Published online Dec 26, 2025. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v17.i12.112046

Revised: August 18, 2025

Accepted: November 4, 2025

Published online: December 26, 2025

Processing time: 161 Days and 16.3 Hours

The use of apixaban in chronic hemodialysis (HD) patients for non-valvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF) is still controversial regarding benefit of stroke protection vs risk of bleeding. Rotational thromboelastometry (ROTEM) is a point of care method that evaluates clot formation in whole blood and has been used as an evaluation tool for bleeding risk assessment in non-HD apixaban users.

To determine whether bleeding risk can be predicted using ROTEM activated with tissue factor (EXTEM) in HD patients receiving apixaban for NVAF.

Nineteen HD patients with NVAF treated with apixaban for at least 8 days were enrolled. Four dosing regimens were recorded as prescribed by their physician, from 2.5 mg once daily on a non-dialysis day to 5 mg twice daily. Standard coagulation tests, along with ROTEM and apixaban drug levels (using liquid anti-Xa assay) were performed once on a non-dialysis day before and two hours after apixaban morning pill administration. Patients were subsequently monitored for thrombotic/bleeding events and all-cause mortality.

Over a median follow-up period of 36 months, six patients experienced a bleeding event (group A) and 13 remained free of bleeding (group B). Six deaths were recorded: Three due to major bleeding, one from thrombotic stroke, and two unrelated to coagulopathy. EXTEM clotting time (CT)-post was the only parameter that significantly differed between group A and group B (P = 0.013). Each 1-second increase in CT-post was linked to an 8% higher likelihood of a bleeding event (odds ratio = 1.08, 95% confidence interval: 1.0-1.17; P = 0.048). A significant progressive increase was observed with the drug’s trough and peak levels (P < 0.05) across the four dosing regimens but no significant relationship was found between CT and apixaban dose groups.

Early detection of bleeding risk in HD patients with NVAF on Apixaban maybe be effectively achieved through frequent monitoring using ROTEM EXTEM post CT, thereby helping to reduce associated morbidity.

Core Tip: The clinical dilemma of anticoagulation choice in hemodialysis patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation is still unresolved. Apixaban use yields so far conflicting results. We conducted a pilot study in hemodialysis patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation on apixaban, where we measured once on a non-dialysis day drug levels and rotational thromboelastometry before and after the morning pill under the dosing regimen used in clinical practice. Then we registered bleeding and thrombotic events. We found that clotting time by rotational thromboelastometry EXTEM after the morning pill was associated with bleeding events and thus could potentially be used as a prediction tool.

- Citation: Bacharaki D, Kyriakou E, Sardeli A, Nikolopoulos P, Triantaphyllis G, Drakou A, Makris F, Spanou E, Triantou E, Haviaras E, Fatourou A, Poulis A, Tsantes A, Kyriazis J, Lionaki S. Bleeding prediction by rotational thromboelastometry in chronic hemodialysis patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation on apixaban. World J Cardiol 2025; 17(12): 112046

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v17/i12/112046.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v17.i12.112046

Non-valvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF) is highly prevalent among patients undergoing maintenance hemodialysis (HD), with an estimated incidence of 11%, and is associated with increased all-cause mortality and ischemic stroke[1]. While anticoagulation guidelines, including indications, medications, and dosing, are well established for the general popu

Direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) have emerged as a potential alternative, as they have demonstrated efficacy comparable to warfarin while posing a lower bleeding risk in the general population[2]. However, their use is restricted in patients with an estimated glomerular filtration rate < 15 mL/minute/1.73 m2, as all DOACs undergo some degree of renal elimination[11]. Among them, apixaban, which has the lowest renal clearance, has been approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration for NVAF in HD patients[12]. This approval was based on a pharmacokinetic study of eight HD patients, recommending the same dosing as for the general population - 5 mg twice daily - with a reduced dose of 2.5 mg twice daily for patients meeting at least two of the following criteria: (1) Age ≥ 80 years; (2) Body weight ≤ 60 kg, and (3) Serum creatinine ≥ 1.5 mg/dL[13].

However, clinical experience with apixaban in HD patients in the United States has yielded mixed results. A pharmacokinetic study by Mavrakanas et al[14], involving seven HD patients, concluded that a 5 mg twice daily dose led to supratherapeutic drug levels and should be avoided. Conversely, a large retrospective observational study by Siontis et al[15] comparing warfarin and apixaban in HD patients with NVAF found that only the 5 mg twice daily dose was associated with reduced all-cause mortality and thromboembolic events, while both dosing regimens were linked to a lower bleeding risk compared to warfarin. Additionally, two randomized controlled trials - RENAL-AF and AXADIA-AFNET - comparing warfarin and apixaban in HD patients yielded inconclusive results[16,17]. Notably, in the RENAL-AF trial, hemorrhagic events were ten times more frequent than thrombotic events[16]. Furthermore, assessment of the coagulation status by measuring apixaban drug levels is neither feasible in clinical practice, nor has been proven associated with hemorrhagic/thrombotic events[12,16].

Rotational thromboelastometry (ROTEM) is a point of care diagnostic tool to assess coagulation status and guide treatment algorithms in high-risk patients, particularly in surgical and trauma settings[18]. ROTEM activated with tissue factor (EXTEM) is a viscoelastic test that evaluates the extrinsic coagulation pathway. It has been proposed as a useful tool for assessing the anticoagulant effect of DOACs in emergency situations, where standard coagulation tests [like prothrombin time (PT)/international normalized ratio, and activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT)] are often inadequate and chromogenic anti-Xa assays are cumbersome and not always available in clinical practice[19]. EXTEM clotting time (CT) has been shown to correlate with DOAC levels, making it a practical alternative[20]. Oral antiplatelet drugs (e.g., aspirin, clopidogrel) can also affect ROTEM EXTEM, but their impact is not fully captured by this test[21]. Additionally, the best method to evaluate antiplatelet activity in emergencies is the point-of-care Platelet Function Analyzer (PFA)-200[22].

In the present study we aimed to assess bleeding and thrombotic risk using ROTEM-EXTEM and PFA-200 in HD patients with NVAF receiving apixaban, with or without concomitant antiplatelet therapy.

This is a pilot cohort observational prospective study including chronic HD patients with NVAF on apixaban from four private HD units in Attica, Greece. All laboratory analysis was conducted in a single Attikon University General Hospital in Athens, Greece, in which the private HD units are affiliated. The study was performed in strict accordance with the ethical guidelines of the Helsinki Declaration and was approved by the Ethical Scientific Committee of Attikon University General Hospital Institutional Review Board (Approval No. 50/01-02-2021).

Nineteen HD patients were recruited between February 25, 2021 and May 1, 2021. After acquisition of informed consent, blood samples were collected by a peripheral vein after light bandage application in the Attikon University General Hospital on the morning of a mid-week, non-dialysis day: One sample was taken prior to apixaban morning pill administration (pre), and another was collected two hours after administration (post). In both blood samples conventional coagulation tests including PT, aPTT, fibrinogen, D-dimers, were performed. Additionally in both samples, apixaban levels (trough and peak respectively) and ROTEM with EXTEM reagent were measured. Routine biochemistry and PFA-200 tests were undertaken only on the pre-sample.

Enrolled HD patients were on standard 4 hours, 3 times weekly dialysis program, using bicarbonate dialysate. Unfractionated or low molecular weight heparin were used during the dialysis session according to the nephrology unit protocol. A thorough review of each patient’s medical chart was performed by the attending physician to collect data on demographic and clinical characteristics, including coronary artery disease, stroke, diabetes, arterial hypertension, history of thrombotic or bleeding events. Additionally, the review included an analysis of the prescribed apixaban regimen, antihypertensive medications, lipid lowering agents (statins), anti-arrhythmic and antiplatelet agents (salicylic acid/clopidogrel). Enrolled patients were also assessed using the Frailty Scale and the Charlson Comorbidity Index[23,24]. The clinical prediction tools CHA2DS2-VASc, HAS-BLED, simplified ATRIA bleeding risk score, Modified HD score was estimated for all participants[8,9].

Participants were eligible for inclusion if they had been on dialysis for at least three months, were 18 years or older, and had NVAF for which they had been receiving Apixaban for at least eight days, ensuring a presumed steady-state of the drug[13,14]. The patients were prescribed anticoagulation therapy, i.e., apixaban by their attending physician based on the traditional CHA2DS2-VASc score for patient selection. Exclusion criteria included active malignancy or acute infection at the time of blood sampling, active autoimmune disease, anticipated major surgery, a life expectancy of less than one-year, severe liver disease, or any known inherited or acquired bleeding disorder, including thrombocytopenia.

Ten patients were prescribed the recommended apixaban dose according to age and/or body weight[12], while the remaining patients received a dosage based on their physician’s clinical judgment, considering stroke/bleeding risk assessment tools. Patients were divided into four groups based on their dosing regimen: Two patients received 2.5 mg once daily on non-dialysis days (group 1), four patients received 2.5 mg once daily (group 2), ten patients received 2.5 mg twice daily (group 3), and three patients received 5 mg twice daily (group 4). Apixaban trough and peak levels corresponded to pre-dose and post-dose samples collected around the morning apixaban administration, respectively. The difference between these levels was defined as apixaban difference.

Laboratory analyses were conducted in the laboratory department of the Attikon University General Hospital by experienced personnel. The apixaban dose regimen was kept constant throughout the study or changed based on the attending physician’s judgement, in which case the reason to change and the new regimen were recorded.

Follow-up began on the date of enrolment and finished upon the death of patients or on May 1, 2024, whichever came first. Follow-up data were retrieved from clinical records by the attending nephrologists. Thrombotic and bleeding events, both major and minor, as previously defined, were the primary outcomes analyzed[25]. Death from all causes was also recorded.

Conventional coagulation tests: The aPTT, PT, fibrinogen, and D-dimers were all measured on BCS XP system hemostasis analyzer (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, Marburg, Germany). Pathromtin* SL (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, Marburg, Germany) was used to determine aPTT and the Thromborel S reagent (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, Marburg, Germany) was used for PT determination. Plasma concentrations of fibrinogen were measured using a modification of the Clauss method with the Fibrinogen Multifibren* U reagent (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, Marburg, Germany). D-dimers were assessed by the Innovance D-dimer assay (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, Marburg, Germany), a particle-enhanced immunoturbidimetric method. Blood samples for analysis were anticoagulated with 0.109 mol/L trisodium citrate (9:1, vol/vol blood anticoagulant) and immediately centrifuged at 2500 g for 20 minutes.

ROTEM with EXTEM reagent: For this test, whole blood was collected in 3.8% trisodium citrate, then recalcified and analysed on the ROTEM analyser (Tem Innovations GmbH, München, Germany) using the EXTEM assay, that is activated with tissue factor. The following EXTEM variables were measured: CT (second): Time from start of the measurement until initiation of clotting (initiation of clotting, thrombin formation, start of clot polymerization); clot formation time (second): Time from initiation of clotting until a clot firmness of 20 mm is detected (fibrin polymerization, stabilization of the clot with thrombocytes and FXIII); α-angle of clot polymerization rate; maximum clot firmness (MCF) (mm): Firmness of the clot (increasing stabilization of the clot by the polymerized fibrin, thrombocytes as well as FXIII); maximum clot lysis (ML; %): Reduction of clot firmness after MCF in relation to MCF [stability of the clot (ML < 15%) or fibrinolysis (ML > 15% within 1 hour)]; lysis index 60 minutes after CT (%); percentage of the remaining clot stability in relation to the MCF following the 60-minute observation period after CT and indicates the speed of fibrinolysis.

PFA-200: The PFA-200 was used to detect platelet function in HD patients under apixaban, as described[26]. The PFA-200 (Dade Behring, Marburg, Germany) measures the ability of platelets, activated in a high-shear environment, to occlude an aperture in a membrane treated with collagen and epinephrine or in collagen and adenosine diphosphate. The time taken for flow across the membrane to stop (closure time, CT) is recorded. For this test, whole blood collected in 3.8% trisodium citrate and 0.8 mL of the mixed whole blood was pipetted into the sample reservoir of 1 collagen and epinephrine cartridge and 1 collagen and adenosine diphosphate cartridge (pre warmed to room temperature) and then loaded into the PFA-200 analyzer. The references ranges were < 160 seconds for collagen and epinephrine and < 120 seconds for collagen and adenosine diphosphate, as mentioned in the manufacturer’s reagent instruction booklet.

Liquid anti-Xa assay: The liquid anti-Xa assay is an automated chromogenic assay being used for measuring direct factor X (FXa) inhibitor concentrations in human citrated plasma. FXa is neutralized directly by apixaban. Residual FXa is quantified with a synthetic chromogenic substrate. The paranitroaniline released is monitored kinetically at 405 nm and is inversely proportional to the apixaban levels in the sample. Apixaban levels in patient plasma were measured automatically on instrumentation laboratory coagulation systems (ACL TOP) when this assay was calibrated with the HemosIL apixaban calibrators[27].

All statistical analyses were conducted using the SPSS/PC 22 statistical package (IBM, IL, United States). Patients were classified into two groups: Those who experienced a major or minor bleeding event (bleeding group) and those who did not (no bleeding group). Normally distributed variables were expressed as the mean ± SD, while non-normally distributed variables were expressed as the median (interquartile range). Differences in baseline characteristics between the groups were tested using the χ2 test and the Kruskall-Wallis test as appropriate. One-way Anova was conducted to examine variables across drug dose regimens (groups), as described in methods. Finally, to identify bleeding risk factors, we performed a multivariable logistic regression analysis with CT-post as the primary predictor. Candidate variables for adjustment were selected based on clinical relevance and their strong correlation with CT-post rather than their univariate association with bleeding. These included apixaban peak level and PFA closure time, both of which showed high correlation with CT-post in preliminary analyses. A forward stepwise selection procedure was applied with entry and retention thresholds set at P < 0.05, and model fit was evaluated at each step using the Akaike information criterion. No other clinical or laboratory variable demonstrated a significant univariate association with bleeding in the HD cohort, including apixaban peak level and PFA closure time themselves. Statistical significance was set at the level of P < 0.05 (two-sided).

Twenty-five patients were assessed for eligibility, of whom 23 met the inclusion criteria. Two were excluded - one due to an anticipated major surgery and the other due to active autoimmune disease. Ultimately, 19 patients were enrolled in the study, as four declined to provide informed consent.

Thus, the study cohort consisted of 19 HD patients (13 men and 6 women) with a mean age of 73 ± 12 years, as shown in Table 1. Diabetes, arterial hypertension, coronary artery disease, stroke and previous bleeding episodes were detected in 36.8%, 80%, 26.3%, 21.1% and 26.3% of patients, respectively. Antiplatelet drugs were prescribed to 21.1% of patients, antiarrhythmics to 26.3%, statins to 52.6% and antihypertensives: Β-blockers to 42.1 and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers to 42.1.

| Characteristic clinical and epidemiologic | All patients (N = 19) | No Bleeding (n = 13) | Bleeding (n = 6) | P value |

| Age (year) | 73 ± 12 | 73 ±12 | 74 ± 6 | 0.827 |

| Sex (male = 1/females = 2) | 13/6 | 9/4 | 4/2 | 0.911 |

| Dialysis vintage (months) | 4.56 ± 3.5 | 4.83 ± 0.9 | 4.0 ± 2.4 | 0.633 |

| Body weight (kg) | 83 ± 20 | 85 ± 20. | 79 ± 21 | 0.513 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 7 (36.8) | 5 (38.5) | 2 (26.8) | 0.829 |

| Hypertension | 12 (80) | 9 (81.8) | 3 (75) | 0.770 |

| Cardiac artery disease | 5 (26.3) | 4 (30.8) | 1 (5.2) | 0.516 |

| Previous bleeding episodes | 5 (26.3) | 4 (30.8) | 1 (5.2) | 0.516 |

| Stroke | 4 (21.1) | 2 (15.4) | 2 (33.3) | 0.372 |

| Frailty scale | 3.8 ± 1.8 | 3.8 ± 2.0 | 3.8 ± 1.5 | 0.944 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | 5.2 ± 1.3 | 5.2 ± 1.4 | 5.2 ± 1.0 | 0.933 |

| Stroke/bleeding risk assessment (score) | ||||

| CHA2DS2-VASc score | 3 (2-5) | 3 (2-5) | 3 (2-4) | 0.532 |

| HAS-BLED score | 3 (2-3) | 2 (1.5-3) | 3.5 (2.7-5.5) | 0.070 |

| ATRIA risk score | 6 (5-8) | 6 (3-7) | 5.5 (5-8.5) | 0.723 |

| Modified hemodialysis score | 1 (0-2) | 1 (0-2) | 1 (0.75-2) | 0.550 |

| Drugs | ||||

| ACEIs/ARBs | 8 (42.1) | 7 (53.8) | 1(5.2) | 0.127 |

| β-blockers | 8 (42.1) | 6 (46.2) | 2 (33.3) | 0.599 |

| Antiarrhythmics | 5 (26.3) | 5 (38.5) | 0 (0) | 0.077 |

| Statins | 10 (52.6) | 7 (53.8) | 3 (30) | 0.876 |

| Acetylasalicylic acid/clopidogel | 4 (21.1) | 4 (30.8) | 0 (0) | 0.126 |

During a median follow-up period of 36 months’ six patients (31.4%) experienced a bleeding event (3 major and 3 minor; group A), while 13 patients (68.4%) did not (group B). Table 1 summarizes the general characteristics of the two groups, which showed no significant differences in age, sex, weight, dialysis duration, comorbidities, stroke/bleeding risk assessment scores, or the use of specific medication classes. Of the six deaths recorded during the follow-up period, three were attributed to major bleeding events, one to a thrombotic stroke, and two were unrelated to coagulopathy, one due to septic shock and the other to sudden death. All patients maintained their prescribed apixaban dose throughout the follow-up period, with the exception of one case. This patient experienced minor bleeding (epistaxis) while on apixaban 2.5 mg twice daily, prompting the attending physician to adjust the regimen to 2.5 mg once daily. On the day of examination, this patient exhibited (190 ng/mL) and peak (330 ng/mL) apixaban levels above the reference range, along with elevated CTs both before (104 seconds) and after (156 seconds) dosing. No further bleeding or thrombotic events were observed in this patient for the remainder of the study.

The Table 2 presents the laboratory findings collected before and after the administration of the morning apixaban dose, categorized into two groups: Patients with bleeding events (group A) and those without (group B). The results include standard coagulation tests, ROTEM parameters, apixaban trough and peak levels, and PFA-200 results (pre-dose sample only). The EXTEM CT-post differed significantly between group A and group B (P = 0.008). Additionally, difference between EXTEM CT-post and pre measurements between group A and group B were statistically significant (P = 0.013). All other parameters showed no significant differences between the two groups, including apixaban peak and trough levels as well as difference between peak and trough levels of apixaban.

| Conventional coagulation tests (pre/post apixaban) | All patients (N = 19) | No Bleeding (n = 13) | Bleeding (n = 6) | P value |

| Prothrombin time-pre (second) | 11.7 (11.3-12.8) | 11.4 (11.1-12.1) | 12.7 (11.7-13.8) | 0.143 |

| aPTT-pre (second) | 34 (31-38) | 34 (28-39) | 32 (35-37) | 0.597 |

| Fibrinogen-pre (mg/dL) | 440 (388-512) | 440 (383-503) | 467 (415-516) | 0.394 |

| D-dimers-pre (ng/mL) | 633 (355-1423) | 416 (307-1496) | 713 (618-1504) | 0.765 |

| Prothrombin time-post (second) | 12 (12-13) | 11.5 (12-13) | 13 (11.5-14) | 0.636 |

| aPTT-post (second) | 34 (28-38) | 34 (28-39) | 35 (30-39) | 0.535 |

| Fibrinogen-post(mg/dL) | 443 (359-528) | 440 (355-518) | 489 (340-536) | 0.442 |

| D-dimers-post (ng/mL) | 585 (375-1418) | 491 (217-1494) | 699 (576-1404) | 0.890 |

| RΟΤΕΜ (pre/post apixaban) | ||||

| Clotting time-pre (second) | 83 (71-95) | 85 (71-93) | 80 (68-113) | 0.372 |

| Clot formation time-pre (second) | 57 (51-68) | 57 (53-66) | 59 (47-82) | 0.750 |

| An angle-pre (rad) | 78 (75-79) | 79 (77-80) | 78 (74-81) | 0.992 |

| Max clot firmness-pre (mm) | 71 (66-73) | 69 (66-73) | 72 (65-74) | 0.693 |

| Maximum clot lysis-pre (%) | 7 (6-8) | 6 (4-7) | 6 (5-7) | 0.992 |

| Li60-pre (%) | 96 (94-97) | 95 (94-97) | 97 (93-98) | 0.904 |

| Clotting time-post (second) | 102 (81-116) | 87 (77-107) | 118 (100-144) | 0.008a |

| Clot formation time-post (second) | 66 (52-76) | 66 (50-76) | 68 (54-77) | 0.692 |

| An angle-post (rad) | 77 (75-77) | 77 (75-80) | 77 (76-79) | 0.961 |

| Max clot firmness-post (mm) | 69 (66-73) | 69 (67-73) | 71 (65-75) | 0.865 |

| Maximum clot lysis-post (%) | 6 (4-7) | 7 (6-10) | 7 (5-10) | 0.975 |

| Li60-post (%) | 95 (93-97) | 94 (93-97) | 96 (93-98) | 0.719 |

| CTdiff | 8 (2-28) | 7 (1.5-19) | 38 (3-52) | 0.013 |

| PFA-200 (epinephrine) | ||||

| Closure time (second) | 135 (106-214) | 123 (113-187) | 172 (99-272) | 0.425 |

| Apixaban levels | ||||

| Apixaban-trough (ng/mL) | 93 (26-166) | 93 (53-151) | 65 (0-214) | 0.918 |

| Apixaban-peak (ng/mL) | 163 (107-234) | 183 (103-230) | 139 (86-331) | 0.841 |

| Apxdiff | 53 (27-107) | 53 (35-100) | 76 (21-137) | 0.555 |

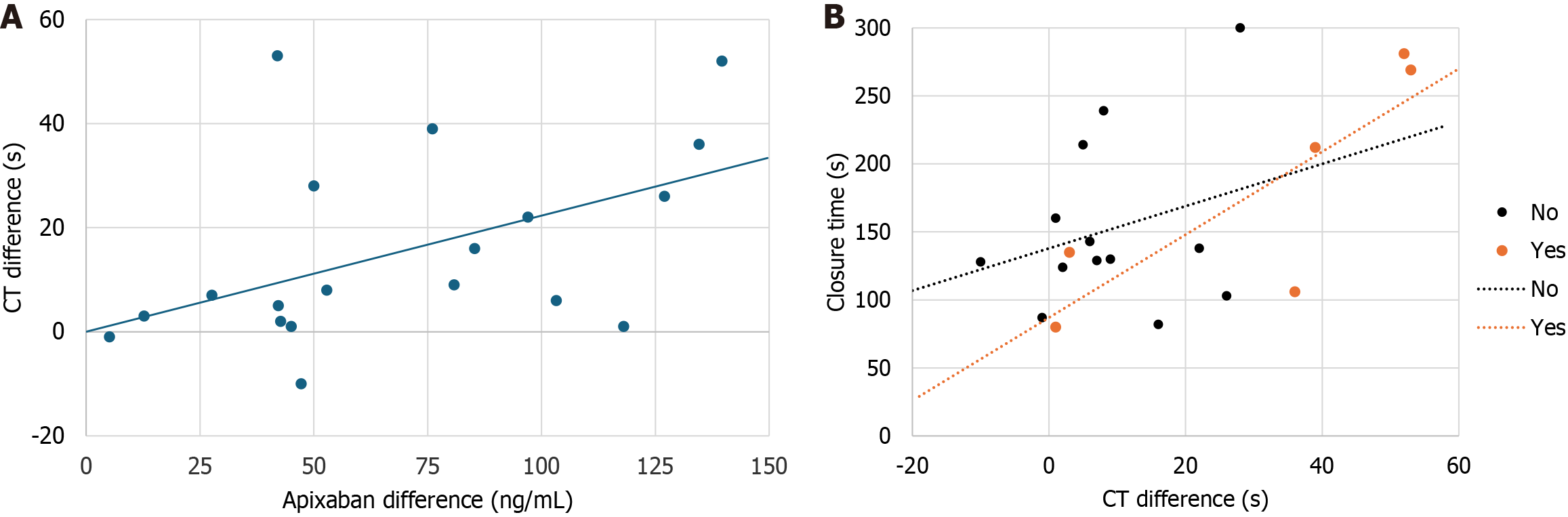

As shown in Table 3, CT-pre correlated statistically significant with CT-post, apixaban trough and peak levels. CT-post correlated statistically significant with CT-pre and apixaban peak levels. More importantly, CT diff was correlated with difference between peak and trough levels of apixaban (Figure 1A). Also, a statistically significant association was observed between PFA-200 assay and difference between EXTEM CT after and prior administration of apixaban (r = 0.565; P < 0.05). Notably, when the data were analyzed separately for patients with and without bleeding, the correlation between difference between EXTEM CT-post and pre measurements and the PFA-200 assay became even stronger (r = 0.828; P < 0.001) in the bleeding group (Figure 1B).

The previously non-significant correlation between PFA-200 and CT-post (r = 0.231) became statistically significant (r = 0.502, P = 0.034) after adjusting for peak apixaban levels. Thus, both the PFA-200 assay and apixaban peak levels were included as independent variables in a forward stepwise regression model, with EXTEM CT serving as the dependent variable. The results of this analysis (Table 4) showed that both apixaban peak levels (β = 0.18, P = 0.004) and closure time (PFA-200; β = 0.14, P = 0.038) were independently associated with CT-post. Apixaban-peak levels and closure time explained 23% and 15% of CT variability, respectively whereas both these variables explained 38% of it.

| Parameter | β | SD | Standard β | P value | R change |

| Constant | 46.57 | 16.34 | |||

| Apixaban-peak | 0.18 | 0.05 | 0.66 | 0.004 | 0.23 |

| PFA-200 (closure time) | 0.14 | 0.06 | 0.44 | 0.038 | 0.38 |

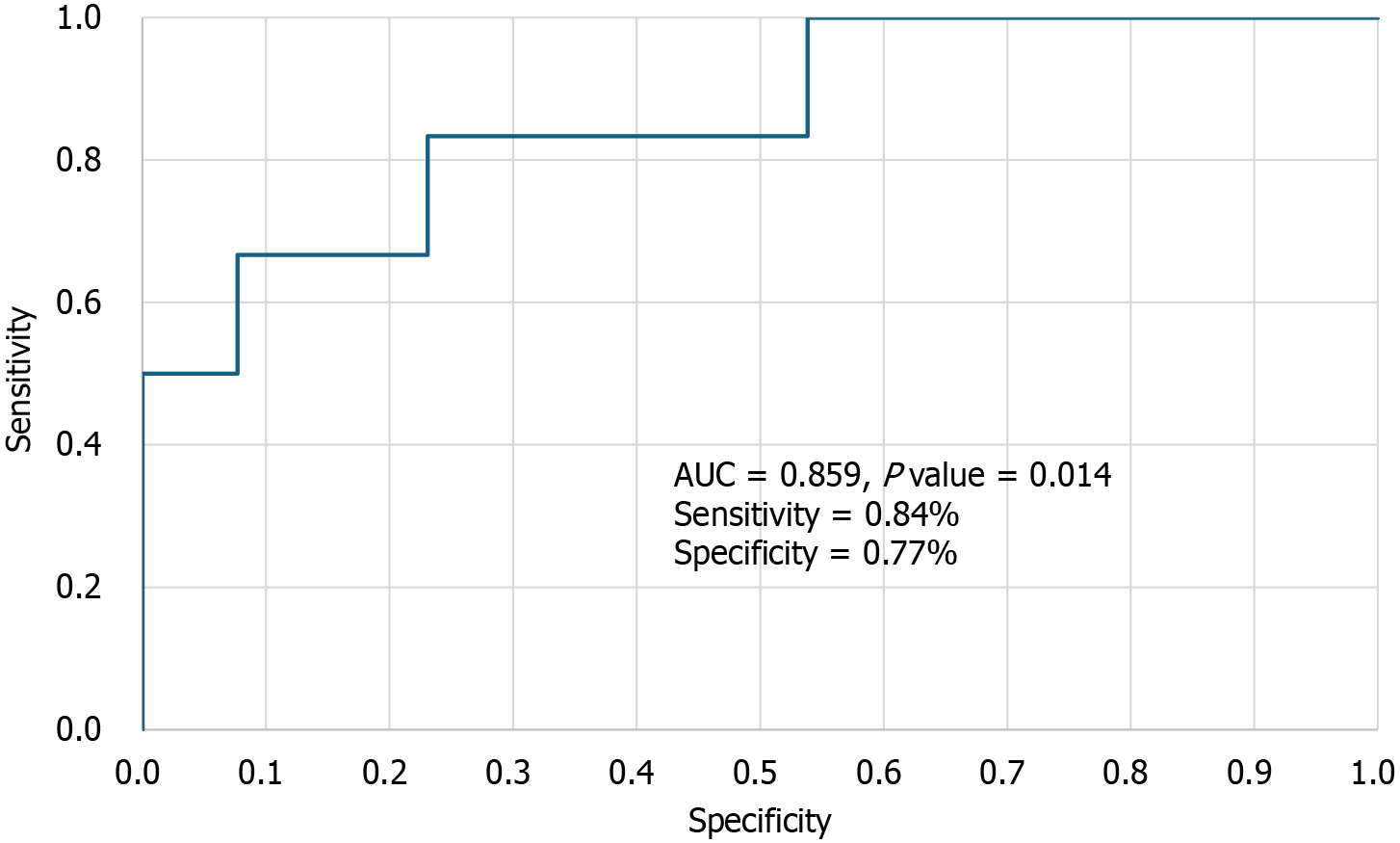

A multivariate (forward stepwise) logistic regression model (Table 5) was used to identify bleeding risk factors in our cohort. In the unadjusted Cox regression analysis of HD patients, each 1-second increase in CT-post was associated with an 8% higher likelihood of a bleeding event [odds ratio (OR) = 1.08, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.00-1.17; P = 0.048)]. This association remained unchanged even after adjusting for apixaban peak levels and PFA closure time, both of which were strongly correlated with CT-post. EXTEM CT-post demonstrated high discriminatory power in distinguishing between patients with and without bleeding events, with an area under the curve of 0.859 (95%CI: 0.673-1.000). A CT-post cutoff value of 103.5 seconds was identified as optimal, providing a sensitivity of 84% and a specificity of 77% for predicting bleeding events (Figure 2). Interestingly, bleeding risk was also strongly dependent on difference between EXTEM CT-post and pre measurements, as for each 1-second increase in difference between EXTEM CT-post and pre measurements was linked to an 11% greater probability of a bleeding event (OR = 1.11, 95%CI: 1.03-1.19; P = 0.005).

| Parameter | Univariate | Multivariable | ||

| OR (95%CI) | P value | OR (95%CI) | P value | |

| CT-post (up 1 second)1 | 1.08 (1.0-0.17) | 0.048 | 1.08 (1.0-0.17) | 0.48 |

| Apixaban-peak (up 1 ng/mL) | 1.0 (0.99-1.01) | 0.867 | ||

| PFA (closure time) (up 1 second) | 1.01 (0.99-1.02) | 0.430 | ||

The one-way ANOVA analysis (Figure 3A and Table 6) revealed a statistically significant progressive increase in both the drug’s trough levels (P = 0.016 for the trend) and peak levels (P = 0.048 for the trend) across the four drug dose regimens. This finding suggests that higher drug doses are associated with higher apixaban levels, reflecting a dose-dependent effect on anticoagulation. However, the ANOVA analysis (Figure 3B and Table 6) indicated no significant relationship between CT-post and apixaban dose groups, suggesting the absence of a dose-dependent anticoagulation effect. Notably, two out of the three patients who died from fatal bleeding had the lowest drug dose and apixaban levels, along with the highest CT-post values.

As illustrated in Figure 3C, both patients receiving the lowest apixaban dose experienced a bleeding event, while none of the three patients on the highest dose encountered such an episode. One patient in group 1, receiving 2.5 mg of apixaban once daily on non-dialysis days as a steady-state regimen, had trough (5.20 ng/mL) and peak (86 ng/mL) drug levels below the reference range, along with normal PFA-200 results (130 seconds), despite being on clopidogrel. This patient experienced a fatal thrombotic stroke.

This study found that among the various ROTEM (EXTEM) assay parameters, only the EXTEM CT-post (measured two hours after the morning apixaban dose at peak drug levels) could distinguish between the bleeding and non-bleeding groups. Specifically, each 1-second increase in EXTEM CT-post was associated with an 8% higher likelihood of a bleeding event (OR = 1.08, 95%CI: 1.0-1.17; P = 0.048). The strong predictive performance of EXTEM CT-post in distinguishing bleeding from non-bleeding events, demonstrated by an area under the curve of 0.853, a cutoff of 103 seconds, 83% sensitivity, and 77% specificity, highlights its potential as an effective tool for the early detection of imminent bleeding in HD patients. Actually, only one patient who experienced bleeding had a post-EXTEM CT value of less than 103 seconds.

EXTEM CT-post also correlated with peak apixaban levels and was significantly associated with PFA-200 closure time. The PFA-200 assay accounted for 15% of the variability in EXTEM CT-post. Additionally, difference between EXTEM CT-post and pre measurements - a robust predictor of bleeding risk, showed a significant correlation with the PFA-200 assay, and this relationship was even stronger in patients who experienced bleeding. These findings indicate that platelet dysfunction detected by PFA-200 can contribute to bleeding risk by influencing EXTEM CT. Although PFA-200 testing cannot distinguish between apixaban’s anticoagulant effect and uremia-related coagulation defects, it remains a valuable, noninvasive tool for assessing primary hemostasis in HD.

Apixaban levels could not predict bleeding. On the other hand, dosing regimen once a day not on dialysis led to subtherapeutic levels in a patient that had a thrombotic stroke. The dependence of apixaban levels (trough and peak) on drug dose regimens, without a corresponding effect on EXTEM CT, may explain the lack of a consistent relationship between drug dose and clinical response (bleeding events).

EXTEM CT is the first variable measured by the ROTEM system[28], which quantifies the time from the start of the test until the formation of a clot of a defined minimal firmness (typically reaching an amplitude of 2 mm). This measurement reflects the initiation phase of the coagulation process, which is primarily dependent on the functionality of coagulation factors in the extrinsic pathway (factor VII and thrombin generation). PT, which corresponds to EXTEM assay did not show any correlation with EXTEM CT from the ROTEM assay[28], nor did it correlate with bleeding risk. One explanation could be that PT assesses only the plasma-based extrinsic and common coagulation pathways and so it may not capture the complete hemostatic profile, especially the contributions of cellular components like platelets that influence bleeding risk. In contrast, EXTEM CT provides a more integrated assessment of coagulation by reflecting both plasma and cellular factors, making it a more sensitive indicator of bleeding risk in certain clinical settings.

Actually, ROTEM evaluates the entire coagulation process, from clot initiation to clot firmness, integrating the effects of: Coagulation factors, platelets, fibrinogen, drug action (like apixaban) and even PFA-influenced platelet function[20,21].

In our study, apixaban levels could not predict bleeding risk in dialysis patients, despite dose-dependent pharmacokinetics, whereas ROTEM CT offered a better predictive value. In line with our findings, a previous retrospective analysis from the RENAL-AF study reported that apixaban levels, measured in 50 of the 154 enrolled patients, showed no correlation with bleeding events[16]. Apixaban blood levels reflect how much drug is present, not necessarily how it affects the coagulation system in a given patient. In dialysis patients, impaired renal clearance, combined with variable absorption, metabolism, and non-renal elimination can result in inconsistent apixaban plasma level[12], but the biological response to the drug (pharmacodynamics) varies widely due to underlying comorbidities, vascular conditions, and platelet function. Certainly, uremia-induced platelet dysfunction and coagulation abnormalities[29,30], along with individual differences in protein binding, residual renal function, and dialysis timing, can mask the drug’s direct effects[12]. Thus, patient may have a low apixaban level but still bleed due to platelet abnormalities not reflected in anti-Xa assays. Also, in chronic kidney disease stage 5 with dialysis patients, changes in albumin levels and tissue distribution can affect how apixaban behaves in the body, further decoupling drug level from effect[31,32]. Finally, the integrated whole blood assessment of ROTEM, which reflects overall hemostasis including cellular components, further complicates a simple dose-response correlation[20].

Bleeding in patients with impaired renal function on anticoagulants arises from both intrinsic coagulation defects and pharmacokinetic alterations and HD patients commonly experience hemorrhagic complications due to platelet dysfunction[7]. A study on 45 HD patients assessed platelet function using the PFA-100 and found that HD partially corrects primary hemostasis dysfunction in end-stage renal disease[33].

Anticoagulants indirectly affect platelet function by inhibiting thrombin production or thrombin function, as far as thrombin is a potent platelet activator[34]. A study incubating blood with DOACs showed measurable ex vivo platelet function changes, arguing for antiplatelet effects beyond the well-known anticoagulant activities of these drugs[35]. Another study assessed the effects of apixaban from zero to highest concentration on thrombus formation and clot viscoelastic properties and concluded that only the highest apixaban concentration significantly reduced thrombus formation, fibrin association, and platelet aggregation[36]. While apixaban prolonged thromboelastometry parameters, it did not affect clot firmness.

In our study, six patients experienced bleeding events, while only one patient suffered a thrombotic event, further supporting the concern of heightened bleeding risk in anticoagulated HD patients, as highlighted in RENAL-AF study[16].

It remains challenging to identify a primary pathogenic factor responsible for bleeding or clotting tendencies in HD patients[37]. In the present small pilot study evaluating four dosing regimens of apixaban, findings indicated that dosing schedules, drug levels (both trough and peak), conventional coagulation tests, and bleeding/thrombotic assessment scores had minimal predictive value for bleeding risk. However, EXTEM CT, in combination with PFA assays, demon

Point of care tests are crucial in a modern-goal directed coagulation management to assess patients’ coagulation status and have been used to assess DOACs effect on coagulation status in the general population[18,26,38,39]. To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first to test point of care PFA-200 and ROTEM EXTEM in HD apixaban users for NVAF in order to assess the coagulability status.

In a study conducted Seyve et al[40] a DOAC dose-dependent increase in ROTEM CTs was shown. They found a dose-dependent relationship between apixaban levels and EXTEM CT, with a correlation coefficient of r = 0.77. Apixaban had only a low effect even at high concentrations. Mahamad et al[41] showed that the correlation of EXTEM CT with apixaban anti-Xa activity was 0.56, which was not significant (P = 0.72). Our study found correlation coefficients of 0.768 and 0.524 for pre-apixaban and post-apixaban administration, respectively. In a real-life study by Korpallová et al[20] 24 patients on apixaban (5 mg twice daily) showed a significant difference between trough and peak levels (126.8 ± 19.3 ng/mL vs 202.9 ± 19.7 ng/mL, P < 0.01). However, ROTEM CT values before and after apixaban administration did not differ significantly (103.0 ± 4.9 vs 117.2 ± 9.5). By comparison, in our three patients receiving the same apixaban dose without bleeding events, trough and peak levels were 176 ± 88 ng/mL and 249 ± 27 ng/mL, respectively. Their ROTEM CT values were 92 ± 10 and 106 ± 6, while the PFA-200 assay showed the lowest mean values (91 ± 11) in the group. Despite high peak apixaban levels, bleeding did not occur, likely due to minimal PFA-200 Closure Time prolongation, which limited ROTEM CT increases. These findings highlight pharmacokinetic differences in HD patients and clearly show that multiple factors influence ROTEM CT beyond apixaban levels.

This study has clinical implications, particularly given the complexities of apixaban dosing and monitoring in HD patients. Determining its clinical impact remains challenging, but our findings suggest a structured approach. The initial dose may be 2.5 mg twice daily as recommended by KDIGO guidelines[42]. After 10 days, once steady-state levels are reached, EXTEM CT and PFA-200 assays should be performed before and after dosing. If post-dose CT is below a validated threshold (e.g., 103 s) and PFA-200 remains within expected limits, regimen is continued. If values fall outside the cutoff, adjustment of the dose based on clinical judgment should be done, without requiring drug level monitoring.

Periodic ROTEM CT reassessment can guide future dose modifications, with evaluation frequency tailored to the patient’s condition. Of course, the validated ROTEM CT and PFA-200 thresholds will be derived from larger studies using various apixaban dosages in the HD setting. Such studies will help establish standardized cutoff values not only for apixaban but also for other DOACs, ensuring safer and more effective anticoagulation management.

ROTEM is a point-of-care test used to guide clinical decision-making in bleeding management for high-risk populations. Its operation and interpretation are well established in clinical practice, with applications already demonstrated in emergency departments and surgical settings[28]. A systematic review and cost-effectiveness analysis of viscoelastic point-of-care testing (including ROTEM) for the diagnosis, management, and monitoring of hemostasis found that ROTEM can reduce healthcare costs[43]. In the context of dialysis units, however, ROTEM has not yet been validated as a point-of-care tool for hemodialysis patients, despite limited reports of its potential to assess coagulation status[44]. If our findings are confirmed in larger studies, ROTEM may represent a cost-effective point-of-care option in dialysis settings, a hypothesis that merits further investigation.

The ability of EXTEM CT to predict bleeding risk was evaluated based on a small sample size. Additionally, apixaban dosing was not standardized by any specific protocol but was left to the discretion of the attending physicians. taking into account bleeding and thrombotic assessment scores. While this variability in dosing regimens posed a challenge, it did allow us to observe a lack of a clear clinical response relationship between the dose and the outcomes. The variability in dosing regimens further assisted in identifying the critical role that platelet dysfunction plays in the EXTEM CT assay. In this context, we acknowledge that future larger-scale studies incorporating a predefined anticoagulation selection score (such as a modified dialysis score) and a standardized dosing regimen (apixaban 5 mg or 2.5 mg twice daily), along with the inclusion of a control group of HD patients with NVAF not receiving anticoagulation, could provide deeper insights. Such a study design would allow for a comparative evaluation to better identify which patients on HD with NVAF may derive a net benefit from initiating anticoagulation vs those for whom the bleeding risk may outweigh potential benefits. Building on this perspective, we highlight the importance of future randomized controlled trials that incorporate viscoelastic testing and platelet function assessment into their design. Specifically, measuring ROTEM CT and PFA values at baseline in both treatment and control group, prior to initiating anticoagulation, would establish a reference point for subsequent comparisons. Repeated assessments at predefined intervals or at key clinical time points throughout the study could help monitor dynamic changes in coagulation status and platelet function. Such data would provide a more comprehensive understanding of how anticoagulation therapy influences hemostasis in HD patients with NVAF, and could improve risk stratification by identifying individuals at heightened bleeding risk early in the course of treatment.

Despite its limitations, this study also has notable strengths. First, drug levels were measured using a chromogenic anti-Xa assay, one of the most reliable and widely accepted methods for quantifying apixaban levels. Second, the analysis was conducted on real-world patients with long-term follow-up, allowing for the assessment of the clinical relevance of the coagulation parameters examined. Third, the PFA-200, a tool capable of identifying platelet-related dysfunction, was shown to influence overall coagulation, particularly affecting EXTEM CT values. Based on these findings, we propose that performing the PFA assay after apixaban administration could enhance the predictive accuracy of ROTEM CT for bleeding risk. However, this was not implemented in the present study, as only pre-dose samples were analyzed.

The ROTEM CT shows promise in identifying early bleeding risk and preventing apixaban-induced hemorrhagic events. Additionally, the PFA-200, through its influence on ROTEM CT, offers valuable insights into hemostatic status and the benefit-risk profile of apixaban exposure, which can be critical for tailoring treatment, especially in HD patients with a high risk of bleeding. Hypotheses based on our findings have to be further investigated in studies with larger sample sizes, in the entire range of apixaban exposure and in relation to clinical outcomes.

| 1. | Zimmerman D, Sood MM, Rigatto C, Holden RM, Hiremath S, Clase CM. Systematic review and meta-analysis of incidence, prevalence and outcomes of atrial fibrillation in patients on dialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27:3816-3822. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 251] [Cited by in RCA: 224] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Hindricks G, Potpara T, Dagres N, Arbelo E, Bax JJ, Blomström-Lundqvist C, Boriani G, Castella M, Dan GA, Dilaveris PE, Fauchier L, Filippatos G, Kalman JM, La Meir M, Lane DA, Lebeau JP, Lettino M, Lip GYH, Pinto FJ, Thomas GN, Valgimigli M, Van Gelder IC, Van Putte BP, Watkins CL; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS): The Task Force for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J. 2021;42:373-498. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3176] [Cited by in RCA: 6928] [Article Influence: 1385.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Nigwekar SU, Thadhani R. Long-Term Anticoagulation for Patients Receiving Dialysis. Circulation. 2018;138:1530-1533. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 4. | Harel Z, Chertow GM, Shah PS, Harel S, Dorian P, Yan AT, Saposnik G, Sood MM, Molnar AO, Perl J, Wald RM, Silver S, Wald R. Warfarin and the Risk of Stroke and Bleeding in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation Receiving Dialysis: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Can J Cardiol. 2017;33:737-746. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Randhawa MS, Vishwanath R, Rai MP, Wang L, Randhawa AK, Abela G, Dhar G. Association Between Use of Warfarin for Atrial Fibrillation and Outcomes Among Patients With End-Stage Renal Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e202175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 17.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Blum D, Beaubien-Souligny W, Battistella M, Tseng E, Harel Z, Nijjar J, Nazvitch E, Silver SA, Wald R. Quality Improvement Program Improves Time in Therapeutic Range for Hemodialysis Recipients Taking Warfarin. Kidney Int Rep. 2020;5:159-164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kumar S, Lim E, Covic A, Verhamme P, Gale CP, Camm AJ, Goldsmith D. Anticoagulation in Concomitant Chronic Kidney Disease and Atrial Fibrillation: JACC Review Topic of the Week. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74:2204-2215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 19.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Wang TK, Sathananthan J, Marshall M, Kerr A, Hood C. Relationships between Anticoagulation, Risk Scores and Adverse Outcomes in Dialysis Patients with Atrial Fibrillation. Heart Lung Circ. 2016;25:243-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | De Vriese AS, Heine G. Anticoagulation management in haemodialysis patients with atrial fibrillation: evidence and opinion. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2022;37:2072-2079. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Schurgers LJ, Joosen IA, Laufer EM, Chatrou ML, Herfs M, Winkens MH, Westenfeld R, Veulemans V, Krueger T, Shanahan CM, Jahnen-Dechent W, Biessen E, Narula J, Vermeer C, Hofstra L, Reutelingsperger CP. Vitamin K-antagonists accelerate atherosclerotic calcification and induce a vulnerable plaque phenotype. PLoS One. 2012;7:e43229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | van Zyl M, Abdullah HM, Noseworthy PA, Siontis KC. Stroke Prophylaxis in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation and End-Stage Renal Disease. J Clin Med. 2020;9:123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Schietzel S, Limacher A, Moor MB, Czerlau C, Huynh-Do U, Vogt B, Aregger F, Uehlinger DE. Apixaban dosing in hemodialysis - can drug level monitoring mitigate controversies? BMC Nephrol. 2024;25:338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Wang X, Tirucherai G, Marbury TC, Wang J, Chang M, Zhang D, Song Y, Pursley J, Boyd RA, Frost C. Pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and safety of apixaban in subjects with end-stage renal disease on hemodialysis. J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;56:628-636. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 174] [Cited by in RCA: 213] [Article Influence: 19.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Mavrakanas TA, Samer CF, Nessim SJ, Frisch G, Lipman ML. Apixaban Pharmacokinetics at Steady State in Hemodialysis Patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28:2241-2248. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 170] [Article Influence: 18.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Siontis KC, Zhang X, Eckard A, Bhave N, Schaubel DE, He K, Tilea A, Stack AG, Balkrishnan R, Yao X, Noseworthy PA, Shah ND, Saran R, Nallamothu BK. Outcomes Associated With Apixaban Use in Patients With End-Stage Kidney Disease and Atrial Fibrillation in the United States. Circulation. 2018;138:1519-1529. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 340] [Cited by in RCA: 367] [Article Influence: 45.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Pokorney SD, Chertow GM, Al-Khalidi HR, Gallup D, Dignacco P, Mussina K, Bansal N, Gadegbeku CA, Garcia DA, Garonzik S, Lopes RD, Mahaffey KW, Matsuda K, Middleton JP, Rymer JA, Sands GH, Thadhani R, Thomas KL, Washam JB, Winkelmayer WC, Granger CB; RENAL-AF Investigators. Apixaban for Patients With Atrial Fibrillation on Hemodialysis: A Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial. Circulation. 2022;146:1735-1745. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 157] [Article Influence: 39.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Reinecke H, Engelbertz C, Bauersachs R, Breithardt G, Echterhoff HH, Gerß J, Haeusler KG, Hewing B, Hoyer J, Juergensmeyer S, Klingenheben T, Knapp G, Christian Rump L, Schmidt-Guertler H, Wanner C, Kirchhof P, Goerlich D. A Randomized Controlled Trial Comparing Apixaban With the Vitamin K Antagonist Phenprocoumon in Patients on Chronic Hemodialysis: The AXADIA-AFNET 8 Study. Circulation. 2023;147:296-309. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 41.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Vedovati MC, Mosconi MG, Isidori F, Agnelli G, Becattini C. Global thromboelastometry in patients receiving direct oral anticoagulants: the RO-DOA study. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2020;49:251-258. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Pavoni V, Gianesello L, Conti D, Ballo P, Dattolo P, Prisco D, Görlinger K. "In Less than No Time": Feasibility of Rotational Thromboelastometry to Detect Anticoagulant Drugs Activity and to Guide Reversal Therapy. J Clin Med. 2022;11:1407. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Korpallová B, Samoš M, Škorňová I, Bolek T, Žolková J, Vadelová Ľ, Kubisz P, Galajda P, Staško J, Mokáň M. Assessing the hemostasis with thromboelastometry in direct oral anticoagulants-treated patients with atrial fibrillation. Thromb Res. 2020;191:38-41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Hulshof AM, Olie RH, Vries MJA, Verhezen PWM, van der Meijden PEJ, Ten Cate H, Henskens YMC. Rotational Thromboelastometry in High-Risk Patients on Dual Antithrombotic Therapy After Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021;8:788137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Paniccia R, Priora R, Liotta AA, Abbate R. Platelet function tests: a comparative review. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2015;11:133-148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 277] [Cited by in RCA: 333] [Article Influence: 30.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Rockwood K, Song X, MacKnight C, Bergman H, Hogan DB, McDowell I, Mitnitski A. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ. 2005;173:489-495. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4103] [Cited by in RCA: 6251] [Article Influence: 297.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (17)] |

| 24. | Charlson ME, Carrozzino D, Guidi J, Patierno C. Charlson Comorbidity Index: A Critical Review of Clinimetric Properties. Psychother Psychosom. 2022;91:8-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 1059] [Article Influence: 264.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Schulman S, Kearon C; Subcommittee on Control of Anticoagulation of the Scientific and Standardization Committee of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis. Definition of major bleeding in clinical investigations of antihemostatic medicinal products in non-surgical patients. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3:692-694. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3234] [Cited by in RCA: 4111] [Article Influence: 195.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Tsantes AE, Kyriakou E, Bonovas S, Chondrogianni M, Zompola C, Liantinioti C, Simitsi A, Katsanos AH, Atta M, Ikonomidis I, Kapsimali V, Kopterides P, Tsivgoulis G. Impact of dabigatran on platelet function and fibrinolysis. J Neurol Sci. 2015;357:204-208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Cini M, Legnani C, Padrini R, Cosmi B, Dellanoce C, De Rosa G, Marcucci R, Pengo V, Poli D, Testa S, Palareti G. DOAC plasma levels measured by chromogenic anti-Xa assays and HPLC-UV in apixaban- and rivaroxaban-treated patients from the START-Register. Int J Lab Hematol. 2020;42:214-222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Drotarova M, Zolkova J, Belakova KM, Brunclikova M, Skornova I, Stasko J, Simurda T. Basic Principles of Rotational Thromboelastometry (ROTEM(®)) and the Role of ROTEM-Guided Fibrinogen Replacement Therapy in the Management of Coagulopathies. Diagnostics (Basel). 2023;13:3219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 17.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Boccardo P, Remuzzi G, Galbusera M. Platelet dysfunction in renal failure. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2004;30:579-589. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 292] [Cited by in RCA: 321] [Article Influence: 15.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Pavlou EG, Georgatzakou HT, Fortis SP, Tsante KA, Tsantes AG, Nomikou EG, Kapota AI, Petras DI, Venetikou MS, Papageorgiou EG, Antonelou MH, Kriebardis AG. Coagulation Abnormalities in Renal Pathology of Chronic Kidney Disease: The Interplay between Blood Cells and Soluble Factors. Biomolecules. 2021;11:1309. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Otero A, Rosselló-Palmer E, Codina S, Lloberas N, Martínez Y, Santos N, Peñafiel J, Rigo-Bonnin R, Vidal A, Peris J, Videla S, Hueso M. Exploring Apixaban Pharmacokinetics, Pharmacodynamics, and Safety in Hemodiafiltration Patients. Kidney Int Rep. 2024;9:2798-2802. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Byon W, Garonzik S, Boyd RA, Frost CE. Apixaban: A Clinical Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Review. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2019;58:1265-1279. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 237] [Article Influence: 39.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Bilgin AU, Karadogan I, Artac M, Kizilors A, Bligin R, Undar L. Hemodialysis shortens long in vitro closure times as measured by the PFA-100. Med Sci Monit. 2007;13:CR141-CR145. [PubMed] |

| 34. | Coughlin SR. Thrombin signalling and protease-activated receptors. Nature. 2000;407:258-264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1911] [Cited by in RCA: 1895] [Article Influence: 72.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Renda G, Bucciarelli V, Barbieri G, Lanuti P, Berteotti M, Malatesta G, Cesari F, Salvatore T, Giusti B, Gori AM, Marcucci R, De Caterina R. Ex Vivo Antiplatelet Effects of Oral Anticoagulants. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis. 2024;11:111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Pujadas-Mestres L, Lopez-Vilchez I, Arellano-Rodrigo E, Reverter JC, Lopez-Farre A, Diaz-Ricart M, Badimon JJ, Escolar G. Differential inhibitory action of apixaban on platelet and fibrin components of forming thrombi: Studies with circulating blood and in a platelet-based model of thrombin generation. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0171486. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Genovesi S, Camm AJ, Covic A, Burlacu A, Meijers B, Franssen C, Luyckx V, Liakopoulos V, Alfano G, Combe C, Basile C. Treatment strategies of the thromboembolic risk in kidney failure patients with atrial fibrillation. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2024;39:1248-1257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Sahli SD, Rössler J, Tscholl DW, Studt JD, Spahn DR, Kaserer A. Point-of-Care Diagnostics in Coagulation Management. Sensors (Basel). 2020;20:4254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Kyriakou E, Katogiannis K, Ikonomidis I, Giallouros G, Nikolopoulos GK, Rapti E, Taichert M, Pantavou K, Gialeraki A, Kousathana F, Poulis A, Tsantes AG, Bonovas S, Kapsimali V, Tsivgoulis G, Tsantes AE. Laboratory Assessment of the Anticoagulant Activity of Apixaban in Patients With Nonvalvular Atrial Fibrillation. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2018;24:194S-201S. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Seyve L, Richarme C, Polack B, Marlu R. Impact of four direct oral anticoagulants on rotational thromboelastometry (ROTEM). Int J Lab Hematol. 2018;40:84-93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Mahamad S, Chaudhry H, Nisenbaum R, McFarlan A, Rizoli S, Ackery A, Sholzberg M. Exploring the effect of factor Xa inhibitors on rotational thromboelastometry: a case series of bleeding patients. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2019;47:272-279. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Wanner C, Herzog CA, Turakhia MP; Conference Steering Committee. Chronic kidney disease and arrhythmias: highlights from a Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Controversies Conference. Kidney Int. 2018;94:231-234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Whiting P, Al M, Westwood M, Ramos IC, Ryder S, Armstrong N, Misso K, Ross J, Severens J, Kleijnen J. Viscoelastic point-of-care testing to assist with the diagnosis, management and monitoring of haemostasis: a systematic review and cost-effectiveness analysis. Health Technol Assess. 2015;19:1-228, v. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 174] [Cited by in RCA: 212] [Article Influence: 21.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Gäckler A, Rohn H, Lisman T, Benkö T, Witzke O, Kribben A, Saner FH. Evaluation of hemostasis in patients with end-stage renal disease. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0212237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/