Published online Dec 5, 2025. doi: 10.4331/wjbc.v16.i4.111110

Revised: July 16, 2025

Accepted: October 27, 2025

Published online: December 5, 2025

Processing time: 164 Days and 1.8 Hours

Neurodegeneration refers to the progressive loss of neurons, affecting both their structure and function. It is driven by synaptic dysfunction, disruptions in neural networks, and the accumulation of abnormal protein variants. Endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, caused by the accumulation of misfolded or unfolded pro

To study the neurodegeneration in C. elegans caused by DTT-induced ER stress, assessed by behavioral, molecular, and lifespan changes.

C. elegans were cultured on nematode growth medium plates with OP50, and ER stress was induced using DTT. Effects were assessed via behavioral assays such as locomotion, chemotaxis, lifespan assay, and molecular studies.

DTT exposure led to a significant decline in locomotion and chemotaxis response, indicating neurotoxicity. A reduction in lifespan was observed, suggesting an overall impact on health. Molecular analysis confirmed ER stress activation. DTT-induced ER stress negatively affects C. elegans, leading to behavioral impairments and molecular alterations associated with neurodegeneration.

These findings establish C. elegans as a potential model for studying ER stress-mediated neurotoxicity and its implications in neurodegenerative diseases.

Core Tip: Disturbancein the Protein folding process induces Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and sueseqeunct activation of unfolded Protein Response. accumulation of misfolded or unfolded proteins has been reported in the pathogenesis of several neurodegenerative diseases. Dithiothreitol (DTT), a potent endoplasmic reticulum stress inducer might involve in neurodegenration and related disorders. The present work aims to study the effects of DTT on the unfolded protein response activation and neurobehavioural effects in the Caenorhabditis elegans.

- Citation: Raj G, Kumar M, Shreya S, Bhardwaj S, Priya R, Mangalhara KC, Jain BP. Dithiothreitol induced endoplasmic reticulum stress and its role in neurodegeneration in Caenorhabditis elegans. World J Biol Chem 2025; 16(4): 111110

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8454/full/v16/i4/111110.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4331/wjbc.v16.i4.111110

Dithiothreitol (DTT) is a chemical compound that acts as a reducing agent, commonly used to break disulfide bonds in proteins. DTT induces endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress by disrupting the redox environment[1,2]. The ER is a dynamic organelle in eukaryotic cells, playing a central role in vital cellular functions such as protein synthesis, lipid metabolism, and calcium storage. Some ER has ribosomes attached to its surface, giving it a rough appearance; this is called rough ER. When ribosomes are absent, their surface appears smooth, and this is called smooth ER. The smooth ER is involved in detoxification, lipid metabolism, and calcium storage, while the rough ER primarily focuses on protein synthesis and quality control[3]. ER stress is a state of cells where the ER experiences an excessive load of altered proteins/unfolded proteins. This accumulation of unfolded or misfolded protein in the ER lumen is caused by various factors like oxidative stress, hypoxia, improper protein folding, imbalance in calcium homeostasis, and nutrient deprivation. This stress condition further affects the trafficking of proteins to their assigned destination[3,4]. Overaccumulation of unfolded proteins activates the unfolded protein response (UPR). The UPR leads to outcomes such as inhibition of protein synthesis, regulation of gene expression, and cell fate decisions like apoptosis to restore cellular homeostasis with the help of its three sensors. Inositol-requiring enzyme 1), PKR-like ER kinase, and activating transcription factor 6. These sensors are bound to binding immunoglobulin protein (BiP), which keeps them inactive. When unfolded or misfolded proteins accumulate in the ER lumen, they bind to BiP, causing its dissociation from the sensors. This dissociation activates the sensors and triggers the UPR[3,5]. The downstream effects of ER stress include endoplasm reticulum associate degradation, altered protein synthesis, autophagy activation, oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and metabolic reprogramming; ultimately, these lead to Neurodegeneration and several more disorders[6,7].

Neurodegeneration refers to the progressive loss of neurons, including their structure and function, caused by synaptic dysfunction, disruptions in neural networks, and the accumulation of abnormal protein variants. Due to the terminally differentiated nature of neurons, they cannot effectively renew themselves, resulting in irreversible damage. This process leads to impaired communication between neurons, affecting cognitive functions like memory and motor skills[8-11]. Neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s, are specific conditions where neurodegeneration manifests in distinct cognitive and motor impairments. Neurodegenerative disorders are a broader term that includes these diseases as well as other conditions, like amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, which also involve neuronal degeneration, disrupting various neural functions, and impacting overall health[11]. Neurodegenerative diseases are complex disorders caused by a combination of genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors. These factors contribute to the progressive loss of neurons and disruption of essential cellular processes[12,13].

Caenorhabditis elegans (C. elegans) is a free-living nematode widely used as a model organism in biological research due to its simplicity, versatility, and well-characterized biology. It thrives in both terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems and is easily maintained on agar plates in the laboratory, feeding on non-pathogenic bacteria[14,15]. C. elegans shares significant molecular similarities with humans while being anatomically simpler, making it an ideal model organism. It has five major systems: Epidermal, muscular, digestive, nervous, and reproductive[16]. The nervous system of C. elegans is well-characterized and provides significant insights into neuronal function and behavior. With 302 neurons, 56 glial cells, and 7000 synapses, the connectome is fully mapped, facilitating neural circuit studies[17,18]. The model organism employs three main neuron classes-chemosensory, mechanosensory, and thermosensory-to regulate sensory input and motor responses[16,17].

In neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s Disease, β-amyloid accumulation triggers ER stress, and modulating the IRE-1 branch of the UPR has shown therapeutic promise in reducing toxicity. The Parkinson's Disease model of C. elegans, expression of α-synuclein induces ER stress, and loss of function mutations in the LRRK2 gene exacerbate this stress, inactivating the sarco/ER Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) and disturbing the calcium homeostasis in the ER. This interaction highlights key molecular pathways that could be a potential target for therapeutic intervention[11,19,20].

ER stress is a condition that can disrupt cellular homeostasis and activate the UPR. However, if this stress persists for a prolonged period, it can cause damage to cells, particularly neurons, as they cannot repair or regenerate themselves. UPR activation can lead to structural and functional impairments in neurons, eventually contributing to neurodegenerative diseases[3,9]. In the present work effects of DTT exposure on the neurobehavioral activity and life span of the C. elegans were studied.

Wild-type C. elegans Bristol N2 strain was used in all experiments. Worms were maintained on nematode growth medium (NGM) agar plates seeded with Escherichia coli (E. coli) OP50 at 20 °C in a BOD incubator[15,18].

The OP50 E. coli culture used in this study was prepared following a standard protocol with slight modifications. A sterile 50 mL bacterial growth medium was prepared by dissolving KH2PO₄ (0.15 g), Na2HPO₄ (0.30 g), and NaCl (0.25 g) in double-distilled water (ddH2O). The solution was autoclaved (three whistles) to ensure sterilization. After cooling to room temperature, dextrose (0.5 mL), MgSO₄ (50 µL), NH₄Cl (0.5 mL), and uracil (200 µL) were added aseptically (15). The pre-existing E. coli OP50 culture was then inoculated into the sterile medium under aseptic conditions. The inoculated broth was incubated at 37 °C for 8 hours to allow sufficient bacterial growth. Freshly grown OP50 culture was used to seed NGM plates, and the remaining culture was stored at 4 °C for short-term use[15,18].

NGM was prepared following standard laboratory protocols. For every 100 mL of medium, 0.25 g bacto-peptone, 0.3 g NaCl, and 1.7 g agar were dissolved in distilled water and autoclaved at 121 °C for 15 minutes. After cooling the medium to approximately 55 °C, sterile solutions of 100 µL CaCl2 (1 M), 100 µL MgSO₄ (1 M), 100 µL cholesterol (5 mg/mL in ethanol), and 2.5 mL KH2PO₄ buffer (pH 6.0) were added aseptically[18]. For DTT-treated plates, DTT was added to the molten NGM at about 55 °C with appropriate concentrations before pouring. The medium, either standard or DTT-supplemented, was poured into sterile Petri plates under aseptic conditions, allowed to solidify, and stored at 4 °C until use[2].

Worms were synchronized using the bleaching method. Gravid adults were collected, washed with M9 buffer, and treated with a freshly prepared bleach solution (2.5 mL 1M KOH, 1 mL bleach, 1.5 mL distilled water) until worm bodies dissolved (about 5 minutes). Eggs were pelleted by centrifugation, washed 3 × with sterile M9 buffer, and allowed to hatch overnight at 20 °C in M9 to obtain synchronized L1 larvae. M9 buffer was prepared by dissolving KH2PO4 (1.5 g), Na2HPO4 (3 g), and NaCl (2.5 g) in 500 mL ddH2O. The solution was sterilized using an autoclave until three whistles were achieved, ensuring sufficient sterilization. After cooling to room temperature, 0.5 mL MgSO4 (1M) was added, providing the pH-7.0 of the buffer.

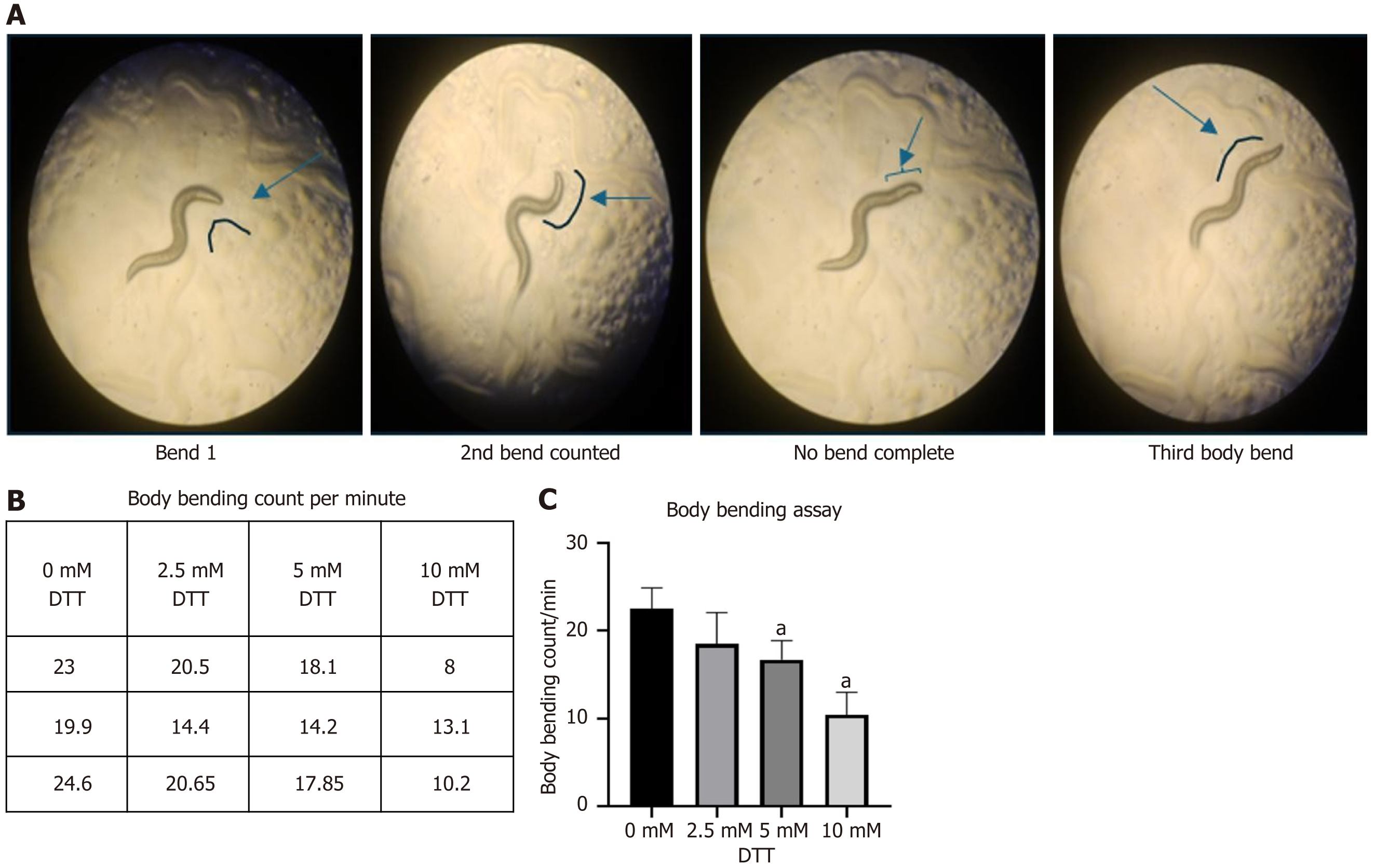

Body bend assay: Synchronized L4 stage worms were transferred directly to DTT-containing NGM plates (exposure plates). After 24 hours of exposure, at least 10 worms were picked individually and washed three times with M9 buffer to remove bacteria. Each worm was then transferred to a fresh, unseeded, neutral NGM plate. After 5–10 minutes of acclimation, a timer was set for 20 seconds, and the number of whole-body bends (head swing from left to right or right to left forming a curve) was recorded. This was done for 10 worms per group. The average number of body bends per 20 seconds was calculated and compared between different DTT concentrations and control[21].

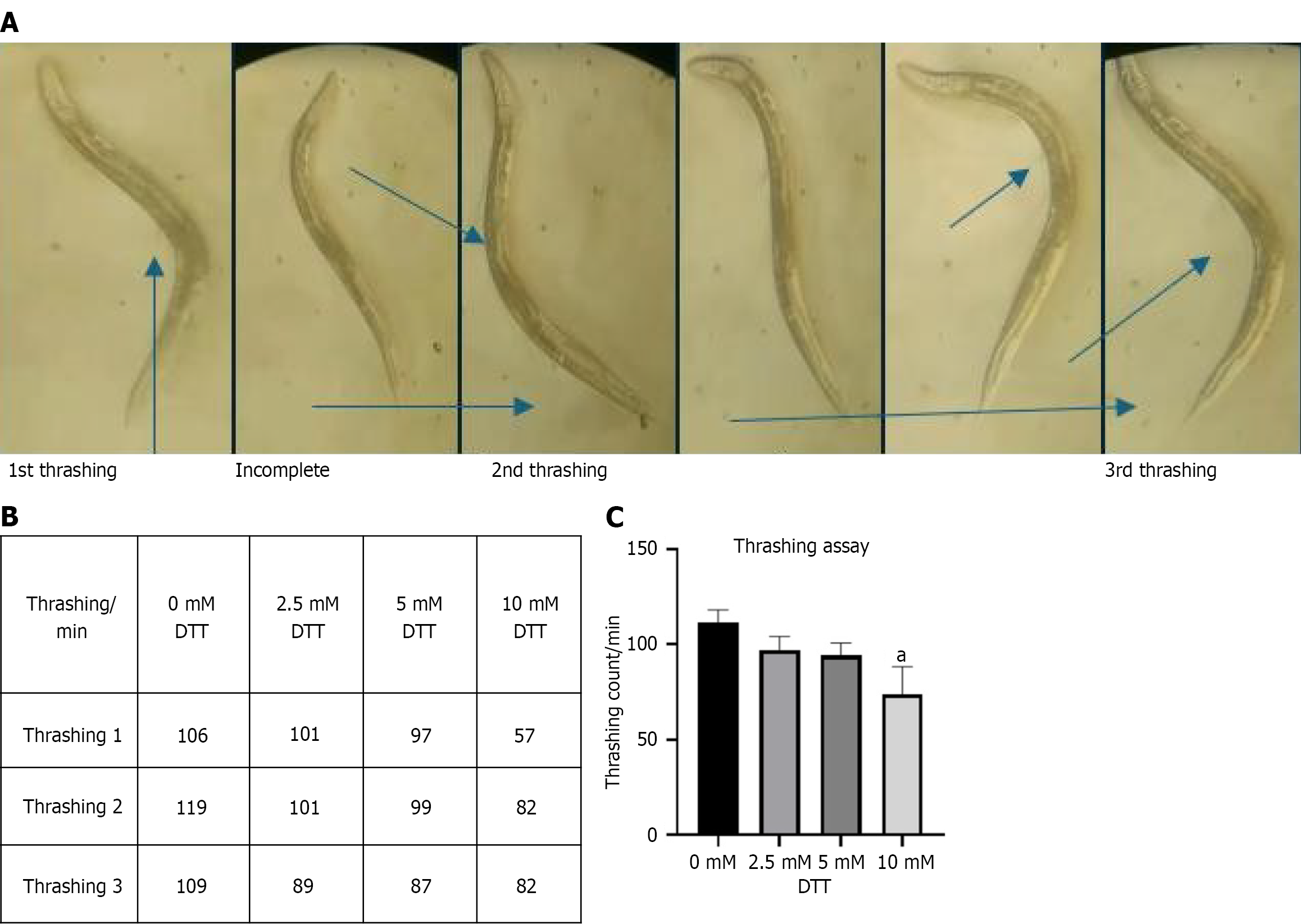

Thrashing assay: L4-stage worms were exposed to different concentrations of DTT on NGM plates for 24 hours. For the assay, 90 mm neutral NGM plates were filled with 2 mL of M9 buffer. Before starting, each worm was first placed on an unseeded NGM agar plate and allowed to crawl freely to remove any agglomerated bacteria. Once visually confirmed that the bacteria were removed, the worm was transferred into the M9 buffer. After 1 minute of acclimation, the number of thrashes (defined as a complete change in the direction of bending at the mid-body) was counted for 1 minute. At least 10 worms were assayed per group. The average number of thrashes per minute was calculated and compared between the DTT-treated groups and the control[22].

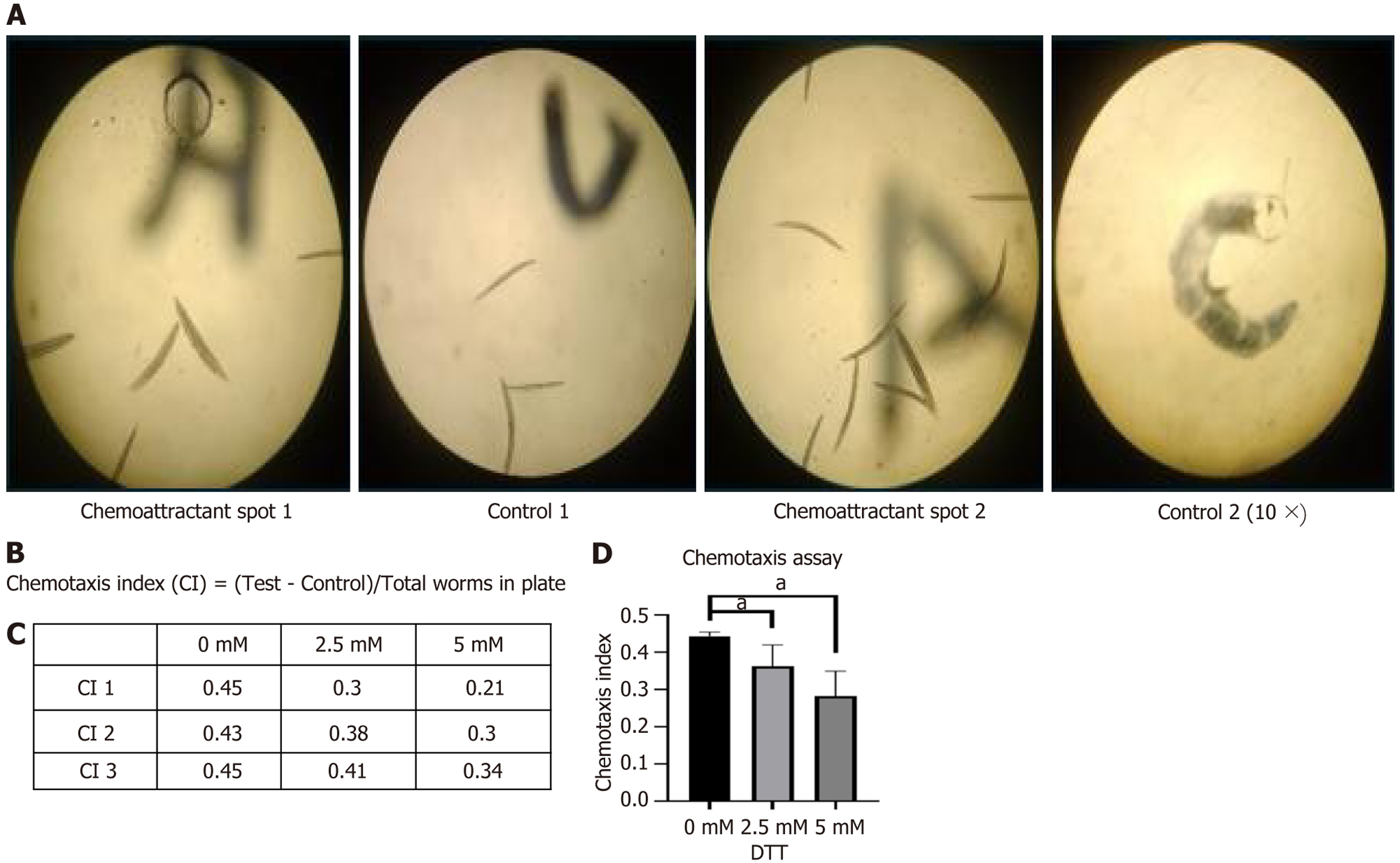

Chemotaxis assay: Synchronized young adult C. elegans were used for this assay. To remove bacterial residue, worms were washed with M9 buffer by centrifuging at 6000 rpm for 10 seconds, repeated three times. Each 90 mm NGM plate was divided into four equal quadrants by marking the underside. A central origin was marked with a circle of 0.5 cm radius. Two opposite quadrants (top-left and bottom-right) were designated as test (T) sites, and the other two (top-right and bottom-left) as control (C) sites. All points were placed at least 2 cm from the origin. A 5% butanone test solution was prepared by mixing equal volumes of butanone and 50 mmol/L sodium azide (used to immobilize worms at the spot). Worms were pipetted onto the center of the plate (2 µL per plate). Immediately, 2 µL of the test solution was added to each T site and 2 µL of the control solution (e.g., ethanol + azide) to each C site. Once absorbed into the agar, plates were covered, inverted, and incubated at room temperature for 60 minutes. After incubation, plates were transferred to a 4 °C incubator to immobilize worms until counting. Only worms that had crossed entirely the inner circle in any quadrant were counted. The chemotaxis index (CI) was calculated using the formula: CI = (Worms in both test quadrants - Worms in both control quadrants)/(Total of scored worms)[23].

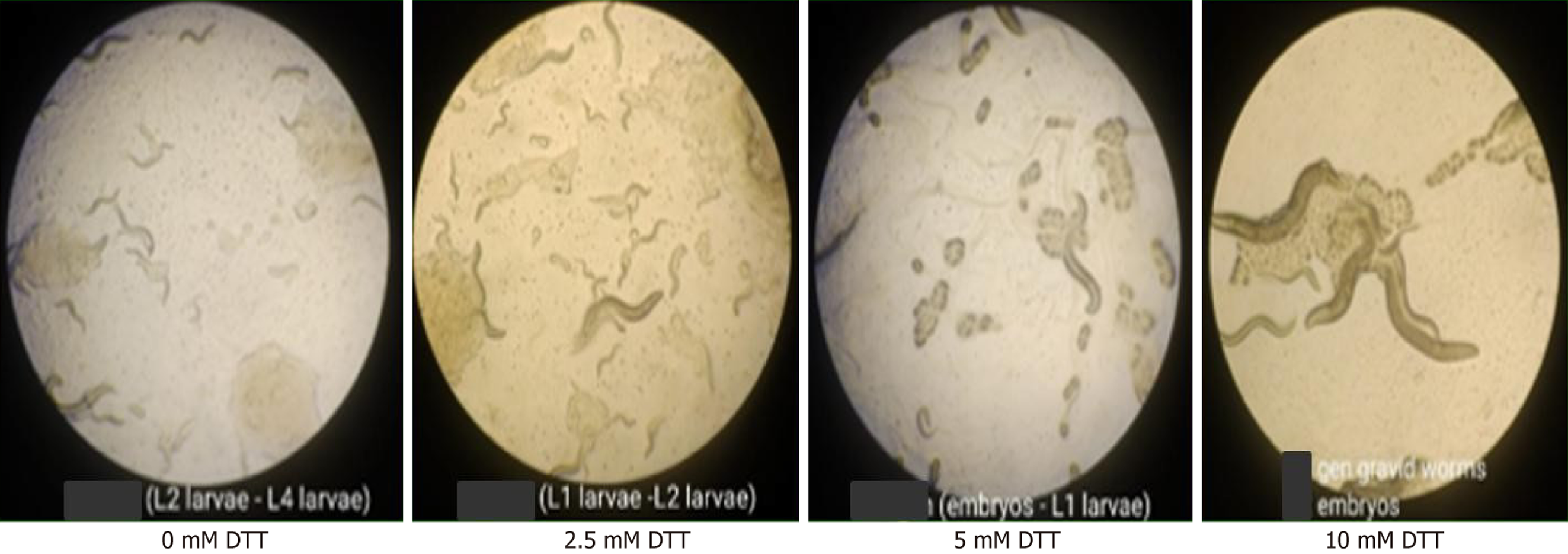

Growth and reproductive activity: Synchronized L4 stage C. elegans were transferred onto NGM plates supplemented with varying concentrations of DTT (0 mmol/L, 2.5 mmol/L, 5 mM, and 10 mmol/L). Plates were pre-seeded with E. coli OP50 and incubated at 20 °C for five days. Each concentration group was maintained under identical conditions. After five days of exposure, worms were observed using a compound microscope under 10 × magnification. Microscopic imaging was performed to document developmental stages and reproductive status across treatment groups. Worms were evaluated for size, developmental stage, and apparent reproductive activity[24,25]. This setup aimed to assess the impact of different DTT concentrations on growth and reproduction by direct visual comparison.

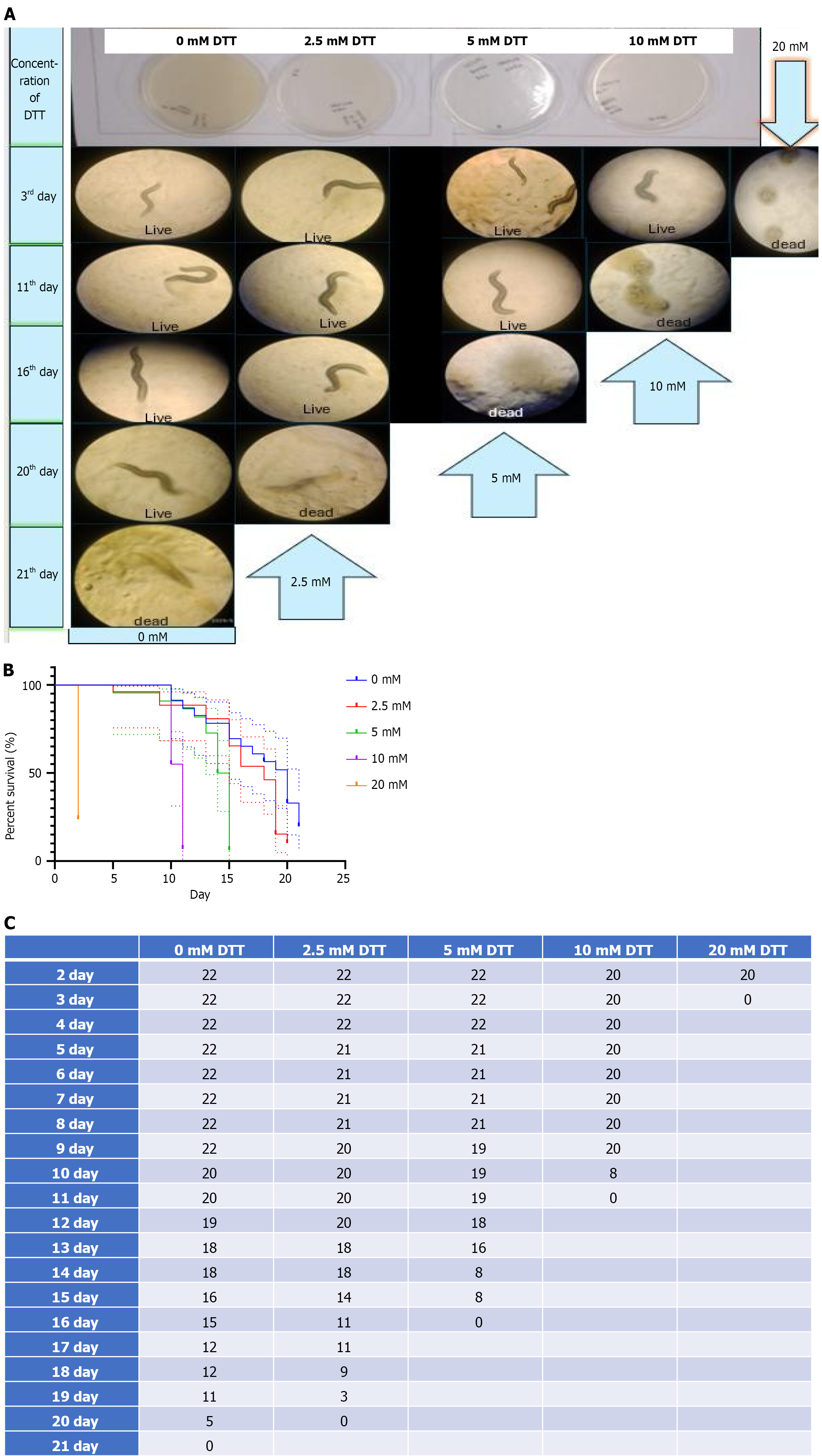

Lifespan assay: Lifespan was measured by monitoring worm survival daily, with dead worms recorded at regular intervals. Synchronized L4 stage worms were subsequently transferred to NGM plates containing OP50 and either with or without DTT. They were then cultured under standard laboratory conditions at a temperature of 20 °C. Each dish accommodated 30 ± 5 nematodes, and the experiment was repeated three times. The number of living nematodes was recorded daily until all subjects had died[26,27].

Synchronized C. elegans were obtained by bleaching and cultured on OP50-seeded NGM plates until the L4 stage. In parallel, NGM plates with 0, 2.5, 5, and 10 mmol/L DTT were prepared and seeded with OP50. L4 worms were then transferred to the DTT-treated plates and exposed for over 72 hours. Post-exposure, worms were washed off using M9 buffer and collected into microcentrifuge tubes. Samples were kept on ice. Laemmli sample buffer (4 ×) was added to reach a final 1 × concentration, and the tubes were incubated at 95 °C for 5 minutes to lyse the worms. Proteins were resolved using 10% SDS-PAGE stain-free precast gels and transferred onto PVDF membranes via semi-dry transfer. Membranes were blocked and probed with GRP78 primary antibody, followed by ALP-conjugated secondary antibodies. Bands were visualized using chemiluminescence and imaged on the Bio-Rad ChemiDoc MP system[28].

All experiments were conducted in triplicate, and data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 8.0. Quantitative results were expressed as mean ± SD. For comparing multiple groups, the Kruskal–Wallis test was applied, followed by Dunn's multiple comparisons test where applicable. Survival data were analyzed using Kaplan–Meier survival analysis, and differences between groups were assessed using the log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. Statistical significance was considered at P < 0.05.

To study the toxicity of DTT in C. elegans, we performed behavioral assays like locomotion (Body bending, thrashing), chemotaxis, growth, and reproductive output, as well as molecular assays, including western blotting to assess induction of ER Stress and its role in neurodegeneration.

Induction of ER stress and activation of UPR was confirmed with the elevated expression of GRP78 under various doses of DTT. Expression of GRP78 increases as the DTT concentration increases (Figure 1).

Body bending frequency decreased progressively with increasing concentrations of DTT. The Kruskal-Wallis test revealed a statistically significant reduction at higher concentrations. Figure 2A illustrates the criteria for counting a body bending defined as a complete flexion of the head region to the opposite side. Figure 2B represents the average number of Body bends per minute (mean of triplicates) in worms exposed to different DTT concentrations (0-10 mmol/L). Specifically, worms treated with 10 mmol/L DTT showed a highly significant decrease in bending frequency compared to the control group (0 mmol/L DTT) (P < 0.01, n = 3), indicating impaired neuromuscular function under elevated ER stress (Figure 2C).

Thrashing frequency showed a concentration-dependent decline with increasing DTT exposure. Control worms (0 mmol/L DTT) exhibited the highest mean thrashing rate, while the 10 mmol/L DTT group demonstrated the lowest thrashing frequency. Figure 3A illustrates how thrashing was measured, where one complete lateral movement of the tail to the opposite side was measured while the worm was freely swimming in the M9 buffer. Figure 3B presents the average thrashing counts (mean of triplicates) recorded over a 30-second interval for worms treated with varying concentrations of DTT (0–10 mmol/L). Figure 3C displays the statistical comparison using the Kruskal–Wallis test, which revealed a significant reduction in thrashing activity with increasing DTT concentrations (P < 0.001), indicating impaired neuro

DTT exposure caused a dose-dependent decline in chemotactic ability in C. elegans. The CI significantly decreased at 5 mmol/L DTT compared to the control group (0 mmol/L), indicating that higher concentrations of DTT impair the worms' ability to respond to chemoattractant. Figure 4A shows the schematic representation of the chemotaxis assay setup used to assess the worms' response to the chemoattractant. Figure 4B displays the formula used to calculate the CI: CI = Number of worms in attractant quadrants - Number in control quadrants/total number of worms scored.

Figure 4C presents the average CI values (mean of triplicates) at different DTT concentrations, indicating a concentration-dependent decrease in chemotactic behavior. Figure 4D shows statistical analysis using Brown-Forsythe and Welch one-way analysis of variance, followed by Dunnett's T3 post hoc test and Kruskal–Wallis test, confirming a significant difference between groups (P < 0.05), particularly at and above five mM DTT, suggesting sensory dysfunction under ER stress conditions.

To evaluate the effects of DTT-induced ER stress on growth and reproduction, C. elegans were exposed to increasing concentrations of DTT and observed after 5-7 days. As shown in Figure 5, developmental progression varied across concentrations. In the control group (0 mmol/L DTT), worms developed normally to L2-L4 stages. At 2.5 mmol/L DTT, most worms were arrested at the L1-L2 stages. A more substantial effect was observed at 5 mmol/L DTT, where the majority of the population comprised embryos and early L1 larvae. At 10 mmol/L DTT, gravid adults and embryos were present, but minimal further development was detected. These observations suggest a dose-dependent inhibitory effect of DTT on growth and reproduction in C. elegans.

To assess the effect of DTT-induced ER stress on survival, L4-stage C. elegans were exposed to increasing DTT concentrations and monitored daily. Control worms (0 mmol/L) displayed a typical lifespan of around 20 days. At 2.5 and 5 mmol/L DTT, a gradual decline in survival was observed. Worms on 10 mmol/L DTT survived for a few days before showing a sharp drop in viability. Notably, at 20 mmol/L DTT, worms were found dead within 24 hours of treatment, indicating severe acute toxicity. Kaplan–Meier survival analysis showed a dose-dependent reduction in lifespan, with a drastic and immediate effect seen at 20 mmol/L (Figure 6).

This study investigated the impact of DTT-induced ER stress on the behavioral, physiological, and developmental characteristics of C. elegans. Worms exposed to increasing concentrations of DTT exhibited progressive impairments in locomotion, chemotaxis, growth, reproduction, and lifespan. Notably, worms treated with 20 mmol/L DTT were found dead within 24 hours, indicating acute toxicity at higher concentrations[29]. Locomotor function was assessed using both the thrashing assay and the Body Bend assay, both of which revealed a concentration-dependent decline in movement. These findings suggest that DTT exposure impairs neuromuscular coordination, potentially due to ER stress-mediated disruption of neuronal or muscular function. Similarly, chemotaxis ability was markedly reduced, implying potential damage to sensory neurons or signaling pathways. In addition, worms exposed to higher concentrations of DTT exhibited developmental delays and reduced reproductive output, highlighting systemic physiological stress.

Although molecular validation is ongoing and will be performed through Western blotting, the observed phenotypic alterations are consistent with responses typically associated with ER stress. DTT is a well-established chemical agent used to induce ER stress by disrupting disulfide bond formation, thereby impairing protein folding and activating the UPR[2,30]. Chronic activation of ER stress pathways has been linked to cellular dysfunction, aging, and neurodegeneration in various models[31]. In C. elegans, such stress can lead to behavioral deficits and reduced lifespan[32,33].

In the ER lumen, a balanced oxidative environment is required for proper folding of proteins and their post-translational modifications, like disulfide bond formation. During the formation of a disulfide bond, the main reaction that occurs is an oxidation-reduction reaction (redox reaction) with the help of many oxidoreductase enzymes. The result of a redox reaction is the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS). If its production is in a controlled manner, then it helps in many biological processes like cell survival, aging. But if ROS is generated in an uncontrolled manner, then it leads to oxidative stress inside the cell[2,34]. This oxidative stress further affects the redox environment of the ER and alters protein folding. These unfolded or misfolded proteins accumulate in the ER and lead to ER stress[3]. In the case of DTT, it is also found that it creates ER stress by increasing the load of unfolded or misfolded proteins in the ER lumen. DTT is a reducing agent that breaks the disulfide bond of protein. DTT contains thiol groups and donates electrons to reduce the disulfide bond.

Along with this, DTT also reduces the level of ROS by transferring electrons to them and neutralizing them. This creates a reductive stress in cells[35]. To cope up with reductive stress, cells rely on redox-sensing mechanisms involving the protein FNIP1. FNIP1 uses its cysteine residue to sense the redox status of cells. FNIP1 has three conserved cysteine residues[36]. During reductive stress or low levels of ROS cysteine residue undergoes reduction, and reduced FNIP1 is recognized by a protein degradation complex called CUL2-FEM1B (a cullin-RING E3 ubiquitin ligase). This degradation complex makes ready FNIP1 for proteases degradation by adding ubiquitin to it. This causes elevation of ROS production via the oxidative phosphorylation mechanism[37]. This protease's degradation is facilitated with the help of zinc ions (Zn2+). Zn2+ ensures the binding of CUL2-FEM1B to reduced FNIP1, not oxidized FNIP1. Because of this, Zn2+ is also called molecular glue[38].

DTT is a reductive stressor that induces hypoxia by producing H2S (hydrogen sulfide). And also interacting with cysteine synthase 1 (cysl-1) or EGL-9 family hypoxia inducible factor 1 (egl-9). Hypoxia is thought to be a physiological condition that may induce ER stress by disturbing redox homeostasis and calcium homeostasis in the ER. Both events are crucial for protein folding; low oxygen level interferes with disulfide bond formation. And, disturbance in calcium homeostasis leads to UPR activation via hypoxia-inducible factor 1, vascular endothelial growth factor, phospholipase c, and inositol 3 phosphate interaction pathways[4,39].

Rhy1 (hypoxic response regulator), cysl-1 and egl-9 interaction control the activity of HIF-1 by hydroxylating it. Normally, egl-9 targets HIF-1 and degradation it by vhl-1 (von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor gene). cysl-1 generally inhibits egl-9 and helps in the stabilization of HIF-1. In normal conditions, rhy-1 inhibits cysl-1 and indirectly promotes egl-9 activity[39,40].

In DTT, toxicity produces H2S. This H2S and the direct action of DTT, which is not known yet, both target cysl-1 and activate it. cysl-1 further inhibits egl-9, and enhances the stability of HIF-1. This leads to activation of hypoxia signaling in cells[38], and this pathway leads to activation of Rhy-1-interacting protein in sulfide response (Rips-1), further con

The present findings suggest that the physiological and behavioral impairments observed may result from DTT-induced ER stress. DTT exposure creates an imbalance in the redox environment within the ER, resulting in improper protein folding and ER stress that can severely affect cellular functions. Further molecular analysis of neurodegenerative markers such as DAF-16 and Pink-1, etc., will help to confirm this hypothesis. It will also help to understand the role of DTT in generating ER stress and its connection with neurodegeneration.

We acknowledge the Department of Zoology, Mahatma Gandhi Central University, Motihari, India, for providing the necessary infrastructure to carry out the work. We acknowledge Dr Amit Ranjan, Mahatma Gandhi Central University, Motihari, Bihar, for his help and support in carrying out the research work on C. elegans.

| 1. | Wufuer R, Fan Z, Yuan J, Zheng Z, Hu S, Sun G, Zhang Y. Distinct Roles of Nrf1 and Nrf2 in Monitoring the Reductive Stress Response to Dithiothreitol (DTT). Antioxidants (Basel). 2022;11:1535. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | G G, Singh J. Dithiothreitol causes toxicity in C. elegans by modulating the methionine-homocysteine cycle. Elife. 2022;11:e76021. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Walter P, Ron D. The unfolded protein response: from stress pathway to homeostatic regulation. Science. 2011;334:1081-1086. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3842] [Cited by in RCA: 4723] [Article Influence: 337.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Oakes SA. Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Signaling in Cancer Cells. Am J Pathol. 2020;190:934-946. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 303] [Article Influence: 50.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Lin JH, Walter P, Yen TS. Endoplasmic reticulum stress in disease pathogenesis. Annu Rev Pathol. 2008;3:399-425. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 666] [Cited by in RCA: 666] [Article Influence: 37.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Wu SA, Li ZJ, Qi L. Endoplasmic reticulum (ER) protein degradation by ER-associated degradation and ER-phagy. Trends Cell Biol. 2025;35:576-591. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 25.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Chen X, Shi C, He M, Xiong S, Xia X. Endoplasmic reticulum stress: molecular mechanism and therapeutic targets. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8:352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 592] [Article Influence: 197.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lindholm D, Wootz H, Korhonen L. ER stress and neurodegenerative diseases. Cell Death Differ. 2006;13:385-392. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 613] [Cited by in RCA: 697] [Article Influence: 34.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Pincus D, Chevalier MW, Aragón T, van Anken E, Vidal SE, El-Samad H, Walter P. BiP binding to the ER-stress sensor Ire1 tunes the homeostatic behavior of the unfolded protein response. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:e1000415. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 300] [Cited by in RCA: 355] [Article Influence: 22.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Wilson DM 3rd, Cookson MR, Van Den Bosch L, Zetterberg H, Holtzman DM, Dewachter I. Hallmarks of neurodegenerative diseases. Cell. 2023;186:693-714. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1007] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Lamptey RNL, Chaulagain B, Trivedi R, Gothwal A, Layek B, Singh J. A Review of the Common Neurodegenerative Disorders: Current Therapeutic Approaches and the Potential Role of Nanotherapeutics. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:1851. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 468] [Article Influence: 117.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Brown RC, Lockwood AH, Sonawane BR. Neurodegenerative diseases: an overview of environmental risk factors. Environ Health Perspect. 2005;113:1250-1256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 292] [Cited by in RCA: 316] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Cavaliere F, Gülöksüz S. Shedding light on the etiology of neurodegenerative diseases and dementia: the exposome paradigm. Npj Ment Health Res. 2022;1:20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Markaki M, Tavernarakis N. Caenorhabditis elegans as a model system for human diseases. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2020;63:118-125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Meneely PM, Dahlberg CL, Rose JK. Working with Worms: Caenorhabditis elegans as a Model Organism. Curr Protoc Essent Lab Tech. 2019;19:e35. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Xu Y, Park Y. Application of Caenorhabditis elegans for Research on Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress. Prev Nutr Food Sci. 2018;23:275-281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Corsi AK, Wightman B, Chalfie M. A Transparent window into biology: A primer on Caenorhabditis elegans. WormBook. 2015;1-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Girard LR, Fiedler TJ, Harris TW, Carvalho F, Antoshechkin I, Han M, Sternberg PW, Stein LD, Chalfie M. WormBook: the online review of Caenorhabditis elegans biology. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D472-D475. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 153] [Cited by in RCA: 159] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Toader C, Tataru CP, Munteanu O, Serban M, Covache-Busuioc RA, Ciurea AV, Enyedi M. Decoding Neurodegeneration: A Review of Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Advances in Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, and ALS. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25:12613. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Lee JH, Han JH, Kim H, Park SM, Joe EH, Jou I. Parkinson's disease-associated LRRK2-G2019S mutant acts through regulation of SERCA activity to control ER stress in astrocytes. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2019;7:68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Brenner S. The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1974;77:71-94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10339] [Cited by in RCA: 12231] [Article Influence: 235.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Koopman M, Peter Q, Seinstra RI, Perni M, Vendruscolo M, Dobson CM, Knowles TPJ, Nollen EAA. Assessing motor-related phenotypes of Caenorhabditis elegans with the wide field-of-view nematode tracking platform. Nat Protoc. 2020;15:2071-2106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Margie O, Palmer C, Chin-Sang I. C. elegans chemotaxis assay. J Vis Exp. 2013;e50069. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Mukhopadhyay A, Tissenbaum HA. Reproduction and longevity: secrets revealed by C. elegans. Trends Cell Biol. 2007;17:65-71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Scharf A, Pohl F, Egan BM, Kocsisova Z, Kornfeld K. Reproductive Aging in Caenorhabditis elegans: From Molecules to Ecology. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:718522. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Qu Z, Liu L, Wu X, Guo P, Yu Z, Wang P, Song Y, Zheng S, Liu N. Cadmium-induced reproductive toxicity combined with a correlation to the oogenesis process and competing endogenous RNA networks based on a Caenorhabditis elegans model. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2023;268:115687. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Park HH, Jung Y, Lee SV. Survival assays using Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol Cells. 2017;40:90-99. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 14.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Jeong DE, Lee Y, Lee SV. Western Blot Analysis of C. elegans Proteins. Methods Mol Biol. 2018;1742:213-225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Sammi SR, Jameson LE, Conrow KD, Leung MCK, Cannon JR. Caenorhabditis elegans Neurotoxicity Testing: Novel Applications in the Adverse Outcome Pathway Framework. Front Toxicol. 2022;4:826488. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Manghwar H, Li J. Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and Unfolded Protein Response Signaling in Plants. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:828. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Pham TNM, Perumal N, Manicam C, Basoglu M, Eimer S, Fuhrmann DC, Pietrzik CU, Clement AM, Körschgen H, Schepers J, Behl C. Adaptive responses of neuronal cells to chronic endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress. Redox Biol. 2023;67:102943. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Rodriguez M, Snoek LB, De Bono M, Kammenga JE. Worms under stress: C. elegans stress response and its relevance to complex human disease and aging. Trends Genet. 2013;29:367-374. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 162] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Kim KW, Jin Y. Neuronal responses to stress and injury in C. elegans. FEBS Lett. 2015;589:1644-1652. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | D Thompson M. Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and Related Pathological Processes. J Pharmacol Biomed Anal. 2013;01. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 35. | Gores GJ, Flarsheim CE, Dawson TL, Nieminen AL, Herman B, Lemasters JJ. Swelling, reductive stress, and cell death during chemical hypoxia in hepatocytes. Am J Physiol. 1989;257:C347-C354. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 190] [Cited by in RCA: 193] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Manford AG, Rodríguez-Pérez F, Shih KY, Shi Z, Berdan CA, Choe M, Titov DV, Nomura DK, Rape M. A Cellular Mechanism to Detect and Alleviate Reductive Stress. Cell. 2020;183:46-61.e21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 139] [Article Influence: 23.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Manford AG, Mena EL, Shih KY, Gee CL, McMinimy R, Martínez-González B, Sherriff R, Lew B, Zoltek M, Rodríguez-Pérez F, Woldesenbet M, Kuriyan J, Rape M. Structural basis and regulation of the reductive stress response. Cell. 2021;184:5375-5390.e16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 22.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Ravi, Kumar A, Bhattacharyya S, Singh J. Thiol reductive stress activates the hypoxia response pathway. EMBO J. 2023;42:e114093. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Shen C, Shao Z, Powell-Coffman JA. The Caenorhabditis elegans rhy-1 gene inhibits HIF-1 hypoxia-inducible factor activity in a negative feedback loop that does not include vhl-1. Genetics. 2006;174:1205-1214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Ma DK, Vozdek R, Bhatla N, Horvitz HR. CYSL-1 interacts with the O2-sensing hydroxylase EGL-9 to promote H2S-modulated hypoxia-induced behavioral plasticity in C. elegans. Neuron. 2012;73:925-940. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/