Published online Dec 5, 2025. doi: 10.4331/wjbc.v16.i4.111156

Revised: July 11, 2025

Accepted: October 22, 2025

Published online: December 5, 2025

Processing time: 163 Days and 13.4 Hours

Alzheimer's disease is a neurodegenerative dementia characterized by accumulation of β-amyloid plaques, tau hyperphosphorylation, and neuroinflammation. Recent research has highlighted a potential relationship between chronic oral infections and neurodegeneration, particularly the involvement of Porphyromonas gingivalis (P. gingivalis), a key pathogen in periodontitis. Experimental mouse mo

To link gingival P. gingivalis bacteria-associated products with the onset and pro

This systematic review followed the 2020 PRISMA guidelines. A comprehensive search was conducted in five databases (PubMed, Scopus, ScienceDirect, Sage, SpringerLink) for original studies between 2014 and 2024. Studies included mouse models to evaluate the effect of P. gingivalis or its products on Alzheimer's-like pa

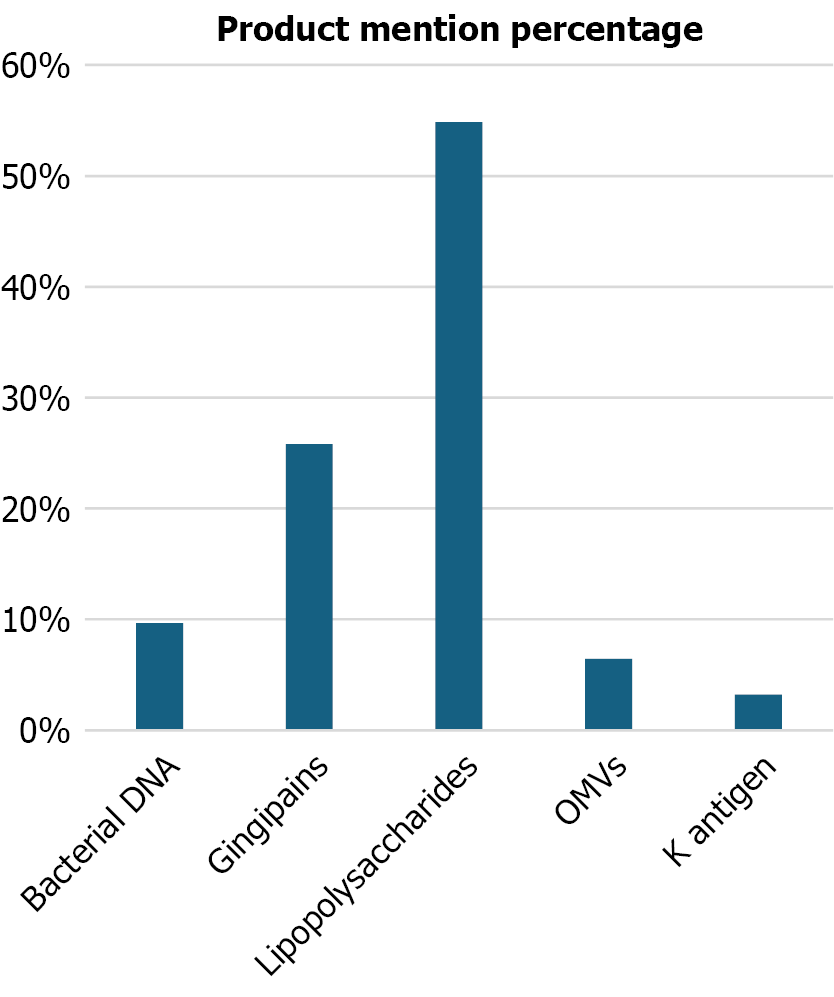

In 24 studies, lipopolysaccharides (54.84%) and gingipains (25.81%) were the most frequently reported P. gingivalis products. These factors activated toll-like receptors (TLR2/TLR4), microglia, and astrocytes, increasing levels of interleukin 1 beta, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, and other proinflammatory cytokines. The host response included

P. gingivalis products induce neuroinflammatory responses and Alzheimer's-like pathology in mouse models, supporting their role as contributors to neurodegeneration and potential targets for preventive strategies.

Core Tip: This review shows the role of Porphyromonas gingivalis (P. gingivalis)-derived products in Alzheimer's disease-like pathology in murine models. Lipopolysaccharides and gingipains were the most implicated bacterial factors, activating glial cells and proinflammatory pathways. These interactions resulted in β-amyloid accumulation, tau hyperphosphorylation, and cognitive impairment. Our analysis highlights the importance of chronic oral infection in the progression of Alzheimer's disease and supports P. gingivalis treatment as a potential preventive strategy.

- Citation: Ochoa KL, Heredia AG, Piedra CC, Arias RJ, Ortiz BJ, Dominguez-Gortaire JA. Association between Alzheimer's disease and Porphyromonas gingivalis products in murine models: A systematic review. World J Biol Chem 2025; 16(4): 111156

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8454/full/v16/i4/111156.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4331/wjbc.v16.i4.111156

Alzheimer's disease is a progressive neurodegenerative pathology that represents the most common cause of dementia in the elderly population[1]. Its clinical manifestation includes cognitive impairment, memory loss, behavioral changes, and functional alterations that profoundly affect quality of life. At the pathophysiological level, it is characterized by the accumulation of extracellular β-amyloid (Aβ) plaques, neurofibrillary tangles of hyperphosphorylated Tau protein, and chronic neuroinflammation[2,3].

In recent decades, studies carried out in murine models have become relevant in the understanding of these processes, as they allow the molecular events involved in the progression of the disease to be observed in a controlled manner. These models have facilitated the identification of proinflammatory pathways, Aβ accumulation, and synaptic alterations induced by various factors, including infectious agents[2].

In this context, a possible connection between chronic infections in the oral cavity and the development of neurological diseases, including Alzheimer's disease, has been raised. Multiple studies have associated periodontal diseases with a greater systemic inflammatory burden, which could act as a risk factor in the progression of neurodegenerative path

The pathogenicity of P. gingivalis has been attributed to various bacterial products and structures, such as lipopolysaccharides (LPS), gingipains, outer membrane vesicles (OMVs), and bacterial DNA[6]. These components can induce sustained activation of immune cells such as microglia and astrocytes, promote mitochondrial dysfunction, activate TLR-type receptors and promote the formation of Aβ plaques and alteration´s in the Tau protein[7]. In experimental studies, it has been shown that these bacterial factors can alter the neuroimmune balance, promoting states of sustained neuroinflammation that contribute to the pathophysiology of Alzheimer's[5,7].

Scientific interest in understanding this interaction has increased due to the increasing prevalence of neurodegenerative diseases globally. Alzheimer's disease represents one of the main causes of disability in the elderly, with a high social, family, and economic impact. From a public health perspective, understanding the possible triggers or modulators of this disease becomes a priority, especially if it involves potentially preventable factors such as chronic infections[2].

This study becomes relevant in this context because although there is previous research that relates P. gingivalis with Alzheimer's, most of them focus on clinical, in vitro, or epidemiological studies. In contrast, studies in murine models allow us to observe, under controlled experimental conditions, how the products of this bacterium interact with immunological factors of the host and how these interactions could predispose to the development of neurodegenerative alterations. In addition, the ethical limitations of performing this type of invasive analysis in humans reinforce the value of the preclinical approach[8].

Therefore, the aim of this systematic review was to analyze, based on the experimental evidence available in murine models, the relationship between the pathogenicity of P. gingivalis and the neuroinflammation processes involved in Alzheimer's disease. The aim was to identify the main bacterial products evaluated, the activated host factors, and the interaction patterns that could be involved in the progression of this neurodegenerative pathology.

This systematic review follows the parameters of the PRISMA 2020 statement for reporting[9].

The literature search included only original articles published in English from the last 10 years (2014-2024) investigating infection with P. gingivalis in murine models, and its possible association with pathological mechanisms related to Alzheimer's disease. On March 31, 2025, all the members prepared a joint search in five academic databases: PubMed, Sage Pub, Science Direct, Scopus, and Springer Link; using the following operators or terms homogeneously in all academic databases: "Porphyromonas gingivalis" AND (alzheimer) NOT (humans). This search strategy was directly copied and pasted into each database’s search bar.

Filters were used to retrieve only original research articles, published in English between 2014 and 2024. Gray literature, such as theses or conference proceedings, was explicitly excluded. This decision was based on the need to include only original, peer-reviewed studies with well-defined experimental designs and validated results, in order to ensure methodological consistency and data reliability.

After the search, the selection of the original studies was carried out through a previous screening of titles, abstracts, and methodologies, those that had methodologies focused on human research or only in vitro research were not considered. This selection phase was established together with all the team and in a consensual manner and was also recorded in a flow chart following the PRISMA guidelines (Figure 1). The selected articles were organized in the Mendeley manager for organization and reference control, where each member of this review was randomly assigned to read the full text for the respective data extraction.

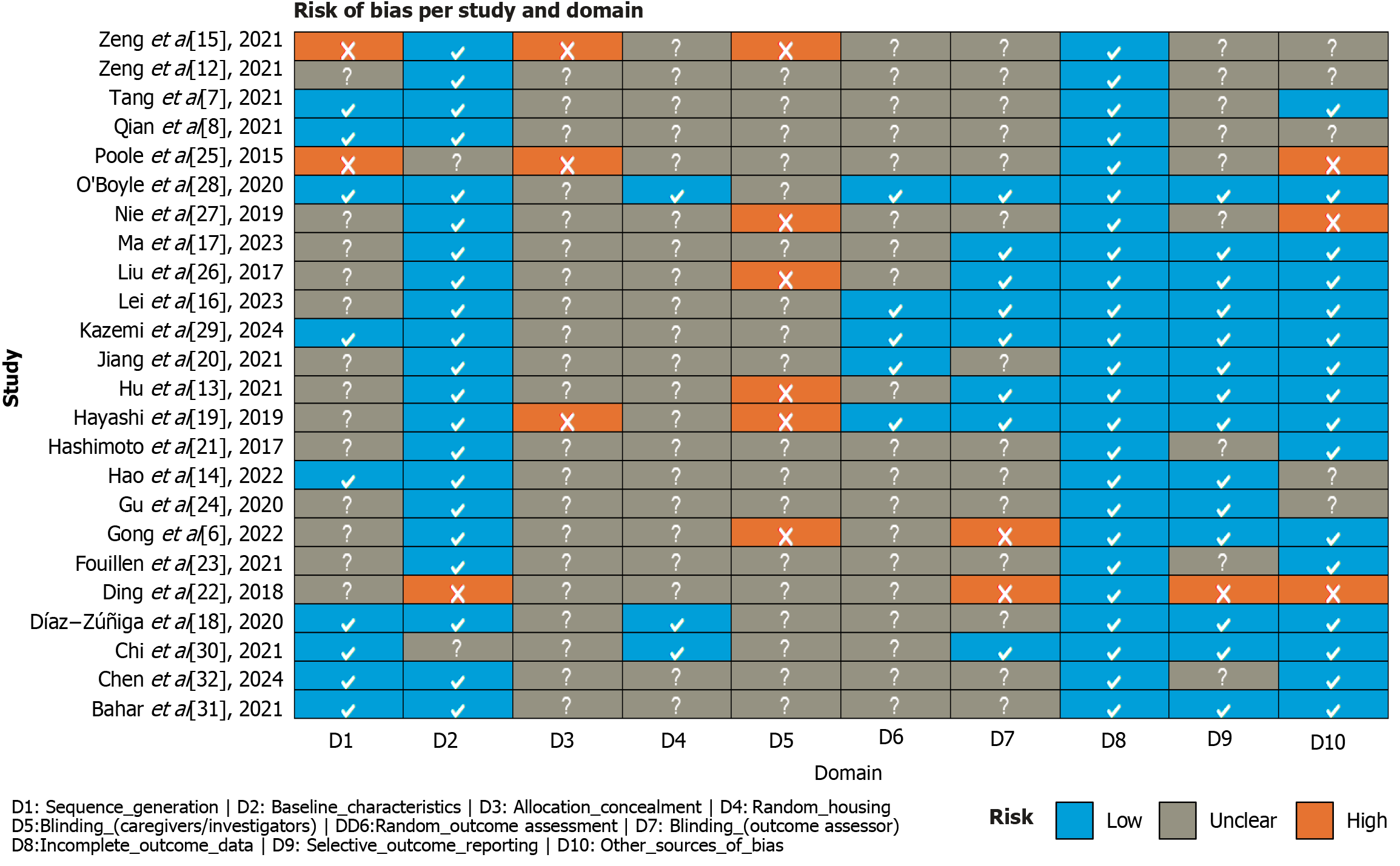

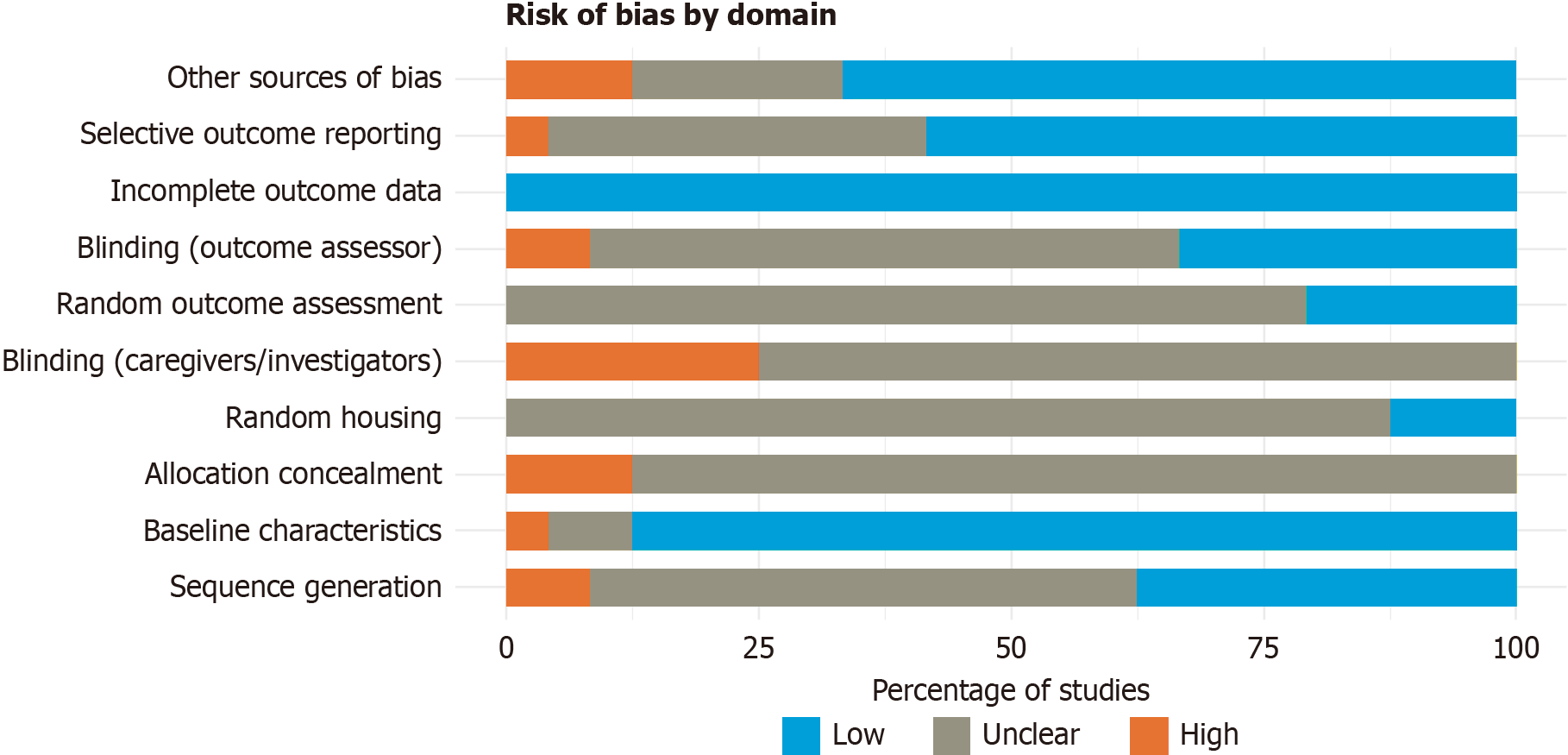

The risk of bias for each included study was assessed using the SYRCLE’s risk of bias tool for animal studies[10], an adaptation of the Cochrane tool specifically designed for preclinical models. This instrument evaluates ten domains across different types of bias, including: Random sequence generation, baseline characteristics, allocation concealment, random housing, blinding of caregivers and investigators, random outcome assessment, blinding of outcome assessors, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting, and other potential sources of bias. For each domain, the risk was categorized as “low”, “high”, or “unclear”, depending on the methodological details reported in each study. To ensure balanced evaluation, all included articles were distributed randomly among reviewer pairs, which were also assigned at random. Any disagreements were resolved through consensus.

The information was organized in a database developed in Microsoft Excel version 2016, in which the relevant data of each article were recorded in narrative synthesis, including authors, DOI, keywords, main results, pharmacological treatments, recommendations, and conclusions. In addition, a specific section dedicated to classifying the products or structures of P. gingivalis involved in neuroinflammation was incorporated. Likewise, the host factors mentioned in the studies that are activated by P. gingivalis infection and that contribute to the development of Alzheimer's disease were documented.

These extraction parameters were previously defined to group the studies in the narrative synthesis according to bacterial products/structures, and activated host factors related to neuroinflammatory processes associated with Alzheimer's. The collection was not limited to a single time point of the experiments; Results that were representative of the evolution of the pathological process throughout the study were considered. The synthesis of the results was carried out using a structured narrative approach, complemented by descriptive statistics.

The search algorithm stood out with 283 records across the 5 databases, and then began the selection process by first eliminating 19 duplicates, which left a total of 264 records, after other exclusion criteria (non-original articles within the range of 2014-2024, n = 188; in vitro studies; or human research), 24 articles were included in the final analysis, as shown in Figure 1.

Among the full-text articles assessed, some studies were excluded despite appearing relevant based on title and abstract. For example, Ide et al[11] was a prospective cohort study in humans that evaluated the association between periodontal infection and cognitive decline. Although it addressed the link between P. gingivalis and Alzheimer’s disease, it did not meet the inclusion criteria because it lacked a preclinical experimental model. This review focused exclusively on original experimental studies using murine models to better characterize mechanistic pathways under controlled conditions.

The results of the risk of bias assessment are presented in Figure 2[6-8,12-32] and 3. Most articles showed a low risk of bias across several domains, particularly in D2 (baseline characteristics), where the vast majority of studies adequately reported group homogeneity at the beginning of the experiments. Likewise, all included studies showed a low risk in D8 (incomplete outcome data), D9 (selective outcome reporting), and D10 (other sources of bias), reinforcing the overall strength of the evidence analyzed.

On the other hand, D3 (allocation concealment) and D5 (blinding of caregivers/investigators) had the highest proportion of unclear risk, likely due to limited methodological reporting—a common issue in preclinical studies—even though such procedures may have been implemented. Nevertheless, unclear reporting in these domains does not necessarily imply flawed methodology, as the included studies overall demonstrated adequate methodological quality, particularly in controlling baseline variables and ensuring the consistency and integrity of the data reported.

Then, the characteristics of the 24 studies included in this systematic review were initially organized in a structured matrix table, where key information such as authors, year of publication, DOI or access link, and keywords used were collected. However, from this table, it was possible to extract information on the bacterial products and host factors mentioned in the studies (Table 1)[6-8,12-32].

| Ref. | Product or structure of the bacterium | Host factors | Factor type |

| Zeng et al[12], 2021 | LPS | TGF-β1 | Cytokine |

| Cofilina-2 | Protein | ||

| PP2A (phosphorylated/inactive) | Enzyme | ||

| Tang et al[7], 2021 | LPS | IL-1β | Cytokine |

| TNF-α | Cytokine | ||

| IL-6 | Cytokine | ||

| GFAP | Protein | ||

| Microglia | Glial cells | ||

| Astrocytes | Glial cells | ||

| Zeng et al[15], 2021 | LPS | TLR2 | PRR |

| NF-κB | Transcription factor | ||

| CatB | Enzyme | ||

| TLR4 | PRR | ||

| Gingipains | C3 | Complement system | |

| C5 | Complement system | ||

| Qian et al[8], 2021 | LPS | IL-1β | Cytokine |

| NOS | Enzyme | ||

| COX-2 | Enzyme | ||

| TNF-α | Cytokine | ||

| APP | Protein | ||

| BACE1 | Enzyme | ||

| ADAM10 | Enzyme | ||

| Hu et al[13], 2021 | LPS | TLR | PRR |

| NF-κB | Transcription factor | ||

| STAT3 | Transcription factor | ||

| Interleukins | Cytokine | ||

| APP | Protein | ||

| Amyloid-β | Peptide | ||

| Presenilin | Protein | ||

| JAK2 | Kinases | ||

| Astrocytes | Glial cells | ||

| Microglia | Glial cells | ||

| Hayashi et al[19], 2019 | LPS | Iba-1 | Marker |

| CD3 | Marker | ||

| Jiang et al[20], 2021 | LPS | Tau | Protein |

| GSK3β | Kinases | ||

| Iba-1 | Marker | ||

| TNF-α | Cytokine | ||

| Gong et al[6], 2022 | MVNOs | IL-1β | Cytokine |

| Microglia | Glial cells | ||

| Hashimoto et al[21], 2017 | LPS | TLR2 | PRR |

| TLR4 | PRR | ||

| CD36 | Protein | ||

| CD204 | Protein | ||

| Ding et al[22], 2018 | LPS | ||

| Fouillen et al[23], 2021 | Gingipains | SCPPPQ1 | Protein |

| Hao et al[14], 2022 | LPS | C1q | Complement system |

| Gu et al[24], 2020 | LPS | IL-6 | Cytokine |

| IL-17 | Cytokine | ||

| Poole et al[25], 2015 | Bacterial DNA | Microglia | Glial cells |

| Liu et al[26], 2017 | Gingipains | Microglia | Glial cells |

| Nie et al[27], 2019 | LPS | Monocytes | Immune cells |

| Ma et al[17], 2023 | MVNOs | Trigeminal neurons | Neurons |

| O'Boyle et al[28], 2020 | LPS | Circulatory system | Structural |

| Brain | Structural | ||

| Lei et al[16], 2023 | Gingipains | BBB | Structural |

| Caveolin1 | Protein | ||

| MFSD2A | Protein | ||

| Albumin | Protein | ||

| Caveolar vesicles | Protein | ||

| Kazemi et al[29], 2024 | Lactobacillus sp. | Bacteria | |

| Trace elements | Essential minerals | ||

| Chi et al[30], 2021 | LPS | Dysbiotic gut microbiota | Bacteria |

| Gingipains | Microglia | Glial cells | |

| Astrocytes | Glial cells | ||

| Amyloid-β | Peptide | ||

| Myeloid cells | Immune cells | ||

| Lymphocytes | Immune cells | ||

| Bahar et al[31], 2021 | LPS | Microglia | Glial cells |

| Gingipains | Astrocytes | Glial cells | |

| Bacterial DNA | |||

| Díaz-Zúñiga et al[18], 2020 | K antigen | Microglia | Glial cells |

| Gingipains | Astrocytes | Glial cells | |

| LPS | Macrophages | Immune cells | |

| Lymphocytes | Immune cells | ||

| Th1/Th17 | Immune cells | ||

| Chen et al[32], 2024 | LPS | Microglia | Glial cells |

| Gingipains | Astrocytes | Glial cells | |

| Bacterial DNA | Amyloid-β | Peptide | |

| Nrf2/HO-1 | Transcription factor |

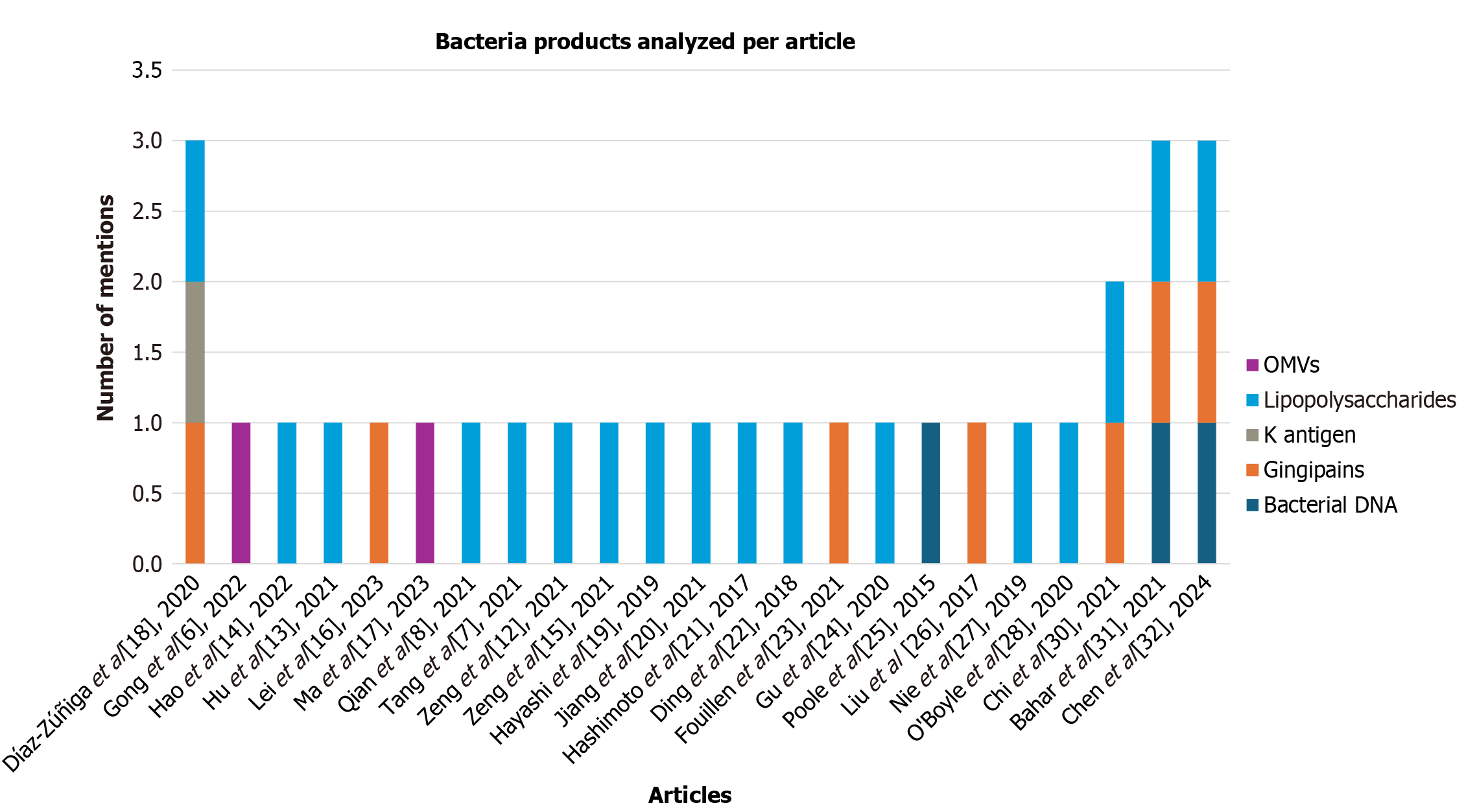

In this way, several bacterial products of P. gingivalis involved in the progression of Alzheimer's disease were identified (Figure 4). LPS are the most frequently reported components (54.84%), followed by gingipains (25.81%) and, to a lesser extent, by bacterial DNA, OMVs, and the K antigen (Figure 5). These products are associated with processes of immune activation, neuronal dysfunction, and neuroinflammation.

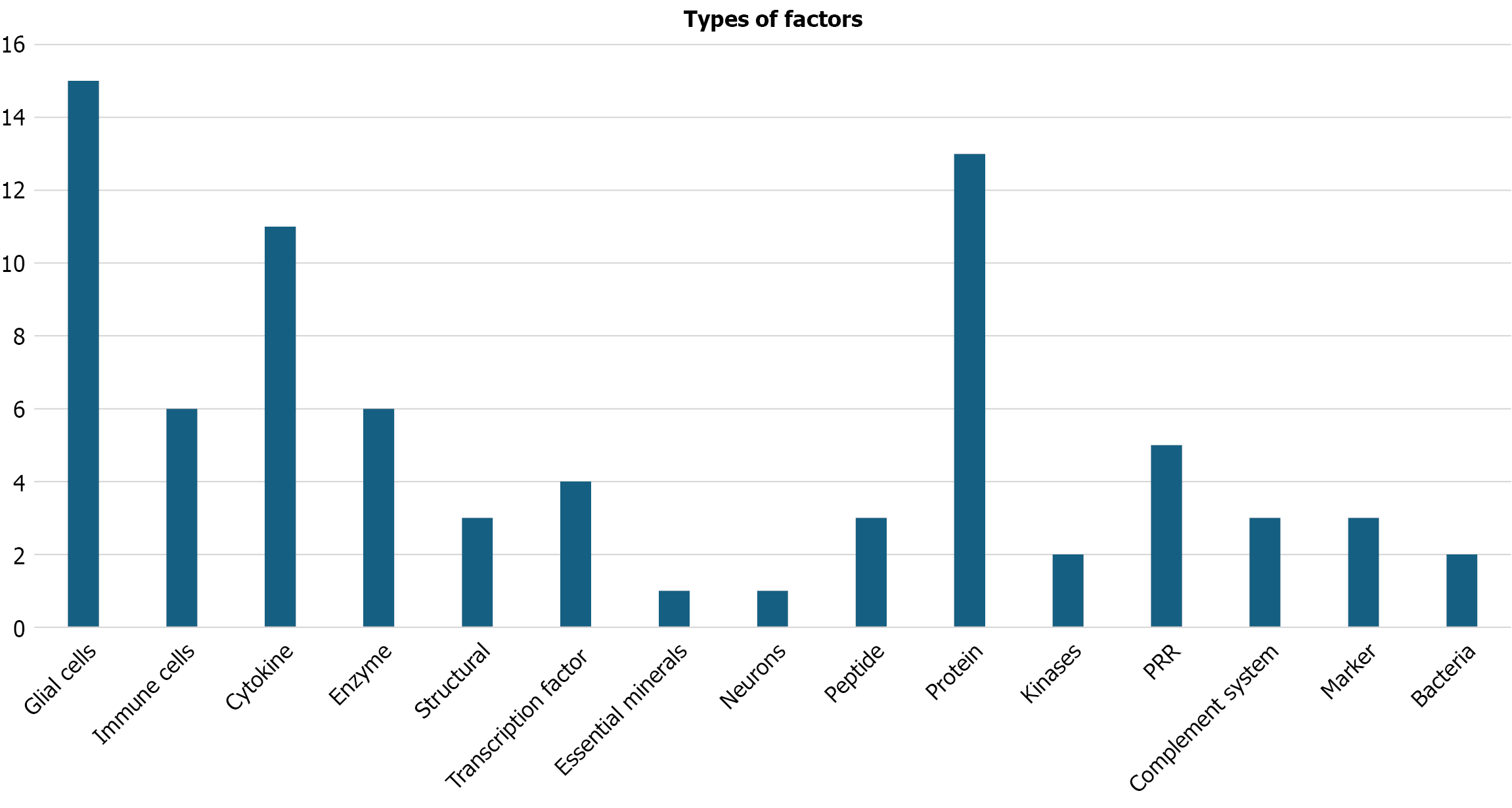

Regarding host factors, a total of 78 mentions were recorded, distributed in different functional categories (Table 2). The most frequent were glial cells, in particular microglia (9 mentions) and astrocytes (6 mentions), highlighting the central role of the neuroinflammatory response. Proinflammatory cytokines such as interleukin 1 beta (IL-1β) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) (3 mentions each) were also consistently implicated. Other relevant factors included enzymes such as BACE1 and iNOS, proteins related to Alzheimer's pathophysiology such as Cofilin-2, Tau, and amyloid precursor protein (APP), and receptors such as TLR2 and TLR4.

| Types of factors | Factors | Quantity |

| Glial cells | Astrocytes | 6 |

| Microglia | 9 | |

| Immune cells | Lymphocytes | 2 |

| Macrophages | 1 | |

| Monocytes | 1 | |

| Th1/Th17 | 1 | |

| Myeloid cells | 1 | |

| Cytokine | IL-1β | 3 |

| IL-6 | 2 | |

| Interleukins | 1 | |

| TGF-β1 | 1 | |

| TNF-α | 3 | |

| IL-17 | 1 | |

| Enzyme | ADAM10 | 1 |

| BACE1 | 1 | |

| CatB | 1 | |

| COX-2 | 1 | |

| NOS | 1 | |

| PP2A (phosphorylated/inactive) | 1 | |

| Structural | BBB | 1 |

| Circulatory system | 1 | |

| Brain | 1 | |

| Transcription factor | NF-κB | 2 |

| Nrf2/HO-1 | 1 | |

| STAT3 | 1 | |

| Essential minerals | Trace elements | 1 |

| Neurons | Trigeminal neurons | 1 |

| Peptide | Amyloid-β | 3 |

| Protein | Albumin | 1 |

| Caveolin1 | 1 | |

| Cofilina-2 | 1 | |

| GFAP | 1 | |

| MFSD2A | 1 | |

| Presenilin | 1 | |

| SCPPPQ1 | 1 | |

| Caveolar vesicles | 1 | |

| APP | 2 | |

| Tau | 1 | |

| CD36 | 1 | |

| CD204 | 1 | |

| Kinases | JAK2 | 1 |

| GSK3β | 1 | |

| PRR | TLR | 1 |

| TLR2 | 1 | |

| TLR4 | 2 | |

| TLR2 | 1 | |

| Complement system | C1q | 1 |

| C3 | 1 | |

| C5 | 1 | |

| Marker | CD3 | 1 |

| Iba-1 | 2 | |

| Bacteria | Lactobacillus sp. | 1 |

| Dysbiotic gut microbiota | 1 |

Figure 6 allows us to visualize the global distribution by type of host factor, with glial cells being the most mentioned group (15 references), followed by proteins (13) and cytokines (11). This diversity of factors reflects a multifactorial interaction between the pathogen and brain physiology, in which both immunological components and structural and metabolic processes participate.

Clearly influences the progression of Alzheimer’s disease. The virulence factors of this bacterium can accelerate the inflammation and neurodegeneration characteristics of this pathology. This is evident in the role of LPS, mentioned in 53.13% of the studies, as one of the factors with the greatest neuroinflammatory effect. This is attributed to their ability to activate TLR 2 and 4, which recognize pathogen-associated molecular patterns and, consequently, activate the immune response[12]. This activation induces the production of pro-inflammatory proteins such as the cytokines IL-1β and IL-6, which together accelerate the neuroinflammatory process[7].

LPS has also been shown to cause cognitive and memory impairment and contribute to the accumulation of Aβ through the immune response to P. gingivalis, forming extracellular plaques that promote neurotoxicity, neuronal death, synaptic dysfunction, and cognitive decline[13,14].

Another factor of great relevance is gingipains, proteases mentioned in 25% of the articles, which are capable of degrading host proteins. This occurs with complement system proteins C3 and C5, facilitating bacterial evasion of the immune system[15]. Like LPS, gingipains have been linked to neurodegeneration and the accumulation of beta-amyloid peptides.

In addition, gingipains activate glial cells, leading to neuroinflammation[16,17], and increase the permeability of the blood-brain barrier (BBB), allowing foreign substances to enter the brain.

Other factors, such as bacterial DNA (9.38% of mentions), OMVs (6.25%), and the K antigen (3.13%), also play an important role in the progression of the neurodegenerative disease. These elements can alter BBB permeability, trigger neuronal inflammation through overactivation of the immune system[18], and promote Tau protein hyperphosphorylation, leading to the formation of neurofibrillary tangles and cognitive impairment. However, these factors are less emphasized in the literature, either due to limited study or their possibly lower pathogenic relevance compared to the factors most frequently mentioned. Even so, studies such as those by Zeng et al[15], Díaz-Zúñiga et al[18], and Bahar et al[31] analyzed up to three bacterial factors, highlighting LPS and gingipains along with other components, such as bacterial DNA and the K antigen.

Another key point addressed was the analysis of host factors, focused on the metabolic reactions and immune responses observed in individuals infected with P. gingivalis. Overall, the studies analyzed a greater number of host factors compared to bacterial products, likely because Alzheimer’s disease is characterized by neuroinflammation mainly driven by the host immune response, involving numerous proteins and cellular components. Accordingly, a classification by type of factor was made, as shown in Table 2, where glial cells and proteins stand out with 15 and 13 mentions, respectively.

Microglia contribute to neuroinflammation, generating processes directly associated with Alzheimer’s disease, such as Tau hyperphosphorylation[7]. In addition, microglia promote astrocyte activation, leading to the production of inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6, and to the accumulation of Aβ. These factors trigger memory loss and hippocampal neurodegeneration[18].

Neuroinflammation also disrupts insulin signaling in the brain, reducing the levels of key proteins such as insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS-1) and phosphorylated Akt (p-Akt), which are essential for neuronal function and synaptic plasticity, thus contributing to disease progression[18]. Brain microglia also promote cell migration and inflammation. Activated astrocytes amplify the production of inflammatory cytokines, thereby worsening neuroinflammation and accelerating disease progression[13].

Among proteins, some stand out for their critical role. For example, the APP, whose abnormal fragmentation results in Aβ formation, accumulates in plaques that impair brain function and are a hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease[8]. Addi

Caveolin-1 mediates the formation of caveolae, small invaginations in the plasma membrane of BBB cells that facilitate the transport of substances, thereby increasing permeability[17]. MFSD2A, in contrast, has been shown to block or even reverse the BBB permeability induced by P. gingivalis products; however, during infection, its function is negatively affected. The Tau protein, as mentioned previously, when hyperphosphorylated, forms neurofibrillary tangles capable of causing neuronal dysfunction and cognitive impairment. We also find the proteins Caveolin1 and MFSD2A, involved in the permeability of the BBB.

The first is responsible for mediating the formation of caveola structures or invaginations of the plasma membrane of the BBB cells that allow the transport of substances, thus increasing permeability[16], the second, on the contrary, proved to be able to stop and even reverse the process of BBB permeabilization caused by P. gingivalis properties, so in the processes of infection by this bacterium it is negatively affected. The Tau protein, mentioned above, when hyperforylated forms neurofibrillary tangles, capable of causing neuronal dysfunction and cognitive impairment in models[33].

These findings suggest two possible avenues for future research: The products of P. gingivalis, such as LPS and gingipains, could be explored as both biomarkers and therapeutic targets in Alzheimer’s disease. A clear example is unfolded p53 (up53), a biomarker resulting from a conformational change in the p53 protein caused by oxidative stress induced by bacterial products like LPS, without genetic mutations. Up53 has been detected in peripheral cells and serum of Alzheimer’s patients even before clinical symptoms appear, making it a potential early marker. Another emerging biomarker is the presence of P. gingivalis DNA and gingipains in the brain and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of Alzheimer’s patients, which could contribute to early diagnosis. Regarding therapeutic targets, gingipains have been the focus of several studies; gingipain inhibitors, such as COR388, have shown promising results in animal models, reducing bacterial load and brain inflammation. Currently, COR388 is under investigation in ongoing preclinical and clinical trials to assess its efficacy in humans with Alzheimer’s disease[34,35].

Within the data analysis, a limitation is the focus on murine as the only study model, since it could not reflect the exact reality of the development of the disease in humans, in addition, the main routes of infection to the study murine were not taken into account, such as injection or ligation, where in the first case it directly injects the bacterium or bacterial infection factors to evaluate the effects, while in the second, the infection process was generated naturally including other factors in its progression, in the same way, age or mouse strain has not been considered, which could alter the predisposition to the development of the neurodegenerative disease and therefore have uneven results. Depending on the route of infection, the effects produced in the model and its immune responses could vary. A future analysis of how the route of infection influences patients is suggested to have a more complete view of the disease and how it acts in the body, as well as the reaction of the body to its presence and its history of predisposition to the disease.

In summary, the infection caused by P. gingivalis plays a fundamental role in the progression of Alzheimer's disease. The main products involved in neuroinflammation, cognitive decline, and activation of beta-amyloid plaques are LPS, mentioned in 53.13% of the analyzed articles, followed by gingipains at 25%. Other factors, such as OMVs, K antigen, among others, appear in less than 10% of the studies; however, they still contribute to microglial activation, which in turn activates astrocytes responsible for producing inflammatory cytokines, Aβ accumulation, Tau hyperphosphorylation, and BBB dysfunction, all of which favor cognitive deterioration and neuronal death.

Likewise, host factors were analyzed, focusing on the metabolic reactions and responses of mice infected with P. gingivalis. Glial cells and proteins stood out due to a greater emphasis on host factors over bacterial ones. In the case of glial cells, including microglia and astrocytes, they are involved in hippocampal neurodegeneration and cell death. On the other hand, proteins such as Caveolin-1, MFSD2A, Tau, and IRS-1, when altered by the pathogen, contribute to disease progression. Finally, certain limitations of the study were noted, such as the murine strains used and the route of infection, which could affect the immune responses to the infection.

This systematic review provides mounting evidence of a compelling association between P. gingivalis infection and the development of Alzheimer’s-like pathology in murine models. The bacterium’s virulence factors, particularly LPS and gingipains, appear to drive neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration through multiple pathways. These pathways include the activation of microglia and astrocytes, the increased production of proinflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β), and the promotion of pathological changes characteristic of Alzheimer’s disease, such as Aβ accumulation, tau hyperphosphorylation, and blood-brain barrier dysfunction. These effects correlate with measurable cognitive decline in animal studies, supporting the hypothesis that chronic periodontal infection contributes to Alzheimer’s disease progression.

Beyond providing mechanistic insights, P. gingivalis and its byproducts show promise as early diagnostic biomarkers. Bacterial DNA, gingipains, and associated host responses, such as misfolded p53, have been detected in CSF and peripheral tissues. This suggests that these factors could be used to identify individuals at risk for neurodegeneration before it becomes apparent. In terms of therapy, gingipain inhibitors such as COR388 have demonstrated efficacy in preclinical studies by reducing amyloid burden and neuroinflammation. However, questions remain about their specificity, pharmacokinetics, and long-term effects in humans.

Despite these advances, there are still critical limitations that must be acknowledged. Most studies rely exclusively on murine models and exhibit significant variability in experimental design, including differences in bacterial strains, infection routes, and mouse genetics. Additionally, common methodological shortcomings, such as a lack of randomization, blinding, and adequate sample sizes, undermine the robustness of some findings. Future research should prioritize standardized protocols to enhance reproducibility and better assess the translational relevance of these discoveries.

In conclusion, the growing body of evidence suggests that P. gingivalis is a potential modifiable risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease. Integrating oral health into broader neurodegenerative disease prevention strategies, alongside targeted antimicrobial therapies, could open new avenues for intervention. However, it is unclear whether this relationship reflects direct causation or synergistic interactions with other risk factors. Longitudinal human studies and well-controlled preclinical research are essential to determining whether eliminating P. gingivalis alters the disease's trajectory. This research offers hope for novel approaches to mitigating this devastating condition.

| 1. | Dominguez-Gortaire J, Ruiz A, Porto-Pazos AB, Rodriguez-Yanez S, Cedron F. Alzheimer's Disease: Exploring Pathophysiological Hypotheses and the Role of Machine Learning in Drug Discovery. Int J Mol Sci. 2025;26:1004. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Rostagno AA. Pathogenesis of Alzheimer's Disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;24:107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 204] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Sarmiento-Ordóñez JM, Brito-Samaniego DR, Vásquez-Palacios AC, Pacheco-Quito EM. Association Between Porphyromonas gingivalis and Alzheimer's Disease: A Comprehensive Review. Infect Drug Resist. 2025;18:2119-2136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Fu Y, Xu X, Zhang Y, Yue P, Fan Y, Liu M, Chen J, Liu A, Zhang X, Bao F. Oral Porphyromonas gingivalis Infections Increase the Risk of Alzheimer's Disease: A Review. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2023;21:7-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Owoyele PV, Malekzadeh S. Porphyromonas gingivalis, neuroinflammation and Alzheimer's disease. Niger J Physiol Sci. 2022;37:157-164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Gong T, Chen Q, Mao H, Zhang Y, Ren H, Xu M, Chen H, Yang D. Outer membrane vesicles of Porphyromonas gingivalis trigger NLRP3 inflammasome and induce neuroinflammation, tau phosphorylation, and memory dysfunction in mice. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022;12:925435. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 21.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Tang Z, Liang D, Cheng M, Su X, Liu R, Zhang Y, Wu H. Effects of Porphyromonas gingivalis and Its Underlying Mechanisms on Alzheimer-Like Tau Hyperphosphorylation in Sprague-Dawley Rats. J Mol Neurosci. 2021;71:89-100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Qian X, Zhang S, Duan L, Yang F, Zhang K, Yan F, Ge S. Periodontitis Deteriorates Cognitive Function and Impairs Neurons and Glia in a Mouse Model of Alzheimer's Disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2021;79:1785-1800. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, Moher D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44932] [Cited by in RCA: 51476] [Article Influence: 10295.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 10. | Hooijmans CR, Rovers MM, de Vries RB, Leenaars M, Ritskes-Hoitinga M, Langendam MW. SYRCLE's risk of bias tool for animal studies. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14:43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2511] [Cited by in RCA: 2868] [Article Influence: 239.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 11. | Ide M, Harris M, Stevens A, Sussams R, Hopkins V, Culliford D, Fuller J, Ibbett P, Raybould R, Thomas R, Puenter U, Teeling J, Perry VH, Holmes C. Periodontitis and Cognitive Decline in Alzheimer's Disease. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0151081. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 185] [Cited by in RCA: 303] [Article Influence: 30.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Zeng Q, Fang Q, Zhou X, Yang H, Dou Y, Zhang W, Gong P, Rong X. Cofilin 2 Acts as an Inflammatory Linker Between Chronic Periodontitis and Alzheimer's Disease in Amyloid Precursor Protein/Presenilin 1 Mice. Front Mol Neurosci. 2021;14:728184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Hu Y, Zhang X, Zhang J, Xia X, Li H, Qiu C, Liao Y, Chen H, He Z, Song Z, Zhou W. Activated STAT3 signaling pathway by ligature-induced periodontitis could contribute to neuroinflammation and cognitive impairment in rats. J Neuroinflammation. 2021;18:80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Hao X, Li Z, Li W, Katz J, Michalek SM, Barnum SR, Pozzo-Miller L, Saito T, Saido TC, Wang Q, Roberson ED, Zhang P. Periodontal Infection Aggravates C1q-Mediated Microglial Activation and Synapse Pruning in Alzheimer's Mice. Front Immunol. 2022;13:816640. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Zeng F, Liu Y, Huang W, Qing H, Kadowaki T, Kashiwazaki H, Ni J, Wu Z. Receptor for advanced glycation end products up-regulation in cerebral endothelial cells mediates cerebrovascular-related amyloid β accumulation after Porphyromonas gingivalis infection. J Neurochem. 2021;158:724-736. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Lei S, Li J, Yu J, Li F, Pan Y, Chen X, Ma C, Zhao W, Tang X. Porphyromonas gingivalis bacteremia increases the permeability of the blood-brain barrier via the Mfsd2a/Caveolin-1 mediated transcytosis pathway. Int J Oral Sci. 2023;15:3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 22.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Ma X, Shin YJ, Yoo JW, Park HS, Kim DH. Extracellular vesicles derived from Porphyromonas gingivalis induce trigeminal nerve-mediated cognitive impairment. J Adv Res. 2023;54:293-303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 18.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Díaz-Zúñiga J, More J, Melgar-Rodríguez S, Jiménez-Unión M, Villalobos-Orchard F, Muñoz-Manríquez C, Monasterio G, Valdés JL, Vernal R, Paula-Lima A. Alzheimer's Disease-Like Pathology Triggered by Porphyromonas gingivalis in Wild Type Rats Is Serotype Dependent. Front Immunol. 2020;11:588036. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Hayashi K, Hasegawa Y, Takemoto Y, Cao C, Takeya H, Komohara Y, Mukasa A, Kim-Mitsuyama S. Continuous intracerebroventricular injection of Porphyromonas gingivalis lipopolysaccharide induces systemic organ dysfunction in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Exp Gerontol. 2019;120:1-5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Jiang M, Zhang X, Yan X, Mizutani S, Kashiwazaki H, Ni J, Wu Z. GSK3β is involved in promoting Alzheimer's disease pathologies following chronic systemic exposure to Porphyromonas gingivalis lipopolysaccharide in amyloid precursor protein(NL-F/NL-F) knock-in mice. Brain Behav Immun. 2021;98:1-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Hashimoto R, Kakigi R, Nakamura K, Itoh S, Daida H, Okada T, Katoh Y. LPS enhances expression of CD204 through the MAPK/ERK pathway in murine bone marrow macrophages. Atherosclerosis. 2017;266:167-175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Ding Y, Ren J, Yu H, Yu W, Zhou Y. Porphyromonas gingivalis, a periodontitis causing bacterium, induces memory impairment and age-dependent neuroinflammation in mice. Immun Ageing. 2018;15:6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Fouillen A, Mary C, Ponce KJ, Moffatt P, Nanci A. A proline rich protein from the gingival seal around teeth exhibits antimicrobial properties against Porphyromonas gingivalis. Sci Rep. 2021;11:2353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Gu Y, Wu Z, Zeng F, Jiang M, Teeling JL, Ni J, Takahashi I. Systemic Exposure to Lipopolysaccharide from Porphyromonas gingivalis Induces Bone Loss-Correlated Alzheimer's Disease-Like Pathologies in Middle-Aged Mice. J Alzheimers Dis. 2020;78:61-74. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Poole S, Singhrao SK, Chukkapalli S, Rivera M, Velsko I, Kesavalu L, Crean S. Active invasion of Porphyromonas gingivalis and infection-induced complement activation in ApoE-/- mice brains. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;43:67-80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 159] [Article Influence: 15.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Liu Y, Wu Z, Nakanishi Y, Ni J, Hayashi Y, Takayama F, Zhou Y, Kadowaki T, Nakanishi H. Infection of microglia with Porphyromonas gingivalis promotes cell migration and an inflammatory response through the gingipain-mediated activation of protease-activated receptor-2 in mice. Sci Rep. 2017;7:11759. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Nie R, Wu Z, Ni J, Zeng F, Yu W, Zhang Y, Kadowaki T, Kashiwazaki H, Teeling JL, Zhou Y. Porphyromonas gingivalis Infection Induces Amyloid-β Accumulation in Monocytes/Macrophages. J Alzheimers Dis. 2019;72:479-494. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | O'Boyle C, Haley MJ, Lemarchand E, Smith CJ, Allan SM, Konkel JE, Lawrence CB. Ligature-induced periodontitis induces systemic inflammation but does not alter acute outcome after stroke in mice. Int J Stroke. 2020;15:175-187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Kazemi N, Khorasgani MR, Noorbakhshnia M, Razavi SM, Narimani T, Naghsh N. Protective effects of a lactobacilli mixture against Alzheimer's disease-like pathology triggered by Porphyromonas gingivalis. Sci Rep. 2024;14:27283. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Chi L, Cheng X, Lin L, Yang T, Sun J, Feng Y, Liang F, Pei Z, Teng W. Porphyromonas gingivalis-Induced Cognitive Impairment Is Associated With Gut Dysbiosis, Neuroinflammation, and Glymphatic Dysfunction. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2021;11:755925. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Bahar B, Kanagasingam S, Tambuwala MM, Aljabali AAA, Dillon SA, Doaei S, Welbury R, Chukkapalli SS, Singhrao SK. Porphyromonas gingivalis (W83) Infection Induces Alzheimer's Disease-Like Pathophysiology in Obese and Diabetic Mice. J Alzheimers Dis. 2021;82:1259-1275. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Chen S, Han C, Wang X, Zhang Q, Yang X. Alantolactone improves cognitive impairment in rats with Porphyromonas gingivalis infection by inhibiting neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, and reducing Aβ levels. Brain Res. 2024;1845:149203. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Jiang C, Yang D, Hua T, Hua Z, Kong W, Shi Y. A PorX/PorY and σ(P) Feedforward Regulatory Loop Controls Gene Expression Essential for Porphyromonas gingivalis Virulence. mSphere. 2021;6:e0042821. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | French PW. Unfolded p53 in non-neuronal cells supports bacterial etiology of Alzheimer's disease. Neural Regen Res. 2022;17:2619-2622. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Dominy SS, Lynch C, Ermini F, Benedyk M, Marczyk A, Konradi A, Nguyen M, Haditsch U, Raha D, Griffin C, Holsinger LJ, Arastu-Kapur S, Kaba S, Lee A, Ryder MI, Potempa B, Mydel P, Hellvard A, Adamowicz K, Hasturk H, Walker GD, Reynolds EC, Faull RLM, Curtis MA, Dragunow M, Potempa J. Porphyromonas gingivalis in Alzheimer's disease brains: Evidence for disease causation and treatment with small-molecule inhibitors. Sci Adv. 2019;5:eaau3333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 882] [Cited by in RCA: 1360] [Article Influence: 194.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/