Copyright

©The Author(s) 2026.

World J Cardiol. Feb 26, 2026; 18(2): 113358

Published online Feb 26, 2026. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v18.i2.113358

Published online Feb 26, 2026. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v18.i2.113358

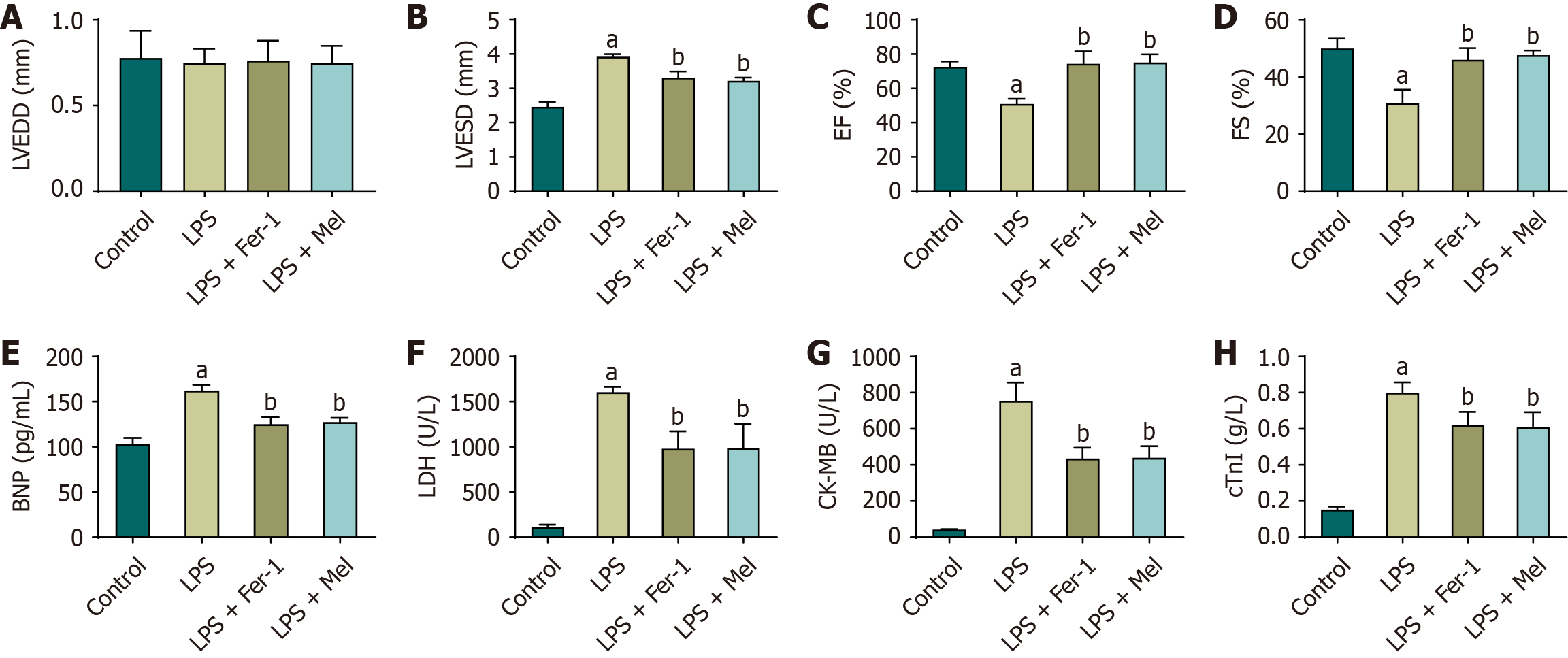

Figure 1 Melatonin alleviates lipopolysaccharide-induced cardiac dysfunction in vivo.

A-D: Echocardiography 24 hours after lipopolysaccharide injection: Left ventricular end-diastolic diameter (A); left ventricular end-systolic diameter (B); ejection fraction (C); and fractional shortening (D); E-H: Serum cardiac injury markers: Brain natriuretic peptide (E); lactate dehydrogenase (F); creatine kinase-MB (G); and cardiac troponin I (F). Data are expressed as mean ± SD; n = 6 mice per group. Group differences were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni post-hoc testing. aP < 0.01 vs control; bP < 0.01 vs lipopolysaccharide. BNP: Brain natriuretic peptide; CK-MB: Creatine kinase-MB; cTnI: Cardiac troponin I; EF: Ejection fraction; FS: Fractional shortening; LDH: Lactate dehydrogenase; LPS: Lipopolysaccharide; LPS + Mel: Lipopolysaccharide plus melatonin; LPS + Fer-1: Lipopolysaccharide plus ferrostatin-1; LVEDD: Left ventricular end-diastolic diameter; LVESD: Left ventricular end-systolic diameter.

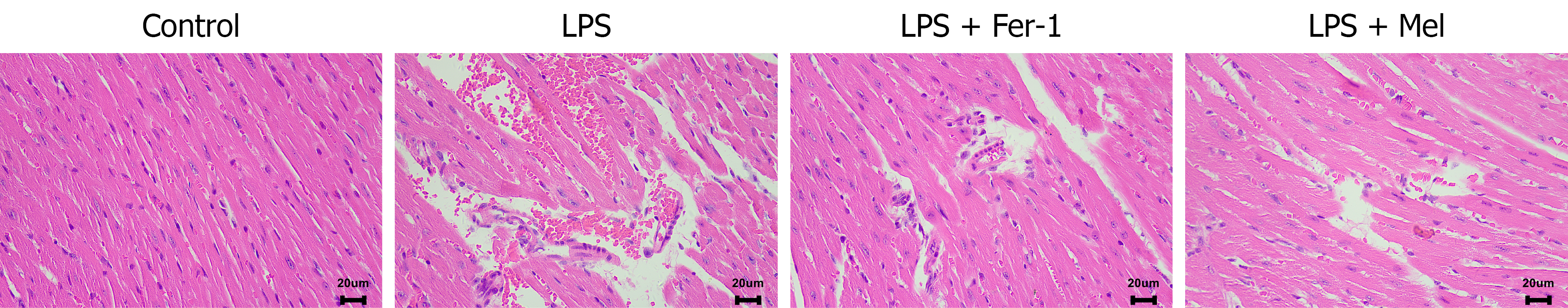

Figure 2 Histopathology of lipopolysaccharide-induced myocardial injury and protection by melatonin.

Representative hematoxylin and eosin-stained myocardial sections from control, lipopolysaccharide (LPS), LPS plus ferrostatin-1, and LPS plus melatonin groups 24 hours after LPS injection. The LPS group shows interstitial edema, hemorrhage/congestion, myofibrillar disruption, and inflammatory cell infiltration; these changes are attenuated in LPS plus ferrostatin-1 and LPS plus melatonin. Representative images from n = 6 mice per group; scale bar = 20 μm. LPS: Lipopolysaccharide; LPS + Mel: Lipopolysaccharide plus melatonin; LPS + Fer-1: Lipopolysaccharide plus ferrostatin-1.

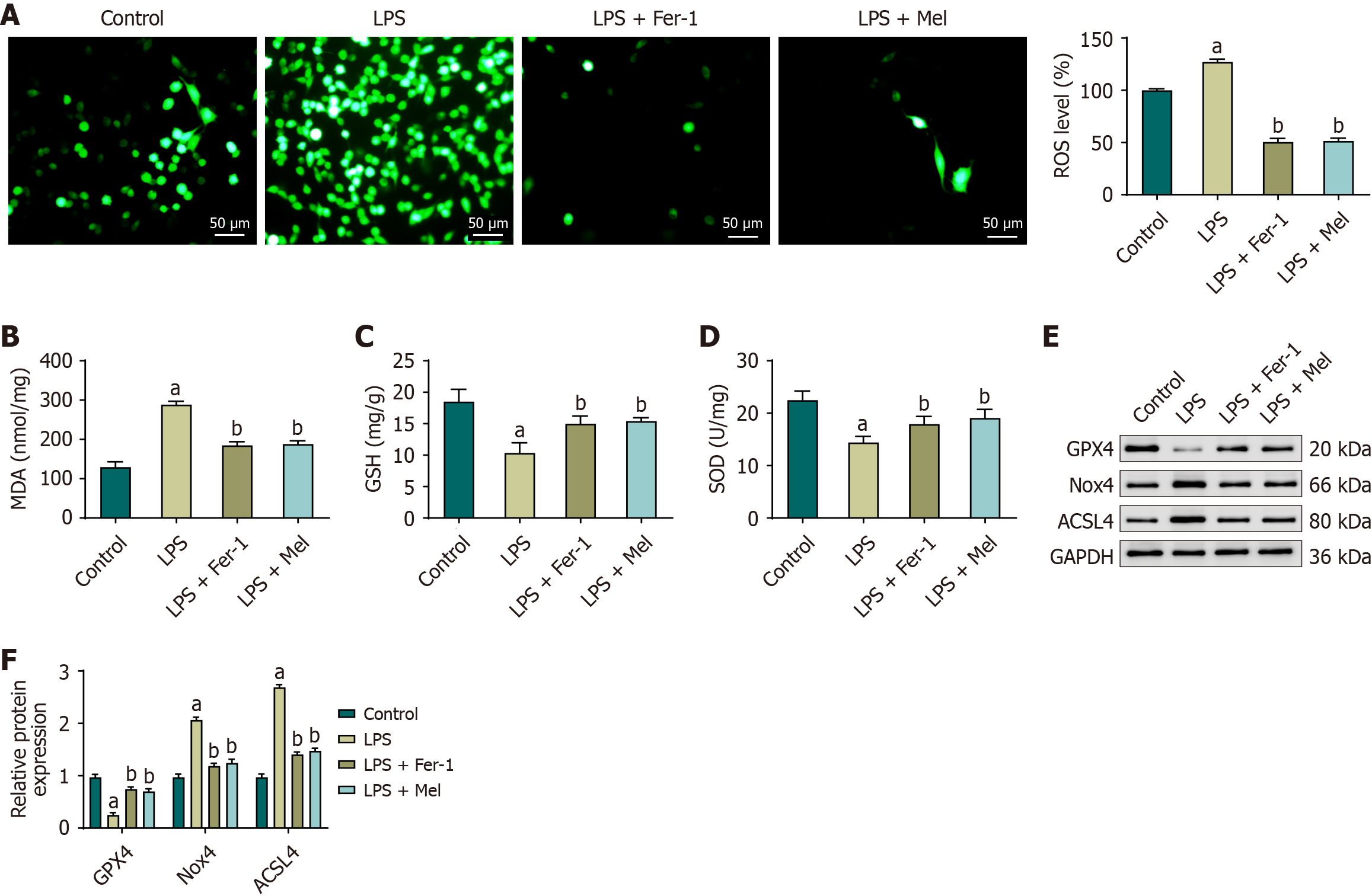

Figure 3 Melatonin reduces oxidative stress and ferroptosis-related proteins in mouse cardiac tissue.

A: Myocardial reactive oxygen species measured by 2’,7’-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate fluorescence microscopy with quantitative analysis; B-D: Cardiac malondialdehyde, glutathione, and superoxide dismutase activity; E: Representative immunoblots of glutathione peroxidase 4, NADPH oxidase 4, and acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4 in cardiac tissue (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase loading control); F: Densitometric quantification normalized to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. Data are mean ± SD; n = 6 mice per group. One-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni post-hoc testing. aP < 0.01 vs control; bP < 0.01 vs lipopolysaccharide. ACSL4: Acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4; GAPDH: Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; GPX4: Glutathione peroxidase 4; GSH: Glutathione; LPS: Lipopolysaccharide; LPS + Mel: Lipopolysaccharide plus melatonin; LPS + Fer-1: Lipopolysaccharide plus ferrostatin-1; MDA: Malondialdehyde; Nox4: NADPH oxidase 4; ROS: Reactive oxygen species; SOD: Superoxide dismutase.

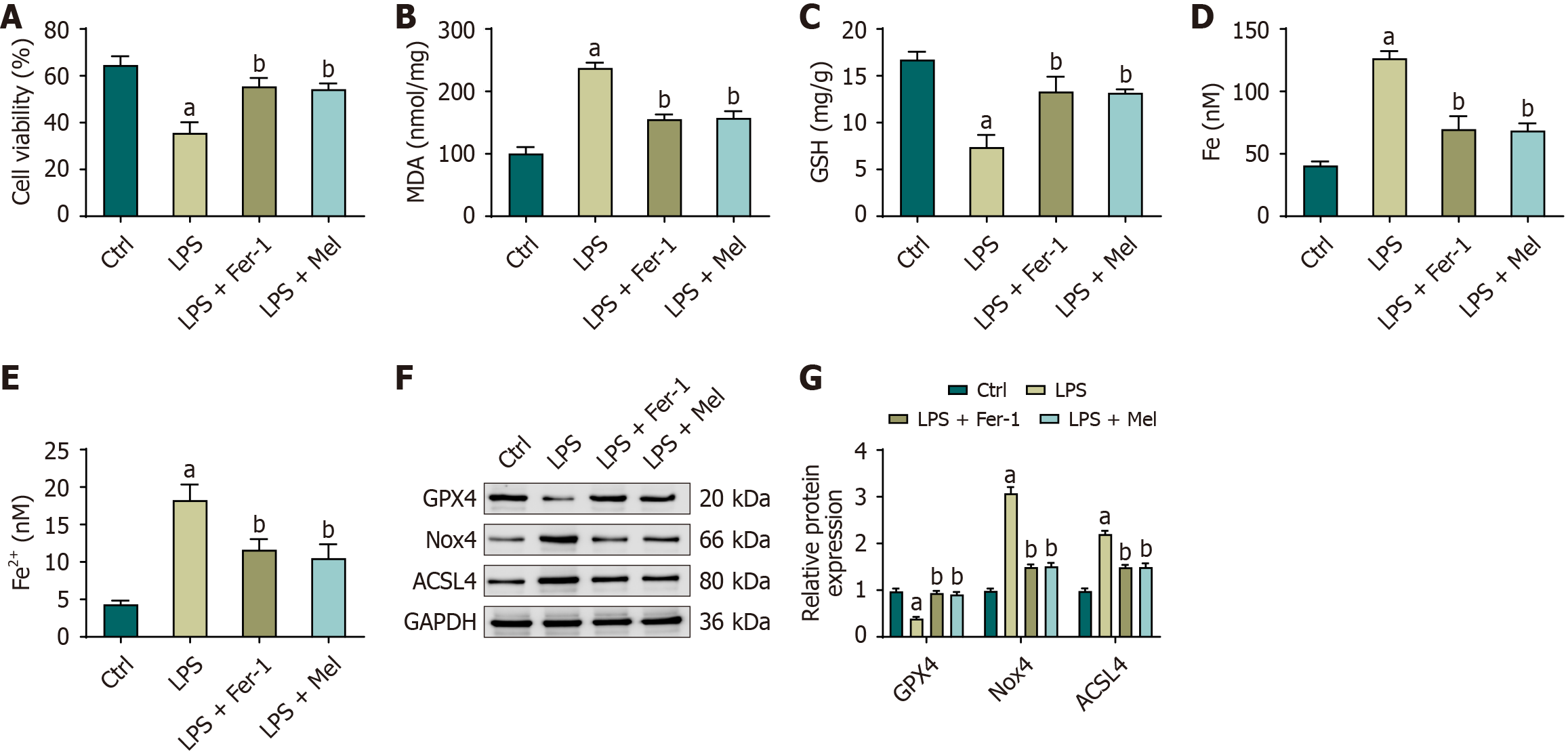

Figure 4 Melatonin improves viability, redox balance, and ferroptosis markers in HL-1 cardiomyocytes.

A: Cell viability assessed by cell counting kit-8; B-E: Cellular malondialdehyde, glutathione, total iron, and ferrous iron after treatment with lipopolysaccharide with or without ferrostatin-1 or melatonin; F: Representative immunoblots of glutathione peroxidase 4, NADPH oxidase 4, and acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4 (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase as control); G: Densitometric quantification normalized to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. Data are presented as mean ± SD from three independent biological experiments (each measured in technical triplicate). One-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni post-hoc testing. aP < 0.01 vs control; bP < 0.01 vs lipopolysaccharide. ACSL4: Acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4; Ctrl: Control; Fe2+: Ferrous iron; GAPDH: Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; GPX4: Glutathione peroxidase 4; GSH: Glutathione; LPS: Lipopolysaccharide; LPS + Mel: Lipopolysaccharide plus melatonin; LPS + Fer-1: Lipopolysaccharide plus ferrostatin-1; MDA: Malondialdehyde; Nox4: NADPH oxidase 4.

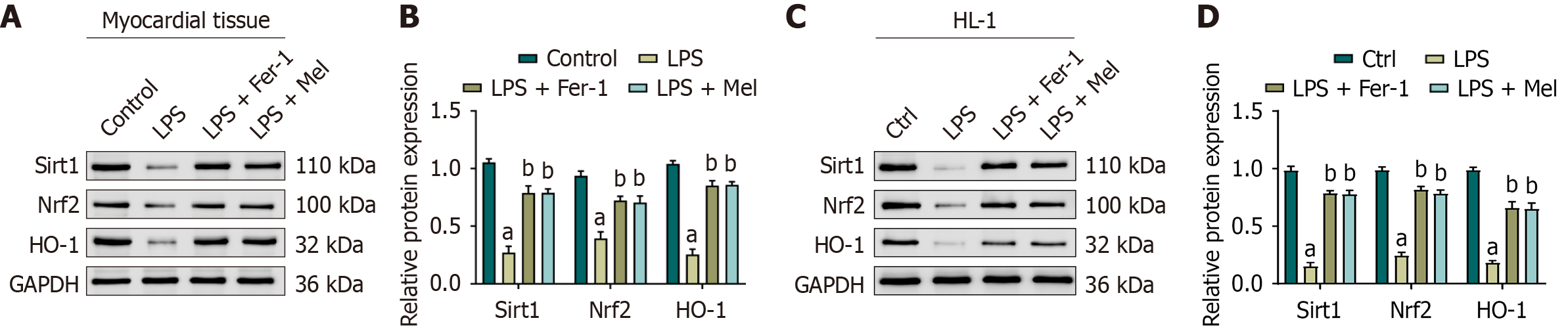

Figure 5 Melatonin activates the sirtuin 1/nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 axis in vivo and in vitro.

A: Representative immunoblots of sirtuin 1, nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2, and heme oxygenase-1 in mouse myocardial tissue (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase as control); B: Densitometric quantification normalized to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (in vivo); C: Representative immunoblots of sirtuin 1, nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2, and heme oxygenase-1 in HL-1 cells; D: Densitometric quantification (in vitro). Data are expressed as mean ± SD; in vivo n = 6 mice per group; in vitro n = 3 independent experiments. One-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni post-hoc testing. aP < 0.01 vs control; bP < 0.01 vs lipopolysaccharide. Ctrl: Control; GAPDH: Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; HO-1: Heme oxygenase-1; LPS: Lipopolysaccharide; LPS + Mel: Lipopolysaccharide plus melatonin; LPS + Fer-1: Lipopolysaccharide plus ferrostatin-1; Nrf2: Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2; Sirt1: Sirtuin 1.

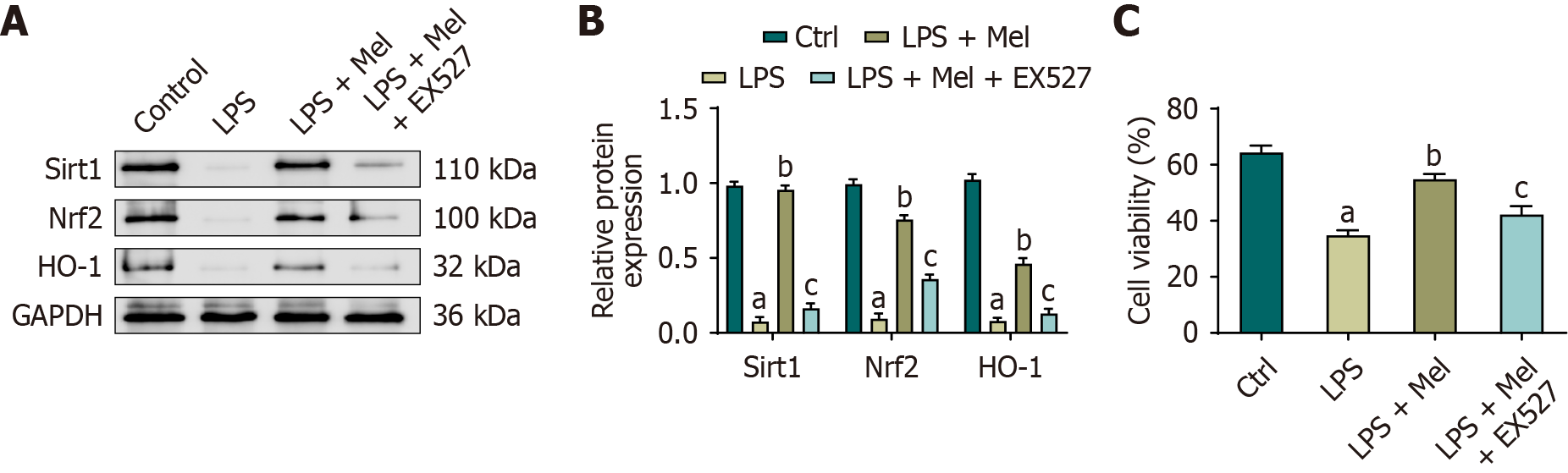

Figure 6 Sirtuin 1 inhibition weakens melatonin-induced sirtuin 1/nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2/heme oxygenase-1 signaling and cytoprotection in HL-1 cells.

A and B: Representative immunoblots and quantification of sirtuin 1, nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2, and heme oxygenase-1 in HL-1 cells treated with lipopolysaccharide, melatonin, or melatonin plus the sirtuin 1 inhibitor EX527 (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase as control); C: Cell viability assessed by cell counting kit-8 under the same conditions. Data are presented as mean ± SD from three independent biological experiments (each measured in technical triplicate). One-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni post-hoc testing. aP < 0.01 vs control; bP < 0.01 vs lipopolysaccharide; cP < 0.01 vs lipopolysaccharide plus melatonin. Ctrl: Control; GAPDH: Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; HO-1: Heme oxygenase-1; LPS: Lipopolysaccharide; LPS + Mel: Lipopolysaccharide plus melatonin; LPS + Fer-1: Lipopolysaccharide plus ferrostatin-1; Nrf2: Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2; Sirt1: Sirtuin 1.

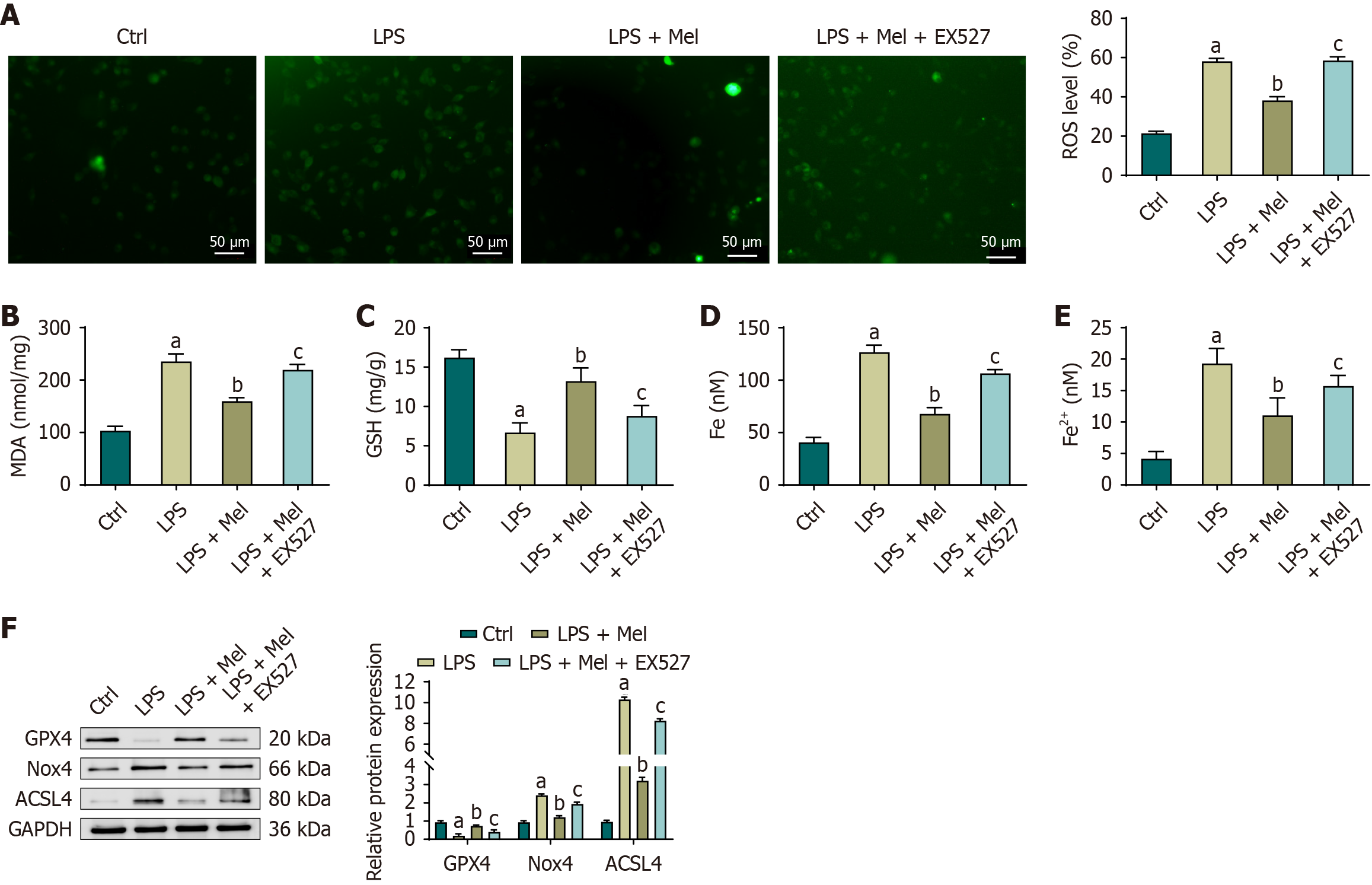

Figure 7 Melatonin protects HL-1 cells from lipopolysaccharide-induced oxidative damage and lipid peroxidation primarily through a sirtuin 1-dependent mechanism.

A: Myocardial reactive oxygen species measured by 2’,7’-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate fluorescence microscopy with quantitative analysis; B-E: Cellular malondialdehyde, glutathione, total iron, and ferrous iron after treatment with lipopolysaccharide with or without melatonin or EX527; F: Representative immunoblots of glutathione peroxidase 4, NADPH oxidase 4, and acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4 in cardiac tissue (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase loading control) and densitometric quantification normalized to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. One-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni post-hoc testing. aP < 0.01 vs control; bP < 0.01 vs lipopolysaccharide; cP < 0.01 vs lipopolysaccharide plus melatonin. ACSL4: Acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4; Ctrl: Control; Fe2+: Ferrous iron; GAPDH: Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; GPX4: Glutathione peroxidase 4; GSH: Glutathione; LPS: Lipopolysaccharide; LPS + Mel: Lipopolysaccharide plus melatonin; LPS + Fer-1: Lipopolysaccharide plus ferrostatin-1; MDA: Malondialdehyde; Nox4: NADPH oxidase 4; ROS: Reactive oxygen species.

- Citation: Zeng M, Li Q, Li L, Xiang CF, Wang YJ. Melatonin regulates Sirt1/Nrf2/GPX4 pathway to inhibit ferroptosis and alleviate myocardial injury caused by sepsis. World J Cardiol 2026; 18(2): 113358

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v18/i2/113358.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v18.i2.113358