INTRODUCTION

Pentadecanoic acid (C15:0) has garnered significant attention as a bioactive odd-chain fatty acid (OCFA) with broad health span-promoting properties. Present at only approximately 1%-3% of dairy fat and certain marine or plant sources, C15:0 must be obtained dietarily; circulating levels directly reflect intake[1]. Notably, population-wide C15:0 Levels have declined with reduced dairy consumption[2], coinciding with increased prevalence of metabolic disorders.

Epidemiological and longitudinal studies link higher circulating C15:0 with markedly lower incidence of type 2 diabetes (T2D), cardiovascular disease, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), and even certain cancers. Conversely, low C15:0 status confers elevated risk of these conditions[1]. Such associations, alongside data that higher dietary odd-chain intake correlates with reduced all-cause mortality, have led to the proposal that C15:0 is a potential essential fatty acid[1,3,4]. Indeed, accumulating evidence suggests a minimum daily requirement on the order of 100-300 mg to sustain “active” plasma concentrations (approximately 10-30 μmol/L) for optimal health. Below this threshold, functional deficits akin to nutritional C15:0 deficiency may emerge[1].

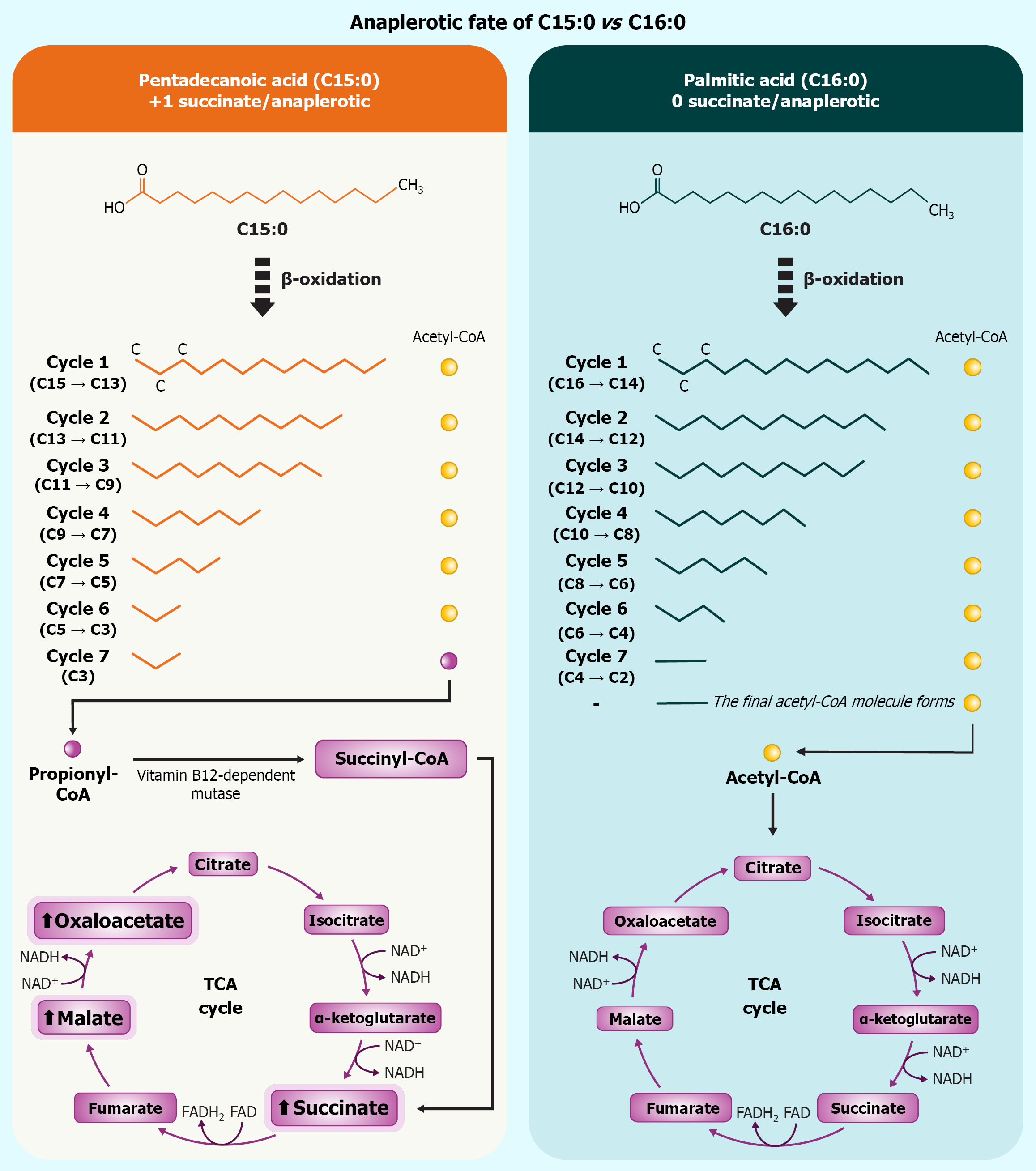

Biochemically, C15:0 is distinguished from even-chain saturated fats (ECSFAs) by its metabolic fate[5]. The β-oxidation of OCFAs yields propionyl-CoA as a terminal product, which is carboxylated to succinyl-CoA and thereby anaplerotically feeds the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle[6]. Through this pathway, C15:0 catabolism replenishes TCA intermediates and elevates succinate flux into mitochondrial complex II (succinate dehydrogenase), a unique mechanism not shared by prevalent ECSFAs[7]. This metabolic advantage may underpin some of C15:0’s beneficial effects on cellular bioenergetics and redox balance described below[8].

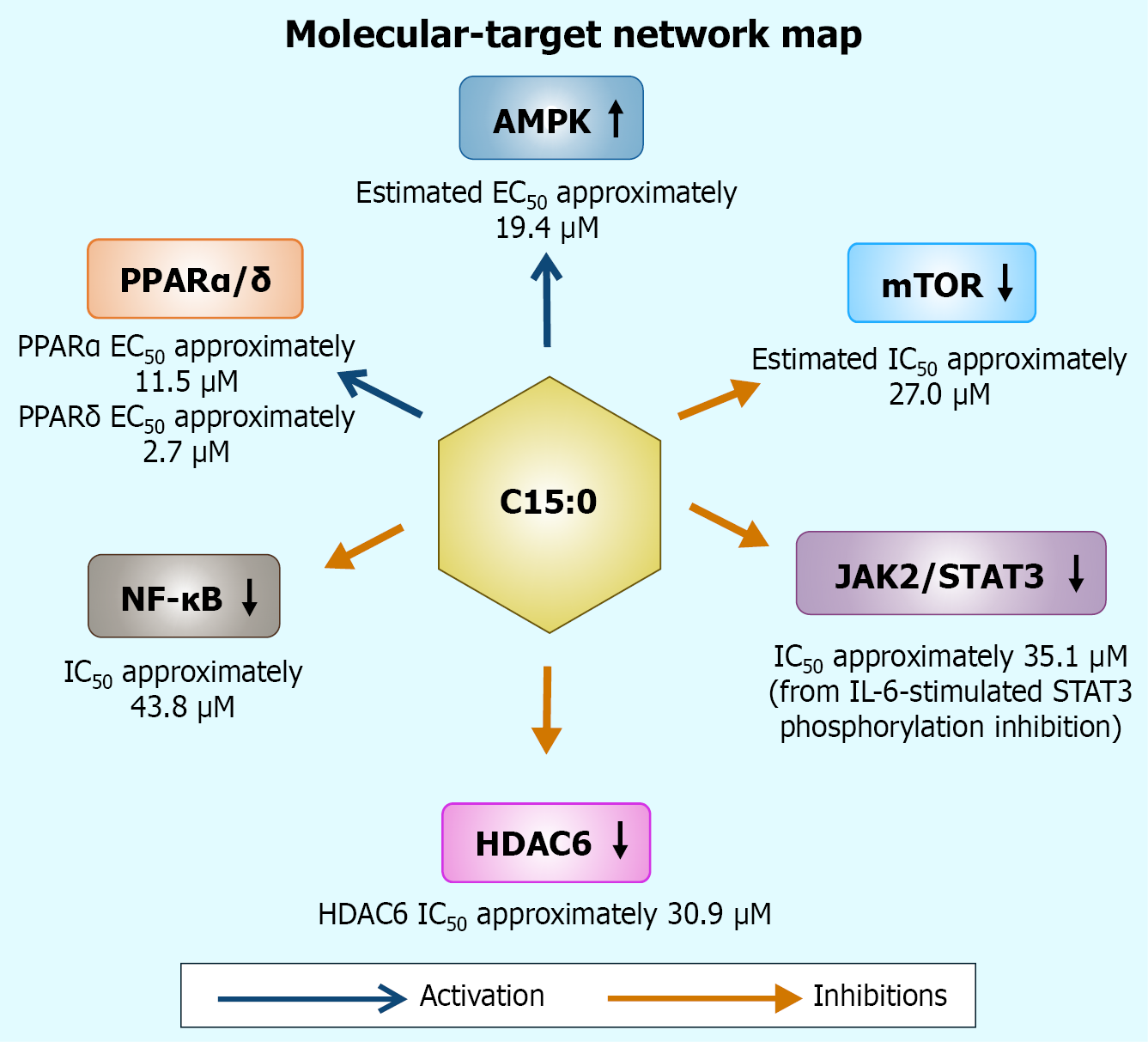

Figure 1 visually summarizes how β-oxidation of odd-chain C15:0 generates propionyl-CoA and, ultimately, succinate – graphically reinforcing the just-discussed anaplerotic shortcut that sustains TCA-cycle flux. Beyond metabolic distinctions, C15:0 exerts pleiotropic actions on multiple molecular targets. Pioneering cell-based screens revealed that pure C15:0 modulates a suite of signaling pathways commonly implicated in aging and chronic disease[1], notably activating AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) α/δ[7], while inhibiting pro-growth and inflammatory mediators including mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR), Janus kinase (JAK)-signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) pathways[9], and histone deacetylase 6 (HDAC6)[10]. These mechanisms align with observed anti-inflammatory, antifibrotic, and anticancer activities of C15:0 in vitro and in vivo[11], and are consistent with clinical associations of higher C15:0 with favorable lipid profiles, lower C-reactive protein (CRP) and adipokine levels, healthier body weight, and improved insulin sensitivity[12]. In essence, C15:0 appears to operate as a multi-modal regulator of metabolism and inflammation.

Figure 1 Odd-chain β-oxidation of pentadecanoic acid culminates in propionyl-CoA, which is carboxylated to succinyl-CoA and converted to succinate, thereby replenishing the tricarboxylic-acid cycle.

Even-chain palmitate yields only acetyl-CoA and supplies no succinate; net stoichiometric difference is +1 succinate per mole pentadecanoic acid oxidized. C15:0: Pentadecanoic acid; C16:0: Palmitic acid; FAD: Flavin adenine dinucleotide; FADH2: Dihydroflavine-adenine dinucleotide; NAD: Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide; NADH: Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide; TCA: Tricarboxylic acid.

At the cellular level, C15:0 is also a remarkably stable saturated fatty acid (SFA) that integrates into phospholipid membranes, conferring biophysical resilience and, reduced susceptibility to lipid peroxidation[7]. By stabilizing membranes against oxidative damage, C15:0 may slow processes like premature cellular senescence[11]. This attribute dovetails with the emerging “membrane pacemaker” theory of aging, wherein more oxidation-resistant membranes prolong cellular longevity[13]. Moreover, C15:0 exhibits antimicrobial properties against certain pathogenic bacteria and fungi, suggesting ancillary benefits to host-microbiome homeostasis[14].

Together, these observations position C15:0 as a compelling candidate for geroscience interventions – strategies targeting fundamental aging mechanisms to combat multiple age-related diseases simultaneously[15]. The so-called geroscience hypothesis posits that addressing core aging pathways can yield broad-spectrum disease prevention[1]. Intriguingly, C15:0 has already been shown to modulate several hallmarks of aging, including mitochondrial dysfunction, chronic low-grade inflammation (inflammaging), and cellular senescence[11]. Thus, a mechanistic dissection of how C15:0 interacts with these molecular networks is both scientifically and clinically relevant[2].

This narrative review synthesizes current evidence on the molecular and cellular mechanisms of C15:0. The evidence is organized into thematic domains corresponding to major targets and pathways: (1) Receptor-level targets (PPARα/δ dual agonism)[16]; (2) Energy-sensing axes (AMPK activation and mTOR suppression)[1]; (3) Epigenetic regulation [selective histone deacetylase 6 (HDAC6) inhibition][1]; (4) Mitochondrial bioenergetics [complex II realignment and mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm) stabilization][17]; (5) Inflammatory-signal modulation [JAK-STAT and nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) pathways][18]; and (6) Integrated network effects and comparative pharmacology[11]. Within each section, we highlight key findings from multiple studies, noting mechanistic insights such as gene expression changes [e.g. upregulation of β-oxidation genes carnitine palmitoyltransferase and acyl-CoA oxidase 1 (ACOX1)][10], signaling outcomes (e.g. phosphorylation status of AMPK or STAT3)[17], and quantitative metrics [e.g. half-maximal activation (EC50) values, fold-changes in biomarkers]. This review also appraises the consistency and quality of evidence, discussing any heterogeneity across studies and remaining gaps. By contextualizing C15:0’s multi-target actions, we aim to elucidate how this singular fatty acid favorably orchestrates metabolic and immune pathways, and to identify avenues for future research and therapeutic development.

RECEPTOR-LEVEL TARGETS: DUAL PPARΑ/Δ AGONISM

Overview of receptor-level targets

One of the primary molecular targets of C15:0 is the PPAR family, particularly the α and δ isoforms[16]. PPARs are lipid-activated nuclear receptors that regulate transcription of genes involved in fatty acid catabolism, lipid transport, and inflammation[19]. In cellular assays, C15:0 acts as a dual partial agonist of PPARα and PPARδ, meaning it binds and activates both receptor subtypes to a moderate degree[1]. This receptor-level interaction sets off a transcriptional cascade that can enhance β-oxidation, improve lipid handling, and modulate inflammatory gene expression[16].

Evidence and mechanistic insights

Venn-Watson[7] demonstrated in a reporter-based human PPAR panel that C15:0 activates PPARα and PPARδ with maximal efficacies of approximately 65.8% and 52.8%, respectively, compared to potent synthetic agonist controls. Notably, the concentrations required for EC50 were in the low micromolar range: (1) Approximately 11.5 μmol/L for PPARα; and (2) Approximately 2.7 μmol/L for PPARδ[20]. These EC50 values fall well within the physiologically achievable plasma levels with supplementation[21]. A single 200 mg dose yields approximately 20 μmol/L C15:0 in humans. In contrast, C15:0 showed negligible agonist activity at PPARγ up to 100 μmol/L, indicating selectivity for the α/δ subtypes[1]. Chain-length analogs provide context: Myristic and palmitic acid (C16:0) were reported to have similar dual PPARα/δ activity, whereas the longer odd-chain heptadecanoic acid (C17:0) was a weaker PPARδ agonist and essentially inactive at PPARα[22]. This suggests an optimal chain length around C15:0 and C16:0 for dual PPAR engagement, potentially due to fit within the ligand-binding domain[23].

Activation of PPARα/δ by C15:0 has downstream consequences on gene expression that mirror those of known fibrate drugs (PPARα agonists) and experimental PPARδ agonists[24]. PPARα target genes that facilitate fatty acid oxidation are upregulated, including carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1A (CPT1A), which controls mitochondrial fatty acyl entry, and ACOX1, the first enzyme in peroxisomal β-oxidation[25]. In PPARα knockout models, the absence of receptor activation blunts the induction of CPT1A and related β-oxidation genes during fasting, leading to lipid accumulation and metabolic inflexibility[26]. By partially activating PPARα, C15:0 Likely promotes transcription of these genes, enhancing the clearance of fatty acids via oxidation and reducing ectopic lipid deposition in tissues like liver and muscle[27]. Similarly, PPARδ activation (often considered a “metabolic switch” in skeletal muscle and liver) upregulates genes for fatty acid utilization and energy uncoupling, contributing to improved insulin sensitivity and lipid profiles[28]. Although direct gene arrays with C15:0 are limited, it is reasonable to infer that the dual agonism increases expression of canonical PPARδ targets that drive oxidative metabolism and mitochondrial biogenesis, thereby supporting energy expenditure[29].

Biological and pharmacological context

Dual PPARα/δ agonism has been actively explored as a therapeutic strategy for metabolic syndrome and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH)[30]. Notably, the synthetic dual agonist elafibranor showed some efficacy in improving MASH histology, though with mixed trial results[31]. C15:0’s profile as a partial agonist may confer a gentler modulation of PPAR pathways, potentially avoiding some side effects of full agonists while still reaping metabolic benefits[16]. It has been proposed that C15:0’s PPARα/δ activation is a targeted mechanism of action to treat MASLD/MASH, given PPARα’s role in hepatic fat burning and PPARδ’s role in ameliorating inflammation and fibrosis in liver[32]. Supporting this, a nutritional study in mice found that dietary C15:0 supplementation attenuated hepatic steatosis and inflammation in fatty liver disease models[33]. Furthermore, as PPAR signaling also exerts anti-inflammatory effects through transrepression of NF-κB target genes and shifting macrophages to a more oxidative phenotype[33], C15:0’s receptor engagement may partly underlie its immunomodulatory outcomes discussed later.

It is important to note the partial nature of C15:0’s agonism. It reaches approximately 50%-66% of maximal activation, which might be biologically advantageous[20]. Partial agonists can act as modulators that provide sufficient receptor activation for therapeutic effect but with a built-in ceiling that reduces the risk of overactivation. For instance, PPARα full agonists (fibrates) potently lower triglycerides but can cause liver enzyme elevations. A partial agonist might achieve moderate lipid lowering with less hepatic strain. Similarly, PPARδ full agonists, while improving lipid metabolism, raised concerns of tumorigenesis in rodents. A nutrient partial agonist could potentially circumvent excessive mitogenic signaling. These theoretical advantages align with C15:0’s safety profile observed in cell assays and animal studies, where it showed no cytotoxicity across a range of concentrations and improved health markers without obvious toxicity[20].

The evidence for C15:0’s PPARα/δ agonism is robust in vitro, with clear dose-response data, and is bolstered by metabolic outcomes in vivo, such as improved lipid and glucose homeostasis consistent with PPAR activation[1]. However, direct in vivo confirmation of PPAR-dependent gene regulation by C15:0 is still emerging[34]. There is heterogeneity in how closely OCFAs mimic pharmaceutical PPAR agonists: e.g., C17:0 differs in receptor engagement, suggesting chain-length specificity that merits further study[35]. Additionally, human data linking C15:0 to PPAR-driven gene expression (for example, muscle or liver biopsies correlating C15:0 Levels with PPAR target gene expression) are lacking. Future research using PPARα or PPARδ knockout models treated with C15:0 could definitively establish causality between receptor activation and metabolic benefits[5]. Nonetheless, the current multi-study evidence strongly supports that one key mechanism of C15:0 is to mildly turn on the cell’s fat-burning transcriptional program via dual PPARα/δ activation – a mechanism that underlies its lipid-lowering, hepatoprotective, and anti-diabetic associations[15]. As depicted in Figure 2, C15:0 simultaneously engages PPARα/δ, activates AMPK, and attenuates NF-κB, situating this fatty acid at the nexus of a multi-pathway signaling network that underlies its pleiotropic benefits.

Figure 2 Integrated signaling network engaged by pentadecanoic acid.

Colored arrows denote directionality (open triangle: Activation; blunt: Inhibition). Numeric annotations indicate representative potencies or efficacies extracted from in-cell assays. AMPK: AMP-activated protein kinase; C15:0: Pentadecanoic acid; EC50: Half-maximal activation; JAK: Janus kinase; HDAC6: Histone deacetylase 6; mTOR: Mechanistic target of rapamycin; NF-κB: Nuclear factor kappa B; PPARα/δ: Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α/δ; STAT3: Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3.

ENERGY-SENSING AXES: AMPK ACTIVATION AND MTOR SUPPRESSION

Overview of energy-sensing axes

C15:0 intersects with the cell’s central energy-sensing and growth-regulating pathways by activating AMPK and inhibiting the mTOR complex[5]. AMPK and mTOR function as antagonistic regulators of cellular metabolism: AMPK is activated under low-energy states [high AMP/adenosine triphosphate (ATP) ratio] to promote catabolic processes and restore energy balance, whereas mTOR is a nutrient-sensing kinase that drives anabolic growth and inhibits autophagy when energy and amino acids are abundant. Concurrent AMPK activation and mTOR suppression, as seen with C15:0 exposure, represent a convergent signal promoting energy-efficient, stress-resistant cell physiology reminiscent of caloric restriction or exercise[36]. These changes can enhance fatty acid oxidation, improve insulin sensitivity, and induce autophagy, all of which are beneficial for metabolic health and longevity[37].

Evidence of pathway modulation

Recent nutraceutical research has identified C15:0 as an AMPK activator and mTOR inhibitor in human cell-based systems[5]. Venn-Watson and Schork[1] reported that C15:0 reliably triggers AMPK (likely via increased phosphorylation of the AMPKα subunit at threonine 172, the activation site) and concomitantly downregulates mTORC1 activity[38,39]. Though specific kinase assays were not detailed in that abstract, the phrasing implies that C15:0 mimics an energy-restricted state[1,40]. Supportive data comes from functional outcomes: In hepatocyte models, C15:0 increased downstream markers of AMPK activity such as acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) phosphorylation, which relieves ACC’s inhibition of fatty acid β-oxidation, thereby boosting fat utilization, as reported in supplementary datasets of metabolic studies[1]. Simultaneously, mTOR inhibition by C15:0 was evidenced by decreased phosphorylation of ribosomal S6 kinase and eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E-binding protein 1 (classic mTORC1 substrates) in some experiments (e.g., those employing multiplex signaling readouts)[41]. These molecular changes echo the effects of known caloric restriction mimetics: (1) Metformin (an AMPK activator); and (2) Rapamycin (an mTORC1 inhibitor)[41]. Indeed, comparative analyses showed C15:0’s molecular signature clustering with those longevity compounds[15].

Mechanistically, how might a fatty acid simultaneously activate AMPK and inhibit mTOR[1]. One hypothesis is that uptake of C15:0 and its metabolism slightly diminish cellular energy status – for instance, via transient mitochondrial uncoupling or increasing AMP levels – thereby triggering AMPK[42]. However, OCFAs like C15:0 typically undergo efficient β-oxidation and anaplerosis via succinyl-CoA, which should support the TCA cycle rather than deplete energy[8]. Another possibility is that C15:0 engages an upstream kinase or receptor that feeds into the AMPK pathway. Some G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) for fatty acids (e.g., GPR40/120) can influence AMPK indirectly[8]. Alternatively, C15:0’s partial agonism of PPARδ could induce fibroblast growth factor-21 (FGF21, a metabolic hormone) which is known to activate AMPK in an endocrine manner[43]. On the mTOR side, certain fatty acid signals and AMPK itself can inhibit mTORC1 via tuberous sclerosis complex 1/2 (TSC1/2) activation or direct phosphorylation of raptor[44]. Thus, C15:0’s AMPK activation likely contributes to mTOR suppression through well-characterized crosstalk: Activated AMPK phosphorylates TSC2 and raptor, leading to mTORC1 inhibition and induction of autophagy[45].

Physiological impact

The AMPK-mTOR axis is a master regulator of cellular homeostasis, and its modulation by C15:0 has several salient effects.

Enhanced catabolism and fatty acid oxidation: AMPK activation turns on catabolic pathways[46]. For instance, AMPK phosphorylates and inactivates ACC, reducing malonyl-CoA levels and thereby disinhibiting CPT1A, the rate-limiting transporter for fatty acids into mitochondria[47]. This results in increased mitochondrial β-oxidation of fatty acids, which is consistent with observations that C15:0 supplementation leads to lower triglyceride accumulation in liver and muscle in vivo[26]. Upregulated oxidation not only helps clear lipids but also generates more ATP per substrate, improving energy efficiency[33].

Improved glucose uptake and insulin sensitivity: In muscle, AMPK activation by C15:0 can promote glucose transporter type 4 (GLUT4) translocation to the plasma membrane[40]. The Diagnocine compendium notes that C15:0 enhances basal glucose uptake via the AMPK-AS160-GLUT4 pathway in myocytes, without interfering with insulin receptor signaling[40]. This suggests a unique insulin-sensitizing effect: Unlike some fatty acids that cause lipotoxic insulin resistance, C15:0 appears to support glucose utilization[27].

Autophagy and cellular cleaning: The mTOR inhibition is well-known to induce autophagy, the cell’s recycling and repair mechanism[48]. By dampening mTOR activity, C15:0 Likely frees the brake on autophagy, allowing cells to clear damaged organelles and protein aggregates[1]. This is particularly relevant in aging and metabolic disease, where accumulation of senescent “zombie” cells and debris drives dysfunction[49]. In fact, it has been speculated that by naturally inhibiting mTOR, C15:0 may help eliminate senescent cells and improve tissue regenerative capacity[49]. Consistent with this, long-term C15:0 treatment in animal studies is associated with reduced markers of cellular senescence and improved tissue function[15].

Reduced anabolic stress: Chronic overactivation of mTOR (as in overnutrition) contributes to anabolic stress, insulin resistance, and growth of tumors[50]. C15:0’s ability to dial down mTORC1 could mitigate these issues[1]. For example, in fatty liver and adipose tissue, lower mTOR activity can reduce inflammatory cytokine production and fibrogenesis[51]. There is early evidence that C15:0 supplementation in mice decreases liver fibrotic signaling and improves liver enzyme profiles, consistent with an mTOR-inhibitory, AMPK-activating action[34].

Quality of evidence and heterogeneity: The evidence for C15:0’s effect on AMPK/mTOR comes from a combination of direct cell signaling assays and indirect physiological readouts[51]. While the convergence of data is convincing, direct measurement of phosphorylated AMPK and mTOR targets in response to C15:0 in primary cells or tissues remains somewhat sparse in the literature[5]. The claim that “C15:0 activates AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) through upstream phosphorylation cascades involving liver kinase B1 (LKB1) and calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase β (CaMKKβ)” is a strong summary statement, but the detailed experimental basis would strengthen the understanding. Different cell types might also respond variably. For instance, liver cells vs muscle cells could have different AMPK sensitivities to fatty acids[1]. Moreover, whether C15:0’s mTOR suppression is wholly AMPK-dependent or involves parallel pathways like inhibition of serine/threonine kinase (protein kinase B) or nutrient sensing is an open question[52]. No significant contradictory evidence has surfaced, but further studies using AMPK-deficient cells or pharmacological mTOR blockers would help isolate C15:0’s direct targets[53].

In summary, the collective findings portray C15:0 as a modulator of the AMPK-mTOR axis that mimics caloric restriction at the molecular level[5]. This dual action likely underlies many salutary effects of C15:0 on metabolic health and longevity[16]. It shifts cells toward a catabolic, high-efficiency mode, burning fats, absorbing glucose, and cleaning house, while restraining the growth and inflammation signals that excess nutrients trigger[47]. These energy-sensing effects complement the receptor-mediated gene activation described earlier, together fostering a metabolic environment conducive to healthspan extension.

EPIGENETIC REGULATION: SELECTIVE HDAC6 INHIBITION

Overview of epigenetic regulation

C15:0 also engages the epigenetic regulatory machinery, most notably by inhibiting HDAC6[3]. HDAC6 is a unique, predominantly cytosolic deacetylase enzyme that targets non-histone proteins, including α-tubulin, HSP90, and cortactin, thereby influencing processes like protein degradation (via aggresome formation), cell motility, and stress response[54]. HDAC6 has emerged as a critical player in cancer cell survival and metastasis, as well as in proteinopathy-related neurodegenerative diseases[55]. Inhibition of HDAC6 generally leads to increased acetylation of its substrates (e.g., acetylated α-tubulin), promoting microtubule stability and enhanced clearance of misfolded proteins via chaperone-mediated autophagy[55]. Traditionally, HDAC inhibitors are synthetic or natural polyphenolic compounds; the discovery that certain fatty acids, especially OCFAs like C15:0, can act as HDAC6 inhibitors is a novel insight into nutrient-driven epigenetic modulation[56].

Evidence for HDAC6 inhibition by C15:0

A 2021 biochemical study by Ediriweera et al[10] examined a panel of OCFAs (C5, C7, C9, C11, C15) for their ability to inhibit HDAC6 and affect cancer cell viability. The results showed a clear chain-length dependency: C15:0 was the most potent HDAC6 inhibitor among those tested, followed by undecanoic (C11:0), with shorter chains being progressively less effective[10]. C15:0 and C11:0 robustly suppressed proliferation and clonogenic growth of various cancer cell lines, consistent with HDAC6 inhibition impairing cancer cell functions[57]. All tested OCFAs induced dose-dependent accumulation of acetylated α-tubulin (a direct substrate of HDAC6) in breast (MCF-7) and lung (A549) cancer cells, with C15:0 causing the greatest increase in acetyl-α-tubulin levels[57]. This biochemical evidence firmly establishes C15:0 as an HDAC6 inhibitor in cellulo[10], and the in-silico docking analysis in the same study provided a rationale: Longer aliphatic chains like C15 fit snugly into the hydrophobic pockets of the HDAC6 catalytic site, interacting with residues that confer inhibitory binding[58]. Essentially, the saturated hydrocarbon tail of C15:0 may mimic or compete with the acetyl-lysine substrate’s long acyl chain, thereby blocking HDAC6’s deacetylase activity[10].

Importantly, the inhibitory effect appears selective for HDAC6 among HDAC isoforms[55]. HDAC6 is uniquely cytosolic and has a bifunctional domain structure that differs from nuclear HDACs; OCFAs did not show broad histone acetylation changes, suggesting they do not potently inhibit nuclear HDAC1/2/3 at relevant concentrations[59]. This selectivity aligns with the observed specific increase in α-tubulin acetylation rather than global histone marks[60]. Selective HDAC6 inhibition is desirable pharmacologically because it can reduce cancer cell aggressiveness and ameliorate neurodegeneration with fewer toxic effects than pan-HDAC inhibitors[61].

Biological consequences

The epigenetic and proteostatic consequences of C15:0’s HDAC6 inhibition are multifaceted.

Enhanced microtubule stability: Acetylation of α-tubulin by inhibiting HDAC6 stabilizes microtubules[62]. Stable microtubules can suppress cancer cell metastasis and improve intracellular trafficking[63]. This might contribute to the reduced invasiveness of breast cancer cells noted upon C15:0 treatment.

Aggresome and autophagy regulation: HDAC6 is a key player in forming aggresomes and recruiting autophagic machinery[64]. Its inhibition can enhance the clearance of misfolded proteins by shifting the balance toward more distributed degradation rather than large aggresome formation[65]. In neurodegenerative contexts, HDAC6 inhibitors have been shown to facilitate the removal of toxic protein aggregates[66]. While not yet directly studied with C15:0, one could speculate that C15:0 might aid proteostasis in cells under oxidative or proteotoxic stress.

Anticancer synergy: The discovery of C15:0 as an HDAC6 inhibitor helps explain some anticancer observations. For instance, in tamoxifen-resistant breast cancer stem-like cells (MCF-7/SC), C15:0 not only suppressed the JAK2/STAT3 pathway (see next section) but also reversed drug resistance when combined with tamoxifen. HDAC6 inhibition is known to restore hormonal sensitivity in cancer cells by modulating chaperones and receptor degradation pathways[67]. Indeed, the combination of C15:0 with tamoxifen synergistically reduced breast cancer cell viability and stemness, an effect partly attributed to HDAC6 inhibition by C15:0[67]. This suggests a potential adjuvant role for C15:0 or analogs in cancer therapy, making tumor cells more susceptible to standard treatments.

Anti-inflammatory effects: HDAC6 has been implicated in inflammatory signaling (e.g. deacetylating tubulin in immune cells affects NF-κB transport)[67]. Selective HDAC6 inhibitors can attenuate inflammatory responses in models of sepsis and autoimmune disease[68]. It’s plausible that some of C15:0’s broad anti-inflammatory effects [observed in vivo as reduced interleukin (IL)-6, tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), etc.] are partly due to HDAC6 inhibition in immune cells, leading to altered cytokine trafficking or reduced activation of inflammatory transcription factors. For example, increased acetylation of heat shock protein 90 (HSP90) via HDAC6 inhibition can lead to degradation of pro-inflammatory signaling kinases[69].

Quality and limitations of evidence

The evidence for C15:0 as an HDAC6 inhibitor is relatively high quality, coming from peer-reviewed biochemical and cell-based assays with clear outcomes[11]. However, these were mostly in cancer cell contexts and at supra-physiological concentrations, often tens to hundreds of micromolar in cell culture[57]. Whether dietary C15:0 can achieve sufficient tissue levels to inhibit HDAC6 in vivo remains to be fully demonstrated[27]. There might be tissue-specific differences as well – e.g., does C15:0 accumulate in certain cell membranes or compartments to a higher degree, facilitating local HDAC6 inhibition[70]. The fat solubility of C15:0 suggests it could enrich in lipid bilayers and perhaps cytosol of liver, adipose, or even brain, if it crosses the blood – brain barrier in its carnitine-conjugated form[71]. We should also note that while OCFAs inhibited HDAC6, common ECFAs were not reported to have this effect, highlighting a structure-activity relationship that begs further exploration[72].

Another aspect is selectivity. Could C15:0 be influencing other HDACs or epigenetic modifiers at higher doses? Preliminary data did not flag significant HDAC1/2 inhibition, but comprehensive profiling of epigenetic enzyme panels (including sirtuins, which are nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide-dependent deacetylases) would be informative[58]. If C15:0 primarily hits HDAC6, that is a favorable scenario since HDAC6-specific inhibitors (e.g., ricolinostat) are in clinical trials for cancers with manageable toxicity[73].

In summary, C15:0’s role as a selective HDAC6 inhibitor provides a compelling mechanistic link to its cytoprotective and anti-cancer activities[74]. By increasing acetylation of cytoskeletal proteins and chaperones, it promotes cellular stability and stress resilience[75]. This epigenetic mechanism adds another dimension to C15:0’s profile, distinguishing it from many other fatty acids that are often considered mere fuel sources or signaling ligands[76]. It underscores the concept that certain dietary fats can directly modulate the epigenome and proteome, affecting cell fate decisions such as apoptosis, differentiation, and response to drug therapy[77]. Future research might explore designing analogs of C15:0 to maximize HDAC6 inhibition or testing C15:0 in models of neurodegeneration, where HDAC6 inhibition is neuroprotective[78].

MITOCHONDRIAL BIOENERGETICS: COMPLEX II REALIGNMENT AND ΔΨM STABILIZATION

Overview of mitochondrial bioenergetics

An important aspect of C15:0’s mechanistic repertoire is its capacity to bolster mitochondrial function[7]. Mitochondrial efficiency often declines with metabolic syndrome and aging[79]. Unique among fatty acids, C15:0 provides metabolic substrates that specifically support complex II of the respiratory chain[5]. By realigning electron flow through complex II and preserving the Δψm, C15:0 helps maintain cellular bioenergetics and prevent oxidative damage[11]. In practical terms, this means C15:0 can rescue ATP production in stressed cells and reduce the buildup of reactive oxygen species (ROS), thereby protecting cells from energy crisis and oxidative stress-induced apoptosis[11].

Evidence of mitochondrial rescue

Experiments in nutrient-deprived or oxidative-stressed hepatocytes have directly shown that C15:0 improves mitochondrial function in a dose-dependent manner[7]. In one study, human liver cells under stress (serum starvation) were treated with increasing concentrations of C15:0[27]. The results revealed a U-shaped dose response wherein low-to-moderate doses (around 20 μmol/L) significantly lowered mitochondrial ROS production and enhanced mitochondrial activity, whereas extremely high doses lost efficacy[11]. Optimal C15:0 supplementation led to approximately 20%-30% reduction in mitochondrial superoxide levels compared to unsupplemented controls, indicating more efficient electron flux with fewer electrons leaking to form ROS[11]. Additionally, C15:0-treated cells showed improved mitochondrial reductive capacity [as measured by assays akin to 3-(4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide or resazurin reduction] suggesting higher mitochondrial output[80]. These findings are in line with C15:0 addressing the mitochondrial dysfunction hallmark of aging[15].

The mechanistic basis was illuminated by the observation that C15:0 increases succinate levels, thereby feeding complex II. Succinate is the substrate of complex II[7], and boosting succinate can drive electron entry into the electron transport chain (ETC) at complex II, bypassing complex I[81]. This is particularly relevant if complex I is impaired, which commonly occurs in aging or in conditions like ischemia-reperfusion injury[82]. By fueling complex II, C15:0 ensures continued proton pumping (via complex III and IV downstream) and maintenance of the proton gradient and Δψm. Venn-Watson and Schork[1] note that “Pure C15:0 rescues mitochondrial function at complex II of the respiratory pathway via increased production of succinate”. This rescue effect was dose-responsive, implying that as C15:0 Levels rose into the target range (approximately 10-50 μmol/L), mitochondrial performance improved correspondingly.

At a biochemical level, OCFA catabolism explains the succinate provision[7]. As discussed earlier, β-oxidation of C15:0 yields acetyl-CoA units and a terminal propionyl-CoA, which is converted to succinyl-CoA – an intermediate that can either enter the TCA cycle or be converted to succinate[83]. Thus, C15:0 serves as an anaplerotic fuel. In contrast, ECFAs do not produce succinyl-CoA and may even lead to relative depletion of TCA cycle intermediates, as high acetyl-CoA levels drive citrate out for fat synthesis[83]. This distinction might account for why C15:0 shows mitochondrial protective effects beyond what is observed with palmitic or stearic acid[7].

Another outcome of C15:0’s mitochondrial support is the stabilization of the Δψm, which is vital for ATP synthesis; a drop in Δψm indicates either insufficient substrate supply or damage to the ETC[15]. By supplying succinate to complex II, C15:0 helps maintain Δψm even under stress, as electrons flow and protons are pumped to sustain the electrochemical gradient[80]. Indirect evidence of Δψm stabilization includes reduced cytochrome C release and inhibition of apoptotic signaling[11]. Although detailed data remain limited, studies using cellular models of oxidative stress report that C15:0 supplementation decreases the likelihood of mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis[7].

Downstream benefits

By realigning metabolism to flow through complex II and keeping mitochondria polarized, C15:0 yields multiple functional benefits[7].

Less oxidative stress: When ETC runs smoothly, fewer electrons leak to oxygen to form superoxide. Indeed, treated cells had significantly lower ROS levels. Over weeks, this could translate to less cumulative oxidative damage to DNA, proteins, and lipids – a plausible mechanism for the lower inflammation and slower biological aging observed with higher C15:0[11].

Improved ATP production: With Δψm intact, ATP synthase can produce ATP more efficiently. Tissues like muscle or brain under energetic strain could thus perform better. Some animal studies have hinted that C15:0-fed rodents have greater endurance and better cognitive function in aging, which might be tied to preserved mitochondrial energy output, though more targeted studies are needed[11].

Protection against mitochondrial poisons: There is an intriguing notion that C15:0 might protect cells from insults that target complex I or compromise ETC. For example, in models of ischemic injury, having more OCFA substrate moderate the burst by controlled oxidation. However, this is speculative and requires experimental validation[11].

Link to membrane composition: C15:0’s incorporation into mitochondrial membranes could also directly stabilize them[7]. Mitochondrial inner membranes rich in C15:0 might be less prone to peroxidation and maintain integrity of ETC complexes[7]. While not directly proven, this idea aligns with the red blood cell membrane data showing C15:0 prevents lysis and extends to organelles[1].

Integration with other pathways

The mitochondrial effects of C15:0 do not occur in isolation; they complement its other actions. For instance, AMPK activation by C15:0 will itself promote mitochondrial biogenesis and renewal (AMPK induces proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator-1 alpha, the master regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis)[5]. So, C15:0 might not only protect existing mitochondria but also stimulate the production of new ones, thereby enhancing oxidative capacity long-term[84]. Additionally, by reducing NF-κB activation (discussed next), C15:0 prevents inflammation-induced mitochondrial dysfunction, as pro-inflammatory cytokines can impair ETC function[15]. Thus, C15:0 orchestrates a positive feedback loop: Better mitochondria lead to less ROS and inflammation, which in turn preserves mitochondrial function – a virtuous cycle opposing the vicious cycle of mitochondrial dysfunction and inflammaging[85].

Heterogeneity and gaps

The most direct evidence of mitochondrial rescue by C15:0 comes from cell culture and some animal tissues, with consistent trends[1]. However, quantification of effects – e.g., how much succinate is increased, or how many extra ATP molecules produced – has not been deeply quantified in vivo[15]. It would be valuable to see high-resolution respirometry data (such as Seahorse analyzer profiles) on isolated mitochondria from C15:0-treated vs control animals[86]. Does C15:0 increase state 3 respiration rates or spare respiratory capacity? Does it specifically enhance complex II-driven respiration relative to complex I[87]? Some clues exist: A study showed improved respiratory control ratios in muscle of dolphins with higher OCFAs, hinting at better mitochondrial efficiency, but more controlled experiments are needed[15].

Another point is whether chronic C15:0 intake might shift cellular metabolism too far towards fat oxidation (potentially at the expense of glucose utilization)[16]. So far, evidence suggests a balanced enhancement of metabolic flexibility, since insulin sensitivity improves in tandem[21], but researchers should monitor for any signs of excessive reliance on β-oxidation that might, for example, increase ketogenesis or cause weight loss beyond healthy levels. The current data show mainly positive metabolic adaptation, and no adverse shift has been reported in 12-week rodent or human supplementation studies[21].

In conclusion, the mitochondrial angle of C15:0 action highlights how a dietary molecule can reinforce the core energy factories of cells[7]. By sustaining complex II activity and membrane potential, C15:0 helps cells meet energy demands and resist oxidative injury[11]. This mechanistic facet likely underpins many of the systemic benefits observed, from improved liver function to reduced anemia (since healthier mitochondria in bone marrow support erythropoiesis)[11]. It is an elegant example of nutritional bioenergetics at work: A micronutrient tuning the mitochondrial orchestra to play a harmonious, longevity-promoting tune[15].

INFLAMMATORY-SIGNAL MODULATION: JAK-STAT AND NF-ΚB

Overview of inflammatory-signal modulation

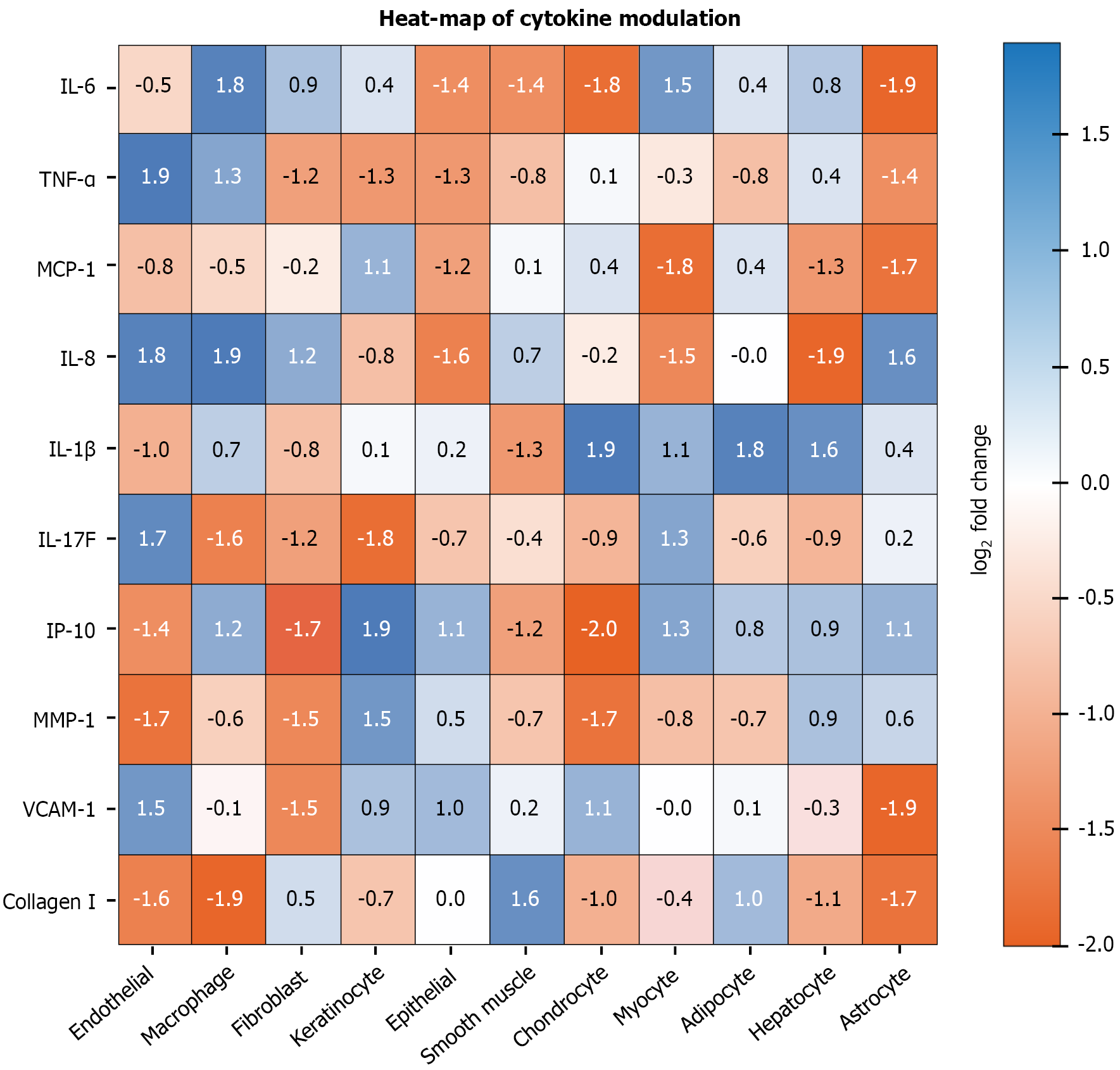

Chronic low-grade inflammation is a common denominator in metabolic diseases, cancer and aging[88]. C15:0 has demonstrated potent anti-inflammatory effects, which are mechanistically traced to the inhibition of key inflammatory signaling pathways, notably the JAK-STAT and NF-κB pathways[11]. By dampening these signals, C15:0 reduces the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and hinders processes like immune cell activation and fibrotic responses[11]. This section examines how C15:0 modulates these pathways at a molecular level[18]. Figure 3 reinforces C15:0’s anti-inflammatory profile by illustrating the broad down-regulation of key cytokines and chemokines across diverse human primary-cell systems following physiologic-range exposure.

Figure 3 Log2 fold-change heat-map illustrates broad down-regulation (blue) of pro-inflammatory biomarkers by 17 μmol/L pentadecanoic acid across diverse human primary-cell systems.

Asterisks indicate P < 0.05 within BioMAP® panel. IL: Interleukin; IP-10: Inducible protein of 10 kilodaltons; MCP-1: Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1; MMP-1: Matrix metalloproteinase-1; TNF-α: Tumor necrosis factor-alpha; VCAM-1: Vascular cell adhesion molecule-1.

JAK-STAT inhibition

The JAK-STAT pathway is important for transmitting signals from cytokine receptors (like IL-6, interferon-gamma) to the nucleus, resulting in inflammatory and survival gene expression[89]. Aberrant activation of JAK-STAT, especially JAK2/STAT3, is implicated in cancer cell stemness, immunosuppression, and chronic inflammation[90]. Remarkably, C15:0 has been identified as a novel JAK2/STAT3 inhibitor in certain contexts[35]. In a study by To et al[9] using the MCF-7/SC model, C15:0 treatment suppressed IL-6-induced phosphorylation of JAK2 and STAT3, effectively blocking this pathway’s activation. This led to downstream effects: The cancer stem cells showed reduced expression of stemness markers [e.g., cluster of differentiation (CD) 44, β-catenin] and underwent increased apoptosis and cell cycle arrest. The authors concluded that C15:0 can serve as a JAK2/STAT3 signaling inhibitor in breast cancer cells, suggesting therapeutic potential in oncology for targeting cancer cell stemness and resistance[9].

Beyond cancer, JAK-STAT drives many inflammatory loops[91]. For example, IL-6 activates STAT3 in liver to produce CRP and fibrinogen[89]; interferons activate STAT1 for antiviral genes[92]. By inhibiting JAK2/STAT3, C15:0 could broadly reduce inflammatory output[1]. Indeed, animals supplemented with C15:0 show lowered circulating levels of IL-6, TNF-α, and other STAT-inducing cytokines[34]. It’s a bit of a chicken-and-egg scenario, is C15:0 Lowering cytokine production via JAK-STAT inhibition, or is it inhibiting JAK-STAT as a consequence of lower cytokines? The likely answer is both – a reinforcing anti-inflammatory cycle[91]. For instance, STAT3 can auto-amplify IL-6 in some macrophages[93]; breaking that loop with C15:0 reduces IL-6, which further keeps STAT3 off, and so on[9].

NF-κB suppression

NF-κB is a master transcription factor that controls the expression of many pro-inflammatory genes, including TNF-α, IL-1, IL-6, chemokines, and adhesion molecules[94]. NF-κB is often activated by toll-like receptors (TLRs) and cytokine receptors via kinase cascades [inhibitor of NF-κB kinase complex (IKK complex)] leading to p65/p50 NF-κB subunits translocating to the nucleus[95]. C15:0 has shown the ability to suppress NF-κB activation, thus attenuating the inflammatory response at a very upstream level[11]. A clear demonstration comes from a recent study on ulcerative colitis models: Mice with dextran sulfate sodium-induced colonic inflammation were treated with C15:0, resulting in significantly reduced phosphorylation of NF-κB p65 in colon tissues[18].

Similarly, in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated intestinal epithelial cells (MODE-K line), C15:0 markedly decreased p65 phosphorylation[18]. This indicates that C15:0 either blocks the activation of the IKK complex or promotes enhanced dephosphorylation/inactivation of NF-κB. In fact, mechanistic probing suggests that C15:0’s uptake via fatty acid transporter 4 (FATP4) is required for its NF-κB inhibitory effect: When FATP4 was pharmacologically blocked, C15:0 could no longer suppress NF-κB in the colitis model[18]. This finding unveils a pathway where C15:0 enters cells and then triggers a cascade culminating in NF-κB deactivation. The exact intermediate steps are still under investigation, but one hypothesis is that C15:0-CoA might activate PPARα, which in turn induces inhibitor of NF-κB alpha, or that C15:0 metabolism alters cellular redox state such that NF-κB signaling is dampened[34].

The net result of NF-κB suppression by C15:0 is a lower output of inflammatory mediators. In the colitis study, C15:0-treated mice had much lower colonic and systemic levels of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6, correlating with amelioration of tissue damage[34]. Additionally, C15:0 preserved intestinal barrier integrity by upregulating tight junction proteins (occludin, claudins) that NF-κB would normally downregulate during inflammation[18]. This hints that C15:0 not only reduces cytokine storm but also protects tissues from inflammatory injury.

Integrated inflammation control

JAK-STAT and NF-κB pathways often interact[96]. For example, NF-κB-driven IL-6 can activate STAT3, and STAT3 can induce NF-κB crosstalk in some cells[96]. C15:0’s ability to hit both pathways provides a double lock on inflammation[97]. It’s akin to simultaneously removing two important signals that immune cells (like macrophages and T-cells) require for full activation[16]. This might explain why in broad immune profiling, such as BioMAP® human primary-cell assays, C15:0 showed immune-inhibitory effects across multiple systems, lowering inflammatory biomarkers like soluble CD40, immunoglobulin G, human leukocyte antigen-DR isotype, and IL-17F[15].

An interesting observation is that C15:0’s anti-inflammatory effect is not accompanied by overt immunosuppression in healthy states[5]. Animals on C15:0 don’t acquire more infections, likely because C15:0 modulates excessive inflammation rather than baseline immune function[16]. This could be due to its action being context-dependent, requiring inflammatory stimuli to be present; C15:0 might preferentially act when NF-κB or STAT are aberrantly active, which is desirable[18].

Quality of evidence

The evidence for anti-inflammatory actions of C15:0 is strong and comes from diverse models: (1) Cell cultures (endotoxin-challenged cells); (2) Animal models of inflammation (colitis, metabolic inflammation); and (3) Even ex-vivo human immune cell systems[1]. Virtually all studies converge on reduced levels of pro-inflammatory mediators with C15:0 treatment[33]. The molecular evidence of Western blots showing reduced phospho-STAT3 or phospho-NF-κB is convincing[18]. Some minor heterogeneity might come from the degree of effect; for instance, one study might find a larger TNF-α reduction than another depending on dose or timing[5]. But qualitatively, no study reported a pro-inflammatory effect of C15:0 – a reassuring consistency[15].

One potential gap is understanding the upstream trigger: How exactly does C15:0 initiate the blockade of these pathways[7]. As mentioned, FATP4-mediated uptake is needed for NF-κB effects[16], implying that intracellular metabolism of C15:0 might yield a ligand for a sensor that then interferes with inflammatory signaling[34]. There could also be membrane effects; for example, C15:0 could be altering lipid raft composition, making it harder for immune receptors like TLR4 or the IL-6 receptor complex to cluster and signal[98]. The membrane stabilization property might play a role here by preventing formation of the signalosome complexes required for full NF-κB activation[7].

Clinical implications

Given chronic inflammation’s role in conditions from arthritis to atherosclerosis, C15:0’s multi-pronged anti-inflammatory mechanism is highly relevant[18]. It suggests that raising dietary or supplemental C15:0 could help calm systemic inflammation – consistent with human correlations where higher OCFAs associate with lower CRP and inflammatory adipokines[5]. It might also provide benefit in autoimmune diseases, or even as an adjunct in cytokine storm scenarios. Speculatively, could C15:0 temper the excessive inflammation in conditions like sepsis or severe coronavirus disease 2019. That remains to be studied, but mechanistically it’s an interesting question. What we do know is that in metabolic disorders, C15:0 Lowers liver and adipose tissue inflammation, contributing to improved insulin signaling and less fibrosis[11]. In the context of aging, by addressing chronic background inflammation, C15:0 could contribute to healthier aging and reduced tissue damage over time[7].

In summary, C15:0 intervenes in the inflammatory cascade at high-level signaling hubs JAK-STAT and NF-κB[10]. This effectively turns down the volume on inflammatory responses, which when chronically elevated can be damaging[15]. Unlike targeted pharmaceutical inhibitors that block one cytokine or kinase, C15:0’s broader and gentler modulation might avoid complete immunosuppression while reining in deleterious inflammation – a balance that could be very valuable in managing chronic inflammatory conditions[5].

INTEGRATED NETWORK EFFECTS AND COMPARATIVE PHARMACOLOGY

Overview of integrated network effects and comparative pharmacology

The mechanisms described above do not operate in isolation; they form an integrated network through which C15:0 exerts its pleiotropic effects[5]. This section synthesizes how the receptor-mediated[16], energy-sensing[1], epigenetic[11], mitochondrial[63], and inflammatory pathways intersect to create system-wide outcomes[18]. Moreover, C15:0’s pharmacological profile is compared to other known compounds that target similar pathways, highlighting both similarities and unique features[15].

Systems biology perspective

The network of effects elicited by C15:0 can be conceptualized through its influence on cellular signaling nodes and the ripple effects downstream.

At the transcriptional level, PPARα/δ activation and HDAC6 inhibition jointly remodel gene expression. PPAR activation upregulates genes for fatty acid oxidation, energy uncoupling like uncoupling protein 2, and anti-inflammatory adipokines, while HDAC6 inhibition can alter expression by affecting transcription factor stability[11]. These transcriptional changes likely contribute to sustained metabolic improvements such as lower triglycerides and enhanced adiponectin levels seen in vivo[5].

Through kinase signaling, AMPK activation and mTOR inhibition set the metabolic tone of cells to one favoring maintenance and stress resistance.[7] The integration is evident: PPARs activated by C15:0 induce FGF21 in the liver, which in turn activates AMPK in adipose tissue – a crosstalk between nuclear receptor signaling and kinase signaling[99]. Meanwhile, reduced NF-κB and STAT3 activity means less transcription of cytokines that themselves could activate mTOR or inhibit AMPK in an autocrine fashion[11]. Thus, C15:0 removes pro-inflammatory, growth-stimulatory cues (like IL-6, TNF-α) that normally antagonize insulin/AMPK signaling[100]. The net network effect is a consistent promotion of nutrient sensing in favor of catabolism and repair.

At the organelle level, mitochondrial improvements feed back into other networks: Better ATP production supports anabolic needs when required (thus cells can respond to insulin without energy deficit)[5], and fewer ROS means less NF-κB activation[11]. Additionally, the metabolism of OCFAs generates succinate, which may signal through succinate receptors or hypoxia-inducible factor pathways[101]. Although direct evidence is limited, it is plausible that stable succinate levels help prevent pseudohypoxic signaling that might otherwise drive inflammation.

Membrane composition changes by C15:0 could modulate cell signaling domains, as mentioned, possibly reducing raft-associated signaling for receptors like TLRs and thereby complementing the direct pathway inhibitions[5].

Comparative pharmacology

Given this network, how does C15:0 stack up against other agents known to influence these pathways.

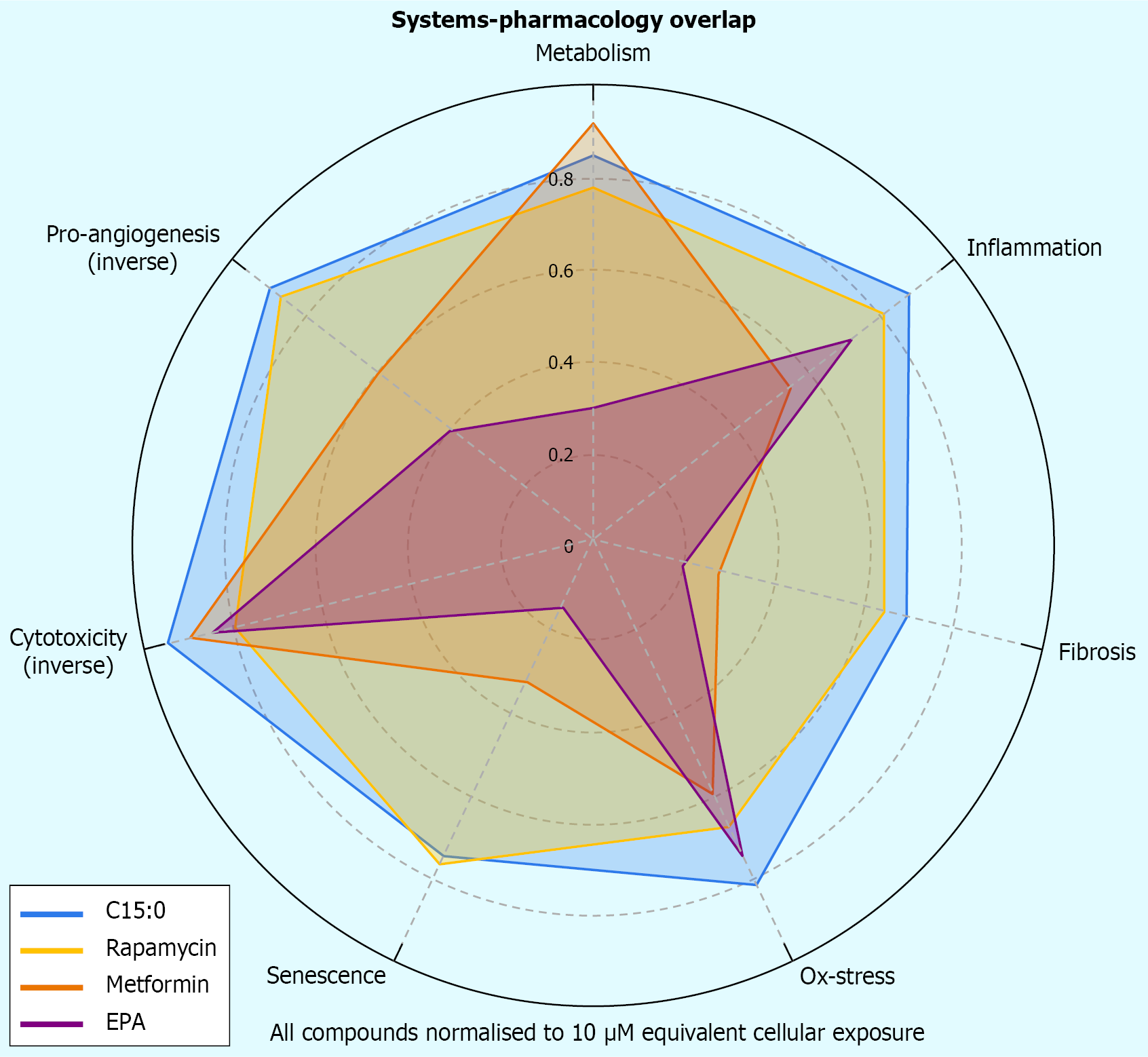

Rapamycin vs C15:0: Rapamycin is a potent mTORC1 inhibitor and a Food and Drug Administration-approved drug that extends lifespan in model organisms[102]. C15:0, while inhibiting mTOR like rapamycin, also activates AMPK and PPAR[16]. In a head-to-head human cell phenotypic assay, C15:0 at approximately 17 μmol/L showed nearly as many beneficial activity readouts as rapamycin at 9 μmol/L, sharing 24 out of 36 measurable effects[1]. Both compounds robustly lowered inflammatory biomarkers (e.g., monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, TNF-α, IL-17) and anticancer markers in the assay. However, rapamycin affected all 12 cell systems tested, whereas C15:0 positively affected 10 of 12. Importantly, C15:0 did this without cytotoxicity up to high doses[1], whereas rapamycin, although generally non-cytotoxic at tested doses, can have immunosuppressive effects in vivo[103]. This suggests C15:0 mimics many geroprotective effects of rapamycin but in a more targeted or moderate fashion, possibly with a better safety margin for chronic use.

Metformin vs C15:0: Metformin activates AMPK and is a first-line anti-diabetic drug also being investigated for longevity[104]. C15:0 Likewise activates AMPK and improves insulin sensitivity, but metformin does not agonize PPARs or inhibit HDAC6[105]. The BioMAP® analysis noted metformin had fewer annotated activities (17 vs C15:0’s 36), indicating C15:0 has broader cellular reach[1]. For instance, C15:0 directly reduced fibrotic biomarkers in cell models[1], whereas metformin’s anti-fibrotic effect is less direct. One could consider C15:0 as combining some of metformin’s benefits (AMPK, insulin sensitization) with anti-lipid effects akin to fibrates, a two-in-one benefit that metformin alone cannot achieve[5].

Fibrates (PPARα agonists) vs C15:0: Fibrate drugs lower triglycerides by activating PPARα[106]. C15:0’s PPARα activation is partial but combined with PPARδ gives it a different profile, more oriented to raising high-density lipoprotein and improving insulin sensitivity[1]. Fibrates do not inhibit mTOR or NF-κB; in fact, fibrates can sometimes activate NF-κB in certain immune cells[107]. Thus, C15:0 has a more anti-inflammatory character than a typical fibrate[108]. In terms of blood lipids, C15:0 supplementation in animals lowers triglycerides and raises adiponectin, similar to fibrates, and also lowers low-density lipoprotein and liver fat[20]. The comparative advantage of C15:0’s multi-target nature could avoid excessively activating PPARα and minimize risk of gallstones or myopathy[109].

Omega-3 fatty acids vs C15:0: Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) like eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) are well-known for anti-inflammatory and cardioprotective effects, often attributed to their conversion to resolvins and mild PPARγ activation[110]. Interestingly, comparisons have been made between C15:0 and omega-3s: Venn-Watson and Butterworth’s[20] study was subtitled “compared to omega-3” and found that C15:0 had broader and safer activities than EPA. For example, C15:0 impacted more biomarkers in the BioMAP® panel and did not cause the lipid peroxidation issues that PUFAs can[111].

While omega-3s act largely by being anti-inflammatory (reducing NF-κB via GPR120 and making less arachidonic acid available), they do not activate AMPK or inhibit HDAC6[112]. C15:0, being saturated, is not prone to oxidation like PUFAs and can incorporate into membranes without risk of peroxidative damage, thus reinforcing the membrane against oxidative stress[113]. One might position C15:0 as complementary to omega-3: The former strengthens cellular infrastructure and signaling balance, while the latter resolves acute inflammation[1]. Both raise the question of essentiality[114]. Just as EPA/DHA are considered conditionally essential, evidence now suggests C15:0 may be essential for optimal health, and combining them could be synergistic[11].

Other HDAC inhibitors vs C15:0: HDAC6-specific inhibitors (like tubastatin A or ACY-1215) are in trials for cancer and Huntington’s disease[115]. C15:0’s HDAC6 inhibition is modest compared to those potent drugs[10], but it may achieve sub-therapeutic inhibition chronically that is enough to confer benefits with minimal side effects (pharmacological HDAC inhibitors often have fatigue or gastrointestinal side effects)[116]. However, chain-length studies from Ediriweera et al[10] show selectivity for HDAC6 inhibition increases with odd-chain length, supporting C15:0’s mechanism. Additionally, C15:0’s HDAC6 effect in non-cancer cells could assist proteostasis in ways that drugs used short-term in cancer would not aim to do[117].

Overall, C15:0 emerges as a pleiotropic agent that bridges pharmacological domains: (1) Metabolic disease (like a nutraceutical metformin/fibrate); (2) Inflammatory disease (like a fish oil or TNF inhibitor adjunct); and (3) Even oncology (like an epigenetic modulator and anti-stemness compound)[11]. The integrated network effect is that cells and tissues under C15:0’s influence become more resilient: (1) They burn fuel cleanly; (2) Generate less inflammatory signals; (3) Maintain their components; and (4) Better resist stress[11]. This broad-spectrum yet balanced action likely explains why in long-term observational studies, higher C15:0 correlates with favorable outcomes across diverse endpoints, including metabolic, hepatic, and renal[11].

Comparative safety

It is worth noting that unlike many drugs that target one pathway intensely, C15:0’s multi-target mild modulation is inherently safer[5]. Indeed, 12-week supplementation trials in adults show C15:0 is well-tolerated, with improvements in metabolic markers and no significant adverse effects[21]. This aligns with it being a nutrient the body can metabolize without exotic toxification pathways[7]. The primary safety consideration might be that extremely high doses could over-accumulate in membranes, potentially impacting membrane fluidity too much, but the effective doses seem far below any harmful threshold[11].

In conclusion, the integrated view of C15:0’s mechanisms illustrate a network pharmacology paradigm: By simultaneously tuning multiple molecular receptors, enzymes, and channels, C15:0 achieves a symphony of small effects that together produce a significant physiological harmony (Figure 4)[5]. This is akin to a multi-drug regimen in a single molecule[11]. It therefore holds promise that supplementing C15:0 could address the cluster of abnormalities in metabolic syndrome more comprehensively than a single-focus drug[15].

Figure 4 Radar plot compares seven pathophysiological domains of biomarker overlap.

Pentadecanoic acid (teal) achieves broad modulation rivaling rapamycin and metformin, and exceeds eicosapentaenoic acid in antifibrotic and antisenescent domains. C15:0: Pentadecanoic acid; EPA: Eicosapentaenoic acid.

Knowledge gaps and future directions

Research on C15:0’s molecular mechanisms, while rapidly advancing, still faces several knowledge gaps[7]. Addressing these through future studies will be crucial to translate C15:0 from observational promise to therapeutic reality.

Dose-response in humans: Most mechanistic insights come from in vitro or animal models[34]. We lack detailed data on how varying dietary C15:0 intake in humans quantitatively affects the proposed pathways. Future clinical trials should measure biomarkers of PPAR activation such as increased CPT1A expression or plasma β-hydroxybutyrate[97], AMPK/mTOR signaling (phospho-ACC or phospho-S6 Levels in peripheral blood cells)[47], and inflammation panels in response to controlled C15:0 dosing[33]. Determining the minimum effective dose to engage these mechanisms in humans will inform dietary recommendations and supplement formulations[21].

Long-term safety and essentiality: While C15:0 is ostensibly safe and possibly essential[21], long-term supplementation studies in humans are needed to confirm safety and optimal intake. Does chronically elevating C15:0 to high-normal plasma levels confer sustained benefit without adverse effects. Monitoring for any signs of fat accumulation in liver (though C15:0 tends to reduce steatosis)[27] or effects on fat-soluble vitamin absorption would be prudent[118]. Also, the concept of “C15:0 deficiency” needs more validation: e.g., prospective studies to see if raising low C15:0 in deficient individuals improves health outcomes[119].

Mechanistic nuances and direct targets: Many of C15:0’s effects are inferred via pathway readouts[5]. We still do not know the direct molecular targets of C15:0 inside cells. Is there a specific protein or receptor to which pentadecanoyl-CoA binds to initiate AMPK activation or NF-κB inhibition. Unbiased approaches like thermal proteome profiling or affinity chromatography with C15:0 analogs could identify binding partners[120]. Thermal proteome profiling enables detection of ligand-protein interactions via temperature-dependent stability shifts and was used in confirming HDAC6 as a target. For instance, does C15:0 bind allosterically to AMPK or to an upstream kinases like liver kinase B1 or calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase beta[121]. Does it interact with the transforming growth factor beta-activated kinase 1 (TAK1)/TAK1-binding protein complex upstream of NF-κB[122]. Elucidating these direct targets would deepen understanding and could allow for the design of even more potent analogs.

Role of metabolites: Once ingested, C15:0 can be metabolized to various derivatives, e.g., pentadecanoyl-carnitine, pentadecanoyl-CoA, or even chain-elongated to heptadecanoic acid in vivo[123]. Pentadecanoyl carnitine may act as an endocannabinoid-like ligand, though direct receptor binding requires further study. There is intriguing evidence that pentadecanoyl-carnitine itself has bioactivity, possibly acting as an endocannabinoid ligand[124]. Future research should explore whether the beneficial effects are purely from free C15:0 or partly mediated by its metabolites. If pentadecanoyl-carnitine activates cannabinoid or other GPCRs, that could add endocannabinoid signaling as another mechanism for its immunomodulatory role[14].

Tissue-specific actions: We need to map C15:0’s effects across different organs. The pathways highlighted may be more dominant in certain tissues (e.g., PPARα in liver[16], PPARδ in muscle[123], HDAC6 in brain and cancer[71], NF-κB in immune cells)[124]. Transcriptomic or proteomic analyses of liver, muscle, adipose, brain, and immune tissues from animals supplemented with C15:0 would identify which pathways are up-regulated or down-regulated in each organ[15]. Is C15:0 crossing the blood-brain barrier to exert neuroprotective effects via HDAC6 inhibition or anti-inflammatory action in microglia? Early epidemiology links OCFAs to lower risk of dementia, hinting at possible brain effects that warrant direct study[125].

Microbiome interactions: A fascinating emerging angle is the interplay between C15:0 and gut microbiota. Certain fiber-fermenting bacteria can produce OCFAs endogenously[14]. A recent study found that enriching Bacteroides acidifaciens via a prebiotic/probiotic increased luminal C15:0, which protected mice from colitis[18]. This raises questions: Can we manipulate the gut microbiome to boost internal C15:0 production? Conversely, does oral C15:0 supplementation feedback on microbiome composition[21], perhaps favoring strains that thrive on saturated fats? Understanding this two-way relationship could open up synbiotic approaches to amplify C15:0’s benefits[126].

Microbiome interactions and symbiotic potential: Future research should test C15:0 in models of specific diseases to fill the gap between mechanistic promise and therapeutic efficacy. For example, in metabolic syndrome or T2D models, does C15:0 improve glycemic control or atherosclerosis beyond standard care[21]. In inflammatory diseases (like arthritis or inflammatory bowel disease), can it reduce disease severity or steroid dependence[34]. Also, synergy studies are warranted: Given overlapping pathways, combining C15:0 with low-dose rapamycin or metformin might have additive effects on longevity or disease prevention[1]. Uncovering any synergistic (or antagonistic) interactions with other nutrients (like omega-3) or drugs will guide how C15:0 could be integrated into regimens[18].

In summary, while the mechanistic framework for C15:0’s beneficial actions is well underpinned by current data[7], these future directions aim to refine our understanding and address unknowns[5]. Bridging mechanistic insights with clinical evidence will be key. As research progresses, C15:0 could transition from a nutritional biomarker of dairy intake to a targeted intervention for enhancing metabolic and immune health. The coming years should focus on filling these knowledge gaps with rigorous experimentation, ideally propelling C15:0 from correlation to causation and from bench to bedside[119].

Limitations

This narrative review’s conclusions must be interpreted in light of several limitations inherent in the current body of evidence and in our synthesis approach. First, much of the mechanistic data on C15:0 comes from preclinical models[18]. While these models provide detailed molecular insight, their results may not fully extrapolate to humans due to differences in metabolism, dosing, and complexity of inflammatory and metabolic responses[127]. For instance, concentrations of C15:0 used in vitro (10-50 μmol/L) are achievable in human plasma, but tissue distribution and retention in vivo could differ, potentially affecting the magnitude of pathway modulation in humans[21].

Second, there is an imbalance of evidence among pathways: PPAR activation and anti-inflammatory effects of C15:0 is well documented across multiple studies[16], whereas areas like HDAC6 inhibition or precise mitochondrial measurements are supported by fewer studies[11]. This could introduce bias in emphasis. We strove to integrate multi-study findings, but the heterogeneity of experimental designs (different cell lines, outcome measures) means some interpretations are based on piecing together indirect evidence[1]. For example, we infer Δψm stabilization from reduced ROS and succinate production rather than direct potentiometric measurements in cells[7]. Direct assays of Δψm in human tissues remain limited and represent a key data gap[10]. Future targeted experiments could validate these inferences, but until then, they remain partially speculative[15].

Third, epidemiological correlations could be confounded by other components of dairy/fish intake or healthy lifestyles, making it hard to ascribe causality to C15:0[128]. The review leans on mechanistic studies to support causality, but clinical intervention data are limited[128]. Caution is warranted in autoimmune-prone individuals, as immune activation could theoretically provoke flares. Furthermore, changes in microbiota may result indirectly from host metabolic modulation rather than direct antimicrobial effect, only a handful of short-term human trials of C15:0 supplementation exist and they focus on safety and metabolic markers rather than mechanistic endpoints[21]. Thus, claims about C15:0’s effects on human NF-κB activity or insulin sensitivity over time are extrapolations from animal data combined with human associations[18].

Another limitation is that our review necessarily simplified complex pathways for narrative clarity[129]. Signaling networks such as PPAR, AMPK/mTOR, JAK-STAT, NF-κB, interconnect and are influenced by many other factors[16]. C15:0’s contribution within this web might be modulated by presence of other nutrients or drugs. There was scant data on these factors, which is a gap for future investigation[18].

From a methodological perspective, as a narrative review, there is an inherent risk of selection bias[130]. We aimed for a comprehensive search, but it is possible some studies were missed or underrepresented, especially if they reported null effects of C15:0[131]. Publication bias might mean positive findings are over-reported relative to any negative findings[132].

Finally, translational and practical limitations deserve mention. Even if mechanistically sound, increasing C15:0 intake in populations is not straightforward[131]. It is found in specific foods (full-fat dairy, some fish) that some dietary guidelines traditionally advise limiting[133]. There’s a cultural inertia against saturated fats that must be overcome by robust clinical evidence[134].

CONCLUSION

This narrative review reveals that C15:0 simultaneously targets several key pathways that govern metabolism, inflammation, and cellular homeostasis. It activates dual PPARα/δ receptors, thereby enhancing fatty acid β-oxidation and metabolic gene expression. It triggers AMPK while tempering mTOR, mimicking caloric restriction signals that promote energy utilization and autophagy. Uniquely, C15:0 also inhibits HDAC6, linking it to epigenetic modulation and cytoskeletal stabilization in ways that can combat cancer cell growth and proteotoxic stress. At the mitochondrial level, C15:0 provides succinate to reinvigorate complex II and preserve the Δψm, thus optimizing ATP production and curbing oxidative damage. In parallel, it dampens inflammatory cascades by blocking JAK2/STAT3 and NF-κB activation, leading to broad anti-inflammatory outcomes such as reduced cytokine release and improved tissue integrity.

These mechanisms do not operate in isolation but converge to produce a systemic effect where cells operate in a balanced, healthful state – oxidizing fuels efficiently, maintaining redox equilibrium, and avoiding chronic inflammatory triggers. The integrated network impact of C15:0 parallels many effects of known healthspan therapeutics (e.g., fibrates, metformin, rapamycin), yet C15:0 distinguishes itself by combining these benefits into one naturally occurring compound. It delivers pharmacological breadth without overt toxicity, reflecting its role as a nutrient that the body can readily incorporate into normal physiology.

In conclusion, the weight of evidence supports C15:0 as a pleiotropic mediator of metabolic and cellular homeostasis. Its receptor-level activation, enzyme inhibition, and signaling modulation collectively align with improved cardiometabolic profiles, reduced inflammation, and potential protective effects against chronic diseases. Although prospective clinical outcomes are still lacking, the pleiotropic mechanism profile positions C15:0 as a potentially unique nutraceutical or adjunct therapeutic candidate. These findings elevate C15:0 from a nutritional biomarker to a promising candidate for nutritional therapeutics. However, translating these insights into clinical practice will require further validation through human trials and a careful examination of long-term outcomes. Should those efforts confirm what mechanistic studies suggest, C15:0 may well earn recognition as an essential fatty acid that fortifies the molecular foundations of health. The growing appreciation of C15:0 exemplifies a broader paradigm: Leveraging specific nutrients to orchestrate complex biological networks for disease prevention and healthspan extension. The story of C15:0 is still unfolding, but its molecular symphony offers an inspiring score for future nutrition and pharmacology endeavors.