure 1 illustrates the VExUS grading system. This allows clinicians not only to determine whether congestion is present, but also to assess whether it contributes to renal dysfunction and whether decongestive therapy is effective, since these waveforms are dynamic and responsive to treatment. Residual congestion at discharge has been shown to be more predictive of adverse outcomes than transient rises in creatinine[33]. POCUS can therefore guide therapy toward true decongestion, even when laboratory values and clinical signs are ambiguous[34]. Moreover, incorporating VExUS into traditional models improves the prediction of in-hospital mortality in patients admitted with acute decompensated heart failure[35]. Figure 2 presents an illustrative case showing parallel improvement in Doppler waveforms and laboratory values with decongestion. However, it is not yet known whether normalizing these waveforms translates into improved outcomes, a question that will require larger studies to answer.

Figure 1 Venous excess ultrasound Grading System: When the inferior vena cava diameter exceeds 2 cm, further evaluation of the hepatic, portal, and intrarenal venous Doppler waveforms is recommended.

Abnormalities in these waveforms correlate with the degree of venous congestion. Hepatic vein Doppler is classified as mildly abnormal when the S wave is smaller than the D wave but remains below the baseline, and as severely abnormal when the S wave is reversed. Portal vein Doppler is mildly abnormal with 30%-50% pulsatility and severely abnormal when pulsatility is 50% or greater. Intrarenal vein Doppler is mildly abnormal when pulsatile with distinct S and D components, and severely abnormal when monophasic with a continuous D-only pattern. This figure was adapted from NephroPOCUS.com with permission. The corresponding author, Dr. Abhilash Koratala, is the website owner and copyright holder. Available from: https://nephropocus.com/2021/10/05/vexus-flash-cards/.

Figure 2 Venous excess ultrasound waveforms illustrate a case of acute kidney injury and hyponatremia, where serial assessment of venous Doppler patterns during daily clinical exams demonstrated progressive improvement with diuretic therapy[22].

Notably, the patient had no pedal edema or visible jugular venous distention and was initially presumed to be hypovolemic. However, point-of-care ultrasound revealed elevated right atrial pressure and severe venous congestion. The patient had heart failure with reduced ejection fraction and a chronically dilated inferior vena cava (IVC), making reliance on IVC diameter alone inadequate for follow-up evaluation. Citation: Koratala A, Ronco C, Kazory A. Multi-Organ Point-Of-Care Ultrasound in Acute Kidney Injury. Blood Purif 2022; 51: 967-971. Copyright© S. Karger AG, Basel 2022. Published by S. Karger AG, Basel. The authors have obtained the permission for figure using from the Springer Nature Publishing Group (Supplementary material).

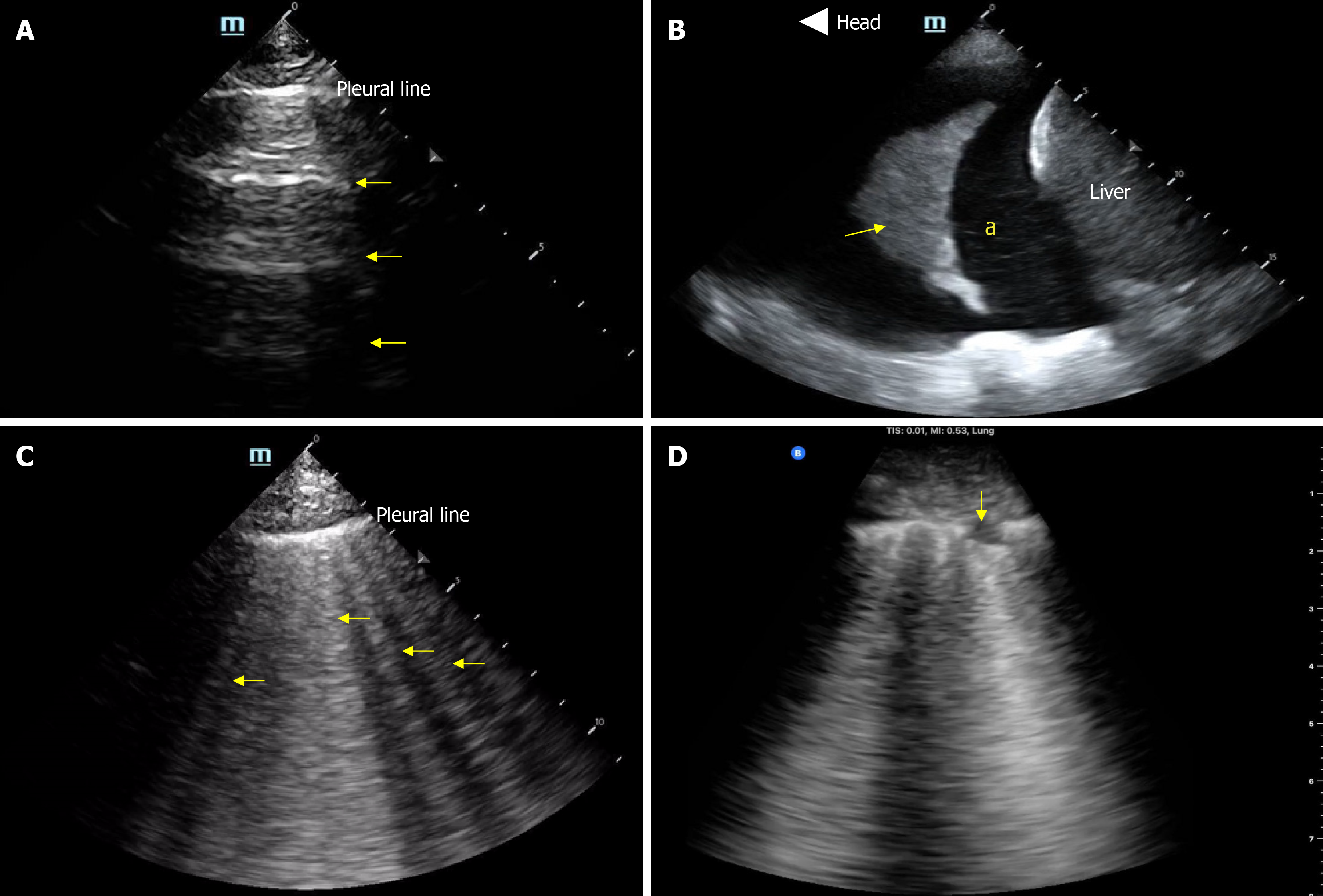

Lung ultrasound is another valuable tool for evaluating extravascular lung water. It has been shown to be more sensitive than chest radiography in detecting pulmonary congestion[36,37], and it holds prognostic value in heart failure, helping to monitor the effectiveness of decongestive therapy[38,39]. It is also technically simpler than cardiac ultrasound in terms of both image acquisition and interpretation. However, B lines, the vertical artifacts characteristic of pulmonary edema are non-specific and may also be seen in ARDS, pneumonia, pulmonary fibrosis, and alveolar hemorrhage[40]. In such cases, integration with Doppler-based assessment of left ventricular filling pressures is helpful as mentioned above. Figure 3 illustrates common pathologies identified by lung ultrasound.

Figure 3 Basic lung ultrasound findings.

A: Normal lung with horizontal hyperechoic artifacts known as A-lines; B: Pleural effusion (asterisk) appearing as an anechoic area above the liver; the arrow points to atelectatic lung; C: Vertical hyperechoic artifacts called B-lines emerging from the pleural line, indicative of interstitial thickening typically due to fluid accumulation; D: Interstitial pneumonia, characterized by confluent B-lines and an irregular pleural line, with the arrow indicating a subpleural consolidation. Citation: Diniz H, Ferreira F, Koratala A. Point-of-care ultrasonography in nephrology: Growing applications, misconceptions and future outlook. World J Nephrol 2025; 25: 14: 105374. Copyright© The Author(s) 2025. Published by Baishideng Publishing Group Inc[29].

Patients with refractory heart failure and predominant right-sided congestion often develop ascites, which contributes to renal dysfunction through increased intraabdominal pressure. POCUS helps identify ascites, which appears as an anechoic space in dependent areas below the diaphragm, and differentiates it from other causes of abdominal distension, such as abdominal wall edema or ileus. POCUS can also be used to guide diagnostic or therapeutic paracentesis and to detect bowel wall edema, a known marker of poor prognosis in acute heart failure exacerbation[19].

Figure 4 provides a visual summary of POCUS-assisted assessment of the hemodynamic circuit. Because of this objectivity and physiologic clarity, POCUS promotes agreement across specialties by offering a shared lens through which to assess and manage complex cardiorenal patients.

CONCLUSION

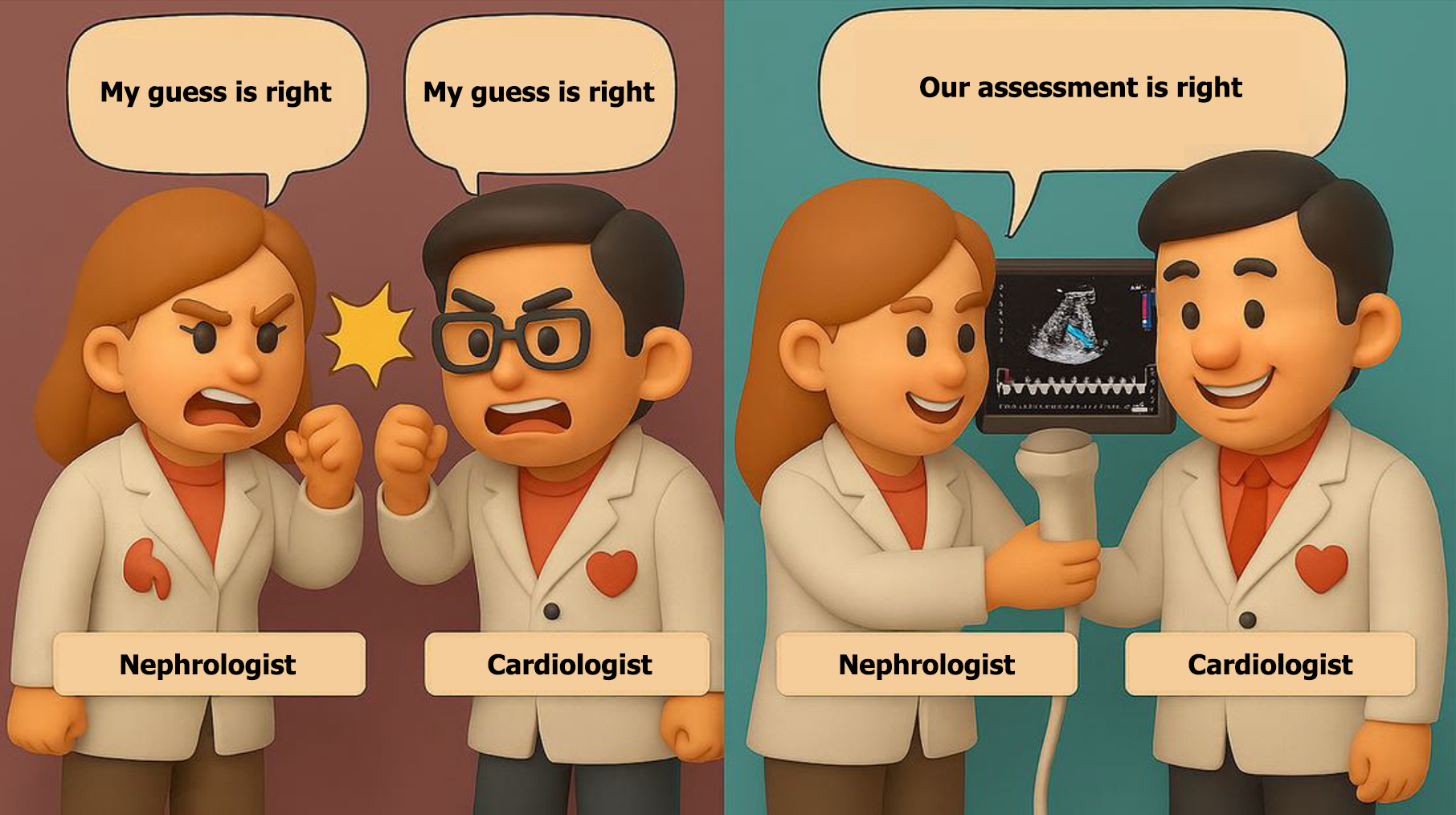

In the contemporary management of cardiorenal syndrome, POCUS is more than just a tool; it represents a mindset. It encourages clinicians to look beyond isolated data points and instead focus on dynamic physiological changes at the bedside, promoting informed, unified clinical decision-making over reliance on guesswork (Figure 5). While formal POCUS training is not yet a universal component of nephrology or cardiology fellowships, interest is rapidly growing. Traditionally, cardiologists are well-trained in interpreting echocardiograms but do not routinely perform image acquisition themselves in clinical practice. This creates a disconnect with POCUS, which requires not only interpretation but also real-time image acquisition and integration into bedside decision-making. Moreover, many cardiologists have limited exposure to lung ultrasound and Doppler-based assessments of systemic congestion, areas where nephrologists are increasingly taking the lead in both education and research. This evolving overlap in skillsets presents an important opportunity for collaboration, shared learning, and rethinking traditional boundaries in training.

Figure 5 From guesswork to shared insight.

This illustration contrasts outdated, guesswork-based decision-making with a modern, physiology-driven approach fostering collaboration and patient-centered care.

Future directions for POCUS education among physicians who care for cardiorenal patients should prioritize structured, competency-based learning that supports progressive skill development and clinical application. Training should begin with essential knowledge such as ultrasound physics, image acquisition, and machine operation, followed by targeted modules in lung ultrasound, IVC assessment, focused cardiac views, and venous Doppler. Clinical integration should be emphasized throughout, with supervised scanning, case-based teaching, and real-time interpretation forming the foundation of hands-on learning.

Institutional investment in faculty development, simulation resources, and mid- to high-end ultrasound equipment is essential. Tools such as cloud-based image review platforms and AI-guided image quality feedback can help ensure consistent training even in settings with limited expert availability. Cost-sharing between departments and remote mentorship models may further support implementation, particularly in resource-constrained environments.

Certification or milestone-based assessments, whether through internal programs or professional society-endorsed frameworks, should be used to validate competency. Importantly, POCUS should not be treated as an optional skill, but as a core clinical tool embedded into daily nephrology and cardiology practice. With growing evidence linking sonographic markers of congestion to outcomes in heart failure, hepatorenal dysfunction, and hepatocardiorenal syndrome, the clinical importance of multi-organ POCUS is increasingly clear. Ongoing clinical trials, such as NCT06887179, are evaluating its impact on outcomes in patients with heart failure in the ambulatory setting as well. Equipping nephrologists and cardiologists alike with the skills to assess and act on these findings will be key to advancing bedside care in the years to come.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Cardiac and cardiovascular systems

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report’s classification

Scientific Quality: Grade A, Grade C

Novelty: Grade B, Grade B

Creativity or Innovation: Grade B, Grade C

Scientific Significance: Grade B, Grade C

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P-Reviewer: Al Zo'ubi MA, MD, Consultant, Researcher, Jordan; Elbarbary MA, Assistant Professor, Consultant, Egypt S-Editor: Qu XL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhao S